University of Tennessee v. Elliott Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. University of Tennessee v. Elliott Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent, 1986. 3e3072ec-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/625caa80-670a-497c-86a3-742dc6a2435d/university-of-tennessee-v-elliott-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

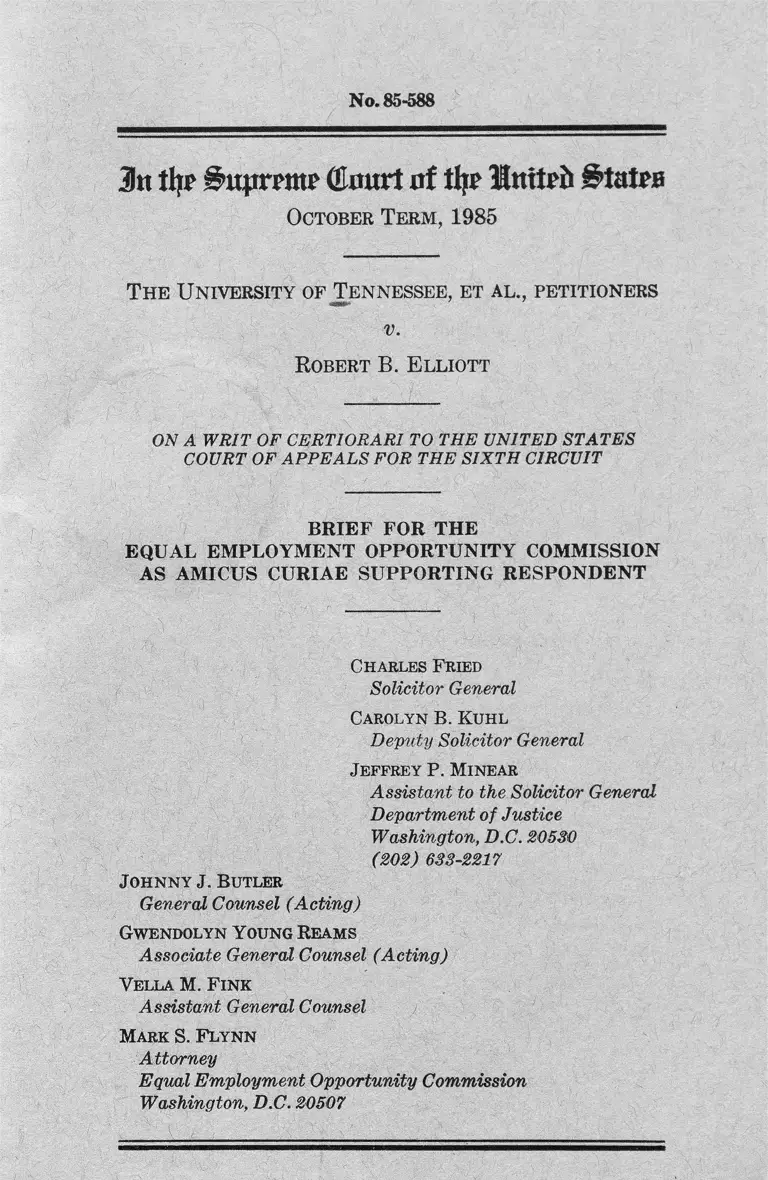

No. 85-588

3tt tljr §û trrmr (llmtrt of % llnttrii

October Term, 1985

The University of Tennessee, et al., petitioners

v.

Robert B. Elliott

ON A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENT

Charles Fried

Solicitor General

Carolyn B. Kuhl

Deputy Solicitor General

Jeffrey P. Minear

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

Johnny J. Butler

General Counsel (Acting)

Gwendolyn Y oung Reams

Associate General Counsel (Acting)

Vella M. Fink

Assistant General Counsel

Mark S. Flynn

Attorney

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Washington, D.C. 20507

QUESTION PRESENTED

This brief will address the following question:

Whether a federal court adjudicating a Title VII

action must give preclusive effect to a judicially un

reviewed decision of a state administrative agency

finding no employment discrimination.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest Of The Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission ...................... ................-........................................ 1

Statement ................ .............................................................. 2

Summary of argument ....................................................... 5

Argument:

A federal court adjudicating a Title VII action

should not give res judicata effect to a judicially

unreviewed decision of a state administrative

agency.......................................................................... . 8

I. The full faith and credit statute does not require

federal courts to give judicially unreviewed

state administrative decisions res judicata ef

fect ........................................... 8

II. A judicially fashioned rule giving res judicata

effect to state administrative decisions would be

inconsistent with Title VII..................................... 18

III. This Court has previously denied res judicata

effect to non-judicial decisions in Title VII ac

tions ...................................................... 22

IV. Petitioners’ suggested policy rationale for pre

clusion should not be substituted for Title VIPs

own requirements and policies....... .................... 25

Conclusion ............................................................... 29

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Alexander V. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36....7,19, 23,

24, 25, 26, 27

American Tobacco Co. V. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63.... 11

Batiste V. Furnco Construction Corp., 503 F.2d

447, cert, denied, 420 U.S. 928 .......... ................... 15, 21

Board of Governors v. Dimension Financial Corp.,

No. 84-1274 (Jan. 22, 1986) ........ ........................ 11

(ill)

IV

PageCases—Continued:

Bottini V. Sadore Management Corp., 764 F.2d

116 ............................................................................. 15

Bowen V. United States, 570 F.2d 1311.................... 18

Buckhalter V. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, Inc.,

768 F.2d 842, petition for cert, pending, No. 85-

6094 (filed Dec. 23, 1985) ................................ 12,16, 21

Burney V. Polk Community College, 728 F.2d 1374.. 12,15,

21

Chandler V. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840....7,19, 22, 23, 25, 27

Chatelain V. Mount Sinai Hospital, 580 F. Supp.

1414 ........................................................... - ........... 12

Clinton v. Georgia Ports Authority, 37 Fair. Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 593 ............................................. 15-16

Cooper V. Philip Morris, Inc., 464 F.2d 9 ------------- 15, 21

Davis v. Davis, 305 U.S. 3 2 ........................ ................ 0

Delamater V. Schweiker, 721 F.2d 50...... ................ 18

Gargiul v. Tompkins, 704 F.2d 661........................... 12

Garner v. Giarrusso, 571 F.2d 1330 ..................... 15, 20, 21

Gulf Oil Corp. V. FPC, 563 F.2d 588, cert, denied,

434 U.S. 1062............. 18

Heath v. John Morrell & Co., 768 F.2d 245 .......... . 15, 21

Holley V. Seminole County School District, 763

F.2d 399 ............................. 12

King v. City of Pagedale, 573 F. Supp. 309 ............ 12

Kremer V. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S.

461 ...............................................................................passim

Magnolia Petroleum Co. v. Hunt, 320 U.S. 430....... 11,12

McCulloch Interstate Gas Corp. V. FPC, 536 F.2d

9 10 .................................................................. ............ 18

McDonald V. City of West Branch, 466 U.S. 284..9,11,13

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792.... 7, 24

Migra v. Warren City School District Board of

Education, 465 U.S. 75......................................... - 4, 9

Mills v. Duryee, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 481................ 9

Mitchell V. Bendix Corp., 603 F. Supp. 920 ........... 15

Mitchell V. National Broadcasting Co., 553 F.2d

265 .............................................................................. 12

Mohasco Corp. V. Silver, 447 U.S. 807 ................... 14

Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799 ............................ 12,16, 26

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S.

