Letter From James Blacksher to Charles Arendall with List of Plaintiffs' Witnesses

Public Court Documents

February 2, 1976

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Letter From James Blacksher to Charles Arendall with List of Plaintiffs' Witnesses, 1976. 043b3db2-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/61db3914-faaa-4a0b-a5f0-25f0fcf487a2/letter-from-james-blacksher-to-charles-arendall-with-list-of-plaintiffs-witnesses. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

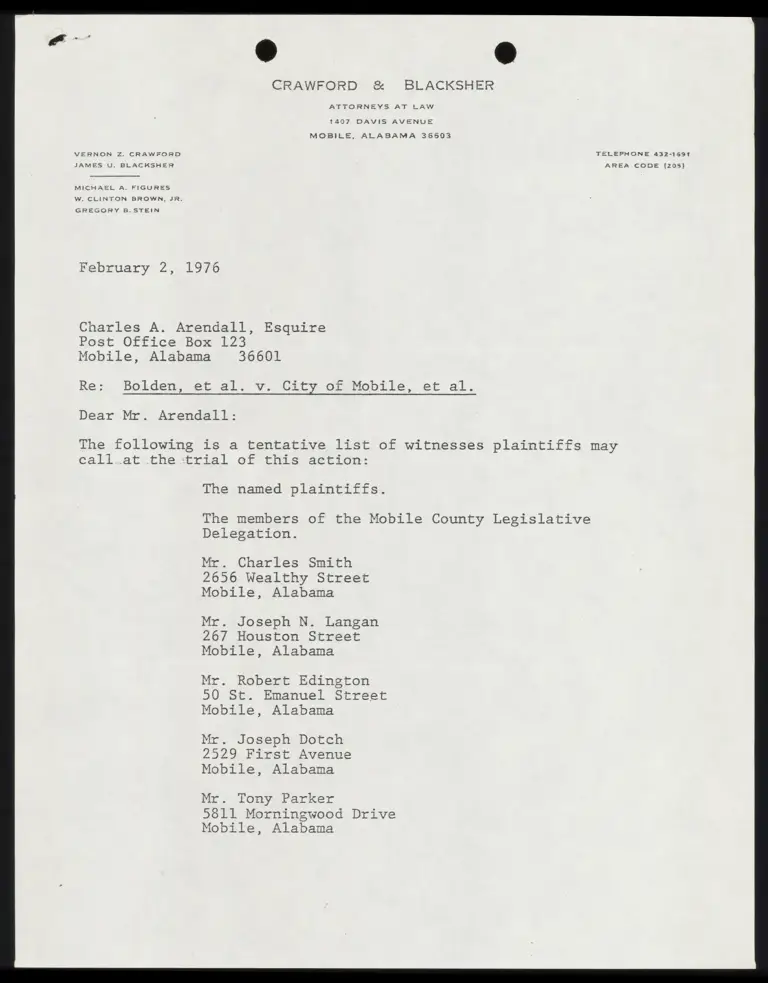

CRAWFORD & BLACKSHER

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36503

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD TELEPHONE 432-1591

JAMES U. BLACKSHER AREA CODE (205)

MICHAEL A. FIGURES

W. CLINTON BROWN, JR.

GREGORY B. STEIN

February 2, 1976

Charles A. Arendall, Esquire

Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Re: Bolden, et al. v. City of Mobile, et al.

Dear Mr. Arendall:

The following is a tentative list of witnesses plaintiffs may

call .at the: trial of this action:

The named plaintiffs.

The members of the Mobile County Legislative

Delegation.

Mr. Charles Smith

2656 Wealthy Street

Mobile, Alabama

Mr. Joseph N. Langan

267 Houston Street

Mobile, Alabama

Mr. Robert Edington

50 St. Emanuel Street

Mobile, Alabama

Mr. Joseph Dotch

2529 First Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

Mr. Tony Parker

5811 Morningwood Drive

Mobile, Alabama

February 2, 1976

harles A. Arendall, Esquire

Page 2.

Dr. B, HW. Gilliard

2423 North Creek Circle Drive

Mobile, Alabama

Dr. James Voyles

Spring Hill College

Mobile, Alabama

Dr. Charles Cotrell

St. Mary's University

2700 Cincinnati Avenue

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Melton McLaurin

University of South Alabama

Mobile, Alabama

Dr. Cort B. Schlichting

Spring Hill College

Mobile, Alabama

Plaintiffs reserve the right timely to supplement this list of

potential witnesses.

Best regards.

Sincerely,

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

/ [1 a

ai

JY U. Blacksher

JUB:bm

cc: ‘William J. O'Connor, Clerk

Charles Williams, Esquire

Edward Still, Esquire