Robinson v Adams Petition Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1988

154 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robinson v Adams Petition Writ of Certiorari, 1988. aebe46b1-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/60ca048a-2a59-4717-8f33-29b3b05ef68c/robinson-v-adams-petition-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

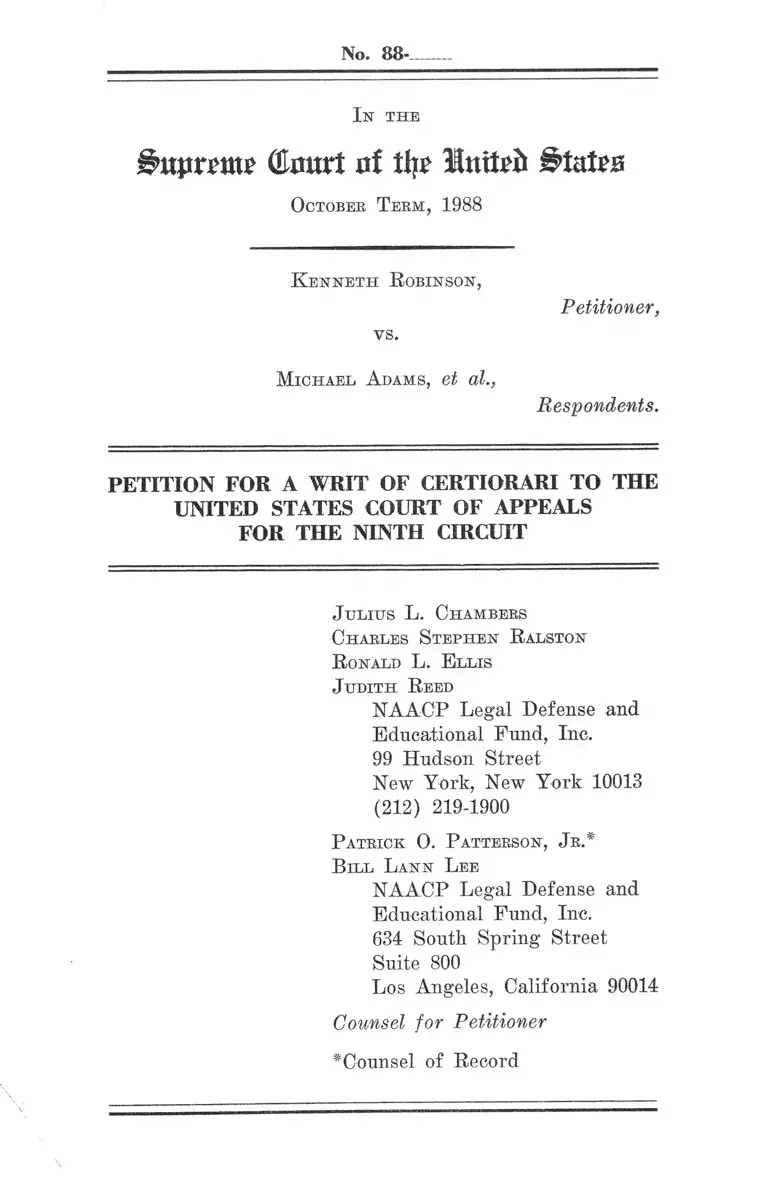

No. 88-

In THE

l̂ ttpran? (tort of tty Itutefi States

O ctober T e em , 1988

K e n n e t h R obinson ,

vs.

Petitioner,

M ich ael A dams, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

J u liu s L. C hambers

C harles S teph en R alston

R onald L. E llis

J u d ith R eed

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

P atrick 0 . P atterson , Jr.#

B ill L an n L ee

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street

Suite 800

Los Angeles, California 90014

Counsel for Petitioner

^Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether, in a Title VII dis

parate impact case challenging discrimina

tion against black men, an employer with

no black male employees is entitled to

summary judgment based on the fact that it

has some black female employees.

2. Whether, in order to withstand a

motion for summary judgment, the plaintiff

in a Title VII disparate impact case is

required (a) to establish adverse impact,

(b) to identify specific employment

practices or selection criteria, and (c)

to show the causal relationship between

the identified practices and the adverse

impact.

3. Whether summary judgment is

appropriate in a disparate treatment case

under Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 where

the record contains conflicting evidence

as to the employer's knowledge of the

plaintiff's race.

ii

LIST OF PARTIES

The parties to the proceedings below

were petitioner Kenneth Robinson and

respondents Michael Adams, Dianne R. Coe,

Georgia McCarthy, Martin Moshier, Lura

Scovil, Joan Wilson, County of Orange,

Orange County Superior Court, and L. B.

Utter. Ben Avillar and Maria Bastanchury

were also named as defendants in the

district court.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ............ i

List of Parties........... ii

Table of Contents . . . . . . . . iii

Table of Authorities....... v

Opinions Below. . 1

Jurisdiction............... 3

Statutes Involved .............. 3

Statement of the Case..... 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ . . 20

I. The Ninth Circuit Majority'sRejection of Petitioner's Title

VII Disparate Impact Claim of Discrimination Based on Race and Sex Is Contrary to the Decisions

of this Court and Inconsistent

With the Decisions of OtherCircuits.................. 28

II. This Court Has Granted Certiorari In

Another Case to Review the Prima Facie Case Standard Applied By the Ninth Circuit to Disparate Impact

Claims Under Title VII.. . . 28

III. The Ninth Circuit Majority's

Affirmance of Summary Judgment Against Petitioner on His Claims

of Intentional Discrimination,In the Face of Conflicting

IV

Evidence, Is Contrary to the Decisions of this Court.

Moreover, this Court Has Granted

Certiorari In Another Case to

Review A Substantially Similar

Question.................. 3 0

Conclusion......................... 33

Appendix

Opinion of the Court of Appealsfor the Ninth Circuit. . . . 4a

Final Judgment of the District CourtMemorandum and Order . . . . 18a

Second Partial Report and Recommen

dation of United States Magis

trate Partial SummaryJudgment..................... 34a

Order Adopting Findings, Conclusions, and Recommendations of United

States Magistrate ............ 79a

Partial Report and Recommendation ofUnited States Magistrate . . 81a

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477 (9th Cir. 1987), on remand. 827 F.2d 439 (9th Cir.

1987), cert, granted. 56 U.S.L.W.

3887 (June 28, 1988) . . . 15,16,29,34

Chambers v. Omaha Girls Club, 629 F.Supp. 925 (D. Neb. 1986), aff'd. 834 F.2d 697 (8th Cir. 1987) . . . 26

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440

(1982) . . . 18,21,22

DeGraffenreid v. General Motors

Assembly Division, 558 F.2d 480 (8th Cir. 1977) . . . 26

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters,438 U.S. 567 (1978)... 22

Graham v. Bendix Corp., 585 F. Supp.1036 (N.D. Ind. 1984).... 27

Harbison-Walker Refractories v. Brieck,

No. 87-271, 56 U.S.L.W. 3647 (March 21, 1988)........... 32

Hazelwood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977) . . . 18

Hutchinson v. Proxmire, 443 . . . . 32

Hicks v. Gates Rubber Co., 833 F.2d 1406 (10th Cir. 1987) ........ 26

vi

Jeffries v. Harris County Community Action Association, 615 F.2d 1025 (5th Cir. 1980) . . . 18,23,24,25,26,27

Los Angeles Department of Water & Power

v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978) . 18,21

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973)............ 3

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp.,400 U.S. 542 (1971)........ 21,22,24

Poller v. Columbia Broadcasting System,

Inc., 368 U.S. 464 (1962) . . . . 32

Tagupa v. Board of Directors, 633 F.2d1309 (9th Cir. 1980) . . 8,13,14,15

White Motor Co. v. United States, 372

U.S. 253 (1963)............ 32

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) . . . . . . . . 3

Age Discrimination in Employment Act of

1967, 29 U.S.C. § 621 et seq . . . 32

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a). . . . passim

42 U.S.C. 1981............... passim

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1988

KENNETH ROBINSON,

Petitioner.

v.