54 ................................................................................ 26

O’Hara v. Board of Education, 590 F. Supp. 698,

aff’d mem., 760 F.2d 259..................................... . 12

Pacific Seafarers, Inc. V. Pacific Far East Line,

Inc., 404 F.2d 804, cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1093.... 18

Painters District Council No. 38 V. Edgewood Con

tracting Co., 416 F.2d 1081............................ 18

Parker V. Danville Metal Stamping Co., 603 F.

Supp. 182................................................................... 15

Parker V. National Corporation for Homing Part

nerships, 619 F. Supp. 1061, appeal docketed, No.

85-5985 (D.C. Cir. Oct. 4, 1985) __________ __ _ 12,16

Parsons Steel Co. V. First Alabama Bank, No. 84-

1616 (Jan. 27, 1986) ........ 9

Pettus v. American Airlines, Inc., 587 F.2d 627,

cert, denied, 444 U.S. 883 ....... ................. ............. 19

Pizzuto v. Perdue, Inc., 623 F. Supp. 1167............. 15

Reedy v. State of Florida, Dep’t of Education, 605

F. Supp. 172 ....................... ............ .......... ............... 15

Rosenfeld v. Department of Army, 769 F.2d 237.... 19

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759 F.2d

355 ................................................... 21

Thomas V. Washington Gas Light Co., 448 U.S.

261 ................................. ............'.......................... ...... 12

United Farm Workers v. Arizona Agricultural

Employment Relations Board, 669 F.2d 1249.... 19

United States v. Karlen, 645 F.2d 635 ................. 18

United States v. Locke, No. 83-1394 (Apr. 1,

1985) .............. 11

United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co.,

384 U.S. 394 ____________ _____ .....4-5,16, 17,18,19, 20

Voutsis v. Union Carbide Corp., 452 F,2d 889, cert.

denied, 406 U.S. 918 .....................................’......... 15

Zanghi V. Incorporated Village of Old Brookville,

752 F.2d 4 2 .................................... 12

Zywicki V. Moxness Products, Inc., 37 Fair Empl.

Prac Cas. (BNA) 710 ..................................... . 16

Constitution, statutes and regulations:

U.S. Const. Art. IV, § 1 (Full Faith and Credit

Clause) ..... ............................................................... . 8, 9

Act of May 26, 1790, ch. XI, 1 Stat. 122 et seq........ 11

V

Cases—Continued: Page

VI

Constitution, statutes and regulations— Continued: Page

Act of Mar. 27, 1804, ch. 56, 2 Stat. 298 et seq...... 11

Act of June 25, 1948, ch. 646, § 1738, 62 Stat. 947.. 11

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Tit. VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000e

et seq................................................. -......................... 1, 2

§ 706 (b ) , 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 ( b ) .................-1 , 6,13, 20

§ 706 (c ) , 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 ( c ) .........................6,10,13

§ 706 ( f ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 ( f ) ............. 13

§ 709 (b ) , 42 U.S.C. 2000e-8 (b) .......................... 26

Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. (1964 ed.) 1346(2) ............. 16

Wunderlich Act, 41 U.S.C. 321 ................................. 16,17

28 U.S.C. 1738................................................5, 6, 9,10,11,12

42 U.S.C. 1981.......... .............................................. ....... 2,5

42 U.S.C. 1983..............................................................2,15,16

42 U.S.C. 1985 ......................................................... ...... 2,5

42 U.S.C. 1986................................................................ 2,5

42 U.S.C. 1988 ........................................................... . 2, 5

Tennessee Uniform Administrative Procedures

Act, Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 4-5-101 et seq. (1985).. 2

§ 4-5-301................................................................. 3

§ 4-5-315............................................................... 3

§ 4-5-322............................................................... 3

29 C.F.R.:

Section 1601.13...................................................... 26

Section 1601.21 (e) ............................................ 13

Section 1601.76................................................... 13

Section 1601.77...................................................... 13

Section 1601.80........................................ 26

Miscellaneous:

Atwood, State Court Judgments in Federal Litiga

tion: Mapping the Contours of Full Faith &

Credit, 58 Ind. L.J. 59 (1982)............................ 11

Catania, Access to the Federal Courts for Title

VII Claimants in the Post-Kremer Era: Keep

ing the Doors Open, 16 Loy. L.J. 209 (1985).... 19-20

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) :

p. 7205 ................................................................... 27

p. 7214....................................... 27

VII

Miscellaneous— Continued: Page

4 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise (1983)- 11,19

E.E.O.C. Compl. Man. (CCH) (May 1985) ..... ...... 26

E.E.O.C. Dec. No. 86-4 (Dec. 6, 1985) .................... 16

H.R. Rep. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971)____ 23,24

Note, Res Judicata Effects of State Agency Deci

sions in Title VII Actions, 70 Cornell L. Rev.

695 (1985) ........................ 20

Restatement (Second) of Judgments (1982)...... 19

S. Rep. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ......... 23, 27

Symposium, Tennessee Administrative Law, 13

Mem. St. U.L. Rev. 461 (1983) ....... .................... 2

3n % i ’tqimttr (tort of % Imfrfr States

October T e r m , 1985

No. 85-588

T h e U n iv e r sity of T e n n e sse e , et a l ., pe titio n e rs

v.

R obert B. E llio tt

ON A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENT

INTEREST OF THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT

OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(EEOC) is the federal agency primarily responsible

for administering federal fair employment statutes,

including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq. Among other responsibilities,

it reviews employment discrimination determinations

by state fair employment practice (FEP) agencies in

accordance with Section 706(b) of Title VII. 42

U.S.C. 2000e-5(b). The EEOC believes that peti

tioners’ position in this case— urging that in adjudi

cating Title VII actions federal courts must give res

judicata effect to judicially unreviewed state agency

(1)

2

decisions— is inconsistent with Title VII, could under

mine private enforcement, and would interfere with

the EEOC’s exercise of its statutory responsibilities.1

STATEMENT

1. On December 18, 1981, petitioner University of

Tennessee notified respondent, a black employee of

the University’s Agricultural Extension Service, that

he would be discharged for inadequate job perform

ance and misconduct. Respondent filed an appeal of

the termination decision under the Tennessee Uni

form Administrative Procedures Act, Tenn. Code

Ann. §§4-5-101 et seq. (1985), which provides a

public employee with an administrative review of

his proposed discharge. Shortly thereafter, respond

ent filed suit against petitioners in the United States

District Court for the Western District of Tennessee,

alleging that the proposed termination was racially

motivated and therefore violated Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq.

Respondent also raised federal civil rights claims

under 42 U.S.C. 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986 and 1988.

The district court stayed the federal action pending

completion of respondent’s state administrative chal

lenge to the dismissal. See Pet. App. A1-A4.

An administrative law judge (ALJ) conducted the

state administrative proceeding.2 The ALJ dis

1 The EEOC takes no position on the preclusive effect of

state administrative agency decision in suits brought under

42 U.S.C. 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986 and 1988.

2 The state administrative review process is described by

the court of appeals (Pet. App. A4-A5). See generally Sym

posium, Tennessee Administrative Law, 13 Mem. St. U. L.

Rev. 461 (1983). It provides the basic elements of an ad

judicative procedure, including right to counsel, right to

request issuance of subpoenas and the right to examine and

8

claimed jurisdiction to adjudicate respondent’s affirm

ative claim for violation of his civil rights. However,

the ALJ concluded that he could consider respondent’s

allegations of employment discrimination as an af

firmative defense to the University’s charges of in

adequate job performance and misconduct (Pet. App.

