Burditt v Sullivan Brief as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 9, 1991

51 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burditt v Sullivan Brief as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent, 1991. 675d0713-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/63573118-9231-46a7-970f-d3bd3efb2cda/burditt-v-sullivan-brief-as-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

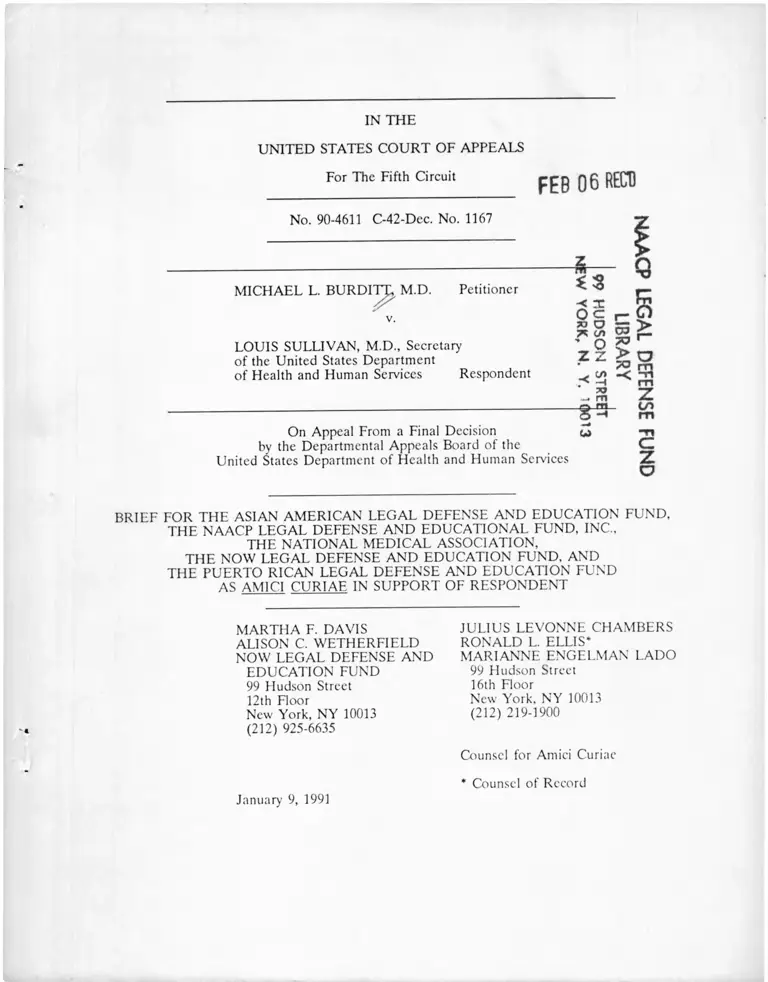

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fifth Circuit g g

No. 90-4611 C-42-Dec. No. 1167

MICHAEL L. BURDITj; M.D. Petitioner

LOUIS SULLIVAN, M.D., Secretary

of the United States Department

of Health and Human Services Respondent

< 7C

O c

73 O 7S </>

' O z z

c/>

30rnm

On Appeal From a Final Decision

by the Departmental Appeals Board of the

United States Department of Health and Human Services

03 ^

TO ^

> oTO ^

Zon

BRIEF FOR THE ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND.

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION,

THE NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, AND

THE PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

MARTHA F. DAVIS

ALISON C. WETHERFIELD

NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND

99 Hudson Street

12th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 925-6635

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

RONALD L. ELLIS*

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York. NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Amici Curiae

January 9, 1991

Counsel of Record

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 90-4611 C-42-Dec. No. 1167

MICHAEL L. BURDITT, M.D., Petitioner

LOUIS SULLIVAN, M.D., SECRETARY OF THE UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, Respondent

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned, counsel for Amici Curiae, certify that the following listed persons have

an interest in the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that the Judges

of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

I. Petitioner

Michael L. Burditt, M.D.

II. Respondent

Louis M. Sullivan, M.D.

Secretary of the

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

AND HUMAN SERVICES

III. Attorneys for Petitioner

William DeWitt Alsup

ALSUP & ALSUP

Edward J. Ganem

GANEM & VASQUEZ

Donald P. Wilcox

Hugh M. Barton

TEXAS MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

IV.Attornevs for Respondent

Leslie Shaw

John Meyer

Michael J. Astrue

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH AND HUMAN

SERVICES

V. Amici Curiae for Petitioner

Catherine I. Hanson

Kimberly S. Davenport

THE CALIFORNIA MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

Carter G. Phillips

Mark E. Haddad

SIDLEY & AUSTIN

Charles W. Bailey

Michael A. Pearle

THE TEXAS HOSPITAL

ASSOCIATION

Kirk B. Johnson

Edward E. Haddad

AMERICAN MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VI. Amici Curiae for Respondent

Julius L. Chambers

Ronald L. Ellis

Marianne Engelman Lado

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, IN

ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND

NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND

Martha F. Davis

Alison C. Wetherfield

NOW LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATION FUND

It is our understanding that the following organizations and individuals will also file briefs of amici

curiae in support of Respondent:

LAMDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND

PUBLIC CITIZEN, INC.

AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND

PHYSICIANS FOR REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

MACON REGIONAL CLIENTS COUNCIL

TENNESSEE HEALTH CARE CAMPAIGN

PARKLAND HOSPITAL

DORIS SPENCER

LINDY GOOCH

REBECCA OWENS

LACRETA MERGUSON

DELLA SIMMONS

PENNSYLVANIA CONSUMER

SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE

MEDICAL ASSISTANCE

ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Ronald L. Ellis

Counsel of Record for

Amici Curiae

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................... ii

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE .......................................................................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................................................................................................. 3

ARGUM ENT.............................................................................................................................. 4

I. ON ITS FACE, SECTION 1867 DOES NOT REQUIRE PROOF OF AN

ECONOMIC OR DISCRIMINATORY MOTIVE FOR DUMPING TO

ESTABLISH A VIOLATION........................................................................................ 4

A. The Plain Words Of The Statute Prohibit Denials Of Emergency Care And

Inappropriate Transfers, Without Regard To The Motivation Of The

Responsible Physician ........................................................................................ 4

1. The Balance Of Authority Weighs Against Requiring Proof Of

Economic Motivation ............................................................................ 5

2. The Text Of Section 1867, Including The Terms "Appropriate" And

"Stabilize," Does Not Support A Requirement That Claimants Prove

Economic Motivation ............................................................................ 7

B. Congress Was Aware Of Analogous Federal And State Laws That Explicitly

Require ProoEOfTmproper Intent And Deliberately Chose Not To Enact

Such A Requirement In Section 1867 .............................................................. 9

II. IMPOSITION OF A REQUIREMENT THAT THE GOVERNMENT PROVE

THE MOTIVATION OF THE PROVIDER WOULD SUBSTANTIALLY

WEAKEN SECTION 1867, CONTRAVENING CONGRESS’ INTENT TO

PROVIDE AN EFFECTIVE MEANS OF ENFORCEMENT ................................. 12

A. The Burden Of Proving The Motivation Of The Provider Would Be

Prohibitively High And Would Undermine Effective Enforcement Of The

S tatute.................................................................................................................. 13

B. The Added Burden Of Proof Would Endanger The Lives Of Those In Need

Of Emergency C a re ............................................................................................ 14

CONCLUSION........................................................................................................................... 18

APPENDIX A ......................................................................................................................... A-l

APPENDIX B ......................................................................................................................... B-l

APPENDIX C ......................................................................................................................... C-l

i

TABLE OF CASES

CASES

Bryan v. Koch.

627 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980) ............................................................................................ 1

Cleland v. Bronson Health Care Group,

917 F.2d 266 (6th Cir. 1990) .......................................................................................... 5, 6, 8

Deberry v. Sherman Hospital Association

741 F.Supp. 1302 (N.D. 111. 1990) ................................................................................. 5, 6, 13

Evitt v. University Heights Hospital,

727 F. Supp. 495 (S.D. Ind. 1989) ................................................................................ 6

H.J. Inc, v. Northwestern Bell Telephone Co..

492 U .S.__ , 109 S. Ct. 2893 (1989) ............................................................................ 5

Hope v. Perales.

No. 21073/90, (S.Ct. N.Y. Co. filed Sept. 21, 1990) .................................................... 2

INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca.

