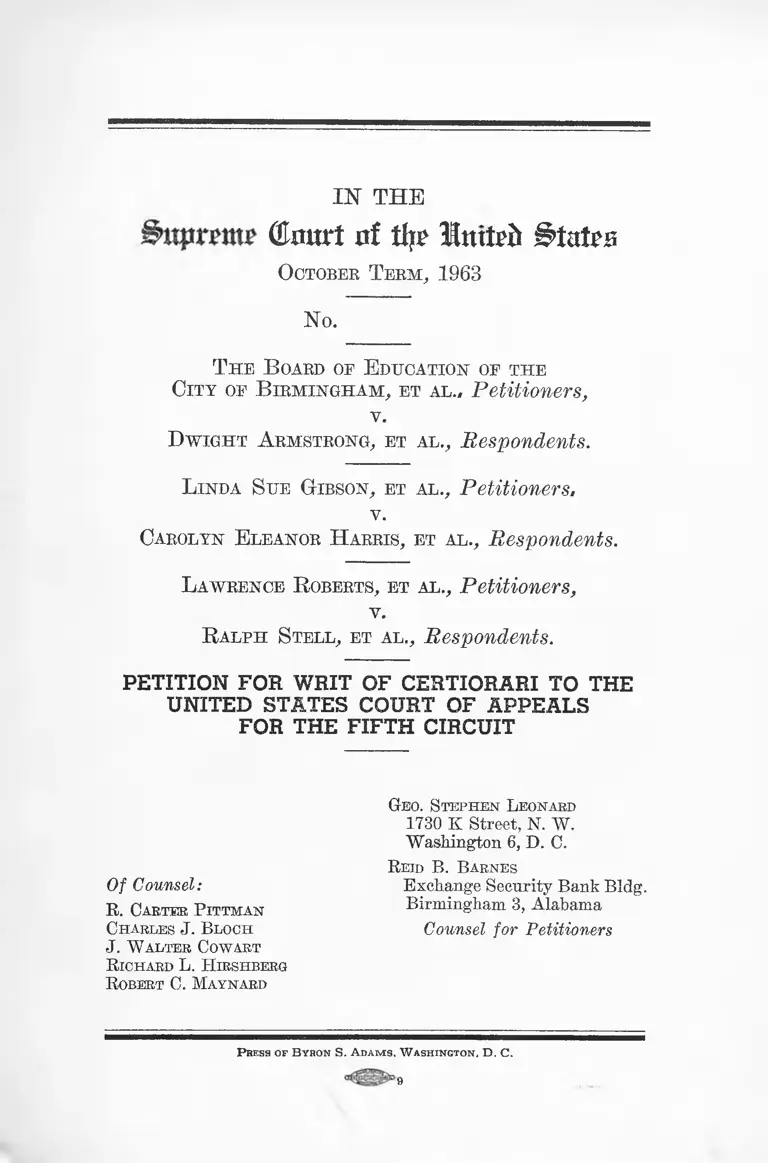

Board of Education of the City of Birmingham v. Armstrong Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

September 6, 1963

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Education of the City of Birmingham v. Armstrong Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1963. 8d05dce4-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/624b4842-cfab-43ed-b9bc-37a61bb6cba5/board-of-education-of-the-city-of-birmingham-v-armstrong-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Olmtrt td tty? Untieft States

October T erm ,, 1963

Ho.

T h e B oard of E ducation of the

City of B irm ingha m , et al., Petitioners,

v.

D w ight A rmstrong, et al., Respondents.

L inda S ue G ibson, et al., Petitioners.

Y.

Carolyn E leanor H arris, et al., Respondents.

L awrence R oberts, et al., Petitioners,

v.

R alph S tell, et al., Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Geo. Steph en L eonard

1730 K Street, N. W.

Washington 6, D. C.

R eid B. Barnes

Of Counsel: Exchange Security Bank Bldg.

R. Carter P ittman Birmingham 3, Alabama

Charles J. Bloch Counsel for Petitioners

J. W alter Cowart

R ichard L. H irshberg

R obert C. Maynard

P ress o f B yro n S . A d a m s , W a s h in g t o n , D . C .

9

INDEX

Opinions B elo w .............................................

Jurisdiction ...................................................

Question Presented .....................................

Statutes Involved .........................................

Statement of the C a se s ...............................

Reasons Relied on For Allowance of W rit

Argument .......................................................

13

14

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C ases :

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958 ).............. 20

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958 )........• • • 20

American Lead Pencil v. Schneegass, 178 Fed. 735

(N.D. Ga. 1910) ............................................. . ••• .17,3.8

Bergen Drug v. Parke Davis Co., 307 F. 2d 72o (3rd

Cir. 1962) .....................................................• ••••••• 16

Clune v. Publishers Association of New York City, 214

F. Supp. 520 (S.D.N.Y. 1963) ................................. 17

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............ • - • 20

DeBeers Mines v. United States, 325 U.S. 212 (194o). .16, 2o

Dennis v. United .States, 341 U.S. 494 (19ol) .............. 25

Dunn v. Retail Clerks International Association, 299

F. 2d 873 (6th Cir. 1962) ......................................... 21

Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of South Caro-

lina, 208 F. Supp. 416 (W.D. So. Car. 1962) ---- 17,18

Greene v. Fair, 314 F. 2d 200 (5th Cir. 1963) . . . . . . . . 22-o

Hamilton Watch Co. v. Benrns Watch Co., 206 F. 2d

738 (2d Cir. 1953) .....................................................

Hess v. Woods, 185 F. 2d 404 (9th Cir. 1950) . . . . . . . 21-2

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U,S. 123 (1951) ................................................. 24-5

In re Lennon, 166 ILS. 548 (1897) ........................... • • •

Mack v. General Motors Corp., 260 F. 2d 886 (7th Cir

1958) ......................... .................................................. 17-8

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 341 (5th Cir. 1962) .......... 22

11 Index Continued

Page

Miami Beach Federal Say. & Loan Assoc, v. Callander,

256 F. 2d 410 (5th Cir. 1958) ..............................17, 23-4

Northern Securities Co. v. United States, 193 U.S. 197

(1904) ........................................................................... 24

Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266 (1948) .......................... 15

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

358 U.S. 101 (1958) ................................................. 9

Tanner Motor Livery, Ltd. v. Avis, Inc., 316 F. 2d 804

(9th Cir. 1963) .................................................. 17

Toledo, A.A. & N.M. Ry. Co. v. Pennsylvania Co., 54

Fed. 730 (N.D. Ohio 1893) ........................................ 16

Toledo Scale Co. v. Computing Scale Co., 261 U.S. 399

(1923) ............................................................................6,20

United States v. A dler’s Creamery, 107 F. 2d 987 (2d

Cir. 1939) ....................................................................17,18

United States v. Hayman, 342 U.S. 205 (1952) ............ 15

United States v. Morgan, 346 U.S. 502 (1954) ............ 15

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) . .19-20

W arner Bros. v. Gittone, 110 F. 2d 292 (3d Cir. 1940). .17,18

Westinghouse Electric Corp. v. Free Sewing Machine

Co., 256 F. 2d 806 (7th Cir. 1958) ......................... 18

Willheim v. Investors Diversified Services, Inc., 303

F. 2d 276 (2d Cir. 1962) ........................................... 17,18

Willheim v. Murchison, 203 F. Supp. 478 (S.D.N.Y.

1962) ............................................. 17

Winton Motor Carriage Co. v. Curtis Publishing Co.,

196 Fed. 906 (E.D. Pa. 1912) ................................... 17

S t a t u t e s :

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1)

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ..

28 U.S.C. § 1292 ..

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ..

28 U.S.C. § 1651 ..

28 U.S.C. § 2101(e)

28 U.S.C. § 2106

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ..

M iscella n eo u s :

A.L.R. 2d, vol. 15, p. 213, 234 ................................... 16

Am. Jur., vol. 28, “ Injunctions”, § 1 7 ...................... 16

Pomeroy’s Equity Jurisprudence (4th ed. 1919), vol.