A44-A45). After a lengthy hearing, the ALJ sus

tained four of the University’s eight claims of im

proper and inadequate performance (id. at A166-

A170), ruling further that respondent “ failed in his

burden of proof to the claim of racial discrimination

as a defense to the charges against him” (id. at

A177). The ALJ concluded, however, that respond

ent should be transferred rather than discharged (id.

at A177-A182).

Respondent, in accordance with Tennessee law, re

quested review of the ALJ decision by the appropri

ate University of Tennessee official. See Tenn. Code

Ann. § 4-5-315 (1985). That official, the Vice Presi

dent for Agriculture, sustained the ALJ’s ruling

(Pet. App. A33-A35). Neither petitioners nor re

spondent exercised their statutory right under Tenn.

Code Ann. § 4-5-322 (1985) to seek state court re

view (Pet. App. A6).

2. Following the state administrative decision, re

spondent renewed his federal court action. Petition

ers then moved for summary judgment, arguing, inter

alia, that under res judicata principles the state ad

ministrative finding of no discrimination precluded

respondent’s Title VII claims. The district court

granted petitioners’ motion, concluding that the ad-

eross-examine witnesses on the record. Under Tennessee law,

the ALJ must be an employee of either the affected state

agency or the secretary of state. See Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-

301 ( 1985) .

4

ministrative finding should be given preclusive effect

(Pet. App. A26-A32).3

The court of appeals reversed, holding that res

judicata principles did not bar respondent’s Title

VII action. It relied upon this Court’s decision in

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S.

461 (1982), which “ drew a sharp distinction between

state court judgments, which are entitled to defer

ence under the res judicata principles of [28 U.S.C.]

1738, and unreviewed state administrative determi

nations which are not.” Pet. App. A ll . The court

of appeals rejected petitioners’ contention that Krem-

er’s statements concerning the nonpreclusive effect

of state administrative decisions applied only to

agencies with investigative, rather than adjudica

tive, authority, noting that Kremer’s statements were

accompanied by citations to decisions involving state

adjudicative agencies (id. at A12).

The court of appeals also rejected petitioners’ con

tention that Kremer, by citing United States v. Utah

8 The preclusive effects of former adjudication “are referred

to collectively by most commentators as the doctrine of ‘res

judicata,’ ” which itself is often analyzed by reference to two

concepts: claim preclusion and issue preclusion. Migra V.

Warren City School District Board of Education, 465 U.S. 75,

77 n.l (1984). “ Claim preclusion refers to the effect of a

judgment in foreclosing litigation of a matter that never has

been litigated, because of a determination that it should have

been advanced in an earlier suit.” Ibid. “ Issue preclusion

refers to the effect of a judgment in foreclosing relitigation

of a matter that has been litigated and decided.” Ibid. In this

case, petitioners urge that issue preclusion should result from

the agency’s finding of no discrimination. Pet. Br. 26-27 n .ll.

In arguing that judicially unreviewed state administrative de

cisions should have no preclusive effect in Title VII actions,

we use the more general terms “preclusive effect” and “ res

judicata” throughout this brief.

5

Construction & Mining Co., 384 U.S. 394 (1966),

implicitly recognized that res judicata principles

should be applied to administrative agencies. The

court observed that Kremer’s sole reference to that

case occurred in the course of examining the ade

quacy, for due process purposes, of New York’s ju

dicial review procedures (Pet. App. A12-A13). The

court stated that “ [t]he district court’s holding that

[respondent’s] Title VII claim is barred by res ju

dicata must fall in light of the unambiguous prin

ciple enunciated in Kremer” (id. at A13) .4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This Court held in Kremer v. Chemical Construc

tion Corp., 456 U.S. 461 (1982), that the full faith

and credit statute, 28 U.S.C. 1738, requires that a

federal court adjudicating a Title VII action give

preclusive effect to a state court judgment affirming

a state administrative agency’s rejection o f an em

ployment discrimination claim. However, the Court

also stated that federal court resolution of a Title

VII claim is not precluded by unreviewed adminis

trative decisions “even if such a decision were to be

4 The court of appeals also held that the administrative

decision should not preclude respondent’s claims under 42

U.S.C. 1983, and by analogy, his claims under Sections 1981,

1985, 1986, and 1988. The court concluded that the full faith

and credit statute, 28 U.S.C. 1738, applies only to state court

judgments (Pet. App. A16) and that, therefore, the appropri

ate inquiry in this case was whether the federal courts should

create a federal common law rule according preclusive effect to

unreviewed administrative determinations when adjudicating

Section 1983 actions (Pet. App. A17). The court held that the

underlying policies of Section 1983 counselled against giv

ing state administrative determinations preclusive effect (id.

A19-A22).

6

accorded preclusive effect in a State’s own courts”

(456 U.S. at 470 n.7). Kremer’s reasoning controls

the present case. The federal courts may consider

respondent’s Title VII claim, notwithstanding a prior

state administrative determination, unreviewed by

the state courts, that petitioner did not engage in

employment discrimination.

Under Kremer, a federal court adjudicating a

Title VII claim must give the same preclusive effect

to a state court determination of employment dis

crimination that the determination would receive in

the state’s own courts. But as Kremer implicitly

recognized, the full faith and credit statute governs

only the res judicata effect of “ judicial proceedings

of any court” (28 U.S.C. 1738). It does not con

trol the res judicata effect of a state administrative

decision that received no review from the state’s

judiciary.

As Kremer also recognized, Title VII, in both its

structure and purpose, cannot be squared with a rule

giving preclusive effect to state administrative de

terminations. Section 706(c) of Title VII clearly

contemplates that the EEOC will often defer its ex

amination of a Title VII claim pending the state’s

fair employment practice (FEP) agency considera

tion of the dispute. See 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(c). And

Section 706(b) specifies that EEOC shall accord

substantial weight”— not preclusive effect—to the

FEP agency decision. 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(b). “ EEOC

review of discrimination charges previously rejected

by state agencies would be pointless if the federal

courts were bound by such agency decisions.”

Kremer, 456 U.S, at 470 n.7.

Petitioners concede that state FEP agency deter

minations may be nonpreclusive, but suggest that

7

preclusive effect should nevertheless be given to de

terminations by other state agencies that, in the

course of their administrative proceedings, address

employment discrimination claims. However, Kremer

drew no such distinction. The opinion specifically

cites court o f appeals decisions involving both FEP

and non-FEP agencies to illustrate the nonpreelusive

effect of state administrative determinations. Cer

tainly, Congress did not intend that the federal

courts, in implementing the important national pol

icy of non-discrimination, would be bound by findings

of various state non-FEP agencies with little or no

expertise in employment discrimination matters.

Indeed, this Court’s decisions have repeatedly rec

ognized that federal courts may give de novo con

sideration to Title VII claims notwithstanding prior

non-judicial decisions rejecting discrimination claims.

See Chandler v. Roudehush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976);

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974); McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973). For example, the Court held in Chan

dler that a federal court may adjudicate a federal

employee’s Title VII claim, notwithstanding the em

ploying agency’s prior administrative decision reject

ing the employee’s discrimination claim. Similar

principles should control the Title VII claims of non-

federal employees, including state and local employ

ees who contest their discharge through state ad

ministrative procedures that result in incidental ad

judication of employment discrimination claims.

