Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1974. 9e9a6461-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/60719dbf-09dd-47b0-aeb5-eae57c1f1449/albemarle-paper-company-v-moody-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

t

Page

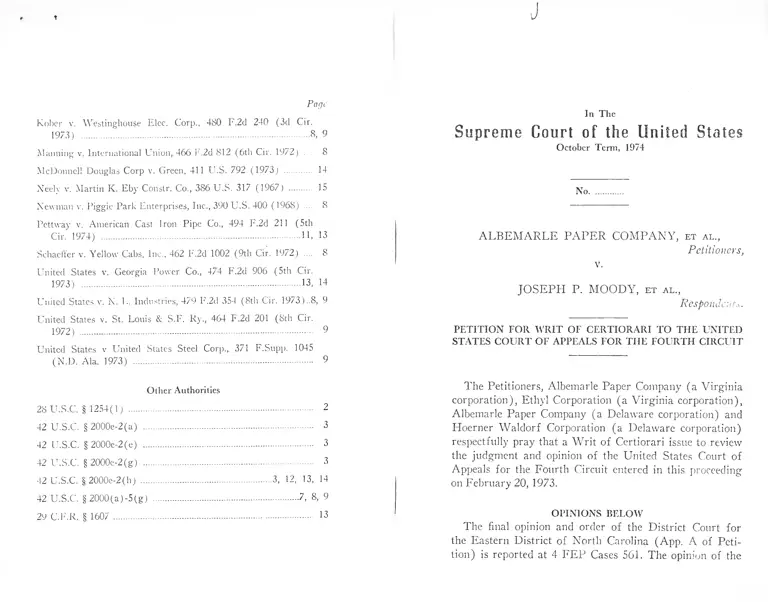

Kober v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 480 F.2d 240 (3d Cir.

1973) ............................................................................................ 8, 9

Manning v. International Union, 466 I'.2d 812 (6th Cir. 1972) .... 8

McDonnell Douglas Corp v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) ........... 14

Neely v. Martin K. Eby Conslr. Co., 386 U.S. 317 (1967) ......... 15

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968) .... 8

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th

Cir.' 1974) ................................................................................ 11, 13

Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (9th Cir. 1972) .... 8

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir.

1973) ........................................................................................ 13, 14

United States v. N. 1-. Industries, 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973)..8, 9

United States v. St. Louis & S.F. Ry., 464 P.2d 201 (8th Cir.

1972) .............................................................................................. 9

United States v United States Steel Corp., 371 F.Supp. 1045

(N.D. Ala. 1973) ........................................................................ 9

Other Authorities

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) .......................................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a).................................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e) .................................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(g) .................................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) .....................................................3, 12, 13, 14

42 U.S.C. § 2000(a)-5(g) ...........................................................7, 8, 9

29 C.F.R. § 1607 ................................................................................ 13

J

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1974

No.

ALBEMARLE PAPER COMPANY, et al„

Petitioners,

v.

JOSEPH P. MOODY, et al .,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

The Petitioners, Albemarle Paper Company (a Virginia

corporation), Ethyl Corporation (a Virginia corporation),

Albemarle Paper Company (a Delaware corporation) and

Hoerner Waldorf Corporation (a Delaware corporation)

respectfully pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment and opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit entered in this proceeding

on February 20, 1973.

OPINIONS BELOW

The final opinion and order of the District Court for

the Eastern District of North Carolina (App. A of Peti

tion) is reported at 4 FEP Cases 561. The opinion of the

2

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

(App. B of Petition) is reported at 474 F.2d 134.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit was entered on February 20, 1973. A timely peti

tion for rehearing en banc was granted on June 25, 1973.

After briefing to and oral argument before the en banc

court, a question of appellate procedure was certified to this

Court by the Court of Appeals on December 6, 1973. The

opinion of this Court on the question certified was delivered

on June 17, 1974. Pursuant thereto, the Court of Appeals,

on July 22, 1974, vacated its earlier order granting the

petition for rehearing en banc and denied Petitioner’s

petition for rehearing. This petition for certiorari was

filed within 90 days of that date. This Court’s jurisdiction

is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether this Court should resolve a conflict among

the Circuits as to whether, in cases under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, the District Courts have tradi

tional equitable discretion to determine whether back pay is

an appropriate remedy.

