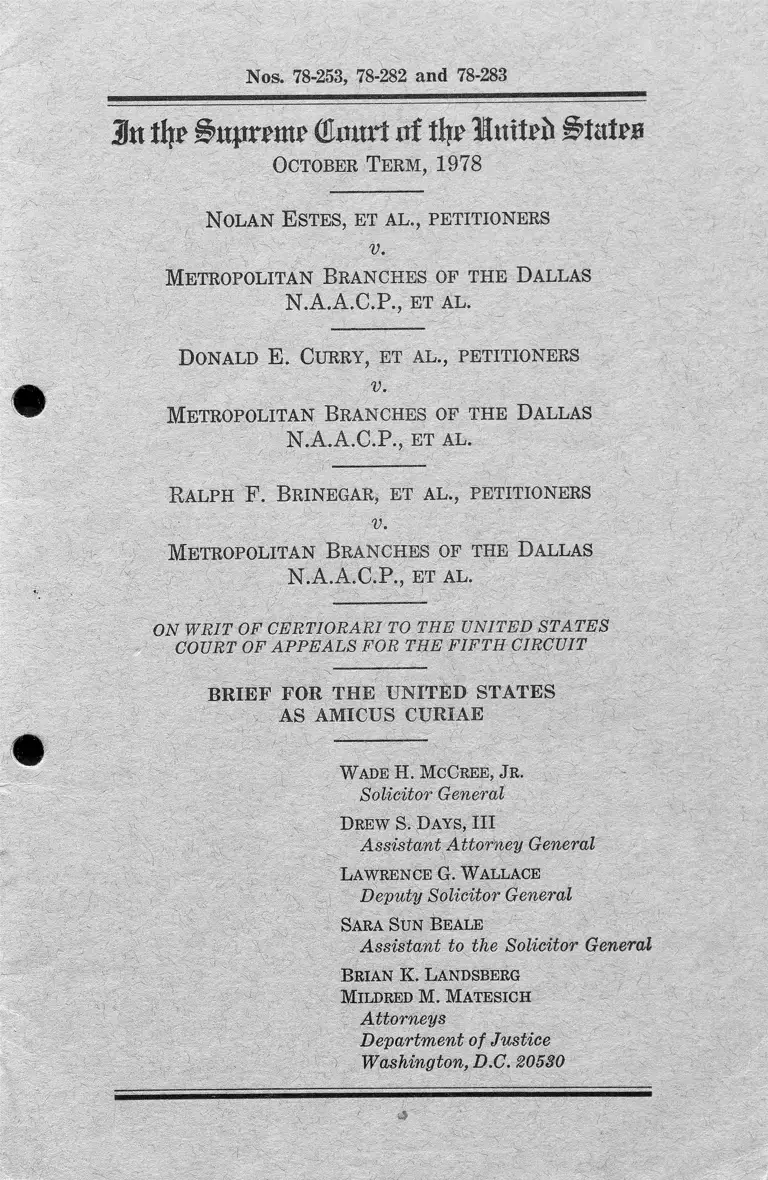

Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief Amicus Curiae, 1979. 3a8dcc1d-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/621e39ca-cfa0-4a67-9023-a777b175e92d/estes-v-dallas-naacp-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N os. 78-253, 78-282 and 78-283

3tt % ( ta r t of Iff? Itttf States

October T erm , 1978

N olan E stes, et a l ., petitioners

v.

Metropolitan Branches of th e Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

D onald E. Curry, et a l ., petitioners

v.

M etropolitan Branches of th e D allas

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

R alph F. Brinegar , et a l ., petitioners

v.

Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Wade H. McCree, Jr.

Solicitor General

Drew S. Days, III

Assistant Attorney General

Lawrence G. Wallace

Deputy Solicitor General

Sara Sun Beale

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Brian K. Landsberg

Mildred M. Matesich

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

a

I N D E X

Questions presented...............

Interest of the United States

Statement ................................

Page

2

2

3

A. The previous desegregation suits against

the D IS D ...................................................

B. The institution of the present suit and

the district court’s first order ................

C. The first appeal.........................................

D. The proceedings on remand in the dis

trict court .................................................

1. The plans submitted to the district

court.....................................................

2. The district court’s desegregation

order ........................ ..........................

E. The second appeal

Summary of argument

Argument ........................................................

I. A systemwide remedy is appropriate be

cause the Board has not fulfilled its con

tinuing obligation to eliminate the ves

tiges of the former dual school system

that persist throughout the district.....

A. Vestiges of the DISD’s dual school

system remain throughout the dis

trict ...................................................

4

5

12

14

14

17

22

24

28

28

28

B. The DISD was under a continuing

obligation to eliminate these ves

tiges .................................. ............... . 32

II

Argument— Continued Page.

II. The court of appeals properly remanded

the case for consideration of the feasi

bility of desegregating the remaining

one-race schools ....................................... 39

A. The East Oak Cliff Subdistrict--—. 43

B. Grades 9-12, K-3 outside East Oak

Cliff ..............-.................................... 46

C. The use of student transportation.. 48

Conclusion ..................— ................................. 51

CITATIONS

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 ................. -........................................... 37

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 1 9 ----------- ------— 2

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268 .......... - 4

Boson v. Rippy, 275 F.2d 850 .................... 4

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 .........—-........ 4-5

Britton v. Folsom, 348 F.2d 1 5 8 ................ 5

Britton v. Folsom, 350 F.2d 1022 ............ 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (Brown I) ...... ..................... 2, 4, 24, 28, 37

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S.

294 (Brown II) .... ------------—-..........—2, 44, 49

Brown v. Rippy, 233 F.2d 796, cert, de

nied, 352 U.S. 878 .................................. 4

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,

No. 78-610 (July 2, 1979) ...........3, 32, 33, 36,

42, 46, 50

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ...................... 2

Cases— Continued Page

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners,

402 U.S. 33 ........................................... 26, 39, 42

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

433 U.S. 406 (Dayton 1) ..........3, 33, 39, 40, 44

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

No. 78-627 (July 2, 1979) (Dayton

II) ................................................3 ,31,33,34 ,35

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S.

430 .........................................2,10,12, 35, 36, 39

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S.

189 ................................. 2

McDaniel v. Bam'esi, 402 U.S. 3 9 ............... 33

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (Milli-

ken I) ....... 3

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (Milli

ken II) ..................................................... 3

Pasadena City Board of Education v.

Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 ..... .................. 3, 37

Rippy v. Borders, 250 F.2d 690 ................ 4

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160... ........ 3

School Board of City of Richmond v. State

Board of Education, 412 U.S. 92 ......... 2

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 419 F.2d 1211 ..........10, 11, 31

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 ...............2, 31, 36, 37,

39, 41, 42, 49

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 ........................................... 37

United States v. Scotland Neck City

Board of Education, 407 U.S. 484 ....... 50

University of California Regents v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 .............................................

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 .........

37

34

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 ........................................... 2, 34, 35

Constitutions and statutes:

United States Constitution, Fourteenth

Amendment, Equal Protection Clause.... 34

Texas Constitution, Article 7, § 7 ............ 28

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 1971

et seq.:

Title IV, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6............. 2

Title VI, 42 U.S.C. 2000d ................ 2

Title IX, 42 U.S.C. 2000h-2 .............. 2

Equal Educational Opportunities Act of

1974, 20 U.S.C. 1701 et seq. .................. 2, 49

Section 204, 20 U.S.C. 1703 .............. 49

Section 205, 20 U.S.C. 1704 .............. 49

IV

Cases— Continued Page

f t

In thr Bnpmm ©Hurt of % Hotted States

October T erm , 1978

No. 78-253

N olan E stes, et a l ., petitioners

v.

Metropolitan Branches of th e Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

No. 78-282

D onald E. Curry, et a l ., petitioners

v.