Policy considerations also argue against applica

tion of “ administrative res judicata” in the Title

VII context. If state agency determinations of em

ployment discrimination are given preclusive effect,

claimants may choose to forego altogether state ad

8

ministrative procedures protecting important rights.

This result would weaken state administrative sys

tems, diminish state participation in employment dis

crimination issues, and harm the federal-state coop

eration achieved by worksharing agreements between

EEOC and FEP agencies. Furthermore, it would in

crease the workload of the federal courts and the

EEOC. The potential inefficiencies in nonpreclusion

are easily exaggerated. Claimants who have lost

their discrimination claims after a full hearing be

fore a state agency are likely to be circumspect in

seeking a full-scale federal adjudication. Further

more, federal review, when it does occur, should be

able to be conducted more expeditiously after an ad

ministrative proceeding. The issues generally have

been narrowed, the need for discovery should be less

ened, and the administrative record may be admitted

as evidence entitled to appropriate weight.

ARGUMENT

A FEDERAL COURT ADJUDICATING A TITLE VII

ACTION SHOULD NOT GIVE RES JUDICATA EF

FECT TO A JUDICIALLY UNREVIEWED DECISION

OF A STATE ADMINISTRATIVE AGENCY

I. The Full Faith and Credit Statute Does Not Require

Federal Courts to Give Judicially Unreviewed State

Administrative Decisions Res Judicata Effect

The Full Faith and Credit Clause empowers Con

gress to determine whether federal courts shall be

bound by state judicial proceedings.® Congress., in *

* The Full Faith and Credit Clause provides:

Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the

public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every

other State. And the Congress may by general Laws

9

turn, has enacted the full faith and credit statute,

28 U.S.C. 1738, which entitles the “ judicial proceed

ings of any court of any such State” to “ full faith

and credit” in the federal courts.® Section 1738 re

quires “ federal courts to give the same preclusive

effect to a state-court judgment as would the courts

of the State rendering the judgment.” McDonald v.

City of West Branch, 466 U.S. 284, 287 (1984).

Congress, through the full faith and credit statute,

has thus expressed a general federal respect for

state court decisions.* 6 7

This Court concluded in Kremer v. Chemical Con

struction Cory., 456 U.S. 461 (1982), that Congress

prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and

Proceeding’s shall be proved, and the Effect thereof.

U. S. Const. Art. IV, § 1. Congress, of course, is under

no obligation to give state proceedings binding effect in the

federal courts. See Kremer V. Chemical Construction Corp.,

456 U.S. 461, 483 n.24 (1982) ; Davis v. Davis, 305 U.S. 32, 40

(1938).

6 Section 1738 provides in pertinent part:

The records and judicial proceedings of any court of

any such State, Territory or Possession * * * shall be

proved or admitted in other courts within the United

States and its Territories and Possessions [upon proper

authentication].

Such * * * records and judicial proceedings * * * shall

have the same full faith and credit in every court within

the United States and its Territories and Possessions as

they have by law or usage in the courts of such State,

Territory or Possession from which they are taken.

7 See, e.g., Parsons Steel Co. V. First Alabama Bank, No. 84-

1616 (Jan. 27, 1986), slip op. 5; Migra V. Warren City School

District Board of Education, 465 U.S. 75, 81 (1984) ; Kremer

V. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461, 462-463, 466 n.6

(1982) ; Davis V. Davis, 305 U.S. 32, 40 (1938) ; Mills v.

Duryee, 11 U.S. (7 Crunch) 481 (1813).

10

intended that federal courts adjudicating Title VII

actions would give preclusive effect to state court

judgments affirming state administrative agency de

terminations o f employment discrimination claims.8

The Court determined that Title VII did not contain

an express or implied repeal of Section 1738’s re

quirement that “ all United States courts afford the

same full faith and credit to state court judgments

that would apply in the State’s own courts.” Kremer,

456 U.S. at 462-463. It found no “manifest incom

patibility between Title VII and § 1738” that would

demonstrate Congress’s intention “to override the

historic respect that federal courts accord state court

judgments.” 456 U.S. at 470-472.

The issue in the present case is whether federal

courts adjudicating Title VII actions must give pre

clusive effect to judicially unreviewed state admin

istrative determinations of employment discrimina

tion claims. The full faith and credit statute has no

application in this context. Section 1738, by its

express terms, applies only to the “ judicial proceed

ings of any court.” 28 U.S. 1738. Congress, by its

plain language, has given preclusive effect only to

8 The petitioner in Kremer had filed a religious discrimina

tion charge with the New York State Division of Human

Rights, a recognized state FEP agency entitled to deferral

under Section 706(c), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(c). The agency de

termined that there was no probable cause to believe that the

petitioner’s employer had engaged in religious discrimination

in violation of New York’s employment discrimination statute.

456 U.S. at 464. The petitioner then sought judicial review,

and the New York state courts affirmed the state agency’s

decision. Ibid. This Court concluded that the state court’s

affirmance of the state agency’s decision precluded petitioner

from raising an identical Title VII claim of religious dis

crimination.

11

state court judgments; Section 1738 does not extend

that effect to state administrative decisions.

The reference to “ any court” is express and un

ambiguous; there is little need to peer behind those

words and into the legislative history. See United

States v. Locke, No. 83-1394 (Apr. 1, 1985), slip op.

11; American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63

(1982). In all events, the legislative history con

firms that the term “ any court” refers to traditional

courts rather than administrative bodies.9 This Court

has never held that Section 1738 requires that fed

eral courts give res judicata effect to state admin

istrative determinations.10 Moreover, the lower fed-

9 The full faith and credit statute was first enacted in 1790.

See Act of May 26, 1790, ch. XI, 1 Stat. 122 et seq., and the

subsequent amendments have been minor; see Act of Mar.

27, 1804, ch. 56, 2 Stat. 298 et seq.-, Act of June 25, 1948, ch.

646, § 1738, 62 Stat. 947. See generally Atwood, State Court

Judgments in Federal Litigation: Mapping the Contours of

Full Faith & Credit, 58 Ind. L.J. 59, 66 n.36 (1982). Notably,

Congress chose the operative words “ any court” nearly 200

years ago, long before the appearance of administrative

agencies and notions of administrative res judicata. See 4

K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise §21.2 (1983). It is,

of course, immaterial that there are now state administrative

bodies that conduct quasi-judicial activities; the scope of Sec

tion 1738 is controlled by the intent of Congress at the time

of the statute’s enactment. See Board of Governors v. Dimen

sion Financial Corp., No. 84-1274 (Jan. 22, 1986).

10 This Court has held that Section 1738 does not apply to

collective bargaining arbitration because that dispute resolu

tion mechanism “ is not a ‘judicial proceeding.’ ” McDonald,

466 U.S. at 288. Petitioners suggest (Pet. Br. 23-24) that

Section 1738 should apply to state administrative proceedings,

quoting dicta from the plurality in Magnolia Petroleum Co. V.

Hunt, 32:0 U.S. 430, 443 (1943). The quoted statement, an

ambiguous passage from a subsequently criticized decision

12

era! courts generally have agreed that Section 1738

does not confer preclusive effect on state adminis

trative decisions.11

Thus, it is clear that the full faith and credit stat

ute, which held controlling importance in Kremer, has

no application in this case.

concerning the obligation among the states to give full faith

and credit to state workmen’s compensation programs, has no

controlling force in this case. See Thomas v. Washington Gas

Light Co., 448 U.S. 261, 280-286 (1980) (plurality opinion)

(suggesting that Magnolia Petroleum should be overruled).

