Maples v Thomas Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

May 25, 2011

55 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maples v Thomas Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 2011. 0f88553b-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6323b46b-bacd-4d0a-9a7e-d515ad8ba226/maples-v-thomas-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

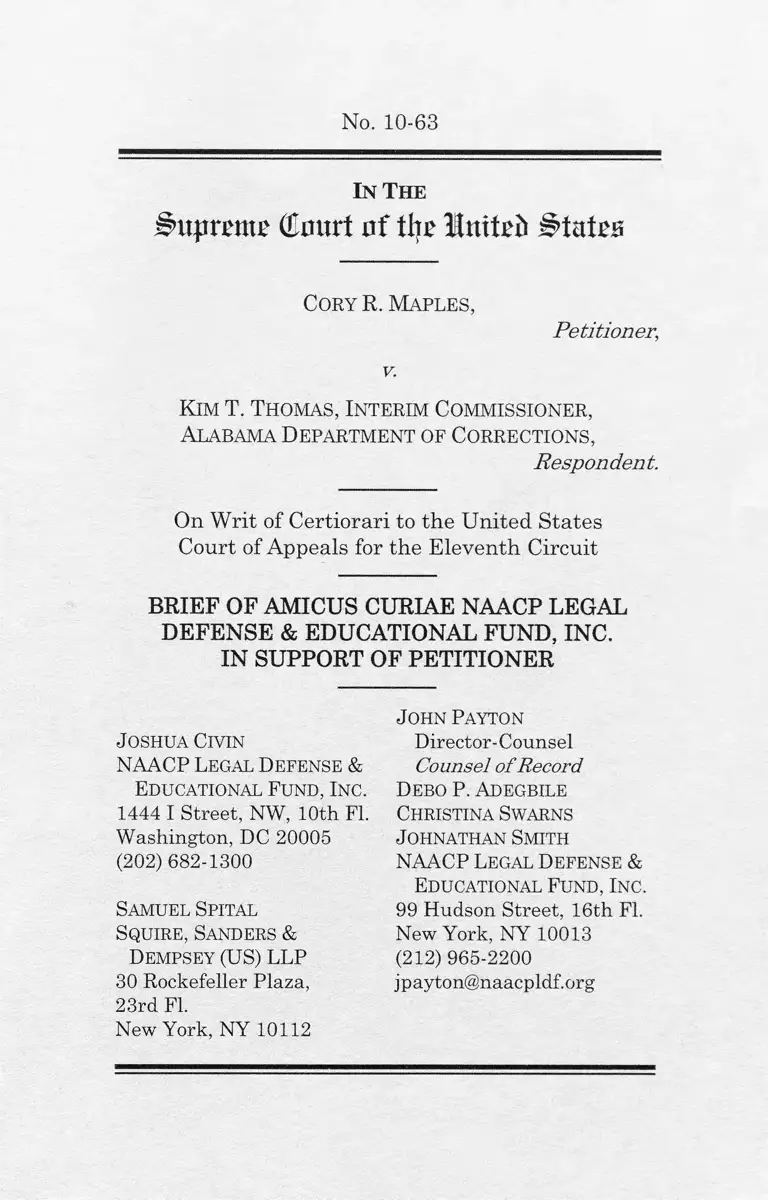

No. 10-63

In The

#ujinmte CEnurt nf the Imteh States

Co r y R. M a p l e s ,

Petitioner;

v.

K im T. T h o m a s , In t e r im C o m m is s io n e r ,

A l a b a m a D e p a r t m e n t o f C o r r e c t io n s ,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

Joshua Civin

NAACP Legal D efense &

Educational Fund , Inc .

1444 I Street, NW, 10th FI.

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Samuel Spital

Squire, Sanders &

Dempsey (US) LLP

30 Rockefeller Plaza,

23rd FI.

New York, NY 10112

John Payton

Director- Counsel

Counsel o f Record

D ebo P. Adegbile

Christina Swarns

Johnathan Smith

NAACP Legal D efense &

Educational Fund , Inc .

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

jpayton@naacpldf.org

mailto:jpayton@naacpldf.org

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS.............................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................. ...iii

INTERESTS OF AMICUS...........................................1

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT........................... 1

ARGUMENT................................................................. 3

I. Giarratano and Coleman establish the

framework for this case....................................... 3

II. Developments since Giarratano and Cole

man have dramatically altered capital

post-conviction practice....................................... 6

A. Significant changes in federal habeas

procedure have magnified the impor

tance of state post-conviction proceed

ings ..................................... 7

B. State post-conviction practice has be

come far more complex, reinforcing the

need for effective counsel............................10

C. While almost all states now require

appointment of capital post-conviction

counsel, this right is severely limited

by law and practice..................................... 15

D. State interests are now more aggres

sively asserted in capital cases................ 20

III. In light of subsequent developments, Giar

ratano and Coleman should be reconsid

ered or at least not extended............................ 22

A. This Court should recognize a consti

tutional guarantee of competent state

post-conviction counsel in capital cases.. 23

B. Short of reconsidering Giarratano, the

Court should recognize a right to state

post-conviction counsel for claims that

could not be pursued in prior litigation .. 26

C. In the alternative, the Court should

hold that a federal habeas petitioner

has cause to excuse procedural default

resulting from state post-conviction

counsel’s errors that would rise to the

level of a constitutional violation if

committed at trial or on direct appeal.... 28

D. Another option would be to find cause

to excuse procedural default in a state

such as Alabama that fails to provide

the minimum constitutional safe

guards that Giarratano requires.............30

E. Coleman and Giarratano should not

be extended to preclude federal habeas

review for a death-sentenced prisoner

abandoned by state post-conviction

counsel......................................................... 32

F. Extension of Coleman and Giarratano

is particularly inappropriate where

the state is aware of, and takes inade

quate steps to address, abandonment

ii

by post-conviction counsel......................... 34

CONCLUSION............................................................36

Appendix: Survey of State Provision of Counsel

for Indigent Death-Sentenced Prisoners in

State Post-Conviction Proceedings..................A -l

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Amadeo v. Zant, 486 U.S. 214 (1988)................ . 35

Ardolino v. People, 69 P.3d 73 (Colo. 2003).......... 27

Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002)................. 25

Banks v. Crosby, No. 4:03-cv-328, 2005 WL

5899837 (N.D. Fla. July 29, 2005)...................... 18

Banks v. Dretke, 540 U.S. 668 (2004).............. 28, 35

Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980).................. 23

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963)................. 27

Brecht v. Abrahamson, 507 U.S. 619 (1993)............ 8

Brooks u. State, 555 So. 2d 337 (Ala. Crim.

App. 1989).............................................................. 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954)....................................................................... 23

Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977)....................... 1

Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S. 722

(1991)...............................................................passim

Commonwealth v. Grant, 813 A.2d 726

(Pa. 2002).................................................................27

Cone v. Bell, 556 U.S. _ , 129 S. Ct. 1769

(2009)..................................................................27-28

Crump v. Warden, 934 P.2d 247 (Nev. 1997)....... 18

Cullen v. Pinholster, 563 U.S. __, 131 S. Ct.

1388 (2011)................................................................8

Damren v. McNeil, No. 3:03-cv-397, 2009 WL

129612 (M.D. Fla. Jan. 20, 2009) 18

IV

Daniels v. State, 561 N.E.2d 487 (Ind. 1990)........ 13

District Attorney’s Office for the Third

Judicial District v. Osborne, 557 U.S. __,

129 S. Ct. 2308 (2009).......................................... 25

Downs v. McNeil, 520 F.3d 1311 (11th Cir.

2008).......................................................................... 9

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)............23

Evitts v. Lucey, 469 U.S. 387 (1985)...........23, 25-26

Ex parte Foster, No. WR 65,799-02, 2010 WL

5600129 (Tex. Crim. App. Dec. 30, 2010).......... 17

Ex parte Graves, 70 S.W.3d 103 (Tex. Crim.

App. 2002)................. 16-17

Ex parte Kerr, No. WR 62,402-03, 2011 WL

1644141 (Tex. Crim. App. Apr. 28, 2011).......... 17

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972).....................1

Gibson v. Turpin, 513 S.E.2d 186 (Ga. 1999)........ 16

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963)........... 21

Gore v. State, 24 So. 3d 1 (Fla. 2009).................... 18

Graham v. Florida, 560 U .S .__130 S. Ct.

2011 (2010)................................................................ 1

Halbert v. Michigan, 545 U.S. 605

(2005)......................................................... 11, 23, 28

Hale v. State, 934 P.2d 1100 (Okla. Crim. App.

