Gulf Oil Company v. Bernard Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gulf Oil Company v. Bernard Joint Appendix, 1980. 83bcdfef-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/61ff6d86-4c0f-4d00-a0e7-ac5f494af4c5/gulf-oil-company-v-bernard-joint-appendix. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

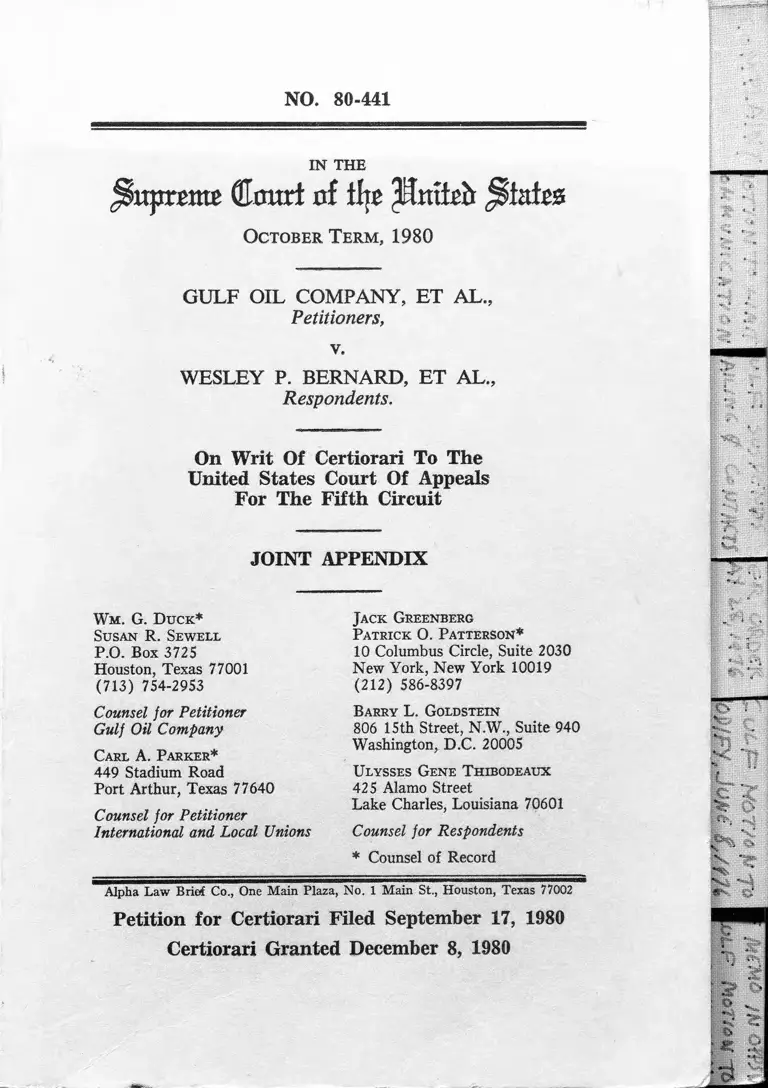

NO. 80-441

IN THE

jiuprattp Court of iht ffinihb

October Term, 1980

GULF OIL COMPANY, ET AL„

Petitioners,

v.

WESLEY P. BERNARD, ET AL.,

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals

For The Fifth Circuit

JOINT APPENDIX

Wm. G. D uck*

Susan R. Sewell

P.O. Box 3725

Houston, Texas 77001

(713) 754-2953

Counsel for Petitioner

Gulf Oil Company

Gael A. P arker*

449 Stadium Road

Port Arthur, Texas 77640

Counsel for Petitioner

International and Local Unions

J ack Greenberg

P atrick O. P atterson*

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Barry L. Goldstein

806 15th Street, N.W., Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

Ulysses Gene T hibodeaux

425 Alamo Street

Lake Charles, Louisiana 70601

Counsel for Respondents

* Counsel of Record

Alpha Law Brief Co., One Main Plaza, No. 1 Main St., Houston, Texas 77002

Petition for Certiorari Filed September 17, 1980

Certiorari Granted December 8, 1980

""

l

- 7\

a

<' I

r ‘, ,

* ■ ■.

'^rrn

:Y::- f

5 I

h Xcy

•Sf

fest -4

INDEX

Chronological List of Relevant Docket Entries ....................

All Docket Entries .................................................................

Complaint, Filed May 18, 1976 ..............................................

Motion By Gulf To Limit Communications With Any Po

tential or Actual Class Member, Filed May 27, 1976 . . .

Memorandum in Support of Gulf’s Motion To Limit

Communications With Any Potential or Actual Class

Member .........................................................................

Exhibit A—Agreement Between the U. S. Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission, Gulf Oil Com

pany—U.S. and Office For Equal Opportunity, U.S.

Department of the Interior, dated April 14, 1976 . . .

Exhibit A—List of employees (Omitted)

Exhibit B—List of Employees (Omitted)

Exhibit B—Letter from William G. Duck to be read to

Actual or Potential Class Members, dated May 25,

1976 ...............................................................................

First Order Limiting Communications With Any Potential

or Actual Class Member, Filed May 28, 1976 ................

Motion of Gulf Oil Corporation To Modify Order Limiting

Communications, Filed June 8, 1976 ................................

Memorandum in Support of Gulf Oil Corporation’s

Motion to Modify Order ............................................

Exhibit A—Agreement Between the U. S. Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission, Gulf Oil Com

pany—U.S. and Office For Equal Opportunity, U.S.

Department of the Interior, dated April 14, 1976 ..

Exhibit A—List of Employees (Omitted)

Exhibit B—List of Employees (Omitted)

Exhibit B—Letter from William G. Duck to be read to

Actual or Potential Class Members, dated May 25,

1976 ...............................................................................

Exhibit C—Affidavit of Herbert C. McClees, dated

June 3, 1976 .................................................................

Exhibit D—Affidavit of Gerald C. Williams—June 4,

1976 ...............................................................................

II

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law In Opposition To Defend

ant Gulf Oil Company’s Motion To Limit Communica

tions With Any Potential or Actual Class Member, Filed

June 10, 1976 ....................................................................... 80

Exhibit A—Copy of First Order Limiting Communica

tions (Omitted)

Exhibit B—Opinions and Orders in Jimmy L. Rogers

and John A. Turner v. United States Steel Corpora

tion, et al. v. Honorable Hubert I. Teitelbaum,

United States Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit,

No. 76-1340 (Omitted)

Exhibit C—Letter from Equal Employment Opportun

ity Commission to Wesley Bernard, dated February

25, 1975 (Omitted)

First Supplemental Memorandum In Support of Gulf Oil

Corporation’s Motion To Modify Order, Filed June 16,

1976 ....................................................................................... 92

Exhibit A—§ 1.41 of Manual for Complex Litigation . . 97

Exhibit B and Appendix I—Proposed Order to Limit

Communications ........................................................... 99

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law in Opposition To Defend

ant Gulf Oil Company’s Motion To Modify Order, Filed

June 17, 1976 ............................................................................. 105

Exhibit A—Affidavit of Barry L. Goldstein, dated June

16, 1976 ............................................................................. I l l

Exhibit B—Affidavit of Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux,

dated June 16, 1976 ......................................................... 115

Exhibit C—Affidavit of Stella M. Morrison, dated

June 17, 1976 ..................................................................... 118

Motion By Defendant, Gulf Oil Corporation To Dismiss

Complaint, Filed June 17, 1976 ............................................ 121

Order Granting Motion of Gulf Oil Corporation To Modify

First Order Limiting Communications, Filed June 22,

1976 ............................................................................................. 124

Appendix I—Notice from Clerk of Court to Employees

Receiving Conciliation Benefits ......................................... 128

Ill

Page

Plaintiffs’ Motion For Permission To Communicate With

Members of the Proposed Class, Filed July 6, 1976 ........ 130

Exhibit A—Proposed Notice To Potential Class Mem

bers ................................................................. 1^2

Exhibit B—Order Limiting Communications, Filed

June 22, 1976 (Omitted)

Memorandum of Law In Support of Plaintiffs’ Motion

For Permission To Communicate With Members of

the Proposed C lass......................................................... 134

Memorandum On Behalf of Gulf Oil Corporation In Opposi

tion To Plaintiffs’ Motion For Permission To Communi

cate With Members of the Proposed Class, Filed July

IS, 1976 .............................................................................. 139

Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint, Filed July 19, 1976 ........... 146