2. Whether a class action for back pay under Rule 23

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is inherently in

consistent with the Congressional intent behind the remedial

provisions of Title VII, particularly as to class members

who did not file a prior written complaint with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission.

3. Whether the decision below misconstrues this Court’s

decision in Griggs v. Duke Denver Co., 401 U.S. 424, in a

manner which effectively precludes the use of job-validated

3

employment testing and nullifies the Congressional intent

reflected in 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h).

4. Whether the decision below, in ordering the entry of

specific injunctive relief against Petitioners’ use of testing,

improperly usurps the power of the District Court on

remand.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The relevant statutory provisions, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

2(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) and

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), are set out in Appendix C. The

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ( “EEOC” )

guidelines on employee selection procedures appear at 29

CFR § 1607.

STATEMENT OE TEIE CASE

On August 25, 1966,1 four black employees of Peti

tioner’s Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina pulp and pape

mill brought this private class action under Title VII o

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000-e et seq

( “Title V II” ) against Albemarle Paper Company ( “Albe

marle-Virginia”), a Virginia corporation2 and Halifav

1 The employer was first advised of the fact that it had been

charged with discriminatory conduct on August 11, 1966, at which

time it was served with the Respondents’ charges and was given until

August 26, 1966, to respond to the charges. Thus, the complaint

herein was filed, pursuant to then applicable procedural requirements

before the employer was afforded any opportunity for conciliation

2 Albemarle-Virginia is a subsidiary of Ethyl Corporation. In 196'

the assets of Albemarle-Virginia were sold to Albemarle Paper Com

pany (“Albemarle-Delaware” ), a Delaware corporation and a suh

sidiary of Hoerner Waldorf Corporation. Ethyl Corporation, All

marle-Delaware and Hoerner Waldorf Corporation were added

parties defendant in 1970. The interests of the corporate defendan

coincide on the issues raised herein and they are jointly referred t

as “Petitioners.” For convenience, the term “Petitioner” is used

referring to the employer of Respondents.

4

Local No. 425, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO (the “Union” ). The complaint alleged various

racially discriminatory practices at the mill, including the

implementation of a discriminatory seniority system em

bodied in the collective bargaining agreement. Over Petition

er’s objection, Respondents were allowed to proceed as repre

sentatives of a broad class of black employees who did not

file written complaints with the EEOC prior to commence

ment of this action. 271 F.Supp 27.

The Roanoke Rapids mill commenced operations m 1907,

but it was not until the 1950’s that mechanization and the

addition of modern paper machines converted the fa

cility into a sophisticated and complex paper mill. Like

all paper mills, the Roanoke Rapids mill has been organized

on a departmental basis,3 and the seniority provisions of

Petitioner’s collective bargaining agreements with the

Union have reflected this departmental sti ucture.

Modernization of the Roanoke Rapids mill created the

need for a more highly skilled work force. To meet this

need, in about 1956, Petitioner instituted a personnel screen

ing program for use in the selection of employees for jobs

created by the installation of new machinery. As part of this

program, Petitioner made successful completion of certain

ability tests a prerequisite for entry into certain skilled lines

of progression.4

3 Each department is organized into one or more lines of progres

sion into which employees can enter and move up into more demand

ing jobs as vacancies occur, on the basis of seniority, ability and

experience Entry into a departmental line of progression is generally

from the Extra Board, introduced for the purpose of maintaining a

reservoir of employees who would be available to staff entry level jobs

in the various lines of progression.

4 The Revised Beta test, a professionally developed non-verbal test

designed to measure the intelligence of illiterates, was adopted in 1956.

Thereafter, in 1963, Petitioner also began using as a requirement for

entry into’certain skilled lines of progression the Wonderlic test.

Series A and B, professionally developed and widely used tests of

verbal skills.

