Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1981. e78c4597-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/609fe3cd-f380-4868-83b8-d6c06cd45740/washington-state-v-seattle-school-district-no-1-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

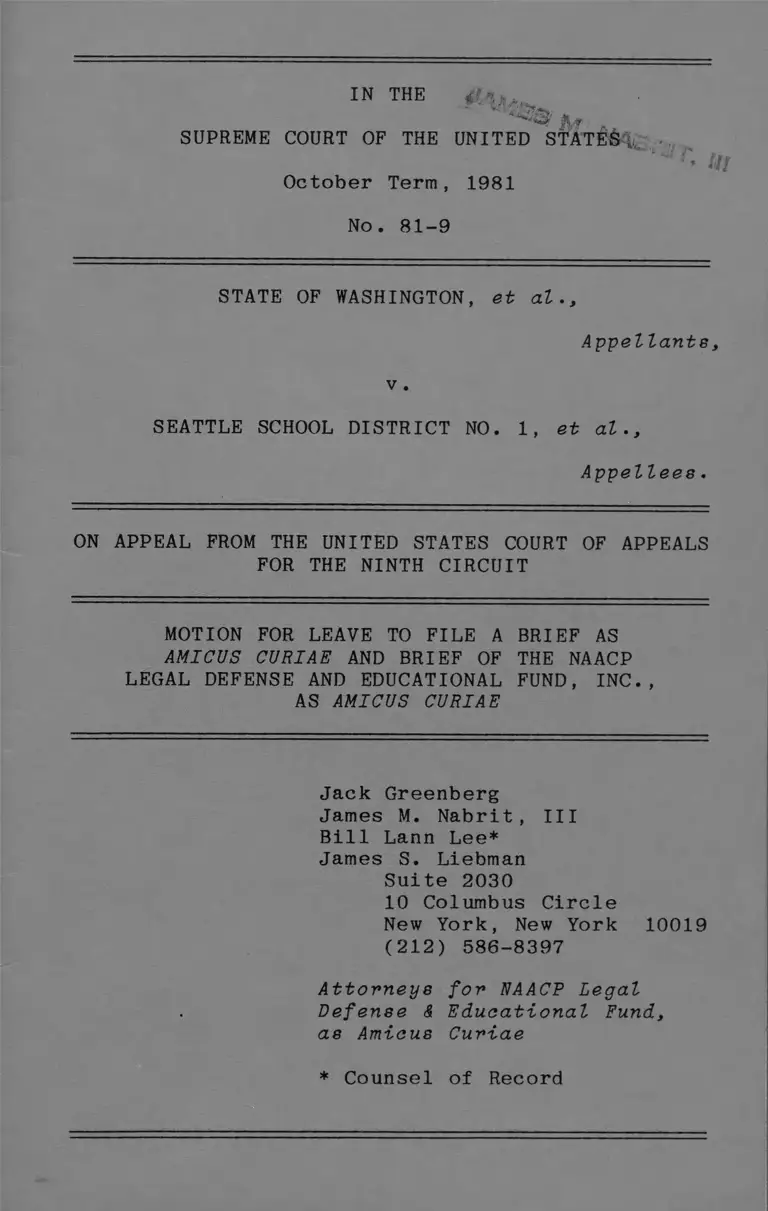

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

October Term, 1981

No. 81-9

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al.,

Appellants,

v .

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AS

AMICUS CURIAE AND BRIEF OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Bill Lann Lee*

James S. Liebman

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

defense & Educational Fund,

as Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

INDEX

Table of Authorities ............. iii

Motion For Leave For NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Page

Inc., To File A Brief

Amicus Curiae ............... 1

Question Presented ............... 6

Brief For the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

as Amicus Curiae ............ 7

Summary of Argument .............. 7

Argument ......................... 9

I. Initiative 350 Violates

The Fourteenth Amendment's

Most Basic Prohibition By

Structuring The Political

Process So That Governmental

Action Benefiting The Minor

ity Victims Of School Segre

gation Is More Difficult To

Achieve Than Governmental

Action Benefiting All Other

Citizens ...................... 9

A. Racial Classifica

tions Distorting the

Political Process ......... 12

B. Hunter v. Erickson.... 15

i

Page

C. Nyguist v. Lee ........ 27

D. Initiative 350 ........ 34

II. Racial Integration Of Public Education In Appel

lee Local Districts, Which

Initiative 350 Nonneutrally

Frustrates, Is A Legitimate,

Indeed Pressing, Political

Objective of Black Citizens

In Appellee School Districts ... 47

Conclusion ....................... 56

• •

- l i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19 ( 1969) ...................... 3,49

Avery v. Midland County,

390 U.S. 474 ( 1968 ) ............ 13

Bollina v. Sharpe,

347 U.S. 499 ( 1954) ............ 10

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 ( 1954) ............ 3

Crawford v. Board of Education

of the City of Los Anqeles,

No. 8 1-38 ........... 23

Citizens Against Mandatory

Bussinq v. Palmason,

495 P. 2d 657 (Wash. 1972) ....... 36,37

Columbus Board of Education

v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ...................... 3,5,23,24

31,54

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958) ...................... 3

Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406(1977) ......................... 18

Dunn v. Blumstein,

405 U.S. 330 ( 1972) ............ 12

n i

Page

Evans v. Buchanan, 398

F. Supp. 428 (D. Del.),

aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 (1975) ..... 30

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S.

339 ( 1 880) ..................... 10

Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S.

291 ( 1 978) ..................... 1 1

Green v. County School Board, 391U.S. 430 ( 1968) ............. 3

Harper v. Virginia Board of Electors, 383 U.S.

663 ( 1 966) ..................... 12

Hunter v. Erickson,393 U.S. 385 ( 1969) ............ passim

In re Griffiths,

413 U.S. 717 ( 1973) ............ 1 1

James v. Valtierra,402 U.S. 1 37 ( 1971 ) ............ 44

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. 1 89 ( 1 973) ......... 3

Lovinq v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 ( 1967) .............. 10

Massachusetts Board of

Retirement v. Murgia,

427 U.S. 307 ( 1976) ............ 1 1

McDaniel v. Barresif

402 U.S. 39 ( 1971 ) ............. 48

McLauqhlin v. Florida,

379 U.S. 39 ( 1971 ) ............. 10

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717 ( 1974) ............ 27,35

Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 ( 1980) ........ 1 1 , 1 4,22,45

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v.

Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (1980) .... 5

Nixon v. Herndon,

273 U.S. 536 ( 1927) ........... 1 1,1 2,31

North Carolina State Board

of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 ( 1971 ) ............ 24,28,49

Nyguist v. Lee. 401 U.S. 935 aff 'g, 318 F. Supp. 710

(W.D.N.Y. 1970) ................ passim

Personnel Administrator v.Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

( 1979) ......................... 22,44

Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 ( 1978) ................ 47

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.533 ( 1964) ..................... 13

Page

v

Page

San Antonio School Dist. v.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1

( 1973 ) ...................... ... 11,25,34

Seattle School Dist. No. 1

v. Washington, 473 F. Supp.996 (W.D. Wash. 1979), aff'd,

633 F.2d 1338 (9th Cir.1980) ....................... .. 36,37,40,

41,42

Slaughterhouse Cases,83 U.S. 36 ( 1 973) ........... . 10

State ex rel. Lukens v.Spokane School District 81,

147 Wash. 467 ( 1928) ........ . 36

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 ( 1880) ......... . 10

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1 (1971) .................... .. 3,28,41, 48,49

Takahashi v. Fish and Game

Comm'n, 334 U.S. 410 (1948) ... 11

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S.

144 ( 1 938) .............. .... 10,25

Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing

Authority, 429 U.S. 252 (1977) .......................

- vi

Page

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 ( 1976) ..................... 44

White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 ( 1973) ..................... 1 1,1 2

Wright v. Council of the

City of Emporia, 407 U.S.451 ( 1972) ..................... 23,24

Other Authorities:

Buses: Backbone of Urban Transit,The American City, Dec. 1974 .... 50

120 Cong. Rec. 8757 ( 1974) ........ 50

Davis, Bussing, in 2 R. Crain,

et al., Southern Schools: An

Evaluation of the Emergency

School Assistance Program and

of School Desegregation (1973)... 51

Department of Transportation,

Transportation of School

Children (1972) ................ 50

G. Gunther, Cases and Materials

on Constitutional Law

(9th Ed. 1975) ................. 26

W. Hawley, et al., 1 Assessment

of Current Knowledge About The Effectiveness of School

Desegregation Strategies,

Strategies for Effective Desegregation: A Synthesis

of Findings (1981) ....

- vii -

52,53,54

Page

Hawley, "The False Premises of

Anti-Busing Legislation,"

testimony before the Subcom.

on Separation of Powers,

Sen. Com. on the Judiciary,97th Cong., 1st Sess.

(September 30, 1981) ......... 52,54,55

Metropolitan Applied Research

Center, Busing Task Force

Fact Book ( 1 972) .............. . 49

The New York Times,

Dec. 4 , 1 980 .................. . 50

National Association of Motor

Bus Owners, Bus Facts (39th

ed. 1 972) ..................... . 50

G. Orfield, Must We Bus? (1978) ... 49,50

C. Rossell, et al., 5 Assessment

of Current Knowledge About the Effectiveness of School

Desegregation Strategies,

A Review of the Empirical

Research on Desegregation:

Community Response, Race Relations, Academic Achieve

ment and Resegregation (1981) .. 53,54,55

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

Public Knowledge and Busing

Opposition ( 1973) ............. . 50

Zoloth, The Impact of Busing on

Student Achievement, 7 Growth

& Change 45 (July 1976) ....... 51

- viii

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

No. 81-9

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al. ,

Appellants,

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States Court

of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE FOR THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc., hereby respectfully

moves for leave to file the attached brief

amicus curiae in this case. Counsel for

appellees, the United States, and the

Seattle intervenor-plaintiffs-appellees

2

have consented to the filing of the at

tached brief. The consent of the attorney

for appellants was requested, but refused,

thus necessitating this moion.

1. The NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., (hereinafter "LDF")

is a non-profit corporation established

under the laws of the State of New York.

It was formed to assist black persons to

secure their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter

declares that its purposes include render

ing legal services gratuitously to black

persons suffering injustice by reason of

racial discrimination. LDF is independent

of other organizations and is supported by

contributions from the public.

2. For many years attorneys of the

Legal Defense Fund have represented par

ties in litigation before this Court and

3

the lower courts involving a variety of

race discrimination issues, including

lawsuits brought on behalf of black parents

and students to desegregate public schools.

E.g., Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

4 8 3 ( 1 9 5 4.)? Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958); Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968); Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969);

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Ed

ucation , 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Keyes v. School

District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 ( 1 973). The

Legal Defense Fund also has participated as

amicus curiae in numerous desegregation

cases in this Court. E.g. , Columbus Board

of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979); Regents of the University of Cali

fornia v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

4

3. Amicus also represents black

parents and school children in numerous

pending lower court cases. Those parents

and children have a particular interest and

concern in encouraging local school dis

tricts to undertake voluntary "affirmative

action" programs to desegregate their

student bodies and facilities without

undergoing full-blown litigation, which is

often taxing, time-consuming and expensive.

LDF also has an interest in safeguarding

the right of black parents and other black

citizens, as exercised here, to seek

redress of grievances and to obtain favor

able governmental action through the

political process on the same basis as all

other citizens. As the attached brief

points out, amicus believes that both these

interests will be imperiled if Initivive

350 is upheld.

5

4. Amicus respectfully submits that

its long experience in school desegregation

matters and its familiarity with the

social-science data on the success of de

segregation remedies may assist the Court

*/in resolving this matter.“

jJV The sole objection of appellants' counsel to LDF's participation as amicus —

that LDF's perspective is represented here

by the Seattle, Washington Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP), one of several

plaintiff-intervenors -- is mistaken.

Although originally founded by the NAACP,

LDF has been a wholly separate organization

from the NAACP for over 20 years, with a separate Board of Directors, program of

operations, staff, office and budget.

Moreover, while the NAACP is participating

in this case solely on behalf of its members in Seattle, Washington, LDF seeks to parti

cipate in order to represent the interests

of its clients in school desegregation

litigation throughout the country. For

these reasons, LDF has been permitted to

participate as amicus curiae in cases in

which the NAACP was also amicus, e.g.,

Regents of the University of California v.

Bakke , supra, and Tn cases Tn wh i ch

NAACP attorneys represented one of the

parties, e.g., Columbus Board of Education

v. Penick, supra? New York Gaslight Club, Inc, v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (1980)."

6

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons,

amicus curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, Inc. prays that the attached

brief be permitted to be filed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BILL LANN LEE*

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212)586-8397

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund,

as Amicus Curiae

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does Initiative 350 violate the Four

teenth Amendment by structuring the politi

cal process of the State of Washington so

that governmental action benefiting the

minority victims of school segregation is

more difficult to achieve than governmental

action benefiting all other citizens?

7

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

No. 81-9

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States Court

of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amicus respectfully submits that this

appeal is governed by the fundamental Four

teenth Amendment principle that a state

must maintain political neutrality among

the races and may not burden minority-group

political participation by requiring racial

8

minorities to utilize more onerous means

than all other citizens to obtain govern

mental action on their behalves. Hunter

v, Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969); Nyguist

v. Lee, 401 U.S. 935 ( 1 97 1 ), af f 'g 318

F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y. 1 970 ). The fatal

constitutional defect of Initiative 350 is

that it is a "statute[] which structured]

the internal governmental process" in such

a way as to "make[] it more difficult for

racial ... minorities" than for all other

citizens to "further their political aims."

