Correspondence from Reynolds to Ganucheau (Clerk); Motion of the United States for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae Out of Time; Correspondence from Guste and Vick to Ganucheau; Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 30, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Correspondence from Reynolds to Ganucheau (Clerk); Motion of the United States for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae Out of Time; Correspondence from Guste and Vick to Ganucheau; Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1987. dafba731-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/63080f82-3452-4ec9-9ec4-7f86ac05e703/correspondence-from-reynolds-to-ganucheau-clerk-motion-of-the-united-states-for-leave-to-file-brief-as-amicus-curiae-out-of-time-correspondence-from-guste-and-vick-to-ganucheau-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

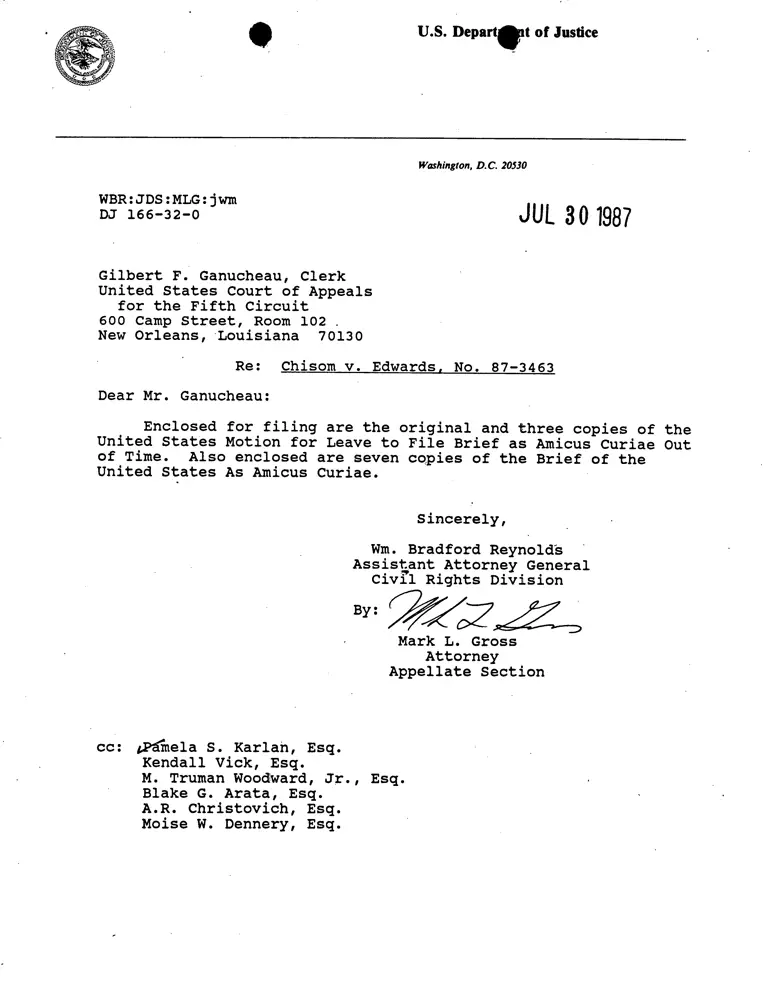

U.S. Depart t of Justice

WBR:JDS:MLG:jwm

DJ 166-32-0

Gilbert F. Ganucheau, Clerk

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

600 Camp Street, Room 102 .

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Washington, D.C. 20530

JUL 30 1987

Re: Chisom V. Edwards, No. 87-3463

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

Enclosed for filing are the original and three copies of the

United States Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae Out

of Time. Also enclosed are seven cqpies of the Brief of the

United States As Amicus Curiae.

Sincerely,

Wm. Bradford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

Civra. Rights Division

By:

Mark L. Gross

Attorney

Appellate Section

cc: pPlinela S. Karlan, Esq.

Kendall Vick, Esq.

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

A.R. Christovich, Esq.

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

MOTION OF THE UNITED STATES FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE OUT OF TIME

The United States hereby moves for leave to .file a brief as

amicus curiae in this case two days late. As grounds for this

motion, the government would show:

1. The issue before this Court in this case -- whether

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to the election of

state court judges -- will affect the government's enforcement

responsibilities. Because this will be the first appellate court

to address this issue, this case is of considerable importance to

the United States. Accordingly, the government has a substantial

interest in participating in this case as amicus curiae.

2. Recognizing this interest, government counsel contacted

appellants' counsel, Pamela Karlan, shortly after the district

court entered its judgment to inform her of possible amicus

participation by the government.

- 2 -

3. Government counsel again re-contacted appellants'

counsel in early July to determine whether the record had been

filed and whether appellants had received a due date from the

Court for filing its opening brief. At that time appellants'

counsel stated that appellants' brief was then due on August 4,

1987.

4. Under the rules of this Court (Loc. R. 31.2), were

appellants' brief due August 4, 1987, a government amicus brief

supporting appellants would be due on or around August 19, 1987.

Accordingly, government counsel constructed his work load to

enable the government to file an amicus brief in this case in

early August.

