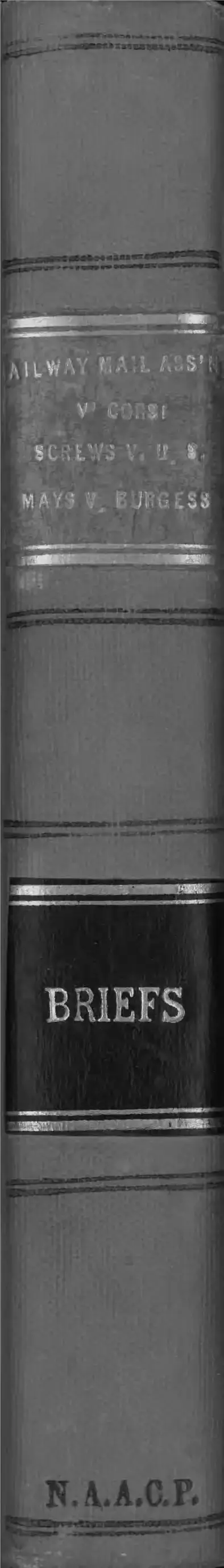

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi; Screws v. U.S.; Mays v. Burgess

Public Court Documents

January 6, 1944 - December 31, 1944

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Railway Mail Association v. Corsi; Screws v. U.S.; Mays v. Burgess, 1944. f3fc6178-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/60df7a79-082c-4680-bebb-595dfbb5acd6/railway-mail-association-v-corsi-screws-v-us-mays-v-burgess. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

' '

Supreme Court

Of the State of New York

A ppellate D ivision— T hird D epartment

B ailw ay M ail A ssociation,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

against

E dward S. Corsi, as Industrial

Commissioner of the State of

New York, and N athaniel L.

G oldstein, as Attorney Gen

eral of the State of New York,

Defendants-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE.

Arnicas Curiae.

The N. A. A. C. P. Legal Defense & Educa

tional Fund, Inc., is submitting a brief herein as

amicus curiae because of its interest in the ques

tion raised in this case. The N. A. A. C. P. Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., is an organi

zation devoted to the furtherance and protection

of the civil rights guaranteed by the Constitution

of the United States. For many years it has sup

ported individuals and groups whose basic rights

were threatened or invaded. Believing that this

case presents an issue of importance to the Negro

race generally, and to all persons interested in

the protection of civil rights, we beg leave to sub

mit the following brief discussion:

2

That the Railway Mail Association is a “ labor

organization” within the definition of the Civil

Rights Law, section 43, has been conclusively

established in the brief of the Attorney General

of the State of New York. In addition to the au

thorities and sources therein cited, we wish to call

attention to the following works:

In Patterns of Negro Segregation, by Professor

Charles S. Johnson, published in 1943 by Harper

and Brothers under a grant in aid by the Carnegie

Corporation of New York, it is stated:

“ Although there are isolated exceptions and

occasional changes in practice, existing labor

unions fall into a broad classification by racial

policy as follows: (1) Labor unions which

exclude all Negroes by special clauses in their

constitutions or rituals: . . . railway mail

clerks” (p. 98; italics supplied).

In an article in the June, 1943, issue of The

Journal of Political Economy, Herbert R. North-

rup, whose book on the Negro and American labor

unions is now in press, Harper and Brothers pub

lishers, says:

“ At least 15 American trade unions spe

cifically exclude Negroes from membership by

explicit provisions in either their constitutions

or rituals. Of these, six . . are of no great

importance in barring Negroes from jobs,

since none of them has a membership exceed

ing 3,000. Quite different, however, is the

effect of the remaining 9 exclusionist unions,

for they include some of the larger and more

influential organisations in the American

labor movement, namely: . . . the Railway

Mail Association” (pp. 206 and 207; italics

supplied).

3

It is clear from the material cited in the Attor

ney General’s brief and from the above passages

that the plaintiff-respondent is, in the full sense

of the term, a “ labor organization” within the

definition in section 43 of the Civil Eights Law.

That the Labor Law provisions are inapplicable

to the present action is clear from the history of

the Civil Rights Law, section 43. Furthermore,

the latter act contains within itself a definition of

a “ labor organization” . The statute states that

“ as used in this section ( (meaning section 43)), the

term Tabor organization’ means any organization

which exists and is constituted for the purpose, in

whole or in part, of collective bargaining, or of

dealing with employers concerning grievances,

terms or conditions of employment, or of other

mutual aid or protection” . By its very terms the

statute excludes the incorporation by reference of

a definition of a “ labor organization” from an

other statute on the basis of the rule of statutory

interpretation relating to legislative acts construed

to be in pari materia. To permit the plaintiff-re

spondent to get out “ from under” section 43 of

the Civil Rights Law by the argument that it is

not a “ labor organization” , is to open the door

to a nullification of the statute in practice.

The question of the constitutionality of section

43 of the Civil Rights Law has been adequately

covered by the brief of the Attorney General.

In view of the public policy on which the statute

is based, it is respectfully submitted that Mr. Jus

tice M urray committed legal error when he gave

to the section such narrow construction as to ex

clude from its coverage the Railway Mail Associa

tion. The practices of the Association would be

indefensible at any time, but especially are they

4

so at a time when our country needs every ounce

of manpower in order to defeat the Nazi and

Fascist system, which has as one of its chief tenets

a belief in the superiority of one race over an

other. The exclusion of Negro workers from a

labor organization keeps from jobs men and

women whose energy and industry are essential

to national defense. The Railway Mail Associa

tion, by its policy of exclusion of Negroes solely

because of their color or race, is committing an

act which is against the law, as well as an act

which outrages the basic principles of the demo

cratic pattern of life.

W herefore, it is subm itted that the order and

judgm ent below should be reversed and the com

plaint dism issed.

The City of New York, January 6, 1944.

Respectfully submitted,

E dward R. D udley,

Attorney for N. A. A. C. P. Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

New York, New York.

T hurgood M arshall,

Baltimore, Maryland.

M ilton R. K onvitz,

Newark, New Jersey.

W illiam H . H astie,

Washington, D. C.

L eon A. R ansom ,

Columbus, Ohio.

Of Counsel.

L a w y e e s P bess, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C.; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300

§>uprrmr Court

A ppellate D ivision— T hird D epartment.

STATE OF NEW YORK.

RAILWAY MAIL ASSOCIATION,

Plaintiff-R esponderd,

against

EDWARD S. CORSI, as Industrial Com

missioner of the State of New York, and

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN, as At

torney-General of the State of New York,

D efendam ts-Appellants.

RECORD ON APPEAL

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN,

Attorney General of the State of

New York,

Attorney for Defendants-Appellants,

Office and P. 0. Address,

The Capitol,

Albany, New York.

DUG AN & DUGAN,

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Respondent,

Office and P. O'. Address,

90 State Street,

Albany, New York.

I N D E X .

PAGE

Statement Under Buie 234................................ 1

Notice of A p p ea l................................................ 2

Complaint ........................................................... 3

A nsw er................................................................. 17

Stipulation Presenting Issues to Special Term 18

Judgment Appealed from ........................ 23

Order Appealed from ...................................... 27

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray....................... 30

Stipulation Waiving Certification......................44

'

STATE OF NEW YORK.

Court

A ppeelate D ivision— T hird D epartment.

RAILWAY MAIL ASSOCIATION,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

against

EDWARD S. CORSI, as INDUSTRIAL

COMMISSIONER of the State of New „

York, and NATHANIEL L. HOLD-

STEIN, as Attorney-General of the

State of New York,

Defendants-Appellants.

STATEMENT UNDER RULE 234.