Hunter v, Erickson, supra, 393 U.S. at 393

(Harlan, J. , concurring). Because Hunter

and Nyguist v, Lee are dispositive, we

limit Part I of this brief to a discussion

of the application here of the principle

which animates those cases.

Part II briefly discusses the recent

social scientific data establishing that

desegregation of public schools is a

9

legitimate, indeed pressing, political

goal of minorities, which has succeeded

over the past fifteen years in drama

tically improving academic achievement

among blacks and race relations among all

students.

ARGUMENT

I

INITIATIVE 350 VIOLATES THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT'S MOST BASIC

PROHIBITION BY STRUCTURING THE

POLITICAL PROCESS SO THAT GOVERN

MENTAL ACTION BENEFITING THE MINORITY VICTIMS OF SCHOOL SEGREGATION IS MORE

DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE THAN GOVERN

MENTAL ACTION BENEFITING ALL OTHER

CITIZENS

In its most fundamental aspect, the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment forbids the States from passing

laws, not born of a compelling necessity,

that classify blacks or other racial

minorities differently, and less ad-

10

vantageously, than all other citizens,

Slaughterhouse Cases , 83 LJ.S. 36, 71

(1873); Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U.S. 303, 307-08 (1880); Ex parte Vir

g inia , 100 U.S. 339, 344-45 (1880);

Bolling v. Sharpe, 3 4*7 U.S. 499 (1954);

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192

(1964); Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 10

(1967). This deep mistrust of legislative

classifications singling out blacks or

other racial minorities derives from a re

cognition that "prejudice against discrete

and insular minorities" in this country

historically has been "a special condi-

dition, which tends seriously to curtail

the operation of those political pro

cesses ordinarily to be relied upon to

protect minorities ...." United States

v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144,

152 n.4 (1938). Because the Clause was

designed as an antidote to the "position

of political powerlessness ... [in] the

majoritarian political process" to which

blacks and other racial minorities have

been relegated in this country, San

Antonio School Dist, v. Rodriquez, 411

1/U.S. 1 , 28 ( 1973), its prohibitory force

falls heavily, perhaps most heavily, on

"laws which define the structure of poli

tical institutions" so as to classify

racial minorities less advantageously than

all other citizens. Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385, 393 ( 1969 ) (Harlan, J. , con-

curring); see Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55, 83-84 (1980) (Stevens, J. , concur-

ring); see e . g . , White v. Regester, 412

U.S. 755 (1973); Nixon v. Herndon, 273

U.S. 536 (1927).

V See Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S. 291,

294 (1978); Massachusetts Board of Retire

ment v. Murgia, 427 U.S. 307, 313 ( 1 976);

In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717, 721 ( 1973);

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Comm'n, 334 U.S. 410, 420 (1948).

12

A. Racial Classifications Distorting

the Political Process

Forbidden racial classifications im

pinging on the political process include,

for example, the simple denial to blacks

and other racial minorities of the fran

chise available to all other citizens. Cf.

Dunn v. Blumstein, 405 U.S. 330 (1972);

Harper v. Virginia Board of Electors, 383

2/U.S. 663 (1966).“

Similarly, it is fundamental to the

Equal Protection Clause that the States

may not unfavorably single out blacks or

other minorities in the political arena

by weighting their votes less heavily than

2 / Such a classification is no less obnoxious to the Fourteenth Amendment

because it disadvantages only some mem

bers of a racial minority — for example, by depriving only blacks who wish to vote

in the Democratic Party primary of the

ability to do so. E.g, White v. Regester,

supra; Nixon v. Herndon, supra.

13

the votes of all other persons — for

example, by affording blacks only one

representative for every 10,000 citizens,

while affording others one representative

for every 5,000 citizens. Cf. Avery v.

Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968).“

Finally, even where blacks and other

minorities are allowed the franchise and

representation equal to that afforded

other citizens, this Court has recognized

that the States offend the Fourteenth

Amendment's fundamental requirement of

political neutrality among the races when

they pass "statutes which structure the

internal governmental process" so as to

"make[] it more difficult for racial and

religious minorities [than for the rest of

3/ Again, such a classification violates the Fourteenth Amendment even if it does

not victimize all blacks but only, for

example, blacks living in urban areas.

Cf. Reynolds v, Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).

14

the citizenry] to further their political

aims." Hunter v. Erickson, supra, 393 U.S.

at 393 (Harlan, J. , concurring) (emphasis

added). For minority citizens are no less

politically powerless with the vote than

without it if the State has arranged the

internal mechanics of government so that

legitimate state action benefiting racial

minorities is structurally more difficult

to achieve than state action benefiting

other constituencies. See Mobile v. Bol

den , supra, 446 U.S. at 83-84 (Stevens, J.,

concurring).

In this light, for example, a state

law requiring a two-thirds majority for

legislation benefiting blacks, where a

simple majority suffices for all other

legislation, would clearly fall afoul of

the Fourteenth Amendment. So, too, would

a state law singling out only some blacks,

or some substantive area of governmental

15

benefit of particular interest to some

blacks, for disadvantageous treatment in

the political process. Such was the hold

ing of Hunter v. Erickson, supra.

B. Hunter v. Erickson

Hunter the municipal lawmaking

process in Akron, Ohio had in the past

been structured so that the City Council

could adopt any municipal ordinance re

lating to a legitimate goal of local

government — including, for example, the

regulation of real-property transactions

— by a majority vote, subject to a citi

zens' veto if (i) 10 percent of the elec

torate signed a petition calling for a

referendum on the ordinance, and (ii) a

majority of the City's electorate there

after disapproved the ordinance in a

general election. See 393 U.S. at 387?

jLd. at 393-94 (Harlan, J. , concurring).

16

Hunter involved a constitutional

j ..................... - '■ ■■ " ■ i

/

challenge to a city-charter amendment,

legislated by referendum, that partially

rearranged this structure. Under the

amendment, " [a]ny ordinance which regu

late [d] the use, sale [or] lease ... of

real property of any kind ... on the basis

of race, color, religion, national origin

or ancestry" not only had to secure the

votes of a majority of the City Council,

but also had to "be approved by a majority

of the electors voting on the question at

a regular or general election . . . ." _Id. at

387. All other municipal laws -- i.e .,

ordinances not regulating the sale or

lease of real property, and those regu

lating the sale or lease of real property

on some basis other than race — remained

subject to the preexisting, less onerous

legislative process.

