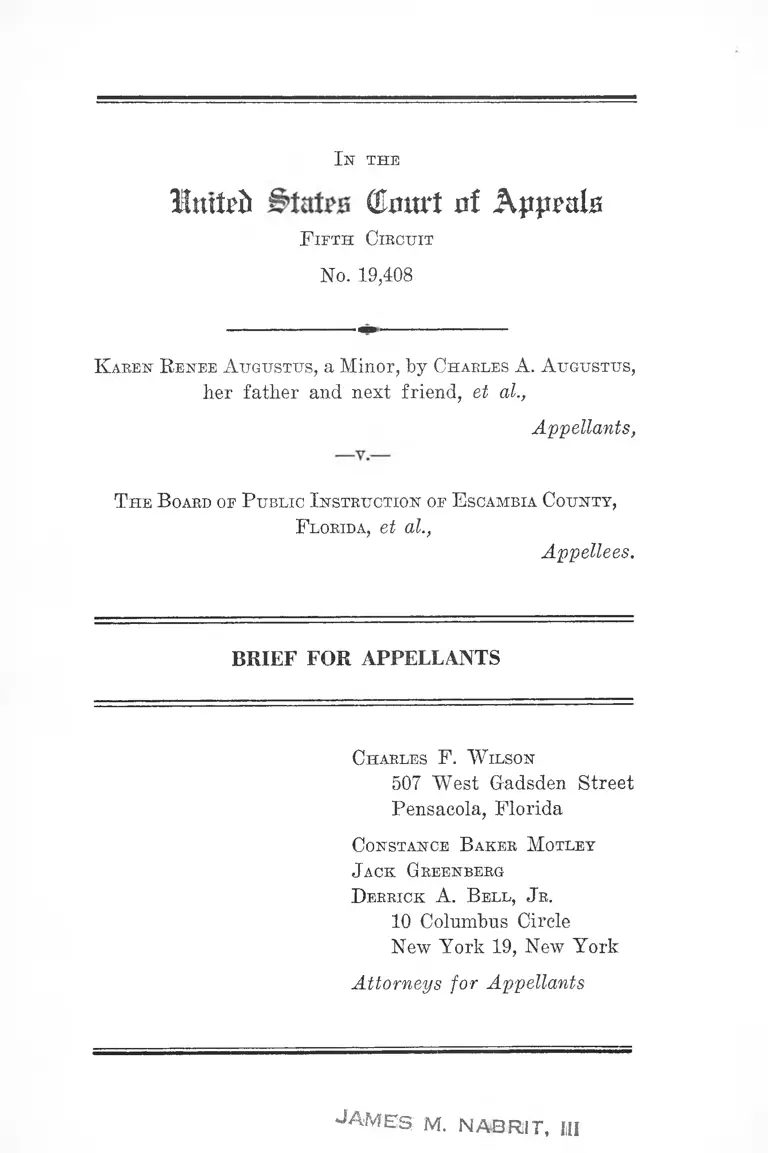

Augustus v. The Board of Public Instruction of Escambia County, Florida Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Augustus v. The Board of Public Instruction of Escambia County, Florida Brief for Appellants, 1961. a6a4ae6c-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/63334907-7299-41c3-9b8c-24c845f7c279/augustus-v-the-board-of-public-instruction-of-escambia-county-florida-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Ituftft (Unmt ni Appeals

F ifth Circuit

No. 19,408

K aren R enee A ugustus, a Minor, by Charles A. Augustus,

her father and next friend, et al.,

Appellants,

T he Board oe P ublic I nstruction of E scambia County,

F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Charles F . W ilson

507 West Gadsden Street

Pensacola, Florida

Constance B aker Motley

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

JAM ES ; M. N A BRIT, HI

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ................

Statement of the Facts .................

Specification of Errors ................

Argument ......................................

Conclusion ..........................................

PAGE

1

9

. 18

. 20

32

Table op Cases

Boson y. Rippy, 275 F. 2d 850 (5th Cir. 1960) ....... ..24, 31

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ...........24, 29

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483 (1954) ....... ...................................... 2, 3,4, 5,19,20,25

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 IJ. S.

249 (1955) ................................................................. 27, 31

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) .....................21, 23, 27

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala. 1949)

aff’d 336 U. S. 933 ... ................................................. 30

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957) ............................... 24

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) ..........5, 24, 26, 30

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915) ............. 30

Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U. S. 971, 350 U. S.

413, 355 U. S. 839 ............ .......... ...................... ........ 24

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach

County, Florida, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) ...... 24, 30

11

PAGE

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939) ........................ 30

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1 (1955) ................ ......-.... 25

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hills

borough County, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960) ....3, 23, 29

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) 25

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936) .... 25

Shuttlesworth v. Board of Education, City of Birming

ham, 162 F. Supp. 372 (M. D. Ala. 1958) aff’d 358

U. S. 101 ................................................................... 30

Sweatt v. Painter, 399 U. S. 629 (1950) ........................ 25

Wilson v. Bd. of Supervisors of L. S. U., 92 F. Supp.

986 (E. D. La., 1950) aff’d 340 U. S. 909 .............. 25

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1896)..................... 30

Statutes

Title 28, H. S. C. §1343(3) .......................................... 2

Title 42, U. S. C. §1983 .............................................. 2

Florida Statutes, Section 230.232 ............................... 10

Other A uthorities

1 Race Relations Law Reporter

(1956) ...................................

237, 921, 924, 940, 961

..................................21, 28

I k the

(Emtrt rtf Appeals

F ifth Ciechit

No. 19,408

K aren R enee Augustus, a Minor, by Charles A. Augustus,

her father and next friend, et al.,

Appellants,

The B oard oe P ublic I nstruction of E scambia County,

F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOB APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This case involves racial segregation in the public school

system of Escambia County, Florida.

The instant appeal is from an order entered September 8,

1961, by the United States District Court, Northern Dis

trict of Florida, Pensacola Division, approving, as modified

by the court, appellees’ so-called plan of desegregation.