MICHAEL ADAMS, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT" CU^CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH

CIRCUIT

The petitioner, Kenneth Robinson,

respectfully prays that a writ of certi

orari issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, entered in

this proceeding on May 27, 1988.

OPINIONS BELOW

The amended opinion of the court of

appeals for the Ninth Circuit is reported

at 847 F.2d 1315, and is reprinted in the

appendix to the petition, p.4a. The order

of the court of appeals amending its prior

opinion, denying rehearing, and rejecting

the suggestion for rehearing en banc is

2

unreported and is reprinted in the

appendix, p. 4a. The superseded opinion

of the court of appeals is reported at 830

F. 2d 128, and is not reprinted in the

appendix.

The order of the United States District

Court for the Central District of

California granting partial summary

judgment in favor of the respondents as to

petitioner's claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981

is unreported and is reprinted in the

appendix, p. 77a. The memorandum and

order of the district court granting

summary judgment in favor of the respon

dents as to all claims is unreported and

is reprinted in the appendix, p. 18a. The

partial report and recommendation of the

United States magistrate is reprinted in

the appendix, p. 81a, and the second

partial report and recommendation of the

3

magistrate is reprinted in the appendix,

p. 34a.

JURISDICTION

The court of appeals entered its final

judgment and denied a timely petition for

rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en

banc on May 27, 1988. On August 23, 1988,

Justice O'Connor ordered that the time for

filing this petition for writ of cer

tiorari be extended to and including

September 24, 1988. Jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §

1254(1).

STATUTES INVOLVED

Section 1981 of 42 U.S.C. provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and

property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to

like punishment, pains, penalties,

4

taxes, licenses, and exactions of

every kind, and to no other.

Section 703(a) of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §

2000e-2(a), provides in pertinent part:

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer —

(1) to fail or refuse to hire . . .or otherwise to discriminate against

any individual with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or 2

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for

employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment oppor

tunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee,

because of such individual's race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In the summer of 1983 plaintiff

Kenneth Robinson, the petitioner in this

Court, applied for four separate jobs with

the County of Orange, California, and the

5

Orange County Superior Court. (App. 4a).1 *

As part of each application, Robinson

filled out a demographic questionnaire on

which he indicated that he is a black

male.2 (App. 6a). Each application was

denied at the initial screening phase;

Robinson was not hired for any of the four

positions. (App. 4a-5a) .

1 Robinson applied for jobs as an Administrative Analyst III, Employment

Services Representative IV, Investigator- Special Services, and Probate Examiner I. (App. 37a).

That portion of the application states: "Orange County is asking all

applicants for positions to complete this form in order to comply with United States

government equal employment opportunity

requirements. Information you provide will not be used in any wav as mart of the

testing process. This flap will not be duplicated or made available to hiring

department. Data collected is used for

statistical purposes and to measure the

County's effectiveness of recruiting efforts." (App. 6a) (emphasis in

original) . Petitioner Robinson checked

boxes indicating that he is black (not of

Hispanic origin), male, and 40 years old or older.

6

After filing an administrative charge

of discrimination with the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission and receiving

a notice of right-to-sue from the United

States Department of Justice, Robinson

filed a pro se action in the district

court, alleging that the defendants (the

County of Orange, Orange County Superior

Court, and certain County officials and

employees) had engaged in racial dis

crimination in violation of 42 U.S.C. §

1981 and Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964. Robinson made a "disparate

treatment" claim under § 1981 and Title

VII, alleging that the defendants had

intentionally discriminated against him

because of his race or color. He also

made a "disparate impact" claim under

Title VII, alleging that the defendants'

employment practices had a substantial and

unjustified adverse impact on blacks in

7

general and black males in particular.

Robinson filed, along with the complaint,

a timely demand for a jury trial.

(Compl., p. 2 0, Dkt,. Nr. 1).

The case was assigned to a magi-

strate, who issued reports recommending

that the district court grant the

defendants' motions for summary judgment

on the § 1981 claims (App. ilia) and on

the Title VII disparate treatment claims.

(App. 75a). The magistrate recommended,

however, that the court deny the defen

dants' motion for summary judgment on the

Title VII disparate impact claims. (App.

76a) .

With respect to the § 1981 and Title

VII disparate treatment claims, the

magistrate stated that Robinson's written

applications for three of the four jobs

(Administrative Analyst III, Employment

Services Representative IV, and Inves

8

tigator, Social Services) did not contain

information establishing that he possessed

the specific qualifications sought in the

County's job announcements, and that

Robinson therefore had failed to "apply"

for the jobs within the meaning of this

Court's decision in McDonnell Douglas

Coro, v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), as

interpreted by the Ninth Circuit in Tagupa

v. Board of Directors. 633 F.2d 1309 (9th

Cir. 1980). (App. 48-49a; 54-56a; 59a;

92-93a; 100-101a; 103-104a). The magistr

ate also recited the respondents' conten

tion that Robinson's application for

Probate Examiner I was rejected "because

he was not deemed to be one of the most

qualified applicants." (App. 105a).

The magistrate stated an additional

reason for recommending summary judgment

with respect to Robinson's disparate

treatment claims based on his applications

9

for Administrative Analyst III and Probate

Examiner I. Although each of Robinson's

applications included the demographic

questionnaire indicating that he is a

black male, the magistrate relied on

declarations provided by two of the

individual defendants in concluding that

those defendants were not aware of

Robinson's race when they rejected his

applications. (App. 48a; 63a). Thus,

the magistrate recommended that the

district court grant summary judgment for

the defendants on all § 1981 claims and on

all Title VII disparate treatment claims.

In separate orders, the district court

approved and adopted the magistrate's

findings, conclusions, and recommendations

in all these respects. (App. 18a, 79a).

With respect to the Title VII disparate

impact claims, the magistrate found that

Robinson had sufficiently, albeit vaguely,

10

identified three challenged employment

practices: (1) discounting education over

experience; (2) not permitting testing for

persons of a protected class who meet

minimum qualifications; and (3) using

subjective judgment in determining whether

applicants meet stated minimum qualifica

tions. (App. 67-68a). As the magistrate

also noted, the record showed that the

Orange County Superior Court employed no

black males as of April 1984. (App. 68a).

The defendants offered evidence that

the percentage of blacks employed by

Orange County was higher than the per

centage of blacks in the County's popula

tion or labor force. (App. 69a).

Robinson, on the other hand, offered

evidence that the percentage of blacks

employed by Orange County was lower than

the percentage of blacks in the combined

population of Orange County and the

11

surrounding counties. (See App. 8-9a).

The magistrate therefore concluded that

there was a "genuine issue of material

fact" as to "whether the defendants

maintained employment practices which had

an adverse impact upon black males or

black males over 40 years old," (App.

70a), and he recommended that the district

court deny defendants' motion for summary

judgment on those claims. (App. 75a).

Rejecting the magistrate's recommen

dation regarding the disparate impact

claims, the district court granted summary

judgment in favor of the defendants on

these claims as well as the disparate

treatment claims. The court stated that

the challenged employment practices were

"only vaguely described," and that

Robinson had "not offered any statistics

which show or tend to show that the

challenged employment practices dispropor

12

tionately exclude black male job ap

plicants." (App. 30a). The district

court held that Robinson "was not able to

demonstrate the existence of a orima facie

case at the summary judgment motion," and

therefore granted summary judgment in

favor of the defendants as to all claims.

(App. 32a).

On Robinson's pro se appeal, a divided

panel of the Ninth Circuit affirmed the

district court's judgment. With regard to

the § 1981 and Title VII disparate

treatment claims, the majority opinion did

not address the question whether Robinson

had adequately "applied" for the jobs, but

focused instead on the question whether

the defendants were aware of his race.

