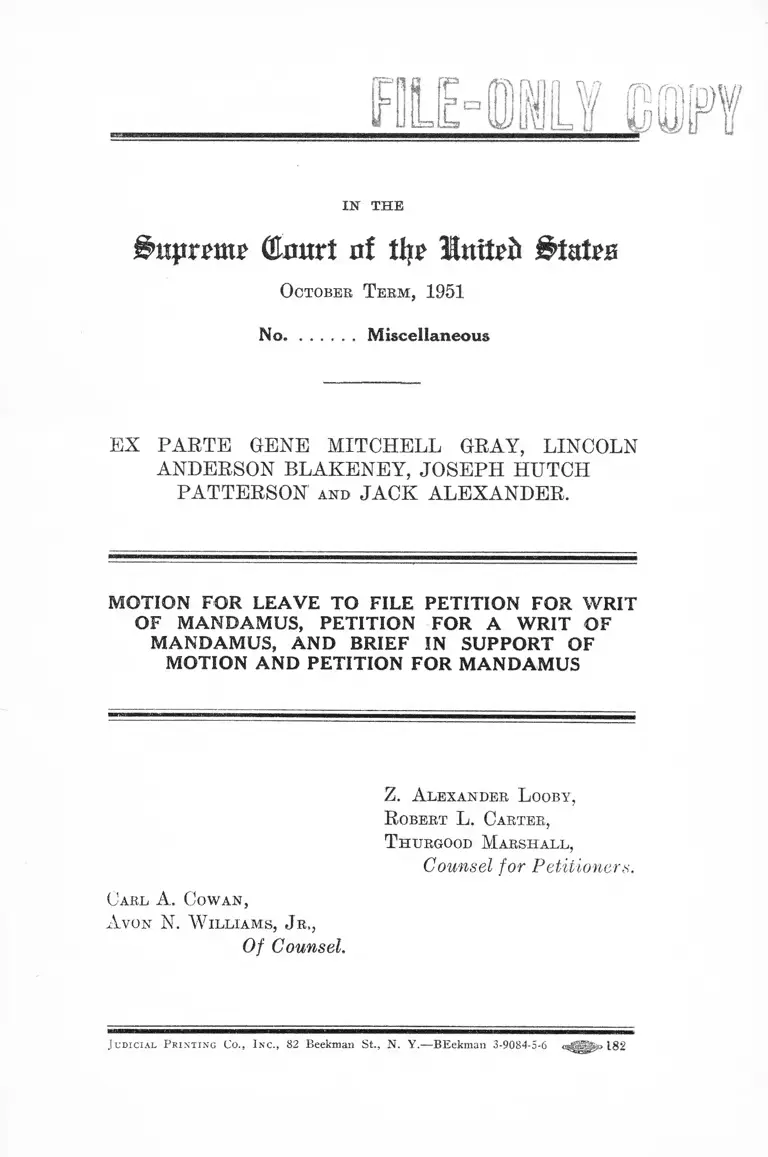

Ex Parte Gene Mitchell Gray Motion for Leave to File and Petition for Writ of Mandamus; Brief in Support of Motion and Petition for Mandamus

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ex Parte Gene Mitchell Gray Motion for Leave to File and Petition for Writ of Mandamus; Brief in Support of Motion and Petition for Mandamus, 1951. 696cfe1a-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/613a2392-9056-4896-961b-ab31878757db/ex-parte-gene-mitchell-gray-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-petition-for-writ-of-mandamus-brief-in-support-of-motion-and-petition-for-mandamus. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Qkmrt nf % Itttteft States

October T erm, 1951

No.............. Miscellaneous

EX PARTE GENE MITCHELL GRAY, LINCOLN

ANDERSON BLAKENEY, JOSEPH HUTCH

PATTERSON a n d JACK ALEXANDER.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION FOR WRIT

OF MANDAMUS, PETITION FOR A WRIT OF

MANDAMUS, AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION AND PETITION FOR MANDAMUS

Z. Alexander L ooby,

R obert L. Caster,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Carl A. Cowan,

A von N. 'Williams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

J udicial Printing Co., I nc., 82 Beekman St., N. Y.—BEekman 3-9084-5-6 182

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File a Petition for Writ of Man

damus .............................. ............. .......................... 1

Petition for Writ of Mandamus to the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee,

Northern Division, to the Honorable Shackelford

Miller, Jr., Judge, United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit, the Honorable Leslie R. Darr

and the Honorable Robert L. Taylor, Judges of the

United States District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Tennessee ..................................................... 3

Brief in Support of Motion and Petition for Writ of

Mandamus ..................................................... 9

Opinions Below ....................................................... 9

Jurisdiction ............................................................. 9

Questions Presented................................................ 10

Statutes Involved.................................................... 11

Statement ................................................................ 12

Argument:

This Court may properly issue a Writ of Man

damus directing a district court of three

judges to determine petitioner’s right to in

junctive relief applied for pursuant to Title

28, United States Code, Section 2281 ............ 14

Conclusion .............................................................. 16

Appendices .............. 19

11 I N D E X

Cases Cited

PAGE

Driscoll v. Edison Light and Power Co., 307 U. S. 104. 15

Eichholz v. Public Service Commission, 306 U. S. 268. 15

Ex parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354, 355 ...................... . 15

Ex parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565, 566 ............................. 15

Ex parte Metropolitan Water Co., 220 U. S. 539 ......... 14

Fleming v. Rhodes, 331 U. S. 100 ................................. 15

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 . . . . . . . . 15

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337 ......... 15

Modern Woodmen of America v. Casados, 15 F. Supp.

483 (D. C. New Mexico, 1936) ................................... 14

Oklahoma Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing

Co., 292 II. S. 386 ....................................................... 16

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290.. 15

Osage Tribe of Indians v. Ickes, 45 F. Supp. 178, 186,

187 (D. C., 1942) .......................................................... 16

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ................................. 15

Public National Bank of New York, 278 U. S. 101....... 16

Query v. United States, 316 U. S. 486 .......................... 15

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631.................... 15

Smith v. Wilson, 273 U. S. 388 ..................................... 16

Stratton v. St. Louis Southwest Railway Co., 282 U. S.

10, 16 ........................................................................15,16

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 .. ............................... 15

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 94 L. ed. (Ad. Op.)