1997)............................................................ 18

Hamilton v. Secretary, DOC, No. 08-14836,

2010 WL 5095880 (11th Cir. Dec. 15, 2010)..... 18

Harrington v. Richter, 562 U.S. ___, 131 S. Ct.

770 (2011)........................................................ 10, 24

V

Hazel-Atlas Glass Co. v. Hartford-Empire Co.,

322 U.S. 238 (1944).............................................. 30

Holland v. Florida, 560 U.S. 130 S. Ct.

2549 (2010).....................................................passim

House v. Bell, 547 U.S. 518 (2006)..................... 1, 20

House v. State, 911 S.W.2d 705 (Tenn. 1995)...... 18

Howell v. Crosby, 415 F.3d 1250 (11th Cir.

2005)........................................................................ 18

In re Clark, 855 P.2d 729 (Cal. 1993).................... 13

In re Sanders, 981 P.2d 1038 (Cal. 1999)............. 19

Jackson v. Weber, 637 N.W.2d 19 (S.D. 2001)..... 18

Jefferson v. Upton, 560 U.S. __, 130 S. Ct.

2217 (2010)....................................................... 13-14

Jones v. Flowers, 547 U.S. 220 (2006).............. 35-36

Keeney v. Tamayo-Reyes, 504 U.S. 1 (1992)............. 8

Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407 (2008)............. 1

Lawrence v. Florida, 549 U.S. 327 (2007).......... 29

Lozada v. Warden, 613 A.2d 818 (Conn. 1992).... 18

Manning v. State, 929 So. 2d 885 (Miss. 2006).... 13

Marks v. United States, 430 U.S. 188 (1977)..........4

Massaro v. United States, 538 U.S. 500 (2003).... 27

McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987)................ 1

McCleskey v. Zant, 499 U.S. 467 (1991)....................9

McFarland v. Scott, 512 U.S. 849 (1994)..... 6, 7, 16

Miller v. Maass, 845 P.2d 933 (Or. Ct. App.

1993) 18

V I

Miller-El u. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231 (2005)................... 1

Missouri v. Holland, 252 U.S. 416 (1920)............. 23

M.L.B. v. S.L.J., 519 U.S. 102 (1996)..................... 23

Munafv. Geren, 553 U.S. 674 (2008)..................... 29

Murray v. Carrier, 477 U.S. 478 (1986) .... 33, 35, 36

Murray v. Giarratano, 492 U.S. 1 (1989).......passim

O’Dell v. Netherland, 521 U.S. 151 (1997).............. 4

Pennsylvania v. Finley, 481 U.S. 551

(1987).............................................................. 4, 6, 26

Prowell v. State, 741 N.E.2d 704 (Ind. 2001)........ 14

Rhines v. Weber, 544 U.S. 269 (2005).......................7

Roe v. Flores-Ortega, 528 U.S. 470 (2000).............27

Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551

(2005)...................................................... 1, 23, 24, 25

Schlup v. Delo, 513 U.S. 298 (1995).......... 28, 29, 30

Slack v. McDaniel, 529 U.S. 473 (2000)................ 10

Smith v. Ohio Department of Rehabilitation &

Corrections, 463 F.3d 426 (6th Cir. 2006)..........27

State v. Addison, 7 A.3d 1225 (N.H. 2010)............15

State v. Hunt, 634 N.W.2d 475 (Neb. 2001).......... 18

State v. Mata, 916 P.2d 1035 (Ariz. 1996)............. 18

State v. Zuniga, 444 S.E.2d 443 (N.C. 1994)......... 13

State ex rel. Taylor v. Whitley, 606 So. 2d 1292

(La. 1992)................................................................ 13

State ex rel. Thomas v. Rayes, 153 P.3d 1040

(Ariz. 2007) 27

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668

(1984)......................................................... . 18, 29

Strickler u. Greene, 527 U.S. 263 (1999)................ 35

Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288 (1989)...................... 13

Thomas v. State, 888 P.2d 522 (Okla. Grim.

App. 1994)............................................................... 13

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958).......................... 24

Waters v. State, 574 N.E.2d 911 (Ind. 2004)......... 19

Williams u. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362 (2000).................... 8

Woodford v. Visciotti, 537 U.S. 19 (2002)...................8

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280

(1976)...................................................................... 24

vii

Federal Statutes and Congressional

Materials

Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty

Act of 1996 (AEDPA), Pub. L. No. 104-132,

110 Stat. 1214............................... 7

18U.S.C. § 3599......................................................... 22

28U.S.C. § 2244(b)......................... 9

28 U.S.C. § 2244(d)(1).......................................8-9, 18

28 U.S.C. § 2244(d)(2)......................................... 9

28 U.S.C. § 2254(b)(1)..................... 15

28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)......................................................8

28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(2)................................................ 8

28 U.S.C. § 2254(i)................................................... 26

141 Cong. Rec. 15,016 (1995).................................. 10

V l l l

State Statutes

Ala. Code § 15-12-23(d)............... ......... ...................19

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-4041(F)............................19

Airiz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-4041(G).......................... 19

Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 16-12-201 et seq........................ 13

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 16-12-205(5)............................... 18

Fla. Stat. § 27.711(4)................................ ........... . 19

Mont. Code Ann. § 46-21-105(2)............................. 18

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-1415(a).................................. 12

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-1419(c)........................ 18

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2953.21(A)(2)......................13

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2953.21(I)(2)....................... 18

Ohio Rev. Code. Ann. § 2953.23 ............................. 13

Okla. Stat. tit. 22, § 1089(D)(1).............................. 13

S.C. Code Ann. § 16-3-26(B)(2)................................. 19

S.C. Code Ann. § 17-27-160(B).................................19

Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-30-102(c)................................13

Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-30-106(d).................. 11

Tenn. Post-Conviction Procedure Act, 1995

Tenn. Pub. Acts ch. 207........................................ 11

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 2 (a ).......16

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 2 (b ).......21

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 2A(a).... 19

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 4 ............ 13

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 5 ............ 13

Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-654.1...................................... 12

Va. Code Ann. § 19.2-163.7....................................... 12

Va. Code Ann. § 19.2-163.8(D)..................................18

ix

State Rules and Policies

Ala. R. Crim. P. 32.6(b)............................................ 11

Amendments to Florida Rules of Criminal

Procedure 3.851, 3.852, and 3.993, 797 So.

2d 1213 (Fla. 2001) .............................................. 12

California Supreme Court, Supreme Court

Policies Regarding Cases Arising From

Judgments of Death, § 2-2.1, available at

http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/courts/supreme/

aa02f.pdf.............................. 19

Fla. R. Crim. P. 3.851(e)(1)..................... .......... 11-12

Miss. R. App. P. 22(c)(5)(i)............. 12

Miss. R. App. P. 22(c)(6).............................................12

Other Authorities

American Bar Association, Evaluating

Fairness and Accuracy in State Death

Penalty Systems: The Alabama Death

Penalty Assessment Report (June 2006),

available at http://www.americanbar.org/

content/dam/aba/migrated/moratorium/asse

ssmentproject/alabama/report.authcheckda

m .pdf.......................................................................32

American Bar Association, Evaluaiing

Fairness and Accuracy in State Death

http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/courts/supreme/

http://www.americanbar.org/

X

Penalty Systems: The Georgia Death Penalty

Assessment Report (Jan. 2006), available at

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/ab

a/migrated/moratorium/assessmentproject/g

eorgia/report.authcheckdam.pdf......................... 16

American Bar Association, Evaluating

Fairness and Accuracy in State Death

Penalty Systems: The Ohio Death Penalty

Assessment Report (Sept. 2007), available at

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/ab

a/migrated/moratorium/assessmentproject/o

hio/finalreport.authcheckdam.pdf......................14

Committee on Identifying the Needs of the

Forensic Science Community, National

Research Council, Strengthening Forensic

Science in the United States: A Path

Forward (2009), available at http://www.

ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/nij/ grants/228091.pdf........... 20

Equal Justice Initiative, The Death Penalty in

Alabama (Jan. 2011), available at

http://eji.org/eji/files/02.03.ll%20Death%20

Penalty%20in%20Alabama%20Fact%20She

et.pdf.........................................................................31

Samuel R. Gross et al., Exonerations in the

United States 1989 Through 2003, 95 J.

Crim. L. & Criminology 523 (2005)................... 20

James C. Ho, Defending Texas: The Office of

the Solicitor General, 29 Rev. Litig. 471

(2010) ................................................................................21

Andrea Keilen & Maurie Levin, Moving

Forward: A Map for Meaningful Habeas

Reform in Texas Capital Cases, 34 Am. J.