4, §§ 1337,1359 ................................................... 16

............ 3

....12,18, 20

...4,12,18-9

............ 4

4-5,15,18, 23

....... 2

............ 5

............ 5

Ill

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Op in io n s of C ourts B elow

U n it e d S tates C ourt of A ppea ls

F if t h Cir c u it

Page

Ralph Stell et al. v. Savannah-Chatham County Board

of Education et al., 318 F. 2d 425 (1963) .............. la

Birdie Mae Davis et al. v. Board of School Commis

sioners, 322 F. 2d 356 (1963) ................................. 6a

Dwight Armstrong et al. v. The Board of Education of

the >City of Birmingham, Jefferson County, Ala

bama, et al., 323 F. 2d 333 (1963) .......................... 19a

Carolyn Eleanor H arris et al. v. Linda Sue Gibson et

al. and Glynn County Board of Education et al.,

322 F. 2d 780 (1963) ................................................. 79a

DISTRICT COURTS

Ralph Stell et al. v. Savannah-Chatham County Board

of Education, U.S.D.C. Southern District of

Georgia, Savannah Division (1963) (unreported) . 82a

Birdie Mae Davis et al. v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, Alabama, et al., 219 F.

Supp. 542 (U.S.D.C. Southern District, Alabama,

S.D., 1963) ................................................................... 91a

Dwight Armstrong et al. v. The Board of Education of

the City of Birmingham, Jefferson County, Ala

bama, et al., 220 F. Supp. 217 (U.S.D.C. Northern

District, Alabama, S.D., 1963) ............................... 99a

Linda Sue Gibson et al. v. Glynn County Board of Edu

cation, U..S.D.C. Southern District of Georgia,

Brunswick Division (1963) (unreported) ...............109a

IN THE

(tart nf % Itmti'ft #tatai

Ootobek T erm, 1963

Ho.

T h e B oard of E ducation of the

City of B irm ingham , et al.. Petitioners,

y.

D w ight A rmstrong, et al., Respondents.

L inda S ue Hibson, et al., Petitioners,

Y.

Carolyn E leanor H arris, et al., Respondents.

L awrence R oberts, et al., Petitioners,

v.

R alph S tell, et al., Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

To The Honorable, The Chief Justice and Associate

Justices of The Supreme Court of The United

States:

Each of your petitioners was a prevailing party in

a District Court action and is now an appellee in an

appeal therefrom pending before the Eifth Circuit

Court of Appeals. In each appeal, pending any hear

ing on the merits, the Circuit Court has issued an orig-

2

inal mandatory injunction which, has de facto reversed

the order or judgment appealed from by awarding as

against each of your petitioners, the affirmative relief

to which the respective respondents had failed to sus

tain their right in the trial court. Petitioners, con

tending that the form of such orders constitutes an

impermissible departure from normal appellate proc

esses, pray the issuance of a writ of certiorari directed

to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit limited to the question of the formal validity

of such orders as an allowable or proper exercise of

appellate judicial power.

The prayer is made for joint consideration of all

four1 cases under Rule 23(5) on the ground that the

four orders in question are substantially identical,

present the same issue of law and may constitute the

entire class of such orders since your petitioners know

of no similar rulings by any other Court of Appeals.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions of the Court of Appeals are printed

in the appendix and have been reported as follows:

St ell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (May 24, 1963) ; Davis v. Board of

School Commissioners of Mobile County, Ala., 322 F.

2d 356 (July 9, 1963) ; Armstrong v. Board of Educa-

1 In addition to the three captioned cases, a motion to he per

mitted to file an application for rehearing limited to the form of

the order concerned is filed herewith in Board of School Commrs.

of Mobile, et al. v. Birdie Mae Davis, et al., Oct. Term, 1963, No.

348, cert. den. 375 U.S. 894 (Oct. 28, 1963). The inclusion of the

Davis case is solely to have before the Court on a single applica

tion, the four related cases in which such appellate orders have

been issued.

3

tion of City of Birmingham, Ala., 323 F. 2d 333 ( July

12, 1963); and Harris v. Gibson and Glynn County

Board of Education, 322 F. 2d 780 (September 12,

1963).

The opinions of the District Courts are not sought

to be reviewed herein but are included in the appendix

for the Court’s reference. Two have been officially

reported, Davis v. Board of School Commissioners,

219 F. Supp. 542 (S.D. Ala. June 24, 1963) and Arm

strong v. Board of Education, 220 F. Supp. 217 (N.D.

Ala,, May 28, 1963). At the time of the issuance of

the order of the Fifth Circuit in Stell v. Savannah-

Chatham County Board of Education, only the pre

liminary findings given in the appendix had been

issued. The District Court’s decision, as thereafter

entered with the Clerk, is reported at 220 F. Supp.

667 (S.D. Ga. 1963).

The denial of the application for issuance of a writ

of certiorari in Davis is reported at 375 TT.S. 894 (Oc

tober 28, 1963).

JURISDICTION

The review authority of this Court prior to the

rendition of a judgment or decree by a Court of Ap

peals is conferred by 28 IT .8.0. § 1254(1) ; and since

each case is now so pending in that Court, this appli

cation comes within the time limited by 28 TJ.S.C.

§ 2101(e). The dates of the issuance of the orders

sought to be reviewed are as given in the preceding

section.

4

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does a Court of Appeals have power, pending its

determination of an appeal on the merits, to issue an

original mandatory injunction which

(a) reverses the appealed-from order or judgment

of the District Court by granting the affirmative

relief prayed by the unsuccessful parties in the

trial court;

(b) alters both the status quo ante litem and the

status quo as of the time the appeal was taken;

and

(c) directs the trial court to sign and issue as its

own the interim reversal of its earlier order ?

STATUTES INVOLVED

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1). Interlocutory Decisions.

“ (a) The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction

of appeals from:

(1) Interlocutory orders of the district cotirts

of the United 'States, the United States District

Court for the District of the Canal Zone, the

District Court of Guam, and the District Court

of the Virgin Islands, or of the judges thereof,

granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or dis

solving injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or

modify injunctions, except where a direct review

may he had in the Supreme Court;” (As am. Oct.

31, 1951, c. 655, §49, 65 Stat. 726; July 7, 1958,

Pub. L. 85-508, § 12(e), 72 Stat. 348; Sept. 2,1958,

Pub. L. 85-919, 72 Stat. 1770)

28 U.S.C. § 1651(a). Writs.

“ (a) The Supreme Court and all courts established

by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or

appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions

5

and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.”

(June 25, 1948, c. 646, 62 Stat. 944, amended May 24,

1949, c. 139, § 90, 63 Stat. 102).

28 U.S.C. § 2106. Review: Determination,

“ The Supreme Court or any other court of appel

late jurisdiction may affirm, modify, vacate, set aside

or reverse any judgment, decree, or order of a court

lawfully brought before it for review, and may remand

the cause and direct the entry of such appropriate

judgment, decree, or order, or require such further

proceedings to be had as may be just under the cir

cumstances.” (June 25, 1948, c. 646, 62 Stat. 963).

STATEMENT OF THE CASES

A number of facts are common to all cases. Each

of the four is a school desegregation case—Savannah

and Brunswick, Georgia, and Birmingham and Mobile,

Alabama—brought as a suit in equity under 28 TJ.S.C.

1343(3). The jurisdiction of the District Courts has

been invoked under the “ due process” and “ equal pro

tection” clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution as implemented by the Civil Rights Act,

(42 TJ.S.C. § 1983). The respondents have had in each

case the same or associated counsel and have asked

the same type of relief, resulting in substantial simi

larity in their pleadings and motions both in the Dis

trict Courts and in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit.

In each trial court the respondents’ pleadings have

prayed a permanent injunction directing some form

or plan of desegregation and respondents have asked

the same relief by way of preliminary injunction. In

each ease, the District Court concerned has issued a

6

judgment or order which respondents have appealed

to the Court of Appeals as constituting a denial of the

injunctive relief so demanded.