17

The Court held that the charter

amendment violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In so doing, both Justice White for

the Court and Justice Harlan in concur

rence noted that the charter amendment (i)

was designed to rescind a fair-housing

ordinance passed by the City Council in

order to relieve racial and religious

minorities of housing discrimination, and

(ii) served to make the passage of muni

cipal legislation by the City Council more

difficult in the future by placing more

power directly in the hands of the elec

torate, and less in the hands of the city

government. But, as Justice Harlan's con

currence makes explicit, it was neither

of these facts alone that rendered the

4/amendment unconstitutional.- Rather, the

4/ In the first place, that blacks and

religious minorities had utilized the

18

law was unconstitutional because, by way

4/ continued

pre-existing political process to benefit themselves by extending their statutory

civil rights beyond what federal law re

quired did not render unconstitutional

the subsequent rescission of that action

through exercise of the same general

political process:

Statutes ... which are grounded

upon general democratic prin

ciple, do not violate the Equal

Protection Clause simply because

they occasionally operate to

disadvantage Negro political

interests. If a governmental

institution is to be fair, one

group cannot always be expected

to win. If the [Akron City]

Council's fair housing legis

lation were defeated at a refer

endum, Negroes would undoubtedly

lose an important political

battle, but they would not thereby

be denied equal protection.

Hunter v. Erickson, supra, 393 U.S. at 394

(Harlan, J. , concurring). Accord, id. at

390 n.5 (majority opinion). See Dayton

Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S.

406, 413-14 (1977) (school board's res

cission of a prior board's resolution

19

of a nonneutral subject-matter classifica

tion, it required minorities seeking

legislative protection from housing dis

crimination to surmount a referendum

hurdle that stood in the way of no other

4/ continued

initiating affirmative action to undo de?

facto segregation does not by itseFf

violate the Fourteenth Amendment).

Similarly, were a state or local

government to organize itself so that legislation, or even some racially neutral

species of legislation -- say that regu

lating all real estate transactions — is always difficult to pass, such a govern

mental structure would not necessarily

violate the Constitution even though it

might have the effect of hampering efforts

by blacks to pass fair-housing legislation.

Such a rule

obviously does not have the

purpose of protecting one par

ticular group to the detri

ment -of all others. It will

sometimes operate in favor of

one faction, sometimes in favor of another.

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. at 394 (Harlan.

J . , concurring).

20

general, or even housing-related, legis-

5/lation.

5/ Notably, the Akron law struck down in

Hunter was facially neutral, since it sub

jected ordinances regulating real estate

transactions "on the basis of race" to the

same before-the-fact referendum require

ment whether they benefited whites or

blacks. The Court concluded, however,

that the law's facial neutrality was a

transparent disguise for a nonneutral

classification drawn purely and clearly

along racial lines:

[AJlthough the law on its face treats Negro and white, Jew and

gentile in an identical manner,

the reality is that the law's impact falls on the minority.

The majority needs no protection

against discrimination and if it did, a referendum might be

bothersome but no more than

that. Like the law requiring

specification of candidates'

race on the ballot, Anderson v.

Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964),

[the Akron charter amendment]

places special burdens on racial

minorities within the govern

mental process. This is no more

permissible than denying them

the vote on an equal basis with others. The preamble to the

open housinq legislation which

was suspended by [the charter

amendment] ... recited that

the population of Akron consists

Because "the city of Akron ha[d] not

attempted to allocate governmental power

5/ continued

of "people of different race,

color, religion, ancestry or

national origin, many of whom live in circumscribed and segre

gated areas, under substandard,

unhealthful, unsafe, unsanitary and overcrowded conditions,

because of discrimination in the

sale, lease, rental and financing of housing." Such was

the situation in Akron. It is

against this background that the

referendum required by [the

charter amendment] ... must be

assessed.

Hunter v. Erickson, supra, 393 U.S. at 391

(citations omitted).

Since the classification covertly

drawn by the law was based upon race (as well as ethnicity and religion) alone, and

was not justified by a compelling neces

sity, the Court concluded that it violated

the Equal Protection Clause without refer

ence to the Akron electorate's motivation

for drawing it. Id. at 389 ("we need not

rest on [the Court's invidious-purpose

cases] to decide this case. Here, unlike

[in those cases] , there was an explicitly racial classification treating racial

housing matters different from other racial and housing matters")? _id. at 395

(Harlan, J., concurring). As the Court

22

on the basis of any general principle,"

Hunter v. Erickson, supra, 393 U.S. at 394

(Harlan, J., concurring), or to provide

"a political structure that treats all

individuals as equals," Mobile v. Bolden,

supra, 446 U.S. at 84 (Stevens, J., con

curring), but instead passed "a provision

that ha[d] the clear purpose of making it

more difficult for certain racial and

religious minorities to achieve legisla

tion that is in their interest," the

charter amendment violated the Fourteenth

Amendment in the absence of a compelling

justification. Hunter v.Erickson, 3 9 3

U.S. at 394 (Harlan, J., concurring).

5/ continued

subsequently reiterated in Personnel Ad

ministrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 274

(1979), it is only "[i]f the classification itself, covert or overt, is not based

upon [race]" that the courts must reach

"the second question ... whether the adverse eFFect reflects invidious [race-]

based discrimination" (emphasis added).

23

Hunter established that, while mem

bers of the political majority are free

to (i) utilize governmental processes

organized along a "general principle" to

rescind state action benefiting racial

6/minorities, and (ii) to subject them

selves and all others, including racial

6/ Of course, the invidiously motivated

rescission of a prior benefit to minorities does violate the Constitution. Such

is the case of Proposition 1 in California. See Crawford v. Board of Education of

the City of Los Angeles , N o . 8 1-38.

Similarly, state and local governments guilty of prior racial discrimina

tion have a continuing affirmative duty to remedy its consequences and accordingly

are not constitutionally free to withdraw

rights or benefits serving that remedial

purpose. E.g. , Columbus Board of Educa

tion v. PenlcET, 443 U.S. 449, 459 ( 1979); Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 ( 1 ) . In advance of Phase II of the present litigation, we assume

for purposes of argument that neither the State of Washington, nor any of the other

municipal governments involved, is guilty of prior racial discrimination.

Notably, a finding that Initiative

350 is unconstitutional would probably remove any need For Phase II, since

24

minorities, to an arduous process of

securing legislation or other governmental

action beneficial to themselves, including

by rearranging governmental power so that

more of it resides at one level (e . g . ,

with the electorate) and less at another

(e.g. , with local governmental officials),

members of the majority may not pass a law

depriving racial minorities of the bene

fits of the political process by subject

ing minorities, but not themselves ,

to structural or other political dis

abilities. Such a law is not "grounded in

6/ continued

Seattle's voluntarily adopted desegrega

tion plan moots any need for court-ordered

measures. On the other hand, under Penick

and Wright, supra, Initiative 350 cannot

finally be adjudged constitutional until

after Phase II determines whether (i) the

State of Washington or Seattle is under a

continuing duty to desegregate the schools

of Seattle, and (ii) whether the Initia

tive interferes with that duty. See North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971).

