Briggs v. Arkansas Abstract and Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Arkansas Abstract and Brief for Appellants, 1960. 75ee5e6f-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/64944974-b20e-4ad4-a09b-d4071c18b97d/briggs-v-arkansas-abstract-and-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

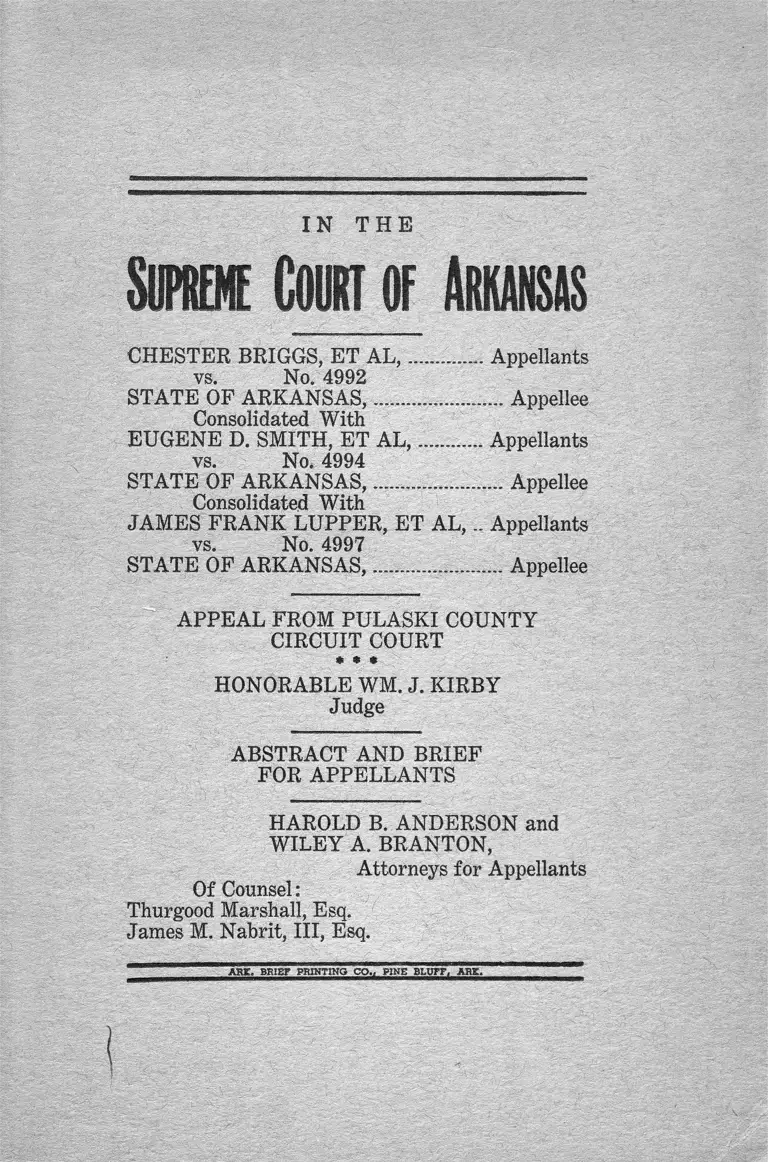

IN T H E

S i m Court of Arkansas

CHESTER BRIGGS, ET A L ,................Appellants

vs. No. 4992

STATE OF A R K A N SA S,................. Appellee

Consolidated With

EUGENE D. SMITH, ET A L , Appellants

vs. No. 4994

STATE OF A R K A N SA S,......... ....... Appellee

Consolidated With

JAMES FRANK LUPPER, ET A L ,.. Appellants

vs. No. 4997

STATE OF A R K A N SA S,........... ............. Appellee

APPEAL FROM PULASKI COUNTY

CIRCUIT COURT

* * *

HONORABLE WM. J. KIRBY

Judge

ABSTRACT AND BRIEF

FOR APPELLANTS

HAROLD B. ANDERSON and

W ILEY A. BRANTON,

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel:

Thurgood Marshall, Esq.

James M. Nabrit, III, Esq.

ARK, BRIEF PRINTING C O ., PINE BLUFF, ARK.

I N D E X

Page

Statement............................................................... 1

Points To Be Relied U p on .................................... 5

Motions For New T ria ls ................ .... ......... 6

Abstract of Testim ony........................................ 10

CHESTER BRIGGS et al V. STATE,

No. 4992 .......................................................... 10

Testimony of Witnesses for State .......... . 10

Gene Smith, Chief of P olice .................... 10

Lt. H. J. T albert............................... 11

Capt. M aack............................................... 12

Capt. Albert H aynie.......................... ........ 13

Lt. D. M. C o x .................................................. 14

Capt. R. E. B rians............. ........................... 16

J. L. B ailey............................................ IT

Valetta C ates......................................... 19

Helen Holman .................................. 20

Johnny Rives ........................-.............. . 21

Testimony on Behalf of Appellants in Briggs .... 23

Frank James ................................... 23

Vernon Mott ................................. 27

Charles Parker .................................. 32

EUGENE D. SMITH et al V. State No. 4994 .. 36

Testimony of Witnesses for S tate ...................... 36

Paul T erre ll....................... 36

Ernest M. Phillips......................................... 42

Lt. H. J. Talbert............................................. 45

W. T. Mitchell .................................... 46

JAMES FRANK LUPPER et al V. State,

No. 4997 ......................................................... 49

Testimony on Behalf of State in Lupper........ 49

Capt. Paul T errell........................................ 49

H. J. T a lbert............................................... 52

A. F. B a e r .................................................... 54

Joseph Trianfonte........................................ 57

Henry L. H o lt .............................................. 59

Testimony on Behalf of Appellants.................. 63

Frank James Lupper ................................. 63

Thomas B. Robinson.................................... 67

Argum ent............................................................... 72

I. Acts 226 and 14 are Unconstitu

tional in that they deny the De

fendants due process and equal

protection of the L a w s ..................... 72

II. The Acts have been applied in an

Unconstitutional manner.................. 76

III. The Evidence was not Sufficient to

Sustain a Conviction......................... 91

IV. The Court erred in Refusing to

Give Defendants’ Requested In

structions Numbers 3 and 5 in the

Lupper C ase........................................ 95

V. The Judgment was Excessive and

H arsh .................................................. 97

Page

IN TH E

Supreme Court of Arkansas

CHESTER BRIGGS, ET A L ,..............Appellants

vs. No. 4992

STATE OF A R K A N SAS,.......................... Appellee

Consolidated With

EUGENE D. SMITH, ET A L ,..............Appellants

vs. No. 4994

STATE OF A R K A N SAS,.......................... Appellee

Consolidated With

JAMES FRANK LUPPER, ET AL, .. Appellants

vs. No. 4997

STATE OF AR K A N SAS,.......................... Appellee

APPEAL FROM PULASKI COUNTY

CIRCUIT COURT

* * *

HONORABLE WM. J. KIRBY

Judge

ABSTRACT AND BRIEF

FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

During the Spring of 1960, several Negro col

lege students were arrested in the City of Little

Rock, Arkansas, in connection with their partici

2

pation in a so-called lunch counter sit-in demon

stration. There were two separate cases in the

Pulaski Circuit Court concerning the alleged vio

lation of Act 226 of the Acts of 1959 of the Gen

eral Assembly of Arkansas, while a third case in

volved the alleged violation of Act 226 and also

Act 14 of the Acts o f 1959. Because of the fact

that all of the cases involved the question of the

constitutionality, application and sufficiency of

the evidence as applied to Acts 14 and Act 226 of

the Acts o f 1959, the Appellants filed a Motion in

the Supreme Court of Arkansas to consolidate the

three cases for briefing and argument, and same

was granted by this Court.