On taking each appeal, respondents have prayed an

original appellate interlocutory injunction for the

same affirmative relief as had been denied by the lower

court. The ground stated by respondents has been

that the clear absence of legal merit in the rulings of

the District Courts makes any delay in granting them

final relief, an irreparable injury. The Court of Ap

peals on each appeal has agreed with respondents and,

acting on an accelerated basis2 without a record or a

transcript of the proceedings below, has reversed the

lower court by granting the application for appellate

injunctive relief substantially as requested. On each

appeal, the Circuit has issued its mandate in the form

of an order to be signed and issued as that of the

District Court from which the earlier order not yet

determined on appeal, had issued.3

In somewhat greater detail, the nature of the pro

ceedings and character of the orders issued by the trial

and appellate courts are here given in the chrono

logical order of the cases.

(a) Savannah-Chatham Board of Education, et al v.

Ralph Stell, et al. (5th Cir. Ct. of App. No. 20557)

This action was brought on behalf of negro school

children in Savannah alleging injury caused by sep

arate schools and praying preliminary and permanent

injunctive relief requiring the defendant School Board

2 From application through hearing to decision, Stell, 4 days;

Davis, 8 days; Armstrong, 39 days; Gibson, 2 days.

3 Although the Fifth Circuit in the later Davis, Armstrong- and

Gibson opinions refers to' Stell as authority for the form of injunc

tion in question, Judge Cameron identifies an unpublished order

two days earlier as being the first. (App. pp. 60-4a)

7

of Savannah-Chatham County to submit a plan to re

organize the school system into what plaintiffs de

scribed as a “ unitary nonracial system”. At the trial,

proof was made on defense that the plan proposed by

respondents would injure both the negro and white

school children in Savannah. On the Court’s inquiry,

respondents refused to proffer any evidence in rebuttal

of this issue or in support of the injury averments in

their complaint, stating that the law so conclusively

presumed such injury to their class that no evidence

to show other or different injury in the Savannah area

could be considered by the trial court.

The District Court disagreed and, at respondents’

request at the close of trial (May 13), immediately

issued its preliminary judgment, denying the prayer

of the complaint, and giving respondents a right to re

open for further proof. (App. pp. 82a-90a)

Respondents appealed and moved for a preliminary

appellate injunction on May 20, 1963, for the same

relief denied below (Stell Rec. 55). The Court of

Appeals set this for hearing on May 24 (id. 80), heard

it (id. 135), and on the same day, entered its order

granting the requested injunction (id. 136) on the

basis of the “ All W rits” statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a)

(App. p. la). For its direction to the District Court

to enter the order as its own the Court of Appeals ad

ditionally referred to this Court’s ruling in Toledo

Scale Co. v. Computing Scale Co., 261 U.S. 399 (1923).

(b) Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, ei al. v.

Birdie Mae Davis, et al. (5th Cir. Ct. of App. No. 20657)

The complaint in this case was substantially similar

to that in Stell, and respondents, in addition to praying

a permanent injunction therefor, moved for a prelimi-

8

nary in junction requiring the submission within thirty

days of a desegregation plan to commence in Septem

ber, 1963. The preliminary injunction in the form

prayed by plaintiffs was denied on June 24, 1963, but

the Court directed the School Board to submit such a

plan to be heard at the trial, which had then been

scheduled for November.4

On July 1, 1963, respondents moved the Court of

Appeals for an injunction pending appeal “ and for

other orders”. On the same day the Court ordered

a hearing on July 8 (Davis Bee. p. 19) and granted re

spondents’ application on July 9 (id. pp. 21-8). In

its decision the Court said:

“ The ‘All W rits’ statute, 28 U.S.C.A. § 1651 gives

us the power to grant the relief sought by the

plaintiffs. St ell v. Savannoh-Chatham County

Board of Education, Fifth Circuit, 1963, F.

2d [No. 20557, May 24, 1963]. However, as

in that case, we think it is more appropriate to

frame the injunction and direct by mandate that

this injunction be made the order of the District

Court.” (App. p. 9a)

On an application for rehearing, the order was recalled

and reissued on July 18 to conform to the form used

in the interval in the Court’s decision in Armstrong.

In the opinion of the dissenting Judge:

“ The modification by the majority of their prior

order in this case compounds error. (App. p. 13a).

U * * *

“ . . . what has been done is at the expense of the

judicial process. A Court of Appeals should not

sit as a District Court in chancery . . . without

facts before it to serve as a basis for the decree.

4 It was tried on the dates scheduled and is now sub judice.

9

The All-Writs Statute, 26 TJ.S.C.A. § 1651, does

not authorize this . . . more constitutional rights

will be lost than gained in the long run by depar

ture from the procedures which have stood the

test of time, and which are a part of due process

of law as we have heretofore known it.” (App.

p. 15a)

A dissent was also filed by Judge Cameron after

rejection of his recommendation for an en banc hear

ing (Davis Ree. 41). A petition for review by cer

tiorari on the merits was filed and denied by this Court

on October 28, 1963; Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County v. Davis, 375 U.S. 894. No recon

sideration of the merits discussed in that application

is requested, the concurrent motion served herewith

being intended to consider only the formal validity of

the injunctive order of the Fifth Circuit.

(c) Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birmingham, Ala.

(5th Cir. Ct. of App. No. 20595)

In this case, as in the two eases previously detailed,

the complaint sought a mandatory injunction requir

ing the School Board to reorganize the school system

along stated lines. A preliminary injunction for the

same relief was made but by stipulation was merged

into the prayer for permanent relief and the ease was

tried on the merits. The Court found that the plain

tiffs in the case had failed to make any effort to comply

with the Alabama Pupil Placement Act which this

Court had held constitutional; Shuttlesworth v. Birm

ingham Board of Education, 358 U.S. 101 (1958). The

District Court retained jurisdiction to rehear the plain

tiffs on any contention that the manner of application

to them of that statute was improper. (App. p. 108a).

On June 3, 1963, the Armstrong respondents moved

10

the Court of Appeals to issue an injunction pending

appeal which would grant the relief denied below.

(.Armstrong Rec. p. 1). This was heard on June 26

(id. 21) and the requested injunction was granted on

July 12, Judge Gewin dissenting (App. p. 19a). An

application for rehearing en banc was denied July 22,

Judge Cameron filing an additional dissenting opinion

on July 30.

In its decision, the Circuit Court, Rives, J., directed

the issuance of an order by the District Court “ In

line with the procedure . . .in St ell, . . . ” (App. p. 29a)

and Tuttle, C. J., concurring specially, stated that a

definite plan “ should be required by an injunction

. . . pending the appeal of this case on the merits in

this Court. See St ell . . . , Davis . . .” (App. p. 31a).

Judge Gewin, in an extended dissent, stated:

“ I t should be noted quickly that the majority

opinion leaves little to be decided when the case

reaches this Court on the merits. Under the guise

of ‘injunction pending appeal’ that opinion sub

stantially decides the case and renders moot many

questions which could arise when the case reaches

the Court for final decision after a review of the

record . . . The action in this case is taken with

out any pretense that the Court has taken so much

as a hurried glance at the record.” (App. p. 32a)

Judge Gewin then discussed the questions involved

in issuing such an injunction pending appeal and dis

tinguished the action taken in Stell on the ground that

the Court had there considered it was reviewing an

interlocutory ruling. (App. p. 41a)

Judge Cameron also dissented saying:

“ The decision of this panel involves questions

of procedure which have for some weeks plagued

11

and are still plaguing the Court. The Judges of

the Court are sharply divided on these questions

and not only the lawyers of the Circuit, but the

public generally, are displaying open concern

with respect to inconsistent positions which they

conceive are being taken by the Court. . . .