After futile desegregation efforts, via petition to ap

pellees in October 1955 and applications of individual

Negro pupils for admission to a white school in 1959, this

action was instituted on February 1, 1960, by the parents

of 12 minor Negro pupils against the Escambia County,

Florida, Board of Public Instruction and its Superintendent

to secure compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision in

2

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483

(1954). Jurisdiction of the court below was invoked pur

suant to the provisions of Title 28, U. S. 0., §1343(3) and

Title 42, U. S. C., §1983.

Appellants are all Negro residents of the county in

volved, parents of minor children eligible to attend and

presently enrolled in public schools of said county, and

bring this action on behalf of themselves and all other

Negro parents of children similarly situated.

Appellees are the Board of Public Instruction of

Escambia County, Florida, a public body corporate, and

William J. Woodham, the Superintendent of Public In

struction, and the individual members of said Board.

Unlike prior school desegregation suits, the relief

sought here was more explicit in terms of what appel

lants sought to accomplish by the action, i.e., a reorgani

zation of the county’s biracial school system into a unitary

nonracial system—including the reassignment of teachers

and principals, as well as pupils, and the realignment of

school attendance area lines on a nonracial basis (R. 9).

In addition, the complaint alleged for the first time in

any Florida case that the responsible school authorities

had not employed the Florida Pupil Assignment Law

(FPAL) as a method of achieving desegregation but had

employed same as a device for maintaining segregation

(R. 8). Consequently, injunctive relief was also sought

against discriminatory application of the assignment law

( R . 9 ) .

Relief was actually sought in the alternative.

First appellants prayed a permanent injunction enjoining

appellees from continuing to operate a biracial school sys

tem, specifically enjoining them from maintaining a dual

scheme or pattern of school zone lines, assigning students

3

on the basis of race and color, assigning school personnel

on the basis of race and color, and enjoining appellees from

subjecting Negro children seeking assignment, transfer or

admission to schools to criteria, requirements, and pre

requisites not required of white children (R. 9).

In the alternative, appellants asked the court to enter

a decree directing appellees to present a complete plan for

the reorganization of the school system into a unitary non-

racial system, including plans for the assignment of pupils

and school personnel on a nonraeial basis, the drawing of

school zone lines on a nonraeial basis, and the elimination

of any other discriminations in the operation of the school

system based solely upon race and color (R. 9-10).

Finally, appellants prayed that the court retain juris

diction of the case pending approval and full implementa

tion of the plan (R. 10).

However, the lower court’s restrictive interpretation of

Brown’s impact on segregated school systems constricted

this approach and narrowed the relief sought to such a

degree as to necessitate this appeal.

On February 19, 1960, appellees filed a motion to strike

and a motion to dismiss. This motion prayed, in the main,

that the court strike those allegations of the complaint

relating to the assignment of teachers on the basis of race

and the relief sought with respect to same (R. 10-16). This

motion also sought to have the complaint dismissed on the

ground that all appellants had not sought reassignment to

a white school and none had exhausted the administrative

remedy provided by the FPAL (R. 13).

On June 24, 1960, the court below denied the motion to

dismiss, citing this Court’s decision in Mannings v. Board

of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) but granted the motion to strike alle-

4

gations relative to assignment of personnel on the ground

that: 1) the Brown decision is limited to the assignment

of pupils, 2) appellants could not he injured by the ap

pellees’ racial personnel practices, and 3) there is no such

mutuality of interest existing between pupils and teachers

as to give the pupils in this instance standing to sue to

redress this grievance (R. 17-29).

Prior to this ruling, on March 15, 1960, appellants took

the deposition of the Superintendent of Public Instruction

(R. 30-66) and moved for summary judgment on April 13,

1960 (E. 16-17). This motion was denied subsequent to

the foregoing ruling, on September 8, 1960, on the ground

that the facts set forth in the deposition in support of the

complaint were insufficient basis for the granting of the

prayer on such a motion (E. 71).

On July 15, 1960, appellees filed their answer in which

they admitted: 1) the existence of the biracial school sys

tem; 2) the dual school zone lines; 3) receipt of the

October 1955 desegregation petition; 4) the individual

attempts to gain admission to a white school by two of the

appellants in 1949; 5) denied the inadequacy of the remedy

provided by the FPAL; 6) denied discriminatory appli

cation of that law, and 7) averred that there is no duty

on the part of school authorities operating segregated

school systems to reassign pupils on a nonracial basis

(E. 66-71).

A pre-trial conference was held following denial of the

motion for summary judgment, pursuant to which the court

entered an order restricting the issues of fact to the

following:

(a) whether or not the plaintiff children, or one of them,

were, or have been or are being, denied admission to

O. J. Semmes Elementary School of Escambia County, due

to race (R. 72).

5

The date set for the hearing was January 16, 1961, and

in the same order the appellee Board was directed to come

prepared to advise the court as to “matters inherent in the

development of a plan for the assignment of pupils in

accordance with the Constitution of the United States and

to advise the Court as to a specific date in which it can

formally submit such plan to it for the consideration of

the Court” (It. 72).

The hearing was held, as scheduled, following which the

court below entered an order on March 17, 1961, granting

appellees “a period of ninety days from the date of this

order to submit . . . ‘a plan whereby the plaintiffs and

members of the class represented by them are hereafter

afforded a reasonable and conscious opportunity to apply

for admission to,’ or transfer to, ‘any schools for which

they are eligible without regard to their race or color and

to have that choice fairly considered by enrolling au

thorities,’ in accordance with the United States Court of

Appeals, Fifth Circuit, Opinion in Gibson v. Board of

Public Instruction of Dade County, Florida, 272 F. 2d 763”

(R. 135-136).