Although the majority's opinion ack

nowledged that "the credibility of the

application screeners could be a triable

issue," (App. 7a), the majority relied onII

13

the sereeners' declarations denying

knowledge of Robinson's race and held that

"no genuine issue exists as to whether the

application sereeners were aware of his

race." (Id.).

The Ninth Circuit majority also

affirmed the district court's grant of

summary judgment in favor of the defen

dants on Robinson's Title VII disparate

impact claims. Although the record showed

that the Orange County Superior Court had

no black male employees, the majority

rejected Robinson's efforts to compare the

racial composition of the defendants' work

force with the racial composition of the

population in Orange County and the

surrounding counties; the majority stated

that Robinson had failed to establish

"that these general population statistics

represent a pool of prospective applicants

14

qualified for the j obs for which he

applied." (App. 9a) •

Additionally, the majority held that

Robinson's showing that there were no

black male employees did not present a

genuine issue of material fact on his

disparate impact claims in view of

evidence that the percentage of black

female employees was slightly above the

percentage of blacks in the Orange County

population.3 (Id.). Finally, the

majority held that Robinson had failed to

establish a sufficient "prima facie case

of disparate impact on Black males"

because he did not "'identify specific

employment practices or selection cri

3 The majority opinion notes that,

"in 1984, although Blacks represented 1.2% of the Orange County population, 1.7% of the Superior Court work force was Black

and 2.7% of both the 'Professional' and

'Official/Administration' positions in the County of Orange were held by Blacks." (App. 9a).

15

teria,'" and because he did not "'show the

causal relationship between the identified

practices and the impact.'" (Id.)

(quoting Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co.,

810 F. 2d 1477, 1482 (9th Cir. 1987) (en

banc) , on remand. 827 F.2d 439, 441 (9th

Cir. 1987), cert . granted. 56 U.S.L.W.

3887 (June 28, 1988) . The majority

concluded that, "[bjecause Robinson has

not pointed to evidence creating a genuine

dispute about facts material to a prima

facie case of disparate impact, summary

judgment was appropriate on this issue."

(App. 9-10a).

Judge Pregerson dissented as to both

the disparate treatment claims and the

disparate impact claims. He first noted

that, in reviewing a grant of summary

judgment, the evidence should be viewed in

the light most favorable to the nonmoving

party, and that "Title VII is 'a remedial

16

statute to be liberally construed in favor

of the victims of discrimination,' ...

[p]articularly where, as here, a layperson

brings a Title VII action pro se . . . ."

(App. 11a) (citations omitted).

With respect to the disparate treatment

claims, the dissent found that the record

contained concrete evidence "that the

County employees who considered Robinson's

application may have known he was black"

— viz., copies of Robinson's job

applications, which had been supplied by

the defendants in discovery with the

racial information still attached. (App.

12a). "[B]y keeping this information

physically attached to other employment

information, the County runs a risk that

employees making employment decisions will

be aware of racial and other demographic

factors that might lead to discrimina

tion." (Id.). In the dissenting judge's

17

view, the credibility of the employees who

denied knowledge of Robinson's race,

coupled with the concrete evidence that

they may have known his race, presented

genuine issues of material fact sufficient

to withstand summary judgment on the

disparate treatment claims.

With respect to the disparate impact

claims, the dissent noted Robinson's

evidence "that the Orange County Superior

Court has no black male employees, and

that the overall representation of blacks

(all women) among its employees is 1.7%."

(App. 13a) (emphasis in original) . The

fact that blacks constituted only 1.2% of

Orange County's population did not

conclusively justify "the startlingly low

levels of black employment in the Orange

County Superior Court ..."; the defendants

should have been required to come forward

with "statistics concerning the actual

18

pool of applicants for the positions for

which Robinson applied." (App. 13a). The

dissenting judge also believed that the

case should be remanded to the district

court for further findings as to the

relevant labor market under this Court's

decision in Hazelwood School District v.

United States. 433 U.S. 299 (1977). (App.

14a) .

Finally, citing this Court's decisions

in Connecticut v. Teal. 457 U.S. 440

(1982), and Los Angeles Department of

Water & Power v. Manhart. 435 U.S. 702

(1978) , as well as the Fifth Circuit's

decision in Jeffries v. Harris County

Community Action Association. 615 F.2d

1025 (5th Cir. 1980), the dissent rejected

the majority's apparent conclusion that

the defendants' employment of black

females was a complete defense to Robin

son's claim of discrimination against

19

black males as a class. The dissent would

hold instead "that the evidence presented

by Robinson is sufficient to make out a

prima facie case of disparate impact on

black males." (App. 15a). Because

Robinson had raised "a genuine issue of

material fact on whether blacks and

particularly black males are proportion

ally represented in the court's work

force," in the dissent's view summary

judgment should not have been granted in

favor of the defendants on the disparate

impact claims. (App. 13a).

Robinson filed a timely petition for

rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en

banc. A majority of the original Ninth

Circuit panel voted to deny the petition

for rehearing and to reject the suggestion

of rehearing en banc. A majority of the

judges of the full court also voted to

20

reject the suggestion for rehearing en

banc. (App. 4a) .

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

THE NINTH CIRCUIT MAJORITY'S REJECTION OF

PETITIONER'S TITLE VII DISPARATE IMPACT

CLAIM OF DISCRIMINATION BASED ON RACE AND SEX IS CONTRARY TO THE DECISIONS OF THIS

COURT AND INCONSISTENT WITH THE DECISIONS

OF OTHER CIRCUITS.

The Ninth Circuit majority held in

part that Robinson's evidence of disparate

impact against black males (indeed, he

showed that the Orange County Superior

Court did not employ a single black male)

was not sufficient to withstand the defen

dants' motion for summary judgment because

blacks as a group were not statistically

underrepresented in the defendants' work

force. (App. 9a) . In effect, the court

below treated the defendants' employment

of black females as a defense to Robin

son's claims that the defendants dis

criminated against black males. As the

21

dissent observed, this holding is contrary

to the prior decisions of this Court and

it conflicts with the decisions of other

circuits.

In Connecticut v. Teal. 457 U.S. 440

(1982), this Court rejected the "bottom

line" defense in Title VII disparate

impact cases. The Court stated:

It is clear that Congress never intended to give an employer license

to discriminate against some employees on the basis of race or sex merely

because he favorably treats other members of the employees' group. We

recognized in Los Angeles Dept. of

Water & Power v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702

(1978) , that fairness to the class of

women employees as a whole could not

justify unfairness to the individual female employee because the 'statute's

focus on the individual is unambiguous. ' Id., at 708. Similarly, in

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400U.S. 542 (1971) (per curiam), we

recognized that a rule barring employment of all married women with

preschool child-ren, if not a bona fide

occupational qualification under § 703(e), violated Title VII, even though

female applicants without preschool children were hired in sufficient numbers that they constituted 75 to 80

percent of the persons employed in the position plaintiff sought.

22

457 U.S. at 455 (emphasis in original).

Thus, the majority opinion below,

insofar as it treats the employment of

black females as a justification for

discrimination against the plaintiff and

other black males, is contrary to this

Court's decisions in Teal. Manhart, and

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400

U.S. 542 (1971) (per curiam) . See also

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438

U.S. 567, 579 (1978) ("[i]t is clear

beyond cavil that the obligation imposed

by Title VII is to provide an equal

opportunity for each applicant regardless

of race, without regard to whether members

of the applicant's race are already

proportionately represented in the work

force") (emphasis in original).

The decision of the majority below

also conflicts with the decisions of other

circuits. In Jeffries v. Harris County

23

Community Action Association, 615 F.2d

1025 (5th Cir. 1980) , a black woman

brought a Title VII action charging the

defendants with discrimination in promo

tion based on both race and sex. The

Fifth Circuit affirmed the district

court's judgment against the plaintiff on

the merits of her race discrimination

claim, remanded the case for further

findings on her sex discrimination claim,

and held that that the district court had

improperly failed to address her claim of

discrimination based on both race and sex.

