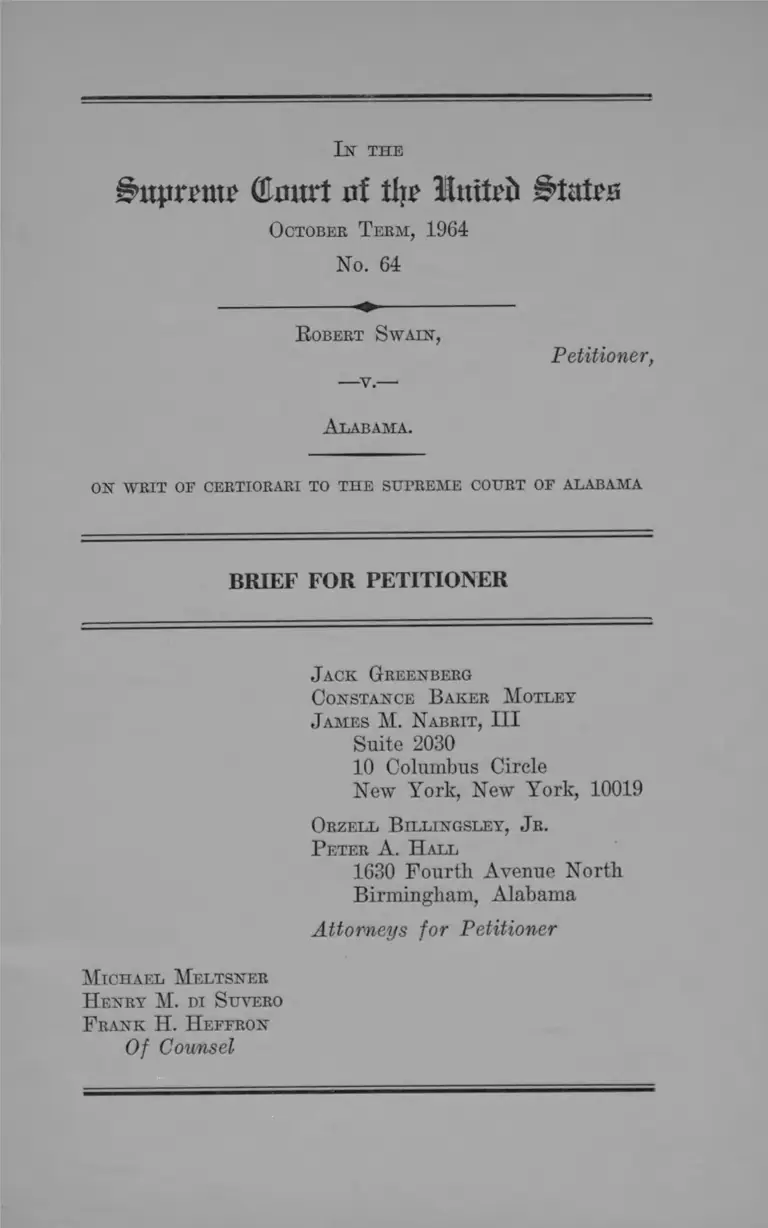

Swain v. Alabama Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swain v. Alabama Brief for Petitioner, 1964. 059bcb8a-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/648a31c9-fc06-42eb-a62b-bca52b7391a8/swain-v-alabama-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

i ’uprme GImtrt at % lutttb BUUb

October T erm, 1964

No. 64

In the

Robert Swain,

Petitioner,

A labama.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker M otley

James M. N abrit, III

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York, 10019

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

Peter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

M ichael M eltsner

H enry M. di Suvero

F rank H. H effron

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 1

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement .............................................................................. 3

Summary of Argument .................................................... 10

A rgument :

Negroes Have Been Excluded From Jury Service

in Talladega County in Violation of Petitioner’s

Rights Under the Due Process and Equal Protec

tion Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment ....... 11

A. Negroes Are Unconstitutionally Excluded

From Jury Service in That the State Always

Strikes the Token Number of Negroes on the

Trial Venires With the Result That Negroes

Never Serve on Trial Juries .................. -....... 11

B. Negroes Have Been Summoned for Jury Ser

vice in Only Token Numbers and the State

Has Offered No Explanation of the Small

Proportion Called............................................... 18

Conclusion.................................................................................... 24

A ppendix (Statutes Involved) ........................................... la

Table of Cases:

page

Ballard v. United States, 329 U. S. 187........................... 16

Berger v. United States, 295 U. S. 78 ........................... 12

Bynum v. State, 35 Ala. App. 297, 47 So. 2d 245 ....... 17

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442 ....................................... 12

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ....................................... 21, 23

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 ........................... 12

Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261 ............. ..................... 14

Hall v. United States, 168 F. 2d 161 (D. C. Cir. 1948),

cert, denied 334 U. S. 853 ............................................. 14,15

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U. S. 650 ............................... 12,16

Hayes v. Missouri, 120 U. S. 580 ................................... 16

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 ................................... 14

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 ...........................................21, 23

Johnson v. State, 23 Ala. App. 493, 127 So. 681 ........... 17

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 204 ....................................... 12

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 ........................... 12,14,23

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463 ............................... 23

People v. Boxborough, 307 Mich. 575, 12 N. W. 2d 446 .. 12

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 ...............................13, 23

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 .................................12,16,21

Speller v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443 ...............................19, 22, 23

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ....................... 16

Taylor v. State, 22 Ala. App. 428, 116 So. 415 ....... 17

Thiel v. Southern P. Co., 328 U. S. 217 ....................... 16

11

I l l

S tatutes I nvolved:

page

18 U. S. C. §243 .................................................................... 2, la

28 U. S. C. §1257(3) .......................................................... 1,14

Ala. Const., Art. I, §6 .................................................2,17, la

Ala. Code, tit. 13, §229 ...................................................... 14

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §3 ..................................................... 2, 5, 2a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §10 ................................................... 2,3, 2a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §12 ...................................................2, 3 ,3a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §18 ........................................................ 2 ,3a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §20 ...............................................2,4, 5, 3a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §21 .......................................2,4,21,22,4a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §24 .............................................. 2,20, 5a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §52 ..............................................2,17, 6a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §58 ............................................... 2,17, 6a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, § 6 0 .........................................2, 8,14,15, 6a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, § 6 4 .............................................. 3, 8 ,15 ,7a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §89 .................................................. 3,18, 7a

Acts of Ala. Special Regular Session of 1955, Act No.

475, vol. 2, p. 1081.................................................. 3,4, 5, 8a

33 Edward I, Statute 4 .................................................... 16

Other A uthorities:

Canon 5, Canons of Professional Ethics of the Ameri

can Bar Association ...................................................... 14

1961 Commission on Civil Rights Report, Vol. 5 ....... 14

I n the

g>ttprm£ ©Hurt of tljp T&mtib States

October T erm, 1964

No. 64

Robert Swain,

Petitioner,

A labama.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 219)

is reported at 275 Ala. 508, 156 So. 2d 368.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered on September 5, 1963 (R. 236) and application for

rehearing was overruled on September 26, 1963 (R. 238).

On December 19, 1963, Mr. Justice Douglas extended the

time for filing petition for writ of certiorari to and includ

ing February 22, 1964 (R. 239). The petition was filed Feb

ruary 22, 1964 and granted April 27, 1964 (R. 239).

