Bernard v. Gulf Oil Corporation Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

September 18, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bernard v. Gulf Oil Corporation Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1986. 76b20ec2-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6159ce67-d5f1-476f-8ee7-2574492cf59f/bernard-v-gulf-oil-corporation-appendix-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

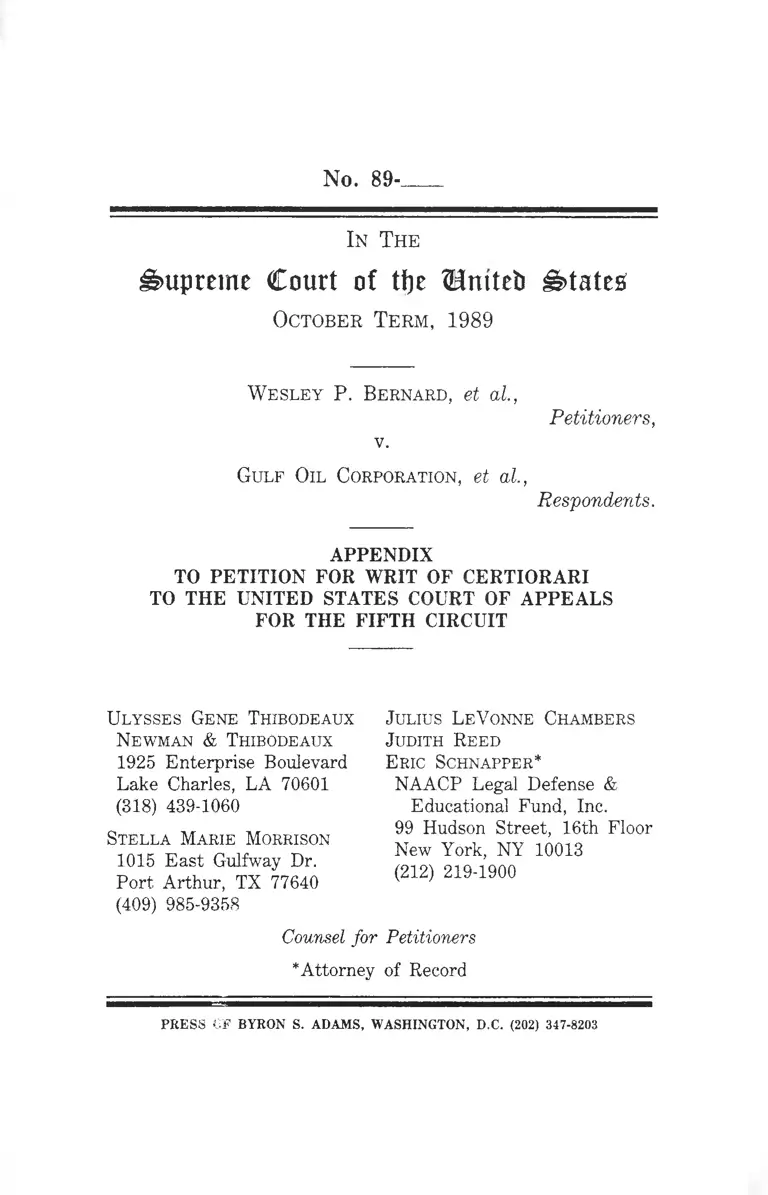

No. 89-

In The

Supreme Court of tt)e Mmteti ^>tate£

October Term , 1989

Wesley P. Bernard, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

Gulf Oil Corporation, et al,

Respondents.

APPENDIX

TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux

Newman & Thibodeaux

1925 Enterprise Boulevard

Lake Charles, LA 70601

(318) 439-1060

Stella Marie Morrison

1015 East Gulfway Dr.

Port Arthur, TX 77640

(409) 985-9358

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Judith Reed

Eric Schnapper*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Petitioners

* Attorney of Record

PRESS CP BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Decision of the United States

Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

Dec. 18, 1989 ............................................... la

Decision of the United States

Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

March 22, 1988 45a

Decision of the United States

District Court for the

Eastern District of Texas,

Beaumont Division

Sept. 1, 1988 135a

Decision of the United States

District Court for the

Eastern District of Texas,

Beaumont Division,

Sept. 18, 1986 209a

l a

Wesley P. BERNARD, Elton Hayes, Rod

ney Tizeno, Hence Brown, Doris Whit

ley and Willie Johnson, Plaintiffs-Ap-

pellants,

v.

GULF OIL CORP, et al,

Defendants-Appellees,

No. 88-6141.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit

Dec. 18, 1989.

Before BROWN, REAVLEY, and

HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges.

PATRICK E. HIGGINBOTHAM,

Circuit Judge:

The case history is long, from 1967, when the first

complaint was lodged with the EEOC, to this appeal, the

third before this court. In 1976, six present and retired

black employees at the Gulf Oil Corporation’s Port

Arthur, Texas refinery filed this suit. The complaint

alleged a variety of racially discriminatory practices in

violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981,

and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §

2000e et seq. In 1977, the district court dismissed the Title

VII claims on procedural grounds, and granted summary

judgment on the § 1981 claims (Bernard 2) This court

reversed. 619 F.2d 459 (5th Cir. 1980) (en banc), aff’d 452

U.S. 89, 101 S.Ct. 2193, 68 L.Ed.2d 693 (1981) {Bernard

II) The case was tried in 1984. In 1986, the district court

issued its opinion finding in favor of the defendants on all

claims. 643 F.Supp. 1494 (E.D.Tex. 1986) {Bernard III).

This court affirmed in part and vacated in part, remanding

the case for further findings. 841 F»2d 547 (5th Cir.1988)

{Bernard IV). On remand the district court again found

for the defendants on all issues {Bernard V).

On January 24, 1983, the district court provisionally

certified a class of all blacks who had worked or applied

for work at the refinery in union covered jobs at any time

2a

after December 26, 1966. Pursuant to the order of the

district court, written notification of the class action and

certification was mailed in September 1983 to the

members of the class. In April 1984, the district court

modified that certification order to exclude a substantial

number of the original class members, and this court

upheld that modification. Bernard IV, 841 F.2d at 550.

On remand plaintiffs requested that the former class

members be notified of that change. The defendants

opposed the motion, and the district judge denied it.

The class appeals from the district court’s ruling in

favor of the defendants and from the denial of the motion

to notify former class members. The class contends that

the Gulf seniority system is not bona fide, that Stipulation

29 was intentionally discriminatory, and that the tests used

by Gulf to determine who was eligible for promotion were

discriminatory because they had an adverse impact on

blacks and were not sufficiently job related. In addition,

3a

three individual plaintiffs, Mr. Brown, Mr. Hayes and Mr.

Tizeno, appeal from the district court’s ruling that Gulf

did not discriminate in not promoting them. We affirm

because we are persuaded that the district court was not

clearly erroneous in its determination that Stipulation 29

was not purposefully discriminatory and was justified by

valid business reasons, the craft tests were sufficiently job

related, and there was no discrimination in the failure to

promote Mr. Brown, Mr. Hayes and Mr. Tizeno.

I. Factual Background

Gulfs Port Arthur refinery has had three basic

work areas throughout its history: operations and

maintenance ("Crafts"), which require skilled employees,

and until 1954 were staffed exclusively by whites; and

labor, which is composed of unskilled employees who

assist the craft groups, and until 1956 was exclusively

comprised of blacks.

4a

In 1950 the labor department had many

subdepartments, each assigned to work with a specific

craft department. The twenty integrated craft departments

effectively had two separate lines of progression, one for

their white employees and the other for the black

employees assigned to their departments. Although black

laborers effectively worked in many of the same

departments as white craft employees, they could not bid

into the more desirable white lines of progression.

