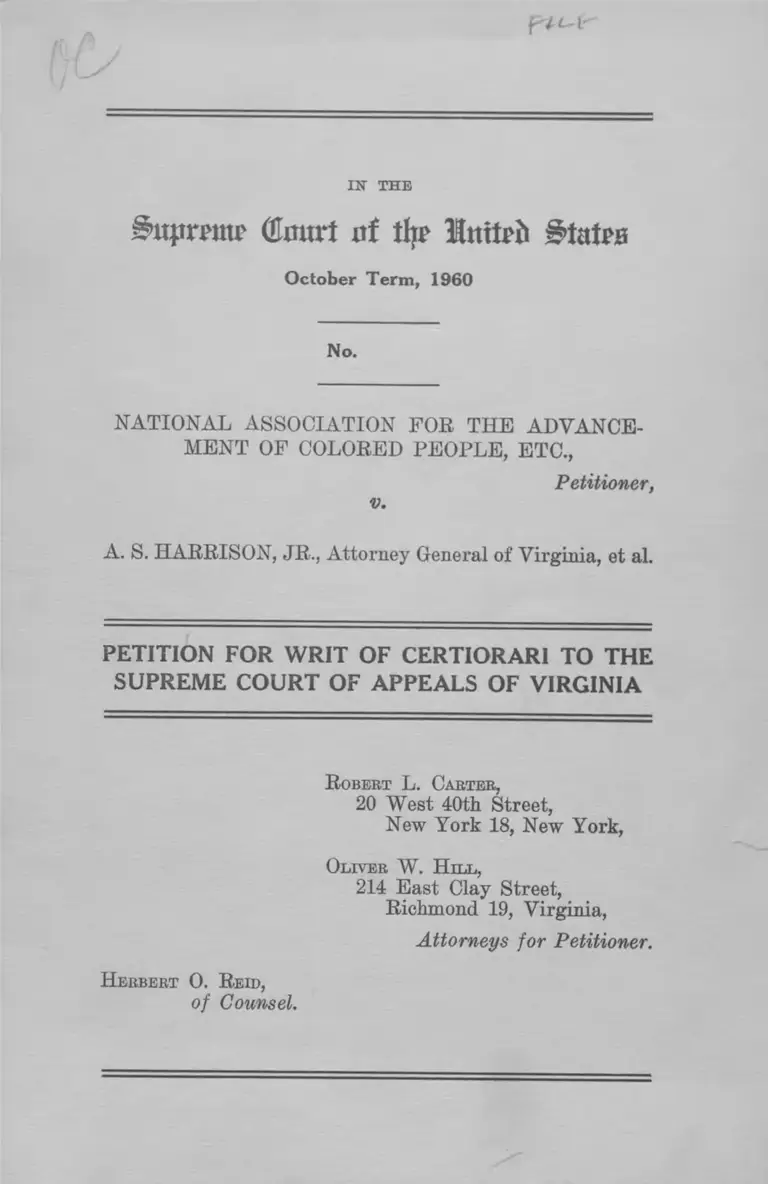

NAACP v. Harrison Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Harrison Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, 1960. 6b016440-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/602aa712-8926-4ef5-b999-c3e8da26feab/naacp-v-harrison-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-appeals-of-virginia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

fflmtrt rtf tip IhxxUh States

October Term, 1960

No.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, ETC.,

v.

Petitioner,

A. S. HARRISON, JR., Attorney General of Virginia, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Oliver W. H ill,

214 East Clay Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

H erbert 0 . Reid,

of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of Appeals of Virginia............................................... 1

Opinion Below .............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Statute Involved ......................... 2

Statement ........................................................................ 5

Question Presented ....................................................... 10

Reasons for Allowance of the W rit........................... 11

Conclusion .................................................................... 20

Appendix A—Opinion of Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia ................................................................... la

Judgment ................................................................. 29a

Denial of Petition for Rehearing........................ 29a

Appendix B—Opinion of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia entered

January 21, 1958......................................................... 30a

Table of Cases

Ades, In re, 6 F. Supp. 467............................. 14,18, fn 14,19

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co. v. United States, 298

U. S. 349....................................................................... 11

Barbier v. Connelly, 113 U. S. 27............................. 19

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516......................... 6, fn 2,16

11

PAGE

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199......................... 11

Brannon v. Stark, 185 F. 2d 871 (D. C. Cir. 1950),

aff’d 342 U. S. 451.................................................... 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483..........8,14, 15

Brush v. Carbondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N. E. 252 (1907) 19

Cantrell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296..................... 18, fn 13

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1..................................... 15

Crow, In re, 359 U. S. 1007......................................... 19

Davies v. Stowell, 78 Wis. 334, 47 N. W. 370.............. 19

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202................................. 18

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315......................... 11

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E.

2d 602 (1940) .............................................14,17, fn 10,19

Harrison v. Day, 106 S. E. (2d) 636......................... 15

Hooven & Allison Co. v. Evatt, 324 U. S. 652.......... 11

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 2 4 . . ................................. 18, fn 17

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959) 15

Koningsburg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S.

252 ................................................................................ 13

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501........................... 18, fn 13

Missouri ex rcl. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 3 3 7 .... 14

Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457..................................... 13

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 102 F.

Supp. 525 (W. D. Ky. 1951), aff’d 202 F. 2d 275

(6th Cir. 1953), vacated and remanded, 344 U. S.

971 ................................................................................ 11

N.A.A.C.P. v. xilabama, 357 U. S. 449..................6, fn 2,16

N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, 360 U. S. 167 . . . .5, fn 1, 9, fn 3,10

N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503...................... 8

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264..................................... 11

Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 U. S. 276......................... 11

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268......................... 11

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587............................. 11

I ll

PAGE

Ohio Valley Water Co. v. Ben Avon Borough, 253

U. S. 287...................................................................... 11

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354............................. 11

Raley v. Ohio, 360 U. S. 423 ........................................... 7

Royal Oak Drain. Dist. v. Keefe, 87 F. 2d 786 (6th

Cir. 1937) .................................................................... 19

St. Joseph Stock Yards Co. v. United States, 298

U. S. 38........................................................................ 11

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232 13

S’hanks Village Committee against Rent Increases

v. Cary, 103 F. Supp. 566 (S. D. N. Y., 1952) .. .18, fn 18

Shelton v. Tucker, — U. S. —, 29 L. W. 4058, dec.

Dec. 12, 1960 .......................................................16,18, fn 19

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649............................... 14

Spano v. New York, 360 U. S. 315................................. 11

Stark v. Wickard, 321 U. S. 288, 310...................... 14,18

S'weatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629................................. 14

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60................................. 16

Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 5 2 9 .... 19

Theard v. United States, 354 U. S. 278...................... 19

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312................................. 19

Vita-phone Corp. v. Hutchison Amusement Co., 28

F. Supp. 526 (D. Mass. 1939).................................... 19

AVatts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49..................................... 11

AVilliamson v. Le Optical o f Oklahoma, 348 U. S.

