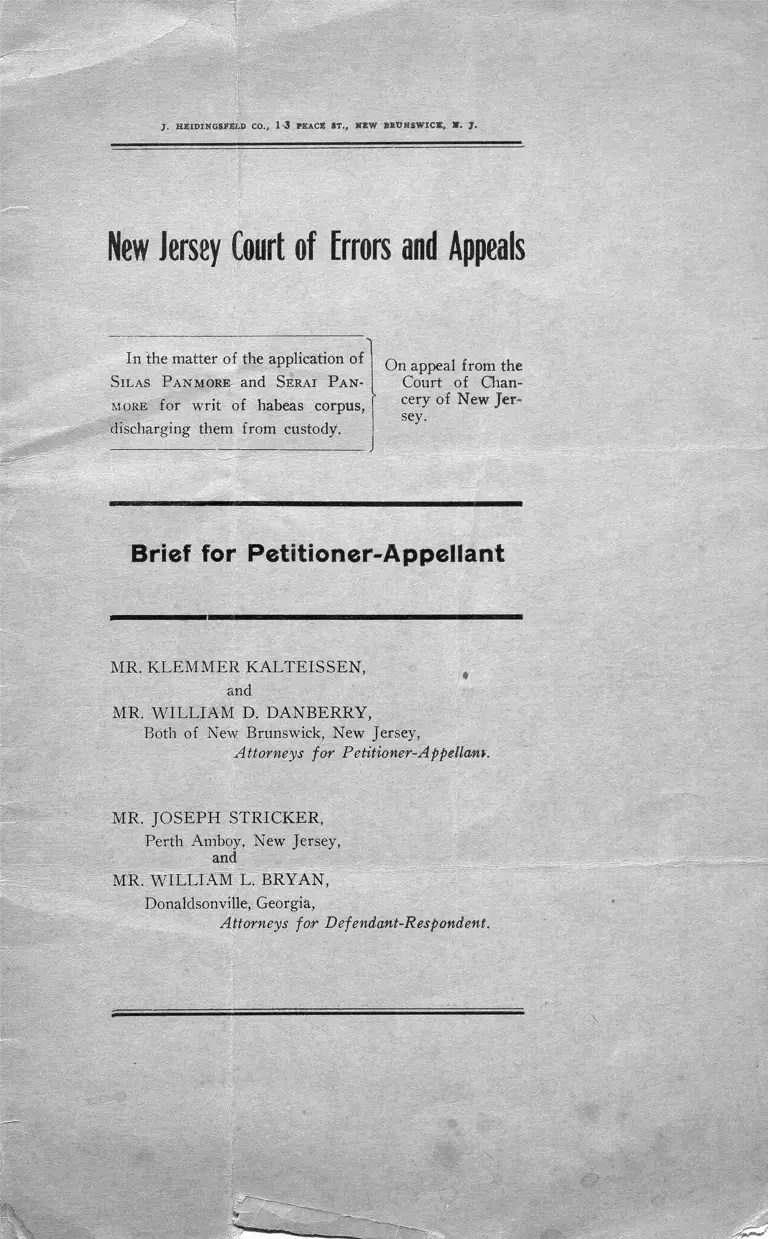

Kalteissen v. Stricker Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1923

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kalteissen v. Stricker Brief for Petitioner-Appellant, 1923. 6d9dfd90-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/64568d66-7e31-444b-be24-4ca166b49229/kalteissen-v-stricker-brief-for-petitioner-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J. H X ID IH G U X L D C O ., 1 3 F E A C E S T . , » E W B E B J S S W I C * , » . J .

New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals

In the matter of the application of

S il a s P a n m o re and S era i P a n -

more for writ of habeas corpus,

discharging them from custody.

On appeal from the

Court of Chan

cery of New Jer

sey.

Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

MR. K LEM M ER K A L T E ISSE N ,

W

and

MR. W ILLIAM D. D AN BERRY,

Both of New Brunswick, New Jersey,

Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellam.

MR. JO SE P H STR IC K ER ,

Perth Amboy, New Jersey,

and

MR. W ILLIA M L. BRYAN,

Donaldsonville, Georgia,

Attorneys for Defendant-Respondent.

New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals

In the matter of the application of

S il a s P a nm o re and S era i P a n -

m o r e for writ of habeas corpus,

discharging them from custody.

On appeal from the

Court of Chan

cery of New Jer

sey.

B R IE F FO R P E T IT IO N E R -A P P E LLA N T .