Exhibit A—Notice of Right to Sue Within Ninety Days

to Wesley P. Bernard, dated June 11, 1976 .............. 155

Exhibit B—Notice of Right to Sue Within Ninety Days

to Hence Brown, Jr., dated June 11, 1976 ................ 156

Order Denying Plaintiffs’ Motion For Permission To Com

municate With the Proposed Class, Filed August 10, 1976 157

Report to the Court by Gulf Oil Corporation of Individuals

Who Have Accepted Benefits Under the Conciliation

Agreement, Filed September 2, 1976 .................................... 158

Exhibit A—List of Employees Who Accepted Concilia

tion Benefits ................................................................. 160

Exhibit B—List of Employees Who Failed to Accept

Conciliation Benefits ................................................. 168

Order Granting Summary Judgment For the Defendants,

Filed January 11, 1977 . ................ 170

Opinion of Court of Appeals, Filed June 15, 1979 .............. 175

Order Granting Rehearing En Banc, Filed September 27,

1979 ....................................................................................... 229

Opinion of Court of Appeals En Banc, Filed June 19, 1980 231

Judgment of Court of Appeals Rehearing En Banc, Filed

July 17, 1980 ....................................................................... 277

Order of Supreme Court of the United States allowing Cer

tiorari, Filed December 8, 1980 ............................................ 279

1

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

May 18, 1976— Plaintiffs’ original petition filed in U.S.

District Court for Eastern District of Texas, Beaumont

Division.

May 27, 1976—Defendant Gulfs motion to limit com

munications with any potential or actual class member

filed.

May 28, 1976— Order signed by Judge Steger limiting

communications with any potential or actual class mem

bers.

June 8, 1976—Defendant Gulfs motion to modify

order limiting communications filed.

_r) June 11, 1976—Hearing held on motion to modify

' order limiting communications.

June 17, 1976—Motion by defendant Gulf Oil Cor

poration to dismiss complaint filed.

June 22, 1976—Order entered by Judge Fisher modify

ing Judge Steger’s order limiting communications with

any potential or actual class members.

June 30, 1976—Notice mailed to Gulfs Port Arthur,

Texas, refinery employees as per order of June 22, 1976.

July 1, 1976—Plaintiff’s motion to amend complaint

filed.

July 6, 1976—Plaintiffs’ motion for permission to com

municate with members of the proposed class filed.

July 19, 1976—Order entered permitting plaintiffs to

file amended complaint.

July 28, 1976—Motion by defendant Gulf Oil Cor

poration to dismiss amended complaint filed.

July 30, 1976—Defendant Oil Chemical and Atomic

Workers’ International Union, Local Union No. 4-23,

response to plaintiffs’ amended complaint filed.

2

August 10, 1976—Order entered denying plaintiffs’

motion for permission to communicate with the proposed

class.

August 25, 1976—Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers

International Union and Local No. 4-23 of the OCAW

joins defendant Gulf Oil Company in its motion to

dismiss.

September 2, 1976— Report to the court by Gulf Oil

Corporation of individuals who have accepted benefits

under the conciliation agreement.

September 24, 1976—Hearing held on defendant’s

motion to dismiss.

November 29, 1976—Order entered that motion to

dismiss filed by defendant shall be treated as motion for

summary judgment and that parties should submit all

pertinent materials to said motion by January 3, 1977.

January 11, 1977-—Order that summary judgment be

granted for the defendants as to both the class action

and any individual claims of discrimination by the plain

tiffs.

February 9, 1977—Plaintiffs’ notice of appeal filed.

June 15, 1979—Opinion of the Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit.

September 27, 1979—Order entered granting rehear

ing en banc in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

June 19, 1980—Opinion of the Court of Appeals

en banc.

July 17, 1980—Judgment of Court of Appeals re

hearing en banc.

December 8, 1980—Order entered by Supreme Court

of the United States allowing certiorari.

3

5-25-76

5-27-76

5-27-76

5-28-76

5- 28-76

6- 7-76

DATE

5-18-76

DOCKET ENTRIES

NR. PROCEEDINGS

I COMPLAINT

Issued Summons and delivered to

U. S. Marshal, Beaumont, Texas.

II Marshal’s Return on Summons to Gulf

Oil Company, served to R. B. Short,

Ref, Manager, on 5-24-76 at 3:50

p.m. $9.00

12 MOTION by Gulf to Limit Communi

cations with any Potential or Actual

Class Member submitted by Atty.,

Joseph H. Sperry for Defendant,

Gulf Oil Company.

16 MEMORANDUM in Support of Gulfs

Motion to Limit Communications

with any Potential or Actual Class

Member.

20 ORDER signed by Judge Steger on Mo

tion by Gulf to Limit Communica

tions with any potential or actual

class member. This ORDER shall be

effective until Judge Fisher returns

and can hear the matter upon formal

motion. Attys. of Record apprised.

V.74.P.10

22 Marshal’s Return on Summons, served

to Mr. Parker on 5-26-76 at 12:10

p.m. $9.00

Hearing on Motion by Gulf Oil to Limit

Communications with any potential

or actual class member for Friday,

June 11, at 10:00 a.m. by Judge

Fisher. Attys. of Record notified by

telephone Monday, June 7, 1976, and

follow-up letter.

4

DATE NR. PROCEEDINGS

6-8-76 23 NOTICE OF MOTION TO MODIFY

ORDER by Defendant.

6-8-76 24 MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF

GULF OIL CORPORATION’S MO

TION TO MODIFY ORDER.

6-8-76 38 MOTION TO MODIFY ORDER.

Attys. of Record apprised.

6-10-76 40 MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OP

POSITION TO DEFENDANT GULF

OIL COMPANY’S MOTION TO

LIMIT COMMUNICATIONS WITH

ANY POTENTIAL OR ACTUAL

CLASS MEMBER, by Plaintiff.

6-10-76 81 Defendant, Oil, Chemical and Atomic

Workers International Union, Local

Union No. 4-23 Response to Plain

tiff’s ORIGINAL COMPLAINT.

6-16-76 85 FIRST SUPPLEMENTAL MEMO

RANDUM IN SUPPORT OF GULF’s

MOTION TO MODIFY ORDER.

6-17-76 97 MOTION by Defendant Gulf Oil Cor

poration to Dismiss Complaint. At

torneys of Record apprised.

6-17-76 99 MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OP

POSITION TO DEFENDANT GULF

OIL COMPANY’S MOTION TO

MODIFY ORDER, by Plaintiff.

6-22-76 117 ORDER that motion of Gulf Oil Cor-

poration to modify Judge Steger’s Or

der is granted and that Judge Steger’s

Order of May 28, 1976 be modified.

s/Judge Fisher. Attorneys of record

apprised. V.74JP.

5

6- 30-76

7- 6-76

7-6-76

7-15-76

7-19-76

7-19-76

7- 28-76

8- 6-76

DATE

7-1-76

7-1-76

123 MOTION to Amend Complaint.

125 MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUP

PORT of Plaintiffs’ Motion to Amend.

128a- Notice (Appendix I) mailed to Port1

128e Arthur, Texas Gulf Refinery employ

ees as per Order of June 22, 1976.

129 MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO

COMMUNICATE WITH MEM

BERS OF THE PROPOSED CLASS

by Plaintiffs. Attys. of Record ap

prised.

135 MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUP

PORT OF PLAINTIFF’S MOTION

FOR PERMISSION TO COMMUNI

CATE WITH MEMBERS OF THE

PROPOSED CLASS.

142 MEMORANDUM ON BEHALF OF

GULF OIL CORPORATION IN

OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO

COMMUNICATE WITH MEMBERS

OF THE PROPOSED CLASS.

150 ORDER granting Plaintiff’s MOTION

TO AMEND COMPLAINT. s/Judge

Fisher. Attys. of Record Apprised.

V.75,P.44

151 AMENDED COMPLAINT by Plaintiff.

162 MOTION BY DEFENDANT GULF

OIL CORPORATION TO DISMISS

AMENDED COMPLAINT. Attys. of

Record apprised.

164 MEMORANDUM in Support of De

fendant, Gulf Oil Corporation’s, Mo

tion to Dismiss Amended Complaint.

