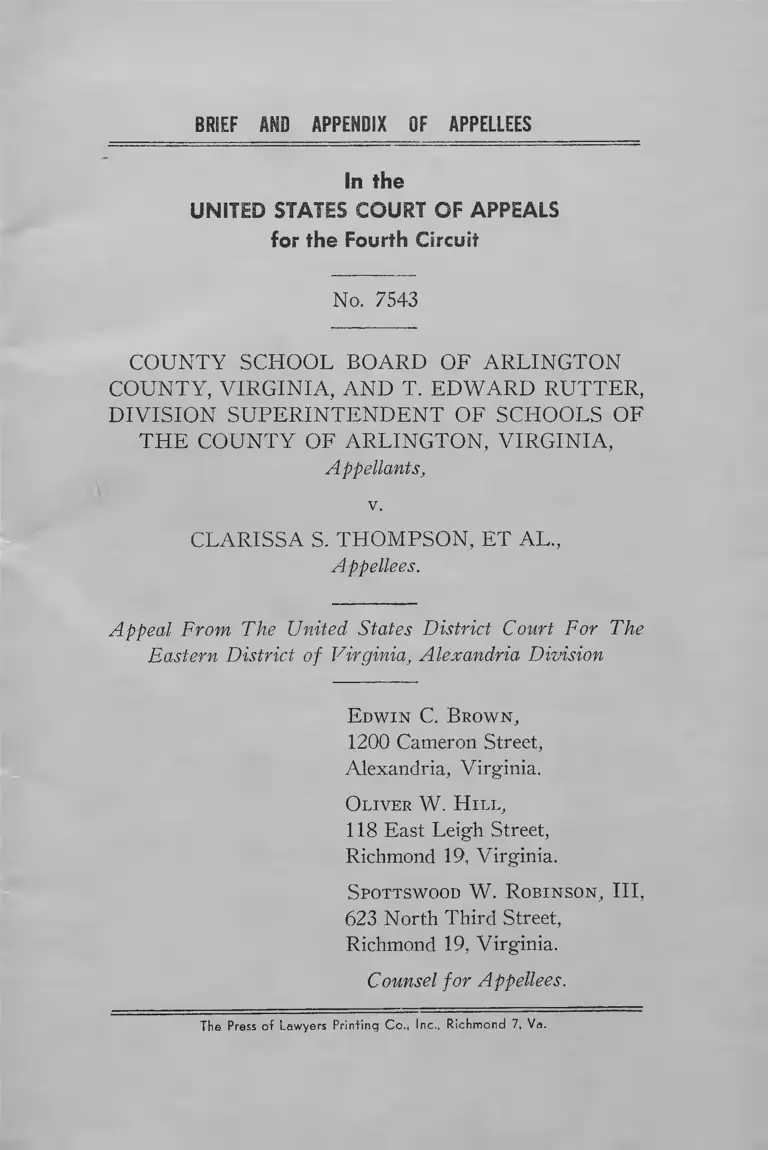

County School Board of Arlington County, VA v. Thompson Brief and Appendix of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 6, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. County School Board of Arlington County, VA v. Thompson Brief and Appendix of Appellees, 1958. 15b0ce6f-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/64c0c478-620d-4b3f-b3ce-a30265799d9e/county-school-board-of-arlington-county-va-v-thompson-brief-and-appendix-of-appellees. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF AND APPENDIX OF APPELLEES

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7543

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD O F ARLINGTON

COUNTY, V IRG IN IA , AND T. ED W ARD RU TTER,

D IV ISIO N SU P E R IN T E N D E N T O F SCHOOLS OF

T H E COUNTY OF ARLINGTON, V IRG IN IA ,

Appellants,

v.

CLARISSA S. TH O M PSO N , ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District o f Virginia, Alexandria Division

E d w in C, B row n ,

1200 Cameron Street,

Alexandria, Virginia.

O liver W. H il l ,

118 East Leigh Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

S pottswood W . R o bin so n , III,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

Counsel fo r Appellees.

The Press of Lawyers Printing Co., Inc., Richmond 7, Va.

SU BJECT IN D EX

Page

Brief On Behalf Of The Appellees ......................... .......... 1

Statement Of The C ase ....................................................... 1

Questions Involved................... .................................... ....... 3

Statement Of The Facts .......................................... .......... 4

Argument .............................................................................. 4

I. The Pupil Placement Act Did Not Justify Ap

pellants In Refusing To Admit The Minor Ap

pellees To The Schools To Which They Applied.... 4

II. The Pleadings And Proof W ere Sufficient To

Justify The District Court In Granting The Ap

pellees The Relief S o u g h t....... ....... 9

III. The District Court Properly Exercised Its Dis

cretion In Fixing September 23 As The Effective

Date Of Its Injunction .......................................... 16

IV. The Proceedings In The District Court Were

Consistent W ith The Federal Rules Of Civil Pro

cedure And The Rules Of The District C o u rt...... 19

Conclusion........................... ...................... .......................... 25

TA BLE OF C ITA TIO N S

Cases

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, F.2d (C. A. 4th, No. 7463, No

vember 11, 1 9 5 7 )........................................ .........18, 22, 23

American Brake Shoe & Foundry Co. v. Interborough

Rapid Transit Co., 3 F. R. D. 162 (S. D. N. Y.

1943) ................................................................. .......

Anderson v. Brady, 5 F. R. D. 85 (E. D. Ky. 1945)

23

20

Page

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 17

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) .... 24

Carson v. Warlick, 1956, 4 Cir., 238 F.2d 724 .............. 18

County School Board of Arlington County v. Thomp

son, 240 F.2d 59 (C. A. 4th 1956), cert, denied 353

U. S. 910 (1957 ) ................................................ 2 ,7 , 16, 18

County School Board of Chesterfield County v. Free

man, 171 F.2d 702 (C. A. 4th 1948) ......................... 17

DeFebio v. County School Board of Fairfax County,

[ Va. , December 2, 1957] ........................... 7

Lane v. Wilson, 306 U. S. 268 (1939) ........................... 17

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 5 Cir., 242 F.2d

156, cert, denied U. S. , 25 L. W. 3374 ..... 5

Quong W ing v. Kirkendall, 223 U. S. 59 (1912) .......... 17

Richmond v. Deans, 37 F.2d 712 (C. A. 4th 1930), aff’d

281 U. S. 704 (1930) ..........................................

School Board of Newport News v. Atkins, 246 F.2d

325 (C. A. 4th 1957), cert, denied U. S.

78 S. Ct. (Adv.) 83 (1957) ............................... .........

Tate v. Department of Conservation & Development,

231 F.2d 615 (C. A. 4th 1956), cert, denied 352

U. S. 838 (1956) .............................................................

Wilson v. City of Paducah, 100 F. Supp. 116 (W D

Ky. 1951) .........................................................................’

Wolpe v. Poresky, 79 App. D. C. 141, 144 F.2d 505

(1944), cert, denied 323 U. S. 777 (1944)

Statutes

Va. Code (1950), §§ 22-232.1 to 22-232.16.................. ;

Chapter 68, Acts of Assembly of Virginia, Extra Ses

sion 1956 8

Rules

Page

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 6 (d ) ................ 20

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 83 .................. . 21

Rules of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Rule 13 .... ............... . 21

IN D EX TO A PP E N D IX

Excerpts From Reporter’s Transcript

Robert A. Eldridge, Jr. ___ ____ ______ ______ ____ __ 1

Dorothy P. Nelson ..................................... ...... ......... ....... 5

A rthur M. Costley, S r..................................... ............ ....... 10

T. Edward Rutter .................................. ........... ........... . H

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7543

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON

COUNTY, V IRG IN IA , AND T. ED W ARD RU TTER,

D IV ISIO N S U P E R IN T E N D E N T OF SCHOOLS OF

T H E COUNTY OF ARLINGTON, VIRG IN IA ,

Appellants,

v.