This is an appeal from an order made by his Honor,

Edwin Robert Walker, Chancellor of the State of New

Jersey, advised by Honorable John Backes, Vice-Chan

cellor, remanding the body of Silas Panmore to the cus

tody of J. Alday, Agent of His Excellency, Clifford

Walker, Governor of the State of Georgia, and denying

his application for discharge from custody.

The case was heard before the Vice-Chancellor on

despositions and the pleadings; and the petition of the

appellant, verified at length and supported by affidavits

verifying it at length, by Serai Panmore, son of the ap

pellant, and Estelle Panmore, shows that the appellant

left the State of Georgia, because he feared violence to his

person, and even loss of life at the hands of a mob pre

judiced against him because of his race and color, at that

place. The appeal is based mainly on the grounds that

the order denies him that due process of law guaranteed

him by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

I.

The O RDER O F T H E COURT O F CH ANCERY

D E N IE S T H E A P P E L L A N T D U E P R O C E SS O F

LAW , AND V IO LA T E S A M EN D M EN T F IF T E E N ,

TO T H E U N IT ED ST A T E S CO N STITU TIO N .

It has been conclusively shown in the Court below and

uncontradicted by any legal testimony, that great prejudice

2

exists against the petitioner-appellant in the State of

Georgia, demanding his return, where he is to be charged

with the murder of an officer of the Law of the State of

Georgia, of the white race; and that he will not be ade

quately protected from violence while in the custody of

that State; and that he is in grave danger of death or

other injury if returned to the demanding State; and that

because of such situation, this Court should discharge him

from custody; and that to return him would be to deny

him that due process of law which is contemplated by the

Fifteenth Amendment, in that his life and liberty would be

subjected to violence and outrage by persons assembled

in mob, and without color of Law in the demanding

State—all this, despite the fact that the authorities of the

State of Georgia, would attempt to aid, as they have at

tempted in numerous cases before without result, to pro

tect persons in the status of the ptitioner-appellant from

the fury of the mob.

The petitioner therefore believes that such decision as

this Honorable Court shall make upon this point, will be the

last legal adjudication that is likely to be made upon the

facts; and it is respectfully shown that regardless of the

guilt or innocence of the petitioner-appellant, Silas Pan-

more, his life will be taken. The several floggings testified

to by the petitioner, Serai Panmore, amply illustrate the

tension and feeling of the mob in the Commonwealth de

manding his return.

The question raised on this point has never been raised

before in any of the Courts of this State, and was pre

sented to the learned Vice-Chancellor who sat below, for

the first time in the history of New Jersey.

An examination of the authorities outside this jurisdic

tion, in order to establish some precedent for the Court

below, and for this Court, has been almost barren of re

sult. However, in the year 1909, an application was made

to the Circuit Court of the United States for the Eastern

District of Missouri, wherein among other things, race pre

judice was set forth as a reason for the Court to discharge

the petitioner from custody. The discharge from custody

was denied by the Circuit Court, and an appeal was taken

3

to the United States Supreme Court, and in the opinion

of the United States Supreme Court, delivered by Mr.

justice Harlan, the Court had the following to say, with

reference to so much of the said application as concerned

race prejudice:

“The other question to be noticed is that raised by

the following averments in the application for the writ

of habeas corpus:

“ ‘Your petitioner further states that he is a negro,

and that the race feeling and race prejudice is so

bitter in the State of Mississippi (State seeking his

return), against negroes, that he is in danger if re

moved to that State, of assassination, and of being

killed, and that he cannot have a fair and impartial

trial in any of the courts of that State; and that to de

liver him over to the authorities of that State, is to

deprive him as a citizen of the United States, and a

citizen and resident of the State of Mississippi, of the

equal protection of the law.’

“ It is clear that the executive authority of the State

in which an alleged fugitive may be found, and for

whose arrest a demand is made, in conformity with

the Constitution and Laws of the United States, need

not be controlled in the discharge of his duty, by the

Constitution, by race or color, nor by mere sugges

tion—certainly, not one insupported by proof as was

the case here—that the alleged fugitive will not be

fairly and justly dealt with in the State to which it is

sought to remove him, nor be adequately protected

white in the custody of such State, against the action

of lawless and bad men.”

( Albert Marbles vs. P. Creecy, Chief of Police of

St. Louis, and Caspar J . Wolfe, Special Jailer, 215

U. S. Supreme Court Reports, page 63.)

The Court hearing the application for discharge on the

writ of habeas corpus, was entitled to assume, as no doubt

the Governor of Missouri assumed, that the State demand

ing the arrest and delivery of the accused, had no other

object in view than to enforce its laws, and that it would

by its tribunals, officers and representatives, see to it not

only that he was legally tried without any reference to his

race, but would be adequately protected while in the State’s

custody against the illegal actions of those who might

4

interfere to prevent the regular and orderly administration

of justice.