In this order the court found as a fact that “applications

for admission to and transfer within the public schools of

Escambia County are acted upon by the Board of Public

Instruction on consideration of the race or color of the

individual applicants in violation of the constitutional

rights of said applicants as provided by the Supreme Court

of the United States in Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) and subsequent cases”

(R. 135).

Thereafter, on June 14, 1961, appellee Board submitted,

as its plan of desegregation, a resolution adopted by it on

the same date which provides as follows:

6

Be It Resolved By the Board of Public Instruction

of Escambia County, Florida, as follows:

1. That upon approval by The United States District

Court for the Northern District of Florida, on Oc

tober 1, 1961, or at such other time as may be directed

by the Court, the following letter shall be mailed by

the Superintendent of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, Florida, to the parents or guardians of each

child who, according to the school records, will attend

the public schools of Escambia County, Florida, during

the 1961-1962 school term, to-wit:

Dear Parents or Guardians:

This letter is being sent pursuant to Order of the

United States District Court for the Northern District

of Florida.

In order to facilitate the fall opening of school, we

have a procedure known as Spring Registration which

takes place during the 4th week of April in 1962. At

that time, a Pupil Assignment Card is completed at the

school for each pupil enrolled.

While it is the function of the School Administration

to recommend assignments, a parent’s preference of

schools will be fairly considered. You are herewith

advised that you are being afforded a reasonable and

conscious opportunity to apply for admission to any

school for which your child is eligible without regard

to race or color and to have that choice fairly con

sidered by the Board of Public Instruction. If you

wish to exercise your right of preference, you must go

to the school your child is attending at the time of the

Spring Registration and sign a Parent School Pref

erence Card during the period from 23rd through 27th

of April, 1962.

7

The Pupil Assignment Law provides for numerous

criteria in the individual assignments of pupils, such

as attendance areas, transportation facilities, uniform

testing, available facilities, scholastic aptitude, and

numerous other factors, except race.

Should the School Administration recommend as

signment of your child to a school other than the one

you have requested, you will be notified by letter prior

to the fall opening of school. In that event you have

the right to request, in writing, an appearance before

the Board of Public Instruction to have your preference

further considered. If such a request for hearing is

received, you will be notified of the time and place of

the hearing.

Application for Reassignment may be made at any

time when a change of residence address or other ma

terial change in circumstances arises.

Sincerely,

Superintendent

2. That admissions and transfers of pupils will be

made by this Board pursuant to the provisions of the

Florida Pupil Assignment Law.

Appellants filed their objections to this so-called plan on

June 30, 1961 (R. 139-147), and on August 17, 1961, filed

a proposed alternate plan of desegregation which provided,

first, for the reassignment of all students pursuant to non-

racial school attendance area lines based on capacity of

each school and, secondly, for the reassignment of school

personnel on a nonraeial basis, i.e., qualification and need

(R. 143).

8

A hearing was held on appellees’ proposed plan on Au

gust 17, 1961, and on September 8, 1961, the court adopted

same with the following modifications: 1) that the plan

apply to all public schools under the jurisdiction of appel

lees, including the two junior colleges, 2) the letter to

parents shall be mailed on or before October 16, 1961, and

shall specify, in addition, the hours of 7:30 A.M. to 6 :00

P.M. for the period 23rd through 27th of April, 1962, dur

ing which parents and guardians may exercise their right

of preference, 3) parents were to be notified on or before

July 15th of denial of applications for transfer (R. 145-

146). The court retained jurisdiction for the entry of fur

ther orders (R. 146). No provision was made for the notifi

cation of parents of children entering school or moving

into the county for the first time of their right to exercise

a choice of schools which would be considered without re

gard to race. Needless to say, no provision was made for

the assignment of personnel on a nonracial basis; but

neither was any provision made or order entered for the

redrawing of school zone lines on a nonracial basis. Finally,

and perhaps of the most crucial importance, no injunction

was issued against consideration of race as a basis for

admission, assignment, continuance or transfer of any

pupils and no injunction issued against discriminatory ap

plication of the FPAL.

From this order, appellants filed their notice of appeal

to this Court on October 3,1961.

9

Statement of the Facts

E scam bia C ounty’s School P opu la tion

Escambia County’s total school population is relatively

small with a proportionately small Negro enrollment. Out

of a total school population of approximately 37,000, ap

proximately 28,521 are white pupils and 8,557 are Negro

pupils (R. 35-36, 51-52). There are only 63 schools in the

entire county—47 white and 16 Negro (R. 51-52). In Pen

sacola, which is the county’s largest city, the schools are

divided into elementary, junior high and senior high school

units. In the rest of the county, each school contains grades

1 through 12 (R. 52, 54). In addition, the appellee Board

has under its jurisdiction two junior colleges—Washington

Junior College (Negro) and Pensacola Junior College

(white) to which Negroes have applied. It also operates

an adult education program on a racially segregated basis

(R. 52). The one technical high school in the county is

limited to white students (R. 55).

School T ran sporta tion System

Students who live two or more miles from the school to

which they are assigned are eligible for transportation to

and from school (R. 49). However, Escambia County’s

school transportation system is also segregated. The buses

which service the Negro schools do not also service the

white schools (R. 50).

Teacher A ssignm ent P olicy

In accordance with long established policy, custom and

usage, Negro teachers and principals are assigned to Negro

schools and white teachers and principals are assigned to

white schools (R. 50-51, 60). The regular teaching staff is

10

augmented by 36 special teachers who teach retarded chil

dren, crippled children, children with hearing defects,

speech defects and sight impairment, all on a segregated

basis (R. 59). Even in-service training courses for teachers

are offered on a segregated basis (R. 60). Negro and white

principals meet together only as members of special admin

istrative committees (R. 60). Above the principal level,

there are three Negroes in supervisory capacities in the

school system. One of these Negro staff members super

vises the Negro elementary schools (R. 61). The other two

are visiting teachers who work in the area of attendance

and with problems related to the school and the home (R.

61).

