Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Appendix

Public Court Documents

October 9, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Appendix, 1967. 1524f982-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/60a2ab83-cce4-47ba-b9af-710903114072/newman-v-piggie-park-enterprises-appendix. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

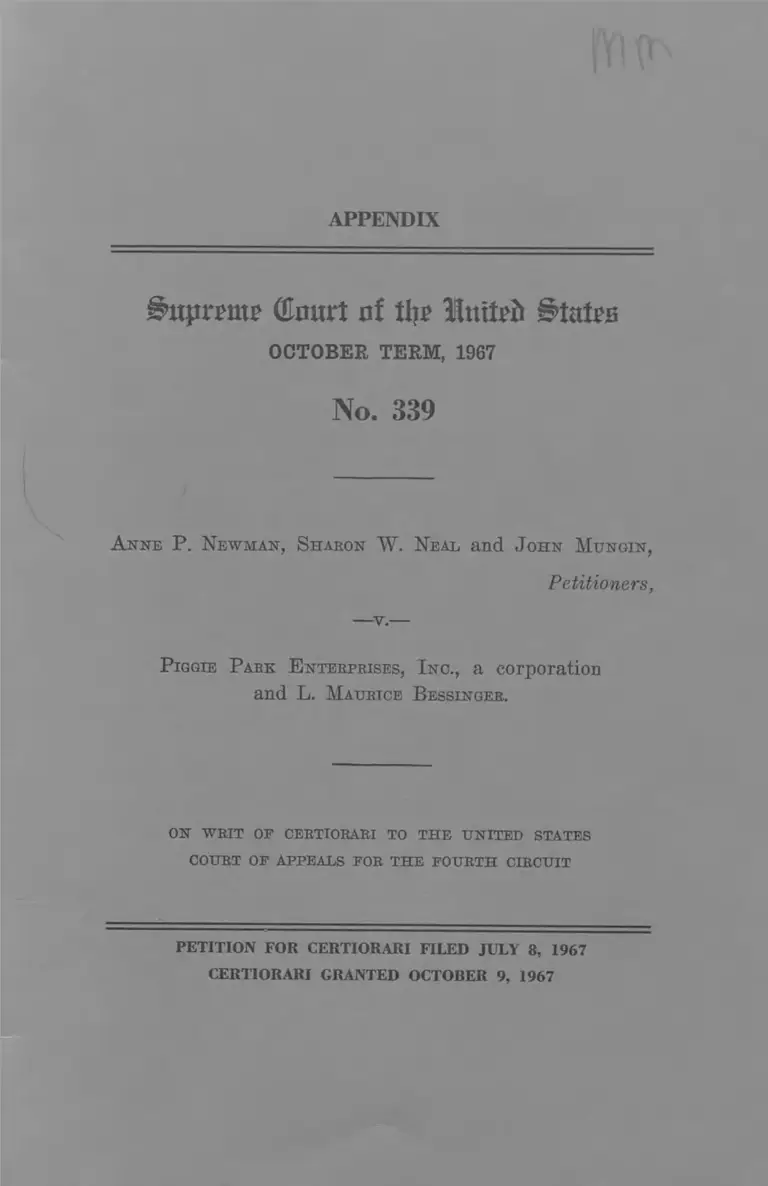

APPENDIX

(ftrnirt of tljp Hotted States

OCTOBER TERM, 1967

No. 339

A nne P. New m an , S haron W . N eal and J ohn M ungin ,

Petitioners,

P iggie Park E nterprises, I nc ., a corporation

and L. M aurice B essinger.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E FOURTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED JULY 8, 1967

CERTIORARI GRANTED OCTOBER 9, 1967

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Docket Entries ............................................................... la

Complaint ....................................................................... 2a

Answer ............................................................................. 9a

First Amended Answer.................................................. 12a

Motion to A m end........................................................... 15a

Affidavit in Support of Motion to Amend ............... 17a

Second Amended Answer.............................................. 18a

Trial Transcript............................................................. 22a

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses

Sharon Neal ........................................................... 26a

Sharon Miles .......................................................... 36a

Defendants’ Witnesses

Merele Brigman ...................................................... 47a

Jemell Richardson .................................................. 97a

L. Maurice Bessinger ............................................ 103a

Opinion of the District C ourt...................................... 135a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals .............................. 159a

Docket Entries

Answer ......................................

First Amended Answer...........

Motion to A m end....................

Affidavit in Support of Motion

To Amend ............................

Second Amended Answ er......

Trial H eld .............................. .

Opinion and Judgment in

District Court .......................

Notice of A ppeal.......................

Opinion and Judgment in

Court of Appeals

Com plaint.................................... Filed: December 18, 1964

Filed: February 5, 1965

Filed: August 23, 1965

Filed: March 19, 1966

Filed: March 19, 1966

Filed: March 30, 1966

April 4, 5, 1966

Filed: July 27, 1966

Filed: August 9, 1966

Filed: April 24, 1967

2a

In t h e

H&mttb Gkmrt at Appeals

F or the E astern District of S outh Carolina

Columbia D ivision

Civil Action No. AC-1605

A nne P. New m an , S haron W. Neal

and John M ungin ,

Plaintiffs,

—vs.—

Piggie Park E nterprises, I nc., a Corporation

and L. M aurice B essinger,

Defendants.

Complaint

(Filed: December 18, 1964)

1.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28 U. S. C., Section 1343(3) and Section 1343(4).

This is a suit in equity authorized by and instituted pur

suant to Title 2 of the Act known as the “ Civil Rights Act of

1964”, ------Stat.--------, and Title 42 U. S. C., Section 1983.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked to secure protec

tion of civil rights and to redress deprivation of rights,

privileges, and immunities, secured by (a) the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, Sec

tion 1; (b) the Commerce Clause, Article 1, Section 8,

3a

Clause 3, of the Constitution of the United States; (c)

Title 2, of the Act known as the “ Civil Eights Act of 1964”,

------ Stat.------- , providing for injunctive relief against dis

crimination in places of public accommodations; and (d)

Title 42 U. S. C., Section 1981, providing for the equal

rights of citizens and all persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States.

Complaint

2.

Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and of

others similarly situated pursuant to Rule 23(a)(3) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. There are common ques

tions of law and fact affecting the rights of Negro persons

to use the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages

and accommodations of the Piggie Park Restaurants, owned

and operated by the defendants herein, without discrimina

tion or segregation on the ground of race or color. The

persons constituting the class are so numerous as to make

it impracticable to bring them all before this Court. A

common relief is sought. The interests of said class are

adequately represented by plaintiffs.

3.

This is a proceeding for a temporary and permanent

injunction restraining defendants from continuing or main

taining any policy, practice, custom and usage of withhold

ing, denying, attempting to withhold or deny, or depriving

or attempting to deprive, or of otherwise interfering with

the rights of plaintiffs and others similarly situated to

admission to and full use and enjoyment of the goods,

4a

services, facilities, privileges, advantages and accommo

dations of the Piggie Park Restaurants owned and operated

by the defendants herein without discrimination or segre

gation on the ground of race or color.

4.

Plaintiffs are Negro citizens of the United States and

of the State of South Carolina, residing in the City of

Columbia and are classified as Negroes under the laws of the

State of South Carolina.

Complaint

5.

Defendant Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. is a corporation

duly organized and chartered under the laws of the State

of South Carolina. Said defendant owns and/or operates

several restaurants in various communities in the State

of South Carolina, two or more of which are located in the

City of Columbia. Defendant L. Maurice Bessinger is the

President of said corporation and is general manager

of the various restaurants operated by the corporate de

fendant. In said restaurants, defendants serve and offer

to serve interstate travelers and defendants’ operations

affect travel, trade, traffic, commerce, transportation or

communication among, between and through the several

states, the District of Columbia or foreign countries, terri

tories and possessions. A substantial portion of the goods

which defendants serve in said restaurants move in com

merce.

5a

6.

Each of the above named plaintiffs has been denied

service at one or more of the restaurants operated by the

defendants.

