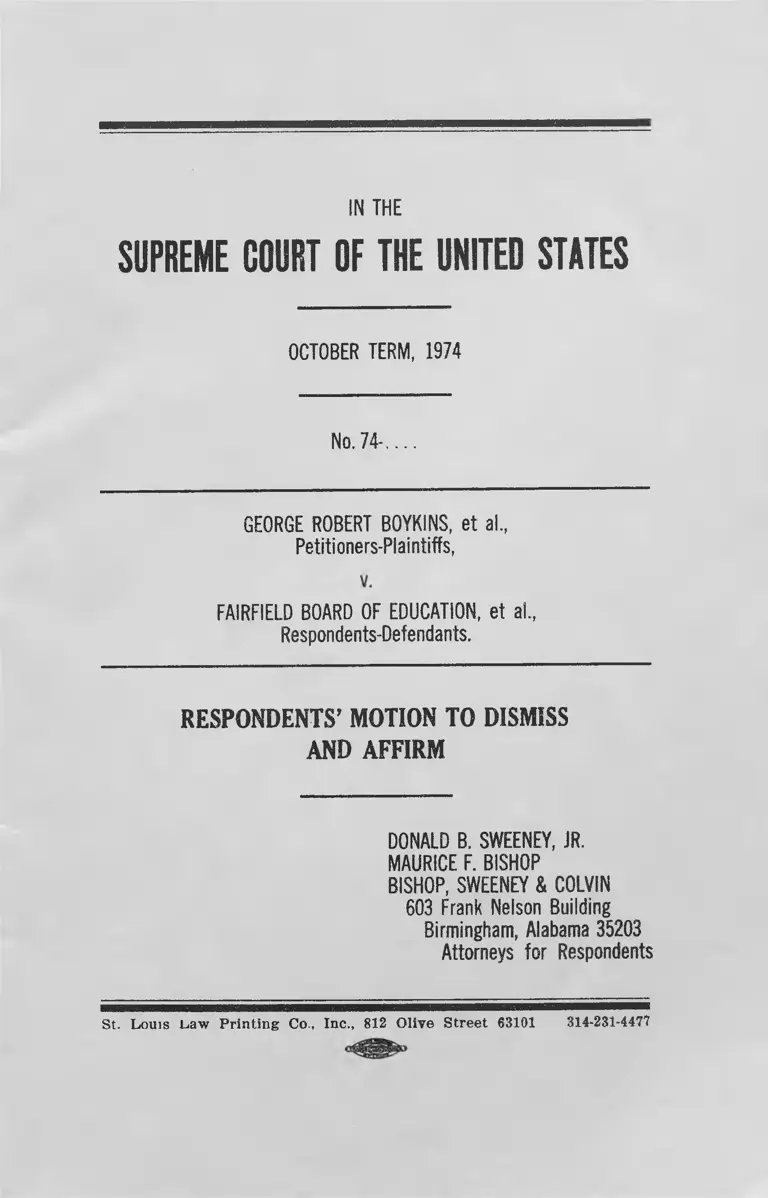

Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Education Respondents' Motion to Dismiss and Affirm

Public Court Documents

May 21, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Education Respondents' Motion to Dismiss and Affirm, 1973. 5c9ea096-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/631ccb62-e771-46fd-b155-3472061397b1/boykins-v-fairfield-board-of-education-respondents-motion-to-dismiss-and-affirm. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 7 4 - . . . .

GEORGE ROBERT BOYKINS, et a!.,

Petitioners-Plaintiffs,

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al„

Respondents-Defendants.

RESPONDENTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS AND AFFIRM

DONALD B. SW EENEY, JR.