5. On July 15, 1987, government counsel contacted Ms.

Karlan again, this time to determine whether the district court

had filed an amended opinion and to get a copy of that opinion

from appellants. At that time, government counsel learned for

the first time that appellants had filed their brief on July 13.

6. Under the rules of this Court (Loc. R. 31.2), based on

appellant's filing their brief on July 13, the government's

amicus brief supporting the appellants would be due on July 28.

7. Government counsel moved as quickly as possible to

secure authorization from the Solicitor General for filing an

amicus brief, see 28 C.F.R. 0.20(c), and to prepare the govern-

ment's brief.

8. The United States has filed this motion, with the brief

attached, seeking only two additional days. Accordingly, permit-

- 2 -

3. Government counsel again re-contacted appellants'

counsel in early July to determine whether the record had been

filed and whether appellants had received a due date from the

Court for filing its opening brief. At that time appellants'

counsel stated that appellants' brief was then due on August 4,

1987.

4. Under the rules of this Court (Loc. R. 31.2), were

appellants' brief due August 4, 1987, a government amicus brief

supporting appellants would be due on or around August 19, 1987.

Accordingly, government counsel constructed his work load to

enable the government to file an amicus brief in this case in

early August.

5. On July 15, 1987, government counsel contacted Ms.

Karlan again, this time to determine whether the district court

had filed an amended opinion and to get a copy of that opinion

from appellants. At that time, government counsel learned for

the first time that appellants had filed their brief on July 13.

6. Under the rules of this Court (Loc. R. 31.2), based on

appellant's filing their brief on July 13, the government's

amicus brief supporting the appellants would be due on July 28.

7. Government counsel moved as quickly as possible to

secure authorization from the Solicitor General for filing an

amicus brief, see 28 C.F.R. 0.20(c), and to prepare the govern-

ment's brief.

8. The United States has filed this motion, with the brief

attached, seeking only two additional days. Accordingly, permit-

- 3 -

ting the filing of this brief will not unduly delay appellate

consideration of this case, and will not prejudice any party to

this appeal.

WHEREFORE, the United States requests leave to file its

brief as amicus curiae in this appeal two days late.

Respectfully submitted,

Wm. Bradford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Mark L. Gross

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2172

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I served the foregoing Motion of the

United States for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae Out of

Time on parties to this appeal by mailing one copy to each

counsel listed below:

Pamela S. Karlan, Esq.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Kendall Vick, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue

7th Floor

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

A.R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

This 30th day of July, 1987.

Mark L. Gross

Attorney

Department of Justice

•

A,

SI, •

itrk

" ...... ••

W ILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

,State of Ifiouana

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

July 30, 1987

Honorable Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Clerk, United States Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

600 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

7TH FLOOR

2-3-4 LOYOLA BUILDING

NEW ORLEANS 70112-2096

Re: Chisom v. Edwards,

U.S.D.C. #87-3463

This letter is to confirm my telephone conversation

with Ms. Perkins of your staff wherein I was granted an

extension of time to file a brief on behalf of the appellees in

the above-referenced case. The brief is now due on September

8, 1987.

This extension was requested because the cut-backs in

our legal staff , has added to the already heavy demands on the

time of our remaining staff. I thank you for your assistance.

ETB/md

CC: William Quigley

Ronald Wilson

Roy Rodney

Pamela Karlan

C. Lani Guinier

BY:

Sincerely yours,

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

KENDALL L. VICK

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

EAVELYN

ASSISTA

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

ROGER CLEGG

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER

MARK L. GROSS

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, DC 20530

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES 1

QUESTION PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT 2

A. Procedural history 2

B. Facts 2

C. Decision of the district court 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 4

ARGUMENT:

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT APPLIES

TO JUDICIAL ELECTIONS 5

A. The plain language of the Voting Rights Act

prohibits racial discrimination in judicial

elections 5

B. The 1982 amendments to Section 2 were not

intended to narrow the pre-existing coverage

of Section 2 10

C. One person, one vote principles do not exempt

judicial elections from Section 2 coverage 17

D. The differences in how Section 2 applies to

judicial elections should be left for the

district court to consider on remand 19

CONCLUSION 21

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969) 6, 7

Atlantic Cleaners & Dyers v. United States,

286 U.S. 427 (1932) 8

Ball v James, 451 U.S. 355 (1981) 17

Davis v. Bandemer, 54 U.S.L.W. 4898

(U.S. June 30, 1986) 19

Gaffney V. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) 19

Hadlev_ v. Junior College District, 397 U.S. 50

(1970) 17

Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C.

1985), summarily aff'd, 54 U.S.L.W. 3840

(U.S. June 23, 1986) 4, 7, 8

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss.