200 ............................................................................... 15

i n d e x 111

Statutes Cited

PAGE

Code of Tennessee, Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397.. 5,11,

12,14,15

Constitution of the State of Tennessee, Article 11,

Section 1 2 ..............................................5,10,11,12,14,15

Title 28, United States Code:

Section 1253 ....................

Section 1331 ....................

Section 1343 ....................

Section 1651(a) ...............

Section 2101(b) ...............

Section 2281 ....................

Section 2284 ....................

.7,10,16

. . . . 5

. . . . 5

. . . . 9

. . . . 6

..7,10,12,13,14,15

.............5,10,13,15

IN THE

i l u t p n w G k m r t i\}t H u t t e i i

October T erm, 1951

No.............. Miscellaneous

Ex P arte Gene Mitchell Gray, L incoln A nderson

Blakeney, J oseph H utch P atterson and

J ack Alexander.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A PETITION FOR

WRIT OF MANDAMUS

To the Honorable Frecl M. Vinson, Chief Justice of the

United States, and to the Honorable Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the United States:

Petitioners move the Court for leave to file the petition

for writ of mandamus hereto annexed; and further move

that an order and rule be entered and issued directing the

Honorable, the United States District Court for the East

ern District of Tennessee, Northern Division, the Honor

able Shackelford Miller, Jr., Circuit Judge of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, the Honor

able Leslie R. Darr and the Honorable Robert L. Taylor,

Judges of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Tennessee to show cause why a writ of man

damus should not be issued against them in accordance

with the prayer of said petition, and why your petitioners

2

should not have such other and further relief in the prem

ises as may be just and meet.

Z. Alexander L ooby,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Motion for Leave to File a Petition for

Writ of Mandamus

Carl A. Cowan,

Avon N. W illiams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

3

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October T erm, 1951

No..............Miscellaneous

---------- mm > — ■ ----------

Ex P arte Gene Mitchell Gray, L incoln A nderson

Blakeney, J oseph H utch P atterson and

J ack Alexander.

----------- — i » ------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS TO THE UNITED

STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DIS

TRICT OF TENNESSEE, NORTHERN DIVISION, TO THE

HONORABLE SHACKELFORD MILLER, JR., JUDGE,

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH

CIRCUIT, THE HONORABLE LESLIE R. DARR AND THE

HONORABLE ROBERT L. TAYLOR, JUDGES OF THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

To the Honorable Frecl M. Vinson, Chief Justice of the

United States, and to the Honorable Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the United States:

The petitioners respectfully show the following:

1. Petitioner, Gene Mitchell Gray, applied for admis

sion to the University of Tennessee, such application being

for registration and enrollment in the graduate school on

the first day of the 1950 fall quarter. Petitioner, Joseph

Hutch Patterson, applied for admission to the University

of Tennessee, Iris application being for registration and en

rollment on the first day of the 1951 winter quarter. Peti

4

tioners, Lincoln Anderson Blakeney and Jack Alexander,

sought permission to enroll in the law school of the Uni

versity of Tennessee on the first day of the 1951 winter

quarter.

2. Petitioners are citizens of the United States and of

the State of Tennessee. They meet all lawful qualifications

requisite for admission to the University to pursue the

courses of study for which they applied, and their applica

tions would have been accepted except for the fact that

petitioners are Negroes.

3. The University of Tennessee is state owned and

operated and is the only state institution where petitioners

can receive the educational facilities, opportunities and

advantages which they are seeking.

4. The Board of Trustees of the University of Ten

nessee met on December 4, 1950 and refused to admit

petitioners to the University of Tennessee because they

are Negroes. This action was taken in a formal order which

reads as follows:

“ Whereas, the Constitution and the Statutes of

the State of Tennessee expressly provide that there

shall be segregation in the education of the races in

schools and colleges in the State and that a viola

tion of the laws of the State in this regard subjects

the violator to prosecution, conviction and punish

ment as therein provided; and,

“ Whereas, this Board is bound by the Constitu

tional provision and the acts referred to;

“ Be it therefore resolved, that the applications

by members of the Negro race for admission as

students into The University of Tennessee be and

same are hereby denied.”

Petition for Writ of Mandamus

5

Petition for Writ of Mandamus

5. Petitioners thereupon filed a complaint in. the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee

pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Sections 1331,

1343 and 2281 seeking a preliminary and permanent in

junction restraining the university officials from refusing

to admit them to the University of Tennessee because of

their race and color, and from enforcing Article 11, Sec

tion 12 of the Constitution of Tennessee, Sections 11395,

11396, 11397 of the Code of Tennessee, and the December

4, 1950 order of the Board on the grounds that enforce

ment of the Constitution, statutes and order was uncon

stitutional in that petitioners were thereby denied the

equal protection of the laws as guaranteed under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

6. In the answer tiled on behalf of the University, it

was admitted that petitioners’ applications had been re

fused pursuant to Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution

and Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code of Ten

nessee, which made it unlawful for Negro and white

students to attend the same schools. No question was

raised with respect to petitioners’ qualifications, and it

was not denied that the University of Tennessee was the

only state institution offering the courses of study peti

tioners desired to pursue. Whereupon, petitioners filed

a motion for judgment on the pleadings.

7. A special three-judge district court was convened

pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section 2284,

and a hearing before such court was held in Knoxville,

Tennessee on March 13, 1951. 8

8. On April 13, 1951, this specially constituted court

rendered an opinion in which it held that the issues in-

6

volved in the case were not appropriate for disposition by

a three-judge court and ordered the court dissolved. Its

order reads in part as follows:

“ * * * the two Judges designated by the Chief

Judge of the Circuit to sit with the District Judge,

in whose District the action was filed, do now with

draw from the case, and that the case proceed be

fore said District Judge in the District of its filing.” 3

9. On April 20, 1951 the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Tennessee, Northern Division,

without further hearing handed down an opinion in which

it was held that petitioners had been denied the equal

protection of the laws, and that they were entitled to be

admitted to the University of Tennessee. The court, how

ever, refused to issue an injunctive decree stating:

“ Believing that the University authorities will

either comply with the law as herein declared or take

the case up on appeal, the Court does not deem an

injunctive order presently to be appropriate. The

case, however, will be retained on the docket for

such orders as may seem proper when it appears

that the applicable law has been finally declared”

97 P. Supp. 463.1 2

10. Petitioners, believing that their applications for

temporary and permanent injunctions to enjoin the Uni

versity officials from barring their admission to the Uni

versity pursuant to the state constitution, statutes and

order of the Board of Trustees required decision by a dis

trict court of three judges and that the order of April 13th

dissolving the district court constituted a denial of their

application, appealed to this Court pursuant to Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 1253 and 2101(b). Such ap

peal is now pending before this Court as case No. 120.

