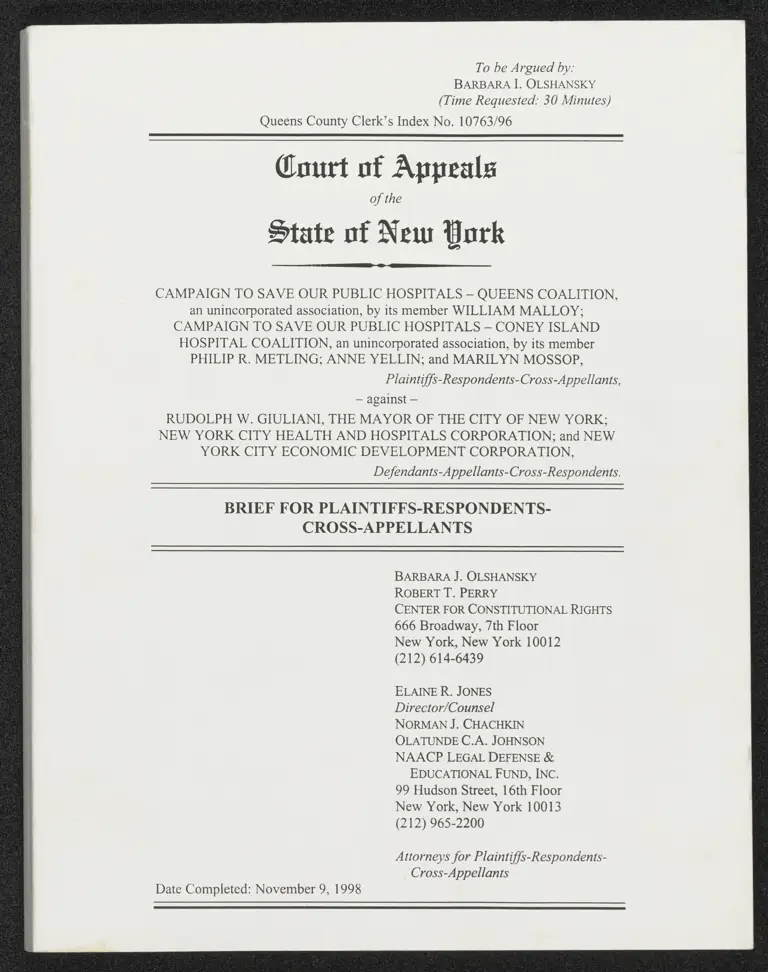

Brief for Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 9, 1998

70 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Brief for Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants, 1998. 66224e6a-6835-f011-8c4e-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6109e83c-e4f1-46c6-b6ec-054f6ee92ced/brief-for-plaintiffs-respondents-cross-appellants. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

To be Argued by:

BARBARA I. OLSHANSKY

(Time Requested: 30 Minutes)

Queens County Clerk’s Index No. 10763/96

(ourt of Appeals

of the

State of New York

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS — QUEENS COALITION,

an unincorporated association, by its member WILLIAM MALLOY;

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS — CONEY ISLAND

HOSPITAL COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its member

PHILIP R. METLING; ANNE YELLIN; and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants,

— against —

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK;

NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION; and NEW

YORK CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Respondents.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-RESPONDENTS-

CROSS-APPELLANTS

BARBARA J. OLSHANSKY

ROBERT T. PERRY

CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, New York 10012

(212) 614-6439

ELAINE R. JONES

Director/Counsel

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

OLATUNDE C.A. JOHNSON

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Respondents-

Cross-Appellants

Date Completed: November 9, 1998

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABILEOCRAUTHORITIES .. 0. iiss its tvcrsnsnssssansnssnsenoronanns ii

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT (i. cient ines ites se suo dneestvdvscanonenss 1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED: i... ood ihe ede bine se dibevsvsosdstnmrsrreda doit ceens 3

STATEMENT OERACTS co. iri ioe ieinrrnrtinsaseduaninssnsvaiansesos se 3

PROCEEDINGS BELOW ....cioiiciitvriecsseiivinrsvscnnennsnssitocsnsnnne 27

OPINIONS BELOW cn ii vi isnt nd iinssseniiasansdovasecasinsscssnns 28

ARGUMENT ...... i cic sec viririncvnrsrsssiirserssesssonsnsonsmenseesns 30

I. THE HHC ACT DOES NOT AUTHORIZE HHC TO DELEGATE ITS

ADMINISTRATIVE, MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONAL DUTIES

REGARDING THE PUBLIC HOSPITALS THROUGH A SALE OR LONG-TERM

SUBLEASE TO A PRIVATE, FOR-PROFIT CORPORATION ............... 30

A. The Transfer of Administrative, Management, and Operational Control Over

A Public Hospital to a Private, For-Profit Corporation Is Plainly Inconsistent

With HHO S Corporate PUIPOSES . «ccc scvvnvnersnesnesvenscnes Cen 30

B. The Inherent Conflict Between HHC’s Public Purpose and the Economic Goals

of A For-Profit Corporation Also Compels Rejection of the Proposed Hospital

Privatization PI. .. c i os recistnrnssnacmnsnsiiossintnsesesinsess 38

C. Even If The Hospital Privatization Plan Did Not Contravene The HHC Act, The

Proposed Sublease of Coney Island Hospital Would Violate The Act ..... 46

II. EVEN IF HHC WERE PERMITTED TO SUBLEASE CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL

TO PHS-NY UNDER THE HHC ACT, THE ACT WOULD REQUIRE A ULURP

REVIEW AND FINAL CONSENT OF THE CITY COUNCIL, ............... 31

CONCLUSION, i oe veces Dadar tse tinrsarisnnsssnassnnssssnnnsssersnaneniinhe 60

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES

Brym y. Roch, 627 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980), affc 492 F. Supp. 212(S.D.N.Y. 1980) ....... 51

Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Fortney Oil Co., County Farm Lease, 125 F.2d 995

BCH 1992. 0.0.0. aio. Lr SLBA Sn 31

Tockson vy HHC, 419F Supp. SOO(SDNY. 1978) ....... coi. einen, 51

Meriwether vy. Garrett, 1000S. 472, 261. Bd. 1971880) ............................ 41

Mortis v. Board of Education, SSI F.Supp. 6S2(ED N.Y. 1932) ...................... 52

Morris v. Board of Estimate, 592 F. Supp. 1462 (E.D.N.Y. 1984), aff'd, 831 F.2d 384

(24:Cir. 1937), affd. 489 U.S. 688 (1980)... 5, so a A eB as 52

Momisv. Board of Estimate 707 F.24.636 (3d Cir. 1983) ........ ....... 00. 0 0h 52

Morrisy Board of Bstimate. S31 FP 24334 02d CIr 1987) ....... oo. 0. iii. 52

New York City Board of Bstimatey, Moris 439 US.688(1989) ........ .............. 53

Wallace vy. Oceancering International, 727 F.24 427 (Sh Cit 1984) ..............cv vicinus 31

STATE CASES

Aldrich v. City of New York, 208 Misc. 930, 145 N.Y.S.2d 732

(Queens Co. Sup. Ct. 1953), aff'd. 2 A.D.2d 760, 154 N.Y¥.$.2d 927 (2d Dept. 1956) ....... 42

Alpert v. 28 William Street Corp., 478 N.Y.S.2d 443 (N.Y. Co. Sup. Ct. 1983),

did, 63 N.Y 2d5357, 473 NE 2d 19,483 NY S2A667(1934). .... ..........0.....0ui 39

American Dock Co. v. City of New York, 174 Misc. 183, 21 N.Y.S.2d 943

(Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1940), affd., 261 A.D. 1063, 26 N.Y.S.2d 704,

afd. 286 N.Y. 653,36 NE2d G96 (1941) ....... co. 3. oo hh. ial, 30, 42

Branford House. Ine. V. Michetti, 51 N.Y.24 631,603 N.Y.S.2d 29001990) .............. 34

Cohen'y, Cocoline Products. Inc, 309 N.Y. 119,127 NE2d906 (1955) ........onses 39, 40

Cotrone v. City of New York, 38 Misc. 2d 580, 237 N.Y.S.2d 487

(SUD, CL INES C0. 106 fh ns vc vssnnnn ranitidine vavanies 41, 42

Council of City of New York v. Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 662 N.Y.S.2d 516

RRL EE Se a Le i 3.31,32,37

Ellington Construction Co. v. Zoning Board Of Appeals

of Incorporated Village of New Hempstead, 77 N.Y.2d 114, 564 N.Y.S.2d 1001 (1990) ..... 35

Falbros Realty v. Michel, 200 A.D.2d 85, 612 N.Y.8.2d 561 (1st Dept. 1994) ............ 57

