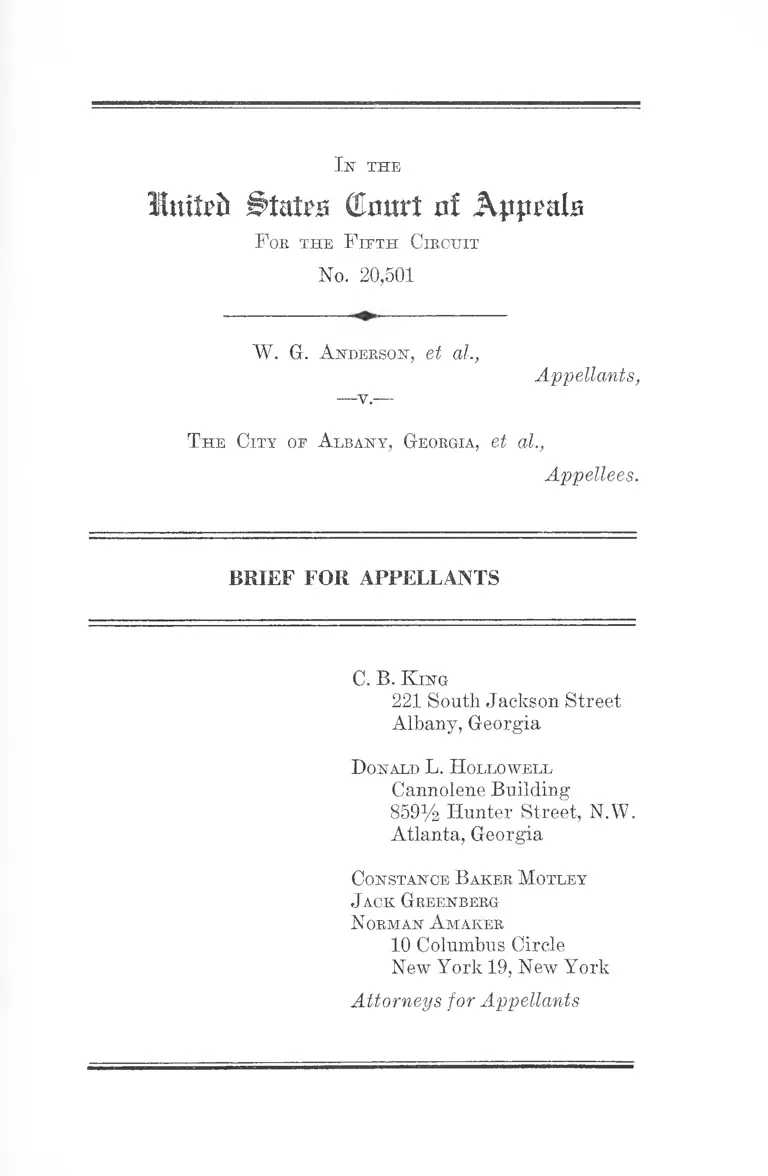

Anderson v. City of Albany, GA Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 23, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Anderson v. City of Albany, GA Brief for Appellants, 1963. 21b97545-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/635b203f-0469-4c38-a8db-87b5d488b7c8/anderson-v-city-of-albany-ga-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Initefc i>tatpa (Burnt rtf Apprala

F or the F ift h Circuit

No. 20,501

W. G. A nderson, et al.,

Appellants,

— v .—

T he City of A lbany, Georgia, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

C. B. K ing

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

D onald L. H ollowell

Cannolene Building

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

Norman A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ......................... ......................... 1

Statement of the Facts ...................................... ....... 6

Specifications of Errors ................................................ 14

A rgument

I. Dismissal of This Cause by the Court Below on

the Ground That the Action Was Not Main

tainable by Appellants as a Class Suit Was

Erroneous ............... 15

II. Refusal to Enjoin Continuation of Appellees’

Policy and Practice of Enforced Segregation

in Its Public Facilities and to Enjoin Inter

ference With Peaceful Protest Against That

Policy and Practice Denied Appellants’ Consti

tutional Rights .................. 22

Conclusion ................................................. 27

T able of Cases

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 D. S. 31, 7 L. ed. 2d 512

(1962) ..................................................................15,21,24

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958) ....... 20

Blazer v. Black, 196 F. 2d 139 (1952) ........ ................... 26

Bowles v. J. J. Schmidt and Co., 170 F. 2d 617 (2nd

Cir. 1948) ................................................................... 26

Browder v. Gayle, 352 U. S. 903 (1956), affirming 142

F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956) 24

11

PAGE

Brown v. Board of Trustees of LaGrange, Ind. School

Dist., 187 F. 2d 20 (1951) ....................................... 15

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940) .......... 25

City of Montgomery v. Gilmore, 277 F. 2d 364 (5th

Cir. 1960) ..... ........................................................... 22

City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th

Cir. 1956) .....................................-.......................... 24

Cobb v. Montgomery Library, 207 F. Supp. 880 (M. D.

Ala. 1962) .......................... ....................................... 24

Dawson v. Mayor of the City of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d

386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 .............. ...... 23

Edwards v. South Carolina, -----TJ. S. ------ , 9 L. ed.

2d 697 (1963) ............................................................. 25

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 (1958) ...................... 20, 21

Fields v. South Carolina (1963), ------ U. S. ----- , 9

L. ed. 2d 965 ........................... ................................. 25

Fireside Marshmallow Co. v. Frank Quinlan Construc

tion Co., 199 F. 2d 511 (8th Cir. 1952) ..................... 26

Flowers v. City of Memphis, Civ. No. 3958 (W. D.

Tenn. July 11, 1962) ....... .......................................... 24

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, 246 F. 2d 913 (1957) ................................... 18

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ..................... 25

Hanes v. Shuttlesworth, 310 F. 2d 303 (1962), affirming

Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord, 202 F. Supp. 59 (N. D.

Ala. 1961) ................................................................. 20

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 H. S. 879 (1955) .......... 24

Hutches v. Renfroe, 200 F. 2d 337 (5th Cir. 1952) ...... 26

Ill

PAGE

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S.