This suit was commenced on December 28, 1942,

by service of the summons and verified complaint

upon the defendants. Those have been at all

times the officials discharging the duties of Indus

trial Commissioner and Attorney General, respec

tively, who were in 1942 Frieda S. Miller and John

J. Bennett, Jr., for whom have been substituted at

various times the persons succeeding to those of

ficial duties, the stipulations for such purpose be

ing omitted from printing in this record. Since

January 1, 1943, Nathaniel L. Goldstein has been

Attorney General and attorney for the defend

ants, and in November, 1943, Edward S. Corsi be

came Industrial Commissioner.

2

Notice of Appeal.

Issue was joined on or about May 28, 1943, by

service of a verified answer, and on September

16, 1943, the parties entered into a written stipu

lation upon which the issues were presented to the

Special Term.

NOTICE OF APPEAL.

SUPREME COURT—ALBANY COUNTY.

5 RAILWAY MAIL ASSOCIATION,

Plaintiff,

against

EDWARD S. CORSI, as Industrial Com

missioner of the State of New York, and

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN, as At

torney-General of the State of New York,

Defendants.

T o :

6 Dugan & Dugan,

Attorneys for Plaintiff,

90 State Street, Albany, New York.

And:

Albany County Clerk.

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE, that the defendants

above named (the defendant Edward S. Corsi hav

ing recently been appointed Industrial Commis

sioner and thus succeeded the former defendant,

Michael J. Murphy, as Acting Industrial Com-

3

missioner) hereby appeal to the Appellate Divi- y

sion, Third Department, from the order and judg

ment herein entered and filed in Albany County

Clerk’s office on November 24, 1943, and this ap

peal is from each and every part of such order and

judgment.

November 30, 1943.

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN,

Attorney-General of the

State of New York,

: Attorney for Defendants.

COMPLAINT.

STATE OP NEW YORK.

SUPREME COURT—ALBANY COUNTY.

-----------------------------------------——-----------\

RAILWAY MAIL ASSOCIATION,

Plaintiff, g

against

FRIEDA S. MILLER, as Industrial Com- .̂

missioner of the State of New York, and

JOHN J. BENNETT, JR., as Attor

ney-General of the State of New York,

Defendants.

Complaint.

Plaintiff for a cause of action herein through

Dugan & Dugan, its attorneys, alleges as follows:

4

̂ 1 . That the defendant, Frieda S. Miller, now

is .and was at the time herein stated the Industrial

Commissioner of the State of New York duly ap

pointed and acting and as such is the head of the

Department of Labor under the Labor Law of the

State of New York.

2. That the defendant, John J. Bennett, Jr.,

is the Attorney-General of the State of New York

duly elected and acting as such; that under Sec

tion 62 of the Executive Law of the State of New

York it is the duty of the Attorney-General to

1 1 prosecute and defend all actions and proceedings

in which the State is interested, and to have charge

and control of all the legal business of the depart

ments and bureaus of the State or of any office

thereof which requires the services of an attorney

or counselor.

3. That the plaintiff now is and was at all the

times hereinafter mentioned a foreign corpora

tion organized under the laws of the State of

New Hampshire and having its principal office at

̂ the City of Portsmouth in said State of New

Hampshire. That it is organized and established,

among other purposes, to conduct the business of

a fraternal beneficiary association for the sole

benefit of its members and beneficiaries and not

for profit.

4. That the other enumerated objects contain

ed in the charter of the plaintiff are as follows r

to promote closer social relationship among Rail

way Postal Clerks, to better enable them to per

fect any movement that may be for their benefit

Complaint.

5

Complaint.

as a class or for the benefit of the Railway Mail j ;>

Service; to provide relief for its members and

their beneficiaries and make provision for the pay

ment of benefits to them in case of death, sickness,

temporary or permanent physical disability, eith

er as a result of disease, accident or old age.

5. That for the purpose of administering the

business and fraternal affairs of the Railway Mail

Association there are established and maintained

a. National Association, Division Associations and

Branch Associations; that the Division Assoeia-

tions are established and maintained in areas in 4

accordance with the division of the Railway Mail

Service conducted by the United States of Amer

ica and with Branch Associations established 'with

in the areas and jurisdictions of said Division As

sociations.

6. That under Article III of the Constitution

of said Railway Mail Association membership

therein is confined to regular male Railway Pos

tal Clerks or male substitute Railway Postal

Clerks of the United States Railway Mail Serv- jg

ice who are of the Caucasian race or are native

American Indians.

7. That appointments and promotions in the

Railway Mail Service of the United States are

made under and pursuant to the Civil Service

Laws of the Government of the United States.

8. That the plaintiff carries on and conducts

its business and fraternal affairs through the Di

vision and Branch Associations aforesaid and

with the permission of various States of the Unit-

Complaint.

jg ed States, among which is the State of New York,

and that within such State of New York there are

established and maintained thirteen Branch As

sociations located in different parts of said State.

9. That under the Constitution of the plaintiff,

Article IV, the National Convention of the plain

tiff is the supreme executive, legislative and judi

cial body of the order and possesses and exer

cises the power to make' a Constitution, laws,

rules and regulations for the government of the

National Association, and of all Division Asso-

17 ciations and Branch Associations; and to annul,

repeal, modify, revise and change the same front

time to time; also to provide rules for the issu

ance of Charters to. Division Associations and

Branch Associations; and provide for its own

support, and do all other legitimate acts proper

or necessary to promote the welfare of the Rail

way Mail Association and to control its funds. .

10. That said Constitution provides further

that Division Associations and Branch Associa-

■jg tions shall adopt a Constitution, by-laws, rules

and regulations not inconsistent with the provi

sions of the plaintiff’s Constitution, and may

amend, repeal, modify, revise and change the

same from time to time, and that no Division or

Branch Constitution or amendment thereto shall

become operative or in force until approved by

the Executive Committee of the Railway Mail As

sociation.

11. That the plaintiff by its Constitution pro

vides for and selects an Executive Committee to

7

conduct the business and affairs of the plaintiff jg

in the interim between National Conventions which

Committee is the supreme executive and judicial

body of the plaintiff during the period between

holdings of its National Convention; that such

National Conventions are appointed to be held bi

ennially in the odd numbered years and that the

last National Convention was held in October,

1941, and that no National Convention is appoint

ed to be held until 1943, and that said Executive

Committee has authorized the commencement of

this action for the purpose of having the rights 20

of the plaintiff declared and established in the

declaratory judgment sought herein.

12. That membership in the Railway Mail As

sociation is comprised of- two classifications; one

of which is designated as general or 11011-benefi

ciary membership', and the other as beneficiary or

full membership.

That the beneficiary members contribute to a

benefit fund established by the levy upon said

beneficiary members of assessments which benefit 21

fund is created and maintained for the purpose

of paying claims of such beneficiary members or

their beneficiaries resulting from death or dis

ability occasioned to said beneficiary members

through external, violent and accidental means.

That the entire membership' in the Railway Mail

Association comprises upwards of 22,000 mem

bers, 99% of whom hold beneficiary or full mem

bership in said Association,

Complaint.

8

gg 13. That the Branch Associations of said Rail

way Mail Association have the right, subject only

to the terms and limitations contained in the Con

stitution of the Railway Mail Association, to pass

upon applications for and to elect and initiate ap

plicants into membership in the Railway Mail As

sociation.

14. That under the provisions of Article 20 of

the Labor Law of the State of New York, being

chapter 443 of the laws enacted in 1937, it is pro

vided under Subdivision 5 of Section 701, that,

23 “ The term ‘ labor organization’ means any

organization which exists and is constituted

for the purpose, in whole or in part, of collec

tive bargaining, or of dealing with employers

concerning grievances, terms or conditions of

employment, or of other mutual aid or protec

tion and which is not a company union as de

fined herein.”