CLARISSA S. TH O M PSO N , E T AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District o f Virginia, Alexandria Division

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLEES

ST A TEM EN T OF T H E CASE

On July 31, 1956, the District Court entered a decree in

this action enjoining racial segregation in the public schools

of Arlington County and making the injunction effective as

to elementary schools at the commencement of the second

2

semester of the 1956-57 school session and effective as to

secondary schools at the commencement of the regular 1957-

58 session (R. 179). On appeal, this Court affirmed the de

cree, County School Board o f Arlington County v. Thomp

son, 240 F.2d 59 (1956), and the Supreme Court of the

United States denied a writ of certiorari to review that de

cision. 353 U. S. 910 (1957).

The then plaintiffs in the action thereafter filed in the

District Court a motion seeking modification of the decree

by provisions (a) making the injunction/ suspended by the

appeal, effective as to elementary schools at the beginning of

the regular 1957-58 session and (b) specifying that the re

quirement, written into the decree, that administrative rem

edies be exhausted prior to further application to the Court,

did not necessitate compliance with the requirements sought

to be made by the Virginia Pupil Placement Act, Va. Code

(1950), §§ 22-232.1 to 22-232.16. (App. 1)*. The District

Court granted the first request but considered the second

prematurely advanced (App. 2-4), pointing out, however,

that “the July 31, 1956 decree recognizes only an adequate

administrative remedy—one that is efficacious and expedi

tious, even apart from any question of its constitutionality.

Pursuit of an unreasonable or unavailing form of redress is

not exacted by the decree.” (App. 3-4).

On September 9, 1957, three of the Negro plaintiffs and

their parents filed a motion for further relief (App. 5-6).

On the same day, four other Negro children and their pa-

* References “App. ----- ” are to the appendix of the appellants upon this

appeal. In an appendix hereto, appellees print additional excerpts from the

transcript of testimony. References to the record appear “R. - ”, those to

the transcript “T r . ----- ”, those to exhibits ‘ Ex. -----

3

rents filed a motion to intervene, accompanied by a proposed

complaint in intervention (App. 6-10). Each alleged timely

application for admission for the 1957-58 session to a pub

lic school theretofore attended by white children only and

the denial of such admission on the ground that the Pupil

Placement Act deprived appellants of authority to so admit

(App. 5, 9), and sought a further decree specifically direct

ing appellants to admit these children to the schools to which

they respectively applied (App. 6, 10). On the same day,

the District Court entered an ex parte order granting inter

vention and filing the intervention complaint (App. 12), and

another fixing September 11 as the date for hearing (App

11- 12).

At the hearing, appellants filed motions (a) to continue

the hearing on the motion for further relief (App. 15-16),

(b) , to vacate the order granting intervention (App. 16-17),

(c) to dissolve the injunction of July 29, 1957 (R. 235-236),

and (d) to dismiss the motion for further relief (App. 13-

15). The District Court overruled the first three motions

(App. 39-40) and, on September 14, made findings of fact

and conclusions of law (App. 18-25) and entered a supple

mental injunction decree in effect overruling the fourth mo

tion and granting the seven children the relief sought (App

26-27).

Q U ESTIO N S INVOLVED

1. Did the Pupil Placement Act justify appellants in

refusing to admit the minor appellees to the schools to which

they applied?

2. Were the pleadings and proof sufficient to justify the

District Court in granting appellees the relief soug'ht?

4

3. Did the District Court abuse its discretion in fixing

September 23 as the effective date of its injunction?

4. Were the proceedings in the District Court violative

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or the Rules of the

District Court?

STA TEM EN T OF T H E FACTS

In appellees’ view, the statement of facts submitted by

appellants is argumentative and omits vital factors estab

lished by the evidence. Since, however, the additional facts

are so interrelated to the decision of the legal issues, com

plete statements of the facts as to specific matters are, for

convenience, made in connection with the appropriate por

tions of the argument, and, to avoid repetition, are omitted

here.

ARGUM ENT

I

T h e P u p il P la c em en t A ct D id N ot J u st ify

A ppe ll a n t s I n R e f u s in g T o A d m it T h e M in o r

A ppe ll e e s T o T h e S chools T o W h ic h T h ey

A p p l ie d .

A

This appeal presents the third occasion upon which the

Virginia Pupil Placement Act, Va. Code (1950), §§22-

232.1 to 22-232.16, is asserted as a basis for resistance to

realization of the right of qualified applicants to nonsegre-

gated school assignments. When the Act was first here,

School Board of Newport News v. Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325

(C. A. 4th 1957), this Court ruled that applicants were not

5

required to pursue the administrative remedies it prescribed

because

. . this statute furnishes no adequate remedy to

plaintiffs because of the fixed and definite policy of the

school authorities with respect to segregation and be

cause of the provisions of chapter 68 of the Acts of the

E xtra Session, which provide for the closing of schools

and withdrawal therefrom of state funds upon any de

parture from this policy in any school. Orleans Parish

School Board v. Bush, 5 Cir. 242 F. 2d 156, 162, cert.

den. 25 L. W. 3374, ............ U. S .............. (at pp.

326-327).

This decision the Supreme Court of the United States re

fused to review. School Board of Newport News v. Atkins,

............U. S................, 78 S. Ct. (Adv.) 83, No. 361, Octo

ber 21, 1957). Upon the second such occasion, Allen v.

County School Board of Prince Edward C om ity,....... F. 2d

........ (C. A. 4th, No. 7463, November 11, 1957), this Court

again stated that “the Pupil Placement Act provides no ade

quate' administrative remedy.” And in the instant case the

District Court ruled that the Act provided appellants no de

fense against the relief sought. It said :

“The procedure there prescribed is too sluggish and

prolix to constitute a reasonable remedial process. On

this point we also rely upon the reasoning of the Court

of Appeals for this Circuit in School Board of the City

of Newport News, et al. v. A tkins et al., July 13. 1957

(App. 18-19).

" . . . the Court finds it cannot fairly require the

plaintiffs even to: submit their applications to the

6

[Pupil Placement] Board for school-assignment. The

reason is that the form prescribed therefor commits

the applicant to accept a school ‘which the Board deems

most appropriate in accordance with the provisions’ of

the Pupil Placement Act. Submission to that Act

amounts almost to assent to a racially segregated

school. But even if the form be signed ‘under protest,’

the petitioner would not have an unfettered and free

tribunal to act on his request. The Board still delib

erates, on a racial question, under threat of loss of

State money to the applicant’s school if children of

different races are taught there.” (App, 19-20).

We believe that the precedents established by this Court

are dispositive of the issue raised by appellants, and that the

District Court was clearly correct in its conclusion. While

A tkins involved the contention that the Act’s admini

strative remedies must be pursued, we think that it was

implicit in that decision that the attempted transfer of

school assignment powers would not benefit the local school

authorities. The provision of the Act undertaking to re

move those powers from local school boards and to place

them in the Placement Board was, of course, enacted legis

lation at the time of the District Court decrees in those cases

and at the time of the hearing and disposition of the appeals

here. There appears to be no suggestion, either in the briefs

or the opinions, that this displacement could be successful

unless the remedies themselves were adequate. It seems

quite anomalous that appellees could be deprived of their

constitutional rights on the ground that the only agency em

powered to grant them is an agency their remedies before

which are inadequate to afford those rights.

/

We cannot agree with appellants in their contention that

the issue is non-Federal in character and should await a

definitive decision of the Supreme Court of Appeals of V ir

ginia. It would perhaps suffice to point out that on De

cember 2, 1957, that Court decided DeFebio v. County

School Board of Fairfax County without ruling on the

point raised by the appellants here. But we consider that the

answer is even more fundamental. The provision seeking

transfer of the enrollment authority is not only a part of a

statute containing no severability clause, but is also inex

tricably bound to the remedies themselves. Indeed, the point

seems but the resurrection in slightly new form of the same

argument that was unavailing in the A tkins and case.