A. On or about July 3, 1964, plaintiff John Mungin

entered one of the restaurants operated by defendants at

No. 1430 Main Street in the City of Columbia, South Caro

lina and attempted to purchase food. Plaintiff was not

served and was required to leave the premises solely be

cause of his race and color.

B. On or about August 12, 1964, plaintiffs Anne P.

Newman and Sharon W. Neal attempted to purchase food

at two of the drive-in restaurants operated by defendants

in or near Columbia, South Carolina. Plaintiffs were told

that they could purchase food at said restaurants but that

they could not consume the food on the premises.

Complaint

7.

Plaintiffs were denied and deprived service in restau

rants owned and operated by defendants herein because

of the defendants’ well established and maintained policy,

practice, custom and usage of discriminating against

Negroes and of denying them service in said restaurants

in violation of plaintiffs’ rights to the full and equal en

joyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, ad

vantages and accommodations of places of public accommo

dation without discrimination of segregation on the ground

of race or color as secured by (a) the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States; (b) the Com

merce Clause, Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3, of the Con

6a

stitution of the United States; (c) Title 2, of the Act known

as the “ Civil Rights Act of 1964”, ------ Stat.------- , providing

for injunctive relief against discrimination in places of

public accommodation; and (d) Title 42 U. S. C., Sec

tion 1981.

8.

Plaintiffs allege that the racially discriminatory practices

of the defendants are in continuance of a long established,

maintained and well publicized policy of the defendants in

the operation of said restaurants and of the avowed pur

pose of said defendants to continue said policy. The State

of South Carolina has no State law and the City of Colum

bia has no local law prohibiting the racially discriminatory

practices described above and establishing or authorizing

the State or Local authority to grant or seek the relief

prayed herein. Plaintiffs have no plain, adequate or com

plete remedy at law to redress these wrongs and this suit

for injunction is the only means of securing adequate relief.

Plaintiffs are now suffering and will continue to suffer

irreparable injury from defendants’ policy, practice, cus

tom and usage as set forth herein.

Complaint

9.

On account of the above mentioned unlawful acts of

the defendants and on account of the maintenance of said

policy, practice, custom and usage in violation of the con

stitution and laws of the United States as aforesaid, plain

tiffs have employed attorneys and have been forced to file

this action and have incurred expenses and have become

obligated to pay counsel fees on account of the filing of

this action.

7a

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that upon the

filing of this complaint, as may be proper and convenient

to the Court, the Court advance this cause on the docket

and order a speedy hearing of said action and upon said

hearing:

(a) That the Court issue a preliminary injunction, en

joining defendants, their agents, employees, successors and

all persons acting in concert with them and at their direc

tion from continuing or maintaining any policy, practice,

custom or usage of denying, abridging, withholding, con

ditioning, limiting or otherwise interfering with plaintiffs

and other persons similarly situated in the admission,

usage, and enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages and accommodations of the restau

rants owned and operated by defendants and any other

restaurants owned and operated by the defendants on the

ground of race or color as contrary to the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution, the Com

merce Clause, Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3, of the United

States Constitution, Title 2, ------ Stat. ------ of the Act

known as the “ Civil Eights Act of 1964” and Title 42

U. S. C., Section 1981.

(b) That the Court enter a permanent injunction, en

joining defendants, their agents, employees, successors

and all persons acting in concert with them and at their

direction from continuing or maintaining any policy, prac

tice, custom or usage of denying, abridging, withholding,

conditioning, limiting or otherwise interfering with plain

tiffs and other persons similarly situated in the admission,

use and enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privi

Complaint

8a

leges, advantages and accommodations of the Piggie Park

Restaurants and any other restaurants owned and operated

by the defendants on the ground of race or color as con

trary to the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution, the Commerce Clause, Article 1, Section 8,

Clause 3, of the United States Constitution, Title 2, ------

Stat. ------ of the Act known as the “ Civil Rights Act of

1964” and Title 42, U. S. C., Section 1981.

(c) Allow plaintiffs their costs herein including rea

sonable attorney fees for plaintiffs’ attorneys and for such

other and additional relief as may appear to the Court

to be equitable and just.

Complaint

9a

Answer

(Filed: February 5,1965)

1.

Defendant Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. is a Corporation

duly organized and chartered under the laws of the State

of South Carolina; and owns and/or operates and/or fran

chises several restaurants in various communities in the

said State. Said Defendant is not engaged in interstate

commerce and operates under an announced policy of not

catering to interstate travelers. Said Defendant has been

denied Federal trade mark protection on the ground that

it is not in interstate commerce, and is discharged from the

responsibility of paying Federal minimum wages on the

same ground.

2.

Defendant Bessinger believes as a matter of faith that

racial intermixing or any contribution thereto contravenes

the will of God. As applied to this Defendant, the instant

action and the Act under which it is brought constitute

State inference with the free practice of his religion which

interference violates The First Amendment of the United

State’s Constitution.

3.

The so called “ Civil Rights Act of 1964” under which this

action is brought violates XIVth Amendment in that it

seeks to deny Defendants equal protection of the law, seeks

to deny them the full enjoyment and use of their property

without due process, and seeks to abridge their privileges

10a

and immunities as citizens, in which instance it violates

also Article IV, Section 2 of the United States Constitution.

The said Act exceeds the power of Congress to regulate

interstate commerce and thus is violative of the commerce

clause in Article I, Section 8, of the United States Con

stitution.

The Constitutional questions above are not precluded

by prior decisions because of errors on the exercise of

judicial power therein violative of the basic rights of all

citizens as generally guaranteed by the United States Con

stitution.

4.

The existence, inviolate, of the United States Consti

tution, itself, and the form of law it guarantees are to

gether the most basic rights enjoyed by citizens of the

United States.

5.

Defendants deny Plaintiffs allegation that they were

“ forced to file this action” .

6.

Defendants deny Plaintiffs allegation that they suffered

and will continue to suffer from Defendants policy, practice,

custom and usage, as set forth in the Complaint herein and

demand strict proof thereof.

Answer

7.

Defendant Bessinger is an agent of Defendant Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., with a duty to enforce the policies

11a

of said Corporate Defendant, but as said agent has no

individual responsibility for the making of the policies.

W h e r e f o r e , Defendants respectfully pray that the Court

will dismiss the alleged cause of action against them, indi

vidually and/or severally.

5 February 1965

Answer

12a

First Amended Answer

(Filed: August 23,1965)

1.

Defendant Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. is a Corporation

duly organized and chartered under the laws of the State

of South Carolina; and owns and/or operates and/or fran

chises several restaurants in various communities within

the said State. Said Defendant denies that it is engaged in

interstate commerce, and asserts that it operates under an

announced policy of not catering to interstate travelers.

Said Defendant has been denied Federal trademark pro

tection on the ground that it is not in interstate commerce,

and has been discharged from the responsibility of paying

Federal minimum wages on the same ground.

2.

Defendant Bessinger believes as a matter of faith that

racial intermixing, or any contribution thereto, contravenes

the will of God. As applied to this Defendant, therefore,

the instant action and the Act under which it is brought

constitute State interference with the free practice of re

ligion which is violative of the United States Constitution

(U.S. Const. Amend. Art I).

3.

The “ ‘Civil Rights’ Act of 1964” is generally violative of

the United States Constitution, and specifically so in that

it: (1) denies the Defendants the equal protection of the

laws (US Const, Amend Art XIV, Sec 1; US Const Art IV,

13a

See. 1 ); (2) denies Defendants the full use and enjoyment

of their property by taking a substantial portion thereof

for alleged public use and benefit without due process and

without just compensation (US Const, Amend Art XIV,

Sec 1 ); (3) abridges Defendants privileges and immunities

(US Const, Art IV, Sec. 2 ); and (4) exceeds the Congres

sional power to regulate interstate commerce (US Const,

Art I, Sec. 8).

Defendants urge that these questions are not precluded

by prior decisions due to errors in the exercise of the

judicial power therein violative of the basic rights as gen

erally secured by the United States Constitution. The De

fendants would further insist that certain of these questions

are unique.

4.

The existence, inviolate, of the United States Constitu

tion, itself, and the form of law it guarantees are together

the most basic rights enjoyed by citizens of the United

States of America (US Const, Amend Art IX ; US Const,

Amend Art X ).