CHESTER BRIGGS, ET AL, V. STATE

NO. 4992

The appellants are five Negro college students,

who entered the F. W. Woolworth Company variety

store, and sat down at the lunch counter to request

food service. The policy of the store has always

been to serve only white persons at the lunch count

er. An anonymous phone call was made to the

Little Rock police, and the Chief of Police arrived

at the store, ordered the lunch counter closed and

ordered the appellants to leave the store. The ap

pellants refused to leave the store and were arrest

3

ed and charged with a violation of Act 226. Upon

a trial before the Court in the Pulaski Circuit

Court, the appellants were each fined the sum of

$500.00 and sentenced to sixty days in jail.

EUGENE D. SMITH, ET AL, No. 4994

In this case the six defendants entered the

Pfeifer’s Department Store in Little Rock, went to

several counters then sat down at the lunch count

er, seeking service. The manager requested some

of them to leave. All of them left. One took a

little longer than the rest. They were arrested by

Officer Terrell as they left the store and charged

with violation of Act 226 of 1959. Upon a trial

before the Court, the appellants were found guilty

and were each given a sentence o f a fine of $500.00

and sixty days in jail, except the appellant Melvin

T. Jackson, who was given a fine of $500.00 and

sentenced to six months in jail. (It is not clear

whether the appellant Jackson’s sentence was sub

sequently reduced to equal that of his co-defend

ants. On page 91 of the SMITH Transcript, the

Court indicated that his sentence would be $500.00

fine and six months, but the judgment of the Court

shown on page 16, assesses a fine of $500.00 and

sixty days imprisonment in each case.)

4

JAMES FRANK LUPPER, ET AL V. STATE

NO. 4997

The appellants Lupper and Thomas B. Robin

son entered the Gus Blass store. Lupper entered

the lunch room on the mezzanine floor and request

ed food service, and there is disputed testimony

that the appellant Robinson, did likewise. There

is disputed testimony to the effect that the man

ager requested that they leave the store, and upon

their failure to leave, the manager went across the

street and found a police officer, and as they re

turned to the store, they met the appellants on the

main floor while appellants were apparently leav

ing the store. The manager stated that he was

only gone two or three minutes in getting the

police officers. The appellants were each charged

with a violation of Act 226 and also Act 14 of the

Acts of 1959. These appellants requested and were

granted a jury trial, and were convicted in the Pu

laski Circuit Court for the violation of both Acts.

They were each assessed a fine of $500.00 and

given jail sentences of six months for the violation

of Act 226, and a fine of $500.00 and a sentence of

thirty days for the violation of Act 14.

5

POINTS TO BE RELIED UPON

FOR REVERSAL

I. ACTS 14 AND 226 OF THE ACTS OF

1959 ARE UNCONSTITUTIONAL IN

THAT THEY DENY TO THE DE

FENDANTS DUE PROCESS AND

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS.

II. THE ACTS HAVE BEEN APPLIED IN

AN UNCONSTITUTIONAL MANNER.

III. THE EVIDENCE WAS NOT SUFFI

CIENT TO SUSTAIN A CONVICTION.

IV. THE COURT ERRED IN REFUSING

TO GIVE DEFENDANTS’ REQUEST

ED INSTRUCTIONS NUMBERS 3 AND

5 IN THE LUPPER CASE.

V. THE JUDGMENT WAS EXCESSIVE

AND HARSH.

6

IN THE

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

FIRST DIVISION

STATE OF ARKANSAS

vs.

CHESTER BRIGGS, ET AL

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL

The defendants alleged the following as

grounds for a new trial:

1. Because the Court erred in overruling the

defendants’ Motion to dismiss the charges filed

herein, at which action of the Court, defendants

saved their exceptions.

2. Because the findings and judgment of the

Court are contrary to the law.

3. Because the findings and judgment of the

Court are contrary to the evidence.

4. Because the findings and the judgment

of the Court are contrary to the law and the evi

dence.

WHEREFORE, defendants pray that the

findings and judgment of the Court be set aside,

that they be granted a new trial of this action.

7

IN THE

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

FIRST DIVISION

STATE OF ARKANSAS

vs.

EUGENE D. SMITH, ET AL

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL

The defendants alleged the following as

grounds for a new trial:

1. Because the Court erred in overruling the

defendants’ Motion to Dismiss which was filed

prior to the hearing of the evidence over the ex

ceptions of the defendants.

2. The Court erred in overruling defend

ants’ oral Motion to declare Act 226 unconstitu

tional for vagueness.

3. Because the Court erred in overruling de

fendants’ Motion for a direct verdict after the

State had rested.

4. Because the verdict was contrary to law.

5. Because the verdict was contrary to the

evidence.

6. Because the verdict is contrary to both

the law and the evidence.

8

7. Because the judgment is excessive.

WHEREFORE, defendants pray that the

judgmet heretofore entered in these cases be va

cated and that each of said defendants be granted

a new trial.

IN THE

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

FIRST DIVISION

STATE OF ARKANSAS

vs.

FRANK JAMES LUPPER, ET AL

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL

The defendants alleged the following as

as grounds for a new trial:

1. Because the Court erred in overruling the

defendants’ Motion to Dismiss which was filed

prior to the hearing of the evidence over the ex

ceptions of the defendants.

2. The Court erred in overruling defend

ants’ oral Motion to declare Act 226 unconstitu

tional for vagueness.

3. Because the Court erred in overruling de

fendants’ Motion for a direct verdict after the

State had rested.

9

4. Because the Court erred in overruling de

fendants’ Motion for a directed verdict after the

State and the defendants had rested.

5. Because the Court erred in giving to the

Jury the State’s requested Instructions No. 1 and

1-A over the objections and exceptions of the de

fendants.

6. Because the Court erred in giving to the

Jury the State’s requestion Instruction No. 2, over

the objections and exceptions of the Defendants.

7. Because the Court erred in giving to the

Jury the State’s requestion Instruction No. 3, over

the objections and exceptions of the Defendants.

8. Because the Court erred in giving to the

Jury the State’s requested Instruction No. 4, over

the objections and exceptions of the Defendants.

9. Because the Court erred in refusing to

give to the Jury the Defendants’ requested Instruc

tion No. 3, over the objections and exceptions of

the defendants.

10. Because the Court erred in refusing to

give to the Jury the defendants’ requested Instruc

tion No. 5, over the objections and exceptions of

the defendants.

11. Because the verdict was contrary to law.

10

12. Because the verdict was contrary to the

evidence.

13. Because the verdict was contrary to both

the law and the evidence.

14. Because the judgment is excessive.

WHEREFORE, defendants pray that the

judgment heretofore entered in this case be va

cated and that each of said defendants be granted

a new trial.

ABSTRACT OF TESTIMONY

CHESTER BRIGGS, ET AL

VS. NO. 4992

STATE OF ARKANSAS

GENE SMITH, Chief of Police, Little Rock

Police Department, witness for the State, testified

as follows: (Tr. 51-56)

On March 10,1960,1 went to Woolworth store

having been advised by Capt. Maack that there

was a sit-down strike at the lunch counter. Ac

companying me were Capt. Haynie and Lt. Cox.

Lt. Talbert was there when we arrived. Approxi

mately fifty Negroes were sitting at the lunch

counter which seated fifty-nine people. The Ne

11

groes were reading. I asked the Assistant Man

ager if he had asked them to leave. He said that

he did not have that authority. I asked him to

close the restaurant to everyone. The waitresses

removed the perishables. I told the individuals

sitting at the counter that the restaurant was

closed to everyone and for them to disperse in

order to keep down trouble. All but five left. They

were placed under arrest to get them to leave.

Quite a few people were congregated at the side

entrance of the store in front. People were lined

up three or four feet behind the stools. I was ad

vised that the management did not ask the defend

ants to leave the premises. The defendants did not

talk loud nor did they resist in any manner. I do

not know who placed the call to the police depart

ment.

