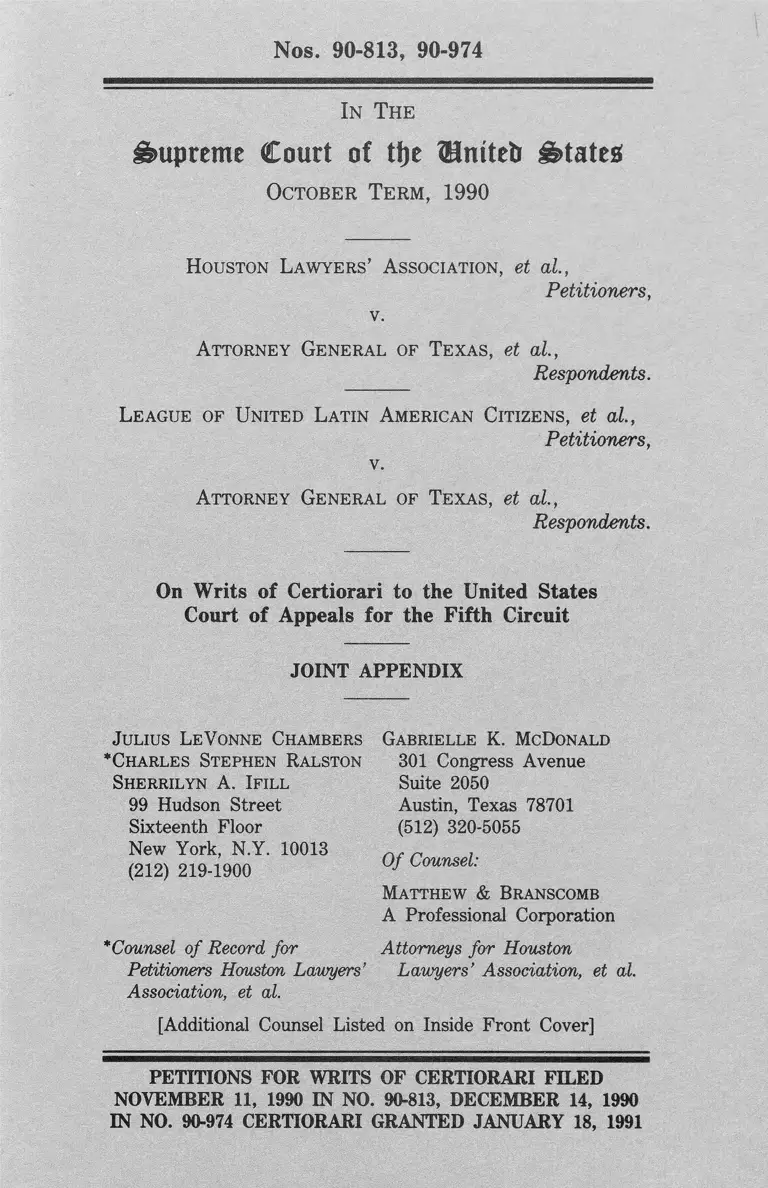

Houston Lawyers' Association v. Attorney General of Texas Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 18, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Houston Lawyers' Association v. Attorney General of Texas Joint Appendix, 1991. 7c609985-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/62262cc3-f718-442c-82e3-2d2a324201ba/houston-lawyers-association-v-attorney-general-of-texas-joint-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N os. 90-813, 90-974

In T h e

Supreme Court of ttjc ®mteb States

Oc t o b e r T e r m , 1990

Houston Law yers’ A ssociation, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

A ttorney General of Texa s , et al,

Respondents.

League of U nited Latin American Citizens, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

A ttorney General of Texas, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

JOINT APPENDIX

Julius LeVonne Chambers

‘ Charles Stephen Ralston

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

*Counsel of Record for

Petitioners Houston Lawyers’

Association, et al.

Gabrielle K. McDonald

301 Congress Avenue

Suite 2050

Austin, Texas 78701

(512) 320-5055

Of Counsel:

Matthew & Branscomb

A Professional Corporation

Attorneys for Houston

Lawyers’ Association, et al.

[Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Front Cover]

PETITIONS FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI FILED

NOVEMBER 11, 1990 IN NO. 90-813, DECEMBER 14, 1990

IN NO. 90-974 CERTIORARI GRANTED JANUARY 18, 1991

* William L. Garrett

Brenda Hull Thompson

8300 Douglas, Suite 800

Dallas, TX 75225

(214) 369-1952

*Counsel o f Record for

Petitioners LULAC, et al.

Texas Rural Legal Aid, Inc.

David Hall

259 S. Texas

Weslaco, TX 78596

(512) 968-6574

Rolando L. Rios

201 N. St. Mary’s, #521

San Antonio, TX 78205

(512) 222-2102

Attorneys for LULAC, et al.

Susan Finkelstein

201 N. St. Mary’s, #624

San Antonio, TX 78205

(512) 222-2478

Attorneys fo r Petitioner Christina Moreno

*Edward B. Cloutman III E. Brice Cunningham

3301 Elm St. 777 S.R.L. Thornton

Dallas, TX 75226 Dallas, TX 75203

(214) 939-9222 (214) 428-3793

*Counsel of Record fo r Attorneys fo r Jesse Oliver, et al.

Petitioners Jesse Oliver, et al.

Dan Morales

Mary F. Keller

Renea Hicks

(Counsel o f Record)

Javier Guajaro

Office of the Attorney

General

Supreme Court Building

1401 Colorado Street

Austin, TX 78701-2548

(512) 463-2085

Attorneys for Respondent

Attorney General of Texas

Seagal V. Wheatley

(Counsel o f Record)

Donald R. Philbin, Jr.

Oppenheimer, Rosenberg

Kelleher & Wheatley,

Inc.

711 Navarro, Sixth Floor

San Antonio, TX 78205

(512) 224-2000

Attorneys for Bexar County

Respondents

J. Eugene Clements

(Counsel o f Record)

Evelyn V. Keys

Porter & Clements

700 Louisiana Street

Suite 3500

Houston, TX 77002-2730

(713) 226-0600

Attorneys for Respondent

Judge Sharolyn Wood

Robert H. Mow, Jr.

(Counsel of Record)

Hughes & Luce

2800 Momentum Place

1717 Main Street

Dallas, TX 75201

(214) 939-5500

Attorneys for Dallas County

Respondents

T able o f C ontents

Item: Page:

1. Docket Entries............................................................ 2a

2. Complaint in Intervention of Houston Lawyers’ Assoc.,

et al.......................................................................... 8a

3. Complaint in Intervention of Jesse Oliver, et al. . .24a

4. Answer of Judge Sharolyn Wood to Complaint in

Intervention of Houston Lawyers’ Assoc., et al. . .35a

5. Answer of Judge Sharolyn Wood to Amended Complaint

ofLULAC, e ta l.................................................... 63a

6. Second Amended Complaint of LULAC, et al. . . 88a

7. Answer of Jim Mattox, et al., to Second Amended

Complaint of LULAC, et al.............................. 102a'

8. First Amended Answer of Judge F. Harold Entz to

Second Amended Complaint of LULAC, et al. . .1.12a

9. Answer of Judge F. Harold Entz to Complaint in

Intervention of Jesse Oliver, et al.............. 119a

10. Answer of Jim Mattox, et al., to Complaint in

Intervention of Houston Lawyers’ Assoc., et al. . 126a

11. Trial Exhibit No. 1 of Judge Sharolyn Wood . . . 132a

12. Trial Exhibit No. 2 of Judge Sharolyn Wood . . . 139a

13. Motion to Intervene of Judge Tom Rickhoff, et a ll 4 6a

14. Response of Jim Mattox, et al., to Motion to Intervene

of Tom Rickhoff, et al................................. 157a

15. Order of January 2, 1990.............................. 158a

16. Order of January 11, 1990 .............................. 180a

2a

Date

7/11/88

8/15/88

9/27/88

11/30/88

1/11/89

1/12/89

R elevant D o c k et E ntries

No. Description

1 Complaint filed and 15 summonses

issued (sm)

2 Amended complaint by LULAC-

Council 4434, LULAC-Council

#4451, Christina Moreno, Aquilla

Watson, LULAC (Statewide) James

Fuller, Matthew W. Plummer Sr,

amending complaint [1-1] [Entry date

8/17/88]

7 Answer by William P. Clements, Jim

Mattox, Jack M. Rains, Thomas R.