15. That by Section 715 of the said Labor

Law, it is provided that,

24 “ The provisions of this article shall not

apply to the employees of any employer who*

concedes to and agrees with the board that

such employees are subject to and protected

by the provisions of the National Labor Re

lations Act or the Federal Railway Labor

Act, or to employees of the state or of any

political or civil subdivision or other agency

thereof, or to employees of charitable, edu

cational or religious associations or corpora

tions.”

Complaint.

9

16. That by Chapter 9 of the Laws of the State 2

of NewT York for the year 1940, Article 4, of the

Civil Rights Law of the State of New York was

amended by adding thereto a new section knoYn

as Section 43 which reads as follows:

“ Discrimination by labor organizations

prohibited. As used in this section, the term

‘ labor organization’ means any organization

which exists and is constituted for the pur

pose, in whole or in part, of collective bar

gaining, or of dealing with employers con

cerning grievances, terms or conditions of 26

employment, or of other mutual aid or protec

tion. No labor organization shall hereafter,

directly or indirectly, by ritualistic practice,

constitutional or by-law prescription, by tacit

agreement among its members, or otherwise,

deny, a person or persons membership in its

organization by reason of his race, color or

creed, or by regulations, practice or other

wise, deny to any of its members, by reason

of race, color or creed, equal treatment with

all other members in any designation of mem- 27

bers to any employer for employment, pro

motion or dismissal by such employer.”

17. That Section 41 of the Civil Rights Law of

the State of New York now in force provides as

follows:

“ Any person who or any agency, bureau,

corporation or association which shall vio

late any of the provisions of sections forty,

forty-a, forty-b or forty-two or who or which

shall aid or incite the violation of any of said

Complaint.

C

l

10

provisions and any officer or member of a

labor organization, as defined by section for

ty-three of this chapter, or any person repre-

resenting any organization or acting in its be

half who shall violate any of the provisions of

section forty-three of this chapter or who

shall aid or incite the violation of any of the

provisions of such section shall for each and

every violation thereof be liable to a penalty

of not less than one hundred dollars nor more

than five hundred dollars, to be recovered by

the person aggrieved thereby or by any resi

dent of this state, to whom such person shall

assign his cause of action, in any court of

competent jurisdiction in the county in which

the plaintiff or the defendant shall reside;

and such person and the manager or owner of

or each officer of such agency, bureau, cor

poration or association, and such officer or

member of a labor organization or person

acting in his behalf, as the case may be shall,

also, for every such offense be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction there

of shall be fined not less than one hundred

dollars nor more than five hundred dollars,

or shall be imprisoned not less than thirty

days nor more than ninety days, or both such

fine and imprisonment.”

18. That by Section 45 of said Civil Eights

Law, being Chapter 677 of the Laws of 1942 and

effective on May 6, of said year, it is provided

that:

Complaint.

11

“ The industrial commissioner may enforce ;>[

the provisions of sections forty-two, forty-

three and forty-four of this chapter. For

this purpose he may use the powers of ad

ministration, investigation, inquiry, sub

poena, and hearing vested in him by the labor

law; he may require submission at regular

intervals or otherwise of information, rec

ords and reports pertinent to discriminatory

practices in industries.”

19. That certain officers and members of oo

Branch Association of the Second Division of the

Kailwav Mail Association in the city of New York

have indicated an attitude to accept membership

in the Railway Mail Association by admitting ap

plicants to membership in such Branch Associa

tion contrary to and in violation of Article III

of the Constitution of plaintiff and have initiated

correspondence with the defendant, Frieda S.

Miller as Industrial Commissioner of the State of

New York, and raised the question of the legal

right of the plaintiff to insist upon the observ- ^

ance of the provisions of Article III of plaintiff’s

Constitution within the State of New York; that

said Industrial Commissioner has sought and re

ceived from the Attorney-General of the State of

New York his advice to the effect that the plain

tiff herein is a labor organization within the

meaning and contemplation of Chapter 9 of the

Laws of 1940 of the State of New York and comes

within the purview of the Labor Law and the

Civil Rights Law of the State of New York and

that Article III of the plaintiff’s Constitution is

Complaint.

12

invalid and unenforceable within the State of New

York and that the plaintiff has no valid or legal

right to deny to any applicant, otherwise duly

qualified, membership in the plaintiff’s organi

zation by reason of his race, color or creed.

20. That acting upon such advice the defend

ant, Frieda S. Miller as said Industrial Commis

sioner of the State of New York, has requested

the plaintiff to advise her for the completion of

the official records on this matter in the office of

the Commissioner of Labor of the future policy

of the plaintiff’s Branch Associations within the

State of New York with reference to compliance

with the Civil Rights Law and the Labor Law

aforesaid.

21. That plaintiff has notified the defendant,

Frieda S. Miller as such Industrial Commission

er of the State of New York, in reply to her re

quest aforesaid that the Civil Rights Law and

Labor Law aforementioned do not apply to the

plaintiff or its Branch Associations and if sought

gg to be applied would constitute and be a violation

of the Constitution of the United States and the

Constitution of the State of New York and fur

ther notified the said Commissioner of plaintiff’s

intention to bring action for a declaratory judg

ment of its rights and legal relations in the prem

ises.

22. Upon information and belief plaintiff al

leges that it is not a labor organization within

the spirit or contemplation of the Labor Law or

of the Civil Rights Law of the State of New York

Comjilaitil.

34

13

aforesaid but on the contrary is a membership 37

corporation authorized to, and carrying on the

business of a fraternal beneficiary association for

the benefit of its members and their beneficiaries

and not for profit.

That plaintiff draws its membership from male

clerks engaged in the Railway Mail Service of

the United States Government; that such Railway

Mail Service does not involve industrial enter

prise ; that appointments and promotions in such

Railway Mail Service are regulated and controlled

by the laws of the United States; that neither the

plaintiff nor any of the male Railway Postal

Clerks is engaged in industrial enterprise but its

members are and constitute a class of Civil Serv

ice employees of the United States Government

engaged in and conducting a governmental func

tion exclusive to the Government of the United

States and who possess certain peculiar rights

and privileges to security and protection in such

Government Service and have not the right to

strike to enforce any grievance in relation to their gg

service or employment in the Railway Mail Serv

ice.

23. That the defendant, Frieda S. Miller as

such Industrial Commissioner of the State oi

New York is asserting that the aforesaid provi

sions of the Labor Law and the amendments to

the Civil Rights Law as aforesaid apply to and

are controlling upon the plaintiff and its Division

and Branch Associations and members within the

State of New York, and that plaintiff is a labor

Complaint.

14

organization within the meaning of said statutes

and that because thereof, Article III of the Con

stitution of plaintiff is invalid and without force

or effect within the State of New York; that an

actual controversy exists between the parties

hereto as to their rights and legal relations aris

ing out of and as to the application to plaintiff

of the aforementioned Civil Eights and Labor

Laws involving public interests, including the in

terest of the plaintiff, and it is necessary and ex

pedient that the respective rights of the parties

_/j | be determined without delay and that adequate

relief is not presently available through other

forms of action.

24. That the provisions aforesaid of the Civil

Rights Law if sought to be applied against the

plaintiff, its Division and Branch Associations

and its members would be contrary to and viola

tive of the provisions of Section 6 of Article 1 of

the Constitution of the State of New York in that

it would deny to the plaintiff and its members,

and its Division and Branch Associations due

^ process and equal protection of law and would be

and constitute an unlawful and unreasonable

abridgement of the property rights of the plain

tiff and its Division and Branch Associations, and

would offend the due process provisions of the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Con

stitution of the United States in that said provi

sions of the Labor Law and of the Civil Rights

Law of the State of New York would create arbi

trary, capricious and unreasonable classifica

tions, and would deny to the plaintiff and its mem

Complaint.