LT. H. J. TALBERT, Little Rock Police De

partment, witness for the State, testified as fol

lows: (Tr. 56-66)

I was requested by the Radio man to go to

Woolworth’s. Immediately upon arrival, I saw

fifty Negroes seated at the lunch counter. One

white lady was seated about the middle. I asked

the white people who were standing there to move

back from the counter. Some of them were mad.

12

I pushed them from the aisles and back from the

front. I asked for the Manager and was advised

he was on the telephone calling long distance.

Chief Smith arrived and he took over. The crowd

was standing right behind the Negroes. The ten

sion among the whites was very high. Some of

them asked me what I was going to do. I heard

an officer ask the defendants to leave. All left but

five. The lunch counter was closed and no one

was being served. Defendants did not make any

.statement, nor were they loud or using abusive or

profane language. Did not threaten or intimidate

anyone.

CAPT. MAACK, Little Rock Police Depart

ment, witness for the State, testified as follows:

(Tr. 66-78)

I made an investigation at Woolworth’s store

on March 10, 1960, with reference to a complaint

that came to me from Mrs. Shemwell, who stated

that an unknown person had called and stated that

the sit-downers were there on strike. I accompa

nied Chief Smith, Capt. Brians and Lt. Cox. People

lined the counter and crowded the streets in front

and back of the store. The Chief talked to the

Assistant Manager. We advised everybody to

leave the counter. It was closed. Tension seemed

13

high. I talked to the defendant Mott and told him

three times that the counter was closed and if they

didn’t leave we would have to arrest them. He

told me to go ahead he wanted to be arrested. I

informed Chief Smith of this and he said all right,

we will just arrest the whole five. We did. On

leaving the store I placed my hand on Mott’s

shoulder in case he should run. He told me to

take my damn hands o ff of him. I did not notice

any loud, profane or vulgar language by oneone

except Mott. None of the defendants made any

threats.

CAPT. TALBERT HAYNIE, Little Rock Po

lice Department, witness for the State, testified as

follows: (Tr. 78-87)

On March 10, 1960, I assisted in the investi

gation at Wool worth’s with Chief Smith, Lt. Tal

bert, Capt. Brians and Sgt. McNeeley and others.

The five defendants were seated at the counter

with their backs to the counter. Chief Smith had

already given orders that the five were under ar

rest and we filed out with them. When we got to

the door, I made the remark, “ Better get hold of

their arms, they might run when they hit the side

walk.” Capt. Maack got Mott by the arms and

Mott said, “ Get your hands o ff m e!” Capt. Maack

14

told him him “ You are under arrest” and they put

him in the wagon. I know they were ordered to

leave the closed lunch counter. I did not observe

them refusing to do so. When Chief Smith order

ed, “ Let’s go” , they all got off the stools. I did not

hear the officers request them to leave before that

time. I did hear Mott say just what I have testi

fied to. The tension of the crowd was very high

when I arrived. The store was full of people. I

couldn’t guess how many. There were a lot of

people on the sidewalks at the front and at the side

doors. The officers had the aisle clear when I ar

rived there. I did not hear any profane language

or threats from the defendants to this group or

anybody at all. They did not resist arrest. I led

one of the defendants to the patrol wagon myself.

He gave me no trouble at all. I do not know who

placed the call to the police station. I did not talk

to the Assistant Manager at Woolworth’s. I have

not learned yet who placed the call to the station.

LT. D. M. COX, Little Rock Police Depart

ment, witness for the State, testified as follows:

(Tr. 87-94)

I went to Woolworth’s in Little Rock, Arkan

sas, to make an investigation on that date. It was

shortly before noon, accompanied by Capt. Brians

15

and Sgt. Shemwell. I observed approximately

forty Negroes sitting on the stools at the counter

at Woolworth’s. The white people were lined up

in the store at the rear o f them. There was an

aisle and the officers were there at that time hold

ing the crowd back, or the crowd gathered along

an aisle between them. It was more than a normal

crowd in the store. The demeanor attitude of this

crowd was very tense. Some were numbling

threats or they were mumbling, and the officers

were holding them back. I didn’t have to push

anyone back, but they were being held back some.

I estimated forty Negroes sat at the counter. I

heard Chief Smith tell them that the counter was

closed and all but five left. These five are present

today in Court. They did not leave the store. They

continued to read books and newspapers. Only

five were left at the counter. When we were tak

ing them to the patrol wagon, I heard Mott tell

Capt. Maack to take his hands o ff him. I also

heard him say he wanted to be arrested. We went

to Woolworth’s in a patrol wagon, parked it on

Fourth street across the street from Woolworth’s.

I heard one person in the crowd say that we will

do something about it, but there was mumbling to

the effect that they shouldn’t just stand there.

There was some whispering among the defend

16

ants— no loud talking between them and the crowd,

nor any threatening attitude toward the crowd.

On the way out of the store, Mott told the officer

to take his damn hands o ff him, but none of the

defendants said anything or did anything but sit

there. The defendants did not refuse to leave

when we told them they were under arrest.

CAPT. R. E. BRIANS, Little Rock Police

Department, witness for State, testified as follows:

(Tr. 95-105)

I made an investigation at Woolworth’s on

March 10, 1960. We received information that

there was a disturbance. There was people con

gregated inside the building. We pushed our way

through into the lunch counter. There were a

number of white people around the back door and

had the door virtually blocked. The situation was

very tense. There was considerable mumbling

among the white people. The colored people sit

ting at the counter were reading textbooks, news

papers. The colored people were asked to leave

and all left but five, and they were placed under

arrest. I heard Chief Smith when he told the peo

ple to leave, that the counter was closed. The situ

ation was in considerable turmoil. The white peo

ple was at the point of virtually coming to blows.

17

One person made the comment, “ Let’s have a

lynching party.” I did not notice the defendants

make any threatening remarks to anyone. I heard

no loud or profane language or violent noise. I

could see no resistance. So far as I could tell they

cooperated willingly with the police. No one struck

these defendants. I saw no clubs or weapons in

the group. It would have been impossible to iden

tify the man who indicated he wanted a lynching,

because the crowd was there. I didn’t mention

this lynching remark in Municipal Court because

I wasn’t asked that question.

J. L. BAILEY, Assistant Manager, Wool-

worth’s Store, witness for the State, testified as

follows: (Tr. 105-115)

I’m Assistant Manager of Woolworth’s store.

On March 10, 1960, I observed the police coming

in. I did not call them. The lunch counter was

closed when the police got there. I closed it. I

was instructed from my home office to do so. I

did so because Negroes came in and sat down.

The counter was closed to everyone. Charlene

Elliott, Helen Holman and Mildred Wright were

working there. I don’t know the exact number of

colored people that sat at the counter. I did not

ask them to leave. I observed the actions of the

18

police when they got there. They just came in and

stood around. I saw some colored people leave the

counter when the police came in. Five stayed. The

attitude of the other patrons toward the counter—

they seemed to be disturbed. The defendants en

tered during the regular serving hour. We don’t

have any policies regarding Negro patrons. We

will sell anything to anybody. We have a take-out

service for Negroes. I don’t know what percent

age of our business is composed of Negroes. We

do have Negro patrons. I don’t know the policy

of our lunch counter regarding service at the

counter for Negroes. Haven’t had that phase of

training yet. We don’t allow them to come in and

sit down with white folks. We had no facilities

for them to sit down at all. I didn’t call the police

department and don’t know who did. We tried to

find out, but we couldn’t. The counter wasn’t

closed when they took their seats, but I closed it.

I didn’t ask anyone to leave, nor did I request the

police department to do so. The Manager was out

of town and I was in charge at that time. I don’t

know who asked the defendants to leave, but I

didn’t. None of my employees did. I did not hear

any of the defendants use any loud noise or pro

fane language, or anybody saying anything. No

threats were made in my presence. The five just

19

went out with the police. After it was called to

my attention that these defendants and their as

sociates had taken seats at the counter, I called my

home office in St. Louis. I had been instructed

to do so. They told me to close the counter, which

I had already done. They sent a letter out to the

store to close the counter and call the home office.

