Concurrence on Emergency Motion of Defendants for a Stay or Suspension of Proceedings

Public Court Documents

June 20, 1972

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Concurrence on Emergency Motion of Defendants for a Stay or Suspension of Proceedings, 1972. 5a15aa3d-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/63e0224a-a97a-42e6-bd19-87d40c95eaa5/concurrence-on-emergency-motion-of-defendants-for-a-stay-or-suspension-of-proceedings. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

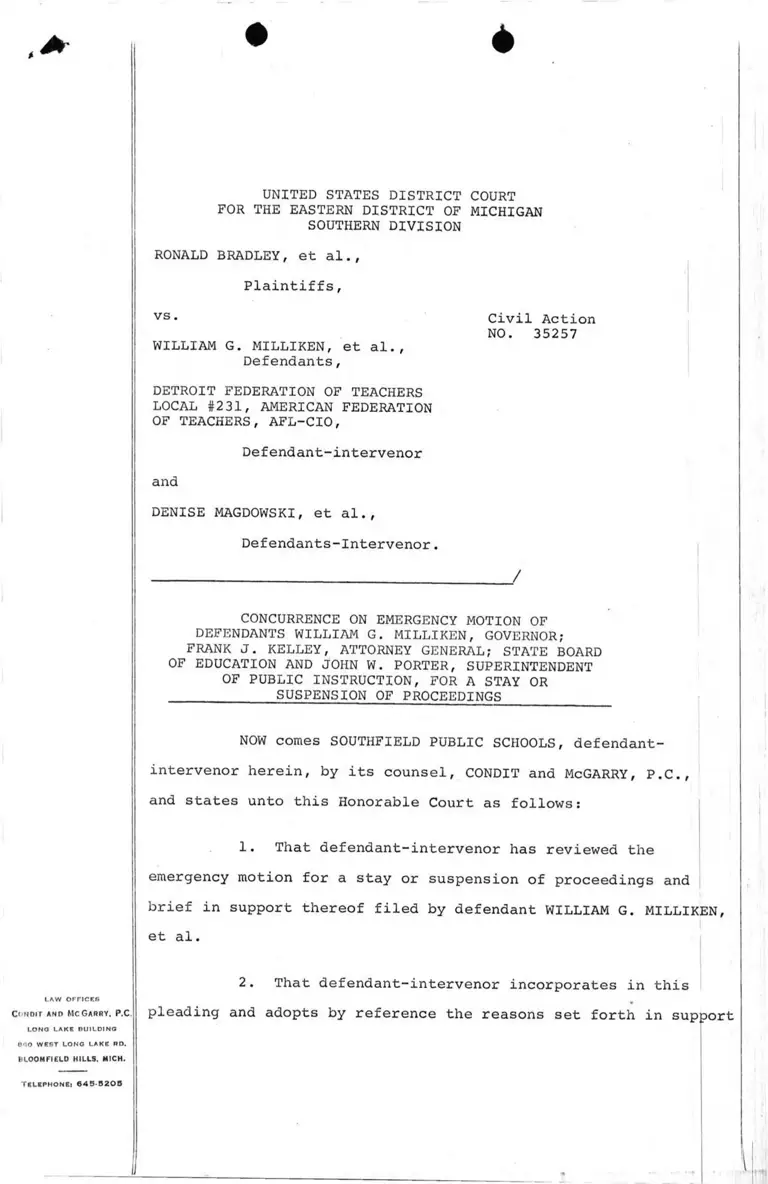

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs• Civil Action

NO. 35257WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-intervenor

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenor.

______________________________ /

CONCURRENCE ON EMERGENCY MOTION OF

DEFENDANTS WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, GOVERNOR;

FRANK J. KELLEY, ATTORNEY GENERAL; STATE BOARD

OF EDUCATION AND JOHN W. PORTER, SUPERINTENDENT

OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION, FOR A STAY OR

____________SUSPENSION OF PROCEEDINGS

NOW comes SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS, defendant-

intervenor herein, by its counsel, CONDIT and MeGARRY, P.C.,

and states unto this Honorable Court as follows:

1. That defendant-intervenor has reviewed the

emergency motion for a stay or suspension of proceedings and

brief in support thereof filed by defendant WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN,

et al.

L A W O F T I C E S

C o n d i t a n d Me G a r r y , P.C.

L O N G L A K E B U I L D I N G

OHO W E S T L O N G L A K E RD.

KUOOMFIELD HILLS. MICH.

2. That defendant-intervenor incorporates in this

pleading and adopts by reference the reasons set forth in support

T E L E P H O N E ! 6 4 S - B 2 0 3

£ *

of said motion for a stay or suspension of proceedings.

WHEREFORE, defendant-intervenor SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC

SCHOOLS concurs in the emergency motion for a stay or suspension

of proceedings filed on behalf of defendant WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN,

et al.

Respectfully submitted,

SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS

CONDIT and McGARRY,P .C.

By t ■ 1 ■___________________________________ALEXANDER B. McGARRY

Attorneys for Southfield Public

Schools, defendant-intervenor

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

645-5205

. ! .

Dated: June 20, 1972

L A W O F F I C E S

CONDIT AND MCGARRY, P.C.

L O N G L A K E B U I L D I N G

F 6 0 W E S T L O N G L A K E RD.

BLOOMFIELD HILLS, MICH.

T E L E P H O N E : 6 4 9 - 0 2 O 5

-2