1987) 16

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) 5, 9, 11

Pampanga Mills v. Trinidad, 279 U.S. 211 (1929) 8

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) 18, 19

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) 21

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) ▪ ▪ 6, 7

Thornburg v. Gingles, 54 U.S.L.W. 4877

(U.S. June 30, 1986) 11

Trupiano v. Swift & Co., 755 F.2d 442

(5th Cir. 1985) 2

United States v. Sheffield Board of Comm'rs,

435 U.S. 110 (1978) 6, 12, 16

Voter Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge,

612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980) 8, 9, 18,

19, 20

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) 21

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972),

summarily aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) 17, 18

Cases (cont'd): Page

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) 19

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) 12, 13, 19

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish

Sch. Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) 12

Constitution and statutes:

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment 2

Fifteenth Amendment 2

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

42 U.S.C. 1973 et seq.:

Section 2, 42 U.S.C. 1973 passim

Section 5, 42 U.S.C. 1973c 7, 8, 15

Section 14, 42 U.S.C. 19731(c)(1) 9

Pub. L. No. 97-205, Sec. 3, 96 Stat. 134 (1982) 9

Miscellaneous:

111 Cong. Rec.

115 Cong. Rec.

121 Cong. Rec.

128 Cong. Rec.

15722-15723 (1965) 14

38493 (1969) 14

16241 (1975) 15

14132-14133 (1982) 13

H. R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) 14, 15

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) 12, 13, 15

Extension of the Voting Rights Act, Hearings on

H.R. 1407, H.R. 1731, H.R. 2942, H.R. 3112,

H.R. 3198, H.R. 3473, and H.R. 3948 Before the

Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the

House Comm. on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1981) 14, 15

Extension of the Voting Rights Act, Hearings

on H.R. 939, H.R. 2148, H.R. 3247, and H.R. 3501

Before the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Comm. on the Judiciary,

94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) 15

Voting Rights Act, Hearings on S. 53, S. 1761,

S. 1975, S. 1992, and H.R. 3112 Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the Senate Comm. on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) 14

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

V.

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

This case will address the question whether judicial

elections are covered by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 1973. The government has primary

responsibility for enforcement of Section 2, an important federal

statute which prohibits a wide range of racially discriminatory

electoral practices. Since this is the first court of appeals to

address the issue, the United States has considerable interest in

the case's outcome.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to the

election of state court judges.

STATEMENT

A. Procedural history

On September 19, 1986, plaintiffs, black registered voters

in Orleans Parish, Louisiana, filed a complaint alleging that the

system of electing state Supreme Court Justices from the First

Judicial District, which includes Orleans Parish, violated

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments (see R.E. 2).1/ Plaintiffs filed an amended

complaint on September 30, 1986 (R.E. 17-22). Plaintiffs alleged

that the election of two state Supreme Court Justices in the

First Judicial District diluted black voting strength, and sought

an injunction requiring reapportionment of the First District in

a way which does not dilute minority voting strength (R.E. 23).

On May 1, 1987, the district court dismissed the complaint

for failure to state a claim (R.E. 5-16). The court amended its

opinion by order dated July 10, 1987.2/

B. Facts 2/

The seven Justices on Louisiana's Supreme Court are elected

from six judicial districts (R.E. 19). The First District, which

includes Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson

Parishes, elects two Justices at-large (R.E. 20). The other five

1/ "R.E." refers to the Record Excerpts.

2/ "Op." refers to the district court's Amended Opinion, which is

not included in the Record Excerpts.

2/ The allegations of the complaint must be taken as true for

purposes of reviewing the dismissal of a complaint. Trupiano v.

Swift & Co., 755 F.2d 442, 443 (5th Cir. 1985).

- 3 -

districts, composed of several counties each, elect one Justice

(R.E. 19-20).

The population of the First District is 63% white, and its

registered voter population is 68% white (R.E. 20). Plaintiffs

contended that an appropriate division of the First District into

two districts, each of which would elect one Justice, would leave

one district, composed of Orleans Parish, with a 55% black

population and a 52% black registered voting population (R.E. 20-

21).

Plaintiffs alleged that elections in the First Supreme Court

District were dilutive of black voting strength. Plaintiffs

alleged (R.E. 21):

Because of the official history of racial

discrimination in Louisiana's First Supreme

Court District, the wide spread prevalence of

racially polarized voting in the district,

the continuing effects of past discrimination

on the plaintiffs, the small percentage of

minorities elected to public office in the

area, the absence of any blacks elected to

the Louisiana Supreme Court from the Dis-

trict, and the lack of any justifiable reason

to continue the practice of electing two

Justices at-large from the New Orleans area

only, plaintiffs contend that the current

election procedures for selecting Supreme

Court Justices from the New Orleans area

dilutes minority voting strength and there-

fore violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as

amended.

C. Decision of the district court

The district court held that, because Section 2 does not

apply to judicial elections, the complaint had not described a

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The court based

its conclusion on three factors. First, the court stated that

- 4 -

Section 2, by its terms, is violated by circumstances which show

that minorities do not have an equal opportunity "to elect

representatives of their choice" (Op. 6). The court concluded

that judges are not "representatives," and so judicial elections

are not covered by Section 2 (Op. 6). Second, the court noted

that "one man, •one vote" standards do not apply to judicial

elections, demonstrating that judges are not like elected

officials who "represent" voters (Op. 5-6, 8). Third, the court

said the legislative history of Section 2 does not refer to

judicial elections (Op. 7).