Phillips, John F. Onion Jr., Joe E.

Kelly, Joe B. Evins, Sam B. Paxson,

Weldon Kirk, Charles J. Murray, Ray

D. Anderson, Joe Spurlock II (sm)

17 Motion by Midland County to

intervene (sm) [Entry date 12/1/88]

20 Motion by LULAC-Council 4434,

LULAC-Council #4451. Christina

Moreno, Aquilla Watson, LULAC

(Statewide), James Fuller, Matthew

W. Plummer Sr. to dismiss as to

defendant William Clements only (sm)

23 Order granting motion to dismiss as to

defendant William Clements only [20-

1] (sm)

3a

1/23/89 24 Motion by Houston Lawyers Asso to

intervene (sm)

1/23/89 Received Complaint in intervention of

Houston Lawyers Association (sm)

1/30/89 28 Motion by Dist Jdgs of Travis with

memorandum in support to intervene

(sm) [Entry date 1/31/89]

1/30/89 Received answer of District Judges of

Travis County (sm) [Entry date

1/31/89]

1/31/89 29 Motion by Fred Tinsley, Joan Winn

White, Jesse Oliver to intervene (sm)

2/1/89 30 Response by Jim Mattox, Jack M.

Rains, Thomas R. Phillips, John F.

Onion Jr., Ron Chapman, thomas J.

Stovall Jr., James F. Clawson Jr., Joe

E. Kelly, Joe B. Evins, Sam B.

Paxson, Weldon Kirk, Charles J.

Murray, Ray D. Anderson, Joe

Spurlock II to motion to intervene [24-

1] (sm) [Entry date 2/2/89]

2/3/89 31 Response by LULAC-Council 4434,

LULAC-Council #4451, Cristina

Moreno, Aquilla Watson, LULAC

(Statewide), James Fuller, Matthew

W. Plummer Sr. to motion to

intervene [24-1] (sm)

2/9/89 32 Response by Jim Mattox, Jac, M.

Rains, Thomas R. Phillips, John F.

Onion Jr., Ron Chapman, Thomas J.

Stovall Jr., James F. Clawson Jr., Joe

E. Kelly, Joe B. Evins, Sam B.

4a

2/13/89

2/21/89

2/27/89

3/6/89

3/21/89

3/21/89

2/13/89

Paxson, Weldon Kirk, Charles J.

Murray, Ray D. Anderson, Joe

Spurlock II to motion to intervene [29-

1], motion to intervene [28-1] (sm)

34 Response by LULAC-Council 4434,

LULAC Council #4451, Cristina

Moreno, Aquilla Watson, LULAC

(Statewide), James Fuller, Matthew

W. Plummer Sr. to motion to

intervene [28-1] (sm)

35 Response by LULAC-Council 4434,

LULAC-Council #4451, Cristina

Moreno, Aquilla Watson, LULAC

(Statewide), James Fuller, Matthew

W. Plummer Sr. to motion to

intervene [29-1] (sm)

40 Motion by Sharolyn Wood to

intervene (sm)

45 Motion by F. Harold Entz to intervene

(sm)

50 Order granting motion to intervene

[45-1], granting motion to intervene

[29-1], granting motion to intervene

[28-1], granting motion to intervene,

[24-1], granting motion to intervene,

[17-1] (sm) [Entry date 3/7/89]

55 Answer by Sharolyn Wood to Houston

Lawyers Assoc, (sm)

56 Answer to complaint by Sharolyn

Wood against Legislative Black

Caucus, LULAC-Council 4434,

LULAC-Council #4451, Cristina

5a

4/6/89

4/13/89

5/12/89

4/6/89

5/24/89

Moreno, Aquilla Watson, LULAC

(Statewide), James Fuller, Matthew

W. Plummer Sr. (sm)

61 Motion by Legislative Black Caucus to

intervene as plaintiffs (sm)

Received complaint in intervention of

Legislative Black Caucus of Texas

69 Order granting motion to intervene as

plaintiffs [61-1] (sm)

85 Second Amended Complaint by

LULAC-Council 4434, LULAC-

Council #4451, Cristina Moreno,

Aquilla Watson, LULAC (Statewide)

Joan Ervin, Matthew W. Plummer,

Sr., Jim Conley, Volma Overton,

Willard Pen Conat, Gene Collins, A1

Price, Theodore M. Hogrobrooks,

Ernest M. Deckard, Mary Ellen

Hicks, Rev. James Thomas (sm)

100 Answer of Jim Mattox, Jack M.

Rains, Thomas R. Phillips, John F.

Onion Jr., Ron Chapman, Thomas J.

Stovall Jr., James F. Clawson Jr., Joe

E. Kelly, Joe B. Evins, Sam B.

Paxson, Weldon Kirk, Charles J.

Murray, Ray D. Anderson, Joe

Spurlock II to Second Amended

Complaint of LULAC-Council 4434,

LULAC-Council #4451, Cristina

Moreno, Aquilla Watson, LULAC

(Statewide) Joan Ervin, Matthew W.

Plummer, Sr., Jim Conley, Volma

Overton, Willard Pen Conat, Gene

Collins, A1 Price, Theodore M.

6a

5/24/89

11/8/89

11/27/89

12/22/89

12/26/89

1/2/90

5/24/89

Hogrobrooks, Ernest M. Deckard,

Mary Ellen Hicks, Rev. James

Thomas (sm)

101 First Amended Answer of F. Harold

Entz to Second Amended Complaint

of LULAC-Council 4434, LULAC-

Council #4451, Cristina Moreno,

Aquilla Watson, LULAC (Statewide)

Joan Ervin, Matthew W. Plummer,

Sr., Jim Conley, Volma Overton,

Willard Pen Conat, Gene Collins, A1

Price, Theodore M. Hogrobrooks,

Ernest M. Deckard, Mary Ellen

Hicks, Rev. James Thomas (sm)

102 Answer of F. Harold Entz to

complaint of Fred Tinsley, Joann

Winn White, and Jesse Oliver

282 Memorandum Opinion and Order

286 Order granting in part and denying in

part motion to alter or amend Order

of November 8, 1989

293 Motion to Intervene of Tom Rickhoff,

Susan D. Reed, John J. Specia, Jr.,

Sid L. Harle, Sharon Macrae, Michael

P. Peden

302 Order granting Motion to Correct

Clerical Mistake in Order of

November 27, 1989

309 Order granting in part, denying in part

Joint Motion for Entry of a Proposed

Interim Plan, granting in part Motion

7a

to Certify the Opinion and Order of

November 8, 1989 for Interlocutory

Appeal, denying a stay in the

proceedings, denying motion to

intervene (sm)

1/11/90 331 Order amending order of January 2,

1990 (sm)

8a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

MIDLAND-ODESSA DIVISION

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- x

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS

(LULAC), et al.,

PLAINTIFFS

Houston Lawyers’ Association

Alice Bonner, Weldon Berry, Francis Williams,

Rev. William Lawson, Deloyd T. Parker,

Bennie McGinty

PLAINTIFF-INTERVENORS

vs.

No. 88-CA-154

WILLIAM CLEMENTS, Governor of the State of

Texas, JIM MATTOX, Attorney General of the State

of Texas; JACK RAINS, Secretary of the State of

Texas, All in their official capacities;

THOMAS R. PHILLIPS; JOHN F. ONION, JR.;

RON CHAPMAN; THOMAS J. STOVALL, JR.; JAMES

F. CLAWSON, JR.; JOE E. KELLY; JOE B. EVINS;

SAM B. PAXSON; WELDON KIRK; CHARLES J.