Woolworth’s is a private corporation.

VALETTA CATES, Fountain Manager at

Woolworth’s witness for the State, testified as fol

lows: (Tr. 115-118)

I have worked at Woolworth’s for four years,

was working there on March 10, 1960. I was up

stairs in the store about noon on that date. I

wasn’t downstairs to observe any large number of

people come in and sit down. When I came down

stairs, I saw a bunch of colored people sitting at

the counter. I didn’t observe anyone of these pa

trons leave. Nor did I observe the police asking

anyone to leave the store. I testified in this case

in the lower court a month ago. I saw the police

talking to these Negroes sitting at the counter. I

don’t know what they were saying. I saw them

take some of them out, but I don’t know whether

they arrested them. There was a crowd up and

down all through the store there — just up and

20

down milling around — just kind of curious on

lookers.

HELEN HOLMAN, Waitress at Woolworth’s,

witness for the State, testified as follows:

I have worked at Woolworth’s about a year

and a half. Was working there on March 10,1960.

On that date, the colored boys came to the counter

and sat down. I guess about half o f the counter.

I had been instructed to leave the counter if they

came in. They came in about 11 :00 or 11:30. I

didn’t stay. I left. I couldn’t say if they occupied

about half of the stools, but they were seating

themselves as I left. There were some white peo

ple sitting there. I had been instructed to leave

the counter by Mrs. Cates. I left Mrs. Wright at

the counter. I did not close the counter, since I

did not have the authority. I don’t know that Mr.

Bailey closed it or not. I left before the police ar

rived. I didn’t call them. I didn’t say that my in

structions were to leave the counter if Negroes

came in. My manager told me to leave the count

er. I don’t remember if I testified in Municipal

Court on March 17th that I was instructed to leave

the counter if Negroes sat down. My manager had

not instructed me with reference to service of Ne

groes at that time. We do have a take-out counter

21

there to serve Negroes, but we don’t serve them

when they sit down. 1 am instructed to have the

take-out service. That is all we have. I have never

served Negroes at the counter. It would take spe

cial instruction from the manager for me to serve

Negroes at the counter.

JOHNNY RIVES, witness for the State, tes

tified as follows:

(Testified in Municipal Court and his testi

mony made a part of the record in Circuit

Court). (Tr. 50).

On March 10, 1960, about 11:30 I was sitting

on the second stool at the front door going in. A f

ter I finished my pie, I looked down the counter

and there were a number of Negroes sitting down.

There was one sitting by me. I got up and left. I

don’t know how many Negroes occupied stools

there, but there were quite a number. More than

half the stools were occupied. I didn’t call the po

lice. I don’t know who called them. I was there

when they were arrested. The police took stations

behind the occupants of the stools, then Chief

Smith came in and walked to the back— came back

up to the front of the store— told each one— not

everyone— but o ff and on— that the counter was

closed. Some got up and left by the front door and

22

back door. There were about half a dozen sitting

near the center of the store. They didn’t leave.

The police took them out the back door, after that

I don’t know. I didn’t hear any conversation be

tween the police and these five. I didn’t see the

police talking to them as they left. A crowd gath

ered after the police arrived in the store — you

know how curious — I had been there only long

enough to eat a piece of pie. There were waitresses

behind the counter and some other patrons sitting

at the counter. After the Negroes arrived and one

took a seat next to me, I got up and left the counter

and walked around behind the cosmetics counter

next to the lunch counter. I didn’t notice anything

going on behind the counter at that time. The girls

left from back of the counter. I noticed them walk

ing to the back of the store, after these defendants

and their associates took seats. I did not notice

them using loud, vulgar or abusive language. They

did not make threats to me nor did I hear them

make threats to anyone else. People wTere coming

in the store curious as to what was going on. I

visit Woolworth’s approximately three times a day,

six days a week. The lunch counter is generally

open during those hours. I did not observe the

waitresses serving anyone — either colored or

white.

23

PRANK JAMES, one of the defendants, tes

tified on his own behalf, as follows; (Tr. 128-144)

I am a student at Philander Smith College. I

am 21 years of age. I am in my third year of

college. I and the defendants here were in Wool-

worth store on March 10th of this year. I have

had occasion to visit Woolworth’s from two to

three times a w7eek since I have been in Philander

to purchase various articles. On March 10th some

where around eleven o’clock, Ledridge Davis, who

is one of the defendants and myself went into

Woolworth’s. He purchased a package of enve

lopes from the counter and then we went to the

lunch counter where we took seats. I had suffi

cient funds in my possession with which to make

purchases at the lunch counter, if I had been

served. The only thing that I did was to look over

the menu and the waitress didn’t approach me for

any request. I saw food out there on the counter,

on the steam table. There were other patrons sit

ting there, white and colored. There were white

people sitting at the counter. I think there was a

lady sitting to my right as I sat down and after

she finished her meal she left. She didn’t get up

until after she had completed her meal. The man

ager of the store did not approach me or ask me to

leave. None of the employees asked me to leave.

24

The first person to contact me in reference to leav

ing was, I think, Chief Smith and he was the only

one. I did not use any profane language or any

threats of any kind to anybody there in the store.

To my knowledge, none of the other Negroes who

were there with me used any profane language or

any threats. I didn’t notice very much of a crowd

in the way of noise because I was facing the count

er and if there was a crowd it was behind me and I

didn’t notice any disturbance until after the of

ficers arrived and began walking up and down the

aisle behind us. I didn’t hear any remarks until

after the officers arrived. I heard one lady, make

a statement like this, “ What are we going to do

now?” She was asking someone, I presume. I

did not make any threatening remarks or any

threatening conduct towards anybody in the rear.

I didn’t see Mott perform any unusual activity. I

didn’t hear Mott make any statements. I did not

hear him say anything. I think Whoever the of

ficer was that had me, we were in front of Mott

while we were proceeding outside. In my opinion,

during my three years at Philander and for my

self and the organizations that I represent, I have

made various purchases at Woolworth’s. This in

cludes the counter where they sell staples, staple

guns, etc., and school supplies there, etc., and I had

25

noticed the lunch counter and I had never seen any

Negroes sitting there, but it was in my opinion,

that since we were of the public and the doors were

open to the public that since we could purchase at

the counters where they sell these toilet articles,

that we should be permitted to sit at the lunch

counter. This was too a part of the store and if

the policy permitted us to purchase at one counter,

in my opinion, I didn’t see any reason why we

shouldn’t try to purchase at another counter.

I have been in Little Rock since I have been

attending school. I have frequently patronized

Woolworth’s to make purchases for the Junior

Class, the Panhelenic Council, for Alpha Phi Fra

ternity. I went there with another person. That

was Davis. I knew ahead of time I, with Davis,

was going to make a purchase and then go to the

lunch counter and ask for service there. I wouldn’t

say it was a scheme. I was not directed to do it

by anybody. The only meeting I would say was

the morning of the attempt as we were getting

ready to go down. The meeting was there in front

of the Student Union Building on the campus. No

one as I know of called that meeting together. I

don’t know how many were present. There were

more than five, I would say, and less than 100.

This discussion had arrived out of a general dis

26

cussion on the campus from association with fel

low students. This had been discussed, I supposed

among the students on the campus since February

when this first demonstration took place in North

Carolina. I and others on this campus discussed

doing the same thing in Little Rock. I don’t know

of any leader. I walked downtown. I assume the

others walked. There was no meeting where some

one directed me and advised me how to do it. I

have never been served at the lunch counter before,

but I had frequently been in the store. I had never

observed colored people sitting there and being

served. I didn’t know it wasn’t the custom then.