The court also dismissed plaintiffs' constitutional claim,

holding that plaintiffs' complaint failed to allege adequately an

intentional violation of minority rights (Op. 12).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court held that judicial elections are not

covered by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. 1973. In so doing, it carved out an exclusion

from the coverage of Section 2 which is unsupported by either the

words or the legislative history of the Act.

Section 2 covers any "voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure." The plain

meaning of this language reaches all elections, including

judicial elections. The same language in Section 5 of the Act

has been held to apply to judicial elections. Haith v. Martin,

618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985), summarily aff'd, 54 U.S.L.W.

3840 (U.S. June 23, 1986).

- 5 -

When Section 2 was amended in 1982, Congress restored the

"results" test which the Supreme Court had effectively eliminated

in its opinion in Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). Under

that test, as explained in subsection (b) of revised Section 2, a

violation of Section 2 may be proved if the results of a

particular electoral practice deny minorities an equal

"opportunity to participate in the electoral process and to elect

representatives of their choice."

The district court here held that Congress, by using the

word "representatives" in subsection (b), intentionally excluded

judicial elections. However, Congress' intent in amending

Section 2 was only to restore the results test which Mobile had

eliminated. Moreover, when it amended Section 2 to add language

codifying the results test, Congress retained the pre-1982

language defining the coverage of Section 2, and there is no

suggestion in any legislative history that Congress intended to

cut back on Section 2 coverage. In addition, Congress' use of

the word "representatives" was not intended as an artful method

of excluding judicial elections, but rather was used to reach any

officials elected by popular vote.

ARGUMENT

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

APPLIES TO JUDICIAL ELECTIONS

A. The plain language of the Voting Rights Act prohibits

racial discrimination in judicial elections

The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 as a means broadly

to combat racial discrimination in voting practices. The Supreme

- 6 -

Court has stated that the Act "reflects Congress' firm intention

to rid the country of racial discrimination in voting." South

Carolina V. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 315 (1966). The Court has

consistently stated that the Act was intended to be a broad

effort to combat racial discrimination in a wide range of voting

and electoral practices. See also Allen v. State Board of

Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 565-566 (1969); United States v.

Sheffield Board of Comm'rs, 435 U.S. 110, 122-123 (1978).

In 1965, when Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, Section

2 read as follows:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny

or abridge the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color.

As discussed at pages 8-9, infra, this language has remained as

the operative part of Section 2. Section 14, 42 U.S.C. 1973

1(c)(1), defines "vote" to "include all action necessary to make

a vote effective in any primary, special, or general election,

including, but not limited to, registration, listing pursuant to

this subchapter, or other action required by law prerequisite to

voting, casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted properly

and included in the appropriate totals of votes cast with respect

to candidates for public or party office" (emphasis added).

This language admits of no exception. Congress, by using

such broad language, intended to reach all voting or electoral

practices which could be used to deny or abridge the right to

vote on the basis of race. That intent has been recognized by

- 7 -

the Supreme Court, which described Section 2 as "broadly pro-

hibit[ing] the use of voting rules to abridge exercise of the

franchise on racial grounds." South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

supra, 383 U.S. at 316. In Allen v. State Board of Elections,

supra, the Court recounted how Congress amended an earlier

version of proposed Section 2 to give it as broad a reach as

possible. "Indicative of an intention to give the Act the

broadest possible scope, Congress expanded the language in the

final version of [Section] 2 to include any 'voting qualifica-

tions or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or

procedure." 393 U.S. 566-567. Accordingly, Section 2, by its

terms, necessarily reaches the election of state court judges;

there is nothing in the language to lend any support to the

notion that Congress did not originally intend for Section 2 to

cover those sorts of elections.

The electoral practices to which Section 2 applies are also

covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973c.

Section 5, which requires certain jurisdictions to submit changes

in their voting practices to federal authorities for preclear-

ance, uses language -- "any voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to

voting" -- identical to that of Section 2 to define covered

practices. It is indisputable that Section 5 covers judicial

elections. In Haith V. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985),

summarily aff'd, 54 U.S.L.W. 3840 (U.S. June 23, 1986), the

district court rejected an argument that judicial elections

- 8 -

should be excluded. The court said, "As can be seen the Act

applies to all voting without any limitation as to who, or what,

is the object of the vote." Id. at 413 (emphasis in original).

That decision was summarily affirmed by the Supreme Court, and,

therefore, is binding precedent.

The language interpreted in Haith to include judicial

elections is the same language Congress used to define the

coverage of Section 2, and basic tenents of statutory construc-

tion require that it be given an identical construction.

Pampanga Mills v. Trinidad, 279 U.S. 211, 217-218 (1929);

Atlantic Cleaners & Dyers v. United States, 286 U.S. 427, 433

(1932).4/ Accordingly, the language of Section 2, and the

Court's summary affirmance in Haith, along with its decision in

Allen and other cases establishing the broad reach of Section 2,

establish that Section 2 prohibits discrimination in all elec-

tions, including judicial elections.