15

bers, and its Division and Branch Associations 43

within the State of New York the equal protec

tion of the laws and would deprive the plaintiff

of its property without due process of law; and is

an invasion of and in contravention to Subdivision

7 of Section 8 of Article I of the Constitution of

the United States concerning the legislative

power of the Congress of the United States to es

tablish post offices and post roads.

25. That through the medium of an action for

a declaratory judgment the issue of the plaintiff’s

legal rights and the legal rights of its members, ^4

and its Division and Branch Associations within

the State of New York sought to be affected by

procedure on the part of the defendant, Frieda S.

Miller as the Industrial Commissioner of the

State of New York can be expeditiously and finally

determined and that plaintiff has no other ade

quate remedy at law.

AYHEREFOBE, the plaintiff demands judg

ment that this Court declare and determine as fol

lows : 45

1. That Sections 41, 43 and 45 of the Civil

Bights Law of the State of New York and the

provisions of the Labor Law as now in existence

have no application and do not apply to the plain

tiff, Bailwav Mail Association, its members, and

Division and Branch Associations, and that the

Bailway Mail Association is not a labor organi

zation within the meaning or contemplation of

such laws.

Complaint.

16

2. That if sought to be applied to the plaintiff

herein such laws are in contravention to the Con

stitution of the United States, Article I, Section

8, Subdivision 7, and of Articles Fifth and Four

teenth of the amendments to said Constitution

and ,to the provisions of Section 6 of Article 1 of

the Constitution of the State of New York.

3. That this Court declare and determine the

rights of the parties, not herein otherwise spe

cifically asked.

4. And for the further and consequential relief

that the Industrial Commissioner of the State

of New York be enjoined from taking any action

or procedure against the plaintiff or its Division

or Branch Associations within the State of New

York, or the officers or members thereof, and for

such other and further relief as may be legal and

equitable in the premises with costs.

DUGAN & DUGAN,

Attorneys for Plaintiff,

Office and Post Office Address,

90 State Street,

Albany, New York.

Complaint.

(Verified by John J. Kennedy as secretary-

treasurer on December 23, 1942.)

17

ANSWER,

STATE OF NEW YORK. 49

SUPPREME COURT— C ounty of A lbany .

RAILWAY MAIL ASSOCIATION,

Plaintiff,

against

MICHAEL J. MURPHY, as Acting In

dustrial Commissioner of the State of >

New York, and NATHANIEL L. GOLD

STEIN, as Attorney-General of the

State of New York,

Defendants.

The defendants above named, for an answer to

the complaint herein, plead as follows:

1 . Defendants hereby deny that the definition

of “ Labor organization” set forth in paragraph

fourteen of the complaint is applicable for any

purpose except Article 20 of the Labor Law, and

they further deny that it is applicable to the is

sues involved herein. 01

2. Defendants likewise deny that the statutory

provision alleged in paragraph fifteen of the com

plaint is applicable to the issues involved herein.

3. Defendants deny each and every allegation

of paragraph twenty-four of the complaint; and

;so much of paragraph twenty-two of the com

plaint as alleges that the plaintiff is not a labor

organization within the spirit or contemplation of

the Labor Law or of the Civil Rights Law of the

State of New York.

18

~2 4. Defendants lack knowledge or means of in

formation as to the truth or falsity of the allega

tion contained in the second sentence of para

graph twenty-two of the complaint, and likewise

as to certain allegations contained in other para

graphs of the complaint; and defendants believe

that the allegations of paragraph two of the com

plaint are in certain immaterial respects too

broad; but for purposes of this litigation defend

ants admit all allegations of the complaint except

those denied in the preceding paragraphs of this

■rjg answer.

WHEREFORE, defendants demand judgment

dismissing the complaint, with the costs and dis

bursements herein.

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN,

Attorney-General of the State of

New York,

Attorney for Defendants,

The Capitol, Albany, N. Y.

54 ~

(Verified by Henry S. Manley, Assistant Attor

ney-General, on May 28, 1943.)

Stipulation Presenting Issues to Special Term.

STIPULATION PRESENTING ISSUES TO

SPECIAL TERM.

(Same Title.)

IT IS PIEREBY STIPULATED, between the

parties herein, by their respective attorneys whose

names are undersigned:

19

(1 ) That the issues arising between the Com- 55

plaint and the Answer shall be submitted to a

Special Term of this Court to be held in the City

of Albany, New York, on the 24th day of Septem

ber 1943, as though upon a motion by the plaintiff

for summary judgment as prayed in the Com

plaint, and upon a cross-motion by the defendants

that the Complaint be dismissed.

(2) That such submission shall be upon oral

argument, and the primary briefs of each side

shall be exchanged at the time of the original hear

ing; answering briefs shall be exchanged and sub- ~i''>

mitted at such time as the Court may direct.

(3) That any decision made by the Court shall

be subject to appeal or other action as fully as

though presented by the adverse motions afore

said.

(4) It is agreed that the defendants may offer

in evidence, upon the hearing of the motions and

that any Appellate Court may consider as exhibits

offered by the defendants, the documents or ex

cerpts therefrom relied upon by defendants and

included in the following printed documents,

books and pamphlets, without any question being-

raised on the part of the plaintiff as to the gen

uineness or authenticity of such documents, or

on the ground that such documents are not the

best evidence of their contents:

(a) Pamphlet copy of charter, constitution,

etc., 1941-1943, of Railway Mail Association, as

printed by it;

Stipulation Presenting Issues to Special Term.

20

(b) Pamphlet, “ The Railway Mail Associa-

'><C’ tion and the Railway Postal Clerk” , as printed by

the Association, without date but apparently soon

after 1930;

(c) Periodical, “ Railway Post Office” , Vols.

42, 43 and 44, being the issues of July, 1940, to

May, 1943, inclusive:

(d) Proceedings of American Federation of

Labor 1941 annual convention held at Seattle, as

printed by the A. F. of L.;

(e) “ Handbook of American Trade-Unions” ,

1936 edition, being' Bulletin No. 618 of U. S.

Ilept. of Labor;

(f) Pamphlet copies of hearings before cer

tain committees of the House of Representatives,

as officially printed, the dates and titles of such

hearings and the particular testimony being the

following:

(I) 1939 Mar. 21. “ Substitute Postal Em

ployees” , particularly testimony of J.

Frank Bennett, Pres, of R. M. A., pages 46-

«0 50.

(II) 1940 Mar. 12. “ Substitute Postal Em

ployees” , particularly testimony of Pres.

Bennett, page 13.

(III) 1940 Apr. 5. “ Postal Employees Long

evity Pay” , particularly testimony of In

dustrial Secty. Strickland, pages 42-44.

(This was a joint sub-committee rather

than a House Committee.)

(IV) 1940 Apr. 25. “ Motor Garage Service” ,

particularly testimony of Pres. Bennett,

page 14.

Stipulation Presenting Issues to Special Term.

21

(V) 1941 Mar. 25. “ Basis for Computing Pay gj

for Overtime Work by Railway Mail

Laborers” , particularly testimony of Vice-

Pres. Harvey, page 7.

(VI) 1943 Feb. 25, 26. “ Postal Employees

Salary Bills” , particularly testimony of

Mr. Mitiguy, pages 73-74; Pres. Harvey,

92-98; Mr. Wright, 110-113; Mr. Gladstone,

140-142.

(VII) Either side shall have the right to call the

Court’s attention to any other testimony

or statement appearing in said pamphlets gy

designated as I-VI inclusive, given or made

in relation to the legislative measures be

ing considered at such hearings.