M etropolitan Branches of th e Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., et a l .

No. 78-283

R alph F. Brinegar , et a l ., petitioners

v.

M etropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

(1)

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether systemwide relief was warranted to

eliminate the vestiges of Dallas’ dual school system.

2. Whether the court of appeals erred in remand

ing the case for additional findings regarding the

feasibility of reducing or eliminating the one-race

schools not affected by the district court’s remedial

order.

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

The United States has substantial enforcement re

sponsibility with respect to school desegregation under

Titles IV, VI, and IX of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6, 2000d and 2000b-2, and

under the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of

1974, 20 U.S.C. 1701 et seq. The Court’s resolution

of the issues presented in this case will affect that

enforcement responsibility. The United States has

participated either as a party or as amicus curiae

in this Court’s previous school desegregation cases,

including Brown v . Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955); Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958); Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968); Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969); Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1 (1971); Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407

U.S. 451 (1972); School Board of City of Richmond

v. State Board of Education, 412 U.S. 92 (1973);

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973);

3

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974); Runyon v.

McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976); Pasadena City Board

of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976);

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977); Dayton

Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406

(1977); Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,

No. 78-610 (July 2, 1979); and Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman, No. 78-627 (July 2, 1979).

STATEMENT

The Dallas Independent School District ( “ the

DISD” or “ the Board” ) is the eighth largest urban

school district in the United States (Pet. App. 14a).1

Its boundaries (which are not coterminous with the

City of Dallas) embrace an area of about 351 square

miles, and it has an enrollment of more than 130,000

students (Pet. App. 14a; Estes Br. 7 ).2 Although

a majority of the students in the DISD were Anglos

when this suit was commenced in 1970, by the 1975-

1976 school year, when the district court conducted

hearings on relief, the student population was 41.1%

1 “Pet. App.” refers to the petition filed in No. 78-253.

2 “ Estes Br.” refers to the brief filed by the petitioners in

No. 78-253, Nolan Estes, et al. V. Metropolitan Branches of

the N.A.A.C.P., et al. We will refer to petitioners’ brief in

No. 78-282, Donald E. Curry, et al. v. Metropolitan Branches

of the Dallas N.A.A.C.P., as the “Curry Br.,” and to petition

ers’ brief in No. 78-283, Ralph F. Brinegar, et al. v. Metro

politan Branches of the Dallas N.A.A.C.P., as the “ Brinegar

Br.”

4

Anglo, 44.5% black, 13.4% Mexican-American, and

1% other races (Pet. App. 13a-14a).3

A. The previous desegregation suits against the DISD

At the time of this Court’s decision in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), Dallas

maintained a racially segregated school system re

quired by state law.

In 1955 a group of black school children and their

parents instituted litigation to desegregate the Dallas

schools, and in 1960 the Fifth Circuit ordered the

district court to require the Board to implement a

stair-step plan, under which one grade per year would

be removed from the dual educational structure and

administered in a unitary fashion.4 Boson v. Rippy,

3 The earliest enrollment figures by race that the DISD has

supplied are for the 1966-1967 school year.

In its earliest opinion, the court of appeals used the terms

“white,” “ Mexican-American,” and “black,” defining a Mexi-

can-American as a person with a Spanish surname (see 517

F.2d at 96 n .l). Since then, the parties and the courts below

have generally used the terms “Anglo,” “Mexican-American,”

and “black;” and we do the same. The DISD initially included

Mexican-American students in the same ethnic category as

Anglo students. The DISD first established a separate cate

gory for Mexican-American students in the 1968-1969 school

year, at which time Mexican-Americans made up 7.7 % of the

total DISD student body (Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interroga

tories (First Set), App. Vol. 3, filed Nov. 18, 1970).

4 The original desegregation suit went through numerous

appeals before the stair-step plan was finally adopted. See

Brown V. Rippy, 233 F.2d 796 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 352

U.S. 878 (1956) (reversing the district court’s order dis

missing the suit as premature) ; Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d

268 (5th Cir. 1957) ; Rippy V. Borders, 250 F.2d 690 (5th

Cir. 1957) ; Boson v. Rippy, 275 F.2d 850 (5th Cir. 1960)

5

285 F.2d 43. The stair-step plan obligated the DISD

to eliminate the use of racial criteria in assigning

students to its schools. The DISD was not required

to implement any other measure to remove the ves

tiges of its prior dual system by techniques such as

“pairing” or “majority-to-minority” transfers.

On June 23, 1965, the DISD board adopted a reso

lution providing for the phased desegregation of

elementary, junior high, and high schools, and for

the establishment of single attendance districts for

each school (Deft. Ex. 1 (1971)). The superintend

ent was vested with discretion to carry out the reso

lution by establishing the boundaries of the attend

ance districts (ibid.). The result was the institution

of a “ neighborhood school” assignment policy in the

DISD. On September 7, 1965, the DISD adopted a

resolution to expedite implementation of the stair

step plan to include all twelve grades as of September

1, 1967 (Deft. Ex. 4 (1971)). The district court

conducted no subsequent monitoring of the stair-step

plan, nor did it ever declare the DISD to have

achieved unitary status.

B. The institution of the present suit and the district

court’s first order

In 1970 a group of black and Mexican-American

students and their parents instituted the present class

(holding that the district court had erred in failing to require

the DISD to submit a desegregation plan). Even after the

stair-step plan had been ordered, the court of appeals found it

necessary to issue two additional orders requiring the district

court to include the twelfth grade in the plan. Britton v.

Folsom, 348 F.2d 158 (5th Cir. 1965), and Britton V. Folsom,

350 F.2d 1022 (5th Cir. 1965).

6

action in the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas seeking to eliminate the

remaining segregative effects of the prior dual sys

tem. Although the racial composition of the DISD’s

student body was approximately 59% Anglo, 33%

black, and 8 % Mexican-American when the complaint

was filed, 67 of the 187 schools in the system had a

student enrollment that was at least 90% Anglo; 40

of the schools had an enrollment that was 90% or

more black; and in 9 additional schools the combined

enrollment of black and Mexican-American students

was more than 90% (Pltf. Ex. 5 (1971)). In 1970,

91.4% of all black students in the DISD attended

schools where blacks or blacks and Mexican-Americans

made up at least 90% of the student body, and only

2.72% of the black students attended schools where

the student body was 57% or more Anglo (Pltf. Ex.

2 (1971)). Plaintiffs sought an injunction to desegre

gate the DISD meaningfully, assignment of faculty

to reflect the overall racial composition of the district,

termination of site acquisition and school construe- 0

tion that would increase or continue racial segrega

tion in the district, and adoption of policies to lower

the dropout rate among Mexican-American students.

The Board contended that no further court-ordered

desegregation was warranted, since the Dallas schools

were in compliance with the stair-step desegregation

plan that the court of appeals had approved in 1960.

The DISD claimed that the large number of one-race

schools remaining in the district was the result of

7

changes in residential patterns since the institution

of the stair-step plan.

On July 12, 1971, trial on the issue of liability

began. Several parents testified that their children

did not attend integrated schools, and that their chil

dren had not been assigned to the schools nearest

their homes (I Tr. 19-20, 32 (1971); II Tr. 384

(1971 )).5 6 An employee who had drawn school at

tendance zone maps for the DISD testified that there

were indeed a number of areas in the school district

where students were not assigned to elementary,

junior high, or high schools nearest their homes (I

Tr. 64-70 (1971); Pltf. Exs. 7, 8, 11, 13, 15 and 16

(1971)). He used maps prepared from 1970 census

data to illustrate the close correlation between zone

lines for the DISD schools and racial population pat

terns (I Tr. 47-50, 59-60, 62-63 (1971)).

