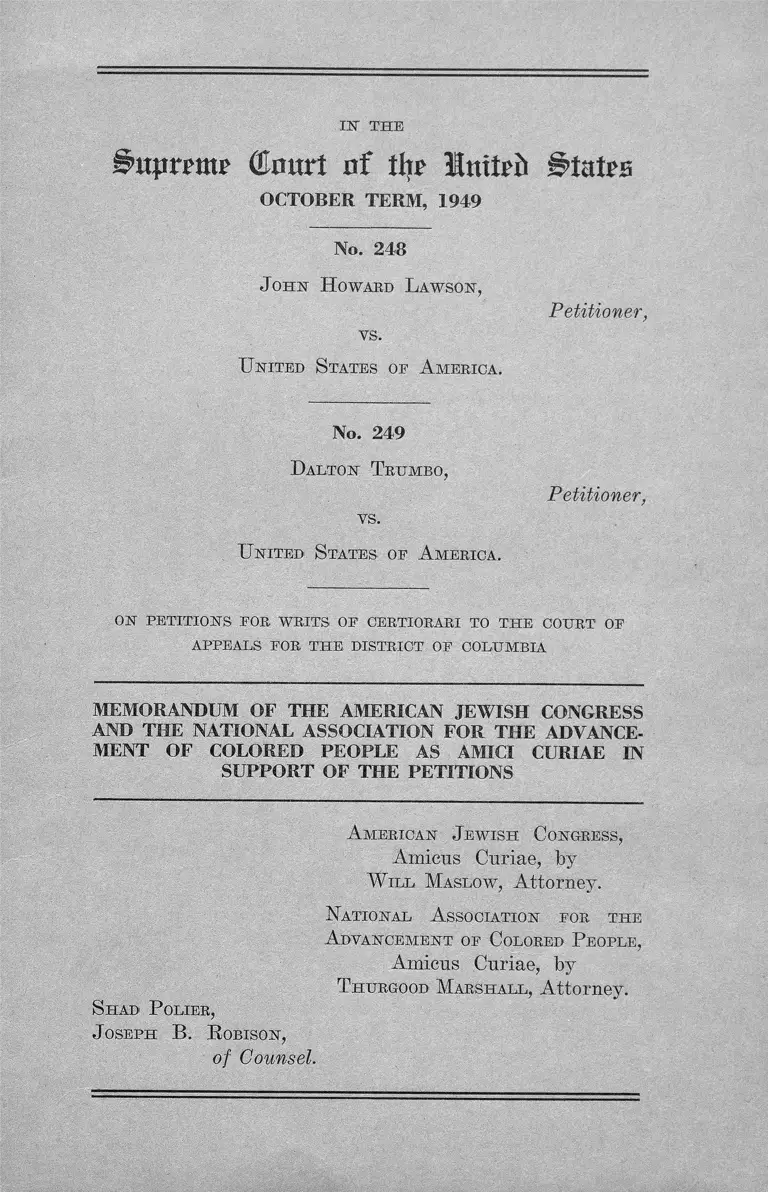

Lawson v. United States of America Memorandum as Amicus Curiae Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 19, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawson v. United States of America Memorandum as Amicus Curiae Support of Petitioners, 1949. 830b55bc-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/600e0369-1f0c-4a16-8ac6-f7ead78e8dfa/lawson-v-united-states-of-america-memorandum-as-amicus-curiae-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

mpreme (Eourt nf the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1949

No. 248

J ohn H oward L awson,

vs.

U nited S tates oe A merica.

No. 249

D alton T rumbo,

vs.

U nited States op A merica.

Petitioner,

Petitioner,

on petitions por writs op certiorari to the court op

APPEALS POR THE DISTRICT OP COLUMBIA

MEMORANDUM OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

AND THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONS

A merican J ewish Congress,

Amicus Curiae, by

W ill Maslow, Attorney.

National A ssociation por the

A dvancement op Colored P eople,

Amicus Curiae, by

T hurgood Marshall, Attorney.

S had P olier,

J oseph B . R obison,

of Counsel.