“ The procedure followed by the majority here

is one which, in my opinion, is not sanctioned by

the law. The hearing before these three Judges

was not an appeal. Rather, it was what the Third

Circuit has termed something ‘ in the nature of an

original proceedings . . .’ I t was the substitution

of a hearing on ‘injunction pending appeal’ for

a hearing on appeal. Theoretically the appeal is

still pending, but it is apparent that there is little

or nothing more to hear since the decision and

order of the majority of the panel are on the

merits of the ease, deciding in full, without the

benefit of any record of the evidence in the lower

court, the questions of law and fact which were

before that court in its extended hearing. (App.

pp. 58a-60a). * * *

“ The last sentence of Judge Bell’s special concur

rence in the July 9th hearing characterizes poig

nantly the dilemma into which this Court has been

plunged since it set itself the task of inventing

special procedures for the handling of such cases :

‘This case serves as a classic example of the

pitfalls to be encountered, with the attendant

disruption and delays in the orderly administra

tion of justice, when courts depart from the

time-tested processes of law.’ ” (App. p. 60a)

(d) Harris ei al. v. Gibson and Glynn County Board of

Education et al. (5th Cir. Ct. of App. No. 20871)

This action followed the pattern of the preceding

three, except that in this case respondents filed their

prayer for temporary and permanent injunctions as

12

intervenors in a suit brought to restrain the Board

of Education from effecting a pupil transfer except in

accordance with Court order and the Georgia School

Code. The action was commenced in August, 1963, and

on motion of the Gibson respondents to intervene and

be heard on the broad issue of desegregation, the Court

set the matter down for a pretrial hearing on Septem

ber 5. At that hearing, the Court allowed the requested

intervention and then heard arguments both on re

spondents’ motion for a preliminary injunction and

the petitioners’ motion for judgment for failure of the

School Board to have held a public hearing under the

Georgia School Code prior to their approving the

transfers in question.

To limit the issues and to obviate the jurisdictional

objection, the Court by pretrial order directed the

School Board to promptly hold an open record hear

ing under the Georgia Code, limiting the parties on

the subsequent trial to the issues and evidence pre

sented before the Board. The Court further required

the Board to recommend a complete plan of desegrega

tion for the County, including the six transfers com

plained of.

Respondents appealed this order to the Fifth Circuit

on the ground that it constituted a denial of their mo

tion for a preliminary injunction enforcing the trans

fers before trial. At the same time, they prayed an

interlocutory appellate injunction for the relief stayed

below. The order of the District Court was entered on

September 6 : the application to the Court of Appeals

was filed on September 10 and was heard and decided

on September 12. (Gibson Rec. 8-9, 22 and 23) In

its decision granting the injunction to respondents,

the Court of Appeals held that the pretrial order of

13

the District Court was both an interlocutory appeal-

able order under 28 U.S.C. § 1292 and an appealable

final order under 28 U.S.C. § 1291. (App. p. 80a)

REASONS RELIED ON FOR ALLOWANCE OF WRIT

Each of the considerations referred to in this Court’s

Rule 19(1) (b) exists with respect to the Fifth Circuit

opinions for which review is sought.

1. They are contrary to the decisions in the only

other four cases which petitioners have found of an

application to a Federal Court of Appeals for a man

datory injunction to grant final relief pending determi

nation of an appeal on the merits. There is one such

case each in the Sixth and Ninth Circuits, the other

two being in the Fifth Circuit itself (infra p. 21-3).

2. The Federal law question regarding the powers

of United States Courts of Appeals to grant this type

of order—either as a matter of inherent authority, by

precedent in equity, or through legislative enactment,

is both unique and important. The four orders in

question appear to be the only four published orders

of this nature issued by any United States Court of

Appeals.

3. In the opinion of your petitioners, the action of

the Court of Appeals in the issuance of the orders con

cerned has so far departed from the accepted and

usual course of judicial proceeding as to call for an

exercise of this Court’s power of supervision. Peti

tioners concede that applications such as this are not

favored because made during the pendency of appeals

in the Court of Appeals. However, it is the position of

petitioners, and one we believe reasonably taken, that

the “ deviation from normal appellate processes”

14

phrase in this Court’s Rule 20 is more descriptive of

the action of the Court of Appeals in the four cap

tioned cases than of the present application for review.

4. Petitioners recognize that the merits of the pend

ing appeals involve controversial political and social

issues, issues evocative of strong emotional reactions

not always limited to the protagonists. Since we pray

no review on these issues, we do not urge their im

portance as a basis for the granting of this petition.

We do urge the corollary, however, that such cases

should receive the same tempered measure of judicial

consideration as more mundane issues and should not

become a quasi-administrative and summary exception

to the normal procedures of the Judicial Branch.

5. Three of the four orders abrogate otherwise ap

plicable and constitutionally valid state legislation.

ARGUMENT

What we are here concerned with, is a relatively

narrow question. We deal with mandatory as opposed

to prohibitory injunctions and only those which alter

rather than maintain or restore a status quo. We are

concerned solely with appellate interlocutory injunc

tions and only such of those as grant relief to the ap

pellant which is the same as the relief he seeks by ap

pellate process itself, i.e., ‘final’ relief in the action.

It would be futile to deny that the broad powers

of the United States courts include every form of writ

which may be required to assure to the ultimately

prevailing party an effective and meaningful remedy.

We do deny, however, that such authority extends to

the granting of anticipatory relief in the nature of in

stant reversal based on appellate prejudgment of the

merits.

15

In the following argument, your petitioners will at

tempt to show first, that there is no statutory basis

for the orders in question nor any precedent in equity

or in the opinions of other courts. Second, we will en

deavor to show that the issuance of the orders in ques

tion conflicts with decisions in the Sixth and Ninth

Circuits and with the earlier decisions of the Fifth

Circuit and deviates from the judicial policies declared

by this Court.

I. THE AUTHORITIES CITED BY THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT DO NOT SUSTAIN THAT COURT'S

POWER TO ISSUE A MANDATORY INJUNCTION, GRANTING

THE FULL RELIEF SOUGHT BELOW, PENDING DETERMI

NATION OF AN APPEAL ON THE MERITS.

(a) The "All Writs" Statute (28 U.S.C. § 1651)

(1) Statutory Language

The Court of Appeals assumed jurisdiction to grant

relief in these cases primarily under the “ All W rits”

statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1651, which reads:

(a) The Supreme Court and all courts established

by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary

or appropriate in aid of their jurisdictions and

agreeable to the usages and principles of law.

(Emphasis added).

This Court has held that the power given to the courts

under this provision of the Judicial Code is limited,

and must be exercised in accordance with the prin

ciples of equity jurisprudence which were known to

the common law, (United States v. Morgan, 346 U.S.

502 (1954) ; United States v. Hayman, 342 U.S. 205,

221 n. 35 (1952)), and which have attached themselves

over the years to the particular writ in question (Price

v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266, 282 (1948)).

16

Tims, in DeBeers Mines v. United States, 325 U.S.

212 (1945), this Court vacated an injunction issued

under the statute, after reviewing the “ course of de

cision in chancery,” and finding that “ No relief of this

character has been thought justified in the long history

of equity jurisprudence.” (id., 223)

(2) Principles of Equity

The purpose of the writ of preliminary mandatory

injunction at common law was “ wholly preventive,

prohibitory or protective,” with its use being re

stricted to situations where its effect would be to

restore the plaintiff to his “ former” or “ original”

position. 4 Pomeroy’s Equity Jurisprudence, §§ 1337,

1359 (4th ed. 1919). Thus, where the object of the

writ is to maintain or restore the status quo ante litem,

the power of the federal courts to issue preliminary

mandatory injunctions is clearly recognized. In re

Lennon, 166 U.S. 548 (1897); Bergen Drug v. Parke

Davis Co., 307 F. 2d 725 (3rd Cir. 1962).

The preliminary mandatory injunction, like the pre

liminary prohibitory injunction, has traditionally

served “ to keep the parties, while the suit goes on, as

far as possible in the respective positions they occu

pied when the suit began” (Hamilton Watch Co. v.

Benrus Watch Co., 206 P. 2d 738, 742 (2d Cir. 1953)).

But its issuance can be justified only when necessary

to preserve or restore the status quo pending final

determination of the merits of a litigation. 28 Am.

Jur. “ Injunctions” § 17; 15 ALE 2d 213, 234; Toledo

A.A. and N.M. By. Co. v. Pennsylvania Co., 54 Fed.

730 (N.D. Ohio 1893).

So firmly established is the equitable principle that

mandatory preliminary injunctive relief will be

17

granted only to maintain the status quo ante litem

that the Federal district courts have refused, through

the years, to grant relief beyond that limited scope.

