Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

June 12, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1975. 90e24433-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/62bd63c8-412a-4345-947f-0f77b2e44cd5/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

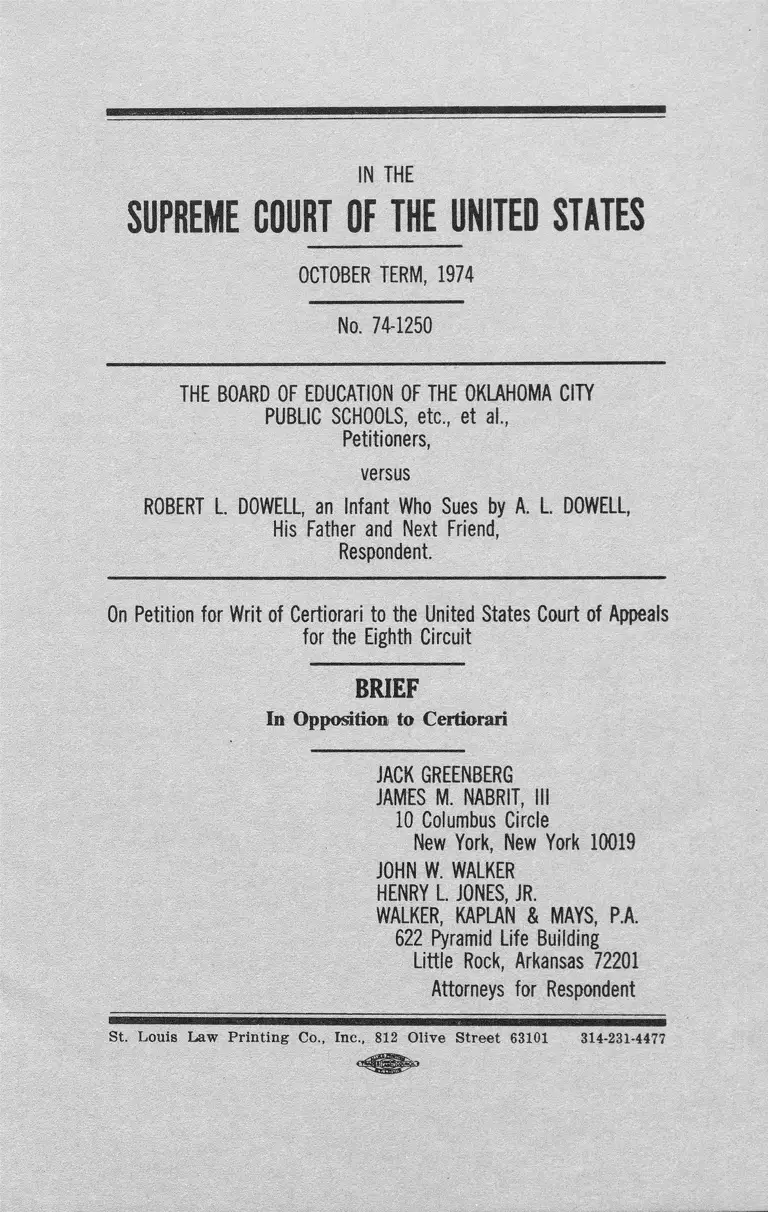

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 74-1250

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, etc., et al„

Petitioners,

versus

ROBERT L. DOWELL, an Infant Who Sues by A. L. DOWELL,

His Father and Next Friend,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF

In Opposition to Certiorari

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

HENRY L. JONES, JR.

WALKER, KAPLAN & MAYS, P.A.

622 Pyramid Life Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Respondent

St. Louis Law Printing Co., Inc., 812 Olive Street 63101 314-231-4477

INDEX

Page

Opinions Below ........... 1

Jurisdiction ................................ 2

Question Presented ............................. 2

Statute Involved ................................................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ............................... 2

Statement of the C a s e ............................................................. 3

A rgum ents................................................................................. 7

District Court’s Discretion ............................................... 7

Due P rocess.......................................................................... 8

Conclusion ................................................................................ 10

Cases Cited

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v.

Dowell, 375 F. 2d 158 (1967 )........................................... 7

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, Inc., 487 F.2d

890 (6th Cir. 1973) ........................................................ 9

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 453 F. 2d

1104 (5th Cir. 1971) ........................................................ 8

Mays v. Board of Public Instruction of Sarasota County,

Florida, 428 F.2d 809 (5th Cir. 1970) ......................... 7

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ..................................................................... 7

Statute and Constitution Cited

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................................................. 2

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment . . . . 2

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 74-1250

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, etc., et a!.,

Petitioners,

versus

ROBERT L. DOWELL, an Infant Who Sues by A. L. DOWELL,

His Father and Next Friend,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF

In Opposition to Certiorari

OPINIONS BELOW

The orders of the District and the Tenth Circuit are not re

ported but are set forth in Appendices A and B of the Pe

tition.

