Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education Initial Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 7, 2017

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education Initial Brief of Appellants, 2017. c371b147-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/637aa055-cb04-43fb-82f7-88bd89f6a99a/stout-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-initial-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

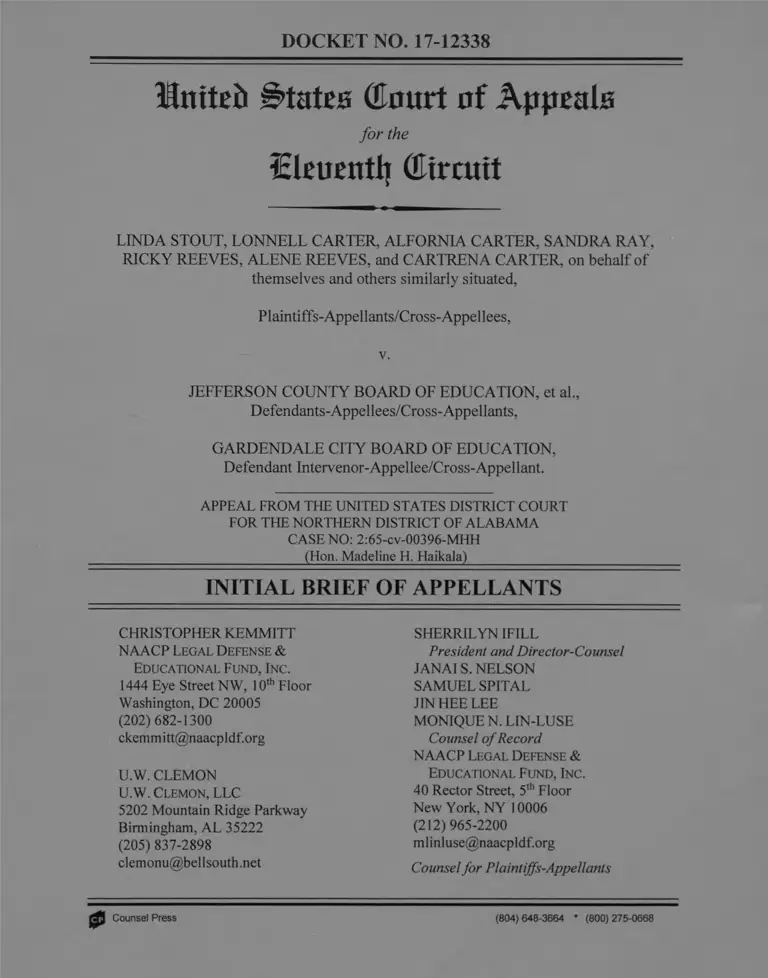

DOCKET NO. 17-12338

IStritcii States (fmtrt of Appeals

for the

jElrucnth (Etrarit

LINDA STOUT, LONNELL CARTER, ALFORNIA CARTER, SANDRA RAY,

RICKY REEVES, ALENE REEVES, and CARTRENA CARTER, on behalf of

themselves and others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees,

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et ah,

Defendants-Appellees/Cross-Appellants,

GARDENDALE CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendant Intervenor-Appellee/Cross-Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

CASE NO: 2:65-cv-00396-MHH

_______________(Hon. Madeline H. Haikala)______________

INITIAL BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

CHRISTOPHER KEMMITT

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund , Inc .

1444 Eye Street NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202)682-1300

ckemmitt@naacpldf.org

U.W. CLEMON

U.W. CLEMON, LLC

5202 Mountain Ridge Parkway

Birmingham, AL 35222

(205)837-2898

clemonu@bellsouth.net

SHERRILYN IFILL

President and Director-Counsel

JANAIS. NELSON

SAMUEL SPITAL

JINHEE LEE

MONIQUE N.LIN-LUSE

Counsel o f Record

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc .

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

mlinluse@naacpldf.org

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Counsel Press (804)648-3664 * (800)275-0668

mailto:ckemmitt@naacpldf.org

mailto:clemonu@bellsouth.net

mailto:mlinluse@naacpldf.org

Linda Stout, et al. v. Jefferson County School Board, No. 17-12338

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND CORPORATE

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Plaintiffs-Appellants/Cross-Appellees Linda Stout, Lonnell and Alfomia

Carter, Sandra Ray, Alene and Ricky Reeves, and Cartrena Carter (“Plaintiffs-

Appellants”) make the following disclosures of interested parties pursuant to

Eleventh Circuit Rule 26.1:

1. The Hon. Madeline H. Haikala, United States District Judge, Northern

District of Alabama

2. Alfomia Carter, Plaintiff-Appellant

3. Cartrena Carter, Plaintiff-Appellant

4. Lonnell Carter, Plaintiff-Appellant

5. Sandra Ray, Plaintiff-Appellant

6. Alene Reeves, Plaintiff-Appellant

7. Ricky Reeves, Plaintiff-Appellant

8. Parents of all African American students currently enrolled, or who will be

enrolled, in the public schools operated by the Jefferson County (Alabama)

Board of Education

9. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”)

10. Sherrilyn Hill, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

11. Janai Nelson, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

12. Jin Hee Lee, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Page C-l of 4

13. Monique N. Lin-Luse, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

14. Christopher Kemmitt, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

15. Deuel Ross, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

16. Samuel Spital, LDF Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

17. U.W. demon, LDF Cooperating Local Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

18. U.W. Clemon, LLC, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

19. White Arnold & Dowd P.C., former law firm associated with U.W.

Clemon, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

20. Jefferson County Board of Education (“JCBOE”), Defendant-

Appellee/Cross-Appellant

21. Jacqueline A. Smith, JCBOE Member

22. Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, JCBOE Member

23. Ronnie Dixon, JCBOE Member

24. Oscar S. Mann, JCBOE Member

25. Donna J. Pike, JCBOE Member

26. Dr. Warren Craig Pouncey, Superintendent, JCBOE

27. Whit Colvin, Attorney for JCBOE

28. Andrew Ethan Rudloff, Attorney for JCBOE

29. Carl E. Johnson, Jr, Attorney for JCBOE

30. Bishop, Colvin, Johnson, and Kent, LLC, Counsel for JCBOE

Page C-2 of 4

Linda Stout, et al. v. Jefferson County School Board, No. 17-12338

31. Gardendale City Board of Education (“GBOE”), Defendant-Intervenor/

Cross-Appellant

32. Dr. Michael Hogue, GBOE Member

33. Richard Lee, GBOE Member

34. Christopher Lucas, GBOE Member

35. Adams and Reese, LLP, Counsel for GBOE

36. Dr. Patrick Martin, Superintendent, GBOE

37. Stephen A. Rowe, Attorney for GBOE

38. Russell J. Rutherford, Attorney for GBOE

39. Christopher Gamble, Mount Olive resident

40. Aaron G. McLeod, Attorney for GBOE

41. Giles G. Perkins, Attorney for GBOE

42. United States of America, Plaintiff-Intervenor

43. Kelly Gardner, Attorney, United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights

Division (“DOJ”)

44. Veronica R. Percia, Attorney, DOJ

45. Natane Singleton, Attorney, DOJ

46. Shaheena A. Simons, Attorney, DOJ

47. Sharon D. Kelly, Assistant United States Attorney, Northern District of

Alabama

Linda Stout, et al. v. Jefferson County School Board, No. 17-12338

Page C-3 of 4

Linda Stout, et al. v. Jefferson County School Board, No. 17-12338

48. City of Graysville, Alabama

49. Andrew P. Campbell, Attorney for Graysville

50. John C. Guin, Attorney for Graysville

51. Yawanna Neighbors McDonald, Attorney for Graysville

52. Campbell, Guin, Williams, Guy, and Gidiere LLC, Counsel for Graysville

53. Town of Brookside, Alabama

54. K. Mark Parnell, Attorney, Town of Brookside

55. Parnell Thompson, LLC, Counsel for Town of Brookside

56. Mary H. Thompson, Attorney for Town of Brookside

57. Roger McCondichie, Brookside resident

58. Dale McGuire, Brookside resident

We certify that no publicly traded company or corporation has an interest in

the outcome of this case either in the District Court or in this Court.