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/ab

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/ab

http://www

http://eji.org/eji/files/02.03.ll%20Death%20

X I

Crim. L. 207 (2007)................................... 13-14, 17

James R. Layton, The Evolving Role of the

State Solicitor General: Toward the Federal

Model?, 3 J. App. Prac. & Process 533

(2001) .................................................................................. 21

Mark E. Olive, Capital Post-Conviction

Representation Models: Lessons From

Florida, 34 Am. J. Crim. L. 277 (2007).............. 21

Peter Page, State Solicitor General

Appointments Open Doors for Appellate

Practitioners, Nat’l L.J., Aug. 18, 2008...............21

Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Barbour v.

Allen, 551 U.S. 1134 (2007) (No. 06-10605)....... 13

Texas Defender Service, Lethal Indifference:

The Fatal Combination of Incompetent

Attorneys and Unaccountable Courts in

Texas Death Penalty Appeals (2002),

available at http://www.texasdefender.org/

publications#............................................................17

http://www.texasdefender.org/

1

INTERESTS OF AMICUS

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF) is a non-profit legal organization that has

assisted African Americans and other people of color

in securing their civil and constitutional rights for

more than seven decades. LDF has a long-standing

concern with the fair and unbiased administration of

the criminal justice system in general, and the death

penalty in particular. For this reason, LDF has

served as counsel in cases before this Court includ

ing, inter alia, Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972), Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977), McCle-

skey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987), Banks v. Dretke,

540 U.S. 668 (2004), and House v. Bell, 547 U.S. 518

(2006), and it has appeared as amicus curiae in, inter

alia, Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), Ken

nedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407 (2008), and Graham

v. Florida, 560 U.S. 130 S. Ct. 2011 (2010).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Through no fault of his own, Cory Maples faces

execution by the state of Alabama without any

merits review of serious constitutional challenges to

his conviction and sentence. His trial lawyers

admitted to “stumbling around in the dark” due to

their inexperience litigating capital cases. Pet. Br.

8-9. Then, his state post-conviction counsel aban-

1 Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.6, counsel for amicus

state that no counsel for a party authored this brief in whole or

in part, and that no person other than amicus, its members, or

its counsel made a monetary contribution to the preparation or

submission of this brief. The parties have filed blanket consent

letters with the Clerk of the Court pursuant to Supreme Court

Rule 37.3.

2

doned him while proceedings were pending. When

the state court clerk’s office learned this, it did noth

ing to alert Maples before a critical filing deadline

expired.

It is well settled that federal habeas courts have

equitable authority to excuse a state-court proce

dural default such as a missed filing deadline.

Nonetheless, a divided panel of the Eleventh Circuit

held that there was insufficient “cause” to do so here,

notwithstanding the incomprehensible failings of

Maples’s attorneys and the court clerk’s office. As a

result, federal habeas review was entirely foreclosed.

That decision cannot stand. An appropriate rem

edy must account for the developments that have

dramatically altered the legal landscape over the

past twenty years. In Murray v. Giarratano, 492

U.S. 1 (1989), and Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S.

722 (1991), this Court declined to provide constitu

tional or equitable safeguards against incompetent

state post-conviction counsel in capital cases. Since

1991, however, numerous procedural obstacles have

been erected throughout the post-conviction process.

This increasing “complexity . . . makes it unlikely

that capital defendants will be able to file successful

petitions for collateral relief without the assistance

of a person learned in the law.” Giarratano, 492

U.S. at 14 (Kennedy, J., concurring in the judgment).

Although most death-penalty states (with the nota

ble exception of Alabama) have recognized these per

ils and now guarantee capital post-conviction coun

sel as a matter of state law, this right is frequently

under-enforced, and the performance of appointed

counsel is often woefully inadequate.

3

In light of these developments, it would be un

warranted for this Court to extend Giarratano and

Coleman to the distinctive circumstances at issue

here. Maples — sentenced to death in one of the few

states that provides no right to capital post

conviction counsel — was entirely blameless for a

state-court procedural default caused by attorney

abandonment and state misconduct. Accordingly,

amicus agrees with Petitioner that the Eleventh Cir

cuit’s refusal to find cause to excuse the procedural

default in this case should be reversed.

In addition, this case offers the Court an occasion

to take account of the dangerous fissures that have

opened in the post-conviction landscape in the past

two decades and to provide additional safeguards to

ensure that death-sentenced prisoners in Alabama

and elsewhere are not unfairly penalized for attor

ney misconduct that would rise to the level of a con

stitutional violation if committed during trial or on

direct appeal. To this end, amicus sets out a gradu

ated series of protections that this Court could adopt

— either as a matter of constitutional right or

through the equitable principles underlying the

Great Writ of Habeas Corpus.

ARGUMENT

I. Giarratano and Coleman establish the

framework for this case.

The legal foundations for this case trace back to

this Court’s decisions in Giarratano and Coleman.

Decided in 1989, Giarratano held that Virginia

death-row prisoners were not constitutionally enti

tled to increased legal assistance in state post

conviction proceedings. 492 U.S. at 3-4. On behalf

4

of a four-justice plurality, then-Chief Justice

Rehnquist built upon the Court’s prior holding that,

as a general matter, there is “no underlying constitu

tional right to appointed counsel in state postconvic

tion proceedings.” Pennsylvania v. Finley, 481 U.S.

551, 557 (1987). That proposition is settled, and

amicus does not contest it here.

Rather, amicus takes issue with the Giarratano

plurality’s reasoning that this proposition “should

apply no differently in capital cases than in noncapi

tal cases.” 492 U.S. at 10. The Court’s 5-4 decision

did not turn on that categorical pronouncement.

Justice Kennedy’s separate concurrence provides a

more nuanced, fact-sensitive view of the constitu

tional protections for death-sentenced prisoners. Id.

at 14-15 (Kennedy, J., concurring in the judgment).

Because Justice Kennedy’s concurrence is narrower

than the plurality’s reasoning, it is controlling. See

O’Dell v. Netherland, 521 U.S. 151, 162 (1997);

Marks v. United States, 430 U.S. 188, 193 (1977).

Declining to rely on Finley or to import its ration

ale into the capital context, Justice Kennedy agreed

with the four dissenters that “collateral relief pro

ceedings are a central part of the review process for

prisoners sentenced to death” because “a substantial

proportion of these prisoners succeed in having their

death sentences vacated in habeas corpus proceed

ings.” Giarratano, 492 U.S. at 14 (Kennedy, J., con

curring in the judgment). Moreover, he recognized

that “ [t]he complexity of our jurisprudence in this

area . . . makes it unlikely that capital defendants

will be able to file successful petitions for collateral

relief without the assistance of persons learned in

the law.” Id.

5

Nevertheless, Justice Kennedy determined that

the constitutional “requirement of meaningful access

can be satisfied in various ways.” Id. While he rec

ognized that “Virginia has not adopted procedures

for securing representation that are as far reaching

and effective as those available in other States,”

Justice Kennedy concluded that, “ [o]n the facts and

record of this case,” Virginia had met its constitu

tional duty. Id. at 14-15 (emphasis added).

Two years later in Coleman, the Court applied

Giarratano in the federal habeas context. A death-

sentenced prisoner, also from Virginia, argued that

the negligence of his state post-conviction counsel

should provide cause to excuse the procedural de

fault that occurred due to his failure to timely appeal

the state post-conviction trial court’s denial of his

claims. Coleman, 501 U.S. at 752-54. The Court re

jected this argument. Because Giarratano held that

there is no constitutional right to post-conviction

counsel for Virginia death-row prisoners, the Court

concluded that “any attorney error that led to the de

fault of Coleman’s claims in state court cannot con

stitute cause to excuse the default in federal

habeas.” Coleman, 501 U.S. at 757.

Nothing in Coleman suggested any change in the

facts, which were critical to Justice Kennedy’s

pivotal concurrence in Giarratano, concerning post

conviction capital representation in Virginia. Thus,

it was unremarkable that Coleman did not reference

Justice Kennedy’s controlling view in Giarratano

that the facts concerning access to the courts are de

terminative of the post-conviction right to counsel for

death-sentenced persons.

6

Coleman did suggest that a serious aecess-to-

courts problem may arise where post-conviction

counsel’s ineffectiveness prevented review of claims

that could only be fully and fairly litigated for the

first time in post-conviction proceedings. 501 U.S. at

755-56. But Coleman declined to decide whether

there is “an exception to the rule of Finley and Giar-

ratano” in such circumstances. Id. at 755. That

broad question was left unresolved because Coleman

did not challenge the effectiveness of his representa

tion at the trial-court stage of post-conviction review.