A dm in istra tion o f the F lorida P u pil A ssignm ent Law

On August 22, 1956, approximately one month after the

Florida Pupil Assignment Law1 was adopted, appellees

adopted a resolution purporting to implement the provi

sions of that law in Escambia County.

This resolution, adopted virtually verbatim each year

thereafter (R. 49, PI. Exhs. A, B, C, D) provided in the

1959-60 school year for the blanket reassignment of all

students then enrolled in the schools to the schools which

they attended the preceding year. Those students who were

graduating from an elementary or junior high school were

assigned to the schools which they would have attended

the preceding year had they then been so promoted. As

a result of this blanket reassignment, all Negro pupils were

automatically reassigned to Negro schools and all white

1 Florida Statutes, Section 230.232, adopted by Chapter 31380

of the session laws of Florida enacted by the 1956 Special Session,

approved July 22, 1956, amended by Chapter 59-428 of the 1959

Florida Legislature.

11

pupils were ipso facto reassigned to white schools (R. 36-

37).

New children were assigned pursuant to application made

by the parent for admission of the child to a school. The

resolution required that these applications be made on

forms approved by the appellee Board and submitted to

the Superintendent for transmission to the Board for ac

tion. The resolution further required that such initial as

signments be made pursuant to all of the provisions of the

FPAL (R. 49).

The Board reserved to itself the right to reassign any

pupil at any time whenever in the opinion of the Board,

upon consideration of the factors set forth in the FPAL,

such reassignment would be in accord with the intent and

purpose of that law.

Pupils desiring to transfer from schools to which they

have been assigned are permitted to do so on written appli

cation of the parent, at least ten days prior to opening of

school or ten days prior to the date reassignment is desired

or such other date as the Board may specify, on forms

approved by the Board and made available in the principal’s

or superintendent’s office. The resolution required such ap

plications to state in detail the specific reasons why reas

signment is requested, the specific reasons why the appli

cant thinks the child should be admitted to the school to

which his admission is sought, together with such other

information as may be requested by the Board. An incom

plete application would not be considered. The application

was required to bear a date on which and by whom received.

The 1959 resolution provided further that these transfer

applications be considered by the Board “at the earliest

practicable date”, and if reassignment be granted, the ap

plicant and principals of the schools concerned be promptly

12

notified. If the application was denied, the applicant was

to be promptly notified, and, if a hearing was requested,

the applicant was to be advised as to the time and place.

He was to have the right to be heard and to present wit

nesses in support of his application. Applicants’ evidence

could be countered by evidence received in opposition or the

Board might investigate any objections to the granting of

the application. Moreover, the Board might, on its own

motion, examine the child. A decision on the transfer was

to be rendered “as early as may be practicable” and the

applicant to be promptly notified in writing. A permanent

record of proceedings and evidence was to be kept. Eight

categories of criteria were to be employed by the Board in

rendering decisions on these applications for reassignment:

1. Adequacy and availability of educational facilities,

2. The request or consent of the parent or guardian or

the person standing in loco parentis to the pupil,

3. Effect upon established educational program,

(a) Suitability of curriculum to needs and interest

of students,

(b) Summary statement from teachers regarding so

cial acceptance of students being reassigned,

(c) The effect of admission of new pupils on the aca

demic progress of the other pupils enrolled in a

particular school,

4. Scholastic aptitude as measured by standardized tests,

5. Mental ability as measured by standardized tests,

(a) The adequacy of a pupil’s academic preparation

for admission to a particular school,

6. School citizenship records and academic grades,

13

7. Sociological attributes based upon standardized tests

and personal investigation,

(a) Social attitudes, adjustment, and maturity as

measured by standardized tests,

(b) Socio-Economic background,

8. Health, safety, and economic welfare of students and

their families.

The Superintendent testified that because of the large

number of children seeking reassignment many of them

have been reassigned pending the administration of certain

tests (E. 48-49). However, with respect to those pupils who

sought reassignment during the school year 1960-1961 and

whose applications were acted upon by the Board, these

applications appear to have been granted or denied simply

in terms of availability of space in the school to which re

assignment is sought (PI. Exh. 9, E. 89-90).

Moreover, these applications were segregated on a racial

basis, i.e., Negro and white applications were separated

(E. 91-92).

Appellant Augustus applied for admission of his daugh

ter to the 0. J. Semmes Elementary School (white), on

May 13, 1959 (PI. Exh. F). Minor appellant Karen Renee

Augustus had not previously attended school and was, eli

gible for admission to the first grade in September 1959.

The application was submitted to the Superintendent and

the Board which considered same and assigned the Au

gustus child to the Brown-Barge School (Negro) (PL Exh.

F). The Brown-Barge School is approximately 15 blocks

from the Augustus home (PL Exh. F). Only two blocks

away is the Semmes School (E. 111-112). The Superinten

dent testified that the Augustus child lives nearer to the

Semmes School but was assigned to the Brown-Barge

14

School because of race and pursuant to the attendance area

delineation which showed that as a Negro student living

at the address given she was in the Brown-Barge School

zone (R. 42). There is no question that the sole basis for

this assignment was race.

The Superintendent testified (R. 43):

“Q. When the Augustus child was assigned to the

Brown-Barge School rather than the school nearest

her residence, which is the 0. J. Semmes Schools, she

was assigned on the basis of race, was she not? A.

Yes.”

Thereafter, appellant Augustus appealed to the Florida

State Board of Education where his appeal was denied on

the ground that he had not asked for a hearing after the

denial before the local Board (PI. Exhs. H, I). He sub

sequently requested a hearing before the Board in reply

to which he received a letter dated November 25, 1959 sug

gesting to him that he might file an application for “reas

signment” since his daughter had already been assigned to

the Brown-Barge School (PI. Exh. 8). Appellant Augus

tus did not pursue this suggestion.

