Collins v. Hardyman Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Collins v. Hardyman Brief Amicus Curiae, 1950. 62ee2af3-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/60a0c1cb-d833-40d7-95e1-bc87147b2cc5/collins-v-hardyman-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

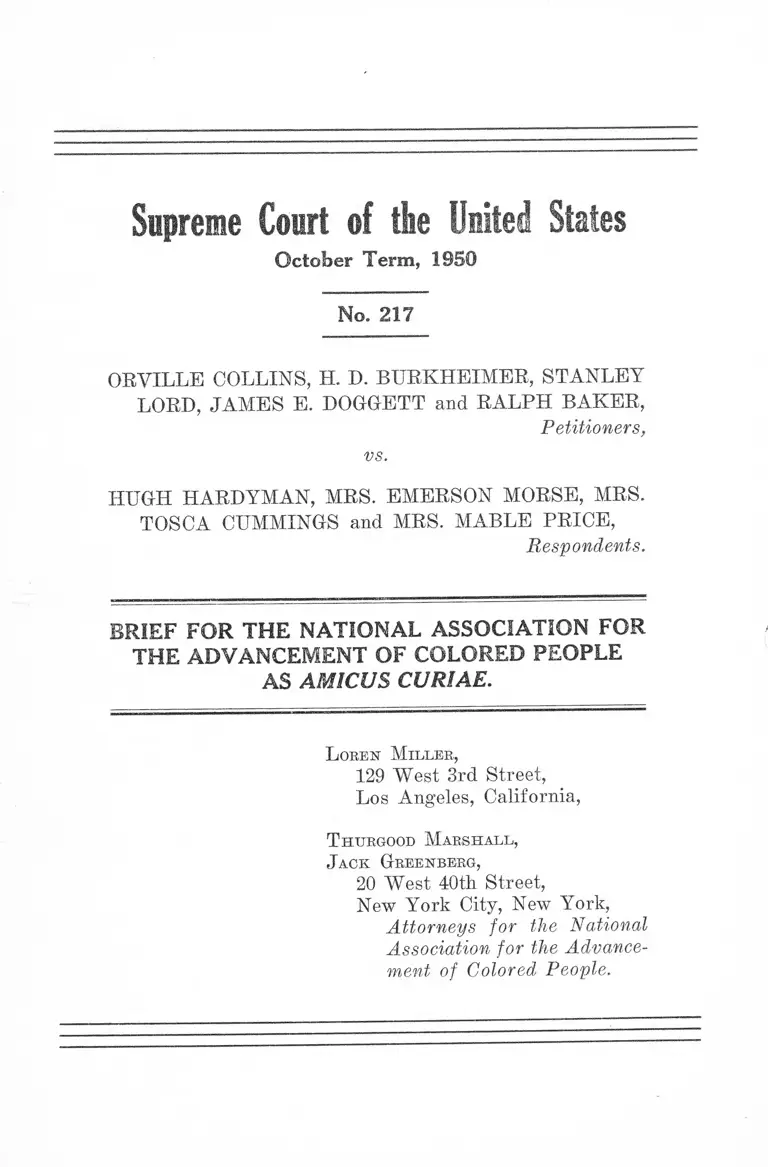

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1950

No. 217

ORVILLE COLLINS, H. D. BURKHEIMER, STANLEY

LORD, JAMES E. DOGGETT and RALPH BAKER,

Petitioners,

vs.

HUGH HARDYMAN, MRS. EMERSON MORSE, MRS.

TOSCA CUMMINGS and MRS. MABLE PRICE,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE.

L oren Miller,

129 West 3rd Street,

Los Angeles, California,

T htjbgood Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

20 West 40th Street,

New York City, New York,

Attorneys for the National

Association for the Advance

ment of Colored, People.