Id. at 755-57.

While this Court has subsequently cited Coleman

and Giarratano, see, e.g., McFarland v. Scott, 512

U.S. 849, 855-56 (1994), it has not directly revisited

the scope of those two cases, despite profound

changes in capital post-conviction litigation proc

esses over the past twenty years.

II. Developments since Giarratano and Cole

man have dramatically altered capital post

conviction practice.

Giarratano and Coleman were grounded in the

legal landscape of their time. While Justice Ken

nedy’s Giarratano concurrence encouraged Congress

and the states to experiment with “responsible solu

tions” to the problem of meaningful access to state

post-conviction proceedings, 492 U.S. at 14 (Ken

nedy, J., concurring in the judgment), they have

done just the opposite. Over the past two decades,

federal legislation has imposed additional barriers to

federal review of state capital convictions; many of

these bars are triggered by defaults in preceding

state-court litigation. As a result, state post

7

conviction litigation has become the primary forum

for the vindication of federal constitutional rights,

including the adjudication of claims of innocence.

Simultaneously, state post-conviction procedures

have become more complex, convoluted, and fast

paced.

Furthermore, while almost all death-penalty

states now provide post-conviction counsel in capital

cases as a matter of state law, most have been un

willing to enforce any guarantee of minimally

effective representation. Thus, the representation

provided to death-sentenced prisoners in state post

conviction proceedings is all-too-often woefully in

adequate.

A. Significant changes in federal habeas

procedure have magnified the impor

tance of state post-conviction proceed

ings.

In the twenty years since Giarratano and Cole

man, substantive revisions to federal habeas proce

dure have made state post-conviction proceedings

the primary forum for the presentation and adjudi

cation of federal constitutional claims. In particular,

the enactment of the Antiterrorism and Effective

Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), Pub. L. No.

104-132, 110 Stat. 1214, “dramatically altered the

landscape for federal habeas corpus petitions.”

Rhines v. Weber, 544 U.S. 269, 274 (2005).2

2 Pre-AEDPA, this Court’s “death penalty jurisprudence

unquestionably [was] difficult even for a trained lawyer to mas

ter.” McFarland, 512 U.S. at 856 (citation and quotation marks

omitted). But many pre-AEDPA obstacles emerged in decisions

8

First, AEDPA imposed a “highly deferential stan

dard for evaluating state-court rulings.” Woodford v.

Visciotti, 537 U.S. 19, 24 (2002) (per curiam) (cita

tion and internal quotation marks omitted). Federal

courts may grant habeas relief only when a state-

court “merits” determination “was contrary to” or

“involved an unreasonable application o f ’ this

Court’s precedents, or when the decision “was based

on an unreasonable determination of the facts in

light of the evidence presented in the State court

proceeding.” 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d). Even state-court

decisions that “applied clearly established federal

law erroneously or incorrectly” are irremediable

unless the error is “also . . . unreasonable.” Williams

v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 411 (2000).

Second, AEDPA made it even more critical for pe

titioners to develop the factual basis for all known

claims in state court. Not only is federal habeas

review of certain claims “limited to the record that

was before the state court that adjudicated the claim

on the merits,” Cullen u. Pinholster, 563 U .S .__, 131

S. Ct. 1388, 1398 (2011), but AEDPA also imposes a

restrictive standard for evidentiary hearings in fed

eral habeas proceedings, 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(2). As a

result, “ [although state prisoners may sometimes

submit new evidence in federal court, AEDPA’s

statutory scheme is designed to strongly discourage

them from doing so.” Cullen, 131 S. Ct. at 1401.

Third, AEDPA’s imposition of a one-year filing

deadline for federal habeas petitions has exacerbated

the plight of indigent death-row prisoners. See 28

that post-dated Giarratano. See, e.g., Keeney v. Tamayo-Reyes,

504 U.S. 1 (1992); Brecht v. Abrahamson, 507 U.S. 619 (1993).

9

U.S.C. § 2244(d)(1). Although this statute of limita

tions is tolled while state post-conviction proceedings

are pending, it runs throughout the time that the

state post-conviction petition is prepared for filing,

and it starts running again immediately upon entry

of a final state-court judgment. See id. § 2244(d)(2).

These time limitations make it even more critical for

death-sentenced prisoners to have assistance from

qualified counsel who can efficiently and effectively

research, investigate, and draft a state post

conviction pleading. Otherwise, the petitioner will

be in danger of defaulting claims under state plead

ing requirements or of filing the state pleading so

late in AEDPA’s one-year limitation period that the

time remaining to prepare a federal habeas petition

after a final state-court judgment is inadequate.

See, e.g., Downs v. McNeil, 520 F.3d 1311, 1318 (11th

Cir. 2008) (post-conviction attorneys “waited until

the eleventh hour to file [their client’s] state habeas

petition,” thereby leaving only one business day to

file a federal habeas petition).3

Finally, AEDPA generally prohibits the succes

sive litigation of federal habeas petitions. 28 U.S.C.

§ 2244(b). These restrictions are far more stringent

than those applied pre-AEDPA or, indeed, at the

time that Giarratano and Coleman were decided.

See McCleskey v. Zant, 499 U.S. 467, 493-95 (1991).

Thus, except in extremely limited circumstances, a

death-sentenced prisoner now has only one opportu

nity to seek federal habeas review.

3 Even shorter post-conviction deadlines in many states in

crease the time pressure to adequately investigate and plead

all constitutional claims. See infra at 12-13 & nn.5, 6.

10

The changes outlined above fundamentally al

tered the relationship between state and federal

post-conviction proceedings. Post-AEDPA, a con

demned prisoner’s ability to properly present a fed

eral claim in a state post-conviction forum is literally

a matter of life and death. Federal habeas review is

far more limited and no longer serves as the cure-all

for mistakes of law and fact which occur in state

post-conviction proceedings, as it did when Giar-

ratano was decided. Instead, “state proceedings are

the central process, not just a preliminary step for a

later federal habeas proceeding,” Harrington v. Rich

ter, 562 U.S. 131 S. Ct. 770, 787 (2011), and state

courts’ pronouncements on questions of guilt and

punishment routinely become authoritative.

Nevertheless, this Court recently explained that

“ [w]hen Congress [in AEDPA] codified new rules

governing this previously judicially managed area of

law, it did so without losing sight of the fact that the

‘writ of habeas corpus plays a vital role in protecting

constitutional rights.’” Holland v. Florida, 560 U.S.

__, 130 S. Ct. 2549, 2562 (2010) (quoting Slack v.

McDaniel, 529 U.S. 473, 483 (2000)). Indeed, Con

gress considered and rejected proposals that would

have effectively eliminated federal habeas review for

any claim that had been litigated in state court. See,

e.g., 141 Cong. Rec. 15,016, 15,044-45, 15,066 (1995).

B. State post-conviction practice has be

come far more complex, reinforcing the

need for effective counsel.

The two decades since Giarratano and Coleman

have also seen sweeping changes in state post

conviction rules. Many states have imposed rigid

11

deadlines and procedural restrictions on access to

their own post-conviction forums. As a result, state

post-conviction procedure, like the appellate review

process at issue in Halbert v. Michigan, is an in

creasingly “perilous endeavor for a layperson” to

navigate without the benefit of counsel, and it goes

“well beyond the competence of individuals . . . who

have little education, learning disabilities, and men

tal impairments” — a profile all too common among

death-row prisoners. 545 U.S. 605, 621 (2005).

Since Giarratano, many death-penalty states

have tightened pleading requirements and other

rules governing presentation of federal claims in

state post-conviction proceedings. For instance, leg

islative changes, adopted by Tennessee in 1995, re

quire petitioners seeking post-conviction relief to

plead “a clear and specific statement of all grounds

upon which relief is sought, including full disclosure

of the factual basis of those grounds.” Tenn. Post-

Conviction Procedure Act, 1995 Tenn. Pub. Acts ch.

207, § 1 (codified at Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-30-106(d)).

Tennessee also provides that “bare allegation[s] that

a constitutional right has been violated and mere

conclusions of law shall not be sufficient to warrant

any further [post-conviction] proceedings.” Id.4

Similarly, as a result of post -Giarratano revisions

to Florida rules, petitioners must now meet specific

pleading requirements, including, inter alia, “de

4 Not all such changes have occurred since Giarratano.

This Tennessee provision is almost identical to a long-standing

pleading requirement imposed by neighboring Alabama. See

Ala. R. Crim. P. 32.6(b); Brooks v. State, 555 So. 2d 337, 337

(Ala. Crim. App. 1989).