Appellant Robinson applied for reassignment of her

child to the Semmes School in May 1959 (PI. Exh. E). At

that time, the Robinson child was enrolled in the third grade

of the Brown-Barge School (R. 46). This application was

denied on the recommendation of the Superintendent to

the Board (R. 46). This recommendation was assertedly

based upon the following:

1. The Robinson child scored 2.6 in reading on the Cal

ifornia Mental Maturity Test which was administered to

her after she sought admission to the Semmes School, the

median for the Semmes School being 5.3 and the national

average being 4.0 (R. 106-107). However, the principal of

15

the Semmes School admitted upon cross-examination that

white children who scored 2.6 in reading on this test, which

is given to all students in the school system (R. 109), are

not excluded from or denied admission to the Semmes

School for this reason (R. 111).

2. The Robinson child was also denied admission to the

Semmes School because in the “judgment” of and in the

“opinion” of the teachers, “she would not be accepted by

the other children because of her race” (R. 44-45). A simi

lar subjective test was not applied in any other transfer

case (PI. Exh. 9).

3. The Superintendent added that he did not recommend

reassignment of this child because the reasons given for

her assignment were “insufficient” and because the Semmes

School was overcrowded (R. 46). But the evidence shows

that white students were admitted to the Semmes School

after the Robinson child applied for reassignment, despite

the overcrowded condition (R. 122-123) and, as Plaintiffs’

Exhibit 9 demonstrates, reasons assigned for transfer by

other parents were similar but seldom controlling.

When Mrs. Robinson sought a hearing before the Board,

she received a letter from the Superintendent dated No

vember 25, 1959 (PI. Exh. J) the pertinent provisions of

which follow:

“I have been further advised to request that in view of

your request for a hearing on this application for re

assignment that an amended application for reassign

ment be filed which states in detail the specific reasons

reassignment is requested and specific reasons why you

think your daughter should be admitted to the 0. J.

Semmes Elementary School, which take into account

sociological, psychological, ethical, cultural background

and social scientific factors which might relate to,

16

or cause possible socio-economic class consciousness

among the pupils already attending the 0. J. Semmes

Elementary School and your child, and the reasons you

believe your child will make a normal adjustment to

this change in environment and will not be prevented

from receiving the highest standard of instruction

within her ability to understand and assimilate.

Upon the receipt of this amended application, this

Board will as soon as reasonably possible thereafter

give full consideration to the amended application.”

Appellant Robinson did not pursue this request for hear

ing but, instead, along with appellant Augustus and the

others, instituted this action.

The Superintendent acknowledged, without equivocation,

that this Board’s implementation of the FPAL has not

resulted in any Negro students being assigned to white

schools or in any white students being assigned to Negro

schools:

“Q. Since August 22, 1956, you have been operating

pursuant to the Pupil Assignment Resolution? Is that

right? A. Yes.

Q. Would you tell me what has happened with re

spect to the operation of the schools on a racially segre

gated basis pursuant to this Resolution since you have

been operating under it. A. There has been no change

in the operation of our schools.

Q. There has not been any change in the racial com

position of your schools since this law went into effect?

A. No” (R. 34-35).

And, as the Superintendent testified, the Board has never

considered any plan of desegregation other than the FPAL

(R. 55-56).

17

After the first Board resolution was adopted in 1956, and

after the adoption of subsequent resolutions, no communi

cation was sent by the Board to parents to the effect that

the policy of racial segregation had been abandoned and

applications for admission or transfer would be considered

without regard to race (R. 57-58). A copy of the resolutions

were sent to the principals (R. 57), but the Superintendent

has never discussed with the principals or the teachers de

segregation of the schools (R. 61).

School Zone Lines

Prior to adoption of the FPAL, students were assigned

to school in accordance with school attendance area lines

(R. 70). Adoption of the FPAL, however, did not terminate

this simple pupil assignment plan. Students are, in fact,

still so assigned. The record here discloses that each white

elementary school (PI. Exh. 2), junior high school (PI. Exh.

4) and senior high school (PL Exh. 6) is assigned an atten

dance area. The same with respect to each Negro elemen

tary (PL Exh. 3), Negro junior high (Pl. Exh. 5) and senior

high (Pl. Exh. 7). Where Negroes and whites live in the

same area, these attendance lines overlap (R. 101, 103, 111-

112). For example, the Augustuses live in the Semmes

school zone as well as the Brown-Barge school zone (R. I ll-

112) and the Robinson child lives in the McMillan Elemen

tary School zone (white) (R. 112) as well as in the

Brown-Barge school zone.

Negro P upils Pass W hite Schools to A ttend

M ore D istant Negro Schools

Upon the trial, appellant Tolbert testified that three of

his sons attend Washington Senior High School, one daugh

ter attends Washington Junior High School, and one son

attends John A. Gibson Elementary School. These are all

IS

Negro schools. The Pensacola High School (white) is

nearer to the Tolbert home (2% miles) than the Washing

ton High School (6 miles). The Warrington Junior High

School (white) is nearer to the Tolbert home (1% miles)

than the Washington Junior High School (5 miles). The

son who attends the Gibson Eelmentary School is closer

to the Navy Point Elementary School (white) which is

located about two blocks from the Tolbert home. The Tol

berts live in Warrington, Florida (E. 100-101).

Appellant White also testified on the trial. Both of his

children, a son and a daughter, attend Spencer Bibb Ele

mentary School (Negro). The 0. J. Semmes School is

closer (about % mile) to their residence than the Bibbs

School (% of a mile away) (E, 102-104).

Specification of Errors

The court below erred in :

1. Striking from the complaint those allegations relat

ing to the assignment of teachers, principals and other

school personnel on the basis of race and the relief sought

with respect thereto.

2. Failing to enjoin appellees from considering race

with respect to the admission, assignment or transfer of

pupils to schools under their jurisdiction.

3. Failing to enjoin appellees from applying tests and

criteria to Negro students for admission to white schools

not applied to white students.

4. Failing to enjoin appellees from applying the criteria

of the Florida Pupil Assignment Law only to those pupils

seeking transfers.