MURRAY; RAY D. ANDERSON; JOE SPURLOCK II, All

in their official capacities as members of

the Judicial Districts Board of the State of Texas,

DEFENDANTS.

X

9a

COMPLAINT IN INTERVENTION

Introduction

1. This action is brought by five Black registered voters

and a membership organization of Black attorneys and

registered voters in Harris County, Texas, who seek to

intervene in MO 88 CA-154, LULAC v. Clements, for the

purpose of protecting their interests as Black voters in being

able to participate equally in the political process and elect

candidates of their choice in Harris County district judge

elections. They allege that the at large judicial electoral

districts scheme as currently constituted, denies Black

citizens an equal opportunity to elect the candidates of their

choice, in violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, and the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution.

They also allege that Art. 5, §7(a)i of the Constitution of the

State of Texas was adopted with the intention, and/or has

been maintained for the purpose of minimizing the voting

strength of Black voters, in violation of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, 42

10a

U.S.C. §1983 and section II of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. Plaintiff-intervenors

seek declaratory and injunctive relief enjoining the continued

use of the current judicial electoral districts scheme.

Jurisdiction

2. This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1331

and 1343 and 42 U.S.C. § 1973j(f). This is an action

arising under the statutes and Constitution of the United

States and an action to enforce statutes and constitutional

provisions that protect civil rights, including the right to

vote.

3. Plaintiffs seek declaratory and other appropriate relief

pursuant to the Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. §§

2201 and 2202.

Parties

4. Plaintiff-intervenor Houston Lawyers’ Association is a

member organization of seventy Black attorneys who reside

in the Harris County area, each of whom is a registered

voter, qualified to vote for district judges in Harris County.

As part of its organizational mission, the Houston Lawyers’

11a

Association has worked to promote the fair representation of

Blacks in the judiciary in Harris County.

5. Plaintiff-intervenor Weldon Berry is an adult Black

citizen of the United States who resides in Harris County,

Texas. He is registered to vote, and is qualified to vote for

district judges in Harris County. He was an appointed

district judge who lost in an at large election in Harris

County, Texas.

6. Plaintiff-intervenor Francis Williams is an adult Black

citizen of the United States who resides in Harris County,

Texas. He is registered to vote and is qualified to vote for

district judges in Harris County. He was an appointed

district judge who lost in an at large election in Harris

County, Texas.

7. Plaintiff-intervenor Alice A. Bonner is an adult Black

citizen of the United States who resides in Harris County,

Texas. She is registered to vote, and is qualified to vote for

district judges in Harris County. She was an appointed

district judge who lost in an at large election in Harris

County, Texas.

12a

8. Plaintiff-intervenor William Lawson is an adult Black

citizen of the United States who resides in Harris County,

Texas. He is registered to vote, and qualified to vote for

district judges in Harris County.

9. Plaintiff-intervenor Deloyd T. Parker, Jr. is an adult

Black citizen of the United States who resides in Harris

County, Texas. He is registered to vote, and qualified to

vote for district judges in Harris County.

10. Plaintiff-intervenor Bennie McGinty is an adult Black

citizen of the United States who resides in Harris County,

Texas. She is registered to vote, and qualified to vote for

district judges in Harris County.

11. Defendant William Clements is a white adult resident of

the State of Texas. He is sued in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of Texas. In his capacity as

Governor, defendant Clements is the chief executive officer

of the state and as such is charged with the responsibility to

see that the laws of the State are faithfully executed.

12. Defendant Jack Rains is a white adult resident of the

State of Texas. He is sued in his official capacity as

13a

Secretary of State of the State of Texas. In his capacity as

Secretary of State, he is the chief elections officer of the

state and as such is charged with the responsibility to

administer the election laws of the state. The Secretary of

State is further empowered under the Texas Election Code,

Section 31.005, to take appropriate action to protect the

voting rights of the citizens of Texas from abuse.

13. Defendant Jim Mattox is a white adult resident of the

State of Texas. He is sued in his official capacity as

Attorney General of the State of Texas. In his capacity as

Attorney General he is the chief law enforcement officer of

the state, and as such is charged with the responsibility to

enforce the laws of the state.

14. Defendants Thomas R. Phillips, John F. Onion, Ron

Chapman, Thomas J. Stovall, James F. Clawson, Jr., Joe E.

Kelly, Joe B. Evins, Sam M. Paxson, Weldon Kirk, Charles

J. Murray, Ray D. Anderson, and Joe Spurlock, II, are

members of the Texas Judicial Districts Board, which was

created by Art. 5, Sec. 7a of the Texas Constitution in 1985.

The Judicial Districts Board is required to enact statewide

14a

reapportionment if the legislature fails to do so, after each

federal decennial census. In addition to statewide

reapportionment, the Judicial Districts Board may

reapportion the judicial districts of the state as the necessity

arises in its judgment. The Judicial Districts Board is

comprised of twelve ex officio members, and one lawyer

member appointed by the Governor of the State of Texas.

No member of the Texas Judicial Districts Board has ever

been Black.

Factual Allegations

15. Texas has a history of official discrimination that

touched the right of Black citizens to register, to vote, and

otherwise to participate in the democratic process.

16. Primary elections were restricted to whites in Texas

until a Black resident of Houston successfully challenged this

discriminatory practice before the Supreme Court of the

United States in 1944.

17. The Texas Legislature created a state poll tax in 1902

which helped to disenfranchise Black voters until the use of

poll taxes was outlawed by the Supreme Court of the United

15a

States in 1966.

18. It has been estimated that the poll tax and white primary

reduced the number of Blacks participating in Texas

elections from approximately 100,000 in the 1890’s to 5,000

by 1906.

19. The State of Texas, and its political subdivisions are

covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, the special administrative preclearance provision

for monitoring all State and local voting changes.

20. Elections in Texas in general, and Harris County in

particular, are characterized by significant racial bloc voting.

In such elections, white voters generally vote for white

candidates and Black voters generally vote for Black

candidates. The existence of racial bloc voting dilutes the

voting strength of Black voters where they are a minority of

the electorate.

21. Texas has traditionally used, and continues to use

unusually large election districts, particularly in large

metropolitan areas such as Harris County, which have large

concentrations of minority voters.

16a

22. The political processes leading to nomination or election

in Texas in general, and Harris County in particular, are not

equally open to participation by Blacks, in that Blacks have

less opportunity than other members of the electorate to

participate in the political process and to elect representatives

of their choice. For example, Black citizens continue to

bear the effects of pervasive official and private

discrimination in such areas of education, employment and

health, which hinders their ability to participate in the

political process.

23. According to the 1980 Census, Texas had a total

population of 14,228,383. Blacks comprise approximately

12 percent of the State’s population.

24. No Black attorney has ever served on the Texas

Supreme Court or on the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

25. District judges in Texas are elected in an exclusionary

at large numbered place system.

26. Only 2% of district judges in Texas are Black. One (1)

percent of the State’s appellate justices are Black.

27. Harris County is made up of 27 cities in southeastern

17a

Texas, of which Houston is the largest. Houston is the

largest city in Texas. The population of Houston is

approximately 1,728,910. The Black population of Houston

is 440,346.

28. Harris County covers 1,723 square miles. According to

the Texas Data Center, in 1987 the population of Harris

County was 2,782,414. Blacks comprise approximately

19.5% of the Harris County population.

29. The voting age population of Harris County is

1,685,081. Eighteen (18) percent of the voting age

population in Harris County is Black.

30. Harris County is served by fifty-nine (59) district

judges. This is the largest number of district judges of any

judicial district in Texas. Harris County is also the largest

judicial district by population.

31. In recent years Black candidates have run for district

judge in almost every general election in Harris County, yet

only 4 judges out of 59 (6.7% of the district judges), are

Black.

32. In the November 1988 General Election for example,

18a

six Black candidates ran for twenty-five (25) contested

district judge positions. All six Black candidates lost,

despite overwhelming Black voter support. Similarly, in the

November 1986 General Election, of ten Black candidates

who ran in twenty (20) contested races, eight lost, despite

overwhelming support from Black voters.