151, 59 L. ed. 169, 25 S. Ct. 69 (1914) ............. ....... 15

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (1962)............... ................ ig

Tate v. Department of Conservation and Development,

352 U. 8. 838 (1956) ..............................................._ ’ 24

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S. 88 (1940) ................. 25

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 IT. S. 350 (1962) ..... 24

Turner v. Randolph, 195 F. Supp. 677 (W. D Tenn

1961) ........................................................... ............. 24

I n the

Itttfrft Butw ( to r t nf Appeals

F or the F ift h Circuit

No. 20,501

W . G. A nderson, el al.,

Appellants,

T h e City of A lbany, Georgia, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This appeal is from a final order of the United States

District Court, Middle District of Georgia, Albany Divi

sion, entered March 15, 1963. The order appealed from

dismissed this action, consolidated with two other related

cases, after a full trial on the merits. The two other cases

remain undecided.

All three cases arise out of attempts by the Albany Move

ment, an unincorporated association of individuals, pre

dominantly Negroes, to desegregate publicly owned and

operated recreational, library and auditorium facilities in

the City of Albany, Georgia. Desegregation of taxicabs,

theatres, local buses, the bus depot and train station were

also objectives. In addition, the Albany Movement sought

to persuade private business establishments, such as de

partment stores patronized by Negroes, to employ Negroes

and to end discriminatory treatment of Negroes within

these establishments (R. Vol. Y, pp. 25B-26B).

2

Desegregation of all public facilities was initially sought

by petitioning the appellee Mayor and Board of Commis

sioners of the City of Albany to change the City’s separate-

but- equal policy in the order of priority suggested by the

Albany Movement. City officials flatly refused all demands.

This blanket refusal led to a different approach designed

to force the City officials to negotiate the issues, i.e., peace

ful picketing and non-violent protest demonstrations against

segregation. Department stores were picketed, Negro and

white demonstrators attempted to use public facilities on

an integrated basis, and prayer vigils were held or at

tempted in front of City Hall by groups led to the center

of town by the leaders of the Albany Movement in columns

of two walking on the sidewalk and observing traffic signals.

The first case, filed in the court below on July 20, 1962 by

the Mayor, the City Manager and the Chief of Police of

Albany sought to enjoin these protest demonstrations and

the picketing. The complaint alleged that the action was

brought:

” . . . to vindicate rights of the citizens and inhabitants

of the City of Albany, Georgia, a public corporation,

to the free and equal use of the streets, sidewalks and

other public places in and about the City of Albany;

to secure to said citizens and inhabitants equal pro

tection of the laws as guaranteed to them by the Con

stitution of the United States; and to secure to said

citizens and inhabitants the free and uninterrupted use

of their respective private properties, free from or

ganized mass breaches of the peace which tend to pre

vent and hinder plaintiffs and other duly constituted

authorities from according to said citizens and inhabi

tants the equal protection and due process of the law.”

The relief sought was an injunction enjoining the Albany

Movement and others from:

3

“ . . . continuing to sponsor, finance, incite or encourage

unlawful picketing, parading or marching in the City

of Albany, from engaging or participating in any un

lawful congregating or marching in the streets or other

public ways in the City of Albany, Georgia; or from

doing any other act designed to provoke breaches of

the peace or from doing any act in violation of the

ordinances and laws [parading without a license, dis

turbing the peace, etc.] hereinbefore referred to.”

Based upon the allegations of this complaint, a tempo

rary restraining order without notice was issued by the

court below enjoining the Albany Movement, and others,

as requested on July 20, 1962 at 10:55 o’clock P. M. and

setting a hearing on the restraining order for July 30, 1962.

Thereafter, the District Judge left the state. On July 24,

1962, on application of the Albany Movement and others,

an order was entered by Chief Judge Tuttle of this Court

vacating the temporary restraining order on the ground

that: 1 ) the court below was clearly without jurisdiction

to enter such an order, and 2) the order was under the

circumstances a temporary injunction, since the District

Judge had been absent from the state ever since defendants

had notice of the signing of the order.

The second case, the instant appeal, was filed on July 24,

1962 to enjoin city officials from continuing to enforce

racial segregation in public libraries, parks, playgrounds,

and the city’s auditorium. Plaintiffs also sought to enjoin

the enforcement of racial segregation in privately owned

and operated buses, taxicabs, theatres and other places of

public amusement as required by local ordinances. In addi

tion, the prayer of the complaint sought to enjoin defen

dants from threatening to arrest, arresting, and harrassing

plaintiffs and members of their class while utilizing or

attempting to utilize public or privately owned facilities

4

referred to in the complaint. With the complaint, appel

lants filed a motion for preliminary injunction with notice

that the motion would be brought on for hearing on August

1, 1962. However, this motion was not heard until August

30, 1962 because on August 1, 1962 the trial court was

hearing testimony in the City’s suit. That testimony was

heard after the motion of the Albany Movement and others

to dismiss that suit on the ground that, as Judge Tuttle

had held, “the federal court clearly had no jurisdiction to

hear such a case” was overruled. Testimony in the City’s

case commenced on July 30 and continued through August

3rd, recessed until August 7, and ended August 8, 1962.

At the conclusion of the City’s case, appellants requested

an early hearing on their motion for preliminary injunction

in this case which was denied on the ground that the court

had other business. Hearing on the motion for preliminary

injunction did not commence until August 30 at 2 o’clock

P. M., at which time, over the objections of appellants, the

instant case was consolidated with the City’s case and a

second case brought by appellants and others to enjoin in

terference with peaceful picketing and protests against

segregation.

After consolidation, appellees were permitted to argue

their motion to dismiss the complaint for approximately

2% hours. After a brief argument by appellants, decision

on the motion was withheld pending testimony. Testimony

did not begin until August 31, 1962. Appellants concluded

their case at the end of that day. The court then continued

the hearing until further notice. Appellants moved for an

immediate preliminary injunction based on the testimony

already before the court and the testimony in the City’s

case. This was denied (E. Yol. V. pp. 197 B-198 B). Testi

mony in the instant case was not resumed until September

26, 1962 and concluded on that date. Testimony in the third

suit brought by appellants was also concluded on that day.