Ferrer v. Dinkins, 218 A.D.2d 89, 635 N.Y.S.2d 965 (1st Dept. 1996),

ghneal denjed, 83 N.Y.2d 801,644 N.Y.8.24 493, 666 N.E2d 1366 (1997) ............... 57

Fox v. Mohawk & tiudson River Humane Society, 165N.Y.517(19_) ..........0... 46, 47

Gewitzy. City of Long Beach: 330 NY .S.2d4 495 (Sup. Ct. Nassau Co. 1972) ............ 42

Giuliani v, Beves], SON. Y 2d 27,659 N.Y.S2d138(1997) ,..........c. civ inines vias 32

Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. Inc. v. State, 22 N.Y.2d 75, 238 N.E.2d4 705,

2OINY. S24 20001068)... ae. a BE EE es iia 55

Lai Chun Chan Jin v. Board of Estimate, 92 A.D.2d 218, 460 N.Y.S.2d 28 (1st Dept. 1983) .57

Lake George Steamboat v. Blais, 30 N.Y.2d 48, 281 N.E.2d 147, 330 N.Y.S.2d 336 (1972) .. 42

Lenard v. 1251 Americas Associates, 241 A.D.2d 391, 660 N.Y.S.2d 416 (1st Dept. 1997),

goneal withdrawn 20 N.¥Y.24 937, 664 N.Y. S.24275(1998) ................ ove... 35

Long v. Adirondack Park Agency, 76 N.Y.2d 419, 559 N.E.2d 635,

SON YS 24941 (1990) 8, 8, Sunt. ci i a a LE viii 30

Maidgold Associate v City of New York, 64 N.Y.2d 1124, 479 N.E.2d 823,

AON YS dd IST I08S) ho ia A IM hee a 56

Majewski v. Broadalbin-Perth Central School District, 91 N.Y.2d 577,

INN SBS. 20061008) a ee haa 31

Mann Theatres Corp. v. Mid-Island Shopping Plaza, 94 A.D.2d 466,

464 N.Y.S.2d 793 (2d Dept. 1983), aff'd, 62 N.Y.2d 930, 462 N.E.2d 51,

479 NY. S24 21341084) i... on aa IAN IIRL IIA ia 55

Matter of Davis v. Dinkins, 206 A.D.2d 365, 613 N.Y.S.2d 933 (2d Dept. 1994),

Iv. app. de. SSENLY. 2A 804 (1995) haat a a a ST a ies 55

Matter of Dodgertown Homeowners Associate, Inc. v. City of New York, 652 N.Y.S.2d 760

(24 Dept. 1997 mot. lv app. pending... 0. cues ee aa 55

Matter of New York Public Interest Research Group, 83 N.Y.2d 377, 632 N.E.2d 1255,

BIONY S24 93201984)... ci. i i ean 38

Matierof OnBank & Trust Co., 0 N.Y.24 725,663 N.Y.S.2d380(1998) ................ 34

Miller vi City of New York, ISNY2d 34, 25SNYS2T8Q9%4). ..........c0iviiciiiis 33

Ministers, Elders and Deacons of Reformed Protestant Dutch Church

of City of New York v. 198 Broadway, Inc., 76 N.Y.2d 411, 559 N.Y.S.2d 866 (1990) ..... 33

New York City Health and Hospitals Corp. - Goldwater Mem. Hospital v. Gorman,

113 Misc:2d33, 443N.V.S2d 623 (Sup. CL NV. Co. 1983). . oc. eosin 6

Oppenheimer & Co. v. Oppenheim, 86 N.Y.2d 685, 660 N.E.2d 415,

B36 NY S24734(1995) ........ cr RIND 56

Palak v- Pojal, SO NV. 2d 394 45INY.S20381 (1982) ...ccovvvuviiivivavervess 35

Parks Cay Cov. Annunzio 41210. 549, 107 NEA S33 (A032) .....coovviieiivsuiod, 31

People Hill SSNIY 2d 256, 2A NY. SIAT79(1995) .....c.ccvvoiiiiidadoiivirss 36, 37

People v» Olrensicin, 7ZN.Y.2d 38, S63 N.Y. SIA 744 (1990) ....... 0. vvvivin ou Sl, 43

People v. Smith. 532 N.Y.S.24 946, 79 N.Y.24 309, 591 NE2d 11321993) ............. 38

People v. Wesichestor County Notional Banke 23INY.465¢10 ) ............. ......., 43

Perlbinder v. New York City Conciliation and Appeals Board, 67 N.Y.2d 697,

490 NE: 2d 844, 400 N.Y. 8S 2A 925(1986), . 1... soi vids vrei ded 56

Rodriguezy Perales SON. Y.2d 361, 633N YS. 24252 (1995) ......... .....0oviuiuuuss 34

Rowe v. Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., Inc., 46 N.Y.2d 62, 385 N.E.2d 566,

AI2INY S.A R0741973) RS a EE ee a 55

Schulz v. State of New York, 86 N.Y.2d 255, 630 NYS2d9781995) ...... ............. 43

Waybro Corp. v. New York City Board of Estimate, 67 N.Y.2d 349, 493 N.E.2d 931,

SONY. S24 707 (1930) 4h ik rs seh ce nan a ee 57

Weiny. State, 39N.¥.2d4 136,347 N.E.2d 336,333 N.Y.8.2d 2251976) ............... 44

1934 0p AY Gen 93 citi LL. ol i Ui i a ee 37

1v

DOCKETED CASES

Kelley v. Michigan Affiliated Healthcare System. Ing. No. 96-83834B-C7 ................ 45

Tribeca Community Associate Inc. v. New York State Urban Development Corp.,

Index No: 2035502 (April 1, 1993 Sup. CL NY) ........ cciis cco aii. 55

FEDERAL STATUTES

HSL me La Bn el ep HE i a el Ses Te 12

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Designation Lists,

61 Fed. Rea. No. 251 (Dec 31, 1996). ... or. . ciis tite invisavs ainsi. 12

STATE STATUTES

New York State Constitution, Article XVII ............. AEC RC en passim

Municipal Home Rule Law S 10(5) ....... ci. vr icin cd ie ts saints dns aids 58

NY. Bus Comp Law S701 ....... 0. iis insects sis irisniois ives uss 39

Unconsolidated Lows 88 7381 e800: .. in... . ves etn isi te vas hci passim

MISCELLANEOUS

C. Brecher and S. Spiezo,

Privatization and Public Hospitals: Choosing Wisely for New York City,

AReportbythe Twentieth Century Fund (1995) ............c ci 0s esis 11,12

Commission on Delivery of Personal Health Services,

Comprehensive Community Health Services for New York Citv (Dec. 1967) .............. 5

New York City Comptroller Alan Hevesi, Analysis of Fundamental Issues

That Have Yet To Be Resolved (November 7,1996) ....... ...................... passim

Eleventh Annual Report of the Temporary Commission of Investigation

of the State of New York to the Governor

and the Legislatwre ofthe Stats of New York (1969) ............... 0 ii inin. 11

J. P. Morgan, Queens Hospital Network Offering Memorandum (October 25, 1995) ........ 14

New York City Commission on the Delivery of Personal Health Services,

Community Health Services for New York City (Dec. 1967) ........... cocoa 4

Vv

New York State Comptroller H. Carl McCall, Challenges Facing New York City’s

Public Hospital System, Rep. 4-99 (Aug. 5, 1998) «ee 9 10, 11

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The New York State Constitution requires New York State and New York City ("City") to

ensure that dignified and comprehensive physical and mental health care is available to all New York

residents regardless of their ability to pay for such care. New York State Constitution, Article XVII.

Pursuant to this mandate, in 1969, the State Legislature created the New York City Health and

Hospitals Corporation ("HHC") to operate the municipal hospitals and fulfill the City’s

constitutional obligations. Since that time, HHC's public hospital system has provided care for

hundreds of thousands of poor and uninsured New Yorkers who cannot afford the care of private

hospitals, and has played a disproportionately large role in caring for those who suffer from special

access problems due to conditions such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and psychiatric disorders.

Unlike private hospitals, by law, the public hospitals may not turn away patients because of their

inability to pay. Public Health Law § 2805-b.

In 1993, facing a budget deficit and committed generally to the privatization of certain assets

of the City as a fiscal solution, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani commenced his plan to dismantle the HHC

system though the sale or long-term lease of the public hospitals. In 1994, the City, through the

Mayor’s Office, began to explore the possibility of privatizing three of those hospitals, Coney Island

Hospital, Elmhurst Hospital Center and Queens Hospital Center. Under the Mayor’s hospital

privatization plan, HHC would no longer serve as the primary mechanism by which the City

provides health care services to its poorest residents; instead, private companies would operate and

manage the hospitals for their own profit and for that of their shareholders. Coney Island Hospital

in Brooklyn was selected as the first public hospital to be privatized, and on November 8, 1996, the

HHC Board of Directors approved a resolution authorizing the HHC Board President to negotiate

the terms of a 99-year sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-New York, a private, for-profit

corporation.