It certainly can be reasoned by implication from the

above, that the main reason for the above language lies

in the words “certainly not one insupported by proof as

was the case here.” It is quite evident from this language

that had the petitioner supported his petition by proofs

such as are before your honorable Court, in the case at

bar, to-wit: Floggings, threats, gatherings of mobs outside

the home of the petitioner and the like, the decision of the

Court in Marbles vs. Creecy, above, would have been in

favor of the petitioner; at least the Court would have gone

into the merits and considered the proofs.

The reasons argued against the Court below refusing

to return the petitioner, Silas Panmore, to sure death in

the demanding State, were, that if that Court establishes

that precedent, negroes might flee from such States as

Georgia and Mississippi, and others notorious for their

lynchings and mob violence, and find a safe haven of

refuge in such States and Commonwealths as would con

form with the view your petitioner seeks to have this Court

sustain; and as a consequence thereof, the criminal law

in the several States would be completely set at naught.

But that is a hasty conclusion. It is just as probable and

logical that the effect of the Courts of the several States

adopting the view we seek to have this Court sustain,

would be that the people in those States who take the

law in their own hands and set at naught, would be thus

sharply brought to realize that the other States of the

Union will not return a fugitive to people who rise in mobs

agains the laws of their own State, and take the lives of

the fugitives without due process of law.

There is certainly nothing in the Constitution of the

United States, or of the State of New Jersey, which has

any weight against the view your petitioner seeks to have

this court adopt. The only purpose of returning the fugi

tive to the demanding State is, that he may be dealt with

according to the Laws of that State. When it becomes

apparent to the Court and jurisdiction asked to surrender

him, that he will not be dealt with according to the Laws

5

of that State, the Courts of the State from which he is

demanded, will be certainly justified in not delivering

him up.

The temper of the Supreme Court of the United States

upon this subject, is evidenced by recent decision of that

Tribunal, argued on January 9th, 1923, and decided on

February 19, 1923, in a case which arose out of Kansas

City race riots, and which opinion was rendered by a

divided Court, Justice MacReynolds and Justice Suther

land, dissenting. The case was heard on the application

of Frank Moore, for a writ of habeas corpus, directed

to E. H. Dempsey, Keeper of the Arkansas State Peni

tentiary, and the facts can well be given in the following

silibus:

“A petition for writ of habeas corpus which alleged

that the trial at which petitioners were. convicted of

murder, and sentenced to death, was held when public

feeling growing out of a race riot was high, that the

petitioners were represented by an attorney appointed

by the court at the beginning of the trial, which lasted

only three quarters of an hour, that the denial of a

motion of a new trial based on those facts was affirmed

by the highest court of the State, and the State Chan

cery Court prohibited from entertaining an applica

tion for habeas corpus, is sufficient as against demur

rer, to show that petitioners were being deprived of

their lives without due process of law, so as to entitle

them to a hearing in a Federal Court.”

(Moore vs. Dempsey, 43 Supreme Court Reporter,

Vol. 9, Advanced sheets, 265.)

This application was made of course to a federal court

for a federal writ under the United States Constitution,

but the United States Constitution is binding upon the

state courts as well as upon federal courts; and it would

seem to be a logical conclusion drawn from the decision

in Moore vs. Dempsey above, that when a state court is

presented with facts which show that the alleged fugitive’s

life will be taken without due process of law in the de

manding State, and no evidence is produced by the de

manding State and submitted to the tribunal hearing the

application, traversing such facts presented by the peti

6

tioner, that by reason of such mob, and the silence on the

part of those able to meet the case, the state tribunal hear

ing the application is justified in assuming the facts to be

true and sufficient; and if the facts be true and sufficient

under the ruling of the United States Supreme Court in

Moore vs. Dempsey above, it is respectfully contended

that there remains nothing for the tribunal hearing the

application to do, but to discharge the applicant.

The only essential element is whether or not the appli

cant will be denied the equal protection of the law, and

due process of the law. The respondents in this case

have not produced any evidence to the Court below, by

affidavit or otherwise, which shows that they have pre

pared, and are ready to meet an emergency, and the testi

mony of the petitioner stands unimpeached.