12

tailed allegation[s] of the factual basis for any claim

for which an evidentiary hearing is sought,” and of

“any purely legal or constitutional claim for which an

evidentiary hearing is not required and the reason

that this claim could not have been or was not raised

on direct appeal.” Fla. R. Crim. P. 3.851(e)(1);

Amendments to Fla. Rules of Crim. P. 3.851, 3.852,

and 3.993, 797 So. 2d 1213, 1218-19, 1228-29 (Fla.

2001). Such heightened pleading standards increase

the necessity of developing specific factual support

for every claim at the initial stage of state post

conviction proceedings, thereby creating a threshold

obstacle that is particularly difficult for a death-

sentenced individual to surmount while confined in

prison without competent counsel.

Further, many death-penalty states have adopted

stringent post-conviction filing deadlines.5 Others

have created “unitary” systems, in which death-

sentenced prisoners must prepare for both direct ap

peal and state post-conviction proceedings simulta

5 For instance, Mississippi rule amendments, adopted in

1996, provide that a capital post-conviction petition generally

must be filed within 30 days following the Mississippi Supreme

Court’s grant of permission to file, and such permission must

be requested no later than 180 days after post-conviction coun

sel is appointed or 60 days following denial of rehearing on di

rect appeal, whichever is later. Miss. R. App. P. 22(c)(5)(i), (6);

see also, e.g., N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-1415(a) (120-day deadline

for most post-conviction capital petitions, adopted in 1996); Va.

Code Ann. §§ 8.01-654.1, 19.2-163.7 (120-day deadline, adopted

in 1998, from the appointment of post-conviction capital coun

sel, which must occur within 30 days of the Virginia Supreme

Court’s decision affirming a death sentence; otherwise a 60-day

deadline, adopted in 1995, applies).

13

neously, shortly after the conclusion of trial.6

Also as a result of changes over the past twenty

years, most death-penalty states now preclude the

filing of successive state post-conviction petitions,

except in very limited circumstances.7 Additionally,

many states have narrowed the scope of relief avail

able in post-conviction proceedings by adopting non

retroactivity rules modeled on those announced by

this Court in Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288 (1989).8

Finally, in Alabama and elsewhere, it has become

prevailing practice for state courts to dismiss capital

post-conviction petitions by adopting verbatim or

ders drafted by state prosecutors, without any judi

cial review of the content of those orders. See Peti

tion for Writ of Certiorari, Barbour v. Allen, 551 U.S.

1134 (2007) (No. 06-10605), at 17-18.9 In a recent

6 Since Giarratano, unitary systems have been adopted in

states such as Colorado, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Texas. See Colo.

Rev. Stat. §§ 16-12-201 et seq. (adopted in 1997); Ohio Rev.

Code Ann. § 2953.21(A)(2) (adopted in 1995); Okla. Stat. tit. 22,

§ 1089(D)(1) (adopted in 1995); Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art

11.071 § 4 (adopted in 1995).

7 For instance, Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas adopted restric

tions on successive petitions in 1995. See Ohio Rev. Code. Ann.

§ 2953.23; Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-30-102(c); Tex. Code Crim.

Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 5; see also, e.g., In re Clark, 855 P.2d

729, 740-45 (Cal. 1993).

8 See, e.g., Manning v. State, 929 So. 2d 885, 900 (Miss.

2006); State v. Zuniga, 444 S.E.2d 443, 446 (N.C. 1994); Tho

mas v. State, 888 P.2d 522, 527 (Okla. Crim. App. 1994); State

ex rel. Taylor v. Whitley, 606 So. 2d 1292, 1296-97 (La. 1992);

Daniels v. State, 561 N.E.2d 487, 489 (Ind. 1990).

9 See also Andrea Keilen & Maurie Levin, Moving Forward:

A Map for Meaningful Habeas Reform in Texas Capital Cases,

34 Am. J. Crim. L. 207, 225 (2007) (hereinafter Keilen & Levin,

14

capital case, the Court “criticized that practice.” Jef

ferson v. Upton, 560 U.S. __, 130 S. Ct. 2217, 2223

(2010) (per curiam). The need for adequate legal

representation is magnified where state judges fail

to play an independent role in protecting petitioners’

rights and, instead, simply countersign orders that

contain unsupported factual findings, nonexistent

procedural defaults, and tenuous legal conclusions

drafted by state prosecutors seeking to invoke every

possible legal ground for rejecting the petitioners’

claims and insulating the case from federal habeas

review.

By tightening deadlines and adopting AEDPA-

like procedural restrictions, states have substan

tially complicated the maze of complex rules that

death-sentenced prisoners must navigate during

state post-conviction proceedings. The most imme

diate effect of these changes is to limit condemned

individuals’ right of meaningful access to a state

post-conviction forum to litigate constitutional chal

lenges to their convictions and sentences. There is,

Moving Forward) (finding that, in 90% of Texas capital post

conviction proceedings between 1995 and 2006, the trial court’s

findings were virtually identical to those submitted by state

prosecutors); Prowell v. State, 741 N.E.2d 704, 708 (Ind. 2001)

(observing that “ [i]t is not uncommon” for Indiana courts “to

enter findings that are verbatim reproductions of submissions

by the prevailing party”); Am. Bar Ass’n, Evaluating Fairness

and Accuracy in State Death Penalty Systems: The Ohio Death

Penalty Assessment Report 264-65 (Sept. 2007), available at

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/morator

ium/assessmentproject/ohio/finalreport.authcheckdam.pdf (sur

veying Ohio post-conviction courts’ practice of “wholesale adop

tion of the State’s proposed finds of fact and conclusions of

law”).

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/morator

15

however, a still more drastic secondary effect. Be

cause the exhaustion of state remedies is generally a

precondition for federal habeas review, 28 U.S.C.

§ 2254(b)(1), states’ purported post-conviction “reme

dies” ensnare prisoners in procedural defaults that

bar their claims in federal court.

C. While almost all states now require ap

pointment of capital post-conviction

counsel, this right is severely limited by

law and practice.

Over the past twenty years, states have increas

ingly recognized that “collateral relief proceedings

are a central part of the review process for prisoners

sentenced to death” and therefore “the assistance of

persons learned in the law” is necessary to navigate

the “complexity” of these proceedings. Giarratano,

492 U.S. at 14 (Kennedy, J., concurring in the judg

ment). When Giarratano was decided, eighteen of

the thirty-seven death-penalty states guaranteed

appointment of state post-conviction counsel for in

digent death-sentenced individuals. Id. at 10 n.5

(plurality opinion); id. at 30 & n.26 (Stevens, J., dis

senting). Today, by contrast, almost all of the thirty-

four states that permit imposition of the death pen

alty provide such a right to counsel — and Alabama

is a distinct outlier among the few that do not.10

10 The appendix to this brief compiles the rules for ap

pointment of capital post-conviction counsel in death-penalty

states. Thirty-one states provide a right to counsel. Of the

three remaining states, New Hampshire has sentenced only

one individual to death since it revised its death-penalty stat

ute in 1977, and his conviction and sentence are still pending

on direct review. See State v. Addison, 7 A.3d 1225, 1256 (N.H.

2010). While Georgia does not guarantee capital post-

16

Notwithstanding this positive trend, most states

severely limit the substance of the right to post

conviction counsel by law or in practice. For in

stance, in eleven death-penalty states, the appoint

ment of post-conviction counsel occurs only after a

post-conviction petition is timely filed pro se. See

Appendix. Even if appointed counsel is permitted to

amend the petition, requiring pro se initiation of

post-conviction procedures can have a substantial

chilling effect. Cf. McFarland, 512 U.S. at 856 (“Re

quiring an indigent capital petitioner to proceed

without counsel in order to obtain counsel . . . would

expose him to the substantial risk that his habeas

claims never would be heard on the merits.”).

Moreover, a paper guarantee of post-conviction

counsel does not ensure quality, or even minimally

adequate, representation, especially in light of the

technical complexity of capital post-conviction re

view. In Texas, for instance, “competent” counsel is

required by statute in capital post-conviction pro

ceedings. Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071

§ 2(a). The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, how

ever, has interpreted this competency requirement

as measuring only counsel’s “qualifications, experi

ence, and abilities at the time of his appointment,”

regardless of performance. Ex parte Graves, 70

conviction counsel, it provides some funding to the Georgia Ap

pellate and Educational Resource Center, which represents

some death-sentenced individuals in state habeas appeals. See

Gibson v. Turpin, 513 S.E.2d 186, 187-88, 191 (Ga. 1999); Am.