We do not have the simple question whether the state has

power to transfer the admission power from schools boards

to a central agency, but are again faced with the old question

whether these applicants are to be remitted to a procedure

before an agency that could not afford the relief to which

they are legally entitled. As we understand, this insistance

upon a state statutory bar to the exercise of a Federal right

necessarily presents a Federal question.

B

The rights of Arlington children to nonsegregated school

ing were judicially established prior to the enactment of the

Pupil Placement Act. Upon the first appeal in this action,

County School Board of Arlington County v. Thompson,

240 F. 2d 59 (1956), this Court had under review the de

cree whereby this was accomplished. The District Court

then provided:

“. . . it is further Adjudged, Ordered and Decreed

that effective at the times and subject to the conditions

8

hereinafter stated, the defendants, their successors in

office, agents, representatives, servants and employees

be, and each of them is hereby, restrained and enjoined

from refusing on account of race or color to admit to,

or enroll or educate in, any school under their operation,

control, direction, or supervision any child otherwise

qualified for admission to, and enrollment and educa

tion in, such school.” (R. 181).

As the Court knows, it was at the 1956 extra session of

the General Assembly that the Pupil Placement Act was

passed. It did not become law until the latter part of De

cember, 1956. Thus, as the District Court stated:

“It must be remembered that we are viewing the Act

in a different frame from the setting in which it was

tested by the Court of Appeals. The Act was then

appraised as an administrative remedy which had to

be observed before the persons aggrieved could seek a

decree of judicial relief. Now the Act is measured

against the enforcement of a decree already granted.

It is, too, a decree which was passed before the adoption

of the Placement Act and bears the approval of the

final courts of appeal.” (App. 19).

We submit that the prohibitions of the injunction could

not be avoided by the simple expedient of an undertaking to

transfer the assignment power from the school board to

the Placement Board. We think that the District Court

was eminently correct in its conclusion in this regard:

“The court must overrule the claim of the County

School Board and Superintendent that they should not

be held to answer for the denial of admittance to the

9

plaintiffs. In this they urge that the Placement Board

, had sole control of admissions—that the School Board

and Superintendent had been divested by the Act of

every power in this respect. As just explained, the

Placement Act and the assignment powers of the Place

ment Board are not acceptable as regulations or rem

edies suspending direct obedience of the injunction. In

law the defendants are charged with notice of these in

firmities in the Board’s authority. Actually the plain

tiffs were denied admission by the defendants’ agents—

the school principals—-while the defendants had the

custody and administration of the schools in question.

“Hence, the refusal by the defendants, immediately

or through their agents, to admit the applicants cannot

here be justified by reliance upon the Placement Board.

The defendants were imputable, also, with knowledge

that the injunction was binding on the Placement

Board. The latter was the successor to a part of the

School Board’s prior duties; as a successor in office to

the School Board, the Placement Board is one of those

specifically restrained by the injunction.” (App. 20).

See also Tate v. Department o f Conservation & Develop

ment, 231 F.2d 615 (C. A. 4th 1956), cert, denied 352 U. S

838 (1956).

II

T h e P leadings A nd P roof W ere S u f f ic ie n t T o

J u st ify T h e D istr ic t Court I n Gr a n t in g

A ppellees T h e R e l ie f S o u g h t .

The motion for further relief and the complaint in inter

vention each alleged that the children involved made timely

10

application to appellants for admission for the 1957-58

school session to a public school in the county theretofore

maintained for and attended by white children only; that

each such child was denied admission to such schools on

the ground that the Placement Act deprived appellants of

authority to admit such children to such schools; and that

defendants denied each such child who had not applied to

the Placement Board for assignment admission to any pub

lic school in the county (App. 5, 9). Each further alleged

that it would have been futile for any such child to apply

to the Placement Board in an effort to obtain a racially non-

segregated education (App. 5-6, 9-10). These allegations,

hardly disputed by appellants, are fully sustained by the evi

dence, and both allegation and proof, viewed in the light of

their factual antecedents, establish a deprivation of appel

lees’ constitutional rights solely on the basis of their race.

A

Arlington County maintains 4 schools for Negroes (Tr.

111-112, 113, 114) and more than 45 for whites (T r. 114-

115). Prior to the current school session, the school au

thorities had formulated boundaries of the areas, denomi

nated “districts,” to be respectively served by the various

schools, and admission to each school was restricted to

pupils residing in the district served by that school and, of

course, was further restricted by the practice of racial segre

gation.

There were 3 elementary and 1 secondary school districts

for Negroes (T r. 112-119, 123; PI. Ex. 8, 9 ). The Negro

secondary school district was unique in its division into two

geographical parts, not contiguous, the centers of which

were five or six miles apart, served by a combination junior-

11

senior high school, located in the southern portion of the

two-part district, which was and is the sole secondary facil

ity for Negroes in the county (T r. 112-113, 117-119; Ex.

8).

The classification of school districts as white or Negro

was purely a matter of race (T r. 119, 123, 124), and was a

long standing practice (T r. I l l , 131). The boundaries of

white school districts were fixed in terms of the capacity of

school buildings to house a given number of children (Tr.

119-120). To the extent to which a white school facility

could accomodate the children in that area, the' district

boundaries were arranged so that the white child could go to

the school nearest his residence.

Upon the opening of schools for the current session, the

school authorities followed instructions, issued by the Divi

sion Superintendent to principals of the various schools in

attempted compliance with the requirements of the Place

ment Act, to decline admission of any child who had not

applied to the Placement Board for assignment in any in

stance where the Placement Act required such application

(T r. 124-126). Principals were instructed not to assign

new pupils, or those graduating or seeking transfer from

one school to another; placement of all such children, if ac

complished at all, must be done by the Placement Board

(T r. 125). All other children were necessarily frozen in

the schools they previously attended (Tr. 133).

The county school authorities last formulated district

boundaries for use during the 1956-57 school session, and

presumably were adopted by the Placement Board in mak

ing the assignments it did for the current session (Tr. 132-

133, 134). It assigned more than 2,000 Arlington children

12

(T r. 128-129), and all schools remained segregated—act

ually attended by all-white or all-Negro student bodies (T r.

129-130). There is no known instance of an assignment of

any student of either race to a school attended by a student

of the other race.

B

In August of 1957, four of the five adult appellees en

deavored to arrange for the admission of their children to a

public school within the established school districts in which

they resided.

Appellee Robert A. Eldridge, Jr., after being advised by a

school principal that he would have to make application to

the Pupil Placement Board to secure the registration of his

son in an Arlington County Public School, went to the office

of the Arlington County School Board and endeavored to

see the Division Superintendent of Schools. He did see Dr.

Johnson, the Assistant Superintendent, and explained his

situation to him and was again advised that he would have

to proceed through the Pupil Placement Board. Mr. Eld

ridge then addressed a letter to the Division Superintendent

in which he detailed his previous experience and efforts to

get his son registered in school, advised the Superintendent

that he had not signed the pupil placement form, and re

quested that, in view of the decision of this Court concern

ing applications to the Pupil Placement Board, the Superin

tendent register his son in the public school nearest his home

or advise him where he could have him registered in such

school. (Ex. 3.) On each occasion when he sought to regis

ter his son he had available the son’s birth certificate and a

copy of his previous scholastic record. Fillmore Elementary

13

School is one block and a half from the Eldridge home and

the Hoffman-Boston School, a Negro facility, is four or five

miles distant.

Early in August, Mrs. Phyllis S. Costley, the mother of

Louis G. Turner and Melvin H. Turner, infant appellees,

procured a map of the Arlington County School districts

and, it appearing that the Swanson Junior High School was

the nearest junior high school to their residence, she then

attempted to have her sons enrolled in that school. The prin

cipal refused to enroll them. Mrs. Costley advised Mr.

Rutter, the Superintendent, of these facts and requested him

to have these children enrolled in Swanson Junior High

School or the junior high school nearest their home. (Ex.

6.) Swanson Junior High School is not more than three

quarters of a mile from the Costley residence and Hoffman-

Boston is about six or seven miles distant. On opening day

of school the children were again refused admission to

Swanson Junior High School, but subsequently on that same

day they were admitted to Hoffman-Boston High School,

without Mr. or Mrs. Costley ever signing a pupil placement

application.