483 ................................................................................ 13

Constitution Cited

United States:

Thirteenth Amendment......................................... 13

Fourteenth Amendment ................................ 6,10,11,13

Fifteenth Amendment ......................................... 6,13

IV

Statutes, Texts and Miscellaneous Citations

PAGE

Canons of Professional Ethics (1938):

Canon 3 5 .................................................................. 12

Canon 4 7 .................................................................. 12

Opinion 148, Committee on Professional Ethics and

Grievances, A. B. A. (1935)................................. 14,17, fn 7

Opinion 282, Committee on Professional Ethics and

Grievances, A. B. A. (1950)..................................... 14

Code of Virginia as Amended:

Section 54-74 ........................................................... 2

Section 54-78 ........................................................... 4

Section 54-79 ........................................................... 5

United States Code, Title 28:

Section 1257(3) ................................. ................... 2

Note, 3 R. R. L. Rep. 1257 (1958)......................... 14,15,20

58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949)......................................... 14,18, fn 12

Bunche, R., Scottsboro Defense Committee..........17, fn 11

Church, S. H., “ Trade Unionism and Crime” , New

York Times, Oct. 1, 1922......................................... 17, fn 6

Jaffe, “ Judicial Review; Constitutional and Juris

diction Fact” , 70 Harv. L. Rev................................... 11

“ Programs, Ideologies and Tacits and Achievements

of Negro Betterment and Inter-Racial Organi

zations ...................................................................... 17, fn 11

Radin, “ Maintenance by Champerty” , 24 Calif. L.

Rev. 48 (1935)............................................................. 19

Schlesinger, A. M., Crisis of the Old Order (1957),

pp. 113, 1 4 9 .................................................17, fn 8,17, fn 11

Smith, R. H., Justice and the Poor (1921), p.

134 ...............................................................17, fn 9,18, fn 15

V

American Committee for the Protection of Foreign

Born ..........................................................................18, fn 20

American Committee for the Defense of Puerto Rican

Political Prisoners ...................................................17, fn 9

“ Judicial Administration and the Common Man” ,

287 Annals, pp. 34-41, 43-52,110-119,120-126 (1953) 19

“ Lagging Justice” , 328 Annals, passim (1960)___ 20

Letter of Gordon M. Tiffany, Staff Director of United

States Commission on Civil Rights to Senator

Jacob K. Javits........................................................ 14, fn 4

Nat’l Assn, of Manufacturers publication, “ The

Crime of the Century and Its Relation to Politics ’ ’,

p. 24 ............................................................................17, fn 6

National Committee for the Defense of Political

Prisoners, “ News You Don’t Get” , published

January 3 and August 11, 1936, April 27 and May

5, 1938 ......................... 17, fn 6,17, fn 9,18, fn 13,18, fn 20

New York Times Articles, “ Champion of Indians,

March 3, 1958...........................................................18, f i l l 2

PAGE

IN THE

^uprattp Glmtrt at % Jlmtpfc Btutvj

October Term, 1960

No.

N ational A ssociation foe the A dvancement of

Colored People, etc.,

Petitioner,

v.

A. S. H arrison, Jr., Attorney General of Virginia, et al.

---------------------- o---------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

entered on September 2, 1960, in the above-entitled cause.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the court below is reported at 202

Va. 142, 116 S. E. 2d 55, and is appended hereto, infra

at page la.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia, appended hereto, infra at page 29a, was entered on

September 2, 1960. An order was entered on October 12,

1960, denying petition for rehearing and is appended hereto,

infra at page 29a.

o

Application for an extension of time to and until Janu

ary 31, 1961, in which to file this petition was granted by

Mr. Justice Frankfurter in an order dated January 3,

1961.

Jurisdiction of this Court to review the judgment below

is invoked under Title 28, United States Code, §1257(3).

Statute Involved

Chapter 33

A cts of the General, A ssembly of V irginia

Extra Session, 1956

(Sections 54-74, 54-78 and 54-79 of the Code of

Virginia as amended)

An Act to amend and reenact %% 54-74, 54-78 and 54-79 of

the Code of Virginia, relating, respectively, to procedure

for suspension and revocation of licenses of attorneys

at law, and to running and capping.

Approved September 29, 1956

Be it enacted by the General Assembly of Virginia:

1. That §§ 54-74, 54-78 and 54-79 of the Code of Virginia

be amended and reenacted as follows:

§ 54-74. (1) Issuance of rule.—If the Supreme Court of

Appeals or any court of record of this State, observes, or

if complaint, verified by affidavit, be made by any person to

such court of any malpractice or of any unlawful or dis

honest or unworthy or corrupt or unprofessional conduct

on the part of any attorney, or that any person practicing

law is not duly licensed to practice in this State, such court

shall, if it deems the case a proper one for such action,

issue a rule against such attorney or other person to show

cause why his license to practice shall not be revoked or

suspended.

(2) Judges hearing case.—At the time such rule is is

sued the court issuing the same shall certify the fact of

such issuance and the time and place of the hearing thereon,

to the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Appeals, who

shall designate two judges, other than the judge of the

court issuing the rule, of circuit courts or courts of record

of cities of the first class to hear and decide the case in

conjunction with the judge issuing the rule, which such

two judges shall receive as compensation ten dollars per

day and necessary expenses while actually engaged in the

performance of their duties, to be paid out of the treasury

of the county or city in which such court is held.

(3) Duty of Commonwealth’s attorney.—It shall he the

duty of the attorney for the Commonwealth for the country

or city in which such case is pending to appear at the

hearing and prosecute the case.

(4) Action of court.—Upon the hearing, if the defend

ant be found guilty by the court, his license to practice law

in this State shall he revoked, or suspended for such time

as the court may prescribe; provided, that the court, in

lieu of revocation or suspension, may, in its discretion,

reprimand such attorney.

(5) Appeal.— The person or persons making the com

plaint or the defendant, may, as of right, appeal from the

judgment of the Court to the Supreme Court of Appeals

by petition based upon a true transcript of the record,

which shall be made up and certified as in actions at law.

(6) “ Any malpractice, or any unlawful or dishonest or

unworthy or corrupt or unprofessional conduct” , as used

in this section, shall be construed to include the improper

solicitation of any legal or professional business or employ

ment, either directly or indirectly, or the acceptance of

employment, retainer, compensation or costs from any per

son, partnership, corporation, organization or association

4

with knoivledge that such person, partnership, corporation,

organization or association has violated any provision of

Article 7 of this chapter, or the failure, without sufficient

cause, within a reasonable time after demand, of any attor

ney at law, to pay over and deliver to the person entitled

thereto, any money, security or other property, which has

come into his hands as such attorney; provided, hoivever,

that nothing contained in this Article shall be construed to

in any way prohibit any attorney from accepting employ

ment to defend any person, partnership, corporation, or

ganization or association accused of violating the provisions

of Article 7 of this chapter.

(7) Representation by counsel.—In any proceedings to

revoke or suspend the license of an attorney under this or

the preceding section, the defendant shall be entitled to

representation by counsel.

§ 54-78. As used in this article:

(1) A “ runner” or “ capper” is any person, corpora

tion, partnership or association acting in any manner or

in any capacity as an agent for an attorney at law within

this State or for any person, partnership, corporation,

organization or association which employs, retains or com

pensates any attorney at law in connection with any judicial

proceeding in which such person, partnership, corporation,

organization or association is not a party and in which it

has no pecuniary right or liability, in the solicitation or

procurement of business for such attorney at law or for

such person, partnership, corporation, organization or asso

ciation in connection with any judicial proceedings for

which such attorney or such person, partnership, corpora

tion, organization or association is employed, retained or

compensated.

The fact that any person, partnership, corporation,

organization or association is a party to any judicial pro

ceeding shall not authorize any runner or capper to solicit

0

or procure business for such person, partnership, corpora

tion, organization or association, or any attorney at laic

employed, retained or compensated by such person, part

nership, corporation, organization or association.

(2) An “ agent” is one who represents another in deal

ing with a third person or persons.