It may be argued that we are to assume that each State

is capable of enforcing its own laws, and that the States

are ready and willing to enforce them. This presumption

in so far as it relates to the discrimination against certain

classes of people in certain commonwealths in the United

States, is at most, a fiction; because it is a well known

fact that in many States in a specific geographical section

of the country—whether because the State does not care

to enforce its own laws against certain classes of people,

or whether the State is unable to enforce its own laws

against certain classes of people, is immaterial—the laws

are not enforced.

That the State of Georgia is notorious for its lynchings

and mob violence, is a matter over which this Court could

take judicial notice, without any evidence. It is a matter

of common knowledge to the people of this State, and one

which this Court may take judicial notice of, that on

April 22nd, 1921, Governor Dorsey of Georgia, addressed

the following letter to the people of the State of Georgia:

“Atlanta, Ga.. April 22, 1921.

“To the Conference of Citizens Called to Meet This

Day at Atlanta:

A. The Negro Lynched.

B. The Negro held in peonage.

7

C. The Negro driven out by organized law

lessness.

D. The Negro subject to individual acts of

cruelty.

“Under these four headings, in the following pages

I have grouped 135 examples of the alleged mistreat

ment of Negroes in Georgia in the last two years.

Without design, or the knowledge of each other, Geor

gians, with one exception, have called these cases to

my attention as Governor of Georgia. The exception

noted was the appeal of two Negroes to Washington

for protection. Their appeal was forwarded to me,

as Governor, with the request that I should act if I

could do so, without adding to the danger in which

the Negroes stood.

“ No effort has been made to collect cases. If such

an effort were made, I believe the number could be

multiplied.

“ In some counties the Negro is being driven out as

though he were a wild beast. In others, he is being

held as a slave. In others, no Negroes remain.

“ In only two of the 135 cases cited is the ‘usual

crime’ against white women involved.

“As Governor of Georgia, I have asked you, as

citizens having the best interests of the State at heart,

to meet here today to confer with me as to the best

course to be taken. To me it seems that we stand

indicte'd as a people before the world. If the condi

tions indicated by these charges should continue, both

God and man would justly condemn Georgia more

severely than man and God have condemned Belgium

and Leopold for the Congo atrocities. But worse than

that condemnation would be the destruction of our

civilization by the continued toleration of such cruel

ties in Georgia.

“ I place the charges before you, as they have come

unsolicited, to me. I have withheld the names of

counties and individuals, because I do not desire to

give harmful publicity to those counties, when I am

convinced that, even in the counties where these out

rages are said to have occurred, the better element

regret them, and I believe, furthermore, that the better

element in these counties and the whole State, who

constitute the majority of our people, will condemn

such conditions and take the steps necessary to correct

them, when they see and realize the staggering sum

8

total of such cases, which, while seemingly confined to

a small minority of our counties, yet bring disgrace

and obloquy upon the State as a whole, and upon the

entire Southern people.

“The investigation and the suggestion of a remedy

should come from Georgians, and not from outsiders.

For these reasons, I call to your attention the fol

lowing charges, together with a suggested remedy

which you v/ill find at the end of the recital of cases.

“ (Signed) H ugh M. D o rsey ,

“ Governor.”

The assumption that each State is capable of enforcing

its own laws, and that the States are ready and willing to

enforce them, at the most, must be held to be rebuttable,

and not a conclusive presumption, because a state of a f

fairs in one of the several States can well be conceived,

where such a presumption would have to yield to facts;

and it is respectfully urged that in the case at bar, the

only facts before this Court are facts which tend to rebut

this presumption, and to show that the State of Georgia

for some reason or other, is either not willing, or not able

to protect colored alleged fugitives from lynch law and

mob violence in its jurisdiction.

The respondents did not go into the Court below and

show any precautions that have been taken such as the

requisition of militia and the like, to meet the alleged

fugitive, to protect him while in the jurisdiction of the

State of Georgia. Neither do they traverse the testimony

of the petitioner and his witnesses, so that as the matter

stands here his testimony must be presumed to be true

and unmet.

The answer of the respondents is equivalent to the fol

lowing : “We do not deny the facts set forth in your ap

plication, and we refuse to meet them. We likewise re

fuse to tell you what special precautions we have taken, if

any, to safeguard the prisoner. We demand him as of

right, and it is no one’s fear, save ours, what we do with

him.” Stripped of all pompous phraseology, this is the

answer of the State of Georgia, to the writ of habeas

corpus allowed by the Court below.

9

It is earnestly contended that as an answer, it does not

meet the situation. It is equivalent to a demurrer to the

evidence.

Hence the facts against the respondents must be as

sumed to be true, and the situation in Moore vs. Dempsey,

before the Supreme Court of the United States on Feb

ruary 19th, 1923, is met, and the petitioner should be dis

charged.