See Clune v. Publishers Assoc, of New York City, 214

F. Supp. 520 (S.D.N.Y. 1963) ; Gantt v. Clemson Agr.

Coll, of So. Car., 208 F. Supp. 416 (W.D. So. Car.

1962); Willheim v. Murchison, 203 F. Supp. 478

(S.D.N.Y. 1962), aftVI Willheim v. Investors Diversi

fied Services, Inc., 303 F. 2d 276 (2d Cir. 1962);

Winton Motor Carriage Co. v. Curtis Publishing Co!,

196 Fed. 906 (E.D. Pa. 1912); and American Lead

Pencil v. Schneegass, 178 Fed. 735 (N.D. Ga. 1910).

In those cases where the district courts have ex

ceeded their equity jurisdiction and granted relief

requiring affirmative action beyond that necessary to

reinstate a pre-existing status quo, they have been

summarily reversed. See Tanner Motor Livery v.

Avis, Inc., 316 F. 2d 804 (9th Cir. 1963) ; Miami Beach

Federal Savings and Loan Assoc, v. Callander, 256 F.

2d 410 (5th Cir. 1958) ; Warner Bros. v. Gittone, 110

F. 2d 292 (3d Cir. 1940) ; and United States v. Adler’s

Creamery, 107 F. 2d 987 (2d Cir. 1939).

A correlative equity principle is that the merits of

the controversy are not to be decided on an applica

tion for preliminary relief. Tanner Motor Livery v.

Avis, Inc., supra; and Miami Beach Federal Savings

& Loan Assoc, v. Callander, supra-. From this prin

ciple has developed the firmly rooted rule that where

the granting of a preliminary injunction would give

to the plaintiff all the relief to which he would be en

titled were he to obtain a final decree in his favor on

the merits, the request for preliminary relief should

be denied. Tanner Motor Livery v. Avis, Inc., supra;

Mack v. General Motors Corp., 260 F. 2d 886 (7th Cir.

18

1958) ; Westinghouse v. Free, 256 P. 2d 806 (7th Cir.

1958); United States v. Adler’s Creamery, supra;

Gantt v. Clemson Agr. Coll, of So. Car., supra; Will-

heim v. Investors Diversified Services, Inc., supra;

and American Lead v. Scheegass, supra.

In each of the instant cases, the application of re

spondents for injunctive relief both temporary and

permanent was to alter a pre-existing status in their

favor. To give them such relief preliminarily is to give

them what they would at most be entitled to if they bad

succeeded on the merits after trial and appeal. As the

Third Circuit said in Warner Bros. v. Gittone, supra:

. . . the effect of the preliminary injunction which

the court granted was not to preserve the status

quo but rather to alter the prior status of the

parties fundamentally. Such an alteration may

be directed only after final hearing, the office of

a preliminary injunction being, as we have pointed

out, merely to preserve pendente lite the last

actual noncontested status which preceded the

pending controversy. . . .

Irreparable loss resulting from refusal to accord

plaintiff a new status, as distinguished from inter

ference with rights previously enjoyed by him,

does not furnish the basis for interlocutory" relief.

110 P. 2d 292, 293.

(b) Other Statutes

In addition to its stated reliance on 28 U.S.C. § 1651,

the Court of Appeals has referred to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291

and 1292 as sources of such authority (App. pp. la,

2a, 80a). 28 U.S.C. §1291 confers upon courts of

appeals “ jurisdiction of appeals from all final deci

sions of the district courts of the United States. . . . ”

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a) (1) gives the courts of appeals

19

“jurisdiction of appeals from: (1) Interlocutory

orders of the district courts of the United States . .

(italics ours).

Petitioners submit that the Fifth Circuit is clearly

in error in its reference to these provisions. Both sec

tions confer jurisdiction over the merits of an appeal,

not a new and different writ power. Petitioners con

cede that these appeals are properly pending in the

Fifth Circuit, that that Court’s jurisdiction extends

to their merits. What we say is that this does not

concern the form in which the Court must exercise

its admitted jurisdiction, this does not change the

nature of the judicial process.

(c) Opinions Cited by the Court of Appeals

In its opinions in these cases, the Court of Appeals

has cited as its precedent on appellate injunctive power

the cases themselves. I t has additionally cited deci

sions, not here relevant, to distinguish between final

and interlocutory orders, the power of District Courts

over substantive aspects of school plans, and the power

of a Court of Appeals to make its mandate effective

through District Court orders.

But, apart from the eases for which review is here

sought no other decision referred to by the Court of

Appeals is authority for the existence of appellate

power to issue the type of injunction in question.

Although four other decisions are cited for the claimed

authority, each of them concerns only a prohibitory

order intended to prevent a change in the status quo

which would make ineffective the appellate remedy.

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961),

(cited in Gilson, App. p. 80a) reversed a denial by the

20

District Court of a temporary restraining order against

state prosecution pending a hearing for preliminary

injunction because the District Court’s action deter

mined “ substantial rights of the parties which will be

irreparably lost if review is delayed until final judg

ment” (295 F. 2d 772, 778).5

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) was also cited in

Gibson. I t affirms Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (8th

Cir. 1958), reversing a District Court suspension of a

court approved school integration plan after a hearing

of the case on the merits. In its St ell opinion (App.

p. la), the Fifth Circuit cited the other Aaron v. Cooper

decision, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir., 1958), restraining the

leasing of public schools to a private school corporation

pending a final determination on the merits. Also cited

in St ell was Toledo Scale Co. v. Computing Scale Co.,

261 U.S. 399 (1923), where this Court upheld the power

of a Court of Appeals under the “All W rits” statute to

direct a District Court to enjoin a party to a suit before

it from interfering with the Court’s process by bringing

a conflicting suit in another jurisdiction.

Your petitioners submit that none of the foregoing

decisions constitutes acceptable precedent for the extra

ordinary writ powers claimed by the Court of Appeals

in the instant cases.

5 Since the granting or denial of a temporary restraining order

is not ordinarily appealable, the Circuit held this to be a reviewable

“ final order” under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

21

II. THE ORDERS SOUGHT TO BE REVIEWED ARE IN CONFLICT

WITH THE DECISIONS IN OTHER CIRCUITS AND WITH

PRIOR DECISIONS IN THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

Your petitioners’ research has found only four other

cases in which affirmative interlocutory injunctions

approximating final relief have been asked of a United

States Court of Appeals. In each of the four such

relief has been denied.

In Dunn v. Retail Clerks International Association,

299 P. 2d 873 (6th Cir. 1962), the Court of Appeals

refused to issue a mandatory injunction pending appeal

compelling a regional director of the National Labor

Relations Board to bring legal action against alleged

unlawful picketing or, in the alternative, to issue an

injunction directly enjoining the picketing. The relief

had been denied by the District Court, in an action

brought by the owners of the property being picketed,

not by the regional director of the NLRB. The District

Court also had denied an application for a mandatory

injunction pending appeal.

The statement of the case by the Court of Appeals

indicates its similarity to the present litigation (299 P.

2d 873, 874) :

“ The relief prayed for here is much broader than

a mere restraining order preserving the status quo.

* * * * * * * * *

“ The mandatory order which appellants request

is the ultimate relief sought in the District Court

and in this appeal. To obtain such relief appel

lants would have to prevail on the merits of the

case. We ought not to grant temporary relief

which would finally dispose of the case on its

merits . . . ”

The same conclusion was reached by the Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Hess v. Woods, 185

22

F. 2d 404 (9th Cir. 1950). The District Court had

denied an injunction against the continuing enforce

ment of the Housing and Rent Act of 1947 on the

ground that it was being asked to change the status

quo. Plaintiffs applied to the Court of Appeals for an

immediate “ restraining order” and “ injunction”

against the Housing Expediter and his subordinates,

which in denying the application, stated (185 F 2d

404) :

“ In short, we are asked to suspend all activity of

an important governmental agency before the'ap

peal is before us for adjudication as to whether

the District Court should take jurisdiction and try

the case on the merits. No order with such far-

reaching consequences should be made by any

court before the merits of the controversy have

been tried and adjudicated.”