Page C-4 of 4

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs-Appellants, pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure

34 and Eleventh Circuit Rule 34(3)(c), respectfully request oral argument.

This case presents important constitutional issues related to the effectuation

of school desegregation orders. Oral argument will assist this Court to

analyze the complex record and to resolve these important legal issues.

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND CORPORATE

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT................................................................... C-l

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT..................................... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................ ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................................................................... iii

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION................................................................1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES.................................................................... 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE....................................................................... 4

I. Procedural History.................................................................................6

II. The Trial Evidence and the Court’s Factual Findings.........................11

A. The Evidence of Gardendale’s Discriminatory Intent in Seeking

to Secede from the Jefferson County School District to Create a

Significantly Whiter School System.........................................12

B. Gardendale’s Failure to Carry Its Burden Under Established

Precedent as to the Effect of Its Secession on Desegregation

Efforts in Jefferson County...................................................... 20

III. The District Court’s Orders Permitting Gardendale to Secede from

Jefferson County................................................................................. 24

IV. Standard of Review............................................................................ 26

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT........................................................... 27

ARGUMENT.................................................................................................29

I. Recognition of the Gardendale School District Is Foreclosed by

Binding Precedent and by the Law of the Case.................................. 29

ii

A. Controlling Law Prohibits District Courts from Approving a

Splinter District if the District Cannot Prove that Its Secession

Would Not Undermine Desegregation Efforts in the Parent

District........................................................................................31

B. The District Court Erred by Concluding that Stout I Is No

Longer Good Law......................................................................36

C. The “Practical Considerations” Identified by the District Court

Do Not Support Its Remedial Order......................................... 42

II. The District Court’s Finding of Intentional Discrimination Constitutes

an Additional Basis for Denying Gardendale’s Request to Secede from

Jefferson County.................................................................................. 50

CONCLUSION..............................................................................................54

Certificate of Compliance............................................................................ 55

Certificate of Service....................................................................................56

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE(S)

CASES

Alikhani v. United States,

200 F.3d 732 (11th Cir. 2000)................................................................ 27, 31, 50

Bonner v. City o f Prichard,

661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir. 1981).......................................................................... 34

*Brown v. Board o f Education,

341 U.S. 483 (1954).......................................................................................6, 44

Calhoun v. Bd. ofEduc. o f Atlanta,

188 F. Supp. 401 (N.D. Ga. 1959)..................................................................... 49

*City o f Richmond v. United States,

422 U.S. 358 (1975)..................................................................................... 28,51

Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958)................................................................................................ 49

In re Bayshore Ford Truck Sales, Inc.,

471 F.3d 1233 (11th Cir. 2006)............................................................................ 2

In re Hubbard,

803 F.3d 1298 (11th Cir. 2015)............................................................... 39-40, 40

Fla. League o f P ro f l Lobbyists, Inc. v. Meggs,

87 F.3d 457 (11th Cir. 1996)................................................................................30

Green v. Cty. Sch. Bd. o f New Kent,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)........................................................................................52-53

Griffin v. School Bd. o f Prince Edward Cty.,

377 U.S. 218(1964)...............................................................................................6

Lee v. Chambers Cty. Bd. ofEduc.,

849 F. Supp. 1474 (M .D. Al. 1994)................................................................... 50

IV

PAGE(S)

*Lee v. Macon Cty. Bd. ofEduc.,

448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971)........................................................................passim

Main Drug, Inc. v. Aetna U.S. Healthcare, Inc.,

475 F.3d 1228 (11th Cir. 2007)............................................................................. 40

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717(1974)............................................................................................ 52

Milliken v. Bradley,

433 U.S. 267 (1977)............................................................................................ 52

Monroe v. Bd. o f Comm ’rs o f Jackson,

391 U.S. 450(1968)............................................................................................. 33

N. C. State Bd. o f Educ. v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971)................................................................................. 6-7,31,32

*Ross v. Houston Indep. Sch. Dist.,

583 F.2d 712 (5th Cir. 1978)........................................................................passim

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Separate Sch. Dist.,

419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969)...............................................................................8

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Cty. Bd. o f Educ.,

888 F.2d 82 (11th Cir. 1989)...............................................................................27

*Stout v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. ofEduc.,

448 F.2d 403 (5th Cir. 1971)..........................................................................passim

* Stout v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. o f Educ.,

466 F.2d 1213 (5th Cir. 1972).................................................................... passim

This That & the Other Gift & Tobacco, Inc. v. Cobb County,

439 F.3d 1275 (11th Cir. 2006)...........................................................................41

United States v. Alabama,

828 F.2d 1532 (11th Cir. 1987).............................................................................2

United States v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. ofEduc.,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966).................................................................................7

v

United States v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. o f Educ.,

417 F.2d 834 (5th Cir. 1969)..............................................................................7-8

United States v. Scotland Neck Bd. o f Educ.,

407 U.S. 484(1972)............................................................................................. 49

United States v. Tex. Educ. Agency,

579 F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1978)...............................................................................47

United States v. Virginia,

518 U.S. 515 (1996)...................................................................................... 52, 53

United States v. Whatley,

719 F.3d 1206 (11th Cir. 2013).................................................................... 27, 50

Westbrook v. Zant,

743 F.2d 764 (11th Cir. 1984)..............................................................................41

* Wright v. Council o f Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972)..................................................................................... passim

Wright v. Sch. Bd. o f Greensville Cty.,

309 F. Supp. 671 (E.D. Va. 1970)...................................................................... 33

PAGE(S)

STATUTES & RULES

28 U.S.C.

§ 1291................................................................................................................. 1,2

§ 1292......................................................................................................................1

§ 1331......................................................................................................................1

Ala. Code § 16-8-20.................................................................................................22

Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)(1)..............................................................................................3

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a)(6)...........................................................................................27

PAGE(S)

vi

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This appeal arises out of a case originally filed in 1965 by Plaintiffs-

Appellants (also known as the Stout Plaintiffs), who represent the class of parents

of Black schoolchildren in Jefferson County, Alabama. The suit resulted in a

permanent injunction, which barred the Jefferson County Board of Education from

operating a racially-segregated school system, and required the development,

implementation, and continued court supervision of a plan to desegregate Jefferson

County’s schools. See Doc. 2 (“Complaint”); Doc. 3 (“Mot. for Prelim. Inj.”);

Doc. 5 (“Order.”)1 In 2015, Gardendale, a city in Jefferson County, intervened as a

defendant and filed a motion to create a new school system separate from the

Jefferson County Board of Education. See Doc. 1002 (“Mot. for Intervention”);

Doc. 1040, Doc. 1040-1 (“Mot. to Separate”) and (“Prop. Separation Agreement”).

The District Court had jurisdiction over both the original case and Gardendale’s

motion under 28 U.S.C. § 1331.

The District Court granted in part, and denied in part, Gardendale’s motion.

As explained more fully in Plaintiffs-Appellants’ Response to the Clerk’s

Jurisdictional Questions, dated July 5, 2017, this Court has jurisdiction to review

the District Court’s ruling under both 28 U.S.C. § 1291 and 28 U.S.C. § 1292. In

1 References to the District Court record are by docket entry (“Doc.”)

followed by the relevant docket entry number.

1

the school desegregation context, this Court considers the “indicia of finality” in a

district court opinion to determine whether it is an appealable, final judgment

under 28 U.S.C. § 1291. United States v. Alabama, 828 F.2d 1532, 1537 (11th Cir.

1987). District court opinions are “for all practical purposes a final order” when

they are thorough in “specificity, detail, and comprehensiveness,” and when “the

District Court gives detailed instructions in every area.” Id. That standard is

satisfied here because the District Court approved the creation of an entirely new

school system that encompassed new zoning lines for certain schools, and required

the parties to create a facilities plan for additional schools with comprehensive and

detailed directions for what should be included in that plan. Doc. 1141 (“Mem.