MAURICE F. BISHOP

BISHOP, SW EENEY & COLVIN

603 Frank Nelson Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Respondents

St. Louis Law Printing Co., Inc., 812 Olive Street 63101 314-231-4477

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of Issues Presented for Review .......................... 2

Statement of the C a s e .......................................................... 2

Argument............................................................................... 5

I. Where substantial evidence supported disciplinary ac

tion taken by a duly constituted bi-racial school

board, neither the District Court nor the Court of

Appeals were “clearly erroneous’’ in accepting the

board’s findings of f a c t ............................................. 5

II. Where students charged with academic misconduct

are given (1) fair notice of a disciplinary hearing,

(2) specific statement of the charges against them,

(3) a full hearing with the right to examine and pre

sent evidence with the assistance of counsel, the re

quirements of due process are satisfied................... 6

Conclusion............................................................................. 11

Certificate of Service............................................................ 11

Table of Cases

Davis v. Ann Arbor Public School, 313 F. Supp. 1217

(E.D. Michigan, 1970) ..................... ............................. 8, 9

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F. 2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961)....................................................... 6, 7, 8

Duke v. North Texas State University, 469 F. 2d 829 (5th

Cir. 1973) ................................................... ..................... 5, 8

Esteban v. Central Missouri State College, 277 F. Supp.

649 (W.D. Mo. 1967) 8

ii

Ferguson v. Thomas, 430 F. 2d 852 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . 5

Givens v. Poe, 346 F. Supp. 202 (W.D.N.C. 1972)......... 8, 9

Linwood v. Board of Education, City of Peoria, School

District No. 150, Illinois, 463 F. 2d 763 (7th Cir. 1972) 5, 6

Pervis v. LaMarque Independent School System, 466 F.

2d 1054 (5th Cir. 1972 )................................................... 8

Russo v. Central School District No. 1, Town of Rush,

N.Y., 469 F. 2d 623 (2nd Cir. 1972) .......................... 5

Scoggin v. Lincoln University, 291 F. Supp. 161 (W.D. Mo.

1968)................................................................................. 9

Sill v. Pennsylvania State University, 462 F. 2d 463 (3rd

Cir. 1972) ........................................................................ 5

Williams v. Dade County School Board, 441 F. 2d 299

(5th Cir. 1971) ............................... 8

Texts Cited

“General Order on Judicial Standards of Procedure in Sub

stance in Review of Student Discipline,” 45 F.R.D. 133

(1968) ................................ 8

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. 7 4 - . . . .

GEORGE ROBERT BOYKINS, et al„

Petitioners-Plaintiffs,

v.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al„

Respondents-Defendants.

RESPONDENTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS

AND AFFIRM

Appellees in the above entitled case move to dismiss and

affirm Case No. 74—on the ground that the appeal raises only

questions of fact that were correctly resolved by the courts

below.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED

FOR REVIEW

I

Whether the findings of the courts below that substantial

evidence supported the disciplinary action taken by the Fairfield

Board of Education was clearly erroneous?

2

II

Whether the procedures followed in the disciplinary hearing

of November 25, 1972, complied with the requirements of the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

“The essential thrust of Petitioners’ brief is to raise factual

questions through the guise of procedural technicalities. In

raising each issue presented on appeal, Petitioners argue that

even though the District Court made no clearly erroneous find

ings of fact, or improperly applied any governing law applicable

to the field of education, still there must be reversible error. The

arguments presented are frivolous and irrelevant to the subject

matter at hand. A review of the procedures followed by the

Fairfield Board of Education as outlined in the Opinion of the

Courts below (see Appendix A of Petitioners’ brief) shows that

the Fairfield Board conscientiously endeavored to follow pro

cedural guidelines established by the Federal Courts, and did

thereby comply in full with every requirement of the Due Proc

ess Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Respondent Fairfield Board of Education (Fairfield) will

not take detailed exception with Petitioners’ Statement of the

Case or Statement of the Facts, since most of the matters dis

cussed therein are not relevant to the specific findings or the

specific issues now before the Court. Instead, Respondent re

spectfully urges this Court’s attention to the detailed recitation

of the evidence of record in Judge Groom’s opinion of Novem

ber 27, 1972 and December 14, 1972. After treating the issues

relating to curriculum and administrative responsibilities raised

by Petitioners, Judge Groom concluded at page 14 as follows:

“The Court has had many hearings in the Fairfield school

case. When the hearings began there was a white ma-

— 3 —

jority in the school system. There is now a black ma

jority and this majority is growing with every term and

with ever Court order. The number of students in the sys

tem is dropping every year with the consequent loss of

revenue. The cooperation between the races apparently

has disappeared. Picayunish claims are being made on the

one hand and vigorously contested on the other. If this

system is to survive this continued litigation must come to

an end. Many of the black students appear to have over

looked the point that the object of attending Fairfield High

is to obtain an education and not merely to maintain a

point of which an issue may be made. Throughout the

hearing, the lack of discipline on the part of black students

has been evident. This litigation has been enough to ‘tax

the patience of a Job’. This Court has tried to demonstrate

its patience, which has not yet been exhausted but it frankly

is somewhat frayed.” (Emphasis supplied.)