5

The third suit, the second filed by appellants, also had

been filed on July 24, 1962. It seeks to enjoin city officials

from continuing to deny Negro citizens the right to peace

fully picket and protest against racial segregation in the

City of Albany, and from continuing to thwart such activ

ity by arrest, threat of arrest, abuse of state court process,

state court injunction, harassment and intimidation.

By agreement of counsel for both parties, at the conclu

sion of all the testimony on September 26, 1962, the court

below considered the testimony as that offered on a final

hearing.

At the conclusion of the testimony on September 26, 1962,

appellants also renewed their motion for a preliminary

injunction (R. Vol. VI. pp. 318 B-319 B). However, there

was no ruling by the court until February 14, 1963, when

appellees’ motion to dismiss was granted dismissing this

case on the ground that appellants had not, themselves,

been denied admission to or segregated in any public facil

ity, and, since appellants had not been denied or segre

gated, they could not sue for the class which they purported

to represent (R. Vol. VI. pp. 324 B-328 B).

A notice of appeal was filed after the opinion and order

dated February 14,1963 (R. Vol. VI. p. 329 B). Thereafter,

the District Judge, pursuant to inquiry by appellants’

counsel as to whether this was the final order, entered

another order on March 15, 1963 dismissing the case. This

order has been sent up in a supplemental record. A second

notice of appeal was filed on the same date (R. Vol. VI.

p. 329 B). The record was docketed here on April 24, 1963.

The testimony in all three cases has been brought here

because the cases were consolidated for trial, thus making

the testimony common to all. Moreover, the prayer of the

complaint in the instant action was for “such other, fur

ther, additional or alternative relief as may appear to a

6

court of equity to be equitable and just in the premises”,

thus entitling appellants to any other relief to which the

evidence might show they are entitled whether they have

specifically prayed for it or not.

This appeal is, therefore, from the final order dismissing

the case after a full trial on the merits and from failure

of the court below to grant an injunction enjoining: 1 )

state enforced racial segregation in all public parks, libra

ries and the City auditorium, whether by policy, custom

or usage; 2) enforcement of the City ordinances requiring

segregation in taxi-cabs, at theatres, and on buses; 3) ar

rests for peaceful picketing of department stores and other

private business establishments open to the public; 4)

arrests for orderly prayer vigils in front of City Hall;

5) arrests for walking two abreast on the sidewalks to

City Hall while observing all traffic signals; 6) arrests for

attempting to use public recreation, transportation, and

library facilities on an integrated basis.

Statement of the Facts

The plaintiffs in this case are Dr. W. G. Anderson, presi

dent of the Albany Movement, Elijah Harris, Slater King

and Emanuel Jackson, members of the Albany Movement,

who brought this suit on behalf of themselves as residents

of the City of Albany, Georgia and other members of the

Albany Movement similarly situated (R. Vol. Y, pp. 119B-

120B, 127B-128B).

All public facilities in Albany are under the immediate

jurisdiction of the City Manager who is responsible to the

City Commissioners. The City Commissioners, as well as

the City Manager, were made defendants in this suit. The

library facilities in Albany are under the control of the

Board of Trustees of the Carnegie Library. The trustees

7

are appointed by the City Commissioners. The members

of this Board were also made defendants in this action (R.

Vol. V,pp. 28B-30B, 43B).

Recreational policy for the City is determined by the

Commissioners (R. Vol. V, pp. 29B-30B). Library policies

are determined by the Board, but with respect to the re

quest by Negro residents of Albany to desegregate the

libraries, the Board determined that it would let the City

Commissioners make that decision since it contributes the

most financial assistance (R. Vol. VI, p. 226B).

The Albany Movement, a non-violent anti-segregation

protest organization organized in November 1961, has as

its purpose desegregation of all publicly owned or oper

ated facilities and private businesses patronized by Negroes

in the City of Albany. Employment of Negroes is also a

program objective (R. Vol. V, pp. 25B-26B, 120B-121B,

139B). At the first meeting, the minutes reveal, the organi

zation decided to seek to achieve its goals in the following

order: bus stations, train stations, libraries, parks, hospi

tals, local city buses, municipal employment, jury repre

sentation, job opportunities in private employment (PI.

Exh. 1). The organization also decided that one of the

grievances it would seek to have redressed by city officials

was the matter of police brutality (PI. Exh. 1, No. 730).

Prior to the organization of the Albany Movement, Dr.

Anderson met with the appellee mayor of Albany and sug

gested to him that a biracial committee be appointed to

bring about desegregation of all public facilities. The mayor

never replied to this request (R. Vol. V, pp. 102B-103B).

November 1961, Dr. Anderson and three others met with

the mayor and presented him with a copy of the minutes

of the first meeting. At this meeting, Anderson asked the

mayor to “prevail upon the City Commission to seek means

of peaceful desegregating the City of Albany’s public facili

ties” (R. Vol.V,p. 103B).

At the next regular meeting of the appellee Commis

sioners, Dr. Anderson appeared and requested a reply to

the Albany Movement’s desegregation requests. The mayor

replied that these requests had been considered but there

were no common grounds for agreement (R. Vol. V, pp.

104B-105B).

Thereafter, in January 1962, after another appearance

by Dr. Anderson at a regular meeting of the Commission,

a written statement was published in a local newspaper, the

Albany Herald, setting forth the Commission’s views (PL

Exh. 4, R. Vol. V, pp. 54B-59B, 105B-106B). Dr. Anderson

appeared before the Commission on a subsequent occasion,

again with reference to the Albany Movement’s demands,

but no action was taken (R. Vol. V, pp. 59B-60B).

In addition, Dr. Anderson, as president of the Albany

Movement, discussed desegregation of all public facilities

with the mayor on numerous occasions and requested action

but none was taken (R. Vol. V, pp. 55B-56B, 83B). Finally,

with respect to all requests for desegregation, the City

Commissioners advised Dr. Anderson to “go to court” since

there were no areas of agreement (R. Vol. IV, pp. 777A-

778A, 781A-783A).