Op. & Order”) at 185-190.

This Court also has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1), because

the District Court issued an order “granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or

dissolving [an] injunction^, or refusing to modify [an] injunction[].” See In re

Bayshore Ford Truck Sales, Inc., 471 F.3d 1233, 1260 (11th Cir. 2006).

Specifically, the District Court granted in part Gardendale’s request to create a

splinter district, which in effect denied Plaintiffs-Appellants’ request for an order

enjoining the creation of the new district. See Doc. 1141 at 185. Alternatively, the

District Court’s opinion can be understood as “continuing, modifying, refusing to

2

dissolvfe] . . . or refusing to . . . modify” the prior injunction that had been issued

in this case governing Jefferson County’s schools. 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1).

The District Court issued its Memorandum Opinion and Order on April 24,

2017, and, in response to a timely motion to alter or amend the judgment, it issued

its Supplemental Memorandum Opinion on May 9, 2017. Doc. 1141; Doc. 1152

(“Suppl. Mem. Op.”). Plaintiffs-Appellants filed a timely notice of appeal on May

22, 2017. See Doc. 1160 (“Notice of Appeal”); Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)(1). On

August 2, 2017, this Court’s clerk noted that this Court has probable jurisdiction to

hear this case after issuing a Jurisdiction Question to the parties.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

(1) Wright v. Council o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 470 (1972), holds “that a

new school district may not be created where its effect would be to impede the

process of dismantling a dual system.” Did the District Court commit legal error

by permitting the Gardendale Board of Education to operate a new school district

despite making a factual finding that creation of a new Gardendale school district

would impede desegregation efforts of the Jefferson County Board of Education?

(2) The District Court further found that Gardendale was motivated by

intentional racial discrimination—specifically, the desire to exclude Black

3

schoolchildren—in creating a new district. Did the District Court err in approving

the formation of a new Gardendale school system despite that factual finding?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The City of Gardendale is a small, predominantly white municipality in

Jefferson County, Alabama. In 2015, Gardendale sought to prevent the racial

integration of its schools by seceding from the Jefferson County School District

(“JCSD”). After a bench trial, the District Court expressly found that Gardendale’s

secession effort was motivated by intentional racial discrimination, and that its

request to operate a new school district would undermine desegregation efforts in

Jefferson County. The District Court’s factual findings are unassailable. Under

controlling precedent, they permit of only one result: an order prohibiting

Gardendale’s secession. Yet, the District Court misinterpreted that precedent. As

a result, even though the District Court recognized that Gardendale’s secession was

motivated by the intent to circumvent an existing desegregation order and exclude

Black children from Gardendale’s schools, the court permitted Gardendale to

secede.

The Jefferson County School District is operated by the Jefferson County

Board of Education (“JCBOE”). JCBOE runs 56 schools, including four public

schools located within Gardendale’s city limits. JCSD, which is 47.5% Black and

43.5% white, is governed by a long-standing desegregation decree. Over the

4

previous two decades, the racial demographics of Jefferson County have shifted,

leaving the county school system with a lower percentage of white students.

Majority-white municipalities with separate school systems have been largely

impervious to the county’s changing demographics, however, remaining

segregated while the African American population in other areas of Jefferson

County has increased. See, e.g., Doc. 1131-6 at 12 (“Decl. of William S. Cooper”).

Some Gardendale residents are concerned about the significant increase in the

proportion of Black students in the Jefferson County School District; they fear that

Gardendale might become a predominantly Black city. Doc. 1141 at 138. As the

District Court explained, “[tjhese citizens prefer a predominantly white city.” Id.

Motivated by a desire to avoid further integration of Gardendale’s public

schools and the city itself, Gardendale residents launched an effort to secede from

JCSD and create an independent municipal school system. Gardendale’s secession

was opposed by Plaintiff-Appellants, the United States Department of Justice

(“DOJ”), the Jefferson County Board of Education, and multiple Plaintiff-

Intervenors.

Following a five-day bench trial, the District Court found that:

(1) Gardendale failed to carry its burden of showing that its secession would not

impede desegregation efforts in Jefferson County, and (2) Gardendale’s secession

was motivated by intentional racial discrimination. Notwithstanding these

5

findings, the District Court granted in part Gardendale’s motion to operate a

separate school system. Specifically, the court permitted Gardendale to operate a

new school system comprised of the two elementary schools within its municipal

boundaries. The court ordered that the middle school and high school in

Gardendale remain JCBOE schools, while allowing Gardendale to file a renewed

motion to operate those schools after three years. The decision to permit

Gardendale to secede from the Jefferson County School District is the subject of

the instant appeal.

I. Procedural History

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954), ruling that “[sjeparate educational facilities are inherently

unequal” and deprive Black schoolchildren “of the equal protection of the laws

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.” M a t 495. Despite Brown,

segregation persisted. School boards ignored the ruling, made half-hearted,

ineffectual attempts to comply, or defied outright the Court’s edict. State and local

governments employed an array of stratagems to avoid desegregation. See, e.g.

Griffin v. School Bd. o f Prince Edward Cty., 377 U.S. 218 (1964) (holding that

county school board’s actions were unconstitutional where county responded to

Brown by closing public schools and supporting private, white-segregated

schools); N.C. State Bd. ofEduc. v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971) (ruling that a North

6

Carolina anti-busing statute that impeded desegregation was unconstitutional).

One of these stratagems was the secession of mostly-white towns from larger and

more diverse county school systems to avoid racial integration. See Wright v.

Council o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972) (prohibiting municipal secession from

county school district following enactment of countywide desegregation decree).

Jefferson County was not an outlier in this regard.

Plaintiffs-Appellants sued JCBOE on June 4, 1965 because it continued to

operate a segregated school system eleven years after Brown. On June 24 of that

year, the District Court found that JCBOE was operating a segregated school

system and ordered it to desegregate. See Doc. 5.2 Shortly thereafter, the United

States, through the Department of Justice, intervened as a plaintiff. See Doc. 8

(“Mot. of United States to Intervene”). Between 1965 and 1968, the JCBOE

utilized a “freedom of choice” desegregation plan. Doc. 1141 at 12; United States

v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. ofEduc., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966). Plaintiffs-Appellants

challenged the “freedom of choice” plan, and the Fifth Circuit ordered a zoning-

based desegregation plan for the first time in United States v. Jefferson County

2 The electronic docket does not include the vast majority of early docket

entries. Plaintiffs-Appellants have attached the paper docket as part of the

Appendix. Some entries, like the docket entry above, are not clearly numbered in

the paper docket. In these circumstances, Plaintiffs-Appellants have identified the

entries by date and attempted, to the best of their ability, to discern the correct

docket number.

7

Board o f Education, 417 F.2d 834, 836 (5th Cir. 1969). Later that year, this case

was consolidated with twelve other desegregation cases throughout the six states

which comprised the Fifth Circuit, sub nom, Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 419 F.2d 1211,1219 (5th Cir. 1969). Pursuant to the

mid-school year mandate of Singleton, the District Court entered its comprehensive

^ Singleton"’’ desegregation order on February 2, 1970. See Doc. 131 (“Order”).

Between February and July of 1970, three all-white cities—Pleasant Grove,

Vestavia Hills, and Midfield—and the predominately-white city of Homewood

withdrew from the Jefferson County School District and formed separate

municipal school districts. Plaintiffs-Appellants challenged these secessions, and

in response, the Fifth Circuit ordered the District Court to “implement a student

assignment plan” that included both JCBOE and each of the municipal school

districts that had separated from the county. The District Court issued its order on

September 8, 1971. See Doc. 226 (“1971 Order”). The 1971 Order set forth a

comprehensive desegregation plan, which remains the primary operative order in

this case.

One of the separating school districts, the City of Pleasant Grove, refused to

comply with the 1971 Order’s requirement to purchase buses for the transportation

of Black students. As a result, the District Court enjoined operation of the Pleasant

Grove school district, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed that decision. Stout v.