Between 1954 and 1956, the craft and labor departments

were assigned to one of two divisions. The craft

departments were assigned to the Operating and

Mechanical ("O & M") Division, and the labor

department, with its various subdepartments, was assigned

to the Labor Division. As of 1956, both black and white

employees progressed up their separate promotional lines

based on plant seniority and ability to perform. Newly

hired blacks would be assigned to the Labor Division,

5a

while newly hired whites would be assigned to one of the

craft departments in the O & M Division.

The 1956 Contract between Gulf and the OCAW

made the "Labor" classifications in the Labor Division the

entry level position for all employees, both black and

white. After progressing to the top position in one of the

Labor lines of progression, an employee could transfer to

an entry level position in one of the O & M lines of

progression after bidding into the mechanical helper pool,

which was a classification apparently created to provide

apprentice-type instruction for employees entering an O &

M line of progression. Bids for entry into the O & M

lines of progression were selected on the basis of plant

seniority. An employee who successfully bid into an O &

M line of progression was assigned dual seniority, O & M

Division seniority and plant seniority. White employees

generally had more O & M seniority because of the

earlier practice of hiring whites directly into the craft

6a

positions. In 1963, divisional seniority was eliminated, and

plant seniority became the basis for all promotions,

demotions and lay offs. The effect of this change was that

blacks with more plant seniority but less O & M seniority

than whites in the same job classification could compete

for promotions to the next highest classification based

upon their longer plant seniority, thereby bypassing white

employees with greater O & M seniority.

In 1967, Gulf management became convinced that

its plant was inefficient. As part of a general

restructuring, Gulf and OCAW made a special agreement,

Stipulation 29, which reclassified workers in the

maintenance departments.2 As part of the restructuring

the Labor Division was eliminated and its employees were

assigned to the various crafts with which they had been

working. The lines of progression were streamlined and

1 jSee next page for text of this footnote.]

7a

Note 1

BEFORE REORGANIZATION

& STIPULATION 29

0 & M DIVISION

Instrument Depart.

Instrument Man No.1

Mechanical

Trainee

Instrument Man No.2

(Craft Helper)

Instrument Man No.3

(Craft Helper)

Mechanical

Helper Pool

LABOR DIVISION

Labor Subdepart.

Utili ty Man No.1

(Intermediate Job

Classifications)

L a b o re r

AFTER REORGANIZATION

& STIPULATION 29

MAINTENANCE DIVISION

Instrument

Instrument Man

Mechanical

Trainee

Utility Man

Laborer

8a

the categories of "mechanical helper" and "craft helper"

were eliminated. Those who were mechanical helpers

were reclassified as "utility men" (a demotion), while

Stipulation 29 reclassified the craft helpers as "craft

trainees" (a promotion) if they passed a simple test. 203

of 204 who took the test passed and were promoted to

mechanical trainee. 95.6% of those promoted were white.

A large portion of the utility men and mechanical helpers

were black.

Both before and after Stipulation 29 all others not

transferred as a result of Stipulation 29 were required to

pass a battery of written tests in order to become craft

trainees. These tests had an adverse impact on blacks in

that blacks had a significantly lower pass rate than whites.

The "Old Tests" were administered prior to 1971, and the

9a

"New Tests" after 1971.2 Both sets of tests had an

adverse impact on blacks.5 No validation study was ever

done on the old tests, but Gulf has attempted to show

that the new tests are job related through a study to

determine the correlation between test scores and job

performance.

II. The Seniority System and

Stipulation 29

The class first argues that the seniority system is

not bona fide because it locks in the effects of pre-Act

2The Old Tests consisted of six separate tests;

(A) Test of Reading Comprehension; (B) Test of

Arithmetic Fundamentals; (C) Wonderlic Personnel Test; (D)

Mechanical Aptitudes Test; (E) Mechanical Insight Test; (F) A Lee-

Clark Arithmetic Test.

The New Tests consisted of four parts: (A) Dennett [sic]

Mechanical Comprehension Test; (B) Test of Chemical

Comprehension; (C) Arithmetic Test; (D) Test Learning Ability.

After 1971, these tests were also used for the hiring of new

employees. Thus, any employee hired after 1971 was not required to

take any additional tests to enter a craft.

382.5% of whites who took the old tests between January 1969

and March 1971 ultimately passed. Only 42.8% of blacks who took

the same tests during that period passed. Between 1971 and 1980,

97.7% of the whites who took the new tests passed, while only 66%

of the blacks passed.

10a

discrimination. This issue was resolved by this court in

Bernard, IV, 841 F.2d 547 (5th Cir.1988), following

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 97 S.Ct. 1843, 52

L.Ed.396 (1977). Teamsters held that where an employer

had engaged in intentional discrimination in hiring or

assignments, the employer could lawfully utilize a seniority

system that perpetuated the effect of that earlier

discrimination, but only if the seniority system itself was

bona fide. 431 U.S. at 347-54, 97 S.Ct. at 1860-64.

Under Teamsters a seniority system in not bona fide if it

had "its genesis in racial discrimination" or was "negotiated

and maintained" with an "illegal purpose." 431 U.S. at

356, 97 S.Ct. at 1865. The class attempts to distinguish

Teamsters, arguing that, while pre-Act discrimination in

hiring and assignment will not make a post-Act seniority

system which is otherwise bona fide illegal, a pre-Act

seniority system which discriminated will make an

otherwise bona fide post-Act seniority system illegal. This

l la

contention was rejected in our earlier opinion, where we

expressly held:

[W]e question whether a seniority system

which is neutral as of the effective date of

Title VII, which is based on plant seniority,

and which has a single bargaining unit could

ever be held unlawful solely because of pre-

Act discrimination. That the 1963 changes

did not rectify the effects of past

discrimination, and in fact operated in some

ways to lock those effects in, does not imply,

in the absence of purposeful discrimination

in connection with the post-Act system, that

this system was not bona fide under 703(h).

See Teamsters, 481 US. at 353, 97 S.Ct. at

1863 (seniority system does not become

illegal "simply because it allows the full

exercise of the pre-Act seniority rights of

employees of a company that discriminates

before Title VII was enacted”).

841 F.2d at 556. We remanded to the district court to

determine whether Stipulation 29 evidenced purposeful

discrimination, "the establishment of which is essential to

plaintiffs’ claim that the seniority system was not bona fide

under 703(h)." 841 F.2d at 560

12a

The class really makes two arguments with respect

to Stipulation 29: first, that through its operation it served

to make the seniority system non-bona fide; and second,

that in and of itself it was a discriminatory act by the

employer in violation of Title VII because of its disparate

impact on blacks.

The district court found that Stipulation 29 was not

purposefully discriminatory and was justified by valid

business reasons. The class contests these findings. The

standard of review for such a decision is whether, looking

at the record as a whole, the district court was clearly

erroneous in its determination that there was no

purposeful discrimination and that the action resulting in

disparate impact was justified by legitimate business

reasons. Fed.R.Civ.P.52(a). See Anderson v. Bessemer

City, 470 U.S. 564, 105 S.Ct. 1504, 84 L.Ed.2d 518 (1985);

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395 LJ.S.

100, 123, 89 S.Ct. 1562, 1567, 23 L.Ed.2d 129 (1969);

13a

Moorhead v. Mitsubishi Aircraft International, 828 F.2d 278,

282 (5th Cir. 1987). We find that the district court was

not clearly erroneous.

Before Stipulation 29, black utility men could

become mechanical helpers and craft helpers, joining

whites with less seniority who had started in higher

positions than blacks because of the earlier discrimination.