Upon the hearing, the mayor admitted that the City Com

missioners had discussed desegregation of the swimming

pool and recreational facilities in the parks and the public

libraries (R. Vol. V, pp. 35B, 37B, 40B-41B, 45B). The

Commission also discussed the city ordinances requiring

racial segregation (R. Vol. V, pp. 47B-50B). One ordinance

required segregation on buses. Another ordinance required

discrimination by taxicabs in that the taxicabs were re

quired to carry only Negro or white passengers and to

indicate same by a sign on the door of the cab. The third

9

ordinance required that theatres provide separate lines for

Negroes and whites seeking to purchase tickets (PI. Exhs.

2 and 3). In addition, the City Commissioners had dis

cussed segregation in the waiting rooms of the train and

bus stations sought to be desegregated by the Albany Move

ment and where Negroes had been arrested following the

ICC order of November 1, 1961 prohibiting segregation

(R. Vol. V, pp. 51B-52B). However, despite these discus

sions there was no official action taken (R. Vol. V, pp.

55B-56B).

The City’s policy was best defined by the mayor’s candid

pronouncements on cross examination by his own counsel.

He described, in detail, the separate facilities available to

Negroes and asserted that they were comparable to those

available to whites, based upon the relative population

percentages of the two groups. There is no doubt in this

record about the City’s policy. The mayor stated, for ex

ample, that Carver Park was “designed” for members of

the Negro community (R. Vol. V, pp. 60B-61B, 63B-64B)

and that he and the other white people in Albany would

rather see the swimming pools closed than integrated (R.

Vol. V, pp. 64B-65B, 76B-77B).

The P arks

There are three major parks in the City of Albany—

Tift Park, Carver Park and Tallulah Massey Park (R.

Vol. V, p. 28B). Both Tift Park and Tallulah Massey

Park were designed for the white citizens of Albany,

although Negroes were permitted to use picnic areas in

Tift Park and to visit the zoo (R. Vol. V, pp. 30B, 32B,

40B). The swimming pool and rides for children in Tift

Park were restricted to whites. Tift Park contains an

Olympic sized swimming pool which is the only one in the

City (R. Vol. VI, p. 250B). Carver Park has a much

10

smaller pool (E. Vol. V, pp. 31B-32B; Vol. VI, p. 234B).

The parks were closed by the police daring the Albany

Movement’s attempts to desegregate Tift Park (R. Yol.

VI, pp. 259B-268B). They have remained closed except

for the zoo and the concession stands (E. Vol. VI, pp.

256B-257B). These parks also contain teen centers, the

one in Tift Park being limited to white teenagers. Tift

Park also has a hobby shop limited to whites. A similar

facility was located in the teen center in Carver Park

(R. Vol. V, pp. 32B-33B).

Libraries

There are two libraries in the City of Albany, the main

library, Carnegie Library, is limited to white citizens.

Albany recently constructed at a cost of $25,000 a newT

library known as the Lee Street Branch for Negroes.

“If a person [Negro] wants a book from the Carnegie

Library, all he has to do is to request it and it will be made

available at the other library” (R. Vol. V, pp. 43B-44B,

63B). The libraries were closed also by the police depart

ment, without the knowledge of the Board of Trustees of

the Carnegie Library, after Negroes attempted to use the

Carnegie Library (R. Vol. VI, p. 221B).

A u ditoriu m

The auditorium in controversy is owned and operated

by the City but is sometimes leased to private groups

for functions either limited to the membership of the

group or open to members of the public. Seating in the

auditorium is segregated (R. Vol. V, pp. 86B-88B). When

ever Dr. Anderson has visited the auditorium he has been

directed to the area reserved for Negroes (R. Vol. V, pp.

111B-112B). The City permits the lessee of the auditorium

to determine whether the patrons of the affairs will be

segregated (R. Vol. V, p. 86B).

11

T he C ity’s T ran sporta tion Facilities

The Cities Transit, Inc. operated buses in the City of

Albany pursuant to a franchise granted by the City.

Negroes sought to desegregate the buses in Albany through

the Albany Movement. When the Albany Movement failed

to accomplish this, Negroes refused to ride the buses,

as a result of which the bus company went out of business

and is still out of business (R. Vol. V, pp. 67B-68B).

However, Negroes were arrested following the I. C. C.

order of November 1961 in the interstate bus depot and

in the train station for going into the white waiting room

and restaurant (R. Vol. I, pp. 153A-155A, 159A-160A,

162A; Vol. V, pp. 167B-169B).

P laintiffs’ Use o f P ublic Facilities

Plaintiff Anderson testified that he went to Tift Park

for the purpose of swimming one Sunday in July 1962;

the Negro pool in Carver Park was closed (R. Vol. V,

p. 137B). A member of his party, a white person from

New York City, sought to purchase a ticket for admission

to the pool and was denied (R. Vol. V, pp. 137B-138B).

Anderson’s son was refused when he sought to ride on the

the rides for children in the Park (R. Vol. V, pp. 108B-

110B). Anderson had been segregated in the city audito

rium on at least four occasions (R. Vol. V, p. 112B).

The other plaintiffs did not testify as to the use of any

public facilities. The court would not permit Dr. Anderson

to testify about his inability to secure taxicabs for guests

in his home on the ground that a cab driver had a right

to carry anyone he chose and there was no connection

with the City of Albany shown although the evidence is

clear that taxicabs in Albany are marked “For White”

or “For Colored” as required by City Ordinance (R. Vol.

V, pp. 144B-148B, 98B, 71B, PI. Exh. 3).

12

A rrests o f A ppellan ts and O thers

After petitioning city officials to desegregate public facil

ities, appellants did not use or attempt to use any public

facility in the City of Albany reserved for white persons,

except Appellant Anderson who attempted to swim in

the pool at Tift Park. He was not arrested on that oc

casion. However, other Negro persons were arrested when

they tried to use the library in the City of Albany (R. Vol.

V, pp. 110B-111B). A Negro girl was arrested for

refusing to move to the back of a local city bus when

the buses were in operation (R. Vol. V, pp. 155B-162B;

Vol. VI, pp. 199B-211B). A Negro man was arrested

when he and a companion went into the white restaurant

in the Trailways Bus Terminal in Albany (R. Vol. V,

pp. 167B-169B). After the I. C. C. ruling of November 1,

1961, barring segregation, Negroes were repeatedly ar

rested in the white waiting room of the Trailway Bus

station (R. Vol. I, pp. 153A-155A, 159A-160A, 162A).