Similarly, after reviewing the record of the disciplinary hearing

which led to the suspension and expulsion of several students,

Judge Grooms, in his opinion of December 14, 1972, reached

the following conclusion at page 4:

“In view of what had occurred at the school prior to No

vember 10, 1972, it was essential that students go to their

classes and remain in their classes rather than milling

around in the halls and continuing the demonstration. It

is not logical nor does it make sense that the teachers would

excuse the students from the classes as several of them

have testified. The demonstrations attending the boycott

could hardly be prevented if the students were excused

from their classes or if they walked out deliberately as the

evidence indicates these students did.

This Court’s order of November 9, 1972, giving these stu

dents the right to return to their classes was conditioned

upon their abandonment of the boycott. Not only did the

— 4 —

action which the evidence shows that they took contravene

the instructions of the school authorities, but it flew in the

face of this Court’s order of November 9, 1972. In view

of those demonstrations the school authorities felt it neces

sary to excuse school on November 10 and this was done

and another day was lost. The maintenance of discipline

was a matter of first concern if classes were to continue.

The students who were disciplined by this expulsion or

suspension flaunted the fundamental principles of disci

pline which obviously were inherent in the situation exist

ing on the morning of November 10, 1972, namely, that

they should go to and remain in their classes and not be

come involved in further demonstrations.” . . .

. . . The hearing that was held by the Board was an ex

tensive one and there was much evidence. The Court does

not feel that it was called on to analyze all of the evidence.

It simply states that within the ambit of its prerogative

respecting the review that the students now complaining

were afforded procedural due process and the expulsion

and suspension were merited under the evidence.”

5

ARGUMENT

I

Where Substantial Evidence Supported Disciplinary Action

Taken by a Duly Constituted Bi-Racial School Board, the Dis

trict Court Was Not “Clearly Erroneous” in Accepting Their

Findings of Fact.

In Ferguson v. Thomas, 430 F. 2d 852 (5th Cir. 1970), this

Court at page 859 held that fact findings by academic agencies

“when reached by correct procedures and supported by sub

stantial evidence, are entitled to great weight, and the Court

should never lightly substitute its judgment for that of the

Board.” See also Duke v. North Texas State University, 469

F. 2d 829, 838 (5th Cir. 1973); Russo v. Central School Dis

trict No. 1, Town of Rush, N. Y 469 F. 2d 623, 628 (2nd

Cir. 1972); Linwood v. Board of Education, City of Peoria,

School District No. 150, Illinois, 463 F. 2d 763, 770 (7th Cir.

1972); Sill v. Pennsylvania State University, 462 F. 2d 463,

469 (3rd Cir. 1972).

In his opinion of December 14, 1972, Judge Grooms re

viewed the evidence concerning (1) Vanessa Arrington, (2)

Beverly Claiborne, (3) Linda Meadows, (4) Clarence Young,

(5) Jacques Guest, (6) Darlene Phelps, (7) Kathy Scott, (8)

John Hall and (9) Beverly Law; and based on that review of

the record concluded at page 4 that substantial evidence sup

ported the administrative action taken.

Petitioners dispute the conclusion reached by Judge Grooms,

not on the grounds that his decision was “clearly erroneous”

under the standards of Rule 52 F.R. Civ. P., but for the reasons

that alternative remedies were apparently not considered by

the Board in reaching their decision as to what punishment was

proper.