111 Although the Sixth Circuit and the Seventh Circuit dis

agree whether federal courts adjudicating Title VII actions

should give preclusive effect to judicially unreviewed admin

istrative decisions, they do agree that Section 1738 cannot

resolve the issue. See Pet. App. A16 ; Buckhalter v. Pepsi-Cola

General Bottlers, Inc., 768 F.2d 842, 849 (7th Cir. 1985),

petition for cert, pending, No. 85-6094 (filed Dec. 23, 1985).

Other courts have either suggested or concluded that Section

1738 does not apply to administrative determinations. See, e.g.,

Holley v. Seminole County School District, 763 F.2d 399, 400

(11th Cir. 1985) ; Burney v. Polk Community College, 728

F.2d 1374, 1380 (11th Cir. 1984) ; Gargiul V. Tompkins, 704

F.2d 661, 666-667 (2d Cir. 1983) ; Moore V. Bonner, 695 F.2d

799, 800-801 (4th Cir. 1982) ; Mitchell V. National Broadcast

ing Co., 553 F.2d 265, 276 (2d Cir. 1977) ; Parker v. National

Corporation for Housing Partnerships, 619 F. Supp. 1061,

1064-1065 (D.D.C. 1985), appeal docketed, No. 85-5985 (D.C.

Cir. Oct. 4, 1985) ; Chatelain v. Mount Sinai Hospital, 580

F. Supp. 1414, 1417 (S.D.N.Y. 1984) ; King v. City of Page-

dale, 573 F. Supp. 309, 313 (E.D. Mo. 1983). Although several

courts have reached a contrary conclusion, their analysis of

Section 1738 is summary and does not withstand close scru

tiny. See Zanghi V. Incorporated Village of Old Brookville,

752 F.2d 42, 46 (2d Cir. 1985) ; O’Hara v. Board of Education,

590 F. Supp, 696, 701 (D.N.J. 1984), aff’d mem., 760 F.2d 259

(3d Cir. 1985).

13

II. A Judicially Fashioned Rule Giving Res Judicata

Effect to State Administrative Decisions Would Be

Inconsistent With Title VII

Since Congress has not required federal courts to

give full faith and credit to state administrative deci

sions, “ any rule of preclusion would necessarily be

judicially fashioned.” McDonald, 466 U.S. at 288.

But judicial creation of such a rule in Title VII cases

would conflict with the language and structure of

Title VII and would be inconsistent with this Court’s

past interpretation of that statute.

Title VII plainly contemplates that state adminis

trative proceedings will be used both as an initial en

forcement mechanism and as a means of achieving

non-judicial conciliation of Title VII disputes. Sec

tion 706(c) of Title VII gives states and localities

that have enacted equal employment legislation a pe

riod of up to 60 days to attempt resolution of dis

crimination claims arising within their boundaries.

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(c). Section 706(b) provides that

if the employee is dissatisfied with the state FEP

agency’s resolution of his claim, he may request the

EEOC to make an independent reasonable cause de

termination. 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(b). Section 706(b)

further specifies that EEOC shall accord “ substantial

weight”—-not preclusive effect— to the FEP agency

decision. Ibid. ; see also 29 C.F.R. 1601.21(e), 1601.76

and 1601.77.12 And Section 706(f) provides that once

these proceedings have been invoked and have failed

to resolve the dispute, the claimant may seek a judi

cial remedy. See 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f). Title VII

thus “give[s] state agencies an opportunity to redress

the evil at which the federal legislation was aimed,

12 Similarly, the EEOC does not give preclusive effect to any

administrative decisions of non-FEP state agencies.

14

and to avoid federal intervention unless its need [is]

demonstrated.” Mohasco Corp. v. Silver, 447 U.S.

807, 821 (1980) (footnote omitted). It plainly con

templates that the state agency may have the first

opportunity to address employment discrimination

claims. However, the statute’s provisions for further

federal review following a state agency’s decision

demonstrate that the agency’s decision is not entitled

to preclusive effect.

Kremer s analysis of the structure and purposes of

Title VII provides powerful support for this conclu

sion. Although the Court did not speak unanimously

in applying res judicata principles to state court

judgments, the full Court did agree that state ad

ministrative decisions are not entitled to preclusive

effect.13 The majority and dissenting opinions each

recognized that according res judicata effect to un

reviewed state administrative decisions would be

antithetical to Title VII’s statutory scheme and pur

poses. See 456 U.S. at 469-470; id. at 487 (Black-

mun, J., dissenting); id. at 511 (Stevens, J., dissent

ing).

The Court observed that the “congressional direc

tive that the EEOC should give ‘substantial weight’

to findings made in state proceedings” (456 U.S. at

470) could not be squared with a rule giving those

same findings judicially preclusive effect, stating that

“ EEOC review of discrimination charges previously

rejected by state agencies would be pointless if the

federal courts were bound by such agency decisions.”

18 See 456 U.S. at 470 n.7; id. at 487 (Blackmun, J., dissent

ing) (“ a state agency determination does not preclude a trial

de novo in federal district court) (emphasis in original) ; id.

at 508-509 (Stevens, J., dissenting) ( “ state agency proceed

ings will not bar a federal claim under Title VII” )-

15

456 U.S. at 470 n.7. The Court concluded that it is

not “plausible to suggest that Congress intended fed

eral courts to be bound further by state administra

tive decisions than by decisions of the EEOC” {ibid.),

stating further:

Since it is settled that decisions by the EEOC do

not preclude a trial de novo in federal court, it

is clear that unreviewed administrative deter

minations by state agencies also should not pre

clude such review even if such a decision were

to be afforded preclusive effect in a State’s own

courts.

Ibid.14 Most lower courts, like the court below, have

read Kremer as providing a bright-line distinction.

They have generally concluded that state court judg

ments resolving employment discrimination claims

are entitled to res judicata effect in accordance with

state law, while unreviewed state agency determina

tions will not preclude Title VII claims.15 16 This inter

pretation is both sensible and correct.

14 The Court cited a series of court of appeals decisions in

support of its conclusion. Gamer V. Giarrusso, 571 F.2d 1330

(5th Cir. 1978) ; Batiste V. Furnco• Construction Corp., 503

F.2d 447, 450 n.l (7th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 420 U.S. 928

(1975) ; Cooper v. Philip Morris, Inc., 464 F.2d 9 (6th Cir.

1972) ; Voutsis V. Union Carbide Corp., 452 F.2d 889 (2d Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 918 (1972).

16 See, e.g., Heath V. John Morrell & Co., 768 F.2d 245, 248

(8th Cir. 1985) ; Bottini V. Sadore Management Corp., 764

F.2d 116, 120 (2d Cir. 1985) ; Burney V. Polk Community

College, 728 F.2d 1374, 1379-1380 (11th Cir. 1984) ; Pizzuto

V. Perdue Inc., 623 F. Supp. 1167, 1174 (D. Del. 1985) ; Reedy

V. State of Florida, Dep’t of Education, 605 F. Supp. 172,

173-174 (N.D. Fla. 1985) ; Mitchell V. Bendix Corp., 603

F. Supp. 920, 922 (N.D. Ind. 1985) ; Parker V. Danville Metal

Stamping Co., 603 F. Supp. 182, 188 (C.D. 111. 1985) ; Clinton

16

Petitioners largely ignore Kremer’s specific discus

sion of the non-preclusive effect of unreviewed admin

istrative determinations in Title VII adjudications.