25

in neutral principle." Hunter v, Erickson,

393 U.S. at 395 (Harlan, J. , concurring).

By dividing the political process along

racial lines, it cements into the po

litical structure of the State the same

"special condition" — i.e., a "prejudice

against discrete and insular minorities

... which tends to curtail the operation

of the political process ordinarily to be

relied upon to protect minorities," United

States v. Carolene Products Co., supra,

304 U.S. at 152 n.4 — whose existence

justifies the Fourteenth Amendment's

"extraordinary protection" of blacks and

other minorities "from the majoritarian

political process." San Antonio School

Dist. v. Rodriquez, supra, 411 U.S. at

28.

The requirement that state political

processes be racially neutral is no

Fourteenth Amendment fellow traveler. It

26

is compelled by the same "basic prin

ciples," Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. at

396 (Harlan, J., concurring), lying at the

"core of the Fourteenth Amendment," icL at

391 (majority opinion), that demand that

racial minorities be afforded the same

right to vote, and the same level of

political representation, as all other

citizens. See G. GUNTHER, CASES AND

MATERIALS ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 691-707

(9th Ed. 1975). Whatever other goals the

Equal Protection Clause is designed to

achieve, at the very least it demands "the

prevention of meaningful and unjustified

official distinctions based on race," and

particularly those distinctions disadvan

taging racial minorities in the political

process. Hunter v. Erickson, supra, 393

U.S at 391.

71

c. Nyquist v. Lee

In Nyqu i s t v ,. Lee , 40 1 U.S. 935

), aff'g 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y.

1970), the Court reaffirmed these prin

ciples in a context involving the uneven,

subject-matter-specific realignment of

political power — not, as in Hunter,

between local municipal officials and the

electorate, but between state and local

public-school officials.

In New York (unlike in most American

states, see Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717, 742 & n. 20 ( 1974)), authority over

the public schools largely belongs to

state, rather than local, education

officials. Thus, the Board of Regents of

the University of the State of New York,

and its chief executive officer, the

Commissioner of Education, have long had

"the authority to order local school

boards to act in accordance with state

28

educational policies formulated by the

Board of Regents." Lee v. Nyquist, 318

F.Supp. at 719. As in Hunter, with regard

to housing in Akron, the racial minorities

before the Court in Lee had succeeded in

the past in convincing these officials to

adopt "a policy of eradicating dhe facto

segregation" in the public schools of New

7/York. Ld. at 716. Despite "considerable

local resistance," the Regents and Commis

sioner of Education enforced this policy

by ordering local school boards to re

assign students to assure racial balance

in the schools. Id.

!_ / "[SJchool authorities have wide discretion in formulating school policy, and

... as a matter of educational policy ... may well conclude that some kind of racial

balance in the schools is desirable quite

apart from any constitutional require

ments." North Carolina Board of Education

v. Swann, 402 U.S. 31, 45 (1971); accord,

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971).

29

The opponents of mandatory desegrega

tion in New York secured legislation res

cinding such orders. As in Hunter, how

ever, this goal was not accomplished by

simply reversing the same political pro

cess that minorities had previously used

to secure state-imposed anti-segregative

measures. Nor was it accomplished by

generally rearranging the political

process to make action by state education

officials, including action beneficial to

the victims of de facto segregation, more

difficult to achieve, for instance by

forcing state officials generally to share

authority with local ones.

Instead, as in Hunter, the opponents

of state-mandated desegregation adopted a

subject-matter-specific law providing that

any action regarding student assignment

"on account of race, creed, color or

30

national origin" would require, in addi

tion to the approval of state officials,

"the express approval of a [local] board

of education having jurisdiction, a

majority of the members of such board

8/having been elected Lee v.

8/ As in Hunter, the law struck down in

Lee on its face was racially neutral,

since race-conscious reassignment of

students to benefit whites was subjected

to the same special hurdles as reassign

ment to benefit blacks. However, as in Hunter, see note 5, supra, the Lee Court

recognized, given the statute's genesis in "local resistance" to past integrative

student-assignment plans, that the statute effectively embodied an "explicitly racial

classification" affording the educational

interests of the black victims of de_ facto

segregation less favorable treatment than

the educational interests of all other

citizens. Lee v. Nyguist, supra, 318

F. Supp. at 718. As in Hunter, the law

was accordingly held unconstitutional

irrespective of the motivation of its

proponents. Id.

In view of Lee, and the other cases

applying Hunter Tin school-segregation

contexts, e.g., Evans v. Buchanan, 393

F. Supp. 428, 440-41 (D .Del.)(3-judge

court), aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 ( 1 975)(citing

cases), the Government's suggestion that

Nyguist, supra, 318 F.Supp. at 712. While

giving local officials authority over this

8 / continued

the Fourteenth Amendment prohibition

enunciated in Hunter is limited to non

neutral laws d i s couraging efforts to

end de facto housing segregation, and does

not apply to nonneutral laws discouraging

efforts to end c[e facto school segrega

tion, is ludicrous. E.g ., Brief of the United States, at 17-18. See generally

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443

U.S. 449 , 465 n. 1 3 ( 1 979 )(citing cases)

(noting the hand-in-glove relationship

between housing and school segregation).

Indeed, the characteristic of efforts to end de facto school segregation on

which the Government relies to distinguish this case from Hunter — i.e ., that some

minorities may not be benefited by such

measures, Brief of the United States, at

17-18 — applies equally in the housing

context in Hunter. However, that not all

minorities support open housing or integrated schooling does not undermine the

conclusion in Hunter, Lee and below that

a legislative classification burdening

such supporters, but no other citizens, is

unconstitutional because those whom it

does disadvantage are minorities. Otherwise, for example, the Court's conclusion

in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, that a "white

Democratic primary" law unconstitutionally

disadvantages blacks would be undermined

by the fact that many blacks are Repub

licans, and have no desire to vote in the

Democratic primary. See notes 2, 3, supra.

32

one aspect of educational policy— --

of special interest to the racial minority

victims of <3e facto segregation — the law

left the authority of state officials in

tact as to all other educational matters,

including all other student-assignment

matters.

As in Hunter, the Court in Lee found

this law unconstitutional under the

Fourteenth Amendment because the specific

rearrangement of the political system

chosen to accomplish the present res

cission and future discouragement of

9 /

9/ The law struck down in Lee actually

realigned authority over student assignment to alleviate de facto segregation in

two ways. In school districts governed by

an elected school board, final authority

rested with that board. In districts governed by an appointed school board,

however, the law withdrew the authority to

assign students to alleviate segregation

from all (i.e. , state and local) education

officials, leaving it exclusively in the

hands of the state legislature. See Lee v.

Nyquist , supra, 318 F. Supp. at 719.