The Mayor's plan to privatize Coney Island Hospital and Queens and Elmhurst Hospital

Centers (the "hospital privatization plan") represents a significant departure from the constitutionally

and statutorily mandated practices of New York City and HHC, which have, for many years,

successfully ensured that New York City residents are provided with quality health care regardless

of their ability to pay.

For many of the City's poorest residents, the care they receive at the public hospitals run by

HHC is critical and life-sustaining. These residents are the most vulnerable to illness, possess the

fewest resources, and are the most in need of the medical protection offered by the public hospital

system. And, it is these residents who will be most affected by the changes contemplated under the

Coney Island Hospital sublease and the entire hospital privatization plan.

The proposed sublease of Coney Island Hospital constitutes an abandonment by HHC of its

long-standing policy of providing care to indigent and uninsured residents through services and

programs intended to address the specific needs of such patients. There can be little doubt that the

transfer of Coney Island Hospital to a for-profit company -- under terms which (1) place a financial

cap on the indigent care to be provided, (2) permit the termination of critical services to poor

residents, and (3) eliminate any effective monitoring system -- risks compromising the health status

of these New York City residents.

By instituting these changes in the provision of physical and mental health care services to

City residents, the Mayor’s hospital privatization plan disavows the City’s constitutional mandate

to provide quality and dignified care to indigent and uninsured New Yorkers, contravenes the New

York City Health and Hospitals Corporation Act, and effectively undermines HHC’s public mission.

Because Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Respondents (“Appellants”) have no authority to

2

undertake these actions, Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants (“Respondents”) Campaign to

Save the Public Hospitals et al. urge this Court to: (1) uphold the judgment of the Appellate

Division, Second Department, entered on September 8, 1997, and reported as Council of City of

New York v. Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 662 N.Y.S.2d 516 (2d Dept. 1997), in so far as it affirmed

that portion of the decision of the Queens County Supreme Court holding that the HHC Act

precludes the dismantling of the HHC system generally, and the long-term sublease of Coney Island

Hospital to PHS-NY, specifically; and ( 2) reverse the judgment of the Appellate Division, Second

Department with regard to its deletion of that portion of the Supreme Court’s decision holding that

any lease of an HHC facility must be approved pursuant to ULURP, and that any such lease must

be approved by the City Council as well as the Mayor.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does the HHC Act authorize Appellants to privatize the public hospitals, when the

Act established HHC to operate the municipal hospitals in order to fulfill the State's

and the City's constitutional obligations to provide health care for the residents of

New York City who cannot afford such services?

2 Do Appellants have the authority to sublease Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY, a

private, for-profit corporation, for 99 years, despite the fact that the HHC Act

established HHC as a public benefit corporation with a public purpose, and does not

authorize the transfer of a public hospital to a private corporation to be operated for

private gain?

3 Must the sublease of Coney Island Hospital be evaluated under the City's land use

review process and be approved by the City Council given that the HHC Act

provides that HHC leases must be consented to by the Board of Estimate, and the

City Charter now divides the authority for approving dispositions of City property

between the Mayor (for business terms) and the City Council (for land use terms)?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The public hospital system has existed in the City since the early nineteenth century in

recognition of the principle that “[t]he availability of health services, as a matter of human right,

should be based on health needs alone, not on a test of ability to pay.” New York City Commission

on the Delivery of Personal Health Services, Community Health Services for New York City 3 (Dec.

1967). Ensuring that health and medical care is available to all City residents, and particularly to

those who are unable to pay for these services, is not only a “moral undertaking,” id., but also a

constitutional obligation. New York State Constitution, Article XVII.

The New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation was created in 1969 at the request of

New York City to fulfill the City's constitutional obligation to provide health care services to its

residents, and was specifically charged with ensuring the provision of "high quality, dignified" care

to "those who can least afford such services." Unconsolidated Laws ("HHC Act") § 7382; New

York State Constitution, Article XVII. Reaffirming the City’s commitment to meeting this

constitutional mandate through the new public benefit corporation, Mayor John V. Lindsay, in a

letter addressed to Governor Rockefeller, stated:

In establishing a public benefit corporation, the City is not getting out of the hospital

business. Rather it is establishing a mechanism to aid it in better managing that business for

the benefit not only of the public served by the hospitals but the entire City health service

system. The municipal hospitals and health care system will continue to be the City’s

responsibility governed by its policies, determined by the City Council, the Board of

Estimate, the Mayor, and the Health Services Administration on behalf of and in consultation

with the citizens of New York City.

Letter of Mayor John V. Lindsay to Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor's Bill Jacket, L.

1969, ch. 1016. (emphasis supplied). This commitment by the City -- that it would continue to

oversee and control the operation of the public hospitals and determine health care policy as it had

since the beginning of the municipal hospital system -- is the foundation of the HHC Act.

Although the HHC Act was enacted into law in April 1969, the events that led to its

enactment began nearly three years earlier, in June 1966, when the New York Times published a

front-page story by reporter Martin Tolchin on the City’s public hospitals, describing shocking

4

neglect of patients and alleging waste of public funds." Tolchin’s article prompted a series of

investigations of the City’s public hospital system and led Mayor Lindsay in December 1966 to

create the nine-member Commission on the Delivery of Personal Health Services, under the

chairmanship of Gerard Piel, the publisher of Scientific American, to study the system and propose

reforms.” A year later, in December 1967, the Piel Commission, as it became known, issued its final

report.’

In December 1968, one year after the Piel Commission had issued its final report, Mayor

Lindsay announced that he would ask the State Legislation to create a public benefit corporation, the

HHC, to manage and operate the City’s public hospitals. The need for prompt action on the

'City to Set Up Panel to Review Hospitals, N.Y. Times, Dec. 21, 1966 at 1.

°Eleventh Annual Report of the Temporary Commission of Investigation of State of New

York, Legis. Doc. No. 93 (Mar. 1969), at 69; see also Tolchin, Serious Troubles Plague City

Hospitals as Medicare Approaches, New York Times, June 27, 1966, at 1.

*Commission on Delivery of Personal Health Services, Comprehensive Community

Health Services for New York City 51 (Dec. 1967) (“Piel Commission Report”). The issuance

of the Piel Commission Report followed public hearings on another report, Alternative

Organizational Frameworks for the Delivery of Health Services in New York City (Sept. 1967)

(“Alternative Frameworks”), prepared for another commission convened by the City’s Health

Services Administration (“HSA Commission”). Although it did not make recommendations, the

HSA Commission weighed the advantages and disadvantages of various organizational

frameworks, discussing the establishment of a public benefit corporation to run the City’s public

hospitals as an alternative to leasing those hospitals. Compare Alternative Frameworks at 31-33

(pros and cons of leasing public hospitals) with id. at 44-87 (public benefit corporation). While

selling or leasing the hospital was seen as having the advantage of reducing the City's operating

role, it was also seen as potentially "increas[ing] fragmentation of services, inequality of

distribution of services and inaccessibility of services to some patients." Id. at 32. In contrast,

the Report notes, the establishment of a public "Authority" to run the public hospitals would not

absolve the City of its responsibility to plan health services and to ensure that comprehensive,

quality care is available to all citizens. See id. at 57. In evaluating the various alternatives, the

HSA Commission recognized that one of the City’s primary goals was “[t]o insure that

comprehensive personal health care of high quality is available to all persons unable to pay its

full cost.” Id. at 4.

proposed legislation was brought home in January 1969, with the threatened closure of Harlem

Hospital because of funding cuts and the prospect that thousands of Harlem residents unable to

afford private hospitals would have nowhere to turn for health and medical care.” In late April 1969,

the State Legislature passed the HHC Act and in May 1969 Governor Rockefeller signed it into law.

The HHC Act

The HHC Act’s Declaration of Policy and Statement of Purposes declares that the City’s

hospitals:

are of vital and paramount concern and essential in providing comprehensive care and

treatment for the ill and infirm, both physical and mental, and are thus vital to the protection

and promotion of the health, safety and welfare of the inhabitants of the state of New York

and the city of New York.

HHC Act, § 7382. The Declaration of Policy further states that in order to accomplish these ends,

“a public benefit corporation, to be known as the New York City health and hospital corporation,

should be created” “to provide the needed health and medical services and health facilities.” Id.

The Act also expressly states that HHC’s exercise of its functions, powers and duties

“constitutes the performance of an essential public and governmental function” and charges the

corporation with the duties of operating and maintaining the public hospitals “in all respects for the

benefit of the people of the State of New York and the City of New York.” HHC Act § 7382

(emphasis supplied); New York City Health and Hospitals Corp. - Goldwater Mem. Hosp. v.