480 U.S. 421 (1986) ...................................................................................................... 6

In re James Archer Smith Hospital,

(Homestead, Fla.; HHS/OCR No. 04813063, decided April 30, 1984) ........................ 10

In re Margaret R. Pardee Memorial Hospital,

(Hendersonville, N.C.; HHS/OCR No. 04803173, decided Sept. 4, 1981) ................. 2, 10

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp.,

558 F.2d 1283 (7th Cir. 1977), cert, denied. 434 U.S. 1025 (1978) ............................. 13, 14

Nichols v. Estabrook,

741 F. Supp. 325 (D.N.H. 1989) ................................................................................... 6

People v. Flushing Hospital,

122 Misc. 2d 260, 471 N.Y.S.2d 745 (Queens Co. Crim. Ct. 1983) ............................. 12

Reid v. Indianapolis Osteopathic Medical Hospital,

709 F. Supp. 853 (S.D.Ind. 1989) ................................................................................. 13

Rust v. Sullivan,

889 F.2d 401 (2d Cir. 1989), cert, granted, 110 S. Ct. 2324

(No. 89-1391, 89-1392) ................................................................................................. 2

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital,

323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert. denied, 376 U.S. 938 (1964) ............................... 1

Stewart v. Mvrick,

731 F. Supp. 433 (D. Kan. 1990) ................................................................................... 6

In re Wadlev Hospital II,

(Texarkana, Texas; HHS/OCR No. 06813057) .............................................................. 10

11

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1986 (COBRA),

Pub. L. No. 99-272 , § 9121(b), 100 Stat. 164-67 (1986) ........................................... 3

Hill-Burton Act,

42 U.S.C. §§ 291, etseSi ............................................................................................... 9

Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1989,

Cong. Rep., H.R. 3299 ................................................................................................. 9

Section 1867 of the Social Security Act,

42 U.S.C. § 1395dd ........................................................................................................ passim

Cal. Health and Safety Code §§ 1317, 17409, 1978 ......................................................... 9

Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 26-15-101-110 ..................................................................................... 9

Fla. Stat. Ann. §§ 395.0143, 401.45(1) ............................................................................ 9, 11

Ga. Code Ann. §§ 31-8-42, 31-8-43, 31-8-46 .................................................................. 9, 10

Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 321-232(b) ........................................................................................ 9, 11

111. Ann. Stat. eh. I l l 1/2, § 86 ........................................................................................ 9

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 216B.400(1), 216B.990(3) ........................................................... 9

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 2113.4(2)-2113.4(b) ....................................................................... 9

Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. § 70E(m)(e) ................................................................................. 9

Mich. Stat. Ann. §§ 14.15(20715), 14.15(20704(4), 14.15(20703) .................................... 9

Mo. Ann. Stat. § 205.989(1) ............................................................................................... 9

N.J. Admin. Code tit. 8, § 8.43-B1 ................................................................................... 10

N.Y. Public Health Law §§ 2805-b, 2806(1) ..................................................................... 10, 12

Oregon Admin. Reg. ch. 333, § 23(15) ............................................................................ 10

Pa. Admin. Reg. § 117.1(a), (b) ........................................................................................ 10

R. I. Gen. Laws § 23-17-26(a) ......................................................................................... 10

S. C. Admin. Reg. 61-16 § 309 .......................................................................................... 10

Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 68-69-301, 68-39-302, 68-39-511(12) ............................................. 10

Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. § 4438 .......................................................................... 10, 11

Utah Code Ann. §§ 26-8-8(1), 26-8-2(12) .......................................................................... 10

i i i

Wis. Stat. Ann. § 146.301 ................................................................................................... 10

Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 35-2-115(a) .......................................................................................... 10

42 C.F.R. § 124.603(b)(1), (2) .......................................................................................... 10, 11

r

MISCELLANEOUS

Ansell, Schiff, Patient Dumping: Status, Implications, and

Policy Recommendations. 257 J. Amer. Med. Assn. 150 (1987) ................................. 17

Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce,

Statistical Abstract of the United States 1989 ........................................................... 14, 16

Cypen, Access to Health Care Services for the Poor:

Existing Programs and Limitations.

31 Univ. of Miami L. Rev. 127 (1976) ......................................................................... 11

Equal Access to Health Care: Patient Dumping: Hearing

Before the Human Resources & Intergovernmental Relations

Subcomm. of the House Comm, on Government Operations,

100th Cong., 1st Sess. 40 (1987) ................................................................................... 5

Friedman, Problems Plaguing Public Hospitals: Uninsured

Patient Transfers. Tight Funds, Mismanagement, and

Misperception, 257 J. Amer. Med. Assn. 1850 (1987) ................................................ 16

H.R. Rep. No. 99-241, Part-V 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (1985) ........................................ 5, 12

H.R. Rep. No. 99-241, Part 3, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 27 (1985) ...................................... 5, 7, 12

Himmelstein, Woodhandler, Harnly, et al.,

Patient Transfers: Medical Practice as Social Triage,

74 Am. J. Public Health 494 (1984) .............................................................................. 15

House Committee on Governmental Operations,

Equal Access to Health Care: Patient Dumping,

H.R. Rep. 531, 100th Cong., 2d Sess., 14 (1988) ........................................... 13, 14, 16

National Health Law Program, Patient Dumping:

A Crisis in Medical Care for the Indigent,

19 Clearinghouse Rev. 1413 (1986) ............................................................................ 11

National Health Law Program, Putting Flesh on the Bones of

the Hill-Burton Community Service Regulations.

19 Clearinghouse Rev. 13 (May 1985) .......................................................................... 10

National Health Law Program, Summary of State Emergency

Care Statutes and Case Law. 18 Clearinghouse Rev. 494 (1985) ............................... 11

Note, Preventing Patient Dumping: Sharpening the COBRA’s

Fangs. 61 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1186 (1986) .......................................................................... 10

S. Rep. No. 1285, 93rd Cong., 2d Sess. 61 ....................................................................... 10

IV

Schiff, Ansell, Schlosser, Idris, Morrison, Whitman,

Transfers to a Public Hospital.

314 New Eng. J. Med. 552 (1986) ................................................................................ 14

Sutherland, Statutory Construction §§ 47.16, 49.12 ......................................................... 7, 9

73 Am. Jur. 2d Statutes § 151 (1974) ................................................................................ 6

v

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE

The ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATION FUND (AALDEF),

founded in 1974, is a national civil rights organization that addresses critical issues facing Asian

Americans through community education, advocacy, and litigation. AALDEF’s program priorities

include the elimination of anti-Asian violence, immigrants’ rights, voting rights, employment and

labor rights, and redress for Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in camps within the

United States during World War II. AALDEF is concerned with the policy and practice of

hospitals that deny treatment to patients in need of emergency care by transferring them to other

hospitals in disregard of the health risks to the patients and their statutory obligations. This

patient "dumping" directly impacts upon the indigent, many of whom are recent immigrants and

their families. For these reasons, AALDEF urges this Court to enforce the plain meaning of this

statute requiring hospital emergency rooms to accept and treat any individual seeking emergency

medical care.

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. (LDF) is a national

non-profit corporation formed to assist African Americans in the vindication of their constitutional

and civil rights. For many years LDF has pursued litigation to secure the basic civil and economic

rights of low-income black families and individuals. Litigation to ensure the non-discriminatory

delivery of health care and hospital services to African Americans has been a long-standing LDF

priority. See, e.g., Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hosp., 323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert.

denied. 376 U.S. 938 (1964) (prohibiting racial segregation in publicly supported health care

facilities); Bryan v. Koch, 627 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980) (challenge to the closure of a public hospital

in Harlem under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). Intentional and unintentional practices

that discriminate against African Americans have been a primary LDF concern.

Through its Poverty & Justice Program, LDF is challenging barriers to economic

advancement to help improve the economic status and living conditions of the many in poverty.

LDF has also worked on behalf of African Americans struggling with the burdens of poor health

1

and discriminatory and inadequate health care services. This case implicates the full panoply of

these important LDF concerns and, for this reason, LDF has filed this brief amicus curiae in

support of respondent.

The NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION (NMA), founded in 1895, represents 16,000

African-American physicians in the United States, including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

The NMA seeks to foster the enactment of just medical laws and to educate the public concerning

all matters affecting public health, especially matters affecting the socio-economically

disadvantaged and the health care of women.

The NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND (NOW LDEF), founded in

1970 by leaders of the National Organization for Women, is a nonprofit civil rights organization

that performs a broad range of legal and educational services nationally in support of women’s

efforts to secure equal rights. One of NOW LDEF’s priorities is the protection of the health of

all women, particularly low-income women and women of color, and NOW LDEF has participated

in numerous cases designed to effectuate that goal. See, e.g., Hope v. Perales, No. 21073/90, (S.Ct.