I had never seen it done before. I wasn’t told by

anyone what to do if the police came in there. I

expected to be arrested when the police told Mott

that if we didn’t leave that we would be arrested,

I was present when all of them left except me and

these other four defendants. I got up from where

I was sitting, when the police asked me to. As I

stated, I was quite a ways from Mott and some of

these other fellows and I walked down to where

they were, I had really anticipated on leaving at

that time, but then I decided that I wasn’t going

to leave if they weren’t going to leave. I am in the

third year in college. I heard the police ask me

to leave. I didn’t leave until I was told I was un

27

der arrest. I don’t recall hearing distinctly what

Mott said. I didn’t hear him say, “ I want to be

arrested” . While I was sitting at the counter, I

looked over the menu and I had my books in my

hand. I had a book as I have over there now. I

carried a book with me to the store. At the time

I left, I had planned to get back in time for class

I had a class that evening at 1:30. No one ever

approached me so I could place an order. The first

that I realized the counter was closed was when

Chief Smith told me the counter was closed, and

we would have to leave. I refused to leave until

he told me that I was under arrest. I left because

he told me I was under arrest and come go with

him to the paddy wagon or something.

VERNON MOTT, one of the defendants, tes

tified as follows: (Tr. 144-158)

My name is Vernon Mott. I am nineteen years

old, a member of Philander Smith College and am

currently in school at this time. I am in my First

year in Philander Smith College, a Freshman. On

March 10th I had occasion to visit Woolworth’s

store. I went to show the manager and the people

of Little Rock and State of Arkansas and of the

United State sthat we— I disapproved of the dual

service that he had in his store and if I was able

28

to buy one one side of the store I should be able to

buy on the other. I went to the lunch counter as a

patron there to show that, and sat down. I sat

down with my fellow students of Philander Smith

College, and the people that were sitting there be

fore I got there and they continued eating and the

lady that was sitting next to me, well, she finished

her food and she put her money on the table and

she left and all of a sudden I heard police sirens

and they came into the store and they asked some

people to leave the counter. They asked the white

people to leave first and then Chief Smith came in

and told us that the counter was closed and that

we would have to leave. Some fellow students got

up and left and I turned to leave and then I sat

back down. The counter was not closed at that

time to my knowledge. A waitress didn’t approach

me to serve me at any time. After I sat down again

I heard the police chief say that the counter was

closed, that I would have to leave or be arrested.

I don’t remember what officer it was, came to me

and he said the counter was closed, you have to

leave or be arrested and I said, “ Well, I guess I

have to be arrested.” I then left the store with the

police officer. As I left out of the store, leaving

the store, no one had their hands on us. We walk

ed out the door. As soon as I walked out the door

29

on the street, someone grabbed me by the seat of

the pants like he was putting something down the

back o f my pants and I turned around and I said,

“ Don’t put anything on me,” and that is the only

statement I made. I didn’t say “ Take your damn

hands o ff of me.” I said, “ Don’t put anything on

me.” I felt— in the other cities that these demon

strations have been going on, I had heard of people

putting things down in your pants, trying to put

weapons on you and put his hands on me of i f he

was putting something down in my pants. I was

afraid this might be occurring then. I felt I was

asserting my Constitutional right to be served in

a store when I took a seat at the counter. I was

not about to resist the officer in any way. While

sitting in the store, I didn’t make any threatening

gesture toward anyone. I wasn’t using any pro

fanity. I didn’t make any statement to anyone

other than the officer. Nobody in the crowd made

any threats toward me. I saw a crowd gathering

only after the police arrived. They came into the

store and started walking behind us and asked the

white people to leave the counter. The people that

were shopping there is about all was in the store

that day at that time. I didn’t see any kind of

crowd that seemed to be threatening.

I am in college as a first year student. Have

80

traded at Woolworth’s before, quite often, some

times two or three times a week. I have never sat

at the lunch counter before. I hadn’t observed

colored people sitting there before. I didn’t know

that wasn’t the custom then. I had not observed

them doing it. We don’t have a leader. There was

no meeting where I was instructed as to what to

do. It was just a volunteer t hing on my and other

student’s part. I got the idea from the students

demonstrations in North Carolina and other states.

I am not the leader of the group. I didn’t have a

meeting bef ore March 10 as to what I was going to

do and when. As I discussed to the students and

generally in groups they would be talking about

it. You would walk up to the fellows and they

would be talking about it. Nobody told me to do

this. I had discussed it since February. They are

picking on "Woolworth’s store all over the nation

to. This wasn’t a scheme to pick on stores in other

states. We didn’t pick on it. We sat down there

because they were sitting down in other states in

Woolworth’s. We selected stores where we trade.

We were not instructed or taught, nor encouraged

by the NAACP to do this, nor any of its officers.

No one seemed to be the leader among the stud

ents. I didn’t tell the officers I wanted to be ar

rested. I heard the officers say, “ The lunch count

31

er is closed.” The officers asked me to leave then.

I didn’t leave. I refused to leave, because I am an

American citizen and I didn’t feel I was breaking

any law. I just sat there I didn’t say that to the

officers. When I was sitting there people there

were just shopping in the store and after the police

arrived, the people seemed to be looking to see

what happened as far as I know. I sat down in the

store and looked at the menu and saw what I was

going to order. No one said anything to me. I

don’t know the exact number of us there. I walked

there with Chester Briggs. I know what I was go

ing to do when I got there. I went there in mind

to be served. I didn’t know that there was some

Acts o f our Legislature that made that against the

law. I went there in mind with Briggs knowing

that I was going to sit down at the lunch counter.

I don’t know how many were going to be there.

Other said they might go. I told the officer not to

put anything on me. I didn’t see the officer as I

stepped out the door. As I stepped out someone

grabbed me by the seat of my pants and I turned

around and said, “ Don’t put anything on me,” and

it was the officer. I meant by that I thought some

body was going to slip something on me. I wouldn’t

ordinarily go in a store with a weapon on me. I

was fearful that someone would put a weapon on

32

me because I have heard that this was going on in

other states, that they were putting things on

somebody. I read that in the newspapers. Not in

a meeting. I hadn’t been to any meeting. This was

not made a deliberate scheme. I might have seen

this in other instances or even from television I

was fearful that might be the result. I was seek

ing by peaceful means to persuade the manager of

the store that segregation is morally and legally

wrong. I didn’t anticipate disturbing the peace,

becoming violent or abusive or threatening in any

manner.

CHARLES PARKER, one of the defendants,

testified as follows: (Tr. 159-167)

My name is Charles Parker. I am a student

at Philander Smith College. I have been a student

at Philander Smith College for three years. I am

a Junior. I was present at Woolworth’s on March

10, 1960. Myself and a group of the other students

went to Woolworth’s to show the manager that we

were not in accord with his dual system of serving

us on one side of his store and refusing our service

on the other side of the store. While at Philander

I and other students at Philander have quite often

traded with Woolworth’s and we felt that we

should and we deserved to be served at the counter

SB

just as any other citizen of Arkansas of the United

States.

My purpose in going there was to peacefully

persuade the manager to treat me as he would his

other customers. I went and took a seat at the

counter. When I sat down, I sat next to some

white person and there was a large number of

white people, but who were eating when I sat down,

and they continued sitting down until the police

men arrived and told them they would have to

leave. At this time they hadn’t told the students

or the colored people to leave. They only told the

white people eating there to leave. Some of them

got up, but a man that was sitting next to me and

some other people finished eating what they had

been served and after they had finished they got

up and left. There was a waitress behind the

counter. She was doing something with some pies.

There was food on the counter. While sitting there

I looked over the menu, I was waiting to be served.

I didn’t at any time threaten anyone, or use any

profane language. Things were very quiet until

the policemen arrived with sirens blasting and a

lot of them came in. One officer, Officer Talbert,

came in and began pushing people. There were

some people who were objecting and there was a

group of people that was coming to the counter.