33

civil-riqhts-oriented benefits previously

conferred on minorities was not racially

neutral:

[The statute] singles out for different treatment all plans

which have as their purpose

the assignment of students in

order to alleviate racial im

balance. The Commissioner and

local appointed officials [see

note 9, supra] are prohibited from acting in these matters

only where racial criteria are

involved. The statute thus

creates a clearly racial classi

fication, treating educational

matters involving racial criteria

differently from other educa

tional matters and making it

more difficult to deal with

racial imbalance in the public

schools. We can conceive of no

more compelling case for the

application of the Hunter prin

ciple.

318 F. Supp. at 719 (Hays, J.), aff 'd, 401

U.S. 935 (1971).

Lee, like Hunter, lies at the "core"

of the Fourteenth Amendment's "protection

[of minorities] from the majoritarian

34

political process." San Antonio School

Dist. v. Rodriquez, supra, 411 U.S. at 28.

It too strikes down an effort by members

of the majority to structure the political

process so that the black victims of

segregation are once again relegated to

the historical position of "political

powerlessness" vis a vis all other citi

zens that the Equal Protection Clause was

particularly designed to remedy. Id.

D. Initiative 350

Initiative 350 is a mirror image of

the law found unconstitutional in Nyguist

v. Lee. Like that law, Initiative 350 was

legislated in direct response to a plan

(in this case "The Seattle Plan") of

"mandatory" student reassignment to

achieve greater interracial contact in the

J_0 /schools, only here the nonneutral

10/ "Mandatory" is a misnomer. For the

citizens of Seattle, through their elected

35

realignment of power runs from the local

to the State level, rather than from the

1 1/State to the local level, as in Lee.

In the State of Washington, as in

most American jurisdictions (excepting

New York), see Milliken v. Bradley, supra,

418 U.S. at 742 & n. 20, the authority to

1 0/ continued

representatives on the school board of

that district, voluntarily chose to re

assign students in order to achieve a

greater degree of racial balance. The

mandate, that is, came not from a federal

court or other agency not directly res

ponsible to the citizens of Seattle, but

from those citizens themselves. The term

is accurate only in the sense that, as in

virtually every public school system in

the country, the student assignment plan

in Seattle requires that students living

in specified areas attend specified

schools, rather than allowing each student

voluntarily to choose the school he or

she attends.

11/ The law in Lee realigned the politi

cal process in some districts in New York

by removing authority from education offi

cials generally and giving it to the State

legislature. See note 9, supra. To this

extent, Initiative 350 is an exact, rather

than mirror, image of the law struck down

in Lee.

36

operate the public schools and, specific

ally, to assign students to particular

facilities, resides almost exclusively

in local school boards. "The law [of

Washington] has plainly vested the board

of directors of school districts such as

this with discretionary powers in such

matters." State ex rel. Lukens v. Spokane

School District 81 , 147 Wash. 467,

474, 266 P. 189, 191 (1928). See Seattle

School Dist. No. 1 v, Washington, 473 F.

Supp. 996, 1010 (W.D. Wash. 1979) (Finding

of Fact 8.2). As the Supreme Court of

Washington has expressly held, the Seattle

school board was free to adopt a mandatory

integration program such as The Seattle

Plan in the proper exercise of its broad

discretionary power over student assign

ment. See Citizens Against Mandatory

Bussing v. Palmason, 495 P.2d 657, 6 6 6

37

12/(Wash. 1972).—

Although the Seattle Plan encountered

opposition, its opponents did not seek

to rescind the Plan through the pre-exist

ing political process. Instead, they found

it easier to rearrange that process through

13/adoption of Initiative 350. 4 7 3 p. supp.

at 1006-07 (Findings of Fact 6.3, 7.1-7.5).

12/ In Palmason, the Supreme Court of

Washington held, prior to the enactment of

Initiative 350, that local school boards

in Washington have almost plenary "discre

tionary power" over student assignments

within their districts, subject only to

judicial review to determine if such assignments "violate some fundamental right

of the party challenging them." 495 P.2d

at 660 & nn.3, 4. The Court concluded that a predecessor of "The Seattle Plan"

violated no such right. 1̂ 3. at 662-63.

13/ Previous attempts by opponents of

desegregation to recall the pro-integration

members of the Seattle school board

had failed. 473 F. Supp. at 1006 (Finding

of Fact 6.3), aff'd, 633 F.2d 1338, 1346

(9th Cir. 1980).

38

As in Hunter and Lee, however, the Wash

ington voters who adopted the Initiative

did not generally restructure the poli

tical process so that a 1JL comparable

governmental action would be harder to

secure in the future. Rather, using a

subject-matter classification like those

struck down in Hunter and Lee, Initiative

350 rescinded The Seattle Plan and preven

ted its duplication in the future by non-

neutrally realigning the political struc

ture of public education in Washington

along lines corresponding to the race of

the persons adversely affected. Under the

Initiative, the minority victims of de

facto school segregation could only secure

governmental action relieving that condi

tion from the State legislature or the

State electorate at large, although all

other citizens remained free to achieve

any other goal of public education or

student assignment through local school

boards.

The racial classification drawn by

Initiative 350 is clear from the face of

that provision. Under the Initiative, the

citizens of Washington remain free, as

before it was adopted, to secure from

local school boards: (i) any governmental

action affecting public education other

than student assignment (Initiative 350,

§ 1 ), and any student-assignment action

designed to (ii) utilize "the school

nearest or next nearest to student's place

of residence" (id. ), or, regardless of the

location of the school facility, to (iii)

improve "the course of study" available to

students (id.), (iv) provide "special

education, care or guidance," including

for "students who are physically, mentally

40

or emotionally handicapped" (id. §§ 1 (1 ),

(4)), (v) alleviate transportation diffi

culties, caused by "health or safety

hazards, either natural or man-made, or

physical barriers or obstacles, either

natural or man-made" (id. § 1 (2 )), (vi)

avoid attendance at facilities that are

"unfit or inadequate because of over

crowding, unsafe conditions or lack of

physical facilities" (_id. § 1 (3 )), or

(vii) satisfy "most, if not all, of the

major reasons for which students are at

present assigned to schools other than the

nearest or next nearest schools" except

for desegregation (453 F. Supp. at 1 0 1 0 ,

Finding 1 1 /of Fact 8-3). As its propo-

nents promised the voters of Washington,

14/ Initiative 350 is not a neighborhood-

school law. It leaves intact the local

school board's broad discretion to define

the curriculur, remedial, health, safety,

transportation and space needs of its

41

Initiative 350 occasions "no loss of

[local] school district flexibility other

than in busing for desegregation pur

poses" (473 F. Supp. at 1008, Finding of

Fact 7.18), and in no way affects the "99%

of the school districts" in Washington

(i.e. , all but the three respondent dis

tricts) that are not now assigning or

contemplating the assignment of students

14/ continued

students, and to assign those students to

schools other than those nearest or next

nearest their place of residence, if it

concludes that any of those needs will be

better served by such assignments. Accordingly, even were a neighborhood-school

policy compelling enough to justify what

otherwise amounts to a constitutional

violation — but see Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S 1,

28 (1971) -- Initiative 350 is designed to achieve no such policy, since as both

courts below expressly found, it freely allows local school boards to ignore that

goal whenever any educational interest

other than racial integration is involved.