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

here the deprivation of rights secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

2

Question Presented

Whether petitioner was denied due process of law and

the equal protection of the laws in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment when indicted, convicted and sen

tenced by grand and petit juries in a county where

A) The State always strikes the token number of Negroes

on the trial venires, with the result that Negroes never

serve on trial juries, and

B) Negroes have been summoned for jury service in

only token numbers and the state has offered no explana

tion for the small proportion called.

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following statutes which are

set forth in the appendix:

18 U. S. C. §243.

Ala. Const., Art. I, §6.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §3.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §10.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §12.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §18.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §20.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §21.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §24.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §52.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §58.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §60.

3

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §64.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §89.

Acts of Ala., Special Regular Session of 1955, Act No.

475, vol. 2, p. 1081.

Statement

The petitioner, a Negro, was indicted for rape (R. 2) and

convicted in the Circuit Court of Talladega County, Ala

bama.1 The jury fixed his punishment at death by electrocu

tion (R. 213, 214). At the hearing conducted before trial

on petitioner’s motion to quash the indictment (R. 3), the

following matters were brought out with respect to the

selection of grand and petit juries.

Census Figures

The Circuit Court judicially noticed that according to

the United States Census of 1960 the total population of

Talladega County was 65,495. The white population was

44,425 or 68 per cent, and the nonwhite population was

20,970 or 32 per cent. The total male population over 21

was 16,406, including 12,125 whites (74 per cent) and 4,281

nonwhites (26 per cent) (R. 71).

Compilation of the Jury Roll

In Talladega County, the jury box from which grand and

petit jury panels are drawn is filled every two years (R.

91) by three Jury Commissioners who are appointed by the

Governor2 and paid a nominal amount.3 Each of the Com

missioners in 1961 was self-employed (R. 50, 86, 109) and

1 The evidence presented at trial is summarized in the opinion of

the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 220-22).

2 Ala. Code, tit. 30, §10 (1958).

3 Ala. Code, tit. 30, §12 (1958).

4

performed his duties in his spare time or in conjunction

with his work. The Commissioners are assisted by a clerk

who is regularly employed as a Chief Deputy Circuit Clerk

(R. 74).

The Jury Commission meets twice yearly (R. 69, 100).

Each Commissioner presents a list of names for approval

by the Commission (R. 87-88, 111). The clerk then types

a card for each person approved, listing his name, address,

and occupation (R. 63, 74, 177). The clerk also has on tile

similar cards for persons who have served on previous

juries (R. 68-69). These cards, except for persons who

have become exempt or have been called for jury service

within the past two years (R. 91-92), are placed with the

cards made from lists presented by the Commission and are

arranged in alphabetical order according to political dis

trict, or “beat” (R. 73, 177). Once every two years, the jury

roll is typed up from the cards of eligible jurors, and the

cards are placed in the jury box, which is first emptied

(R. 174). All grand and petit jurors for the next two years

are drawn from this box.4 *

Those eligible for jury service are males aged 21 or over

“who are generally reputed to be honest and intelligent men

and are esteemed in the community for their integrity, good

character and sound judgment . . . ” 3 Habitual drunkards,

disabled persons, those convicted of offenses “ involving

moral turpitude,” and illiterates who are not freeholders

or householders are disqualified.6 Persons over 657 and

4 The procedures described above correspond substantially with

the requirements of Alabama’s general statute, see Ala. Code,

tit. 30, §20 (1958) and the special statute governing Talladega

County, see Acts of Alabama. Special Regular Session of 1955.

Aet No. 475, vol. 2, p. 1081 (infra Appendix).

* Ala. Code. tit. 30. §21 (1958).

•Ibid.

T Ibid.

5

those engaged in certain occupations8 may choose not to

serve.

The Jury Commissioners in Talladega County make no

attempt to place the names of all eligible jurors on the roll

(R. 89, 117).9 Of the 16,406 males over 21 in the County

(R. 71), approximately 2500 (R. 68, 91, 177) are on the

current jury roll. The Commissioners divide the County

three ways, and each gathers names in his designated area

(R. 106).

The Chairman of the Jury Commission testified that he

obtained names of prospective jurors by going out “ into

the community with a list of names or roll” and checking

on them (R. 52). He did not canvass from house to house

but asked persons he knew in each area for suggestions

(R. 106). However, he did not call on Negroes (R. 54) and

his association with Negroes was generally restricted to

customers in his paint store (R. 54), of whom there were “ a

few” Negroes (R. 102).

The Chairman testified that he had placed some Negroes

on the roll (R. 58) and had talked with “ just plenty of

them” about the qualifications of certain persons, but could

not name a single Negro on the jury roll without examining

it (R. 62). The Chairman underestimated the County’s

Negro population stating that in his best judgment Negroes

comprised 10 per cent of the population (R. 105).

A second Jury Commissioner testified that the jury roll

did not include all the qualified male citizens in the County

because it “ would be almost impossible to get all” (R. 89).

He stated that he used “ the same method” for selecting

8 Ala. Code, tit. 30, §3 (1958).

9 But both the general and special statutes require that the names

of all eligible persons be placed on the jury roll. See Ala. Code,

tit. 30, §20 (1958); Acts of Alabama, Special Regular Session of

1955, Act No. 475, vol. 2, p. 1081.

6

whites as he did Negroes (R. 92), and that whether an

individual met the statutory qualifications was a matter

of opinion (R. 90).

He compiled lists of qualified persons by working through

clubs and “ different people in the community and . . . lists

that they recommended” (R. 87); however, he later testified

he did not go to clubs (R. 96). For Talladega City, he used

the City Directory (R. 87). He also called on people in

their homes and businesses and had “ personal knowledge”

of qualified persons (R. 90). In addition, he used REA and

Farm Bureau lists (R. 93-94) and testified the Farm Bu

reau list contained names of whites and Negroes (R. 94).

However, he subsequently stated he did not know if any

Negroes were members of the Farm Bureau (R. 94). Al

though he was “ well acquainted” with both whites and

Negroes in the northern end of the County, he found it

“ impossible” to state in either absolute or relative terms

how many Negroes he knew (R. 97).

A third Jury Commissioner testified that in securing

names of qualified persons he did not “watch the color line”

(R. 116). He said that the Jury Commission had not con

ducted a survey of the County to obtain the names of quali

fied persons (R. 117), and that he did not “ really canvass

the community” (R. 114), but went to “ some leading citi

zen out there or some merchant that knows the people” to

obtain names of qualified persons (R. 112). He also testi

fied that the leading citizens were both white and Negro,

but he could not recall any one by name (R. 112, 113). Al

though he claimed that he had placed a few of his Negro

customers on the jury roll, he could not identify the name

of one Negro customer (R. 113) or any Negro (R. 116) on

the roll.

The Clerk of the Jury Commission testified that she did

not go out into the County to check on the qualifications of

7

prospective jurors (R. 64), but she did supply names of

prospective jurors to the Commission members “merely as

a help” (R. 64). She compiled lists of names by using

church rolls, civic club rolls, poll lists, the city directory,

and the telephone directory (R. 64-65). She also contacted

the managers of various plants requesting them to send

her lists of names (R. 66) and she requested names from

some Negroes (R. 71). She also stated that she did not

solicit the use of any Negro church rolls nor did she request

names from any Negro clubs (R. 66). As far as she knew,

Negroes did not own any plants and all the plant managers

were white (R. 66). She admitted that her acquaintance

was “ more or less confine [d] to the whites of Talladega”

(R. 72).

