Correspondence from McCrary to Guinier

Correspondence

February 7, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Correspondence from McCrary to Guinier, 1983. 34fcc4b6-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/61db4fd9-76af-4f5b-b568-c068253c5000/correspondence-from-mccrary-to-guinier. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

t

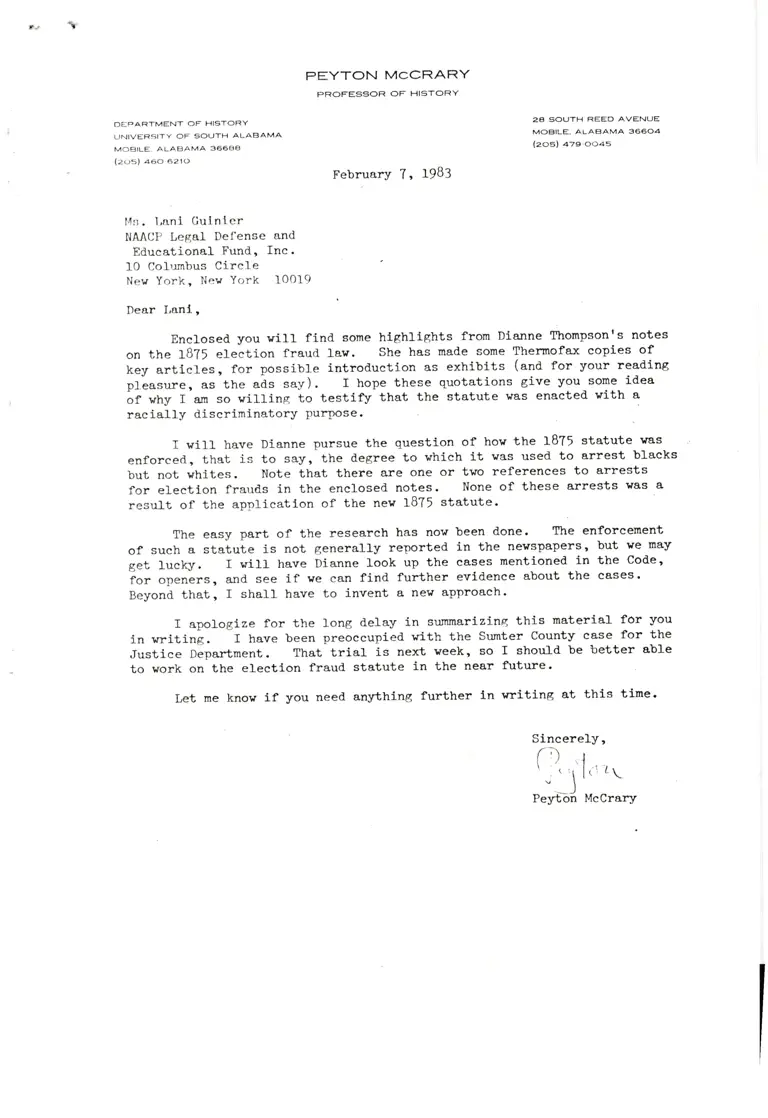

PEYTON MCCRARY

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

r)EPARTMENT OF HISTORY

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH .ALABAMA

M()BILE. ALABAMA 36644

(2os) 460 62lo

2A SOUTH REED AVENUE

MOBILE. ALABAMA 36504

(zosl 479'oo45

February T, ]-9B3

l4s. Lanl Oulnler

NMCP Lega1 Defense and

Edueational Fund, Ine.

10 Columbus Cirele

Nev York, Nev York 10019

Dear Lanl,

EneLosed you wilt find sone htghllghts from Dianne Thompsonrs notes

on the tB?5 etection fraud 1as. She has made some Thermofa:c copies of

key artieles, for possible introduetion as exhiblts (and for your reading

ptlasure, as the aas say). I hope these quotations give you some idea

of ,ny I an so villing to testif! that the statute was enaeted vith a

racially diseriminatory Purpose.

I viII have Dianne pursue the questlon of how the t8?5 statute vas

enforced, that is to say, the degree to vhieh it vas used to arrest blacks

but not whites. Note that there are one or tvo references to arrests

for eleetlon frauds in the enelosecl notes. None of these arrests vas a

result of the applicatlon of the ner 18?5 statute.

The easy part of the researeh has now been done. Ttre enforcenent

of sueh a statute is not generally reported in the newspapers, but we may

get ]uclry. I will have Dianne look up the eases mentioned tn the Code'

io" op"n"rs, and. see if we can find further evldenee about the cases'

Beyond that, I shall have to invent a nev approaeh'

I apologize for the long deIay ln sunxnarizlng this naterial- for you

in vrltinL. I have been preoecupied rrith the Sumter County case for the

Justiee Departnent. That trlal is nert week, so I should be better able

to work on the electlon fraud statute ln the near firture.