Gorman, 113 Misc.2d 33, 448 N.Y.S.2d 623 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1983).

To ensure that the performance of this “essential public and governmental function” would

remain under the control of the City, the Act requires that HHC “exercise its powers to provide and

“See Harlem Hospital Facing Shutdown, New York Times, March 21, 1969, at 1; Harlem

Hospital Firm on Closing, New York Times, March 22, 1969, at 1.

6

deliver health and medical services to the public in accordance with policies and plans” formulated

by the City. HHC Act § 7386(7). Moreover, the City is required to subsidize HHC for the costs

it incurs in providing medical services to indigent and uninsured City residents as mandated by the

Act. HHC Act § 7386(1)(a). Under the Act, this subsidy must be no less than $175 million per

year and must be adjusted annually to account for increases in health care costs and changes in the

volume of services rendered by the corporation for the City for which no third-party reimbursement

is available. Id.

Section 7385 of the Act confers upon HHC the power to borrow money, to make and execute

contracts and leases necessary for the fulfillment of its corporate purposes, and to operate, manage

and control any health facility under its jurisdiction. The power to operate a health facility also

includes the authority to contract with a private corporation for the provision of a discrete set of

“health and medical services for the public” to be offered “through and in health facilities of the

corporation.” HHC Act § 7386(8).

Section 7385 also specifically delineates the limits of HHC's authority to acquire or dispose

of the City’s health facilities. Under § 7385(6), HHC is empowered to acquire and to dispose of real

property, including a health facility, only "for its corporate purpose," and only after it holds a public

hearing and obtains the consent of the Board of Estimate. HHC Act § 7385(6). The corporation may

also, under § 7385(20), perform all or part of its functions through a wholly-owned subsidiary public

benefit corporation, so long as the subsidiary is subject to the same statutory limitations as those

imposed upon HHC.®

"The Act also authorizes HHC to sublease its properties to the City, HHC Act §

7386(2)(a), and empowers the City to sublease any health facility from HHC. HHC Act §

7386(2)(b). However, any such sublease must be either for the operation or the construction of a

health facility. HHC Act § 7386(3).

Finally, if HHC determines that a health facility (or any other real property of the City) is no

longer required for its corporate purposes and powers (i.e., operation as public health facility), it may

either surrender the property to the City or otherwise dispose of the facility subject to the approval

of the Board of Estimate, and the condition that all proceeds derived from the disposition be used

for HHC’s corporate purposes. HHC Act § 7387(4).

In creating HHC, the State Legislature thus intended to form the municipal hospitals into an

integrated public hospital system that would operate under the auspices of a single public benefit

corporation. See HHC Act § 7832. The Act specifically provides for the central administration of

the public hospital system to be assumed by HHC, and delineates the management role that HHC

must play in coordinating the operations of all of the municipal hospitals. See HHC Act, § 7835.

Today, under its operating agreement with the City,” HHC operates eleven acute care hospitals, five

long-term care facilities, seven free-standing diagnostic and treatment centers, two satellite clinic

networks, twenty hospital and neighborhood clinics, and a health maintenance organization. Ca 166.

The HHC Public Hospital System Today

The public hospital system operated by HHC is today the largest health care provider in the

City, having an annual operating budget of approximately $3.6 billion and over 38,000 employees.’

All of the City’s public health care facilities are under HHC’s control and subject to HHC’s

centralized management, administration and accounting, and HHC prepares a single, consolidated

°In 1970, HHC and the City executed an agreement in which HHC leased all of the public

hospitals from the City for a term consisting of the corporate life of HHC, at an annual rent of $1

(the “Lease”). The Lease requires HHC to operate the facilities and stipulates that “the services

that [HHC] will render are particularly for those who can least afford such services.” Ca 118.

"State Comptroller H. Carl McCall, Challenges Facing New York City’s Public Hospital

System, Report 4-99 (“State Comptroller’s 1998 Report”) (August 5, 1998) at 3. According to

the State Comptroller, HHC operates the largest municipal hospital system in the nation. Id.

8

revenue and expense budget for the entire system rather than separate budgets for individual health

care facilities. The financial interrelationship among the public hospitals is evinced by HHC’s

revenue sharing policy. Those hospitals which have revenues that exceed expenses may keep only

a portion of the excess revenue, with the remainder funneled back into the system to subsidize

weaker institutions. Thus, as was contemplated by both the City and the State Legislature at HHC’s

inception, the City’s public hospitals are today operated as a single integrated system under HHC’s

control ®

Regrettably, the creation of HHC has not eliminated all of the public hospital system’s

problems. Most observers attribute the current vulnerable position of the system to a number of

local pressures as well as industry-wide trends, including: (I) a drastic reduction in tax levy support

from the City; (ii) changes in State Medicaid reimbursement policies; (iii) a series of significant

workforce reductions; (iv) a substantial rise in the uninsured population; (v) an older and less well

maintained infrastructure and a fluctuating capital budget; (vi) competition for the public hospitals’

traditional patient population from managed care plans associated with the City’s voluntary

hospitals; and (vii) uncertainty arising from the hospital privatization plan.’

Since 1994, the City has decreased its tax levy support of HHC, intended to defray the costs

of health care provided to uninsured patients, prisoners, and uniformed officers, by nearly $300

®The public hospitals are not only subject to centralized management, but also

coordinated regional networking and planning. Ca 602; State Comptroller’s 1998 Report at 3. In

1994, HHC grouped its facilities into eight regional networks so that it could compete more

effectively for managed care patients by offering coordinated services within specific geographic

sections of the City. Id.

See State Comptroller’s 1998 Report at 3-19.

9

million, from $351 million (in fiscal year 1994) to $58 million (in fiscal year 1998)." Since 1994,

HHC has eliminated more than 10,000 positions throughout the system, a cumulative reduction of

22 percent, and plans to reduce staffing by another 3,000 employees by fiscal year 2002." Between

1994 and 1996, the absence of a system-wide capital budget brought major capital projects to a

virtual standstill, and delayed any consideration of new projects.’> Finally, as noted by State

Comptroller H. Carl McCall, there has been a significant increase in the City’s uninsured population:

“the number of individuals lacking health insurance residing in New York State has grown by nearly

50 percent since 1991, from 2.2 million to 3.1 million. Nearly 2 million of these individuals live in

New York City where the problem is more pronounced, and the uninsured rate is 50 percent higher

than the national average.” All of these factors have made it more and more difficult for HHC to

continue providing essential physical and mental health services to the City’s poorest residents, i.e.,

to perform the essential government functions for which it was created.

*°See State Comptroller’s 1998 Report at 5-7. According to the State Comptroller, rising

Medicaid payments over the last decade have “masked significant reductions in City funding in

other areas. . . . In total, the City paid $550 million to HHC in FY 1988. ...In FY 1998, the

City provided HHC with only $58 million, which was tied directly to services HHC provided for

the City, such as mortuary services and medical care to uniformed employees.” Id. at 6-7.

See State Comptroller’s 1998 Report at 14.

"According to the State Comptroller, HHC’s $668 million Capital Plan for fiscal years

1999 through 2003, will be financed through State Dormitory Authority (“SDA”) bonds. The

City, through a lease agreement, will reimburse SDA for the debt service on the bonds. State

Comptroller’s 1998 Report at 23.

**State Comptroller’s 1998 Report at 8. As the State Comptroller notes in his Report, this

growth is due to the decline in private coverage, which often requires prohibitively expensive

employee contributions from low-wage employees, and the loss in Medicaid coverage as

individuals are removed from the welfare rolls pursuant federal welfare reforms. As a result of

these factors, HHC is currently experiencing “a 33 percent increase in the number of patients

without public or private insurance.” Id. at 9.

10

The Essential Health Care Services Provided By HHC

The public hospital system run by HHC -- including Coney Island Hospital, Queens Hospital

Center, and Elmhurst Hospital Center, the three hospitals currently targeted by the Mayor for sale

or long-term sublease to private, for-profit corporations -- provides critical mental and physical

health care services for City residents who are indigent or uninsured. In this regard, the HHC system

fulfills the unique and irreplaceable function of providing care for those who cannot afford to be

cared for by private hospitals. Ca 590. While public hospitals may not turn away patients because

of their inability to pay for their care, private hospitals may refuse to serve the uninsured and

underinsured except in cases of emergency. Public Health Law § 2805-b. Thus, many private

hospitals limit the volume of Medicaid and uncompensated care they provide.