That conclusion is confirmed by this Court's decision in

Voter Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208

(1980). This Court reversed a district court decision dismissing

a complaint which alleged that the at-large scheme of electing

city and state judges in East Baton Rouge Parish diluted minority

voting strength in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

A/ It would create significant anomalies if an intention was

attributed to Congress to permit scrutiny of changes in judicial

election procedures under Section 5, but not to allow suit over

these procedures under Section 2. The result of that would be

that the Attorney General could scrutinize changes in judicial

elections under Section 5, but could not sue to enjoin unchanged

but discriminatory judicial election procedures.

- 9 -

Amendments. This Court rejected the district court's reliance on

the fact that judicial elections are not subject to "one person,

one vote" standards as a basis for holding that judicial elec-

tions may not be challenged as dilutive of minority voting

rights. "To hold that a system designed to dilute the voting

strength of black citizens and prevent the election of blacks as

Judges is immune from attack would be to ignore both the language

and purpose of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments." Id. at

211. Since Section 2, as originally written, was intended to be

coextensive with the Fifteenth Amendment, Mobile v. Bolden, 446

U.S. 55, 60 (1980) (plurality opinion), this Court's Voter

Information Project decision establishes that Section 2 neces-

sarily reached claims involving the election of judges. Con-

gress, of course, must be presumed to have been aware of the

judicial gloss which had been applied to Section 2 when it passed

the 1982 amendments and, as discussed in the next section, there

is no evidence that it intended to overrule the logic of Voter

Information Project.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was amended in 1982 (Pub.

L. No. 97-205, Sec. 3, 96 Stat. 134 (1982)) and now reads as

follows (emphasis added):

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political subdivi-

sion in a manner which results in a denial or abridge-

ment of the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color, or in

contravention of the guarantees set forth in section

1973b(f)(2) of this title, as provided in subsection

(b) of this section.

- 10 -

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based on the totality of circum-

stances, it is shown that the political processes

leading to nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open to partici-

pation by members of a class of citizens protected by

subsection (a) of this section in that its members have

less opportunity than other members of the electorate

to participate in the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice. The extent to which

members of a protected class have been elected to

office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided, That

nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal

to their proportion in the population.

We stress that the original language defining coverage -- "no

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice, or procedure" -- was retained. Paragraph (a) of the

amended statute defines Section 2's coverage and, by retaining

that language, preserves the coverage of the original version.

It is paragraph (b) which contains the "representatives" lang-

uage. As discussed in the next section, however, that paragraph

does not, and was not intended to, define the coverage of Section

2. Rather, paragraph (b) simply sets forth the elements of proof

of a dilution claim. As such, it cannot be read as a general

limitation on the scope of Section 2.

B. The 1982 amendments to Section 2 were not intended to

narrow the pre-existing coverage of Section 2

The district court focused on the word "representatives" in

subsection (b), holding that, because judges are not "representa-

tives," Congress did not intend to cover the election of judges

under revised Section 2. Op. 6-7. As we will show, the district

court's interpretation of the word "representative," and the

- 11 -

importance it gave that word in the statutory scheme, is erron-

eous.

Congress amended Section 2 in response to the Supreme

Court's decision in Mobile v. Bolden, supra. In that decision,

the Court held that the original Section 2 "no more than elabo-

rates upon [the language] of the Fifteenth Amendment," 446 U.S.

at 60 (Stewart, J.); see also id. at 105 n. 2 (Marshall, J.), and

found that Section 2 prohibited only acts of intentional discrim-

ination.

Congress' response was to amend Section 2 to add language

explaining that proof of intent was not required to make out a

violation of the statute. As the Court explained in Thornburg v.

Gingles, 54 U.S.L.W. 4877, 4881 (U.S. June 30, 1986), Congress

disagreed with the Court's Bolden decision and enacted language

-- the "results" test -- which codified Congress' pre-Bolden

understanding that plaintiffs need not prove discriminatory

intent to establish a violation of Section 2 (54 U.S.L.W. 4881 n.

8):

The Senate Report [97-417] states that amended [Sec-

tion] 2 was designed to restore the "results test" --

the legal standard that governed voting discrimination

cases prior to our decision in Mobile v. Bolden, 446

U.S. 55 (1980). S. Rep. 15-16. The Report notes that

in pre-Bolden cases such as [White v.] Regester, 412

U.S. 755 (1973), and Zimmer [v. McKeithen], 485 F. 2d

1297 ([5th Cir.] 1973), plaintiffs could prevail by

showing that, under the totality of the circumstances,

a challenged election law or procedure had the effect

of denying a protected minority an equal chance to

participate in the electoral process.