On August 23, 1957, Mrs. Dorothy Hamm sought to

have her son, Leslie Hamm, Jr., enrolled in Stratford Jun

ior High School and was advised that application would

have to be made to the Pupil Placement Board. She and her

husband then went to Mr. Rutter’s office. They were unable

to see him personally, but were able to talk to him over the

telephone. Mr. Rutter told them that the only means of

registering the child was by signing the pupil placement

form. Soon thereafter, Mrs. Hamm wrote Mr. Rutter a

letter again requesting the enrollment of her son in S trat

ford Junior High School. On opening day of school, Leslie

14

Hamm., Jr. was again refused admission to Stratford Jun

ior High School. Neither Mr. nor Mrs. Hamm signed the

pupil placement form and at the time of the hearing Leslie

was not enrolled in any school. Stratford is about a half

mile from the Hamm residence and Hoffman-Boston is

about six miles distant.

About August 19, 1957, Mrs. Dorothy P. Nelson and her

son, George Tyrone Nelson, completed a pupil placement

application form and submitted it to Mr. Richmond, the

principal of Stratford Junior High School. They never

received any reply to the application. On opening day,

George Tyrone Nelson sought admission to Stratford Jun

ior High School and was denied. Stratford is a half mile

from the Nelson residence and Hoffman-Boston is six miles

distant.

Dr. Harold M. Johnson was the only one of the adult

appellees who did not make a pre-school effort to enroll his

children. He and his family had been away from the United

States from July 27, 1957, until the day before Labor Day.

He refused to sign a pupil placement form because he felt

that it would prevent his children from attending the school

nearest them and that even if he signed the form his chil

dren would not be accepted. At the time he applied to W ash

ington-Lee High School for the enrollment of his daughters

he had their promotion slips and scholastic records available

to hand over to the proper authorities.

C

In the foregoing circumstances, we submit that the Dis

trict Court was absolutely correct in finding and concluding

that

15

“Nothing in the evidence indicates that any of the

plaintiffs is not qualified in his studies to enter the

school which he sought to enter. Each applicant applied

to a ‘white’ school, but each lives in the district of that

or of another nearby ‘white’ school. Nor did the evi

dence reveal a lack of space for him, or that the school

did not afford the courses suited to the applicant. Coun

sel for the defendants explained that they did not ad

duce evidence as to the eligibility of the applicants for

their respective schools because this was a matter with

in the purview of the Placement Board. Anyway, no

intimation of disqualification appeared as to any appli

cant.

“A review of the evidence is convincing that the

only ground, aside from the provisions of the Place

ment Act, for the rejection of the plaintiffs was that

they were of the Negro race. The rejection was simply

the adherence to the prior practice of segregation. No

other hypothesis can be sustained in any of the seven

instances.” (App. 22).

Nor can the one assignment of the seven made by the

Placement Board be permitted to stand. George T. Nelson

filled out a placement application and submitted it to the

principal of Stratford Junior High School. The Placement

Board assigned him to Hoffman-Boston, and appellants

denied him admission to Stratford. His residence is one-

half mile from Stratford; Swanson Junior High School is

almost as close. But Hoffman-Boston is six miles away. As

the District Court concluded:

“The basis for the Board’s placement is not given;

no reason is evident for ignoring Stratford or Swan-

16

son. It cannot be accepted, for it is utterly without

evidence to support it.” (App. 25).

I l l

T h e D ist r ic t C ourt P roperly E xercised I ts D iscre

t io n I n F ix in g Se pte m b e r 23 As T h e E ffe c t iv e D ate

O f I ts I n ju n c t io n

The 1956 decree of the District Court commanded obedi

ence to all nondiscriminatory state and local rules affecting

public schooling and required the exhaustion of all suitable

administrative remedies. It was thus clear from the begin

ning “that the court was not attempting to direct how the

school board should handle the problem of assigning pupils

but was merely forbidding unconstitutional discrimination

on the ground of race or color.” County School Board of

Arlington County v. Thompson, 240 F.2d 59, 61 (C. A. 4th

1956). It was likewise clear from its July 27, 1957 mem

orandum that, while futile administrative remedies need not

be pursued, those “adequate,” “efficacious and expeditious”

must be utilized (App. 3-4). And in its September 14, 1957

opinion, it expressed regret that the Placement Act could

not be “utilized as a fair and practicable administrative

remedy.” (App. 19).

It is useless to contend, as appellants do, that the school

authorities did not mention race when admission was denied,

or that failure to apply to the Placement Board, rather than

race, was the reason for the denial. Arlington’s school sys

tem had previously been established on the principle of com

plete educational segregation. The decision that the school

authorities must not re-assign children was necessarily a de

termination not to depart from this practice unless so di-

17

l ected by the Placement Board. And it was the school au

thorities who barred the seven applicants from admission to

the schools they sought to enter, and relegated them to segre

gated facilities. Undoubtedly they would have been ad

mitted if white; and it is equally without doubt that they

were denied because they were not. As the District Court

said, “The rejection was simply the adherence to the prior

practice of segregation.” (App. 22). The Constitution ex

tends its protection where race is at the root of the action

as well as where it appears on the surface. Lane v. Wilson,

306 U. S. 268 (1939); Richmond v. Deans, 37 F.2d 712

(C. A. 4th 1930), af f d . 281 U. S. 704 (1930). See also

Quong W ing v. Kirkendall, 223 U. S. 59 (1912).

Nor are appellants excused by the consideration that they

assumed that they must await assignments by the Placement

Board. That they intended no deprivation of rights does not

justify. See County School Board of Chesterfield County v.

Freeman, 171 F.2d 702 (C. A. 4th 1948). As the District

Court put it: “I t is immaterial that the defendants may not

have intended to deny admission on account of race or color.

The inquiry is purely objective. The result, not the intend

ment, of their acts is determinative.” (App. 20-21).

It would be difficult to attribute to the District Court an

effort by its latest decree to administer the schools. It is

equally difficult to support the contention that injunction

should not enter without further opportunity to appellants

to reassign the appellee children. For although more than

three years had then elapsed since Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), and more than eight months

since the decision of this case on appeal in this Court, and

despite the previous injunction, appellants still adhered to

local public school segregation. Clearly something further

18

was warranted. County School Board of Arlington County

V. Thompson, supra; Allen v . County School Board o f Prince

Edward County, ........ F.2d ........ (C. A. 4th, No. 7463,

November 11, 1957). As the Court itself said:

“. . . the court must examine the evidence in regard

to each applicant and ascertain whether it indicates that

the denial of admittance was there due solely to race or

color. The court is not undertaking the task of assign

ing pupils to the schools. That is the function of the

school authorities and the court has no inclination to

assume that authority. Carson v. Warlick, 1956, 4 Cir.,

238 F.2d 724, 728. But it is the obligation of the court

to determine whether the rejection of any of the plain

tiffs was solely for his race or color.” (App. 21).

We submit that there was no further need or justification

for continued indulgence of the appellants. The only pros

pect for these children lay in a decree specifically directing

their admission to particular schools. Any other course

might well invite further delay and difficulty.

Nor do we perceive any reason why the date fixed by the

Court was not appropriate. We do not see in the admission

of seven children, appellants’ problems of “proper distribu

tion of school population into school districts, transporta

tion, efficient use of school buildings and personnel, and

others.” (Brief, 16-17). We concur in the judgment of the

District Court in this regard :

“The injunction will affect the school attendance

very slightly. Into a white school-population of 21,245,

only 7 Negro children will enter; 1 negro will be with

11,421 white children in the elementary grades; and

19

no more than 6 negroes among the 9,824 white high

school students. Of 36 previously ‘all white’ schools in

the County, 4 will be affected by the decree, and then

not to a greater extent than 2 negroes in any one of the

4 schools.” (App. 25).