In two earlier civil rights type cases, the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has itself denied manda

tory injunctive relief pending determination of the

merits of the appeals on the same ground, following

denials of such injunctions by the trial court. In Mere

dith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 341 (5th Cir. 1962), an appeal

was taken from a District Court denial of an interlocu

tory order compelling a state university to admit the

negro plaintiff. The plaintiff then moved the Court of

Appeals for such an injunction during the pendency of

his appeal. In denying this motion, the Court noted

that “ the testimony taken before the district court is

not yet available to this Court” and stated that judg

ment should be withheld until there had been “ an op

portunity to study the full record and testimony on the

hearing before the district court” (id., 341-2).

The same ruling was made in Greene v. Fair, 314 F.

2d 200 (5th Cir. 1963), where the District Court had

abstained from ruling on plaintiff’s university admis-

23

sion request, pending his applying to the admissions

committee of the school. Plaintiff prayed for an in

junction pending appeal to compel his immediate ad

mission, asserting that 28 U.S.C. § 1651 gave the Court

power to take such action. The Court denied any

interlocutory mandatory relief, pointing out that (id.,

202) “ The rules of this Court make possible a prompt

hearing of all regularly docketed appellate cases.”6

As to the views of that Court on such injunctions

when issued by a District Court, Chief Judge Tuttle

has stated:

“ Upon analyzing the trial court’s order, issued

without any evidence being submitted, even though

perhaps at least partially at the instigation and

insistence of the litigants, it appears much broader

than the relief requested and than the question at

hand. The matter before the court was a motion

for a preliminary injunction which by its nature

has the purpose of preserving the status quo to

prevent irreparable injuries until the merits of

the issues can be decided.

* * *

“ The judgment awarded appears to provide the

plaintiffs with practically all of the relief, if not

more, than they sought on the merits, . . .

* * *

“ We have repeatedly held that an order for a

temporary injunction does not and cannot decide

6 Possibly because nothing is left to be accomplished by a hear

ing on the merits, it is only in St ell of the four cases here con

sidered that respondents have filed a record or taken other action

to bring the matter on for a hearing on appeal. Moreover, in St ell

within the past week, appellants have moved for further time to

file a supplemental record covering District Court proceedings

directed by the interlocutory order here complained of and which

occurred after the appeal was taken—necessarily relevant only to

issues created by the appellate injunction, not the merits of the

case as tried!

24

the merits of the case . . . ” Miami Beach Federal

Sav. & Loan Assoc, v. Callander, 256 F. 2d 410, 415

(5th Cir. 1958)

III. THIS COURT, IN THE EXERCISE OF ITS SUPERVISORY

POWERS OVER THE LOWER FEDERAL COURTS, SHOULD

VACATE THE INJUNCTIONS GRANTED IN THESE CASES

AND REMAND TO THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR PROMPT

HEARINGS ON THE MERITS.

The procedural issue raised by this application is

a narrow, hut extremely important one in the admin

istration of justice. There is no effective control ex

cept judicial self-control in defining the incidents of

judicial power. I t is in cases such as these four, whose

merits concern deeply controversial issues, that courts

will always have the greatest difficulty in adhering to

established practice.

Mr. Justice Holmes’ famous dissent in Northern

Securities Co. v. United States, 193 II.S. 197, 400-1

(1904), describes the problem:

“ Great cases like hard cases make bad law. For

great cases are called great, not by reason of their

real importance in shaping the law of the future,

but because of some accident of immediate over

whelming interest which appeals to the feelings

and distorts the judgment. These immediate

interests exercise a kind of hydraulic pressure

which makes what previously was clear seem

doubtful, and before which even well-settled prin

ciples of law will bend.”

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, concurring in Joint Anti-

Fascist Befugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S.

123,149 (1951), recognized that where legal issues were

“ inescapably entangled in political controversies” and

“ touch the passions of the day,” it was the duty of

the Courts to “ dispose of a controversy within the

narrowest confines that intellectual integrity per-

25

mits.” Concurring in Dennis v. United States, 341

U.S. 494, 528 (1951), he said:

“ Unless we are to compromise judicial impar

tiality and subject these defendants to the risk of

an ad hoc judgment influenced by the impregnating

atmosphere of the times, the constitutionality of

their conviction must be determined by principles

established in cases decided in more tranquil

periods.”

This Court in DeBeers Mines v. United States,

325 U.S. 212, 222 (1945), adhered to precedent in the

face of strong pressure from the Government to in

crease the scope of judicial authority:

“ This suit, as we have said, is not to be distin

guished from any other suit in equity. What

applies to it applies to all such.”

* * *

The powers exercised by the Court of Appeals are

not known to equity, are not granted by statute, they

circumvent the established course of appellate review,

directly affect the integrity of the judicial process, the

administration of the courts and create conflict between

circuits. Review by certiorari should be granted as

prayed.

Respectfully submitted,

Geo. S tephen L eonard

R eid B. B arnes

Attorneys for Respondents

Of Counsel:

R. Carter P ittman

Charles J. B loch

J. W alter Cowart

R ichard L. H irshberg

R obert C. M aynard

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

OPINIONS OF COURTS BELOW

U N IT E D STA TES COU RT OE A PPEA L S

F IF T H C IR C U IT

R a l p h S t e l l e t al ., Appellants,

v.

S a v a n n a h -C h a t h a m C ounty B oard of E ducation et al .,

Appellees.

No. 20557.

May 24, 1963.

E. H. Gadsden, B. Clarence Mayfield, Savannah, Ga.,

Constance Baker Motley, New York City, for appellants.

J . W alter Cowart, Savannah, Ga., Charles J . Bloch,

Macon, Ga., E. Freeman Leverett, Elberton, Ga., R. Basil

Morris, Savannah, Ga., for appellees.

Before T u t t l e , Chief Judge, and R ives and B e l l , Circuit

Judges.

T u t t l e , Chief Judge.

This is a motion for an injunction to be entered by this

Court pending our consideration on the merits of an appeal

from an order of the District Court for the Southern Dis

trict of Georgia dated May 13, 1963, denying appellants’

motion for a preliminary injunction requiring a prompt

start to the desegregation of the Savannah-Chatham County

Schools.

A judgment denying a motion for preliminary injunction

is an appealable order, though interlocutory. 28 U.S.C.A.

2a

§ 1292(1). This Court has the power to issue all writs

necessary or appropriate in aid of its jurisdiction and agree

able to the usages and principles of law. 28 U.S.C.A. §

1651(a). An injunction pending appeal is such a writ.

Aaron v. Cooper, 8 Cir., 261 F.2d 97, 101. The power

granted to Courts of Appeal under Section 1651, commonly

known as the “ All W rits” statute is meant to be used only

in the exceptional case where there is clear abuse of dis

cretion or usurpation of judicial power. Bankers Life &

Casualty Company v. Holland, 346 U.S. 379, 74 S.Ct. 145,

98 L.Ed. 106. I t should be invoked only in ‘ ‘ extreme cases. ’ ’

LaBuy v. Hawes Leather Company, 352 H.S. 249, 77 S.Ct.

309, 1 L.Ed.2d 290. This is such a case.

The trial court made the following finding of fact touch

ing on the critical question as to whether the prim ary and

secondary schools of Savannah-Chatham County are ra

cially segregated:

“ The prim ary and secondary public schools of ,Sa-

vannah-Chatham County are divided into schools for

white pupils and schools for negro pupils and admis

sion thereto is limited to applicants of the respective

races.”

The Supreme Court of the United States, in Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686,

98 L.Ed. 873, said:

“ We conclude that in the field of public education the

doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal. There

fore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly

situated for whom the actions have been brought are,

by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of

the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

This decision by the Supreme Court should have ended

the m atter for the district court to the extent that upon

3a

its making this determination its duty was then to do what

the Supreme Court directed to be done upon the second

appearance of the Brown v. Board of Education case in the

Supreme Court, 349 U.S. 294, at page 300, 75 S.Ct. 753,

at page 756, 99 L.Ed. 1083, where the Court said:

‘ ‘ The courts will require that the defendants make a

prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance

with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such a start has

been made, the courts may find that additional time

is necessary to carry out the ruling in an effective

manner.” (Emphasis added).