N.Y. Co. filed Sept. 21, 1990) (challenging Medicaid restrictions on abortion funding under state

constitution); Rust v. Sullivan, 889 F.2d 401 (2d Cir. 1989), cert, granted, 110 S.Ct. 2324 (No. 89-

1391, 89-1392) (challenging restrictions on federal funding of family planning clinics). The instant

case directly implicates the access of poor pregnant women to adequate health care, as well as the

access to health care and appropriate treatment of poor, uninsured women with other emergency

conditions. For these reasons, NOW LDEF has filed this brief amicus curiae in support of

respondent.

The PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND is a national

organization founded in 1972 to protect civil rights and to ensure equal protection of the laws for

Puerto Ricans and other Latinos. The Fund has participated in lawsuits and has served as an

advocate to ensure that Latinos have access to full and adequate health care. The Fund

2

recognizes that restrictions or limitations on the provision of health services deny Latinos the

access necessary to fully exercise their rights, and place Latinos at an even greater risk of

inadequate treatment.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Section 1867 of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-

272 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1395dd) (hereinafter "Section 1867") requires hospitals

receiving Medicaid funds to provide a medical screening and, where appropriate, to provide

emergency care and stabilization to "any individual" or woman in active labor who requests such

services. A hospital or responsible physician who knowingly or negligently fails to comply with the

requirements of Section 1867 is liable for civil monetary penalties.

One of Congress’ primary aims in enacting Section 1867 was to deter hospitals and doctors

from refusing to provide care to the poor and the uninsured. In drafting the statute, however,

Congress expanded upon the scope of prior federal and state statutes and enhanced Section 1867’s

deterrent effect by prohibiting all refusals of emergency care and all inappropriate transfers that

are not medically supported. Section 1867 does not require proof that the refusal of care was

economically motivated.

Requiring proof of economic motivation would both contravene the plain words of the

statute and undermine Congress’ purpose in enacting Section 1867. Congress responded to dire

reports of patients who were inappropriately turned away from emergency rooms - i.e. examples

of "dumping," practices that have particularly harsh consequences for African-Americans, Latinos

and pregnant women - by stripping claimants’ burden of proof to the essential element: denial

of emergency care. Imposing a higher standard of proof would frustrate enforcement efforts by

the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), thwart Congress’ purpose in enacting Section

1867 and, inevitably, lead to another litany of tragic stories, as doctors and hospitals continue to

deny services to individuals in need of emergency health care.

3

ARGUMENT

I. ON ITS FACE, SECTION 1867 DOES NOT REQUIRE PROOF OF AN

ECONOMIC OR DISCRIMINATORY MOTIVE FOR DUMPING TO

ESTABLISH A VIOLATION

A. The Plain Words Of The Statute Prohibit Denials Of Emergency Care And

Inappropriate Transfers, Without Regard To The Motivation Of The Responsible

Physician

Amici in support of Petitioner contend that, in order to prove a violation of Section 1867,1

HHS must prove that Dr. Burditt transferred Ms. Rivera because she was uninsured. They

contend that because Congress enacted Section 1867 to address the pervasive problem of

"dumping" of indigent patients by hospitals and doctors, this Court should interpret Section 1867

to sanction denials of emergency care and inappropriate transfers only when a claimant can prove

that a denial was motivated by the indigence of a patient.

As set out in the Secretary’s brief, this position flies in the face of the plain meaning

of the statute and its legislative history. Appellee Br. at 37-48. There is no ambiguity in the

words of Section 1867: the plain words of the statute do not require proof of economic motive to

1 Section 1867 provides, in pertinent part, that

[i]f any individual (whether or not eligible for benefits under this

subchapter) comes to the emergency department and a request is

made on the individual’s behalf for examination or treatment for a

medical condition, the hospital must provide for an appropriate

medical screening examination within the capability of the hospital’s

emergency department to determine whether or not an emergency

medical condition ... exists or to determine if the individual is within

active labor.

Section 1867 (a). In addition, if "any individual" is determined to have an emergency condition

or to be in active labor, the hospital must either provide further treatment to stabilize the medical

condition or an "appropriate transfer," as defined in Section 1867, which meets the "interest of the

health and safety of the patients transferred." Section 1867(b), (c). Willful or negligent failure

to comply with these requirements exposes the hospital and the responsible physician to civil

penalties. Section 1867(d).

4

establish a violation.2 * * See, e.g.. Deberry v. Sherman Hospital Ass’n. 741 F. Supp. 1302, 1305 (N.D.

111. 1990) ("plain language" of the statute does not require "dumping" to establish violation). See

also Cleland v. Bronson Health Care Group. 917 F.2d 266, 270 (6th Cir. 1990) (Section 1867

"plainly has no such limitation on its coverage"). In fact, the statute specifically negates any

speculation that proof of economic motive is necessary to establish a violation by indicating that

appropriate emergency services must be provided "whether or not" the patient is eligible for

Medicare benefits. Section 1867(a), (b)(1).

1. The Balance of Authority Weighs Against Requiring Proof of

Economic Motivation

The plain words of Section 1867 lend no support to a requirement of either indigence, for

standing, or economic motive, as an element of a statutory violation. See discussion supra. While

the impetus for Section 1867 came from the much publicized patient dumping cases in which

victims were poor or uninsured, Congress created a federal private right of action against hospitals

and did not limit it to the indigent: "any individual who suffers personal harm as a direct result

of a participating hospital’s violation" may recover damages against the hospital. 42 U.S.C. §

1395dd(d)(3)(A). In creating this private right of action for "any individual," Congress was fully

aware that many of the victims of inappropriate emergency treatment were neither indigent nor

uninsured. See Equal Access to Health Care: Patient Dumping: Hearing Before the Human

Resources & Intergovernmental Relations Subcomm. of the House Comm, on Government

Operations. 100th Cong., 1st Sess. 40 (1987) (statement of Judith Waxman, managing attorney, the

National Health Law Program, noting that while 37 million Americans have no health insurance

coverage, an additional 50 million have inadequate coverage) (hereinafter "Subcomm. Hearing").

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, the only appellate court that has ruled on

the question whether economic motivation is a requisite to a violation of Section 1867, agreed in

Cleland v. Bronson that, on its face, Section 1867 mandates appropriate screening for all

individuals who seek emergency treatment, and stabilization and treatment for ah such individuals

2 Earlier versions of the statute were similarly worded to apply to all individuals who request

emergency screening. See H.R. Rep. No. 241, 99th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 1, at 27 (1985), reprinted

in 1986 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 579, 605.

5

who are determined to have emergency medical conditions or to be in active labor, regardless of

indigence. 917 F.2d at 270. See also Deberrv. 741 F. Supp. at 1305.

The handful of federal district court opinions that have read a requirement of economic

motive into the statute are, as set out in Deberrv and Cleland. unpersuasive.3 Rather than analyze

the text of Section 1867, these cases, Stewart v. Mvrick. 731 F. Supp. 433 (D. Kan. 1990), Evitt v.

University Heights Hosp., 727 F. Supp. 495 (S.D. Ind. 1989), and Nichols v. Estabrook, 741 F.

Supp. 325 (D.N.H. 1989), ignore the statute’s plain language and, without authority, rush to a

restrictive interpretation of its legislative history. As noted in Deberrv. this approach is

inappropriate: "[I]t is not this court’s place to rewrite the language enacted by our duly elected

officials" through a "clandestine use of the legislative history."4 741 F. Supp. at 1307. See INS v.

Cardoza-Fonseca. 480 U.S. 421, 432 n.12 (1986) ("[Wjhere no ambiguity appears, it has been

presumed conclusively that the clear and explicit terms of a statute express the legislative

intention"); Cleland, 917 F.2d at 270 (1990); 73 Am. Jur. 2d Statutes § 151 (1974) ("the legislative

history of a statute may not compel a construction at variance with its plain words").5

3 This is an issue of first impression in the Fifth Circuit.

4 The United States Supreme Court most recently rejected such a blatant attempt to rewrite

a statute in HJ. Inc, v. Northwestern Bell Telephone Co., 492 U.S. __ , 109 S.Ct. 2893 (1989),

concerning the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO). The Court

acknowledged that organized crime was Congress’ "major target" in enacting RICO, yet it found

that the plain words of the statute do not require an organized crime nexus. The Court concluded

that while "[tjhe occasion for Congress’ action was the perceived need to combat organized crime

... Congress tor cogent reasons chose to enact a more general statute." Id. at 2903-04.

5 Moreover, although these three district courts dismissed Section 1867 claims where

plaintiffs did not allege that their financial condition or lack of health insurance contributed to

defendant’s conduct, it is not clear whether the courts were concerned with standing or the merits

of plaintiffs’ claims. See, e.g„ Stewart. 731 F. Supp. at 435 ("Indigent persons denied emergency

medical care possess a federal cause of action under the Act") (emphasis added); but see, e.g.,

Evitt. 727 F. Supp. at 498 (noting, without further explanation, that plaintiffs were "unable to

present evidence which could prove that [the patient] was turned away ... for economic reasons").