NR. PROCEEDINGS

6

DATE NR. PROCEEDINGS

8-6-76 204 AFFIDAVIT OF NACHA I. MARTI

NEZ with reference to Willie John

son, Sr.

8-6-76 208 AFFIDAVIT OF NACHA I. MARTI

NEZ with reference to Elton Hayes,

Sr.

8-6-76 210 AFFIDAVIT OF NACHA I. MARTI

NEZ with reference to Rodney Ti-

zeno.

8-6-76 212 AFFIDAVIT OF NACHA I. MARTI

NEZ with reference to Wesley P.

Bernard.

8-6-76 216 AFFIDAVIT OF NACHA I. MARTI

NEZ with reference to Willie Whitley.

8-6-76 222 AFFIDAVIT OF HERBERT C. Mc-

CLEES with reference to Willie Whit

ley.

8-6-76 228 AFFIDAVIT OF HERBERT C. Mc-

CLEES with reference to Willie John

son, Sr.

8-6-76 231 AFFIDAVIT OF HERBERT C. Mc-

CLEES with reference to Hence

Brown.

8-6-76 234 AFFIDAVIT OF NACHA I. MARTI

NEZ with reference to Hence Brown.

8-6-76 238 AFFIDAVIT OF HERBERT C. Mc-

CLEES with reference to Wesley

Bernard.

8-30-76 241 DEFENDANT, OIL, CHEMICAL AND

ATOMIC WORKERS’ INTERNA

TIONAL UNION, LOCAL UNION

NO. 4-23 RESPONSE TO PLAIN

TIFFS’ AMENDED COMPLAINT.

8-20-76

8- 25-76

9- 2-76

9-2-76

9-14-76

9-24-76

DATE

8-10-76 245 ORDER on Plaintiffs’ Motion for Per

mission to Communicate with the

Proposed Class is DENIED. s/Judge

Fisher. Attorneys of Record apprised.

V.75,P.142

246 MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OPPO

SITION TO DEFENDANT GULF

OIL COMPANY’S MOTION TO

DISMISS AMENDED COMPLAINT.

256 OIL, CHEMICAL AND ATOMIC

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UN

ION, AND LOCAL 4-23 of the

OCAW joins, Defendant, Gulf Oil

Company, in its MOTION TO DIS

MISS. Attys. of Record apprised.

258 REPORT TO THE COURT BY GULF

OIL CORPORATION OF INDIVID

UALS WHO HAVE ACCEPTED

BENEFITS UNDER THE CONCI

LIATION AGREEMENT.

273 MOTION FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

ON GULF’S MOTION TO DISMISS.

Attys. of Record apprised.

274 ORDER that oral arguments on Gulfs

Motion to Dismiss will be set on

September 24, 1976 at 10:00 a.m.

Signed by Judge Fisher. Attys. of

Record apprised. V.76,P.77

Hearing held on Defendant’s Motion to

Dismiss. Motion taken under Advise

ment. Counsel given to 10-15-76 to

file Memoranda or Briefs: Deft, given

to 10-22-76 to file proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law and

7

NR. PROCEEDINGS

8

9- 23-76

10- 7-76

10-18-76

10-15-76

10-15-76

10-14-76

10-26-76

DATE

Pltf given to 10-29-76 to file objec

tions to such proposed Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law.

275 Plaintiffs’ Supplemental Memorandum

of Law in Opposition to Defendants’

Motion to Dismiss the Amended Com

plaint.

287 Plaintiffs’ Motion for an Order Permit

ting the Appearance of Additional

Counsel, Patrick O. Patterson, Esq.

289 LETTER BRIEF with regards to De

fendants’ Motion to Dismiss the

Amended Complaint, by Plaintiffs.

(Apparently, Original copy was mail

ed to Judge Fisher).

301 Supplemental Memorandum in Support

of Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss.

315 Affidavit of C. B. Draper.

321 ORDER entered by Judge Fisher grant

ing motion for Patrick O. Patterson,

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030, New

York, New York 10019 leave to ap

pear as additional counsel for Plain

tiff. Certified copy to all counsel of

record. V.76,P.274

323 Plaintiffs’ SECOND SUPPLEMENTAL

MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OP

POSITION TO DEFENDANTS’ MO

TION TO DISMISS THE AMEND

ED COMPLAINT with proposed

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CON

CLUSIONS OF LAW.

NR. PROCEEDINGS

9

DATE

10-29-76

11-24-76

11-24-76

11-24-76

11-24-76

11-29-76

12-17-76

1-3-77

337 Defendants’ SECOND SUPPLEMENT

AL MEMORANDUM OF LAW in

Support of its Motion to Dismiss the

Amended Complaint.

343 NOTICE of Motion, by Plaintiffs.

344 MOTION to Join Additional Defend

ants and for Leave to Amend Com

plaint filed by Plaintiffs.

JJF 11-30-76.

355 MEMORANDUM OF LAW in Support

of Plaintiffs’ Motion to Join Addition

al Defendants and to Amend Com

plaint.

361 AFFIDAVIT of Wesley P. Bernard.

367 ORDER that Motion to Dismiss be

treated as motion for summary judg

ment under Rule 56, F.R.Civ. P. and

that the parties submit all pertinent

materials to said motion by 1-3-77,

JJF Attorneys notified. V.77,P.

368 MEMORANDUM in Support of Gulf’s

Limited Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Mo

tion to Join Additional Defendants

and for Leave to Amend Complaint.

JJF 12-17-76.

381 Plaintiffs’ MEMORANDUM in Re

sponse to Order Treating Defend

ants’ Motion to Dismiss as a Motion

for Summary Judgment. JJF 1-3-77.

NR. PROCEEDINGS

10

DATE

1-11-77

2-9-77

2-9-77

2-18-77

387 ORDER that summary judgment be

granted for the defendants as to both

the class action and any individual

claims of discrimination by the plain

tiffs. JJF s/1-11-77. Attorneys noti

fied. V.78,P.

392 NOTICE OF APPEAL to U. S. Court

of Appeals, Fifth Circuit, by Plaintiffs

from Order of Dismissal entered on

January 11, 1977. Certified copy of

Notice of Appeal mailed to Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals, New Or

leans, LA, Jerry Bloxom, U. S. Court

Reporter, Beaumont, Texas, Judge

Fisher, and all attorneys of record.

393 AFFIDAVIT of Cecil L. Cain, with

Calcasieu Insurance Agency, Inc. of

Lake Charles, LA, who has applied

for a surety bond with the WEST

ERN SURETY COMPANY.

395 BOND for Costs through Western Sure

ty Company of Sioux Falls, SD for

$250.00.

NR. PROCEEDINGS

11

In The

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

For The Eastern District Of Texas

Beaumont Division

CIVIL ACTION NO. B-76-183-CA

WESLEY P. BERNARD, ELTON HAYES, SR.,

RODNEY TIZENO, HENCE BROWN, JR.,

WILLIE WHITLEY, WILLIE JOHNSON,

individually and on behalf of all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v.

GULF OIL COMPANY and OIL, CHEMICAL

and ATOMIC WORKERS INTERNATIONAL

UNION, LOCAL UNION NO. 4-23,

Defendants.

C O M P L A I N T

I.

NATURE OF CLAIM

1. This is a proceeding for declaratory and prelimin

ary injunctive relief and for damages to redress the de

privation of rights secured to plaintiffs and members of

the class they represent by Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., and the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

12

II.

JURISDICTION

2. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §§ 1334(4), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f), 2201 and

2202, this being a suit in equity authorized and instituted

pursuant to the Civil Rights Acts of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, and 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked to secure the protection

of and to redress deprivation of rights secured by (a) 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., providing for injunctive and

other relief against discrimination in employment on the

basis of race and (b) 42 U.S.C. § 1981 providing for the

equal rights of all persons in every state and territory

within the jurisdiction of the United States.

III.

CLASS ACTION

3. Plaintiffs bring this action on their own behalf, and

pursuant to Rule 23 (b )(2 ) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure as a class action on behalf of those similarly

situated. The members of the class and/or subclasses

represented by plaintiffs are: (a) all black employees

employed by defendant Gulf Oil Company in Port Ar

thur, Texas; (b) all black employees formerly employed

by Gulf Oil Company in Port Arthur, Texas; and (c) all

black applicants for employment at Gulf Oil Company

who have been rejected for employment at said company.