34

He pushed these people back and told them all to

move back. He kept going up and down the line

pushing and shoving. Some of the students who

got up from the counter remained on the scene

looking on and there was another group of people

that came in to see what the officers were doing

when they arrived. The officers didn’t say any

thing to me directly. It was my purpose to assert

what I considered to be a normal Constitutional

right. After we had been placed under arrest, we

were walking through the store out the side door.

None of the officers had taken a hold of us at that

time. Immediately after we walked out of the

store we were crossing the street. The officer that

was behind Mott — I was directly behind Mott,

grabbed Mott by the seat of his pants and Mott

said, “ Don’t put anything in my pants.” The man

ner in which the officer grabbed Mott, well, he had

Mott by his back pocket and I was supposing Mott

thought he was going to put something in his pock

et as he said. I saw him put his hands in his back

pocket. One officer said, “ You had better grab

him. He might run.” Mott said, “ Don’t put any

thing in my pocket.”

35

CROSS EXAMINATION

I have never been arrested, convicted of any

thing. I haven’t demonstrated, participated in any

sit-downs before this occurrence and I have not

participated in any sit-downs after this occurrence.

I would say that there wasn’t any leader. This is

more or less a spontaneous reaction by all students

being as how each of us had an obligation as citi

zens to try to get the rights that we deserve. We

hadn’t planned to do this at any time before March

10. There had been general discussion of this whole

problem of segregation before this sit-down demo-

stration in North Carolina, February and after.

I had only discussed this on campus. Since I am

not familiar with many places that are o ff campus,

most of my activities are confined to the campus.

It was strictly a student movement. I walked to

the store with Frank James. I didn’t go to demo-

strate I went to show the manager that I did not

like his policy of dual service. I had never seen

another Negro being served at his counter. Ap

proximately 30 of us sat down there. Everyone

left when the police asked them to leave except the

men that are here as defendants. There was no

type of agreement that all would leave except that

five. I did not know there was any law asserting

that we could not remain at the counter or we

would be punished if we did not leave, I heard the

police ask up to leave.

EUGENE D. SMITH, ET AL

vs. No. 4994

STATE OF ARKANSAS

PAUL TERRELL, Little Rock Police Depart

ment, witness for the State, testified as follows:

(Tr. 44-58)

Was working on April 18, 1960. On that

date, I made an investigation of an alleged act at

Pfeifers Store on Main Street in Little Rock, A r

kansas. Officer Talbert and Officer Phillips were

with me. We observed some Negro boys walking

the street in groups and noticed a lot of people fol

lowing them. We noticed them go into Pfeifer’s

Department Store, and I went in the store and the

lunch counter. Mr. Mitchell, manager of the lunch

counter and Officer Phillips were talking. I walk

ed over and talked to them at the lunch counter.

Six boys came in the store at different intervals

and walked around over the store looking at dif

ferent things, didn’t make a purchase as I saw.

They went to different departments. All came in

about the same time and began taking places at the

lunch counter at Pfeifer’s. They took different

37

intervals about the lunch counter. I was in civilian

clothes. One walked in and made a point to sit

between white ladies and Mr. Mitchell walked in

by him and asked them or told them “ at the pres

ent time we are not equipped to serve colored peo

ple” and asked them if they would please leave.

All left except, I believe him name is Jackson— the

boy with the gray suit on. He refused to leave.

He was sitting there with him hands up in the air

talking— he wanted to be served. There was quite

a commotion. I walked over and identified myself

as a police officer and told him he was under ar

rest and asked him if he would go with us and he

did. We taken him out and there was quite a com

motion there among the white people. I have their

names: Sammy J. Baker, Melvin T. Jackson, Win

ston Jones, McLloyd Buckannan, William Rogers,

Jr., Eugene D. Smith. We took these six defend

ants into custody. Officer Phillips went out when

he saw the commotion he went out with Lt. Talbert

and came in the door and met me at the lunch

counter and taken them in custody and brought

them to headquarters. I consulted another officer

and secured a warrant from the Prosecuting At

torney’s office. They were placed under charge of

Act 226, 1959. The defendants said they were

students of Philander Smith College. All lived at

38

Philander Smith, I think, except two. In addition

to Act 226 of 1959,1 secured a warrant on Melvin

T. Jackson on Act 14. It was about 11 :30 and the

lunch counter was quite crowded. They had sev

eral vacant seats. The lunch counter is more or less

in a horse shoe shape there and a number of peo

ple, mostly ladies, eating. I would say 25 of them

got up and left the place and walked back to see

what was going on. Some of them even left the

store. A lot of people gathered up, fifty or sixty

people gathered in to ask questions. Some were a

little bit angry. We took the boys out as soon as

possible without creating any trouble.

When I first saw the defendants, they were

going in the store. That is what caused me to go

into the store. We had some previous trouble and

were observing them at that time. Had no prior

arrangement or agreement with the manager o f

Pfeifer’s to come into the store when I saw the

Negro students come in the store. I observed these

students when they sat down in the store. They

were at the counter. Best I remember, the counter

is arranged more or less like a horseshoe. In other

words, comes out in a circle and dips back more or

less “ S” shaped. I do not know how many seats

or stools are there. Students were all together

when they came into the store. They split up after

39

they got in the store, walked by different places,

walked by the counters different places and looked

at things, didn’t ask questions whatever about buy

ing anything. They had split up different inter

vals. I am not too familiar with the store. They

were on the lower floor. They scattered out. I

can’t say what department. Am not too familiar.

I would say they covered around forty feet, differ

ent aisles, around the store. I watched them. They

didn’t make any purchases while in there. They

didn’t have anything when we arrested them. They

weren’t in there long enough to buy anything.

Melvin Jackson sat between two white ladies. He

made it a point to sit there because he passed sev

eral vacant seats which he could have set down on,

maybe two or three. I don’t know that all the de

fendants made a point to sit where they did sit.

They were picking different places. They were

walking around the counter and passed up some

places where there was vacant seats in order to sit

down by somebody. Some of the other defendants

sat by someone. I ’m not trying to arouse racial

prejudice by pointing out he made a point of sit

ting between two white ladies. He is the one who

refused to leave when Mr. Mitchell, manager of

the lunch counter, asked him to leave. I heard the

manager ask him to leave. He asked them in a

40

loud voice. He went to each one. I was walking

behind him, probably three feet. Some of them

were more or less together, maybe two or three to

gether. Then he would ask them or tell them “ At

this time we are not equipped to serve colored peo

ple” and asked them if they would please leave the

store, and they got up without any trouble. As

far as I know he got around to all of them. No

other colored persons seated at the counter, as I

know of. I am sure I would have seen them if they

had been there. I didn’t hear defendants saying

anything. When they sat down he walked over.

I wasn’t talking to them myself. Mr. Mitchell was

talking to them and asked them to leave. As far

as what they said I did not hear them say any

thing. They sat down at the lunch counter in my

presence is why I made the arrest. Except Mel

vin Jackson. As far as I could tell they weren’t

carrying on any loud talk, I could hear no offen

sive talk. I could not see that they appeared to be

intimidating anyone other than their presence

which caused quite a disturbance among the peo

ple eating. I made the arrest solely on my own

and not at the request of anyone. The defendants

were sitting at the lunch counter, is why I made

the arrest. That is all. All left when the manager

told them to leave except Jackson. I arrested the

41

other defendants because they had taken seats at

the lunch counter. According to the law, if a Ne

gro sat down at a lunch counter, he was guilty of

some crime. I would have arrested a white person

if he had sat down and caused a commotion. They

caused a commotion because they sat down and

about 26 different people pushed their plates back

and got up and left the lunch counter and began

talking. Only thing these defendants did in my

presence was to go in there and sit down. To me

they weren’t discourteous. They were to the peo

ple who got up and left only by sitting there. They

left immediately when requested to do so by the

manager. Jackson did not. He was talking to

himself “ I want to be served” “ I want to be serv

ed” . You could hear him seven or eight feet away.