6

2. The Text Of Section 1867, Including The Terms "Appropriate" And

"Stabilize," Does Not Support A Requirement That Claimants Prove

Economic Motivation

Amici in support of Petitioner also argue that proof of economic motivation is required by

the use of the terms "appropriate" and "stabilize" in Section 1867. The text of the statute,

however, provides no basis whatsoever for this construction, and, instead, makes clear that each

of these terms should be assessed in accordance with medical criteria.

For example, Section 1867 requires that "the hospital must provide for an appropriate

medical screening examination ... to determine whether or not an emergency medical condition ...

exists or to determine if the individual is in active labor." Section 1867(a) (emphasis added). In

this context, the term "appropriate" clearly relates to the purpose of the examination - i.e. that

the examination must be appropriate to the determination of whether the patient has an

emergency medical condition.

The term "appropriate" also appears in several other places in the statute. For example,

Section 1867(c)(2)(B) requires that the transferring hospital provide the receiving facility with

"appropriate" medical records, and Section 1867(c)(2)(C) requires that "appropriate" life support

measures be used if a transfer is effected. Most tellingly, the statute provides a detailed definition

of "appropriate transfer," which makes no mention whatsoever of any anti-discrimination

component of the phrase. Section 1867(c)(2). Instead, the phrase is defined in terms of the

"interest[s] of the health and safety of patients transferred," focusing on the medical propriety of

the transfer rather than the requirement of an improper animus conjured up by Amici. As like

words should be interpreted alike within a single statute, see Sutherland, Statutory Construction

§ 47.16, the use of the term "appropriate" should not be construed to give rise to a requirement

that the Secretary or a private plaintiff show improper animus in order to prove a violation of

Section 1867.3 5

5 An earlier version of Section 1867 also adopted a medical definition of "appropriate," with

no mention of any requirement of improper animus. That provision, which was not ultimately

enacted, would have made a doctor criminally liable for failure to conduct an "appropriate" medical

screening examination if that failure constituted a gross deviation from the "prevailing local

standards of medical practice." H.R. Rep. 241, 99th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 3, at 8, reprinted m 1986

U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 726, 729.

7

The statute is equally clear with respect to the term "stabilize." "[T]o stabilize" is defined

in the statute as follows:

with respect to a medical condition, to provide such medical

treatment of the condition as may be necessary to assure that no

material deterioration of the condition is likely to result from the

transfer of the individual from a facility.

Section 1867(e)(4)(A). Similarly, "stabilized" means

with respect to a medical condition, that no material deterioration

of the condition is likely to result from the transfer of the individual

from a facility.

Section 1867(e)(4)(B). Thus, Section 1867 squarely indicates on its face that the "stability" of a

patient is to be assessed in accordance with medical standards, without an inquiry into the motives

of defendants.

Nevertheless, ignoring the text of the statute, Amici cite the Cleland opinion in support of

their claim that proof that a defendant failed to conduct an "appropriate" examination or failed

to "stabilize" a patient requires evidence that the defendant was motivated by, among other things,

prejudice against the race, sex or ethnic group of the patient;

distaste for the patient’s condition (e.g., AIDS patients); personal

dislike or antagonism between medical personnel and the patient;

disapproval of the patient’s occupation; or political or cultural

disapproval.

Cleland, 917 F.2d at 272.

While the Cleland court concluded, on the one hand, that a patient’s economic status is

irrelevant to an assertion of rights under Section 1867, the court also suggested, erroneously, that

the terms "appropriate" and "stabilize" create the need to prove improper motive. Id. at 270-74.

The court’s back-door effort to read a motive requirement into the statute is misguided: in

interpreting these terms, the court blatantly ignored the primary tools of statutory construction -

- the text of Section 1867 and its legislative history. There is no Committee Report or speech on

the Senate floor or any other legislative source for the groundless assertion that "appropriate" or

"stabilize" mean "nondiscriminatory." In fact, during the 1987 hearings on implementation of the

statute, several witnesses and legislators specifically contrasted Section 1867’s broad protection, of

"all beneficiaries of hospital services," with prior federal laws that protected only victims of

8

discrimination or individuals who were able to prove that their dumping was motivated by

economic factors. Subcomm. Hearing at 2 (statement of Richard Kusserow, HHS Inspector

General).7

Thus, a fair reading of the Cleland court’s opinion demonstrates that it pulled out of thin

air a new, onerous requirement -- a requirement that Congress had never debated, discussed, or

delineated, and had not included in the text of the statute. The construction of the terms

"appropriate" and "stabilize" urged by Amici for Petitioners was simply not Congress’ intent and,

with no ambiguity in the statute itself and no support in the legislative history, should not be

adopted after-the-fact.

In sum, the argument that a Section 1867 violation requires proof that defendants who

have examined potential emergency patients or effected inappropriate transfers were motivated by

indigence or other improper animus is not supported by the plain words of the statute nor by its

legislative history. Moreover, as discussed more fully below, it is clear that Congress could have

written a statute requiring proof of motivation — dozens of other statutes enacted by Congress

explicitly require such proof — and it deliberately chose not to.

B. Congress Was Aware Of Analogous Federal And State Laws That Explicitly

Require Proof Of Improper Intent And Deliberately Chose Not To Enact Such A

Requirement In Section 1867

Prior to the enactment of Section 1867, hospital emergency services were regulated both

by the Hill-Burton Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 291, et seq., and by state laws.8 Congress was aware of both

7 Following these hearings, Congress amended Section 1867 without modifying its application

to all patients, regardless of indigence, see Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1989, Cong. Rep., H.R.

3299, at 834-39, a fact that strongly suggests that Congress intended to enact such a broad

protection for emergency patients. See Sutherland, Statutory Construction § 49.10 ("[w]here . . .

contemporaneous interpretation has been called to the legislature’s attention, there is [] reason to

regard the failure of the legislature to change the interpretation as presumptive evidence of its

correctness").

8 At the time that Congress enacted Section 1867, twenty-two states had statutes or regulations

governing the provision of emergency services. See Cal. Health and Safety Code §§ 1317, 17409,

1978; Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 26-15-101-110; Fla. Stat. Ann. §§ 395.0143, 401.45(1); Ga. Code Ann.

§§ 31-8-42, 31-8-43, 31-8-46; Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 321-232(b); 111. Ann. Stat. ch. I l l 1/2, § 86; Ky.

Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 216B.400(1), 216B.990(3); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 2113.4(2)-2113.4(b); Mass.

Gen. Laws Ann. § 70E(m)(e); Mich. Stat. Ann. §§ 14.15(20715), 14.15(20704(4)), 14.15(20703); Mo.

9

of these sources of law as it drafted and later amended Section 1867. See, e.g., Subcomm. Hearing

at 2 (Statement of Representative Weiss, noting that Hill-Burton Act requires that hospitals

receiving funds "must provide emergency care to certain individuals regardless of ability to pay");

Note, Preventing Patient Dumping: Sharpening the COBRA’s Fangs, 61 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1186, 1202

n.112 (1986) (Congress referred to Texas statute in drafting Section 1867). In fact, Congress

enacted Section 1867, in part, because the Hill-Burton Act had proven to be ineffective in

deterring patient dumping. See S. Rep. No. 1285, 93rd Cong., 2d Sess. 61, reprinted in 1974 U.S.

Code Cong. & Admin. News 7842, 7900 (implementation of Hill-Burton by HEW and state

agencies has been a "sorry performance").

Enacted in 1946, the Hill-Burton Act imposes certain community service requirements on

all hospitals receiving Hill-Burton funds. The regulations implementing the Hill-Burton Act

specifically provide that "[a] facility may not deny emergency services to any person who resides

... in the facility's service area on the ground that the person is unable to pay for those services."

42 C.F.R. § 124.603(b)(1).8 See generally National Health Law Program, Putting Flesh on the

Bones of the Hill-Burton Community Service Regulations, 19 Clearinghouse Rev. 13 (1985). The

HHS Office of Civil Rights has construed these regulations to require, as a prerequisite to

establishing a violation, proof that the hospital’s decision to deny emergency services was motivated

by the patient’s inability to pay or by some other improper factor. See, e.g.. In re Margaret R.