I N D E X

PAGE

Interest of tlie National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People__________________________ 1

I—Section 47(3) covers the action of private persons

who infringe certain constitutionally granted

rights _______________________________________ 2

A. General Congressional Definition--------------- 3

B. No Contrary Specific Definition ----------------- 4

C. No Internal Evidence That Word Is Being

Used in Unusual Sense------------------------- 4

D. The Customary Congressional Usage --------- 5

E. Legislative History ---------------------------------- 7

F. If Ambiguity Exists, Public Policy Dictates

Respondents’ Construction of “ Person” 7

Conclusion ________________________________________ 11

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 ------------------------- 9

Kovacs v. Cooper, 93 L. Ed. 379 ------------------------------- 9

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516------------------------------- 9

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 ---------------------------- 9

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S. 144 — 9

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 ___________________________________ 9

Miscellaneous

PAGE

Clark, A Federal Prosecutor Looks at the Civil Rights

Statutes, 47 Col. L. R. 175 (1947) _______________ 11

Crawford, The Construction of Statutes, 1940 -------- - , 8

Dowling, Constitutional Law, 1947 -------------------------- 9

Frankfurter, Some Reflections on the Reading of Stat

utes, 47 Col. L. R. 527 (1947) ________ ___________ 3

Lerner, The Mind and Faith of Justice Holmes (1943) 9

Sutherland, Statutory Constitution (1943) --------------- 8

Statutes

13 Stat. 258 ________________________________________ 3

14 Stat. 163 ________________________________________ 3

15 Stat. 166 ------------------------- 3

16 Stat. 431 ________________________________________ 4

1 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 1 ------------------- 5

2 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 261(c) ----------- 6

4 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 110 --------------- 6

5 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 1001(b) --------- 6

6 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 15 ----------------- 6

6 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 618 ---------------- 6

7 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 242, 504,

608a(9) _____ -__________________________________ 6

United States Code Annotated, Title 8, Sec. 47(3) ------2,3,

4, 5,7

15 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 80a-2, 80b-2,

431, 715a, 717a, 901, 1127 _______________________ 6

16 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 631a, 690h, 721,

796, 851_________________________________________

11

6

Ill

PAGE

21 United States Code Annotated, Sees. 171,188a, 321_ 6

22 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 611 _________ 6

26 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 145, 894, 1426,

1532(i), 1607(k), 1718, 1805, 1821, 3124, 3507,

3710(c), 3793(b), 3797 ___________________________ 6

29 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 152, 203 _____ 6

33 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 466a-------------- 6

35 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 42c---------------- 6

41 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 52, 103 --------- 6

42 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 1818-------------- 7

46 United States Code Annotated, Sec. 316---------------- 7

49 United States Code Annotated, Secs. 1(3), 401, 902 7

50 App. United States Code Annotated, 38, 985, 1161,

1502, 1892 ______________________________________ 7

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1950

No. 217

Orville Collins, H. D. B txrkheimer, Stan

ley L ord, J ames E. D oggett and R alph

B aker,

Petitioners,

vs.

H ugh H ardyman, Mrs. E merson Morse,

Mrs. T osca Cummings and Mrs. Mable

P rice,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People submits this brief as amicus curiae. The

written consent of all parties to the case to the filing of this

brief has been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

Statement of Interest.

For more than forty (40) years, the National Associ

ation for the Advancement of Colored People has worked

unceasingly to foster those political, social and economic

conditions in which no individual’s opportunity can be

limited by race, religion, national origin or ancestry.

To this end, the N. A. A. C. P. has enlisted every legiti

mate measure—including all legal, political and educational

means that can be employed. In a struggle against preju

dice, it has recognized that only in a free political and

public forum can orderly change be effected in society.

Therefore, it has fought for freedom of expression for

individuals and groups, in and out of the political process.

It has fought for this freedom even for those with whom it

disagrees, for it realizes that free communication is indis

pensable to responsive, responsible government, and ante

cedent to any change. Free expression, it believes, is

choked off as effectively by mob intolerance and violence

as by state action.

The N. A. A. 0. P. believes that there is a sphere of

essential freedom, which the federal government can and

must protect, on which the survival of free society hinges,

and that certainly to assemble and petition for grievances

is within that sphere. It further believes that the Congress

so intended, and that that fact is demonstrated in respon

dents’ brief and the opinion of the Court below. However,

as a friend of the Court, it would like to perhaps emphasize

some matters already alluded to therein and to briefly

discuss some points of law which it submits should lead to

affirmance of the judgment below.

The opinion below is reported at 183 F. 2d 308.

I.

Section 47(3) covers the action of private persons

who infringe certain constitutionally granted rights.