§ 54-79. It shall be unlawful for any person, corpora

tion, partnership or association to act as a runner or cap

per as defined in % 54-78 to solicit any business for an

attorney at law or such person, partnership, corporation,

organization or association, in and about the State prisons,

county jails, city jails, city prisons, or other places of deten

tion of persons, city receiving hospitals, city and county

receiving hospitals, county hospitals, police courts, county

courts, municipal courts, courts of record, or in any public

institution or in any place or upon any public street or

highway or in and about private hospitals, sanitariums

or in and about any private institution or upon private

property of any character whatsoever.

2. An emergency exists and this act is in force from

its passage.

Statement

Petitioner is a nonprofit membership corporation, incor

porated under the laws of the State of New York (F. 45,

165, 496-502)P It is licensed to do business in Virginia

as a foreign corporation (F. 191). * 2

1 There are two transcripts which make up the record in this

case: (1 ) The printed record used in connection with the appeal

in N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, No. 127, Oct. Term, 1958, 360 U. S.

167— the citations to that record will be identified by the prefix “ F” ;

(2 ) the printed record of additional testimony taken in the Circuit

Court of the City of Richmond, when suit was there instituted for

an authoritative state construction and interpretation of the legislation

at issue in this petition— references to this record will be identified

by the prefix “ S” .

6

Petitioner’s activities in Virginia are carried on through

some 89 chartered branches scattered throughout the state.

These branches are grouped together into an unin

corporated association called the Virginia State Conference

of Branches which acts on matters of statewide concern

(F. 46, 134-135, 136). Its basic aims and purposes are to

improve the status of Negroes in American life,2 and

through the national organization, the Virginia State Con

ference of Branches, local branches and members, petitioner

seeks full citizenship rights for all persons in Virginia with

out debilitation based upon race.

In its effort to achieve this overall objective, petitioner

encourages Negroes to assert their constitutional rights

and in some instances, assists those who institute litiga

tion that seeks vindication of the guarantees against racial

and color differentiations contained in the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States (F. 170, 171). While petitioner, of course, attempts

to achieve its aims in other ways as well (F. 171, 172), the

issues raised in this case relate solely to its involvement

in litigation in which Negroes resort to the courts in an

effort to free themselves and the country of the burdens

of racial discrimination.

The Virginia State Conference has a legal committee

presently composed of 15 lawyers (S. 93) residing in

different parts of the state. This committee, more com

monly known as the legal staff, is elected at each annual

state convention, and it in turn elects a chairman (F. 48,

157; S. 102-104).

The petitioner organization becomes involved in liti

gation when an aggrieved person contacts either a member 2

2 The Court has had occasion to examine the aims, purposes and

organizational structure of the petitioner organization. See N.A.A.C.P.

v. Alabama. 357 U. S. 449; Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516.

Hence, no detailed explanatory statement in that regard is being set

forth in this petition.

/

of the legal staff in person or the Executive Secretary of

the Virginia State Conference of Branches, who then refers

the complaining party to the Chairman or to some other

member of the legal staff, if the situation appears to be

a genuine grievance concerning state-imposed racial dis

crimination (F. 48, 147-150, 207, 563, 567). The Chairman

either confers with the complaining party or is apprised of

the facts by a member of the legal staff. If he concludes

that the situation is one with which the organization should

concern itself, he recommends that the State Conference

assume the financial obligations involved in prosecuting

the matter in the courts (F. 48, 150, 209, 210). This recom

mendation is communicated to the President of the State

Conference and upon the latter’s concurrence the Confer

ence obligates itself to underwrite the expenses of the

litigation (F. 48, 150). In most instances the lawyer

handling the litigation is a member of the legal staff (F.

152, 153, 159), and there is no complaint in the record from

any litigant in this regard. Once the Conference under

takes to underwrite the cost of the litigation, it does not pay

any monies to the complaining party. The funds go to

the attorney representing the litigant for out-of-pocket

expenses incurred, plus a fixed per diem for time spent

in the preparation and trial of the cause (F. 48, 209-210,

646-647). The compensation received by the lawyers is

well below that which they would normally feel entitled

to demand (F. 321, 325, 329).

Petitioner’s policy against discrimination is well known,

and the public is aware of the fact that it will underwrite

the costs of prosecuting in the courts a legitimate com

plaint involving discrimination which it believes to be

unlawful (S. 113).

Petitioner is not a legal aid society. It does not give as

sistance to Negroes merely because they are Negroes or be

cause they are indigent, and membership in the organization

is not essential for aid to be forthcoming. Petitioner con

cerns itself solely with the validity of racial discrimination

8

where resolution of the question involved may affect

Negroes in general (S. 121). For the past several years—

since 1950 at least—it has refused to finance litigation

involving racial discrimination unless the court action was

aimed at contesting the legality of racial segregation per se

(S. 113, 125). Tt does not act until some individual comes

asking for help (F. 144), and if there is a change of heart

and the individual wishes to withdraw prior or subsequent

to the commencement of the law suit, there is never any

problem of his being able to do so (F. 232; S. 80, 131).

Chapter 33, along with Chapters 31, 32, 35 and 36, was

passed as a package at the 1956 Extra Session of the

General Assembly of Virginia. These statutes were part

of Virginia’s “ massive resistance” plan to implementation

of this Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483. The chronology of events, from the appoint

ment of the Gray Commission on Public Education, which

was empowered to recommend ways and means for deal

ing with the Brown decision, to the 1956 Extra Session of

the General Assembly, called to enact legislation to pre

serve segregated schools and at which Chapter 33 became

law, is set out in the opinion of Judge Soper in N.A.A.C.P. v.

Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E. D. Va. 1959), appended hereto

infra, pages 30a, 40a-47a, and will not need repetition here.

In the belief that Chapters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 36 were

enacted to destroy the organization and that the laws

denied due process, equal protection of the laws, free

dom of speech and association to petitioner and all those

connected with it in seeking the development and imple

mentation of constitutional doctrine outlawing racial dis

crimination, petitioner brought suit in a specially-consti

tuted statutory United States District Court for the East

ern District of Virginia attacking the constitutionality of

all of these statutes and seeking to enjoin their enforce

ment (See N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty, supra). That court, on Janu

ary 21, 1958, struck down Chapters 31, 32 and 35. It found

Chapters 33 and 36, however, too ambiguous for construe-

9

tion by the federal court prior to an authoritative construc

tion and interpretation by the state courts, and as to these

latter statutes, petitioner was instructed to institute pro

ceedings in the state courts.3

The instant proceedings were instituted in the Circuit

Court of the City of Richmond seeking a judgment declara

tory of the construction and interpretation of Chapters 33

and 36 to the effect that the activities of petitioner, its affili

ates, officers, members, contributors and voluntary workers,

in encouraging Negroes to assert their constitutional rights

and in expending monies to defray the cost of litigation

designed to eliminate state-imposed racial segregation; the

practice of litigants, in accepting such aid in cases aimed

at the establishment of legal and constitutional standards

of equal justice without regard to race or color; and the

activities of attorneys, in representing such litigants when

the fees and expenses are paid by petitioner, were lawful

and not in violation of Chapters 33 and 36. In addition, peti

tioner alleged that if Chapters 33 and 36, as construed,

rendered these aforesaid activities unlawful, that Chapters

33 and 36 were unconstitutional and void, being in violation

of the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States, and their enforcement against petitioner, and those

associated with it should be permanently enjoined.

The case was tried in the Circuit Court on the record

and exhibits used in connection with the appeal in

3 Subsequently, sub nom N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, 360 U. S.

167, the judgment of the federal court in respect to Chapters 31,

32 and 35 was vacated upon the grounds that the doctrine of federal

abstention required the federal court to withhold a decision on the

merits in respect to these statutes until they had been given an

authoritative interpretation by the state courts. Such proceedings

are now pending in the Circuit Court o f the City of Richmond. The

outcome of those proceedings will undoubtedly be affected by this

determination.