Pardee Memorial Hospital, (Hendersonville, N.C.; HHS/OCR No. 04803173, decided Sept. 4,1981)

(no evidence supported the complainant’s allegations that emergency services had been denied

because he was unable to pay) (annexed as Appendix A hereto); In re Wadley Hospital II,

(Texarkana, Texas; HHS/OCR No. 06813057) (no evidence that Medicaid was the reason why

Ann. Stat. § 205.989(1); N.J. Admin. Code tit. 8, § 8.43-B1; N.Y. Public Health Law §§ 2805-b,

2806(1); Oregon Admin. Reg. ch. 333, § 23(15); Pa. Admin. Reg. § 117.1(a), (b); R.I. Gen. Laws

§ 23-17-26(a); S.C. Admin. Reg. 61-16 § 309; Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 68-69-301, 68-39-302, 68-39-

511(12); Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. § 4438; Utah Code Ann. §§ 26-8-8(1), 26-8-2(12); Wis.

Stat. Ann § 146.301; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 35-2-115(a).

8 In contrast to the provision concerning denial of emergency services, there is no explicit

provision in the Hill-Burton regulations that suggests that inappropriate transfers are those

motivated by economic status. 42 C.F.R. § 124.603(b)(2).

10

reason why emergency services had been denied) (annexed as Appendix B hereto).9 Not

surprisingly, given Congress’ dissatisfaction with Hill-Burton, in enacting Section 1867, Congress

deliberately chose not to adopt the restrictive language of the Hill-Burton regulation and, instead,

enacted a statute that does not require proof of the defendant’s motive for denying emergency

services.

Congress was also aware of laws in twenty-two states that regulate the provision of

emergency care when it enacted Section 1867. H.R. Rep. 241, 99th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 3, at 5,

reprinted in 1986 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 726, 726-27 (noting ineffectiveness of state

laws and need for additional federal sanctions). See generally National Health Law Program,

Patient Dumping: A Crisis in Medical Care for the Indigent, 19 Clearinghouse Rev. 1413, 1415

(1986); National Health Law Program, Summary of State Emergency Care Statutes and Case Law,

18 Clearinghouse Rev. 494 (1985). These statutes vary widely. Some state laws explicitly provide

that a defendant violates the law only if he or she was motivated to deny proper care by the

patient's indigence; other state laws explicitly prohibit denial of emergency care based upon a

variety of improper factors, including indigence; still other state laws, like Section 1867, contain

no such limitations and instead require that emergency services be provided to all who need

emergency care. See, e.g., Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 321-232(b) (emergency medical services shall not

be denied "on the basis of the ability of the person to pay therefore or because of lack of prepaid

health care coverage or proof of such ability to pay for coverage"); Tex. Health & Safety Code

Ann. § 4438a (emergency services shall not be denied "because the person is unable to establish

his ability to pay for the services or because of race, religion, or national ancestry"); Fla. Stat. Ann.

§§ 395.0143, 401.45(1) (no hospital shall deny treatment "for any emergency medical condition

which will deteriorate from failure to provide such treatment"); Cypen, Access to Health Care

Services for the Poor: Existing Programs and Limitations, 31 Univ. of Miami L. Rev. 127, 150-

9 In fact, despite the explicit reference in the Hill-Burton Act to ability to pay, it is not clear

that proof of economic motive is required in order to sustain a violation of the Act. See e.g.. In

re James Archer Smith Hospital, (Homestead, Fla.; HHS/OCR No. 04813063, decided April 30,

1984), at 3 (annexed as Appendix C hereto). Amici for Petitioners’ argument that Section 1867,

which has no such statutory language, nevertheless requires proof of economic motive, is

preposterous.

11

51 (1976) (Florida deliberately adopted broad statute mandating emergency care for all patients);

Ga. Code Ann. §§ 31-8-42 (hospitals with emergency services must provide care to any pregnant

women in active labor); N.Y. Pub. Health L. § 2805-b ("hospital shall admit any person who is

in need of immediate hospitalization with all convenient speed"); People v. Rushing Hosp.. 122

Misc. 2d 260, 471 N.Y.S.2d. 745 (Queens Co. Crim. Ct. 1983) (statute creates "strict liability" for

refusal to provide emergency treatment).

Presented with these various models for Section 1867, Congress quite clearly chose to

strengthen federal anti-dumping laws by declining to adopt the requirement that plaintiffs prove

that indigence or some other improper animus motivated defendants’ denial of care. This choice

comports with Congress’ expressed concern that "[ajlthough at least 22 states have enacted statutes

or issued regulations requiring the provision of limited medical services whenever an emergency

medical situation exists ... the problem needs to be addressed by federal sanctions." H.R. Rep.

241, 99th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 3, at 5, reprinted in 1986 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 726, 726-

27. This express legislative concern, along with the plain text of the statute and Congress’

recognition that the Hill-Burton and state law models had failed, mandates that Section 1867 be

interpreted to apply to al] patients who are denied emergency care, not only those who can prove

a discriminatory or economic motivation for the denial.

II. IMPOSITION OF A REQUIREMENT THAT THE GOVERNMENT PROVE

THE MOTIVATION OF THE PROVIDER WOULD SUBSTANTIALLY

WEAKEN SECTION 1867, CONTRAVENING CONGRESS’ INTENT TO

PROVIDE AN EFFECTIVE MEANS OF ENFORCEMENT

The concern underlying the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1985 was

elucidated in the House Ways and Means Committee Report on the bill:

The Committee is most concerned that medically unstable patients

are not being treated appropriately. There have been reports of

situations where treatment was simply not provided. In numerous

other instances, patients in an unstable condition have been

transferred improperly, sometimes without the consent of the

receiving hospital.

H.R. Rep. No. 241, 99th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 1, at 27 (1985), reprinted in 1986 U.S. Code Cong.

& Admin. News 579, 605.

12

violation of the statute, the government must show that (1) the patient went to the health care

provider's emergency room (2) with an emergency medical condition, and that (3) the provider did

not adequately screen him to determine whether he had such a condition, or (4) discharged or

transferred him before the emergency condition had been stabilized. See Deberry. 741 F. Supp.

at 1305. The statute, thus, established criteria for the treatment of all emergency room patients -

- and, if hospitals and emergency room physicians do not act in accordance with the criteria, they

stand in violation of Section 1867. See Reid v. Indianapolis Osteopathic Medical Hosp., 709 F.

Supp. 853, 854-55 (S.D.Ind. 1989) (Section 1867 establishes a federal standard of care based on

strict liability).

In 1989, Congress reaffirmed its commitment to providing an effective method to address

the inappropriate treatment of individuals in need of emergency care with the passage of the

Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1989, amending Section 1867. The amendments were Congress’

response to the critical need to let it be known that the transfer of medically unstable patients can

only be carried out if it is in the best interest of the patient. House Committee on Governmental

Operations, Equal Access to Health Care: Patient Dumping. H.R. Rep. 531, 100th Cong., 2d

Sess., 14 (1988) (hereinafter "Equal Access Rep.").

A. The Burden Of Proving The Motivation Of The Provider Would Be Prohibitively

High And Would Undermine Effective Enforcement Of The Statute

If imposed, the burden of proving discriminatory intent would deter aggrieved individuals

from bringing their claims to court and would reduce the likelihood of success for any who might

proceed. "[A] requirement that the plaintiff prove discriminatory intent ... is often a burden that

is impossible to satisfy. ’[Ijntent, motive, and purpose are elusive subjective concepts.’"

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 558 F.2d 1283, 1290 (7th Cir. 1977) (quoting Hawkins

v. Town of Shaw. 461 F.2d 1171, 1172 (5th Cir. 1972) (en banc) (per curiam)), cert, denied. 434

U.S. 1025 (1978). Imposition of this onerous evidentiary burden in Section 1867 cases would

thwart the purpose of the statute -- i.e., the congressional aim of ensuring access to emergency

care for those in need of emergency services and for women in labor.

13

care for those in need of emergency services and for women in labor.

Amici in support of Petitioner suggest that rather than producing evidence to determine

whether an individual in fact had an emergency medical condition, received an appropriate medical

screening, was stabilized, and/or was appropriately transferred, the government and private

plaintiffs should be forced to engage in the onerous and subjective process of determining, and

then proving in court, that health care providers intended to deny or to inappropriately serve

individuals because of their economic status. Of necessity, the focus of administrative efforts to

enforce Section 1867 would then be on the state of mind of providers, rather than upon the

identification of inappropriate practices and corrective measures. The practice of patient dumping

would continue to go unpunished. See Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 558 F.2d at

1290 (a strict focus on intent permits discrimination to go unpunished in the absence of overt

bigotry, evidence of which is difficult to find).

A requirement that the government prove Dr. Burditt’s intent to discriminate would be

burdensome, would impede enforcement efforts, contravening Congressional intent, and should not

be adopted.

B. The Added Burden Of Proof Would Endanger The Lives Of Those In Need Of

Emergency Care

The imposition of an intent requirement would not only undermine the strength of the

statute but would endanger the lives of those in need of emergency care. By encumbering

patients, be they poor or working class, with an additional burden of proof, this requirement would

dilute the deterrent effect of the statute, as hospitals and doctors become secure in the knowledge

that their motivation will be difficult for patients to prove.