5

Since the passage of Title VII, Petitioner has taken

many steps to insure that its employment practices comply

with federal law. Among other things, significant changes

were made in the seniority system embodied in Petitioner’s

collective bargaining agreement. In the 1968 contract, Peti

tioner and the Union eliminated rigid departmental seniority

and adopted a form of plant-wide seniority.6 Then, in 1971,

prior to trial, Petitioner and the Union advised the District

Court that they had no objection to the entry of a decree

permitting black employees to use “plant seniority” for the

purpose of advancement. The substance of the proffered

decree was adopted by the District Court.

Petitioner also took steps to insure that its use of tests

was in conformity with the law. After this Court’s decision

in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), Peti

tioner retained an expert to conduct a validation study. This

study showed a positive correlation between test results

and performance on the job.6

Until 1970 this action was one seeking exclusively class

wide injunctive relief, with Respondents having expressly

abandoned any claim for class-wide back pay in order

to insure qualification of the case as a class action. Never

theless, in 1970 Respondents asserted that they were in

5 The 1968 contract afforded a transferring employee seniority in

the new department equal to that held in his last job. The 1968

contract also granted “red circle rates,” whereby a transferring em

ployee would be entitled to the pay rate of the job from which he

transferred until he moved high enough in the new line of progres

sion to reach an equal pay level.

6 The study was conducted by use of the “concurrent validation”

method. Petitioner’s expert selected, on the basis of his analysis and

knowledge of the nature and content of the jobs, ten skill-related

job groupings as typical of jobs in the skilled lines of progression.

Each employee in each group was rated in comparison with each

other employee in the group to obtain a ranking of job performance

and statistical correlation was performed to determine correlation

between job performance and test results.

6

fact seeking both injunctive and back pay relief on behalf

of the class. , ^ ,

After trial in July and August 1971, the District Court

issued its Memorandum Opinion and Order. The District

Court entered a decree providing for the type of modifica

tion of the seniority system which had been consented to by

Petitioner prior to trial.

But the District Court rejected the charge that Be -

tinner’s use of the Revised Beta and Wonderhc tests .n

certain skilled lines of progression violated Title M l, a

the District Court, expressly exercising its discretion as to

the appropriate remedy, ruled that the members of the

Respondent class were not entitled to back pay. _

A panel consisting of two senior judges (Bryan, J. an

Boreman, J.) and one regular judge (Craven J.) reverse

the District Court on both the testing and back pay issues.

As to each issue, the decision was divided, with a dif eien

combination of the panel providing the necessary 2-1 ma

jority. Thus, two circuit court judges held that Petitioner

had violated Title VII by using the tests, and a diftcien

majority also reversed the District Court m its denial of

h^Following the panel’s decision, the Fourth Circuit granted

Petitioner’s request for a rehearing en banc. Supplement

briefs were filed by the parties and oral argument was he

before the cn banc court. Thereafter, upon certification of

the question by the Fourth Circuit, this Court held that the

two senior judges who were members of the initial panel

could not properly vote to grant rehearing en banc. There-

however, that this requirement had been waived since

incumbent employees lured prior to July Z, tv .

7

after, the Fourth Circuit vacated its order granting the

rehearing, thereby reinstating the divided decision of the

original three-judge panel.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Decision Below Regarding Back Pay Conflicts With The Deci

sions Of Other Courts Of Appeals, And Raises Critical Questions

Concerning The Remedial Provisions Of Title VII.

Title VII provides that if the District Court finds that

an employer has intentionally engaged in an unlawful em

ployment practice, it “may enjoin the respondent from en

gaging in such unlawful employment practice, and order

such affirmative action as may be appropriate, which may

include, but is not limited to, reinstatement or hiring of

employees, with or without back pay.” Section 706(g), 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g). This case presents fundamental ques

tions concerning the back pay remedy, as to which there

has been a conflicting array of decisions by the various

Courts of Appeals.

1. The grant of remedial authority in Section 706(g)

is inherently equitable in nature and the question of back

pay is expressly left to the discretion of the district court.

The statutory directive is that the district court, upon find

ing a Title VII violation “may enjoin the . . . practice, and

order such affirmative relief as may be appropriate, which

may include . . . reinstatement . . . zvith or ivithout back

pay.”