Instead, they rely on general principles of “ admin

istrative res judicata.” They maintain (Pet. Br. 25-

27) that res judicata principles generally require that

federal courts give preclusive effect to all state ad

ministrative adj udications.

This Court addressed the concept o f administrative

res judicata in United States v. Utah Construction &

Mining Co., 384 U.S. 394 (1966). That case involved

the interpretation of a federal government contract’s

dispute resolution provisions. The Court held that the

contract’s “ disputes clause,” which provided for

administrative resolution of contract controversies

through a federal agency’s board of contract appeals,

did not provide the exclusive means for resolving all

contract disputes; instead, the contractor could seek

judicial relief, as permitted by the Tucker Act and

Wunderlich Act, in certain circumstances (384 U.S.

at 403-418).16 The Court concluded, however, that

V. Georgia Ports Authority, 37 Fair Empl. Prae. Cas. (BNA)

593, 594 (S.D. Ga. 1985) ; see also Moore V. Bonner, 695 F.2d

799, 801 (4th Cir. 1982) (interpreting Kremer in a Section

1983 action) ; E.E.O.C. Dec. No. 86-4, at 5 (Dec. 6, 1985). But

see Buckhalter V. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, Inc., supra;

Parker V. National Corporation for Housing Partnerships,

supra; Zywicki V. Moxness Products, Inc., 37 Fair Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 710, 711 (E.D. Wis. 1985).

is The Tucker Act, at that time, gave the Court of Claims

jurisdiction over breach of contract actions. See 28 U.S.C.

(1964 ed.) 1346(2). The Wunderlich Act accords finality to

an agency decision “ in a dispute involving a question aris

ing under [a government] contract” unless the decision “ is

fraudulent [sic] or capricious or arbitrary or so grossly

erroneous as necessarily to imply bad faith, or is not sup

ported by substantial evidence.” 41 U.S.C. 321.

17

“'[b]oth the disputes clause and the Wunderlich Act

categorically state that administrative findings on

factual issues relevant to questions arising under the

contract shall be final and conclusive on the parties”

(384 U.S, at 419 (footnote omitted)). The Court

added (id. at 420):

[W]hen the Board of Contract Appeals has

made findings relevant to a dispute properly be

fore it and which the parties have agreed shall

be final and conclusive, these findings cannot be

disregarded and the factual issues tried de novo

in the Court of Claims when the contractor sues

for relief which the board was not empowered to

give.

Petitioners suggest (Pet. Br. 25-26) that Utah

Construction establishes a general rule requiring that

federal courts give res judicata effect to all state ad

ministrative determinations. Plainly, they read far

too much into that decision. Utah Construction ad

dressed the res judicata implications of a specific fed

eral agency’s factual determinations under a partic

ular statutory regime. While the Court noted that its

decision “ is harmonious with general principles of

collateral estoppel,” it specifically stated that “ the

decision here rests upon the agreement of the parties

as modified by the Wunderlich Act,” 384 U.S. at 421

(footnote omitted). The Court quite correctly gave

the board of contract appeals’ findings preclusive ef

fect in light of the parties’ contractual agreement to

resolve disputes through that agency and the specific

command of Congress— through the Wunderlich Act,

41 U.S.C. 321— that the agency’s findings would be

final.

Utah Construction indicates that in some circum

stances the federal court should give preclusive effect

18

to federal administrative determinations, see 384 U.S.

at 422, but it says nothing about application of ad

ministrative res judicata to state agency determina

tions.17 Furthermore, it indicates that the congres

17 The decision whether administrative res judicata is war

ranted necessarily depends upon the circumstances presented.

While petitioners cite (Pet. Br. 26 n.10) a series of cases

recognizing the principle of administrative res judicata, none

of those decisions support application of that principle in this

case. Most of these cases involve questions pertaining to the

preclusive effect of federal administrative decisions. Delamater

V. Schweiker, 721 F.2d 50, 53-54 (2d Cir. 1983) (administra

tive decision to award social security benefits was not binding

in subsequent agency adjudication) ; United States V. Karlen,

645 F.2d 635, 638 (8th Cir. 1981) (agency determination

that an Indian lessee breached lease could have issue preclu

sive effect in subsequent federal suit seeking damages for

lease breach) ; Bowen V. United States, 570 F.2d 1311 (7th Cir.

1978) (federal court adjudicating a federal tort claim must

give preclusive effect, as a matter of state law, to a federal

agency finding that plaintiff violated federal aviation rules) ;

Gulf Oil Corp. V. FPC, 563 F.2d 588, 603 & n.17 (3d Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1062 (1978) (declining to decide

whether an agency must give collateral estoppel effect to its

own prior determinations) ; McCulloch Interstate Gas Corp.

V. FPC, 536 F.2d 910, 913 (10th Cir. 1976) (agency factual

determinations are binding in a subsequent agency proceed

ing) ; Painters District Council No. 38 v. Edgewood Contract

ing Co., 416 F.2d 1081, 1083-1084 (5th Cir. 1969) (agency

decision holding that union violated one section of a federal

labor relations statute is binding in federal court action seek

ing damages under another section of the statute) ; Pacific

Seafarers, Inc. V. Pacific Far East Line, Inc., 404 F.2d 804,

810 (D.C. Cir. 1968), cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1093 (1969)

(agency determination plaintiffs were not engaged in “ foreign

commerce” under one statute did not bar a federal court from

inquiring whether plaintiffs engaged in “ foreign commerce”

under another statute). The other decisions involved the

preclusive effect that state and District of Columbia adminis-

19

sional intent underlying the particular federal statu

tory regime at issue is central to the res judicata in

quiry. Id. at 421 n.18.18 In Utah Construction, the

Wunderlich Act supported an inference that preclu

sion was appropriate in the context of government

contract disputes. As Kremer demonstrates, the

structure and purposes of Title VII support an op

posite inference in the context of employment dis

crimination disputes. 456 U.S. at 469-470; id. at 487-

489 (Blaekmun, J., dissenting); id. at 511 (Stevens,

J., dissenting) ,19

trative bodies must accord the decision of another state ad

ministrative body. United Farm Workers V. Arizona Agricul

tural Employment Relations Board, 669 F.2d 1249, 1255 (9th

Cir. 1982) (declining to determine whether a state labor

agency’s decision is a “ judgment” entitled to full faith and

credit by another state) ; Pettus V. American Airlines, Inc.,

587 F.2d 627 (4th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 883

(1979) (holding that a state workmen’s compensation agen

cy’s determination that employee was unjustified in refusing

medical treatment was binding upon a District of Columbia

workmen compensation board).

118 See also, e.g., Chandler V. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840, 861-

862 (1976); Restatement (Second) of Judgments §83(3)

and (4) (1982) (administrative res judicata is inappropriate

where “the scheme of remedies permits assertion of the

second claim notwithstanding the adjudication of the first

claim” or where application “ would be incompatible with a

legislative policy” ) ; 4 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise

§21.5 (1983).

19 See also, e.g., Chandler V. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840, 844-

861 (1976) ; Alexander V. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36,

47-54 (1974) ; Rosenfeld v. Department of Army, 769 F.2d

237, 240 (4th Cir. 1985) ; 4 K. Davis, supra, § 21.5, at 62 ( “ The

best example [of a statute embodying a policy against admin

istrative res judicata] may be Title VII.” ) ; Catania, Access

to the Federal Courts for Title VII Claimants in the Post-

20

Petitioners acknowledge (Pet, Br. 33-34) that Sec

tion 706(b) of Title VII instructs the EEOC to give

“ substantial weight” to final findings and orders of

state FEP agencies when reviewing employment dis

crimination claims, 42 U.S.C. 200Qe-5(b). They

grudgingly concede (Pet, Br, 34) that Title VII

“ could be construed” to permit federal de novo review

of state administrative decisions. However, they sug

gest (ibid.) that federal courts should nevertheless be

required to give preclusive effect to decisions by non-

PE P agencies.