A cab driver was arrested for carrying white passengers,

without charge, who were stranded on the outskirts of

the City and requested that he drive them into the City.

This driver was convicted and fined (R. Vol. V, pp. 96B-

102B). Negro high school students were arrested by the

Chief of Police when they conferred with the owner of

a local theatre about the owner’s segregation policy which

resulted in the students having to leave their seats on

one occasion to make room for the white patrons in the

Negro section (R. Vol. V, pp. 178B-185B).

Appellant Anderson was arrested in front of City Hall

for picketing (R. Vol. V, p. 149B; Vol. I, pp. 144A-145A)

and for picketing in front of department stores along

with appellants King, Harris and Jackson (R. Vol. IV,

pp. 889A-891A). When appellants were arrested, they

were carrying signs in front of stores in the 100 block

13

of North Washington Street, Two of them wTere on one

side of the street and two on the other (R. Vol. V, pp.

149B-151B). The sign carried by Dr. Anderson read:

“Walk, live and spend in dignity” (R. Vol. IV, p. 889A).

Other Negroes were also arrested for similarly picketing

in small numbers (R. Vol. I, p. 249A). Still others in

small numbers were arrested for participating in a prayer

vigil in front of City Hall (R. Vol. I, pp. 144A-145A,

146A). Appellant Anderson was also arrested for leading

a group of persons to City Hall while walking on the

sidewalk two abreast. Dr. Anderson testified traffic signals

were observed. The Chief of Police testified they were not

(R. Vol. I, pp. 41A-43A; Vol. IV, pp. 895A-896A).

V iolence

There was never any violence in the use of parks by

Negroes or whites at the time that the Chief of Police

closed them and at the time Negroes sought to use the

libraries. The Chief merely anticipated violence (R. Vol.

VI, pp. 259B-261B; Vol. V, pp. 110B-111B). As a matter

of fact, there was never any violence on the part of any

appellant or others identified as members of the Albany

Movement.

P erm it D enied

A permit to hold a protest demonstration against segre

gation was denied the Albany Movement by the City Man

ager whose duty it is to issue permits for parades or

demonstrations (R. Vol. IV, p. 893A).

14

Specifications of Errors

The court below erred in :

1. Granting appellees’ motion to dismiss this cause on

the ground that appellants were not arrested or

segregated in the use of any public facility and con

sequently could not maintain this action as a class

action on behalf of others who were so arrested

or segregated.

2. Refusing to enjoin the appellees from:

a. continuing to enforce racial segregation in pub

licly owned and operated libraries;

b. continuing to enforce racial segregation in the

publicly owned and operated auditorium;

c. continuing to enforce racial segregation in pub

licly owned and operated parks and playgrounds

and the recreational facilities thereof;

d. continuing to enforce racial segregation in pri

vately owned and operated buses and bus depots;

e. continuing to enforce racial segregation in pri

vately owned and operated taxicabs;

f. continuing to enforce racial segregation in pri

vately owned and operated theatres and other

places of public amusement.

3. Refusing to enjoin appellees, Asa Kelley, Mayor of

Albany, Stephen Roos, City Manager, The Board of

City Commissioners and Laurie Pritchett, Chief of

Police from denying appellants’ right of peaceful

protest against racial segregation by arrests for

peacefully walking two abreast upon the public side

walks of the City of Albany observing all traffic

15

regulations, by arrests for prayer vigils, by arrests

for peaceful picketing, and by denial of permits or

appropriate approval for peaceful demonstrations.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Dismissal of This Cause by the Court Below on the

Ground That the Action Was Not Maintainable by Ap

pellants as a Class Suit Was Erroneous.

In its opinion of February 14, 1963, the court below cit

ing Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31, 7 L. ed. 2d 512 (1962)

and McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & S. F. By. Co., 235 U. S.

151, 59 L. ed. 169, 25 S. Ct. 69 (1914) as well as Brown

v. Board of Trustees of LaGrange, Ind. School Dist., 187

F. 2d 20 (1951), ruled that appellants here did not repre

sent the class on whose behalf they brought suit because

it had not been shown that they had ever been denied

access to the public facilities in suit or had been compelled

to use them on a segregated basis. The Court stated that:

. . . the plaintiffs have not been denied the rights nor

suffered the injuries referred to in the complaint. This

being so, the plaintiffs lack standing to seek injunctive

relief for others who may have been injured, because

the plaintiffs cannot represent a class of whom they

are not a part (R. Yol. VI, p. 328B).

The Court, therefore, also denied relief to appellants in

their individual capacities. Appellants submit that the

court below erred because it failed to accord proper sig

nificance to 1 ) the character of the action brought and,

2) the facts relative to appellants’ standing as revealed in

the record.

16

1) The character of this suit is essentially the same as

the action brought on behalf of Negro school children to

desegregate the public school system of Fort Worth, Texas,

in Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (1962). As in Potts v. Flax,

appellants here instituted this action for the purpose of

eradicating a city-wide policy of racial discrimination

against Negroes in the use of the Albany, Georgia public

facilities. Though this action does not seek class injunctive

relief against school segregation, the principles which this

Court found determinative of the propriety of the existence

of a class suit in Potts are controlling here where the in

terests of an entire community of Negro citizens are in

volved.

In Potts v. Flax, supra, this Court said that:

Properly construed the purpose of the suit was not to

achieve specific assignment of specific children to any

specific grade or school.4 The peculiar rights of spe

cific individuals were not in controversy. It was di

rected at the system-wide policy of racial segregation.

It sought obliteration of that policy of system-wide

racial discrimination. In various ways this was sought

through suitable declaratory orders and injunctions

against any rule, regulation, custom or practice having

4 Contrary to the formal suggestion of mootness or want of

parties filed with us by the Board, maintenance of a case making

a frontal attack on a policy of system-wide segregation does not

depend on the presence of one specific child making formal demand

for admission to an all-white school as the one closest to the

student’s residence. Plans for desegregation often provide for this

during the transitional stage. But the constitutional right asserted

is not to attend a school closest to home, but to attend schools

which, near or far, are free of governmentally imposed racial dis

tinctions. Incidents are not required to ‘make’ a ease. Gibson v.