— 6 —

Petitioners, in discussing the evidence of each student, con

cede that specific charges of misconduct were made and sub

stantiated by the investigative report of Mr. Hershall Turner,

principal of the Fairfield High School. It is respectfully sub

mitted that an argument on appeal which merely suggests al

ternative remedies while not disputing the substantial evidence

of the record does not sustain the burden of proof necessary to

show reversible error. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Edu

cation, 294 F. 2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961). The facts presented to

support the charges against each student were meticulously de

veloped, carefully documented and openly presented by the

principal of the high school. In each case, full disclosure was

made to the student, and each of the 21 students was given

full opportunity to dispute or deny the factual allegations made.

Based on the testimony given, the Board carefully measured

the punishment appropriate under the circumstances in each

case. In this there was no error. Linwood v. Board of Education,

City of Peoria, School District No. 150, Illinois, 463 F. 2d 763,

770 (7th Cir. 1972).

II

Where Students Charged With Academic Misconduct Are

Given (1) Fair Notice of a Disciplinary Hearing, (2) Specific

Statement of the Charges Against Them, (3) a Full Hearing

With the Right to Examine and Present Evidence With the As

sistance of Counsel, the Requirements of Due Process Are

Satisfied.

The procedure followed in the disciplinary hearing of this

case was discussed by counsel on both sides, explained to all

students collectively, and to each student individually as (s)he

was called before the Board members. The procedure followed

was set forth at the beginning of the hearing:

— 7 —

“(Off-Record Discussion)

“Mr. Sweeney: I wanted to read a short statement from

the leading school disciplinary case which I have always

found instructive and its edict of the Court system followed

since 1960, Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education.

‘School officials and officials should be careful in receiving

evidence against the students. They should weigh it, de

termine whether it comes from a source tainted with preju

dice, determine the likelihood by all surrounding circum

stances as to who is right, and then act upon it as jurors

with calmness, consideration, and fair minds. When they

have done this and reached a conclusion, they have done

all that the laws require of them to do. We think that

students should be informed as to the nature of the charges,

as well as the names of at least the principal witnesses

against him when requested, and given a fair opportunity

to make his defense. He cannot claim the privilege of cross-

examination as a matter of right. The testimony against

him may be oral or written, not necessarily under oath,

but he should be advised as to the nature as well as to the

persons who have accused him.'

“Let me ask you if this procedure will be agreeable. We

will call each student from outside into the conference

room with his parent or guardian. We will explain to the

child what he has been charged with, and ask him if it is

clear in his mind what school rules he has violated. If he

has no questions, we will then present the evidence against

the child to support the accusations. Having done that,

we will ask the student if he has anything to say to con

tradict the charges that have been made against him, or the

evidence to support charges that have been made against

him. After that we will—I think the Board should ask the

School Administrator that is presenting the evidence any—

and the child—any questions that you think are relevant

in order to resolve any conflict. We’re going to accord Mr.

— 8

Newton the privilege of cross-examination. It is not a right

that he can insist on, but we are showing him that courtesy.

After the Board, after the school and the child have pre

sented whatever evidence they want, then we will excuse

the child and go on to the next student. Is that an agree

able process?” (Tr. 6-8)

In adopting the procedure followed, the Fairfield Board of

Education conformed to the standards established by this Court

in Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F. 2d 150

(5th Cir. 1961) and subsequently followed by courts through

out the Federal system. See Pervis v. LaMarque Independent

School System, 466 F. 2d 1054, 1058 (5th Cir. 1972); Duke

v. North Texas State University, 469 F. 2d 829 (5th Cir. 1973);

Williams v. Dade County School Board, 441 F. 2d 299 (5th

Cir. 1971); Givens v. Poe, 346 F. Supp. 202, 209 (W.D.N.C.

1972); Davis v. Ann Arbor Public School, 313 F. Supp. 1217

(E.D. Michigan, 1970); Esteban v. Central Missouri State Col

lege, 277 F. Supp. 649 (W.D. Mo. 1967), affirmed 415 F. 2d

1077, Blackmun, J. (8th Cir. 1969); “General Order On Ju

dicial Standards of Procedure In Substance In Review Of

Student Discipline,” 45 F.R.D. 133 (1968).