33. Justices of the Peace are elected from single member

precincts within Harris County. There are 2 Black Justices

of the Peace in Harris County, elected from a precinct with

a majority Black voting age population.

34. There is a substantial degree of residential segregation

by race in Harris County.

35. Blacks in Harris County are a politically cohesive,

geographically insular minority and the judicial candidates

they support are usually defeated by a bloc voting white

majority.

36. Plaintiff-intervenor reallege the contents of paragraphs

of 11-29 of Plaintiffs’ First Amended Complaint, as they

relate to Harris County, Texas.

37. In 1985, Art. 5 §7 of the Texas Constitution of 1876

19a

was amended to include §7(a), which created the Judicial

Districts Board and provided in relevant part that:

The legislature, the Judicial Districts Boards, or

the Legislative Redistricting Board may not

redistrict the judicial districts to provide for any

judicial district smaller in size than an entire

county except as provided by this Section.

Vernon’s Ann. Tex. Const. Art. 5, §7(a)i.

38. Prior to the 1985 amendment, the Texas Constitution

provided that "The State shall be divided into as many

judicial districts as may now or hereafter be provided by

law, which may be increased or diminished by law." Art.

5, §7, Texas Constitution of 1876.

39. Although all counties in Texas have more than one

district judge, no county in Texas holds elections for single

member judicial districts. All districts judges in Texas run

in exclusionary at large, winner take all, numbered place

elections.

40. This electoral practice dilutes the voting power of

politically cohesive, geographically insular communities of

Black voters which could constitute effective voting

majorities in single member districts.

20a

41. Using 1980 census figures, it would be possible to draw

at least eleven single member geographically compact

districts of equal population in which the majority of the

voting age population is Black.

42. In the alternative, the failure to use a non-exclusionary

at large election system for district judges, dilutes the voting

strength of Black voters. The use of a non-exclusionary at

large voting system could afford Blacks an opportunity to

elect judicial candidates of their choice. For example, under

an at large system utilizing limited or cumulative voting,

Black voters would have a more equal opportunity to elect

district judges.

Allegations Regarding Intervention

43. On July 11, 1988 plaintiffs filed an action on behalf of

Mexican-American and Black plaintiffs challenging the

district judges schemes in forty-four (44) counties throughout

Texas, including Harris County.

44. Plaintiff-intervenors seek to intervene in this action,

pursuant to Rule 24 (a) of the Fed. Rule Civ. Procedure, in

order to protect the interests of Black plaintiffs in the Harris

21a

County area, who will be affected by a decision in this case.

They are entitled to intervene as a matter of right because

their application is timely, disposition of the action may

impair or impede the ability of Black voters to protect their

interest in ensuring that the method of electing district judges

in Harris County is equally open to Black citizens, and the

proposed-intervenors are not adequately represented by

existing parties.

First Claim for Relief

45. Plaintiffs reallege the contents of paragraphs 1-42.

46. The present districting scheme for Texas district judges

was adopted with the intention and/or has been maintained

for the purpose of minimizing the political strength of Black

voters in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution, section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§1973, and 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Second Claim for Relief

47. Plaintiffs reallege the contents of paragraphs 1-42.

48. The present districting scheme for Texas district judges

22a

has the result of making the political processes leading to

nomination and election less open to participation by Black

voters in that they have less opportunity than other citizens

to elect the candidates of their choice, and thereby violates

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42

U.S.C. §1973.

Relief

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs ask this Court to enter a

judgment:

1. Granting plaintiffs request to intervene in this action;

2. Declaring that the present districting scheme for electing

Texas district judges violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the Constitution, section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, and 42

U.S.C. § 1983;

3. Ordering defendants to develop and establish a scheme

for electing district judges that fully remedies the dilution of

plaintiff-intervenors voting strength and provides Black

voters with an equal opportunity to elect the candidates of

their choice;

23a

4. Granting plaintiff-intervenors their taxable costs in this

action, necessary expenses of the litigation, and reasonable

attorney’s fees; and

5. Providing such other relief as the Court finds just.

Respectfully submitted,

January 19, 1988

24a

[Caption]

COMPLAINT IN INTERVENTION

I. Introduction

1. Intervenors/plaintiffs Jesse Oliver, Fred Tinsley

and Joan Winn White ("Intervenors") are former state

district judges of Dallas County, and are Black citizens of

the State of Texas. They bring this action pursuant to 42

U.S.C. Section 1971, 1973, 1983 and 1988 to redress a

denial, under color of state law, of rights, privileges or

immunities secured to plaintiffs by the said laws and by the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States.

2. Plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment that the

existing at large scheme of electing district judges in Dallas

County of the State of Texas violates plaintiffs’ civil rights

in that such method illegally and/or unconstitutionally dilutes

the voting strength of Mexican-American and Black electors;

plaintiffs seek a permanent injunction prohibiting the calling,

holding, supervising or certifying any future elections for

25a

district judges under the present at large scheme in Dallas

County; plaintiffs seek the formation of a judicial districting

scheme by which district judges in the target counties are

elected from districts are single member districts; plaintiffs

seek costs and attorneys’ fees.

II. Jurisdiction

3. Jurisdiction is based upon 28 U.S.C. 1343(3) and

(4), upon causes of action arising from 42 U.S.C. Section

1971, 1973, 1983, and 1988, and under the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Declaratory relief is authorized by 28 U.S.C. Section 2201

and 2202 and by Rule 57, F.R.C.P.

III. Plaintiffs/Intervenors

4. Plaintiffs Jesse Oliver, Fred Tinsley and Joan

Winn White are Black citizens and registered voters of

Dallas County, Texas. They are qualified to vote for district

judges of Dallas County. Plaintiffs were appointed district

judges who lost an at large election to a white opponent in

Dallas County, Texas.

26a

IV. Defendants

5. Defendant William Clements is the Governor of

the State of Texas, and is the chief executive officer of the

state and as such is charged with the responsibility to execute

the laws of the state. Defendant Jim Mattox is the Attorney-

General of the State of Texas, and is the chief law

enforcement officer of the state and as such is charged with

the responsibility to enforce the laws of the state. Defendant

Jack Rains is the Secretary of State of the State of Texas,

and is the chief elections officer of the state and as such is

charged with the responsibility to administer the election

laws of the state. Defendants Thomas R. Phillips, John F.

Onion, Ron Chapman, Thomas J. Stovall, James F.

Clawson, Jr., Joe E. Kelly, Joe B. Evins, Sam M. Paxson,

Weldon Kirk, Charles J. Murray, Ray D. Anderson, and Joe

Spurlock, II are members of the Judicial Districts Board

created by Article V, Section 7a of the Texas Constitution,

and pursuant to Article 24.94Iff, Texas Revised Civil

Statutes, have the duty to reapportion judicial districts within

the State of Texas.

27a

V. Factual Allegations

6. District judges are elected either from judicial

districts which are coterminous with and wholly contained

within a county, or from judicial districts which may be

composed of several entire counties.

7. In those counties which contain more than one

judicial district, the present election system is an at large

scheme with the equivalent of numbered places, the majority

rule requirement, and staggered terms.

8. The following counties upon information and

belief, contain multiple judicial districts and a sufficiently

compact minority population for the drawing of at least one

majority combined minority single member district.

Harris Lubbock

Dallas Fort Bend

Ector Smith

McClennan Brazos

Tarrant Brazoria

Midland Taylor

Travis Wichita

Jefferson Angelina

Galveston Gregg

Bell

9. The above counties contain some 190 judicial

28a

districts, and a combined minority population of almost 30%;

however, only 10 or 5.3% of the 190 district judges are

minority.

10. The following counties contain multiple judicial

districts and sufficient Black population for the drawing of

at least one majority-Black single member district:

Harris Galveston

Dallas Smith

Tarrant Bell

Jefferson McClennan

Travis Gregg

Brazos Fort Bend

11. The above counties contain some 164 judicial

districts, and a Black population of 16.4%; however, only 7

or 4.3% of the 164 district judges are Black.