Instead of doing this the trial court permitted an inter

vention by parties whose sole purpose for intervening was

to adduce proof as a factual basis for an effort to ask the

Supreme Court to reverse its decision in Brown v. Topeka

Board of Education. The court then permitted evidence

in support of this approach by the intervenors, and denied

the appellants’ motion for preliminary injunction solely on

the basis of such evidence, which, briefly stated, tended to

support the thesis that compliance with the Supreme

Court’s decision would be detrimental to both the Negro

plaintiffs and to white students in the Savannah-Chatham

County school system.

The district court for the Southern District of Georgia

is bound by the decision of the United States Supreme

Court, as are we. Unless and until that Court overrules

its decision in Brown v. Topeka, no trial court may, upon

finding the existence of a segregated school system, refrain

from acting as required by the Supreme Court merely be

cause such district court may conclude that the Supreme

Court erred either as to its facts or as to the law.

It is, therefore, clear that on the day of the entry by

the trial court of its order it was a clear abuse of its dis

cretion for the trial court to deny appellants’ motion for

a preliminary injunction requiring the defendant School

4a

Board to make a prompt and reasonable start towards de

segregating the Savannah-Chatham Connty schools.

In such circumstances, because it has now been more

than nine years since the Supreme Court made it plain what

the duties of the Boards of Education are under such cir

cumstances, and because any further delay might prevent

the enjoyment by the appellants of their clear rights as of

the beginning of a new school year in September, 1963, we

must determine what relief should be granted in response

to this present motion.

We have heretofore concluded that this Court has the

power to grant an injunction pending the final hearing of

the case on the merits in the Court of Appeals. However,

it is clearly more desirable for injunctive relief to be

granted at the level of the trial court rather than by an ap

pellate court if the same necessary results can be accom

plished. Included in the powers of the Court of Appeals

under the All-Writs ‘Statute, is the power of the Court of

Appeals to frame the terms of an injunction and direct the

trial court to enter such injunction and make it the order of

the trial court. See Toledo Scale Co. v. Computing Scale

Co., 261 U.S. 399, 43 S.Ct. 458, 67 L.Ed. 719. There the

Supreme Court sa id :

“ Under § 262 of the Judicial Code [the predecessor

of the All-Writs statute] [the Court of Appeals] had

the right to issue all writs not specifically provided for

by statute which might be necessary for the exercise of

its appellate jurisdiction. I t could, therefore, itself

have enjoined the Toledo Company from interfering

with the execution of its own decree, Merrimac River

Savings Bank v. Clay Center, 219 U.S. 527, 535 [31

S.Ct. 295, 55 L.Ed. 320]; or it could direct the District

Court to do so, as it did.” 261 U.iS. 399, 426, 43 S.Ct.

458, 465, 67 L.Ed. 719.

5a

We think it appropriate, therefore, to frame an injunc

tion and direct by mandate that this injunction be made the

order of the District Court.

It is, therefore, ordered that the District Court for the

Southern District of Georgia enter the following judgment

and order:

“ The defendant, Savannah-Chatham County Board

of Education and the other individual defendants (nam

ing them specifically) and their agents, servants, em

ployees, successors in office and those in concert with

them who shall receive notice of this order, be and they

are hereby restrained and enjoined from requiring and

permitting segregation of the races in any school under

their supervision, from and after such time as may be

necessary to make arrangements for admission of chil

dren to such schools on a racially non-discriminatory

basis with all deliberate speed, as required by the Su

preme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, 349 U,S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083.

“ It is further ordered, adjudged and decreed that

said persons be and they are hereby required to sub

mit to this Court not later than July 1, 1963, a plan

under which the said defendants propose to make an

immediate start in the desegregation of the schools of

Savannah-Chatham County, which plan shall include

a statement that the maintenance of separate schools

for the Negro and white children of Savannah shall

be completely ended with respect to at least one grade

during the school year commencing September, 1963,

and with respect to at least one additional grade each

school year thereafter.”

This order shall remain in effect until the final deter

mination of the appeal of the within case in the Court of

Appeals for the F ifth Circuit on the merits and until the

further order of this Court. During the pendency of this

6a

order the trial coart is further directed to enter such other

and further orders as may be appropriate or necessary in

carrying out the expressed terms of this order.

The Clerk is directed to issue the mandate forthwith.

U N IT E D STA T E S COU RT OF A PPEA L S

F IF T H C IR C U IT

B irdie M ae D avis e t al ., Appellants,

v.

B oard of S chool C o m m issio n er s of M obile C o u n ty ,

A labama et al ., Appellees.

No. 20657.

July 9, 1963.

On Rehearing July 18, 1963.

Dissenting Opinion July 30, 1963.

# # # * # # # # * *

Vernon Z. Crawford, Mobile, Ala., C. B. Motley, New

York City, for appellants.

George F. Wood, Mobile, Ala., Joseph F. Johnston, B ir

mingham, Ala., for appellees.

Before B r o w n , W isdom and B e l l , Circuit Judges.

P er C u r ia m .

Plaintiffs here seek an injunction by this Court pending

our determination of the merits of an appeal from an order

entered on June 24, 1963, by the District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama. This suit originated when

Plaintiffs filed a class action seeking the desegregation of

the Mobile County school system. Plaintiffs sought an

immediate order requiring the Defendant School Commis-

7a

sioners to submit a plan of desegregation within thirty

days. This motion was denied by the District Court. In

the alternative, Plaintiffs sought a preliminary and per

manent injunction prohibiting the further operation of seg

regated schools. The Court took this motion under sub

mission and ordered briefs to be filed within a specified time.

Plaintiffs appealed from this ruling asserting that the

failure to immediately rule on the motion for preliminary

injunction amounted to a denial of the motion. On that

appeal, this Court held that the trial Judge had not abused

his discretion. Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County, 5 Cir., 1963, 318 F.2d 63.

Subsequently, the District Court held a hearing and made

the following determination. By its order of June 24, the

Court denied Plaintiffs ’ motion for preliminary injunction.

The case was set for trial on November 14, 1963 and the

Defendants were directed “ to present at the trial * * * a

specific plan for the operation of the schools under their

authority and control on a racially non-discriminatory basis,

consistent with the principles established by the Supreme

Court, to commence not later than the beginning of the

1964-65 school year.” I t is from this order that Plaintiffs

have appealed to this Court, seeking in the meantime an

injunction requiring the Mobile County schools to commence

integration not later than September 1963.

We are in agreement with Plaintiff’s theory. The De

fendant Board has not come forward with an acceptable

reason why the integration program should be further

delayed. No one disputes that the public schools of Mobile

County are presently operated on a segregated basis.

“ I t is now more than nine years since this Court held

in the first Brown decision * * * 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct.

686 , 98 L.Ed. 873, that racial segregation in state public

schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

* * # * • # * * #

8 a

“ Given the extended time which has elapsed, it is far

from clear that the mandate of the second Brown de

cision [349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083] re

quiring that desegregation proceed with ‘ all deliberate

speed’ would today be fully satisfied by types of plans

or programs for desegregation of public educational

facilities which eight years ago might have been deemed

sufficient. Brown never contemplated that the concept

of ‘ deliberate speed’ would countenance indefinite delay

in elimination of racial barriers in schools * #

Watson v. City of Memphis, 1963, 373 U.S. 526, 83

S.Ct. 1314, 10 L.Ed.2d 529.

“ Now * * * eight years after [the second Brown de

cision] was rendered and over nine years after the

first Brown decision, the context in which we must

interpret and apply this language [‘all deliberate

speed’] to plans for desegregation has been signifi

cantly altered.” Goss v. Board of Education of City

of Knoxville, 1963, 373 U.S. 683, 83 S.Ct. 1405, 10

L.Ed.2d 632.

The District Judge in his memorandum opinion discusses

two principal reasons why preliminary injunctive relief

should not now be granted. The first is that there would

be an impossible administrative burden placed on the school

system. The second is the Court’s belief, based upon ex

perience over the past several years in other race civil

rights matters, that if this action is not too hastily taken,

the problem will work itself out with no strife or similar

consequences.