When positions opened for craft trainees, those blacks

could bypass the whites with more craft seniority if the

blacks had longer plant seniority. Stipulation 29 worked

to lock blacks into the lower positions by promoting the

craft helpers, who at that time were mostly white and

often had less plant seniority than blacks, into the trainee

positions. Blacks were precluded from opportunities they

would have had earlier if it weren’t for Stipulation 29. In

Bernard IV, this court found that senior blacks were

denied the opportunity to by-pass junior whites, and the

class had, therefore, established a prima facie case of

14a

adverse impact. 841 F.2d at 560, citing Connecticut v.

Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 102 S.Ct. 2525, 73 L.Ed.2d 130 (1982).

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a), proscribes

discriminatory employment practices, including

discrimination "with respect to . . . compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment" on the basis of

race, but section 703(h) insulates bona fide seniority

systems from these dictates, providing that

[notwithstanding any other provision . . ., it

shall not be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer to apply different

standards of compensation or different

terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment pursuant to a bona fide

seniority or merit system, . . . provided that

such differences are not the result of an

intention to discriminate because of race . .

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h).

Whether a seniority system, neutral on its face, is

bona fide depends upon "whether there has been

purposeful discrimination in connection with the

15a

establishment or continuation of [the] seniority system."

Bernard IV , 841 F.2d at 555, citing James v. Stockham

Valves & Fitting Co., 559 F.2d 310, 351 (5th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034,98 S.Ct. 767, 54 L.Ed.2d 781

(1978). The Supreme Court in Teamsters set out four

factors relevant to making this determination, which this

court adopted in James:

(1) whether the seniority system operates to

discourage all employees equally from

transferring between seniority units;

(2) whether the seniority units are in the

same or separate bargaining units and, if

separate, whether that structure is rational

and industry-wide;

(3) whether the seniority system had its

genesis in racial discrimination; and

(4) whether the seniority system was

negotiated and maintained free from any

illegal purpose.

Id. at 352.

This court found the first three of the factors in

favor of defendants, but remanded to the district court to

16a

consider whether Stipulation 29 showed that the system

had been maintained with a discriminatory purpose.

Bernard IV’ 841 F.2d at 560. The district court found that

Stipulation 29 was adopted in an effort to improve

efficiency at the refinery, was undertaken for an economic

purpose, was undertaken for legitimate business reasons

and did not reflect purposeful racial discrimination.

The class points to evidence that Stipulation 29 was

racially motivated, but there was also evidence of

legitimate reasons for the reorganization of employees. In

addition, Gulf had various programs to increase mobility

for blacks in its plant. It had an affirmative action

program and several training programs to try to insure

that blacks would be able to rise within the company.

The record supports the district court’s determination, and

it is not clearly erroneous that Stipulation 29 was not

adopted for purposefully discriminatory reasons.

17a

Under a disparate impact theory as set out in

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct. 849, 28

L.Ed.2d 158 (1971), and clarified in Watson v. Fort Worth

Bank & Trust, _ U.S. 108 S.Ct. 2777, 101 L.Ed.2d

827 (1988) and Ward’s Cove Packing Co., Inc. v. Atonio,

_ U.S. ___ , 109 S.Ct. 2115, 104 L.Ed.2d 733 (1989), the

district court also was not clearly erroneous in finding that

although Stipulation 29 may have had an adverse impact

on blacks it was justified by legitimate business purposes.

Under Ward’s Cove, if a plaintiff makes out a prima

facie case by showing that a specific practice has a

disparate impact on a protected class, then the burden

shifts to the employer to produce evidence, but not to

prove, that the "challenged practice serves, in a significant

way, the legitimate employment goals of the employer."

109 S.Ct. at 2126. The Supreme Court noted that while

"a mere insubstantial justification in this regard will not

18a

suffice, . . . there is no requirement that the challenged

practice be ’essential’ . . . for it to pass muster." Id.

Moreover, although the employer carries the burden of

producing evidence of a business justification for his

employment practice, the burden of persuasion remains

with the disparate-impact plaintiff to prove that the

challenged practice does not significantly serve legitimate

employment goals. Id.; Watson, supra _U.S. at __, 108

S.Ct. at 2790.

The district court relied in part on the testimony of

Dr. Milden J. Fox, an expert in Industrial Relations, who

studied four refineries as part of his dissertation, which

was entered into evidence. Dr. Fox testified at trial that

Stipulation 29 was part of an ongoing effort to improve

efficiency at the Refinery. He testified that before

Stipulation 29 the method of work assignments contributed

to excess maintenance costs, and that management sought

to increase efficiency through measures permitting more

19a

flexible use of employees, including Stipulation 29.

Stipulation 29 was designed to take employees out of

specific craft job classifications, and move them into the

trainee positions, making them "universal mechanics," i.e.,

people who could perform any job associated with a

particular craft. Dr. Fox testified that various measures,

including Stipulation 29, conformed with industry practices

at the time. The testimony of Mr. Charles Draper, who

spent 30 years in the Refinery’s personnel department,

was consistent with Dr. Fox’s testimony. The district court

found that the craft helpers reclassified under Stipulation

29 had at least ten years’ experience in their craft, and as

craft helpers they performed a significant amount of the

work of the No. 1 (journeyman) craftsmen, so it would

take minimal additional training to qualify them as

journeyman craftsmen. The district court found that

mechanical helpers and laborers did not have comparable

experience, so they would require much more training to

20a

do the work of journeyman craftsmen efficiently and

safely. This is supported by the record, which shows that

the mechanical helpers and laborers were shuttled from

craft to craft to do whichever labor was necessary to help

those in the crafts, but did not receive training at any one

specific craft.

Plaintiffs contend that the district court

misunderstood the import of Stipulation 29, that it was

not a measure designed to change lines of progression,

but simply the promotion of 203 mostly white craft

helpers. Plaintiffs go too far in simplifying Stipulation 29:

it cannot be observed in isolation, but must be considered

in the context of Gulfs reorganization. The district court

found that Gulf wanted to simplify the lines of progression

through reorganizing, and wanted to increase the number

of craft trainees, leading to an increase in the number of

persons who were trained to handle all aspects of a craft.

In order to do that Gulf had several options. One option

21a

was Stipulation 29, which moved workers into trainee

positions from the next lowest position. Another option

(suggested by the class) would have been to demote all

the craft helpers to utility men, then draw craft trainees

from the pool of utility men that included senior blacks

who had been utility men and junior whites who had been

craft helpers. The district court found that Gulf had a

legitimate reason for choosing the Stipulation 29 option-

-it wanted to reclassify as trainees those workers with the

most craft experience so they would need less training.

The district court specifically found that the craft helpers

all had at least 10 years of craft experience. The utility

men who would have been in the pool under the second

option would not have had such experience in craft work,

even if they would have had greater plant seniority. The

class has not shown that the proposed alternative would

be equally as effective as Stipulation 29 in meeting Gulfs

objectives. See Ward’s Cove Packing Co., Inc. v. Atonio,

22a

_ U.s. 109 S.Ct. 2115, 2126, 104 L,Ed.2d 733 (1989).

Thus, the district court was not clearly erroneous in

finding that Gulf had legitimate business reasons for

Stipulation 29, and that it was not discriminatory.

III. The Craft Tests

The class claims that the tests used to determine

which employees were eligible for promotion to

journeyman craftsmen were discriminatory. It claims that

the tests had an adverse impact on blacks because the

pass rate for blacks was significantly lower than the pass

rate for whites, and that Gulf has failed to show that the

tests were sufficiently job related.

In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct.

849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971), the Supreme Court held that

Title VII forbids the use of employment tests that are

discriminatory in effect unless the employer meets "the

burden of showing that any given requirement [has] . . . a

manifest relationship to the employment in question." Id.