I would say he remained there two or three min

utes. It was the time I had talked to the others

and asked them to come over there then I walked

over and identified myself to Jackson and he got

up and left when I asked him to. Mr. Mitchell was

the first one to ask him to leave. Mr. Mitchell had

on a white uniform, white shoes, white trousers.

I coudn’t say he did or didn’t identify himself. I

identified myself. The defendant left when I iden

tified myself and asked him to leave. Mr. Mitchell

had on a white uniform. He told them “ at the

42

present we are not equipped to serve colored peo

ple, will you please leave.” Numerous people got

up and left. There was a reaction from other pa

trons in the store and they came forward. They

wanted to know what we were going to do, and I

said “ just step back there.”

ERNEST M. PHILLIPS, Little Rock Police

Department, witness for State, testified as follows:

(Tr. 60-68)

Was working on the 13th of April, 1960. On

that date, I had occasion to assist in investigating

alleged offenses at Pfeifer’s main store at 6th &

Main in Little Rpck. Around eleven thirty or just

before, the man told me “you better go to Pfeifer’s,

it looks like trouble— I went over to Pfeifer’s these

boys were milling around in there. It wasn’t long

until Lieutenant or Captain Terrell came in. They

made the sit-down and I went over there to pre

vent trouble and wrhen they set down Captain Ter

rell said “go out and get— He is my commanding

officer” . I went out and got Lieutenant Talbert

and brought him in there and as I was coming in

Captain Terrell had them marching out, took them

out there on the sidewalk and then took them to

headquarters. I saw two sit down but I don’t

recognize but one of them today. This fellow Jack

43

son. He seemed to be the head man in the bunch.

He walked up to the counter and somebody got up.

I didn’t see but two sit down. There were several

about the lunch counter. I can’t identify any of

the others I saw sit down. I didn’t hear them talk

ing among themselves. When I went in frist they

were just milling around. Captain Terrell sent me

out for Talbert. I mean by ‘ ‘milling around” , walk

ing around different places, looking at different

places. Didn’t see them buy anything. When they

first came in they kind of stopped and had a talk.

Looked like four or five of them together when

they first came in. No one in particular seemed

to be doing the talking. They broke up and went

in different directions. Took a seat at the counter

just a few minutes later. The two I saw, one sit

down like here and the other one here. They were

a dozen seats apart. Jackson set down right at the

horseshoe and the other one went to the end of the

horseshoe. I wasn’t present when Captain Terrell

talked to them or Mitchell. Saw the defendants

when they went in the store. Saw two sit down.

They were scattered about the counter there. They

were not sitting down. I was there when they left.

Helped take them away. Captain Terrell had them

up bringing them out. I don’t know whether Cap

tain Terrell said anything to them. I wasn’t in

44

there when he was talking to them. He told me to

go get Lieutenant Talbert. I guess there were a

hundred stools on the two counters— swivel chairs.

All of them had backs. I ’m positive about that.

Have been a police officer about 25 years. Have

made numerous investigations as a police officer.

Arrival o f police officers at scene of an investiga

tion does not create a lot of curiosity and anxiety.

For one thing officers are supposed to keep the

peace. Most times a crowd gathers pretty much

any place the police are making an investigation.

I didn’t hear these boys carry on any loud talking.

They didn’t say anything. I didn’t see them do

anything I felt they should not have done other

than sitting down at the counter. All I saw they

just sat down at the counter. I was carrying out

orders when I assisted in the arrest. If these had

been white students sitting at the counter, and

they had created a disturbance, I would have made

the arrest. I saw two sitting at the counter. That

is the only thing they did to create a disturbance.

They violated the law, for a Negro to sit down at

a white counter. All I saw was the Negroes sit

ting down at the counter. I am 64. I don’t have

a regular beat. I have worked on Main Street sev

eral years. Have gone in and out of stores watch

ing crowds in stores over a period of years. The

45

patrons or crowd at Pfeifer’s seemed to be excited

when they were in there. They were expecting

trouble.

LIEUTENANT H. J. TALBERT, Little Rock

Police Department, witness for the State, testified

as follows: (Tr. 70-75)

Was working on April 13, 1960, and assisted

in the investigation of an alleged offense at 6th &

Main at Pfeifer’s store. The officers with we were

Phillips and Terrell. I pulled over to the curb at

6th & Main and parked. Officer Terrell got out

o f the car and went in the store and in a few min

utes Officer Phillips came out of the store. After

he came out, I got out of the car and went in the

store at his command. I saw Officer Terrell in

the store. When I walked in the front door and

started down the aisle. I met Officer Terrell and

six Negroes coming down the aisle. Five of them

there are in the court room today. I now know the

names of the defendants. I took the Negroes out

the front door and stood there and called the patrol

wagon. I sent them to Police headquarters. The

patrons in the store were milling around crowding

up and talking and asking questions. I had been

in the store where the arrests were made before.

The behavior of the crowd was out of the ordinary

46

that is why I took them out to the front to get them

away from other people. I did not go in the store

at first when Captain Terrell went in. Saw noth

ing that went on until Captain Terrell sent for me.

Don’t know anything about what happened in

there only after I got there and met him. At the

time I knew nothing at all. I was present in Mu

nicipal Court when they had a previous trial. It

was my testimony at that time that these people

were just standing on tip toes to see what was go

ing on. I observed the demeanor and attitude of

the crowd. I asked the crowd to stand back so I

could take the boys out of the store. I found that

necessary. I testified I took the boys out in Mu

nicipal Court. I testified I took the boys out and

the crowd was on tip toes trying to see what was

going on and I told them to get back. I don’t re

member that I made a statement in Municipal

Court I told them to get back.

W. T. MITCHELL, Manager of Pfeifer’s de

partment store, Little Rock, Arkansas, witness for

State, testified as follows: (Tr. 77-84)

I am Manager of P feifer’s Department store,

a business place in Little Rock. It is open to busi

ness and also was open to business on April 13,

1960. On that date, I observed the police appearing

47

there. Something happened to attract my atten

tion before the police got there. Well, there were

a few boys — these hoys here — they came in, but

they were not together. They were separated and

I guess they were to meet one another. I don’t

know. That is not for me to say. And they came

in and they stood around the card counter and

went back out, around the card counter. And they

left and in the meantime, Officer Phillips came in,

and I was talking to him and this Officer over here

— Officer Terrell came in and I was talking to

them and I went to use the phone, and while I was

using the phone these fellows came in. I’m talking

of the defendants. They sat down at various places

■— at the lunch counter. I am in charge and the

Manager. And as soon as I got o ff the phone they

all had not sat down when I got o ff the phone.

I went back, however, for my girls to close the

counter down. At that time a man jerked two of

these boys back before they got to sit down. I

don’t know the man. I didn’t get the man’s name.

He is not in the court. I don’t think I know his

name. I had never seen the man before. They

were not sitting. And I walked over to— well— one

of these— one or two of these fellows. I don’t re

member which ones. And I told them at that time

we are not equipped to serve them, and would they

48

leave. Most of them, I think, got up. There was

only one I see that sat there a little longer. I do

not know his name. Actually, I couldn’t identify

him this morning as to which one he was. The

police were— and they were talking then— begin

ning to take them out and things happened rather

— a little fast and I was unaccustomed to it and I

couldn’t tell you which ones they were. The best

I can remember all of them left except one. The

best I can remember all of them left except one,

when I asked them to leave. This had occurred in

my store before. When this happened it was at

our lunch hour, our noon hour rush; we were quite

busy and we do have a large crowd. Actually, I

was too busy to say what was the reaction as to the

attitude of the crowd. I didn’t point out the boy

to the officers who wouldn’t get up. I didn’t re

quest all of them to leave. I didn’t get around to

all of them. I don’t know which one refused to

leave. I couldn’t tell you one of these boys from

the other who sat down there. They weren’t dis

orderly in any manner. Were not loud. Were not

boisterous. Were not discourteous. Did not threat

en anybody. Didn’t try to intimidate me. Could

stop my business. Actually, the problem is this,

the fact that Negroes were at a white lunch count

er. Otherwise their demeanor was all right, as far

49

as I know. My lunch hour is from eleven until

one— until two. This happened around a quarter

of twelve. I have a larger crowd from eleven until

two o’clock than any other part of the day, ordi

narily.