First Amended Answer

5.

Defendants deny the allegation that Plaintiffs were

“ forced to file this action.”

6.

Defendants deny the allegation that Plaintiffs suffered

and will continue to suffer from Defendants policy, prac

tice, custom and usage, as set forth in the Complaint,

and demand strict proof thereof.

14a

First Amended Answer

7.

Defendant Bessinger is an agent of Defendant Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., with a duty to enforce the policies

of said Corporated Defendant, and has no individual re

sponsibility for the making of the said policies.

W herefore, Defendants respectfully pray the Court to

dismiss the alleged cause of action against them jointly

and/or severally.

23, August 1965

15a

Motion to Amend

(Filed: March 19, 1966)

The Defendant moves the Court as follows:

1. To allow the Defendants to amend their Answer in

the above-entitled matter and to incorporate therein al

legations of denial that were overlooked heretofore in the

pleadings filed on behalf of the said Defendants; that

said amendments are set forth in a proposed Answer here

unto appended as Exhibit A ; that the reasons that said

Amended Answer is necessary are set forth in the Affidavit

of counsel hereunto appended as Exhibit B.

2. That this Motion is based upon the provisions of

Rule 15, Sub-Section (a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

and said Motion is made in the interest of justice in that

counsel has heretofore failed to properly deny certain

matters in the Complaint, which matters should have been

denied and that certain other defenses available to the

Defendants have not been adequately set forth in the plead

ings; that this Motion is further based upon an Order of

this honorable Court heretofore filed on February 24th,

1966.

3. That should this Motion be allowed, the Defendants in

this matter will be ready for trial on April 4th, 1966,

and that the granting of this Motion will not effect a delay

in the trial of this case.

4. That the Defendants herein further move the Court

to allow the Defendants herein to correct the answers

given in Interrogatories 10 and 11 for the reason that

16a

Motion to Amend

proper inquiry was not made by previous counsel as to

the information requested by the Plaintiffs in said Inter

rogatories; that the substance of this Motion is that this

matter was not heretofore adequately prepared and Defen

dants should be fully allowed their day in Court.

17a

Affidavit in Support of Motion to Amend

(Filed: March 19,1966)

Samuel B. B ay, Jr., being duly sworn deposes and states:

That he is attorney for the Defendants herein; that he

was retained after an Order of this Court relieving counsel,

and that he entered this case as of March 7, 1966.

That after carefully reviewing the pleadings heretofore

filed on behalf of the Defendants and after reviewing the

facts as well as pertinent statutes and court decisions rela

tive to the instant action, the undersigned is of the opinion

that the pleadings filed on behalf of the Defendants are

wholly inadequate to fairly and fully present the defenses

available to the Defendants.

That pursuant to the provisions of Buie 15, subsection

(a), Federal Buies of Civil Procedure, in the interests of

justice, counsel urges the Court to permit Defendants to

file an amended Answer setting forth such defenses as may

be available and to place the Defendants in such a position

as may allow them to remain in Court until all pertinent

evidence may be heard.

That counsel hereby agrees to be ready for trial on April

4th, 1966, as heretofore set by this Court even though an

amendment is allowed, and that this Affidavit is purely in

the interest of justice to the Defendants and not for the

purpose of delay in the determination of this action.

W herefore, counsel prays that the Defendants be granted

leave of this Court to amend their Answer and an Amended

Answer heretofore filed herein upon such conditions as the

Court may deem equitable.

18a

(Filed: March 30,1966)

For a First Defense

The Defendants admit the jurisdiction of this Court under

the provisions of Title 2 of the Act known as the “ Civil

Rights Act of 1964,” and Defendants deny the remaining

allegations of Paragraph One of the Complaint; Defendants

allege that they are without knowledge or information suffi

cient to form a belief as to the truth contained in Para

graphs Two and Four of the Complaint ; Defendants admit

so much of Paragraph Five thereof as alleges “ Defendant

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. is a corporation duly or

ganized and chartered under the laws of the State of South

Carolina. Said defendant owns and/or operates several

restaurants in various communities in the State of South

Carolina, two or more of which are located in the City of

Columbia. Defendant L. Maurice Bessinger is the Presi

dent of said corporation and is general manager of the

various restaurants operated by the corporate defendant” ;

Defendants deny each and every other allegation contained

in said Complaint.

For a Second Defense

The Defendants allege that they are not engaged in inter

state commerce, nor does their operation affect commerce

within the meaning and definition of Title 2 of the Act

known as the “ Civil Rights Act of 1964” ; Defendants fur

ther allege that they are not within Federal control or

regulation under the Commerce Clause, Article 1, Section

8, Clause 3 of the Constitution of the United States, that

Second Amended Answer

19a

in this connection, the Defendants have been denied Federal

trademark protection on the ground that Defendants are

not in interstate commerce, and Defendants have been dis

charged from the responsibility of paying Federal mini

mum wages upon the same ground.

For a Third Defense

The Defendants allege that Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., is not a place of public accommodation under Title 2

of the Act known as the “ Civil Rights Act of 1964” provid

ing for injunctive relief against discrimination in places of

public accommodation, in that (a) the Defendants’ opera

tion and business does not affect commerce, nor (b) does a

substantial portion of the food which it serves or other

products which it sells move in commerce, nor (c) do De

fendants serve or offer to serve interstate travelers, nor

(d) are the Defendants herein in commerce within the mean

ing and purview of Title 2 of the “ Civil Rights Act of

1964” ; the Defendants further allege that for the Defen

dants to be found affecting commerce it would be necessary

to find that the Plaintiffs herein and others similarly situ

ated would go without food as a result of a failure of the

Defendants to serve or provide food for said Plaintiffs.

For a Fourth Defense

1. That Title 2 of the Act known as the “ Civil Rights

Act of 1964” violates the Defendants’ rights under the Con

stitution of the United States in that (1) denies the Defen

dants the equal protection of the laws under Amendment

Article 14, Section 1, thereof and under Article 4, Section 1,

Second Amended Answer

20a

thereof; (2) denies the Defendants the full use and enjoy

ment of their property by taking a substantial portion

thereof for public use and benefit without due process of

law and without just compensation under Amendment Arti

cle 14, Section 1, thereof; (3) abridges Defendants’ priv-

leges and immunities under Article 4, Section 2; and (4)

exceeds Congressional power to regulate interstate com

merce under Article 1, Section 8, thereof.

2. The Constitutional question herein is not precluded by

prior decisions because of errors in the exercise of power

of judicial power therein violative of the basic rights of all

citizens guaranteed by the Constitution of the United

States, that as to the Defendants in this action the Con

stitutional questions raised are unique.

For a Fifth Defense

1. That Title 2 of the “ Civil Rights Act of 1964” under

which this action is brought violates the Defendants’ rights

under the 13th Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States and would impose a type of slavery or invol

untary servitude upon the Defendants, their servants,

agents or employees, in violation of their rights under

said Amendment.

2. The Constitutional question herein is not precluded

by prior decisions because of errors in the exercise of

power of judicial power therein violative of the basic rights

of all citizens guaranteed by the Constitution of the United

States, that as to the Defendants in this action the Con

stitutional questions raised are unique.

Second Amended Answer

21a

Second Amended Answer

For a Sixth Defense

That the Title 2 of the “ Civil Rights Act of 1964” under

which this action is brought violates the Defendants’ rights

under the 1st Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States in that Defendant Bessinger believes as a matter of

religious faith that racial intermixing or any contribution

thereto contravenes the will of God; that as applied to this

Defendant, the instant action and the Act under Avhich it

is brought constitutes Congressional interference with the

prohibition against interference of the free exercise of the

Defendant’s religion.

W h e r e f o r e , Defendants respectfully pray the Court to

dismiss the alleged cause of action against them jointly

and/or severally.

March 18,1966

22a

Transcript of Trial, April 4, 5, 1966

The Court: All right, gentlemen, calling for trial AC-

1G05, Anne P. Newman et al, vs. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., et al as Defendants. Mr. Perry representing the

Plaintiffs, are you ready?

—3—

Mr. Perry: Plaintiff is ready.