As the House Committee on Government Operations recognized, "Patient dumping has

serious medical implications and can result in denial of necessary emergency care and even death."

Equal Access Rep. at 5. Patients who are inappropriately transferred risk delays in emergency

treatment, life threatening complications, and a higher mortality rate. Id., at 6. See also

Subcomm. Hearing at 157 (testimony of David A. Ansell, M.D., regarding the results of a study

of transfers in Cook County, Illinois); Schiff, Ansell, Schlosser, Idris, Morrison, Whitman,

14

Transfers to a Public Hospital, 314 New Eng. J. Med. 552, 555-56 (1986); Himmelstein,

Woodhandler, Harnly, et al„ Patient Transfers: Medical Practice as Social Triage. 74 Am. J.

Public Health 494 (1984).

Testimony before Congress in 1988 included striking examples of the harms caused by

patient dumping: (1) An indigent woman in Florida suffered from severe interruption of blood

supply to her right arm and sought emergency treatment at a hospital emergency room. The

facility told her not to return to the emergency room until she had the money to pay for treatment

or "until her arm and hand turned black." Subcomm. Hearing at 42-43 (testimony of Judith

Waxman); (2) A Virginia woman was six and one-half months pregnant and was experiencing labor

pains and passing blood clots. She was turned away from her local hospital and told by a nurse

that because she did not have a private doctor, nothing could be done for her. That afternoon,

her premature baby was born, and died a few minutes after birth. The doctor on duty at the

second hospital told her that had a doctor treated her earlier, he could have arrested the

premature delivery. Id., at 43; and, (3) "For unknown reasons," a patient with a femur fracture was

transferred after more than ten hours without treatment. The patient developed severe

complications, including shock lung, and, one month later, he died from these complications.

Early treatment to stabilize femur fractures has been shown to minimize the risk of disability or

death. Subcomm. Hearing at 283 (testimony of Lois Salisbury). The dangers of dumping are

also illustrated in the case presently before this court. A woman nine months pregnant with her

sixth child arrived with the highest blood pressure the physicians on duty had ever seen, 210/130.

The doctor did not want to take care of the patient and transferred her to a hospital located 170

miles away. "Final Decision on Review of Administrative Law Judge Decision" (Dec. No. 1167)

1-2.

The impact will be felt most severely by the poor and the uninsured, those most at risk of

being turned away from emergency rooms. This number includes the more than 30 million

Americans who have no health insurance coverage. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of

Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1989, Table 146.

In addition, the problem of patient dumping will continue to disproportionately affect

15

minorities. See Subcomm. Hearing at 157 (testimony of David A. Ansell, M.D., reporting that the

practice of dumping disproportionately affects Blacks and Hispanics). More than 33 percent of

African Americans and 28 percent of Hispanics live below the poverty level. Bureau of the

Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1989, at Table 734.

Nearly one-half of African American children age sixteen and under, and more than 40 percent

of Hispanic children live in poverty. Id , at Table 736.

Continued denials of access to emergency health care for poor women who are in labor

threatens to exacerbate the already tragic levels of neonatal and maternal mortality among African

Americans. In 1986, the neonatal death rate for black infants was 11.7, compared to 5.8 for white

infants. The maternal mortality rate for black women was 18.8, compared to 4.9 for white women.

Id., at Table 113.

The dangers inherent in the practice of patient dumping are great — and not limited to the

poor. In its 1988 Report on patient dumping, the House Committee on Governmental Operations

estimated that 250,000 patients in need of emergency care annually are transferred for economic

reasons. In addition, the report noted,

Concerns have been expressed that patient dumping will soon

increasingly affect other patient populations.... Patient dumping by

unprofitable diagnosis related groups has been predicted and

dumping of Medicaid patients and a patient with the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome has been reported.

Equal Access Rep. at 5. Indeed, the dumping of individuals with particular diseases or conditions

would not be without precedent. As far back as the early 1800’s, "when voluntary hospitals were

first established, they had the ability to define which patients they did not want to treat: the

chronic and incurable, the ’morally unworthy,’ alcoholics, patients with venereal disease."

Friedman, Problems Plaguing Public Hospitals: Uninsured Patient Transfers, Tight Funds.

Mismanagement, and Misperception, 257 J. Amer. Med. Assn. 1850, 1850 (1987) (quoting Charles

Rosenberg, University of Pennsylvania historian). In addition, some hospitals would not take

children or pregnant women seeking hospital rather than home care. Id. More recently, in 1987,

16

an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggested that patients

with ’undesirable’ conditions, such as intoxication or overdose conditions, may be the victims of

patient dumping. Ansell, Schiff, Patient Dumping: Status. Implications, and Policy

Recommendations, 257 J. Amer. Med. Assn. 1500, 1500 (1987).

No matter what the cause or motivation, the denial of emergency treatment and the

inappropriate transfer of patients represent serious barriers to health care access. With the

passage of COBRA and the 1989 Amendments, Congress took forceful steps to address these

barriers. The imposition of an intent requirement would substantially weaken the statutory

scheme established by Congress and would place the lives of those in need of emergency care at

greater risk.

17

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the Department of Health and Human Services

Departmental Appeals Board should be affirmed.

Respectfully Submitted,

January 9, 1990

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

RONALD L. ELLIS*

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

MARTHA F. DAVIS

ALISON C. WETHERFIELD

NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Amici Curiae

*Counsel of Record

18

APPENDIX A

In re Margaret R. Pardee Memorial Hospital.

(Hendersonville, N.C.; HHS/OCR No. 04803173).

A

; ■.rv . r v ••

- * 'T** • * •. vV — ; /V

' . 4"

- ' . • „t-. • •• . .. - **..*.•

•• • './ ' v.*:**»*• .V .1 r*v

u : ; : i ;

•: *•; v^; V.*̂ - N " .;'■ •*.

/SEP / 1S81

— • i* . tt ■ ■

• V lllle® R* JC^ICOQ^v^;'",-

nIni ; •

rg a re t R. r ; * ~ : V ' X * £

V»i»rtr!*\ ' &>£ni t» l *.'• /H ■ . .

Mr.

Adninisrrator .

*Urg*xet . ^ - - , - - ..-. .

y<TSorl«l Jb$pit»l;:*;; ..{*; •

70S Fleming £ tr c « t --• • • : . - . ~ •

Rendersoovllie# Forth Carolina 76739

Ccar Mr. Jxd so n t - •-, *

• * *-•

U4

r m Cocplalnt -0^-3173

• *•» i . 7 , :

f5mi — - *̂C

*." Greyer t t e evt!»ority o f T i t l e s Yl fcnd'WI o f t ’* Public Service Act

with icple-ac-ntirg reg u la tio n fo r co^^unity service assurance a t. A2 CFP.,

R a t io n s 3?< .<G 3(a)U )(?)Ib) end 124,6M and ru rsusn t touche January 28, .

2«!>6 Furor ancon of Under e ta rdirvg betvoer the Office fo r C ivi* F igh ts and

the Public Health S e rv ice , the Office for C iv il Rights {CCP.) conducted an

In v es tig a tio n o f the oocpieJnt f i le d Scpterc-er ?, If'CS by th e -;; _

- . - * ... or. behalf o f ' ■•. ' ■. a g a in s t .

Karcarfrt f i /P a rd e e Manorial H osp ita l . Tho complaint a l le g e d th a t .1 ' ;>

ves emergency se rv ice s on Jhne 7*: l? ? f because he v?s

unable to pay fo r c e rv ic e s . _ . r: ' - ' ~ *-

Ths Office fo r C iv il R ig h ts ' in v es tig a t io n included an o n - c i t c v i s i t ,

c o l le c t io n o f re lev an t docic 'cnts, ferd interviews u l th the corg^aiA3r.t»

h o s p i ta l personnel, end o th e r ind iv idua ls v i th knowledge re le v a n t to t. i s

" cAso. TMs l e t t e r Is to n o t i f y you of the re su l ts o f our ln v e s t ic a t io n .