Petitioners and the dissenting opinion below deny that

Section 47(3) applies to private persons. They contend

that the word “ persons” in the statute does not mean

“ persons” as that word is customarily understood, but

.2

that it is narrowly limited in meaning to “ governmental

agencies or officials” .

In construing a statute, we “ assume that Congress uses

common words in their popular meaning, as used in the

common speech of men * * * ” (F rankfurter, “ Some Re

flections on the Reading of Statutes” , 47 Col. L. R. 527, 536

(1947)). However, when ambiguities occur, we employ

various devices to determine the meaning of the legislature,

or if that task proves impossible, under the fiction of de

termining legislative meaning, we assign a meaning most

appropriate under all the circumstances.

For purposes of this case, it seems that no one could

question the meaning of “ persons” , as any ambiguities

which the word conjures are in a realm not here relevant—

i. e., whether the definition includes certain juristic and

artificial entities. Nevertheless, we propose to subject the

term “ person” to any conceivable analysis to demonstrate

that in this case it has no peculiar meaning:

A. General Congressional Definition.

In 1871, the identical year in which what is now Section

47(3) was passed, Congress also passed a definition statute,

defining, among other things, the word “ person” . That

this was a well considered statute is demonstrated by its

gradual formulation during the preceding seven ,(7) years.

In 1864, a manufacturing statute (13 Stat. 258) defined

“ individual” and “ person” by including within the terms

such entities as “ partnerships, firms, associations # * *

corporations” . In 1866, a tax law (14 Stat. 163) made a

similar definition, adding “ bodies corporate or politic” .

In 1868, another tax statute (15 Stat. 166) made a sim

ilar definition. 1871 marked the appearance of the first

general definition of “ person” . It is to be noted once more

3

4

that this definition was passed shortly before the passage

of the section we now construe. It stated:

( ( # # #

“ Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, that in all acts

hereafter passed * * * the word ‘ person’ may extend

and be applied to bodies politic and corporate, and

the reference to any officer shall include any person

authorized by law to perform the duties of such

office, unless the context shows that such words were

intended to be used in a more limited sense # # * ’ ’

(16 Stat. 431).

It is also to be noted that Congress did not conceive

“ officers” and “ persons” to be identical, but saw fit to

define each separately.

B. No Contrary Specific Definition.

Sometimes, Congress, within a statute, defines the mean

ing of words used therein. No such definition appears in

47(3). Surely, if another meaning were intended, in view

of the common definition of “ person” , the general definition

statute quoted above, internal contradictions which result

from petitioners’ definition (see the opinion of the Court

below, p. 311), and the Congressional practice of providing

definitions for particular statutes—surely, a specific defi

nition for purposes of this section would have been pro

vided.

C. No Internal Evidence That Word Is Being Used in

Unusual Sense.

All indications from the statute are that “ person”

means “ person” as that word is commonly understood.

The same considerations applicable in the discussion of

Point “ B ” above are relevant here. The internal evidence

upon which petitioners rely is that the word “ equal” some

5

how indicates that only the state is capable of causing cul

pable deprivation. By definition, privileges or immunities

bestowed by the national government must be equally dis

tributed. They cannot be enjoyed by some, and not by

others. Therefore, any deprivation of a privilege or im

munity must be the deprivation of an “ equal” privilege

or immunity. The word “ equal” here merely emphasizes

the solemn importance of the activities which are protected.

An individual who suppresses one of these essential free

doms assails an “ equal” privilege and immunity to the

same extent as does a state officer. Because government

bestows equality does not mean that only government can

take it away.

Petitioners and the dissenting opinion below attempt to

back into an unusual definition of “ person” by reliance

upon a jurisprudential theory of who may grant rights and

who may deprive them and their exercise. Granting,

arguendo, the correctness of the concepts relied upon, at

most, we find ourselves with a statute which presents cer

tain internal contradictions. The meaning of the statute

then must be resolved in terms of the various probabilities

presented heretofore, and below, and in the light of con

siderations of public policy, as discussed more fully below.