Petitioners’ position, which finds no support in Ti

tle VII precedent, is untenable. This Court, recogniz

ing in Kremer that unreviewed state agency decisions

are non-preclusive, did not distinguish between FEP

and non-FEP agencies. Indeed, the Court supported

its conclusion by citing, among other cases, Garner v.

Giarrusso, 571 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1978), a decision

denying preclusive effect to a non-FEP agency.20

------- i-------------- j—

Kremer Era: Keeping the Doors Open, 16 Loy. L,J. 209

(1985) ; Note, Res Judicata Effects of State Agency Decisions

in Title VII Actions, 70 Cornell L. Rev. 695 (1985). Notably,

while Kremer cited Utah Construction for the proposition that

New York courts could, consistent with due process, give

deference to administrative fact-finding, 456 U.S. at 484 n.26,

it nowhere suggested that federal courts would be bound by

unreviewed state administrative determinations.

00 The facts in Garner are very similar to those in the in

stant case. The plaintiff, a city employee, had raised charges

of racial discrimination before the New Orleans Civil Service

Commission. That agency conducted an administrative hear

ing to assure that the plaintiff “ had in fact breached police

department regulations and had been dismissed for that rea

son and not because of racial discrimination.” 571 F.2d at

1336. The court, following a careful analysis of administra

tive res judicata, concluded that the administrative decision

was not entitled to preclusive effect. See id. at 1335-1338.

21

Since Kremer, other courts of appeals have refused

to draw that distinction.121

Furthermore, petitioners’ position is inconsistent

with Title VII’s statutory scheme. It would lead to

the perverse result that federal courts must give pre

clusive effect to decisions by non-FEP agencies— which

likely have little expertise in employment discrimina

tion matters* 22— while according only “ substantial

weight” to decisions by the states’ expert FEP agen

cies. Certainly Congress, did not intend that the fed

eral courts, in implementing the important national

81 See Heath v. John Morrell & Co., 768 F.2d at 248; Burney

V. Polk Community College, 728 F.2d at 1379-1380. Notably,

the lone court of appeals in conflict with the decision below,

Buckhalter V. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, Inc., supra, relied

on a different theory— apparently abandoned by petitioners—

to give preclusive effect to a state agency determination. The

court reasoned that administrative res judicata was appropri

ate because the state agency in that case acted in an “ adjudica

tive,” rather than an “ investigative” capacity (768 F.2d at

854). That theory, like petitioners’ theory, is infirm. It fails

to recognize the important policy interests supporting federal

de novo review in Title VII actions. In addition, Kremer’s

statements on the non-preclusive effect of state agency deter

minations were accompanied by citations to three cases—

Garner, Batiste V. Furnco Construction Corp., 503 F.2d 447

(7th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 420 U.S. 928 (1975), and

Cooper V. Philip Morris, Inc., 464 F.2d 9 (6th Cir. 1972) —

that refused to provide preclusive effect to the decisions of

adjudicatory agencies.

22 In this case the non-FEP agency was a state educational

institution that was authorized by statute to conduct a hear

ing in response to a public employee’s claim of wrongful dis

charge. Other non-FEP agencies likely to address employ

ment discrimination claims include state and local civil service

commissions (see, e.g., Gamer V. Giarrusso, supra) and state

unemployment compensation agencies (see, e.g., Ross V. Com

munications Satellite Corp., 759 F.2d 355 (4th Cir. 1985)).

22

policy of nondiscrimination, would be bound by find

ings of the various state non-FEP agencies with little

or no expertise in employment discrimination mat

ters.

III. This Court Has Previously Denied Res Judicata Effect

to Non-Judicial Decisions in Title VII Actions

This Court, recognizing the special role of the fed

eral courts in adjudicating Title VII claims, has re

peatedly refused to give res judicata effect to employ

ment discrimination determinations by non-judicial

entities. There is no reason to depart from those

precedents in this case.

This Court’s decision in Chandler v. Roudehush,

425 U.S. 840 (1976), is particularly relevant. The

Court concluded that a federal court must provide a

de novo adjudication of a federal employee’s Title VII

claim, notwithstanding the decisions of the Civil Serv

ice Commission and the employing agency rejecting

the employee’s charges.23 The Court stated (id. at

848):

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments

[to Title VII] reinforces the plain meaning of

the statute and confirms that Congress intended

to accord federal employees the same right to

a trial de novo as is enjoyed by private-sector

employees and employees of state governments

and political subdivisions under the amended

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

28 In Chandler, a Veterans Administration employee alleg

ing sex and race discrimination received a hearing before the

agency’s complaints examiner, followed by review within the

agency and subsequent review by the Civil Service Commis

sion. 425 U.S. at 842. The hearing was conducted as an

adversarial adjudication. See id. at 863; see also 74-1599 Pet.

App. la-17a; 74-1599 J.A. 15-44.

23

As this passage suggests, Congress intended that all

employees, whether federal, state, or private-sector,

would be entitled to a trial de novo in federal court

despite their exercise of other federal and state ad

ministrative remedies. That symmetry, recognized in

Chandler, should be respected here. Congress plainly

did not intend that a federal employee would be en

titled to a trial de novo following an unsuccessful

administrative adjudication before his employing

agency, but a state employee, such as respondent,

should be denied a trial de novo based on the res

judicata effect of an analogous administrative ad

judication before his employing agency.24

This Court’s decision in Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974), reflects a similar

principle. The Court concluded that a federal court

adjudicating a union employee’s Title VII claim

should not give preclusive effect to a prior arbitral

decision rejecting the discrimination charge.25 The

Court rejected the notion that the employee’s pursuit

of his collective bargaining agreement remedy rep

resented an election of remedies and waiver of his

Title VII claim, noting that “ [tjhere is no suggestion

24 Notably, Congress perceived that the “ ‘entrenched dis

crimination in the Federal Service’ ” (Chandler, 425 U.S. at

841, quoting, H.R. Rep. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 24

(1971)) also existed in the state and local civil service. See

H.R. Rep. 92-238, suq>ra, at 17-18; S. Rep. 92-415, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. 9-11 (1971).

35 The employee had filed a grievance under the collective

bargaining agreement alleging that he was improperly dis

charged (415 U.S. at 39), ultimately claiming that his termi

nation was racially motivated (id. at 42). The grievance pro

ceeded to arbitration. The arbitrator ruled that the discharge

was for “ just cause,” making no reference to the claim of

racial discrimination (ibid.).

24

in the statutory scheme that a prior arbitral decision

either forecloses an individual’s right to sue or di

vests federal courts of jurisdiction.” 415 U.S. at 47.

The Court stated that “ in general, submission of a

claim to one forum does not preclude a later submis

sion to another” (id. at 47-48 (footnote omitted)), spe

cifically observing that “ [f]o r example, Commission

action is not barred by the ‘findings and orders’ of

state or local agencies” (id. at 48 n.8). The parallels

between Alexander and the present case are apparent.