Let me know lf you need anything further ln rriting at thls time.

Sineerely,

r.l

i1(1

z \

peyt-J Mecrary

Mobile Da1ly Reglster

Mareh 6, ].875, p. 1. Lgrrm FRoM MoNTGoMERY. Rep. James Greene elted

the eLectlon fraud blIl as more evl.dence of "the proscription of Republicans

in the State.rr He also contended that having one box for federal elections

and. another for state eleetions was designed to confuse black voters.

(Greene is a black legislator. )

Leter, during the campaign to call a new constititional convention (vhlch

sueceeded), the Demoeratic and Consenrative Exeeutive Comnittee of Alabama

included the folloving eomment ln its Address to the Voters:

July-?3,.L875, P. 3. "You may obJect to having to vote in a beat /electionprecinct/, but there can be no fair election in the Black BeIt vith&t tlat,

and' in your general elections do you deslre to be cheated out of the election

of 'cancliclates of your choice by fraudulent voting?"

Mobile Dally Reglster

Jan. 9, 187r, p. 2. WTIITE'S ELECTION BILL. "It is undoubtedly the purpose

of'the Alabama legislature to enact an Election Lav vhich will prevent

hereafter the great frauds which have been committed with the negro vote.

The voter vilI hereafter be compelled to vote ln the precinct in whlch he

resid.es, ln ord.er that lt may clearly be knovn that he is a 1ega1 voter, and.

to prevent the lntimidation and terrorism to which he is subJected by the

carpetbaggers /siclf , uho hold their League and NationaL Guard. meetings at

the county seats. l.Ie intend to break up the practice under vhich the

ad.venturers have collected. their dupes at the country ehurches, marched. them

in a:med bodies to the county seat, placed tickets in their hand.s, and

lnstructed. them hov to vote."

Jan. 17, 1B?r, p. 1. LETTER FROM MONTGOI\.{ERY. "The negroes opposed. a suspension

of the rules in a number of cases, ln order that biIl,s might not go to a second

reading. . . . Any bi11s affecting the conduct of elections in any loca11ty

or the agricultural lnterests of the state, or punishment for the commission

of a crime, invariably meet with obJeetions."

Jan.28, 1875. ELECTION LAw. "1,1r. Cobb has introduced. in the Senate a

general election bill, vith nany changes from the present lav.t' Among the

changes summarized. are the requirement that voters east ballots only in

the vard where they reside, a provlsion allowlng any quallfied voter to

challenge anotherrs right to vote at the polls, the eliminatlon of "obnoxious

features about lntimidation, simulation of ballots, ete.r" and a provision

giving election officials free rein to stuff ba1lot boxes, vhich reads as

follovs: "The ballots are retained by the inspectors in the several wards

or precinets, and only the eertiflcates and poll lists are forwarded to the

Frobate Judge, who . shall open and count the returns."

Jan.29, f87r, p. L. BY TELEGMPH FROM MONTGOI\mRY. In the House Datus Coon

of Selma introduced. a biLl to enforce the right to vote in Alabarna by

regulating punislunents of voters for election fraud. (fn other vord.s, the

Republicans elearly sav the election fraud. bill sponsored by the Denocrats --

the one which passed and under whlch Ms. i}oseman and Ms. Wilder vere found

guilty -- as a partisan statute which vas likely to be enforeed in a raclally

d.iscriminatory manner. )

Feb 7 , L875, , p. \. LIfITER FROM l,lONTGoMiRY. Committee on Privileges

and Elections reports a nev version of the election b111, includlng among

other changes a new seetion 38: "that any person voting more than once is

gullty of a felony."

l'eb. 27, l.t)T5, p. I. I.l,;l"l'1,;R l'lloM MoN'l'(;oM.l':llY. 'l'tre rlelrrrL(: over Llre l'rrllrd-

ufent votlng btll ln the llouse lncludes "vlolenL opposltlon from the Rcrdlcal

members." Among other issues, Rep. Coon argued that "the biII vould

prevent the free exerclse of the bal-lot in that negroes would be lnfluenced

and lntimlclated by their employers who vote in the s&me preelncL vlth them,

vhile this vould not be the case lf they were aLloved to go ln a bo<ly to

such points as they preferred.rl

Mobile Daily Register

Noy. 3, IBTI+, p. 2. 'Ve varrr the fraudulently registered ne8roes that they

are marked; that there is a clifference between registering and voting, and

iu.voting iI1ega1Iy they viII go from the poIls to prison."

