NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Harrison Petition for Appeal

Public Court Documents

February 5, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Harrison Petition for Appeal, 1960. 4076513a-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/628c7390-5c56-49bd-8659-bfb3c17b31e8/naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-v-harrison-petition-for-appeal. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

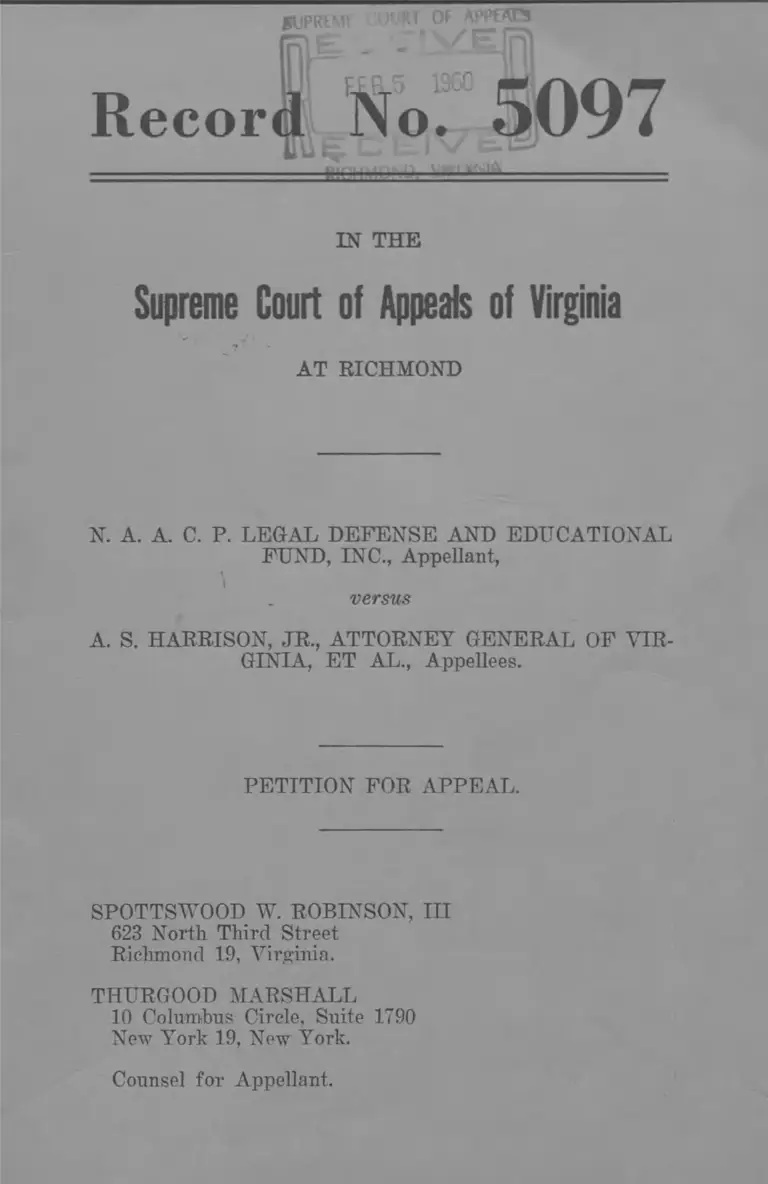

Record No. 5097

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

AT RICHMOND

N. A. A. C. P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., Appellant,' \

\

versus

A. S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY GENERAL OF VIR

GINIA, ET AL., Appellees.

PETITION FOR APPEAL.

SPOTTSWOOD W. ROBINSON, III

623 North Third Street

Richmond 19, Virginia.

THURGOOD MARSHALL

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 1790

New York 19, New York.

Counsel for Appellant.

INDEX TO PETITION

Record No. 5097.

Page

Petition For Appeal ............................................................ 1*

Statement of Material Proceedings in the Lower Court .. 2*

Errors Assigned .................................................................... 4*

Questions Involved in the Appeal ..................................... 7*

Statement of the Facts ........................................................ 9*

Appellant’s Constitutional Contentions in the Federal

Forum: Chapters 33 and 36 Abridge Freedoms of

Expression And Association And Violate The Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses Of The Four

teenth Amendment ........................................................ 13*

A. The Offenses Created By Chapters 33 and 36

Are Defined So Broadly That Activities Related

To The Exercise Of First Amendment Freedoms

Are Made Criminal ................................................ 14*

B. The Offenses Provided For Under Chapters 33

and 36 Are Framed So As To Amount To A

Denial Of Due Process Of Law ......................... 19*

C. Chapters 33 and 36 Violate The Due Process

Clause Of The Fourteenth Amendment Because

They Fetter Access To The Federal Courts .. 22*

D. Chapters 33 and 36 Violate The Due Process

Clause Of The Fourteenth Amendment Because

They Are Infringements On Liberty ................. 24*

E. Chapter 36 Legalizes A Long List Of Maintenous

Activities And Resultingly Violates The Equal

Protection Of The Law ......................................... 26*

Argument ............................................................................... 28*

Neither Chapter 33 Nor Chapter 36, Properly Con

strued In The Light Of Appellant’s Constitutional

Contentions Under Settled Rules Of Statutory Con

struction, Can Properly Be Construed To Prohibit

The Activities Of Appellant Which The Court Below

Held To Be Inhibited Thereby ................................. 28*

A. The Statutes Involved ........................................... 28*

1. Chapter 33 ................. 29*

2. Chapter 3d ........................................................ 30*

B. The Court Below Failed To Apply Well Settled

Rules of Statutory Construction In Declaring

Chapters 33 and 3*6 To Apply To And Prohibit

The Activities Of Appellant Involved On This

Appeal ....................................................................... 31'

C. Chapters 33 And 36 Should Xot Be Construed To

Apply To Or Prohibit The Activities Of Appel

lant Which Were Declared Violative Thereof .. 36*

1. Appellant’s Activities Declared To Be Vio

lative Of Chapter 33 Do Not Amount To An

Improper Solicitation Of Legal Or Pro

fessional Business Or Employment Within

The Meaning Of That Chapter When Prop

erly Construed In The Light Of Appellant’s

Constitutional Contentions Under Settled

Rules of Statutory Construction ................. 38*

2. Appellant’s Activities Declared To Be Vio

lative Of Chapter 36 Do Not Amount To An

Inducement To Commence Or Prosecute Law

Suits Within The Meaning Of That Chapter

When Properly Construed In The Light Of

Appellant’s Constitutional Contentions Un

der Settled Rules Of Statutory Construction . 46*

Conclusion ............................................................................. 50*

Page

Prayers ........................................................................... 50*

Request For Oral Argument ..................................... 50*

Adoption Of Petition As Opening Brief On Appeal . 50*

Certificate Of Mailing Of Copies Of Petition To

Opposing Counsel ........................................................ 50*

Certificate As To Parties On Appeal ............................. 51*

Certificate Of Opinion As To Review ............................. 51*

Table of Citations.

Cases.

Ades, In Re: 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. C. Md.) . . . .16*, 17*, 25*,

45*, 49*

Adkinson v. School Board of City of Newport Neivs, 3

Race Rol. L. Rep. 938 .................................................... 23*

Aetna Bldg. Maintenance Co. v. West, 246 P. (2d) 11

(C a l .) '............................................................................... 41*

Air-Way Electric Appliance Corp. v. Day, 266 U. S. 71 . 26*

Alex Foods v. Metcalf, 37 Cal. App. (2d) 415, 290 P. (2d)

646 ................................................................................... 41*

Page

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

Va., 249 F. (2d) 462, cert, denied 355 U. S. 953,

motion for further relief denied in part 164 F. Supp.

786, reversed F. (2d) (decided May 5, 1959) .......... 22*

Allen v. School Board of Charlottesville, 1 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 886, affirmed 240 F. (2d) 59, cert, denied 353

U. S. 910, motion for further relief granted 3 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 937, 938, appeal dismissed 4 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 39 ....................................................................... 23*

American Communication v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382 .......... 15*

Andetrson v. Commonwealth, 182 Va. 560, 29 S. E. (2d)

838 ................................................................................... 32*

Atkins v. School Board of City of Newport News, 148 F.

Supp. 430, ruling on merits 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 334,

affirmed 246 F. (2d) 325, cert, denied 355 U. S. 855

sub nom. Adkins on v. School Board of City of New

port News, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 938 ......................... 23*

Barbier v. Connelly, 113 U. S. 27 ..................................... 23*

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ..................................... 14*

Bartels v. Iowa, 262 U. S. 404 ......................... '.............. 25*

Beckett v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 148 F. Supp.