Petition for Writ of Mandamus

1. The opinion and order are set forth in Appendix A.

2. The opinion of the Court is set forth as Appendix B.

11. Either the order of April 13, 1951, in which the dis

trict court of three judges refused to take any action on

petitioners’ application for a temporary and permanent

injunction, on the grounds that the cause was not appro

priate for their determination, constitutes a denial of the

application for a temporary and permanent injunction

within the meaning of Title 28, United States Code, Section

1253, and direct appeal to this Court is appropriate.

12. Or the order of April 13, 1951 involves refusal by

the court below to perform a mandatory act required by

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281, and petitioners

must seek the issuance of a writ of mandamus from this

Court.

7

Petition for Writ of Mandamus

W herefore, petitioners pray that in the event that

petitioners’ direct appeal in case No. 120 is considered

improper and is denied, a writ of mandamus issue from

this Court directed to the Honorable the United States Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee, Northern

Division, the Honorable Shackelford Miller, Jr., Circuit

Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit, the Honorable Leslie R. Darr and the Honorable

Robert L. Taylor, Judges of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee to show cause

on a day to be fixed by this Court why mandamus should

not issue from this Court directing said Honorable Shackel

ford Miller, Jr., Circuit Judge of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and the Honorable Leslie

R. Darr and the Honorable Robert L. Taylor, Judges of the

United States District Court to vacate and expunge from

the record and the order of April 13, 1951 dissolving the

three-judge court and the subsequent action of Honorable

Robert L. Taylor in which he proceeded to pass upon the

issues involved in this case.

8

Petition for Writ of Mandamus

That petitioners have such additional relief and process

that may he necessary and appropriate in the premises.

Respectfully submit ted,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Cakl A. Cowan,

Avon N. W illiams, J b.,

Of Counsel.

IN THE

fihtprniu' (Enurt nf tiii> llnitrii &tata

October T erm, 1951

No..............Miscellaneous

_____----- ■ <i—- ----------- -

Ex P arte Gene M itchell Gray, L incoln A nderson

Blakeney, J oseph H utch P atterson and

J ack A lexander,

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION AND PETITION

FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS

Opinions Below

The opinion and order of the United States District

Court, entered April 13, 1951, dissolving the specially con

stituted three-judge District Court which heard this cause

is unreported and is appended hereto as Appendix A.

The opinion of the United States District Court, of April

20, 1951, which held that petitioners were entitled to be

admitted to the University of Tennessee but which refused

to grant injunctive relief is reported in 97 F. Snpp. 463

and is appended hereto as Appendix B.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1651 (a) since the ordinary

remedy of appeal and certiorari may be unavailable and

[ 9 ]

1 0

inadequate, and petitioners ’ right to take an appeal in this

case, pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section 1253

is beclouded with doubt.

Questions Presented

1. Whether, after notice and hearing, the Honorable

Shackelford Miller, J r., Circuit Judge of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, the Honor

able L eslie R. Darr, and the Honorable R obert L. T aylor,

Judges of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Tennessee, in issuing the order of April 13,

1951 dissolving the specially-constituted three-judge court

on the grounds that the issue was not appropriate for

decision by a three-judge court under the provisions of

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281, failed to per

form the ministerial duties of their office as required under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281 and 2284.

2. Whether the Honorable R obert L. T aylor, who

ruled on April 20, 1951 that petitioners were entitled to

be admitted to the University of Tennessee but who refused

to grant injunctive relief, exceeded his jurisdiction in view

of the fact that the disposition of the case herein required

action by a district court of three judges.

3. Whether this Court should issue a mandate order

ing the Honorable Shackelford Miller, J r., Circuit Judge

of tiie United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit, the Honorable L eslie R. Dark and the Honorable

R obert L. T aylor, Judges of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee to make a final

determination of petitioners’ application for a temporary

and permanent injunction to enjoin the University officials

from refusing to admit them to the University of Tennessee

and from enforcing Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitu

11

tion of tlie State of Tennessee, Sections 11395, 11396, 11397

of the Code of Tennessee, and the December 4, 1950 order

of the Board of Trustees on the grounds that such enforce

ment constitutes an unconstitutional deprivation of peti

tioners’ rights.

Statutes Involved

The statutory provisions involved in this ease are as

follows:

Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution of the State

of Tennessee reads as follows:

“ * * * And the fund called the common school

fund, and all the lands and proceeds thereof * * *

heretofore by law appropriated by the General

Assembly of this State for the use of common

schools, and all such as shall hereafter be appro

priated, shall remain a perpetual fund, * * * and

the interest thereof shall be inviolably appropriated

to the support and encouragement of common schools

throughout the State, and for the equal benefit of

all the people thereof. * * * No school established

or aided under this section shall allow white and

negro children to be received as scholars together

in the same school. * * *”

Section 11395 of the Code of Tennessee reads as

follows:

“ * * * It shall be unlawful for any school,

academy, college, or other place of learning to allow

white and colored persons to attend the same school,

academy, college, or other place of learning.”

Section 11396 of the Code of Tennessee reads as

follows:

“ * * * It shall be unlawful for any teacher, pro

fessor, or educator in any college, academy, or

1 2

school of learning, to allow the white and colored

races to attend the same school, or for any teacher

or educator or other person to instruct or teach

both the white and colored races in the same class,

school, or college building, or in any other place or

college building, or in any other place or places of

learning, or allow or permit the same to be done

with their knowledge, consent or procurement.”

Section 11397 of the Code of the State of Tennessee

reads as follows:

“ * * * Any person violating any of the provi

sions of this article, shall be guilty of a mis

demeanor, and, upon conviction, shall be fined for

each offense fifty dollars, and imprisonment not less

than thirty days nor more than six months.”