2 —

JURISDICTION

The jurisdictional requisites are set forth in the Petition.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the United States District Court for the Western

District of Oklahoma acted within the bounds of its discretion

in changing the assignments of principals at two schools in the

system which had remained clearly racially identifiable in part

because of the system’s historical assignment pattern.

STATUTE INVOLVED

The Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment as set forth at page

3 of the Petition.

— 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This phase of this lengthy litigation involves the District

Court’s effort to further disestablish the racial identifiability of

two former “black” senior high schools and to thereby insure

compliance with the Court’s prior orders.

The District Court has issued repeated orders requiring, in

effect, the establishment of a unitary, nonracial school system.1

The record is replete with substantive and substantiated findings

that the school district has not proceeded in good faith to de

segregate the schools. Most of those findings were made and

upheld prior to the approval of the present comprehensive de

segregation plan and prior to the effective functioning of the

bi-racial committee.

Since their appointment, the members of the bi-racial com

mittee have made many recommendations for the maintenance

and furtherance of desegregation. Upon receipt of suggestions

and recommendations from the bi-racial committee, the Court

followed the practice of inviting and receiving responses thereto

from the parties and thereafter entering ORDERS either approv

ing, disapproving or modifying the suggestions and recom

mendations. The full record clearly establishes this procedure.

In the instant case, the bi-racial committee recommended in

its April 30, 1974 report, inter alia, that the races of the prin

cipals at four specific senior high schools be changed. The

Committee also recommended certain boundary changes for

desegregation purposes. The Court entered an ORDER on May

2, 1974, stating that it had approved school board proposals for

1 The respective relevant ORDERS were entered on the follow

ing dates: (1) July 11, 1963; (2) September 7, 1965; (3) August 16,

1967; (4) August 8, 1969; (5) August 13, 1969; (6) September 11,

1969; (7) January 17, 1970; (8) February 1, 1972; and (9) February

4, 1972.

— 4

“minimal changes” in attendance zones of Northeast, Douglas

and Grant high schools in order to further “eliminate all vestiges

of state imposed segregation.” The Court went on to find that

despite its prodding, the school system retained numerous ves

tiges of segregation, for which the board was not undertaking

voluntarily to devise and implement appropriate and effective

remedies. The Court said:

“There is no evidence that the individual board members

are even reading the Board’s own reports to the Court or

those of the Bi-racial Committee. Useful and constructive

recommendations by the bi-racial committee have repeat

edly been totally ignored by the board without even token

discussion. . .”

“. . . the Board apparently is repeating the same old pattern

of recalcitrance condemned by the Court in its Order of

February 1, 1973.”

The Court then specifically directed the school board to, on or

before May 10, 1974

“report in writing to the Court what steps have been taken

to comply with the Court’s order of August 16, 1973, and

shall specifically respond to the suggestions made by the Bi-

racial Committee in its report of May 1, 1974.” [Emphasis

added]

The Court went further and required the school board to ad

vise on a regular (daily if necessary) basis with the chairman

of the bi-racial committee so that the latter body would be able

to give “immediate” and intelligent consideration to the recom

mendations.

On May 29, 1974, the school board responded, stating:

“[After] . . . careful and deep consideration . . . to the

suggestion that the races of the principals be changed at

Douglas, Northeast, Marshall and Grant . . . the Board

5

concluded that keeping the current principals in these four

schools is crucial to the maintenance of stability in these

schools, particularly in the fact of student unrest caused by

further student assignment, and that the objectives of the

suggestion could be accomplished by changing the races

of the assistant principals at the schools.” [See THIRD

REPORT UNDER ORDER DATED MAY 1, 1974]

At no time did the school board request or otherwise indicate

to the Court that it wished to be heard either before or after

the Court passed upon the recommendations of the bi-racial

committee.

On May 30, 1974, the bi-racial committee reported, inter

alia, that it felt:

“the desegregation plan would be advanced significantly

if, as a minimum, the principals at Northeast and Doug

las were white. The present black principals should be

equally able to serve any other high schools in the district.”