The phrase Congress chose to place in subsection (b) "to

participate in the political process and to elect representatives

- 12 -

of their choice" -- is derived from the Supreme Court's formula-

tion of the racial dilution test in White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973). In White, the Court, when reviewing a racial

challenge to the election of state representatives, said, "The

plaintiffs' burden is to produce evidence to support findings

that the political processes leading to nomination and election

were not equally open to participation by the group in question

-- that its members had less opportunity than did other residents

in the district to participate in the political processes and to

elect legislators of their choice." Id. at 766.5/ Subsequent

case law, including Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish Sch. Board v. Marshall,

424 U.S. 636 (1976) (per curiam), developed a series of factors

relevant to proof of a Section 2 violation. Congress has stated

clearly (S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 27 (1982)) that

the purpose of subsection (b) was to "embod[y] the test laid down

by the Supreme Court in White [v. Regester]." This intent is

totally inconsistent with the district court's conclusion that

5/ The Supreme Court has rejected occasions to read narrowing

constructions into the Voting Rights Act where those construc-

tions are not compelled by the legislative language or strong

indications in the legislative history. For example in United

States v. Sheffield Board of Comm'rs, supra, the Court held that

jurisdictions which do not register voters are covered by

language referring to "States or political subdivisions." Noting

that the statutory language did not compel the exemption the

Board of Commissioners was seeking, the Court held that the broad

purposes of the Act required the Court to interpret the Act so as

to permit it to reach actions which could result in discrimina-

tion against minorities in electoral procedures. 435 U.S. at

126-128.

- 13 -

Congress intended paragraph (b) to narrow the coverage of Section

2.

The district court has focused solely on the word "represen-

tatives" to support the conclusion that Congress intentionally

excluded judicial elections from Section 2 when it amended the

Act. See Op. 6. There is nothing to support the argument, and

the court cited nothing to show, that Congress chose that word in

order to give the Act a narrower construction. Both the Senate

Report (see S. Rep. No. 417, supra, at 16, 28, 30, 32, 67; see

also comments of Sen. Hatch, at 100) and members in the floor

debate (see, e.g., 128 Cong. Rec. 14132 (comments of Sen. Dole),

14133 (Sen. Thurmond) (1982)) use the term "representatives"

interchangeably with "candidates" when discussing revised Section

2, indicating that the term "representatives" was not considered

a narrowing term of art. The mere use of the word "representa-

tives" cannot carry the force the district court would give it../

The district court stated that because most of the congres-

sional discussion centers on legislative elections and not

judicial elections, the court may presume Congress did not intend

to cover judicial elections when it amended Section 2 (Op. 6-7).

6/ The district court stated that the meaning of the term

"representatives" is clear and unambiguous, so that reference to

the legislative history of the 1982 revisions to Section 2 is

unnecessary. Op. 6. In our view, the use of the term "represen-

tatives" hardly "clearly and unambiguously" excludes the popular

election of judges. Had Congress truly intended specifically to

exclude judicial elections from Section 2 coverage, it would have

been easy to do so with clear language. Indeed, Congress'

decision to replace the word "legislators" in White with the word

"representatives" evidences a desire to cover more than legislators.

- 14 -

However, the legislative history of the 1982 revisions and of

earlier congressional considerations of the Voting Rights Act

demonstrate that Congress was repeatedly made aware that in some

states judges were elected by popular vote.

The legislative history of the 1982 amendments, particularly

the hearings on the various bills to extend or amend the Act, has

many references to the fact that judges are elected in some

states. See, e.g., Extension of the Voting Rights Act, Hearings

on H.R. 1407, H.R. 1731, H.R. 2942, and H.R. 3112, H.R. 3198,

H.R. 3473, and H.R. 3948 Before the Subcomm. on Civil and Consti-

tutional Rights of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong., 1st Sess. 38, 193, 239, 280, 503, 574, 804, 937, 1182,

1188, 1515, 1528, 1535, 1745, 1839, 2647 (1981). The Senate

hearings received much of the same sort of material. See Voting

Rights Act, Hearings on S. 53, S. 1761, S. 1975, S. 1992, and

H.R. 3112 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the Senate

Comm. on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 208-209, 669, 748,

788, 789 (1982).2/

2/ Congress had been given similar information prior to passage

of the Act in 1965 and its extensions in 1970 and 1975. For

example, in 1965, when the Voting Rights Act was first enacted,

there were remarks made on the floor of the Congress which

indicated that judges in some states were elected. See, e.g.,

111 Cong. Rec. 15722-15723 (1965) (comments of Rep. Callaway) (in

Georgia in 1964, "[t]here were uncontested state elections for 37

superior court judges, * * * 3 supreme court justices, and 2

appellate justices"). When extensions of the Act were con-

sidered, Congress was repeatedly made aware of advances blacks

have made under the Voting Rights Act, and the charts which

documented those advances have always included judges in the list

of black elected officials. See, e.g., 115 Cong. Rec. 38493

(1969). When the extension of the Act was considered in 1975,

House Judiciary Committee Report No. 94-196 referred to documen-

- 15 -

In separate comments in the Senate Report, Senator Hatch

stated that the term "'political subdivision' encompasses all

governmental units, including * * * judicial districts * * *."