Composition of Venires and Juries

Three or four grand juries are organized each year (R.

9). The grand jury venire of 50 or 60 names is drawn from

the jury box by the Circuit Judge in open court (R. 11, 12,

16). These persons are summoned and approximately 35

qualified jurors without excuses appear in court (R. 11, 12,

19). Of these 35, 18 names are drawn from a hat for ser

vice on the grand jury (R. 8, 36).

The usual representation of Negroes on a grand jury

venire is 10, 12, or 15 per cent (R. 10), as estimated by the

Solicitor who was present during the empaneling of all

grand juries since 1953 (R. 8). One or more Negroes served

on 80 per cent of the grand juries drawn between 1953 and

1962 (R. 21), but no more than three Negroes ever served

(R. 9, 36). In petitioner’s case four or five Negroes were

on the grand jury venire of 33 names and two Negroes

served (R. 8, 125-26).

The petit jury venire is drawn from the jury box during

the week prior to trial (R. 16). The number of names

8

drawn varies between 75 and 100, with large venires of 90

to 100 drawn for capital cases (R. 17, 41, 202). Approxi

mately 10 to 15 per cent of this group fail to appear; in

capital cases a rough average of 75 do appear (R. 17, 41).

Some of those who appear are excused for various reasons,

including challenges for cause (R. 17-18, 20). The jury is

then struck from those who remain (R. 20). Alternating

turns, the prosecutor strikes one name and the defense

strikes two until only 12 persons remain (R. 20).10

The Solicitor estimated that 10 or 12 or 15 per cent of

the persons on the petit jury venire are Negroes (R. 10).

He has seen as few as four per cent and as many as 23 per

cent (R. 10, 19).11 He stated that the usual number of

Negroes present when the striking begins is seven or eight

(R. 18). The Circuit Clerk said that the number of Negroes

on the venire was “ usually two or three or six or seven.

One time it was eleven” (R. 126). One witness said he saw

seven or eight Negroes on a venire of 50 or 60 persons

(R. 160), and another testified that there were usually six

or seven Negroes on a petit jury venire of 35 to 40 persons

(R. 40). A judge of the Intermediate Court testified that

he had seen no more than six or seven Negroes on a venire,

but as few as two (R. 44).

In this case, there were eight Negroes on the petit jury

venire list of 100 (R. 202). Six of them were available for

service but were stricken by the State (R. 202, 205, 229).

All who testified stated that no Negro had ever served

on a petit jury of either a criminal or civil case in Talladega

10 Ala. Code, tit. 30, §§60, 64 (1958).

11 The occasion when 23 per cent were Negroes was a case prior

to 1955 in which a Negro defendant accused of killing a Negro was

offered an all-Negro jury. Thirteen Negroes were on the petit jury

venire and the prosecution offered to allow him to strike any one

and use the others as the jury. The offer was declined (R. 10

19, 23). ’

9

County. This included the Circuit Solicitor (R. 13, 14, 21),

five attorneys (R. 29, 35, 39, 40, 46), an Intermediate Court

Judge (R. 44), the Chief Deputy Circuit Clerk (R. 76), the

Chairman of the Jury Commission (R. 58), eight Negro

witnesses (R. 130, 136, 150, 153, 156, 161, 165, 166) and the

Circuit Clerk who had held his office for sixteen years

(R. 124). The State did not contest the fact that no Negro

had ever served on a petit jury (R. 183).

The Circuit Solicitor testified that the striking of a jury

is done differently depending upon whether or not the de

fendant was of the same race as the victim of the alleged

crime (R. 20). He stated that on numerous occasions he has

asked defendants whether they desired to have Negroes

serve; if they did not, and if he “ did not see fit to use them,

then we would take off. We would strike them first or take

them off” (R. 20, 27). If the defendant wanted Negroes

to serve, the Solicitor’s response “would depend on the cir

cumstances . . . and what I thought justice demanded and

what it was in that particular case” (R. 27). In one case

in which a Negro defendant was charged with the murder of

another Negro, the Solicitor offered to use an all-Negro

jury, hut the offer was declined (R. 21, 26). The Supreme

Court of Alabama found that “ the evidence discloses that

Negroes are commonly on trial venires hut are always struck

by attorneys in selecting the trial jury” (R. 229).

State’s Evidence

The State called two witnesses. The first was the Sec

retary of the Talladega Health Department and Registrar

of Vital Statistics. She testified that of the 214 illegitimate

babies born in the county in 1961, 201 were Negro (R. 186-

87); she also stated that of the 12 new cases of syphilis in

the county in 1961, 11 were Negro (R. 188); and of the

26 new cases of gonorrhea in 1961, 19 were Negro (R. 190).

The second witness for the State was the Director of

the Department of Pensions and Securities in Talladega

10

County. She testified that as of April 30, 1962, there were

3,316 male and female recipients of public assistance, of

whom 44.6 per cent were Negro (R. 193-94). She stated

that 2,205 of the recipients were “ old pensioners” (R. 194),

43 were blind persons, 695 were families receiving aid to

dependent children, 30 were neglected children and 342 were

totally disabled persons (R. 196). It was also brought out

that possession of a “ homestead” or $3000 worth of prop

erty did not disqualify a person from receiving assistance

(R. 195).

Summary o f Argument

A. Negroes are consistently struck from trial jury panels

by the prosecutor. Such racial exclusion by a representa

tive of the state violates the Fourteenth Amendment, which

prohibits systematic exclusion from jury service regard

less of the manner in which it is accomplished. There is

no justification for concluding that prohibition of racial

strikes by the prosecutor would interfere with the useful

ness of the peremptory challenge. No state can subvert the

constitutional and statutory policy against racial discrim

ination or ensure that juries will be unrepresentative of

the community. The challenges of the state have never been

considered absolute and, in fact, were conceived to assist in

the selection of an impartial jury, an end which the state’s

use of challenges makes impossible to achieve. Finally

the state has not even used its strikes for an end legiti

mately related to the litigation, but habitually strikes

Negroes because they are Negroes and for no other reason.

B. Although Negroes comprise 26 per cent of the eli

gible jurors, they play only a token role in the jury svstem

of Talladega County. No Negro has ever served on a crim

inal or civil jury in the county. Haphazard procedures

11

followed by the Jury Commissioners, some in violation of

state statute, favor selection of whites. The state recog

nized its duty to explain the relatively small number of

Negroes on the venires but produced only irrelevant sta

tistics and did not meet its burden of proof under the Four

teenth Amendment. The holding of the Supreme Court of

Alabama that petitioner must establish affirmatively that

Negroes are as qualified as whites in order to make out a

successful showing of exclusion conflicts with numerous

decisions of this Court.

A R G U M E N T

Negroes Have Been Excluded From Jury Service in

Talladega County in Violation of Petitioner’s Rights

Under the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. Negroes Are Unconstitutionally Excluded From Jury Ser

vice in That the State Always Strikes the Token Number

of Negroes on the Trial Venires With the Result That

Negroes Never Serve on Trial Juries.

Negroes have been placed on the jury venires of Talla

dega County in such token numbers that they may be

“ always struck by attorneys in selecting the trial jury”

(R. 229). Using the strikes authorized by Ala. Code, tit. 30,

§§60, 64 (1958), the Solicitor strikes one juror and the

defendant strikes two from trial jury venires in all crim

inal cases (if there are two or more defendants, each has

one strike) until there are only twelve jurors remaining.