The Court: Mr. Ray, what about Defendants?

Mr. Ray: We are ready, if your Honor please, before

the trial commences one little thing—in drafting the

pleadings, and I discussed this with Mr. Perry we alleged

the denial of equal protection under law and denial of due

process under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitu

tion, which should have read the Fifth Amendment of the

Constitution. If we could make that change, I ’d appreciate

it, sir.

The Court: Is that in your Amended Answer?

Air. Ray: Yes, sir. It was in my Amended Answer.

The Court: What part?

Mr. Ray: The Fourth Defense, it has to do with the

due process and equal protection, should have been the

Fifth Amendment instead of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Mr. Perry said that he had no objection.

The Court: Is that in the first or second paragraph?

Mr. Ray: It is in the first paragraph, sir, of the Fourth

Defense.

The Court: What line?

Mr. Ray: It would be the 3rd line, 4th line, and 5th line.

They all pertain to the same thing there.

— 2—

23a

Opening Statements

The Court: Where you have the Fourteenth Amend

ment, you want to amend that to the Fifth Amendment?

Mr. Ray: Yes, sir, and both instances there where I

have the Fourteenth, it should have been the Fifth

Amendment.

The Court: Any objection to that, Mr. Perry?

Mr. Perry: No objection, your Honor.

The Court: All right. The Fourth Defense in the

Answer will be amended accordingly. All right, gentle

men, let’s proceed.

Mr. Perry: What is his Honor’s pleasure with reference

to the reading of the Pleadings?

The Court: Well I don’t care to have them read. If you

wish to make a brief statement, brief opening statement,

I will be glad to hear from you, and I will be glad to hear

what your position is; then I will give defense counsel a

like opportunity before we get into the testimony.

Mr. Perry: Thank you, your Honor. Well, of course,

your Honor I am sure is familiar with the pleadings, and

the issues therein framed in this case. The Plaintiffs

allege that on the dates alleged in the Complaint the Plain

tiffs, all of whom are Negroes, sought service at one or

more of the establishments operated by the defendants,

—5—

and they were refused such service because they are

Negroes. Action here is bought for an injunction pro

hibiting such discriminatory operation of the defendants’

businesses under Title II of the Civil Rights Law of 19G4;

and essentially, that is our position. The plaintiffs also are

seeking their costs in this proceeding, including reasonable

fees for their attorneys.

- 4 —

24a

The Court: Is it your position that the defendants are

in violation of Title II of the Civil Eights Act of 1964?

Mr. Perry: That is our position, your Honor.

The Court: Very well.

Mr. Ray: If your Honor please, we submit that the

defendants, and by our Answer, that they are not in

violation of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In

addition, and jurisdictionally, the plaintiff had alleged

several other Federal Statutes for jurisdiction, we don’t

see they are pertinent and the matter strictly arises from

Title II of the Civil Rights Act, more particularly Sections

201 and the folloAving sections in the Public Accommoda

tions Section. We deny that we principally are engaged

in selling food for consumption on the premises. We deny

that we sell a substantial amount of food that is moved in

—6—

commerce within the meaning of the Act, and we raise a

Constitutional question concerning due process of law in

sofar as the proposed Act would take property of the

defendants without due process, as well as the Act is arbi

trary, vague, indefinite and capricious insofar as this de

fendant, and others similarly situated under Section 201

b(2), and (c)—

The Court: Hadn’t that question already been decided

by the United States Supreme Court?

Mr. Ray: No, sir.

The Court: How about the Heart-of-Atlanta Motel case?

Mr. Ray: Pertaining to this, no, sir. That was a motel

and serving transients. We deny we are serving, or offer

to serve interstate travelers. We cut out that portion.

Opening Statements

25a

The Court: You deny that Piggie Park deals in inter

state terminals?

Mr. Ray: Yes, sir. We have evidence on that, if your

Honor please.

The Court: Well, of course, I am going to give you an

opportunity, but I am a little surprised that you deny that.

Mr. Ray: Yes, sir, we do, if your Honor please.

The Court: All right.

—7—

Mr. Ray: And that we do not come within the meaning

of the Act. Of course, I have stepped on to the fact that

the Act itself denies the defendant due process, and that

it is vague, arbitrary, and capricious insofar as the people

that come under it, and don’t come under it. It is con

ceivable after the only decision that has come down, and

established law, that certain restaurants or places that

are attempted to be covered could come without the Act,

and there is no standard by which a man could go about

setting up or determining when he comes under the Act,

and when he doesn’t come under the Act, but it would

depend, of course, upon the judicial decision in any one

of the Fifty District Courts of the land, on any given date,

and we claim there is a denial of due process of law because

of the arbitrariness and precedent for striking down

statutes that are so arbitrary in all of the decisions along

the due process line. Our further position is that it im

posed servitudes upon the defendants in violation of the

Thirteenth Amendment, and finally that it is an imposition

upon the freedom of the expression of religion of Mr.

Bessinger, as a citizen.

Opening Statements

26a

Mr. Perry: Shall we proceed with the presentation of

our evidence, your Honor?

The Court: Yes, sir.

Mr. Perry: Thank you, your Honor. Mr. Jenkins.

Mr. Jenkins: We call as our first witness Miss Sharon

Neal.

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Direct

Sharon N eal, called as a witness in behalf of the Plain

tiffs, who being first duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Jenkins:

Q. Miss Neal, what is your middle initial? A. W.

Q. So you are Miss Sharon W. Neal? A. Yes.

Q. Are you one of the Plaintiffs in this action? A. Yes.

Q. Miss Neal, are you a member of the Negro race? A.

Yes I am.

Q. Do you recall that sometime during the month of

August of 1964 you had occasion to visit one of the estab

lishments owned by the defendant, that is to say Piggie

Park Restaurant? A. Yes.

Q. Do you recall what day it was ? A. It was in August

of 1964, I don’t remember the date.

—9—

Q. August 12, 1964, is that correct? A. Yes.

Q. Do you recall the approximate time of day? A. I

am not sure. I believe it was around 2 :00 o’clock, I am not

sure.

Q. It was in the afternoon? A. Yes.

Q. Do you recall what particular establishment you

visited? A. It was the Piggie Park.

27a

Q. There are several Piggie Park establishments, do you

know that? A. Yes.

Q. Which one did you visit on that day? A. I don’t re

member. It was, I believe, on Two Knots Road.

Q. And does the Summerton Highway mean anything to

you? A. Yes.

Q. Is it not a fact that you visited the Piggie Park estab

lishment that is located on the Summerton Highway? A.

Yes.

Q. Is that in or near the City of Columbia, South Caro

lina? A. Yes it is.

— 10—

Q. Do you know that was called Summerton Highway is

U. S. Highway No. 78 and U. S. Highway No. 378?

Mr. Ray: If your Honor please, I would like to

object to counsel testifying and asking for a yes or

no answer.

The Court: Mr. Jenkins, this is your witness. I

ask you not to propound leading questions that indi

cate the answer.

Q. Miss Neal, were there other persons accompanying

you on this occasion? A. Yes.

Mr. Ray: If your Honor please, she said nothing

about other persons, and he’s still testifying.

The Court: He is asking if other persons were

with her. I think that is a proper question.

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Direct

A. Yes there were.

28a

Q. Do you know the names of those persons? A. Yes,

sir, I do.

Q. Would you state their names? A. Mr. Bernard

Moore, and Mrs. I. D. Newman.

Q. I. D. Newman? A. Yes.

Q. Is Mrs. Newman one of the plaintiffs also? A. Yes

she is.

Q. How did you arrive at this Piggie Park establish-

— 11—

ment? A. We went there to get something to eat.

Q. What was your mode of travel? A. We were in a car.

Q. A car? A. Yes.

Q. Do you recall the seating arrangements of the per

sons in the car? A. Yes I do.

Q. Who was driving the car? A. Mrs. Anne Newman

was driving.

Q. Where were you seated? A. I was seated in the back,

to the right of the car.

Q. Where was Mr. Moore seated? A. In the front seat.

Q. Now, did you drive on to the premises of the Piggie

Park? A. Yes we did.