In distinguishing between Title VII and Title VIII

actions on the question whether a jury trial is mandatory,

this Court has observed that, “In Title VII cases, also, the

courts have relied on the fact that the decision whether to

award back pay is committed to the discretion of the trial

judge.” Curtis v. Loether, 39 L.Ed. 260, 268 (1974). Peti-

8

tioner submits that this observation is the only correct

interpretation of the Congressional intent underlying Sec

tion 706(g). ,

The decision below virtually eliminates the trial court s

discretion to fashion appropriate relief under Section

706(g) for the Fourth Circuit panel held that a District

Court must award back pay “unless special circumstances

would render such an award unjust.”8 _

Other Circuit Court decisions have applied a conflicting

standard, affirming trial court back pay denials in the ab

sence of an abuse of discretion measured by traditional

equitable standards. See Manning v. International Union

466 F.2d 812, 816 (6th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,,410 IIS .

946 (1973) ; Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 100-,

1006-1008 (9th Cir. 1972) ; U. S. v. N. L. Industries, Inc.,

479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973). And the Third Circuit in

Kober v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 480 F.2d 240, 246-47

(3rd Cir 1973), recently considered both lines of cases

and expressly rejected the Fourth Circuit’s “special circum

stances” rule.9

The “special circumstances” rule derives from A ernnan

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968),

8 A panel of the Fifth Circuit has since adopted the “special cir

cumstances” standard in Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F 2d 211, 252-253 (1974), which appears to be the only other

case where a discretionary denial of back pay was reversed on

anneal Similarly restrictive standards were set forth m Head v. *S,n Roller Bearing Co.. 4S6 F.2d 870, 876 ( 6th Cm 1973) ( o r,

“exceptional rtwumstances" warrant back pay deiml) ’A - F ls th Cir

v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1375 (3th u .

1974) (plaintiffs “presumptively entitled to back pay).

9 There is also evidence of a conflict within the Fourth Circuit. In

its prior certification to this Court in this proceeding the Fourth

Circuit stated:

“If the en banc court reaches the merits, the tentative vote is that

it will modify the panel decision with respect to an award of

back pay.”

9

dealing with the grant of attorneys’ fees to successful

plaintiffs in Title II cases. However, far more complex

equitable factors affect the question whether back pay is an

appropriate remedy in a Title V ll action. See, e.g., United

States v. St. Louis & S.F. Ry., 464 F.2d 301, 311 (8th

Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1116 (1973); United

States v. United States Steel Corp., 371 F. Supp. 1045

(N.D. Ala. 1973). And a rule which makes an award of

back pay flow almost automatically from any finding of an

unlawful employment practice is likely to inhibit conciliation

and to discourage the prompt resolution of disputes through

the entry of injunctive relief by consent (as occurred with

respect to the seniority issues in this case), all in contraven

tion of the basic policies underlying Title VII.

The question of when back pay should be awarded in

Title VII actions is of widespread and compelling sig

nificance. Ignoring the plain language of Section 706(g),

the Fourth Circuit has sharply curtailed the discretionary

power of the District Court to fashion appropriate relief.

The circuits are in conflict and this important issue should

be resolved by this Court.

2. The extent to which the decision below emasculates

the District Court’s remedial discretion in Title VII cases is

graphically illustrated by the manner in which the panel

majority categorically rejected the special circumstances

found by the Distrit Court to justify the denial of back

pay. First, the Fourth Circuit panel ruled that Petitioner’s

good faith was totally irrelevant to the question of back

pay. While no court has apparently denied back pay solely

because of defendant’s good faith, a number of courts have

relied upon defendant’s good faith as a relevant factor in

denying back pay. See Kober v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp.,

supra; United States v. St. Louis & S.F. Ry., supra; United

States v. Ar. L. Industries, Inc., supra.

10

Second, the Fourth Circuit panel rejected the District

Court’s finding that Petitioner was prejudiced by Respond

ents’ tardy claim for back pay, which came four years after

the action was commenced, and after the Roanoke Rapids

mill had been acquired by Albemarle-Delaware on the as

sumption that this action only involved a claim for injunc

tive relief.10 The panel majority reasoned that the Peti

tioner’s defenses are the same whether or not back pay is an

issue. But that overlooks the real prejudice to Petitioner.