IV

T h e P roceedings I n T h e D ist r ic t Court W ere

Co n sist e n t W it h T h e F ederal R u les O f C iv il

P rocedure A nd T h e R u les O f T ile D ist r ic t Court

The public schools of Arlington opened for the 1957-58

session on September 5. On that day the seven Negro chil

dren involved in this appeal sought admission to a public

school attended by white children only. Three of the seven,

E. Leslie Hamm, Jr., Louis G. Turner and Melvin H. Turn

er, were original plaintiffs in the action filed May 17, 1956.

A fter admission was denied, these three filed a motion for

further relief seeking “a further decree specifically direct

ing defendants to admit said plaintiffs to the schools to

which they, respectively, sought admission. . .” (App. 5-6).

The remaining four, as members of the class on behalf of

which the original action was brought, filed a motion to

intervene, accompanying their motion by a proposed com

plaint in intervention seeking the same relief sought in the

motion for further relief (App. 6-10).

The motions for intervention and for further relief were

filed September 9. (App. 5, 6). On that date, the District

Court entered ex parte an order g-ranting intervention and

filing the intervention complaint (App. 12), and another

order fixing September 11 as the date for the hearing (App.

11-12). Each order specifically directed that the Marshal

20

forthwith serve copies of the order upon the appellants, and

the Clerk to immediately mail copies to their counsel of rec

ord (App. 12, 13). That appellants actually received notice

of hearing- and the proceedings is admitted (Appellants’

Brief p. 10).

Rule 6 (d ) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure does

not impose a hard and fast requirement of five days’ notice

in all cases. Rather, it invests the Court with ample discre

tion in the premises. See Anderson v. Brady, 5 F. R. D. 85

(E . D. Ky. 1945). By its terms, it has no application to a

motion which may be heard ex parte and, in any event, au

thorizes the Court to make an order fixing a different period.

The instant case would seem clearly to be one in which the

Court might wisely shorten the five-day period. As the Dis

trict Court stated in overruling appellants’ objections to its

action :

“ . . . I think the motion to vacate the order of inter

vention should be denied. The intervention was allowed

immediately because interventions of this sort by a

person similarly situated are generally allowed. The

order permitting the intervention, of course, is always

subject thereafter to attack just as it has been attacked

today. But the immediate entry of the order did harm

to no one. The Court is also of the opinion that the

motion to continue should be denied. At the time the

order was presented to the Court to set this motion for

hearing, it was of the opinion either that the motions

had been served, or what would amount practically to

the same thing, that they would be immediately served.

Counsel for the plaintiff explained that he had not in

serted in the certificate the date of the hearing of the

21

motion because he did not know it, and I am sure that

counsel was of the same opinion as the Court was, that

the subsequent delivery of the motion the same day

practically would have the effect of antecedent delivery

of it. The Court was well aware of the five days’ rule

and practice but fixed a shorter time in view of the

known urgency of the situation; fixed it too, having in

mind that if there was any serious objection to the

time fixed, it could be changed on the motion. It is

always difficult in fixing time for hearing- in a case

where there are so many counsel. Frequently the Court

has to fix a date arbitrarily and then wait for objec

tions. It has also to bear in mind the circumstances of

the case, the circumstances of counsel, and circum

stances of its own docket. Here the Court believes

that no injury will be done by proceeding with this case,

but should any develop, why, the Court can then con

sider further deferment.” (App. 39-40).

It is not perceived how appellants can expect assistance

from Rule 13 of the District Court, and the claim that this

rule affects the issue here is not clear. Since appellees filed

statements of points and authorities in support both of the

motion to intervene and the motion for further relief (R.

212, 219), the suggestion seems to be that time limitations

suggested by the rule were not observed. Rut the District

Court rules were necessarily promulgated pursuant to Rule

83 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure granting Dis

trict Courts authority to make rules “not inconsistent with

these rules.” It would be vain to argue that Rule 13 of the

District Court rigidly imposes a requirement that Rule 6(d)

expressly permits all District Courts to vary.

22

Appellants’ claim to prior notice of granting interven

tion, and to opportunity to answer the intervention com

plaint, could have substance only if in fact the intervention

would be opposed, and the intervention complaint would be

answered. In Allen v. County School Board of Prince Ed

ward County, ........ F. 2 d ........ (C. A. 4th, No. 7463, No

vember 11, 1957), intervention was permitted, without ob

jection, on the date of hearing without any claim for an

opportunity to answer or any answer in fact (Appellants’

Brief, p. 3.) One of the counsel representing appellants in

this case represented one of the defendants there. And in

the very case now before the Court, a previous intervention

was permitted on the date of the hearing of July 31, 1956,

without objection, and without any effort to seek or make

an answer (Appellants’ Appendix, No. 7310, p. 9). Indeed,

the 1957 intervention complaint here presented no question

that the original complaint and the motion for further re

lief had not already made an issue in the case.

Nor do we think that there was any impropriety in the

manner in which the claims of the seven children were pre

sented and heard. The original proceeding, which was re

viewed here, was a class action (R. 3). The original injunc

tion, entered July 31, 1956, restrained the school authorities

from refusing, on racial grounds, the admission to any

school of “any child otherwise qualified for admission to,

and enrollment and education in, such school.” (R. 181).

The Court therein retained jurisdiction with power to en

large or otherwise modify the injunctive provisions (R.

182). Three of the seven children now before the Court on

this appeal were original plaintiffs, and the other four are

members of the class on behalf of whom the action was

initiated. Although the injunction imposed the requirement

that adequate administrative remedies be exhausted before

23

litigation, it is clear that, within this limitaton, those orig

inally parties plaintiff could appropriately seek further re

lief, and members of the class on whose behalf the action

was brought should be permitted thereafter to intervene in

order to participate in the benefits thereof. Wolpe v. Pore-

sky, 79 App. D. C. 141, 144 F.2d 505 (1944), cert, denied

323 U. S. 777 (1944); Wilson v. City o f Paducah, 100 F.

Supp. 116 (W . D. Ky. 1951); American Brake Shoe &

Foundry Co. v. Interborough Rapid Transit Co., 3 F. R. D.

162 (S. D. N. Y. 1943). See also Allen v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, ........ F.2d ........ (C. A.

4th, No. 7463, November 11, 1957).

The claims of each of the seven children presented com

mon questions of law and fact, and sought the same char

acter of relief. The only defense offered was that the Pupil

Placement Act had disabled the appellants from assigning

them, and the questions whether this defense was valid, and

whether the denials of admission were indeed a consequence

of their race, were the legal issues in each instance. The

only factual questions were whether the applicants were

qualified to enter the schools to which they applied, and were

denied admission thereto, and these were common to all

cases, and hardly subject to dispute. And in each case there

was sought a further decree specifically directing their ad

mission to those schools. Although the seven children were

presenting their individual grevances for determination,

their respective claims, objectives and interests were com

mon both to the main action and to each other. We submit

that the District Court correctly permitted intervention and

heard and determined these claims in the manner presented.

While appellants seem to now intimate (Brief, p. 11) that

they were precluded by the procedure adopted below from

24

offering evidence, the point does not seem to be well taken.

Efforts on behalf of five of the seven children were made

substantially ahead of the opening of the current session to

enroll them in particular schools, and there were both con

ferences and correspondence with the school authorities in

this regard (T r. 27, 28, 58, 80, 81, 98; Ex. 2, 3, 5, 6 & 7).

Then, and at the opening of this session, these efforts were

frustrated, not because of lack of qualifications, or lack of

space in the schools to accomodate them, but because of the

administrative determination that assignments were the

province of the Pupil Placement Board. There was ample

opportunity for the authorities to investigate these claims,

if investigation was indeed necessary, and to ascertain

whether there were additional reasons why they should not

be so admitted. More fundamentally, the appellants cannot

now support a claim to additional time to investigate even

tualities that under previous decrees they were already bound

to anticipate and prepare for. For the District Court to

have granted the request would have been to ignore “the

personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public

schools as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis,”

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300 (1955),

and “the known urgency of the situation.” (App. 40). It

would have been tantamount to deferring them to the next

enrollment date.