CASES CITED

PAGE

Chapman, In re, 166 IJ. S. 661 (1897)............................... 4

Harriman v. Interstate Commerce Commission, 211

U. S. 407 (1908)__________________________________ 4

Interstate Commerce Commission v. Brimson, 153

IT. S. 447, 478 (1894)........................................................ 4

Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 U. S. 68 (1881)................... 3, 4

McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 II. S. 135 (1927)................... 4

Sinclair v. United States, 279 U. S'. 263, 293 (1929)... 4

Supreme (Emtrl of % ImtPii States

OCTOBER TERM, 1949

IN THE

No. 248

J ohn H oward L awson,

Petitioner,

vs.

U nited States of A merica.

No. 249

D alton T rumbo,

vs.

U nited States of A merica.

Petitioner,

on petitions for writs of certiorari to the court of

APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

MEMORANDUM OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

AND THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONS

The undersigned organizations respectfully urge that

the petitions for writs of certiorari in the above cases he

granted so that there may be a final determination of the

issue whether a witness, subpoenaed before the House

2

Committee on Un-American Activities, may be punished

for refusal to answer the question: “ Are you a mem

ber of the Communist Party?” Counsel for petitioners

and respondent have consented to the filing of this memo

randum.

The American Jewish Congress was organized “ to safe

guard the civic, political, economic and religious rights

of Jews everywhere” and “ to help preserve, maintain and

extend the democratic way of life in the United States.”

The American Jewish Congress is, therefore, utterly op

posed to totalitarianism because it is inconsistent with

democracy. It is further opposed because it recognizes

that totalitarianism, whether of the right or the left, is

peculiarly the foe of Jewish survival. The former seeks

and achieves the destruction of the Jew through degrada

tion and persecution. The latter renders Jewish survival

impossible by proscribing the free development of Jewish

cultural and spiritual values without which Jewish exist

ence cannot be maintained.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People is a membership organization which for forty years

has dedicated itself to and worked for the achievement

of a functioning democracy as well as equal justice un

der the Constitution and laws of the United States.

A great number of the motion pictures to the production

of which petitioners contributed consistently showed the

Negro minority group in a truer light than it had previously

enjoyed. Par from being un-American in character, these

pictures were among the first to portray an unstereotyped

Negro. Therefore, the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People believes that the attack on

petitioners is in part an attack on the basic struggle for

equality of all people, regardless of race, creed, color or

nationality.

We respectfully submit that the present petitions should

be granted because, whether or not the Communist Party

is dedicated to achieving some form of totalitarian govern

ment in the United States, these cases involve the basic

3

question whether there are any constitutional limitations

(apart from the privilege against self-incrimination) upon

the Congressional power of investigation. The answer to

that question will define the powers of Congress in impor

tant respects.

In urging that an answer to this question be given, we

do not minimize the importance or value of Congressional

investigations. Only an informed Congress can wisely de

cide whether legislation is needed and, if needed, what legis

lation should be enacted to forestall, with due regard for

the Bill of Bights, acts endangering our democratic sys

tem of government. We recognize, too, that due respect

for a coordinate branch of the Government must require

the judiciary to weigh carefully anj ̂ petition that it re

strain the exercise of the Congressional power of investi

gation. For we recognize that in most instances such

restraint must come, if at all, from the political disap

proval of the electorate.

Nevertheless, this Court recognized as long ago as 1881

that, in a constitutional democracy, it is essential that

the judiciary have some supervision over attempts by

Congress to enforce its power of investigation. In Kil-

bourn v. Thompson, 103 U. S. 68 (1881), this Court con

sidered at length the much debated question whether Con

gressional Committees had power to conduct fact-finding

investigations. Without deciding that question, and as

suming that the power existed, this Court held that the

power was subject to certain limitations which the courts

could not ignore. Thus, it was held that the Senate or

the House of Representatives could require testimony

only “ in a matter into which that House has jurisdiction

to inquire, and * * * that neither of these bodies possesses

the general power of making inquiry into the private affairs

of the citizen” (103 U. S. at 190), “ If they are proceed

ing in a matter beyond that legitimate cognizance, we are

of opinion that this can be shown * * * otherwise the

limitation is unavailing and the power omnipotent” (id.

at 197). When the power of a House to inquire is called

4

“ in question * * * it should receive the most careful

scrutiny” (id. at 192, emphasis supplied).