23a

at 432, 91 S.Ct. at 854. Once the plaintiffs have made

out a prima facie case of disparate impact, the employer

must then show that its tests are "job related." Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425, 95 S.Ct. 2362,

2375, 45 L.Ed.2d 280 (1975). If the employer shows that

the tests are job related, "it remains open to the

complaining party to show that other tests or selection

devices, without a similarly undesirable racial effect, would

also serve the employer’s legitimate interest in ’efficient

and trustworthy workmanship.’" Albermarle, 422 U.S. at

425, 95 S.Ct. at 2375, quoting McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 801, 93 S.Ct. 1817, 1823-24, 36

L.Ed.2d 668 (1973). Although an employer has the

burden of showing job relatedness, this does not mean

that the ultimate burden of proof can be shifted to the

defendant. "On the contrary, the ultimate burden of

proving that discrimination against a protected group has

been caused by a specific employment practice remains

24a

with the plaintiff at all times." Watson v. Fort Worth Bank

& Trust, _____U.S. ____, 108 S. Ct. 2777, 2790, 101

L.Ed.2d 827 (1988).

Both the pre-1971 "Old Tests" and the post-1971

"New Tests" had an adverse impact on blacks. On

remand the district court was to determine whether

"professionally accepted methods" showed that the tests

were "significantly correlated" to job performance in each

of the relevant crafts. Bernard IV, 841 F.2d at 566-67.

The district court was to explain specifically what it relied

on in determining significant correlation. Id.

The issue before us is whether Gulfs validation

methods were properly accepted by the district court.

Gulf had a validation study done which compared New

Test scores with performance in five crafts. Three of the

studies were inconclusive regarding correlation between

test scores and performance, while two studies yielded

correlation coefficients (measurements of the frequency

25a

with which higher test scores correlated with better job

performance) for the pipefitter and boilermaker crafts.^

The study then computed adjustments for various factors,

resulting in seven different adjusted correlation coefficients

for each craft. The class contends that the district court

should have specifically stated which correlation coefficient

it found a statistically significant indication of job

relatedness, and why a particular adjustment was chosen.

Plaintiffs urge that a correlation coefficient in the .30-.40

range be established as the minimum for proof of a job

4Test scores were compared to job performance for a number

of job classifications. The study developed by Richardson, Bellows

and Henry ("RBH") attempted to establish the validity of the new

tests for five of the OCAW crafts: boilermaking, pipefittings, welding

carpenter, and instrument. However, RBH was unable to validate the

tests for the latter three crafts. The job performance ratings for the

welders were too similar to establish a significant correlation between

test and job performance. In the case of carpenters and instrument

mechanics, the ratings given by the two raters used to evaluate job

performance (each employee was evaluated by two supervisors and

their ratings were compared to derive a single job performance rating)

differed to such a degree that RBH concluded that neither rating was

a reliable measure of the employees’ job performance. Therefore, the

1985 study introduced into evidence contained data about only two of

the craft departments, boilermaking and pipefitting.

26a

related test. We decline to establish a bright line cut-off

point for the establishment of job-relatedness in testing.

In Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust, the Supreme

Court stated:

[Ejmployers are not required, even when

defending standardized or objective tests, to

introduce formal ’validation studies’ showing

that particular criteria predict actual on-the-

job performance.

_ U .S . ____, ___ , 108 S.Ct. 2777, 2790, 101 L.Ed.2d 827

(1988). Justice Blackmun, while dissenting in part from

the plurality opinion, agreed on this point, recognizing that

"job-relatedness cannot always be established with

mathematical certainty" and that a variety of methods are

available for establishing the link between selection

processes and job performance, including the results of

studies, the presentation of expert testimony, or prior

successful experience. Id .,__ U.S. a t ____ , 108 S.Ct. at

2796. Therefore, plaintiffs urging a minimum correlation

27a

coefficient goes beyond what is required by Supreme

Court precedent.

This court held in its earlier opinion that:

To establish the job relatedness of the tests,

the degree of correlation between test scores

and job performance ratings must be

examined. The district court upheld the

validity of the tests without making any

findings concerning the sufficiency of

correlation. Because a finding of significant

correlation between test results and job

performance is a prerequisite to a holding

that the tests are job related, we assume

that the court sub silento [sic] made this

finding.

841 F„2d at 566. This court found no way to determine

the basis for the district court’s holding, however, so

remanded for further findings. Id. at 567. Although

appellants claim the district court did not make the

requisite findings upon remand, the district court did find

the following:

1. The study showed that performance on the

New Tests correlated .32 with job performance as

a Boilermaker, and .22 with performance as

28a

Pipefitter, and that these correlations are both

statistically significant.

2. Although the unadjusted correlations are

statistically significant, the adjusted figures, which

are even higher than unadjusted, are better

estimates of validity, and even they underestimate

the true validity of the New Tests.

3. The testimony of Gulfs expert witnesses was

convincing, and they adequately explained, based

upon research and their past experience, why the

tests were job related, why the correlation

coefficients resulting from the study needed to be

adjusted for various factors, and why these adjusted

figures were more accurate.

The district court was not clearly erroneous in its findings,

which are supported by the expert testimony in the

record. "The question of job relatedness must be viewed

in the context of the plant’s operation and the history of

the testing program." Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 430, 95 S.Ct.

at 2377-78. In Albermarle, the test were not found to be

job related because "no attempt was made to analyze jobs

in terms of the particular skills they might require." Id.

29a

Here the jobs were all analyzed in terms of particular

skills, and the test studies were conducted accordingly.

In its prior opinion, this court invited the district

court to consider whether the similarity between pairs of

jobs could be used to generalize the validity of the new

tests from boilermakers and pipefitters to craft jobs

involving similar abilities. Bernard TV' 841 F.2d at 567 n.

54. This sort of analysis can be used to extrapolate the

validity of the tests from the crafts for which a study was

done, to the crafts where no study was done, or where the

sample size was too small to get accurate results. The

rationale for this approach was accepted in Aguilera v.

Cook County Police & Corrections Merit Bd., 582 F. Supp.

1053, 1057 (N.D. 111.1984) (comparing required skills for

correctional officer with required skills for police officer),

aff’d 760 F.2d 844, 847-48 (7th Cir. 1985), cited with

approval in Davis v. City of Dallas, 777 F.2d 206, 212-13,

30a

n. 6 (5th Cir.1985), cert, denied, 476 U.S. 1116, 106 S.Q.

1972, 90 L.Ed.2d 656 (1986).

Having found that Gulf had shown the new tests

were significantly correlated with performance as a

boilermaker and pipefitter, the district court considered

and compared the most important abilities in those two

crafts with the important abilities in all the other crafts.

If the most important abilities required the other crafts

are closely related to the most important abilities of the

boilermaker or pipefitter, it may be concluded that the

new tests, which predict significant aspects of job

performance for the boilermaker or pipefitter, also predict

important abilities related to the performance of all other

craft jobs as well. The district court found that the most

important abilities for boilermakers or pipefitters were

closely related to the important abilities for all of the

other crafts, and extrapolated from that to find that the

tests were job related for all of the crafts.

3la

The district court accepted similar methods in

Cormier v. P.P.G. Industries, Inc., where "cluster analysis"

(looking for similar job traits, as was done here) was

approved as a way to find correlations between test scores

and performance. 519 F. Supp. 211, 259 (W.D.La.l9Sl),

aff’d 702 F.2d 567 (5th Cir. 1983). The district court’s use

of this method was reasonable, and its determination that

there was sufficient similarity in the skills required for the

various crafts to find the tests were job related for all

crafts is not clearly erroneous. The district court accepted

the same sort of "path analysis," in determining that the

"Old Tests" measured skills similar to those measured by

the "New Tests." Therefore, its finding that the "Old

Tests" were sufficiently job related to justify their use,

despite disparate impact on blacks, was not clearly

erroneous.