It seems evident that appellants are presenting contentions

as to developments that, in any event, produced no injury.

The District Court expressed this opinion at the outset, but

safeguarded their right to the protection of the Court should

it develop that their rights became jeopardized (App. 39-

40). It appears that no injury resulted, and certainly no

further request was made to the District Court for indul

gence.

25

The proceedings under review were not a new case, pre

senting novel questions, but rather were merely the latest

phase of litigation pending for more than a year and involv

ing issues and contentions well known to all. Indeed, on

July 27, just slightly more than a month before the Septem

ber 11 hearing, counsel had extensively argued the prin

cipal question in the case—the effect of the Pupil Placement

Act upon the Arlington situation. From the beginning ap

pellants have been represented by able and experienced coun

sel well versed in the law and quite capable of adequately-

representing the interests of their clients. We think they

did their job well, and now have no cause for complaint.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgments appealed from should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

E d w in C. B row n ,

1200 Cameron Street,

Alexandria, Virginia.

O liv er W. H il l ,

118 East Leigh Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

S pottswood W. R o bin so n , III,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

Counsel for Appellees.

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7543

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF A RLIN G TO N

COUNTY

Plaintiff

versus

TH O M PSO N , etc.

Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District o f Virginia, Alexandria Division

APPENDIX FOR THE APPELLEES

EX C ER PTS FROM R E PO R T E R ’S TR A N SC R IPT

Testimony of Robert A. Eldridge, Jr.

( tr 23) Q. Did you have any special reason for not sign

ing the form?

APPENDIX

2

A. I governed my action for two reasons. I had read in

( tr 24) the papers where the form itself had been con

sidered to be unconstitutional, and second, it appeared to

me that it wouldn’t be any use to fill out the form anyway

because I noticed that at one portion of the form it says

that it gave me the impression that the Board had the op

tion to send your student to any school that it so desired,

and it was my idea to have my child in the school nearest

to his home.

Q. That was your reason for not executing the form?

A. That’s right.

Q. If the Court please, we would like to offer into evi

dence the form that was given to Mr. Eldridge by Mrs.

Vance. Any objection?

T H E C O U R T : Is there any objection to it?

MR. BALL: No, sir.

T H E C O U R T : Let it be admitted.

T H E CLERK : Plaintiff’s No. 1.

(The Clerk so marked the form

as Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 1 in

evidence.)

MR. BROW N: Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 1.

BY MR. B R O W N :

Q. Mr. Eldridge, did there come a time when you pre

sented your child to any other school in Arlington County ?

A. Yes, I did on the opening day of school. I decided

to go to the nearest school to my house, which was a block

3

APPENDIX

( tr 25) and a half. I t is known as the Fillmore Elementary

School. It is located on Fillmore Street and I took my boy

there and I was met at the door by a Mrs. Smith, who told

me that I would have to— I think her reason, she told me

that I would have to go to the Clay Elementary School to

register my boy which was at—

T H E C O U R T : Have to go where?

T H E W IT N E S S : To the Clay Elementary School, lo

cated at Seventh and Holland Street, North Arlington. She

stated her reason for sending me there was because she

didn’t have any more placement forms, so I proceeded to

go to this school at Seventh and Holland Street where I

asked could I register my boy to go to the school nearest

his home, and I was told that I would have to fill out place

ment form.

BY MR. BROW N:

Q. W as this the opening day of school?

A. T hat’s right. A t that time I did take my, the birth

certificate of my child, and his former record of his school

that he previously attended.

Q. You had those with you?

A. On each occasion.

Q. Each occasion ?

A. Each occasion I had that with me.

* * *

( tr 27) * * *

Q. Mr. Eldridge, did you do anything else in order to

get your child into school ?

APPENDIX

4

A, Yes, I wrote a letter to the Superintendent. I wrote

a— I believe before that time I took my boy to theArling-

ton County Board and I asked to speak to Mr. T. R. Rutter,

the Superintendent of Schools concerning the matter. I

was told by a clerk there that Mr. Rutter was in a very

important conference but Mr. Johnson would be glad to

take care of me, a Dr. Johnson, rather. I went into the

office with Dr. Johnson. H e talked to me and I explained to

him that it was my desire to have my boy enroll in the

nearest school to his home. Dr. Johnson explained to me

that I would have to fill out a pupil placement form, that

there was nothing that could be done for me other than to

fill out the form. I did— I had written a letter previously

to—

Q. To whom?

A. Superintendent T. R. Rutter concerning the matter.

Q. Do you have, did you receive any response to that

letter ?

(tr 28) A. Yes, I did.

Q. Do you have that letter with you now ?

A. Yes, I do. That is the original copy and this is the

registered receipt that I signed for same.

Q. You mean this letter was sent to you by registered

mail from the Superintendent of Schools, T. R. Rutter ?

A. T hat’s correct.

Q. And this is in response to the letter you had written

to Superintendent of Schools?

A. That’s correct.

* * *

( tr 32) * * *

Q. Where is the Fillmore School in relationship to your

5

APPENDIX

home?

A, It is one block and a half from my house.

Q. One block and a half from your house ?

A. That’s right.

Q. How far is the Hoffman-Boston School from your

home?

A. Well, appear to be about four or five miles. It would

appear that way to me. I couldn’t say for sure.

Q But it is much farther than Fillmore School from your

home; is that correct ?

A. Very much so.

* * *

( tr 34) * * *

Q. And what is your race ?

A. Negro.

Q. That is all.

^

Testimony of Dorothy P. Nelson

( tr 56) * * *

Q. And how long have you lived in Arlington County ?

A. Seven years.

Q. Do you have any children of school age ?

A. Two.

Q. And did there come a time when you presented, did

there come a time when you presented one of your children

to the school for admission ?

A. Yes.

APPENDIX

6

Q. W hat was his name?

A. George Tyrone Nelson.

( tr 57) Q. And what is his age?

A. Fourteen years.

Q. Now is he in school at the present time?

A. Yes, he is,

Q. And what school?

A. Hoffman-Boston.

Q. Did he apply for admission to any other school to

your knowledge prior to going to Hoffman-Boston?

A. To Stratford Junior High.

Q. And was he given a pupil placement form to execute?

A. Yes. He filled out one, if that is what you mean.

Q. Speak up so the Court can hear.

A. He filled out a form from the, that he got from the

School Board.

Q. Did he fill out the form or did his parents?

A. Well, he and I together filled it out.

Q. Did you file that pupil placement form with the proper

authorities ?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And with whom did you file the form?

A. Mr. Richmond at, Principal of Stratford Junior High.

Q. And were you given any instructions to what you

should do thereafter ?

A. No.

Q. W ere you told what school he would be assigned to?

( tr 58) A. No.

Q. A fter you had filed this form, with Mr. Richmond,

7

APPENDIX

and you say you filed it with him at the school; is that

correct ?

A. Yes, we gave it to him.

Q. You gave it to him personally?

A Yes, sir.

Q. Have you received any response from it, that partic

ular form?

A. No, sir.

Q. None whatsoever ?

A. None whatsoever.

Q. When was it that you filed this form with Mr. Rich

mond?

A. I ’m not certain but it was either the 19th of August

or the 26th, but I am sure it was the 19th. I believe it was.

Q. In other words, it was before the opening day of

school; is that correct ?

A. (nodded.)

( tr 59) * * *

Q. W hat is the racial identity of your child?

A. Negro.

Q. Now what did you say your address was ?

A. 2005 North Cameron Street.

Q. And what is the nearest school to your home ?

A. Junior high school, you mean ?

Q. Yes.

A. Stratford.

Q. And about how far is Stratford from your home?

A. Approximately a half a mile.

8

APPENDIX

Q. And you’re familiar with Hoffman-Boston School,

are you not? You know about it?

A. Yes.

Q. About how far is that school from your home?

A. Six miles.

Q. Six miles.

W as your child presented to school on the opening day

of school?