8

Jefferson Cty. Bd. ofEduc., 466 F.2d 1213 (5th Cir. 1972). As the Fifth Circuit

explained, “‘where the formulation of splinter school districts . . . have the effect of

thwarting the implementation of a unitary school system, the District Court may

no t. . . recognize their creation.’” Id. at 1214 (citation omitted).

In the period since Pleasant Grove’s court-ordered dissolution, three more

municipalities—each with predominantly white residents—have seceded from the

Jefferson County school system. These separations have “contributed to

significant demographic shifts in Jefferson County.” Doc. 1141 at 66. Gardendale

now aspires to be the fourth municipality to secede since the 1971 Order. On

March 3, 2014, the Gardendale City Council established a municipal school

system, headed by a new Gardendale Board of Education (“GBOE”). GBOE

moved to intervene in this case on March 13, 2015, following an abortive attempt

to evade federal review by filing a state court lawsuit.3 Id. at 107. On December

11, 2015, Gardendale filed a motion to operate a municipal school system and a

proposed plan of separation. Id. at 115.

3 Although binding Circuit authority required Gardendale to prove to the

District Court that its separation would have a “lack of deleterious effects on

desegregation” in Jefferson County, see Ross v. Houston Indep. Sch. Dist., 583

F.2d 712, 714 (5th Cir. 1978), Gardendale first filed a lawsuit in state court to force

Jefferson County to relinquish control over the public schools located within

Gardendale’s city limits. Doc. 1141 at 107. The District Court enjoined the state

court suit after Gardendale moved to intervene in this case. See id.

9

Pursuant to Gardendale’s proposal, GBOE would create an independent

school system and assume control of the four JCBOE schools located within

Gardendale’s municipal boundaries: Snow Rogers Elementary, Gardendale

Elementary, Bragg Middle School, and Gardendale High School. The high school

is a $51 million, state-of-the-art facility that was built by JCBOE in 2010 for the

education of students in and around Gardendale.4 Id. at 69. According to

Gardendale’s proposal, GBOE would receive each of these schools free of charge.

The plan would also change the Gardendale school attendance zones. At

present, the four schools in Gardendale educate students from Gardendale, the

towns of Brookside and Graysville, and the unincorporated areas of North

Smithfield Manor-Greenleaf Heights (“North Smithfield”) and Mount Olive.

Under Gardendale’s proposal, the school attendance lines would be re-drawn at the

municipal boundaries. Students from outside the city limits would be phased out

over a thirteen-year period with the exception of students from North Smithfield,

who would be permitted to stay for the “indefinite future.” Id. at 128.

Gardendale’s motion to operate a separate municipal school system was

opposed by Plaintiffs-Appellants, DOJ, and JCBOE. Additionally, the City of

4 The District Court noted that “[t]he new Gardendale High School is

appropriately regarded as one of Jefferson County’s desegregatory tools.” Doc.

1141 at 171.

1 0

Graysville, the Town of Brookside, and two parents from the unincorporated

community of Mount Olive moved for limited intervention in order to oppose

Gardendale’s separation. Id. at 133. To resolve the dispute, the District Court held

a bench trial on December 1-2 and 7-9, 2016. Id. at 137.

II. The Trial Evidence and the Court’s Factual Findings

The trial evidence adduced by the parties focused on two issues: (1) whether

GBOE’s creation and operation were motivated by the intent to exclude Black

schoolchildren from Gardendale schools, and (2) whether Gardendale could satisfy

its legal burden to prove that its separation would not impede Jefferson County’s

desegregation efforts.

The court answered the first question in the affirmative: “[T]he Court finds

that race was a motivating factor in Gardendale’s decision to separate from the

Jefferson County public school system.” Doc. 1141 at 138. Specifically, “[t]he

record demonstrates that the Gardendale Board is trying to evade the Court’s

desegregation order because some citizens in Gardendale want to eliminate from

Gardendale schools the black students whom Jefferson County transports to

schools in Gardendale.” Id. at 151.

The court answered the second factual question in the negative, finding that

“Gardendale has not demonstrated that its separation will not impede Jefferson

11

County’s effort to . . . eliminate the vestiges of past discrimination to the extent

practicable.” Id. at 162.

A. The Evidence of Gardendale’s Discriminatory Intent in Seeking to

Secede from the Jefferson County School District to Create a

Significantly Whiter School System

The record amply supported the District Court’s factual finding that GBOE’s

desire to exclude Black children from Gardendale schools motivated its motion to

separate from Jefferson County. At the time of Gardendale’s separation efforts,

Jefferson County’s schools were in the midst of a significant demographic change.

In 2000, the county school system was 75.6% white and 23.0% Black. Doc. 1141

at 67. In 2015, following a pair of municipal separations and the repeated

annexation of majority-white areas by majority-white municipalities that were not

part of the Jefferson County school system, the county schools were 43.4% white

and 47.3% Black. Id. The demographics of Gardendale’s student population has

followed a similar but more gradual trajectory. Twenty years ago, the student

population within Gardendale’s city limits was 92% white and 8% Black; today

20% of the student population is Black. Id. at 92. The City of Gardendale,

however, remains 88.4% white. Id. at 74. Gardendale’s schools have a higher

percentage of Black students than the percentage of Black residents in the

municipality because of the 1971 Order. That desegregation order provides for the

busing of students from the mostly-Black North Smithfield community to

1 2

Gardendale’s schools and also permits some students from majority-Black schools

in Jefferson County to transfer to Gardendale’s schools.

As the District Court found, “some Gardendale citizens are concerned

because the racial demographics in Gardendale are shifting, and they worry that

Gardendale, like its neighbor Center Point, may become a predominantly black

city. These citizens prefer a predominantly white city.” Id. at 138. The

Gardendale citizens referenced by the District Court include key individuals

responsible for organizing the separation effort, two of whom became inaugural

members of the Gardendale Board of Education. Doc. 1124 at 168:17-169:3,

183:17-184:15 (“Dec. 1, 2016 Trial Tr.”); Doc. 1131-35 at 19:2-13, 104:10-

107:14, 110:11-20 (“Joint Trial Ex. 20, Mar. 16, 2016 Chris Segroves Dep. Tr.”).

In particular, organizers of the separation effort made clear their concern that

Gardendale’s schools did not reflect the overwhelmingly white character of the

city. As one organizer commented before the separation, “A look at our

community sporting events, our churches are great snapshots of the community. A

look into our schools, and you’ll see something totally different.” Doc. 1141 at

140. Another organizer explained that creating a separate school system would

provide “better control over the geographic composition of the student body.” Id.

at 177.

13

On another occasion, a separation organizer noted: “It likely will not turn out

well for Gardendale if we don’t do this. We don’t want to become what [Center

Point] has.” Id. at 88. Community members repeatedly echoed these sentiments

on a public Facebook page created for the purpose of supporting the separation

effort. See, e.g., id. at 141 (“did you know we are sending buses to Center point

[s/c] and busing kids to OUR schools in Gardendale as well as from [North

Smithfield]!”); see also id. at 80-89, 128, 137.

The goals of Gardendale’s separation were vividly illustrated by a flyer

disseminated in the community during the separation effort. Id. at 93; see also

Doc. 1132-13 (“Pis.’ Trial Ex. 11, Gardendale Advertisement”). The flyer depicts

a white elementary school student and asks, “What path will Gardendale choose?”

Doc. 1141 at 94. Two choices are provided. The top of the flyer lists several well-

integrated or predominantly Black municipalities that have not formed municipal

school systems. The bottom lists cities that “chose to form and support their own

school system.” Id. at 95. Each of these cities have school systems that are

predominantly white and have been since 1970. The flyer characterizes them as

“some of the best places to live in the country.” Id. A Black resident of North

Smithfield explained the message of the flyer as follows: “[i]f you do not want the

undesirables and problem children, you best be forming your own [school]

system.” Id.