Finally, the class seeks to refute Gulf s showing that

the test were job related by showing an alternate method

32a

was available that would have had less adverse impact yet

met the same business purposes as the Old and New

Tests. See Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

95 S.Ct. 2362, 45 L.Ed.2d 280 (1975). Plaintiffs suggest

the simple test used in conjunction with Stipulation 29.

The district court rejected this alternative, making

no findings as to its adverse impact, and finding it unlikely

to suit Gulfs business purposes as well as the tests

actually used. The simple test was used once, as part of

a reorganization. The only people taking the test already

had ten years craft experience. Its purpose was to screen

out total incompetence, not determine who would do best

at a job. In order to require an alternative with less

disparate impact, the disparate-impact plaintiff must prove

that the proposed alternative is "equally effective" as the

employer’s procedure. Ward’s Cove Packing Co., Inc. v.

Atonio, _ U.S. 109 S.Ct. 2115, 2127, 104 L.Ed.2d 733

(1989). The Supreme Court has made it clear that by

33a

"equally effective" it meant an alternative practice that

would serve the employer’s business purpose fully as well

in terms of utility, cost, "or other burdens" of the

proposed alternative device. Id . The burden of proving

that Gulfs business reasons were not sufficient, and that

an alternative method of choosing craft trainees would be

equally as effective as the tests used by Gulf, remained

with the class at all times. Id., 109 S.Ct. at 2126.

Therefore, the district court’s finding that the simple tests

was not a viable alternative for the other Tests is not

clearly erroneous.

The Supreme Court has cautioned that the

"judiciary should proceed with care before mandating that

an employer must adopt a plaintiffs alternate selection or

hiring practice in response to a Title VII suit." Id. at

2127. In the face of statistically significant correlations,

professional test construction, commonality of abilities

associated with the various jobs at issue, the "path

34a

analysis" correlations of the Old and New Tests, and the

supporting expert opinion based upon massive validation

studies of similar tests in the industry, this court will

refrain from making business decisions for an employer

when it is not clearly erroneous that its promotion

practice is validly job related. "[I]t must be borne in mind

that ’[cjourts are generally less competent than employers

to restructure business practices, and unless mandated to

do so by Congress they should not attempt it." Watson,

_ U.S. at ____ , 108 S.Ct at 2791, quoting Fumco

Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 438 U.S. 567, 578,98

S.Ct. 2943, 2950, 57 L.Ed.2d 957 (1978).

IV. The Individual Claims

Three individual plaintiffs claim that Gulf

discriminated against them in making promotions. Mr.

Hayes, Mr. Brown and Mr. Tizeno all claim that they

were qualified to become supervisors, but were not

promoted, while whites were.

35a

A, Hayes and Brown

The district court made specific findings of fact that

Mr. Hayes and Mr. Brown, while complaining that they

had not been promoted to permanent supervisory jobs,

had testified that they had not made known to anyone in

authority their interest in becoming supervisors. The

district court further found that employees generally knew

when they were eligible and that they were invited to

inform supervisors of their interest in promotion. The

district court also found several reasons why some

employees would not want to be supervisors, and why it

could not be assumed that all employees should

automatically have been considered.

Under Texas Dep’t o f Community Affairs v. Burdine,

in a failure-to-promote case the plaintiff must prove that

he "applied for an available position for which [he] was

qualified, but was rejected under circumstance which give

rise to an inference of unlawful discrimination." 450 U.S.

36a

248, 253, 101. S.Ct. 1089, 1094, 67 L.Ed.2d 207 (1981),

(emphasis added). Under McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v.

Green, such a plaintiff establishes a prima facie case by

showing by a preponderance of the evidence that (a) he

belongs to a group protected by Title VII; (b) he was

qualified for the job; (c) he was not promoted; and (d)

the employer promoted one not in the plaintiffs

protected class. 411 U.S. 792, 802, 93 S.Ct. 1817, 1824, 36

L.Ed.2d 668 (1973).

The district court found that Hayes and Brown had

not established a prima facie case because their failure to

express interest made it impossible to tell which

promotion they did not get and thus whether a white or

a black was selected in preference to them. Blacks as

well as whites were made supervisors during the relevant

period in numbers proportional to those in the eligible

pool.

37a

Even assuming arguendo that Hayes & Brown had

established a prima facie case, the district court found that

Gulf had a sufficient business reason to rebut the

inference of discrimination.

If plaintiff makes out a prima facie

case, the employer must produce "evidence

that the plaintiff was rejected, or someone

else was preferred, for legitimate, non-

discriminatory reasons . . . [Burdine 450

U.S.] at 253-254 [501 S.Ct at 1094]. If the

employer meets this burden, "the

presumption of discrimination ’drops from

the case’ and the District Court is in a

position to decide whether the particular

employment decision at issue was made on

the basis of race."

McDonnell-Douglas, 411 U.S. at 802, 93 S.Ct. at 1824,

quoting Cooper v. Federal Bank, 467 U.S. 867, 104 S.Ct.

2794, 81 L.Ed.2d 718 (1984). In meeting its burden of

production, Gulf did not have to prove what its reasons

were; it simply had to produce evidence that "raise[d] a

genuine issue of fact as to whether it discriminated"

against Hayes and Brown. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 254-255,

38a

101 S.Ct. at 1094-95. Once Gulf produced evidence that

raised a genuine issue of fact as to its reasons for denying

Hayes and Brown promotions, it was up to Hayes and

Brown to show by a preponderance of the evidence, that

discrimination is the likeliest explanation for the fact that

they were not promoted to supervisory positions.

The district court held that the reason Hayes and

Brown were not promoted was their failure to inform the

company that they wished to be promoted. Plaintiffs

argue that this is a clearly erroneous finding because it is

supported by insufficient evidence. Plaintiffs maintain that

Gulf should have shown that only those who requested

promotion were promoted. Plaintiffs mistake the

allocation of burdens here. Once Gulf produced evident

to show what its business reasons were for not promoting

Mr. Hayes or Mr. Brown, it was up to the plaintiffs to

produce evidence to show that the reason given was a

sham. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 253, 255 n. 10, 101 S.Ct. at

39a

1095 n. 10. Plaintiffs argue that Gulfs reason for not

promoting Mr. Hayes or Mr. Brown was only asserted

through arguments of counsel. The issue was not merely

raised in the arguments of counsel, however, for there is

ample evidence in the record to support the district court’s

finding:

1. Mr. Hayes and Mr. Brown each testified that

they had told no one in authority of their interest

in becoming supervisors;

2. Mr. Draper testified that employees were invited

to inform supervisors of their interest in promotion;

3. There was no evidence that all employees

wanted to become supervisors; and

4. Mr. Brown’s testimony indicated he knew how

to express interest, but he chose to remain silent.

The district court’s finding that Mr. Hayes and Mr. Brown

were not promoted for non-discriminatory reasons is not

clearly erroneous.

40a

B. Tizeno

Mr. Tizeno did apply twice for a supervisory

position (once for a position as "planner" and once for a

position as "supervisor"). On remand the district court

found that Mr. Tizeno had established a prima facie case,

"although a weak one." The district court found that the

record as a whole did not support an inference that racial

discrimination was likelier than not the reason that Tizeno

was not promoted. Specifically, the district court found

that:

(1) Although Mr. Chesser, a white who was

promoted to planner, had less seniority than Mr.

Tizeno, Mr. Chesser also had less seniority than

most other pipefitters, including 108 who were

white, 80 of whom had greater seniority than Mr.

Tizeno as well.

(2) There was no evidence that Mr. Tizeno was

otherwise more qualified than Mr. Chesser.

(3) Several person, including 4 blacks were

appointed to supervisory positions in 1979, making

it hard to tell which position Mr. Tizeno did not

get. At that time Mr. Tizeno was one of the most

junior pipefitters.