Statement

Petitioners applied for admission to the graduate and

professional schools of the University of Tennessee. They

met all the requirements for admission thereto except for

the fact that they are Negroes. The University of Ten

nessee is the only institution maintained and operated by

the state which offers the courses of study which petitioners

desire to pursue.

On December 4, 1950 the Board of Trustees of the

University of Tennessee issued a formal order in which it

denied petitioners’ applications for admission to the

University on the grounds that to admit them would be

violative of the Constitution and statutes of the State.

Petitioners filed a complaint, pursuant to Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281, to restrain the enforcement of

Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution of Tennessee;

Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code of Tennessee

and the December 4, 1950 order of the Board of Trustees

13

on the grounds that such enforcement constituted an un

constitutional deprivation of petitioners’ rights.

The University, in answer to petitioners’ complaint,

admitted that their applications had been refused pursuant

to the Constitution and statutes of the State of Tennessee.

Petitioners thereupon filed a motion for judgment on the

pleadings.

A three-judge district court convened, in accordance

with Title 28, of the United States Code, Sections 2281

and 2284, and met in Knoxville, Tennessee on March 13,

1951 for a hearing on the cause. On April 13, 1951 that

court held that the issues raised in petitioners’ complaint

were not appropriate for decision by a three-judge court

and ordered the matter to proceed before the District

Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Tennessee, Northern Division, in which suit

was filed. That court subsequently handed down an opinion

holding that petitioners were entitled to be admitted to

the University of Tennessee, but injunctive relief was

refused on the grounds that the University officials would

either comply with the law or would take an appeal. As

of now, petitioners have not been admitted to the Univer

sity of Tennessee nor have the University officials given

any indication that petitioners will be admitted except

under court mandate.

14

ARGUMENT

This Court may properly issue a Writ of Man

damus directing a district court of three judges to

determine petitioner’s right to injunctive relief ap

plied for pursuant to Title 28, United States Code,

Section 2281.

Petitioners were here refused admission to the

University of Tennessee solely because of their race and

color, pursuant to the December 4, 1950 order of the Board

of Trustees of the University. This order was based on

Article 11, Section 12 of the State Constitution and Sec

tions 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code of Tennessee,

which make it unlawful for Negro and white students to be

educated together in the same school. Petitioners sought

an injunction against enforcement of these provisions on

the grounds that such enforcement deprived them of the

equal protection of the laws, and hence that Article 11,

Section 12 of the Constitution of Tennessee, Sections 11395,

11396 and 11397 of the Code of Tennessee and the Decem

ber 4,1950 order of the Board of Trustees of the University

were unconstitutional as applied. Thus the cause was

brought squarely under the provisions of Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281, and a prima facie case for

determination by a district court of three-judges was

presented, Modern Woodmen of America v. Gasados, 15

F. Supp. 483 (D. C. New Mexico 1936) ; Ex parte Metropoli

tan Water Co., 220 U. S. 539. The University officials, in

their defense to petitioners’ complaint, admitted that

petitioners had been denied admission to the University

pursuant to the state’s constitutional provisions and

statutes, enforcement of which petitioners were seeking

to enjoin, which forbade the commingling together of

Negro and white students in the same schools.

There can no longer be any doubt that Negro applicants

must be accorded educational opportunities and advantages

15

under the same terms and conditions as these opportunities

and advantages are afforded white students, and at the

same time. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631; Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin x. Board of Regents, 339

LT. S. 637; and Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 91 L. ed.

(Ad. Op.) 200, have made it clear that any form of racial

segregation practiced at the professional and graduate

school levels of state universities violates the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Here, how

ever, the University of Tennessee was the only state insti

tution offering the courses which petitioners desired to

pursue. Under these circumstances, without regard to the

present constitutional vitality of the “ separate but equal’’

doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. 537, with respect

to graduate and professional education, Article 11, Section

12 of the Constitution of Tennessee and Sections 11395.

11396 and 11397 of the Code of Tennessee are unconstitu

tional as applied, in that pursuant to their provision peti

tioners were prohibited from being admitted to the Univer

sity of Tennessee, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra.

and petitioners are entitled to injunctive relief against un

constitutional enforcement of these provisions, McLaurin

v. Board of Regents, supra. Petitioners’ cause, there

fore, properly required adjudication by a district court of

three judges, Fleming v. Rhodes, 331 U. S. 100; McLaurin

v. Board of Regents, supra; Driscoll v. Edison Light and

Power Co.. 307 U. S. 104;. Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v.

Russell, 261 U. S. 290; Eichhols v. Public Service Commis

sion, 306 U. S. 268; Query v. United States, 316 U. S. 486.

It is clear that petitioners would have been entitled to

a writ of mandamus from this Court had the court below

refused to convene a district court of three judges as pro

vided in Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281 and

2284. Ex parte Collins, Til U. S. 565, 566; Ex Parte B ra d

ford, 310 IT. S. 354, 355; Stratton v. St. Louis Southwest

16

Railway Co., 282 TJ. S. 10, 16. It is further clear that if

this is a proper cause for adjudication by a district court

of three judges that Judge Taylor’s disposition of the

cause in his April 20th opinion is a nullity, Stratton v.

St. Louis Southwest Railway Co., supra, and certainly he,

sitting alone, could not have granted the injunctive relief

for which petitioners applied.

The basic error, however, of which petitioners com

plain is the April 13th order of the district court of three

judges, which had been properly convened and which, on

March 13, 1951 had held a hearing on petitioners’ applica

tion for injunctive relief. Where a district court of three

judges refused to act on a question in which their deter

mination is made mandatory by statutes, this Court may

issue a writ of mandamus requiring them to do so. In the

matter of the Public National Bank of New York, 278 IT. S.

101; Osage Tribe of Indians v. Ickes, 45 F. Supp. 178, 186,

187 (DC. 1942). It is submitted that a writ of mandamus

should be granted in this case.

Conclusion

The question, however, is not free from doubt since the

order of April 13th dissolving the specially-constituted

court and ordering the cause to proceed before a district

judge sitting alone could be considered a denial of peti

tioners’ application for a temporary and a permanent in

junction. If so considered, petitioners’ proper recourse

is to invoke Title 28, United States Code, Section 1253, and

appeal directly to this Court. See Smith v. Wilson, 273

U. S. 388; Oklahoma Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Pack

ing Co., 292 U. S. 386. Petitioners are not certain whether

direct appeal or application to this Court for a writ of

mandamus is their proper procedural remedy. Having al

ready taken an appeal to this Court, therefore, petitioners

17

are here making application for the issuance of a writ of

mandamus in the event their appeal should be considered

procedurally improper.