The requirements of the Federal Rules are met in that:

a. The members of the class are so numerous that

joinder of all members would be impracticable.

There are, for example, more than 300 blacks em

ployed by Gulf Oil Company in Port Arthur, Texas;

13

b. There are questions of law and fact common to

the class. It is alleged herem~that defendants have

discriminated against virtually every black employed

by Gulf Oil Company in respect to the terms and

conditions of their employment;

c. The claims of the plaintiffs are typical of the

claims of the class and/or subclasses;

d. The plaintiffs will fairly and adequately protect

the interests of the classes and subclasses. TKeTm

terests of the plaintiffs are identical or similar to

those of the class members;

e. The defendants have acted and refused to act on

grounds generally applicable to the class and sub

classes, thereby making appropriate final injunctive

and declaratory relief with respect to all members of

the classes;

f. The questions of law and fact common to the

members of the class and subclasses predominate

over questions affecting only individual members; a

class action is superior to other available methods

for the fair and efficient adjudication of the con

troversy.

IV.

PLAINTIFFS

4. Plaintiff Wesley P. Bernard is a black citizen of

the United States and Port Arthur, Texas. Plaintiff Ber

nard has been employed by Gulf Oil Company since

June 16, 1954. He was hired as a laborer and is presently

a truck driver.

14

5. Plaintiff Elton Hayes, Sr., is a black citizen of the

United States and Port Arthur, Texas. Plaintiff Hayes

has been employed at Gulf Oil Company since October

2, 1946. He was hired as a laborer and is presently a

boilermaker, having worked at various “helper” positions

during his employment at Gulf Oil Company.

6. Plaintiff Hence Brown, Jr., is a black citizen of the

United States and Port Arthur, Texas. Plaintiff Brown

was hired as a laborer in 1954 and presently works as

a truck driver.

7. Plaintiff Willie Whitley is a black citizen of the

United States and Port Arthur, Texas. He was hired in

1946 as a laborer and retired in October, 1975, as a

utility man, a classification slightly above a laborer

classification.

8. Plaintiff Rodney Tizeno is a black citizen of the

United States and Port Arthur, Texas. Plaintiff Tizeno

was hired originally as a laborer and is presently a crafts

man at Gulf Oil Company.

9. Plaintiff Willie Johnson is a black citizen of the

United States and Port Arthur, Texas. Plaintiff Johnson

was hired as a laborer at Gulf Oil Company.

V.

DEFENDANTS

10. Defendant Gulf Oil Company in Port Arthur,

Texas (hereinafter simply Gulf Oil) is a corporation

incorporated and/or doing business in the State of Texas.

It operates and maintains a manufacturing plant in Port

Arthur, Texas which produces a variety of oil and petro

leum products and by-products. Gulf Oil is a corporation

15

engaged in interstate commerce, employing more than

fifteen persons, and is an employer within the meaning

of 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-(b).

11. Defendant Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers

International Union, Local Union No. 4-23 is recognized

as the exclusive bargaining representative of operating

and maintenance employees for the purpose of collective

bargaining with respect to rates of pay, wages, hours of

employment, and other conditions and terms of employ

ment. Local Union No. 4-23 is a labor organization

within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. § 20QQe-(d),(e).

VI.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

12. Black employees of Gulf Oil are, and have in the

past, been victims of systematic racial discrimination by

defendants Gulf Oil and Oil, Chemical and Atomic

Workers International Union, Local Union No. 4-23.

Prior and subsequent to July 2, 1965, Gulf Oil engaged

in policies, practices, customs and usages made unlawful

by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e et seq.) and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 which discrimin

ate or have the effect of discriminating against plaintiffs

and the classes they represent because of their race and

color.

13. The methods of discrimination include, but are not

limited to, intentionally engaging in the following prac

tices:

a. Hiring and Assignment: Gulf Oil unlawfully has

assigned and continues to assign a disproportionately

large number of black employees to the Company’s

16

lowest paying, least preferred, and more physically

demanding jobs;

b. White employees are given preference in initial

employment and job assignments by Gulf Oil. The

company utilizes a battery of tests which discrimin

ates or has the effect of discriminating against blacks

in initial employment with the Company. In addition,

Gulf Oil maintains a high school diploma require

ment and, on information and belief, other pre-em

ployment criteria which discriminate or have the

effect of discriminating against black applicants.

Because of discrimination in hiring and job assign

ment, a disproportionately large number of whites

have been preferentially hired by Gulf Oil for higher

paying jobs than blacks with substantially the same

or better qualifications. Black employees are now,

and have in the past, been paid less money for harder

work under less desirable working conditions than

their white counterparts;

c. The use of a pre-employment test battery is legally

deficient in one or more of the following ways: (1)

it is not professionally developed; (2) it has little or

no relationship to successful job performance; (3)

it has little or no relationship to the job sought or

applied for; (4) it exhibits a racial and cultural bias

against blacks;

d. Defendant company employs a disproportionately

small number cf blacks in permanent craft positions.

Blacks have been historically excluded from higher

paying craft positions by Gulf Oil;

e. Gulf Oil has failed and/or refused to promote

black employees and “helpers” to journeymen posi-

17

tions, irrespective of their ability to perform the job

or position sought;

f. As a result of the Company’s racial promotion

and upgrading practices, “black” lines of progression,

job classifications and departments have been arti

ficially established and developed with the result that

blacks have been and are now confined to the lower-

paying and less-preferred jobs than are their white

counterparts;

g. Black employees have been denied training, access

and exposure to craft positions and other instructions

which are necessary to an upgrade or promotion.

Blacks who perform the same or comparable work

as whites are given unequal pay and compensation;

h. On information and belief, Gulf Oil also dis-

criminatorily denies blacks their full employment

rights in that it denied blacks who work in largely

minority occupied jobs or departments, seniority

rights, opportunities, and privileges. Generally, Gulf

Oil has refused and/or failed to recognize the full

seniority rights of its black employees, adversely

affecting their discharges, training, upgrade, transfer,

and promotion rights.

g. On information and belief, Gulf Oil has dis-

criminatorily excluded blacks and has refused and/or

failed to recruit and train blacks for supervisory,

technical, professional, and clerical positions;

h. Gulf Oil discriminatorily assesses discipline and

discharge against black employees for reasons which

would not be grounds for discipline or discharge of

whites in similar positions;

18

14. Defendant Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers In

ternational Union, Local Union No. 4-23 has agreed to,

acquiesced in or otherwise condoned the unlawful em

ployment practices referred to in paragraph VI(13)

(a-h), supra.

VII.

EXHAUSTION OF REMEDIES

15. Neither the State of Texas nor the City of Port

Arthur has a law prohibiting the unlawful practices herein

alleged.

16. All jurisdictional prerequisites to this action have

been satisfied. This action is timely commenced under

both 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., and 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

VIII.

PRAYER FOR RELIEF

THEREFORE, plaintiffs and the classes represented

pray as follows:

A. That this Court formally determine, pursuant to

Rule 23(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, that

this action is maintainable on behalf of the class and/or

subclasses described in paragraph III (3), supra.

B. That this Court issue affirmative relief as follows:

a. that Gulf Oil be required to institute an active

recruitment policy;

1. That Gulf Oil be required to canvass the qualifica

tions of all its black employees with the goal to pro-

19

mote all such qualified employees and to eliminate

all present effects of past racial discrimination with

the following provisions:

a. that plaintiffs and the classes be afforded full util

ization of company seniority in bidding for or

seeking better paying and more desirable jobs;

b. restructuring lines of progression, revision of ap

plicable residency requirements, advanced level

entry, and job skipping at Gulf Oil Company;

c. training and other assistance as necessary to en

able the plaintiffs and the class to overcome the

effects of past discrimination;

d. an award of back pay to each plaintiff and class

member for any financial losses suffered by plain

tiffs and the classes and which are attributable to

acts of racial discrimination complained of herein;

e. rate protection sufficient to assure that black em

ployees will not be economically discouraged, pre

vented or penalized in their efforts to attain their

rightful place in Gulf Oil’s employment structure;

f. prospective red circling to alleviate the residual

effects of any racial discrimination not corrected

or completely removed by this action;

g. Gulf Oil be required to suspend the use of any and

all tests or other criteria for promotion or for

initial employment until said tests or criteria are

validated in accordance with the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission Guidelines on

Testing;

20

h. that the defendant Union, Local 4-23, be required

to file all grievances of its black members of

Gulf Oil;

i. enter a declaratory judgment that the acts and

practices complained of are in violation of the

laws of the United States;

j. that plaintiffs and the classes they represent be

awarded their complete costs of this action, in

cluding a reasonable attorneys’ fees pursuant to

42 U.S.C. § 20Q0e-5(k).

k. Grant Plaintiffs and the classes they represent

such other and further relief as may be necessary

and proper.