JAMES FRANK LUPPER and

THOMAS B. ROBINSON

vs. No. 4997

STATE OF ARKANSAS

CAPTAIN PAUL TERRELL, Little Rock Po

lice Department, witness for the State, testified as

follows: (Tr. 83-42)

On April 13, 1960, we, Lt. Talbert, myself,

Officer Baer and Officer Thomas were at 4th &

Main, in front of Worthen Bank. It’s about 12

noon. Mr. Holt and Mr. Trianfonte came over

and identified themselves as being the manager

and assistant manager of Blass’ Department store

said they had some colored boys. They asked us if

we would assist them. We went over to Blass’ De

partment store and when we got inside the store,

just about 20 feet from the elevator, we observed

two Negro boys that they pointed out to us and

said they were the ones that had sat. It was in the

presence and hearing of the defendants. They

50

pointed out there two boys, said they were the ones

that— Thomas B. Robinson and Frank James Lup-

per. I asked them, or they said they were the ones

that had been in their lunch counter and sat down.

I asked Robinson in the presence of all o f us, Lieu

tenant Talbert, Mr. Trianfonte, Mr. Holt and my

self, if they were the ones that was at the lunch

counter. Robinson spoke up and said he was. Also

Lupper said he was also present and we arrested

them, brought them both to headquarters. Actual

ly their statement was made in the presence of

Lieutenant Talbert and m self, Mr. Holt. The

lunch counter there is upon the mezzanine floor,

the second floor. This conversation in their pres

ence was directly underneath the lunch counter.

They stated to me that they had sat at the lunch

counter. They stated to me that they had been

asked to leave. They stated to me that they had re

fused to leave. As to the demeanor of the patrons

in the store at the time I was talking to them, as

far as the lunch counter, I couldn’t say, but there

were several white people that followed them and

ganged up around us while we were talking to

them. There as sereval people walked up there

and asked what we were going to do, wanted to

know what was going on, you know, and so forth.

They asked several questions. I was in Municipal

51

Court when this case was tried. I ’m sure I testi

fied to all of that I said here. I don’t remember

just what I did testify there that they had ganged

up, that anybody had to be restrained. Lieutenant

Talbert was. with me. These boys were coming

out of the store, but they were orderly. Had no

reason to arrest them, except from the complaint

of the manager. He requested us to arrest them.

He had requested our assistance to get them out

from the lunch counter when he came over to get

us. He told us that he had two boys that had re

fused to leave the lunch counter and asked that we

assist them. I do not know that they did any of

these things except their word. They said they had

been up there and they had been asked to leave and

refused to leave. I ’m sure Officer Talbert was

standing near me. He was I think close enough to

have heard it. I would think he could have heard

what I heard. I couldn’t say whether he could hear

exactly what I did. I was talking to them. May

be he was talking to some of them. I couldn’t say

just exactly what he heard and what he didn’t. I

talked to both boys, asked both of them had they

been at the lunch counter and they said they had.

I asked each one individually. I asked them were

they the ones at the lunch counter and had Mr.

Holt asked them to leave. They said yes, that they

52

wanted to be served. They said they had been ask

ed to leave. They told me they had been asked to

leave. The time was twelve noon. There was a

large crowd in the store. I believe there was some

thing, I forget what it was, but anyway there was

a large crowd down town that day. I didn’t say

the defendants were leaving the store when I met

them, but they were leaving towards the elevator.

They were about halfway from here to you or may

be a little further from the elevator, but the ele

vator is in the center of the store. There was a

large crowd in there. They were coming from the

elevator which would have been going south from

the elevator. I couldn’t say going toward the south

entrance. There is an aisleway there. I couldn’t

say that they were going out of the store. There

were several aisles there. They could have been

going any direction.

H. J. TALBERT, Little Rock, Police Depart

ment, witness for the State, testified as follows:

(Tr. 43-49)

I assisted in the investigation at Blass’ De

partment store in Little Rock on April 13th. Two

men come running across the street on the corner

in front of the Worthen Bank. They told us they

were managers of the department store. We went

53

in the store, Captain Terrell and I. I observed two

Negroes coming down the aisle in the store, was

pointed out to me. The two men who complained

were with me at that time. These two boys on my

right, the two defendants pointed out to me are in

the court room today. I don’t recall their names.

We had had 12 or 15 that day. It was on the

ground floor. Captain Terrell and I both talked

to them. I asked the big boy there if he had been

sitting at the lunch counter and he said he did. I

asked him if he was asked to leave. He said that

he was. He said he refused to leave. I did not

question the other one as to whether he had re

fused to leave. It was between 11:45 and 12:00

o’clock. I would say, there was over a normal

crowd, a large crowd of people. I didn’t notice the

demeanor of the patrons of the store at that time.

I was present in Municipal Court. Captain Ter

rell talked to the boys and asked them if they were

at the lunch counter. They said they were. He

asked them if they refused to leave. One of them

said he did. The other one denied it to me. This

one here said he refused to leave. I believe this is

the one, this is Robinson. This big boy Lupper

reared up and pointed his finger at Mr. Holt and

said he did not refuse to leave. We put them un

der arrest and took them out of the store. That

54

was my testimony in Municipal Court, I think. I

don’t remember. I testified to what I had done.

I did not testify that both of these boys told me

that. That is not my testimony this morning. One

of them, Robinson said he refused. That one of

them is the one I talked to. We was altogether,

the two men, the two Negroes and Captain Terrell

was all standing in one bunch, and I could hear

what was going on and what was said. This big

boy is the one that said he refused to leave. We

was all standing there together, the two store

managers. As far as I knew and from what I ob

served these boys had done nothing for me to ar

rest them, only on what the men said. Just what

the manager said. They was coming down the aisle

when we stopped them. They weren’t bothering

anybody or weren’t molesting anybody. Weren’t

loud and boisterous. Their conduct wasn’t threat

ening to disturb the peace in any manner when we

stopped them. The big fat man on this end told

me he sat at the lunch counter and refused to leave.

A. F. BAER, Little Rock Police Department,

witness for the State, testified as follows; (Tr.

49-57)

I had occasion on April 13, 1960 with other

officers to make an investigation of an alleged of

55

fense at Blass’ Department Store in Little Rock.

I was with Lieutenant Talbert and Captain Ter

rell. I was working that beat at the particular

time. I observed that there was a group of Ne

groes that proceeded in the store that some went

in the front door and some went in the 4th Street

side and I knew that they were these sit-downers

they have been called because most of them had

their badges on and I followed them in and ob

served them sitting down upstairs. Robinson was

in the group of Negroes. I had seen him once or

twice before. I had come to recognize him, on ac

count o f his glasses and his build. He is the heavy

set on the right. I proceeded down and called head

quarters and advised them. They sent the Lieu

tenant and the Captain down there, talked to Mr.

Trianfonte of the Blass store. He advised us of

the situation there. We went into the store, walk

ed up to Lupper and Robinson. They admitted to

us that they had been upstairs and sat down and

that they were the two that had refused to leave.

When I observed these two defendants, I was up

stairs, in the eating place, the lunch counter, what

ever it is called. I would say between 12, 15, may

be more were sitting there or sat down there. I

am not sure. I wasn’t present when any person

working for the store approached and conversed

56

with them. When I came back outside from using

the phone and the wagon had driven up and sever

al police cars, they were beginning to come out. I

didn’t talk to any of them while they were sitting

at the lunch counter. I talked to the store em

ployee. I don’t know his name and he advised he

was waiting for the manager at the time. I didn’t

talk to the defendants other than advised them