Respectfully submitted,

Z. Alexander L ooby,

R obert L. Carter,

T hixrgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Carl A. Cowan,

Avon N. W illiams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

[Appendices F ollow]

APPENDIX “A”

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NORTH

ERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 1567

Gene Mitchell Gray, L incoln A nderson B lakeney, J o

seph H utch P atterson and J ack Alexander, Plaintiffs,

v.

T he B oard of T rustees of the U niversity of T ennessee,

E tc., et al., Defendants

Before Miller, Circuit Judge, Dark and Taylor, District

Judges.

Miller, Circuit Judge. Tlie plaintiffs by this action seek

to enjoin the Board of Trustees of the University of Ten

nessee, the University of Tennessee, and certain of its

officers from denying them admission to the Graduate

School and to the College of Law of the University because

they are members of the Negro race.

In brief, the complaint alleges that the plaintiffs are

citizens of the United States and of the State of Tennessee,

are residents of and domiciled in the City of Knoxville,

State of Tennessee, and are members of the Negro race;

that plaintiffs, Gene Mitchell Gray and Jack Alexander,

are fully qualified for admission as graduate students to the

Graduate School of the University; that plaintiffs Lincoln

Anderson Blakeney and Joseph Hutch Patterson are fully

qualified for admission as undergraduate students in law to

the College of Law of the University; that the four plain

tiffs are ready, willing and able to pay all lawful charges

and fees, and to comply with all lawful rules and regula

tions, requisite to their admission; that the University of

Tennessee is a corporation duly organized and existing

under the laws of Tennessee, was established and is oper

ated as a State function by the State of Tennessee, with

two of its integral parts or departments being the Graduate

[ 1 9 ]

School and the College of Law; that it operates as an es

sential part of the public school system of the State of

Tennessee, maintained by appropriations from the public

funds of said State raised by taxation upon the citizens

and taxpayers of the State including the plaintiffs; that

there is no other institution maintained or operated by the

State at which plaintiffs might obtain the graduate or legal

education for which they have applied to the Univer

sity of Tennessee; that the plaintiffs Gene Mitchell Gray

and Jack Alexander applied for admission as graduate

students to the Graduate School of the University and that

the plaintiffs Lincoln Anderson Blakeney and Joseph Hutch

Patterson applied for admission as undergraduate students

in law to the College of Law of the University; and that on

or about December 4, 1950, the Board of Trustees of the

University refused and denied each and all of their appli

cations for admission because of their race or color, relying

upon the Constitution and Statutes of the State of Tennes

see providing that there shall be segregation in the educa

tion of the races in the schools and colleges in the State.

Plaintiffs contend that the action of the defendants in deny

ing them admission to the University denies the plaintiffs,

and other Negroes similarly situated, because of their race

or color, their privileges and immunities as citizens of the

United States, their liberty and property without due

process of law, and the equal protection of the laws, se

cured by the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of, the

United States and by Section 41, Title 8, United States

Code.

The defendants, by answer, state that they are acting

under and pursuant to the Constitution and the Statutes of

the State of Tennessee, by which they are enjoined from

permitting any white and negro children to be received as

scholars together in the same school; that provision has

been made by Tennessee Statutes to provide professional

education for colored persons not offered to them in state

colleges for Negroes but offered for white students in the

University of Tennessee; that the State of Tennessee, under

its Constitution and Statutes and under its police power,

lias adopted reasonable regulations for the operation of its

institutions based upon established usages, customs and

traditions, and such regulations being reasonable are not

subject to challenge by the plaintiffs; and that the 14th

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States did not

authorize the Federal Government to take away from the

State the right to adopt all reasonable laws and regulations

for the preservation of the public peace and good order

under the inherent police power of the State.

The plaintiffs requested a hearing by a three-judge court

under the provisions of Title 28 U. S. Code, Section 2281,

and moved for judgment on the pleadings in that the plead

ings showed that there was no dispute as to any material

fact and they were entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

The present three-judge court was designated and in due

course the case was argued before it.

We are of the opinion that the case is not one for de

cision. by a three-judge court. Title 28 XT. S. Code, Section

2281, requires the action of a three-judge court only when

an injunction is issued restraining the action of any officer

of the State upon the ground of the unconstitutionality of

such statute. We are of the opinion that the case presents

a question of alleged discrimination on the part of the

defendants against the plaintiffs under the equal protection

clause of the 14th Amendment, rather than the unconstitu

tionality of the statutory law- of Tennessee requiring segre

gation in education. As such, it is one for decision by the

District Judge instead of by a three-judge court.

The plaintiffs rely chiefly upon the decisions of the Su

preme Court in Missouri v. Canada, 305 U. S. 331, Sipuel

v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, Sweatt v. Painter, 339

IT. S. 629 and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U. S. 637, in which State Universities were required to ad

mit qualified negro applicants. In each of those cases the

plaintiff was granted the right to be admitted to the State

University on equal terms with white students because of

the failure of the State to furnish to the negro applicant

educational facilities equal to those furnished white stu

dents at the State University. The rulings therein are based

upon illegal discrimination under the equal protection

clause of the 14th Amendment, not upon the uneonstitu-

2 2

tionality of a State statute. In Sweatt v. Painter, supra,

the Court expressly pointed out (339 II. S. at Page 631) that

it was eliminating from the case the question of constitu

tionality of the State statute which restricted admission

to the University to white students. Those eases did not

change the rule, previously laid down by the Supreme

Court, that State legislation requiring segregatoin was not

unconstitutional because of the feature of segregation,

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; McCabe v. Atchison T.

& S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151, provided equal facilities were

furnished to the segregated races. In Sweatt v. Painted,

supra, the Supreme Court declined (339 U. S. at Page 636)

to re-examine its ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra. In

Berea College v. United States, 211 U. S. 45, and Gong Lum

v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78, state segregation statutes dealing spe

cifically with education were not held to be unconstitutional.

The validity of such legislation was recognized in Missouri

x. Canada, supra, wherein the Court stated (305 U. S. at

page 344)—“ The State has sought to fulfill that obligation

by furnishing equal facilities in separate schools, a method

the validity of which has been sustained by our decisions.”