S. Rep. No. 417, supra, at 151. The district court discounted

this reference, stating that Senator Hatch meant "to be argu-

mentative and persuasive" and did not "mean[] to define [the]

actual scope of the Act." Op. 7 n. 5. To the contrary, there is

no reason to think that Senator Hatch meant anything more than to

indicate his understanding of the coverage of the Act, and to try

to convince other Senators that revised Section 2 would have a

broad effect of the Act on the types of elections, including

judicial elections, he had described. There was no indication

from proponents of the Act that they disagreed with his descrip-

tion of its breadth.8/ Thus, Congress knew that judicial

tation describing the advances blacks had made in elected

positions since the Act was originally passed in 1965. See H.R.

Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 7 (1975). The documentation

on which the Report relied listed "Judges, Justices, Magistrates"

as one entry on the list of elected officials. See also 121

Cong. Rec. 16241 (1975). In addition, the Assistant Attorney

General for the Civil Rights Division, which preclears voting

changes under Section 5, testified at hearings each time Congress

was considering extending the Voting Rights Act. On each

occasion, the Assistant Attorney General submitted documentation

regarding Section 5 submissions, which included references to

matters involving judicial elections. See, e.g., Extension of

Voting Rights Act, Hearings on H.R. 939, H.R. 2148, H.R. 3247,

and H.R. 3501 Before the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

183 (1975); 1982 Hearings on H.R. 1407, H.R. 1731, H.R. 2942,

H.R. 3112, H.R. 3198, H.R. 3473, and H.R. 3948, supra, at 2247,

2260.

g/ In Sheffield Board of Comm'rs, supra, the Supreme Court

relied in part upon a statement made by an opponent of the

language ultimately enacted, and the lack of disagreement by

other members with his description of the Act, as an accurate

- 16 -

elections were among those which the Act would cover. Given such

knowledge, Congress must be presumed to have intended to include

judicial elections absent a clear indication that it intended to

exclude them. There are no such indications anywhere in the

legislative history.

The district court also held that the term "representatives"

excludes judges because judges do not "represent" people, but

interpret the law. See Op. 6. While it is certainly true that

judges do not represent voters in the same way that legislators

do, the term does not exclude judges. As the district court

found in Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183, 1200 (S.D. Miss.

1987), the term "representatives" may readily apply to judges

elected by popular vote:

The use of the word "representatives" in

Section 2 is not restricted to legislative

representatives but denotes anyone selected

or chosen by popular election from among a

field of candidates to fill an office,

including judges. Mississippi has chosen to

hold elections to fill its state court

judicial offices; therefore, it must abide by

the Voting Rights Act in conducting its

judicial elections, including Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act.

While judges do not have constituents whose views they must

consider in carrying out their judicial responsibilities, when

judges are popularly elected it is anticipated that voters will

select those who best represent their own judicial philosophy.

Presumably, that is the reason for allowing the voters to make

indication of congressional intent. See 435 U.S. at 130.

Similarly, here there is no reason to discount Senator Hatch's

statement that Section 2 would reach judicial elections.

- 17 -

the choice. In that limited sense, judges are indeed representa-

tives.2/

C. One person, one vote principles do not exempt judicial

elections from Section 2 coverage

The district court also relied on Wells v. Edwards, 347

F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972), aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973), as

support for its holding that judicial elections are not covered

by Section 2. In Wells, the plaintiff sought reapportionment,

under one person, one vote principles, of the Louisiana Supreme

Court Judicial Districts. The district court denied relief,

holding that one person, one vote principles do not apply to

judicial elections. 347 F. Supp. at 454. The court here stated

that Wells "addressed a voting rights claim arising out of the

same claims of discrimination as in this case" (Op. 4), and

relied on the finding of Wells that judges are not "represen-

tatives" to support its conclusion that judicial elections are

not subject to Section 2. Op. 8. The district court both

misstates the holding in Wells and misapplies the actual holding

to the allegations made here.10/

First, contrary to the district court's holding, plaintiffs

here are not making the same claims as were made in Wells.

2/ A crabbed reading of the term "representatives" would also

exclude elected officials of the Executive branch, which is

clearly incorrect. See Op. 5 n. 3 (citing decision that prosecu-

tors are not "representatives" either).

10/ Here again, moreover, the district court's argument proves

too much since it would exclude those officials who are not

subject to the one person, one vote rule. See Op. 5 n. 3; Ball

v. James, 451 U.S. 355 (1981); Hadley v. Junior College District,

397 U.S. 50, 56 (1970).

- 18 -

Plaintiffs in Wells did not claim racial discrimination, but only

that the judicial districts in question were malapportioned.

Plaintiffs here are not seeking reapportionment of all districts

under one person, one vote principles, but rather are seeking a

remedy for racial dilution allegedly caused by the at-large

election of two justices in the First District. The population

deviations between districts have nothing to do with plaintiffs'

claim here, and a remedy would not, for instance, require reap-

portionment of other districts.