Respectfully submitted,

STELLA M. MORRISON

Stella M. Morrison

World Trade Building - Suite 516

440 Austin Avenue

Port Arthur, Texas 77640

CHARLES E. COTTON

348 Baronne Street - Suite 500

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

JACK GREENBERG

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

ULYSSES GENE THIBODEAUX

10 Columbus Circle - Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

21

MOTION BY GULF TO LIMIT

COMMUNICATIONS WITH ANY

POTENTIAL OR ACTUAL CLASS MEMBER

[Caption Omitted in Printing]

Filed May 27, 1976

Comes now Gulf Oil Corporation (Gulf), a Defendant

in the above-captioned suit, and moves this Court for

an order limiting communications by parties to this suit

and their counsel with any actual or potential class

members.

In support of this Motion, Gulf has attached a memo

randum brief.

JOSEPH H. SPERRY

WM. G. DUCK

P. O. Box 3725

Houston, Texas 77001

Telephone: (713) 226-1617

By J. H. SPERRY

Attorneys for Defendant

GULF OIL CORPORATION

[Certificate of Service Omitted in Printing]

22

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF GULF'S

MOTION TO LIMIT COMMUNICATIONS

WITH ANY POTENTIAL OR ACTUAL

CLASS MEMBER

[Caption Omitted in Printing]

Filed May 28, 1976

This is a class action suit brought by six individual

employees of Gulf’s Port Arthur Refinery alleging they

have been victims of discrimination in violation of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e,

et seq., and of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981. The suit was filed on May 18, 1976, and Gulf

was served with a summons on May 24, 1976.

The issues which have been raised in this lawsuit have

been the subject of settlement negotiations between Gulf,

the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

and the Office for Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department

of the Interior. The negotiations between Gulf and these

federal agencies to conciliate the issues which now have

been raised in this action have taken place over a period

of several years and have resulted in the signing by Gulf

of a Conciliation Agreement. This agreement, which was

entered into by Gulf and the Federal Agencies on April

14, 1976, provided for an award of over $900,000 to 614

present and former black employees and 29 female em

ployees at Gulf’s Port Arthur Refinery. A copy of this

Conciliation Agreement is attached hereto as Exhibit A.

As soon as the Conciliation Agreement was finalized,

Gulf pursuant to the terms of the Conciliation Agree

ment mailed a letter and release, the form of which was

23

approved by the Federal Agencies, notifying all employees

covered by the Conciliation Agreement that they were

entitled to an award of back pay and that upon execution

of the receipt and general release the employees would

receive the back pay award. Between the time the Con

ciliation Agreement was executed by Gulf, and the date

the summons was served upon Gulf in this action, ap

proximately 452 employees out of a total of 643 em

ployees entitled to a back pay award had executed the

receipt and general release and had received their back

pay checks.

So as to comply with the letter and spirit of Rule 23

(e), F.R.C.P. and the Canons of Ethics of the Bar Asso

ciation, Gulf immediately upon service of the summons

suspended all further mailings to actual or potential class

members and informed all actual or potential class mem

bers who called Gulf that no further communications

concerning the Conciliation Agreement or the issues

raised in the lawsuit could be discussed with them until

the Court so orders. Attached hereto as Exhibit B is a

copy of the statement which was read to all potential and

actual class members who called Gulf inquiring about

these matters.

However, on Saturday, May 22, 1976, four days after

the Complaint was filed in this action, an attorney for

the Plaintiffs,_Mr. Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux, appeared

before approximately 75 actual or potential class members

ariTmeetmgTnT discussed with” themthe

jssues involved in the case and recom mer^3~loTiose

employees that the^'gp'T iur-stffl^e r^eipT^nd~^nerS

le^Se~Much~had been mailed’ro t ^

Conciliation Agreement!nE~TaH7TrTimreported~To'TjuIP

24

that Mr. Thibodeaux advised this group that they should

mail back to Gulf the chec^lhe5riTad feceived slhce~Ee*

could recover at least double the amount which was paid

to them under the Conciliation Agreement Tiy prosecuHng~

the present lawsuit. - - ..

Gulf believes that this action by the Plaintiffs’ attorney

is indeed a serious breach of the ethical and legal stand

ards which are imposed upon attorneys under the Canons

of Ethics and the law. In order to prevent further com

munications of this type by all parties and their counsel

to this suit, Gulf has moved the Court for an order to

limit communications with any potential or actual class

member to this lawsuit. The order which Gulf proposes

be entered pursuant to its Motion is copies verbatim from

“Sample Pretrial Order No. 15—Prevention of Potential

Abuse of Class Actions” contained in the Manual for

Complex and Multidistrict Litigation, p. 197. This order

is also identical to many local rules of the United States

District Courts which have adopted “Suggested Local

Rule No. 7—Prevention of Potential Abuse of Class Ac

tions” contained in the Manual for Complex and Multi

district Litigation on p. 196.1 It should be noted that the

Manual for Complex and Multidistrict Litigation suggests

that such an order be promptly entered in actual and

potential class action cases unless there is a parallel local

rule. 1

1. See Local Rules of the U.S. District Court for the Southern

District of Texas, Rule 6; and the General Rules of the U.S. District

Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, Rule 2.12e.

25

By entering the suggested order, this Court will pre

serve the status quo of the case until Judge Fisher returns

and can assume control and administration of the case.

In the absence of such an order, Gulf feels that the

unusual circumstances involved in this case, combined

with the statements which Plaintiffs’ counsel has already

made to actual and potential class members, could seri

ously prejudice Gulf In its defense of this case and the

conciliation efforts which have been conducted by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the

Office for Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the

Interior.

CONCLUSION

In accordance with the above stated authorities, Gulf

urges the Court to grant its Motion to Limit Communica

tions with any Potential or Actual Class Member.

[Signatures Omitted in Printing]

26

Exhibit A

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION

Houston District Office

2320 La Branch, Room 1101

HOUSTON, TEXAS 77004

AREA CODE 713

226-5611

CONCILIATION AGREEMENT

In the Matter of:

U.S. EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION

and

Gulf Oil Company—U.S. Charge No. AU68-9-154E

Port Arthur, Texas

Respondent

and

Office for Equal Opportunity

U.S. Department of the Interior

Compliance Agency

* * *

A charge having been filed under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, by a Commissioner of

the U. S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

against the Respondent, the charge having been investi

gated and reasonable cause having been found, the parties

do resolve and conciliate this matter as follows:

[Table of Contents Omitted in Printing]

27

A. GENERAL PROVISIONS

1. It is understood that this Agreement does not con

stitute an admission by the Respondent of any

violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as amended.

2. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission hereby waives and releases its cause of

action against the Respondent under the instant

charge and covenants not to sue the Respondent

independently or on behalf of any individual includ

ing, but not necessarily limited to, persons listed

on Attachments “A” and “B” hereto with respect

to any matter alleged thereunder, subject to per

formance by the Respondent of the promises and

representations contained herein.

3. The Respondent understands that the Commission,

on its own motion, may review compliance with

this Agreement. As a part of such review, the Com

mission may require written reports concerning

compliance, may inspect the premises, examine wit

nesses, and examine and copy documents pertinent

to such review. The Commission agrees that the

Respondent reserves ail rights and protection af

forded by the Freedom of Information Act, as

amended.

4. The Respondent reaffirms that all of its hiring, pro

motion practices, classification, assignments, layoffs

and all other terms and conditions of employment

shall be maintained and conducted in a manner

which does not discriminate on the basis of race,

color, religion, sex or national origin in violation

28

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended.