10

N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, 360 U. S. 167, the bill of complaint

hied by petitioner, respondent ’s answer and additional tes

timony and exhibits adduced at the trial in the Circuit

Court of the City of Richmond.

That court construed Chapters 33 and 36 as proscribing

petitioner’s giving assistance to persons in litigation involv

ing racial discrimination and found no inconsistency be

tween the statutes as thus construed and the constitutional

guarantees of equal protection and due process.

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia,

Chapter 36 was held to be fatally defective, in that it was

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States. Chapter 33, however, was found to be a

proper regulation of the legal profession and a valid prohi

bition of the activities of the petitioner which were held to

constitute the unlawful solicitation of legal business. The

Supreme Court of Appeals concluded that Chapter 33 pro

hibited petitioner’s giving assistance to litigants to vindicate

their constitutional rights to freedom from racial discrimi

nation, by referring complaints brought by such persons to

attorneys associated with petitioner and by paying to the

attorneys whatever fees and expenses such litigation

involved.

Application for rehearing was denied and petitioner

brings the cause here.

Question Presented

Whether a state, under the guise of regulating the

practice of law, may make criminal the activities of peti

tioner and its affiliates, in defraying the costs and expenses

of litigation instituted by Negroes who seek to vindicate

their constitutional right to be free of racial discrimination,

where these activities are not undertaken to promote any

private or commercial interests, and may subject attorneys

acting as counsel in such litigation to disbarment or other

11

disciplinary proceedings, without violating the Fourteenth

Amendment mandates of due process and equal protection

of the laws and without abridging the Constitution’s guar

antee of free access to the courts.

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ

1. This Court’s consistent practice of making its own

independent evaluation of the evidentiary facts upon which

a lower court’s adjudication of constitutional claims is based

compels the granting of this petition. See, Blackburn v.

Alabama, 361 U. S. 199; Spano v. New York, 360 U. S. 315;

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S’. 264; Muir v. Louisville Park

Theatrical Association, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W. D. Ivy. 1951),

aff’d, 202 F. 2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953), vacated and remanded,

344 U. S. 971; Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268, 271;

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, 316, 322, fn. 4; Watts v.

Indiana, 338 U. S. 49, 50-51; Hooven £ Allison Co. v. Evatt,

324 U. S. 652, 659; Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, 358;

Baltimore £ Ohio Railroad Company v. United States, 298

U. S. 349, 372; St. Joseph Stock Yards Company v. United

States, 298 U. S. 38, 49-55; Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587,

389, 590; Ohio Valley Water Company v. Ben Avon Borough,

253 U. S. 287. Cf. Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 U. S. 276, 284,

285. And see Jaffe, “ Judicial Review: Constitutional and

Jurisdiction Fact,” 70 Ilarv. L. Rev. 953 (1957). Indeed,

this case is strikingly illustrative of the wisdom of the

Court’s refusal to foreclose reappraisal of a finding that is

essential to determination of a constitutional question.

Here, the state and federal courts, on virtually the same

evidence, reached irreconcilable conclusions as to what facts

the record discloses. The Supreme Court of Appeals reads

the evidence as showing that petitioner is “ engaged in

fomenting and soliciting legal business” in which it is

not a party and has “ no pecuniary right or liability,” and

which it channels “ to the enrichment of certain lawyers

employed” by it, “ at no cost to the litigants and over

12

which the litigants have no control” (See Appendix A,

infra at p. 15a). It found no merit in petitioner’s argument

that its activities are not “ what are commonly considered

as solicitation of business contrary to the canons of legal

ethics” (id. at p. 16a). It concluded that the petitioner

and its affiliates act as intermediaries between the client

and the lawyer in the solicitation of legal business and.

therefore, that acceptance of employment by attorneys of

cases handled under petitioner’s auspices violate Canons

35 and 47 of the Canons of Professional Ethics in force

in Virginia since October 21, 1938, 178 Va. p. X X X II (id.

at 17a). The court stated that Chapter 33 was designed,

to and could appropriately curb the kind of activities in

which petitioner is engaged and, held that in regulating

and restricting petitioner’s actions, the statute does not

violate constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech or

association, due process or equal protection of the laws.

The federal court, on the other hand, found that the

activities of petitioner did not “ amount to a solicitation of

business or a stirring up of litigation of the sort condemned

by the ethical standards of the legal profession” (See

Appendix B, infra at p. 81a). Moreover, it found peti

tioner’s activities authorized by Canon 35 of the Canons

of Professional Ethics of the American Bar Association

(id. at p. 79a). While finding Chapter 33 obscure and

difficult to understand, the court concluded “ the general

purpose seems to be to hit any organization which parti

cipates in a law suit in which it has no financial interest

and also to fasten the charge of mal-praetice upon any

lawyer who accepts employment from such an organization.

If the statute should be so interpreted as to forbid a con

tinuance of the activities of [petitioner] in respect to liti

gation as described in this opinion, it would in large

measure destroy [its] effectiveness,” (id. at p. 83a).

That the state and federal courts reached disparate

determinations as to petitioner’s constitutional claims was

13

the inevitable consequence of the division between them

as to what the evidentiary facts disclosed. Pursuant

to the principle enunciated in the cases hereinabove cited,

it is respectfully submitted that this petition should be

granted. Then, this Court, after an independent evaluation

of all the evidentiary facts contained in this record, may

determine for itself whether there is merit to petitioner’s

contention that Chapter 33, as applied to its activities,

infringes rights of freedom of speech and of association,

denies due process and equal protection of the laws and

constitutes an effective barrier to free access to the coui'ts

raised against those seeking relief from racial discrimina

tion imposed by state officials.

2. In characterizing petitioner’s activities as the

solicitation of legal business under the terms of Chapter

33, the court below gave a construction and interpretation

to the statute which renders it arbitrary and unreasonable

within the meaning of applicable decisions of this Court.

See Koningsburg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252;

Schware v. State Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232; Morey

v. Bond, 354 U. S. 457; Williamson v. Lee Optical of

Oklahoma, 348 U. S. 483. Maintenance of the integrity

of the legal profession is, of course, a matter of appropriate

concern for the state legislature. In dealing with Chapter

33, however, as it relates to petitioner’s activities, it should

be recognized, petitioner submits, that far more than that

abstract question is present.

The petitioner organization, since its inception, has

been engaged in an effort to secure equal civil rights for

Negroes within the democratic process. Prevailing politi

cal, social and economic forces have offered little prospect

of legislative or executive action to correct the inequi

ties of second-class citizenship. But complaint in respect to

the validity of caste and color differentiations lends itself to

adjudication in the courts, since what is involved is a

determination of the meaning and scope of the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States.

14

Petitioner has sought the establishment in the funda

mental law of such yardsticks as would outlaw the evil of

racial discrimination. Pursuant to this end petitioner sup

ports test cases aimed chiefly at determining the reach

and scope of due process, equal protection and constitu

tional guarantees against disenfranchisement. Some of

these cases reached this Court, e.g., Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Smith v. AUwright, 321 U. S. 649;

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U. S. 483. That petitioner has made possible the

preparation and research necessary for presentation of the

constitutional issues involved in the above and other litiga

tion concerning the validity of some aspect of racial dis

crimination; that it has paid the legal fees and expenses;

and that attorneys associated with it were counsel in such

cases has been no secret. See Note, 58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949).