D. The Customary Congressional Usage.

We have examined the customary use to which Con

gress put the word “ person” before and at the time of the

passage of 47(3). Since then Congress has defined “ per

son” scores of times never suggesting that “ person” means

government official and only government official. At the

very outset of the United States Code Annotated, Section 1

states:

“ In determining the meaning of any Act of Con

gress, unless the context indicates otherwise * * *

6

“ The words ‘ person’ and ‘whoever’ include cor

porations, companies, associations, firms, partner

ships, societies and joint stock companies, as well

as individuals. * * * ‘ officer’ includes any person

authorized by law to perform the duties of the

office. * * * ’ ’ 62 Stat. 859.

Again note the recognized non-identity of “ person”

and “ officer” .

Throughout the Code definitions are similar. 2 U. S.

C. A. Section 261(c) states:

“ The term ‘ person’ includes an individual, part

nership, committee, association, corporation, and any

other organization or group of persons.” 60 Stat.

839.

5 U. S. C. A. 1001(b) states

“ ‘Person’ includes individuals, partnerships,

corporations, associations or public or private or

ganizations of any character other than agencies.

* * * ” 62 Stat. 99.

6 U. S. C. A. 15 provides

“ * * * The term ‘ person’ in this section means

an individual, a trust or estate, a partnership or a

corporation. # * * ” 61 Stat. 646.

The following sections are in accord: 4 U. S. C! A.

Section 110; 6 IT. S. C. A. Section 618; 7 U. S. C. A. 242,

504, 608a (9 ); 15 IT. S. C. A. Section 80a-2, 80b-2, 431, 715a,

717a, 901, 1127; 16 U. S. C. A. Section 631a, 690h, 721, 796,

851; 21 IT. S. C. A. Section 171, 188a, 321; 22 IT. S. C. A.

Section 611; 26 IT. S. C. A. Section 145, 894, 1426, 1532(i),

1607(k), 1718, 1805,1821, 3124, 3507, 3710(c), 3793(b), 3797;

29 IT. S. C. A. Section 152, 203; 33 IT. S. C. A. Section 466a;

35 U. S. C. A. Section 42c; 41 IT. S. C. A. Section 52, 103;

7

42 U. S. C. A. Section 1818; 46 U. S. C. A. Section 316;

49 U S. C. A. Section 1(3), 401, 902; 50 App. U. S. C. A.

Section 38, 985, 1161, 1502, 1892.

E. Legislative History.

To satisfy this test, although those submitted above

should more than suffice, one need only make reference to

the Legislative History of 47(3) set forth in the opinion

of the Court below at page 311.

F. If Ambiguity Exists, Public Policy Dictates Respon

dents’ Construction of “ Person” .

It is impossible to see how any interpretation, other

than respondents’, of the word ‘ ‘ person” is possible. How

ever, if doubt exists, it should be resolved in favor of a

meaning most consistent with public policy. For this propo

sition, the following excerpt from a leading treatise on

statutory interpretation adduces ample support:

Section 5901:

Public policy retains a place of great importance

in the process of statutory interpretation and the

tendency of the courts has always been to favor an

interpretation which is consistent with public policy.

In fact it may be safely asserted that the bases of

all the interpretative rules in regard to strict and

liberal interpretation are founded upon public policy

in one form or another. Although public policy, in

the abstract, is a vague and indefinite term incapable

of accurate and precise definition, it often serves as a

concise expression for a combination of factors which

exercise a tremendous influence in the formation in

terpretation, and application of legal principles. * # *

In its strict sense public policy reflects the trends

and commands of the federal and state constitutions,

statutes and judicial decisions. In its broad sense

public policy may be traced to the current public

8

sentiment towards public morals, public health, pub

lic welfare and the requirements of modern economic,

social and political conditions.

It will be observed that the principles of strict

and liberal statutory construction are founded upon

the same or cognate factors. Therefore, public policy

has no separate significance in statutory interpre

tation, but instead, the rules of strict and liberal

interpretation are expressions of public policy. How

ever, it is natural and very common for the courts to

regard policy as a separate aid to interpretation,

and for that reason, it is expedient to consider here

the counterparts of public policy and how they affect

statutory interpretations.