City-wide, HHC clinics provide 65 percent of all hospital-based outpatient care for uninsured

residents. Although HHC facilities have only 19 percent of all inpatient beds in the entire New York

City health care system, those facilities provide nearly 40 percent of all inpatient care for the City

residents enrolled in Medicaid and those lacking any insurance." In 1994, 96 percent of all inpatient

care provided by HHC was for the City’s indigent residents, those receiving Medicaid and Medicare,

“Reference is made herein to three types of hospitals: public, voluntary and proprietary.

Public hospitals are those owned and operated by government, such as the municipal hospitals of

New York City. Voluntary hospitals are private, non-profit institutions, and proprietary hospitals

are privately owned and are operated for profit. See Eleventh Annual Report of the Temporary

Commission of Investigation of the State of New York to the Governor and the Legislature of the

State of New York 67 (1969). Coney Island Hospital operated for-profit by PHS-NY would fall

within the “proprietary” category.

>See Charles Brecher and Sheila Spiezo, Privatization and Public Hospitals: Choosing

Wisely for New York City, A Report by the Twentieth Century Fund (1995) at 21-22.

11

and those who were uninsured. '®

HHC facilities also play an essential role in caring for patients with special access problems.

Ca 590-594. In 1996, HHC provided 51 percent of the hospital-based outpatient care received by

HIV/AIDS, and served 37 percent of HIV/AIDS patients who required inpatient visits, 46 percent

of all tuberculosis patients, and 45 percent of all psychiatric patients. Ca 590-594.

The Medical Needs Of The Affected Communities

The communities served by Coney Island Hospital, Queens Hospital Center, and Elmhurst

Hospital Center — the three public hospitals initially targeted for privatization — have significant and

continuing needs for those public hospitals, notwithstanding Appellants’ suggestion to the contrary.

App. Br. at 4-5.

Both South Queens and Southeast Brooklyn have been designated as primary medical care

professional shortage areas by the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, pursuant

to Section 332 of the Public Health Service Act. 42 U.S.C. § 254. The Coney Island community

has also been designated as a dental health care professional shortage area.'’

Many of the health status indicators for South Queens and West Queens have been found to

be significantly worse than those of Queens as a whole, and in some cases, even the City as a whole.

For example, according to the Health Systems Agency's July 1993 Community Health Profiles, both

Queens communities suffer from: (i) a high incidence of infant mortality and a high proportion of

low birth weight births; (ii) a high incidence of AIDS cases and a high death rate for AIDS patients;

**See Charles Brecher and Sheila Spiezo, Privatization and Public Hospitals: Choosing

Wisely for New York City, A Report by the Twentieth Century Fund (1995) at 9.

"See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Designation Lists, 61 Fed. Reg.

No. 251 (December 31, 1996).

12

(iii) high death rates for drug related conditions; and (iv) a high incidence of tuberculosis.

Of'the 85,401 AIDS cases reported in the City in 1996, Brooklyn had 24 percent, and Queens

had 15 percent,” of which 37 percent were found in South Queens.’ While the tuberculosis rate

for Queens (27.3 per 100,000) is below the City average (44 per 100,000), 33 percent of those have

tuberculosis in Queens live in South Queens. The tuberculosis rate for Brooklyn (45.8 per 100,000),

exceeds the City average.” Brooklyn also accounts for 30 percent of the City's population with

substance abuse problems and has a substance abuse hospital admission rate roughly equal to the

city-wide figure.”

Coney Island Hospital is the largest health care facility in southern Brooklyn with 457 beds

It serves a population of 750,000. Like Queens Hospital Center, Coney Island Hospital provides a

wide range of inpatient and outpatient services and community-based programs, including a

comprehensive women's health center, pediatrics and adolescent medicine clinics, and extensive

mental health and chemical dependency services. In 1995, 87.8 percent of all outpatient visits to

Coney Island were by Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries or by uninsured patients. Ca 591.

Queens and Elmhurst Hospital Centers are the only public acute care facilities in the Borough

"Health Systems Agency of New York City, Queens Community Health Profiles (J uly

1993).

"New York City Department of Health - Bureau of Disease Intervention Research,

“Epidemiologic Profile of HIV/AIDS in New York City” (“DOH Profile”) (August 1996) at 1.

**New York City Department of Health - Bureau of Disease Intervention Research,

“Epidemiologic Profile of HIV/AIDS in New York City” (“DOH Profile”) (August 1996) at 1.

**New York City Department of Health - Bureau of Tuberculosis Control, “Tuberculosis

in New York City 1994 Information Summary at 12.

??Health Systems Agency of New York City, Interim HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan for the

City of New York, (1996) Volume 1 at 62.

13

of Queens. Queens Hospital Center operates a 408-bed inpatient facility, an extensive ambulatory

program and emergency room, alcoholism and drug treatment programs, a methadone maintenance

clinic, psychiatric facilities, and an alternative care program for patients who have difficulties finding

a home. In 1995, 36 percent (113,199 patients) of all outpatient visits to Queens Hospital Center

were made by uninsured patients.”

Elmhurst Hospital Center operates a 563-bed inpatient facility, and recently completed a

major modernization project which included the development of a Community Medical Center and

a Surgical and Diagnostic Center. It also operates one of the City's most extensive Home Care

Departments, with programs including an Adult Program for medical and surgical patients, a

Maternal Child/Pediatric Program to meet the needs of mothers, infants, and children, a Pediatric

Respiratory Program to assist children with asthma, and an Infusion Therapy Program to provide

antibiotic and anti-viral therapy for outpatients (including HIV/AIDS patients). Like Queens

Hospital Center, Elmhurst Hospital Center also renders a significant portion of its health care

services to indigent and uninsured residents. In 1995, 47 percent (258,428 patients) of all outpatient

visits at Elmhurst were made by uninsured patients.

In Brooklyn and Queens, HHC clinics provide 72 percent and 64 percent of HIV/AIDS

primary care, respectively.

Despite HHC’s cardinal role in providing these essential health and medical services,

Appellants have made no assessment of the current utilization rates, functions, and services

2]. P. Morgan, Queens Hospital Network Offering Memorandum (October 25, 1995) at

36.

*]. P. Morgan, Queens Hospital Network Offering Memorandum (October 25, 1995) at

36.

14

provided in the affected communities by any of the three public hospitals targeted for privatization,

or the potential effects of the changes on City residents that might result from the long-term leasing

of these facilities.

The Hospital Privatization Plan: Contracting For The Provision Of Care

The dismantling of the public hospital system through the sale or long-term lease of the

City’s public hospitals to private companies has been a cornerstone of Mayor Giuliani's fiscal

program since he came into office. In early 1994, the Mayor chose the New York City Economic

Development Corporation ("EDC") to manage the hospital privatization plan. In August of 1994,

EDC retained J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc. ("J.P. Morgan") to prepare an initial assessment of the

plan.

On April 4, 1995, EDC announced that the hospital privatization plan would commence with

three hospitals. The selection of Coney Island Hospital, Queens Hospital Center, and Elmhurst

Hospitals Center was evidently based on a single report by J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc. ("J.P.

Morgan Report") which concluded that these three public hospitals had desirable assets that would

attract buyers, and that the current shift to managed care provided a unique opportunity for the City

to sell these facilities.

The J.P. Morgan Report, however, did not consider the impact of the sale upon the continuity

of care for indigent residents of New York City. Although recognizing that this factor was a critical

issue in evaluating the Mayor’s privatization plan, the Report conceded that it had not been

addressed at all:

The financial benefits to the City of New York, of course, also depend upon factors

not considered in this analysis, such as conditions of sale relating to care of the

indigent, provision of services to the City and the like.

See J.P. Morgan Report at 30, Ca 190.

15

Despite the complete absence of any analysis of the impact of the sale upon the continuity

of care for indigent City residents, EDC proceeded with the Mayor’s plan. On August 1, 1995, EDC

retained J.P. Morgan once again, this time to act as the City’s financial advisor, and to perform

financial analyses of the three targeted public hospitals, design financing structures for each

transaction, prepare marketing materials, identify and contact buyers, and assist in analyzing offers

and negotiating financial terms.

On October 26, 1995, EDC received the two Offering Memoranda that had been prepared

by J.P. Morgan for the privatization of the three public hospitals. Contrary to Appellants’

description of the privatization plan development process, App. Br. at 4, there was no input from

the HHC Board of Directors, the HHC Community Advisory Boards, the City Council or the public

in the planning process. Their input was neither solicited nor accepted by the Mayor’s Office or

EDC. Nor was any opportunity afforded for these groups to provide input in the drafting of the

Offering Memoranda. Ca 113.

While Appellants assert that the Offering Memorandum for Coney Island Hospital “set

rigorous conditions to ensure that any private entity that subleased the hospital would advance

HHC’s corporate mission,” App. Br. at 6, that simply was not so. The Memoranda given to

prospective buyers did not delineate any health care services requirements, specify any level of care

to be provided, require any specific level of access for uninsured patients, or set any objective

standard for determining the impact of the privatization plan on the City's service delivery or its

costs. The Offering Memoranda were nonetheless distributed by EDC to a secret list of potential

buyers, who were then allowed to submit bids on the three public hospitals.