(g) Printed form, “ Application for Member

ship in the Beneficiary Department of the Rail

way Mail Association” ;

(h) Certificate of Affiliation, granted by the

American Federation of Labor to the Executive

Officers of the plaintiff, bearing date the 22d day •

of December, 1917; g;i

(i) “ The Labor Movement in a Government

Industry” , by Sterling Denhard Spero, publish

ed by George II. Doran Co., N. Y., 1924;

(j) “ The Black Worker” (sub-title, “ A

'Study of the Negro and the Labor Movement” )

by Sterling D. Spero and Abram L. Harris. Col

umbia University Press, 1931. Quotations from

pages 67-69, 57-58, and 122-124, typed and

submitted herewith, to which defendants shall

be limited;

Stipulation Presenting Issues to Special Term.

22

(34 (k) “ The Travelling Post Office” , by William

J. Dennis, published by Homestead Printing Co.,

Des Moines, 1916, pages 54-73;

(l) Four telegrams: Berkley to Meany, May

19, 1943; Meany to Berkley, May 20; Berkley to

Meany, May 21; Meany to Berkley, May 24;

(m) “ How Collective Bargaining Works” , a

1942 publication of the Twentieth Century Fund.

Only the line on page 961, “ Railway Mail As

sociation 22,700” , and the material on page 958

to the effect that this purports to be a list of trade

unions and statement of their 1941 memberships,

taken from the Report of the Executive Council

of the A. F. of L. for that year; but plaintiff re

serves the right to object to the receiving in evi

dence or the consideration of the same as exhibits

on appeal, upon the ground that the same are in

competent, immaterial and irrelevant to the is

sues of law raised in this action by the pleadings,

except as to the items (a) to (h) inclusive.

(5) It is further agreed that the plaintiff may

66 offer in evidence upon said hearing, and any Ap

pellate Court may consider as exhibits the fol

lowing documents or excerpts therefrom, viz.:

(1) Memorandum of Governor Herbert H.

Lehman in connection with his approval of Chap

ter 9 of the Laws of 1940 amending the Civil

Rights Law;

(2) Message of Governor Herbert H. Lehman

to the Legislature, January 3, 1940, in reference

to Industry and Labor;

Stipulation Presenting Issues to Special Term.

23

(3) Proceeding’s of Convention of 1917 of the ^

Railway Mail Association in re adoption of a

resolution for affiliation with the American Fed

eration of Labor, and submission on referendum

to the membership for approval; the form of bal

lot upon such referendum, appearing in the “ Rail

way Post Office” , together with articles and cor

respondence in relation to the question of affilia

tion as contained in the issues of said periodical

for the months of January-December, inclusive, in

the year 1917.

Dated: Sept. 16, 1943. ^

DUGAN & DUGAN,

Attorneys for Plaintiff.

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN,

Attorney-General,

Attorney for Defendants.

By Henry S. Manley,

Assistant Attorney-General.

---------------------- 69

JUDGMENT APPEALED PROM.

(Same Title.)

The issues raised by the pleadings in the above-

entitled action having duly come on to be heard at

a Special Term of this Court held at the Court

House in the City of Albany on the 24th day of

September, 1943, Justice William H. Murray

presiding, pursuant to the Stipulation of the

parties, that the same should be submitted as

Judgment Appealed From.

24

rjQ though upon a motion by the plaintiff for sum

mary judgment as prayed in the Complaint and

upon a cross-motion by the defendants that the

Complaint be dismissed; and the plaintiff hav

ing appeared therein by Dugan & Dugan, by

Daniel J. Dugan of counsel, and the defendants

having appeared therein by Hon. Nathaniel L.

Goldstein, Attorney-General of the State of New

York, by Orrin G. Judd, Esq., Solicitor-General,

Wendell P. Brown, Esq., First Assistant Attor

ney-General, and Henry S. Manley, Esq., As-

7 j sistant Attorney-General, of counsel; and the

questions involved having been argued orally and

in the Briefs of the respective counsel, and the

Court after due deliberation having ordered that

plaintiff’s motion for judgment in its favor be

granted and that the defendants’ motion to dis

miss the Complaint be denied and that a Declara

tory Judgment in favor of the plaintiff as prayed

in the Complaint be entered accordingly herein.

Now, upon motion of Dugan & Dugan, attor

neys for the plaintiff, it is declared and adjudged

2̂ as follows:

1. That the plaintiff is and was at all the times

stated in the Complaint herein a fraternal bene

fit insurance corporation organized under the laws

of the State of New Hampshire and having its

principal office at the City of Portsmouth in the

State of New Hampshire; and is organized and

established to conduct the business of a fraternal

beneficiary association for the sole benefit of its

members and beneficiaries and not for profit; to

promote closer social relationship among Rail-

Judgment Appealed From.

25

way Postal Clerks, to better enable them to per- 73

feet any‘movement that may be for their benefit

as a class or for the benefit of the Kailway Mail

Service; to provide relief for its members and

their beneficiaries and make provision for the pay

ment of benefits to them in case of death, sickness,

temporary or permanent physical disability either

as a result of disease, accident or old age.

2. That the plaintiff since September 4, 1913

has been authorized to conduct the business of a

fraternal benefit insurance corporation within the

State of New York under the applicable provi- ' I

sions of the Insurance Law of said State'.

3. That plaintiff is not a labor organization

within the meaning or contemplation of Sections

41, 43 and 45 of the Civil Rights Law of the State

of New York nor within the meaning and con

templation of Article 20 of the Labor Law of said

State.

4. That Article III of the By-laws and Con

stitution of the plaintiff which provides as fol

lows: “ Any regular male Railway Postal Clerk 75

or male substitute Railway Postal Clerk of the

United States Railway Mail Service, who is of the

Caucasian race, or a native American Indian,

shall be eligible to membership in the Railway

Mail Association” is not in conflict with the afore

said provisions of such Civil Rights Law and

Labor Law of the State of New York and that

such laws do not apply to the plaintiff, its division

and branch associations, officers or members

within the State of New York,

Judgment Appealed From.

26

5. That applied to the plaintiff, its division

and branch associations, officers or members with

in the State of New York, said provisions of the

Civil Rights Law and Labor Law of the State

of New York are illegal and have no legal force

or effect.

6. That the membership of the plaintiff com

prises regular and substitute male Railway Postal

Clerks of the United States Railway Mail Service

whose appointments and promotions in said Ser

vice are made under and pursuant to the Civil

77 Service Law of the Government of the United

States and that such clerks are not engaged in

private industry.

7. That the Industrial Commissioner of the

State of New York has no legal right nor power

or authority to regulate or control the business

as conducted by the plaintiff within the State of

New York.

8. And it is hereby further ordered, adjudged

and decreed that the Industrial Commissioner of

78 the State of New York, his deputies, officers, rep

resentatives and employees be and they are and

each of them is hereby permanently enjoined from

taking any action or procedure to apply or enforce

the provisions of Sections 41, 43 and 45 of the

Civil Rights Law of the State of New York, and/

or the provisions of Article 20 of the Labor Law of

the State of New York to or against the plaintiff,

its division and branch associations, officers or

members thereof, within the State of New York,

Judgment Appealed From.

27

or of interfering with the plaintiff’s right of selec- 79

tion of its members.

Judgment entered November 24, 1943.

WILLIAM H. MURRAY,

J. 8. C.

W. B. Clarke,

Clerk.

Order Appealed From.

ORDER APPEALED FROM.

At a Special Term of the Supreme Court 80

held in and for tire County of Albany,

at the Court House, in the City of Al

bany, New York, on the 24th day of

September, 1943.

Present: Hon. William H. Murray,

Justice.

(Same Title.)