41a

The district court was not clearly erroneous in its

determination that the reason Mr. Tizeno was not

promoted was not discriminatory.

V. Notification of Exclusion from the

Redefined Class

Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

requires a district court to give notice to absent class

members of developments in the suit in only two

situations:

The first is when the court certifies a class

under Rule 23(b)(3) because of common

questions of law or fact that predominate

over other aspects of the suit and render a

class action the appropriate vehicle to

resolve claims, (citation omitted). The

second is when a class action is to be

dismissed or compromised. Fed. R.Civ.P.

23(e).

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 673 F.2d 798, 812 cert,

denied, 459 U.S. 1038, 103 S.Ct. 451, 74 L.Ed.2d 605

(1982).

42a

Since this case involves the district court’s

modification of the class definition to exclude certain class

members, it does not fall within either of the foregoing

categories. Therefore, notification to those excluded

members was not mandated, but instead was left within

the discretion of the district court. Id. at 812. Although

discretionary notification is encouraged in those instances

where a plaintiff has shown that the excluded members:

(1) received notice of their initial inclusion in the class;

(2) relied on the class suit to protect their interests; and

(3) would be prejudiced as a practical matter by their

exclusion, Id. at 813, no such showing has been made by

the class herein. Therefore, we find that the district court

did not abuse its discretion in failing to give the excluded

class members notice of the redefinition of the class.

VI. Conclusion

After reviewing the massive amounts of evidence in

the record we find that the district court was not clearly

43a

erroneous in ruling that Stipulation 29 was not

purposefully discriminatory, and that even if it had an

adverse impact it was justified by legitimate business

purposes. Nor was the district court erroneous in finding

that the test Gulf used to determine which employees

were eligible for promotion were job related, based upon

the validation studies and expert testimony. The record

supports the district court’s determination that Mr. Brown

and Mr. Hayes did not show a prima facie case of

discrimination in Gulfs failure to promote them, and that

even if they made out a prima facie case, Gulf had shown

legitimate reasons for not promoting them. Likewise, the

district court was not clearly erroneous in holding that Mr.

Tizeno had not proved that Gulfs failure to promote him

was discriminatory. Accordingly, we AFFIRM.

44a

Wesley P. BERNARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

GULF OIL CORPORATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

No. 87-2033

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit

March 22, 1988

Rehearing Denied April 18, 1988.

Before SNEED*, REAVLEY and JOHNSON,

Circuit Judges.

REAVLEY, Circuit Judge:

This is a class action suit brought by six present or

retired black employees of Gulfs Port Arthur, Texas

Refinery, all of whom are or were members of the Oil,

*Circuit Judge of the Ninth Circuit, sitting by designation.

45a

Chemical and Atomic Workers’ International Union Local

4-23 ("OCAW”), against Gulf and the OCAW for

declaratory, injunctive, and monetary relief under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.,

and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981. The

suit was filed on May 18, 1976, within 90 days of plaintiffs

Bernard, Brown and Johnson’s receipt of right-to-sue

letters from the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (EEOC). Plaintiffs amended their complaint

to join as defendants other unions which represent

employees at the refinery, including: the International

Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, Port

Arthur Lodge No. 823; the International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers and its Local 390; the United

Transportation Union and its Local 1071; and the

International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftsmen

and its Local 13 (collectively referred to as the "Trade

Unions").

46a

In April 1976, Gulf and the EEOC entered into a

conciliation agreement in which Gulf agreed to cease

various allegedly discriminatory practices, to establish an

affirmative action program with respect to hiring and

promotion, and to offer backpay to alleged victims of

discrimination based on a set formula. Gulf sent notices

to the 632 employees eligible for backpay asking in return

for the execution of signed statements releasing Gulf from

any possible claims of employment discrimination

occurring before the date of the release, including any

future effects of past discrimination.

This suit was filed one month later seeking to

vindicate the rights of many of the employees who were

receiving settlement offers from Gulf under the concil

iation agreement. The district court entered an order

limiting communication by the named parties and their

counsel with prospective class members. This court,

sitting en banc, held that the order was an unconstitu-

47a

tional prior restraint on expression accorded First

Amendment protection. Bernard v, Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d

459 (5th Cir. 1980) (en banc), aff’d on other grounds, 452

U.S. 89, 101 S.Ct. 2193, 68 L.Ed.2d 693 (1981). On writ

of certiorari, the Supreme Court, while not reaching the

First Amendment issue, held that the district court’s order

was an abuse of discretion under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(d).

Gulf Oil v. Bernard, 452 U.S. 89, 101 S.Ct. 2193, 68

L.Ed.2d 693 (1981). The case was remanded to the

district court for further proceedings.

On January 24, 1983, the district court tentatively

and provisionally certified the class as all blacks who

worked or applied for work at the refinery in union

covered jobs at any time after December 26, 1966. On

April 2, 1984 the court modified the class to exclude

unsuccessful job applicants, employees not represented by

the OCAW, and employees who signed releases in

exchange for backpay under the conciliation agreement

48a

between Gulf and the EEOC. The court also limited the

relevant time period to employment practices occurring

between December 26, 1966, which is 180 days prior to

the date on which plaintiffs Bernard, Brown and Johnson

filed their charges of discrimination with the EEOC, and

May 18, 1976, the date upon which the complaint was

filed. The court dismissed the Trade Unions because

neither the named plaintiffs nor the modified class

contained members of these unions.

At trial, plaintiffs advanced a number of classwide

claims as well as individual claims on behalf of the named

plaintiffs. Plaintiffs contended that: Gulfs seniority system

was non-bona fide; a reclassification of employees

pursuant to a stipulation ("Stipulation 29") between Gulf

and the OCAW had an unlawfully discriminatory impact

on blacks; certain tests administered by Gulf had an

unlawfully discriminatory impact on blacks; Gulf inten

tionally applied its Sickness and Accident (S & A) policy

49a

to blacks in a discriminatory fashion; Gulf intentionally

discriminated against blacks in its selection of temporary

and permanent supervisors; Gulf intentionally

discriminated against the named plaintiffs; and the OCAW

breached its duty of fair representation. Following a

bench trial, the court held for Gulf and the OCAW on all

of the classwide and individual claims, 643 F. Supp. 1494.

On appeal, plaintiffs assert that the district court

incorrectly disposed of each of the classwide and

individual claims, but concede that the only issues upon

which the OCAW could be liable are those relating to the

seniority system and Stipulation 29. In addition, plaintiffs

contend that the district court improperly: decertified the

class to exclude employees who had signed releases;

dismissed the Trade Unions; and refused to consider

certain union and company records.

We hold that the district court failed to address

essential issues of the classwide claims concerning the

50a

seniority system, Stipulation 29 and the craft tests as well

as certain individual claims of intentional discrimination.

We therefore vacate the court’s judgment and remand for

further findings. We find no error in the other rulings,

which we now address.

I. Partial Decertification o f the Class, Dismissal

o f the Trade Unions, and Exclusion o f

Business Records

Plaintiffs challenge the district court’s partial

decertification order to the extent that it excluded from

the class employees who signed releases in exchange for

backpay under the conciliation agreement between Gulf

and the EEOC and dismissed the Trade Unions. The

basis for the court’s decision was its view that the named

plaintiffs lacked standing both to represent employees who

signed the releases and to pursue claims against the Trade

Unions.

In reaching its decision, the court noted that class

representatives must "possess the same interest and suffer

51a

the same injury" as the class members, Schlesinger v.

Reservists Committee to Stop the War, 418 U.S 208, 216, 94

S.Ct. 2925, 2930, 41 L.Ed.2d 706 (1974), and that a

plaintiff lacks standing to litigate injurious conduct to

which he was not subjected. Blum v. Yaretsky, 457 U.S.