At the conclusion of the plaintiffs’ case the DISD

moved for summary judgment on the ground that

“ housing patterns * * * are the only things which

resulted in any alleged all black school or all white

school” (II Tr. 401 (1971)). The district court de

nied the motion, finding that the plaintiffs had made

out a prima facie case (ibid.).

The DISD called two witnesses, School Superin

tendent Nolan Estes and William H. Fuller, Director

of Pupil Accounting. On direct examination, Dr.

5 The record includes five volumes of testimony from the

1971 proceedings, numbered I-V, and ten volumes of testi

mony from the 1976 proceedings, numbered I-X. We will refer

to the year as well as the volume number in citing these

transcripts.

Estes listed 19 schools that he believed had shifted

from a predominantly Anglo student enrollment to a

predominantly black student enrollment because of

changes in residential patterns occurring after 1965

(II Tr. 514-520 (1971)). The DISD introduced no

evidence on the reason for the racial imbalance in the

97 other schools in the DISD that had student enroll

ments either 90% or more Anglo, or 90% or more

black and Mexiean-American.

On cross-examination, Dr. Estes stated that there

were sixteen schools built since 1965 in which Anglos

made up more than 90% of the student body, or in

which blacks or blacks and Mexican-Americans made

up more than 90% of the student body (II Tr. 566-

578 (1971)). Dr. Estes confirmed the fact that stu

dents in the DISD did not always attend schools

nearest their homes, even where that would have

promoted integration. He acknowledged that in 1970,

Julia Frazier Elementary School, which had a 100%

black enrollment, was so overcrowded that the use of

ten portable classrooms was necessitated, while

Ascher Silberstein Elementary School, which had a

97.8% Anglo enrollment, was only half-filled— even

though Silberstein was actually closer than Frazier

to some of the families in the Frazier zone (II Tr.

618-619 (1971)). Nonetheless, the DISD had not

altered the attendance boundaries between Frazier

and Silberstein (II Tr. 619-621 (1971)). He tes

tified that capacity, distance, geographic barriers,

traffic arteries, curriculum and projected enrollment

had played a part in the DISD’s drawing of attend

9

ance zones, but that the racial composition of the

student body was not considered (II Tr. 527, 590-

591 (1971)).

On July 16, 1971, the district court issued an opin

ion 6 finding that “ elements of a dual system still

remain” in the DISD (342 F. Supp. at 947):

When it appears as it clearly does from the

evidence in this case that in the Dallas Inde

pendent School District 70 schools are 90% or

more white (Anglo), 40 schools are 90% or

more black, and 49 schools with 90% or more

minority, 91% of black students in 90%= or more

of the minority schools, 3% of the black students

attend schools in which the majority is white or

Anglo, it would be less than honest for me to say

or to hold that all vestiges of a dual system have •

been eliminated in the Dallas Independent School

District, and I find and hold that elements of a

dual system still remain.

The court rejected the Board’s contention that the

continued existence of one-race schools was the result

of changes in residential patterns, reasoning that

(ibid.) :

The School Board has asserted that some of

the all black schools have come about as a result

of changes in the neighborhood patterns but this

fails to account for many others that remain as

segregated schools.

Finally the district court rejected the Board’s claim

that it had completely fulfilled its constitutional obli-

6 The opinion, which is not reprinted in the appendices, is

reported at 342 F. Supp. 945.

10

gations once it implemented the 1965 court-ordered

stair-step plan. The district court pointed out {id. at

947-948) that the Board’s arguments ignored this

Court’s ruling in Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430, 439 (1968), that a segregated school system

must “ ‘come forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work * * * now * * * until it is clear

that state-imposed segregation has been completely

removed’ ” (emphasis the Court’s). Nor had the

Board made any attempt to comply with the court of

appeals’ ruling in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir.

1969), that faculty and staff must be desegregated.7

7 The DISD’s policy of assigning- faculty on a racial basis

persisted throughout implementation of the stair-step plan,

so that in 1971 black teachers were still assigned almost ex

clusively to black schools, and white teachers to white schools

(Answer to Interrogatory 1(d), Answers to Plaintiffs’ Inter

rogatories (First Set), filed Nov. 18, 1970). When the racial

composition of the student body in a school changed, the

faculty changed as well. For example, Holmes and Zumwalt

Junior High Schools, and Pease and Stone Elementary

Schools, which had all-white faculties in 1963-1964, opened

with all-black faculties the very next year (ibid.). Although

the record includes no statistics on the racial makeup of the

schools in question during the 1963-1964 school year, by the

1966-1967 school year each of these schools had an all-black

student body (Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories (First

Set), App. Yol. 4, filed Nov. 18, 1970).

The first indication that the DISD planned to abandon its

segregated teacher assignment practices was Dr. Estes’ testi

mony in 1971 that beginning in the 1971-1972 school year

the Singleton guidelines would be implemented (II Tr. 414

(1971)).

11

The district court ordered the DISD to submit a

desegregation plan, and after conducting further

hearings on relief, it approved a plan with the fol

lowing terms:8 (1) elementary students would remain

in their neighborhood schools but predominantly black

and Mexican-American classrooms would be grouped

with predominantly Anglo classrooms for closed cir

cuit television classes and weekly visits; (2) second

ary students would be assigned on a “ satellite” zone

basis and some secondary schools would be paired;

(3) faculty desegregation would be carried out in

accordance with the Singleton guidelines; (4) a ma-

jority-to-minority transfer program would be im

plemented for secondary students; (5) a tri-ethnic

advisory committee would be established;9 and (6)

site selection and school construction would be carried

out in a way calculated to “prevent the recurrence of

a dual school structure.” The district court subse

quently stayed the student assignment provisions for

secondary students on the grounds that the satelliting

and pairing would be disruptive and would impose

undue burdens on black students (342 F. Supp. at

953, 955-957).

8 The remedial order, which is not reprinted in the appen

dices, is reported at 342 F. Supp. at 949-954.

9 The district court also found that the plaintiffs had not

proved de jure discrimination by the DISD against Mexican-

Americans, but it concluded that Mexican-Americans are a

sufficiently separate and identifiable ethnic group in the

DISD to warrant their being taken into consideration in any

desegregation plan. Accordingly, the court appointed a tri

ethnic advisory committee that included representatives of

the Mexican-American community (ibid.).

12

C. The first appeal

The Board did not appeal the district court’s find

ing that elements of its former dual school system

remained, but the plaintiffs appealed from the dis

trict court’s remedial order.10 The court of appeals

affirmed portions of the district court’s order, but

held that neither the “ television plan” for elementary

students nor the assignment plan for secondary stu

dents was adequate to eliminate the lingering vestiges

of segregation in the Dallas schools.11 Because the

“ television plan” would not have altered the racial

characteristics of the DISD’s elementary schools, the

court of appeals concluded it could not be accepted as

“ a legitimate technique for the conversion of the

DISD from a dual to a unitary educational system

* * * without a “ white” school and a “ Negro” school,

but just schools’ ” (517 F.2d at 103, quoting Green v.

County School Board, supra, 391 U.S. at 442). With

10 In two consolidated appeals the plaintiffs also sought

reversal of the district court’s refusal to enjoin various

school construction and renovation projects.