453 F. Supp. at 1010 (Finding of Fact

8.3), aff'd, 633 F.3d at 1344 & n.4.

42

to encourage interracial contact (id̂ . at

1008-09, Finding of Fact 7.9).

Accordingly, the single class sub

jected by Initiative 350 to the extra

ordinary political burden of having to

obtain statewide legislative or popular

approval of local student-assignment pro

posals suiting its particular needs is

composed exclusively of "the black stu

dents" in the State of Washington who

are victimized by segregation in the

public schools. Id. at 1007 (Finding of

15/Fact 6.12), aff *d, 633 F.2d at 1342-44.—

Since, as in Hunter and Lee the disadvan-

15/ The Courts below both found that

black citizens living in segregatd neigh

borhoods in Washington believe that racial

integration of the schools would benefit

their children. Regardless of whether

those citizens are right or wrong (see

Section II, infra), the State of Washing

ton may not constitutionally subject them

to political hurdles, not applicable to other citizens, that impede their

achievement of that goal. In short, the

43

taged class is defined by the race of its

members, the law offends the Equal Protec

tion Clause regardless of the motivation

16/of its proponents.

15/ continued

social validity of' racial integration is

not at issue here. What is at issue is

the right of black citizens to pursue that

legitimate governmental objective through

lawful political processes on the same

basis as all other citizens are permitted

to pursue their legitimate governmental

ends.

16/ Much is made by appellants of the

fact that the provisions in Hunter and

Lee defined the forbidden subject-matter

classification in terms of the subject-

matter on which a special political burden

was placed by the State (i.e., fair

housing regulation in Hunter and student

reassignment to achieve integration in

Lee) , and accordingly used the word

¥race," while the drafters of Initiative

350 defined the subject-matter classifi

cation in terms of all of the subject

matters on which the special political

burden was not placed (i.e. , every use

of student reassignment save for inte

gration), and thereby avoided using the

word "race." However, it was not the

wording of the laws in Hunter and Lee, or

even any facial nonneutrality in that

wording, that rendered those laws un-

44

To put it bluntly, members of the

political majority in Washington have

passed a law requiring racial minorities

to seek statewide approval of govermental

action on their behalf, while insisting

that action on every one else's behalf

need only secure the approval of local

officials. As a result, the internal

16/ continued

constitutional. As the Hunter Court not

ed, those laws on their faces "treat[ed]

Negro and white, Jew and gentile in an

identical matter." Hunter v. Erickson,

supra, 393 U.S. at 391. The Court struck

down the laws in Hunter and Lee because it

was clear, once the "covert" statutory classifications they created were exposed

(see Personnel Administration v. Feenev, 442 U.H. 256, 274 (1979)), that they

separated persons for differential treatment along lines that corresponded exactly

(rather than only approximately, as in,

e«g»f Feeney, supra; Village of Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Authority,

429 U.S. 252 ( 1977); Washington v. Davis

426 U.S. 229 (1976); and James v. Val-

tierra, 402 U.S. 137 ( 1971 )) to the race

of the persons adversely affected. It is

in this sense that the offensive classifi

cations were "explicitly racial," and thus

45

political processes governing public

education in Washington are not organized

"on the basis of any general principle,"

Hunter v. Erickson, supra, 393 U.S. at 395

(Harlan, J., concurring), and do not

"treat[] all individuals as equals" re

gardless of race, Mobile v. Bolden, supra,

16/ continued

unconstitutional, regardless of the motive

for drawing them. Hunter v. Erickson,

supra, 393 U.S at 389? see notes 5, 8 ,

supra.

The classification drawn by Initiative

350' is nonneutral and explicitly racial in precisely the same way as the classifi

cations struck down in Hunter and Lee. Indeed, as the district court1s factfind

ings make clear, the classification drawn

by Initiative 350 — between minorities

favoring mandatory student assignment to

relieve them of racial isolation and all

other persons seeking beneficial governmental action relating to education or

student assignment — is identical to the explicitly racial classification struck

down in Lee. See 473 F. Supp. at 1008-09 (Findings of Fact 7.8, 7.9, 7.18, 7.19).

Put simply, it was the substance of

the laws struck down in Hunter and Lee,

46

446 U.S. at 84 (Stevens, J. , concurring).

Rather, they deny the black victims of

school segregation the same degree of

political protection afforded all other

citizens by the laws of the State. This,

>

in its rawest form, is the denial of "the

equal protection of the laws." It is

unconstitutional under the Fourteenth

Amendment.

16/ continued

and it is the identical substance of

Initiative 350 — the correspondence of

the classification drawn to the race of

the persons adversely affected — rather

than the form or specific wording of those

provisions that (barring some compelling

justification) render all three unconsti

tutional irrespective of the motivation of

their drafters.

47

II

RACIAL INTEGRATION OF PUBLIC EDUCA

TION, WHICH INITIATIVE 3 50 NON-

NEUTRALLY FRUSTRATES, IS A LEGITIMATE,

INDEED PRESSING, POLITICAL OBJECTIVE

OF BLACK CITIZENS IN APPELLEE SCHOOL

DISTRICTS._________________________

While white students often benefit

from interracial association, e^g.,

Regents of the University of California

v JL_B a k k e , 438 U.S. 265, 314-15 (1978)

(Powell, J.), the courts below found that

the persons in fact disadvantaged by

Initiative 350 were the black and other

minority students living in segregated

neighborhoods in appellee districts who,

but for the enactment of the Initiative,

would be assigned to racially integrated

public schools. See 633 F.2d at 1343-44.

The parents of these minority students

believe that racially integrated public

education in their school districts would

benefit their children and, prior to

48

Initiative 350's enactment, convinced

appellee disricts to pursue that objec

tive in an effective manner. Regardless

of whether these parents are right or

wrong in their belief, the State of Wash

ington may not constitutionally subject

them, but no other citizens, to political

hurdles that impede their achievement of

legitimate governmental action consistent

with those beliefs. See Part I, supra.

Moreover, there can be no question

that it is a legitimate governmental ob

jective for a local school district volun

tarily to seek to desegregate its schools

through "exercise of its discretionary

power to assign students within [its]

school systemf]." McDaniel v. Barresi, 402

U.S. 39, 42 ( 1971 ). See note 7, supra.

It is equally well established that "bus

transportation [is] a normal and accepted

tool of educational policy," Swann v.

49

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 29 (1971), which "has long

been an integral part of all public educa

tional systems," and that "it is unlikely

that a truly effective [desegregation]

remedy could be devised without continued

reliance upon it." North Carolina Board of

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 46

17/(1971).—

17/ In the last decade, the debate over

school desegregation has often degenerated

into a debate over "forced busing." The

term "forced busing" is a misnomer.