Nov. l+, 1B?\, p. 1. THE ELECTION. The Register reports 300 "fraudulent

votes poIled by Negroes who escaped being arrested.r" but also notes that

lrO-50 Negroes vere imprlsoned. for "repeating." Among these vere 2 or 3

ttcol-ored" U. S. Deputy Marshals.

Nov. 5, 18?\, p. 1. THE COURTS. "A negro named. Henry Willians vas

arraigned, for illegal voting."

Nov. 7, lBTl+, p. 1. The char8es of illegal voting against Henry Williams

were d.ropped. for lack of evidence.

Nov. I\, lBTl+, p-. 2. OUR CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT. "The apparent vote for

Jere Haralson /a bLack Republicail Ln thls congressional district is 19,r51.

The vote for Mr. Bromberg /white Republican Frederlck Bromberg of the

"Bromberg letterY is 16 r9r3. This gives Jere an apparent naJorlty of

21598. The vote for Haralson is evidently frauciulent."

Nov. 20, t8?l+, p. 2. 1'tre Register mentions

deslgned. to prevent voter fraud-m'is refers

also ineluded the first unequlvocal provision

Mobile city government ).

a Mobile voter registration law

to a portion of the statute that

for at-Iarge elections for the

Nov. 29, lBTL, p. 2. Rep. And.erson (f ) spoke in the House in favor of

the b111 regulating nunicipal electlons in Mobile. He said the bill was

tntended to rid the people of Mobile of "the notorious and admltted frauds

in public elections and the d.isorders, d.emoralizatlon, and other great

evlls flowlng from sueh fraucls. t' Exlsting laws dld not penallze election

fraud. in Mobile, he contended, adding that state election lavs in general

were ln neecl of revision to deal with this problem.

Dec . 2, 18?l+, p. 1. oun MoNTGoImRY LETTER. f'ft is sald that the Rad.icals

have detennlned ln caueus to vote against prolonging the session, whieh, if

true, will . prevent the passage of an electlon law and revenue 1aw."

Dec. 6, 1B?l+, p. 2. PREPARE FOR ACTION. ,Under the nev munlclpal electton

1aw for Mobile, elections vere to be held vlthln a fev rlays, promptlng the

Register to urge vhite men "under the banner of the rDemocratie and Conserva-

tive organizationt" to be "true to tfreir colors" and vrest city government

"from the hands of the nergoes and ballot-box stuffers."

Dec. 15, lBTl+, p. \. I'rom Montgomery. In reference to the Motrlle clty

electlon (prevlously held), Datus Coon, a vhlte Republlcan from Dallas CounLy,

presented a petitlon from a Mobile Republlcan, I'etatlng that 1,000 col.ored

Republicans ln the Seventh Ward vere dlsfranchlsed under the new election

law.r' The communicatlon from Moblle lncluded the charge that "the registratlon

nas conducted slowly by design, and that voters couldn't register." The

author of the comrunicatlon, one Ben Lane Posey, asked Rep. Coon to lntroduce

a b111 correcting thls situation if Mr. And.erson (from Mobile) vould not.

llontgomery Daily Advertieer

Nov.. II, lBTl+, p. I. "The lst Distrlct remalns in doubt. The Negroes

stuffed 1,000 fraudulent votes in an obscure box of Dallas County."

Nov. 25, lBTl+, p. 2. "Russe11, a Tuskaloosa negro, vho voted in the last

electlon there ilIegaI1y, has been tried, convicted, and. sentenced. to the

penitentiary for two years."

Dec. 12, lBTh, p. 1. From the Florence Journal. "The present legislature

owes it to the good of the comnonvealth to enact a Iav looking to the

suppression of ilIegaI voting. A lav should be passed alloving no man

to vote save in his ovn preelnet. Under the exlsttng laws, enaeted ln the

lnterest of the Radical party, the ner6loes can easlly fo]=Iow the teachinfls

of Boss Spencer /U. S. Sen. George Spencer, a Republican/ -- rto vote early

and vote often.I Should a lav &s ve have suggested be passed, the negroes

would most probably be knovn to the challengers. Such a Iav, curtailing

or d.bridging the rights and privileges of none, vould, be highly satisfactory

to the friend.s of good. government throughout the state."

March 3, 18Tr, p. 2. ALABAMA LEGTSLATURE. The folrowing is a defense of

the election fraud bill by a vhite Denocrat named Jerrell (f) or Ferrell (?)

vho says:

t'It is an established fact that a vhite m&n cannot easily vote more

than once at one eleetion -- they are generally knovn -- they do not

all look aIike, and, in many cases, for the past ten years, courts,not of

their own selection vere only too glad to trump up such charges."

March ,, 1875, p. 3. "Governor Houston has approved the new election law

for the state. Good-bye to negro repeatlng and paeking of negroes around

the courthouse on election day."