Second, this Court has already found that Wells, and the one

person, one vote principles expressed in the case, are inappli-

cable to claims of racial dilution. Voter Information Project v.

City of Baton Rouge, supra. As explained in Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533, 563 (1964), the doctrine of one person, one vote

addressed claims that electoral systems which weighted votes

differently based on the place of the voter's residence were

unconstitutional. In Voter Information Project, supra, this

Court rejected the applicability of one person, one vote princi-

ples, and the Wells case itself, to questions of racial discrim-

ination.11/ "[T]he various 'one man, one vote' cases involving

11/ The defendants in Haith v. Martin, supra, had argued that

Congress had not intended to subject the election of judges to

Section 5 scrutiny because judicial elections are not subject to

one person, one vote analysis, and because judges do not exert

the same governmental authority as persons in the legislative

branch. 618 F. Supp. at 412-413. The district court properly

concluded that neither distinction was relevant for purposes of

determining whether Congress had, by the language of Section 5,

subjected judicial elections to scrutiny under the Voting Rights

Act. Ibid.

- 19 -

Judges make clear that they do not involve claims of race

discrimination as such." 612 F.2d at 211 (emphasis in original).

Decisions involving nonracial constitutional claims of malappor-

tionment simply cannot determine the scope of a statute passed by

Congress to combat racial discrimination in voting.12/

D. The differences in how Section 2 applies to judicial

elections should be left for the district court to

consider on remand

None of this is to say, however, that judicial elections are

covered by Section 2 in precisely the same way as other elections

are. The differing function of judges from other elected

officials makes different the range of factors to be considered

in determining if a Section 2 violation has occurred. For

instance, "responsiveness" to minority voters is a legitimate

factor to consider for legislators, but would not appear to be

12/ The Supreme Court consistently has distinguished between the

equal protection principles that apply to apportionments under

the one person, one vote doctrine and electoral systems that

discriminate on the basis of race. In White v. Regester, supra,

the Court reversed the district court's determination that a 1970

reapportionment plan for the Texas House of Representatives

violated the one person, one vote principle of Reynolds v. Sims,

supra, but it sustained the lower court's finding that multimem-

ber districts in Dallas and Bexar Counties unlawfully diluted the

voting strength of blacks and Hispanics. See also Whitcomb v.

Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 142-143 (1971); Davis v. Bandemer, 54

U.S.L.W. 4898, 4901 (U.S. June 30, 1986); and Gaffney v.

Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 751 (1973) ("A districting plan may

create multimember districts perfectly acceptable under equal

population standards, but invidiously discriminatory because they

are employed 'to minimize or cancel out the voting strength of

racial or political elements of the voting population" (cita-

tions omitted)).

- 20 -

for judges. Determining the appropriateness of single member

district relief will, we think, differ for judges as wel1.12/

This issue was not, of course, addressed below, and indeed

it may not arise even on remand. The precise range of the

difference in treatment between judges and other officials raises

difficult problems, and we think they are best addressed in a

concrete factual setting. Accordingly, this Court should caution

the lower court that, while judges are covered by Section 2, they

do perform a unique function, and the lower court should flesh

out any relevant facts on this issue on remand. See Voter

Information Project, supra, 612 F.2d at 212 n. 5 (leaving

question of appropriateness of plaintiffs' proposed single-member

)2/ The one person, one vote cases are relevant to the limited

extent that they recognize that judges have this differing

function.

- 21 -

district scheme for remand) .j4/ The United States plans to seek

leave to participate in the remand as amicus.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, this Court should vacate the

district court's judgment and order the district court to

reinstate the complaint.

Respectfully submitted,

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assistant Attorney General

ROGER CLEGG

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER

MARK L. GROSS

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2172

1A/ The district court also dismissed plaintiffs' claim that the

electoral system in the First District violated the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments. The court held that although plain-

tiffs properly alleged that defendants' action had the "purpose

and effect" of diluting black voting strength, the court was of

the "considered opinion, based on the complaint as a whole, that

plaintiffs intend to prove this claim based on a theory of

'discriminatory effect' and not on a theory of 'discriminatory

intent." Op. 12.

The court was certainly correct in stating that it will be

necessary for plaintiffs to prove discriminatory intent to prove

a violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. See,

e.g., Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 239-241 (1976).

However, plaintiffs alleged in their complaint that defendants

acted with discriminatory purpose and alleged facts sufficient to

prove a claim of purposeful dilution. The Supreme Court has

found, moreover, that the dilution factors are highly relevant in

proving a claim of invidious motivation. Rogers v. Lodcle, 458

U.S. 613, 616-622 (1982). The complaint should not have been

dismissed on the court's assumption that plaintiffs would not be

trying to prove their case, as set forth in their pleadings.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I served the foregoing Brief for the

United States as Amicus Curiae on parties to this appeal by

mailing two copies to each counsel listed below:

Pamela S. Karlan, Esq.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Kendall Vick, Esq

Assistant Attorney General

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue

7th Floor

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

A.R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New,Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Mark L. Gross

Attorney

Department of Justice

This 30th day of July, 1987.