The plaintiff herein having* brought this action

•against Frieda S. Miller, as Industrial Commis

sioner of the State of New York, and John J. 81

Bennett, Jr., as Attorney-General of the State of

New York, for a declaratory judgment by which

this Court should declare and determine as fol

lows :

1. That Sections 41, 43 and 45 of the Civil

Rights Law of the State of New York and the

provisions of the Labor Law* as now in existence

have no application and do not apply to the plain

tiff, Railway Mail Association, its members and

Division and Branch Associations, and that the

28

g2 Railway Mail Association is not a labor organiza

tion within the meaning or contemplation of such

laws;

2. That if sought to be applied to the plaintiff

herein such laws are in contravention to the Con

stitution of the United States, Article I, Section

8, Subdivision 7, and of Articles Fifth and Four

teenth of the Amendments to said Constitution and

to the provisions of Section 6 of Article 1 of the

Constitution of the State of New York;

(C,f) 3. That this Court declare and determine the

rights of the parties, not herein otherwise specifi

cally asked;

4. And for further and consequential relief

that the Industrial Commissioner of the State of

New York be enjoined from taking action or pro

cedure against the plaintiff or its Division or

Branch Associations within the State of New

York, or the officers or members thereof, and for

such other and further relief as may be legal and

equitable in the premises with costs; and the

84 present defendants having, by an Order of this

Court duly made and entered herein, been sub

stituted in the place and stead of the original de

fendants without prejudice to the proceeding’s

previously had herein; and the defendants having

appeared by Hon. Nathaniel L. Goldstein. Attor

ney-General of the State of New York, and inter

posed a verified Answer admitting all allegations

of the Complaint except that defendants denied

that the definition of “ labor organization” set

forth in paragraph fourteen of the Complaint is

Order Appealed From.

29

applicable for any purpose except Article 20 of o-

of the Labor Law and denied that it is applicable

to the issues involved herein; and likewise denied

that the statutory provision alleged in paragraph

fifteen of the Complaint is applicable to said is

sues ; and further denied each and every allega

tion of paragraph twenty-four of the Complaint

and so much of paragraph twenty-two thereof as

alleges that plaintiff is not a labor organization

within the spirit or contemplation of the Labor

Law or of the Civil Eights Law of the State of

New York, and which said denials raised questions gg

of law only as to the application and legal effect

as to the plaintiff of Sections 41, 43 and 45 of the

Civil Rights Law and of Article 20 of the Labor

Law of the State of New York; and the parties on

the issues of law so raised having entered into a

Stipulation, dated September 16, 1943, to submit

such issues to this Special Term as though upon

a motion by plaintiff for summary judgment as

prayed in the Complaint, and upon a cross-motion

by defendants that the Complaint be dismissed;

and such issues having been accordingly present- 87

ed to the Court; and after hearing Dug'an &

Dugan, as attorneys for the plaintiff, by Daniel

J. Dugan, of counsel, and the Hon. Nathaniel L.

Goldstein, Attorney-General of the State of New

York, by Orrin G. Judd, Esq., Solicitor-General,

Wendell P. Browm, Esq., First Assistant Attor

ney-General, and Henry S. Manley, Esq,, Assistant

Attorney-General, of counsel, for defendants, and

due deliberation being had thereon.

Order Appealed From,

30

Now, upon reading and filing the Summons and

Complaint, the Answer and said Stipulation, and

upon motion of Dugan & Dugan, attorneys for

the plaintiff, it is hereby

ORDERED, that plaintiff’s motion for judg

ment in its favor be and the same hereby is grant

ed ; and it is further ordered that defendants ’ mo

tion to dismiss the Complaint be and the same

hereby is denied and that a declaratory judgment

in favor of the plaintiff as prayed in the Com

plaint be entered accordingly herein.

Enter:

WILLIAM H. MURRAY,

Justice of the Supreme Court.

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

OPINION OF MR. JUSTICE MURRAY.

(Same Title.)

(Supreme Court, Albany County Special Term,

September 24, 1943)

(Justice William H. Murray presiding)

Appearances:

Dugan and Dugan, Esqrs., Attorneys for Plain

tiff. (Daniel J. Dugan, Esq., of Counsel.)

lion. Nathaniel L. Goldstein, Attorney-General,

Attorney for Defendants. (Orrin G. Judd, Esq.,

Solicitor General, Wendell P. Brown, Esq., First

Assistant Attorney-General and Henry S. Manley,

Esq., Assistant Attorney-General, of Counsel.)

31

MEMORANDUM gj

MURRAY, J.:

This action is by plaintiff for a summary de

claratory judgment, and a countermotion by de

fendants for a dismissal of the complaint. No

question's of fact are involved. The issues are of

law. Plaintiff is a membership fraternal bene

ficiary corporation organized in the year 1898

under the laws of the State of New Hampshire, at

which time the corporate name was National As

sociation of Railway Postal Clerks. The present ^

name of plaintiff was assumed by it September 21,

1904. The Certificate of Incorporation states

that: “ The object for which this corporation is

established is to conduct the business of a fraternal

beneficiary association for the sole benefit of its

members and beneficiaries and not for profit; to

promote closer social relationship among railway

postal clerks; to better enable them to perfect any

movement that may be for their benefit as a class

or for the benefit of the railway mail service; to

provide relief for its members and their bene-

ficiaries and make provisions for the payment of

benefits to them in case of death, sickness, tem

porary or permanent physical disability, either as

a result of disease, accident or old age.’

Both New Hampshire and New Y7ork States

have recognized and approved plaintiff’s Articles

o f Incorporation and by-laws to the effect that it

has the right to conduct a fraternal insurance

business within such States. Membership in

plaintiff is restricted to regular male Railway

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

32

Postal Clerks or male substitute Railway Mail

Postal Clerks of the United States Railway Mail

Service, who are of the Caucasian race or are na

tive American Indians. There are approximately

twenty-two thousand (22,000) members, classified

either as general or non-beneficiary or as bene

ficiary or full members. Ninety-nine (99%) per

cent of the members are beneficiary or full mem

bers, and upon death of such a member through

external, violent and accidental means, moneys

are paid by plaintiff to their designated bene-

q~ ficiaries. Appointments and promotions in the

Railway Mail Service are made under and pur

suant to the Civil Service Laws of the United

States.

There are Division and Branch Associations of

plaintiff in various states of the United States,

and within the State of New.York, there are es

tablished and maintained thirteen (13) Branch

Associations. Certain officers and members of a

Branch Association of the Second Division in the

City of New York have challenged the right of

96 plaintiff to insist on observance of Article III of

its Constitution that only persons of the Caucasian

race or native American Indians be admitted to

membership. The Attorney-General of the State

of New York has advised the Industrial Commis

sioner of the State of New York that plaintiff is

a labor organization, and that Article III of its

Constitution is invalid and unenforceable within

the State of New York. That plaintiff has no

valid or legal right to deny to any applicant, other

wise duly qualified, membership by reason of race,

color or creed.

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

33

The opinion of the Attorney-General is predi- 97

hated upon Section 43 of the Civil Eights Law

(Chapter 9, Laws of State of New York, 1940) as

follows:

“ Discrimination hy labor organizations

prohibited. As used in this section, the term

‘ labor organization’ means any organization

which exists and is constituted for the pur

pose, in whole or in part, of collective bar

gaining, or of dealing with employers con

cerning grievances, terms or conditions of

employment, or of other mutual aid or pro- 9.3

tection. No labor organization shall here

after, directly or indirectly, by ritualistic

practice, constitutional or by-law prescrip

tion, by tacit agreement among its members,

or otherwise, deny a person or persons mem

bership in its organization by reason of his

race, color or creed, or by regulations, prac

tice or otherwise, deny to any of its members,

by reason of race, color or creed, equal treat

ment with all other members in any designa

tion of members to any employer for employ- 99

ment, promotion or dismissal by such em

ployer.”

Also, under Section 41, Civil Eights Law (amend

ed by Chapter 9, Laws of State of New York, 1940

and amended further by Laws of 1941 and 1942).