430, decided on the merits 2 Race Rel. Rep. 337 af

firmed 246 F. (2d) 325, cert, denied 355 IT. S. 855,

motion for further relief granted 3 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1155, affirmed 260 F. (2d) 18 .................................... 23*

Bigelow v. Old Dominion Copper Mining & Smelting Co.,

74 N. J. Eq. 457, 71 A. 153 .................................16*, 17*

Brannon v. Stark, 185 F. (2d) 871 (D. C. Cir.) .......... 16*

Brewer v. Iloxie School Dist. No. 46, 238 F. (2d) 91

(8th Cir.) ........................................................................ 14*

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294 ................................................................................... 22*

Brush v. Cafbondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N. E. 252 .............. 16*

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ..................................... 14*

Campbell v. Third District Committee, 179 Va. 244, 18

S. E. (2d) 883 ................................................................ 42*

Chester H. Roth, Inc. v. Esguide, Inc., 186 F. (2d) 11

(2nd Cir.) ........................................................................ 21*

Chreste v. Commonwealth, 171 Ky. 77, 186 S. W. 919 . . . . 19*

City of Bridgeport v. Equitable Title & Mortgage Co.,

106 Conn. 542, 138 A. 452 ........................... ..'...16* , 17*

City of Houston v. Jas. K. Dobbs Co., 232 F. (2d) 428

(5th Cir.) ........................................................................ 14*

Commonwealth v. Armour & Co., 118 Va. 242, 87 S. E.

610, a ff’d. 246 U. S. 1 .............................................34*, 36*

Commomvealth v. Carter, 126 Va. 469, 102 S. E. 58 . . . . 34*

Commomvealth v. Dodson, 176 Va. 281, 11 S. E. (2d)

120 ................................................................................... 34*

Commonwealth v. Dupuy, 4 Clark 1, 6 Pa. Law J. 223 .16*, 17*

Commomvealth v. Maclin, 3 Leigh (30 Va.) 809 .......... 33*

Commonwealth v. Mason, 175 Pa. Super. 576, 106 A.

(2d) 877 ........................................................................... 46*

Concordia Fir'e Insurance Co. v. Illinois, 292 U. S. 535 .. 26*

Cone v. Ivinson, 4 Wyo. 203, 35 P. 933 ......................... 49*

Cotting v. Kansas City Stock Yards Co., 183 U. S. 79 .. 28*

Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. (U. S.) 36 ......................... 23*

Davies v. Stowell, 78 Wis. 334, 47 N. W. 370 ..........16*, 20*

Davis v. Commomvealth, 17 Grat. (58 Va.) 617 ....2 3 * , 33*

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward\ County,

Va., 103 F. Supp, 337, reversed 347 U. S. 483, re

manded 349 U. S. 249, decree on remand 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 82, motion for further relief referred to one-

judge District Court 142 F. Supp. 616, motion for

further relief denied 149 F. Supp. 431, reversed

sub nom. Allen v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, Va., 249 F. (2d) 462, cert, denied

355 U. S. 953, motion for further relief denied in

part 164 F. Supp. 768, reversed F. (2d) (decided

Page

May 5, 1959) ................................................................. 22*

Doughty v. Grills, 260 S. W. (2d) 379 (Tenn.) ........... 19*

Elliott’s K. I. S. & C. Corp. v. State Corporation Commis

sion, 123 Va. 63, 96 S. W. (2d) 353 ......................... 32*

Faulkner v. South Boston, 141 Va. 517, 127 S. E. 380 .. 32*

Follett v. McCormick, 321 U. S. 573 ................................. 19*

Fonden v. Parker, 11 Mees & W. 75 ................................. 20*

Frost v. Paine, 12 Me. (3 Fairf.) I l l ............................. 16*

Gibson v. Gillespie, 4 W. W. Harr. (Del.) 331, 152 A.

589 ................................................................................... 20*

Government & C. E. O. C., CIO v. Windsor, 353 U. S.

364 ................................................................................... 13*

Gowen v. Nowell, 1 Me. (1 Greenl.) 292 ........................ 16*

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 125 E. (2d)

cno o n * A A *

Hannabass v. Ryan, 164 Va. 519, 180 S. E. 416 . .32*, 34*, 35*

Harrison v. National Asso. for A. C. P., U. S. (decided

June 8, 1959) ....................... ............................13*. 15*, 41*

Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection & Insurance Co. v.

Harrsion, 301 U. S. 459 .....................................26,* 27*

Hildebrand v. State Bar, 18 Cal. (2d) 816, 117 P. (2d)

860 ................................................................................... 41*

Huahes v. Van B rug (fen, 44 N. M. 534, 105 P. (2d) 494 .. 48*

In B e: Ades, 6 F.'Supp. 467 (D. C. M d .)....16* , 17*, 25*

45*, 49*

In Re: Mitgang, 385 111. 311, 52 N. E. (2d) 807 .......... 19*

In R e : Newell, 174 App. Div. 94, 160 X. Y. S. 275 .......... 19*

Jahn v. Champagne Lmmber Co., 157 F. 407 (D. C.

Wis.) ....................................................................... 20*, 21*

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 123 ....................................................................... 14*

Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, 4 Race Rel. 31,

33 23*

Jordon v. South Boston, 138 Ya. 838, 122 S. E. 265 .. 32*

Kelley v. Boyne, 239 Mich. 204, 214 N. W. 3 1 6 .............. 19*

Kilby v. County School Board of Warren County, unre

ported (decided Sept. 8, 1958), affirmed 259 F. (2d)

497 ................................................................................... 23*

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252 .. 25*

La Page v. United States, 146 F. (2d) 536 (8th Cir.) .. 46*

Lewis v. Commonwealth, 184 Va. 69, 34 S. E. (2d) 389 .. 32*

Matthews v. Commonwealth, 18 Grat. (59 Va.) 989 .. 33*

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eijek, 297 U. S. 266 ....2 6 * , 28*

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107 ............................. 42*, 45*

McIntyre v. Thompson, 10 F. 531 (C. C. N. C.) ............. 20*

McKay v. Commonwealth, 137 Va. 826, 120 S. E. 138 .. 32*

Meyers v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 ................................... 25*

Miller v. Commonwealth, 172 Va. 639, 2 S. E. (2d)343 34* 35*

Millhiser Mfg. Co. v. Galleqo, 101 Va. 579, 44 S. E. 760 .. 33*

Mitgang, In Re: 385 111. 311, 52 N. E. (2d) 807 .............. 19*

Mobile & 0. R. Co. v. Etheridge, 84 Tenn. (16 Lea) 398 .. 16*

Mor’ey v. Loud, 354 U. S. 457 . . ......................... 26*, 27*, 28*

Morthland v. Lincoln National Life Ins. Co., 220 Ind. 692,

42 N. E. (2d) 41 .............................................................. 47*

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105 ......................... 19*

N. A. A. C. P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (D. C. Va.),

vacated sub nom Harrison v. National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People, IT. S.

(decided June 8, 1959) .................................14*, 36*, 41*

Nash v. Douglass, 12 Abb. Prac. N. S. 187 (N. Y.) . .41*, 42*

National Asso. For The A. C. P. v. Alabama, 367 U. S.

449 ....................................................................13*, 15*, 41*

Newell, In R e : 174 App. Div. 94, 160 N. Y. S. 275 . . . . 19*

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 IT. S. 536 ......................................... 26*

Norfolk & W. Ry. Co., v. Virginia Ry. Co., 110 Va. 631,

66 S E 863 ............................... 33* 34*

Nye & Niss'en v. United States, 168 F. (2d) 846 .......... 49*

O’Connor v. Smith, 188 Va. 214, 49 S. E. (2d) 310 . . . . 32*

People v. Ficke, 343 111. 367, 175 N. E. 543 ............ 41*, 47*

People v. Gray, 52 Cal. App. (2d) 620, 127 P. (2d) 72 .. 20*

People v. Grout, 38 Misc. 181, 77 N. Y. S. 321 ................. 47*

People v. Juskoivitz, 173 Misc. 685, 18 N. Y. S. (2d)

897 ................................................................................... 46*

People v. Levy, 8 Cal. App. (2d) 763, 50 P. (2d) 509 .. 41*

Page

People v. Lewis, 365 111. 156, 6 N. E. (2d) 175 ....4 1 * , 47*

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 5 1 0 ................. 14*, 25*

Rahke v. State, 168 Ind. 615, 81 N. E. 584 ..................... 46*

R e: Shay, 133 App. Div. 547, 118 N. Y. S. 146, a ff’d.