19

5. Failing to enjoin appellees from maintaining a dual

scheme or pattern of' school zone lines based upon race and

color and in failing to require appellees to redraw all school

zone lines based upon school capacity and without regard

to race and color for each school.

6. Failing to enjoin appellees from assigning teachers,

principals and other professional school personnel on the

basis of race and color.

7. Failing to immediately enjoin appellees from continu

ing to exclude qualified Negro applicants from the Pensa

cola Junior College and adult education program presently

limited to white students.

8. Failing to immediately enjoin appellees from exclud

ing qualified Negro students from the county’s only techni

cal high school.

9. Failing and refusing to require appellees to make a

prompt and reasonable start in September 1961 toward full

compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision in the Brown

case.

10. Failing and refusing to require appellees to come

forward with a plan for the reorganization of the entire

school system into a unitary nonracial system as prayed

for by appellants in their complaint.

20

A R G U M E N T

I.

Appellants are entitled to an injunction enjoining the

operation of the Escambia County school system on a

completely segregated basis.

The record in this case, despite the restrictive nature of

the rulings below, shows, conclusively, that Escambia

County has a dual public school system, the sole justifica

tion for which is the continuation of a racial policy held

constitutionally void as applied to public education eight

years ago by the United States Supreme Court in Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

One system of schools (consisting of elementary, junior

high and senior high school units in the City of Pensacola

and first through twelfth grade units in the rest of the

county) is operated for the exclusive attendance of white

pupils. These schools are staffed by white teachers, prin

cipals, and other white professional personnel. A similar

but separate system of schools is operated for the exclu

sive attendance of Negro pupils, re-emphasized by the

racial complexion of the schools’ personnel. The systems

are so separate that in-service training courses offered to

teachers are segregated and the Negro and white prin

cipals meet jointly only on special administrative problem

committees. The Negro elementary schools are even super

vised by a Negro on the Superintendent’s staff and the two

Negro Visiting Teachers, concerned with attendance and

home-school problems, are restricted to the Negro schools.

The racial separation policy operates to limit the county’s

only technical high school to white students. Above the

high school level, two junior colleges, one for Negroes and

one for whites, and a segregated adult education program

21

completes the county’s totally segregated public education

structure. In short, Escambia County has not one school

system but two with color providing the standard for

division.

This dual system, of course, originated in Escambia

County in the same way that other segregated southern

school systems had their origins, but in 1954 segregated

public education was held to be violative of the equal pro

tection clause of the 14th Amendment to the Federal Con

stitution, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra,

thus placing upon all public school authorities operating

racially segregated public school systems the duty to re

organize the biracial school systems which they had estab

lished into unitary nonracial systems. Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 7 (1958).

In July 1956, Florida adopted a pupil assignment law

which purported to meet this new duty on school officials.2

This law placed upon the Boards of Public Instruction of

each county the duty of assigning pupils to school in ac

cordance with a number of criteria set forth therein.

Promptly, the school authorities here, following the sug

gestions of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of

Florida, adopted a resolution on August 22, 1956 embracing

the FPAL as the basis for assigning pupils to school and

the suggested rules and regulations for its implementation.3

The problems of en masse reassignment were resolved the

first year by blanket reassignment of all pupils then en

rolled on the basis of race; new pupils were to be admitted

and transfers were to be granted in accordance with the

statute’s criteria. Each year thereafter a similar resolu-

2 Florida Statutes, 230.232. See also, 1 Race Relations Law

Reporter 237, 921, 924, 961 (1956).

3 1 Race Relations Law Reporter 961 (1956).

22

tion was adopted. However, as a result of continued ad

herence to the State Superintendent’s suggestions within a

racially segregated context rather than their spirit in a

context of desegregation, no Negro pupil was ever assigned

to an all-white school and no white pupil was ever assigned

to an all-Negro school.

A Negro parents’ desegregation petition to the Board in

October 1955, requesting compliance with the Supreme

Court’s decision in the Brown case, was not even considered

(R. 51).

After the FPAL had been in operation for about three

years, two of the appellants sought admission of their

children to the 0. J. Sernmes School, a white school nearer

to their residences than the Negro school to which they had

been assigned. Admission to Sernmes was not only denied,

but appellants were required to meet an obviously undem-

onstrable burden of proof (PL Exh. J).

In short, there has been no desegregation in Escambia

County of any description since the Supreme Court’s de

cision in 1954.

This suit was instituted February 1, 1960 and in August

1961, when the court entered an order adopting appellees’

proposed plan of desegregation, no desegregation had taken

place as of that time.

Under this alleged plan, the unconstitutional status quo

is retained, with Negro pupils being given an opportunity

to apply for transfer to “white” schools, effective Septem

ber 1962.

In their answer, appellees admit the existence of racial

segregation in the school system but deny that there is

any duty upon them to reassign pupils on a nonraeial basis.

Appellees say:

23

“Defendants deny that racial intermixture of pupils,

or a general realignment of pupils in a segregated

school system inherited by these Defendants are legally

necessitated by the decisions of the Supreme Court of

the United States in the School Segregation Cases and

the permitting.of the continuance of already existing

racially separate schools is consistent with the Con

stitution so long as there is no official compulsion pres

ent. These Defendants deny that they have officially

compelled the Plaintiffs or any other persons to submit

to any sort of racial discrimination” (E. 68).

The evidence shows, however, that appellees have offi

cially compelled the appellants and others to submit to

racial discrimination. The threshold question here, there

fore, is not whether under the Brown decision “racial inter

mixture of pupils” is necessitated but whether there is any

duty on school authorities to desegregate.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1 (1958) settled, beyond dispute, that after its deci

sions in the Brown case in 1954 and 1955, “State authorities

were thus duty bound to initiate desegregation and to bring

about the elimination of racial discrimination in the public

school system.” (At p. 7.) This duty, now resting upon

school authorities, was recognized and affirmed by this Court

in Manning v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough

County, 277 F. 2d 370, 374 (5th Cir. 1960).