If the view this petitioner seeks to have this Court lay

down, is adopted by the courts of this State, it will like

wise be followed in many other states, and bids fair to

settle once and for all the whole lynching problem in these

United States; and as a question of policy, will work to

great advantage of the whole country.

II.

T H E CO URTS OF NEW JE R S E Y H A VE T H E

POW ER AND A U TH O R ITY TO G IVE T H E P E T I

TIO N ER A SUM M ARY H EA RIN G ON T H E

M ER ITS.

In the event that this Court fails to reach the con

clusion of the petitioner and his solicitors on the first

point above, your petitioner respectfully asks that this

Court may be moved by the facts above which were

urged for his release, in its discretion, to grant him an

inquiry into the cause of his commitment, on a criminal

charge, as provided by sections 22, 23 and 24 of the Com

piled Statutes of New Jersey, page 2639, as follows:

“An Act for preventing injury or illegal confinement,

and better securing the liberty of the people.”

Sec. 22 herein returned.

“ If it appears that the party has been arrested—that

the Court or Justice before whom the party shall be

brought on said writ of habeas corpus, shall immedi

ately after the return thereof, provide to examine

said return, and the facts as set forth therein, whether

the same shall have been upon process, or commitment,

for any criminal or supposed criminal matter or not.”

10

Sec. 23. Discharge or remand of the prisoner:

“That if any cause be shown for such imprisonment

or restraint, or for the detention thereof, such Court

or Justice shall discharge such party from the custody

or restraint under which he is held; but if the party be

not entitled to his discharge, and be not bailed, the

Court or Justice shall remand him to the custody or

place him under the restraint from which he was

taken, if the person under whose custody he was, be

legally entitled thereto; if not so entitled, he shall be

committed by such Court or Justice to the custody of

such other officer or person as by law is entitled there

to.”

Sec. 24. Inquiry into the cause of commitment on crim

inal charge. Taking evidence:

“That if it appears that the party has been arrested

or committed for some criminal offense or supposed

criminal offense, it shall be lawful for the Court or

Justice, in his discretion, to inquire into the cause and

grounds of the confinement or restraint of such party,

and for this purpose may summon witnesses, take

their depositions, and may by an order in writing, re

quire of any person the production of all affidavits,

documents and writings relative to the premises. And

if upon such examination, it shall appear that such

party is not entitled to his discharge, he shall be bailed

or remanded in the manner directed in the next pre

ceding section. When this course is taken, the party

shall not be entitled to his discharge by reason of any

informality or insufficiency in the original arrest or

commitment.”

There is no question under these sections, but that the

Courts of this State have the power and authority to in

quire in their discretion, int othe cause and grounds of the

confinement, and restraint of the alleged fugitive.

It is respectfully urged upon this Court, that the author

ity given it by that section, in reality, provides for a Mag

istrate’s hearing before a Supreme Court Justice, if that

Court cared to hear the same in its discretion. Certainly,

the fact that the life of the party in restraint is in grave

danger of mob violence if returned to the demanding

State, as has been shown in this application before the

11

Court below, should be enough to move this Court,

in its discretion, to find out what really lies behind the

case of the demanding State.

In the event that this Court should hold adversely to the

prayer of the petitioner on the first point above, your

petitioner respectfully requests that this application be

transferred to the New Jersey Supreme Court, or some

Justice thereof, according to section 24 above, to inquire

into the restraint on the merits.

Your petitioner well realizes that he is relying on the

sound discretion of this Court and the Supreme Court for

a hearing. He is confident that this Court can have no

doubt but that he firmly believes that his life and liberty

are in grave danger of mob violence if returned to the de

manded State, no matter what precautions the authorities

of that State might take to safeguard him ; and that if his

return were sought by one of the States where mob

violence and lynch law are a rare thing, no such applica

tion as this would be made to the Court. The reason

urged upon this Court for the exercise of its discretion

in granting this hearing, is the fact that the life of the

applicant is in grave danger of mob violence if returned

without such hearing.

In the event therefore, that the Court denies the first

point on this brief, your petitioner humbly requests that

this Court in its discretion, will grant him what he knows

will be the last and only fair and impartial hearing that he

will ever receive, by remanding him to the New Jersey

Supreme Court or some Justice thereof, to be dealt with

pursuant to section 24 above cited.

Respectfully submitted.

K LE M M E R K A L T E ISS E N ,

W ILLIA M D. D A N BERRY,

Solicitors and of Counsel with Petitioner.