Had Petitioner been put on notice that back pay claims were

involved, it may not have allowed Respondents to delay more

than five years in bringing this case on for trial, there

by compounding its back pay exposure. _ Further^ had

Respondents made known their back pay claims m a timely

manner, Petitioner and the Union could have sought court

sanction for the changes they voluntarily and unilaterally

made in the seniority system in 1968, so as to limit their

potential back pay exposure. Finally, Petitioner is clearly

prejudiced if back pay is allowed to the entire class after

Respondents had earlier used the absence of such claims as

justification for allowing the litigation to proceed as a class

action. In this situation, even if the “special circumstances

rule is generally appropriate, the District Court was well

10 It was not merely that this issue had not specifically been raised.

Rather, Respondents had specifically and categorically represented

that they were not seeking back pay. In an effort to defeat Petitioner s

motion to dismiss the class claims and for summary judgment (an

effort which was successful), Respondents represented :

“It is important to understand the exact nature of the class

relief being sought by Plaintiffs. No money damages are sought

for any member of the class not before the Courts nor is spe

cific relief sought for any member of the class not before the

Court. The only relief sought for the class as a whole is that

defendants be enjoined from treating the class as a separate

group and discriminating against the class as a whole in the

future.”

11

within its discretion in denying Respondents’ tardy claim

for back pay, and the Fourth Circuit panel exceeded the

proper scope of appellate review in substituting its own

judgment for that of the trier of facts.

3. The decision below is one of a number of recent

lower court cases which could be read to authorize class-widi

back pay in Title VII actions where some members of the

class did not file a charge with the EEOC prior to com

mencement of the lawsuit. See, e.g., Pettway v. American

Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d at 256-258.

The EEOC complaint and conciliation procedures built

into Title VII were an integral part of the legislative com

promise which led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. After Federal Rule 23 was liberalized in 1966.

the lower courts rather quickly reached a concensus that

class actions seeking injunctive relief are appropriate unde;

Title VII. Such a decision has relatively little impact, since

injunctive relief in favor of the individual plaintiff normally

will benefit all members of the class whether or not they

are parties to the lawsuit. For example, Petitioner had littl*

reason to be concerned on appeal with the District Court'

preliminary order overruling Petitioner’s objection to th<

class action, since the District Court ultimately denied back

pay relief.

A class action for back pay, however, is quite anothei

matter, both because of its economic impact on the de

fendant, and because of the administrative burdens it place.-

on a federal court, which must process untold numbers o.

individual monetary claims without the assistance of th-

EEOC complaint and conciliation procedures. This Com

should grant certiorari to review whether a class actio

for back pay under modern Rule 23 is inherently inco:

sistent with the Congressional intent behind the remedia

provisions of Title VII.

12

The Decision Below Regarding Testing Misconstrues Griggs In A

Manner Which Effectively Precludes The Use Of Job Validated

Employment Testing And Nullifies The Congressional Intent

Reflected In 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h).

In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971),

this Court held that the use of a testing or measuring de

vice as a controlling force in employment or promotion

violates Title VII if the device disqualifies blacks at a

substantially higher rate, unless it is established that the

test is “demonstrably a reasonable measure of job per

formance.” This Court recognized that the use of suitably

job-related tests was expressly sanctioned by Congress in

Section 703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h).

In Griggs, the employer had made no effort to “validate”

its testing and educational requirements in accordance with

professionally accepted methods of measuring the correla

tion between test results and job performance. On the other

hand, Petitioner, following this Court’s decision in Griggs,

and in order to demonstrate that its tests did accurately

measure job performance, retained a nationally recognized

expert in the field of industrial psychology, who conducted

a validation study11 of Petitioner’s tests.

Approving the validation procedures adopted by Peti

tioner’s expert, and noting that the study results showed

“positive correlations of a statistically significant natuie,

the District Court found “that both the Beta and Wonderlic

A tests can be reasonably used for both hiring and promo

tion for most of the jobs in this mill.” (A. 18) The Dis

trict Court also concluded that “ [t]he defendants have

carried the burden of proof in proving that these tests

‘are necessary for the safe and efficient operation of the

business’ and are, therefore, permitted by the Act.” (A. 24)

11 The procedures employed in the validation study were sum

marized in the District Court s opinion, A. 17, 18.

