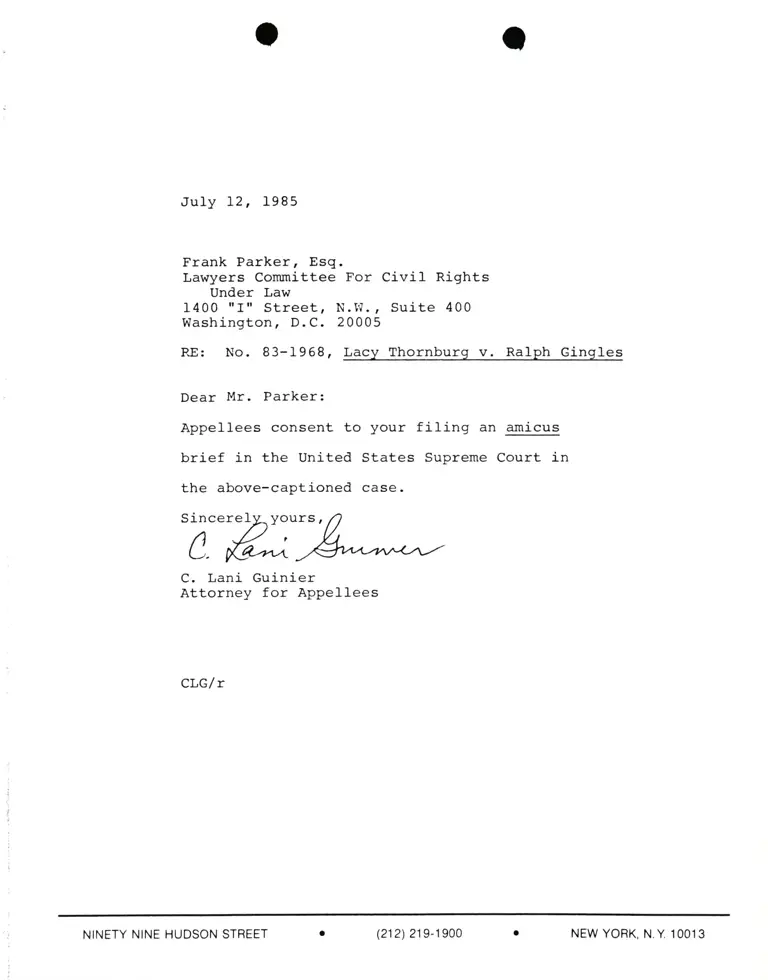

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Frank Parker, Esq. Re Thornburg v. Gingles Amicus Brief

Correspondence

July 12, 1985

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Frank Parker, Esq. Re Thornburg v. Gingles Amicus Brief, 1985. d8da0f36-e992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/63a989e1-a8d2-45b1-bb5e-1c6beed8ee2a/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-frank-parker-esq-re-thornburg-v-gingles-amicus-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JuIy L2, 1985

Frank Parker, Esq.

Lawyers Conunittee For Civil Rights

Under Law

1400 rrln Street, N.I{., Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

RE: No. 83-1958, Lacy Thornburg v. Ralph Gingles

Dear I1r. Parker:

Appellees consent to

brief in the United

the above-captioned

your filing an

States Supreme

ca8e.

arnicus

Court in

C. Lani Guinier

Attorney for Appellees

CLG/ x

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET (212) 21 9-1 900 NEW YORK. N.Y. 10013