( tr 60) A. Yes.

Q. And what school?

A. You mean the first school?

Q. Opening day of school?

A. Stratford.

Q. And was your child admitted ?

A. No, he wasn’t.

* * =1=

(tr 70) * * *

T H E C O U R T : How did you obtain the form that you

subsequently filed on August 19th, or 26th, with Mr. Rich

mond?

T H E W IT N E S S : My boy went to the Arlington County

School Board on Quincy Street in Cherrydale and obtained

it himself.

T H E C O U R T : And brought it back to you ?

T H E W IT N E S S : Brought it home and he and I filled it

out and we returned, took it back to Mr. Richmond at S trat

ford.

T H E C O U R T : Who took it back to Mr. Richmond?

T H E W IT N E S S : My son and I.

9

APPENDIX

T H E CO URT: Together?

T H E W IT N E S S : Yes.

T H E C O U R T : Did you have any discussion with Mr.

Richmond on that occasion ?

(tr 71) T H E W IT N E S S : No, I didn’t. I only asked him

one question.

T H E C O U R T : And what was that?

T H E W IT N E S S : I asked him if we, did he know if we

would be notified after the meeting about these, whether

the child would go to Stratford or just what they would do.

T H E C O U R T : A fter what meeting did you have in

mind?

T H E W IT N E S S : The meeting that was held in Rich

mond on the 29th.

T H E C O U R T : And did Mr. Richmond tell you that

you would or would not be notified ?

T H E W IT N E S S : He told me he couldn’t say because he

didn’t know if we would be notified or just what would be

the results of it.

T H E C O U R T : Now what was that, the last time that

you had any contact with the school ?

T H E W IT N E S S : W ith Stratford?

T H E COURT: Yes.

T H E W IT N E S S : Yes, first and last.

T H E C O U R T: Now what did you want to ask, Mr.

Brown ?

(tr 72) MR. B RO W N : I think it has been cleared up,

if Your Honor please. That is all. No further questions.

APPENDIX

10

T H E C O U R T : I understood she had already said that.

MR. BA LL: Just one minute. In view of what she said

—do you claim that you specifically asked in your applica

tion for admission to Stratford ?

T H E W IT N E S S : Yes.

MR. BA LL: You wrote that in the application?

T H E W IT N E S S : I didn’t write anything in the appli

cation. We only filled out what questions were on the form

to be filled in.

ifc ifc

Testimony of A rthur M. Costley, Sr.

* * *

(tr 82) * * *

Q. W here do you live, what section of—

A. I live in the section called, or near the section called

Hall’s Hill and that is in North Arlington.

Q. Northern section of Arlington ?

A. Yes.

Q. How far is that from Swanson?

A. Oh, I would say not more than, couldn’t be more than

three quarters of a mile.

Q. From your house to the Swanson School?

A. T hat’s right.

Q. How far do you live from Hoffman-Boston ?

A. Oh, about six or seven miles, I ’d say.

Q. W here is Hoffman-Boston located?

A. That is in South Arlington.

11

APPENDIX

Testimony of T. Edward Rutter

sfe sfe

(tr 111) * * *

Q. Your present occupation?

A. Division Superintendent of Schools, Arlington

County, Virginia.

O. How long have you occupied that ?

A. 1952 to 1957.

Q. Continuous?

A. Correct.

Q. Mr. Rutter, you are one of the defendants in the case'

that is now before the Court, am I correct in that regard ?

A. That is correct.

Q. How many schools are there, Mr. Rutter, in the Pub

lic School System of Arlington County ?

A. Approximately forty separate buildings.

Q. Would you name, would you first tell me the number

of schools that are attended entirely by Negro students ?

A. The number?

Q. The number ?

(tr 112) A. Of schools?

Q. The number of schools now attended entirely by

Negro students?

A. Four.

Q. All right. How many of these four schools are high

schools ?

A. One.

Q. W hat is the name of that school ?

A. Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School.

APPENDIX

12

Q. Now you say it is a junior-senior high school. W hat

grades does that school have?

A. Sixth through twelve.

Q. And which of those grades are junior high school

grades and which are senior high school grades ?

A. Six through nine are junior high school, and tenth

through twelve are senior high school.

Q. Now let me clear this up. Under your Arlington

School System the first six grades are elementary school

grades. Am I correct in that regard ?

A. That’s correct.

Q. And grades seven through nine are the junior high

school grades ?

A. T hat’s correct.

Q. And nine through twelve are the senior high school

grades ?

( tr 113) A. Right.

Q. That is true in both Negro and white schools?

T H E COURT: Ten through twelve, is it not?

T H E W IT N E S S : Ten through twelve.

MR. R O BIN SO N : I ’m sorry.

BY MR. RO BIN SO N :

Q. Is there any other Negro senior high school facility in

Arlington County other than a part of the Hoffman-Boston

facility ?

A. No.

Q. Is there any other Negro junior high school facility

in Arlington County other than a part of the Hoffman-

13

APPENDIX

Boston facility ?

A. No.

Q. Is Hoffman-Boston more than a single school plant

or is it within itself a single educational unit and in a sense

that it is a single building?

A. It is a single coordinated educational unit.

Q. How many buildings ?

A. Well, there is really one building, although we have

a temporary structure situated within about twenty feet of

the building so there actually are two buildings on the site.

Q. And what is this temporary structure being used for ?

A. Well, it has been used from time to time for various

( tr 114) purposes. I believe most recently for art and music.

Q. How temporary is this structure? By that I mean how

long has it been used for these various purposes ?

A. I don’t know the number of years but I can say it

has been used for this purpose since I have known the

school in 1950.

Q. Since 1950?

A. Yes.

Q. A t least for the period of the last six or seven years ?

A. Yes.

Q. All right. Now what are the names of the three re

maining Negro schools in Arlington County, all of which

are elementary schools?

A. The first is Hoffman-Boston Elementary School, lo

cated very close to the Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High

School. The other is the Drew Kemper School, composed

of two school buildings but is administered as one

elementary school, and the last is the Langston Elementary

School.

APPENDIX

14

Q. All right, sir. Now without undertaking to name them,

how many high school facilities do you have in Arlington

County attended exclusively at the present time by white

students ?

A. Two.

Q. W hat are the names of those two schools ?

A. Washington-Lee High School and Wakefield High

School.

( tr 115) Q. And how many presently all-white junior

high school facilities in the county ?

A. May I name them one at a time because I ’m not sure

that I can give you the exact number ?

Q. Surely.

A. In the northern part of the county we have Williams

burg, Stratford, Swanson; in the central part of the county

we would have Thomas Jefferson and in the southern part

of the county Kenmore, and a new junior high school pres

ently organized this year which will be known as the Gun-

ston Junior H igh School.

Q. How many?

A. I believe that was seven, was it not?

Q. Seven. Do you recall the exact number—

T H E C O U R T : Let us see. I have six, Williamsburg,

Stratford, Swanson, Jefferson, Kenmore, and Gunston.

T H E W IT N E S S : I ’m sorry. That is right.

T H E COURT: Six?

T H E W IT N E S S : I believe that is correct.

BY MR. RO BIN SO N :

Q. How many all-white elementary schools do you have ?

15

APPENDIX

A. I do not know the precise number, sir, but it would

be approximately thirty-seven or thirty-eight.

( tr 116) Q. All right, sir. Now, Mr. Rutter, are you

familiar with that map that is posted on the board over

there ?

A. Very familiar.

Q. Have you had an occasion to examine that map to be

in a position to tell me whether or not it is accurate in so

far as the location of your schools are concerned and the

boundaries, of the present boundaries of your school dis

tricts ?

A. I believe that it is, sir.

Q. Would you walk over to the map and examine it and

state to me positively, if you can, whether or not it does

accurately disclose the location of schools and school

boundaries ?

A. Yes, I believe that it does.

Q. How many school districts do you have as shown on

that map, Mr. Rutter ?