The high cost of litigation makes sponsorship of this kind of

litigation by the individual Negro an impossibility.4 Peti

tioner does not concern itself with business or private in

terests of individuals. It involves itself in litigation relat

ing solely to civil rights, and then only where the question

being litigated is likely to have an impact upon the Negro

community as a whole. Of course, in a larger sense the

issues determined in litigation sponsored by petitioner affect

the whole American public. The lawyers involved, while

receiving some financial remuneration, do not obtain any

thing close to what would be considered an adequate fee for

legal services.5 Petitioner’s activities and those of the

lawyers come within that category which the courts and bar

associations have given unqualified approval. See e.g., In re

Ades. 6 F. Supp. -167 (Tb C. Md. 1934); Gunnels v. Atlantic

Bar Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E. 2d 602 (Ga. 1940); Opinion

No. 148, A. B. A. Opinions of the Committee on Professional

Ethics and Grievances 308 (1935); Opinion 282, id., at page

591 (1950); Note, 3 R. R. L. R. 1257.

4 See letter of Gordon M. Tiffany, Staff Director of the United

States Commission on Civil Rights to Senator Jacob K. javits, 106

Cong. Rec. (No. 35) 3376-3377 (Feb. 27, 1960).

5 See Tiffany, op. cit. supra, note 4.

15

Certainly the kinds and types of litigation with which

petitioner is connected make it highly improbable that its

activities are of that class that gives the bench and bar

concern about the maintenance of the integrity of the legal

profession. Indeed, little interest was manifested in peti

tioner’s support of litigation until some states began to

seek a means to avoid adhering to Brown. See Note,

3 R. R. L. Rep. 1257 (1958). Since implementation of any

doctrine of constitutional law, unless voluntarily adhered

to by state officials, requires the institution and prosecu

tion of court litigation, it soon became evident that the

state policy of segregation might be preserved for a while,

at least, if petitioner was prevented from supporting liti

gation to invalidate segregation.

Viewed realistically, therefore, there is no escape from

the conclusion that Virginia sought by this statute to under

gird its plan of “ massive resistance” to the implementation

of the Brown decision. With decisions in Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1; Harrison v. Bay, 106 S. E. (2d) 636; James v.

Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959), appeal dis

missed, 359 U. S. 1006, “ massive resistance” proved to be a

bankrupt policy, and it was abandoned. Resistance to full

implementation of constitutional proscriptions against

racial segregation, however, is still a potent force in the

state today.

Whatever the intent and purpose of Chapter 33, as now

construed and applied its effect is to immobilize petitioner

organization and greatly handicap the effort to secure

implementation of the Brown decision in Virginia. On the

other hand, all the state’s resources are being used to

maintain the prevailing pattern of segregation, thereby

preventing many residents and citizens of Virginia from

enjoyment of their declared constitutional rights.

In the light of these circumstances, the construction and

application of Chapter 33 enunciated below is not reasonably

16

related to a valid governmental objection, and the statute,

therefore, is fatally defective. Cf. Shelton v. Tucker, —

U. S. —, 29 L. W. 4058, decided December 12, 1960.

3. As construed, Chapter 33 cannot be squared with the

decisions of this Court in N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357

U. S. 449, and Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516. The court

below states that petitioner and its associates “ may not be

prohibited from acquainting persons with what they believe

to be their rights and advising them to assert their rights, in

so doing it is prohibited from soliciting legal business for

their attorneys or any particular attorneys.” Moreover, the

court below held that petitioner’s activities constituted

solicitation. Thus, the asserted protection of freedom of

speech and association guarantees becomes empty cant.

The court holds that petitioner and its members cannot

engage in the activities revealed in this record. No attor

ney on the petitioner’s State Conference legal staff can

safely act as counsel in any litigation in which petitioner

has acquainted persons with their rights, advised them to

assert same or contributed money for prosecution of the

law suit, without being prospectively guilty of violating

this statute. No other attorneys can act in such cases

since they are subject to being the “ particular attorneys”

for whom petitioner has engaged in solicitation of legal

business. The short of it is that petitioner must forego

any activity relating to litigation to avoid the pinch of

Chapter 33. Since this has been the area of petitioner’s

greatest effectiveness, Chapter 33, therefore, as now con

strued means a serious weakening, if not destruction, of

petitioner organization in Virginia. As such, it is sub

mitted, the rights of petitioner’s members to freedom of

association and to take lawful action to secure the lawful

objective of equal citizenship privileges for all persons with

out regard to their race have been seriously impaired. See

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, supra; Bates v. Little Rock, supra;

Cf. Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60.

17

4. The decision below seriously restricts group sponsor

ship of test litigation, designed for ultimate determination

by this Court, ill which serious and legitimate claims are

made concerning the constitutional validity of a federal or

state statute, action or regulation which poses a threat to

some group interest. As such the questions raised should be

settled by this Court since this is a case of first impression

having far reaching consequences of national import and

affecting a myriad variety of federal rights. Cf. Raley v.

Ohio, 360 U. S. 423.

Group sponsorship of litigation has been an accepted

practice in the United States, for many years. Labor

unions,0 trade associations,6 7 consumers organizations,8 na

tionality groups,9, bar associations,10 11 ad hoc committees,11

6 See reprint of testimony of Walter Drew before Senate Judiciary

Committee (1914) in, “ The Crime of the Century and Its Relation to

Politics,” p. 24 (Nat’l. Assn, of Manufacturers publication) : News

You Don’t Get, August 11, 1936, April 27 and May 5, 1938 (pub

lished by National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners)

pages unnumbered; Church, S. H., “ Trade Unionism and Crime.”

New York Times, Oct. 1, 1922.

7 E.g., The National Erector’s Association retained Walter Drew

to represent it in litigation. See reprint referred to in note 6 supra.

Counsel cannot document the fact that trade associations have given

support to litigation which seeks to determine the validity of laws

affecting business interests since such information is not contained

in the case reports. However, it would be a fair assumption that

such support does take place, especially since Bar Association hold

ings have condoned litigation of this character. See Opinion 148,

Committee on Professional Ethics and Grievances, A.B.A. (1935).

8 The Consumers League sponsored litigation involving the con

stitutionality of social welfare legislation in the 1930’s. Schlesinger

A. M., Crisis of the Old Order (1957) pp. 113 and 419.

9 Between 1856 and 1875 the German Society provided a special

legal committee to protect newly arrived immigrants. Smith, R. H.,

Justice and the Poor (1921) p. 134, American Committee for the

Defense of Puerto Rican Political Prisoners. News You Don’t Get,

op. cit, supra, note 6.

10 Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Association, 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E.

(2d) 602 (1940).

11 E.g., See Schlesinger, A. M., op. cit. supra, note 8 at page 113;

Scottsboro Defense Committee, Bunche, R . ; “ Programs, Ideologies

and Tacits and Achievements of Negro Betterment and Inter-Racial

Organizations,” manuscript prepared for the Carnegie Foundation

Study by Gunnar Mydral of the Negro in America (1940).

18

racial groups,12 religious groups,13 labor defense commit

tees,14 child welfare organizations,15 16 civil liberties groups,10

property owners,17 tenants,18 professional group,19 and

committees for protection of immigrants20 have sponsored

litigation involving some legal question affecting the inter

ests of the group concerned. In the field of constitutional

law where adjudication of a case or controversy is a pre

requisite to judicial determination of whether governmental

action is constitutionally permissible, the test case is a

recognized method of raising constitutional claims. See

Stark v. Wickard, 321 T . S. 288, 310; Evers v. Dwyer, 358

U. S. 202.

The right of individual or groups to sponsor litigation

where there is no agreement to share the proceeds and

where the members of the group have a common or general

or patriotic interest in the principle of law to be estab

12 See New York Times article, Champion of Indians, March

3, 1958; Note, 58 Yale L. J., supra.