Section 5902:

Constitutional legislation which is highly respon

sive to current demands serves as an extremely

valuable source of public policy. Thus a statute is

generally given a meaning consistent with its pur

pose or spirit which it is commonly associated with,

and serves as an indicia of public policy. * * *

Section 5904:

In this country the most reliable source of public

policy is to be found in the federal and state consti

tutions. Since constitutions are the superior law of

the land and because one of their outstanding fea

tures is flexibility and capacity to meet changing

conditions, constitutional policy provides a valuable

aid in determining the legitimate boundaries of

statutory meaning. Thus public policy having its

inception in constitutions may accomplish either a

restricted or extended interpretation of the liberal

expression of a statute. 3 Sutherland, Statutory

Construction (1943).

To a similar effect see Crawford, The Construction of

Statutes 1940, page 374.

9

The public policy of the United States relating to free

dom of expression is clear. It is best set forth in those

opinions of the Supreme Court which state that the pre

sumption of constitutionality normally applicable to legis

lation does not apply when a civil liberty is threatened.

The presumption is an outgrowth of what has been called

Justice H olmes’ philosophy of “ judicial laissez faire” .

(Lerner, “ The Mind and Faith of Justice Holmes,” (1943),

127). That is, a choice among the infinite number of social

remedies should be left almost entirely to the legislature,

which responds to the electorate, not to the courts. The

presumption, therefore, means that there is a wide area

in which the authority of the legislature will be upheld,

even though the Court might disagree with legislative

conclusions.

However, a necessary adjunct to the theory of the

loosely fettered legislature is that it shall be subject to

political restraint. For this it is necessary to have an

electorate capable of exerting the corrective force. There

fore any impairment of the effectiveness of the electorate

is viewed more carefully by the Court. To this effect see:

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 IT. S. 144,

152 n. 4; Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 95; Thomas v.

Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 530; Bridges v. California, 314 U. S.

252, 262-263; West Virginia State Board of Education v.

Barnette, 319 IT. S. 624, 639. “ The underlying theory of the

court appears to be that if, by striking down interferences

in respect to matters of the mind, it can keep the market

place of ideas open and the polling booths accessible, it will

rely upon the ordinary political processes to prevent abuse

of power in the regulation of economic affairs.” (D owling,

Constitutional Law, 1946.)

Mr. Justice F rankfurter, concurring in Kovacs v.

Cooper, 93 L. Ed. 379, 387 (1943), discussed the line of

10

opinions which have asserted that freedom of speech de

serves at least a “ preferred” position under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments. Although he rejects as mislead

ing such terminology as “ preferred position” or “ presump

tively unconstitutional” , he apparently joins in this ra

tionale of the cases:

“ The philosophy of his opinions on that subject

arose from a deep awareness of the extent to which

sociological conclusions are conditioned by time and

circumstance. Because of this awareness Mr. Justice

Holmes seldom felt justified in opposing his own

opinion to economic views which the legislature em

bodied in law. But since he also realized that the

progress of civilization is to a considerable extent

the displacement of error which once held sway as

official truth by beliefs which in turn have yielded to

other beliefs, for him the right to search for truth

was of a different order than some transient eco

nomic dogma. And without freedom of expression,

thought becomes checked and atrophied. Therefore,

in considering what interests are so fundamental as

to be enshrined in the Due Process Clause, those

liberties of the individual which history has attested

as the indispensable conditions of an open as against

a closed society come to this Court with momentum

for respect lacking when appeal is made to liberties

which derive merely from shifting economic arrange

ments. Accordingly, Mr. Justice Holmes was far

more ready to find legislative invasion where free

inquiry was involved than in the debatable area of

economics.” Kovacs v. Cooper, supra.

Attorney General, now Mr. Justice Clark, stated the

same policy somewhat differently in a recent article:

“ Our democracy suffers a grievous, if not a fatal,

blow when the processes of law and order are broken

down by mob violence. The federal government must

not stand idly by when a few reckless men in a com

11

munity disclaim their obligation to society and, flout

ing the priceless heritage of equality of all men, un

dertake to substitute lynch law for due process of

law. (C lark, “ A Federal Prosecutor Looks at the

Civil Eights Statutes” , 47 Col. 175, 185 (1947).)

Therefore, although it is difficult to see how any serious

ambiguity could exist, any uncertainties should be resolved

in the direction of the preservation of free expression.

Conclusion.

The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals

should be upheld.

L oren M iller,

T httrgood Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

Attorneys for the National

Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People.

L aw yers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300