5. The Respondent agrees that it will not knowingly

practice nor permit its supervisory or other per

sonnel to practice discrimination or retaliation of

any kind against any person because of his or her

opposition to any practice declared unlawful under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, or because of the filing of a charge, or

giving of testimony or assistance, or participation in

any manner in any investigation, proceeding, or

hearing under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as amended.

6. Recognizing the exception with respect to sex or

regards toilets, showers and the like, the Respond

ent reaffirms that all facilities on the premises or

furnished its employees, including recreational op

portunities and all other conveniences and services,

are available for the use and enjoyment of any em

ployee without regard to race, color, religion, sex

or national origin; that there is no discrimination

against any employee on said grounds with respect

to the use of facilities; and that the notices required

to be posted by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as amended, are posted.

B. SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT—BACK PAY

1. Appertaining to back pay, the Affected Class is

hereby defined as all Negroes employed by the Re

spondent on July 2, 1965, whose seniority date an-

tecedes January 1, 1957, and all hourly rated

females employed by the Respondent in its Package

and Grease Department on July 2, 1965.

29

2. The Commission agrees that a thorough search has

been made to identify all individuals potentially

entitled to backpay under this Agreement, that the

Respondent’s personnel records since the effective

date of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

have been exhaustively analyzed and that, through

examination of documents submitted by the Re

spondent, no persons potentially entitled other than

those listed on Attachments “A” and “B” hereto

could be found.

3. For the sake of convenience, the Affected Classes,

as shown on Attachments “A” and “B”, shall be

designated and hereinafter referred to as Group

“A” and Group “B” respectively.

4. The Respondent agrees that all individuals identi

fied as belonging to Group “A” or Group “B” shall

immediately be awarded upon notification of ac

ceptance as described below, such back pay as is

hereinafter provided:

a. The Respondent represents that it has set aside

a sum for purposes of fulfilling all back pay obli

gations which are or might have been incurred

as a result of employment practices complained

of in the instant charge or which were treated

in the Commission’s Letters of Determination or

Reconsideration of Determination thereon, in

cluding matters found by the Commission to be

like and related.

b. The United States Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission concurs that the sum set aside

is sufficient to meet the purposes of providing

30

equitable relief to designated members of Group

“A” or Group “B” and stipulates that $35,000.00

of said amount may be reserved and held in a

special account by the Respondent for a period

of five years. The Commission agrees that, inso

far as matters encompassed by this Agreement

are raised to issue in the future, the Respondent

shall utilize its special account to dispose of con

tingent liabilities, and that any undispensed

funds remaining, after passage of the account’s

established five year life, shall be returned to the

Respondent’s general control for unrestricted use.

c. In formulating the specific relief due each indi

vidual hereunder credits will be awarded as

follows:

(1) To members of Group “A”, $5.62 for each

month of continuous service with the Re

spondent prior to January 1, 1957, and

$2.81 for each month of continuous service

thereafter until date of termination or until

January 1, 1971, whichever occurs earlier.

(2) To members of Group “B”, $5.62 for each

month of continuous service with the Re

spondent until date of termination or until

January 1, 1975, whichever occurs earlier.

d. Back pay awards previously tendered to members

of Group “A” under the Respondent’s Agreement

dated May 7, 1971, with the Office for Equal Op

portunity, United States Department of the Interior

shall be deducted from amounts hereunder due

those same individuals.

31

e. Back pay awards will be subject to standard

deductions for F.I.C.A. and Federal Income Tax

Withholding.

f. Upon accepting a back pay award, each Group

“A” or Group “B” member will be required to

execute a general release to the Respondent for

any and all claims against the Respondent as a

result of events arising from its employment

practices occurring on or before the date of re

lease, or which might arise as the result of the

future effects of past or present employment

practices.

g. Prior to tendering back pay awards, the Respond

ent agrees to notify in writing each member be

longing to Group “A” or Group “B” that he or

she has been so identified, and of the general

formula used to calculate awards and of the con

ditions of waiver or release required in accepting

back pay. Each member shall be furnished a

form on which to notify the Respondent, within

thirty days, whether such member desires to ac

cept or decline back pay consideration. A failure

on the part of any member to respond within

thirty days shall be interpreted as acceptance of

back pay. It is agreed that the form of notifica

tion to be utilized shall be reviewed and signed

by a Commission representative prior to being

implemented or disseminated.

h. In the event that a member of Group “A” or

Group “B” is deceased, notice shall be given and

payment made to his or her estate. Upon accept

ing a back pay award, the deceased member’s

32

heir or heirs shall be required to execute a gen-

erah release as is provided in subsection (f)

hereinabove.

i. In the event that a member of Group “A” or

Group “B” refuses his or her award, or cannot

be located or, if deceased, his heir or heirs can

not be located through the exercise of reasonable

effort, his or her back pay award shall be

placed in the Respondent’s special account as

provided in subsection (b) above, to be returned

to the Respendent’s general control, if unclaimed

upon expiration of the account’s life.

C. SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT—GOALS AND

TIMETABLES

1. a. For Affirmative Action purposes, the Affected

Class is hereby defined as all hourly rated fe

males presently employed in the Respondent’s

Package and Grease Department whose seniority

date antecedes April 5, 1974 and all members of

back pay Group “A” who are presently employed

in the classification of Operator Helper No. 1,

Boiler Washer “X”, Brander “X”, Operator

Helper No. 2, Utility Helper or Laborer.

b. For the sake of convenience, the Affected Class

for Affirmative Action purposes shall be desig

nated and hereinafter referred to as Group “C”.

2. The Respondent, firm in its commitment to act in

good faith and compliance with Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, has con

ducted a thorough analysis of its work force and has,

33

as of January 1, 1976, identified those classifica

tions wherein Negroes, Spanish Surnamed Ameri

cans and/or females are statistically underrepre

sented. Said classifications, designated and herein

after referred to as “Target Classifications,” are as

follows:

a. Analytical Tester

b. Area Storehouseman

c. Boiler Fireman

d. Boilermaker

e. Bricklayer

f. Carpenter

g- Clerical

h. Compounder No. 1

i. Craft Apprentice and Trainee

j- Dockman

k. Electrician

1. Garage Mechanic

m. Gas Dispatcher

n. Greasemaker No. 1

0 . Greasemaker No. 2

P- Instrument Man

q- Insulator

r. Lineman

s. Machinist

t. Operator No. 1

u. Operator No. 2

V. Assistant Operator

w. Painter

X. Pipefitter

y- Power Plant Engineer No. 1

z. Power Plant Engineer No. 2

34

aa. Power Plant Operator

bb. Pumper No. 1

cc. Pumper No. 2

dd. Railroad Craft Group

ee. Receiving Room Man

ff. Treater No. 1

gg. Treater No. 2

hh. Tinner

ii. Treater Helper No. 1

jj. Troubleman

kk. Water Pumper No. 2

11. Water Tender

mm. Water Treater No. 1

nn. Water Treating Plant Operator

oo. Welder

pp. EEO-l Technician Category

qq. EEO-1 Professional Category

rr. EEO-1 Official and Manager Category

3. With respect to the Respondent implementing its

Affirmative Action Program as provided herein, the

Commission stipulates that:

a. Ratios shall not be fixed but shall serve solely as

general measures of the Respondent’s satisfactory

progress hereunder.

b. Although it is assumed and expected that minority

and female placement within the above listed

“Target Classifications” will be evenly distrib

uted, the Respondent will not be faulted if it fails

to meet its goals and timetables in one or more

classifications as long as its overall progress is

satisfactory.

35

c. The Respondent shall not be restricted to selection

of Group “C” Affected Class members in meet

ing its goals and timetables, but may, at its dis

cretion, select other qualified Negro, Spanish Sur-

named American or female employees, or recruit

from outside its workforce, thereby equally satis

fying Affirmative Action commitments.

d. Failure by the Respondent to meet its goals and

timetables hereunder shall not serve as justifica

tion to increase or renegotiate backpay as pro

vided in Section B.

4. Considering the above, the Respondent agrees to

establish a goal to fill one of every five vacancies in

“Target Classifications” other than its EEO-1 Offi

cial and Manager Category, wherein the ratio shall

be one of every seven, with a Negro, a Spanish Sur-

named American or a female until such time as

their respective representation jointly within said

classifications equals or exceeds their joint repre

sentation throughout the Respondent’s workforce.