In that case, as well as in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, there

were State statutes which required segregation for the

purpose of higher education, but the decisions in those cases

did not declare those statutes unconstitutional.

By Chapter 43 of the Public Acts of 1941, the State of

Tennessee authorized and directed the State Board of Edu

cation and the Commissioner of Education to provide edu

cational training and instruction for negro citizens of Ten

nessee equivalent to that provided at the University of Ten

nessee by the State of Tennessee for white citizens of Ten

nessee, such training and instruction to be made available

in a manner to be prescribed by the State Board of Educa

tion and the Commissioner of Education, provided, that the

members of the negro race and white race should not attend

the same institution or place of learning. The Supreme

Court of Tennessee has held that Act to be mandatory in

character. State ex rel. Michael v. Wit-ham, 179 Tenn. (15

Beeler) 250. Such legislation, specifically requiring equal

educational training and instruction for white and negro

23

citizens, appears to go further than did some of the State

Statutes involved in the Supreme Court cases above re

ferred to, which were not declared unconstitutional in those

cases. In our opinion, this case does not turn upon the

unconstitutionality of the state statutes, but presents the

same issue as was presented to the Supreme Court in Mis

souri v. Canada, supra, Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra,

Sweatt v. Painter, supra, and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, supra, namely, the question of discrimination

under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Accordingly, this case, at least in its present stage, is one

for decision by the District Judge, in the district of its

filing, on the issue of alleged discrimination against the

plaintiffs under the equal protection clause of the 14th

Amendment. Such an issue does not address itself to a

three-judge court. Ex parte Bramford, 310 U. S. 354;

Ex parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565; Rescue Army v. Municipal

Court, 331 U. S. 549, 568-574.

The two Judges designated by the Chief Judge of the

Circuit to sit with the District Judge in the hearing and

decision of this case do now accordingly withdraw from the

case, which will proceed in the District Court where it was

originally filed. See Lee v. Roseberry, 94 Fed. Supp. 324,

328.

24

UNIITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DIVISION OF TENNESSEE, NORTHERN

DIVISION

1567

Gene Mitchell Gray, L incoln A nderson Blakeney, J oseph

H utch P atterson and J ack A lexander, Plaintiffs,

v.

T he B oard oe T rustees of the U niversity of T ennessee,

E tc., et al., Defendants

Order

Before Miller, Circuit Judge; Darr and Taylor, District

Judges

This case was heard on the record, briefs and argument

of counsel for respective parties.

And the Court being of the opinion that the issue involved

is alleged unjust discrimination ag*ainst the plaintiffs under

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, and not the consti

tutionality of certain statutes of the State of Tennessee,

referred to in the pleadings;

And such issue not being one for decision by a three-

judge court under the provisions of Section 2281, Title 28,

U. S. Code;

It is ordered that the two Judges designated by the

Chief Judge of the Circuit to sit with the District Judge,

in whose District the action was filed, do now withdraw

from the case, and that the case proceed before said Dis

trict Judge in the District of its filing.

(S.) Shackelford Miller, J r.,

Circuit Judge;

(S.) L eslie R. Darr,

District Judge;

(S.) R obt. L. T aylor,

District Judge.

25

APPENDIX “B”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE,

NORTHERN DIVISION

Civil No. 1567

Gene Mitchell Gray et al.

vs.

U niversity of T ennessee e t al.

This case was heard by a three-judge court on the record,

briefs and argument of counsel for the respective parties

on plaintiffs ’ motion for summary judgment in their favor

under Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

In an opinion by Circuit Judge Miller, in which Chief

District Judge Darr and District Judge Taylor of the East

ern District of Tennessee, concurred, the Court held that

the issue involved is alleged unjust discrimination against

the plaintiffs under the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States

and not the constitutionality of the Tennessee statutes and

constitutional provisions referred to in the complaint. Fol

lowing this opinion and the order entered pursuant thereto,

Judge Miller and Judge Darr withdrew from the case,

which is now before this Court for decision on the motion.

Plaintiffs Gray and Alexander have applied for admis

sion to the Graduate School and plaintiffs Blakeney and

Patterson have applied for admission to the College of

Law, of the University of Tennessee. All admittedly are

qualified for admission, except for the fact that they are

negroes.

The matter of their applications was referred by Uni

versity authorities to the Board of Trustees, who disposed

of the matter by the following resolution:

“ Whereas, the Constitution and the statutes of the

State of Tennessee expressly provide that there shall

be segregation in the education of the races in schools

26

and colleges in the State and that a violation of the laws

of the State in this regard subjects the violator to

prosecution, conviction, and punishment as therein pro

vided; and,

“ Whereas, this Board is bound by the Constitutional

provision and acts referred to;

“ Be it therefore resolved, that the applications by

members of the Negro race for admission as students

into The University of Tennessee be and the same are

hereby denied.”

Following the indicated action by the Board of Trustees,

plaintiffs filed their joint complaint for themselves and on

behalf of all negro citizens similarly situated, praying for

a temporary and, after hearing, a permanent order restrain

ing the defendants from executing the exclusion order of

the Board of Trustees against the plaintiffs, or other ne

groes similarly situated, and from all action pursuant to the

constitution and statutes of the State of Tennessee, and the

custom or usage of the defendants, respecting the require

ment of segregation of whites and negroes in state-sup-

ported educational institutions and exclusion of negroes

from the University of Tennessee, their references being to

Article 11, sec. 12, of the state constitution, to sections

2403.1, 2403.3, 11395, 11396, and 11397 of the Tennessee

Code, and the custom and usage of defendants of excluding

negroes from all colleges, schools, departments, and divi

sions of the University of Tennessee, including the Gradu

ate School and the College of Law.

Defenses interposed are nine in number, but in substance

they are these: That defendants, in rejecting the applica

tions of the plaintiffs, were and are obeying the mandates

of the segregation provisions of the constitution and laws

of the State of Tennessee; that those provisions are in

exercise of the police powers reserved to the states and are

valid, the Fourteenth Amendment and laws enacted there

under to the contrary notwithstanding, and that these plain

tiffs have no standing to bring this action for the reason

that they have not exhausted their administrative remedies

under the equivalent facilities act of 1941, Code section

27

2403.3. The plaintiffs, after alleging in their complaint that

the University of Tennessee maintains a Graduate School

and a College of Law which offer to white students the

courses sought by plaintiffs, make the following specific

allegation, which defendants, for failure to deny, admit:

‘ ‘ There is no other institution maintained or operated by the

State of Tennessee at which plaintiffs might obtain the

graduate and/or legal education for which they respectively

have applied to The University of Tennessee.”