Bar Ass’n, Evaluating Fairness and Accuracy in State Death

Penalty Systems: The Georgia Death Penalty Assessment Report

196-97 & n.113 (Jan. 2006), available at

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/mora-

torium/assessmentproject/georgia/report.authcheckdam.pdf.

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/mora-torium/assessmentproject/georgia/report.authcheckdam.pdf

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/mora-torium/assessmentproject/georgia/report.authcheckdam.pdf

17

S.W.3d 103, 113-14 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002). Accord

ingly, the Court of Criminal Appeals has refused to

permit a claim of ineffective assistance of post

conviction counsel to be heard in a successive peti

tion. Id. at 117-18.11 The inadequacies of Texas’s

approach are evident in multiple stories of appointed

post-conviction counsel who failed to raise any cogni

zable or extra-record claims, cut and pasted their cli

ent’s letters into their pleadings instead of writing a

legal claim for relief, used boilerplate pleadings that

failed to change the client name or the facts of the

crime, never visited their client, and failed to con

duct any investigation whatsoever.12

Like Texas, at least ten other death-penalty

states that guarantee a right to post-conviction capi

tal counsel refuse to provide any relief when attor

neys provide ineffective assistance, at least so long

as those attorneys met state qualification standards

11 Ex parte Graves has been called into question by the peti

tioner’s subsequent exoneration, as well as documented exam

ples of extraordinary incompetence by appointed post

conviction counsel in other Texas cases. See Ex parte Kerr, No.

WR 62,402-03, 2011 WL 1644141 (Tex. Crim. App. Apr. 28,

2011) (Price, J., dissenting); Ex parte Foster, No. WR 65,799-02,

2010 WL 5600129, at *2 (Tex. Crim. App. Dec. 30, 2010) (Price,

J., dissenting).

12 See Keilen & Levin, Moving Forward, at 225-32, 239-43,

248-49. Of state post-conviction petitions filed in Texas capital

cases between 1995 and 2006, 12% were less than fifteen pages,

27% contained no extra-record claims, and 38% did not attach

any extra record materials. Id. at 225; see also generally Texas

Defender Service, Lethal Indifference: The Fatal Combination

of Incompetent Attorneys and Unaccountable Courts in Texas

Death Penalty Appeals (2002), available at

http://www.texasdefender.Org/publications#.

http://www.texasdefender.Org/publications%23

18

at the time of their appointment.13 Among these

states is Florida, where there are numerous recent

examples of attorneys appointed to represent death-

sentenced prisoners in state post-conviction proceed

ings who failed to file a federal habeas petition

within AEDPA’s one-year statute of limitations. 28

U.S.C. § 2244(d)(1). In some instances, this was be

cause of their failure to file a timely state petition, in

others because counsel was ignorant of the applica

ble federal laws.14

Even among death-penalty states that do provide

some remedy for ineffective assistance of capital

post-conviction counsel, only a few have adopted the

standard set forth by this Court in Strickland v.

Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984), for determining

whether an attorney is minimally competent.15

Elsewhere, relief appears limited to circumstances

where post-conviction counsel effectively abandoned

13 See, e.g., Gore v. State, 24 So. 3d 1, 16 (Fla. 2009); State

v. Hunt, 634 N.W.2d 475, 479-80 (Neb. 2001); State v. Mata,

916 P.2d 1035, 1052-53 (Ariz. 1996); House v. State, 911 S.W.2d

705, 712-13 (Tenn. 1995); Miller v. Maass, 845 P.2d 933, 934

(Or. Ct. App. 1993); Colo. Rev. Stat. § 16-12-205(5); Mont. Code

Ann. § 46-21-105(2); N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-1419(c); Ohio Rev.

Code Ann. § 2953.21(I)(2); Va. Code Ann. § 19.2-163.8(D).

14 See, e.g., Hamilton v. Secretary, DOC, No. 08-14836, 2010

WL 5095880, at *1-2 (11th Cir. Dec. 15, 2010); Howell v.

Crosby, 415 F.3d 1250, 1251 (11th Cir. 2005); Damren v.

McNeil, No. 3:03-cv-397, 2009 WL 129612, at *1-2 (M.D. Fla.

Jan. 20, 2009); Banks v. Crosby, No. 4:03-cv-328, 2005 WL

5899837, at *3 (N.D. Fla. July 29, 2005).

15 See, e.g., Jackson v. Weber, 637 N.W.2d 19, 22-24 (S.D.

2001); Crump v. Warden, 934 P.2d 247, 303-04 (Nev. 1997);

Hale v. State, 934 P.2d 1100, 1102-03 (Okla. Crim. App. 1997);

Lozada v. Warden, 613 A.2d 818, 842-43 (Conn. 1992).

19

a death-sentenced prisoner.16

In addition, many death-penalty states constrain

counsel in state post-conviction proceedings by limit

ing compensation for legal work, as well as investi

gative and expert assistance. For instance, in the

rare circumstances where Alabama courts appoint

state post-conviction counsel, there is an extremely

low fee cap of $1,000. Ala. Code § 15-12-23(d).17

Lawyers subjected to such a fee cap are prone to do

no more than re-argue the claims raised on direct

review or in their client’s initial pro se post-

conviction pleading. Counsel lack the resources or

incentive to develop additional claims, however meri

torious.

16 See, e.g., Waters v. State, 574 N.E.2d 911, 911-12 (Ind.

2004) (refusing to follow Strickland but allowing a death-

sentenced prisoner “to begin anew his quest for post-conviction

relief’ where “[cjounsel, in essence, abandoned [him]”); In re

Sanders, 981 P.2d 1038, 1041 n.l, 1055 (Cal. 1999) (holding

that “abandonment” by post-conviction capital counsel “is a

relevant factor in determining whether a petition has shown

good cause to justify a delay in presentation of claims”).

17 See also, e.g., Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-4041(F), (G) (cap

ping attorneys’ fees at $100 per hour for up to 200 hours, but

allowing additional compensation for “good cause”); Fla. Stat.

§ 27.711(4) (capping investigative expenses at $15,000 absent

“extraordinary circumstances” and attorneys’ fees at $84,000);

S.C. Code Ann. §§ 16-3-26(B)(2), 17-27-160(B) (capping attor

neys’ fees at $25,000); Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071

§ 2A(a) (capping state reimbursement for attorneys’ fees and

expenses at $25,000, but providing counties with discretion to

exceed this cap); Cal. Sup. Ct., Sup. Ct. Policies Regarding

Cases Arising From Judgments of Death, § 2-2.1, available at

http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/courts/supreme/aa02f.pdf (capping

investigation expenses at $25,000 in some cases and $50,000 in

others).

http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/courts/supreme/aa02f.pdf

20

The combination of funding limitations and the

consequent reluctance of qualified lawyers to accept

appointment are particularly worrisome because ex

culpatory evidence tends to emerge at a relatively

late stage in capital cases and often is revealed only

by advances in DNA technology and growing con

cerns over the reliability of other forensic tech

niques. See, e.g., House v. Bell, 547 U.S. 518, 540-54

(2006); Comm, on Identifying the Needs of the Fo

rensic Sci. Cmty., Nat’l Research Council, Strength

ening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path

Forward 40-44 (2009), available at

http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/nij/grants/228091.pdf.

Thus, even more so than at the time Giarratano

was decided, courts (and the general public) have

come to appreciate that post-conviction proceedings

provide the primary forum for exposing the constitu

tional violations that all too often pervade the inves

tigation, prosecution, conviction, and sentencing of

capital defendants. Cf. Samuel R. Gross et al., Ex

onerations in the United States 1989 Through 2003,

95 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 523, 531-33 (2005)

(finding that erroneous convictions occur dispropor

tionately in capital cases due to special circum

stances that affect the investigation and prosecution

of those cases).

D. State interests are now more aggres

sively asserted in capital cases.

States have increasingly recognized that attor

neys who are experienced in all aspects of state and

federal post-conviction work will achieve better re

sults than less experienced lawyers. While some

death-penalty states fund specialized defender of-

http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/nij/grants/228091.pdf

21

fices specifically to handle post-conviction proceed

ings,18 almost all states have specialized capital ha

beas teams to defend their interests in state and fed

eral post-conviction proceedings. See Mark E. Olive,

Capital Post-Conviction Representation Models: Les

sons From Florida, 34 Am. J. Grim. L. 277, 283

(2007); cf. Gideon v. Wainuiright, 372 U.S. 335, 344

(1963) (“That government hires lawyers to prosecute

and defendants who have the money hire lawyers to

defend are the strongest indications of the wide

spread belief that lawyers in criminal courts are ne

cessities, not luxuries.”).