196 N. Y. 530, 89 N. E. 1112....................... 19*

Richmond A ss ’n. of Credit Men v. Bar Association, 167

Va. 327, 189 S. E. 153 .........................................17*, 42*

Royal Oak Drain Dist. v. Keefe, 87 F. (2d) 786 (6th

Cir.) ................................................................................. 16*

Sampliner v. Motion Picture Patents Co., 255 F. 242 (2nd

Cir.) ................................................................................. 20*

Sandefur-Julian Co. v. Stake, 72 Ark. 11, 775 AY. 506 .. 41*

School Board v. Patterson, 111. A7a. 482, 69 S. E. 337 .. 36*

Schwahe v. Estes, 202 Mo. App. 372, 218 S. AV. 908 . . . . 46*

SchwaYe v. Board of Bar Examiners of the State of Neiv

Page

Mexico, 353 U. S. 232 ................................................ 25*

Seattle T. & T. Co. v. Seattle, 86 AVasli. 594, 150 P. 1134 .. 41*

Sellers v. Dies. 198 Va. 49, 92 S. E. (2d) 486 .............. 32*

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IT. S. 535 ................................. 26*

Slaughter House Cases, 16 AA7all. (U. S.) 36 ................. 23*

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 IT. S. 553 .................................26*, 27*

Snider v. Wimberly, 327 Mo. 491, 209 S. AY. (2d) 239 .. 48*

Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400 .............. 26*

Sp'ector Motor Service v. O’Connor, 340 U. S. 602, rev’g.

181 F. (2d) 150 (2nd Cir.) and aff’g. 88 F. Supp. 711

(I). C. Conn.) ................................................................ 13*

Sped or Motor Service, Inc. v. Walsh, 15 Conn. Sup. 205

aff’d. in part and rev’d. in part 135 Conn. 37, 61 A.

(2d) 89 ............................................................................ 13*

State v. Brown, 143 AA7is. 405, 127 N. AA7. 956 ........... 46*

State v. Fraker, 148 Mo. 143, 49 S. AY. 1017 ........... 47*

State v. Franco, 76 Utah 202, 289 P. 100 .................... 47*

State v. Nye, 56 AVkly. Bull. 273 (Ohio) ............... 41*

State ex rel. Nebraska Bar A ss’n. v. Basye, 138 Nebr.

806, 295 N. AV. 816 ........................................................ 19*

iState ex re?. Wright v. Hinckle, 137 Nebr. 735, 291 N. AA7.

68 ............. '....................................................................... 19*

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ......................................... 22*

Sweezv v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 ..........13*, 15*, 18*

Terrell v. Burke Construction Co., 257 IT. S. 529 .......... 23*

Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. S. 516 ..................................... 15*

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 144 F. Supp. 239, affirmed 240 F. (2d) 59, cert,

denied 353 IT. S. 911, motion to amend decree granted

2 Pace Rel. L. Rep. 810, motion for further relief

granted 159 F. Supp. 767, affirmed 252 F. f2d) 929,

cert, denied 356 IT. S. 958, motion for further relief

denied in part 166 F. Supp. 529, affirmed in part 263

F. (2d) 226, remanded 264 F. (2d) 946 ..............22*, 23*

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 . . . ......................... 14*, 23*, 26*

United States v. C. I. 0., 335 U. S. 106 .................... 18*

United States v. Haxriss, 347 U. S. 612 ................... 15*

United States v. Lancaster, 44 F. 885 (C. C. Ga.) _ 23*

United States v. Rumley, 345 U. S. 4 1 ....................... 18*

Urick v. Appeal Board, 325 Mich. 599, 39 N. W. (2d) 85 .. 41*

Village of Scribner v. Mohr, 90 Nebr. 21, 132 N. W. 734,

Ann. Cas. 1912D, 1287 ................................................ 41*

Vitaphone Corp. v. Hutchison Amusement Co., 28 F.

Supp. 526 (D. C. Mass.) ................................................ 16*

Waller v. Commomvealth, 192 Va. 83, 63 S. E. (2d) 713 .. 32*

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 ................. 15*, 18*

Wiernan v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 .............................14*, 18*

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ................................. 26*

Constitutions.

Constitution of the United States:

Page

First Amendment............................................ 14*, 15*, 45*

Fourteenth Amendment ..2*, 13*, 14*, 15*, 22*, 23*

24*, 28*, 45*, 49*

Statutes.

Colorado Rev. Stat., Sec. 40-7-41 ..................................... 20*

Illinois Stats. Anno., Chap. 38, Sec. 66 ......................... 20*

Virginia Acts of the General Assembly, Extra Session 1956:

Chapter 31 ...................................................................... 2*

Chapter 32 ...................................................................... 2*

Chapter 33 . . . .1 * , 2#, 3*, 4*, 5*, 6*, 7*, 8*, 13*, 14*

15*, 18*, 19*, 22*, 23*, 25*, 27*, 28*,

29*, 31*, 32*, 34*, 36*, 37*, 38*, 39*,

40*, 41*, 42*, 46*, 46*

Chapter 35 ................................................................2*, 36*

Page

Chapter 36 . . . .1 * , 2*, 3*, 5*, 6*, 7*, 8*, 13*, 14*, 15*,

18*, 19*, 20*, 22*, 23*, 24*, 25*, 26*,

27*, 28*, 29*, 30*, 31*, 32*, 34*, 36*,

37*, 38*, 46*, 47*, 49*

Virginia Code (1950):

Secs. 18-349.9 to 18-349.30 ......................................... 2*

Secs. 18-349.31 to 18-349.37 ......................................... 1*

Section 54-74 ..................... 1*, 19*, 28*, 29*, 38*, 39*

Section 54-78 ..................... 1*, 19*, 28*, 29*, 30*, 38*, 39*

Section 54-79 ......................... 1*, 19*, 29*, 30*, 38*, 39*

Section 54-82 ............................................................ 30*, 32*

United States Code:

Page

Title 28, See. 1343(3) ................................................ 24*

Title 42, Sec. 1983 ........................................................ 24*

Other Authorities.

American Bar Association:

Canons of Professional Ethics, Canon 35 ....1 7 * , 25*,

42*, 45*

Opinions of the Committee on Professional Ethics

(1957) ........................................................17*, 43*, 45*

American Jurisprudence:

Volume 5, pp. 425-426 .......................................... 19*, 20*

Volume 10, p. 549 .................................................. 21*, 22*

Association of the Bar of the City of New York & New

York County Lawyers’ Association, Opinions of the

Committee on Professional Ethics (1956) . ...15*-16*,

17*, 18*

Blackstone’s Commentaries, Vol. 4, p. 135 ..................... 20*

Brownell, Legal Aid in the United States (1951) ..18*, 21*

Cohen, “ The Origins of the English Bar,” 81 Law Q.

Rev. 5 6 ............................................................................. 21*

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23(2) (3) . . . . 18*

McGuire, “ Poverty and Civil Litigation,” 36 Harv. L.

Rev. 361........................................ 21*

Miehie’s Jurisprudence, Vol. 17, p. 320 ......................... 42*

Mirrors of Justices, 7 Sel. Soc. 14 (1893) ..................... 21*

New York Times, Sept. 8, 1957, p. 118 ............................. 22*

Radin, “ Maintenance by Champerty,” 24 Cal. L. Rev. 48

(1935) ................. *.................... ' ..................................... 21*

Rules of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, Rule

5 :12(d) . . . .................................................... 38*

Schlesinger, “ Biography of a Nation of Joiners,” 50 Am.

Hist. Rev. 1 (1944)'........................................................ 15*

Schlesinger, Crisis of the Old Order (1957) ............. 15*, 21*

Smith, Justice and the Poor (1921) ......................... 18*, 22*

Winfield, “ The Historv of Maintenance and Champ

erty,” 35 Law Q. Rev. 50 (1919) ............................. 20*

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

AT RICHMOND

Record No. 5097

N. A. A. C. P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED, Appellant,

versus

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY GENERAL

OF VIRGINIA, T. GRAY HADDON, COMMON

W EALTH ’S ATTORNEY FOR THE CITY OF RICH

MOND, VIRGINIA, WILLIAM L. CARLETON, COM

MONWEALTH’S ATTORNEY FOR THE CITY OF

NEWPORT NEWS, VIRGINIA, LINWOOD B. TABB,

COMMONWEALTH’S ATTORNEY FOR THE CITY

OF NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, WILLIAM J. HASSAN,

COMMONWEALTH’S A T T O R N E Y FOR THE

COUNTY OF ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA, AND FRANK

N. WATKINS, COMMONWEALTH’S ATTORNEY

FOR THE COUNTY OF PRINCE EDWARD, VIR

GINIA, Appellees.