11 The court of appeals’ opinion, which is not included in

the appendices, is reported at 517 F.2d 92. The court of appeals

affirmed the district court’s decision to treat Mexican-

Americans as a separate ethnic minority for purposes of

developing a desegregation plan, and that portion of the

lower court’s rulings is not challenged here. The court of

appeals also approved the district court’s creation of a tri

ethnic advisory committee, and it declined, at that time, to

disturb the district court plan for the desegregation of the

faculty and staff of the DISD. Finally, the court of appeals

affirmed the district court’s refusal to order interdistrict

busing, as well as its refusal to exclude from its remedial

order recently developed areas of the DISD.

respect to secondary schools, the court of appeals

found that the plan’s “ extremely limited objective” of

reducing the proportionate share of a single racial

group’s enrollment at a particular school to just be

low the 90% mark “ is short of the Supreme Court’s

standard of conversion from a dual to a unitary sys

tem” (517 F.2d at 104). Finally, the court of

appeals concluded that the Board had erred in plan

ning its site selection and construction on the basis

of the attendance zones established by the district

court’s remedial orders, which it found (id. at 106) —

* * * were, for the most part, the same zones

which had been employed by the DISD over

previous academic years to implement its “neigh

borhood school concept.” As the district court

found in this case, the “neighborhood school

concept” has resulted in the perpetuation of the

vestiges of the dual school system in the DISD.

The court of appeals remanded the case to the

district court for the formulation of a new plan,

directing the district court to use and adapt “ the

techniques discussed in Swann [v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971)]” (517

F.2d at 110) to dismantle the dual structure of the

Dallas school system by the middle of the 1975-1976

school year.

This Court denied the Board’s petition for a writ

of certiorari. Estes v. Tasby, 423 U.S. 939 (1975).

D. The proceedings on remand in the district court

1. The plans submitted to the district court

On remand the district court conducted hearings in

late 1975 and early 1976. The participants in these

hearings were the parties and several groups of in

terveners, including local branches of the N.A.A.C.P.

The Curry interveners, petitioners in No. 78-282,

represented a group of residents in the northern

section of the DISD, and the Brinegar intervenors,

petitioners in No. 78-283, represented a group of

parents and students from the residentially integrated

East Dallas section of the DISD.

Six plans were considered by the district court and

described in some detail in its opinion (Pet. App.

18a-29a). The DISD and N.A.A.C.P. plaintiff-

intervenors each filed desegregation plans, and the

district court appointed its own expert, Dr. Josiah C.

Hall, to prepare an additional student assignment

plan. Plaintiffs filed alternative plans A and B, and

the sixth plan was submitted by the Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance, a community serv

ice organization that was granted amicus curiae

status for the purpose of submitting its proposal (Pet.

App. 6a).12 The student assignment provisions of

each plan were as follows.

The DISD’s proposal used pairing and clustering

to desegregate grades 4 through 12 in 72 schools in

12 The court also received plans and suggestions from

various other groups, including a proposal from a group of

students at Skyline High School (Pet. App. 7a n.4).

predominantly Anglo parts of the district; it left un

disturbed 48 one-race schools serving predominantly

minority areas and 55 schools serving naturally inte

grated areas (Pet. App. 18a-19a & n.17). Under the

DISD’s proposal about 67% of the DISD’s black

students would have attended schools where the mi

nority enrollment exceeded 90% (Deft. Ex. 11

(1976 )).13

The plaintiffs’ Plan A divided the DISD into seven

elementary subdistricts, with each school reflecting

the racial composition of its subdistrict (Pet. App.

21a). Naturally integrated subdistricts retained

their prior assignment patterns and all other schools

were paired or clustered {ibid,.). This plan left fewer

than 1 % of the black students in schools where

minority enrollment exceeded 90% (Pltf. Ex. 16

(1976)). Plaintiffs’ alternative Plan B divided the

DISD into eight subdistricts, one of which-—South

Oak Cliff— remained predominantly minority, con

tinuing its existing student assignment patterns but

with enhanced facilities and programs aimed at at

tracting students from the other seven subdistricts

(Pet. App. 22a & n.32). In the other seven subdis

tricts, pairing and clustering were used to achieve

desegregation, except where residential integration

made such tools unnecessary {ibid.). Plan B left

about 23% of the DISD’s black students in schools 18

18 All of the proposed plans also advocated the use of

“magnet” schools, which are schools with special curriculums

or programs designed to attract students from throughout the

school district.

where minority enrollment exceeded 90% (Pltf. Ex,

16 (1976)).

The plan proposed by the N.A.A.C.P. plaintiff-

intervenors sought to achieve racial balance in every

school to reflect the proportions in the DISD student

population as a whole using pairing and clustering,

except in naturally integrated areas, and eliminating

one-race schools entirely (Pet. App. 23a).

Dr. Josiah Hall, the court’s expert, presented a plan

continuing existing attendance zones in naturally

integrated areas, and pairing and clustering schools

in predominantly Anglo areas with schools in pre

dominantly black and Mexican-American areas (Pet.

App. 24a). Students in kindergarten and first grade

were to attend schools nearest their homes, and ex

isting attendance zones were retained for other grades

if transportation time to another school exceeded

thirty minutes each way (Pet. App. 24a-25a & n.40).

Under the Hall plan, 44% of the black students would

have attended schools in which the black enrollment

exceeded 90% (Hall Ex. 5 (1976)).

The plan submitted by the Educational Task Force

of the Dallas Alliance divided the DISD into five sub

districts (Pet. App. 26a). All the subdistricts but

one— South Oak Cliff— reflected the racial proportions

of the DISD as a whole (ibid.). Students in grades

K through 3 were to attend the nearest school that

would promote integration, with the distance not to

exceed four miles from their homes (ibid.). In grades

4 through 8, students living in naturally integrated

areas remained in their existing attendance zones and

students in other areas were assigned to schools in

16

17

the subdistrict that would reflect the racial propor

tions of the subdistrict (Pet. App. 27a). The attend

ance zones for students in grades 9 through 12 were

not altered, but students were to be given the option

of attending magnet schools or participating in a

majority-to-minority transfer program (Pet. App.

27a-28a).

2. The district court’s desegregation order

After conducting hearings on the various desegre

gation proposals, the district court filed an opinion

and order requiring implementation of a revised

version of the Dallas Alliance Task Force plan (Pet,

App. 4a-41a, 46a-120a).14 The district court’s plan

divided the DISD into six subdistricts (Pet. App.

53a). Four of these subdistricts had approximately

the same racial make-up as the system as a whole; the

remaining two subdistricts— Seagoville and East Oak

Cliff— had an 82% Anglo student population and

98% black student population respectively (Pet. App.

53a, 135a). Within the subdistricts elementary stu-

14 On March 10, 1976, the district court entered an opinion

and order generally approving the concepts of the plan sub

mitted by the Dallas Alliance Task Force (Pet. App. 29a-41a).

The court subsequently entered a supplemental opinion and

final order (Pet. App. 46a-120a) setting forth the details of the

Task Force plan as modified. The actual plan submitted by

the Dallas Alliance contained no projected enrollment figures

by which the district court could compare its desegregative

impact with those of the other proposed plans. Projected en

rollments were only supplied later when the DISD submitted

its proposal for implementing the Dallas Alliance plan.

dents in grades K through 3 were to remain in their

neighborhood schools (Pet. App. 57a). In areas that

were not naturally integrated, students in grades 4

through 8 were assigned to centrally located inter

mediate and middle schools in the subdistrict (ibid.).

In naturally integrated areas, prior attendance pat

terns were continued for grades 4 through 8 (Pet.

App. 57a, 136a). High school students were to remain

in their neighborhood schools unless they chose to

attend magnet schools or to participate in a transfer

program (Pet. App. 58a). Majority-to-minority

transfers were permitted at all grade levels (Pet.

App. 68a-71a), and the magnet school concept wTas

expanded at the high school level and extended to

create “ academies” and “vanguard schools” with

special programs at the middle and intermediate

school level (Pet. App. 61a-63a).15 *

The student assignment provisions approved by the

district court maintained approximately 66 schools

in the DISD in which either the Anglo, the black, or

the combined black and Mexican-American enroll

ments exceeded 90% (Pet. App. 132a-133a & n.3).