In addition, there has been a substantial increase

in the appointment of state solicitors general to su

pervise appellate litigation on behalf of their state.

Currently, at least thirty-seven states have solicitors

general or someone with similar responsibilities —

up from approximately eight at the time Giarratano

was decided. See Peter Page, State Solicitor General

Appointments Open Doors for Appellate Practitio

ners, Natl L.J., Aug. 18, 2008, at 1; James R.

Layton, The Evolving Role of the State Solicitor Gen

eral: Toward the Federal Model"?, 3 J. App. Prac. &

Process 533, 534 (2001). In many states, a key func

tion of the solicitor general is to oversee capital ap

pellate proceedings, especially before this Court.

See, e.g., James C. Ho, Defending Texas: The Office of

the Solicitor General, 29 Rev. Litig. 471, 473-74, 487-

93 (2010).

18 Texas did so most recently, establishing the state-funded

Office of Capital Writs to represent in state post-conviction pro

ceedings all prisoners sentenced to death after September 1,

2009. See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 11.071 § 2(b).

22

Thus, what was already an unlevel playing field

has become even more tilted, increasing the impor

tance of effective state post-conviction counsel in

capital cases.19

III. In light of subsequent developments,

Giarratano and Coleman should be re

considered or at least not extended.

The developments of the past twenty years ren

der the assumptions underlying Giarratano and

Coleman worthy of reconsideration. At a minimum,

these developments make it inappropriate to extend

Giarratano and Coleman to the factual circum

stances of Maples’s case. Below, amicus sets out a

graduated series of protections that this Court could

adopt — either as a matter of constitutional right or

through the equitable principles underlying federal

habeas review — to ensure that Maples and other

death-sentenced individuals are not unfairly penal

ized for attorney conduct in post-conviction proceed

ings that would call for constitutional relief if com

mitted by trial or direct appeal counsel.

19 While federal law requires appointment of counsel for in

digent capital offenders in federal habeas proceedings, 18

U.S.C. § 3599, representation at that stage is insufficient by

itself, given that developments since Giarratano and Coleman

have magnified the importance of state post-conviction proceed

ings for the adjudication of federal claims, see Section II.B su

pra, and substantive federal habeas review is generally de

pendent upon adequate presentation of those claims to the

state court, see Section II.A supra.

23

A. This Court should recognize a constitu

tional guarantee of competent state post

conviction counsel in capital cases.

In Giarratano, it was undisputed that the Consti

tution mandates “meaningful access” to state post

conviction procedures which allow for litigation of

constitutional challenges to capital convictions and

sentences. See Giarratano, 492 U.S. at 14 (Kennedy,

J., concurring in the judgment). The only out

standing question was the scope of that mandate.

The meaningful-access right recognized in Giar

ratano is rooted in the requirements of the Sixth

Amendment right to counsel as well as the Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment. See Halbert, 545 U.S. at 610; M.L.B. v.

S.L.J., 519 U.S. 102, 120 (1996); Evitts u. Lucey, 469

U.S. 387, 403-05 (1985). Additionally, the Eighth

Amendment’s demand of heightened reliability in

capital cases implies the need for special attention to

procedural protections when the death penalty is in

volved. See Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 637-38

(1980). These constitutional safeguards evolve as

times and conditions change.20 And so much has

changed since Giarratano was decided that it is now

time for this Court to recognize a constitutional right

to competent state post-conviction counsel in capital

cases.

20 See, e.g., Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551, 560-61 (2005)

(Eighth Amendment); Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 149-

50 & n.14 (1968) (Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments); Broum

v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 492-93 (1954) (Fourteenth

Amendment); cf. Missouri u. Holland, 252 U.S. 416, 433-34

(1920) (treaty power).

24

As detailed in Section II.A supra, state post

conviction proceedings often serve as the only forum

for developing and adjudicating the facts necessary

to establish federal constitutional claims, including

claims of actual innocence, and are the “principal fo

rum” for legal consideration of such claims. See

Harrington, 131 S. Ct. at 787. At the same time,

state post-conviction procedures have become in

creasingly governed by complex and time-sensitive

rules, which are aggressively invoked by expert state

prosecutors to foreclose further consideration of

claims, including through submission of draft orders

that state judges often adopt verbatim. See Section

II.B supra. These developments have combined to

greatly increase the perils facing death-sentenced

individuals who are forced to initiate the state post

conviction process without assistance of counsel.

Putting aside Alabama and a few other states, a

national consensus has recognized these perils and

responded to them by providing counsel for indigent

condemned prisoners at the critical stage of investi

gating, researching, drafting, and filing state post

conviction pleadings. See Section II.C supra. This

Court has regarded such emergent consensus as a

key indicator of ‘“the evolving standards of decency

that mark the progress of a maturing society’” for

Eighth Amendment purposes. Roper v. Simmons,

543 U.S. 551, 560-61 (2005) (quoting Trop u. Dulles,

356 U.S. 86, 100-01 (1958) (plurality opinion)).21

21 Evolving standards regarding appropriate procedures call

for constitutional recognition no less than evolving substantive

norms. See, e.g., Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 289-

94, 301 (1976) (lead opinion). Here, the evolution since Giar-

ratano is at least as dramatic — in its volume, rapidity, and

25

Yet, without a federal constitutional guarantee of

minimally effective counsel in state post-conviction

proceedings, the actual performance of appointed at

torneys for death-row prisoners in most states will

likely remain “fundamentally inadequate to vindi

cate the substantive rights provided.” Dist. Attor

ney’s Office for the Third Judicial Dist. v. Osborne,

557 U.S. _ , 129 S. Ct. 2308, 2320 (2009). The ab

sence of any system for the appointment of state

post-conviction lawyers in Alabama and a few other

jurisdictions, and the inadequacies and underfund

ing of appointed counsel in many other death-

penalty states, mean that the necessary preparation

for timely filing adequate state and federal post

conviction petitions is simply not done. As a result,

it is virtually certain in places like Alabama, and not

at all unlikely in other states, that valid claims of

federal constitutional error will go unidentified, un

developed, or unpresented. In other cases, all post

conviction review is forfeited as a result of missed

state or federal deadlines. See Section II.C supra.

Accordingly, this Court should reexamine Giar-

ratano in light of the significant developments that

have occurred in the intervening years and recognize

that death-sentenced prisoners cannot fairly litigate

constitutional claims raised in state post-conviction

proceedings without a federal constitutional guaran

tee of minimally competent counsel. Cf. Evitts, 469

U.S. at 396 (“[A] party whose counsel is unable to

consistent direction of change — as it was in recent Eighth

Amendment cases where this Court has found a national con

sensus. Compare Roper, 543 U.S. at 564-65, and Atkins v. Vir

ginia, 536 U.S. 304, 313-16 (2002), with Section II.C supra.

26

provide effective representation is in no better posi

tion than one who has no counsel at all.”).22

B. Short of reconsidering Giarratano, the

Court should recognize a right to state

post-conviction counsel for claims that

could not be pursued in prior litigation.

As discussed in Section I supra, Coleman left

open the question of whether there is “an exception

to the rule of Finley and Giarratano in those cases

where state collateral review is the first place a pris

oner can present a challenge to his conviction.”

Coleman, 501 U.S. at 755. Short of overruling Giar

ratano, this Court should recognize the exception

sought by the petitioner in Coleman and hold that

death-sentenced prisoners have a constitutional

right to competent counsel to litigate claims that can

be fully and fairly litigated for the first time only in

state post-conviction proceedings (practically or as a

matter of state law).23

22 As applied in this case, neither this remedial option nor

any other discussed below would implicate 28 U.S.C. § 2254(i).

Maples has not alleged that the ineffectiveness of his post

conviction counsel is a “ground” for federal habeas relief in this

case. Id.; Pet. Br. 13-14. Rather, he has alleged that the mis

conduct of post-conviction counsel (among other things) is

“cause” to excuse the procedural default and reach the merits of

his underlying grounds for relief.

23 Amicus further submits that Coleman should be recon

sidered to the extent it suggests that any such constitutional

right extends only to the initial, or trial, stage of post

conviction proceedings and not to subsequent appeals. See

Coleman, 501 U.S. at 755-56. But reconsideration is unneces

sary in this case because effective assistance at the trial stage

of post-conviction proceedings should unquestionably require

counsel to notify their client of the outcome of that proceeding.