A, This map is an attempt to demonstrate and show the

number of secondary school districts. We have a similar

map showing the elementary districts.

Q. Might I ask you this. When you say secondary, do

you include only the senior high schools or do you include

the junior high schools as well?

A. That’s right.

Q. Junior high school, junior and senior ?

A. That’s right.

Q. All right. Now how would, how many senior high

school districts do you have?

(tr 117) A. Three.

APPENDIX

16

Q. Would you name them, please?

A. Hoffman-Boston, Washington-Lee and Wakefield.

Q. Are these school districts in each instance all located

in a geographically contiguous fashion or do you have any

instance of a school district being divided into two or more

parts and the parts not being geographically contiguous ?

A. We have one like the last you have just described.

Q. All right, and which one is that?

A. Hoffman-Boston.

Q. All right. W hat is the difference, if any, between the

school districts so far as the racial classification of the

student residing in those districts may be concerned?

A. The Hoffman-Boston District is designated as a dis

trict for our colored boys and girls on the high school level.

Q. And for that purpose only, am I correct?

A. That is correct.

Q. In assuming.

And that district I understand you to say has two parts ?

A. T hat’s correct.

Q. Would you show me those two parts?

A. (Pointed.)

( tr 118) T H E COURT: Would you refer to, for the

purposes of the record—call one of them north ?

T H E W IT N E S S : For the purpose of the record the

northern section is just south of Lee Highway, the southern

section is that portion of land surrounding the Hoffman-

Boston Junior-Senior High School.

17

APPENDIX

BY MR. RO BIN SO N :

Q. Now the Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School

is physically located within the southern of the two Hoff

man-Boston School Districts?

A. T hat’s right.

Q. There is no Negro junior or senior high school facility

geographically situated within the boundaries of the north

ern Hoffman-Boston School District?

A. T hat’s correct.

Q. How much distance would you say there is approxi

mately between the northern and the southern, say, esti

mating as best you can, from, say, the geographical centers

of those districts, how much distance would you say that

there is approximately between the northern and the south

ern sections of the Hoffman-Boston School District?

A. Well, I would judge it to be approximately five miles.

I believe the total distance from the northern part of the

(tr 119) county to the southern is seven and it would ap

pear to me would be about five, five and a half or six miles.

Q. Is there any other district in Arlington County at

the secondary level embracing Negro students other than

the Hoffman-Boston School District?

A. No.

Q. Now, and that is true with reference to the junior

high schools as well as the senior high schools ?

A. That is correct.

Q. Come back up here.

Now as I understand you, Mr. Rutter, the Hoffman-

Boston School District with its two parts for secondary

students is based entirely upon the race of the student re

siding for school administrative purposes within those dis-

APPENDIX

18

tric ts ; am I correct in that ?

A. I believe that is correct.

Q. All right. Now how do you figure out school districts

for white students at Arlington County ?

A. It is done in terms of the capacity of buildings to

house a given number of children.

Q. And by that you—well, suppose you explain just a

little more fully, if you will, just how you go about working

out the lines, the boundary lines of a school district for the

purposes of determining the schools to be attended by white

students ?

( tr 120) A. I think a good illustration to use would be the

construction of the Williamsburg Junior High School. As

that area of the community grew and it became evidence

that additional space was required for boys and girls of

junior high school age, plans were developed and eventually

a school building was constructed in that section of the com

munity. A very careful study was then made of the sur

rounding junior high school areas, specifically Swanson and

also Stratford. We then attempted to estimate the future

growth of the area to which I have earlier referred and

then determine what the boundary lines of the new junior

high school would be.

Q. Am I correct in concluding from what you have said,

Mr. Rutter, that the objective in formulating boundaries

of white high school and junior high school districts is to

the extent that the capacity of the school geographically

located in that district can accommodate students is to get

each white child to the school that is closest to the place of

his residence?

A. Not necessarily closest to his residence, because there

are a number of instances throughout the community when

that is not the case. In other words, it has been necessary

19

APPENDIX

in a number of instances I believe, in the past, of course,

to schedule boys and girls to schools that are not necessarily

the closest to their place of residence.

Q. But the reason for doing that is that the school that

( tr 121) is geographically located in that district doesn’t

have sufficient capacity to take care of all the students in

that d istrict; isn’t that the reason ?

A. That would be right.

Q. So that the extent to which a school facility for white

students can accommodate the children in that district, the

object in fixing these boundaries is to arrange it so that

the white student can go to the school that is the nearest

to the place of their residence ?

A. I believe that is correct.

Q. All right. Now, Mr. Rutter, do you happen to have

with you a map showing the elementary school districts of

Arlington County ?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Do you have one that we might—

A. Yes.

Q. Borrow from you for purposes of putting in the rec

ord in this case with the understanding that you might not

be able to get it back ?

A. Very good.

Q. All right, sir.

Anybody want to see this ?

Mr. Rutter, I hand you this document and I ask you to

examine it and state, if you will, what it represents?

A. This is a map of Arlington County on which has been

(tr 122) superimposed boundary lines indicating the various

elementary school districts.

APPENDIX

20

MR. RO BINSO N : If Your Honor please, I would like

to introduce this into evidence. Could we get it placed on

the board ?

T H E C O U R T : Before you do that, I think it would be

well to mark it with an appropriate exhibit number, the

map that is now on there, and let it appear that it is in

evidence. I take it there is no objection to it.

MR. R O B IN S O N : If Your Honor please, I just under

stand that the one that is on the board has never been in

troduced in evidence.

T H E C O U R T : I say it will have to be admitted now.

MR. R O BIN SO N : Oh, I see.

T H E C LERK : Plaintiff’s No. 8.

T H E C O U R T : Plaintiff’s No. 8.

T H E C LERK : You wish to mark this as plaintiff’s No.

9?

T H E C O U R T : Let the second map be plaintiff’s No. 9.

(tr 123) (The maps were so marked by

the Clerk as plaintiff’s Exhibits

No. 8 and No. 9, respectively,

in evidence.)

BY MR. RO BIN SO N :

Q. Now, Mr. Rutter, I say, ask you this, how many

elementary schools do you have ?

A. As many as we have school buildings against approxi

mately four.

Q. That means that you would have four Negro—

21

APPENDIX

A. T hat’s right.

Q. Elementary. No, would it be three?

A. Hoffman-Boston, Drew Kemper and Langston; three.

Q. In other words, you have a Hoffman-Boston Sec

ondary School District and a Hoffman-Boston Elementary

School District. You determine in each instance the bound

ary lines for elementary school districts like you determine

the boundary lines for secondary school districts; am I cor

rect in that ?

A. T hat’s right, fundamentally the same.

Q. In other words, the Negro school districts are deter

mined, the boundaries are determined entirely by reason of

the fact that the Negro student resides in the areas that are

surrounded by those boundaries ?

A. That is correct.

Q. You determine your white school boundaries in about

the same way, or precisely the same way for elementary

schools that you do for white secondary schools ?

(tr 124) A. True.

Q. Mr. Rutter, there has been considerable testimony

and some amount of correspondence introduced in evidence

coming from you indicative of a practice or policy on the

part of the school authorities in Arlington County to de

cline to admit any child to a school who has not made ap

plication for assignment to the Pupil Placement Board in

any instance where the Pupil Placement Act would require

that application to be made. Is that as a matter of fact the

policy and practice that was in effect on the opening date

of schools for the 1957-58 school session?

A. Yes.

Q. In writing the letters that you did, you were simply

APPENDIX

22

observing this policy, were you?

A. That is correct.

Q. And it was a policy established by the School Board

or Arlington County ?

A. No. I was attempting to follow to the letter of the

law the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Q. W ho formulated this policy, you or the School Board ?

A. Now I believe, sir, that we should distinguish between

policy and what the statutes of Virginia happen to be at the

present time. So that its always been our policy to observe

the law and I don’t, I would not take the position that the

Board of Education would have to formalize a policy to do

(tr 125) so. Therefore, what we have done this year is

what we have done in the past, obviously to observe the

law.