While the Supreme Court has written no inflexible blueprint

for all school disciplinary hearings, the essential procedural safe

guards have been stated to include the following, “Three mini

mal requirements apply in cases of severe discipline, growing

out of fundamental conceptions of fairness implicit in the pro

cedural due process. First, the student should be given adequate

notice in writing of the specific ground or grounds and the na

ture of the evidence on which the disciplinary proceedings are

based. Second, the student should be given an opportunity for

a hearing in which the disciplinary authority provides a fair

opportunity for hearing of the student’s position, explanation

and evidence. The third requirement is that no disciplinary

action be taken on grounds which are not supported by any

substantial evidence.”

9

45 F.R.D. 133, 135 (1968). See also Givens v. Poe, 346 F.

Supp. 202, 209 (W.D.N.C. 1972); Davis v. Ann Arbor Public

School System, 313 F. Supp. 1217-1225 (E.D. Mich. 1970);

Scoggin v. Lincoln University, 291 F. Supp. 161, 171 (W.D.

Mo. 1968).

Petitioners do not question the general features of the pro

cedure followed by the Fairfield Board, for the reason that the

Board made every effort to conform to the requirements estab

lished by this Court. Petitioners question only that aspect of the

hearing which related to the presentation of the evidence.

The principal of the Fairfield Fligh School, Mr. Hershell

Turner, investigated each charge brought and then presented to

the Board the result of his investigation. In several instances,

the report involved incidents witnessed by Mr. Turner, himself,

and in others, the reports referred to attendance records and

reports given to Mr. Turner by the teachers involved. Petitioners

contend that none of this information was admissible under

strict rules of evidence. This position is urged notwithstanding

Mr. Turner's personal knowledge of the facts presented, and

notwithstanding the fact that he was subjected to extensive

cross-examination by counsel for the students in every case. In

other words, Petitioners challenged this procedure not on the

substantive grounds of fairness since they were allowed to de

velop fully the basis for the charges, but on the technical evi

dentiary grounds of hearsay.

In Davis v. Ann Arbor Public Schools, 313 F. Supp. 1217

(E.D. Mich. 1970), the Court rejected this same type of tech

nical objection; at page 1227, the Court observed;

“Plaintiff attacks, also, the proceedings before the Board

of Education. He complains that there was no ‘dialogue’,

as he puts it, before the Board, with respect to a list of

charges against him. What the Plaintiff apparently en

visions as required by administrative due process is some-

10 —

thing similar to an indictment, containing various counts,

concerning which he will be tried by the Board of Educa

tion, with cross-examination of witnesses and the other at

tributes of judicial proceedings.

"The plaintiff misconceives the law. The opinion in the

case of Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education,

supra, among others, takes care to point out the indis

putable fact that ‘A full dress judicial hearing, with the

right to cross-examine witnesses, is not required for due

process. Such a procedure, as well as the other panoply of

judicial proceedings, such as discovery, challenges to the

competency of the hearing officers, and the other require

ments of either a civil or a criminal trial, would be totally

at variance with the student-school relationship, would

impose intolerable administrative burdens on the scholastic

community, and would be disruptive of the very function

the school is created to accomplish, namely, the imparta-

tion and acquisition of knowledge in a calm, orderly, and

reflective atmosphere.”

Petitioners were given the opportunity to develop the extent

of Mr. Turner’s investigation and knowledge concerning each

charge. Petitioners were given the opportunity to rebut this

testimony since each student listened to the charges and sup

porting information presented against them by Mr. Turner.

Thus, Petitioners were given every right required by the Four

teenth Amendment as interpreted by the Courts.

11 —

CONCLUSION

For the reasons previously stated, the Order of the Court

below should be affirmed. This appeal presents no substantial

question for review or reconsideration.

Respectfully submitted

Original Signed by

DONALD B. SWEENEY, JR.

MAURICE F. BISHOP

DONALD B. SWEENEY, JR.

603 Frank Nelson Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that copies of the above and foregoing Brief

have been served upon counsels for Appellants via first class

mail, postage prepaid, this 21st day of May, 1973.

Original Signed by

DONALD B. SWEENEY, JR.