These twelve constitute the trial jury. No Negro has ever

served on a trial jury in a criminal or civil case in the

county, and all the Negroes on petitioner’s jury venire

were struck, because the Solicitor invariably exercises his

strikes to remove Negroes summoned for jury service.

12

The state has, therefore, excluded Negroes contrary to

the “ unbroken line of cases” in which this Court has held

a criminal defendant’s Fourteenth Amendment rights vio

lated “ if he is indicted by a grand jury or tried by a petit

jury from which members of his race have been excluded

because of their race” Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584,

595. For the rule is not qualified by the form or the per

petrator of the exclusion, id. at 356 U. S. 587. The Consti

tution is violated “ by any action of a state, whether

through its legislature, through its courts, or through its

executive or administrative officers,” which results in ex

clusion of Negroes “from serving” on juries. Carter v.

Texas, 177 U. S. 442, 447 (emphasis supplied); Norris v.

Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 589. “ If there has been discrimina

tion, whether accomplished ingeniously or ingenuously,

the conviction cannot stand” Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128,

132.

Despite these principles and the intentional, systematic

exclusion of Negroes from trial jury service because of

race by a public official (accountable for his conduct under

the Fourteenth Amendment, see, e.g., Napue v. Illinois, 360

U. S. 204; Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U. S. 650),12 the

Supreme Court of Alabama approved the practice of the

Circuit Solicitor of always striking Negroes. The court,

adopting language from a Michigan case, People v. Rox-

borough, 307 Mich. 575, 12 N. W. 2d 446 (1943), held that

the utility of peremptory strikes would be impaired if any

limitation were placed on the state’s challenge to prospec

tive jurors (R. 230):

12 Cf. Berger v. United States, 295 U. S. 78, 89, where this Court

reversed on the ground that “ the misconduct of the prosecuting

attorney . . . was pronounced and persistent, with a probable

cumulative effect upon the jury which cannot be disregarded as

inconsequential.”

13

“ The reason counsel may have for exercising peremp

tory challenges is immaterial. The right has been

granted by law and it may he exercised in any manner

deemed expedient and such action does not violate any

of the constitutional rights of an accused. It would do

away with the basic attribute of the peremptory chal

lenge because if such argument is accepted in all cases

involving defendants of the Negro race, the prosecutor,

upon challenging prospective jurors of that race, would

either have to assign a cause for such challenge or take

the risk of a new trial being granted on the ground

that he discriminated because of color; as a result no

one could safely peremptorily challenge a juror where

the defendant was of the same race as the juror. . . . ”

There is no reason to believe, however, that a prosecuting

attorney, upon challenging prospective Negro jurors, would

“have to assign a cause for such challenge” (R. 230) or be

highly subject to reversal “ on the ground that he discrim

inated because of color” (R. 230). It is one thing for a

prosecutor to strike a Negro because he does not desire him

as an individual to serve on a particular trial jury or

juries, and quite another for an official of the state, as here,

to strike all Negroes from trial juries pursuant to a notori

ous practice of always excluding Negroes regardless of

the character of the individual or the case. The Jury Com

mission of Talladega County may not exclude Negroes from

jury service, but the Commission does not “assign a cause”

for failing to place Negroes on the jury rolls. No prosecu

tor who does not engage in a systematic policy of striking

jurors on account of race need fear reversal for striking

the Negroes on particular panels. A prosecuting attorney

will always be in a position to adduce proof that Negroes

are not systematically struck without great difficulty. Cf.

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, 361, 362. Such proof

14

would, of course, refute any “ logical inference to be drawn,”

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475, 480, from evidence of a

prosecutor’s conduct in any one case in the same manner as

it would with respect to a Jury Commission. Ibid. See

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 590-92, 598-99. The fears

of the Supreme Court of Alabama that “no one could safely

peremptorily challenge a juror where the defendant was of

the same race as the juror” (R. 230) are unfounded.

But whatever the risks of prohibiting racial strikes,

they are preferable to permitting a high public official13 to

undermine the constitutional requirement that no distinct

group be excluded from jury service.14 Use of peremptory

strikes by public officials is a common method of insuring

exclusion of Negroes from jury service (1961 Commission

on Civil Rights Report, Vol. 5, pp. 93, 99) which reduces

the practical effect of the Fourteenth Amendment and 18

U. S. C. §243,15 and principles enunciated by decisions of

13 The injury to constitutional administration of criminal justice

is all the greater when the racial policy attacked is injected into

the criminal process by an officer of the court with duties and

responsibilities to the public. See, e.g., Canon 5, Canons of Pro

fessional Ethics of the American Bar Association. The Circuit

Solicitor is the official in Alabama who supervises the proceedings

of grand juries, draws up indictments, and prosecutes indictable

offenses. Code of Ala. tit. 13, §229 (1958). Solicitors devote their

entire time to the discharge of the duties of the office and are

prohibited from practicing law in any other manner. Ibid.

14 It is clear that, in Alabama, the Solicitor actively participates

in the process of selecting the trial jury. Ala. Code tit. 30, §§60,

64 (1958). The prosecutor is responsible for striking a large num

ber of jurors whether or not he has any objection to them, for

he is required to strike down to the number of 12 regardless of

whether he objects to the jurors remaining on the venire.

15 Exclusion from jury service on account of race has been pro

hibited by federal statute since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. 18

U. S. C. §243 (formerly 8 U. S. C. §44) is written in broad terms

which certainly apply to exclusion by use of strikes, see Fay v. New

York, 332 U. S. 261, 282-4:

No citizen possessing all other qualifications which are or may

be prescribed by law shall be disqualified for jury service as

15

this Court, to the ritual of placing Negroes on a venire

without any possibility of actual jury service. “ The rule

against excluding Negroes from the panel has no value if

all who get on the panel may be systematically kept off the

jury” (Edgerton, J., dissenting). Hall v. United States,

168 F. 2d 161, 166 (D. C. Cir. 1948), cert, denied 334 U. S.

853.16

The Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 230) and the State,

in its Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, take the position

that the right to strike granted by Ala. Code, tit. 30, §§60,

64 (1958) is absolute and may, therefore, be employed by

a prosecutor to exclude Negroes from jury service on ac

count of race. This conclusion is at war with the history of

grand or petit juror in any court of the United States, or of any

state on account of race, color, or previous condition of ser

vitude; and whoever being an officer or other person charged

with any duty in the selection or summoning of jurors excludes

or fails to summon any citizen for such cause shall be fined

not more than $5,000.

16 In Hall v. United States, 168 F. 2d 161 (D. C. Cir. 1948) cert,

denied 334 U. S. 853, Negro defendants objected to the Govern

ment’s peremptory challenge of all nineteen Negro members of

the panel. There was no express finding that Negroes had been

struck on account of race, no claim of systematic exclusion of

Negroes from the venire, and no evidence of a practice of regularly

striking Negroes from jury panels so that they would never serve.

The court in Hall, 168 F. 2d at p. 164, found:

The due process clause of the Fifth Amendment would be

invokable if the authorities charged with the duty of selecting

jurors had systematically excluded Negroes from the panel.

The requirements of due process were met when there was

no racial discrimination in the selection of the veniremen.