The plan provided that all the schools serving the

East Oak Cliff subdistrict— which enrolled 27,500

students, including 41% of the black students in the

DISD— would have student bodies more than 90%

15 The plan approved by the district court also includes

a number of provisions regarding accountability, personnel,

and other matters that are not at issue here (Pet. App. 67a-

68a, 73a-83a).

19

black, or more than 90% black and Mexican-American

(Pet. App. 113a-118a, 132a-133a n.3).16

Approximately 50 one-race schools17 remained in

subdistricts other than East Oak Cliff, including high

schools in three of the five other subdistricts (Pet.

App. 133a). In the Southeast subdistrict, Lincoln

High School had a 100% black enrollment, while the

enrollment at Samuell High School was 89% Anglo

(Pet. App. 104a). In the Northeast subdistrict,

Bryan Adams High School was 95.2% Anglo, while

James Madison High School had 98.1% black stu

dents and 1.7% Mexican-Americans (Pet. App. 97a).

In the Northwest subdistrict, both Hillcrest High

School and White High School were 96% Anglo,

whereas Pinkston High School had a combined black

16 Appendix A to the district court’s opinion erroneously

listed James Bowie elementary school, which had 29.7% Anglo

students, in the East Oak Cliff subdistrict (Pet. App. 114a),

but that error was corrected in the district court’s supple

mental opinion, which indicated that Bowie was in the South

west district (Pet. App. 125a).

The earliest enrollment statistics by race in the record,

those for the 1966-1967 school year (before full implementa

tion of the stair-step plan), reveal that eight of the schools

serving East Oak Cliff were already more than 90 % black in

enrollment that year (Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

(First Set), App. Vol. 4, filed Nov. 18, 1970).

17 The court of appeals used the term “ one race” to describe

a school where either the Anglo enrollment or the combined

black and Mexican-American enrollment exceeded 90% (Pet.

App. 132a n.3), and we do the same.

20

and Mexican-American enrollment of 95.1% (Pet.

App. 90a).18 *

The remaining one-race schools are found pri

marily among the elementary schools serving grades

K through 3. This group includes 21 schools outside

East Oak Cliff which had either Anglo, black, or

combined black and Mexican-American enrollments

of more than 90% in 1966-1967, the first year for

18 In 1966-1967 Hillcrest, Adams and Samuell were 100%

white schools, and White had only one black student (Answers

to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories (First Set), App. Vol. 4, filed

Nov. 18, 1970). That same year Lincoln and Madison had

100% black enrollments (ibid.). Thus, of the seven one-race

high schools remaining outside East Oak Cliff under the dis

trict court’s order, six were one-race schools the year before

full implementation of the stair-step plan in 1968.

The racial separation in these schools has decreased slightly

as a consequence of the voluntary integration accomplished

by students exercising majority-to-minority transfer options.

The April 15, 1979 report of the DISD to the district court

contains the following figures:

Lincoln Samuell Bryan Adams

.18% Anglo 74.53% Anglo 86.26% Anglo

99.82% Black 18.19% Black 4.86% Black

James Madison

6.79% Mexican-American 6.82% Mexican-

American

Hillcrest

98.81% Black

.75% Mexican-American

.30% Anglo 78.14% Anglo

18.15% Black

1.81% Mexican-American

W. T. White Pinkston

90.38% Anglo

4.39% Black

3.61% Mexican-American

1.06% Anglo

82.08% Black

16.45% Mexican-American

21

which the DISD has provided racial statistics.19 Al

though the district court’s assignment plan employs

grade configurations of K-3, 4-6, and 7-8, most of the

DISD elementary schools include grades K through

6 (Pet. App. 136a n.9), so that in a single elementary

school children in grades K-3 would be in one-race

classes, but those in grades 4-6 would be in inte

grated classes. Looking only at grades K-3, there are

53 schools in the DISD in which the Anglo or com

bined black and Mexican-American enrollments for

those grades exceed 90% .20

Although the district court’s plan did have some

integrative effect on students in grades 4 through 8,

it did not result in any overall desegregation of black

students. Prior to implementation of the plan, ap

proximately 59.19% of the black students and 16.41%

of the Anglo students in the DISD attended one-race

schools.21 As of the 1978-1979 school year, the third

year under the district court’s plan, the percentage

of Anglo students enrolled in one-race schools had

19 The schools are Arlington Park, Brown, Cabell, Carr,

Carver, Colonial, Darrell, Dunbar, Frazier, Gooch, Harris,

Hassell, Hexter, Kramer, Lagow, Moseley, Ray, Rice, Thomp

son, Tyler, and Wheatley (Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interroga

tories (First Set), App. Vol. 4, filed Nov. 18, 1970).

20 These figures are derived from the April 15, 1979 report

of the DISD to the district court.

21 This figure is derived from the DISD’s report to the

district court on December 1, 1975. Data from that report

are contained in the DISD’s Answers to Interrogatories of

Strom Intervenors, filed with the district court on December

5, 1975.

declined to 8% , but 59% of the black students in the

district were still enrolled in one-race schools.22

E. The second appeal

Both the plaintiffs and the N.A.A.C.P. plaintiff-in-

tervenors appealed from the district court’s remedial

order, contending that the student assignment pro

visions were inadequate to eliminate the continuing

effects of the DISD’s past segregation. On April 21,

1978, the court of appeals, in the order challenged

here, remanded the case for formulation of a new

student assignment plan including findings that would

“ justify the maintenance o f any one-race schools that

may be a part of that plan” (Pet. App. 145a).

The court of appeals did not hold that a remedial

plan for Dallas must eliminate all one-race schools;

it held only that the district court must make findings

regarding the reasons, if any, why one-race schools

could not be eliminated by application of the various

techniques previously approved by this Court (Pet.

App. 137a-138a):

The district court was instructed in the opinion

of the prior panel to consider the techniques for

desegregation approved by the Supreme Court in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edu

cation, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267 (1971). We

cannot properly review any student assignment

plan that leaves many schools in a system one

race without specific findings by the district

22 These figures are derived from the April 15, 1979 report

of the DISD to the district court.

28

court as to the feasibility of these techniques.

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

No. 75-3610 (5th Cir. April 7, 1978). There are

no adequate time-and-distance studies in the re

cord in this case. Consequently, we have no

means of determining whether the natural

boundaries and traffic considerations preclude

either the pairing and clustering of schools or

the use of transportation to eliminate the large

number of one-race schools still existing. See

Mims v. Duval County School Board, 329 F. Supp.

123, 133-134 (M.D. Fla. 1971).

Focusing on the problem presented by the continued

existence of one-race high schools, the court of ap

peals stated (Pet. App. 138a; footnotes om itted):

Although students in the 4-8 grade configura

tions are transported within each subdistrict to

centrally located schools to effect desegregation,

the district court’s order leaves high school stu

dents in the neighborhood schools. Within three

of the four integrated subdistricts, this results

in high schools that are still one-race schools.

The district court is again directed to evaluate

the feasibility of adopting the Swann desegrega

tion tools for these schools and to reevaluate the.

effectiveness of the magnet school concept. If the

district court determines that the utilization of

pairing, clustering or the other desegregation

tools is not practicable in the DISD, then the

district court must make specific findings to that

effect.

The court of appeals also considered several other

aspects of the district court’s remedial order that are

not at issue here. It held the district court had erred

in not requiring the Board to provide transportation

for students who choose to participate in the majority-

to-minority transfer plan (Pet. App. 138a-139a).

The appellate court affirmed the district court’s re

fusal to include the separate Highland Park school

system in the student assignment plan (Pet. App.

141a).28 And, in a related appeal, the court rejected

the claims of a group of citizens who opposed a

DISD plan to convert a shopping center in East Oak

Cliff into a school complex (Pet. App. 141a-145a).