The Coney Island Hospital Transaction

While the Offering Memoranda expressly stated that the hospital privatization plan was to

16

be accomplished through long-term leases of the three facilities to not-for-profit health care

providers, this did not happen. Instead, without any input from the HHC Board, Appellants’ selected

a for-profit corporation, PHS-NY, Inc. (“PHS-NY”),”> a subsidiary of Primary Health Systems, Inc.

("Primary"),”® to sublease and operate Coney Island Hospital.

On June 26, 1996, Peter J. Powers, then First Deputy Mayor of the City, Dr. Luis Marcos,

President of HHC, and Steven Volla, Chairman of Primary and PHS-NY, executed a letter of intent

to conduct negotiations on a long-term sublease of the property, plant and equipment of Coney

Island Hospital to PHS-NY. Ca 245. On October 8, 1996, pursuant to § 7385(6) of the HHC Act,

the New York City Department of Health and HHC jointly convened a public hearing on the

proposed sublease of Coney Island Hospital. Although the hearing was scheduled ostensibly in

order to receive public input on the proposed sublease, the City did not make the ninety-page

document — nor any of the other transaction documents” — available to the public prior to the

hearing. Instead, only a 10-page summary was circulated just four days prior to the hearing. While

Appellants assert that “an abstract of the terms and conditions of the sublease was distributed to the

*’PHS-NY was incorporated on June 25, 1996 in Kings County, New York as a privately-

held, for-profit corporation.

**Primary is a privately-held Delaware corporation whose principal officers also serve as

the officers and shareholders of PHS-NY. Primary has a very limited (but controversial) record

as a health care provider, having entered the field by acquiring three hospitals in Ohio between

1992 and 1993. Ca 251-53,

"These documents included the Governing Agreement between HHC and PHS-NY, the

Guaranty of Collection by Primary to HHC, ensuring PHS-NY’s performance of the Indigent

Care Obligations set forth in the Lease, and the Tri-Party Agreement. The Tri-Party Agreement,

signed by the City, HHC, and PHS-NY, permits PHS-NY to succeed HHC in the prime lease

when it expires, requires the City to seek authorization for the sale of Coney Island Hospital if

PHS-NY demands, and sets the purchase price at $1.00 plus the remaining debt service rent.

Indeed, these documents were not made available to the public or even the HHC Board until May

13,1997.

17

public,” App. Br. at 10, that summary omitted a number of key provisions contained in the proposed

sublease, and did not discuss any of the other terms of the transaction.”® The City did not publicly

release the 90-page proposed sublease until October 23, 1996, more than two weeks after the public

hearing.

The HHC Board Vote And The Missing Information

On November 7, 1996, Comptroller Alan Hevesi (the "Comptroller") published a

comprehensive analysis of the proposed sublease of Coney Island Hospital, addressing the potential

impact of the deal on the continued provision of quality care to the South Brooklyn community

served by Coney Island Hospital and the continued ability of the HHC system to provide care for

those who cannot afford to pay. In his report, the Comptroller concluded, among other things, that:

. the "sublease does not guarantee that PHS-NY will see everyone who needs care

regardless of ability to pay";

% the "sublease does not require that PHS-NY see a specific number of uninsured

patients";

% "[Primary’s] own data shows that it has a poor track record in providing indigent

care’;

i "the sublease does not specify the particular services that PHS-NY must provide";

and

X "the sublease does not make provision for effective outside monitoring."

See Comptroller Alan Hevesi, Analysis of Fundamental Issues That Have Yet To Be Resolved

(November 7, 1996) (hereinafter “Fundamental Issues”) at 1-28, Ca 606-634.

On November 8, 1996, just two weeks after the proposed sublease had been made publicly

available, and without any public hearing on the 90-page document, the HHC Board of Directors

**Given the minimal amount of information provided, Appellants’ “Public Briefing”

efforts cannot be termed anything other than a sham. App. Br. at 9-10.

18

voted to approve a resolution authorizing the sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY for an

initial term of 99 years, with an option to renew for an additional 99-year term to be held by PHS-

NY.” Not only were HHC Board members constrained to evaluate the limited information that was

provided to them in an extremely compressed time frame, they were also denied critical information

regarding key terms of the deal and three of the four primary agreements governing the relationships

among the parties, including the Governing Agreement between HHC and PHS-NY, the Guaranty

of Collection by Primary to HHC, and the Tri-Party Agreement. See n.24 supra.

Specifically, at the time of the vote, HHC Board members had not been provided with any

of the following items: (1) the contract setting forth the conditions to closing; (2) the agreement

embodying Primary's guarantee of PHS-NY's indigent care obligations; (3) an agreement setting

forth the terms of financing for the sublease; (4) a complete and enforceable agreement between the

City and HHC regarding the City's reimbursement of the costs of indigent care in excess of the

trigger point; (5) a delineation of the specific services that PHS-NY will be required to provide under

the sublease; (6) the findings and underlying documentation regarding any investigation into the

background and financial interests of the corporate and individual stockholders of Primary; (7) an

appraisal of Coney Island Hospital that would indicate its market value to permit an assessment of

whether the transaction represents the best deal; (8) information on whether PHS-NY will continue

to provide free care for prisoners and for the work-related needs of the City's uniformed services:

and (9) an analysis of the impact of the planned layoffs at Coney Island Hospital on the HHC

system. Given the nature and amount of information missing from the presentation, Appellants’

2In his report, Comptroller Hevesi questioned whether HHC even has the authority to

sublease Coney Island Hospital property for a period of 99 years, given that HHC’s own lease of

Coney Island Hospital expires in 71 years. See Hevesi, Fundamental Issues, at 28, Ca 633.

19

depiction of the Board briefing prior to the vote, see App. Br. at 11, simply cannot be credited. All

of this information was also unavailable to the general public at the time of the public hearing on the

proposed sublease.

The Proposed Coney Island Hospital Sublease

Appellants’ superficial recitation of the terms of the Coney Island Hospital transaction, see

App. Br. at 7-9, cannot mask the fact that the transaction contemplates the implementation of

significant changes to the practices that lie at the heart of HHC's public mission to provide critical

health care services to the poor residents of the City.

The Cap On Indigent Health Care Services

The proposed sublease does not guarantee that PHS-NY will treat everyone who needs care

regardless of their ability to pay. Indeed, it does not even require PHS-NY to treat a specific

number of uninsured patients. Rather, in Section 28.05, PHS-NY merely rontites to provide health

care services to indigent and uninsured persons up to a specific charity care expense level.” See

Proposed Sublease § 28.05. Ca 473j-473k. That section establishes a cap on PHS-NY's obligation

to serve indigent residents, defining the extent of PHS-NY's obligation solely in terms of a fixed

dollar amount. Id. Section 28.05 thus contemplates a complete departure from HHC's practice of

seeing all patients without regard to insurance status or ability to pay.

Under the terms of the proposed sublease, PHS-NY is required to absorb the costs of

providing care to indigent residents up to a "trigger point" equal to 115 percent of the current annual

charity care expense of Coney Island Hospital. Proposed Sublease § 28.05(d)(11). Ca 473k. This

*’PHS-NY will also provide those essential health care services included in certain "core"

departments "that Coney Island Hospital provides on the day before the closing on the sublease."

Proposed Sublease § 28.01 at 67-68. Ca 473c-473d.

20

provision does not ensure that the same level of service currently provided to uninsured residents

at Coney Island Hospital will be maintained under PHS-NY, nor does it guarantee that the health

care needs of future indigent residents will be met. Id. Because the sublease sets forth PHS-NY's

charity care obligation in dollar terms, the actual number of patients that PHS-NY will treat up to

the trigger point will depend solely upon the method of cost calculation used by PHS-NY. While

the sublease does not specify how PHS-NY will calculate its charity care expense, Comptroller

Hevesi, after examining a number of transaction documents, ascertained that this expense "will be

calculated on the basis of PHS-NY's fee schedule, rather than its actual costs." See Hevesi,

Fundamental Issues at 1-2 (emphasis supplied). Ca 606-07. If, in fact, PHS-NY calculates charity

care costs allocable to the cap by subtracting any payments from its own standard charges (as

opposed to HHC’s method of calculating its charity care expense based on its actual costs), it will

have higher charity care expenses than HHC,' and the volume of service provided by PHS-NY will

in fact be lower than that currently provided. See id.