School districts do not force children to

ride a bus, but only to arrive on time at

their assigned schools. When that school

is beyond walking distance — for whatever reason — parents not only do not object

to busing, they insist on it, and have for many years. Thus, busing children to

school doubled during the 1930s, grew by

70 percent in the 1940s, and increased by

more than a third between 1960 and 1970. METROPOLITAN APPLIED RESEARCH CENTER,

BUSING TASK FORCE FACT BOOK 22-24 (1972); HEW, National Center for Educational Sta

tistics, Table, in G. ORFIELD, MUST WE

BUS? 130 (1978). By 1969, prior to the

advent of court-ordered mandatory racial

balance plans in the wake of Alexander v.

Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

50

Although apparently conceding its

legitimacy as a governmental objective,

17/ continued

19 (1969), almost 60 percent of all school- age children were transported to school.

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, TRANSPORTA

TION CHARACTERISTICS OF SCHOOL CHILDREN 7,

10-15 (1972). Even today, over 97 percent

of public-school busing is for purposes

other than desegregation. The New York

Times, Dec. 4, 1980, §1, at 25, Col. 1.

The parental demand for busing stems from the fact that riding a bus to school

is substantially safer than walking. A

study by the Pennsylvania Department of

Education found that children who walk to

school are in three times as much danger

as those who ride the bus, while the Na

tional Safety Council reports that boys

are three times, and girls two times, as

likely to have an accident walking to

school than if they ride in a bus. See

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS, PUBLIC

KNOWLEDGE AND BUSING OPPOSITION 17 (1973).

Other statistics establish that riding the

bus is safer than riding in a car. Buses:

Backbone of Urban Transit, The American

City, Dec. 1974, at 23; NATIONAL ASSOCIA

TION OF MOTOR BUS OWNERS, BUS FACTS 17

(39th ed. 1972). It is also safer to

ride a bus to p^ b_l ̂ c school than to

private school, primarily because private

and parochial schools rely heavily on

worn-out buses purchased from public

school systems after years of use. School

Bus Task Force, in 120 CONG. REC. 8757

(1974). Cf. G. ORFIELD, supra, at 129

51

the Government nevertheless questions the

efficacy of school desegregation for black

students, purportedly on the basis of

social science data. Brief for the United

17/ continued

(when a parent removes his child from a

desegregated school and places the child

in a private school, the length of the

child's bus ride increases, on average,

by 70 percent).

As is attested by the huge increase

in busing over the last 50 years, busing

per se does not have any negative educa

tional effects. Nor is there any evidence that attending a school other than the one

nearest the student's home negatively af

fects academic achievement or a school's

social climate. Davis, Busing, in 2 R.

CRAIN, et al., SOUTHERN SCHOOLS: AN EVALU

ATION OF THE EMERGENCY SCHOOL ASSISTANCE

PROGRAM AND OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION 118

(1973); Zoloth, The Impact of Busing on

Student Achievement, 7 GROWTH & CHANGE 45

(July 1976).

In short, notwithstanding the focus

of the opponents of mandatory desegrega

tion on "forced busing," the social scien

tific literature unequivocally establishes

that publically provided transportation to to schools is a safe, indeed necessary,

component not only of desegregation efforts but, much more pervasively, of

public education in general.

52

States, at pp. 38-39, n. 39. However, a

recent comprehensive review of the social

science literature on public school dese

gregation establishes that the educational

opportunities and achievement of black and

other minority students are substantially

enhanced by the use of student assignment

to achieve racial integragion. Hawley,

"The False Premises of Anti-Busing Legis

lation," testimony before the Subcom. on

Separation of Powers, Sen. Com. on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (Sep

tember 30, 1981) (summarizing findings)

(hereinafter "Hawley testimony")? W.

HAWLEY, et al., 1 ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT

KNOWLEDGE ABOUT THE EFFECTIVENESS OF

J_8/ - For the reasons set out in note 15,

supra, this query by the Government is Irrelevant here. Nonetheless, the sug

gestion that desegregation is not effec

tive is so thoroughly inaccurate that

amicus is compelled to respond.

53

SCHOOL DESEGRATION STRATEGIES, STRATEGIES

FOR EFFECTIVE DESEGREGATION: A SYNTHESIS

OF FINDINGS 17-50 (1981) (hereinafter

"Synthesis"); C. ROSSELL, et al., 5 AS

SESSMENT OF CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ABOUT THE

EFFECTIVENESS OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

STRATEGIES, A REVIEW OF THE EMPIRICAL

RESEARCH ON DESEGREGATION: COMMUNITY RES

PONSE, RACE RELATIONS, ACADEMIC ACHIEVE

MENT AND RESEGREGATION (1981) (hereinafter

"Review of Empirical Research"). For the

convenience of the Court, copies of these

materials, which synthesize the massive

body of social science research concerning

school districts undergoing actual sus

tained desegregation over the last 15

years, have been lodged with the Clerk's

office.

Briefly stated, the social science

review has found, inter alia, that:

54

1. The use of student assignment as

a desegregation method has reduced racial

isolation in every school system studied

19/notwithstanding any "white flight."

2. Desegregation as a general rule

cannot be accomplished effectively without

using student assignment. "Voluntary"

plans, which rely exclusively on student

choice as to whether to be reassigned to

a desegregated school or a "magnet" school

program, have proven to be almost totally

ineffective in reducing racial isola-

20/tion.

3. Attending racially integrated

19/ Hawley testimony, at 2-9? Synthesis,

at 17-34; Rossell, "The Effectiveness of Desegregation Plans in Reducing Racial

Isolation, White Flight, and Achieving a Positive Community Response" in Review of

Empirical Research, at 1-87.

20/ Id. Compare, e.g. , Columbus Board of Education v. Penick~ ̂ 443 U.S. 449, 459-60

(1979) (desegregation plans that do not

involve student assignment have proven

ineffective).

55

schools substantially — often dramatic

ally — enhances the academic achievement

of black students as revealed by commonly

used achievement and I.Q. measures. Gains

are greatest when integration starts in

the earliest grades. The achievement

levels of white students in integregated

schools do not suffer, while race rela-

2 1/tions among all students improve.—

As this research demonstrates, the

goal of effective public-school integra

tion is not only a proper governmental

objective, but one that the blacks in

appellee districts who desire it, and who

are unconstitutionally burdened by Initia

tive 350 in achieving it, correctly

perceive as crucial to their future

well-being.

21/ Hawley testimony, at 10-13? Crain &

Mahard, "Some Policy Implications of the

Desegregation-Minority Achievement Literature" in Review of Empirical Research, at

172-208

56

CONCLUSION

The judgement of the Ninth Circuit

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BILL LANN LEE *

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational

Fund as Amicus Curiae