On May 22, 1978, the court of appeals denied the

DISD’s petition for rehearing (Pet. App. 146a-147a).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

As required by the Texas Constitution, the DISD

operated separate schools for black students and

white students both before and after Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). In 1965-1967

the DISD, for the first time, implemented a federal 23

23 The plaintiffs had sought unsuccessfully in the district

court to include various independent school districts in the

desegregation plan. All of these except the Highland Park

Independent School District were dismissed on the plaintiffs’

motion. Highland Park serves two virtually all-white com

munities surrounded by the DISD. The district court had

concluded that for the past twenty years the Highland Park

school district had not engaged in segregation and that its

prior policy of discrimination had but a negligible effect on

the DISD, and on this basis the court refused to include High

land Park in the student assignment plan for the DISD. The

court of appeals affirmed (Pet. App. 141a).

25

court order requiring the elimination of segregatory

assignments by race, but it took no other steps to

dismantle its dual system, and the enrollment figures

at the time of trial in 1971 revealed the continua

tion of the racial separation so long mandated by

law. Almost all of the schools that were all-black at

the time of the first court-ordered desegregation re

mained virtually all-black. More than 90% of the

black students in the DISD continued to attend

schools where more than 90% of the students were

black. Moreover, by the time of trial the DISD had

not desegregated its faculty.

The district court correctly recognized that the

high degree of racial separation still found through

out the system was a vestige of the dual system that

had not been dismantled.

The DISD had an affirmative duty to dismantle

the dual system and eliminate its vestiges. Its ob

ligation was to remedy the continuing effects of its

longstanding segregation. This duty was not satis

fied when the DISD— under court order— eliminated

racial criteria for admission in 1965, which was

only the first step in dismantling the dual system.

The DISD had a duty to adopt a plan that would

be effective to desegregate its school system. It had

not done so at the time of trial.

II

Since the DISD had not dismantled its dual sys

tem, the district court’s responsibility was to fashion

a remedy to convert to a unitary system and elimi

nate the vestiges of the prior dual system root and

branch. The task of its remedial decree was to

achieve “ the greatest possible degree of actual de

segregation, taking into account the practicalities of

the situation.” Davis v. Board o f School Commis

sioners, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1972).

The district court’s remedial order left intact ma

jor elements of the prior dual system: 66 one-race

schools, many of which were operating as one-race

schools before the first court-ordered desegregation.

The court of appeals properly remanded the case for

reconsideration of the remedial order because the rec

ord did not establish that the order achieved the

greatest degree of desegregation that was practical.

The court of appeals correctly recognized that in

a district, like the DISD, with a long history of seg

regation, there is a presumption against the con

tinued existence of so many one-race schools, and

that the DISD had the burden of showing that racial

composition of the schools was not the result of its

own past segregative actions. Since the DISD failed

to carry the burden of showing that its past segrega

tive acts had not affected the remaining one-race

schools, the court of appeals correctly remanded the

case for reconsideration and further findings to per

mit the district court accurately to determine the

greatest degree of desegregation that would be

practical.

The district court stated that desegregation of the

all-black East Oak Cliff subsection would be imprac

tical, but the record did not include studies showing

that the times and distances for the necessary student

transportation (proposed in several plans before the

26

27

district court) were too great to be practical. The

court of appeals properly remanded the case for spe

cific findings why tools such as pairing and cluster

ing of schools could not be used to desegregate part

or all of East Oak Cliff, which contained more than

27,000 black students.

The district Court also stated that desegregation

of the high schools would not be practical— even

though it ordered desegregation of the smaller junior

high schools. Again the court of appeals properly

remanded the case for specific findings why the high

schools could not, with practicality, be desegregated

as well.

The district court concluded that students in grades

K through 3 were not mature enough to be assigned

anywhere but their neighborhood schools. The dis

trict court did not consider whether desegregation

of some or all of the one-race elementary schools

could be achieved if transportation time were care

fully limited because of the students’ age. Again,

the court of appeals properly remanded the case for

more specific findings regarding the feasibility of

greater desegregation.

The court of appeals did not err in remanding the

case for reconsideration of plans involving more stu

dent transportation. The district court’s limited use

of pairing, clustering, and student transportation—

together with its heavy reliance on magnet schools—

had not been effective to achieve the desegregation of

the DISD’s former dual system. Accordingly, the

court of appeals properly directed the district court

2 8

to consider the feasibility of making greater use of

techniques that promised to be effective to dismantle

the dual system.

ARGUM ENT

I

A SYSTEM W ID E R EM EDY IS APPROPRIATE BE

CAUSE TH E BOARD H AS NOT FULFILLED ITS

CONTINUING OBLIGATION TO ELIM IN ATE THE

VESTIGES OF THE FORMER DUAL SCHOOL SYS

TEM TH AT PERSIST THROUGHOUT THE DISTRICT

A. Vestiges of the DISD’s dual school system remain

throughout the district

Until its repeal on August 5, 1969, Article 7, § 7

of the Texas Constitution required racial segregation

in the public schools throughout the State, and Dallas

operated a constitutionally and statutorily mandated

dual school system both before and after Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown

7 ).24

Although a court-ordered stair-step desegregation

plan eliminated separate racial assignment zones for

all grades by 1967, new attendance zones were drawn

without any effort to encourage integration, and in

most cases the schools attended by black students be

fore the implementation of the stair-step order re

mained all-black.24 25 26 Enrollment figures for the 1966-

24 Many state statutes effectuating Article 7 § 7 are set

forth in Respondents’ Br. at 11-12 n.4.

26 Although there are no school-by-school enrollment figures

by race for years prior to 1966-1967, it is possible to identify

many schools attended by blacks in earlier years because the

faculties were segregated as well and the record includes the

all-black faculties in the early 1960’s (Answer to Interroga-

29

1967 school year reveal that the student bodies in

101 of the DISD’s 171 schools were either 100%

black or 100% Anglo.26

At the time of trial in 1971, this high degree of

racial separation persisted. The schools that blacks

had attended before 1965 remained virtually all

black. More than 90% of the black students in the

DISD attended schools where less than 10% of the

students were Anglo, and 63% of the black students

attended schools where less than 1% of the students

were Anglo (Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

(First Set), App. Yol. 1, filed Nov. 18, 1970). More

than two-thirds of the Anglo students attended

schools where Anglos made up 90% or more of the

student body (ibid.). And the Board had made no

provision for majority-to-minority transfers (see II

Tr. 560-563, 645-647 (1971)).

After conducting a full hearing on the current

conditions in the DISD, the district court concluded

that the extreme racial separation throughout the

tory 1(d), Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories (First Set),

filed Nov. 18, 1970). There were 37 schools that had all-black

faculties before 1965. The 1966-1967 enrollment figures for

these 37 schools reveal that 29 continued to have black en

rollments exceeding 90%, three had closed (Attucks, Eagle

Ford, and Starks), and five others had changed to less than

90 % black enrollment (Sequoyah, Pinkston, Douglass, Roberts,

and Miller). The extent to which the change in these five

schools is attributable to enrollment of Mexican-American,

rather than Anglo, students is not reflected in the record (see

note 26, infra).

26 As previously noted (page 4, supra, note 3), until the

1967-1968 school year the DISD counted Mexican-American

students as white.