The government. . . was entitled to exercise twenty peremptory

challenges . . . without assigning, or indeed without having

any reason for doing so.

Judge Edgerton, dissenting, disagreed with the majority in that

he found the government “ impliedly admits” , 168 F. 2d at 166,

that Negroes were systematically excluded from the trial jury by

use of strikes and concluded that the use of peremptory challenges

violated a federal statute as well as the due process clause of the

Fifth Amendment.

16

the peremptory strike and the values which have been given

content by the constitutional prohibition against exclusion.

The grant of peremptory challenges to the State, for ex

ample, has always been subject to restriction “ by the neces

sity of having an impartial jury” and “ the constitutional

right of the accused” under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hayes v. Missouri, 120 U. S. 580. In England, the right of

peremptory challenge in the Crown was abolished by stat

ute in 1305, 33 Edward I, Statute 4, only to be reintroduced,

on a modified basis, by rule of court. Hayes v. Missouri,

supra.

The conduct of the Solicitor, approved by the Supreme

Court of Alabama, alters the fundamental character of the

jury system by ensuring that all trial juries are unrepre

sentative of a cross-section of the community. So long as

the State is totally unrestricted in its use of strikes, no

minority is safe from complete exclusion from actual jury-

service. But juries unrepresentative of the community dis

tort “basic concepts of a democratic society and a repre

sentative government.” Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 130;

Thiel v. Southern P. Co., 328 U. S. 217, 220; Ballard v.

United States, 329 U. S. 187, 195.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, recognized that

exclusion of Xegroes from juries “ is practically a brand

upon them, affixed by law ; an assertion of their inferiority,

and a stimulant to that race prejudice which is an impedi

ment to securing to individuals of the race that equal jus

tice which the law aims to secure to all others” (100 U. S.

at 308). Cf. Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 TJ. S. 650. By strik

ing all Xegroes as a matter of course, the Solicitor places

the authority of the State and his office17 behind racial

lr The Alabama Court of Appeals has often described the duties

and responsibilities of the Circuit Solicitor as follows:

The offic-e of Solicitor is of the highest importance; he is the

representative of the State and as a result of the important

17

prejudice in the presence of the tribunal which determines

the guilt of and—in the case of petitioner— sentences a

Negro defendant.

The Solicitor indicated that he frequently asks defen

dants whether or not they want Negroes on the jury, and if

not, the prosecutor and defense attorney “ take them off” or

“ strike them first” (R. 20, 27). This evidence establishes

that Negroes are set apart; treated differently; and by this

pattern of treatment affixed with a brand of inferiority.

A petit jury is duty bound to find the facts and apply

the law in an impartial manner. Ala. Const., Art. I, §6

(1901); Ala. Code, tit. 30, §§52, 58. Challenges are per

mitted in order to obtain an unbiased jury. Challenges for

cause are designed to allow the removal of persons with

easily identifiable bias. Peremptory challenges are a means

of allowing removal of persons suspected of bias, and a

lawyer may rely on mere whim or intuition in the exercise

of peremptory challenges. But in Talladega County the

peremptory challenge has been badly perverted.

The record is clear that the striking of Negroes has noth

ing to do with the strategy of particular litigation or an

appraisal of the qualifications or interest of any individual

Negro. Negroes are struck without exception because they

are Negroes and for no other reason. It is not even pre

functions devolving upon him as such officer necessarily holds

and wields great power and influence, and as a consequence

erroneous insistence and prejudicial conduct upon his part

tend to unduly prejudice and bias the jury against the defen

dant; this without reference to the restrictions of the court.

The test in matters of this kind is not necessarily that the

conduct of our Solicitor complained of did have such an effect

upon the jury hut might it have done so? (Emphasis supplied.)

Taylor v. State, 22 Ala. App. 428,116 So. 415-416; Johnson v. State,

23 Ala. App. 493, 127 So. 681, 682; Bynum v. State, 35 Ala. App.

297, 47 So. 2d 245.

18

sumed by the State that all Negroes will vote to acquit a

Negro, even if charged with a crime against a white per

son. In this very case the Attorney-General argues that

Negro defendants do not want to be tried by juries con

taining Negroes because of a belief that they will be treated

more harshly than by whites and that Negro jurors often

vote to convict. Thus, the Supreme Court of Alabama has

sanctioned a consistent practice, engaged in by the repre

sentative of the State in its courts, of excluding Negroes

from juries not because of a belief that striking Negroes

will increase the chances of winning a given case, or pro

vide an impartial jury, but pursuant to, and in support of,

a theory of racial inferiority.

B. Negroes Have Been Summoned for Jury Service in Only

Token Numbers and the State Has Offered No Explanation

of the Small Proportion Called.

Negroes constitute more than one-fourth of the total num

ber of males over 21 years of age residing in Talladega

County, Alabama, but no Negro has ever served on a petit

jury in either a civil or criminal case (supra pp. 8-9). No

more than three Negroes have served on the grand jury of

1818 (R. 9, 36). Usually the number is less, and approxi

mately 20 per cent of the time there are no Negroes at all

on the grand jury (R. 21). On grand and petit jury venires

Negro representation averages from 10 to 15 per cent of

the total (R. 10, 19). In petitioner’s case eight Negroes

were called (six were available) to serve on the trial venire

of one hundred (R. 202) and none served on his trial jury

as a result of strikes exercised by the Solicitor (R. 205,

229). There were four to five Negroes on the grand jury

venire, two of whom served on the grand jury (R. 8, 36).

18 Twelve votes are necessary for the grand jury to indict. Code

of Ala., tit. 30, §89 (1958).

19

The Supreme Court of Alabama concluded that a suffi

cient number of Negroes were on the jury rolls because

“ from 10 per cent to 23 per cent of the members of the

grand jury panels in the past several years have been

Negroes” (R. 228). From the Solicitor’s testimony, how

ever, it is clear that the 23 per cent figure referred to a

petit jury venire, rather than grand jury venire, and was

restricted to one rather extraordinary occasion.19 The

Solicitor also testified that the number of Negroes on the

venires ranged from 4 per cent (rather than 10 per cent)

to 23 per cent (R. 19) and averaged from 10 to 15 per cent

(R. 10).

These decided variations between Negro and white par

ticipation in the jury system of Talladega County and the

Negro and white proportions of the total number of eli

gible jurors, if unexplained by the State, are sufficient evi

dence of unconstitutional racial discrimination in the selec

tion of jurors. There may be no precise “ formula for

determining when ‘tokenism’ ends and ‘fair’ representation

begins” , as was said by the Supreme Court of Alabama

(R. 229), but the State must surely offer some explanation

of why the proportion of Negroes on grand and petit jury

venires averages at most one-half of the proportion of

eligible Negroes in the population. (Cf. Speller v. Allen,

344 U. S. 443, 481, where the Court would not accept, unless

explained, a jury box in which Negroes constituted only

7 per cent of the jurors when Negroes constituted 38 per

cent of those eligible.) Although they represent 26 per

cent of those eligible, Negro participation in the jury sys

tem of the county has been limited to the extent that

Negroes play almost no role in the actual process of indict

ing, trying or sentencing persons charged with crime.