13 E.g., Johovah’s Witnesses apparently sponsored a number of

cases in the United States Supreme Court, e.g., Marsh v. Alabama,

326 U. S. 501, and Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296. The

Methodist Federation for Social Service provided financial assistance

in the Scottsboro Case. News You Don't Get, Jan. 3, 1936, pages

unnumbered.

14 E.g.. See. In Re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934).

15 E.g., The Children’s Aid Society of Boston, Smith, R. H.,

Justice and the Poor, op. cit. supra, note 7 at page 223 (1921), p.

223.

16 E.g., The American Civil Liberties Union.

17 Opinions of the Committees on Professional Ethics of the

Association of the Bar of the City of New York and the New York

County Lawyer’s Association, Columbia Univ. Press, 1956, Op. No.

113; Hurd v. Plodge, 334 U. S. 24.

18 Shanks Village Committee Against Rent Increases v. Cary,

103 F. Supp. 566 (S. D. N. Y. 1952).

19 E.g., Shelton v. Tucker, — U. S. — , 29 L. W . 4058, decided

Dec. 12, 1960.

20 E.g., American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign

Born assisted Otto Richter, a German refugee seeking political

asylum, News You Don’t Get. Feb. 25, 1935, pages unnumbered.

19

lished has been sanctioned by court decisions. See Brannon

v. Stark, 185 F. 2d 871 (D. C. Cir. 1950), aff’d 342 U. S. 451;

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. R. 2d 602

(1940) ; Brush v. Carbondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N. E. 252

(1907); Davies v. Stowell, 78 Wis. 334, 47 N. W. 370; Royal

Oak Drain. Dist. v. Keefe, 87 F. 2d 786 (6th Cir. 1937); Vita-

phone Corp. v. Hutchison Amusement Co., 28 F. Supp. 526

(D. Mass. 1939); In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934).

This decision below, therefore, not only affects peti

tioner’s interests and those associated with it, but is ad

verse to the sponsorship of litigation by any group. This

raises serious questions relating to the individual’s right

and opportunity to subject governmental action to measure

ments against the requirements of the Constitution of the

United States. It seriously hampers the individual in

exercise of his right of access to the courts, see Terral v.

Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529; Truax v. Corrigan,

257 U. S. 312, 334; Barhier v. Connelly, 113 U. S. 27, 31, and

raises grave questions in respect to state authority to de

limit the prosecution of federal rights in the federal courts.

Cf. Theard v. United States, 354 U. S. 278; In re Crow,

359 U. S. 1007.

Barratry, maintenance and champerty were the great

evils of a bygone era. See Radin, “ Maintenance by Cham

perty,” 24 Calif. L. Rev. 48 (1935); Note, 3 R. R. L.

Rep. 1257 (1958). Today the court and the bar seek

to guard against commercialization of the law and the

reduction of the profession from a high and noble priest

hood to a competitive business enterprise with a resultant

lowering of ethical standards. The high cost of legal serv

ices, and its unavailability to lower and middle-income

groups, see “ Judicial Administration and the Common

Man,” 287 Annals pp. 34-41, 43-52, 110-119, 120-126

(1953), and the time-consuming factor in litigation, see

“ Lagging Justice,” 328 Annals, passim (1960), have been

the chief concerns in modern day administration of justice.

At best, the state’s power to deal with the evils of bar

ratry must compete with the public interest in keeping the

20

pathway to the courts unimpeded. In attempting to ac

commodate these two competing claims, suppression of fun

damental personal freedom must be avoided.

Whether, therefore, an organization, such as that now

before the Court, in seeking the adjudication and settlement

of constitutional questions which affect the lives, hopes and

aspirations of a sizeable segment of the nation’s popula

tion, is engaged in unlawful activities in furnishing the

means for prosecution of litigation testing the validity of

racial discrimination, is a question of paramount impor

tance which should be determined by this Court.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, it is

respectfully submitted that this petition should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Oliver W. H ill,

214 East Clay Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

H erbert 0 . R eid,

of Counsel.

APPENDIX A

(Opinion of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia)

Present: All the Justices

-----------------------o-----------------------

Record No. 5096

N ational A ssociation for the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, etc.

A. S. H arrison, J r ., Attorney General of Virginia, et al.

Record No. 5097

N.A.A.C.P. L egal Defense and E ducational F und, I nc.

—v.—

A. S. H arrison, Jr., Attorney General of Virginia, et al.

---------------------- o-----------------------

Opinion by Justice L awrence W . I ’A nson

Staunton, Virginia, September 2, 1960

F rom the Circuit Court of the City of R ichmond

E dmund W . H ening, Jr., Judge:

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, hereinafter referred to as the NAACP, and

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

hereinafter referred to as the Fund, appellants herein, filed

their separate bills of complaint in the court below against

Albertis S. Harrison, Jr., Attorney General of the Common

wealth of Virginia, the attorneys for the Commonwealth of

2a

the cities of Richmond, Newport News and Norfolk, and the

counties of Arlington and Prince Edward, Virginia, appel

lees herein, to secure a declaratory judgment construing

chapters 33 and 36, Acts of Assembly, Ex. Sess., 1956,

codified as §§ 54-74, 54-78, 54-79, Code of 1950, as amended,

1958 Replacement Volume, and §§ 18-349.31 to 18-349.37,1

inclusive, Code of 1950, as amended, 1958 Cum. Supp., as

they may affect the appellants, their officers, members,

affiliates of NAACP, contributors, voluntary workers, at

torneys retained or employed by them or to whom they may

contribute monies and expenses, and litigants receiving

assistance in cases involving racial discrimination, because

of the activities of the NAACP and the Fund in the past or

the continuation of like activities in the future.

The NAACP, in addition to seeking a construction of

the aforementioned statutes, alleged that the statutes are

unconstitutional and void because their enforcement would

deny to it, its affiliates, officers, members, contributors,

voluntary workers, attorneys retained or employed by it,

and litigants whom it may aid, due process of law and

equal protection of the laws in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

The two suits were heard and considered together in the

court below, by consent of all parties, on the appellants’

bills; their exhibits, which included a transcript of the evi

dence, exhibits, the majority and dissenting opinions of the

three-judge federal court, and the judgment entered in the

case of National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (judgment vacated

and remanded sub nom. Harrison, et al. v. National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of Colored People, 360 U. S.

167, 79 S. Ct. 1025, 3 L. ed. 2d 1152); the answers and

exhibits of the appellees; and ore tenus testimony on behalf

of the appellees and the NAACP, except one deposition

taken on behalf of the NAACP. No testimony was taken

on behalf of the Fund. *

iN ow §§ 18.1-394 to 18.1-400, 1960 Cum. Supp.

3a

The court below held, so far as need here be stated,

(1) that chapters 33 and 36 do not violate the constitutional

guarantees of freedom of speech and assembly, due process

of law and equal protection of the laws under the Four

teenth Amendment; (2) that the evidence shows that the

appellants, their officers, affiliates, members, voluntary

workers and attorneys are engaged in the improper solici

tation of legal business and employment in violation of

chapter 33 and the canons of legal ethics; (3) that attorneys

who accept employment by appellants to represent litigants

in cases solicited by the appellants, and in which they pay

all costs and attorneys’ fees, are violating chapter 33 and

the canons of legal ethics; and (4) that the appellants and

those associated with them advise persons of their legal

rights in matters in which the appellants have no direct

interest, and whose professional advice has not been sought

in accordance with the Virginia canons of legal ethics, and

as an inducement for such persons to assert their legal

rights through the commencement of or further prosecution

of legal proceedings against the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia, any department, agency or political subdivision

thereof, or any person acting as an employee for either or

both or any of the foregoing, the appellants furnish attor

neys employed by them and pay all court costs incident

thereto, and that these activities violate either chapter 33

or 36, or both.