Consequently, there can be no doubt that desegregation

of officially created segregated school systems is required

by the Brown decision. And this duty is manifestly not

discharged by continuing to operate a biracial school system

which now provides, as a result of court action, an oppor

tunity to apply for a transfer to a “white” school and be

subjected to a myriad of tests, both objective and sub-

24

jective, which have not been applied to the white pupils

already in attendance or seeking transfers thereto. Gibson

v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County, Florida,

246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957); Gibson v. Board of Public

Instruction of Dade County, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959);

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach

County, Florida, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958); Manning

v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, su

pra. There is no decision in this Circuit, or any other, which

sustains appellees’ contention that continued racial segre

gation is consistent with the Constitution. Addition of the

phrase: “ . . . so long as there is no official compulsion

present,” does not meet the problem presented by this rec

ord since the segregation complained of here is officially

imposed segregation and not voluntary segregation.

Appellants were, therefore, entitled, either immediately

or ultimately, Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at p. 7, to an in

junction enjoining appellees from continuing to operate a

biracial school system in Escambia County. And even

where school authorities are given an opportunity to make

arrangements for a complete transition to a non-segregated

school system, district courts have been directed to require

a prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance.

Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at p. 7; Boson v. Hippy, 275 F. 2d

850 (5th Cir. 1960); Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir.

1960).

Moreover, the court below was clearly in error in not

immediately enjoining the policy of excluding qualified

Negro applicants from the Pensacola Junior College

(white), the adult education programs, and the county’s

only technical high school. The considerations which form

the basis for postponement of injunctive relief in public

school cases do not apply to the college level, Hawkins v.

Board of Control, 347 U. S. 971, 350 U. S. 413, 355 U. S. 839;

25

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1, and the state’s failure to pro

vide separate but equal educational facilities for Negroes

required immediate injunctive relief even prior to the

Brown case. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950); Wilson

v. Bd. of Supervisors of L. S. U., 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La.,

1950) aff’d, 340 U. S. 909; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337 (1938) ; Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182

A. 590 (1936).

II.

The Brown case requires the elimination of racial dis

crimination from the entire public school system.

The use of race as a criterion in appellees’ operation

of Escambia County’s public school system is by no means

limited to the assignment of pupils. Race is a major test

for staff placement. Negro schools are not evidenced by

the fact that all the pupils are Negro but by the fact that

in front of every class is a Negro, the principal is a Negro,

all the special teachers are Negro, the visiting teachers are

Negro, and the supervisors are Negro.

Appellants alleged that they, and members of their class,

are also injured by this policy. It is predicated upon the

same theory upon which racial assignments of pupils is

predicated, i.e., the policy of separating the races is

usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro

group.” Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483, 494 (1954). Appellants claimed this to be an irrepara

ble injury and asked for injunctive relief (R. 7, 9). Ap

pellees’ motion, to strike these allegations was granted

(R. 10-16, R. 27-29). In entering an order striking these

allegations, the court below ruled that: 1) the Brown de

cision is limited to the assignment of pupils, 2) appellant

could not be injured by appellees’ racially discriminatory

26

personnel assignment policy, and 3) there is no such com

munity of interest between pupils and teachers as to give

the pupils a right to bring a class action for the teachers

not parties thereto (R. 17-29).

Appellees’ answer affirmed what everybody knows: the

assignment of teachers on the basis of race in the public

school systems of Florida is a concomitant of racially seg

regated public education (R. 67-68). The Superintendent’s

testimony makes clear that the policy has never been

otherwise:

“Q. You have never had any Negro teachers assigned

to white schools, or white teachers assigned to Negro

schools! A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. Does the Board have any policy statement on it!

A. I don’t know.

Q. But as far as you know it has always been that

way! A. So far as I know.” (R. 50-51.)

This Court in Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272

F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959 )̂ ”mreviewing evidence of a con

tinuing policy of racial segregation in another Florida pub

lic school system, expressly noted that continuation of the

policy was evidenced by the fact that, “At the time of

trial, in the Fall of 1958, complete actual segregation of

the races, both as to teachers and as to pupils, still pre

vailed in the public schools of the county.” Moreover, as

this Court ruled in the Gibson case, there can be no con

stitutional assignment of pupils to schools until some non-

segregated schools have been provided (at 767). If teachers

are assigned on the basis of race, then, obviously, the policy

of providing segregated schools has not been abandoned

and no non-segregated schools have been provided to which

valid assignment of pupils could be made. \

27

But quite aside from this Court’s prior decisions, the

Supreme Court’s decisions also make it abundantly clear

that the evil at which the Brown case strikes is racial dis

crimination in the entire public school system. Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7 (1958). From the very beginning,

the Supreme Court approached these cases in terms of the

whole system, as opposed to the right of individual Negro

pupils to be admitted to white schools maintained by the

states under the separate but equahjldcfrine. This was the

very reason for setting these cases down for reargument

in 1954, after the Court’s first pronouncement that racial

segregation in public education is unconstitutional. Upon

reargument, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349

U. 8. 249 (1955), the Court again made clear that what was

contemplated in these cases was a reorganization of the

school system on a nonracial basis. For this reason, the

Court’s opinion permitted district courts flexibility in the

enforcement of the constitutional principles involved, once

a start toward full compliance had been made in good faith.

“To that end,” said the Court, “the courts may consider

problems related to administration, arising from the physi

cal condition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personnel, revision of school districts and attend

ance areas into compact units to achieve a system of deter

mining admission to the public schools on a nonracial basis,

and revision of local laws and regulations which may be

necessary in solving the foregoing problems. They will also

consider the adequacy of any plans the defendants may

propose to meet these problems and to effectuate a transi

tion to a racially nondiscriminatory school system. During

this period of transition, the courts will retain jurisdiction

of these, cases” (at 300).