Q. Do you recall anything that happened there which

attracted your attention? A. Yes. We noticed commo

tion in the kitchen among the people when they saw us

come in.

Q. Would you care to elaborate on that please? A. A

person came out and she saw us outside. They went back

- 12-

in and told the other people we were out there.

Mr. Ray: If your Honor please—

The Court: Did you hear her tell the other people?

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Direct

29a

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Direct

A. No I didn’t.

The Court: Well you can only testify to what

you know; not what you surmise or guess.

Q. After this person came out, saw you, went back into

the establishment, was a conversation between this person

and some other persons? A. Yes there was.

Q. You didn’t hear what was said? A. No I didn’t.

Q. Now, what portion of the establishment did this per

son come out? A. It was, I am not sure I believe it was the

side to the left of where I was facing.

Q. Would it be, was it from the main dining room, or

from some other part of the establishment? A. No, I

think it was the kitchen.

Q. Was this person dressed in any uniform, or any

peculiar manner of attire? A. No.

Q. Just ordinary attire? A. Yes.

—13—

Q. Could you determine whether this person was an

employee of the defendant? A. No I couldn’t.

Q. You couldn’t tell? A. No.

Q. Your testimony, I believe, has been that persons in

the restaurant came and watched you persons who were

in the car? A. Yes they did.

Mr. Ray: I can’t see any relevancy to that, that

people watched them.

The Court: Well, let’s go ahead, this is a non

jury case, and we don’t have to be too particular

what comes in and what doesn’t.

30a

Q. Could you determine whether these persons were

employees of the defendant? A. Yes they were.

Q. They were employees? A. Yes.

Q. Did any employee of this establishment ever come

out to the car where you were seated? A. Yes.

Q. Will you state what occurred thereafter ? A. Well the

waitress came out to take our order. "When she came near

the car, she turned around and went back inside.

— 14—

Q. Did she take an order? A. No she didn’t.

Q. Did you offer to make a purchase? A. Yes we tried.

Q. Thereafter did anything else happen? A. Yes. A

man came out later and he came over to the window as if

to take an order, but he didn’t. I mean to the car, he had

a conversation with Mr. Moore.

Q. Could you tell whether this person was an employee

of defendant? A. Yes he was.

Q. He was? A. Yes he was.

Q. Why do you say he came as though— ? A. He had

the ordering pad in his hand and a pencil and everything

as if to come take one.

Q. There was a conversation you say? A. Yes.

Q. Between this employee of the defendant and Mr.

Moore? A. Yes.

Q. Now, during that conversation, did anybody in the

car attempt to place an order? A. Mr. Moore did.

— 15—

Q. Did you over hear the conversation? A. Yes I did.

Q. Can you recall what was said generally? A. Yes.

Q. State what was said. A. Mr. Moore went ahead to

place an order. We gave our order to Mr. Moore, he went

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Direct

31a

to place it and the fellow that came to the car refused us.

He didn’t say why, and Mr. Moore tried to get him to say

why he refused us, but he wouldn’t.

Q. He never gave any reason why he did not take your

order? A. No.

Q. Did the person ever, this employee, ever state that

he would take your order? A. No he didn’t.

Q. Was there any other conversation between anybody

in the car and this employee? A. No.

Q. Did anyone else then come out? A. No, not after

that, no.

Q. Were you orderly in your bearing, well-behaved? A.

Yes.

Q. There was no argument—was there any argument?

A. No, there was no argument.

— 16—

Q. Was there any disturbance at all? A. No.

Q. Was any reason given for you not being served? A.

No there wasn’t.

Q. Were you ever served on that occasion? A. No.

Q. Miss Neal, were there other cars parked in this area

when you drove up? A. Yes. Approximately three.

Q. Three cars? A. Yes.

Q. Did you observe the persons in those cars? A. Yes

we did.

Q. Do you recall whether those persons had been served?

A. Yes, they were eating at that time.

Mr. R ay: If your Honor please, I don’t see where

that would be relevant at all.

The Court: Well I will let it come in, go ahead.

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Direct

32a

Q. You say they were eating? A. Yes they were.

Q. They were on the premises of the defendant? A.

Yes.

Q. Did you observe the race of these people? A. Yes.

— 17—

Q. Were any of them Negro? A. No they were not.

Mr. Jenkins: Your witness.

Cross Examination by Mr. Ray:

Q. Miss Neal, have you ever been to the Piggie Park

Enterprises since this time in August? A. No I haven’t.

Q. Prior to August, 1964, had you ever been in Piggie

Park Enterprises? A. No.

Q. Any establishment of Piggie Park Enterprises? A.

No.

Q. You are sure of this? A. Yes I am.

Q. Have you ever been refused service at any other

restaurants in Columbia? A. Yes I have.

Q. Any other places of business? A. Yes.

Q. At any of those places of business did anyone tell

you why they were not going to serve you? A. Yes they

did.

Q. They did not tell you? A. They did.

— 18—

Q. They did not tell you this at Piggie Park? A. No

they didn’t.

Q. Do you live in Columbia? A. Yes, now I do, yes.

Q. Did you live in Columbia at that time? A. Yes I was

living there.

Q. Do you eat out at restaurants very often? A. Not

very often; I do sometimes.

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Cross

33a

Q. On this particular day, you have remembered what

you did, what did you do after you left Piggie Park?

Mr. Jenkins: Your Honor, at this point we see

no connection between the line of questioning and

the matters before the court.

The Court: Well, as I told Mr. Ray in the begin

ning, this is a non jury case, not a jury case, and

I am not going to adhere strictly to the rules of evi

dence, and rules of relevancy. A good many matters

will be brought out that probably won’t be relevant,

but it is left up to the court to determine what is and

what is not.

Q. What did you do? A. I returned to school.

Q. To school? A. Yes.

— 19—

Q. Where did you go to school? A. Benedict College.

Q. Benedict College. Did you, on this particular day, did

you eat dinner that day? A. Yes I did.

Q. And what time did you eat dinner this day? A. I

believe it was around 4 :00 o’clock. I am not sure.

Q. What time did you eat breakfast?

The Court: Mr. Ray, I let you go into this, but

I mean I just don’t see any point in following this

to its illogical conclusion, unless you can point out

to me what the relevancy of it is.

Mr. Ray: That is all right, sir.

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs—Cross

34a

Q. But at no time, Miss Neal, did anyone tell you that,

at Piggie Park, did anyone tell you you were being refused

food because you were a Negro? A. No they didn’t.

Q. Was it said to anyone in that automobile? A. No.

The Court: Is that all, Mr. Ray?

Mr. Ray: Yes, sir.

Redirect Examination by Mr. Jenkins:

Q. Miss Neal, did you testify in answer to a question by

—2 0 -

counsel, you are a student? A. Yes.

Q. Now where is your native home? A. New York City.

Q. Why are you in Columbia? A. I am attending col

lege there.

Q. Is that your reason for being in Columbia? A. Yes.

Q. Are you living in Columbia temporarily then while

in school? A. Yes I am.

Q. Is it your intent to return to the State of New York

after you complete your training? A. Yes.

Mr. Jenkins: That is all.

The Court: All right. Step down.

Mr. Perry: Mr. Price.

Sharon Neal—for Plaintiffs■—Redirect

35a

L eonard L. Price, called as a witness in behalf of the

plaintiffs, who being first duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Perry.

Q. Would you state your name and address, please! A.

I am Leonard Price, Columbia, South Carolina, president

of Germany Roy Brown Company, 911 Washington St.

—21—

Q. Mr. Price, what is the nature of the business of

Germany-Roy-Brown and Company! A. We are in the

wholesale beer business.

Q. Would you tell use please what products your com

pany distributes! A. We sell Budweiser, Bavarian, and

Michelob.

Q. Can you tell us, Mr. Price, whether your company

sells beer, or other supplies, to the Piggie Park Enter

prises of which Mr. L. Maurice Bessinger is president! A.

We did. Of course today he does not have a beer license,

and we don’t sell him now.

Q. When is the last time your company sold beer to Mr.

Bessinger’s enterprises! A. About mid 1964 I believe.

I don’t have the exact time.

Q. About mid 1964! A. Yes.

Q. All right, then. Can you tell us please whether—

you say about mid 1964, do you have any recollection

whether you have sold Mr. Bessinger’s enterprises any

beer products since July 2, 1964! A. I couldn’t specifi

cally state that we have. He bought a new beer license,

I believe in 1964 at the beginning, which was July 1, and

we sold him until he decided to discontinue beer.

* • * • *

Leonard L. Price—for Plaintiffs—Direct

# # ** #

—110—

36a

S haron M iles, called as a witness in behalf of the Plain

tiffs, who being first duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct Examination hy Mr. Pride:

Q. Please state your full name and address? A. Sharon

A. Miles, Columbia, South Carolina.

Q. How long have you lived in Columbia, South Carolina ?

A. Year and a half.

Q. And prior to that where did you live? A. Blooming

ton, Indiana.

Q. Are you a permanent resident of South Carolina?

A. No I am not.

Q. Where are you planning on residing? A. Washing

ton, D. C.

Q. Washington, D. C. Have you ever had occasion to

enter one of Piggie Park stores owned by Mr. Bessinger in

Columbia? A. Yes, I have, last Saturday.

—Ill—

Q. Last Saturday? A. Yes, sir.

Q. I believe that would be the second of April, is that

correct? A. That is correct.

Q. About what time was that? A. Around 1:00 o’clock

in the afternoon.

Q. Could you tell us exactly where that establishment was

located? A. On Main Street in Columbia.

Q. On Main Street. Would you describe the inside of the

establishment? A. Yes. There is a line to the left of the

building where the food is distributed, and along the right

as you enter on the righthand wall there are tables at which

you are seated.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Direct

37a

Q. In terms of whether it a restaurant or cafeteria style,

which one is it? A. Cafeteria.

Q. Cafeteria style. Were you greeted at the door by any

of his employees? A. No I was not.

Q. Tell us, did you just go in and take a seat? A. I went

in, stood up and got my food, then I went to my table and

sat down.

— 112—

Q. Did anybody inquire of you where you were from?

A. No they did not.

Q. Did anybody make any demands upon you? A. No

they didn’t.

Q. Of presenting any type identification or anything?

A. No, none.

Q. So no one knew where you were from while you were

in there? A. That is correct.

Q. What did you order? A. Sandwich and a cup of

coffee.

Q. Did you see any other Negroes in there? A. No I

did not.

Q. They were all white? A. Yes, as far as I could tell.

Q. Did you have occasion to observe any of the products

that were being sold in there? A. Well besides there was

the food displayed as they were preparing it along the table

that we were getting our food, and there were a few large

cans of food underneath one of the tables to the left.

Q. Do you know what type of food that was? A. I am

sorry I don’t remember.

Q. Could you see where any town or state was marked

on it? A. I don’t remember specifically.

You don’t remember? A. No.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Direct

— 113—

38a

Mr. Pride: Would you induge me just a moment,

your Honor.

Q. When you got ready to leave, did anybody make any

demands on you, or ask you any question as to where you

were from? A. No they did not.

Q. Do you know the general policy of the proprietor or

Mr. Bessinger in that particular place? A. Yes I do.

Q. Do you know it in regard to race? A. Yes I do.

Q. Would you tell us please? A. Yes. There is a sign

on the restaurant that I went into in Columbia which I be

lieve said we cater to white trade only.

Mr. Pride: Answer any questions Mr. Ray may

ask you please.

Cross Examination by Mr. Ray:

Q. Where do you live? A. I live in Columbia.

— 114—

Q. How long have you been there? A. About a year and

a half.

Q. About a year and a half. What do you do there? A.

I am a housewife.

Q. Does your husband live there? A. Yes he does.

Q. Does he work there? A. Yes he does.

Q. Before you entered this place of business—you are

Mrs. Miles? A. Yes.

Q. Where is your husband from? A. Originally?

Q. Yes. A. From Little Rock, Arkansas.

Q. From Little Rock, Arkansas? A. Yes.

Q. Are you a college graduate? A. Yes I am.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Cross

39a

Q. What school did you go to? A. University of Cali

fornia.

Q. And how old are you? A. I am twenty-six.

Q. Twenty-six, and your husband a college graduate?

A. Yes he is.

—115—

Q. Where did he go to school? A. University of Cali

fornia, A.B. Degree; and a Master’s Degree from Indiana

University.

Q. What does he do? A. He is director of the South

Carolina Voter Education Project.

The Court: What is his position?

A. Director.

The Court: Of what?

A. South Carolina Voter Education Project.

Q. Who sponsors the South Carolina Voters Education

Project? A. It is an independent organization.

Q. I beg your pardon? A. Independent.

Q. By independent, what do you mean? A. Well I mean

they are self-supporting.

Q. Well when you went into the Piggie Park place on

Main Street, did you look in the window? A. No I did not.

Q. As you went in? A. No I did not.

Q. Then how did you see a sign there that said we cater

to white trade only? A. I passed the Piggie Park many

times. I have noticed the sign before.

— 116—

Q. Is that the Piggie Park you went in? A. Yes I be

lieve it was.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Cross

40a

Q. Right there (exhibiting photograph)? A. Yes.

Q. Is that a reasonable representation of the front of it

at the time you went on Saturday? A. I don’t remember

this sign right here. As far as I can, otherwise it is.

Q. What is your husband’s name? A. Richard Miles.

Q. Richard Miles, and do you classify yourself as a Ne

gro or white person ? A. I am Caucasian.

Q. Caucasian, and your husband? A. He is Caucasian.

Q. And you lived in Columbia, South Carolina, for a year

and a half? A. That is correct.

Q. What is your address there? A. 1208 Hardin Street.

Q. When you walked into this place, did you speak to

anyone? A. I did not except to the woman who took my

order.

Q. That took your order. A. Yes, sir.

— 117—

Q. Well you said just now this place was cafeteria style.

A. Yes.

Q. And when you move, do you pick up your food as you

move down the line? A. I ordered from her. She pre

pared my food, then I moved down the line and someone

gave me my cup of coffee.

Q. How was the food laid out, they cook— ? A. She

prepared the sandwich in front of me along the counter

right below where the tray is.

Q. How did she prepare it, what did you order? A. A

sandwich.

Q. What kind? A. A barbecue.

Q. A barbecue sandwich? A. Yes.

Q. And was it sliced barbecue or chipped barbecue? A.

I believe it was chipped.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Cross

41a

Q. And it was put on bread or buns? A. On a bun, yes.

Q. And then after that was done, what did the person

that waited on you do with the food? A. She handed it to

me.

Q. Did she hand it to you with her hand? A. As I re

member she handed it to me on a plate.

—118—

Q. What kind of plate? A. I am sorry, I don’t

remember.

Q. Was it a paper plate or China plate? A. I don’t re

member. I think it was a paper plate because I think I

remember depositing it in a trash basket.

Q. And was it just a small plate or paper tray kind of

affair? A. I think it was a small plate.

The Court: I had a tray.

Q. And how many people were in the place when you

went in at 1:00 o’clock about? A. There were about six

or eight other people, I think.

Q. Was there a steady stream of people coming through

there or just a few? A. When I came in there was a small

line, but after a while it sort of trickled off. There was not

a large number of people at the time I ate.

Q. Most of the people that were in there, did they sit

down to eat? A. As I remember all of them did. I don’t

remember anyone just taking an order and going out.

Q. Was there any wax paper around your sandwich

when she handed it to you? A. I don’t believe there was,

but I am sorry I don’t remember exactly.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Cross

42a

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Cross

—119—

Q. Wliat type of spoon were you served with your cof

fee? A. I was not served a spoon.

Q. Did you obtain one? A. No I did not.

Q. You drank your coffee black? A. That’s right.

Q. Your coffee was in a glass cup? A. I believe it was

a China cup, I am sorry I can’t remember.

Q. You don’t really know. You say it is your testimony

you lived in Columbia for a year and a half? A. Yes, sir,

that is correct.

Q. And how did you happen to go down to Piggie Park

this past Saturday, is that your usual place of eating? A.