PETITION FOR APPEAL.

To the Honorable Judcfes of the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia:

Appellant, N. A. A. C. P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Incorporated, respectfully represents that it is ag

grieved by a final order of the Circuit Court of the City of

Richmond, Virginia, entered on February 25, 1959, declaring

that Chapters 33 and 36 of the Acts of the General Assembly

of Virginia, Extra Session of 1956 (Sections 54-74, 54-78,

54-79, as amended, and Sections 18-349.31 to 18-349.37, in-

elusive, of the Code of Virginia of *1950), construed and

2* interpreted in the light of the constitutional contentions

theretofore made by appellant in the United States Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond

Division, in the action styled “ N. A. A. C. P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Incorporated, v. Kenneth. C. Patty,

Attorney General for the Commomvealth of Virginia, et al.,”

being Civil Action No. 2436, viz., that enforcement of such

statutes would infringe rights secured by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, apply to and pro

hibit certain of the customary activities of appellant, its

officers, members, contributors, voluntary workers, and at

torneys employed or retained by it or to whom it may con

tribute monies or services.

A transcript of the record in this case is herewith pre

sented.

STATEMENT OF MATERIAL PROCEEDINGS IN THE

LOWER COURT.

This suit was brought in the Circuit Court of the City

of Richmond, for a judgment declaratory of the construction

of the aforesaid statutes as they may affect appellant, its

officers, members, contributors or voluntary workers, or at

torneys retained or employed by it or to whom it may con

tribute monies, because of appellant’s activities in the past

or the continuance of like activities in the future, in the light

of appellant’s contentions that enforcement of these statutes

would deny it, its officers, members, contributors or voluntary

workers, or attorneys retained or employed by it or to whom

it may contribute monies, their liberty and property without

due process of law and the equal protection of the laws

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of

the United States.

On November 29, 1956, appellant had instituted in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia, Richmond Division, Civil Action No. 2436, seeking,

on the constitutional grounds summarized above, a declara

tory judgment as to, and an injunction restraining the en

forcement of, Chapters 31, 32 and 35 (Va. Code 1958 Supp.,

Sees. 18-349.9 to 18-349.30), as well as Chapters 33 and 36

here involved, of the Acts of the General Assembly

3* *of Virginia, Extra Session 1956 (PI. Ex. R., p. 2).

Thereafter, following a hearing of this case along with

a similar case brought by another organization, the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the

2 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 3

Court held that Chapters 33 and 36 were too vague and

ambigious to warrant decision as to their constitutionality

prior to their construction by the Virginia courts (159 F.

Supp. 503; PL Ex. R-7) and entered judgment retaining juris

diction as to Chapters 33 and 36 for a reasonable time “ pend

ing the determination of such proceedings in the state courts

as the plaintiffs may see fit to bring to secure an interpreta

tion of these two statutes” and providing that “ plaintiffs

may petition this Court for further relief if at any time they

deem it their best interest so to do” (PI. Ex. R., p. 8).

Accordingly, on May 20, 1958, appellant initiated the in

stant case for a declaratory judgment construing Chapters

33 and 36 in the light of the constitutional objections pre

sented to the District Court and prayed for an adjudication

as to whether either of said statutes, properly construed in

the light of those constitutional contentions under settled

rule of statutory construction, applies to or prohibits ap

pellant’s activities. The appellees having answered, this

case was tried on November 10-12, 1958, together with a

similar suit brought by the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People. On January 21, 1959, the

Circuit Court rendered an opinion and on February 25, 1959,

entered a final order declaring, inter alia:

4. That the following enumerated activities of complain

ants, and those persons or attorneys connected with them,

when conducted in the manner shown by the evidence in these

cases, amount to either an improper solicitation of legal or

professional business or employment within the provisions

of Chapter 33 or an inducement to commence or prosecute

law suits within the prohibitions contained in Chapter 36,

or both, whether conducted separately or in conjunction with

the permitted activities hereinbefore mentioned:

A. Contribution to any person or group, of advice respect

ing his or its legal rights in a matter, case or proceeding in

volving an issue of racial segregation or discrimination or any

other issue.

4* *B. Expending of monies to defray the costs and ex

penses, in whole or in part, of litigation involving an

issue of racial segregation or discrimination, or any other

issue.

C. Assisting litigants in such litigation, cases or proceed

ings by persuading them to express and assert legal riadits

by receiving or accepting assistance in the nature of advice

and monies, within the contemplation of A & B above.

D. Contributions to any person or group, of monies toward

4 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

counsel fees and other expenses of litigation or the services

of attorneys in a matter, case or proceeding involving an

issue of racial segregation or discrimination, or any other

issue.

5. That the following enumerated activities of attorneys,

when conducted in the manner shown by the evidence in

these cases, amount to a violation of the provisions of Chap

ter 33:

E. (1) Acceptance by an attorney of assistance from the

complainants in the form of legal advice, monies toward

counsel fees and other expenses of litigation in a matter,

case or proceeding involving an issue of racial segregation

or discrimination, or any other issue.

(2) Acceptance by an attorney of employment by a person

or group for the purposes of rendering legal service to such

person or group in a matter, case or proceeding in which

either complainant has furnished or will furnish assistance

in the nature of advice, monies toward counsel fees and other

expenses within the contemplation of subparagraphs A, B

and D of paragraph 4 and E (1) above.

(3) Acceptance by an attorney of employment by either

complainant for purposes of rendering legal services to a

person or group desiring his service in a matter, case, or

proceeding involving an issue of racial segregation or dis

crimination, or any other issue.

6. That those activities prohibited to either of the com

plainants are likewise prohibited to the complainants’ affili

ates, officers, members, attorneys, voluntary workers, or

others within the control of complainants; * * *

On April 21, 1959, appellant’s notice of appeal and assign

ments of error were filed in said Court.

ERRORS ASSIGNED.

Appellant submits that the order appealed from is er

roneous in the following particulars:

5# *First: The Court erred in declaring that contribu

tion by an attorney employed or retained by, or associ

ated with, appellant of advice to a person or group, respect

ing his or its legal rights in a matter, case or proceeding in

volving an issue of racial segregation or discrimination

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 5

amounts to either an improper solicitation of legal or pro

fessional business or employment within the provisions of

Chapter 33, or an inducement to commence or prosecute law

suits within the prohibitions contained in Chapter 36, or both,

for the reason that neither of said statutes, properly con

strued in the light of appellant’s constitutional contentions

under settled rules of statutory construction, applies to or

prohibits said activities.

Second: The Court erred in declaring that the expendi

ture of monies by appellant to defray the costs and expenses,

in whole or in part, of litigation involving an issue of racial

segregation or discrimination amounts to either an improper

solicitation of legal or professional business or employment

within the provisions of Chapter 33, or an inducement to

commence or prosecute law suits within the prohibitions

contained in Chapter 36, or both, for the reason that neither

of said statutes, properly construed in the light of appellant’s

constitutional contentions under settled rules of statutory

construction, applies to or prohibits said activities.

Third: The Court erred in declaring that assistance by

appellant, its officers, members or voluntary workers, or at

torneys employed or retained by, or connected with it, to

litigants in litigation, cases or proceedings involving an issue

of racial segregation or discrimination by persuading them

to express and assert legal rights by receiving or accepting

assistance in the nature of advice respecting their legal

rights therein and monies to defray the costs and expenses

thereof amounts to either an improper solicitation of legal

or professional business or employment within the provisions

of Chapter 33, or an inducement to commence or prosecute

law suits within the prohibitions contained in Chapter 36,

or both, for the reason that neither of said statutes, properly

construed in the light of appellant’s constitutional conten

tions under settled rules of statutory construction, applies to

or prohibits said activities.

6* ^Fourth : The Court erred in declaring that contribu

tions by appellant to a person or group of monies to

ward counsel fees and other expenses of litigation or of the

services of attorneys in a matter, case or proceeding in

volving an issue of racial segregation or discrimination

amounts to either an improper solicitation of legal or pro

fessional business or employment within the provisions o f

Chapter 33, or an inducement to commence or prosecute law

suits within the prohibitions contained in Chapter 36, or both,

for the reason that neither of said statutes, properly con

strued in the light of appellant’s constitutional contentions

under settled rules of statutory construction, applies to or

prohibits said activities.