13

The three judge panel of the Fourth Circuit, with one

strong dissent, held that the District Court “erred in up

holding the validity of the pre-employment tests and in

refusing to enjoin their use,” relying on the failure to in

clude in Petitioner’s validation study “some form of job

analysis resulting in specific and objective criteria for super

visory ratings,” as supposedly required by the EEOC

testing guidelines, 29 C.F.R. § 1607. The Circuit Court’s

decision thus raises a fundamental question as to the proper

application of Section 703(h) and this Court’s decision

in Griggs.

While this Court in Griggs endorsed the EEOC guidelines

as “expressing the will of Congress,” 401 U.S. at 434, the

Fourth Circuit majority’s requirement of detailed and rigid

compliance with the EEOC criteria for validation studies

is inconsistent with this Court’s recent decision in Espinoza

v. Farah Mfg. Co., 414 U.S. 86 (1973). Likewise, th

decision below conflicts with decisions in other Circuits

which have refused to require compliance with each tech

nical form of validation procedure set out in the guidelines

United Slates v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cii

1973) ;12 Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972)

Test validation is a professional exercise in statistical

prediction. Perfection is inherently unattainable, and thi

practical realities of a particular employment setting must

inevitably dictate the precise validation technique to be used.

Thus, it is unrealistic to read the detailed and technical

EEOC guidelines as establishing a mechanical structure

which all validation efforts must satisfy. ' rhe ultimate result

of the decision below would surely be to deny employers a

realistic opportunity to establish that their tests are “de-

12 The Fifth Circuit has since suggested, in dictum, that the guide

lines had been found to be mandatory in the Georgia Power case.

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra.

14

monstrably a reasonable measure of job performance.” Such

a result would render Section 703(h) a nullity and frustrate

the intent of Congress and of this Court’s decision in

Griggs.

The Decision Below Improperly Usurps The Power Of The District

Court On Remand.

The decision below includes a directive that the District

Court enjoin Petitioner’s use of its tests. Given the na

ture of the Fourth Circuit’s ruling, this is an intrusion on

the proper function of the District Court. The Fourth Cir

cuit did not hold that Petitioner’s tests were not job related

or that the tests could not be validated. It held only that

the prior attempt at validation was procedurally inadequate.

Even if that ruling was correct, it does not follow that Peti

tioner cannot ultimately rebut the prima facie case of dis

crimination by properly validating the tests. Compare Mc

Donnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

Under these circumstances, the Court of Appeals should

have remanded to the District Court as was done in United

States v. Georgia Power Co., supra. The court therein

noted:

“ [Standards for testing validity comprise anew and

complicated area of the law. While the Hite Study

did not demonstrate compliance with the Act, we

hesitate to penalize this litigant, the first to confront

such a demanding burden of proof, for failing to intro

duce a more rigorous study. Had our standards been

articulated at the time of trial, it may be that the com

pany could have proven its compliance. Therefore,

rather than now proscribing the testing program which

Georgia Power has used, we remand this phase of the

case to the trial court with directions to permit the

company a reasonably prompt opportunity to validate

15

the testing program applied to the plaintiffs, in accord

ance with the principles enunciated in this opinion.”

474 F.2d at 917-18.

The question on remand should be whether the equities favor

an immediate injunction against Petitioner’s use of tests,

which carries all the ramifications "i a finding of discrimi

nation, or favor further proceedin'. ; designed to determine

whether the possible deficiencies ; ■ the validation study

could be corrected. This is a qiu >n of potentially great

importance which the Court of .’ , ' als should have left in

the first instance to the discretion lie District Court. Cf.

Neely v. Martin K. Eby Constr. ( 3 % U.S. 317 ( 1967) ;

Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Elc. corp., 356 U.S. 525

(1958).

CONCLUS

For these reasons, a writ of c iiorari should be issued

to review the judgment and opini . of the Fourth Circuit.

Respectfully sub’ ’ 'led,

F rancis V. Lowden, J r.

700 East Main Street

Richmond. Virginia23219

Gordon G. B usdicker

1300 Northwestern Bank Bldg.

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55402

Counsel for Petitioner

October 7, 1974