Section 45 of the Civil Eights Law added by

the Laws of the State of New York, 1942, pro

vides :

“ Powers of administration vested in in

dustrial commissioner. The industrial com-

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

34

Iqq missioner may enforce tlie provisions of sec

tions forty-two, forty-three and forty-four of

this chapter. For this purpose he may use

the powers of administration, investigation,

inquiry, subpoena, and hearing vested in him

by the labor law; he may require submission

at regular intervals or otherwise of informa

tion, records and reports pertinent to dis

criminatory practices in industries.”

Defendants contend that plaintiff is a labor

organization, because of the provisions contained

101 in its Articles of Incorporation, in its Constitu

tion, and, because since the year 1917, plaintiff has

been a member organization in the American Fed

eration of Labor, having accepted a Certificate of

Affiliation from such Federation of Labor and

having contributed to the expenses of such or

ganization, and further by participating in its con

ventions and other activities.

Plaintiff emphatically denies it is a labor or

ganization in fact or in law measured, either by

the terms of its charter, its laws or by the nature

of the service and work its members perform.

Plaintiff maintains that the Labor Law of the

State of New York, Chapter 31 of the Consoli

dated Laws of the State of New York, Section 715

specifically exempts and excludes plaintiff from

the category of a labor organization even if it be

held that plaintiff is such a body.

Such law of immunity is as follows:

“ The provisions of this article shall not

apply to the employees of any employer who

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

35

concedes to and agrees with the board that

such employees are subject to and protected

by the provisions of the national labor rela

tions act or the federal railway labor act or

. to employees of the state or of any political

or civil subdivision or other educational or

religious associations or corporations.”

Defendants assert that the status of plaintiff

is defined clearly by the provisions of Section 43

of the Civil Rights Law, and that such statute is

valid and applicable to it. Plaintiff insists that

Sections 41, 43 and 45 of the Civil Rights Law

alone have no application to it, but are in pari

materia with other sections of the Labor Law

and all should be construed together. That the

new provisions of the Civil Rights Law were

designed to implement the provisions of the Labor

Law dealing with the same subject. Thus con

strued, the statutes and its subdivisions clearly

demonstrate a specific intent to exclude employees

of the State from, applications to them of the Civil

Rights Law, particularly Section 43.

105

Actions for declaratory judgments are proper

where the legality or meaning of a statute or of a

ruling made by an administrative official is in dis

pute and no question of fact involved. (Dun &

Bradstreet, Inc. v. City of New York, 276 N. Y.

198; Socony-Vacuum Oil Co. v. City of New York,

247 App. Div. 163; affd. 272 N. Y. 668.) The pur

pose of a declaratory judgment is to determine

disputed jural questions when a genuine con

troversy exists and when such a judgment will

serve a practical end in determining and stabiliz-

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

36

2Qg mg an uncertain or disputed jural question, either

as to present or prospective obligations. (New

York Operators v. State Liquor Authority, 285

N. Y. 272; James v. Alderton Dock Yards, 256

N. Y. 298; Sartorious v. Cohen, 249 N. Y. 31;

Brownell v. Board of Education, 239 N. Y. 369.)

The basic fundamental element presented for

determination is whether plaintiff is a labor or

ganization. Section 43 of the Civil Rights Law,

in part, specifically provides that:

“ No labor orgamsation shall hereafter di-

rectly or indirectly * * * deny a person ur

persons membership in its organization by

reason of his race, color or creed or by regula

tions, practice or otherwise, deny to any of

its members by reason of race, color or creed,

equal treatment with all other members in

any designation of members to any employer

for employment, promotion or dismissal by

such employer.” (Consolidated Laws, 1940,

Civil Rights Law, Article 4, Section 43.)

(Italics mine.)

108 • • „The 'term labor organization is defined in Sec

tion 43 of the Civil Rights Law in exactly the same

words, language and phraseology as is used in

Section 701, subdivision 5 of the Labor Law (Con

solidated Laws, 1937, Article 20) which is: “ That

a labor organization means any organization

which exists and is constituted for the purpose, in

whole or in part, of collective bargaining, or of

dealing with employers concerning grievances,

terms or conditions of employment, or of other

mutual aid or protection.”

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

37

What is collective bargaining! Some light is jqq

cast upon the meaning and implications of this

significant phrase by a statement of some of the

recognized evils which flow from refusal to bar

gain collectively as set forth in Section 700 of the

Labor Law as follows:

“ When some employers deny the right of

employees to full freedom of association and

organization, and refuse to recognize the

practice and procedure of collective bargain

ing, their actions lead to strikes, lockouts and

other forms of industrial strife and unrest ̂ j q

which is inimical to the public safety and wel

fare, and frequently endanger public health. ’

Collective bargaining broadly defined is an

agreement between an employer and a labor union

which regulates the terms and conditions of em

ployment with reference to hours of labor, wages,

and deals also with strikes, lockouts, walkouts,

arbitration, shop conditions, safety devices, the

enforceability and interpretation of such agree

ment and of numerous other relations existing be

tween employer and employee. ' 11

Plaintiff has only such rights and powers as are

expressly granted it by its charter or implied as

are necessary in the exercise of its corporate fran

chise. A proposition which is beyond dispute and

generally recognized is that a corporation cannot

enter into or bind itself by a contract prohibited

by its charter.

“ Corporations are artificial creations ex

isting by virtue of some statute and organized

for the purposes, defined, in their charters.

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

38

;j -j 9 * * * A corporation necessarily carries its

charter wherever it goes, for that is the law

of its existence.” (Jennison v. Citizens Sav

ings Bank, 122 N. Y. 135, at page 140.)

“ Wherever a corporation goes for busi

ness it carries its charter, and the charter is

the same abroad that it is at home.” (Relfe v,

Bundle, 103 U. S. 226.)

“ Whatever disabilities are placed on the

corporation at home it retains abroad, and

whatever legislative control it is subjected to

10 at home must be recognized and submitted to

by those who deal with it elsewhere.” (Mc-

Clement v. Order of Foresters, 222 N. Y. 470,

at page 480.)

When the State of New York through its De

partment of Insurance examined the Articles of

Incorporation and the certificates and other evi

dence of the insurance contract issued by plaintiff

to its members and conferred upon it authority to

transact insurance business within the State of

New York, it determined then and there by such -

114 decision both as a matter of fact and law that

plaintiff was a beneficial insurance society and

not a labor organization.

Section 154, subdivision 1, of the Insurance Law

states:

“ No policy of life insurance, industrial life

insurance, group life insurance, accident or

health insurance, group or blanket accident

or health insurance or non-cancellable dis

ability insurance, no fraternal benefit cer

tificate, and no annuity or pure endowment

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

39

contract or group annuity contract shall be

issued or delivered m this state unless a copy

of the form thereof shall have been filed with

the superintendent and approved by him as

conforming to the requirements of this chap

ter and not inconsistent with law.” (Italics

mine.)

Membership in plaintiff is confined strictly to

persons who pass United States Civil Service ex

aminations for the position of Railway Mail Clerk.

The primary purpose of Civil Service laws and

rules is to promote the good of the public service.

The underlying principle of such law is to afford

to everyone who has the necessary qualifications

.an equal opportunity of securing appointment.

(People -v. Kearney, 164 N. Y. 64; Matter of

Mendelson v. Finegan, 168 Misc. 102; affd. Men-

delson v. Kern, 278 N. Y. 568.)