The court’s decree enumerated certain detailed activ

ities of the appellants which do not violate chapters 33 and

36, and since they are not challenged by any of the parties

hereto, they need not be stated herein.

From the decree of the chancellor we granted an appeal

and supersedeas in each cause. They will be considered to

gether by us, as they were in the court below, except the

statutes involved will be considered separately.

The questions presented on these appeals are:

(1) Do the activities of the appellants, or either of

them, amount to solicitation of business, prohibited by chap

ter 33?

4a

(2) Do the activities of the appellants, or either of

them, amount to an inducement to others to commence or

further prosecute lawsuits against the Commonwealth, its

officers, agencies, or political subdivisions, as prohibited by

chapter 36?

(3) Do the provisions of either chapters 33 or 36 violate

the Virginia Bill of Rights (Constitution § 12) and the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States ?

The evidence shows that the NAACP and the Fund are

non-profit membership corporations organized under the

laws of the State of New York with authority to operate in

this Commonwealth as foreign corporations. The NAACP

and the Fund functioned as one corporation with the same

officers, directors and members from 1911 until 1948, when,

for tax purposes and other reasons, the Fund was organ

ized as a separate corporation.

The principal purpose of the NAACP is to eliminate all

forms of racial segregation. It has been described by its

counsel as a political organization for those who oppose ra

cial discrimination.

Affiliated with the NAACP are approximately one thou

sand unincorporated branches operating in forty-five states

and the District of Columbia. The branches are chartered

by the NAACP, and, for failure of the branch officers to

follow strictly the policies and directives of the national

body, their charters may be revoked or their officers re

moved. The branches are generally grouped together in

each state into an unincorporated association. In Virginia

the association is known as the Virginia State Conference

of NAACP Branches.

The State Conference holds annual conventions which

are attended by delegates from the local branches. It takes

the lead in NAACP’s activities in this State under the ad

ministration of a full-time salaried executive secretary who

is responsible to a board of directors. The executive sec

retary coordinates the activities of the branches in accord

ance with the policies and objectives of the Conference and

5a

the NAACP, supervises local membership and fund rais

ing campaigns, distributes educational material dealing

with racial matters, and performs many other duties.

The executive secretary, members of the legal staff, and

other representatives of the State Conference make

speeches before local branches and other groups for the

purpose of advising those present that all segregation laws

are unconstitutional and void, and urging them to chal

lenge laws to eliminate segregation through the institution

of legal proceedings which the State Conference, the

NAACP and the Fund sponsor at no cost to the litigants.

The aid given litigants to initiate suits is in the form

of furnishing lawyers who are members of the legal com

mittee of the Conference, the NAACP, and regional counsel

of the Fund, the payment of court costs and other expenses

of litigation.

The Conference receives financial support to defray the

cost of litigation it sponsors and other expenses from the

local branches, the national bodies, and contributions.

Letters and directives addressed to officers of local

branches and signed by the executive secretary of the Con

ference, filed as exhibits by the appellees, show the plans,

methods and procedures used by the NAACP to sponsor lit

igation in school cases.

A letter dated May 26, 1954, reads in part as follows:

“ It is of utmost importance that your branch retain the

leadership in all actions engaged in in your community. ’ ’

In a letter dated June 16, 1954, it is said:

‘ ‘ The Conference is proceeding with the development of

its plan and will advise you thereof as soon as this work is

completed.”

A confidential directive of June 30, 1955, from the presi

dent and executive secretary to local branches relative to

the handling of petitions for presentation to local school

boards stated in part as follows:

“ Petitions will be placed only in the hands of highly

trusted and responsible persons to secure signatures of

parents or guardians only.

6a

“ The signing of the petition by a parent or guardian

may well be only the first step to an extended court fight.

Therefore, discretion and care should he exercised to se

cure petitioners who will—if need be—go all the way. * * *

“ The Education Committee chairman will forward

completed petitions to the Executive Secretary of the

State Conference. * * *

“ Following the above procedure, it becomes apparent

that the faster your branches act the sooner will your

school board be petitioned to desegregate your schools.

Every act of our branch and the State Conference officials

from this point on should be considered as an emergency

action, and must take precedence over routine affairs—

personal or otherwise.”

Another directive contained in part these instructions:

“ Organize the parents in the community so that as

many as possible will be familiar with the procedure when

and if law suits are begun in behalf of plaintiffs and parents.

“ I f no plans are announced or steps taken towards de

segregation by the time school begins this fall, 1955, the

time for law suits has arrived. At this stage court action

is essential because only in this way does the mandate of

the Supreme Court that a prompt and reasonable start

towards full compliance become fully operative on the

school boards in question.

“ At this stage the matter will be turned over to the

Legal Department and it will proceed with the matter in

court. ’ ’

An official report of NAACP and its Virginia Confer

ence activities from May 17, 1954, to September 13, 1957,

shows the purpose and a continuation of their method of

operation as follows:

“ U p to D ate P icture op A ction by N A A C P B ranches

Since M ay 31.

“ A. Petitions filed and replies.

“ A total of 55 branches have circulated petitions.

“ B. Where suits are contemplated.

7a

“ Petitions have been tiled in seven (7) counties/cities.

Graduated negative response received in all cases.

“ C. Readiness of lawyers for legal action in certain

areas.

“ Selection of suit sites reserved for legal staff.

“ State legal staff ready for action in selected areas.

“ D. Do branches want legal action?

“ The majority of our branches are willing to support

legal action or any other program leading to early desegre

gation of schools that may be suggested by the National

and State Conference officers. Our branches are alert to

overtures by public officials that Negroes accept voluntary

racial segregation in public education.”

An explanation of the above report was made by the

executive secretary of the Conference as follows: The

language, “ Where suits are contemplated,” referred to

places where petitions had been denied by local school

boards; “ Readiness of lawyers for legal action in certain

areas, ’ ’ meant financial aid was available; and ‘ ‘ Selection

of suits reserved for legal staff,” meant that members of

the legal staff would pick the places where suits would be

brought.

The State Conference maintains a legal staff of fifteen

members, one of whom serves as chairman without compen

sation for that particular service. The members of the

staff are elected at the annual convention of the Conference

after being nominated by a committee, which in turn re

ceives its recommendations for candidates from the chair

man of the legal staff, and there have never been additional

nominations from the floor of the convention.

The members of the legal staff of the Conference are re

imbursed for expenses incurred in speaking before local

branches and other groups and are paid fees at the rate of

$60.00 per day for their services in cases in which NAACP

has interested itself, “ as long as such attorneys adhere

strictly to NAACP policies,” namely, that a school case

must be tried as a direct attack on segregation. Every

item of expense and all legal fees paid by the Conference

8a

are approved by the chairman of the legal staff, except the

expenses and fees of its chairman, which are approved by

the president of the Conference. One member of the legal

staff testified that he entered two of the school segregation

cases at the suggestion of the chairman, and that the rela

tionship “ has been so pleasant and so profitable.” Only

members of the legal staff are selected by NA A OP to bring

suits in which it has an interest, and the places for bring

ing such suits are selected by the chairman, who refers the

case to a member of the legal staff residing in the area from

which the complaining party came. Without exception,

when a member of the legal staff brings a lawsuit in his

community other members of the staff are associated with

him.