It would be incongruous if a union employee is en

titled to pursue his Title VII remedy in federal court

despite an adverse decision under the arbitration pro

visions of his collective bargaining agreement, but a

state employee is precluded from pursuing his Title

VII remedy by an adverse decision under state ad

ministrative proceedings governing review of dis

charge decisions. See also McDonnell Douglas Corp.

v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 798-799 (1973) (holding that

an EEOC finding of no reasonable cause does not pre

clude federal de novo review of a discrimination

claim).26

In short, this Court has recognized that “ Title VII

manifests a congressional intent to allow an individ

ual to pursue independently his rights under both

Title VII and other applicable state and federal stat-

26 Notably, petitioners rely on arguments similar to the

“ election of remedies” argument rejected in Alexander, sug

gesting (Pet. Br. 33) that respondent can preserve his Title

VII remedy by foregoing his state administrative remedies.

As Alexander explains, 415 U.S. at 47-54, an employee should

not be forced to make that choice. “ Title VII was envisioned

as an independent statutory authority meant to provide an

aggrieved individual with an additional remedy to redress

employment discrimination.” H.R. Rep. 92-238, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. 18-19 (1971).

25

utes.” Alexander, 415 U.S. at 48 (footnote omitted).

That principle is applicable in the present case. Re

spondent, a state employee, should be free to pursue

his state law remedies in the state administrative

forum without foreclosing his independent Title VII

remedy.

IV. Petitioners’ Suggested Policy Rationale for Preclusion

Should Not Be Substituted for Title VIPs Own Re

quirements and Policies

Petitioners suggest (Pet. Br. 41-42) various policy

considerations favoring application of res judicata to

the state administrative determination in this case.

However, those considerations, even if valid, are ir

relevant. Congress has determined that federal courts

adjudicating Title VII claims should not give pre

clusive effect to judicially unreviewed state admin

istrative decisions. That determination controls the

present case. Furthermore, even if the weighing of

policy interests were appropriate, they would counsel

against giving preclusive effect to judicially unre-

viewed administrative decisions.

Petitioners suggest that preclusion is necessary to

protect the “ integrity of the adjudicatory process

which the State of Tennessee has provided for the

purpose of protecting Fourteenth Amendment inter

ests affected by agency action” (Pet. Br. 41). How

ever, this Court rejected similar arguments made with

respect to federal administrative processes (see

Chandler, 425 U.S. at 863-864) and collective bar

gaining agreements (see Alexander, 415 U.S. at 55-

60). Indeed, petitioners’ position quite likely would

actually hamper the effectiveness of state administra

tive mechanisms for resolving employment disputes.

Claimants, faced with the prospect that an adverse

2 6

decision from a state administrative agency would

preclude a Title VII claim, might frequently choose to

avoid or abandon state proceedings. That result

“would undermine Congress’ intent to encourage full

use of state remedies.” New York Gaslight Club, Inc.

v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 65, 66 n.6 (1980); see Alex

ander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. at 59; cf.

Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799, 802 (4th Cir. 1982).

That result, in addition, would likely increase the

workload of the federal courts and the EEOC, since

they would be required to review discrimination

claims without the benefit of the prior state agency

examination. It also could upset the division of labor

between the EEOC and state FEP agencies currently

achieved through worksharing arrangements.27

Petitioners suggest that nonpreclusion will “bur

den the federal court with needlessly relitigating an

issue already fully litigated” (Pet. Br. 41). How

ever, the legislative history of Title VII suggests

that Congress favored judicial resolution of discrim

ination claims. For example, when Congress amended

27 The Commission has entered into worksharing agree

ments, pursuant to Section 709(b) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

2000e-8(b), with many of the state FEP agencies that en

force state and local laws. See E.E.O.C. Compl. Man. (CCH)

HIT 281, 282 (May 1985) ; 29 C.F.R. 1601.13, 1601.80 (listing

certified deferral agencies). Under these agreements, certain

categories of discrimination charges are processed by state

authorities; with respect to other categories, the state FEP

agency often waives its right under the statute to initiate re

view and EEOC processes the charge from the outset. When

the state agency processes the charges under this arrange

ment, EEOC generally takes no action “ until the [FEP

agency] issues its final findings and orders or otherwise

terminates its proceedings.” E.E.O.C. Compl. Man. (CCH)

][ 284 (May 1985).

27

Title VII in 1972, congressmen suggested that ju

dicial resolution of employment discrimination claims

might be preferable to EEOC adjudicatory deter

minations because it would promote public confi

dence that fair employment laws were being enforced

in an independent and even-handed manner. See S.

Rep. 92-415, supra, at 85 (views of Sen. Dominick);

see also Kremer, 456 U.S. at 474 n.15.28 And as the

court below noted (Pet. App. A21), “ there are sig

nificant differences between the state judicial and

administrative forums that counsel against federal

court deference to the decisions of the latter even

though Congress has required deference to the deci

sions of the former.”

In all events, the potential inefficiencies in nonpre

clusion are easily exaggerated. Claimants who have

lost their discrimination claims after a full hearing

are likely to be circumspect in seeking a full-scale

federal readjudication. Furthermore, federal court

litigation following administrative adjudication gen

erally should be able to be foreshortened. The prior

proceedings have typically narrowed the issues, less

discovery is likely to be needed, and the federal court

is able to consider the administrative record as evi

dence entitled to appropriate weight. See Chandler,

425 U.S. at 863 n.39; cf. Alexander, 415 U.S. at 60

n.21.

Finally, we note that Kremer’s distinction between

state courts and state agencies for purposes of Title

VII res judicata is straightforward and easy to apply.

28 Indeed, when Congress first enacted Title VII, congress

men expressed concern regarding the adequacy and effective

ness of state remedies and procedures. See 110 Cong. Rec.

7205 (1964) (Sen. Clark) ; id. at 7214 (Clark-Case interpre

tive memorandum).

28

By contrast, any attempt to apply res judicata prin

ciples based on the identity or character of the agency

will inevitably generate confusion.2® Difficult ques

tions will arise as to whether a state agency in a

given case has acted in an adjudicatory capacity

within the meaning of “administrative res judicata”

and whether it has applied standards, in reaching its

finding, consistent with Title VII. Furthermore, un

wary claimants may not receive judicial de novo

consideration because they were unaware that entry

into an adjudicatory phase of a state system could

lead to a; binding administrative decision.

In sum, Kremer’s bright line distinction between

the preclusive effect of state court judgments and the

nonpreclusive effect of judicially unreviewed admin

istrative determinations is both legally sound and

practicable. The court of appeals correctly deter

mined that the state’s administrative determination

rejecting respondent’s claim of employment discrim

ination did not preclude respondent’s Title VII action.

529 The confusion will be particularly pronounced where

federal-state worksharing agreements are in effect. Many

claimants’ charges are processed to completion by state agen

cies, rather than the EEOC, simply because the charges were

administratively allocated to the state FEP agency by the

worksharing agreement.

29

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals, insofar as it

declines to accord preclusive effect in respondent’s

Title VII action to a judicially unreviewed state ad

ministrative determination, should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted.

Charles Fried

Solicitor General

Carolyn B. Kuhl

Deputy Solicitor General

Jeffrey P. Minear

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Johnny J. Butler

General Counsel (Acting)

Gwendolyn Y oung Reams

Associate General Counsel (Acting)

Vella M. Fink

Assistant General Counsel

Mark S. Flynn

Attorney

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

March 1986

☆ U . S . GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE; 1 9 8 6 4 0 1 5 0 7 2 0 1 6 8