30

DISD was the legacy of the prior dual system that

had never been effectively dismantled. The basis for

that conclusion was the court’s finding (page 9,

supra) that 119 schools in the DISD were either 90%

or more Anglo or 90% or more black and Mexican-

American in their enrollments and that 91% of the

black students attended predominantly minority

schools, while only 3% of the black students attended

majority Anglo schools.27

The DISD’s faculty assignments also evidenced

the continuing effects of the DISD’s prior dual sys

tem. No effort was made to desegregate the faculty

of the DISD during the years the court-ordered stair

step plan was being implemented. Although Superin

tendent Estes testified that a phased faculty deseg

regation program affecting 20 schools was adopted

in 1968 (II Tr. 455 (1971)), by the time of trial

in 1971, 88.8% of the black teachers in the DISD

were still assigned to schools where the student body

was at least 90% black, and less than 5% of the

27 Petitioners and respondents engage in a heated debate

over the question whether the district court found that the

DISD was operating a dual system, or merely that there were

still vestiges of the prior dual system. The district court

did not focus on this distinction and its 1971 liability finding

refers to vestiges, whereas its April 7, 1976 supplemental

opinion assumes that in 1971 the court found the DISD was

operating a dual system (412 F. Supp. 1211).

In our view, the narrow distinction petitioners seek to draw

between the vestiges of a dual system and the dual system

itself is meaningless where, as here, school officials have

taken no action to alter the racial characteristics of the schools

that were once segregated and what remained is a system

where more than 90% of the black students remain in all

black schools.

black teachers were assigned to schools where 90%

or more of the students were Anglo (Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 4 (1971)). Only after trial of this case began

did the DISD announce a plan to desegregate all its

faculty in accordance with the Fifth Circuit’s 1969

decision in Singleton. As this Court pointed out in

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, No. 78-

627 (July 2, 1979), slip op. 11-12 (Dayton II), such

continuing faculty segregation is “ strong evidence

that the Board was continuing its efforts to segre

gate students.” See also Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 18 (1971).

The district court correctly rejected the DISD’s

claim that the racial separation in the schools was

not attributable to the lingering effect of state-im

posed segregation, but to changes in residential pat

terns since the institution of the stair-step plan in

1965. Once the plaintiffs have established, as they

did here, that the school board’s intentional past acts

created a dual school system, it becomes the burden of

the school authorities to show that the current segre

gation “ is not the result of present or past discrimina

tory action on their part.” Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S.

at 26. Where, as here, the record establishes that

there has been a dual system, “ the systemwide na

ture of the violation funishefs] prima facie proof

that current segregation in the * * * schools was

caused at least in part by prior intentionally segrega

tive official acts.” Dayton II, supra, slip op. 9.

The evidence introduced by the DISD did not carry

this burden. Superintendent Estes testified that be

32

tween 1965 and 1970— during and after implementa

tion of the stair-step plan-—he believed approximately

19 schools in the district had changed from ma

jority Anglo to majority black and Mexican-Ameri

can because of changes in residential patterns (II

Tr. 514-520 (1971)). As the district court observed,

this evidence fell far short of demonstrating that the

Board’s prior segregative acts had not caused the

conditions of racial separation that were still so evi

dent throughout the district, since Estes’ testimony

accounted for only a fraction of the one-race schools,

providing no explanation for the existence of 97 other

one-race schools throughout the DISD in 1970-1971,

most of which had the same racial composition be

fore and after implementation of the stair-step plan.

Moreover, even assuming that changes in residential

patterns did influence the racial composition of the

19 schools Estes identified, school segregation— which

often contributes to housing segregation— may never

theless have played an important part in determining

the racial composition of the schools. See Columbus

Board of Education v. Penick, No. 78-610 (July 2,

1979), slip op. 14-15 n.13.

B. The DISD was under a continuing obligation to

eliminate these vestiges

1. As this Court reaffirmed most recently last

Term in Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,

supra, slip op. 8 (citations omitted), a school system,

like the DISD, that has operated dual schools is—

“ clearly charged with the affirmative duty to take

whatever steps might be necessary to convert to

33

a unitary system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated root and branch.” * * *

Each instance of a failure or refusal to fulfill

this affirmative duty continues the violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

The DISD’s “ continuing ‘affirmative duty to dis

establish the dual school system’ is therefore beyond

question.” Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,

supra, slip op. 10, quoting McDaniel v. Barresi, 402

U.S. 39, 41 (1971).

2. Relying on Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406 (1977) (Dayton I ) , the

Brinegar petitioners contend that the district court

erred in focusing on the question whether the one-

race schools throughout the district were vestiges of

the prior dual system, rather than the question

whether the current racial separation in the schools

had been caused by the Board’s intentionally segre

gative actions.28 But as this Court’s opinion in Day-

ton 11 makes clear, the DISD had an affirmative duty

28 The record before the Court in Dayton 1 showed only

isolated instances of segregative acts in a system where

“mandatory segregation by law * * * ha[d] long since ceased.”

433 U.S. at 420. As this Court observed in Columbus Board of

Education V. Penick, supra, slip op. 7 n.7, Dayton I held that

record was “ insufficient to give rise to an inference of system-

wide institutional purpose and * * * did not add up to a

facially substantial systemwide impact.”

Here, in contrast to the record in Dayton I, statutory segre

gation ceased when the stair-step plan was fully implemented

in 1967, less than four years before the district court’s lia

bility finding, and almost all of the schools that had been

black schools in 1966-1967 were still more than 90% black.

34

to desegregate, a duty that required it “ to do more

than abandon its prior discriminatory purpose” (slip

op. 11), and the lower courts were “quite justified in

utilizing the Board’s total failure to fulfill its affirma

tive duty * * * to trace the current, systemwide seg

regation back to the purposefully dual system of the

1950’s and to the subsequent acts of intentional dis

crimination” (slip op. 14). Dayton II holds “ the

measure of the post-Brown conduct of a school board

under an unsatisfied duty to liquidate a dual system

is the effectiveness, not the purpose, of the actions in

decreasing or increasing the segregation caused by

the dual system” (slip op. 10-11). In the instant

case, petitioners concede that the DISD deliberately

maintained separate schools for black and white chil

dren in Dallas until the mid-1960’s. So long as the

effects of that intentional conduct remain unremedied,

no additional finding of intent is necessary before the

court may act to remedy the DISD’s perpetuation or

aggravation of those effects.29

29 The Brinegar petitioners also rely heavily on this Court’s

statement in Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 240-248

(1976), that evidence of a racially discriminatory purpose is

necessary to prove a violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

Davis is fully consistent with Dayton II. The Brinegar peti

tioners overlook the portion of the Davis opinion stating that

where there is an unremedied purposeful violation of equal

protection, subsequent related conduct would be unconsti

tutional if it has an impact which perpetuates the past dis

crimination or if it was performed with a discriminatory pur

pose. Citing Wright V. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972), the Dams opinion explained, 426 U.S. at 243, that

no independent showing of invidious intent underlying the

3, The Board’s affirmative duty was not, as the

Curry petitioners contend (Curry Br. 17-21), satis

fied by the implementation of the court-ordered stair

step plan. The Fifth Circuit pointed out in its opin

ion on the first appeal that the stair-step plan was

a limited remedy that replaced overtly racial student

assignments with a “neighborhood school” policy, but

was not designed to eliminate all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation ( Tasby v. Estes, supra, 517

F.2d at 95 ):

The “stair-step” desegregation process we di

rected in 1960 and implemented by the DISD

the following year merely involved the elimina

tion of racial criteria for the admission of stu

dents to the DISD’s schools. The DISD was not

directed to take affirmative action to remove the

vestiges of its formerly statutorily-required dual

education system through such techniques as

“ freedom-of-choice” , “pairing” , or “majority-to-

minority transfer program.” In fact the DISD

took no further steps to eliminate the traces of

segregation than required to do by the terms of

our 1965 desegregation order.

As this Court stated in Green v. County School Board,

supra, 391 U.S. at 437, “ [i]n the context of the state-

imposed segregated pattern of long standing,” the

fact that a school board has “ opened the doors of the

school district’s decision to divide and form a new district

was necessary in Wright, where the effect of that action was

to undermine a court-ordered plan to remedy purposeful dis

crimination previously found in the Emporia public schools.

The same general principle was reaffirmed in Dayton II.