No it is not. This is the first time I been in the cafeteria.

I have eaten at Piggie Park other places.

Q. Piggie Park other places, you mean in Columbia? A.

No, I have eaten in Piggie Park in Orangeburg.

Q. And you never been at 1430 Main Street, Piggie Park

there before until last Saturday? A. That is correct.

Q. And why did you go there? A. My husband asked

me to go there.

— 120—

Q. Your husband? A. Yes.

Q. Asked you to go there? A. Yes.

Q. Did you ask him why? A. Yes I did.

Mr. Perry: Your Honor, may I submit that the

reason the witness went to the defendant’s place of

business is without relevance.

The Court: Will you let him finish?

Mr. Ray: But he’s fixing to testify why she went

there.

43a

The Court: I will let him finish.

Mr. Perry: May I submit the reasons behind the

witness’s going to the place of business are without

relevancy and can serve no useful purpose to these

proceedings. That is the basis.

The Court: You object to this line of

questioning1?

Mr. Perry: I do.

The Court: All right, Mr. Ray. I will hear from

you now.

Mr. Ray: I have nothing further to ask the

witness.

The Court: Well what is the relevancy of this

- 121-

line of questioning?

Mr. R ay: I was actually testing what her motives

and everything else was in going there, your Honor.

They have alleged—I am trying to find out the rele

vancy of why she went there. I assumed that he

intends to prove by her going there that this was

an interstate traveler I guess. I really don’t know,

but I was trying to find out. And in addition to

that, she remembered quite a bit of things that I

was trying to find out how much more she remem

bered. She didn’t remember but one sign in the

window, and there was another one there right with

it just as big or bigger than that was.

The Court: Do you have any more questions?

Mr. Ray: No, sir. I think that is plenty.

Mr. Pride: You may come down.

Mr. Perry: Plaintiffs rest, your Honor.

Sharon Miles—for Plaintiffs—Cross

44a

The Court: All right.

Mr. Ray: May I have just a few minutes, your

Honor, I will appreciate it.

(The hearing recessed briefly and reconvened.)

The Court: All right, Mr. Ray.

Mr. R ay: If your Honor please, for the record we

would like to move to dismiss the Complaint of the

Plaintiffs, first that this was apparently a class

action. There is no evidence whatever to indicate

— 122—

that Mr. Bessinger’s employees, whoever they might

have been at that particular time, refused to serve

the only person that has testified Sharon Neal be

cause of race.

The Court: Well that is the testimony here that

posted signs on the premises say that they only

cater to white.

Mr. R ay: That is at one of the businesses, if your

Honor please. There are four. That is the down

town business at 1430 Main Street.

The Court: Well you are saying there are not

signs at the other places?

Mr. Ray: No, sir. I am not saying that, no, sir.

There has been no, secondly, there has been no proof

offered whatsoever that there has been any service

or offer to serve interstate travelers. Now Mrs.

Miles was put on the stand, and it developed she had

been living in the State of South Carolina for a year

and a half, and I don’t see how she could possibly

come within the term interstate traveler by any

stretch of the imagination.

Motion to Dismiss

45a

The Court: Well is it your position he doesn’t

serve interstate travelers?

Mr. Eay: That’s right, sir.

The Court: What does he do to protect himself

—123—

from serving them?

Mr. Eay: Well if your Honor requires us to go—

The Court: I stopped on several occasions at

the one on West Columbia and pushed the button

where no one could see if I was in South Carolina

license, no one asked me whether I was intra or

interstate, whether I was a resident of South Caro

lina or North Carolina.

Mr. E ay: That’s right, but we will have some evi

dence on that.

The Court: I overrule your motion on that

ground.

Mr. E ay: And thirdly that there has been no evi

dence introduced to show that a substantial portion

of the food that he serves has moved in commerce,

food as distinguished from some other items, if your

Honor please. There is nothing to measure that by

that has been introduced.

The Court: What is your conception of the legal

definition of substantial?

Mr. E ay: If your Honor please, that is one of the

basis of one of our defenses that it is incapable at

any given time of being the same thing.

The Court: That is a matter of factual determina

tion of the Court after hearing the evidence. I have

Motion to Dismiss

46a

Motion to Dismiss

—124—

certainly heard enough evidence to make a prima

facie showing there is a substantial amount of food

products traveled in interstate commerce. The last

witness alone, Mr. Wilkerson, testified they sold to

the defendant in the year 1964 some forty thousand

dollars worth of merchandise, in 1965 some thirty-

two thousand dollars worth of merchandise, two-

thirds of which would have traveled in interstate

commerce they purchased from out of the state.

That, to me, is a prima facie showing of a substan

tial amount.

Mr. Ray: Depending on what you are measuring.

The Court: Of course $10 is a substantial amount

as to say $15 to $25, but $10 may not be a substan

tial amount as to $100,000. But I surely say that as

of right now, there is a prima facie showing that the

defendant is serving a substantial quantity of food

stuffs that have moved in interstate commerce. That

may be rebutted by your evidence, but I would say

as of right now, that is a prima facie showing.

Mr. Ray: All right, sir.

The Court: Any other motions? Your motion

based on any other ground? Motion to dismiss

— 125—

based on any other grounds?

Mr. R ay: I would like to base it— I think that will

be all. Call the first witness Miss Merele Brigman.

47a

M erele Brigman, called as a witness in behalf of the

Defendants, who being first duly sworn, testified as follows:

The Court: Let the record show I overrule the

motion on all grounds. We proceed to take the testi

mony of Defendants.

Direct Examination by Mr. Ray :

Q. Your name is Mrs. Merele Brigman? A. Yes.

Q. Where do you live ? A. Columbia.

Q. And by whom are you employed? A. Piggie Park

Enterprises.

Q. And what is your job, Mrs. Brigman? A. I am book

keeper and buyer.

Q. And do you make all of the purchases for Piggie Park

Enterprises? A. The majority, yes.

Q. Do you keep in your possession or in your custody

all of the records pertaining to it? A. I do.

— 126—

Q. How long have you been working for Piggie Park

Enterprises? A. Two years March 23.

Q. At my request have you examined the records for

Piggie Park Enterprises back over the past couple of years?

A. Yes, sir, I have.

Q. What basis does Piggie Park keep its books, on a

calendar year basis or fiscal? A. Fiscal year, June 1st to

May 31st.

Q. And have you had occasion to go over the food and

related items purchased during the year, fiscal year 1963-

64, ’64-65 and for the first six months of ’65-66? A. Yes,

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Direct

sir.

48a

Q. And do you know, have you compiled those records?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And at whose request did you do this? A. Yours.

Q. For the fiscal year 1963-64, what were the total pur

chases, what is that that you have in your hand? A. This

is a photostatic copy of a chart I made totaling up the in

voices of each supplier that we bought from.

Q. What are the total purchases for food and related

- 1 2 7 -

items by Piggie Park? A. From June 1st of 1963, through

May 31 of ’64 we bought $240,565.58.

Q. All right, maam. 1964-65? A. We bought $222,-

845.26.

Q. Is that correct, that last figure? A. Yes, sir. June

1st, ’64 through May 31, ’65.

Q. And for the first six months of ’65-66? A. This is

through December 12, 1966 we bought $122,724.13.

Q. You mean ’65 through December 12, 1965. A. No, sir,

June 1st, 1965 through December 12, 1966. Oh, I ’m sorry,

yes, sir. ’65. I ’m sorry.

Q. And did you tabulate those total purchases? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Have you had occasion to visit the various Piggie

Park Enterprises? A. Yes, sir.

Q. I ’d like to ask you, Mrs. Brigman, if you recognize

that picture? A. Yes, sir. That is Piggie Park on Two

Knots Road, which is known as Piggie Park No. 3.

Q. How about this one, do you recognize it? A. Yes,

sir. That is Piggie Park, Sumter Highway, which is Piggie

Park No. 2.

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Direct

49a

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Direct

—128—

Q. That one? A. That is Little Joe Sandwich Shop,

downtown Main Street.

Q. And this one? A. That is the Piggie Park on

Charleston Highway, which is known as Piggie Park No. 1.

Mr. Perry: We have no objection.

The Court: Very well.

Mr. Kay: If your Honor please, I have four

photographs I would like to introduce.

The Court: Defendants’ A, B, C, and D.

Q. Mrs. Brigman, are there any signs pertaining to in

terstate travelers, or service to interstate travelers located

on the premises of Piggie Park Enterprises? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And what do those signs say? A. We do not serve

interstate travelers.

Q. Are they posted in the window? A. Yes, sir, they

are in the window.

Q. And when were those signs put there, do you know?

A. Not the exact date, no, sir, but it has been a couple of

years.

Q. Thank you, maam. And do those signs appear on each

of the photographs that I have here in my hand? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Have you made any effort to determine what per-

—129—

centage or percentages of the food purchased has been pur

chased from suppliers without the state with reference to

articles being ground, manufactured, or packed, processed

within this state? A. You want within this state or out?

50a

Q. With reference to that, have you made any effort to

determine what percentage of the food that is purchased— ?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And for the year 1964-63-64, what percentage was

that? A. Food processed and/or manufactured in South

Carolina?

Q. Yes maam. A. I came up with 75% of the total

amount of money spent for foods.

Q. All right, maam. And how about 1964-65? A. The

same thing.

Q. How about the first part of ’65-66? A. Well I came

up with 82%.

Q. Is there any reason for the difference there? A. Yes,

sir. We buy as much as possible of processed food in South

Carolina, and every day I am searching for new suppliers

that process their food in South Carolina.

Q. And/or grow it? A. Yes.

— 130—

Mr. Ray: I have no further questions.

Cross Examination by Mr. Jenkins :

Q. Mrs. Brigman, what effort is made by the Piggie

Park Enterprises at the various establishments to deter

mine whether a prospective purchaser is an interstate

traveler? A. You mean a customer?

Q. Yes. A. I am sorry, would you repeat the question.

Q. Maybe I should elaborate a bit. You say these vari

ous establishments have signs posted which say in effect

we do not cater to interstate travelers, is that correct? A.

Yes. We do not serve interstate travelers.

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Cross

51a

Q. Now, my question is, what effort is made by the par

ticular establishment to determine whether a person who

offers to purchase is in fact an interstate traveler or not?

A. The only way we have is by the car license.

Q. Car license? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now explain what the procedure is when a car comes

up with a customer. A. Well if a car comes up with a

customer and we see that he is from out of state we tell

them we do not serve interstate travelers.

Q. Do you know that as a fact? A. Yes, sir.

— 131—

Q. Do you visit the various establishments? A. Well

my office is right next door to one on Sumter Highway.

Q. You observe every car that comes up? A. No, sir.

Q. Now, with reference to the three other establishments,

how do you justify your statement? A. Well I am in

charge of all of the records, and we write a ticket for each

customer that comes up and orders over our intercom sys

tem, and if the girl, the curb girl when she is out on the

curb she sees these cars, and I have when these tickets

come through the office we have tickets that are voided, and

each ticket has to have a reason on the back, and it says

that this was an out of state customer and therefore they

voided the ticket and did not serve them.

Q. Now, do you know whether there may be out of state

customers served and tickets not voided? A. Well, I don’t

know, sir.

Q. So then this alleged check which you say you follow is

not then an accurate measurement on what takes place is

it? A. No, but those are the ones I know. You asked me

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Cross

52a

how do I know for a fact; those are the ones I know for a

- 1 3 2 -

fact that are not served.

Q. Insofar as you know any particular day you may

have ten tickets voided because of out of state license on

the car ? A. That’s right.

Q. When in fact there may have been 200 persons served

with out of state license? A. Well we may catch them be

fore the ticket is written and rung up. If that is the case,

we do not write a void ticket.

Q. My question is, is it quite possible under your system

of check that 200 out of state cars, occupants, may in fact

be served and you only void five out of state? A. Well

no, sir. 200 is too many because we don’t have that many

customers a day at one particular drive-in because we do

have a count of our customers.

Q. That of course, the figure I used is taken out of the

sky. All I am getting at is you really have no method.

This method you now mention is not an accurate method

of who may be served there? A. That’s right.

Q. That is correct, is it not. Every order that is placed

in your establishment is indicated by a ticket? A. Yes.

Q. Those tickets come into your possession? A. Yes.

— 133—

Q. You have any of them with you? A. No, sir.

Q. You knew you were going to be a witness here today

didn’t you? A. Yes.

Q. And you knew you would testify as a person who is in

charge of records of the defendant corporation, is that not

correct? A. Yes.

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Cross

53a

Q. And you made no effort to bring with you these rec

ords which you reasonably could have anticipated that you

would ask for? A. Well, no.

Mr. Ray: If your Honor please, I don’t think that

question is proper question. She wasn’t to anticipate

every question that counsel would ask her.

Mr. Jenkins: I feel certainly—

Mr. Ray: It goes into conjecture. They have an

established practice. They can’t go out and take the

pedigree on everybody that comes on the lot. All

they can do is make a reasonable effort, and I think

they have done that.

The Court: Well that is for me to decide and not

for you.

—134—

Mr. Ray: Yes, sir, I understand that.

The Court: I want to hear everything I can that

assist me in making that determination. As I un

derstood his question, he’s merely asking her whether

or not she knew she was going to be a witness and

she would in all probability be called upon to testify

as to the practice of the defendant in what it did or

did not do in reference to the service of interstate

travelers.

Mr. Ray: Yes, sir. I didn’t mean to insult the

Court.

The Court: I am going to let him go into that.

That, as I understand, is one of the issues that must

be determined by the Court in reference to this case.

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Cross

54a

Mr. Ray: I didn’t mean to insult the Court. I

merely thought I should interpose the objection at

that time, and that I would have been amiss, as

counsel, if I hadn’t done so.

The Court: All right.

Q. Mrs. Brigman, I believe you say you do not have those

records? A. No I do not.

Q. Can you obtain those records? A. No I can not. I

can for this week. We throw them away. Now I keep all

- 1 3 5 -

void tickets, but we only have carbon copy because the

customer gets the original, and after we check them they

are thrown away.

Q. You keep them only a week? A. That’s right.

Q. Yet you say you keep these void tickets. You care to

tell us why you keep the void tickets? A. Well because

on our register we have a running total of the sales and a

void ticket is rung up and so therefore it is counted as a

sale, and on my sales report I subtract these void tickets

so the manager is not responsible for only the money that

she has collected. Therefore for audit purposes, I have to

keep these void tickets so he can see why I am subtracting

this money.

Q. I am not certain I quite understand your use of the

void tickets. Perhaps you testified, but tell us again, when

a void ticket is used, when is a ticket voided? A. Well if

the person ringing up the order on the register should make

an error in charging a customer, it is voided and rewritten,

that is one case. As I stated, if it is an interstate traveler

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Cross

55a

and we do not catch it until the ticket has been rung up,

that would be a void ticket.

Q. If I may stop you right here. That is what I am a bit

puzzled about. Do you mean to say a person may come up,

- 1 3 6 -

interstate travelers and order and be served and you later

determined that person was an interstate traveler and the

person doesn’t have to pay for it? A. Oh no, that’s not

what I mean at all.

Q. Explain to me so I understand what you mean. A.

Well when some periods of the day we are real busy, and

we may not catch them. We take the order as the button

is pushed and it may not be until a few minutes later that

a girl or lady notices the interstate traveler. Then we may

not even be prepared the food, but it is already taken and

rung up and over there on the line to be prepared.

Q. Then under that circumstance you then advise the

interstate traveler we can not serve you? A. That is right.

Q. But your ticket would have showed that you had

served that person? A. No, it will say on the back this

ticket voided because of interstate traveler, and that is why

the ticket is voided because we didn’t serve him and collect

the money. If we collect the money we don’t void a ticket.

Q. That is your own method then of determination

whether a person is out of state traveler? A. That is my

only way. That is the only proof I have through the office.

Now the managers of the drive-in have their proof, their

word, and their girls’ word.

— 137—

Q. But as far as you’re concerned you only have the

tickets which come into you? A. That’s right.

Merele Brigman—for Defendants—Cross