27

Among those claims are alleged ineffective assis

tance of trial and direct appeal counsel. As this

Court has recognized, post-conviction proceedings

are “preferable to direct appeal for deciding claims of

ineffective-assistance” because such claims typically

require investigation and development of a factual

predicate beyond that which is contained in the trial

record. Massaro v. United States, 538 U.S. 500, 504-

OS (2003). It is for this reason that “ [a] growing ma

jority of states” require or encourage defendants to

raise claims of trial and appellate counsel ineffec

tiveness in state post-conviction proceedings. Id. at

508.24

In addition, state post-conviction proceedings are

often the first forum for judicial review of constitu

tional claims based on prosecutorial misconduct,

such as withholding exculpatory or impeachment

evidence in violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S.

83 (1963). Such claims, by their very nature, tend to

surface only after a defendant’s trial and conviction

and require development of predicate facts that are

not part of the trial record. See, e.g., Cone u. Bell,

See Smith v. Ohio Dep’t of Rehab. & Corr., 463 F.3d 426, 433-34

(6th Cir. 2006) (holding that a “court’s ultimate decision re

garding a particular legal proceeding is part of that legal pro

ceeding, and appointed counsel’s duties . . . include the duty of

informing her client of the outcome of the proceeding . . . in a

timely fashion so that the accused retains his control over the

decision to appeal”). In a capital case where “there are non-

frivolous grounds for appeal,” this duty follows a fortiori from

Roe v. Flores-Ortega, 528 U.S. 470, 480 (2000).

24 See, e.g., State ex rel. Thomas v. Rayes, 153 P.3d 1040,

1043-44 (Ariz. 2007); Ardolino u. People, 69 P.3d 73, 77 (Colo.

2003); Commonwealth v. Grant, 813 A.2d 726, 735-38 (Pa.

2002) (cataloging cases).

28

556 U.S. _ , 129 S. Ct. 1769, 1786 (2009); Banks v.

Dretke, 540 U.S. 668, 675-76 (2004).

For such claims, the Giarratano plurality’s rea

soning that “direct appeal is the primary avenue for

review of capital cases,” and that state post

conviction “serve [s] a different and more limited

purpose,” no longer applies. 492 U.S. at 10, 11 (plu

rality opinion). Rather, just as this Court concluded

with respect to the procedures at issue in Halbert,

state post-conviction review of a claim that could not

have been litigated on direct appeal “ranks as a first-

tier appellate proceeding requiring appointment of

counsel” under the Due Process and Equal Protec

tion Clauses. 545 U.S. at 609-10.

C. In the alternative, the Court should hold

that a federal habeas petitioner has

cause to excuse procedural default re

sulting from state post-conviction coun

sel’s errors that would rise to the level of

a constitutional violation if committed at

trial or on direct appeal.

Normally, federal habeas courts will not adjudi

cate claims that are procedurally defaulted by an in

dependent and adequate state rule. This important

practice “is grounded in concerns of comity and fed

eralism.” Coleman, 501 U.S. at 730. Yet the cause-

and-prejudice standard that sometimes excuses pro

cedural default recognizes that — to ensure the

“ends of justice” and vindicate constitutional rights

— federal courts, under some circumstances, must

reach the merits of constitutional claims that were

denied for procedural reasons in state court. See

Schlup v. Delo, 513 U.S. 298, 319-21 (1995). The

29

cause-and-prejudice test is grounded in “‘equitable

principles’ [that] have traditionally ‘governed’ the

substantive law of habeas corpus.” Holland, 130

S. Ct. at 2560 (quoting M unafv. Geren, 553 U.S. 674,

693 (2008)); Schlup, 513 U.S. at 319 (“[T]he Court

has adhered to the principle that habeas corpus is, at

its core, an equitable remedy.”). In applying these

equitable principles, this Court has latitude to de

termine and reevaluate, when necessary, the con

tours of cause and prejudice.

In light of the developments since Giarratano and

Coleman described in Section II supra, competent

state post-conviction counsel is now necessary for the

proper litigation of constitutional claims that go to

the fundamental fairness of a capital conviction and

sentence. But even if this Court declines to use this

case as a opportunity to recognize a federal constitu

tional right to state post-conviction counsel along the

lines proposed in either Section III .A or III.B supra,

it flouts fundamental equitable principles for the

federal courts to refuse to consider the merits of de

faulted claims in a capital case where state post

conviction counsel presents a federal constitutional

claim to the state post-conviction court in a manner

that is so procedurally improper that the conduct

would violate Strickland, 466 U.S. 668, if committed

by trial or direct appeal counsel. That is not to say

that all errors by state post-conviction counsel

should provide cause to excuse a state procedural de

fault. Cf. Lawrence v. Florida, 549 U.S. 327, 336-37

(2007). But where, as in this case, state post

conviction counsel failed to act in a minimally com

petent manner in a capital case, their deficient per

30

formance should satisfy the first prong of the cause-

and-prejudice test.

Although the Court in Coleman was unwilling to

excuse a state procedural default under this line of

reasoning, 501 U.S. at 753-56, the equitable princi

ples underlying federal habeas review allow the

Court to respond to new circumstances where, as

here, there is no statutory provision directly applica

ble. Cf. Holland, 130 S. Ct. at 2563 (‘“The ‘flexibility’

inherent in ‘equitable procedure’ enables courts ‘to

meet new situations that demand equitable inter

vention, and to accord all the relief necessary to cor

rect particular injustices.’”) (quoting Hazel-Atlas

Glass Co. v. Hartford-Empire Co., 322 U.S. 238, 248

(1944) (alterations omitted)). The “equitable inquiry

required by the ends of justice,” Schlup, 513 U.S. at

320, mandates such a reexamination in light of the

developments in post-conviction practice discussed

above.

D. Another option would be to find cause to

excuse procedural default in a state such

as Alabama that fails to provide the

minimum constitutional safeguards that

Giarratano requires.

Justice Kennedy’s controlling concurrence in

Giarratano adopted a fact-sensitive approach to de

termining whether the constitutional right of mean

ingful access to the courts requires recognition of an

ancillary right to appointment of counsel in state

post-conviction proceedings for capital cases. See

492 U.S. at 14-15 (Kennedy, J., concurring in the

judgment).

31

Under this fact-sensitive approach, the present

case stands in stark contrast to Giarratano. Neither

of the two circumstances that Justice Kennedy iden

tified in his concurrence as crucial to the outcome is

true in Alabama today.

First, Virginia’s “prison system [was] staffed with

institutional lawyers to assist in preparing petitions

for post-conviction relief.” Id. at 14-15. Conversely,

Alabama provides neither institutional lawyers nor

any other form of state-funded assistance to help

condemned prisoners prepare petitions for state

post-conviction relief. See Equal Justice Initiative,

The Death Penalty in Alabama 2 (Jan. 2011), avail

able at http://eji.org/eji/files/02.03. ll%20Death%

20Penalty% 20in%20Alabama%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf.

Second, at the time of Giarratano, “no prisoner on

death row in Virginia [was] unable to obtain counsel

to represent him in postconviction proceedings.”

Giarratano, 492 U.S. at 14 (Kennedy, J., concurring

in the judgment). By contrast, some Alabama death-

sentenced prisoners have been unable to secure rep

resentation for all or a significant portion of their

post-conviction proceedings. See Am. Bar Ass’n,

Evaluating Fairness and Accuracy in State Death

Penalty Systems: The Alabama Death Penalty As-

sessment Report 159 (June 2006), available at

http ://www. americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/ migrat

ed/moratorium/assessmentproject/alabama/report.au

thcheckdam.pdf. That number would be far greater

were it not for the support of mostly out-of-state pro

bono resources which, as this case reveals, are not

always a reliable alternative to a state-funded, coor

dinated program.

http://eji.org/eji/files/02.03

32

In light of these and other serious flaws in Ala

bama’s procedures for capital cases, see Pet. Br. 3-6,

the state fails to provide the minimal constitutional

safeguards required by Justice Kennedy’s controlling

concurrence in Giarratano. Indeed, Alabama is a

distinct outlier in comparison to the vast majority of

death-penalty states that provide at least some level

of access to counsel in capital post-conviction pro

ceedings. See Section II.C supra. Neither Giar

ratano nor Coleman justifies rigid application of pro

cedural default rules to death-sentenced prisoners