19 See note 11, supra.

20

Petitioner adduced evidence tending to show that the Jury

Commissioners followed selection procedures, some in vio

lation of state statute, which naturally tended to restrict

Negro participation in the jury system. For example, only

white church rolls and civic club lists were used to obtain

the names of prospective jurors (R. 66). The all-white

Board of Jury Commissioners relied heavily on personal

contacts with friends, acquaintances and customers in se

lecting names for the jury roll and these contacts were

predominantly with white persons (R. 97, 102, 113, 116).

One Commissioner demonstrated unfamiliarity with the

Negro community by testifying that his estimate of the

proportion of Negroes in the population was 10 per cent

(R. 105). The Clerk of the Commission, who helped gather

names of prospective jurors, acknowledged that her ac

quaintance was “more or less” confined to whites (R. 72).

Further evidence of the Commission’s failure to familiar

ize itself with the qualifications of Negro residents is found

in the fact that the Commission did not place the names of

every person possessing the qualifications on the jury rolls

(R. 89, 117), although this is required by state statute, Ala.

Code, tit. 30, §24 (1958). Neither the Jury Commission nor

its clerk undertook a systematic survey or canvass of the

County, or visited every precinct as required by §24, in

order to obtain the names of every qualified juror (R. 89,

117). The Supreme Court of Alabama excused the Commis

sion’s failure to abide by the statute on the ground that

“ no evidence was presented that only Negroes had been

left off. The means employed by the Jury Commission for

acquiring names for the rolls simply were not exhaustive

enough to insure the inclusion of all qualified persons, be

they white or Negro” (R. 229).

But the failure of the Commissioners to employ “ means”

which were “ exhaustive enough to insure the inclusion of

21

all qualified persons” obviously worked to exclude a higher

proportion of Negroes than whites because the Commis

sioners selected on the basis of acquaintance and were not

as familiar with the Negro as with the white citizens of

the County. This is a case, therefore, where the Jury Com

missioners selected prospective jurors on the basis of per

sonal acquaintance and did not perform “ their duty to fa

miliarize themselves fairly with the qualifications of the

eligible jurors of the county without regard to race.” Cas

sell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 290; Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S.

400, 404; Smith v. Texas, 311 TJ. S. 128, 132.

The only evidence offered by the State falls far short

of accounting for the gap between the number of Negroes

serving on jury venires and the Negro proportion of the

population. Although the Supreme Court of Alabama af

firmed petitioner’s conviction, it did not so much as mention

the evidence submitted by the State in attempted explana

tion of the low proportion of Negroes on the venires. This

evidence consisted of inconclusive statistics regarding cases

of syphilis and gonorrhea, illegitimacy, and receipt of

public assistance in the County.

The statistics offered have tenuous, if any, relation to

the statutory qualifications of jurors. See Ala. Code, tit. 30,

§21 (1958). Alabama has made no attempt by statute to

exclude from jury service persons suffering from venereal

disease, fathering illegitimate children or receiving public

welfare funds. While all three Jury Commissioners and

the Clerk of the Commission testified at the hearing on the

motion to quash, there is no evidence that any person,

white or Negro, has ever been excluded from jury service

on these grounds. The State apparently took the view that

these statistics indicate that many Negroes in Talladega

County were of questionable integrity and character and,

therefore, less qualified for jury service (E. 188, 189), but

22

none of the Jury Commissioners testified they took such

information into account when considering the qualifica

tions of prospective jurors. Cf. Speller v. Allen, 344 U. S.

443, 481.

The record does not reveal the theory upon which the

State would connect a contagious or congenital disease,

poverty, or cases of illegitimacy to character. But regard

less of their relevance, the statistics offered by the State

regarding disease,20 poverty,21 and illegitimacy22 do not

establish that any significant percentage of Negroes are

not qualified for jury service.

Thus the State presented no evidence on which even an

inference can be based establishing a legitimate ground for

20 The most that the evidence as to syphilis and gonorrhea showed

was that 10 or 11 more Negroes than whites contracted syphilis

(R. 188) and 12 more Negroes than whites contracted gonorrhea

during 1961 (K. 190). Even assuming that these statistics refer

to males over 21 (and the record does not show this to be the case),

evidence that 22 more Negroes than whites contracted venereal

disease in 1961 (K. 190) does not explain the decided variation

between the Negro and white proportions on jury venires in a

county with more than 16,000 males over 21. The State’s position

that these statistics cover all cases of venereal disease occurring

during the year (R. 190), nullifies any possible claim that they

represent a mere sample.

21 Viewed most favorably for the State, the evidence on receipt

of public assistance showed that 44.6 per cent of recipients were

Negroes although Negroes constituted only 32 per cent of the popu

lation. However, Alabama has no property test for jurors, except

to the extent that illiterates must be householders or freeholders.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §21 (1958). (Some householders are eligible for

public assistance (R. 195).) In the absence of evidence on the

rate of illiteracy, no inference can be drawn that a larger propor

tion of Negroes than whites are ineligible for jury service because

of poverty. Moreover, the statistics offered by the State do not

classify recipients according to sex.

22 With respect to illegitimate births, the statistics offered fail to

reveal the race, age or residence of the fathers of illegitimate chil

dren (R. 186-87) and so prove nothing of the character or integrity

of Negro males over 21 in the County.

23

ineligibility of an appreciable number of otherwise quali

fied Negroes. “ Had there been evidence obtainable to con

tradict and disprove the testimony offered by petitioner,

it cannot be assumed that the State would have refrained

from introducing it” Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, 461.

The Supreme Court of Alabama supported its determina

tion that petitioner had not established a prima facie case

of jury discrimination on the ground that “no evidence as

to the educational level of the general Negro population

was offered in support of appellant’s position” (R. 229).

This ruling that a prima facie case of systematic exclusion

requires an affirmative showing by petitioner that Negroes

are as qualified as whites to serve on juries is in direct

conflict with the decisions of this Court. In Norris v. Ala

bama, 294 U. S. 587, 591, the Court found a prima facie

case, which the state must refute, on evidence that although

Negroes were a distinct group in the county, no Negro had

ever served on a jury. “ This testimony in itself made out

a prima facie case” and “ the case thus made was supple

mented by direct testimony that specified Negroes, thirty

or more in number, were qualified for jury service,” Norris

v. Alabama, 294 U. S. at 591 (emphasis supplied). See

also Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463, 466. The holding

of the Supreme Court of Alabama assumes that Negroes

are less qualified and, therefore, must prove they are as

qualified as whites. But in Speller v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443,

481, the Court would not assume, without evidence from the

State, that “ there is not a much larger percentage of

Negroes with qualifications of jurymen” ; and in Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 289, this Court said “ . . . with no

evidence to the contrary, we must assume that a large

proportion of the Negroes of Dallas County met the statu

tory requirements for jury service.” See also Hill v. Texas,

316 U. S. 400, 404.

24

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, petitioner prays

that the judgment of the court below be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

M ichael Meltsner

H enry M. di Suvero

F rank H. H eferon

Of Counsel

Jack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

James M. Nabrit, III

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York, 10019

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

Peter A. H alt.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

A P P E N D I X

la

APPENDIX

Statutes Involved

18 U. S. C. §243

No citizen possessing all other qualifications which are

or may be prescribed by law shall be disqualified for ser

vice as grand or petit juror in any court of the United

States, or of any State on account of race, color, or pre

vious condition of servitude; and whoever, being an officer

or other person charged with any duty in the selection or

summoning of jurors, excludes or fails to summon any

citizen for such cause, shall be fined not more than $5,000.