For reasons which bear on both of them, we think neither

of these grounds is sufficient. The administrative problem

is not one created by the Plaintiffs. They have for nearly

a year sought without success to get the school authorities

to desegregate the schools. The fact that the suit was not

filed until March 1963 is not therefore of controlling im-

9a

portance. As to the second ground, there is nothing on the

present record to afford either the District Judge or this

Court any assurance that the requested forebearance will

produce effective results. The Defendants have not even

answered as yet. They have filed a motion to dismiss for

failure to state a claim. Although it seems to be acknowl

edged on all hands that a racially segregated system is still

maintained, the Defendants’ legal position under this mo

tion is that the Plaintiffs have not set forth a claim entitling

them to relief. So far as this record shows, the Defendant

school authorities have not to this day ever acknowledged

that (a) the present system is constitutionally invalid or

(b) that there is any obligation on their part to make any

changes at any time. At this late date the Plaintiffs, who

represent Negro children who are presently being denied

constitutional rights, are entitled to minimum effective

relief. With the trial date now fixed in November, it means

that effective relief is denied for another school year with

no assurance that even at such later date anything but a

reaffirmation of the teaching of the Brown decision will be

forthcoming. The Plaintiffs showed a clear case entitling

them to interim relief pending a final hearing, and it was

an abuse of the District Court’s discretion not to enter

a preliminary injunction.

The “ All W rits” statute, 28 U.S.C.A. §1651, gives us

the power to grant the relief sought by Plaintiffs. Stell

v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education, 5 Cir.,

1963, 318 F.2d 425. However, as in that case, we think it

more appropriate to frame the injunction and direct by

mandate that this injunction be made the order of the

District Court.

I t is therefore, O rdered that the District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama enter the following judgment

and order:

“ The Defendant, Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County and the other individual Defendants

1 0a

(naming them specifically) and their agents, servants,

employees, successors in office and those in concert with

them who shall receive notice of this order, he and

they are hereby restrained and enjoined from requir

ing and permitting segregation of the races in any

school under their supervision, from and after such

time as may be necessary to make arrangements for

admission of children to such schools on a racially non-

discriminatory basis with all deliberate speed, as re

quired by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, 1955, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753,

99 L.Ed. 1083.

“ I t is further ordered, adjudged and decreed that

said persons be and they are hereby required to make

an immediate start in the desegregation of the school

of Mobile County, and that a plan be submitted to the

District 'Court by August 1, 1963, which shall include

a statement that the maintenance of separate schools

for the Negro and white children of Mobile County shall

be completely ended with respect to the first grade

during the school year commencing September 1963,

and with respect to at least one successively higher

additional grade each school year thereafter.”

The District Court may modify this order to defer de

segregation of rural schools in Mobile County until Septem

ber 1964, should the District Court after further hearing

conclude that special planning of administrative problems

for rural schools in the county make it impracticable for

such schools to start desegregation in September 1963.

This order shall remain in effect until the final determi

nation of the appeal of the within case in the Court of

Appeals for the F ifth Circuit on the merits, and until the

further order of this Court. During the pendency of this

order the trial court is further directed to enter such other

1 1a

and further orders as may be appropriate or necessary in

in carrying out the expressed terms of this order.

The Clerk is directed to issue the mandate forthwith.

B e l l , Circuit Judge (dissenting).

I dissent. I would support the view of the District Judge

that the time remaining before the opening of school in

September is insufficient to make the change from a segre

gated to a desegregated school system as requested.

The chance of disruption of the educational process in

Mobile likely to be encountered in planning and effecting

the necessary changes on such short notice outweighs

the damage which may be incurred by Plaintiffs in wait

ing another year. Thus, I would not hold that the Dis

trict Judge abused his discretion. The loss of the year

can be made up by requiring that two grades be desegre

gated beginning in 1964. I would join in the order if it

encompassed this change.

Time for the effectuation of orderly school manage

ment procedures is essential, and we should be careful not

to give rise to an untoward situation in school administra

tion at this late hour. Registration for the upcoming term

has been completed, and school officials and staffs are in

the vacation season. This is particularly so where we are

passing on a motion in a case not filed until March, 1963.

On Petition for Rehearing

P er Cu r ia m .

This m atter is before the Court on the petitioners’ ap

plication for a rehearing.

July 9, 1963, this Court by mandate directed the District

Court to enter an injunction and order requiring the Board

of Commissioners of Mobile County to submit to the Dis

trict Court by August 1, 1963, a step-ladder plan for de

segregating the public schools in Mobile, starting with

1 2a

the first grade in September 1963. Three days later, an

other panel of the Court decided Armstrong v. Board of

Education of the City of Birmingham, No. 20595, 5 Cir., —

F.2d —. In that case the Court declined to issue an in

junction pending appeal which would go so far as to pro

vide “ when and how the complete desegregation of

the public schools may be accomplished.” The Court’s

mandate requires the Birmingham School Board to sub

mit by August 19, 1963, a plan for an immediate start

in desegregation by applying the Alabama Pupil Place

ment Law to all school grades.

At this initial stage in the travail of desegregating

the public schools in Alabama, the School Boards of Mobile

and Birmingham face substantially the same social, legal,

and administrative difficulties. We express no opinion of

the merits of uniformity in school desegregation as against

a school board’s tailoring a plan and a trial judge’s

shaping a decree, to fit a particular school system.

But we have reached the conclusion that at this early

point in the legal proceedings, at a time when no school

board in Alabama has formulated any plan for desegre

gation, there should not be one law for Birmingham and

another for Mobile. We have decided therefore to con

form the Mobile order to the Birmingham order.

Accordingly, the Court amends the judgment and

order of Ju ly 9, 1963, issued as the mandate, by de

leting the following paragraph:

“ I t is further ordered, adjudged and decreed

that said persons be and they are hereby required to

make an immediate start in the desegregation of the

school of Mobile County, and that a plan be sub

mitted to the District Court by August 1, 1963, which

shall include a statement that the maintenance of

separate schools for the Negro and white children of

Mobile County shall be completely ended with respect

to the first grade during the school year commencing

13a

September 1963, and with respect to at least one suc

cessively higher additional grade each school year

thereafter. ’ ’

and, in lieu thereof, directs the District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama to enter the following para

graph as its judgment and o rder:

“ It is further ordered, adjudged and decreed that

said persons be and they are hereby required to sub

mit to this Court not later than August 19, 1963, a

plan under which the said defendants propose to make

an immediate start in the desegregation of the schools

of Mobile County, Alabama, which plan shall effec

tively provide for the carrying into effect not later

than the beginning of the school year commencing

September 1963 and thereafter of the Alabama

Pupil Placement Law as to all school grades with

out racial discrimination, including ‘the admission

of new pupils entering the first grade, or coming

into the County for the first time, on a nonracial

basis,’ Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 5

Cir., 1962, 306 F.2d 862, 869 (that opinion describes

such a plan which has been approved and is operat

ing in Pensacola, F lorida).”

As in the Birmingham decision, the order contem

plates a full hearing before the District Court. The

District Court will therefore go forward with the trial

already fixed for November 14, 1963.

Except to the extent expressly granted herein, the peti

tioners’ application for a rehearing is denied.

The Clerk is directed to issue the mandate, as amended,

forthwith.

Bele, Circuit Judge (concurring in part and dissenting

in part).

The modification by the majority of their prior order

in this case compounds error. Of course, I agree to the

14a

modification to the extent that it may alleviate disruption

of the educational process in Mobile during the 1963-1964

school term.

My understanding of this latest order is not altogether

clear. I t appears to simply require activation, under some

plan yet to he worked out, of the Alabama School Placement

Law which was adopted by the Legislature of that State

in 1957, and which was approved as constitutional on its

face in Shuttleworth [sic] v. Birmingham Board of Educa

tion, N.D.Ala., 1958, 162 F.Supp. 372, affirmed 358 U.S. 101,

79 S.Ct. 221, 3 L.Ed.2d 145. I t is not likely that any

appreciable amount of desegregation will take place under

that law at this late date. The protective measures

assured by Judge Lynne in the Armstrong case of a