36

former ‘white’ school to Negro children and of the

‘Negro’ school to white children merely begins, not

ends, our inquiry whether the Board has taken steps

adequate to abolish its dual, segregated system.”

The circumstances of this case are much like those

of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edu

cation, supra. As this- Court recently noted in Co

lumbus Board of Education v. Penick, supra, slip op.

9, “an initial [de] segregation plan had been entered

[in Swann] in 1965 and had been affirmed on appeal.

But the case was reopened, and in 1969 the school

board was required to come forth with a more effec

tive plan.” In Swann, as here, the earlier remedial

order did not fulfill the Board’s obligation because it

“ fell short of achieving [a] unitary school system.”

402 U.S. at 7. Although the racially neutral geo

graphic zoning plan had been in force for several

years, two-thirds of all black students were still at

tending schools where 99% or more of the student

body was black (ibid.).30 Accordingly, it was neces

sary to implement a more effective desegregation

plan.

As we have shown, supra at pages 28-31, the DISD’s

racially neutral zoning plan was equally ineffective in

eliminating the effects of the prior system of segre-

30 Similarly, in Green V. County School Board, supra, 391

U.S. at 441, the Court found the school board’s adoption

of a freedom of choice student enrollment plan had not satis

fied its obligations when after three years of operation, 85%

of the black students were still in a one-race school.

gation, and accordingly the DISD’s duty had not been

satisfied.31

4. The Curry petitioners also contend (Curry Br.

30) that the far North Dallas area where they re

side was settled after Brown I, and that the district

court erred in including North Dallas in its remedial

plan because the racial composition of the schools in

that area was solely the result of pi edominantly

white residential settlement, not the DISD s segrega

tive actions.33

37

81 This is clearly not a case like Pasadena City Board of

Education V. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976), where the dis

trict court had implemented a comprehensive scheme that

effectively desegregated the student bodies of every school

throughout the district, and then ordered the school board

to take further action to realign attendance boundaries from

year to year in order to maintain a permanent racial balance

throughout the district. Pasadena follows up on the Court s

cautionary comment in Swann that “ ‘ [n] either school author

ities nor district courts are constitutionally required to make

year-by-year adjustments of the racial composition of student

bodies once the affirmative duty to desegregate has been ac

complished and racial discrimination through official action

is eliminated from the system.’ ” 427 U.S. at 436, quoting

Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 31-32. But here, as in Swann itself,

a second remedial order is necessary where an apparently

neutral assignment plan has been insufficient to counteract

the continuing effects of past school segregation. 402 U.S. at

28. See also University o f California Regents V. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265, 300-302 (1978) (opinion of Powell, J-), 353-355

(opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ.) ;

United Jewish Organizations V. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 159-161

(1977) (opinion of White, J.) ; Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 425, 435 (1975).

82 The court of appeals rejected a similar claim by the

Curry petitioners on the first appeal (Tasby V. Estes, supra,

517 F.2d at 108).

38

The record does not support this claim. It estab

lishes that all but one of the eight schools in the far

North Dallas area were established as one-race schools

before full implementation of the stair-step plan that

was the first step toward eliminating the dual sys

tem in the DISD.33 All but one of these schools opened

with all-white faculties between 1958 and 1965,34 35

and all but one had more than 90% white enrollment

during the 1966-1967 school year, the first year for

which enrollment data by race are available.85 The

remaining school, Nathan Adams, opened in the 1967-

1968 school year with a more than 90% white enroll

ment and an all-white faculty.36 Since the far North

Dallas schools were thus part of the dual system

operated by the DISD, the district court did not err

in including those schools in its remedial order.37

33 The schools are Nathan Adams, Cabell, Degolyer, Gooch,

Marcus, Withers, and Marsh Junior High Schools, and W. T.

White High School.

34 Answer to Interrogatory 1(d), Answers to Plaintiffs’

Interrogatories (First Set) App. Vol. 4, filed Nov. 18, 1970.

35 Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories (First Set) App.

Vol. 4, filed Nov. 18, 1970.

38 Ibid.

37 There is no merit to the Curry petitioners’ contention

(Curry Br. 30) that the district court, made a finding that

their schools were not affected by the DISD’s segregative acts.

The following passage, on which the Curry petitioners base

their argument, is simply a general statement about the

difficulty of constructing a remedial order; the district court

was discussing the question of remedy rather than violation

and was not referring specifically to North Dallas or to any

particular section of the city (342 F. Supp. at 951) :

The adoption of a plan of desegregation for a school

system of the size and complexity of DISD has been

39

II

THE COURT OF APPEALS PROPERLY REMANDED

THE CASE FOR CONSIDERATION OF THE FEASI

BILITY OF DESEGREGATING THE REMAINING

ONE-RACE SCHOOLS

In a school desegregation case, “ [a]s with any

equity case, the nature of the violation determines

the scope of the remedy.” Swann v. Ckarldtte-Meck-

lenburg Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 16.

See Dayton I, supra, 433 U.S. at 420. Where, as

here, the condition that violates the Constitution is

the creation of a dual system, with separate schools

for black and white students, the appropriate remedy

is conversion to a unitary system where there are

no longer black schools or white schools, but “ just

schools.” Green v. County School Board, supra, 391

U.S. at 442. In effecting that conversion, the goal

is “ to achieve the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation, taking into account the practicalities

of the situation.” Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971). The obligation im

posed by the Constitution, however, “ does not mean

that every school in every community must always

reflect the racial composition of the school system

as a whole.” Swann v. Charlottee-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 24.

The court of appeals faithfully applied these prin

ciples in reviewing the district court’s remedial or-

commented upon briefly. The problems result, of course,

from private housing patterns that have come into ex

istence and not from any action of the DISD.

40

der. It remanded for further consideration of the

student assignment provisions— which left intact ma

jor elements of the prior dual system— because the

record did not establish that those provisions would

accomplish the maximum desegregation practical in

the circumstances.38

38 Despite petitioners’ criticisms of the court of appeals

(see Brinegar Br. 28), it is clear that that court did not order

the district court to eliminate all one-race schools, and did

not exceed the proper bounds of appellate review. The court

of appeals expressly recognized the possibility that the dis

trict court’s revised student assignment plan might include

some one-race schools, and accordingly it remanded not only

“ for the formulation of a new student assignment plan,” but

also “ for findings to justify the maintenance of any one-race

schools that may be a part of that plan” (Pet. App. 145a).

By remanding to the district court for further findings and

reformulation of the student assignment plan, the court of

appeals scrupulously adhered to the proper role of an appel

late court. It attempted to review the district court’s findings

in support of its remedial order, and, upon determining that

the district court’s generalized findings were insufficient, it re

manded the case for further findings and reformulation of the

plan instead of instituting its own more sweeping remedy.

Cf. Dayton I, supra, 433 U.S. at 417-418.

Petitioners also criticize the length, delay, and uncertainty

that often characterizes school desegregation litigation. But

these problems do not stem from the courts. The cases where

there have been excessively long delays have generally in

volved school districts that have operated dual systems for

decades and that have been grudging—if not recalcitrant—in

converting to a unitary system. In this case, for example, six

appeals were required before the school district implemented

the stair-step plan and ceased using racial criteria to make

student assignments. See supra pages 4-5, note 4.

The district court's order left intact 66 one-race

schools, most of which were operating as one-race

schools in 1965 before the DISD began to implement

the first court-ordered desegregation of its statutory

dual system. The court’s plan divided the DISD into

six subdistricts, one of which— East Oak Cliff— “ is

nearly all black and contains only one-race schools

(Pet. App. 132a). The plan provided that except

for those who elect to exercise the option of majority-

to-minority transfers, all of the more than 27,500

students in the subdistrict would continue to attend

the all-black schools located within the subdistrict.

Outside of East Oak Cliff, the district court’s plan