Ala. Const., Art. I, §6

That in all criminal prosecutions, the accused has a right

to be heard by himself and counsel, or either; to demand

the nature and cause of the accusation; and to have a copy

thereof; to be confronted by the witnesses against him; to

have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his

favor; to testify in all cases, in his own behalf, if he elects

so to do; and, in all prosecutions by indictment, a speedy,

•public trial, by an impartial jury of the county or district

in which the offense was committed; and he shall not be

compelled to give evidence against himself, nor be deprived

of life, liberty, or property, except by due process of law ;

but the legislature may, by a general law, provide for a

change of venue at the instance of the defendant in all

prosecutions by indictment, and such change of venue, on

application of the defendant, may be heard and determined

without the personal presence of the defendant so applying

therefor; provided, that at the time of the application for

the change o f venue, the defendant is imprisoned in jail

or some legal place of confinement.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §3 (1958)

§3. Persons exempt from jury duty.— The following per

sons are exempt from jury duty, unless by their own con

sent : Judges o f the several courts; attorneys at law during

the time they practice their profession; officers of the

United States; officers o f the executive department of the

state government; sheriffs and their deputies; clerks of the

courts and county commissioners; regularly licensed and

practicing physicians; dentists; pharmacists; optometrists;

tenchevs while actually engaged in teaching; actuaries while

actually engaged in their profession; officers and regularly

licensed engineers of any boat plying the waters of this

■■lale, passenger bus driver-operators, and driver-operators

of motet vehicles battling freight for hire under the super-

\e.iou ot the Alabama public service commission; railroad

engineers, locomotive firemen, conductors, train dispatchers,

bus dispatchers, railroad station agents, and telegraph op

erators. when actually in sole charge of an office; news

paper reporters while engaged in the discharge o f their

duties as such; regularly licensed embalmers while actually

engaged in their profession: radio broadcasting engineers

and announcers when engaged in the regular performance

of their duties; the superintendents, physicians, and all

regular employees of the Bryce hospital in Tuscaloosa

county and the Searcy hospital in Mobile county; officers

and enlisted men of the national guard and naval militia

of Alabama, during their terms of service and convict and

prison guards while engaged in the discharge of their duties

as such.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §10 (1958)

§10. Members to be appointed by governor.— The gov

ernor shall appoint the members of the several jury com

missions who shall constitute said several commissions . . .

3a

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §12 (1958)

§12. Salaries of members.— Each member of the jury

commission shall be paid the sum of five dollars per day

for the time actually engaged in the discharge of his duties

as such member, to be paid out of the county treasury upon

the warrant of the probate judge of the county. . . . but

the compensation of each member of the commission shall

not exceed for any year of his term the following amounts:

In counties of twenty-five thousand population or less one

hundred dollars; in counties exceeding twenty-five thousand

and not exceeding fifty thousand population two hundred

dollars; in counties exceeding fifty thousand and not exceed

ing sixty thousand population three hundred dollars; and in

counties exceeding sixty thousand population six hundred

dollars; the population of said respective counties to be

determined by the last preceding federal census.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §18 (1958)

§18. Duties o f clerk. The clerk of the jury commission

shall, under the direction of the jury commission obtain

the name o f every male citizen of the county over twenty-

one and under sixty-five years of age and their occupation-

place o f residence and place of business, and shall perform

all such other duties required of him by lav,- under the direc

tion o f the jury commission.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §20 (1958)

§20. Jury roll and cards.—The jury commission shall

meet in the court house at the county seat, o f the several

counties annually, between tbe first day of August and the

twentieth day o f December, and shall make in a well hound

book a roll containing the name of every male citizen living

in the county who possessed the qualifications herein pro

scribed and who is not exempted by law from serving on

4a

juries. The roll shall be arranged alphabetically and by

precincts in their numerical order and the jury commission

shall cause to be written on the roll opposite every name

placed thereon the occupation, residence and place of busi

ness of every person selected, and if the residence has a

street number it must be given. Upon the completion of the

roll the jury commission shall cause to be prepared plain

white cards all of the same size and texture and shall have

written or printed on the cards the name, occupation, place

of residence and place of business of the person whose

name has been placed on the jury ro ll; writing or printing

but one person’s name, occupation, place of residence and

of business on each card. These cards shall be placed in a

substantial metal box provided with a lock and two keys,

which box shall be kept in a safe or vault in the office of the

probate judge, and if there be none in that office, the jury

commission shall deposit it in any safe or vault in the court

house to be designated on the minutes of the commission;

and one of said keys thereof shall be kept by the president

of the jury commission. The other of said keys shall be

kept by a judge of a court of record having juries, other

than the probate or circuit court, and in counties having no

such court then by the judge of the circuit court, for the

sole use of the judges of the courts of said county needing

jurors. The jury roll shall be kept securely and for the use

of the jury commission exclusively. It shall not be in

spected by anyone except the members of the commission

or by the clerk of the commission upon the authority of

the commission, unless under an order of the judge of the

circuit court or other court of record having jurisdiction.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §21 (1958)

Qualifications of persons on jury roll.— The jury com

mission shall place on the jury roll and in the jury box

the names of all male citizens of the county who are gener

5a

ally reputed to be honest and intelligent men and are

esteemed in the community for their integrity, good char

acter and sound judgment; but no person must be selected

who is under twenty-one or who is an habitual drunkard,

or who, being afflicted with a permanent disease or physical

weakness is unfit to discharge the duties of a ju ror; or can

not read English or who has ever been convicted of any

offense involving moral turpitude. I f a person cannot read

English and has all the other qualifications prescribed here

in and is a freeholder or householder his name may be

placed on the jury roll and in the jury box. No person

over the age of sixty-five years shall be required to serve

on a jury or to remain on the panel of jurors unless he is

willing to do so.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §24 (1958)

§24. Duty of commission to fill jury roll; procedure;

etc.—The jury commission is charged with the duty of see

ing that the name of every person possessing the qualifica

tions prescribed in this chapter to serve as a juror and not

exempted by law from jury duty, is placed on the jury roll

and in the jury box. The jury commission must not allow

initials only to be used for a juror’s name but one full

Christian name or given name shall in every case be used

and in case there are two or more persons of the same or

similar name, the name by which he is commonly distin

guished from the other persons of the same or similar name

shall also be entered as well as his true name. The jury

commission shall require the clerk of the commission to

scan the registration lists, the lists returned to the tax

assessor, any city directories, telephone directories and

any and every other source of information from which he

may obtain information, and to visit every precinct at least

once a year to enable the jury commission to properly per

form the duties required of it by this chapter. In counties

6a

having a population of more than one hundred and eighteen

thousand and less than three hundred thousand, according

to the last or any subsequent federal census, the clerk of

the jury commission shall be allowed an amount not to

exceed fifty dollars per calendar year to defray his ex

penses in the visiting of these precincts, said sum or so

much thereof as is necessary to be paid out of the respec

tive county treasury upon the order of the president of the

jury commission.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §52 (1958)

Examination of jurors.— In civil and criminal cases,

either party shall have the right to examine jurors as to

their qualifications, interest, or bias that would affect the

trial of the case, and shall have the right, under the direc

tion of the court, to examine said jurors as to any matter

that might tend to affect their verdict.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §58 (1958)

Oath of petit juror.—The following oath must be ad

ministered by the clerk, in the presence of the court, to

each of the petit jurors: “ You do solemnly swear (or

affirm, as the case may be) that you will well and truly try

all issues, and execute all writs of inquiry, which may be

submitted to you during the present session (or week, as

the case may be), and true verdicts render according to

the evidence— so help you God;” and the same oath must

be administered to the talesman, substituting the word

“ day” for “ session.”