12. The following counties contain multiple judicial

districts and sufficient Hispanic population for the drawing

of at least one majority-hispanic single member district:

Harris Ector

Tarrant Lubbock

Galveston Fort Bend

Dallas

Travis

13. The above counties contain some 148 judicial

29a

districts, and a Hispanic population of 15.4%; however, only

4 or 2.7% of the 148 district judges are Hispanic.

14. The following judicial districts contain multiple

counties and sufficient minority population for the drawing

of at least one majority-minority single member districts:

Judicial District County

81st, 218th Atascosa, Frio, Karnes,

LaSalle & Wilson

36th 156th, 343rd Aransas, Bee, Live Oak,

McMullen & San Patricio

22nd, 207th Caldwell, Comal & Hays

24th, 135th, 267th Calhoun, DeWitt, Goliad,

Jackson, Refugio &

Victoria

64th, 242nd Castro, Hale & Swisher

34th, 205th, 210th Culberson, El Paso &

Hudspeth

15. The above counties contain some 15 judicial

districts, and a combined minority population of 44.32%;

however, only 1 or 6.7% of the 15 district judges is Black

or Hispanic.

16. The following judicial districts contain multiple

30a

counties and sufficient hispanic population for the drawing

of at least one majority-hispanic single member district:

Judicial District County

81st, 218th Atascosa, Frio, Karnes,

LaSalle & Wilson

36th, 156th, 343rd Aransas, Bee, Live Oak,

McMullen & San Patricio

24th, 135th, 267th Calhoun, DeWitt, Goliad,

Jackson, Refugio &

Victoria

64th, 242nd Castro, Hale & Swisher

34th, 205th, 210th Culberson, El Paso &

Hudspeth

17. The above counties contain some 13 judicial

districts, and a hispanic population of 42.77%; however,

only 1 or 7.7% of the 13 district judges is hispanic.

18. Upon information and belief, if single members

districts were drawn in the above named areas, the minority

group is sufficiently large and compact so that districts could

be drawn in which minorities would constitute a majority.

19. Upon information and believe, in the above

named areas minorities are politically cohesive.

31a

20. Upon information and belief in the above cited

areas, the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to

enable it -- in the absence of special circumstances, such as

the minority candidate running unopposed -- usually to defeat

the minority’s preferred candidate.

21. Upon information and belief, in the above

challenged areas, the at large election scheme interacts with

social and historical conditions to cause an in-equality in the

opportunity of hispanic or black voters to elect

representatives of their choice as compared to white voters.

22. Depending upon the evidence developed in

discovery, some of the above named areas may be deleted

and some unnamed areas may be added.

VI. Causes of Action

23. The present at large scheme of electing district

judges, intentionally created and/or maintained with a

discriminatory purpose, violates the civil rights of plaintiffs

by diluting their votes.

24. The present at large scheme of electing district

judges results in a denial or abridgement of the right to vote

32a

of the plaintiffs on account of their race or color in that the

political processes leading to nomination or election of

district judges are not equally open to participation by

plaintiffs in that they have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to elect candidates of their choice.

VII. Immunities

25. Qualified and absolute immunity do not protect

the defendants because plaintiffs seek only injunctive and

declaratory relief and attorneys’ fees. Furthermore, absolute

immunity does not protect defendants because they do not act

in any of the capacities which receive immunity at common

law. The defendants are not entitled to Eleventh

Amendment immunity because plaintiffs seek only injunctive

and declaratory relief and attorneys’ fees.

VIII. Equities

26. Plaintiffs have no adequate remedy at law other

than the judicial relief sought herein, and unless the

defendants are enjoined from continuing the present at large

scheme, plaintiffs will be irreparably harmed by the

continuing violation of their statutory and constitutional

33a

rights. The illegal and unconstitutional conditions

complained of preclude the adoption of remedial provisions

by the electorate. The present electoral scheme is without

any legitimate or compelling governmental interest and is

arbitrarily and capriciously cancels, dilutes and minimizes

the force and effect of the plaintiffs’ voting strength.

IX. Attorneys’ Fees

27. In accordance with 42 U.S.C. Section 1973-1(e)

and 1988, plaintiffs are entitled to recover reasonable

attorneys’ fees as part of their costs.

X. Prayer

28. WHEREFORE, premises considered, plaintiffs

pray that defendants be cited to appear and answer herein;

that a declaratory judgment be issued finding that the

existing method of electing district judges is unconstitutional

and/or illegal, null and void; that the defendants be

permanently enjoined from calling, holding, supervising or

certifying any further elections for district judges under the

present at large scheme; that the Court order that district

judges in the targeted counties be elected in a system which

34a

contains single member districts; adjudge all costs against

defendants, including reasonable attorneys’ fees; retain

jurisdiction to render any and all further orders that this

Court may from time to time deem appropriate; and grant

any and all further relief both at law and in equity to which

these plaintiffs may show themselves to be entitled.

Respectfully submitted,

35a

[Caption]

DEFENDANT HARRIS COUNTY DISTRICT JUDGE

SHAROLYN WOOD’S ORIGINAL ANSWER TO

HOUSTON LAWYERS’ ASSOCIATION

TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT:

COMES NOW Defendants Sharolyn Wood, Judge of the

127th Judicial District Court of Harris County, Texas

("Wood") and, subject to her Motion to Dismiss and Motion

for More Definite Statement, files this her Original Answer

in response to the Complaint in Intervention of the Houston

Lawyers’ Association, Alice Bonner ("Bonner"), Weldon

Berry ("Berry"), Francis Williams ("Williams"), Rev.

William Lawson ("Lawson"), Deloyd T. Parker ("Parker"),

and Bennie McGinty ("McGinty") (hereinafter collectively

referred to as the "Houston Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs")

in the above referenced cause of action as follows:

I.

BACKGROUND

1.1. This is a suit originally brought by the League of

Latin American Citizens ("LULAC") and certain individual

Mexican-American and black citizens of Texas seeking to

36a

declare illegal and/or unconstitutional and null and void in

certain targeted counties the State of Texas’ constitutionally

and legislatively mandated system of electing state district

judges at large.

1.2. The Texas Constitution Article V, § 7 provides

in relevant part that the state shall be divded into judicial

districts with each district having one or more judges as

provided by law or by the Texas Constitution. The section

also provides that each district judge shall be elected by the

qualified voters at a general election and shall be a citizen of

the state and shall have been a practicing lawyer in the state

or a judge of a state court for four years and shall have been

a resident of the district for two years and shall agree to

reside in the district during his term of office.

1.3. In 1985, the Texas Constitution was amended by

the addition of a new section, article V, § 7a, which

provides for the reapportionment of Texas judicial election

districts. That section provides that no judicial district may

be established smaller than an entire county except by

majority vote of the voters at a general election. Tex.

37a

Const, of 1876, art. V, § 7a(i).

1.4. Pursuant to article V, the Texas legislature has

enacted a comprehensive body of statutes governing the

formation and function of judicial districts. The policy

underlying the establishment of judicial districts is expressly

stated in those statutes, to wit:

It is the policy of the state that the administration

of justice shall be prompt and efficient and that, for this

purpose, the judicial districts of the state shall be

reapportioned as provided by this subchapter so that the

district courts of various judicial districts have judicial

burdens that are as nearly equal as possible.

Tex. Gov’t Code § 24.945.

1.5. To promote the ends of fairness and efficiency,

all the district courts in a county with more than one judicial

district are accorded concurrent jurisdiction and courts in

those districts are permitted to equalize their dockets. Tex.

Gov’t Code §§ 24.950, 24.951.

1.6. In addition, the Texas Government Code sets out

rules and conditions for the reapportionment of judicial

38a

districts.1

1

Those statutes expressly require that the

The Tex. Gov’t Code provides,

(a) The reapportionment of the judicial

districts of the state by the board is subject to the

rules and conditions provided by Subsections (b)-

(d).