More importantly, after the first year that the trigger point is exceeded, PHS-NY will no

longer be obligated to provide indigent care above that cap. The proposed sublease explicitly

permits PHS-NY to "manage access to health care in such a manner as it may deem appropriate so

as to avoid ‘Excess Incurrence’" of indigent care 1f the costs of providing indigent care services

exceed PHS-NY's cap in any given year. Proposed Sublease § 28.05(c). Ca 473k. Moreover, the

sublease also explicitly states that after the first year in which PHS-NY reaches the trigger point,

HHC cannot require PHS-NY to provide indigent care beyond that point: "[N]othing herein shall

** According to Comptroller Hevesi, calculations based on a fee schedule rather than on

actual costs will result in higher expense because fees charged are normally higher than costs.

Hevesi, Fundamental Issues at 2. Ca 607.

21

give Landlord [HHC] the right to require Tenant [PHS-NY] to provide Indigent Care in excess of

such amount." Id. With the exception of a single year of reimbursement guaranteed by HHC (for

which the City has ostensibly promised to reimburse the Corporation), there is no articulated plan

either for the provision of services to this population or for the payment of the costs attendant to such

care.”

With respect to the costs incurred in providing such services above the established charity

care level, under the proposed sublease, PHS-NY is only required to absorb the costs of such care

up to the trigger point. After the trigger point is reached, however, HHC will be obliged to

reimburse PHS-NY for all costs incurred above that point for only one year. Proposed Sublease §

28.05(c). Ca 473k. Although the City has represented that it will reimburse HHC for such outlays,

there is no provision detailing how such expenditures will be budgeted and what impact they might

have both on HHC's annual budgeting process and on the allocation of funds among HHC's other

facilities. Nor is there any binding document setting forth the City’s commitment to HHC on this

fiscal issue.

PHS-NY's Control Over The Continuation Of Existing Services

Similarly lacking in the sublease is any delineation of the specific medical services to be

provided by PHS-NY or the entities that will provide these services. The proposed sublease

distinguishes between "Core" services and "Non-core" services. Proposed Sublease § 28.01(a). Ca

473c-473d. Under Article 28, PHS-NY would continue to provide "core" services, including

“If PHS-NY turns away patients so as to avoid exceeding the contractual cap, HHC will

still be required to fund the costs of such care at other municipal facilities. This would require

HHC to divert resources from other institutional facilities, which would in turn affect the ability

of those institutions to carry out their stated missions of delivering care to all regardless of ability

to pay.

22

"Emergency Medicine, Medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, Rehabilitation

Medicine and General Surgery," "to substantially the same degree as provided by Coney Island

Hospital on the day prior to Commencement Date." Proposed Sublease § 28.01(a). Ca 473d.

However, this list of "core services” merely designates various departments of the Hospital;

it does not specify the services that PHS-NY must continue to provide in each department.

Similarly, there is no clue as to which of the Hospital's 90 out-patient clinics (including allergy,

asthma, diabetes, cardiac rehabilitation, out-patient surgery, hearing, geriatrics continuing care, pre-

natal, alcoholism, and family planning clinics, for example) PHS-NY must continue to operate.

Moreover, because PHS-NY will only be obligated to continue those services that are being offered

at the time that it assumes operating responsibility, no assessment can be made of the impact of any

possible service cuts on the affected communities.

The proposed sublease also permits PHS-NY both to change the ways and means of

delivering these "core" department, and to alter the specific services offered within them. PHS-NY

thus can close a "core" department altogether for certain articulated reasons -- i.e. changes in

government reimbursement mechanisms -- without getting HHC's approval. Proposed Sublease §

28.01(b). Ca 473d. PHS-NY can also close “core” departments if it deems the closure to be a

“reasonable” response to "changes in health care practices, changes in the health care needs of the

Coney Island community," or "fundamental changes in government reimbursement mechanisms, or

other fundamental changes which materially affect the delivery of health care services." Proposed

Sublease § 28.01(b). Ca 473d.

The proposed sublease similarly permits PHS-NY to change the ways and means of

delivering "non-core" services (which include dental care, cardiology, urology, endocrinology,

ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, podiatry, anesthesiology, oral surgery, cardiac cath, pharmacy,

23

surgical subspecialties and all other services not listed as "core" services) at PHS-NY's "reasonable

discretion." Proposed Sublease § 28.01(a) and (c). Ca 473d. Under this provision, PHS-NY can

close or transfer any non-core service without any effective limitation. Before doing so, PHS-NY

need only give HHC notice; HHC is provided with no recourse should PHS-NY reject its

recommendation.

Finally, the sublease would allow PHS-NY to transfer responsibility for performing inpatient

and outpatient "non-core" services to other providers without garnering any assurance that such

providers will accept referred patients without regard for their ability to pay. No assurance is

required regarding the accessibility of services to uninsured patients when they are referred to private

providers (e.g., for lab work or private practices for follow-up patient care). These provisions could

seriously jeopardize the continuity of care for the chronically ill, for diabetics, asthmatics or persons

living with AIDS.

Primary’s Troubling Health Care Record

Finally, contrary to the documents concerning Primary’s background submitted by

Appellants in the Record, Ca 473bb et seq., the documentation provided by Primary as well as

reports filed by HHC's own staff based on their initial reviews of Primary’s current operations, raise

significant troubling questions regarding both quality of care and access to care at Primary’s

Cleveland hospitals. Ca 617. According to data provided by Primary, for the years 1993 through

1996, total levels of uncompensated care have dropped significantly since Primary assumed control

of these facilities. Ca 609. A report by Comptroller Hevesi that relies on figures supplied by

Primary shows significant declines in the amount of care provided to the uninsured working poor

and total uncompensated care, after Primary assumed control of two of the hospitals, St. Alexis and

24

Deaconess.” Ca 609. According to Dr. Walid Michelen, Senior Vice President for Medical &

Professional Affairs for HHC, St. Alexis hospital performed worse than expected in its most recent

survey in the areas of patient satisfaction, mortality, and length of stay. Ca 643-645. Dr. Michelen

was also informed that both Deaconess and St. Alexis Hospitals "subtly" turn away indigent care

patients. Ca 644. Initsreview of Primary’s current operations, HHC staff raised concerns regarding

Primary’s practice of discontinuing and outsourcing services. Ca 485-88.

The Discontinuation Of Funding For Charity Care Services

In their analysis of PHS-NY’s assumption of HHC’s indigent care responsibilities,

Appellants have apparently failed to consider the likely unavailability of funds from certain portions

of the New York State Bad Debt and Charity Care Pools which have in the past defrayed nearly 50

percent of the annual cost to HHC of providing charity care. According to Comptroller Hevesi, if

PHS-NY takes over operation of Coney Island Hospital, the Hospital will no longer be eligible for

funds from two pools of the New York State Bad Debt and Charity Care Pools -- the Supplementary

Pool and the Supplementary Low Income Program Adjustment Pool -- because these funds are

available only to government hospitals.>* Hevesi, Fundamental Issues at 17. Ca 622.

Even HHC's own numbers illustrate the importance of this factor.”> The Environmental

** According to the Comptroller’s analysis, care for the uninsured working poor dropped

by 30 percent at St. Alexis Hospital, and by 39 percent at Deaconness Hospital. The

Comptroller’s analysis also finds a significant decline in the total uncompensated care provided

at both of these hospitals: 17 percent at St. Alexis, and 47 percent at Deaconess. Hevesi,

Fundamental Issues at 4. Ca 609.

**The Draft Memorandum of Understanding between HHC, PHS-NY, and the City, also

states that "due to the sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY, Coney Island Hospital will

no longer participate in the public hospital pools.”

**While PHS-NY will continue to be obligated to provide care up to the trigger point, as

the analysis below illustrates, it will reach the trigger point more quickly if it is not eligible for

25

Assessment Form (“EAF”) published by the City pursuant to the City Environmental Quality

Review (“CEQR?”), 62 Rules of the City of New York ("RCNY") §§ 5-01 et seq. & Appendix A,

projects that the trigger point, above which HHC must absorb the costs of charity care, will be

$18,825,500, EAF at C-20; Ca 561, and that the number of uninsured will reach 37,100 by the year

2000 (a figure which Respondents contest as a serious underestimation). HHC assumes that PHS-

NY's cost of providing care for this number of patients will be $19,807,700.>° It also assumes that

PHS-NY will be reimbursed, and that its charity care expenses will be reduced by $9 million to

$10,307,700. EAF at C-21; Ca 562. If PHS-NY proves to be ineligible for reimbursement from

some of the Bad Debt and Charity Care Pools, however, PHS-NY's reimbursement may be reduced

by up to $7.5 million.” PHS-NY's contractual contribution to charity care will thus reach trigger

point well before it has served the number of patients that HHC has served in previous years.