F ifth : The Court erred in declaring that acceptance by

an attorney of assistance from appellant in the form of legal

advice, monies toward counsel fees and other expenses of

litigation in a matter, case or proceeding involving an issue

of racial segregation or discrimination amounts to a viola

tion of the provisions of Chapter 33, for the reason that

said statute, properly construed in the light of appellant’s

constitutional contentions under settled rules of statutory

construction, does not apply to or prohibit said activities.

Sixth: The Court erred in declaring that acceptance by

an attorney of employment by a person or group for the

purpose of rendering legal services to such person or group

in a matter, case or proceeding involving an issue of racial

segregation or discrimination wherein appellant has fur

nished or will furnish assistance in the nature of advice re

specting his or its legal rights therein, or monies toward

counsel fees or costs and other expenses thereof, amounts to

a violation of the provisions of Chapter 33, for the reason

that said statute, properly construed in the light of appel

lant’s constitutional contentions under settled rules of statu

tory construction, does not apply to or prohibit said activities.

Seventh: The Court erred in declaring that acceptance

by an attorney of employment by appellant for the purpose

of rendering legal services to a person or group desiring his

services in a matter, case or proceeding ‘ involving an

7* issue of racial segregation or discrimination amounts to

a violation of the provisions of Chapter 33, for the

reason that said statute, properly construed in the light of

appellant’s constitutional contentions under settled rules of

statutory construction, does not apply to or prohibit said

activities.

QUESTIONS INVOLVED IN THE APPEAL.

Presented for consideration and decision are the following

questions:

First: Does the contribution of advice by an attorney em

ployed or retained by, or associated with, appellant to a

person or group, who requests or whose attorney requests the

advice, in a matter, case or proceeding involving an issue of

racial segregation or discrimination amount to either an

improper solicitation of legal or professional business or em

ployment within the provisions of Chapter 33 or an induce

ment to commence or further prosecute law suits within the

6 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

prohibitions of Chapter 36, or both, properly construed in

the light of appellant’s constitutional contentions under

settled rules of statutory construction?

Second: Does the expenditure of monies by appellant to

defray in whole or in part the costs and expenses of litigation

involving an issue of racial segregation or discrimination

when the litigant therein, or his attorney, has requested such

financial assistance amount to either an improper solicita

tion of legal or professional business or employment within

the provisions of Chapter 33 or an inducement to commence

or further prosecute law suits within the prohibitions of

Chapter 36, or both, properly construed in the light of ap

pellant’s constitutional contentions under settled rules of

statutory construction?

Third: Does the contribution of the services of an at

torney employed or retained by, or associated with, appellant

to a person or group, who requests or whose atttornev re

quests the services, in a matter, case or proceeding involving

an issue of racial segregation or discrimination amount to

either an improper solicitation of legal or professional busi

ness or employment within the provisions of Chapter 33 or

an inducement to commence or further prosecute laAv suits

within the prohibitions of Chapter 36, or both, properly con

strued in the light of appellant’s constitutional contentions

under settled rules of statutory construction?

8* *Fourth: Does advocacy by appellant that persons

subjected to racial segregation or discrimination assert

their legal rights in appropriate litigation and, at the re

quest of such persons or their attorneys, its contribution of

legal advice, or the services of an attorney, or monies toward

defraying the expenses of the litigation, amount to either an

improper solicitation of legal or professional business or

employment within the provisions of Chapter 33 or an in

ducement to commence or further prosecute law suits within

the prohibitions of Chapter 36, or both, properly construed

in the light of appellant’s constitutional contentions under

settled rules of statutory construction?

Fifth : Does acceptance by an attorney of assistance from

appellant in the form of legal advice or monies toward coun

sel fees and other expenses of litigation in a matter, case or

proceeding involving an issue of racial segregation or dis

crimination amount to a violation of the provisions of Chap

ter 33 when properly construed in the light of appellant’s

constitutional contentions under settled rules of statutory

construction?

Sixth: Does acceptance by an attorney of emplovment by

a person or group for the purpose of rendering legal services

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 7

8

in a matter, case or proceeding involving an issue of racial

segregation or discrimination where appellant has contri

buted or will contribute, at the request of the litigant or his

attorney, assistance in the form of advice respecting the

litigant’s legal rights therein or monies toward counsel fees

and other expenses thereof amount to a violation of the pro

visions of Chapter 33 when properly construed in the light of

appellant’s constitutional contentions under settled rules of

statutory construction ?

Seventh: Does acceptance by an attorney of employment

or retainer by, or association with, appellant for the purpose

of rendering legal services to a person or group requesting

appellant’s assistance in a matter, case or proceeding involv

ing an issue o f racial segregation or discrimination amount

to a violation of the provisions of Chapter 33 when properly

construed in the light of appellant’s constitutional contentions

under settled rules of statutory construction1?

9* ‘ STATEMENT OF THE FACTS.

Pursuant to stipulation of counsel the Circuit Court ad

mitted in evidence the record of the proceedings in the federal

court, see pp. 2-3, ante, and all evidence material to the issues

i-aised below and involved in this appeal is contained in the

transcript of the trial proceedings in that case (Tr., pp. 5-17;

see Tr., pp. 364-365). Eeferences to that transcript are cited

as “ PI. Ex. K-9, p. . ” Neither appellant nor appellees in

troduced additional evidence as to the character and activi

ties of appellant as to the matters now before this Court.

Appellant, hereinafter sometimes referred to as the

“ Fund,” is now and since March 20, 1940, has been a non

profit membership corporation incorporated under the laws

of the State of New York; and it is now, and since October

30, 1956, has been duly authorized by the State Corporation

Commission to function as a foreign corporation in Virginia

for the following principal purposes:

(a) To render legal aid gratuitously to such Negroes as

may appear to be worthy thereof, who are suffering legal

injustices by reason of race or color and unable to employ

and engage legal aid and assistance on account of poverty.

(b) To seek and promote the educational facilities for

Negroes who are denied the same by reason of race or color.

(c) To conduct research, collect, collate, acquire, compile

and publish facts, information and statistics concerning

educational facilities and educational opportunities for Ne

groes and the inequality in the educational facilities and

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

educational opportunities provided for Negroes out of public

funds; and the status of the Negro in American life.

This charter was approved by a New York Court without

objection from any of the several bar associations so that the

Fund thereby obtained the right under New York law to

operate as a legal aid society (PI. Ex. 1 with complaint;

PI. Ex. R-9, p. 311).

The Fund is governed by a Board of Directors which,

under its charter, consists of not less that five and not more

than fifty members (PL Ex. 1 with complaint; PI. Ex. R-9,

p. 252) and is headed by the usual executive officers (PI. Ex.

R-9, p. 252). It operates from an office in New York

10* City its only #office (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 252-253); it has

no affiliated or subordinate units (PI. Ex. R-9, p. 252).

The Fund has pursued its authorized corporate objectives

in Virginia and elsewhere by conducting research and col

lecting, collating and compiling facts, information and statis

tics concerning the extent of racial segregation and discrimi

nation, the lack of scientific basis therefor, and the benefits

of desegregation to humanity and governments, state and

federal; by compiling scientific data upon racial and other

minority discrimination within the United States; by obtain

ing legal research from lawyers, law school professors and

others in the field of constitutional law, with particular re

ference to civil rights of individuals; by rendering, upon

request, legal aid and assistance to litigants seeking redress

for denial of civil rights by reason of race or color, where the

litigant is financially unable to bear the cost of the litigation;

and by informing citizens, through public meetings, speeches,

lectures and other media as to their legal rights (PI. Ex.

R-9, pp. 258, 267-268). It has contributed monies, legal serv

ices, data, and the results of expert studies in a large number

of civil rights cases litigated both within and without Vir

ginia, including nearly every major litigation since 1940 in

volving a question of the validity of governmental action

predicated upon race (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 258-262). By virtue

of its efforts to secure equal rights and opportunities in the

United States, the Fund has come to be regarded as an im

portant instrument through which individuals may act in their

efforts to combat unconstitutional color restrictions and it

occupies a unique position as the only organization gratuit

ously providing such assistance and services on a national

basis (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 258-262, 274, 278-a, 318). In con

formity with its charter, the Fund does not attempt to in

fluence legislation by propanganda or otherwise (PI. Ex. R-9,

p. 257).

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Attv. Gen. of Va. 9

10 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

In the prosecution of this program the Fund employs a

full-time staff of attorneys in its office in New York City, en

gages on an annual retainer basis five additional attorneys

outside of New York, including one in Richmond, Virginia,

engages local attorneys for investigation, research and other

legal services in particular cases, and utilizes the volun-

11* tary services *of approximately a hundred lawyers and

a number of social scientists serving without compensa

tion throughout the United States, some of whom are in the

State of Virginia (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 252, 254, 258-262, 265-268,

270, 284, 320).