(b) Reapportionment of the judicial

districts shall be made on a determination of fact

by the board that the reapportionment will best

promote the efficiency and promptness of the

administration of justice in the state by equalizing

as nearly as possible the judicial burdens of the

district courts of the various judicial districts. In

determining the reapportionment that best

promotes the efficiency and promptness of the

administration of justice, the board shall

consider:

(1) the numbers and types of

cases filed in the district courts of the

counties to be affected by the

reapportionment;

(2) the numbers of types of

cases disposed of by dismissal or

judgment in the district courts of those

counties;

(3) the numbers and types of

cases pending in the district courts of

those counties;

(4) the number of district

courts in those counties;

(5) the population of the

counties;

(6) the area to be covered by

39a

a judicial district; and

(7) the actual growth or decline

of population and district court case load

in the counties to be affected.

(c) Each judicial district affected by a

reapportionemnt must contain one or more

complete counties except as provided by this

section. More than one judicial district may

contain the same county or counties. If more

than one county is contained in a judicial district,

the territory of the judicial district must be

contiguous.

(d) Subject to the other rules and

conditions in this section, a judicial district in a

reapportionment under this subchapter may:

(1) be enlarged in territory by

including an additional county or counties

in the district, but a county having a

population as large or larger than the

population of the judicial district being

reapportioned may not be added to the

judicial district;

(2) be decreased in territory by

removing a county or counties from the

district;

(3) have both a county or

counties added to the district and a county

or counties removed from it; or

(4) be removed to another

location in the state so that the district

contains an entirely different county or

counties.

(e) The legislature, the Judicial Districts

40a

reapportionment of state judicial election districts be made on

that basis which "will best promote the efficiency and

promptness of the administration of justice in the state by

equalizing as nearly as possible the judicial burdens of the

district courts of the various judicial districts." The Code

further sets out the factors to be considered in determining

which reapportionment best promotes the efficiency and

promptness of the administration of justice.

1.7. Not only are both race and racial discrimination

entirely alien to Texas’ judicial district reapportionment

policy and the factors enumerated under it, but both the

statement of policy itself and the enumerated factors to be

considered make it absolutely clear that the fundamental state

Board, or the Legislative Redistricting Board may not

redistrict the judicial districts to provide for any judicial

district smaller in size than an entire county except as

provided by this subsection. Judicial districts smaller in

size than the entire county may be created subsequent to

a general election in which a majority of the persons

voting on the proposition adopt the proposition "to allow

the division o f ________ County into judicial districts

composed of parts of ________ County." A

redistricting plan may not be proposed or adopted by the

legislature, the Judicial Districts Board, or the

Legislative Redistricting Board in anticipation of a

future action by the voters of any county.

41a

policy that determines the apportionment of judicial districts

is the vitally important policy of promoting efficiency,

promptness, and fundamental fairness in the administration

of justice in Texas. Plaintiffs, however, would simply

disregard this compelling state policy in the interests of

increasing the numbers of protected minority class members

in the state judiciary. Indeed, Plaintiffs expressly state that

"the present electoral scheme is without any legitimate or

compelling governmental interest and it arbitrarily and

capriciously cancels, dilutes, and minimizes the force and

effect of the Plaintiffs’ voting strength." Plaintiffs’ First

Amended Complaint at f 31.

1.8. Despite their claim that the present judicial

election scheme is without any legitimate foundation,

Plaintiffs state no claim against Texas’ judicial election

scheme in general. Rather, they complain that Texas’ state

judicial districts were established and/or are maintained in

certain target counties with the intent to discriminate against

minorities protected by § 2 of the Voting Rights Act, and

that the district judge election scheme in those counties

42a

dilutes the votes of blacks and Hispanics and thereby violates

the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.A. §§ 1971 and 1973, the

Civil Rights Act, U.S.C. §§ 1983 and 1988, and the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the United States

Constitution. Plaintiffs’ Complaint is essentially that when

the target counties, which are widely scattered over the State

of Texas, are considered as an aggregate, the proportional

representation of black and/or Hispanic judges in those

counties is less than the proportion of minorities in the gross

population of those aggregated counties.

1.9. This suit initially challenged the judicial election

system in 47 Texas counties.2 By agreement between

Plaintiffs and the State of Texas, approved by the Court on

oral motion of the parties at a hearing on various motions to

intervene on February 27, 1989, the number of targeted

The counties targeted initially were Harris,

Dallas, Ector, McLennan, Tarrant, Midland, Travis,

Jefferson, Galveston, Bell, Lubbock, Fort Bend, Brazos,

Brazoria, Taylor, Wichita, Angelina, Gregg, Smith,

Atascosa, Frio, Karnes, LaSalle, Wilson, Aransas, Bee, Live

Oak, McMullen, San Patricio, Caldwell, Comal, Hays,

Calhoun, DeWitt, Goliad, Jackson, Refugio, Victoria,

Castro, Hale, Swisher, Culberson, El Paso, and Hudspeth.

43a

counties was reduced to 15. These counties are Harris,

Dallas, Ector, McLennan, Tarrant, Midland, Travis,

Jefferson, Galveston, Lubbock, Fort Bend, Smith,

Culberson, El Paso, and Hudspeth.

II.

DEFENSES

2.1. Defendant Wood is without knowledge as to

whether the individual Houston Lawyers’ Association

Plaintiffs are black registered voters as alleged in paragraph

1 of the Houston Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint

in Intervention (the "Houston Lawyers’ Association

Plaintiffs’ Complaint") and, therefore, denies the same.

2.2. Defendant Wood specifically denies all other

allegations in paragraph 1 of the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint. In particular, she denies

that the at large judicial electoral districts scheme as

currently constituted denies black citizens an equal

opportunity to elect the candidates of their choice in Harris

County. She also specifically denies that Art. 5, § 7a(i) of

the Texas Constitution was adopted with the intention, or has

44a

been maintained for the purpose of, minimizing the voting

strength of black voters.

2.3. Defendant Wood admits that this Court has

jurisdiction over this case under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and

1343. However, she denies that the Court has jurisdiction

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1973j(f), since that section provides

jurisdiction only over causes of action brought under § 1973j

to impose civil and criminal penalties on persons who violate

various voting rights statutes, and Plaintiffs have not brought

any action under § 1973j nor does § 1973j provide for any

private cause of action.

2.4. Defendant Wood is without information sufficient

to form a belief as to the characterization of the Houston

Lawyers’ Association in paragraph 4 of Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiff’s Complaint and the race and status of

the individual Houston Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs as

alleged in paragraph 5 through 10 and therefore denies them.

2.5. Defendant Clements has been dropped from this

suit by Court order.

2.6. Defendant Wood is without knowledge or

45a

information sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of the

averments in paragraphs 11 through 14 of Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint, except to the extent that

those averments are admitted by the State Defendants.

Defendant Wood denies, however, that the Judicial Districts

Board may reapportion the judicial districts of Texas "as the

necessity arises in its judgment" without regard to any other

factors.

2.7. Defendant Wood makes no averments except

with respect to Harris County. Insofar as Harris County is

concerned, Defendant Wood is without knowledge or

information sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of the

averments in paragraphs 15 through 35 of the Complaint to

which a responsive pleading may be required and therefore

denies them.

2.8. In addition, in response to paragraph 20 of the

Complaint, Defendant Wood specifically denies that elections

in Harris County in particular are characterized by

significant racial bloc voting.

2.9. Defendant Wood also specifically denies that the

46a

State of Texas has used or continues to use unusually large

election districts in Harris County; and she denies the

implication in paragraph 21 of the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint that the size of the judicial

election districts in Harris County is in any way determined

or influenced by the number of minority voters in the area.

2.10. Defendant Wood also specifically denies the

allegations in paragraph 22 of the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint that the judicial election

process is not equally open to blacks, insofar as those

allegations refer to Harris County.

2.11. Defendant Wood further specifically denies the

allegations in paragraph 35 of the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint that black judicial

candidates in Harris County are usually defeated by a bloc

voting white majority.

2.12. Defendant Wood denies the allegations

incorporated by reference in paragraph 36 of the Houston

Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint insofar as a

responsive pleading is required; and she refers the Houston

47a

Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs to her First Amended

Answer to Plaintiffs’ First Amended Complaint.