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §60 (1958)

§60. Mode of selecting and empaneling juries in crim

inal cases other than capital cases.— In every criminal case

the jury shall be drawn, selected and empaneled as follows:

7a

Upon the trial by jury in any court of any person indicted

for a misdemeanor, or felonies not punished capitally, or

in case of appeals from lower courts, the court shall require

two lists of all the regular jurors empaneled for the week,

who are competent to try the defendant, to be made and the

solicitor shall be required first to strike from the list the

name of one juror and the defendant shall strike two, and

they shall continue to strike off names alternately until only

twelve jurors remain on the list, and these twelve thus

selected shall be the jury charged with the trial of the case.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §64 (1958)

§64. Voir dire examination of jurors as to qualifications;

mode of striking in capital cases.— On the day set for the

trial if the cause is ready for trial, the court must inquire

into and pass upon the qualifications of all the persons who

appear in court in response to the summons to serve as

jurors, and shall cause the names of all those whom the

court may hold to be competent jurors to try the defen

dant or defendants to be placed on lists, and if there is

only one defendant on trial shall require the solicitor to

strike off one name and the defendant strike off two names,

and in case there are two or more defendants on trial, the

solicitor shall strike one and every defendant shall strike

one name, and they shall in this manner continue to strike

names from the list until only twelve names remain thereon.

The twelve thus selected shall be sworn and empaneled as

required by law for the trial of the defendant or defendants.

Ala. Code, tit. 30, §89 (1958)

§89. Indictment; concurrence of twelve jurors necessary;

how indorsed.— The concurrence of at least twelve grand

jurors is necessary to find an indictment; and when so

found it must be indorsed “ a true bill,” and the indorsement

signed by the foreman.

8a

Acts of Ala., Special Regular Session of 1955, Act No. 475,

vol. 2, p. 1081.

Section 1. Unless sooner required by order of the pre

siding Judge o f the Circuit Court, the Jury Commission

of Talladega County shall meet in the county courthouse

in Talladega on the first Monday of October, 1955, and

on said day each two years thereafter, make in a well bound

book a roll containing the name of every male citizen living-

in the county who possesses the qualifications prescribed by

law and who is not exempted by law from serving on juries.

The roll shall be arranged alphabetically and by precincts

in their numerical order and the jury commission shall

cause to be written on the roll opposite every name placed

thereon their name, occupation and place of business of

every person selected and if the residence has a street num

ber, it must be given. Upon completion of the roll, the Jury

Commission shall cause to be prepared plain white cards,

all of the same size and texture and shall have written or

printed on the cards the name, occupation, place of resi

dence and place of business of the persons whose name

has been placed on the jury roll; writing or printing but

one person’s name, occupation, place of residence and of

business on one card. When the cards have been so pre

pared, the Jury Commission shall then segregate, remove

and set aside the cards bearing the names of all jurors

who served as jurors during the two years next preceding

September 15th of that year. The names of the jurors on

the cards so removed shall continue on the rolls as quali

fied jurors, but the cards shall not then be placed in the jury

box, but shall be retained as a reserve to be used as here

inafter provided. All other cards prepared as herein pro

vided, shall then be placed in a substantial metal box pro

vided with a lock and two keys, which box shall be kept in

a safe or vault in the office of the Probate Judge, and if

9a

there be none in that office, the Jury Commission shall

deposit it in any safe or vault in the Court House to be

designated on the minutes of the Commission, and one of

said keys thereof shall be kept by the President of the Jury

Commission. The other of said keys shall be kept by the

Presiding Judge of the Circuit Court for the sole use of

the Judges of the Courts of said county needing jurors.

The jury roll shall be kept securely and for the use of

the Jury Commission exclusively. It shall not be inspected

by anyone except the members of the Commission or by

the Clerk of the Commission upon authority of the Commis

sion, unless under an order of a Judge of the Circuit Court

or other court of record having jurisdiction.

Section 2. Whenever the names in the jury box are ex

hausted or so far depleted that they will probably be

exhausted at the next drawing of jurors; or whenever it

shall appear to the Presiding Judge of the Circuit Court

or Court of like jurisdiction that the jury box is so nearly

exhausted as to require refilling, and the said Judge shall

notify the President of the Jury Commission; the said Jury

Commission shall thereupon place into the jury box all

cards containing the names of jurors as prepared under

the provisions of this Act in Section 1 and which have been

withheld from the box when filled and set aside as a

reserve. Provided, however, that in placing the cards held

as a reserve in the box the Jury Commission may delete and

withhold the cards of the names of any jurors who have died

or have otherwise become disqualified from serving as

jurors.

Section 3. Notices of the requirement of the attendance

of jury service may be served by registered mail, or may

be served as provided by Section 33 of Title 30, Code of

Alabama of 1940. Should in the discretion of the sheriff

the service be made by registered mail, such service shall

10a

be as follows: It shall be the duty of the Sheriff of the

County to enclose the summons in an envelope addressed

to the person to be served and place all necessary postage

thereon and demand a return receipt. When a return

receipt, signed by the addressee is returned to the sheriff

by the post office department of the United States the

sheriff shall thereupon mark the process executed and it

shall be considered for all purposes as sufficient personal

and legal service. In the event said jury summons so mailed

should be returned to the sheriff by the post office depart

ment of the United States without delivery to the addressee

then the sheriff shall immediately make every effort per

sonally to serve said summons. The provisions of this sec

tion in reference to service by registered mail, however,

shall not apply to jury summons returnable before the

court instanter, but such summonses shall be served only

as provided by Section 33 of Title 30, Code of Alabama of

1940.

Section 4. The clerks of the several courts in which juries

are empaneled shall, from time to time as the juries are

empaneled, certify to the Jury Commission the names of all

persons so empaneled, and the Clerk of the Commission,

under the direction of the Commission, shall note opposite

the names of such persons on the jury roll the date on

which and the court in which they were empaneled.

Section 5. The clerks of the several courts shall also

certify to the Jury Commission the names of all persons

who have been found by the Court to be disqualified or

exempt, which fact shall be noted opposite their respective

names on the jury roll.

Section 6. Any authority, right, power and duty here

tofore imposed by law on the Jury Commission of the

county or the clerk thereof, and which is not by this Act

specifically repealed, shall hereafter be exercised or per

11a

formed by the Jury Commission or the clerk thereof,

respectively.

Section 7. That all laws in conflict with any of the pro

visions of this Act be and the same are hereby repealed,

it being the intent of the Legislature that the subjects

covered by this Act be the exclusive law on such subjects

in Talladega County. Provided, however, nothing contained

in this Act shall be construed to limit the present authority

of the Judge of the Circuit Court or other Court of like

jurisdiction from exercising any of the power given such

Judge under Title 30, Section 22 of the Code of Alabama

1940.

Section 8. That in the event any section, clause or pro

vision of this Act shall be declared invalid or unconstitu

tional, it shall not be held to affect any other section, clause

or provision of this Act, but the same shall remain in full

force and effect.

Section 9. This Act shall take effect immediately upon

its passage and approval by the Governor.

38