14

The racial motivation underlying Gardendale’s separation effort is

confirmed by the fact that organizers initially proposed excluding surrounding

communities that are predominately Black from the new school district, but

including Mt. Olive, which is 97% white. Id. at 81, 164. Indeed, when Gardendale

commissioned a feasibility study for a public-school system in the city, the author

included Mount Olive students in the study but not students from any other

community.5 Id. at 92.

State Senator Scott Beason was also a leader in the effort to create a separate

school system for Gardendale. Named Plaintiff Sandra Ray testified that, having

heard news reports that Senator Beason referred to African Americans as

“aborigines,” she had serious concerns about his involvement in the Gardendale

school system. Doc. 1128 at 1270:20-1271:17. (“Dec. 9, 2016 Trial Tr.”). The

organizers of the separation effort succeeded, and on March 3, 2014, the

Gardendale City Council adopted an ordinance that created the Gardendale City

School System.

5 Although separation organizers spoke to State Senator Scott Beason, who

was prepared to sponsor legislation that would annex Mount Olive into

Gardendale, practical obstacles related to the local fire district have impeded

Gardendale from including Mt. Olive in its separation plan. Doc. 1131-47 at 48-51

(“Joint Trial Ex. 24, Mar. 18, 2016 Scott Beason Dep. Tr.”).

15

The actions of this new school district have reflected the same racial

discrimination that motivated its creation. In early 2014, the Gardendale City

Council solicited applicants for the Board of Education and selected five members,

each of whom is white and two of whom were lead separation organizers. Doc.

1141 at 98. In so doing, the Board passed over a highly qualified Black applicant,

Dr. Sharon Porterfield Miller, even though she had more educational experience

than all but one member chosen for the Board. Id. at 99. Dr. Miller testified at

trial that she believed that race was a factor in Gardendale’s decision not to select

her. Id. at 100.

When Gardendale first drafted a separation plan in March 2015, it excluded

the majority-Black North Smithfield community that had attended Gardendale

schools since 1971. Id. at 115. In a volte-face, Gardendale included North

Smithfield in the separation plan that it presented to the District Court in December

2015. Id. at 116. The change was motivated by the 1971 Order in this case, which

Gardendale understood to require that a separating school district meet a certain

ratio of student enrollment by race. Id. at 123. Without the Black students from

North Smithfield, Gardendale could not meet that ratio. Id. at 123-24. Yet,

GBOE’s superintendent—who had never worked with a Black teacher and had

never hired a Black teacher or administrator in his seventeen-year career in

education—did not even consult with the North Smithfield community before

16

proposing their inclusion in the new Gardendale district. Id. at 101 n.52, 121. He

failed to do so even though North Smithfield’s residents would be deprived of a

voice on their local school board, and its students would be forced to attend a

different elementary school. Id. at 122.

When North Smithfield’s inclusion in the proposed school district became

public, members of the Gardendale community voiced their displeasure to the

superintendent and on the Facebook page created by proponents of the separation.

Id. at 128. One of the separation organizers defended the move to unhappy

residents, explaining that “[t]his has the hallmarks of a specific, technical, tactical

decision aimed at addressing a recognized roadblock to breaking away.” Id. at

130. But he characterized the inclusion of North Smithfield students as a “bitter

. . . pill to swallow,” and he acknowledged that Gardendale residents would differ

in their opinions as to whether it was too bitter to justify the ultimate goal of

separation. Id. at 131. Another organizer “described the inclusion of the children

from North Smithfield as ‘the price’ Gardendale had ‘to pay to gain approval for

separation.’” Id. at 176.

The Gardendale Board’s intent to exclude Black students is also reflected in

its actions and inactions regarding policies that would affect the racial composition

of an independent Gardendale school district. At the end of 2014, the GBOE

superintendent drafted an inter-district transfer policy that included numerous

17

provisions, only one of which addressed racial desegregation transfers. Id. at 143.

The president of GBOE singled out the racial desegregation transfer provision for

review by the district’s legal team to determine its “applicability/appropriateness

for GBOE.” Id. at 144. Subsequent drafts of the racial desegregation transfer

provision added caveats “designed to minimize or eliminate racial desegregation

transfers.” Id. By the time of trial, GBOE had failed to vote on a transfer policy

despite binding court precedent requiring that it do so. Id. at 144-45. As a result,

the GBOE superintendent was unable to say which of the many draft inter-district

transfer policies might be implemented by the Board. Id. at 145. The District

Court explained that “[t]his official action—or lack thereof—dovetails with the

separation organizers’ expressed interest in eliminating from the schools within

Gardendale’s municipal limits students who are bussed into Gardendale from other

areas of Jefferson County.” Id.

GBOE adopted a similarly evasive approach toward its inclusion of the

North Smithfield community in the separation plan. According to the December

2015 separation plan, North Smithfield students “will be able to attend Gardendale

schools for the indefinite future.” Id. at 149. But no GBOE representative ever

explained the meaning of the term “indefinite future” to the North Smithfield

community. Id. at 150. At trial, the superintendent and a member of GBOE

testified that, in their understanding, the phrase meant that North Smithfield

18

students could attend Gardendale schools so long as their tax dollars flow to the

Gardendale school system. Id. However, the desegregation order in this case

provides the sole mechanism by which tax dollars from North Smithfield can flow

to Gardendale. Thus, if Gardendale is released from the desegregation order—a

position for which its counsel advocated below, see, e.g., Doc. 1090; Doc. 1104;

—students from North Smithfield have no assurance that they will continue to

attend the schools that they have attended for nearly five decades. See Doc. 1141

at 150.

Furthermore, GBOE has never voted on the separation plan that includes

North Smithfield students despite the fact that Gardendale’s counsel submitted it to

the District Court. Id. at 149. As the District Court explained:

Rather than make a commitment to the students in North Smithfield,

the Gardendale Board has been waiting to see whether its attorneys

could persuade the Court that the 1971 desegregation order does not

govern Gardendale’s separation. If Gardendale does not need the

students from North Smithfield to separate, then the Board has no

incentive to keep those students in the Gardendale system.

Id. at 149-50. By delaying a vote, GBOE has “allowed itself the flexibility” to

change its separation plan and exclude the predominantly Black students from

North Smithfield. Id. at 150.

In sum, the District Court found that GBOE was created for, and operated

with, the goal of excluding Black children from the school district. As such, the

District Court found that Gardendale’s separation from Jefferson County

19

constituted an independent constitutional violation under the Fourteenth

Amendment. Id. at 180.

B. Gardendale’s Failure to Carry Its Burden Under Established

Precedent as to the Effect of Its Secession on Desegregation

Efforts in Jefferson County

Even absent the compelling evidence of intentional discrimination described

above, the District Court could not grant GBOE’s separation motion unless it made

the “essentially factual determination” that Gardendale’s separation would not

impede JCBOE’s desegregation efforts. Wright, 407 U.S. at 470; see Doc. 1141 at

150-80. As the party petitioning to separate, GBOE bore the burden of proof on

this issue. See id. at 162. “Consistent with Wright, to determine whether

Gardendale has carried its burden,” the District Court examined three factors:

“anticipated post-separation racial demographics, facilities and the programs

available in those facilities, and the message that Gardendale’s proposed separation

sends to African-American students who have attended schools in the Gardendale

zone pursuant to this Court’s desegregation order.” Id. at 163. As the court

determined, each of these factors weighed against granting Gardendale’s motion to

separate. See id. at 162-80.

First, the court determined that Gardendale’s separation would have a

negative impact on the post-separation racial demographics of Jefferson County

and would inflict a series of related, collateral consequences on the county. Id. at

20

162-63. If Gardendale separated, JCSD’s student population would immediately

become 1.5%-1.8% more Black. Id. at 165. Further as the District Court found,

this initial impact understates the demographic consequences of the separation

because every previous splinter district from Jefferson County subsequently

annexed additional white communities. Id. at 166. “[T]hese separations and

annexations have altered the racial composition of the Jefferson County student

population continually since 2000.” Id. Because the districts that have seceded

and the areas they have annexed tend to be affluent and “produce significant tax

income” for the county, the process of secessions and annexations “has repeatedly

shifted the geographic, demographic, and economic characteristics of Jefferson

County.” Id. These changes significantly complicate JCBOE’s efforts to plan and

to comply with its desegregation obligations. Id. at 166-67. And, consistent with

previous school districts that have seceded, Gardendale has already evinced an

interest in annexing Mount Olive and other predominantly white communities

north of the municipal limits. Id.