991, 999, 102 S.Ct. 2777, 2783, 73 L.Ed.2d 534 (1982).

See Vuyanich v. Republic N atl Bank o f Dallas, 723 F,2d

1195, 1200 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 1073, 105 S.Ct.

567, 83 L.Ed.2d 507 (1984). Because none of the named

plaintiffs signed the releases or were members of the

Trade Unions, the court found that they lacked standing

to assert class claims on behalf of these employees.

Accordingly, the court limited the class to OCAW

members who had not signed releases, and dismissed the

Trade Unions,

Plaintiffs do not challenge the court’s exclusion of

non-OCAW employees, but instead challenge the dismissal

of the Trade Unions on the ground that these unions

52a

discriminatorily prevented black OCAW members from

transferring into jobs covered by these unions. The

district court found that plaintiffs did not allege that the

Trade Unions acted unlawfully against them. After

reviewing the complaint and amended complaints filed by

plaintiffs/ we find support for the district court’s

conclusion and hold that the Trade Unions were proper

ly dismissed.

Plaintiffs attack the validity of the releases on the

ground that they were obtained from employees during

the period when the district court’s order prevented

counsel for the class from communicating with prospective

class members. The validity of the releases, however, is

not at issue. Their validity can be attacked in a separate

1 Plaintiffs third amended complaint only alleges that the OCAW

and the Trade Unions "agreed to, acquiesced in, or otherwise

condoned the unlawful employment practices [of Gulf, as described in

the complaint]." It does not allege that the Trade Unions

independently discriminated against OCAW members.

53a

suit by employees who signed releases during the period

when the court’s order was in force.2 The question

presented to the district court was whether the named

plaintiffs had standing to represent employees who had

signed releases. Because the named plaintiffs sought to

obtain relief already obtained by employees who accepted

backpay and signed releases, the court found that the

plaintiffs lacked standing to represent these employees.2

We find no error in the court’s determination.

Plaintiffs complain of the trial court’s refusal to

consider documents, described as business records, which

plaintiffs say were given to the clerk during the trial. We

2 Only 33 of the 632 releases were signed during this period.

3The releases applied only to Gulf, not the OCAW. Plaintiffs

contend that even if they had no standing, with respect to Gulf, to

represent OCAW employees who had singed the releases, they did

have standing to represent these employees with respect to the

OCAW. We agree with the court’s finding that this argument is

without merit because the OCAW’s liability is dependent upon a

finding of liability against G ulf. See supra note 1.

54a

find the documents in the record, but they bear no file

stamp, and the transcript contains no reference to them.

The parties did not agree to their submission. Exhibits

come into evidence either by the agreement of the parties

or by offer, the laying of a predicate subject to counter by

the opposing party, and a ruling admitting the evidence by

the trial court. The court correctly disregarded documents

that were merely handed to the clerk.

II. Gulf’s Seniority System Under § 703(h)

Plaintiffs contend that Gulfs pre-Title VII Act

seniority system had a discriminatory impact on certain

black employees after the effective date of Title VTI and

that the defendants failed to prove that the seniority

system was bona fide under § 703(h). An examination of

Gulfs seniority system is necessary to resolve this claim

and plaintiffs’ next claim concerning Stipulation 29.

55a

A. Background

The Port Arthur refinery was established in 1903

and its labor force was not organized until 1943. Three

basic work related areas have existed at the refinery

throughout its history: operations, maintenance and labor.

The operations group manufactures and processes oil

based products and the maintenance group provides repair

and construction services. Both groups require skilled

employees and until 1954 only whites were hired into

them. The district court broadly used the term "craft" to

denote the operations and maintenance groups, their

employees, lines of progression and the departments and

divisions associated with operations and maintenance. We

adopt this usage generally, but use the more specific

labels where appropriate. The labor group is composed

of unskilled employees who assist the craft groups and

until 1956 was exclusively comprised of blacks.

56a

In 1943 the refinery was organized by the Oil

Workers International Union ("OWIU"), the predecessor

to the OCAW. At this time, many departments existed

and each was functionally related to operations or

maintenance. A loosely constructed labor department also

existed whose employees were assigned to these various

craft departments. Each of these departments had a line

of progression for its white employees which indicated the

promotional scheme from the entry level position to the

top position. It does not appear that clearly defined lines

of progression had been established for black laborers.

The articles of agreement between the OWIU and

Gulf incorporated the existing lines of progression. A

seniority system was established based upon plant

seniority, defined by the length of service at the refinery,

and promotions and demotions alone the lines of

progression were determined by seniority and ability to

perform. A six month residency in one’s particular job

57a

classification was a prerequisite to advancement to the

next highest job classification in a particular line of

progression. Two union locals were established, Local 23

which represented white employees and Local 254 which

represented black employees. Members of both locals

comprised the union negotiating team.

In 1950 the refinery had thirty-four* departments:

thirty-three craft departments5 and one labor department.

The labor department was composed of many subdepart

ments, and employees in these subdepartments were

assigned to work in twenty of the thirty-three craft

departments. Lines of progression had been established

in the labor subdepartments, and these lines generally

varied according to the structure of the craft departments

^Excluding the main office department.

5At least four of these departments were non-OCAW crafts;

bricklaying, electric shop, machine shop and transportation.

58a

to which they were assigned.6 This meant that the twenty

integrated craft departments functionally had two separate

lines of progression, one for their white employees and

the other for the black employees assigned to their depa

rtments from the labor subdepartments. These integrated

departments also had distinct seniority rosters reflecting

6The 1954 lines of progression show how this system operated.

At that time, the labor department was broken into ten

subdepartments, including: Acid Plant, Alchlor, Car Shop & Hoist,

Garage and Waste Oil, Lubricating, Package and Grease, Pressure

Stills, Main Office, Yard Division, and All Others. For most of these

subdepartments there was a corresponding craft department; for

example, there existed a separate acid department. The acid

department had a line of progression for its white employees; the

entry level position was called "Sulphur Recovery Plant Helper," and

the top position was called "Contact Operator." The labor subdepart

ment, entitled "Add Plant Department," had its own line of

progression, with the entry level position called "Laborer," and the top

position called "Utility Man No. 1." While technically part of the

labor department, this subdepartment actually worked with the (craft)

add department.

At least three of the labor subdepartments, Garage & Waste Oil,

Main Office, and Yard Division, did not work directly with any of the

craft departments. These subdepartments also had lines of

progression. The employees in the "All Other" labor subdepartment

worked with a number of craft departments and would move between

them as required. For example, these employees would work with the

pipefitting department for a few months, and then be assigned to

work with the boilermaking department when labor-type work arose

in that department. This subdepartment also had an established line

of progression.

59a

this division, one denoted "White" for its employees and

the other denoted "Colored" for the assigned labor sub

department employees.

Although black laborers worked in many of the

same departments as white craft employees, they could

not bid into the more desirable white lines of

progression. A gentlemen’s agreement, to which Gulf was

not a party,5 existed between Local 23 and Local 254

which prevented members of either local from bidding on

the jobs of the other. This agreement remained in force

until 1954, at which time it was temporarily suspended

due to pressure from black employees. Ten black

employees were permitted to enter white lines of

7The white lines of progression, were more desirable because they

paid more, had greater responsibility, and required more skill than the

black lines of progression.

o

Although this agreement was not incorporated into contracts

between the OCAW and Gulf, credible evidence that Gulf supported

and encouraged its enforcement was introduced.

60a

progression in 1954, but no further transfers were allowed

until 1956.

Between 1954 and 1956, the craft and labor

departments were assigned to one of two divisions. The

craft departments were assigned to the Operating and

Mechanical O & M Division, and the labor department,

with its various subdepartments, was assigned to the Labor

Division. The composition of these departments and

subdepartments and their lines of progression remained

basically unchanged. Approximately twenty of the craft

departments, now in the O & M Division, had labor

subdepartments assigned to them, and the two separate

lines of progression found in these integrated departments

before the adoption of the divisional system remained.