615 F.2d at 1032.

Noting that Title VII provides a

remedy for discrimination on the basis of

"race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin," 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) (emphasis

added), the Fifth Circuit in Jeffries

stated that Congress' use of the word

"or," and its refusal to adopt an amend-II

24

merit that would have added the word

"solely" to modify the word "sex,"

demonstrated the intent of Congress "to

prohibit employment discrimination based

on any or all of the listed characteris

tics." 615 F.2d at 1032. Moreover, "[i]n

the absence of a clear expression by

Congress that it did not intend to provide

protection against discrimination directed

especially toward black women as a class

separate and distinct from the class of

women and the class of blacks," the court

could not "condone a result which leaves

black women without a viable Title VII

remedy." Id.

Additionally, the Fifth Circuit in

Jeffries felt that recognition of the

plaintiff's race-sex claim was mandated by

this Court's decision in Phillips v.

Martin Marietta Corp., supra. and other

"sex plus" cases; just as employers may

25

not apply different standards to women

with young children, married women, or

women who are single and pregnant, so also

are employers prohibited from singling out

for discriminatory treatment a class of

women who are black. 615 F.2d at 1033-

1034. Indeed, " [t]his would be a par

ticularly illogical result, since the

'plus' factors in the former categories

are ostensibly 'neutral' factors, while

race itself is prohibited as a criterion

for employment." Id. at 1034 (footnote

omitted).

The Fifth Circuit concluded as follows:

Recognition of black females as a

distinct protected subgroup for purposes of the prima facie case and proof _ of pretext is the only way to identify and remedy discrimination directed toward black females. Therefore, we hold that when a Title VII plaintiff alleges that an employer

discriminates against black females, the fact that black males and white

females are not subject to discrimination is irrelevant and must not form

any part of the basis for a finding

26

that the employer did not discriminate

against the black female plaintiff.

615 F.2d at 1034.

The Tenth Circuit followed Jeffries in

Hicks v. Gates Rubber Co. . 833 F.2d 1406

(10th Cir. 1987) . The plaintiff in

Hicks, also a black woman, brought a Title

VII action alleging racial and sexual

harassment on the job. The Tenth Circuit,

stating that "the Jeffries ruling is

correct," held that the plaintiff was

permitted to "aggregate evidence of racial

hostility with evidence of sexual hos

tility" in pursuing a combined race-sex

discrimination claim. 833 F.2d at 1416

(footnote omitted).4 See also Chambers v.

4 The Eighth Circuit has noted but not decided this issue. In DeGraffenreid

v. General Motors Assembly Division. 558 F. 2d 480 (8th Cir. 1977), the court

reviewed a district court decision

refusing to recognize a combined race-sex claim under Title VII. The Eighth Circuit

stated that it did "not subscribe entirely

to the district court's reasoning in rejecting appellants' claims of race and

27

Omaha Girls Club, 629 F. Supp. 925, 946

n. 34 (D. Neb. 1986), aff/d. 834 F.2d 697

(8th Cir. 1987) (following Jeffries);

Graham v. Bendix Coro.. 585 F. Supp. 1036,

1047 (N.D. Ind. 1984) ("[u]nder Title VII,

the plaintiff as a black woman is protec-

ted against discrimination on the double

grounds of race and sex, and an employer

who singles out black females for less

favorable treatment does not defeat

plaintiff's case by showing that white

sex discrimination under Title VII," but it affirmed the district court's judgment on other grounds. 558 F.2d at 484.

28

females or black males are not so un

favorably treated").

II.

THIS COURT HAS GRANTED CERTIORARI IN ANOTHER CASE TO REVIEW THE PRIMA FACIE

CASE STANDARD APPLIED BY THE NINTH CIRCUIT TO DISPARATE IMPACT CLAIMS UNDER TITLE VII.

In an effort to defeat the defendants'

summary judgment motion in the district

court, Robinson presented undisputed

evidence that the Orange County Superior

Court employed no black men, and he

identified several practices that he

believed were responsible for the absence

of black male employees. (App. 67-70a).

The Ninth Circuit majority affirmed

summary judgment in favor of the defen

dants on Robinson's disparate impact

claims not only because the Superior Court

employed black women, see supra. but also

because Robinson did not present evidence

sufficient, in the majority's view, to

29

make out a prima facie case of disparate

impact discrimination.

In particular, the majority below

ruled that a plaintiff must show the

following to make out a prima facie Title

VII disparate impact case: (1) sig

nificant adverse impact against the

protected group of which the plaintiff is

a member; (2) specific identified employ

ment practices or criteria; and (3) a

causal relationship between the identified

practices and the impact. (App. 9a). In

support of this ruling, the Ninth Circuit

majority cited Atonio v. Wards Cove

Packing Co.. 810 F. 1477, 1482 (9th Cir.

1987) (en banc).

Subsequent to the decision of the

court below, this Court granted certiorari

to review the elements and application of

the Ninth Circuit's disparate impact prima

facie case standard. Atonio v. Wards Cove

30

Packing Co.. No. 87-1388, 56 U.S.L.W. 3887

(June 28, 1988), granting cert, to 827

F. 2d 439 (9th Cir. 1987). The Court,

therefore, should hold the present

petition pending the resolution of Atonio

this Term.

III.

THE NINTH CIRCUIT MAJORITY'S AFFIRMANCE OF SUMMARY JUDGMENT AGAINST PETITIONER ON HIS CLAIMS OF INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION, IN THE FACE OF CONFLICTING EVIDENCE, IS

CONTRARY TO THE DECISIONS OF THIS COURT. MOREOVER, THIS COURT HAS GRANTED CERTIORARI IN ANOTHER CASE TO REVIEW A

SUBSTANTIALLY SIMILAR QUESTION.

As the dissent points out, the record

in this case contains conflicting evidence

as to whether the Superior Court officials

who rejected Robinson's employment

applications knew his race. (App. 11-

11a). Robinson relied on copies of his

applications, which had been supplied in

discovery by the defendants from their own

files with demographic questionnaires

31

still attached, plainly stating that he

was black. (App. 12a). The officials, on

the other hand, submitted declarations

disclaiming any such knowledge. In the

dissent's view, the credibility of those

officials, coupled with the concrete

evidence provided by the employment

applications and the inferences that could

reasonably be drawn from that evidence,

presented genuine issues of fact for

trial. (App. 12-13a). The majority

below, however, affirmed summary judgment

for the defendants on Robinson's disparate

treatment claims under Title VII and 42

U.s.c. § 1981. (App. 7-8a).

In a case involving claims of inten

tional discrimination, the ultimate issue

is the state of mind or intent of

individuals. This Court has declared in

numerous cases that a question regarding

the state of mind of an individual "does

32

not readily lend itself to summary

disposition," Hutchinson v. Proxmire, 443

U.S. Ill, 120 n.9 (1979); that "[sjummary

judgments • . . are not appropriate 'when

motive and intent play leading roles,'"

White Motor Co. v. United States, 372 U.S.

253, 259 (1963); and that "summary

procedures should be used sparingly . . .

where motive and intent play leading

roles, the proof is largely in the hands

of the alleged [wrongdoers], and hostile

witnesses thicken the plot." Poller v.

Columbia Broadcasting System. Inc., 368

U.S. 464, 473 (1962) (footnote omitted).

The Court has granted certiorari to

review a substantially similar question in

Harbison-Walker Refractories v. Brieck.

No. 87-271, 56 U.S.L.W. 3647 (March 21,

1988), a disparate treatment case brought

under the Age Discrimination in Employment

Act of 1967, 29 U.S.C. § 621 et seq.