GBOE’s separation would also cause the JCSD students who are removed

from the proposed Gardendale zone to leave their modestly desegregated schools

in Gardendale and attend schools that are “extremely segregated.” Id. The burden

of this move would fall most heavily on Black students. Id. The separation would

2 1

also harm the Black students who currently attend Gardendale schools as

desegregation transfers but would be excluded under GBOE’s separation plan. Id.

Second, the court determined that the loss of programs and facilities

attendant to Gardendale’s separation would have an adverse effect on JCBOE’s

desegregation obligations. See Doc. 1141 at 168-74. Gardendale High School is

an integrated high school with unique facilities and programs—including one of

the county’s best career tech programs. Id. at 170, 171-72. If GBOE appropriated

the high school, it would cost JCBOE at least $55 million to build a new

comparable facility, thereby depriving the county of money it could otherwise

spend on facilities or programming.6 Id. at 171-72. The loss of Gardendale High

School would also thwart JCBOE’s ability to obtain the important desegregation

objective of closing the nearby Fultondale High School—an outdated facility that

was built for Black students when JCSD was still a de jure racially-segregated

school system. See Id. at 69 n.26.

While the middle and elementary school facilities in Gardendale are older,

these schools have also played an important role in JCBOE’s desegregation efforts

because many Black students have chosen to attend them through JCBOE’s

6 Alabama state law concerning the transfer of facilities in school district

separations requires the “same or equivalent school facilities” for students who are

excluded from the new municipal school district and remain in the county school

system. Ala. Code §16-8-20.

22

majority-to-minority desegregation transfer program. Id. at 174. Because

Gardendale is adjacent to many African American communities, its schools are the

best transfer option for many Black students who wish to attend schools, like Snow

Rogers Elementary, Gardendale Elementary, and Bragg Middle School, with

superior academic track records for Black students. See id.

Third, the court determined that the review prescribed by Wright—the

timing of the decision to separate and the message that separation will send to the

impacted Black students—militated against the approval of Gardendale’s

separation. “During Gardendale’s separation effort, both words and deeds have

communicated messages of inferiority and exclusion. The message cannot be lost

on children who live in North Smithfield.” Doc. 1141 at 175. As detailed above,

the message sent to Black children from North Smithfield and Center Point was

unequivocal, humiliating, and demeaning. At different times, these children were

described as the “bitter pill” Gardendale residents needed to swallow, or the

“price” Gardendale had to pay, in order to separate. Id. They were told by white

residents that the Gardendale schools that Black children had attended for fifty

years were “OUR schools”—not theirs—and that they should have been removed

long ago. Id. at 130, 176. Integrated or majority-Black communities were held up

as a cautionary tale of what Gardendale residents “don’t want to become.” Id. at

177.

23

The predominantly Black North Smithfield students were used as a pawn in

Gardendale’s plans to create a whiter school district: they were excluded from the

new district when Gardendale believed that route was permissible and then

included (as the “bitter pill”) when Gardendale decided it needed more Black

students to meet its desegregation obligations. And the Gardendale Board

amplified these exclusionary messages, refusing to vote on plans or policies that

might contribute to the matriculation of Black students to Gardendale’s schools.

As the District Court determined, “[t]he message from separation organizers and

from the Gardendale Board is unmistakable___The message is intolerable under

the Fourteenth Amendment___The messages of inferiority in the record of this

case assail the dignity of black school children.” Id. at 179-80.

III. The District Court’s Orders Permitting Gardendale to Secede from

Jefferson County

On April 24, 2017, the District Court issued a 190-page opinion granting in

part, and denying in part, Gardendale’s motion to separate. The court recognized

that a new district seeking to secede from a parent district operating under a

desegregation order “must demonstrate that its operation will not harm the parent

district’s effort to fulfill its obligation to eliminate the vestiges of segregation to the

extent practicable.” Doc. 1141 at 162 (citing Wright, 407 U.S. at 459). The court

also recognized that Gardendale had failed to meet this burden and that Gardendale

24

had created and operated a municipal school district for the purpose of excluding

Black school children. Id. at 138, 150, 161-62, 178-80.

Nonetheless, the District Court ruled that it would permit Gardendale to

operate a new elementary-only school system that put it in charge of numerous

Black schoolchildren based on four “practical considerations.” Id. at 181. The

court’s decision was premised on its view that Gardendale’s failure to satisfy its

burden of proof gave the court the option to deny Gardendale recognition, but did

not mandate that result. Id. at 162. The court did not, however, identify any case

in which a splinter district failed to meet its legal burden but was still permitted to

secede. Nor did the court identify any case in which a city violated the Fourteenth

Amendment by creating a school district with a racially discriminatory purpose,

but nonetheless was allowed to create and operate a new district.

Under the terms of the District Court’s order, Gardendale may operate Snow

Rogers Elementary School and Gardendale Elementary School beginning in 2017-

2018; those schools would be zoned for students residing within Gardendale’s

municipal boundaries. Id. at 184. The court further ordered the parties to develop

a new desegregation order that would apply only to the nascent GBOE. Id.

JCBOE would continue to operate Bragg Middle School and Gardendale High

School, but the court permitted GBOE to renew its motion to operate a K-12

25

system after three years if it maintained good-faith compliance with the new

desegregation order.7 Id.

On May 2, 2017, Plaintiffs-Appellants moved the District Court to alter or

amend its judgment. Doc. 1151 (“Pis.’ Am. Mot. to Alter or Am. J. and Mem.”).

Plaintiffs-Appellants contended, inter alia, that the court’s remedy was foreclosed

by the law of the case, that the remedy did not cure Gardendale’s constitutional

violation, and that it gave the court’s imprimatur to Gardendale’s unconstitutional

conduct. Id. at 14-24. The court denied Plaintiffs-Appellants’ motion on May 9,

2017. Doc. 1152. On May 23, 2017, Plaintiffs-Appellants filed a notice of appeal

and a motion to stay all proceedings. Doc. 1159; Doc. 1160. The same day,

GBOE filed a notice of appeal, and joined in the motion to stay the proceedings.

Doc. 1162 (“Transmittal to U.S. Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit”). On June 1,

2017, the District Court stayed the relevant parts of its April 24, 2017 Order. Doc.

1174.

IV. Standard of Review

Both issues presented in this appeal concern challenges to the District

Court’s remedial order in this desegregation case. The factual findings of the

District Court may not be set aside unless they are shown to be “clearly

7 The court’s order included several other components that are not relevant

to the instant appeal. See id. at 185.

26

erroneous.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a)(6). The court’s remedial order is reviewed for

abuse of discretion. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Cty. Bd. ofEduc., 888 F.2d 82, 83

(11th Cir. 1989). However, “an error of law is an abuse of discretion per se.”

Alikhani v. United States, 200 F.3d 732, 734 (11th Cir. 2000). A clear error of

judgment also constitutes an abuse of discretion. See United States v. Whatley, 719

F.3d 1206, 1219 (11th Cir. 2013).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Controlling precedent establishes a clear test for determining whether a

newly created school district may secede from a parent district operating under a

federal desegregation order: secession is permitted only if the formation of the

new district will not impede the dismantling of the racially-discriminatory, dual

school system in the parent district. The burden is on the proponents of the

seceding district to show that desegregation efforts in the parent district will not be

undermined. As this Court’s predecessor stated in a prior appeal in this very case,

the “District Court may n o t. . . recognize [the] creation” of the splinter district if

its proponents do not satisfy this burden. Stout v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. ofEduc., 448

F.2d 403, 404 (5th Cir. 1971) (hereinafter “Stout F).