The Fund derives all of its revenue from contributions

solicited from individuals and corporations in Virginia and

elsewhere (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 277-a-277-b). There are no mem

bership dues (PI. Ex. R-9, p. 277). One of its committees,

known as the Committee of One Hundred, consisting of promi

nent persons who have joined together for the purpose of

raising the money necessary to keep the organization func

tioning, sends out letters four times a year throughout the

country (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 277-b, 279). A smaller source of

revenue consists in contribution soliciting at small luncheons

and dinners (PL Ex. R-9, p. 277-b). Most of the money

comes from small contributions, but some monies are received

from charitable foundations, the largest of which was $15,-

000.00 and the aggregate of which is less than $50,000.00

a year (Pl. Ex. R-9, pp. 283-284).

Since 1954 the Fund’s income rose steadily until 1956 when

it dropped to $351,283.32 (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 277b, 318), due to

the fact that the Fund’s volunteer solicitators had to drop

Texas from the list of states in which services and assistance

were available— the state having restrained its operations

during that time (Pl. Ex. R-9, pp. 278, 279). Another drop

is reflected in the comparative income for the first eight

months of 1957 and that for the same period in 1956: $152,-

000 and $246,000, respectively (Pl. Ex. R-9, p. 278), i. e.,

after the precariousness of Fund operations in Virginia was

widely publicized.

While studies by professional fund raising advisors reveal

that the Fund’s income from Virginia cannot be determined

precisely because many Virginia contributors work in and

mail their contributions from Washington, Fund income from

Virginia to the extent that is shown on the books shows a de

cline from $6,256.19 in 1955 to $1,859.20 in 1956 to $424.00 for

the first two-thirds of 1957 (Pl. Ex. R-9, p. 280).

As to the Fund expenditures for services in Virginia, ex

clusive of the services and personal counsel contributed

12* by the New York Staff in *Virginia litigation (e. g.,

see Pl. Ex. R-9, p. 319), the amounts are $6,344.39 in

1954, $6,000.00 in 1955, $6,490.00 in 1956 and $3,500.00 in

1957 for the first eight months (PI. Ex. R-9, p. 281).

There is no dispute on the record as to the effect of the

assailed statutes upon the operations of the Fund in Vir

ginia, especially in the present atmosphere of fear and un

easiness: contributions have dwindled and will cease (PI.

Ex. R-9, pp. 280, 281) with a resulting cessation of contri

butions from the intransigent South (PI. Ex. R-9, p. 283);

many lawyers, white as well as Negro, would not work for

or with the Fund (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 284, 324, 331, 338); and

, would restrain the Fund from participating in civil rights

litigation and ultimately destroy it (PI. Ex. R-9, p. 285).

The Fund assists in litigation only when specifically re

quested to do so by the litigant or his attorney (PI. Ex. R-9,

pp. 253, 270-271, 272, 319). Requests from Virginia may be

addressed to its New York Office or to its regional counsel in

Virginia (PI. Ex. R-9, p. 270). The Fund makes its own

decision in each case as to whether it will assist (PI. Ex.

R-9, pp. 254, 272-273), and in no event is assistance forth

coming unless the particular case is basically meritorious

and involves an issue of denial of civil rights on the basis of

race or color (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 253-254, 255-256). The as

sistance afforded may consist in advice, data, services and

money, including the entire cost of litigation and attornev’s

fees (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 254, 255-256, 264, 265, 319-320). This

assistance may he afforded to litigants who have retained

lawyers not connected with either the Fund or the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (PL

Ex. R-9, pp. 274-275, 290), and the legal services supplied

by the Fund may he rendered either by a staff attorney, an

annually retained regional attorney, or by an attorney spe

cially engaged for the purpose (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 265-266, 270).

Salaried and annually retained attorneys do not receive extra

compensation in such instances (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 265, 274),

and once the attorney-client relation is established, the Fund

neither reserves nor exercises any control over the litigation,

this being a matter for the litigant and the attorney conform

able to the Canons of Legal Ethics (PL Ex. R-9, pp. 256, 352-

353).

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 11

13* *APPELLANT’S CONSTITUTIONAL CONTEN

TIONS IN THE FEDERAL FORUM: CHAPTERS 33

AND 36 ABRIDGE FREEDOMS OF EXPRESSION

AND ASSOCIATION AND VIOLATE THE DUE PRO

CESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSES OF

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

12 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Chapters 33 and 36, both of which relate to and provide

penal and disciplinary sanctions for improper practice of

law, respectively amend and expand the provisions of the

Virginia Code defining “ unprofessional conduct” and the

offense of “ running and capping” or “ ambulance chasing,”

Sections 54-74, 54-78, 54-79 (PL Ex. No. 9, p. 507), and for

mulate a statutory definition of the common law offense of

maintenance (PI. Ex. 9, p. 506). Appellant, conformably

to the ruling of the District Court (159 F. Supp. 503, 534; PI.

Ex. 7, p. 42) sought from the Circuit Court a construction

or interpretation of these statutes in the light of the con- .

stitutional contentions presented by them to the federal

forum. See Government & C. E. 0. C., CIO v. Windsor, 353

U. S. 364; Spector Motor Service v. O’Connor, 340 IT. S. 602,

which reversed 181 F. (2d) 150 (2nd Cir.) and affirmed

Spector Mot of Service v. McLaughlin, 88 F. Supp. 711 (D.

Conn.). Cf. Spector Motor Service, Inc. v. Walsh, 15 Conn.

Sup. 205, affirmed in part and reversed in part 135 Conn. 37,

61 A. (2d) 89._

Those constitutional contentions were presented to the

Circuit Court by the complaint, in the brief and on oral argu

ment therein. In short, they were and are that enforcement

of Chapters 33 and 36 against appellant, its officers, mem

bers, employees, contributors, voluntary workers, and at

torneys employed or retained by it, or to whom they may

contribute advice or monies, abridges freedoms of expression

and association and violates rights secured under the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

That appellant may assert the constitutional rights of

members, employees, contributors and others closely related

to its activities or, in other words, has standing to litigate

with respect to the effect of contested legislation upon such

persons is, of course, now firmly established in our constitu

tional jurisprudence. National Asso. For The A. C. P. v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449; Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354

14* U. S. 234, 250; *Bafrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249;

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 123, 159, 187; Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 IT. S.

510: Buchanan v. Worley. 245 U. S. 60; Truax v. Raich, 239

IT. S. 33; BCewer v. Hoxie School Dist. No. 46, 238 F. (2d)

91 (8th C ir.); City of Houston v. Jas. K. Dobbs Co., 232 F.

(2d) 428 (5th C ir.); N. A. A. C. P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503,

529 (D. C. Va.), vacated on other grounds sub nom Harrison

v. National Association for the Advancement o f Colored

People, U. S. (decided June 8, 1959).

A. The Offenses Created By Chapters 33 and 36 Are De

fined So Broadly That Activities Related To The Exercise

Of First Amendment Freedoms Are Made Criminal.

Appellant is a non-profit membership corporation engaged

in activities aimed at vindicating and establishing the rights

of Negroes to be free from racial discrimination. It has a

relatively small membership but enjoys wide support of

contributors through the nation, some of whom are in the

State of Virginia. Primarily, the Fund is a medium through

which its members and contributors may pool their re

sources to furnish legal aid to worthy Negroes who may

assert in meritorious litigation rights denied or abridged

because of race (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 254-256, 258-262, 277). It

also does educational work in the form of distributing liter

ature, giving lectures, etc., to help further civil rights (PI.

Ex. R-9, pp. 258, 267-268).

Appellant, therefore, is in essence a medium of expression

for those who express or assert opposition to racial degrega-

tion or discrimination by instituting or prosecuting litiga

tion challenging it in a judicial or administrative forum.

Whether speech is expressed individually or, as has become

more and more necessary in contemporary society, in con

cert, it is protected by the great restraints Avhich were

initially written into the First Amendment and made ap

plicable to the states by the Fourteenth. As Justice Frank

furter wrote in Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183, 195,

“ joining is an exercise of the rights of free speech and

free inquiry.” It is significant that some of the major cases

of recent years involving free speech have involved con

certed activity and that the constitutional protections of

free speech have been unquestionably held applicable

15* to them. *See, e.g., Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S.

178, Siveezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234; United

States v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612; American Communications

v. Doiids, 339 U.S. 382; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516.