Board of Public Instruction of Dade County, 5 Cir. 1957, 246 F. 2d

913; Baldwin v. Morgan, 5 Cir. 1958, 251 F. 2d 780, 787. The fact

that one or more of the Teal children or the Flax child may no

longer live closer to a white school does not alter this suit.

17

any such consequences. The case therefore had those

elements which are sometimes suggested as a distinc

tion between those which are, or are not, appropriate

as a class suit brought to5 vindicate constitutionally

guaranteed civil rights. The pleaded reason for chal

lenging the class suit was, therefore, unfounded. 313

F. 2d at 288-289. (Emphasis supplied.)

Appellants submit that “properly construed” the purpose

of this suit was to achieve relief against the long-standing

policy of racial discrimination directed against the residents

of Albany, Georgia as a class and the principles which con

strained this Court in Potts to hold that class relief was

appropriate are applicable here.

2) In Potts, the propriety of a class suit was determined

by “what the total record revealed, not upon the conclusory

declarations (pleaded or oral) of the litigants.” 313 F. 2d

288. Due consideration of what the total record here re

veals supports the conclusion that contrary to the lower

court’s determination, these appellants have in fact been

denied the rights and suffered the injuries referred to in

the complaint and, therefore, have ample standing to seek

injunctive relief for themselves and for the class of which

they are a part.

5 See 2 Barron & Holtzoff §562.1 (Wright ed. 1961) ; and com

pare Reddix v. Lucky, 5 Cir., 1958, 252 F. 2d 930, and Sharp v.

Lucky, 5 Cir., 1958, 252 F. 2d 910.

Additionally, as we have recently pointed out, a school segre

gation suit presents more than a claim of invidious discrimination

to individuals by reason of a universal policy of segregation. It

involves a discrimination against a class as a class, and this is

assuredly appropriate for class relief. Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 5 Cir., 1962, 308 F. 2d 491, 499, modified on re

hearing, 308 F. 2d 503. See also Ross v. Dyer, 5 Cir., 1962, 312

F. 2d 191.

18

The record reveals numerous occasions on which appel

lant Anderson and other members of the Albany Move

ment sought in advance of suit, a redress of the grievances

which are the subject matter of the suit by petitioning the

appropriate city officials. Prior to the organization of the

Albany Movement, appellant Anderson met with the appel

lee Mayor of Albany and approached him about the estab

lishment of a biracial committee which would work to affect

peaceful desegregation of all public facilities. But this

approach was unsuccessful, as were subsequent approaches

(R. Vol. V, pp. 102B-103B). After the formation of the

Albany Movement, appellant Anderson and others again

prevailed upon the Mayor to go to the City Commission

and with them seek means of peacefully desegregating the

city’s public facilities (R. Vol. V, p. 103B). On three subse

quent occasions, appellant Anderson and others appeared

before the Mayor and the Commission, requesting, as be

fore, that steps be taken to desegregate the public facilities

of Albany, Georgia (R. Vol. V, pp. 104B-106B, pp. 54B-

60B). These requests were followed by still others (R. Vol.

V, pp. 55B-56B, 83B) until finally appellants were told to

“go to court” (R. Vol. IV, pp. 777A-778A, 781A-783A,

788A).

Appellants, after these numerous requests and petitions,

were not required to do more in order to “make a case.”

As this Court said in Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction

of Dade County, Florida, 246 F. 2d 913 (1957) where the

issue of justiciable controversy was raised because plain

tiffs had not made application for admission to particular

schools :

The issue of justiciable controversy under such a

complaint has been settled in Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, D. C. E. D. La. 1956, 138 F. Supp. 337,

19

340.2 affirmed by this Court in 5 Cir., 1957, 242 F. 2d

156.3

Under the circumstances alleged, it was not necessary

for the plaintiffs to make application for admission to

a particular school. As said by Chief Judge Parker

of the Fourth Circuit in School Board of City of Char

lottesville, Va. v. Allen, 4 Cir. 1956, 240 F. 2d 59, 63,

64:

‘Defendants argue, in this connection, that plain

tiffs have not shown themselves entitled to in

junctive relief because they have not individually

applied for admission to any particular school and

been denied admission. The answer is that in

view of the announced policy of the respective

school boards any such application to a school

other than a segregated school maintained for

2 The district court said :

‘Defendants also move to dismiss on the ground that no

justiciable controversy is presented by the pleadings. This

motion is without merit. The complaint plainly states that

plaintiffs are being deprived of their constitutional rights by

being required by the defendants to attend segregated schools,

and that they have petitioned the defendant Board in vain

to comply with the ruling of the Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, supra. The defendants admit

that they are maintaining segregation in the public schools

under the supervision pursuant to the state statutes and the

article of the Constitution of Louisiana in suit. If this issue

does not present a justiciable controversy, it is difficult to con

ceive of one.’ 138 F. Supp. at page 340.

3 This Court said:

‘Appellees were not seeking specific assignment to particular

schools. They, as Negro students, were seeking an end to a

local school board rule that required segregation of all Negro

students from all white students. As patrons of the Orleans

Parish school system they are undoubtedly entitled to have

the district court pass on their right to seek relief.” 242 F. 2d

at page 162 (246 F. 2d 914).

20

Colored people would have been futile; and equity

does not require the doing of a vain thing as a

condition of relief.’ 240 F. 2d at pages 63, 64.

Cf. Hanes v. Shuttlesworth, 310 F. 2d 303 (1962), affirming

Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord, 202 F. Supp. 59 (N. D. Ala,.

1961). It was just as effective a denial of the constitutional

rights of appellants to have their requests for desegrega

tion repeatedly ignored and rejected as it would have been

had each individual plaintiff, after having made these re

quests, persisted in the futile course of attempting to use

facilities which long-standing official policy and practice

barred to them.