33

Harbison-Walker. like the present case,

concerns the proper standards for granting

summary judgment where the plaintiff has

requested a jury trial on claims of

intentional discrimination.5 If the Court

does not grant the present petition, it

should hold the petition pending the

resolution of Harbison-Walker this Term.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, certiorari

should be granted to review the judgment

and opinion of the Ninth Circuit.

Alternatively, the Court should hold this

5 The petitioner's brief in Harbison

states the question presented there as

follows: "Whether a plaintiff who alleges

intentional discrimination can survive

summary judgment merely by questioning his

employer's business judgment, without

presenting any evidence, direct or

indirect, that his employer's judgment was

in fact motivated by an intent to

discriminate." Brief for Petitioner, at

i, Harbison-Walker Refactories v. Brieck, No. 87-271.

34

petition pending the resolution of Wards

Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, No. 87-1388,

and Harbison-Walker Refractories v.

Brieck. No. 87-271.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIU^/L. CHAMBERS CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON RONALD L. ELLIS

JUDITH REEDNAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

PATRICK O. PATTERSON, JR.* BILL LANN LEE

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street

Suite 800Los Angeles, CA 90014

Counsel for Petitioner

*Counsel of Record

September 1988

APPENDIX

FOR PUBLICATION

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

Kenneth Robinson,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

M ichael Adams, D ianne R, Coe,

Georgia M cCarthy, M artin

M oshier, Lura Scovil, Joan

W ilson, County of Orange,

Orange County Superior Court

and L.B. Utter,

D efen d an ts-Appellees.

No. 85-6533

D.C, No,

CV 83-6S23-IH

ORDER AND

AMENDED

OPINION

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Central District of California

Irving Hill, District Judge, Presiding

Argued and Submitted

April 6, 1987— Pasadena, California

Filed October 13, 1987

Amended May 27, 1988

Before: J. Clifford Wallace, Mary M. Schroeder and

Harry Pregerson, Circuit Judges.

„ Opinion by Judge Wallace; Dissent by Judge Pregerson

SUMMARY

Employment Discrimination

Appeal from a grant of summary judgment. Affirmed.

2a

Appellant Robinson applied for four positions with the

appellee County of Orange. Each application was denied at

the screening phase. Robinson alleged a violation of Title VII,

and the EEOC issued a right-to-sue letter. Robinson filed this

action in district court alleging violations of section 1981 and

Title VII. The district court entered summary judgment for

all defendants.

[1J Under Title VII or under section 1981, a plaintiff must

prove intentional discrimination to make out a discrimina

tion claim using a disparate treatment theory. An employer

cannot intentionally discriminate against a job applicant

based on race unless the employer knows the applicant’s race.

[2] Robinson has not produced sufficient evidence on the

question of the knowledge by Orange County or the employ

ees of his race for a jury to return a verdict in his favor. [3] A

plaintiff establishes a prima facie case of employment dis

crimination using a disparate impact theory when he or she

shows that a business practice, neutral on its face, had a sub

stantial, adverse impact on some group protected by Title

VII. [4] Robinson fails to establish that general population

statistics represent a pool of prospective applicants qualified

for the jobs for which he applied.

The dissent argues that the district court erred in granting

summary judgment on the disparate treatment claim because

there is a genuine issue of material fact whether the Orange

County employees reviewing Robinson’s application actually

knew he was black and that he has raised a genuine issue of

material fact on whether blacks and particularly black males

are proportionally represented in the court’s work force.

COUNSEL

Kenneth Robinson, Fullerton, California, in pro per, for the

plaintiff-appellant.

3a

Lynn Bouslog, Santa Ana, California, for the defendants-

appellees.

ORDER

The majority opinion, published at 830 F.2d 128, is

amended as follows. The language beginning with the sen

tence starting on line 4 in the right-hand column of page 131

to the sentence ending at line 27 before the citation is deleted

and the following is substituted:

Robinson, however, has presented insufficient evi

dence to suggest this is the case here. His showing

that Black males are statistically underrepresented

cannot, standing alone, show a racially discrimina

tory impact on Blacks as a whole. To make out a

prima facie case of disparate impact on Black males,

Robinson would also have to “identify specific

employment practices or selection criteria” and

“show the causal relationship between the identified

practices and the impact.”

The dissenting opinion, published at 830 F.2d 131, is

amended as follows:

The heading “A. Statistical Background of Blacks and

Black Males” in the left-hand column of page 133 is deleted.

The heading “B. Black Males as a Protected Class” in the

left-hand column of page 134 is deleted.

The sentence “I flatly . . . Title VII.” in the second full para

graph in the left-hand column of page 134 is deleted.

The sentence “I would . . . Title VII.” and the following

citation in the right-hand column of page 134 is deleted and

4a

the following is substituted: “I would hold that the evidence

presented by Robinson is sufficient to make out a prima facie

case of disparate impact on black males.”

The panel as constituted above has voted to deny the peti

tion for rehearing. A majority of the panel has voted to reject

the suggestion for rehearing en banc.

The full court has been advised of the suggestion for rehear

ing en banc. An active judge called for an en banc vote and a

majority of the judges of the court has voted to reject the sug

gestion for rehearing en banc. Fed. R. App. P. 35(b).

The petition for rehearing is denied, and the suggestion for

rehearing en banc is rejected.

„ OPINION

WALLACE, Circuit Judge:

Robinson appeals pro se the district court’s summary judg

ment against him on his employment discrimination claims.

He contends (1) that he need not prove that defendants had

knowledge of his race to sustain a claim of racial discrimina

tion under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 or Title. VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e to 2000e-17, (2) that a genu

ine issue exists whether the defendants were aware of his race,

and (3) that he established a prima facie case of disparate

impact. We have jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291,

and we affirm.

I

In July and August 1983, Robinson applied for four posi

tions with the County of Orange and the Orange County

Superior Court (Orange County). Orange County denied each

5a

application at the initial screening phase. Robinson tiled a

charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion, alleging a violation of Title VII, and the Commission

issued a right-to-sue letter. Robinson filed this action in dis

trict court against Orange County and several of its employ

ees (the employees) alleging violations of section 1981 and

Title VII. The district court entered summary judgment for

all defendants. We review the summary judgment de novo.

L o jek v. T hom as, 716 F.2d 675, 677 (9th Cir. 1983). We

address first Robinson’s disparate treatment claim, and then

his claim of disparate impact.

II

[1] Under Title VII or under section 1981, a plaintiff must

prove intentional discrimination to make out a discrimina

tion claim using a disparate treatment theory. G a y v. W a iters ’

and D a iry L u n c h m e n ’s Union, 694 F.2d 531, 537 (9th Cir.

1982) (G a y). An employer cannot intentionally discriminate

against a job applicant based on race unless the employer

knows the applicant’s race. Robinson contends, however,

that he may discharge his prima facie burden of production

by offering proof of the four elements articulated in

M cD on n ell D ou glas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), and

that M cD o n n ell D ouglas merely requires proof that he

belongs to a racial minority. S ee id. at 802; G ay, 694 F.2d at

* 538 & n.5.

The M c D o n n ell D ouglas test, however, “was never

intended to be rigid, mechanized, or ritualistic. Rather, it is

merely a sensible, orderly way to evaluate the evidence . . . on

the critical question of discrimination.” F urn co Construction

Corp. v. W aters, 438 U.S. 567, 577 (1978). The M cD o n n ell

- D ouglas test defines one method of proving a prima facie case

of discrimination — proof from which a trier of fact can rea

sonably infer intentional discrimination. S e e G ay, 694 F.2d

at 538. But the M cD o n n ell D ouglas elements would not ratio

nally create this inference if, as here, a plaintiff offers proof

6a

that he is Black, but there is no showing by direct or indirect

evidence that the decision-maker knew this fact.