Here, the District Court correctly found that the proponents of secession in

Gardendale had not met their burden of showing that the separation would not

undermine desegregation efforts in Jefferson County. Yet, the court nonetheless

27

concluded that it had the remedial discretion to allow Gardendale to splinter a

portion of its schools from Jefferson County. The District Court recognized that its

ruling was inconsistent with Stout /, but concluded that Stout I had been overruled

in relevant part by Wright v. Council o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972). That was

clear error. Wright not only cited Stout I with approval, it specifically endorsed the

holding of Stout I, i.e., “a new school district may not be created where its effect

would be to impede the process of dismantling a dual system.” Id. at 470. That

rule has likewise been reaffirmed in binding Fifth Circuit precedent since Wright.

Because Gardendale failed to show that its request to secede would not undermine

desegregation in Jefferson County, the only remedial option available to the

District Court was to deny Gardendale’s secession request in its entirety.

The District Court’s order must also be reversed because Gardendale’s

secession was motivated by intentional discrimination. The District Court

unambiguously found that Gardendale’s secession was motivated by the desire to

exclude Black children from its schools, and that its separation effort violated the

Fourteenth Amendment. Consequently, Gardendale’s actions have “no legitimacy

at all under our Constitution,” City o f Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358,

378 (1975), and its secession may not be permitted. In sum, one cannot cure the

constitutional infirmity inherent in the creation of a public-school system for the

28

purpose of excluding Black children by allowing the formation of a school system

created for the purpose of excluding Black children.

ARGUMENT

I- Recognition of the Gardendale School District Is Foreclosed by Binding

Precedent and by the Law of the Case.

The District Court correctly determined that Gardendale failed to prove that

its separation would not impede the desegregation of Jefferson County’s schools.

Doc. 1141 at 158-59. Under controlling law, that should have been the end of the

matter. As the District Court recognized, the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Stout I

‘“did not give the trial court a choice as to whether it ‘may or may not’ recognize

[a] splinter district’s creation’” where the district failed to meet its burden of proof.

Doc. 1152 at 37 (citation omitted). Instead, “the district court may no t. ..

recognize [its] creation.” Stout I, 448 F.2d at 404.

Yet, the District Court nonetheless allowed Gardendale to secede from the

Jefferson County School District. Although the court (temporarily) prohibited

Gardendale from operating Gardendale High School or Bragg Middle School, it

permitted Gardendale to separate from JCSD, create its own school district, and

immediately begin operating Gardendale Elementary School and Snow Rogers

Elementary School. Doc. 1141 at 185. The District Court concluded that it had

the authority to permit Gardendale’s secession because it understood the Supreme

Court’s decision in Wright to represent a “change in controlling authority” with

29

respect to a district court’s authority to recognize splinter districts. Doc. 1152 at

37. The District Court further stated that it did “not believe it its [sic] bound under

the law of the case doctrine to follow the mandatory language in Stout /.” Id. at 39.

But, as explained below, Wright did not overrule Stout I. Wright not only

cites Stout I favorably, the holding in Wright is indistinguishable from Stout /: “We

hold . . . that a new school district may not be created where its effect would be to

impede the process of dismantling a dual system.” Wright, 407 U.S. at 470.

Wright certainly did not “directly overrule” Stout I. Fla. League o f Prof’l

Lobbyists, Inc. v. Meggs, 87 F.3d 457, 462 (11th Cir. 1996). Consequently, Stout

I—which barred the District Court from recognizing Gardendale both as a matter

of precedent and under the law-of-the-case doctrine—remains binding case law.

See id.

Indeed, the holding of Stout I is enshrined in Fifth Circuit cases that

postdated and expressly relied upon Wright. As stated in one of those cases: “The

division of a school district operating under a desegregation order can be permitted

only if the formation of the new district will not impede the dismantling of the dual

system in the old district.” Ross v. Houston Indep. Sch. Dist., 583 F.2d 712, 714

(5th Cir. 1978) (citing, inter alia, Wright)', see also Stout v. Jefferson Cty. Bd. o f

Educ., 466 F.2d 1213, 1215 (5th Cir. 1972) (hereinafter “Stout IF).

30

Because the District Court’s order is grounded in its misinterpretation of

these controlling legal principles, its decision must be reversed. See Alikhani, 200

F.3d at 734 (“an error of law is an abuse of discretion per se”).

A. Controlling Law Prohibits District Courts from Approving a

Splinter District if the District Cannot Prove that Its Secession

Would Not Undermine Desegregation Efforts in the Parent

District.

The law governing seceding districts has its origins in North Carolina State

Board o f Education v. Swann, a school desegregation case where the Supreme

Court addressed the legality of a facially-neutral state law that prohibited the

“[ijnvoluntary bussing of students.” 402 U.S. at 44 & n.l. In operation, the law

obstructed a desegregation remedy ordered by a federal district court. The

Supreme Court struck the law down, holding, “if a state-imposed limitation on a

school authority’s discretion operates to inhibit or obstruct the . . . disestablishing

of a dual school system, it must fall.” Id. at 45. Significantly, the Court did not

hold that a district court had the discretion to determine whether or not to

invalidate a law under these circumstances; the Court held that the law “must fall.”

Id.

Two months later, the Fifth Circuit decided two cases that applied this

principle in the context of a splinter district that sought permission to secede from

a parent district operating under a desegregation order. See Lee v. Macon Cty. Bd.

o f Educ., 448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971); Stout I, 448 F.2d 403. Both cases adopted

31

a legal standard consistent with the standard applied by Swann. In Lee, the Fifth

Circuit addressed a desegregation dispute where a splinter district had asserted its

independence from the parent district, and the district court had refused to

recognize the splinter district as an independent school system. The Fifth Circuit

agreed that the district court’s approach “was the proper way to handle the problem

raised by [a splinter district]’s reinstitution of a separate school system.” Lee, 448

F.2d at 752. Lee held that “[t]he city cannot secede from the county where the

effect—to say nothing of the purpose—of the secession has a substantial adverse

effect on desegregation of the county school district.” Id. As the Court observed,

if such separations “were legally permissible, there could be incorporated towns

for every white neighborhood in every city.” Id.

Seven days later, the Fifth Circuit decided Stout /, where it resolved the

same issue in an earlier appeal from this case. In Stout I, the Court explicitly relied

on Swann's rejection of “state-imposed limitation[s]” that “impede the

disestablishing of a dual school system.” See Stout I, 448 F.2d at 404. Applying

Swann to the splinter-district context, Stout I held that “where the formulation of

splinter school districts, albeit validly created under state law, have the effect of

thwarting the implementation of a unitary school system, the district court may not

•. . recognize their creation.” Id.

32

Within a year of the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Stout I, the Supreme Court

decided Wright. 407 U.S. 451. The district court opinion in Wright aligned with

Stout I, holding that “this Court must withhold approval [for a proposed splinter

district] ‘if it cannot be shown that such a plan will further rather than delay

conversion to a unitary, nonracial, nondiscriminatory school system.”’ Wright v.

Sch. Bd. o f Greensville Cty., 309 F. Supp. 671, 680 (E.D. Va. 1970) (quoting

Monroe v. Bd. o f Comm ’rs o f Jackson, 391 U.S. 450, 459 (1968)) (emphasis

added). On appeal, the Fourth Circuit reversed, ruling that the district court could

not deny recognition to the splinter district unless the “dominant purpose” of the

proposed separation was discriminatory. See Wright, 407 U.S. at 461. The

Supreme Court granted certiorari and reversed the Fourth Circuit’s decision. In so

doing, the Supreme Court cited both Lee and Stout I with approval, and held that

the district court’s approach—which tracked Lee and Stout I— “was proper.” Id.

at 462.

Wright made clear that the district court bore primary responsibility for

determining the effect of a proposed separation “upon the process of

desegregation,” and that rendering this “essentially factual determination” “is a

delicate task that is aided by sensitivity to local conditions.” Id. at 466, 470.