Civil Service employees of the United States

are protected from summary removal except for

cause by Section 652 of the Classified Civil Ser

vice Code-Title 5, which is as follows:

“ Removals from classified civil service only

for cause. No person in the classified civil

service of the United States shall be re

moved therefrom except for such cause as

will promote the efficiency of said service and

for reasons given in writing, and the person

whose removal is sought shall have notice

of the same and of any charges preferred

against him, and be furnished with a copy

thereof, and also be allowed a reasonable time

for personally answering the same in writing;

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

40

j I g and affidavits in support thereof; but no ex

amination of witnesses nor any trial or hear

ing shall be required except in the discre

tion of the officer making the removal; and

copies of charg*es, notice of hearing, answer,

reasons for removal, and of the order of re

moval shall be made a part of the records of

the proper department or office, as shall also

the reasons for reduction in rank or compen

sation; and copies of the same shall be fur

nished to the person affected upon request,

] iq and the Civil Service Commission also shall,

upon request, be furnished copies of the same.

# # # y ?

Not only must charges be preferred, but they

must be based on substantial matters. To justify

removal the charges must be made in good faith

and not as a mere pretext for removal. Against

unjust discharge, employees have recourse to the

courts for redress, review and reinstatement in

their positions. They are shielded by law from the

anger and temper of arrogant, dictatorial and dis-~

120 agreeable superiors, who, to vent their spleen or

otherwise, prefer fanciful and unsubstantial

charges. No such safeguards surround the in

dustrial worker. When discharged, he is dis

charged, and that is the end of the matter. The

courts are not open to him for relief.

To tolerate or recognize any combination of

Civil Service employees of the Government as a

labor organization or union is not only incom

patible with the spirit of democracy, but incon

sistent with every principle upon which our Gov-

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

41

eminent is founded. Nothing- is more dangerous j2 (

to public welfare than to admit that hired servants

of the state can dictate to the Government the

hours, the wages and conditions under which they

will carry on essential services vital to the wel

fare, safety and security of the citizen. To admit

as true that Government employees have power

to halt or check the functions of Government, un

less their demands are satisfied, is to transfer to

them all legislative, executive and judicial power.

Nothing would be more ridiculous.

. t O O

The reasons are obvious which forbid accept- ^

ance of any such doctrine. Government is form

ed for the benefit of all persons, and the duty of

■all to support it is equally clear. Nothing is more

certain than the indispensable necessity of govern

ment, and equally true, that unless the people sur

render some of their natural rights to the Gov

ernment it cannot operate. Much as we all rec

ognize the value and the necessity of collective

bargaining in industrial and social life, nonethe

less, such bargaining is impossible between the IOO

Government and its employees, by reason of the

very nature of Government itself. The formidable

and familiar weapon in industrial strife and war

fare—the strike—is without justification when

used against the Government. When so used, it is

rebellion against constituted authority.

Plaintiff is not only not a labor organization

within the terms of its charter, but it does not ex

ist nor is it constituted for the purpose in whole

or in part of collective bargaining. The mere fact

that the American Federation of Labor issued to

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

42

Opinion o f Mr. Justice Murray.

124 plaintiff a Certificate of Affiliation, in no manner

repeals, rescinds or amends the charter g-ranted

plaintiff to transact insurance business. The ac

ceptance by plaintiff of such Certificate of Affilia

tion was an ultra vires act not within the powers

conferred on plaintiff by the State of New Hamp

shire, and is of no force or effect.

Collective bargaining has no place in govern

ment service. The employer is the whole people.

It is impossible for administrative officials to

bind the Government of the United States or the

125 State of New York by any agreement made be

tween them and representatives of any union.

Government officials and employees are governed

and guided by laws which must be obeyed and

which cannot be abrogated or set aside by any

agreement of employees and officials.

President Franklin H. Roosevelt in clear, def

inite and precise language declares that militant

tactics have no place in the functions of any or

ganization of Government employees as follows:

“ Upon employees in the Federal service

rests the obligation to serve the whole peo

ple, whose interests and welfare require

orderliness and continuity in the conduct of

Government activities. This obligation is

paramount.

Since their own services have to do with

the functioning of the Government, a strike

of public employees manifests nothing less

than an intent on their part to prevent or ob

struct the operations of government until

their demands are satisfied. Such action.

43

looking toward the paralysis of government 127

by those who have sworn to support it, is un

thinkable and intolerable.” (Letter written

to Luther C. Steward, President of National

Federation of Federal Employees.)

Section 43 of the Civil Rights Law creates no

new civil remedy. Any person who violates any

of its provisions is guilty of a misdeameanor. It

must be strictly construed. (People v. Bene, et al.,

288 N. Y. 318.) The purpose and intent of the

statute is that “ organized labor” must not dis

criminate as to membership in labor unions by rea- 1 8̂

son of race, color or creed. The purpose of Sec

tions 41, 43 and 45 is penal. They do not provide

for civil remedies. These sections were not en

acted for the purpose of compelling a fraternal

beneficiary insurance association to admit as mem

bers every person regardless of race, color or

creed.

Tested by the charter of plaintiff, the approval

of the State of New York, that plaintiff is a

fraternal beneficiary society, the type, kind and ̂

character of the employment of the members of

plaintiff, the New York State Labor Relations

Act and the Civil Rights Law construed together,

the demonstrated fact that Civil Service employ

ees of the United States have no right or author

ity to bargain collectively, the conclusion is un-

escapable that plaintiff is not a “ labor organiza

tion” within the purview of, Section 43 of the Civil

Rights Law. To hold otherwise would be to sanc

tion control of governmental functions not by laws

but by men. Such policy if followed to its logical

Opinion of Mr. Justice Murray.

44

jgQ conclusion would inevitably lead to chaos, dicta

tors and the annihilation of representative gov

ernment.

Judgment in accordance herewith is granted

plaintiff.

Submit order.

Dated: Troy, New York, November 4th, 1943.

Stipulation Waiving Certification.

131 STIPULATION WAIVING CERTIFICATION.

(Same Title.)

IT IS HEREBY STIPULATED AND

AGREED that the within printed record consists

of true and correct copies of the notice of appeal,

complaint, answer, stipulation presenting issues

to Special Term, judgment appealed from, order

appealed from and opinion of Mr. Justice Murray,

all of which are now on file in the office of the.

Clerk of the County of Albany, and that certifica

tion of said record and each and every part there

of is hereby expressly waived.

Dated: December . . . . , 1943.

NATHANIEL L. GOLDSTEIN,

Attorney for Defend ants-Appellants.

DUGAN & DUGAN,

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Respondent.

To be argued by

WENDELL P. BROWN.

upturn? (ta rt

OF T'HE

STATE OF NEW YORK.

A p p e l l a t e D ivision— T hird D epartment.

R ailw ay M ail A ssociation,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

against

E dward S. C orsi, as Industrial Commis

sioner of the State of New York, and

N athan iel L. G oldstein, as Attorney

General of the State of New York,

Defendcmts-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS.

Pursuant to an opinion rendered by Mr. Justice

Murray on November 4, 1943, at Albany Special

Term, the order and judgment which are appealed

from have granted to the Association a declara

tory judgment as prayed in the complaint, most

notably declaring and determining:

(1) That Civil Rights Law §43 and certain

related provisions forbidding discrimination

“ by reason of race, color or creed” do not

apply to the Association, and that it is not a

“ labor organization” within the meaning of

those provisions; and

(2) That such provisions if applicable are

unconstitutional.

2

The Statute Involved.

Civil Rights law §43 was enacted by chapter 9

of the Laws of 1940, and is as follows:

“ §43. Discrimination by labor organiza

tions prohibited. As used in this section, the

term ‘ labor organization’ means any organ

ization which exists and is constituted for the

purpose, in whole or in part, of collective

bargaining, or of dealing, with employers

concernings grievances, terms or conditions

of employment, or of other mutual aid or

protection. No labor organization shall here

after, directly or indirectly, by ritualistic

practice, constitutional or by-law prescrip

tion, by tacit agreement among its members,

or otherwise, deny a person or persons mem