Neither were appellants required, as a prerequisite for

their standing to sue, to expose themselves to arrest for the

attempt to use the facilities in suit. Baldwin v. Morgan, 251

F. 2d 780, 787 (5th Cir., 1958); Evers v. Dwyer, 358 TJ. S.

202 (1958). Indeed, in Evers v. Dwyer, a case involving

the attempt to use public transportation facilities on a

nonsegregated basis, the United States Supreme Court

said that:

. . . We do not believe that appellant, in order to

demonstrate the existence of an ‘actual controversy’

over the validity of the statute here challenged, was

bound to continue to ride the Memphis buses at the

risk of arrest if he refused to seat himself in the space

in such vehicles assigned to colored passengers. A

resident of a municipality who cannot use transporta

tion facilities therein without being subjected by stat

ute to special disabilities necessarily has, we think, a

substantial, immediate, and real interest in the va

lidity of the statute which imposes the disability. (358

U. S. 204)

21

And in the very case relied upon by the court below

Bailey v. Patterson, supra, the United States Supreme

Court while holding that plaintiffs who were not themselves

being prosecuted criminally in the state courts could not

enjoin criminal prosecutions, did hold that these same plain

tiffs, “as passengers using the segregated transportation

facilities . . . are aggrieved parties and have standing to

enforce their rights to nonsegregated treatment,” 369 IT. S.

33 (emphasis supplied), without reference to the occur

rence of specific incidents of segregated treatment or

arrest.

These appellants, therefore, having repeatedly petitioned

city officials, were not bound either to continue to seek to

use the facilities nor to subject themselves to arrest before

instituting suit.

Moreover, the record reveals that appellant Anderson,

notwithstanding the continued rebuffs on the part of appel

lees, did seek to use the swimming facilities located at

Tift Park, but he and the members of his group were denied

admission to the pool (E. Yol. V, pp. 136B-138B). In addi

tion, appellant Anderson has been segregated in the city

auditorium on at least four occasions (R. Vol. V, p. 112B).

Hence, careful examination of the record refutes the dis

trict court’s conclusion that none of the plaintiffs has ever

been denied the use of the facilities in suit (R. Vol. VI, p.

327B). But even were this conclusion correct, appellants,

as individual Negro residents of Albany (Evers v. Dwyer,

supra) and as members of the Albany Movement who had

petitioned city officials many times on behalf of the Negro

residents in Albany to end segregation, would still be

proper persons to bring this suit.

22

II.

R e fu sa l to E n jo in C o n tin u a tio n o f A pp e llees’ P o licy

an d P ra c tice o f E n fo rc e d S eg rega tion in I ts Public-

F ac ilities a n d to E n jo in In te r fe re n c e W ith P e a c e fu l P ro

tes t A gainst T h a t P o licy a n d P ra c tice D en ied A p p e lla n ts ’

C o n stitu tio n a l R igh ts.

There is no question on this record of the continued

existence of Albany’s long standing policy and practice of

enforcing racial segregation in the use of all of the City’s

facilities ostensibly open to the public. Indeed, the record

surges with evidence of the determination on the part of

city officials to maintain at all costs the complete separa

tion of the races in all areas of the City’s public life. For ex

ample, appellee, Asa Kelley, Mayor of Albany, testified that

the Carnegie Library as a matter of “custom and tradition”

was used by the white race “and the other library has been

used by the Negroes” (R. Vol. V, p. 63B); that one of the

City’s parks, Carver Park, was “designed” for members of

the Negro community (R. Yol. V, p. 61B) and that he and

the other white people in Albany would rather see the

swimming pools closed than integrated (R. Vol. V, pp. 64B-

65B). In fact, all the parks in Albany customarily used by

members of the white race only were closed by the police

when Negroes attempted to desegregate Tift Park (R. Yol.

YI, pp. 258B-269B) and have remained closed except for

the zoo and the concession stands (R. Yol. VI, pp. 257B-

258B). The Carnegie Library in the City of Albany was

also closed by the Police Department after an attempt by

Negroes to use it (R. Vol. VI, p. 221B). But, of course,

closing of these facilities does not moot the issue of whether

the unconstitutional policy should be enjoined. City of

Montgomery v. Gilmore, 277 F. 2d 364, 368 (5th Cir. 1960).

23

In addition, at the time of trial the City had many or

dinances on its books which required segregation on the

buses, in the use of taxi cabs and in ticket lines at theaters

(E. Vol. V, pp. 47B-50B, 66B, 70B-71B, PL Exhs. 2 and 3).

There was also evidence of repeated arrests of Negroes

who sought to make use of the City’s public facilities (R.

Vol. V, pp. 110B-111B, 155B-162B; Vol. VI, pp. 199B-211B),

and arrests of Negroes were made in the “white” restaurant

in the Trailways Bus Terminal even after the I.C.C. ruling

of November 1, 1961 (E. Vol. I, pp. 153A-155A, 159A-160A,

162A). Other arrests for alleged violations of the City’s

segregation ordinances also occurred (E. Vol. V, pp. 96B-

102B, 178B-185B).

Thus, the policy of racial segregation in the use of public

facilities is firmly entrenched and systematically pursued;

the resolve on the part of appellee city officials to maintain

that policy unswerving. It was this policy, and the indurate

nature of the resistance by city officials to changing it in

any particular, which finally caused these appellants to in

stitute suit seeking to enjoin its continuation after having

made repeated entreaties to the city officials and having

been told that there were “no areas of agreement” (R. Vol.

V, p. 60B) and that they should “go to court” (R. Vol. IV,

pp. 777A-778A, 781A-783A). In such circumstances it was

plain error for the court below to deny the injunctive relief

requested by appellants since it has long been established

by numerous decisions in the federal courts that appellants,

and the class on whose behalf they sued, are entitled to

the securing of their constitutional rights by way of in

junction against those who would deny them. It has been

established that no ordinance, regulation, policy or prac

tice of a city can require racial segregation in municipally

owned recreational facilities. Dawson v. Mayor of the City

of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 IT. S.

24

877; Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 IT. S. 879 (1955); Tate

v. Department of Conservation and Development, 352 IT. S.