5. On occasions when a vacancy is to be filled with a

Group “C” member, the Respondent will fill it by

selecting the bidder having greatest seniority, sub

ject to relative skills, abilities, and qualifications,

and provided that the Respondent’s initial entry

requirements are met.

6. Group “C” members upgrading hereunder shall be

classified as provisional and shall be on trial for a

period not to exceed 120 days. They will receive

the same training and orientation given other em

ployees, and, if qualifying according to normal

36

company competency standards, the provisional

title shall be dropped. The Respondent may make

its determination prior to expiration of the full 120

day period. An employee determined by the Re

spondent not to be qualified for the job for which

he or she has been on trial shall be returned to his

or her former classification without loss of seniority.

Determination that any employee has qualified here

under shall not bind the Respondent to accept the

employee for any other classification, but such em

ployee shall be judged at each level in the same

manner as other employees. An upgraded Group

“C” member may disqualify himself or herself dur

ing the 120 day trial period and, in that event, shall

be returned to his or her former classification with

uninterrupted seniority.

7. Each upgraded Group “C” member shall have his

or her seniority date determined by applicable col

lective bargaining agreement provisions, with the

exception that in the event of a reduction in force

or layoff, any Group “C” member who has up

graded to a Clerical classification or to a Classifi

cation represented by the United Transportation

Union; the Bricklayers, Masons and Plasters Inter

national Union Local No. 13; the International

Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers,

Port Arthur Lodge No. 823; or the International

Brother of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO, Local

Union No. 390 shall have humpback rights into the

Operator Helper No. 2 pool or into the classifica

tion of Utility Helper or Laborer, according to his

or her former seniority at the time upgraded. The

37

Respondent shall retain the right to select into

which of the above three classifications the affected

Group “C” member shall be placed. Each Group

“C” member so displaced shall continue to hold

rights to recall into his or her craft position from

which displaced, as though he or she had not

bumped back.

8. The Respondent agrees that the rate of pay for each

upgraded Group “C” member shall be the higher

of his or her permanent rate at the time upgraded

or the appropriate new rate. This provision shall

not apply in the event that a Group “C” member

bids into a classification in which the top rate for

the new line of progression is less than his or her

former rate.

9. Each member of Group “C” who participates in this

special program shall receive one bona fide oppor

tunity to upgrade. Such opportunity shall be satis

fied, and the employee’s rights hereunder shall ter

minate, when the employee either (a) takes a job

and qualifies therefor, (b) takes a job and fails to

qualify or requests to return to his or her former

job classification or (c) declines an offer to up

grade. Group “C” members who resign from em

ployment with the Respondent shall have no further

rights hereunder.

10. An upgraded employee’s failure to qualify during

the established trial period, or a declination of a

job offer made to an employee by the Respondent,

shall not satisfy that particular exercise of the Re

spondent’s obligation under established ratios to

38

ward goals and timetables, and such opportunity

shall be extended to another individual.

11. Notwithstanding any of the foregoing, the Respond

ent shall not be required to place or retain any

person in a job who does not have the skill, ability

and qualifications to perform said job.

12. The United States Equal Employment Opportunity.

Commission and the Respondent remain in dis

agreement as to the Respondent’s continued use of

test battery results for employment and promotion

purposes. However, in order to provide a means

to resolve those matters held in dispute, the Com

mission agrees that the Respondent reserves the

right to utilize test scores along with other job

related criteria in assessing individual qualifications.

In consideration therefore, the Respondent repre

sents that it shall not rely upon test scores as

justification for its failure to meet goals and time

tables in any job classification.

D. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

The Respondent agrees to refine and strengthen on a

continuing basis positive and objective nondiscriminatory

employment standards, procedures and practices and re

presents that in its business operations it exerts continuing

effort to uniformly apply such standards, practices, and

procedures in a manner which will assure equal employ

ment opportunities in all aspects of its total work force

and operations without regard to race, color, religion, sex

or national origin.

39

E. COMMISSION ASSERTION AND REPORTING

REQUIREMENTS

1. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

agrees that upon fulfillment of its obligations here

under the Respondent will be in full compliance

with all provisions of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, at its Port Arthur, Texas

Refinery.

2. Six months after the date of approval of this Agree

ment and every six months thereafter for its estab

lished life of five years, the Respondent shall send

to the Commission a written report concerning all

actions encompassed by the provisions hereinabove

set forth, Such reports shall accurately, fully and

clearly describe the nature of the remedial and affir

mative action undertaken and shall be submitted to

the District Director, Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission, 2320 LaBranch, Room 1101,

Houston, Texas 77004 with a copy submitted to the

Regional Manager, Office for Equal Opportunity,

Department of the Interior, Denver Federal Center,

Building 67, Room 880, Denver, Colorado 80225.

F. SIGNATURES

I have read the foregoing Conciliation Agreement and

I accept and agree to the provisions contained herein:

4/14/76 MERLIN BREAUX

Gulf Oil Company—U.S.

Port Arthur, Texas

Respondent

40

\ I recommend approval of. this Conciliation Agreement:

4/14/7 6 JAMES R. ANDERSON

James R. Anderson

Equal Opportunity Specialist (E)

I concur in the above recommendation for approval of

this Conciliation Agreement:

4/14/76 CARL D. HANLEY

Supervisory Equal Opportunity

Specialist (E)

Approved on behalf of the Commission:

4/14/76 HERBERT C. McCLEES

Herbert C. McClees

District Director

G. CERTIFICATE OF REVIEW AND APPROVAL

1. This is to certify on behalf of the Office of Equal

Opportunity, United States Department of the In

terior, review and approval of the foregoing con

ciliation agreement by and between the U. S. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission and Gulf

Oil Company—U.S., Port Arthur, Texas.

2. It is agreed that the Respondent has complied with

all of the provisions of the letter agreement between

Edward E. Shelton, Director of Office for Equal

Opportunity, United States Department of the In

terior and L. R. Johnston, Vice President, Em

ployee Relations, Gulf Oil Company—U.S. dated

41

May 7, 1971 and all points have been resolved to

the complete satisfaction of the Office for Equal

Opportunity, United States Department of the In

terior with the single exception of a portion of para

graph 2e. “Free Bidding—Non-Related Jobs” in

said agreement.

With regard to such paragraph, vacancies in the

following jobs will be posted for bid to present em

ployees in Group “B”:

Checker Wax Packaging House—

Bathhouse Attendant Maintenance Division

3. Should a bidding employee in Group “B” be senior

to the employee who would receive the job through

normal promotional procedures, such employee

should be awarded the job. In addition, should her

present rate be greater than the posted job in ques

tion, she should retain her present rate and also

should have the option of returning to her former

position within a thirty-day period. Other members

of the “affected class” shall not have such bidding

rights.

4. The Office for Equal Opportunity, Department of

the Interior agrees that upon fulfillment of its

obligations hereunder the Respondent will be in

full compliance with all provisions of Executive

Order 11246, as amended, at its Port Arthur, Texas

Refinery.

Fire Assistant

Truck Driver

Checker

Pump House 78

(Lubricating)

Drum Filling and Loading

(Package and Grease)

Maintenance Division

Maintenance Division

42

5. The Respondent recognizes that it has a continuing

obligation for Affirmative Action under Executive

Order 11246, as amended, and the implementing

regulations of the Department of Labor.

4/14/76 GERALD C. WILLIAMS

Gerald C. Williams

Western Regional Manager

Reviewed:

4/14/76 JAMES R. ANDERSON

James R. Anderson

Equal Opportunity Specialist (E)

Approved on behalf of the United States Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission:

4/14/76 LORENZO D. COLE

Lorenzo D. Cole

Deputy Director

EXHIBIT A— List of Employees (Omitted)

EXHIBIT B—List of Employees (Omitted)

43

EXHIBIT B

May 25, 1976

I am required to make the following statement by

Gulfs Law Department. Since 6 individuals have filed

a class action suit against Gulf Oil Corporation and the

Union alleging discrimination exists at this plant and since

you are a potential plaintiff in that suit, Gulf must sus

pend—pending the court’s order—all further mailing of

checks and all further contacts with you concerning the

payment of money under the EEOC agreement. We re

gret this situation deeply; but due to the suit, we cannot

proceed further until the court so orders.