2.13. Defendant Wood admits the allegations in

paragraph 37 of the Houston Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs’

Complaint that Art. 5, § 7 of the Texas Constitution of 1876

was amended in 1985 to include § 7(a), but she denies that

the snippet quoted is meaningful by itself.

2.14. Defendant Wood admits the averments in

paragraph 38 insofar as any responsive pleading is required.

2.15. Defendant Wood is without information to permit

her to respond to the allegations in paragraphs 39 and 41 and

therfore denies them.

2.16. In response to paragraphs 40 and 42 of the

Complaint, and with respect to Harris County alone,

Defendant Wood specifically denies that the present at large

scheme of electing district judges violates the civil rights of

the Plaintiffs by diluting their votes. She further denies that

the present at large election scheme results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of the Plaintiffs to vote on account

of their race or color in that they have less opportunity than

48a

other members of the electorate to elect candidates of their

choice as alleged in paragraphs 22 and 48 of Houston

Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint. Intervenor

Wood asserts that such condition or effect does not exist in

Harris County with respect to the election of district judges.

She also asserts that no violation of the Voting Rights Act or

of the United States Constitution has occurred within Harris

County with respect to the current method or scheme of

electing district judges and that, therefore, no remedy is

required or justified in order to alleviate a problem which

does not exist within this county.

2.17. No responsive pleading is required to the

Houston Lawyers’ Association Plaintiffs’ allegations

regarding intervention in paragraphs 43 and 44 of their

Complaint.

2.18. Defendant Wood denies the allegations in

paragraphs 45 through 48 of the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ Complaint. She specifically denies in

addition, and with respect to Harris County alone, that the

present districting scheme was adopted or has been

49a

maintained with the intention of minimizing the political

strength of black voters, as alleged in paragraph 46; and she

specifically denies that the present scheme has the result of

making the political process in Harris County less open to

black voters.

II.

AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSES

A. Plaintiffs Lack Standing to Bring Their Claims (a) in

Twelve of the Fifteen Target Counties and (b) in Each

Already Identified Future Minority District in Which No

Plaintiff Resides.

3.1. Defendant Wood hereby incorporates by

reference the allegations heretofore made in paragraphs 1.1

through 2.18 as though fully restated.

3.2. Defendant Wood still urging and relying on the

matters herein alleged, further alleges by way of affirmative

defense that Plaintiffs lack standing to bring their claims of

vote dilution in twelve of the fifteen counties which are

targets of this suit in that no individual Plaintiff in this suit

is a resident of any county except Harris, Midland, and

Dallas. Thus, no decision of the Court regarding the

50a

application of Texas’ judicial district election scheme in any

other county will affect any Plaintiff in this case. When no

Plaintiffs will be affected by a decision regarding a claim,

the Court lacks jurisdiction over that claim. Hence all

claims as to the twelve unrepresented counties should be

dismissed and the remaining case severed by county and

transferred to the Federal District Court in such county.

3.3. In the alternative, the Court should join as

indispensable parties individual voters in each target county

as well as the district judges of those counties.

3.4. In addition, with respect to each of the eleven

proposed judicial districts Plaintiffs have already identified

in which no named Plaintiff is a resident, Plaintiffs lack

standing to assert any claims.

B. State Judicial Elections Are Beyond the Scope o f the

Voting Rights Act.

4.1. Defendant Wood hereby incorporates by

reference the allegations heretofore made in paragraphs 1.1

through 3.4 as though fully restated.

4.2. Defendant Wood, still urging and relying on the

51a

matters herein alleged, further alleges by way of affirmative

defense that state judicial elections are beyond the scope of

the Voting Rights Act in that the plain language of § 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, as amended in 1982 and codified at 42

U.S.C. § 1973(b), limits the scope of the Act to elections of

"representatives," not judges; and she alleges that the Voting

Rights Act cannot be properly understood to require that

judges, who serve the people rather than represent them,

must be elected from single member districts drawn on racial

lines, as Plaintiffs would require, in order to correct for the

dilution of the votes of protected minority class members in

multi-member judicial districts.

C. The Voting Rights Act, as Amended, is Unconstitutional

as Applied to Judicial Elections.

5.1. Defendant Wood hereby incorporates by

reference the allegations heretofore made in paragraphs 1.1

through 4.2 as though fully restated.

5.2. Defendant Wood, still urging and relying on the

matters herein alleged, would further alleges by way of

affirmative defense that the Voting Rights Act, as amended

52a

in 1982, is unconstitutional as applied to judicial elections.

5.3. Intentional discrimination is an essential element

of a violation of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to

the United States Constitution. The Voting Rights Act

derives its constitutional validity from those two amendments

and, in particular, from § 5 of the fourteenth amendment and

§ 2 of the fifteenth amendment, which grant to Congress the

power to enforce the provisions of those amendments.

Following a holding by the Supreme Court that the Voting

Rights Act was violated only by purposeful discrimination,

Congress amended § 2 of the Voting Rights Act to make it

clear that a violation could be proved by showing

discriminatory effect alone without showing a discriminatory

purpose on the part of the state in adopting or maintaining a

contested electoral mechanism.

5.4. The 1982 amendments to § 2 of the Voting

Rights Act transgress the constitutional limitations within

which Congress has the authority to interfere with state

regulation of the local electoral process. Although Congress

has the power under the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments

53a

to pass statutes prohibiting conduct which does not rise to

the level of a constitutional violation, it may not infringe any

provision of the Constitution in doing so. Yet the Voting

Rights Act, at least as applied to judicial elections, violates

the principle of separation of powers underlying the United

States and the Texas Constitution and the Equal Protection

Clause of the fourteenth amendment in order to extend

protections to protected minorities which are not themselves

required by the Constitution.

5.5. The Equal Protection Clause of the fourteenth

amendment to the United States Constitution provides that

"[n]o State shall . . . deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." The Voting

Rights Act, as amended in 1982, is, however, expressly

designed to force states to adopt measures as remedies for

alleged vote dilution that favor protected classes over other

classes ad thus deprive members of nonprotected classes of

the equal protection of the laws. Since Defendant Wood is

not a member of a class protected by the Act, that Act, used

to force the restructuring of state judicial election districts in

54a

Harris County, Texas, would unconstitutionally deprive

Defendant Wood of the equal protection of the laws.

5.6. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

originally promulgated and enforced prior to 1982, did not

expressly favor protected classes. The Act simply forbade

any state or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right

of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race

or color. In 1975, the Act was amended to extend its

protections to members of language minority groups.3 In

1982 it was amended once again; and this time its

protections were expressly limited to "members of a

protected class."4

As amended in 1975, the § 2 of the Voting

Rights Act provided:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any

citizen of the United States to vote on account of

race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this

title [i.e., guarantees protecting language

minority groups].

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended

in 1982, provides:

55a

5.7. Since the protections of § 2 of the Voting Rights

Act as amended in 1982 are expressly extended to protected

classes and not to others, the Voting Rights Act as amended

is a race-based Act designed to further remedial goals.

Therefore, its provisions are highly suspect and are to be

treated by the courts with strict scrutiny so that they may

(a) No voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or

procedure shall be imposed or applied by any

State or political subdivision in a manner which

results in a denial or abridgement of the right of

any citizen of the United States to vote on

account of race or color, or in contravention of

the guarantees set forth in section 1973b (f)(2) of

this title, as provided in subsection (b) of this

section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of

this section is established if, based on the totality

of circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the

State or political subdivision are not equally open

to participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the

political process and to elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided, That

nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of protected class elected in numbers

equal to their proportion in the population.

56a

determine whether its classifications are in fact motivated by

racial politics, rather than by a more benign purpose, and

whether those classifications carry the danger of leading to

a politics of racial hostility.