Today it is the rare free speech case which involves the

individual street-corner speaker, for as Mr. Justice Jackson

pointed out in Thomas v. Collins, supra, free speech ques

tions today do not arise unencumbered by purportedly valid

regulations of daily business activities, 323 U.S. at 546, 547;

“ It is not often in thise country that we now meet with

direct and candid efforts to stop speaking or publication as

such. Modern inroads on these rights come from associating

the speaking with some other factor which the state may

require so as to bring the whole within official control.”

Such an inroad on the freedoms of expression and associa

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 13

14

tion has been made by Virginia where, under the guise of

protecting the administration of justice, Chapters 33 and

36 expressly prohibit group support of civil rights litigation

by and through appellant as well as effectively proscribe

speech which proffers assistance in such suits. This, we

submit, Virginia cannot do because it abridges rights se

cured under the First Amendment and shielded against state

action by the Fourteenth Amendment. National Asso. For

The A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449. _

Croup sponsorship of litigation is as indigenous to

twentieth century America as is group sponsorship of wel

fare and charities. See Schesinger, Crisis Of The Order

(1957); Schlesinger, “ Biography of a Nation of Joiners,”

50 Am. Hist. Rev. 1 (1944). It generally occurs after a group

or some member of the group has urged the initiation of

a lawsuit or the support of a pending case to secure some

legal right in which the group has a special or general

interest. Counsel is then either chosen by the group, or the

services of a volunteer are accepted, or the litigant’s at

torney is paid by the group. Other costs of the litigation are

generally borne in whole or in part by the group. And in

most cases the group appeals to its members or to the public

for financial support. See Association of the Bar of the

City of New York & New York County Lawyers’

16* * Association, Opinions Of The Committeeb On Pro

fessional Ethics, Ops. No. 113, 170, 210, 320, 321, 343,

585, 707 (1956).

No court in the United States has ever denied the right

of individual or group sponsorship of litigation, such as is

here involved, where there is no agreement to share the

proceeds and where the members of the group have a com

mon or general or patriotic interest in the principle of law

to be established. In cases in which this right has been

challenged the courts have expressly upheld it despite con

tentions that is was barratrous, champertous, or maintenous

activity, or that it constituted malpractice or unethical

solicitation and procurement of legal business. See Brannon

v. Stark, 185 F. 2d 871 (D C. Cir.), a ff’d 342 U.S. 451;

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 12 S.E. 2d 602;

Brush v. Carbondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N.E. 252; Davies v.

Stowell, 78 Wis. 334, 47 N.W. 370; Royal Oak Drain Dist.

v. Keefe, 87 F. 2d 786 (6th C ir.); Vitaphone Corp. v. Hutchi

son Amusement Co., 28 F. Supp. 526 (D. C. Mass.). See also

In Re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. C. M d.); Bigeloiv v. Old

Dominion Copper Mining & Smelting Co., 74 N. J. Eq. 457,

71 A. 153; Mobile & O. R. Co. v. Etheridge, 84 Tenn. (16

Lea) 398; Frost v. Paine, 12 Me. (3 Fiarf.- III. Gowen v.

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Nowell, 1 Me. (1 Greenl.) 292; City of Bridgeport v. Equit

able Title & Mortgage Co., 106 Conn. 542, 138 A. 452; Com

monwealth v. Dupuy, 4 Clark 1, 6 Pa. Law J. 223.

Brannon v. Starli, supra, upheld the right of certain hand

lers of milk to finance the litigation of certain milk pro

ducers. Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., supra, upheld the

right of the Atlanta Bar Association to furnish counsel for

the litigation of those who had been victims of the loan

sharks. Brush v. Carbondale, supra, upheld the right of

citizens to finance an appeal by the city in a test case. Davis

v. Stowell, supra, upheld the right of buyer's of worthless

stock to prosecute a test case brought by plaintiff to deter

mine defendant’s liability, each buyer contributing to the

expense of plaintiff’s case. Royal Oak Drain Dist. v. Keefe,

supra, upheld the right of a bondholders’ protective com

mittee to bring a class suit to determine the validity of

bonds Vitaphone Corp. v. Hutchison, supra, upheld the main

tenance of a copyright protection bureau by a group of

movie producers and distributors to protect their copyrights

by bringing suit where necessary.

17* *In Re Ades, supra, upheld the right of a lawyer,

who had been employed by the International Labor

defense, a group which sponsored litigation, to volunteer

his services to persons accused of crimes. Bigelow v. Old

Dominion Copper Mining & Smelting Co., supra, sustained

the right of stockholders to press for and contribute toward

litigation by a corporation. Gowen v. Nowell, supra, upheld

the right of a group to urge and support a test case in

volving taxes. City of Bridgeport v. Equitable Title &

Mortgage Co., supra, involved the participation of original

owners of property assessed in their names in, and their

support of, a suit to foreclose tax liens. And in Common-

tvealth v. Dupuy, supra, the right of a group of citizens to

urge and contribute towards a criminal prosecution was

upheld.

Not only has the practice of individual and group spon

sorship of litigation been sustained by the courts, but it

has also been approved by bar associations. The Committee

on Professional Ethics of the Association of the Bar of the

City of New York says as to group sponsorship of litigation:

“ A litigant may solicit the cooperation of persons interested

in the same principle of law; and such solicitation may prop

erly be done by his attorney, when it is primarily and funda

mentally in the interests of the client * * * ” Opinions of The

Committees on Professional Ethics, supra, Op. No. 343. See

Ops. No. 113, No. 170, No. 281, No. 321, No. 363, No. 586.

As to individual sponsorship of litigation, the same com

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 15

16

mittee says: “ Under proper circumstances and where real

interests are involved, lawyers may act for one party where

legal fees and other expenses are defrayed by another.”

Id., Op. No. 707.

Indeed, the Canons of Professional Ethics of the Ameri

can Bar Association expressly approve the activities of

charitable organizations in paying the expenses of the liti

gation of others. Canon 35. See Richmond A ss’n. of Credit

Men v. Bar Association, 167 Va. 327, 334; American Bar

Association, Opinions Of The Committee On Professional

Ethics, Op. No. 148 (1957). Cf. In Re Ades, 6 F. Supp. at

475. Moreover, the development of Anglo-American Juris

prudence has always been toward expanding the opportuni

ties of litigants to present their cases as fully and com

pletely as justice may require and to avail themselves

18* whatever assistance they *need in their presentation.

Legal Aid, in the United States, passim, (1951); Smith,

Justice and the Poor, passim, (1921). Conformably there

has been continued liberalization of rules of procedure which

has facilitated the development of group sponsored litiga

tion. See, e.g., Rule 23 (a) (3), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure; Association of the Bar of the City of New York

& New York County Lawyers’ Association, Opinions Of The

Committees On Professional Ethics, Op. No. 113 (1956).

Now when a labor union urges the bringing of suit to test

the validity of anti-labor legislation; when a trade associa

tion urges the bringing of a suit to test the validity of a

law regulating trade; when a consumers group urges the

defense of a suit testing the validity of social welfare legis

lation; when a racial group urges one of its members to

challenge the validity of racially discriminatory legislation;

when a tenant’s association urges the bringing of a suit to

test the validity of a new rent increase— are these groups

engaged in the commission of a crime or are they engaged

in exercising their constitutionally protected rights to free

dom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of association

and freedom of the press? Appellant says it is the latter.

Virginia says it is the former. For Chapters 33 and 36 de

clare that, despite the fact that such groups are not engaged

in stirring up groundless litigation and despite the fact that

their objective is neither monetary profit for themselves nor

the vexation of others, the activities of these groups are

violative of the offenses defined or redefined therein.

Appellant’s view of the law, in sum, is that when groups,

including the Fund, take concerted action in the form of

joint sponsorship of such litigation by agreeing to furnish

legal counsel or to defray expenses, or both, they are not

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

engaged in maintenance or “ running and capping.” They

are exercising their rights to freedom of expression on

public issues and the rights of their supporters to pool their

resources and support action for the benefit of all. Cf.

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234; Watkins v. United

States, 354 U.S. 178, 250-251; Weiman v. Updegraff, 344

U.S. 148; United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41, 46. It is

the manifestation of group sentiment. Cf. United States v.

C. I. 0., 335 U.S. 106, 143-144 (concurring opinion).

19* *And appellant also views the law as saying that,

when financial contributions are solicited from the

public to assist in defraying tbe expenses of such litigation,

these groups are engaged in the exercises of the right to in

fluence others, a right incidental to the exercise of freedom

of speech and assembly. Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S.

105; Follet v. McCormick, 321 U.S. 573.