On June 3, 1974, the Court entered an ORDER which ap

proved the school board’s plan to change the assignments of

vice principals. The Court’s further ORDER related to the

race of the two principals at Northeast and Douglas. Said the

Court:

“These are the two high schools in the system which have

been and are now clearly racially identifiable in the com

munity. So long as the two high schools with the largest

black enrollment are the only high schools in the system

with blacks as the top administration it will be difficult,

if not impossible, to erase the racial characteristics of the

schools’ identity in the community.” [Emphasis added]

The Court found further that the identifiability factor was

buttressed by the pattern of assignments of principals, i.e.,

white principals in the white communities (kindergarten through

6 —

fourth and fifth grade centers): black principals in black com

munities (fifth grade centers). The Court was aware that in:

. . the normal situation the assignment of school prin

cipals is the matter of administration and of no concern

to the Court but in the factual context here presented, the

Board manifests a policy calculated to maintain the pres

ent status of these schools [black] and to discriminate

against black administrators.” [Bracketing added for clar

ification]

The school board filed Notice of Appeal on June 12, 1974.

The school board also filed a Motion in the District Court to

Stay Order pending Appeal. The Motion, which was opposed

by respondent, was denied by the District Court on June 21,

1974.

The school board filed a Stay Motion in the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit on July 1, 1974, which

that Court rejected on July 22, 1974, one judge dissenting.

The school board filed a Motion for Summary Reversal in

the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit on

or about July 25, 1974, which the Court of Appeals rejected

on August 9, 1974, one judge dissenting.

On January 28, 1975, the District Court’s order of June 3,

1974, was affirmed by a three-judge panel of the Court of

Appeals, one judge dissenting.

7

ARGUMENTS

District Court’s Discretion

The District Court acted within the bounds of its discretion

in ordering a change in the assignment of the two principals

at the two high schools with the largest black enrollment in

the system. These two high schools were also the only high

schools in the system with blacks as the top administrators. In

its effort to disestablish the racially identifiable characteristics

of the schools involved, the District Court considered the his

torical development of the school district during this lengthy

litigation and the pattern of assignments of principals in the

system. If the action of the District Court is considered in

the context of this historical development, it fits clearly within

the guidelines of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 19 (1971).

The basis for the District Court’s order was in fact the race

of the principal at each high school involved. But such a con

sideration is necessary. See, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, supra; Board of Education of Oklahoma

City Public Schools v. Dowell, 375 F. 2d 158, 168 (1967)

(Concurring Opinion).

The only argument in opposition to the recommendation of

the bi-racial committee submitted by the petitioners to the Dis

trict Court was that it would affect the stability of the student

population. This argument was appropriately rejected. See,

Mays v. Board of Public Instruction of Sarasota County, Flor

ida, 428 F. 2d 809, 810 (5th Cir. 1970).

DUE PROCESS

Although the respondent contends that a hearing was not

necessary before the District Court issued its order, the School

Board has not been denied the opportunity for such a hearing.

During the course of this litigation, the bi-racial committee

has made many recommendations in its effort to further the

goal of the complete desegregation of the Oklahoma City School

System. The District Court, in every instance, has invited the

responses of the parties to this suit. After considering the pro

posals and the responses, the Court has entered orders directed

to those recommendations. The defendant school board is well

aware of this practice. The school board did not, however, re

quest a hearing initially, and has not subsequently requested of

the District Court that it hold an evidentiary hearing to con

sider the proposal of the bi-racial committee.

The District Court acted within its discretion, given the past

practices accepted by all parties, in assuming that if the school

board wanted a hearing it would advise the Court of its position.

Instead, the school board submitted its response as usual. After

the District Court issued its order, the school board did not re

veal its hidden desire for an evidentiary hearing and request that

the District Court reconsider its decision. It, instead, filed a

motion in that Court to stay its order pending appeal, and filed

notice of appeal on the same date. Again, no mention was made

in this motion of a hearing.

The position taken by the school board is untenable, given the

prolonged history of segregation in the Oklahoma City School

System. As a result of this continuous segregation, the school

board has the burden of justifying its administrative and faculty

assignments. See, Lee v. Macon County Board oj Education,

453 F. 2d 1104 (5th Cir. ‘1971). The District Court’s task in

9

determining the sufficiency of a school system's compliance with

desegregation orders is a continuing one. The District Court’s

June 3, 1974, order is but another necessary step, after more

than 13 years of litigation, in assuring constitutional compliance.

Because the District Court’s order is based in part on historical

considerations peculiar to this school district, a grant of cer

tiorari would require a re-examination of the evidence presented

during that period.

The District Court’s order is consistent with the decision in

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, Inc., 487 F. 2d 890

(6th Cir. 1973).

10

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

HENRY L. JONES, JR.

WALKER, KAPLAN & MAYS, P.A.

622 Pyramid Life Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Respondent

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the 12th day of June, 1975, I

mailed three copies, postage fully paid, to J. Harry Johnson, 603

First National Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 73102, and

three copies to Larry L. French, P. O. Box 1285, Seminole,

Oklahoma, 74868.

JOHN W. WALKER

Attorney for Respondent