However, the Court made equally clear that once a district court balances the

relevant factors and makes the factual determination that a proposed separation

33

will impede desegregation, the court is obligated to halt the splinter district: “We

hold only that a new school district may not be created where its effect would be to

impede the process of dismantling a dual system.” Id. at 470.

After Wright, the Fifth Circuit (in opinions that are controlling here)8

continued to reaffirm the rule that district courts may not permit splinter districts if

the effect would be to impede desegregation efforts in the parent district. Indeed,

while the Supreme Court was considering Wright, Stout was remanded to the

District Court, which dissolved the splinter district of Pleasant Grove because it

stood as an impediment to the desegregation of Jefferson County’s schools. See

Stout II, 466 F.2d at 1215. Pleasant Grove appealed, and the Fifth Circuit “held

this case for the Supreme Court’s determination” in Wright. Id. Following the

issuance of Wright, the Fifth Circuit “affirm[ed] the district court’s determinations

as regards the splinter school districts.” Id. The panel noted that Wright had cited

Lee and Stout I “with approval,” and predicated its ruling on the Supreme Court’s

decision in Wright “and its reliance on our prior Stout [I] order.” Id. It held that

Pleasant Grove could not be recognized as a separate school district unless and

until it “demonstrates to the district court’s satisfaction by clear and convincing

8 See Bonner v. City o f Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206, 1209 (11th Cir. 1981) (en

banc) (adopting as binding precedent all decisions of the former Fifth Circuit

handed down prior to October 1, 1981).

34

evidence that it” would not impede the desegregation of Jefferson County. Id.

Stout II also reaffirmed Stout F s holding that a “district court may no t. . .

recognize the[] creation ’ of a splinter school district if doing so would impede the

parent district’s desegregation efforts. Id. at 1214. Thus, the Stout I standard that

the District Court in this case found to have been “change[d]” by Wright, see Doc.

1151 at 36-37, was in fact expressly reaffirmed in a binding Circuit opinion that

relied on Wright to reach its conclusion.

Six years later, the Fifth Circuit again reiterated the rule set forth in Stout I.

In Ross v. Houston Independent School District, 583 F.2d 712 (5th Cir. 1978), the

district court enjoined the creation of a splinter district where the parent district

was “suffering from the ‘white flight’ phenomenon” and where formation of the

proposed splinter district “would exacerbate this problem” and “act as a catalyst to

increase white flight.” Id. at 715. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s

ruling, and held that “[t]he division of a school district operating under a

desegregation order can be permitted only if the formation of the new district will

not impede the dismantling of the dual school system in the old district.” Id. at 714

(citations omitted). “In such a situation, the proponents of the new district must

bear a heavy burden to show the lack of deleterious effects on desegregation.” Id.

Because the proposed splinter district “had not borne that burden” in Ross, the

district court was obligated to deny its separation request. See id.

35

B. The District Court Erred by Concluding that S to u t I Is No Longer

Good Law.

As the foregoing discussion makes clear, Stout I was not overruled by

Wright. On the contrary, Wright endorses Stout Ps (and Lee’s) holding, as do the

Fifth Circuit’s subsequent decisions in Stout II and Ross. These cases stand for a

simple proposition: a district court may not recognize a splinter district if doing so

would impede desegregation efforts in the parent district. See Wright, 407 U.S. at

467; Ross, 583 F.2d at 714; Stout II, 466 F.2d at 1214-15; Stout I, 448 F.2d at 404;

Lee, 448 F.2d at 752.

The District Court acknowledged that Stout I prohibited district courts from

recognizing a splinter district’s creation where it would impede the parent district’s

desegregation efforts; however, the court believed that Wright overruled Stout 1

and provided district courts with the discretion to recognize splinter districts even

under those circumstances. See Doc. 1152 at 36-37, 39. The discussion in the

previous section shows why that conclusion is untenable. More specifically, the

District Court made three errors: it misinterpreted Wright, it failed to follow

binding Fifth Circuit decisions postdating Wright in Stout II and Ross; and it failed

to acknowledge that Stout I and Stout II control the resolution of this issue because

they are the law of the case.

First, the District Court misidentified Wright's governing legal standard. As

discussed, Wright (like Stout I) held that a district court “may not” recognize a

36

splinter district if the district would impede desegregation efforts in the parent

district: “We hold only that a new school district may not be created where its

effect would be to impede the process of dismantling a dual system.” Wright, 407

U.S. at 470. Despite its extensive reliance on Wright, the District Court failed to

cite this unequivocal language setting forth Wright’s holding. See Doc. 1141 at

158-83.

Instead, the District Court stated that the “pertinent part” of Wright, Doc.

1152 at 36, is the following statement: “a district court, in the exercise of its

remedial discretion, may enjoin [the separation] from being carried out.” Wright,

407 U.S. at 460. The District Court interpreted this statement as giving “the trial

court a choice as to whether it ‘may or may not’ recognize a splinter district’s

creation.” Doc. 1152 at 37. That interpretation is foreclosed by the unequivocal

holding of Wright set forth above, and it fails to recognize the context in which the

“may enjoin” statement appears in Wright. That statement was a response to the

local officials’ argument on appeal: namely, that the City of Emporia was “a

separate political jurisdiction entitled under state law to establish a school system

independent of the county,” and therefore, “its action may be enjoined only upon a

finding that” the state law is invalid, that the city boundaries were drawn to

exclude African Americans, or that the racial disparity between the city and the

county itself violated the Constitution. Wright, 407 U.S. at 459 (emphasis added).

37

In other words, this portion of the Court’s opinion refers to “the power of the

district court to enjoin Emporia’s withdrawal” in the absence of an independent

constitutional violation. Id.

In this context, the Court’s “may enjoin” statement in Wright conveys only

that the district court had the authority to enjoin Emporia in the absence of “an

independent constitutional violation” so long as its separation “would impede the

dismantling of the dual system.” Id. at 459, 460. At this point in the opinion, the

Court had not yet addressed the question whether a district court must bar the

creation of a splinter district if that district’s secession would impede desegregation

efforts in the parent. The court’s focus was limited to the question of whether a

district court could bar the creation of a splinter district that was valid under state

law. That Wright did not seek to alter the rule announced in Stout I is confirmed

by the language of Wright's holding and by its approving citation to the rule

established in other federal courts—including Lee and Stout I—that “splinter

school districts may not be created” where the effect of the separation impedes

desegregation. Id. at 462; see id. at 470.

The District Court made an additional interpretive error in discussing

Wright's statement that “‘[t]he weighing of these factors to determine their effect

upon the process of desegregation is a delicate task that is aided by a sensitivity to

local conditions, and the judgment is primarily the responsibility of the district

38

judge. Doc. 1152 at 36 (quoting Wright, 407 U.S. at 466) (additional citations

omitted). The District Court erroneously read this statement from Wright as

granting permission to a district court to choose “whether it may or may not

recognize a splinter district’s creation.” Doc. 1152 at 37.

But, this passage from Wright does not describe a district court’s remedial

discretion; it describes the district court’s fact-finding discretion. Specifically, the

passage describes the process by which a district court should determine the effect

of a secession “upon the process of desegregation.” This discussion comes at the

conclusion of a section of the Wright opinion analyzing whether or not Emporia’s

separation would affect the county school system’s desegregation efforts. See

Wright, 407 U.S. at 466. There is no dispute that district courts are charged with

this “essentially factual determination.” Id. at 470. And, here, the District Court

made that “essentially factual determination” by determining that Gardendale

failed to meet its burden of showing that its secession will not impede Jefferson

County’s desegregation efforts. Doc. 1141 at 158-83. Having made that factual

determination, the Supreme Court has established the sole remedy: the “new

school district may not be created.” Wright, 407 U.S. at 470.

The District Court also erred by failing to recognize that it was bound by

circuit authority postdating Wright. District courts within a circuit are bound by

the precedent of that circuit, see In re Hubbard, 803 F.3d 1298, 1309 (11th Cir.

39