B. The Offenses Provided For Under Chapters 33 and 36

Are Framed So As To Amount To A Denial Of Due Process

Of Law.

Chapters 33 and 36 relate to the improper practice of law.

The amendment of Sections 54-74, 54-78 and 54-79 of the

Virginia Code contained in Chapter 33 and the offenses

created by Chapter 36 are new in the law of the State. Vir

ginia, of course, may reasonably regulate the practice of

law. But appellant submits that where such regulation pro

hibits activities otherwise approved or endorsed by those

whose experience is closer to such matters—the bench and

the bar—as guardians of the deep seated interests o f society

which are reflected in legislation dealing with punishment

for maintenance and ambulance chasing, it amounts to a

denial of due process of law.

Turning to the offense defined in Chapter 33, “ running

and capping” or “ ambulance chasing” generally forbids

those activities of laymen who follow up accidents and

approach the injured or their personal representatives to

induce them to sue for damages with a view towards solicit

ing business for an attorney in consideration for a share of

the proceeds. In re Mitgang, 385 111. 311, 52 N.E. 2d 807,

816; Doughty v. Grills, 260 S.W. 2d 379, 387 (Tenn.); In re

Newell, 174 App. Div. 94, 160 N. Y. S. 275, 278; State ex

rel. Nebraska Bar A ss’n v. Basye, 138 Neb. 806, 295 N.W.

816, 817. See State ex rel Wright v. Hinckle, 137 Nebr. 735, 291

N.W. 68; Clxreste v. Commonwealth, 171 Ky. 77, 186 S.W. 919.

“ Ambulance chasing” also has included within its ambit an

attorney’s solicitation of employment either personally or

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 17

18 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

through others, especially in personal injury cases where the

consideration is a share in the recovery. 5 Am. Jur. 425-426;

Kelley v. Boyne, 239 Mich. 204, 214 N.W. 316, 318. See State

ex rel. Wright v. Hinckle supra; Re Shay, 133 App. Div. 547,

118 N. Y. S. 146, affirmed 196 N. Y. 530, 89 N.E. 1112. Today

“ ambulance chasing” is considered as embracing any

20* attorney *who obtained employment in any type of liti

gation either personally or through others who share in,

or are compensated out of, the recovery. 5 Am. Jur., supra.

See People v. Gray, 52 Cal. App. 2d 620, 127 P. 2d 72.

However the offense has been defined by statute or judicial

construction or in disciplinary proceedings, whether termed

“ ambulance chasing” or “ running and capping,” the one

common element is that the solicitation is carried on for a

share in the personal or real property recovered.

Maintenance, the offense created by Chapter 36, is also

aimed at trafficking in lawsuits. But, unlike “ ambulance

chasing” , “ no personal profit is expected or stipulated.”

Sampliner v. Motion Picture Patents Co., 255 F. 242 (2nd

Cir.). Precise statutory definitions of maintenance are rare,

See 111. Stats. Anno., Ch. 38, Sec. 66; Colo. Rev. Stat., Sec.

40-7-41 (1953), but at common law it was succinctly defined

as officiously aiding another in his suit. Winfield, “ The His

tory of Maintenance and Champerty,” 35 Law Q. Rev. 50. 56

(1919). More common law definitions are plentiful, e.g., “ of

ficiously interfer| [ing] in a law suit, in which [one] has no

present or prospective interest, to assist one of the parties

against the other, with money or advice, without authority

of law,” McIntyre v. Thompson, 10 F. 531, 532 (C. C. N. C .) ;

the unlawful taking in hand or upholding of quarrels or sides

to the disturbance or hindrance of common right, Gibson v.

Gillespie, 4 W. W. Harr. (Del.) 331, 152 A. 589; “ an officious

intermeddling in a suit that no way belongs to one, by main

taining or assisting either party with money or otherwise to

defend it,” 4 Blackstone 135, quoted in Sampliner v. Motion

Picture Patents Co., supra; and “ maintenance, as I under

stand it, upon the modern construction, is confined to cases

where, a man improperly, for the purpose of stirring up liti

gation and strife, encourages others either to bring actions or

make defenses which they have right to make,” Fonden v.

Parker, 11 Mees. & W. 75, quoted in John v. Champagne Lum

ber Co., 157 F. 407 at 418 (D. C. Wis.) and Davis v. Stowell,

78 Wiss 338, 47 N.W. 371.

According to 10 Am. Jur. 548-549, which summarizes the

early law and modern view, the following conclusions are

stated.

21* * Considering the modern view and the general modi

fication and amelioration of the rules regarding main

tenance, there is considerable doubt whether any of the at

tempts at giving strict definitions of what constitutes main

tenance at the present day are either successful or useful

(Id. at 549).

Then after criticising the vice of formulating a strict defini

tion and providing a string of exceptions, it concludes, at

p. 549:

A definition in consonance with the modern view, and often

judicially stated, is that maintenance means the act of one

improperly, and for the purpose of stirring up litigation and

strife, encouraging others either to bring actions or to make

defenses which they have no right to make, and the term

seems to be confined to the intermeddling in a suit of a

stranger or of one not having any privity or concern in the

subject matter, or standing in no relation of duty to the

suiter.

Agreeably, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sec

ond Circuit in a recent case ruled that there was no main

tenance because it found no “ purpose” on the part of the

alleged maintener “ to foment suits which did not seek to

protect a legitimate business of its own.” Chester H. Roth,

Inc. v. Esquire, Inc., 186 F. 2d 11, 15. And, earlier, in John v.

Champagne Lumber Co., 157 F. 407, 418, the conclusion was

that the giving of financial aid to a poor suitor who is prose

cuting a meritorious cause of action neither violated the law

nor offended public policy: “ The law does not tolerate the

notion that a powerful defendant may force the abandon

ment of a suit whenever he is able to exhaust the slender

means of a weak antagonist.”

So, despite the attempts which have been made throughout

our legal history to pervert the judicial machinery into an

instrument of oppression, the courts have never penalized

those who, in good faith, befriended the suitor. Radin, Main

tenance By Champerty,” 24 Cal. Rev. 48 (1935). And, in line

with this, the development of the law has always been toward

expanding the opportunities of litigants to present their cases

as fully and completely as justice may require and to avail

themselves of whatever assistance they need in their pres

entation. See Schlesinger, Crisis of the Old Order 113, 419,

(1957); Mirrors of Justices, 7 Seld. Soc. 14 (1893); McGuire,

“ Poverty and Civil Litigation,” 36 Harv. L. Rev. 361; Cohen,

“ The Origins of the English Bar,” 81 Law Q. Rev. 56, 72-73;

N.A.A.C.P. v. A. S. Harrison, Jr., Atty. Gen. of Va. 19

20 Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Brownell, Legal Aid In the United States (1951);

22* *Smith, Justice and the Poor (1921); “ Legal Aid Proj

ect Arouses Dispute,” New York Times, Sept. 8, 1957,

p. 118.

However, Virginia, by enacting Chapters 33 and 36, has

ignored historical experience and disregarded the basic ele

ments of the crimes defined therein, including the firmly

established exceptions thereto—and all this under the guise

of protecting the administration of justice. As framed, these

laws forbid a continuance of the activities of appellant and, in

large measure, operate to destroy its effectiveness. This Vir

ginia cannot do, appellant submits; it amounts to a denial

of due process of law.

C. Chapters 33 and 36 Violate The Due Process Clause of

The Fourteenth Amendment Because They Fetter Access To

The Federal Courts.

Any litigation is expensive; that with which appellant has

come to be identified is uncontrovertably too dear for most

named plaintiffs therein to bear, either individually or jointly

without outside assistance in the form of money or services,

or both (PI. Ex. 9, p. 345). Indeed, the expense incurred in an

anti-discrimination case which is tried and then concluded

following review in a United States Court of Appeals ap

proximates $5,000; if it has to be taken up to the Supreme

Court of the United States, the. cost usually mounts to around

$50,000 although in protracted litigation like Siveatt v.

Painter, 339 U.S. 629 and the School Segregation Cases,

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294, the

expenses have ranged from around $100,000 to over $200,000

(PI. Ex. 9, pp. 262-269, 314). In Virginia, the final figure in

some of the suits seeking to secure nonsegregated schooling

may be ever greater because none has been concluded and

most have been litigated and relitigated at each level of the

federal system. See, e.g., Davis v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, Va., 103 F. Supp. 337, reversed 347,

U.S. 483, remanded 349 U.S. 249, decree on remand 1 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 82, motion for further relief referred to one-

judge District Court 142 F. Supp. 616, motion for further