838 (1956); City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830

(5th Cir. 1956). Neither may a city maintain segregation in

the use of its public libraries, Turner v. Randolph, 195 F.

Supp. 677 (W. D. Tenn. 1961); Cobb v. Montgomery Li

brary, 207 F. Supp. 880 (M. D. Ala. 1962). A city owned

auditorium also may not be segregated. Flowers v, City of

Memphis, Civ. No. 3958 (W. D. Tenn., July 11, 1962). Fi

nally, city ordinances which require racial segregation in

public transportation facilities are unconstitutional, Turner

v. City of Memphis, 369 IT. S. 350 (1962); Bailey v. Patter

son, 369 U. S. 31 (1962); Browder v. Gayle, 352 U . S. 903

(1956), affirming 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956). Under

these authorities, the issue of whether a city may maintain

segregation in its public facilities is foreclosed and given

a record such as the one before the court below, injunctive

relief should have followed as a matter of course.

But this suit for injunctive relief succeeded prior efforts

by appellants and others to induce the appellees via peace

ful protest demonstrations and peaceful picketing, to change

their segregation policy and thus obviate the necessity for

protracted litigation. This attempt, of course, was unsuc

cessful, but like the suit for injunctive relief the peaceful

protests were generated by the frustration appellants ex

perienced when they sought redress of their grievances by

petitions and attempted discussions with the city fathers.

Instead, their attempts to proceed by peaceful means were

met with arrests and these appellants were among those

arrested (R. Vol. I, pp. 144A-145A, 146A, 249A; Vol. IY,

pp. 889A-891A; Vol. V, pp. 149B-151B). Hence, the same

motives which compelled appellants to seek relief in the

courts compelled them to engage in peaceful demonstra

tions, i.e., the determination to succeed in their quest for

the vindication of their constitutional right not to be sub-

25

jected to imposed racial segregation. Consequently, appel

lants’ demands for injunctive relief and their engaging in

protest are part and parcel of the same claim of right and

as such appellants are entitled to injunctive relief to pro

tect their right to peacefully protest designed to secure the

unrestricted use of public facilities. Indeed, the right of

peaceful protest is cognate to the complete realization of

appellants’ other constitutional rights and stands on as firm

a ground as those in terms of the constitutional protection

afforded. Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939); Thornhill

v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940); Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296 (1940); Edwards v. South Carolina, ---- -

U. S .----- , 9 L. ed. 2d 697 (1963); Fields v. South Carolina,

----- U. S. -------, 9 L. ed. 2d 965 (1963). It was therefore

equally erroneous for the court below to deny appellants

injunctive relief against interference with their right of

peaceful protest without which, in the circumstances of this

record, appellants’ constitutionally guaranteed rights of un

restricted access to public facilities could not be vindicated.

This was so even though appellants did not specifically pray

for this injunctive relief in the instant suit. But in the

circumstances of this case, particularly in light of the con

solidation of this suit with appellants’ suit to enjoin the

thwarting by arrests and other means, of peaceful protests,

it was entirely appropriate for the court below to grant

this relief herein since the prayer of the complaint in this

action asked for “such other, further, additional or alter

native relief as may appear to a court of equity to be equi

table and just in the premises” (R. Vol. I, p. 11).

Appellants submit that for the court below to have

granted injunctive relief against continued interference

with the right of peaceful protest does no violence to tra

ditional principles of equitable relief since a court of equity

has traditionally granted whatever relief the proof adduced

on trial has mandated. Cases arising in other factual con-

26

texts amply demonstrate that a court may grant the relief

to which parties-plaintiff are entitled without being- limited

by the prayer for relief. For example, Hutches v. Benfroe,

200 F. 2d 337 (5th Cir. 1952) was a case in which this Court

granted to the plaintiff, in a suit on a contract, the differ

ence between the contract price and the resale price of the

subject matter of the suit even though the plaintiff had

only asked for the difference between the contract price

and the market price. This Court declared that, “we are

in no doubt that plaintiff is entitled to the relief to which

the proven facts entitle him, even though his own legal

theory of relief may have been unsound.” 200 F. 2d 340.

Similarly, the Tenth Circuit in Blazer v. Black, 196 F. 2d

139 (1952), in a suit for damages for the fraudulent con

version of stock held that the appellant was entitled to

the equitable relief of an accounting even though this relief

had not been asked for in the prayer of the complaint. That

court said, “[i]t is true that appellant prayed for money

damages, but the legal dimensions of his claim are meas

ured by what he pleaded and proved—not his prayer. The

court was not warranted in dismissing the action unless

upon the facts and law he had shown no right to relief in

law or equity.” 196 F. 2d 147 (emphasis supplied). To the

same effect is Bowles v. J. J. Schmidt and Co., 170 F. 2d

617, 621 (2nd Cir. 1948):

“And as is well known the demand for judgment un

der F. E. C. P. (Kule 54(c)), is not the strictly limiting

factor against an appearing defendant that it may have

been in some past procedures. The one civil action of

the rules has at times been likened to an envelope into

which are dropped all the various claims over which

the parties are at odds.”

Cf., Fireside Marshmallow Co. v. Frank Quinlan Construc

tion Co., 199 F. 2d 511 (8th Cir. 1952).

27

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellants re

spectfully pray that the judgment below be reversed and

the cause remanded with directions to grant injunctive

relief against the continuation of the policy, practice, cus

tom and usage of racial segregation in the use of the public

facilities of Albany, Georgia and against the interference

with appellants’ right of peaceful protest by arrest, harass

ment, intimidation, denial of permits, abuse of court process

or other means.

Respectfully submitted,

C. B. K ing

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

D onald L. H ollowell

Cannolene Building

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

N orman A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

28

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that I have, this 23rd day of May,

1963, served one copy each of the printed Brief for Ap

pellants in the above-styled case on H. G. Bawls, Esq.,

Post Office Box 1496, Albany, Georgia; Eugene Cook, Esq.,

Judicial Building, 40 Capitol Square, Atlanta, Georgia and

E. Freeman Leverett, Esq., Elberton, Georgia, Attorneys

for Appellees, by depositing a true copy of same in the

United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid, addressed

to them at their respective addresses.

Attorney for Appellants