It is, of course, recognized that the Constitution of the

United States is one of enumerated and delegated powers.

To remove original doubt as to the character of federal

powers, the states adopted the Tenth Amendment, which

provides: “ The powers not delegated to the United States

by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are

reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” The

Constitution contains no specific delegation of police powers,

and those powers are accordingly reserved. But a glance

discloses that, in relation to the Tenth Amendment, the

Constitution contains two groups of powers, namely, the

previously-delegated powers and the subsequently-delegated

powers. By adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, follow

ing adoption of the Tenth Amendment, the states consented

to limitations upon their reserved powers, particularly in

the following respects: “ . . . No State shall make or

enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or im

munities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any

State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, with

out due process of law; nor deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws . . . ”

It is recognized that “ the police power of a state extends

beyond health, morals and safety, and comprehends the

duty, within constitutional limitations, to protect the well

being and tranquility of a community.” Kovacs v. Cooper,

336 U. S. 77, 83. (Italics supplied). States “ have power

to legislate against what are found to be injurious practices

in their internal commercial and business affairs, so long

as their laws do not run a,foul of some specific constitutional

prohibition, or of some valid federal law." Whitaker v.

North Carolina, 335, U. S. 525, 536. (Italics supplied).

28

In the foregoing quotations, the italicized portions point

up the limitations upon the exercise of a state’s police

powers.

Segregation by law may, in a given situation, be a valid

exercise of the state’s police powers. It has been so recog

nized with respect to schools. Gong Lum et al v. Rice et al,

275 U. S. 78. Also, as to segregation on intrastate trains.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537. But where enforcement

by the state of a law ran afoul of the Fourteenth Amend

ment by denying members of a particular race or nationality

equal rights as to property or the equal protection of the

laws, the state action has been condemned. This was the

result where state law discriminated against aliens as to

the privilege of employment. Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33.

The same result was reached as to enforcement of restrictive

covenants in deeds, Shelley et ux v. Kraemer et ux, 334

U. S. 1; in the housing segregation cases, Richmond v.

Deans, 4 Cir., 37 F. 2d 712, affirmed 281 U. S. 704; Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60: and in the cases where segregation

has resulted in inequality of educational opportunities for

negroes, Sweatt v. Painter et al, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. From these cases

it appears to be well settled that exercise of the state’s

police powers ceases to be valid when it violates the pro

hibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment. The defense on

this ground, therefore, fails.

The second question is whether the plaintiffs have pres

ent standing to bring this action. To understand the de

fense interposed here, it is desirable to look at the historical

background of the act of 1941, of which the Court takes

judicial notice.

On October 18,1939, six negroes applied for admission to

the University of Tennessee, four to the Graduate Depart

ment and two to the College of Law. Being denied admis

sion, they filed their separate petitions for mandamus in

the Chancery Court of Knox County, Tennessee, to require

their admission. Following denial of the petitions in a

consolidated proceeding, an appeal was taken to the Su

preme Court of Tennessee, where the action of the Chan

cellor was affirmed by opinion filed November 7, 1942. State

29

ex rel. Michael et al. v. Withaxn et ah, 179 Tenn. 250. The

case was not disposed of by the Chancellor on its merits,

but on the ground that it had become moot. While the case

was pending in the Chancery Court, the state legislature

enacted the act of 1941, now carried in the Code as sec.

2403.3, and entitled, Educational facilities for negro citizens

equivalent to those provided for white citizens:

“ The state board of education and the commissioner

of education are hereby authorized and directed to

provide educational training and instruction for negro

citizens of Tennessee equivalent to that provided at the

University of Tennessee by the State of Tennessee for

white citizens of Tennessee. Such training and instruc

tion shall be made available in a manner to be pre

scribed by the state board of education and the com

missioner of education; provided, that members of the

negro race and white race shall not attend the same

institution or place of learning. The facilities of the

Agricultural and Industrial State College, and other

institutions located in Tennessee, may be used when

deemed advisable by the state board of education and

the commissioner of education, insofar as the facilities

of same are adequate.”

Following enactment of the statute a supplemental answer

was filed in the case then pending, in which it was averred

that pursuant to the Act certain committees had been

appointed by the state board of education, with instructions

to report at the board’s next regular meeting, an averment

which suggested that the act of 1941 was to be made opera

tive expeditiously.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee, in affirming the Chan

cellor’s dismissal of the consolidated case, construed the

act of 1941 to be mandatory in character. “ No discretion

whatever is vested in the State Board of Education under

the Act as to performance of its mandates. The manner

of providing educational training and instruction for negro

citizens equivalent to that provided for white citizens at the

University of Tennessee is for the Board of Education to

determine in its sound discretion, but the furnishing of such

30

equivalent instruction is mandatory.” State ex rel. Micliael

et al. v. Witham et al., 179 Tenn. 250, 257.

The court also said at page 257: “ Upon the demand of a

negro upon the State Board of Education for training and

instruction in any branch of learning taught in the Univer

sity of Tennessee, it is the duty of the Board to provide such

negro with equal facilities of instruction in such subjects

as that enjoyed by the students of the University of Ten

nessee. The State Board of Education is entitled to rea

sonable advance notice of the intention of a negro student

to require such facilities . . . No such advance notice by

appellants is shown in the record.”

At page 258, the court further said: “ It does not appear

that the State Board of Education is seeking in any way to

evade the performance of the duties placed upon it by Chap

ter 43, Public Acts 1941, or that it is lacking sufficient funds

to carry out the purposes of the Act. The state having

provided a full, adequate and complete method by which

negroes may obtain educational training and instruction

equivalent to that provided at the University of Tennessee,

a decision of the issues made in the consolidated causes be

comes unnecessary and improper. The legislation of 1941

took no rights away from appellants; on the contrary the

right to equality in education with white students was

specifically recognized and the method by which those rights

would be satisfied was set forth in the legislation. What

more could be demanded!”