[2] Even accepting this requirement, however, Robinson

contends that he can survive a motion for summary judgment

because some evidence in the record suggests that Orange

County and the employees could have discovered he is Black.

On all four ofRobinson’s applications, he checked a box indi

cating his race. Nevertheless, “there is no issue for trial unless

there is sufficient evidence favoring the nonmoving party for

a jury to return a verdict for that party. If the evidence is

merely colorable, or is not significantly probative, summary

judgment may be granted.” A nd erson v. L ib erty L o b b y , Inc.,

106 S. Ct. 2505, 251 1 (1986) (citations omitted) (L ib erty

L o b b y). We do not believe that Robinson has produced suffi

cient evidence on the question of the knowledge by Orange

County or the employees of his race for a jury to return a ver

dict in his favor.

The following paragraph appeared at the top of that portion

of the application which contained racial and other demo

graphic information.

Orange County is asking all applicants for posi

tions to complete tjiis form in order to comply with

United States government equal employment

opportunity requirements. In form ation yo u provide

will not b e used in a ny wav as part o f the testing

process. This flap will not be duplicated or made

available to hiring department, [sic] Data collected

is used for statistical purposes and to measure the

County’s effectiveness of recruiting efforts.

j*-

(Emphasis in original.) Furthermore, this section of the appli

cation appeared on a flap that is described in the record vari

ously as a “tear apart attachment,” “inside detachable tab,”

“tear-off form,” and “separate sheet [that was] detached for

internal record keeping purposes.” The record suggests that

7a

either the flap was photocopied as part of the original applica

tion and then torn off before the application was sent to the

application screener, or a copy of the application which did

not show the flap was sent to the application screener, or the

flap was folded so that it could not be viewed by the applica

tion screener. Since the data on the flap did not contain signif

icant information for statistical purposes, such as the job

applied for and the date of application, the employer must

have retained a full copy of the application in its records. The

key question here is whether the screeners knew the appli

cant’s race. Orange County submitted affidavits from the

application screeners who had rejected Robinson’s job appli

cations. All of these screeners declared that they were

unaware of Robinson’s race when they reviewed and rejected

his applications. Although the credibility of the application

screeners could be a triable issue, Robinson has produced no

evidence that places their credibility in doubt. “[Njeither a

desire to cross-examine an affiant nor an unspecified hope of

undermining his or her credibility suffices to avert summary

judgment.” N ation al Union F ire Insurance C o . v. A rgon a ut

Insurance C o ., 70! F.2d 95, 97 (9th Cir. 1983).

In light of this record, we conclude that there was no genu

ine dispute as to whether the application screeners were

aware of Robinson’s race. The applications stated that the

demographic information would not be considered as part of

the hiring process, and the information was contained on a

flap purposefully designed so that it would not be seen by the

application screeners. Significantly, Robinson does not point

to any evidence tending to show that this procedure resulted

in the disclosure of racial information to application screen

ers in his or any other case. The only evidence in the record,

the affidavits of the application screeners, unequivocally sug

gests that the procedure worked. Robinson’s evidence on this

issue is “merely colorable” and is not “significantly

probative.” L ib erty L o b b y , 106 S. Ct. at 2511. Therefore, we

hold that no genuine issue exists as to whether the application

screeners were aware of his race. Summary judgment was

8a

appropriate on Robinson’s intentional discrimination

theory.1

III

[3] A plaintiff establishes a prima facie case of employment

discrimination using a disparate impact theory when he or

she shows that a business practice, neutral on its face, had a

substantial, adverse impact on some group protected by Title

VII. G ay, 694 F.2d at 537. Such proof is usually accomplished

by statistical evidence showing “that an employment practice

selects members of a protected class in a proportion smaller

than their percentage in the pool of actual applicants.” M o o r e

v. H u g h es H elicopters, Inc., 708 F.2d 475,482 (9th Cir. 1983).

(4] Robinson contends he established a prima facie case of

discriminatory impact by citing statistics which allegedly

show that the percentage of Blacks in Orange County and in

‘The dissent correctly points out that the record before us includes copies

o f Robinson’s four applications still containing the detachable tab on which

Robinson’s race is noted. There is nothing in the record to suggest that

Uiese copies are in fact the copies o f the applications that the application

screeners actually saw. The form itself, as we observed above, indicates that

this portion o f the application would not be “ duplicated” or otherwise

made available to the hiring department. The most reasonable inference

from this statement is that the County generally keeps the original applica

tions on file, and sends a duplicate copy to the screeners. Robinson has

presented nothing more than his conclusory assertion, which he admits is

an assumption, that the copy o f the application form he received through

the discovery process is the same as what was sent to the application screen

ers. The screeners all declared that they were unaware o f Robinson’s

race— i.e., that they did not see the tab containing his race identification.

In the absence o f some evidence that the copies o f the form Robinson pro

cured through discovery are the same as those submitted to the application

screeners, we are unable to believe that a jury could decide, based on the

preponderance o f the evidence, that Robinson’s copy o f the application

was the same as what the screeners saw and therefore that the screeners

were aware o f his race. See Liberty Lobby, 106 S. Ct. at 2510-12. Thus, in

light o f the screener’s testimony, there is no triable issue o f fact.

9a

surrounding counties is higher than the percentage of Blacks

employed by Orange County. Nevertheless, Robinson fails to

establish that these general population statistics represent a

pool of prospective applicants qualified for the jobs for which

he applied. We have consistently rejected the usefulness of

general population statistics as a proxy for the pool of poten

tial applicants where the employer sought applicants for posi

tions requiring special skills. S e e id. at 482-83.

In any case, the most probative statistics in the record tend

to show an absence of disparate impact: in 1984, although

Blacks represented 1.2% of the Orange County population,

1.7% of the Superior Court work force was Black and 2.7% of

both the “Professional” and “Official/Administration” posi

tions in the County of Orange were held by Blacks. Robinson

argues, however, that his disparate impact theory can survive

a motion for summary judgment because he has presented

evidence that the Orange County Superior Court did not have

any Black m a le employees. Obviously, since Blacks are not

statistically underrepresented in the Orange County Superior

Court’s work force, Robinson cannot plausibly maintain that

the Court’s hiring practices have- a racially discriminatory

impact on Blacks as a whole. Conceivably, the absence of any

Black m a le employees could result from racial stereotyping or

have some other link to racial discrimination. Robinson,

however, has presented insufficient evidence to suggest this is

the case here. His showing that Black males are statistically

underrepresented cannot, standing alone, show a racially dis

criminatory impact on Blacks as a whole. To make out a

prima facie case of disparate impact on Black males, Robin

son would also have to “identify specific employment prac

tices or selection criteria” and “show the causal relationship

between the identified practices and the impact.” A to n io v.

W ards C o v e Packing C o ., 8lOF.2d 1477, 1482 (9th Cir. 1987)

(en banc). This, we conclude, he has not done to the degree

necessary to survive a motion for summary judgment.

Because Robinson has not pointed to evidence creating a

genuine dispute about facts material to a prima facie case of

10a

disparate impact, summary judgment was appropriate on this

issue.

AFFIRMED.

PREGERSON, J„ dissenting

Kenneth Robinson appeals pro se from the district court’s

grant of summary judgment in favor of defendants. In the

summer of 1983, Robinson applied for four separate jobs

with the Orange County Superior Court. As part of the job

application, Robinson filled out a demographic questionnaire

in which he indicated that he is black. This questionnaire is

a “tear-off attachment” to the job application and states at the

top that the information provided on it will be used for statis

tical purposes only. Robinson was not hired for any of the

four positions, and he brought this suit alleging that he was

denied employment with the Orange County Superior Court

based on his race. The magistrate who first heard the case rec

ommended that the district court grant summary judgment

for defendants on the Title VII “disparate treatment” claim

but deny summary judgment on the “disparate impact”

claim. The district court partially accepted this recommenda

tion, granting summary judgment for defendants on both

claims.