Furthermore, HHC also fails to take into account the fact that the sublease allows PHS-NY

to choose its method of cost calculation. Because the sublease sets forth PHS-NY's charity care

obligation in dollar terms, the actual number of patients PHS-NY treats will depend solely upon the

method of cost calculation used by the company. If PHS-NY calculates charity care costs allocable

to the cap by subtracting any payments from its own standard charges (as opposed to the HHC

method of expenses minus revenues), the volume of service may in fact be lower than that currently

provided for this reason as well. Moreover, HHC staff has noted that Primary has a practice of

these funds. After PHS-NY has exceeded the trigger point for one year, in all future years, 1t will

be entitled to turn people away once the cap is reached. Proposed Sublease $23.05(c). Ca

473(k).

**Plaintiffs also challenge this number, which assumes without basis that PHS-NY's

calculations of cost will be identical to Coney Island Hospital's current calculation.

*"Hevesi, Fundamental Issues at 17. Ca 622.

26

outsourcing and spinning off services such as emergency services, radiology, pharmacy, and

dietary.”® If PHS-NY adopts this practice, it will charge separately for such services as X-rays and

lab tests, in contrast to Coney Island Hospital's current practice of charging all-inclusive rates. This

will allow PHS-NY to increase substantially the costs of charity care. Nowhere are either of these

limitations on PHS-NY’s assumption of charity care responsibilities analyzed, nor is the fact that the

sublease fails to provide a mechanism for auditing PHS-NY's method of calculating costs taken into

account.

The Proceedings Below

In March 1996, the New York City Council (the “Council”’) commenced an action against

Appellants in Queens County Supreme Court challenging the Mayor’s hospital privatization plan.

In May 1996, Respondents filed a similar suit in the same court. Both Retonters and the Council

sought a declaration that Appellants had violated § 197-c of the New York City Charter (the Uniform

Land Use Review Procedure or “ULURP”) and § 7385(6) of the HHC Act by failing to obtain

Council approval of the proposed long-term subleases. Both Respondents and the Council also

sought a permanent injunction prohibiting HHC’s sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY.

After the HHC Board of Directors approved the Coney Island Hospital sublease, plaintiffs

in both actions amended their complaints to allege that the proposed sublease constituted an ultra

vires act by HHC.

By order and judgment entered February 5, 1997, the Supreme Court (Posner, J.) granted

summary judgment to Respondents and the Council, declaring: (1) that HHC’s proposed sublease

of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY was ultra vires under the HHC Act; and (2) that the proposed

**See EAF (HHC Staff Concerns) Ca 484-505.

27

sublease required the Council’s approval under both ULURP and the HHC Act.

By per curiam opinion dated September 15, 1997, the Appellate Division, Second

Department, affirmed the Supreme Court’s decision insofar as the lower court had found the

proposed sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY to be ultra vires, but deleted those portions

of the decision holding that the proposed sublease required the Council’s approval under both

ULURP and the HHC Act.

OPINIONS BELOW

The Trial Court Opinion

The Queens County Supreme Court (Posner, J.) entered judgment on February 5, 1997

denying Defendants motion for summary judgment and granting Plaintiffs’ cross-motion for

summary judgment. In granting summary judgment for Plaintiffs, the Supreme Court held that:

(1) the HHC Act precludes the dismantling of the HHC system generally, and the long-term sublease

of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY, specifically; (2) any lease of an HHC facility must be

approved pursuant to the City Charter Uniform Land Use Review Procedure; and (3) any lease of

an HHC facility must be approved by the City Council.

Specifically, the court first rejected Defendants’ argument that the City Council had no

authority to review the land use implications of decisions made by HHC. The court noted that the

HHC Act ensured the City's continuing control over its real property by requiring consent from the

Board of Estimate prior to the disposition of a health facility or any other real property of the City.

When the HHC Act was passed, the Board of Estimate was vested with the authority under the City

Charter to consider both the business terms and the land use effects of any disposition of the City's

property. After the demise of the Board of Estimate, the City Charter divided that authority: the

Mayor was granted authority to approve the business terms of any disposition of City property and,

28

through ULURP, the City Council was granted the authority to review the land use implications of

any such disposition. Following this clear devolution of power to the two branches of City

government, the Supreme Court concluded that the only interpretation of the HHC Act consistent

with its language and its purposes is one which conforms to the City Charter revisions: the authority

to consent to business terms lies with the Mayor and the authority to review the land use implications

lies with the City Council through ULURP. Ca 854.

With regard to the ultra vires claim, the court found that the language of the HHC Act and

the history surrounding its enactment made clear that the State Legislature created HHC as a public

benefit corporation to assume the governmental function of operating the public hospitals and fulfill

the City’s constitutional obligation to provide health and medical services to residents that cannot

afford such care. In so concluding, the court rejected Defendants’ attempt to read narrow provisions

of the Act permitting HHC to contract for the provision of specific health care services to allow the

wholesale delegation of all of HHC’s operational and management responsibilities to a private, for

-profit corporation. Such a reading, the court noted, would clearly frustrate the purposes of the Act.

The Appellate Division Opinion

On appeal, the Appellate Division, Second Department, by order dated September 8, 1997,

affirmed, without dissent, that portion of the Supreme Court’s decision which held that the hospital

privatization plan and the proposed sublease of Coney Island Hospital constituted an ultra vires act.

The court, however, modified the judgment of the Supreme Court by deleting those provisions that

declared the sublease subject to ULURP and the approval of the City Council.

29

ARGUMENT

I. THE HHC ACT DOES NOT AUTHORIZE HHC TO DELEGATE ITS

ADMINISTRATIVE, MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONAL DUTIES

REGARDING THE PUBLIC HOSPITALS THROUGH A SALE OR LONG-TERM

SUBLEASE TO A PRIVATE, FOR-PROFIT CORPORATION

A. The Transfer of Administrative, Management, and Operational Control Over

A Public Hospital to a Private, For-Profit Corporation Is Plainly Inconsistent

With HHC’s Corporate Purposes

The HHC Actmust receive "a sensible and practical over-all construction, which is consistent

with and furthers its scheme and purpose," Long v. Adirondack Park Agency, 76 N.Y.2d 419, 420,

559 N.E.2d 635, 636-37, 559 N.Y.S.2d 941, 942-43 (1990), in light of the "general rule in the

construction and interpretation of statutes that the intent of the legislature is the primary object

sought and [that] . . . courts do not favor a departure from literal construction." American Dock Co.

v. City of New York, 21 N.Y.S.2d 943, 952, 174 Misc. 813 (1940). The construction advanced by

Appellants violates these and other well established canons of statutory construction.

In urging this Court to reverse the Appellate Division and uphold the sublease of Coney

Island Hospital to PHS-NY, Appellants primarily rely on § 7385(6) of the HHC Act, which

authorizes HHC “to dispose of by sale, lease or sublease, . . . a health facility . . . for its corporate

purposes.” HHC Act § 7385(6) (emphasis supplied). App. Br. at 17. Their reliance on § 7385(6)

is entirely misplaced, however, since the transfer of full administrative, management and operational

control over one of the City’s public hospitals to a private, for-profit corporation is plainly

inconsistent with HHC’s “corporate purposes.”

This is nowhere more evident than in the statement of legislative policy that begins the HHC

Act. In enacting the HHC Act, the State Legislature declared that:

hospitals and other health facilities of the city are of vital and paramount concern and

essential in providing comprehensive care and treatment for the ill and infirm, both physical

30

and mental, and are thus vital to the protection and the promotion of the health, welfare and

safety of the people of the state of New York and the city of New York.

HHC Act § 7382 (emphasis supplied). To this end, the Legislature mandated the City to enter into

an agreement with the newly created HHC “whereby [HHC] shall operate the hospitals then being

operated by the city for the treatment of acute and chronic diseases . . . .” HHC Act § 7386(1)(a)

(emphasis supplied). Thus, as the Appellate Division observed, “[tlhe Legislature clearly

contemplated that the municipal hospitals would remain a governmental responsibility and would

be operated by HHC as long as HHC remained in existence.” Council of City of New York v.

Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 181, 662 N.Y.S.2d 516, 518 (2d Dept. 1997). “It is fundamental that

a court, in interpreting a statute, should attempt to effectuate the intent of the Legislature.”

Majewski v. Broadalbin-Perth Central School Dist., 91 N.Y.2d 577, 583, 673 N.Y.S.2d 966, 968

(1998) (quoting Patrolmen’s Benevolent Ass’n v. City of New York, 41 N.Y.2d 205, 208, 391

N.Y.S.2d 544, 546 (1976)). Given the State Legislature’s clearly expressed intent to have HHC

“operate” the public hospitals and ensure the provision of dignified health care services to the City’s

indigent and uninsured residents, it cannot be credibly argued that transfer of administrative,