5.8. Strict scrutiny reveals that the protections of § 2

of the Voting Rights Act, as amended can be invoked in a

vote dilution case, such as the present case, only by a

protected minority which is geographically insular and

politically cohesive and votes as a racial block against a

white majority, which also votes as a racial block and

usually manages to defeat candidates preferred by the

protected minority. In that situation — and in that situation

only — the Voting Rights Act comes alive to ensure that the

protected class will be allowed to elect the representatives of

its choice, even if that protected class is in the minority in

the challenged election district, and even if the challenge

district’s boundaries have been drawn for compelling state

reasons having nothing to do with race. However, the

Voting Rights Act does not protect the rights of any class of

people other than those designated by the Act as protected

57a

classes - even if the unprotected class finds itself in the

precise circumstances which would invoke the Act if the

class were protected, namely, in a situation where the

unprotected class constitutes a minority of voters within a

given election district - a situation which, on information

and belief, prevails in much of Southern Texas.

5.9. Defendant Wood makes no allegations concerning

the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act in regard to

matters other than judicial elections. However, in regard to

judicial elections, Section 2 as amended is a preferential Act

which, in the name of preventing discrimination, (a) is

actually a device for encouraging and rewarding racial

politics and implicitly the notion of race-conscious justice by

forcing states to adopt measures to remedy "vote dilution"

and (b) by ignoring the principal of "one man-one vote," to

guarantee a disproportionally large number of minority

judges committed to race-conscious justice. Both concepts

would deprive nonprotected classes of the equal protection of

the law. That Act therefore fails to meet the test of strict

scrutiny and flagrantly violates the equal protection clause of

58a

the Constitution.

5.10. Second, the Voting Rights Act, when extended

to judicial elections, obliterates the distinction between

legislators -- who represent the people and are properly

representatives of the voters’ personal interests (such as the

voters’ desire to have the interests of their racial or language

group put foremost) — and judges — who serve the interests

of all the people impartially and in the proper exercise of

whose function the desires of the voters to promote racial

identification have no proper role at all. When the Voting

Rights Act is applied to judges, the proper distinction

between the legislative and judicial function is sacrificed to

the promotion of racial interests and any state in which it is

so used is denied the opportunity to maintain the separation

of the legislative and judicial function which is fundamental

to the United States Constitution itself and to all state

constitutions, including the Texas Constitution.

WHEREFORE, Harris County District Judge Sharolyn

Wood respectfully requests that the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs’ cause of action be dismissed with

59a

respect to the system for electing district judges within

Harris County and that judgment be entered in her favor and

that she recover all other relief, both general and special, in

law and in equity, to which she may show herself justly

entitled.

III.

DEFENDANT WOOD’S COUNTERCLAIM

Harris County District Judge Sharolyn Wood, Defendant

in the above-captioned action, now acting as and designated

Counter-Plaintiff, complains of the Houston Lawyers’

Association Plaintiffs, now designated Counter-Defendants,

and for cause of action would show by way of counterclaim

the following:

6.1. Counter-Plaintiff incorporates by reference the

allegations in paragraphs 1.1 through 5.10 as though fully

restated.

6.2. In connection with the controversy which is the

subject of this cause of action, Counter-Defendants rely

integrally on the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 as amended in 1982 and codified at 42 U.S.C.A. §

60a

1973 (West Supp. 1988). Title 28 §§ 2201 and 2202 permit

any interested party to seek a declaration of his rights and

other legal relations in a case of actual controversy within its

jurisdiction and to seek further necessary or proper relief

based on a declaratory judgment. Therefore Counter-

Plaintiff seeks a declaration of her rights vis-a-vis the

amended Voting Rights Act under the United States

Constitution.

6.3. For the reasons set forth above in paragraphs 4.1

through 4.2 and hereby incorporated by reference, Counter-

Plaintiff alleges that state judicial elections are beyond the

scope of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

6.4. Alternatively, and still urging and relying upon

the claim set forth herein, Counter-Plaintiff further alleges

that, for the reasons set forth in paragraphs 5.1 through 5.10

and hereby incorporated by reference, the Voting Rights Act

as amended in 1982 is uncosntitutional as applied to judicial

elections. It deprives non-protected classes of the equal

protection of the law, in violation of the fourteenth

amendment; and in addition, it deprives citizens of those

61a

states in which it is invoked to force the redistricting of state

judicial election districts of their right to a form of

government in which the function of the judiciary as servants

of the people is kept separate from the function of the

legislature as representatives of the people. More

specifically, its application in the ways sought by Plaintiffs

would deprive Defendant Wood of her constitutional rights.

6.5. In that she seeks a declaration of her

constitutional rights, Defendant Wood alleges that she is

entitled to court costs and attorney’s fees.

WHEREFORE, Counter-Plaintiff Wood respectfully

prays that the Court will grant her relief as follows:

1. Declare that the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended in 1982, does not apply to judicial elections; or,

alternatively,

2. Declare that the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended in 1982, is unconstitutional as applied to judicial

elections; and

3. Dismiss all of Plaintiffs’ claims; and

4. Award Counter-Plaintiff her just costs and

62a

attorney’s fees pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2202 and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988; and

5. Award Counter-Plaintiff such other and further

relief in law and in equity to which she may show herself to

be justly entitled.

Respectfully submitted,

PORTER & CLEMENTS

By: A/ J. Eugene Clements

[Caption]

63a

HARRIS COUNTY DISTRICT JUDGE SHAROLYN

WOOD’S FIRST AMENDED ORIGINAL ANSWER

AND COUNTERCLAIM TO PLAINTIFFS

LULAC, ETAL.

TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT:

COMES NOW Sharolyn Wood, Judge of the 127th

Judicial District Court of Harris County, Texas ("Wood")

and, subject to her Motion to Dismiss and Motion for More

Definite Statement, files this her First Amended Original

Answer in response to the Plaintiffs’ First Amended

Complaint in the above-referenced cause of action as

follows:

I.

BACKGROUND

1.1. This is a suit originally brought by the League

of Latin American Citizens ("LULAC") and certain

individual Mexican-American and black citizens of Texas

seeking to declare illegal and/or unconstitutional and null and

void in certain targeted counties the State of Texas’

constitutionally and legislatively mandated system of electing

state district judges at large.

64a

1.2. The Texas Constitution Article V, § 7 provides

in relevant part that the state shall be divided into judicial

districts with each district having one or more judges as

provided by law or by the Texas Constitution. The section

also provides that each district judge shall be elected by the

qualified voters at a general election and shall be a citizen of

the state and shall have been a practicing lawyer in the state

or a judge of a state court for four years and shall have been

a resident of the district for two years and shall agree to

reside in the district during his term of office.

1.3. In 1985, the Texas Constitution was amended by

the addition of a new section, article V, § 7a, which

provides for the reapportionment of Texas judicial election

districts. That section provides that no judicial district may

be established smaller than an entire county except by

majority vote of the voters at a general election. Tex.

Const, of 1876, art. V, § 7a(i).

1.4. Pursuant to article V, the Texas legislature has

enacted a comprehensive body of statutes governing the

formation and function of judicial districts. The policy

underlying the establishment of judicial districts is expressly

stated in those statutes, to wit:

It is the policy of the state that the administration

of justice shall be prompt and efficient and that, for this

purpose, the judicial districts of the state shall be

reapportioned as provided by this subchapter so that the

district courts of various judicial districts have judicial

burdens that are as nearly equal as possible.

Tex. Gov’t Code § 24.945.

1.5. To promote the ends of fairness and efficiency,

all the district courts in a county with more than one judicial

district are accorded concurrent jurisdiction and courts in

those districts are permitted to equalize their dockets. Tex.

Gov’t Code §§ 24.950, 24.951.

1.6. In addition, the Texas Government Code sets out

rules and conditions for the reapportionment of judicial

districts.1 Those statutes expressly require that the

The Tex. Gov’t Code provides,

(a) The reapportionment of the judicial

districts of the state by the board is subject to the

rules and conditions provided by Subsection (b)-

(d).

(b) Reapportionment of the judicial

districts shall be made on a determination of fact

by the board that the reapportionment will best

66a

promote the efficiency and promptness of the

administration of justice in the state by equalizing

as nearly as possible the judicial burdens of the

district courts of the various judicial districts. In