The chairman of the legal staff of the Conference is a

member of the legal committee of the NAACP, Virginia

counsel for the NAACP, and its registered Virginia agent.

The NAACP is not a legal aid society. Its policy dur

ing the past several years has been not to participate in

cases simply because Negroes need assistance on account of

poverty. Assistance is given only in cases involving con

stitutional rights, and then only so long as litigants adhere

to the principles and policies of the NAACP and the Con

ference.

The initial contact in the Charlottesville school segrega

tion case was made by the president of the local branch

of the NAACP when he requested the chairman of the legal

staff to speak at a meeting of parents of certain school

children. At this meeting some of the parents signed

authorization forms for the chairman to represent such

parents and their children in legal proceedings to desegre

gate the schools of that city. Other authorization forms

were distributed and signed with no attorney’s name

appearing thereon, but the name of the chairman of the

legal staff was inserted later.

In the Arlington school case, the petition presented to

the local school board for desegregation of the schools

was prepared by the State Conference, and most of the

9a

signatures were obtained by the vice-president of the

Arlington branch, who was also one of the plaintiffs in

a suit later instituted. She was told by the chairman of

the legal committee of the Conference and the regional

counsel of the Fund that they would institute legal pro

ceedings if the school board denied the request to desegre

gate the schools.

All authorization forms used in the school segregation

cases were prepared by the chairman of the legal staff

and most of them authorized the attorney named therein

to associate such other attorneys as he desired. Usually,

the general counsel of the NAACP and the regional counsel

of the Fund are associated in the trial of cases sponsored

by the Conference, even though such association is not

directly authorized by the litigants.

Ordinarily a complaint is filed with the executive secre

tary, who refers it to the chairman of the legal staff, and

the chairman with the concurrence of the president of the

Conference, decides whether suit will be instituted. The

executive secretary, however, testified that he did not

refer any of the plaintiffs in the school segregation cases

to the chairman of the legal staff.

Many of the litigants in school cases had no personal

contact with any of the lawyers handling cases in which

their names appeared as parties plaintiff, and learned

of the institution of suits from newspaper accounts. Some

of the litigants stated that they did not know the names

of the lawyers representing them, but they did know they

were NAACP lawyers.

Only one witness, out of some twenty-four litigants in

school cases, testified that he would have instituted legal

proceedings if the NAACP had not agreed to finance them.

The Fund has a small membership and no affiliates. Its

financial support comes from contributions solicited bv

letters and telegrams from New York City. The purpose

of the Fund, as stated in its certificate of incorporation, is

as follows:

10a

“ (a) To render legal aid gratuitously to such Negroes

as may appear to be worthy thereof, who are suffering legal

injustice by reason of race or color and unable to employ

and engage legal aid and assistance on account of poverty.

“ (b) To seek and promote the educational facilities for

Negroes who are denied the same by reason of race or

color.

“ (c) To conduct research, collect, collate, acquire, com

pile and publish facts, information and statistics concern

ing educational facilities and educational opportunities

for Negroes and the inequality in the educational facilities

and educational opportunities provided for Negroes out of

public funds, and the status of the Negro in American life.”

The director-counsel of the Fund is charged with the

duty of carrying out the purposes set out in the charter

and the policies fixed by its board of directors. He has

under his direction a legal research staff of six full-time

lawyers who reside in New York City but who may be

assigned to places out of New York. In addition to the

full-time legal staff, the Fund has five regional counsel,

including one residing in Richmond, Virginia, at an annual

retainer of $6,000. The Fund also has at its disposal

social scientists, teachers of government, anthropologists

and sociologists who are used principally in cases involving

school litigation.

The regional counsel of the Fund residing in Richmond,

Virginia, is also a member of the legal staff of the Con

ference and the legal committee of the NAACP.

The Fund has been approved by the State of New York

to operate as a legal aid society because of the provisions

of the barratry statute of New York, but counsel stated it

does not operate as such. A representative of the Fund

testified in the case of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People v. Patty, supra, that it

furnishes legal assistance when a Conference lawyer re

quests it or when it is revealed from an investigation, made

by the New York office through its regional counsel or

one of the lawyers on the State Conference staff, that

11a

discrimination exists because of race or color. All costs

and expenses incurred in such suits brought on behalf of

Negroes are borne by the Fund. The assistance given may

be in the form of providing lawyers to assist Conference

staff lawyers in the trial of a case, or in the preparation

of briefs.

Most of the litigants in the school segregation cases

brought in this State were financially able, according to

the standards set by the Fund, to finance their own pro

ceedings.

[1] The appellants contend that chapters 33 and 36

are: (1) penal statutes and should be strictly construed;

(2) that the statutes are vague and ambiguous; (3) that

the language of the statutes cannot be construed to apply

to their activities; and in addition the NAACP says (4)

if the statutes are construed to apply to their activities

they are unconstitutional and void because they deny to it,

its officers, employees, members, contributors, affiliates

and attorneys the rights of freedom of speech and as

sembly, equal protection of the laws and due process of

law under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

Chapter 33 amends and re-enacts §§ 54-74, 54-78 and 54-

79, Code of 1950. The pertinent parts of the chapter, with

the amended parts in italics, are set out in the margin

below.2 These sections deal with solicitation of any legal

2 Be it enacted by the General Assembly of Virginia:

1. That at 54-74, 54-78 and 54-79 of the Code of Virginia be

amended and re-enacted as follows:

§ 54-74.

* * * *

(6 ) “Any malpractice, or any unlawful or dishonest or unworthy

or corrupt or unprofessional conduct” , as used in this section, shall be

construed to include the improper solicitation of any legal or profes

sional business or employment, either directly or indirectly, or the

acceptance of employment, retainer, compensation or costs from any

person, partnership, corporation, organization or association with

knowledge that such person, partnership, corporation, organization

or association has violated any provision of Article 7 of this chapter,

[Continued on page 12a]

12a

or professional business or employment, either directly or

indirectly, and provide for the disbarment of attorneys

[Continued from page 11a]

or the failure, without sufficient cause, within a reasonable time after

demand, of any attorney at law, to pay over and deliver to the person

entitled thereto, any money, security or other property, which has

come into his hands as such attorney; provided, however, that nothing

contained in this Article shall be construed to in any way prohibit

any attorney from accepting employment to defend any person, part

nership, corporation, organisation or association accused of violat

ing the provisions of Article 7 of this chapter.

* * *

§ 54-78. As used in this article:

(1 ) A “ runner” or “ capper” is any person, corporation, partner

ship or association acting in any manner or in any capacity as an

agent for an attorney at law within this State or for any person, part

nership, corporation, organisation or association which employs,

retains or compensates any attorney at law in connection with any

judicial proceeding in which such person, partnership, corporation,

organization or association is not a party and in which it has no

pecuniary right or liability, in the solicitation or procurement of

business for such attorney at law * or for such person, partnership,

corporation, organisation or association m connection with any

judicial proceedings for which such attorney or such person, part

nership, corporation, organization or association is employed, retained

or compensated.

The fact that any person, partnership, corporation, arganization

or association is a party to any judicial proceeding shall not authorise

any runner or capper to solicit or procure business for such person,

partnership, corporation, organisation or association, or any attorney

at law employed, retained or compensated by such person, partner

ship, corporation, organisation or association.

(2 ) An “ agent” is one who represents another in dealing with a

third person or persons.

§ 54-79. It shall be unlawful for any person, corporation, part

nership or association to act as a runner or capper * as defined in

§ 54-78 to solicit any business for * an attorney at law or such per

son, partnership, corporation, organization or association, in and

about the State prisons, county jails, city jails, city prisons, or other