These principles remain valid today. As recently as

1929, this Court quoted with approval Mr. Justice Field’s

statement that the Kilbourn case “will stand for all time

as a bulwark against the invasion of the right of the

citizen to protection in his private affairs against the

unlimited scrutiny of investigation by a congressional com

mittee.” Sinclair v. United States, 279 U. S. 263, 293

(1929). See also Interstate Commerce Commission v.

Brimson, 153 U. S. 447, 478 (1894); Harriman v. Inter

state Commerce Commission, 211 U. S. 407 (1908); In re

Chapman, 166 U. S. 661 (1897). In McGrain v. Daugherty,

273 U. S. 135 (1927), this Court held that the Congressional

power “ is a limited power, and should be kept within its

proper bounds; and, when these are exceeded, a jurisdic

tional question is presented which is cognizable in the

courts” (273 U. S. at 166). Accordingly, it held that “ a

witness rightfully may refuse to answer where the bounds

of the power are exceeded or the questions are not per

tinent to the matter under inquiry” (id. at 176),

These cases establish that the Congressional power to

investigate is limited and that when the power of a court

is invoked to implement a challenged exercise of that

power, it must determine “ for itself” whether the exer

cise was proper. Kilbourn case, supra, 103 U. S. at 106.

They indicate also that essentially different considerations

apply where the issue is whether a witness may be punished

because of his refusal to answer a question and where

the issue is whether the inquiry itself may be enjoined.

The cases establish that the former is justiciable, whether

punishment is by criminal conviction or by imprisonment

by vote of either House. The latter we conceive to be

a matter for political redress and to present a political

question outside the jurisdiction of the courts. Accord

ingly, review and reversal of the convictions in these cases

would not prevent the continued functioning of the House

Committee on Un-American Activities, but would leave

that matter to the wisdom of the House of Representatives.

Since the present cases do involve conviction and punish -

ment, they raise the following questions, among others,

which this Court has not yet decided:

1. May a private individual be punished for his refusal

to answer questions about his political affiliations, put by

a Congressional Committee, regardless of the relevance

of the question to an appropriate function of that Com

mittee 1

2. May a witness before a Congressional Committee

be punished for refusing to answer a question the pur

pose of which is solely to stigmatize and disgrace him and

deprive him of his livelihood?

3. May a witness before a Congressional Committee be

punished for his refusal to answer an inquiry concerning

Ms conduct where the sole purpose of the inquiry is to

deter that conduct and where the conduct is legal and

may not be constitutionally declared illegal.

4. May a witness charged with contempt, in order to

prove that Congress has transgressed the limit of its

powers, resort to evidence outside the official records of

Congress?

5. If a Congressional Committee uses its investigatory

powers to further ends which Congress cannot constitu

tionally achieve by legislation, such as interference with

freedom of expression, may the courts lend their aid to

such an abuse of power?

These important questions are not answered in the exist

ing decisions of this Court. We believe that they are not

satisfactorily answered in the decisions below in these

cases or the earlier decisions of the Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia dealing with contempt of

Congressional Committees.

6

To an increasing extent in recent years, Congressional

Committees have investigated, publicized, and issued offi

cial pronouncements upon the political activities of some

of our citizens. The extensive discussion of this develop

ment in the daily press, in journals of opinion, and in

legal periodicals, reveals a widespread fear that our

political liberties are endangered. We believe that that

fear will prove unjustified and that the process of Con

gressional investigation will prove fruitful if it is kept

within reasonable limitations. If, on the other hand, Con

gressional Committees are in effect freed of the Con

stitutional limitations which restrict the substantive acts

of all legislatures, the danger of repression will become

very real.

For the reasons stated above, we respectfully submit

that the petitions for writs of certiorari in these cases

should be granted.

A merican J ewish Congress,

Amicus Curiae, by

W ill Maslow, Attorney.

National, A ssociation for the

A dvancement of Colored P eople,

Amicus Curiae, by

T hurgood M arshall, Attorney.

Shad P olier,

J oseph B. B obison,

of Counsel.

October 19, 1949.

The Hecla Press : : New York City

39