The labor department employees were technically in the

Labor Division even though they physically worked in craft

departments in the O & M Division. The labels on the

seniority rosters in these integrated departments were

61a

changed from "White" to "Operating and Mechanical

Division" and from "Colored" to "Labor Division."

As of 1956, both black and white employees

progressed up their promotional lines based on plant

seniority and ability to perform. Newly hired blacks would

be assigned to one of the labor subdepartments in the

Labor Division, while newly hired whites would be

assigned to one of the craft departments in the O & M

Division. The gentlemen’s agreement between the two

locals prevented blacks who progressed to the top

positions in their promotional lines from bidding into one

of the O & M Divisions lines of progression.9

The 1956 contract between Gulf and the OCAW

made the "Laborer" classification in the Labor Division

9We use the phase "O & M Division lines of progression" to

mean the various lines of progression in the craft departments, which

by 1956 had been assigned to the O & M Division. Similarly, we use

the phase "Labor Division lines of progression" to mean the various

lines of progression in the labor subdepartments which had been

assigned to the Labor Division.

62a

the entry level position for all employees, both black and

white/0 A high school diploma or its equivalent and

adequate performance on a number of tests were required

before one could gain employment. After progressing to

the top position in one of the Labor lines of progression,

an employee could transfer to an entry level position in

one of the O & M lines of progression after bidding into

the mechanical helper pool, which was a classification

apparently created to provide apprentice-type instruction

for employees entering an O & M line of progression/-^

10The "Laborer" classification before 1956 was the entry level

position for all of the lines of progression in the labor

subdepartments. Therefore, an employee hired as a laborer could

work with any one of the approximately twenty integrated craft

departments depending on the particular labor subdepartment to

which he was assigned. The 1956 contract made the laborer

classification the entry level position for all newly hired employees,

but did not otherwise change its nature.

11 For example, a black or white employee hired in 1956 into the

"All Other" Labor subdepartment would start as a Laborer. The

employees in this subdepartment worked with various craft

departments, such as pipefitting and boilermaking, as laborer related

work arose in these departments. The "All Other" labor

subdepartment had a particular line of progression and advancement

to the next highest job classification in that line was based on plant

seniority and ability to perform. The top labor position in this line

63a

Bids were selected on the basis of plant seniority. The

high school diploma test performance requirements were

applicable to transferees who had not previously fulfilled

these requirements because hired before 1956.

An employee who successfully bid into an O & M

line of progression was assigned dual seniority; O & M

Division seniority and plant seniority. Regardless of how

much plant seniority a transferee accumulated in the

Labor Division, he started with one day’s O & M Division

seniority for purposes of promotions and demotions in his

of progression was the "Utility Man Special," and once achieved, the

employee could bid into the mechanical helper pool.

The employee’s movement from the Utility Man Special position

to the mechanical helper pool resulted in the change of his divisional

classification from the Labor Division to the O & M Division. From

the mechanical helper pool, the employee could bid into one of the

craft department lines of progression, such as the pipefitting

department. The entry level job in this line of progression was the

"Pipefitter Helper." The employee would then promote through this

line of progression.

64a

particular O & M line of progression/2 Plant seniority

was important if workforce reductions occurred because a

transferee could use this seniority to return to the Labor

Division, where plant seniority determined promotions and

demotions within that Division.

The effect of this system on black employees hired

before 1956 is, in part, the basis for plaintiffs’ claim

concerning the seniority system. A black employee, hired

into the Labor Division in 1950 and who transferred to an

O & M line of progression in 1960, would have less O &

M Division seniority than a white employee hired in 1955

into the same O & M line of progression. For the

purpose of obtaining a promotion to the next highest job

12Using the example developed in footnote 11, on the day that

the employee became a Pipefitter Helper, he had only one days’

seniority for purposes of promoting to the next highest job classifica

tion in the pipefitting department’s line of progression. The Labor

Division seniority that he had accumulated as he progressed from a

Laborer to a Utility Man Special could not be used in the pipefit

ting department. This seniority was not totally forfeited: if workforce

reductions were required, the employee could be sent back to the "All

Other" labor subdepartment where his accumulated seniority would

dictate his position within that subdepartment.

65a

classification in the O & M line of progression, the black

transferee would have only one day’s divisional seniority,

compared to the white employee’s five years’ divisional

seniority. If workforce reductions were required in 1961,

then the black employee could be required to return to

the Labor Division, where his eleven years of plant

seniority would control his status in that Division.

In 1963, the one-day divisional seniority rule and

the high school diploma-^ and test performance

requirements were eliminated. Plant seniority became the

basis for all promotions, demotions and lay offs. The

effect of this change was that blacks with more plant

seniority, but less O & M Division seniority, than whites

in the same job classification could compete for

promotions to the next highest classification based upon

13A high school diploma was no longer required before one

could transfer from the Labor to the O & M Division; however, until

1971 a diploma was required for new employment.

66a

their longer plant seniority, thereby bypassing white

employees with greater O & M Division seniority.^ Also

in 1963, the two OCAW locals that had separately

represented black and white employees merged into Local

4-23, and the facilities at the refinery, such as bathrooms,

locker rooms, cafeterias and drinking fountains, were

integrated.

B. Analysis

Plaintiffs contend that Gulfs pre-Title VII Act

("pre-Act") seniority system had a discriminatory impact

on senior^5 black employees after the effective date of

u For example, a black hired in 1950 and who transferred to an

O & M line of progression in 1960 would, as of 1963, have 13 years

of plant seniority and 3 years of O & M Division seniority. A white

hired in 1955 into the same O & M line of progression would, as of

1963, have 8 years of both plant and divisional seniority. If the black

and white employee were in the same job classification and a vacancy

opened in the next highest job classification, then, as between these

employees, the black, with his 13 years of plant seniority, would be

the senior bidder.

15We use the term "senior" to denote black employees hired

before 1956. Plaintiffs’ claim concerning Gulfs seniority system, and

their next claim concerning Stipulation 29, relate only to employees

hired before 1956.

67a

Title V Il/6 and that the defendants failed to prove that

the seniority system was bona fide under § 703(h).

Before examining plaintiffs’ contentions, we review the

relevant law.

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a), proscribes

discriminatory employment practices, including

discrimination "with respect to . . . compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment" on the basis of

race. Section 703(h) insulates bona fide seniority systems

from the dictates of § 703(a), by providing that,

[n]ot withstanding any other provision of this

subchapter, it shall not be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer to apply different

standards of compensation, or different terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment pursuant

to a bona fide seniority or merit system, . .

provided that such differences are not the result of

an intention to discriminate because of race, color

16July 2, 1965.

68a

Until the Teamsters decision in 1977, International

Brotherhood o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

97 S.Ct. 1843, 52 L.Ed.2d 396 (1977), courts generally

rejected the contention that if an employer ceased all

discriminatory practices on the effective date of the Act

and had a seniority system that was facially neutral, then

the system was necessarily protected under § 703(h). See

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-

CIO, CLC v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919, 90 S.Ct. 926, 25 L.Ed.2d 100

(1970); Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505

(E.D. Va. 1968). The Quarles court held that a seniority

system that perpetuated, or locked in, the effects of past

discrimination was not bona fide, and concluded that

"Congress did not intend to freeze an entire generation of

Negro employees into discriminatory patterns that existed

before the act." Quarles, 279 F. Supp. at 516.

69a

The Supreme Court rejected this reasoning in

Teamsters. In that case, the Court found systematic and

purposeful discrimination in hiring, assignment, transfer

and promotion policies before and after the effective date