On June ?C» 15PP# . vent to Fcrc^o Respite!, fincoopar.iec L̂y Vs

■ Theresa G^ttlton, /cd dlscuc.ce<3 poss ib le flrvanclrl e ss is ta n e n for

V ' - t i c ? tr-ent o f eh in ju red , f in g e r v i t h J io t p i t a l r tp rc sn n tn t iv e s , *^s. Pat

K5\Twsrrt a rd Ks. ‘tu la Hudgins. After hi m is s io n vJth the rep re sen ta t iv e s

-., . ^ l e f t the h o sp i ta l w ithout receiv ing treatment for h is f in g e r . «

! i;' s t a te d th a t he vas denied emergency roccs treatment he v rs toiC ny

Ti- K&. ft-cuirv? t-js t Jtag t r e a te d for the fincer. once and th a t the \

h ‘1 ' h b o r r j t c l could.TK>t jraS'C. fiou-nciel arrangement? v i th £ n in o r . bospi-

% -% - f t 3 l \ n e r i o s i h s c • " . ^ c 'T c f u s e - } cr-trgnnry fe.rvic^s si_nce hs did ^

r ln tn^rce-cy rooa or. .*one 7?,, .

A—1

Mr. V (illia in 2 . J

M argaret R. Pardee Memorial H o sp ita l

H en d erso n v ille , ??orth C aro lin a '

< Page .

Phe le g a l s ta r d ^ d g o v e rn in g 'th e charges o f d is c : irrvlnation ra ised ir, th is

i a s e i s s ta te d a t 42 Cf^v ~ S e c tio n 1 2 4 .6 0 3 ( a ) {1). and ( b ) (1) vh ich reads as

' fo llo w s ;

{a) G eneral* _ . _

( ! ) In 'ord er t o 'comply w ith i t s ccanum ity •._.

s e r v ic e assurance", a f a c i l i t y s h a l l waVe th e s e r

v ic e s provided in the. f a c i l i t y or p o r tio n th e r e o f

c o n s tr u c te d , E t e r n i s e d or converted w ith F ed era l

a s s is ta n c e under'-? i t i e VI or XVI o f the A ct a v a i l

a b le to a i l person s r e s id in g ..(a n d , in th e case, o f

f a c i l i t i e s a s s is t e d order T i t l e XVI o f the A ct, _

employed) in th e f a c i l i t y ’ s s e r v ic e area w ith ou t

'd isc r im in a tio n on th e ground o f ra ce , c o lo r , z~i.

r a t io n a l o r ig in , c r e e d , or any other ground, urr

r e la te d to an in d iv id u a l's need for the s e r v ic e ■

or th e ‘a v a i la b i l i t y o f the^ needed s e r v ic e in th e

f a c i l i t y .

6hd

Cb) Errergency s e r v ic e s ;

(1} A f a c i l i t y m ay,rot deny emergency s e r

v ic e s to any person w h o .re s id es (o r . In th e c a se ;

o f f a c i l i t i e s a s s is t e d under T itle -X V I o f the A ct,

i s c-rrpioved) in the f a c i l i t y ' s s e r v ic e area on th e

ground th at the person is unable to pay for th ose •

serv ices.®

A n a ly s is o f the ev id en ce shoved chat ;'*r-

& ervices In the emergency room on dune 20

grounds o f I n a b il i ty to pay.' E vidence ga

w r itte n emergency room procedures do ro t

_ fa i lu r e to r ece iv e

, 1980 was not based on the .

t ie r e d shov-ed th a t Pardee'a

Involve o b ta in in g any f in a n c ia l

i r.forratIce. from, o a t ie n t s ,

- ,j.u core 1 us. io n , , the. O ff ic e for G i v i i ^ i c h t s . has. determ ined th a t t h e r e . i s -

t n s u f f l c l e n t ” ev id en ce to show M argaret R. Pardoe ?~y~m-or I a l . lo s o ita l v io

la te d i t s ccnraunitv s e r v ic e assu ran ce o b l i c s t i c n s a s . s e t ' f o r t h in T i t l e s

Vp and x v j.c 'f the. P u b lic H ealth S erv ice A ct _i.n i t s a c t io n s on Gene ?0, .•

A-2

.* * %\ >*». •

Order "the J^eedcta of Information Act, the Office fox Civil RightB U ^

required to release rthii .letter-w d related .arterial* in th is c a s e *$>_>* -V&'

'request by onj ac-^bet-of the !pc4)Hci‘\ t t .O e event the Office for Ci v l l -•

r i^ foM Aiirh ‘i: rAoi»*t; W w ill J»ke e-ver? effort' to p r o t e c t *.A

Vt***!? v>e ere cn th is date advising the ccc^ls! rent by letter of our firologs,

__ ____ ___ Af If we aav be of assistanee *.

. . . . . . . ------------ • - . . • - - » i > s v « ' J r * ? . ; - .0CVflHD:?t?Bellorny:vp:2/73/81>'

OCR/flaOiMTBellaroy: vp: 2 /24 /81-cor ractions

OCP/flflJD: KDSell&rov: vp:3/26/81-tevislons

A-3

APPENDIX B

In re Wadlev Hospital II.

(Texarkana, TX; HHS/OCR No. 06803108).

B

- tfp r

( - • • 3 i : f -

DEFARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES p ; < j ~ j g

S A<sr|-.*K

( , Ret. - • * - / ' /

1 4 Ref: 06803108

Mr. James Hughes, Manager

East Texas Legal Services

p . 0 . Box 170

Texarkana, Texas 75501

Dear Hr. Hughes: ’

The Office fo r Civil Rights has completed I t s In v es t ig a tio n o f th e

m raolalnt by East Ter>s l.*a»i Services f i l e d on behalf of

P and a lleg ing th a t Wadley Hospital of Texarkana,

Tex'S v io la ted T it le s YI and XYI of the Public Health Serv ice Act as

amended 1n 1979 by denying 'as- n i emergency trea tm en t, and 1n

requ ir ing ,* to pay for serv ices which should have been provided

t 0 him under the Hill-Burton uncompensated care program. S p e c i f i c a l ly ,

th e complaint charges the hospital with the following: (1 ; cen ia l of.

emergency services based on In a b i l i ty to pay, (2) f a i lu r e to cake

arrangements with th ird -p a r ty payors. (3) an exclusionary admissions

policy (A) fa i lu re to post the S ec re ta ry 's no tice 1n a l l app rop ria te a r e a s ,

of the h o sp i ta l , and (5) f a i lu re to communicate the con ten t of th e posted .

n o t ic e to persons the hosp ita l has reason to believe cannot read the

n o t ic e . '

T i t l e s VI and XVI of the Public Health Service Act as attended In 1979 are

Implemented by Part 124 of T i t le 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations (42

CFR 124). Violations a lleged 1n the complaint r e la te to Subpart F,

“Reasonable Volume of Uncompensated Services to Persons Unable to Pay", and

Suboart G, "Community S erv ice" . The a l le g a t io n s r e la t in g t o Subpart F a re

Inves tiga ted by the Public Health Service A dm inistra tion . Our In v e s t i

gation did not adoress those a l le g a t io n s .

Pursuant to the S ec re ta ry 's delegation of Hill-Burton coo*un1ty se rv ice

enforcement au thority of December 8, 1980 (45 Federal R eg is te r 82721

(12 /16 /80)), the Office fo r Civil Rights has re s p o n s ib i l i ty fo r assu ring

th a t rec ip ien ts of f in an c ia l assis tance from the Department of Health and

Human Services comply with T i t l e s VI and XVI of the Public Health Serv ice

Act (HUl-Burton). Hadley Hospital receives f inancia l a s s i s ta n c e from th e

Department of Health and Human Services. ■

* . . * ■ *

By our l e t t e r dated December 23, 1981, you were provided w ith a surraary o f

th e evidence we had obtained and were given an opportunity to provide

add itiona l Information or evidence to support your com plaint. Although you

wrote to us on January 25, 1982, objecting to our f in d in g s , you did not

provide any additional evidence which would a l t e r our f in d in g s .

n

o m e t .SURNAME T omez I PAT* I o rrxa | a g x _

! o c x * 9 ^ - „ .......... 1_________________

B -l

D E P A R T M E N T OP” HEALTH A N D HUMAN S E R V I C E S 3 I ^

Page 2T- Ms. Marilyn Rauch

Based on the ana lys is -o f the information obtained during our In v e s t ig a t i o n ,

we concluded th a t only one of the a l l e g a t io n s s ta ted above was v a l i d . We

found the h o s p i t a l ’s pol icy and the s igns postdd 1n the emergency room

regarding preadmission or preservice depos i ts to be exclusionary 1n t h a t no

exceptions were allowed for circumstances 1n which the a p p l ica n t could be

expected to pay h1s b i l l but was unable t o make a d ep o s i t , as requ i red by

42 CFR 124.603(d)(3).

The hospi tal was asked to take act ions t h a t would c o rrec t these

v io la t io n s . On December 7, 1982, the hosp i ta l sent to OCR documentation o f

amendments to I t s admission policy and procedures which provide fo r

a l t e r n a t iv e s to deposits for persons who can be expected t o pay t h e i r b i l l s

but who do not have cash for a deposit a t th e time se rv ices are reques ted .