By failure to deny the allegations of the complaint, de

fendants admit that the directive, though mandatory, has

not been carried out. Nevertheless, it is urged by defend

ants that these plaintiffs have no standing here until they

have petitioned the state board of education to furnish the

equivalent educational training and instruction for negroes

provided for by the act. The Supreme Court of the state

noted in its opinion that the then applicants for admission

to the University of Tennessee had given to the state board

“ no such advance notice” of a desire to be furnished facil

ities under the act. That omission is understandable here

for the reason that their applications for admission to the

University of Tennessee had not been finally disposed of by

31

the courts, and the need of their applying* to the state board

had not been established.

Since the enactment of the Act of 1941 and the decision

in State ex rel. Michael et al. v. Witham et al., 179 Tenn. 250,

the Supreme Court of the United States has emphasized the

pronouncement of one of its older cases as to a particular

element of equal protection. In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, 305 U. S. 337, it appeared that Lincoln University,

a state-supported school for negroes, intended to establish

a law school. As to this intention the court said: “ . . . it

cannot be said that a mere declaration of purpose, still

unfulfilled, is enough.” Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337, 346. In the same case, at page 351, the court

said: “ Here, petitioner’s right was a personal one. It was

as an individual that he was entitled to the equal protection

of the laws, and the State was bound to furnish him within

its borders facilities for legal education substantially equal

to those which the State there afforded for persons of the

white race, . . . ” Later declarations indicate that the two

quotations should be read together and that when so read

they state the requirement of equality of opportunity to be

personal and immediate.

In Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147, the court emphasized its

position that equality of opportunity in education means

present equality, not the promise of future equality. This

re-emphasized the necessity of equality as to time of an

earlier decision, where the court said: “ The State must

provide it for her in conformity with the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and provide it as soon

as it does for applicants of any other group.” Sipuel v.

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma et al., 332

U. S. 631. In the holding in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 642, the court said: “ We conclude

that the conditions under which this appellant is required

to receive his education deprive him of his personal and

present right to the equal protection of the laws.” That

equality of educational opportunity for negroes means

present equality was emphasized once more in Sweatt v.

Painter et al., 339 U. S. 629, 635: “ This Court has stated

unanimously that ‘The State must provide (legal education)

32

for (petitioner) in conformity with the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and provide it as soon

as it does for applicants of any other group’. Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631, 633.” In view of these

recent declarations of the Supreme Court of the United

States, this Court is forced to conclude that the defense of

exhaustion of administrative remedies fails.

The Court finds that under the Gaines, Sipuel, Sweatt and

McLaurin cases heretofore cited, these plaintiffs are being

denied their right to the equal protection of the laws as pro

vided by the Fourteenth Amendment and holds that under

the decisions of the Supreme Court the plaintiffs are en

titled to be admitted to the schools of the University of

Tennessee to which they have applied for admission. Be

lieving that the University authorities will either comply

with the law as herein declared or take the ease up on

appeal, the Court does not deem an injunctive order pres

ently to be appropriate. The case, however, will be retained

on the docket for such orders as may seem proper when it

appears that the applicable law has been finally declared.

(S.) R obt. L. T aylor,

United States District Judge.

Office-Supreme Court, U. S.

TILED

JUN 15 1351

I CHARLES £Uv:

S U P R E ME EOURT OF THE U N I T E D - S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

N o . 1 2 0

GENE MITCHELL GRAY, LINCOLN ANDERSON

BLAKENEY, JOSEPH HUTCH PATTERSON, and

JACK ALEXANDER, Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF, TENNESSEE, ETC., ET AL.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

STATEMENT BY APPELLEES OF GROUNDS IN OP

POSITION TO APPELLATE JURISDICTION OF THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES PUR

SUANT TO SUPREME COURT RULE 12, AND MO

TION TO DISMISS APPEAL.

The appellees state the following matters and grounds

against the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United

States, as asserted by the appellants herein in their state

ment of the basis of the appellate jurisdiction, filed herein

2

on the 7th day of May, 1951, as required by Rule 12 of the

Supreme Court:

I

This case was not a proper case for the consideration of

a three-judge court. In support of this contention, the ap

pellees cite the following cases: Ex Parte Bransford, 310

U. S. 354; Ex Parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565; Rescue Army v.

Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549, 568-574. Consequently, no

direct appeal lies to the Supreme Court under Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 1253 and 2101(b). (See also

the opinion of the District Court of three Judges for the

Eastern District of Tennessee in this cause, filed on April

13, 1951, which has not yet been reported but a copy of

which is attached as Appendix A to the appellants’ state

ment and petition for the allowance of an appeal to the

Supreme Court filed herein.)

II

The opinion of the District Court of three Judges for the

Eastern District of Tennessee, filed on April 13, 1951, in

this cause and the order entered pursuant thereto shows

that the question involved in this case is the alleged unjust

discrimination against the plaintiffs under the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States, and not the constitutionality

of certain statutes of the State of Tennessee, or the order

of the Board of Trustees of the University of Tennessee,

referred to in the pleadings.

III

The pleadings in this cause show that the real question

presented is whether or not the plaintiffs exhausted their

administrative remedies as provided by Chapter 43 of the

Public Acts of Tennessee of 1941, and hence no constitu

3

tional question was presented for determination by a three-

judge court,. Accordingly, no direct appeal lies to the

Supreme Court.

IV

The right of the plaintiffs to appeal is not to the Supreme

Court but to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

V

The record discloses that the defendants prayed no ap

peal from the opinion and judgment of the District Court

for the Eastern District of Tennessee, Northern Division,

filed on April 20, 1951. Consequently, the questions sought

to be presented by the plaintiffs in their application to ap

peal fo the Supreme Court are now moot for the reason

that said opinion and judgment of the District Court will

become final prior to the filing of this record with the

Supreme Court of the United States, entitling plaintiffs

to the relief provided by said opinion and order of the

District Court.

W h e r e f o r e , the appellees move the Court to dismiss the

appellants’ petition for the allowance of an appeal to the

Supreme Court.

Dated: May 17, 1951.

Respectfully submitted,

K. H arlan D odson, J r.,

J ohn J . H ooker,

By (S.) J ohn J . H ooker,

Attorneys for Appellees.

(5571)