Wm. G. DUCK

Wm. G. Duck

WGD/am

44

ORDER

[Caption Omitted in printing]

Filed May 28, 1976

Having considered the Motion by the Defendant, Gulf

Oil Corporation, to limit communications with any po

tential or actual class member;

IT IS ORDERED that, in this action, all parties hereto

and their counsel are forbidden directly or indirectly,

orally or in writing, to communicate concerning such ac

tion with any potential or actual class member not a

formal party to the action. The communications for

bidden by this order include, but are not limited to. (a)

solicitation directly or indirectly of legal representation

of potential and actual class members who are not formal

parties to the class action; (b) solicitation of fees and

expenses,and agreements to pay fees and expenses from

potential and actual class members who are not formal

parties to the class action; (c) solicitation by formal

parties to the class action of requests by class members

to QPt out in class actions under subparagraph (b )(3 )

of Rule 23, F.R.Civ.P.; and (d) communications from "

counsel or a party which may tend to misrepresent the

status, purposes and effects of the class action, and of any

impressions tending, without cause, to reflect adversely on

any party, any counsel., the Court, or any administration

of justice/The obligations and prohibitions of this order

are not exclusive. All other ethical, legal and equitable

obligations are unaffected by this order.

45

This order shall be effective until Judge Fisher returns

and can hear the matter upon formal motion.

Counsel for defendant, Gulf Oil Corporation, shall

present a motion on this matter to Judge Fisher as soon

as possible upon Judge Fisher’s return.

Date: May 28, 1976

/ s / WILLIAM M. STEGER

United States District Judge

46

MOTION TO MODIFY ORDER

[Caption Omitted in Printing]

Filed June 8, 1976

Comes now Gulf Oil Corporation (Gulf), a Defendant

in the above-styled case, and it moves this Court for an

order modifying Judge Steger’s Order dated May 28,

1976, and filed of record in this case on the same date,

to allow Gulf to comply with the terms of the Concilia

tion Agreement dated April 14, 1976, and signed by Gulf,

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the

Office for Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the

Interior, by resuming under the Court’s supervision the

payment of back pay awards to employees covered by the

Conciliation Agreement and obtaining from those em

ployees receipts and releases all as provided for by the

terms of the Conciliation Agreement. In support of this

Motion, Gulf has attached a Memorandum of Points and

Authorities.

[Signatures Omitted in Printing]

[Certificate of Service Omitted]

47

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF GULF OIL

CORPORATION’S MOTION TO MODIFY ORDER

[Caption Omitted in Printing]

Filed June 8, 1976

This is a class action suit brought by six individual

employees of Gulf’s Port Arthur Refinery alleging that

they have been victims of discrimination in violation of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2Q00e, et seq. and of the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. § 1981. The suit was filed on May 18, 1976,

and Gulf was served with a summons on May 24, 1976.

Four days after the suit was filed and prior to the time

Gulf was served with the summons in this case, attorneys

for the Plaintiffs appeared at a meeting of approximately

75 actual or potential class members in Port Arthur and

discussed with them the issues involved in the case and

recommended to those employees that they support the

present suit. In addition, it was reported to Gulf that

Mr. Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux, an attorney for the Plain-

tiffsTrecommm^ employees that they do^nof

sign thereceipt lm d " re le a i^ mailed to

"the emp[oye^~~as~~a~resiJt ^ ^ Conciliation Agreement

entered into by Gulf, the U.S. Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission (EEOC jU m ffThU U f^

'Opportunity. U.S. Department,.of the Intenor~(OEO)7

In fact, it is reported that Mr. Thibodeaux stated that even

n TEiempIovee had signed the receipt and release, he

jshould now return the check which had been mailed''To"

the employee bv Gulf. I

48

As a result of this activity by the Plaintiffs’ attorney,

Gulf on May 28, 1976, filed a Motion to Limit Com

munications with any Potential or Actual Class Member

and brought the Motion on for hearing before The Hon

orable William M. Steger. Judge Steger agreed to hear

the matter in the absence of The Honorable Joe J. Fisher

so that the status quo of the case could be preserved until

Judge Fisher returned. After hearing argument of counsel

for both the Plaintiffs and Defendant Gulf, Judge Steger

entered an order which was made applicable to all parties

and forbid all parties and their attorneys from communi

cating with actual or potential class members who were

not formal parties to the action. In addition, Judge Steger

ordered that the Defendant Gulf present a motion on this

matter to Judge Fisher as soon as possible upon Judge

Fisher’s return. In order to comply with Judge Steger’s

order, Gulf has filed this Motion to Modify so that the

matter may be heard by Judge Fisher.

The purpose of the Motion to Modify is to allow Gulf,

the EEOC, and the OEO to proceed under the terms of

a Conciliation Agreement dated April 14, 1976 (attached

hereto as Exhibit A ). The Conciliation Agreement which

has been negotiated between Gulf and the Federal agencies

over a period of eight years was an effort by Gulf to

settle the very issues which now have been raised in this

eleventh hour lawsuit. The Conciliation Agreement pro

vided for an award of over $900,000 to 616 Negro em

ployees and approximately 29 female employees at Gulf’s

Port Arthur Refinery.

As soon as the Conciliation Agreement was finalized,

Gulf pursuant to the terms of the Agreement mailed a

letter and release, the form of which was approved by

49

the Federal agencies, notifying all employees covered by

the Agreement that they were entitled to an award of

back pay and that upon execution of the receipt and

release the employees would receive the back pay award.

Between the time the Conciliation Agreement was exe

cuted by Gulf and the date the summons was served upon

Gulf in this action, approximately 452 employees out of

a total of 643 employees entitled to a back pay award

under the Agreement had executed the receipt and re

lease and had received their back pay checks.

So as to comply with the letter and spirit of Rule 23(a),

F.R.C.P. and the Canons of Ethics of the Bar Association,

Gulf immediately upon service of the summons suspended

all further mailings to actual or potential class members

and informed all actual or potential class members who

called Gulf that no further communications concerning

the Conciliation Agreement or the issues raised in the

lawsuit could be discussed with them until the Court

so orders. Attached hereto as Exhibit B is a copy of a

statement which was read to all potential and actual

class members who called Gulf inquiring about these

matters. In accordance with Judge Steger’s Order, Gulf

has continued to suspend the payment of back pay awards

and the acceptance of receipts and releases from em

ployees who are actual or potential class members.

So that Gulf may fulfill the terms of the Conciliation

Agreement, it has moved this Court for an order to

modify Judge Steger’s previous Order so that it may

proceed to make the back pay awards pursuant to the

terms of the Conciliation Agreement. It is felt that the

rights of all parties will be fully protected if the Court

exercises its judicial control over the procedures whereby

50

potential or actual class members not formal parties to

this suit are contacted with regard to the terms of the

Conciliation Agreement. In that regard, Gulf proposes

that the Court order that the Clerk mail a letter to all

employees of Gulf at its Port Arthur Refinery who are

covered by the Conciliation Agreement and who have not

signed receipts and releases for back awards informing

them that they have 45 days from the date of receipt of

the letter to accept the offer of settlement as contained

in the Conciliation Agreement and if such offer is not

accepted within that time period, the offer will expire

until further notice of the Court. Since the affected em

ployees already have received notices informing them of

the terms of the Conciliation Agreement and enclosing

the receipt and release the Court’s order setting a time

limit for acceptance of the offer would now be appropriate.

During the 45 day time period in which the actual or

potential class members are deciding whether or not to

accept the offer under the Conciliation Agreement the

parties to this lawsuit and their counsel should be for

bidden to contact those individuals so that they might

make their own independent decision concerning the

acceptance of the back pay award.

The two Federal agencies who have been involved with

this matter for over eight years and who have protected

the rights of the individual employees support Gulf’s

position that the terms of the Conciliation Agreement

should be carried out by allowing Gulf to proceed with

the payment of back pay awards. Mr. Herbert C. Mc-

Clees, who is the District Director of the EEOC in Hous

ton and whose office was involved with the negotiation

of the Conciliation Agreement, states in his affidavit that

51

he believes the issues and relief sought by the Plaintiffs

in this case are almost identical to the issues which were

resolved under the terms of the Conciliation Agreement.

In addition, he states that he feels that the Conciliation

Agreement is a “fair, equitable, thorough and compre

hensive solution to the charges that Gulf has discrimin

ated at its Port Arthur Refinery in violation of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964” (see page 4 of Affidavit