The hospital also assured OCR th a t the s igns 1n the emergency roon which

v io la ted the regulation had been removed several months p rev io u s ly .

In view of the correc t ive action taken to overcome the v io la t io n of 42

C.F.R. §124.603(d)(3), OCR now finds the hospi ta l to be 1n compliance with

the*law and regulation c i t ed with regard t o a l l Issues o f the complaint .

This determination of compliance applies only to the i s sues of th e . . .

a l l eg a t io n s c i t ed above. For your r e fe ren ce , the p e r t in en t f a c t s which *'•

fo ra the basis for our conclusion are summarized In the attachment t o t h i s

l e t t e r . •*

Under the Freedom of Information Act, 1t nay be necessary to re lease t h i s

l e t t e r and re la ted material 1n response to an appropriate request*.

We apprecia te the courtesy you extended to our rep re sen ta t lv e s during t h e i r

v i s i t s . I f you have any questions regarding these m a t te r s , do not h e s i t a t e

to contact us .

S incere ly ,

Davis A. Sanders

Regional Director

Enclosure

o m a fUXNAME DATE

& + 2 -

o m a i SUXKAMZ DAZE oma nrrxAMM

c

A T T A C H M E N T

WADLEY HOSPITAL «

Texarkana, Texas

Issue ?1

Whether Wadley Hospita l , in v io la t ion of 42 C.F.R. 124 .603(b)(1 ) , denied

emergency services to and denies them to o ther indigent

c i t i z e n s on the ground of I n a b i l i t y to pay.

42 C.F.R. 124.603(b)(1) s t a t e s :

A f a c i l i t y may not deny emergency serv ices to any person who

res ides in the f a c i l i t y ' s service area on the grounds t h a t

the person is unable to pay for the s e rv ic e . "

Summary of Facts __

All evidence shows th a t i n a b i l i t y to pay was not the basis fo r

the emergency room d o c to r ' s f a i l u r e to administer medical care to her son.

In accordance with ho sp i ta l procedure, his v i t a l signs were taken and his

physician was contacted by a s t a f f nurse. The decision to send Tyrone

Hunter to the doc to r 's o f f i c e was made by an appropria te medical person.

The length of time spent in the emergency coom was not any l o n g e r

than the time spent by o ther p a t i e n t s . Furthermore, the charges fo r the

emergency care were paid by a th i rd -p a r ty payor program (Medicaid). -

There is no evidence of o ther indigent c i t i z e n s being denied emergency

se rv ices at Wadley H osp i ta l .

OCR concludes th a t Wadley Hospital did not v io la t e 42 C.F-R. 124.603(b)(1)

with regard tc ■ . a l l eg a t io n s .

Whether Wadley H osp i ta l , in v io la t ion of 42 C.F.R. 124.6 0 3 (c ) ( 1 ) ( i ) and

( i i ) , f a i l e d to make arrangements for reimbursement for se rv ice s from S ta te

and local government t h i r d - p a r t y payors for se rv ices provided by the

hosp i ta l t o * : or m » <-eT

*42 C.F.R. 124.603(c)(1) ( i ) and ( i i ) s t a t e :

(c) Third-party programs. (1) The f a c i l i t y shal l make

arrangements, i f e l i g i b l e to do so, for reimbursement for

se rv ices with:

( i ) Those p r in c ip a l S t a t e and local governmental t h i r d - p a r t y

payors t h a t provide reimbursement for s e r v i c e s . . .

B-3

C

" 3 f i 2

Page 2

( i i ) Federal Governmental t h i r d - p a r ty programs such as*

Medicare and Medicaid."

Summary of Facts

Vie found th a t Wadley Hospital had made arrangements with S t a t e and Federal

t h i r d - p a r ty payors for reimbursement of se rv ices . With regard t o t h e

complaint in c id en ts : 1) services provided by Wadley Hospital to

were b i l l e d to and paid by Texas Medicaid; and 2) . was

released from Bowie County J a i l at the time he was admitted to Wadley

Hospital and on his dismissal from the hospi ta l signed forms agreeing to

pay for his b i l l . - However, he did not pay, and the charges were w r i t t e n

o f f as c h a r i ty .

The in v e s t ig a t io n revealed tha t Wadley Hospital p a r t i c i p a t e s in th e

following t h i r d - p a r ty payor programs: Medicare, Medicaid, Champus,

Workmen's Compensation, Northeast Texas Mental Health/Mental Re ta rda t ion

Center, and Community Action Resource Services (CARS), In c .

We have f u r th e r determined tha t Bowie County, Texas, in which Wadley

Hospital i s loca ted , including the county j a i l , does not hayo any

t h i r d - p a r ty payor programs through which*'a hospital can be reimbursed by

the county for medical services provided to ind igen ts .

OCR concludes t h a t Wadley Hospital i s in compliance with 42 C.F.R. 124.503

(c)(1) with respect to t h i s issue . . :

Issue #3

Whether Wadley H osp i ta l , in v io la t io n of 42 C.F.R. 124 .6 0 3 (d ) (3 ) , requ ires

preadmission deposi ts before admitting or serving p a t i e n t s .

42 C.F.R. 124.603(d)(3) s t a t e s :

. . . I f the e f f e c t of [a f a c i l i t y ' s requiring advance d e p o s i t s

before admitting or serving p a t i e n t s ] is that some persons -

are denied adm iss ion . . . or se rv ice so le ly ' te cau se they do

not have the necessary cash on h a n d . . . [ t h e f a c i l i t y ] i s

required to make a l t e rn a t iv e arangements to ensure t h a t

persons who probably can pay fo r the services are not denied

them simply because they do not have the avai lab le cash a t

the time se rv ices are r e q u e s te d . . . "

Summary of Facts

While the community service regula t ion does not require th e f a c i l i t y to

forego the use of a deposi t ro l icy in' a l l s i tu a t io n s , i t i s requ ired to

m a k e a l t e r n a t i v e arrangement: to 'en su re th a t persons who probably can pay-,

fo r the se rv ices are not denied them simply because they do not have the

a v a i lab le cash a t the time services are requested.

B-4

c

Page 3

3ft

We found th a t the h o s p i t a l ’s f inancial p o l ic ie s do not show s p e c i f i c excep

t ions Sr when the exceptions are to be applied fo r waiving depos i t

r e t i r e m e n t s under circumstances in which the app l ican t can be expected to

Day h1s b i l l but i s unable to make a depos i t . The h o s p i t a l , t h e r e f o r e , i s

in v io la t ion of t h i s sect ion of the regu la t ion . _ •

Further ‘signs were found in the emergency room-area s t a t i n g , "Cash deposi t

r e t i r e d before s e r v i c e s . ' A sign t h a t ind ica te s t h a t preadmission de-

n o s i t s wil l be required Of a l l persons as a precondit ion f o r t rea tm ent or

service v io la te s 42 C.F.R. 124.603(d)(3) s ince the e f f e c t o f such a sign

wil l be to deny admission or services or sub jec t p a t i e n t s t o delay in

receiving s e rv ice s .

On December 7, 1982, the hospital sent OCR a copy of i t s rev ised admission

oolicy and procedures which provide for a l t e r n a t iv e s to d epos i ts f o r

oersons who can be expected to pay t h e i r b i l l s but who do not have cash fo r

a depsi t a t the time services are requested. The h o sp i ta l a lso assured OCR

th a t the signs re fe r red to had been removed several months p re v lo s ly . The

act ions by the hosp i ta l are considered adequate to c o r r e c t th e v io la t io n

n o t e d a b o v e .

Issue #4

’"--‘ her Wadley H ospita l , in v io la t ion of 42 C.F.R. 124.604(a) , has f a i l e d

tcTpost the S e c re ta ry ’s not ices in English and Spanish in a l l appropr ia te

areas of the h o s p i t a l .

42 C.F.R. 124.604(a) s t a t e s :

The f a c i l i t y sha l l post no t ices , which the S ec re ta ry ■

supplies in English and Spanish, in appropria te a reas of th e

including but not l im ited to the admissions a re a ,

the business o f f i c e and the emergency room.

Summary of Facts

An inspect ion of the f a c i l i t y by OCR in v e s t ig a to r s revealed t h a t t h e

S ec re ta ry 's not ices had been posted, both in English and Spanish, i n the

appropria te areas of the f a c i l i t y , inlcuding the admiss ion-business o f f ice

and emergency room a rea . The evidence ind ica te s t h a t th e signs were posted

' i n l a t e September or early October 1979. Wadley,Hospital i s in compliance

with 42 C.F.R. 124.604(a) with regard to t h i s I s su e .

Issue #5

Whether Wadley Hospita l , in v io la t ion of 42 C.F.R. 124.604(c) , has f a i l e d