We review de novo district court orders granting summary

judgment. Barring v. K incheloe, 783 F.2d 874, 876 (9th Cir.

1986). Our review is governed by the same standard used by

the district court under Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c). Id. We must

determine, viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to

the nonmoving party, whether there are any genuine issues of

material fact and whether the district court correctly applied

the relevant substantive law. A sh ton v. C ory, 780 F.2d 816,

818 (9th Cir. 1986).

11a

Title VII is “a remedial statute to be liberally construed in

favor of the victims of discrimination.” M a h r o o m v. H ook ,

563 F.2d 1369, 1375 (9th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 436 U.S.

904 (1978). Particularly where, as here, a layperson brings a

Title VII action pro se, a liberal construction of the statute’s

technical requirements is appropriate. R ice v. H a m ilto n A ir

F orce B a se C o m m issa ry, 720 F.2d 1082, 1084 (9th Cir. 1983).

I. D isparate T reatm ent

as the majority states, under Title VII or section 1981 a

plaintiff must establish intentional discrimination to show

disparate treatment. I agree with the majority that, notwith

standing the literal language of M c D o n n ell D ouglas, a finding

of intentional discrimination logically requires a showing

that defendants knew plaintiff’s race. In this case, then, to

pursue a claim of disparate treatment, Robinson must prove

that Orange County Superior Court employees knew he was

black when they considered his applications for employment.

I would hold that the district court erred in granting summary

judgment on the disparate treatment claim because there is a

genuine issue of material fact whether the Orange County

employees reviewing Robinson’s application actually knew

he was black.

In support of its conclusion that there is no genuine factual

issue on this point, the majority cites (1) the language at the

top of the demographic questionnaire attached to the employ

ment application stating that racial and other information

would not be considered in the employment decision, (2) the

fact that the questionnaire appeared on a detachable flap that

was part of the application form, and (3) affidavit testimony

by County employees who reviewed Robinson’s applications

indicating that when they decided not to hire Robinson they

were unaware of his race.

The majority neglects to mention the evidence Robinson

provided to counter the evidence provided by the County. In

12a

his Excerpts of Record, Robinson provided copies of his

employment applications received from the County via the

discovery process. On the pages in the Excerpt marked 141,

150, 163, and 279, Robinson’s applications are reproduced.

In each case, the demographic questionnaire, complete with

Robinson’s “x” indicating that he is black, is still attached to

the application. In my view, this evidence indicates that the

County employees who considered Robinson’s application

may have known he was black.

The evidence provided by the County does not undermine

the probity of the raw fact that Robinson’s racial information

was still attached to his job application. The first two items

cited by the majority are of negligible value for determining

what the reviewing employees actually knew. The language at

the top of the questionnaire is not determinative of how

applications were in fact processed. Similarly, the fact that

the applicant’s racial information was provided on a detach

able form indicates little about the County’s treatment of race

in the job application process. If the County had an entirely

separate demographic questionnaire used for gathering statis-

► tics, it might demonstrate the County’s desire to ensure that

employees reviewing the applications would be ignorant of

each applicant’s race. But by keeping this information physi

cally attached to other employment information, the County

runs a risk that employees making employment decisions will

be aware of racial and other demographic factors that might

lead to discrimination.

The County employees’ affidavits indicating that they were

unaware of Robinson’s race is the only viable evidence the

County has provided to dispute Robinson’s allegation that

the employees knew of his race. As the majority recognizes,

the credibility of these employees is a matter for the trier of

fact. Although the credibility issue alone probably should not

defeat defendants’ summary judgment motion, the credibil

ity question coupled with Robinson’s concrete evidence that

the employees may have known of his race is sufficient to

13a

allow his disparate treatment claim to withstand summary

judgment.

II. D isparate Im pact

Robinson also brought a Title VII claim under the dispa

rate impact theory. The district court rejected the magis

trate’s recommendation that defendants’ summary judgment

motion on this claim be rejected. I would reverse the district

court’s grant of summary judgment on this issue.

Under a disparate impact approach, an employee must

show that facially neutral employment practices have a

“significantly discriminatory” impact upon a group protected

by Title VII. C onnecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 446 (1982).

The starting point for disparate impact analysis is identifying

the appropriate candidate pool and its racial makeup. M o o r e

v. H u gh es H elicopters, Inc., 708 F.2d 475, 482 (9th Cir. 1983).

Generally, the most appropriate statistical base is the actual

pool of applicants. Id.

Robinson has shown that the Orange County Superior

Court has no black male employees, and that the overall rep

resentation of blacks (all women) among its employees is

1.7%. The majority states that there is no statistical support

for Robinson’s assertion that blacks are underrepresented in

the court’s work force. To the contrary, I believe that Robin-

sop has raised a genuine issue of material fact on whether

blacks and particularly black males are proportionally repre

sented in the court’s work force.

Defendants maintain that their 1.7% rate of black employ

ment is more than sufficient, in light of the fact that blacks

constitute only 1.2% of Orange County’s population. The

County has proferred no justification for its reliance on gen

eral population statistics rather than on statistics concerning

the actual pool of applicants for the positions for which Rob

inson applied. Given the startlingly low levels of black

employment in the Orange County Superior Court, I would

hold that the absence of statistics about the candidate pool by

itself justifies reversing the grant of summary judgment tor

defendants.

Even assuming that general population statistics are appro

priate, it is not at all clear under H a z e lw o o d S ch o o l D ist. v.

U nited S tates, 433 U.S. 299, 313 (1977), that the Orange

County population is the “relevant labor market” required

for statistical comparisons in disparate impact cases. Orange

County is not an isolated community. Although the United

States census bureau identifies Orange County as a Standard

Metropolitan Statistical Area, the bureau also identifies

Orange County as part of the Los Angeles-Long Beach-

Anaheim standard consolidated statistical area. Being part of

the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area, Orange County

presumably draws its work force from a larger population

pool than the County alone. The evidence adduced thus far

supports this presumption. For example, Orange County

advertised the positions for which Robinson applied in the

Los Angeles Times and the Orange County Register, both of

which are widely circulated throughout the greater Los Ange

les area.

I would hold, in keeping with H a z e lw o o d , that this case

should go back to the district court “for further findings as to

the relevant labor market.” Id.

Robinson contends that even if there were factual support

for defendants’ argument that b la ck s are proportionately rep

resented in the court’s work force, the evidence nonetheless

demonstrates disparate impact on b la ck m ales . The Supreme

Court stated in C o n n ecticu t v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 451, 455

(1982):

Title VII strives to achieve equality of opportunity

by rooting out “artificial, arbitrary, and unneces

sary” employer-created barriers to professional

__________ _____ 14a__________________

15a

development that have a discriminatory impact

upon individuals.

It is clear that Congress never intended to give an

employer license to discriminate against some

employees on the basis of race or sex merely because

he favorably treats other members of the employees’

group. We recognized in L o s A n g eles D ept, o f W a ter

- & P ow er v. M anhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978), that fair

ness to the class of women employees as a whole

could not justify unfairness to the individual female

employee because the “statute’s focus on the indi

vidual is unambiguous.” Id. at 1375. . . .

The stark fact is that the Orange County Superior Court

does not employ a single black male. This is strong evidence

that defendants have discriminated against black males by

creating an artificial barrier to their professional develop

ment, thereby frustrating Title VII’s goals of achieving equal

ity of opportunity. Like the behavior in M anhart, the Orange

County Superior Court’s failure to employ a single black male

blatantly disregards the rights of the individual recognized

and protected in Title VII. I would hold that the evidence

presented by Robinson is sufficient to make out a prima facie

case of disparate impact on black males. Cf. Jefferies v. H arris

C ou n ty C o m m u n ity A ction A s s ’n, 614 F.2d 1025, 1032-35

(9th Cir. 1980) (black females are a protected class under

Title VII). Accordingly, I dissent from the majority’s view to

the contrary.

16a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

No. CV 83-6823-IH(Me)

Filed October 31, 1985

KENNETH ROBINSON,

Plaintiff,

vs.

MICHAEL ADAMS, et al.,

Defendants

FINAL JUDGMENT

Pursuant to a document entitled

"Memorandum and Order" filed this date

and the Order appearing at the end

thereof, IT IS ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND

DECREED AS FOLLOWS:

1• Plaintiff shall take nothing by

his action against any of the Defendants

named herein. The Defendants and each of

them shall have judgment against the

17a

Plaintiff with costs of $ _______.

2. The Clerk shall transmit a copy

of the said "Memorandum and Order" and

this judgment to all counsel of record

and to Magistrate McMahon.

DATED: October 31, 1985.

________s/s_____________

IRVING HILL, Judge United States District Judge

18a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

No. CV 83-6823—IH(Me)

Filed October 31, 1985

KENNETH ROBINSON,

Plaintiff,

vs.

MICHAEL ADAMS, DIANNE R. COE, GEORGIA

MCCARTHY, MARTIN MOSHIER, LURA SCOVIL,

JOAN WILSON, BEN AVILLAR, MARIA

BASTANCHURY, COUNTY OF ORANGE, A

MUNICIPAL CALIFORNIA CORPORATION,

SUPERIOR COURT OF ORANGE, AND L. B.

UTTER,

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

The pro se plaintiff has filed an

employment discrimination complaint

alleging that the defendants discrimi

nated against the plaintiff by failing to

hire the plaintiff for certain jobs with

the County of Orange because of the

plaintiff's race. The court has previ-

19a

ously granted partial summary judgment

against the plaintiff in favor of the

defendants on all of the plaintiff's

claims asserted under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

(See Partial Report and Recommendation of

United States Magistrate, filed February

14, 1985.) The defendants have now moved

for summary judgment on all of the

plaintiff's claims asserted under Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (42

U.S.C. §200e[sic]-2000e-17.)

This court has now received the

Second Partial Report and Recommendation

of United States Magistrate, filed August

13, 1985. In that Second Partial Report

and Recommendation, the Magistrate

recommends that the court:

(1) Grant partial summary judgment

for the defendants dismissing

all of the plaintiff's Title

VII disparate treatment claims

20a

as against all defendants;

(2) Deny summary judgment for the

defendants on the plaintiff's

disparate impact claims;

(3) Dismiss all punitive damage

claims as against all defen

dants ;

(4) Dismiss all back pay claims as

against all defendants other

than the defendant County of

Orange; and

5) Dismiss the complaint entirely

as against defendants Bas-

tanchury and Avillar.

The Magistrate has also recommended that

this action proceed to trial as to the

plaintiff's Title VII disparate impact

claims seeking back pay as against

defendant County of Orange and injunctive

relief as against all defendants other

than Bastanchury and Avillar.

21a

The court has reviewed the com-

plaint, all of the records and files

herein, the Second Partial Report and

Recommendation of United States Magis

trate, and the Plaintiff's Objections to

the Report and Recommendation. The court

approves and adopts the findings,

conclusions, and recommendations of the

Magistrate in the Second Partial Report

and Recommendation insofar as they relate

to the recommendations numbered (1), (3),

(4), and (5), above. The court, however,

does not adopt the Magistrate's recommen

dation regarding the plaintiff's dis

parate impact claims. The court finds

that the plaintiff has not presented

evidence sufficient to demonstrate the

existence of a viable Title VII disparate

impact claim. The court, therefore,

grants summary judgment for the defen

dants and against the plaintiff on the

22a

Title VII disparate impact claim.

The Magistrate has, in his Second

Partial Report and Recommendation,

outlined the applicable Title VII

disparate impact law and its application

to this particular action. The court

adopts the Magistrate's analysis with

some modifications. (Additions are

indicated by passages set off in brackets

and omissions are set off by ellipsis.)

H. Disparate Impact

A plaintiff seeking to es

tablish a prima facie case of

employment discrimination on a

disparate impact theory must show

that a facially neutral employment

practice had a significantly

discriminatory impact. Once that

showing has been made by the

plaintiff, the employer must

demonstrate that the challenged

23a

employment practice has a manifest

relationship to the employment in

question in order to avoid a finding

of discrimination. If the employer

demonstrates that the challenged

employment practice has a manifest

relationship to the employment, a

plaintiff may still prevail by

showing that the employer was using

the challenged practice as a mere

pretext for discrimination.

Connecticut v. Teal. 457 U.S. 440,

446-447, 102 S.Ct. 2525, 73 L.Ed.2d

130 (1982) discussing Griggs v. Duke

Power Company. 401 U.S. 424, 91

S.Ct. 849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971).

Of necessity, disparate impact

cases rely heavily upon statistics.

Typically, the plaintiff identifies

a particular employment practice,

e.g., a requirement that an appli-

24a

cant seeking a particular position

possess a high school diploma or

pass a certain test (See Griggs.

supra) or a requirement that an

applicant be of a certain height or

weight. (See Dothard v. Rawlinson.

433 U.S. 321, 97 S.Ct. 2720, 53

L.Ed.2d 786 (1977).) The plaintiff

then attempts to show through a

statistical analysis that the

facially neutral practice has the

effect of eliminating a dispropor

tionate share of applicants of a

protected class. Thus, in Dothard.

supra. Alabama's requirement that

prison guards be at least 5'2" and

weigh at least 120 pounds excluded

over 41 percent of the female

population but less than 1 percent

of the male population. This

statistical evidence was held to

25a

constitute a prima facie case of sex

discrimination. Id., pages 330-

331.

I* The Plaintiff's Applications— Disparate Impact

The plaintiff has not clearly-

identified any particular employment

practice of the defendant County of

Orange which had an adverse impact

upon members of his protected class,

black males or black males over age

40. The plaintiff's points and

authorities attempt to identify

certain practices including "(1)

discounting education over expe

rience; (2) the underrepresentation

of blacks in their workforce; and

(3) not permitting testing for those

persons of a protected class who

meet minimum qualifications".

(Plaintiff's Answer to Defendants'

Motion, etc., filed May 21, 1985,

26a

pages 23-24.) In oral argument, the

plaintiff identified [an additional]

. . . challenged employment practice

. . . the use of subjective judgment

by persons who screen applications

to determine if a given applicant

meets minimum stated qualifications.

[See Transcript of June 4, 1985, of

Oral Argument on Summary Judgment

Motion, pages 28-29.]

At least one of these alleged

"employment practices" is not a

practice at all in the sense that

the term is used in Griggs, supra.

Underrepresentation of blacks is a

possible result of an employment

practice, not an employment practice

itself. The plaintiff has only

vaguely identified the parameters of

the other three challenged employ

ment practices.

27a

The plaintiff has offered

virtually no statistical evidence

designed to show that the use of the

identified employment practices

adversely affect black males or

black males over age 40. Thus, the

plaintiff has not presented any

statistical evidence showing or

tending to show that a challenged

employment practice has a dispropor

tionate impact upon black male job

applicants. The only vaguely

pertinent statistic which the

plaintiff has offered is the fact

that the Orange County Superior

Court employed no black males as of

April, 1984. (Plaintiff's Answer to

Defendants' Motion, etc., filed May

21, 1985, Exhibit 11, p. 247.) This

statistic does not, in and of

itself, demonstrate that an iden-

28a

tified employment practice dis

criminates against black males.

(Second Partial Report and Recommendation

of United States Magistrate, filed August

13, 1985, page 15, line 25, through page

18, line 2.)

Pursuant to Rule 56(c), F.R.Civ.P.,

a court shall grant summary judgment "if

the pleadings, depositions, answers to

interrogatories, and admissions on file,

together with the affidavits, if any,

show that there is no genuine issue as to

any material fact and that the moving