Clearly the district courts w’ere permitted to take these

matters into consideration because desegregation of the

28

school system is involved and not merely the opportunity

for individual Negroes to apply for admission to “white”

schools, as held by the court below. School personnel was

expressly included by the Supreme Court among those mat

ters which the district courts might take into consideration

in allowing time for full implementation. The Court plainly

envisioned that problems involving the reassignment of

school personnel would be an integral part of the desegre

gation process, just as it considered that a revision of

school zone lines into compact units, to achieve a non-

discriminatory pupil assignment policy, was involved.

Florida also realized that reassignment of school personnel

was involved in the desegregation process when it enacted

legislation dealing with the problem.4

Consequently, the right secured by the Supreme Court’s

decision in the Brown case is the right to attend school in

a nonraeial school system in which there is no discrimina

tion based upon race and color and not the right to attend

a “white” school in a racially segregated system.

School authorities cannot, therefore, be heard to say that

they have no duty to eliminate racial discrimination in the

school system and may continue to operate segregated

schools, assign teachers on the basis of race and, in short,

do business as usual.

Teachers are an integral part of the school system and

the mandate to end racial discrimination in the school sys

tem clearly carriers with it a duty to end the policy of

assigning teachers on the basis of race.

1 Race Relations Law Reporter 940 (1956).

29

III.

Use of the Florida Pupil Assignment Law as a method

of assigning pupils to school must be enjoined on this

record as a device for maintaining segregation.

The evidence in this case shows that after the FPAL was

adopted appellees resolved to use this law as the basis for

assigning pupils to school but from 1956 to the present,

appellees have used this law, not as a device for achieving

desegregation, but as a device for maintaining segregation.

In August 1956, using the FPAL and the State Super

intendent’s suggested implementing resolution, all previ

ously enrolled pupils were reassigned to the schools to

which they had been previously assigned on the basis of

race. Having once effected these racial assignments through

use of the FPAL, appellees continued this policy year after

year. This was a prohibited reassignment on the basis of

race. Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960); see,

Manning v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370, 374

(5th Cir. 1960).

As early as 1956, new pupils entering the first grade or

coming into the county for the first time were assigned in

accordance with all of the criteria of the pupil assignment

law. Again, complete segregation was the end result.

The Superintendent testified that tests were employed

only in the case of those students seeking transfer (R. 40-

41). Another constitutionally vulnerable action. Manning

v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960).

However, the proof shows that, again, the administration of

tests to transferees was generally limited to those appli

cants seeking a desegregated education. Pupils seeking

transfers within their racial group were reassigned, pend

ing administration of such tests, on the basis of their

application alone (R. 49).

30

Except for the Augustus child and the Robinson child,

no other Negro ever applied for admission to a white

school and, of course, no white child has ever applied for

admission to a Negro school. In the case of the Augustus

child, seeking admission to a school for the first time, the

use of the pupil assignment law resulted in a racial assign

ment. In the case of the Robinson child, a Negro seeking

to transfer to a white school, appellees used the FPAL to

block this attempt by shifting the burden of employing the

law’s criteria to the applicant.

In 1949, the FPAL was amended to more nearly conform

to the Alabama Pupil Assignment Law which had just been

upheld against an attack on its face. Shuttlesworth v.

Board of Education, City of Birmingham, 162 F. Supp. 372

(M. D. Ala. 1958) aff’d 358 U. S. 101. Florida apparently

believed that the state’s enactment of a pupil assignment

law and the adoption of implementing resolutions by each

county board was all that the Brown decision required.

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th

Cir. 1959); Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F.

2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958). Appellees, moreover, in using the

assignment law failed to heed the District Court’s warning

in the Shuttlesworth case, reiterated by the Supreme Court,

that the attack in that case was limited to the law on its

face, whereas, in some subsequent proceeding it might be

shown that the law had been improperly applied to main

tain segregation.

It is too plain to require argument that appellees cannot

use the FPAL or any other law to maintain segregation.

Shuttlesworth v. Board of Public Instruction, supra; Davis

v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala., 1949) aff’d 336 U. S.

933; Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939) ; Guinn v. United

States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915); Yiclc Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S.

356 (1896). The record here is clear. No matter how

31

appellees have employed the FPAL the result has been

complete segregation throughout the entire county school

system. This result having come about as a result of the

use of the pupil assignment law, its continued utilization as

a method of assigning pupils to school should have been

enjoined by the court below.

IV.

Appellants are entitled to an order requiring appel

lees to submit a desegregation plan as prayed in appel

lants’ complaint.

The District Court’s duty in this case was to require

defendants to make a prompt and reasonable start toward

full compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision in the

Brown case in September 1961. Brown v. Board of Edu

cation of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955); Boson v. Rippy,

275 F. 2d 850, 853 (5th Cir. 1960). Having failed to do so,

appellants are now entitled to an order requiring such a

start in September 1962. Boson v. Rippy, supra,

Appellants were also entitled to the desegregation plan

prayed for in their complaint. Boson v. Rippy, supra.

Under the facts in this case, the District Court should

have directed appellees to redraw the school attendance

area lines for all schools in accordance with normal school

capacity considerations, omitting all racial considerations.

The plan should also have included arrangements for the

reassignment of the staff on a nonracial basis in order to

provide some nonracial schools to which assignment could

be validly made.

Since the pupil assignment law has been used to per

petuate segregation rather than to effect desegregation,

and since the evidence shows that appellees considered it

32

unworkable in any event, and since the proof established

that pupils are, in fact, assigned to school pursuant to

attendance area lines (the simplest and most workable

pupil assignment plan), the court below erred in not grant

ing the relief sought.

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, the judgment below

should be reversed and the District Court ordered to

direct a prompt and reasonable start toward desegrega

tion in September 1962 and to direct appellees to come

forward with a plan as prayed.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles F. W ilson-

507 West Gadsden Street

Pensacola, Florida

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants