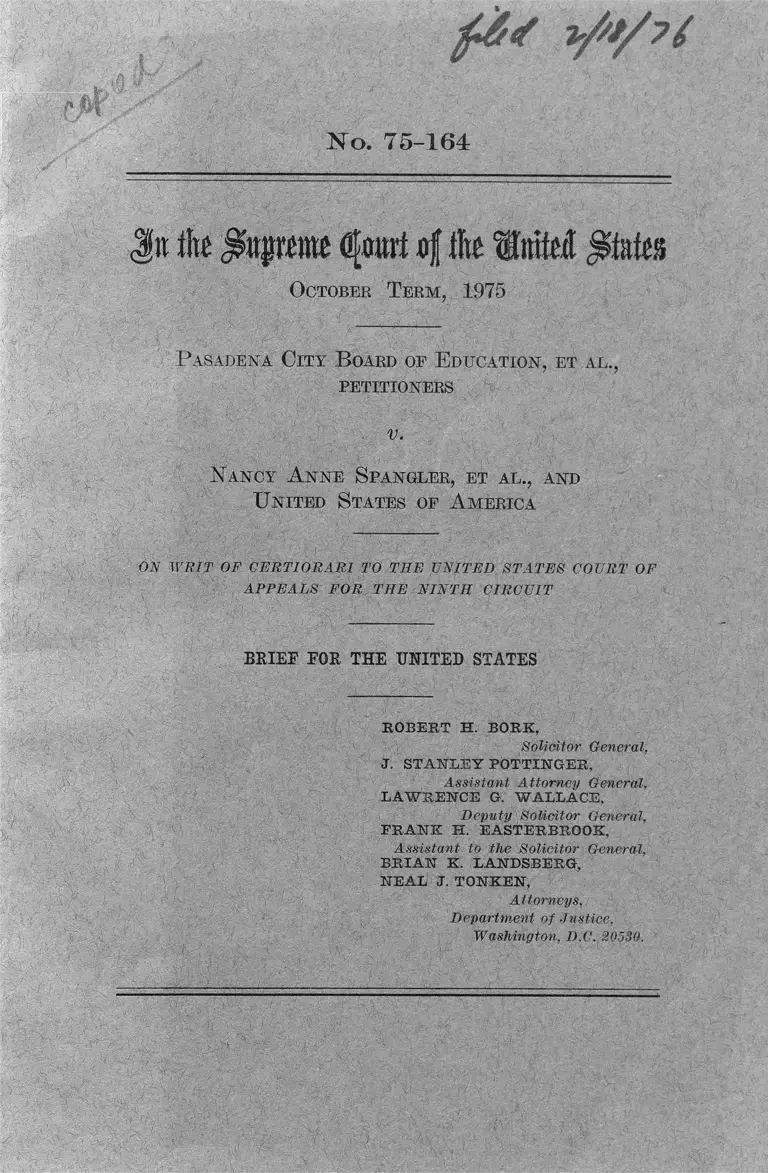

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler Brief for the United States

Public Court Documents

February 18, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler Brief for the United States, 1976. 93e8fc99-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/64fc1b43-24c3-42c9-9258-a17c465c5404/pasadena-city-board-of-education-v-spangler-brief-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

N o . 7 5 -1 6 4

<|« the fl̂ urt of ife Itititat States

October Term, 1975

P asadena City B oard of Education, et al.,

PETITIONERS

,'TI;

; Nancy A nne Spangler, et al., and

U nited States of A merica

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

R O B E R T H . BO RK ,

Solicitor General,

J. S T A N L E Y P O T T IN G E R ,

Assistant Attorney General,

L A W R E N C E G. W A L L A C E ,

Deputy Solicitor General,

F R A N K H. EAST E R B R O O K .

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

B R IA N K. LA N D SB E R G ,

N E A L J. TO N K EN ,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice.

Washington, D.C..205SO.

I N D E X

Opinions below____________ _____________________________

Jurisdiction_____________________________________________

Questions presented__________________.__ _________ ____

Constitutional provisions and statutes involved——___ ;_-

Statement: _________ _____________________ , - ___ -

A. Procedural history__________ __ ____________ _____

1. The desegregation proceedings__________ ■—

2. The present proceedings_:_________ ______ _

B. F acts_______ - ___________________________________

1. The district court’s 1970 findings of fact__

2. The Pasadena Plan and its implementation-

3. The proposed “ Integrated Zone/Educa-

tional Alternatives Plan”_- _____________

C. The district court’s opinion____________ - _________

D. The court of appeals’ opinions_______________ _____

Summary o f argument________________ _____________ ___J.

Argument: _- - __________ _____________________ __ A

I. The district court did not abuse its discretion by

declining to dissolve its injunction, terminate the

Pasadena Plan, or implement the proposed alter

native plan______ ________ _____ ___ __________ „■

A. Most of petitioners’ arguments are not

properly presented in the present posture

o f this case____________________________ .

B. The district court is required to retain juris

diction in a desegregation case until the

effects o f segregation have been elimi

nated and further discriminatory acts are

not a foreseeable possibility-__________

C. Continuous and active supervision by the

district court is necessary until it can de

termine with Confidence that the vestiges

o f segregation have been eliininated___

D. The district court properly rejected peti

tioners’ alternative plan— :_____

Page

1

.2

v 2

2

4

5

6

9

17

22

24

27

34

34

34

41

45

58

( i )

201- 038— 76----------- 1

CO

co

II

Argument—Continued

II. A desegregation case in which the United States v&ge

is a plaintiff cannot become moot__ __________ 65

Conclusion___________ ________________ ___________________ 68

Appendix ____________________________________ _________ 1a

CITATIONS

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U S . 19____________________________________ 42, 52, 68

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School District, 495 F. 2d,

499, modified, 496 F. 2d 1309___________________ _ 63

Board of School Commissioners y. Jacobs, 420 US'.

128_______________________________________ ___ 67

Brooks v. County School Board, 324 F. 2d 303________ 45

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U S . 483 {Brown

I ) ------------------------------------------ 1— ------------ 39,42, 54, 65

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U S . 294 (Brown

I I ) ----------------------------------------------------- 40, 42, 57, 65, 68

Brunson v. Board of Tmstees, 429 F. 2d 820_________ __ 55

Calhoun v. Cook, 451 F. 2d 583______________________ 56

Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F. 2d 717, rehearing denied,

525 F. 2d 1203____________________ ______________ 38

Garter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U S . 290__________________________________ .__ 42

Chrysler Coip. v. United States, 316 U S . 556_____ 47

Comstock v. Group of Institutional Investors, 335 U S .

211 -------------------------------------------------------- 54

Davis v. School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33_______ 39,47, 55

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U S . 479_____________ ____ 47

Goldberg v. Ross, 300 F. 2d 151______________________ 45

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U S . 683____________ 63

Green v. County School Board, 391 U S . 430__________ 28,

36, 42, 46, 47, 52, 59, 60, 61, 63, 68

Hart v. Community School Board, 512 F. 2d 37______ 62, 63

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189 on remand, 521 F. 2d 465, certiorari denied,

No. 75-701, January 12, 1976------------------------ 28, 36,53,63

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 455 F. 2d

978 ---------------------------------------------------------------------- - 56

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U S . 145_____________ 41

I l l

Cases— Continued

Lubben v. Selective Service System Local Board No. £7, page

453 F. 2d 645— ____________________ - _____________ 46,47

Mapp v. Board of Education, 525 F. 2d 169__________ 38

Mays v. Sarasota Coun ty Board of Public Instruction,

M.D. Fla., No. 4242, decided September 3,1975_____ 43

Millilcen v. Bradley, 418 IJ.S. 717_____________ 30-31,46, 54

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 IJ.S. 450_____ 55,

59, 60, 63, 64

Morgan v. Kerrigan, C.A. 1, No. 75-1184, decided

January 14, 1976_______________________________ 38, 55, 63

Northcross v. Board of Education, 412 IJ.S. 427_____ 68

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 IJ.S. 443____ 42, 52, 60, 68

Rizzo v. Goode, No. 74-942, decided January 21,1976 46, 56

Rogers v. / W . 382 IJ.S. 198________________________ ' 68

Steele v. Board of Public Instruction, 448 F. 2d 767:__ . 57

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecldenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1__ ______________________ __________ :__ passim-

System Federation v. Wright, 364 IJ.S. 642__________ 46

Tobin v. Alma Mills, 192 F. 2d 133 ________________ 45

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S.

173— —_____________________________ ____ 50-51,58-59

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educo

tion, 395 U.S. 225-------------------------------------------------- 51

United States v. Scotland Neck Board of Education.

407 U.S. 484______________ ______________________ _ 55

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106_ 31,46,47, 54, 56

United States v. Texas (San Felipe Del Rio Consoli

dated ISD), 509 F. 2d 192------------ -------------------------- 56

United: Stales v. Texas Education Agency (Austin

ISD ), 467 F. 2d 848_______________________________ 63

United States r. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629__ 30,44-45,67

Wailing v. IlamiscTifeger Corp., 242 F. 2d 712__ _____ 45

Wirtz y . Graham Transfer and Storage Co., 322 F. 2d

650 __________ 45

Wright v. Board of Public Instruction, 445 F. 2d

1397 _______ 57

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction, 448 F. 2d

770 __________ 56-57'

IV

Constitution and statutes:

Constitution o f the United States, Fourteenth Amend- Fnge

ment — _----------------------------------------------- _ 2,29,36,40, 64

Civil Rights Act o f 1964, Title IX , Section 902,78 Stat.

266, 42 U.S.C. 2000h-2____________________ 3,33, 65, 66, 67

Education Amendments o f 1974, Pub. L. 93-380, Title

II , 88 Stat. 514, et seq., 20 U.S.C. (Supp. IV ) 1701, et

seq :

20 U.S.C. (Supp. IV ) 1706__________________1___ 66

20 U.S.C. (Supp. IV ) 1707______________________ . 38

20 U.S.C. (Supp. IV ) 1718__:__________ _ 48, 56

42 U.S.C. 2000c(b)__________________________________ 67

42 U.S.C. 2000c-6_________ ._________________________ 67

Miscellaneous:

Bell, Wailing on the Promise of Brown, 39 L. and Con-

temp. Prob. 341 (1975)_________________________ .__ 65

Comment, Dissolution and Modification of Federal

Decrees on Grounds of Change of Attitude, 25 U.

Chi. L. Rev. 659 (1958)___________ _________________ 45

Comment, School Desegregation A fter Swann: A

Theory of Government Responsibility, 39 U. Chi. L.

Rev. 421 (1972) ___________________________________ 39

Fiss, The Jurisprudence of Busing, 39 L. and Contemp.

Prob. 194 (1975)_____________ _'_______________ 55

Goodman, De Facto School Segregation: A Constitu

tional and Empirical Analysis, 60 Cal. L. Rev. 275

(1972)---------------------------------- 39

Mills, The Great School Bus Controversy (1973)____ 39

Note, The Mootness Doctrine in the Supreme Court, 88

Harv. L. Rev. 373 (1974)__________________ _____ 67

Pettigrew, Racial Discrimination in the United States

(1975)---------------------------- 39

St. John, School Desegregation Outcomes for Children

(1975) ____----------------------------- 39

S. Conf. Rep. No. 93-1026,93d Cong., 2d Sess. (1974) __ 48

Symposium, The Courts, Social Science, and School

Desegregation, 39 L. and Contemp. Prob. 1-432

(1975) ____________-----------------------------------------____ 39

Tomlinson, Modification and Dissolution of Adminis

trative Orders and Injunctions, 31 Md. L. Rev. 312

(1971) 45

Jit litt $tt$mttt (Jfowvt »f itxt Kniicit pities

October Term, 1975

No. 75-164

P asadena City B oard of Education, et al.,

PETITIONERS

V.

Nancy A nne Spangler, et al., and

U nited States of A merica

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR TIIE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

O PIN IO N S B E L O W

The opinions of the court of appeals (Pet. App.

A1-A33) are reported at 519 P. 2d 430. The opinion

and order of the district court (App. 452-465) is

reported at 375 P. Supp. 1304. Other opinions in this

litigation appear at 427 P. 2d 1352, 415 F. 2d 1242, 384

P. Supp. 846, and 311 P. Supp. 501 (App. 3-4, 97-

133).

( i )

2

j u r i s d i c t i o n

Tlie judgment of the court of aq)peals was entered

on May 5, 1975. The petition for a writ of certiorari

was filed on July 30, 1975, and was granted on No

vember 11, 1975. The jurisdiction of this Court rests

upon 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

QUESTIONS P R E SE N TE D

1. Whether a school system automatically becomes a

“unitary school system’ ’ immediately upon compliance

with a desegregation plan developed by order of the

district court.

2. Whether the district court’s injunctive super

vision of the pertinent activities of a school system

that has engaged in racial discrimination should be

lifted before the school system has established that it

has been purged of the effects of that discrimination.

3. Whether a desegregation case in which the

United States has intervened as a plaintiff becomes

moot when the individual plaintiffs leave the school

system.

C O N ST ITU T IO N A L P R O V IS IO N S A N D ST A T U T E S IN V O L V E D

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution provides in relevant part:

No State shall * * * deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws.

The relevant statutory provisions are set out at

Pet. Br. A1-A18.

3

S T A T E M E N T

A. PROCEDURAL HISTORY

1. THE DESEGREGATION PROCEEDINGS

On August 28, 1968, several students in the pub

lic schools of Pasadena, California, and their par

ents filed a class action complaint seeking injunctive

relief from alleged unconstitutional racial segrega

tion in the district’s high schools. On November 19,

1968, the United States moved to intervene in the

case pursuant to Title IN, Section 902, of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 266, 42 U.S.C. 2G00h-2.1

The court granted the motion on December 6, 1968.1 2

The trial commenced on January 6, 1970, and the

court heard testimony for nine clays. On January 23,

1970, the district court entered a judgment holding

that the school system was segregated as a result of

the intentional acts and omissions of the defendants.

It enjoined racial discrimination throughout the school

district and directed the defendants to develop a de

1 The compaint In intervention “brought into the case the entire

Pasadena Public School system.” 415 F. 2d at 1243. It asked the

district court to enjoin further discriminatory practices at all

schools and to order the school board to develop and implement a

plan that would eliminate the effects o f past discrimination. Ibid.

2 On February 14, 1969, the district court granted the school

board’s motion to strike the allegations concerning elementary,

junior high, and special schools. On August 28, 1969, the court

o f appeals reversed and remanded with instructions to reinstate

the allegations. 415 F. 2d at 1248. It held that “ the district court

erroneously concluded that the UnitedJjtates was limited in the

relief it could obtain, to the relief souht bv the plaintiffs” (id.

at 1247). A

4

segregation plan under which no school would enroll

“ a majority of any minority students,” and under

which teachers and professional staff members would

be hired, assigned, and promoted on a non-discrimina-

tory basis (App. 3-4). An extensive opinion (App.

97-133) explaining the court’s decision was released

later.

The school board voted not to appeal the judgment

(App. 271-272) and, on February 18, 1970, filed its

proposed plan, the “Pasadena Plan” (App. 5-57).3 On

March 2, 1970, parents of other children attending the

Pasadena public schools sought to intervene for the

purpose of appealing (App. 453). The district court

denied the motion on March 4, 1970, and the court of

appeals affirmed. 427 F. 2d 1352, certiorari denied, 402

U S . 943.

On March 10, 1970, the district court approved the

Pasadena Plan (App. 96).4

2 . TH E PRESENT PROCEEDINGS

On January 15, 1974, the school board filed a mo

tion to dissolve the district court’s injunction or to

implement an alternative plan (App. 232-233). On

May 3, 1974, after a comprehensive hearing on the

3 Two weeks later the school board submitted an amendment

designed to reduce costs and to achieve more contiguous attendance

areas and better proximity to school facilities (see App. 58-95).

4 Certain amendments were proposed by the school board. After

the parties had agreed upon them, the district court approved

them in August 1970 (App. 134-136).

motion, the court denied the motion (App. 452-459).5

The district court denied petitioners’ motion for a

stay pending appeal.6 On May 5, 1975, the court of

appeals affirmed the judgment of the district court

(Pet. App. A1-A33).

B. PACTS

The Pasadena Unified School District includes the

city of Pasadena, the town of Altadena, the city of

Sierra Madre and portions of Los Angeles County

(App. 98). At its broadest points, the district meas

ures approximately 9.37 miles from east to west and

6.31 miles from north to south (see the map in App.

Rear Folio). As of October 5, 1973, its thirty-three

regular schools 7 and eight “ special” schools enrolled

25,414 students, of tvliom 11,188 (44 percent) were

white and 10,155 (40 percent) were black. 3,087

5 Evidence presented at the hearing showed that petitioners had

appointed five persons to administrative positions in July 1973

without following the procedures set forth in the Pasadena Plan.

Compare App. 51A-518 with App. 49-56. On August 12, 1974, the

court adjudged petitioners in contempt for having violated the

Plan in making those appointments. 384 F. Supp. 846. Petitioners’

appeal from that judgment was heard by the court of appeals on

November 5,1975.

0 We are lodging with the Clerk o f this Court copies o f petition

ers’ June 28,1974, motion for stay; of their memorandum of points

and authorities and affidavits in support thereof; and o f our

J'illy 12,1974, response and supporting memorandum.

* Fourteen “primary” (grades K -3 ) schools; eleven “ elemen

tary” (grades 4-6) schools; four junior high schools (grades 7-8) ;

and four high schools (App. 413-417).

6

students of Spanish origin made up the majority

of the remaining 16 percent (App. 417).

1. THE DISTRICT COURT’S 19 70 FINDINGS OF FACT

The district court found that the Pasadena school

system had been unconstitutionally segregated for

fifteen years because of the acts and omissions of the

school board (App. 97-126). It expressed the appli

cable legal standard as follows (App. 128) :

A violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

has occurred when public school officials have

made a series of educational policy decisions

which were based wholly or in part on consid

eration of the race of students or teachers and

which have contributed to increasing racial

segregation^] in the public school system.

The court observed that, in the preceding fifteen

years, Pasadena had experienced a high degree of ra

cial separation, especially in its elementary schools.8 9

8 Although the court used the terms “ racial segregation” and

“ racial imbalance” interchangeably in its findings and conclusions

(App. 99, n. 4), the findings and conclusions expressly recognize

a distinction between ude facto or adventitious segregation” and

the situation presented this case, in which “ the existing segrega

tion o f pupils and teachers is inseparable from the discriminatory

practices and policies of the defendants” (App. 132).

9 In each of those years, more than 90 percent o f the district’s

white elementary-age children had attended majority-white

schools, while more than '50 percent o f its black elementary-age

children had attended majority-black schools (App. 100). During

the 1969-1970 school year, 85 percent o f the district’s black elemen

tary-age children attended its eight majority-black elementary

schools, and 93 percent o f its white elementary-age children at

tended the remaining elementary schools (App. 99); o f the 30,622

students then enrolled, 9,173 (30 percent) were black (App. 98);

but thirteen o f the district’s elementary schools were less than five

7

The United States presented extensive evidence, and

the district court made detailed findings, that this sep

aration had resulted, in large measure, from a series

of deliberate actions by the school board.

a. The court described a series of racial gerryman

ders and manipulations of student assignments de

signed to avoid assignment of white students to near

by majority-black schools and designed to confine most

blacks to such schools (App. 100-109). The court

found, for example, that although the school board

often had changed attendance zones in order to com

bine areas of predominantly black attendance (App.

102-103), it had never since 1954 “ made an attendance

area change that involved assigning students from a

majority white residential area to a majority black

school” (App. 100).

b. The court gave examples of the transportation

of white students past under-enrolled majority-black

schools to more distant (and often overcrowded) ma

jority white schools (App. 100-104, 109, 122-123).

c. The court found that the school board had

“ granted transfers that they knew or should have

known were wholly or at least in part motivated by

racial considerations, including baseless transfers that

had the effect of intensifying racial segregation in the

Pasadena schools” (Ajjp. 125).10

percent black in enrollment, two were more than 90 percent black,

three were more than 80 percent black, two were more than 60 per

cent black, and another was 59 percent black (App. 99).

10 The school board also experimented with a variety of “ open

enrollment” and “ free choice” plans of student assignment (App.

8

cl. The court found that the school board had a

“ policy and practice of assigning most black teachers

to black schools” (App. 116) and that it also dis

criminated in the hiring of black teachers and admin

istrators (App. 112-118). Some identifiably white

schools had never been assigned a black teacher or

administrator (App. 112). Other schools had been

assigned only one. The court found that the school

system had hired only one black nurse, who was as

signed to predominantly black schools (App. 114).

Officials assigned black substitute teachers to majority-

black schools and allowed white substitute teachers

to avoid teaching at identifiably black schools (App.

113-114), and they assigned less experienced teachers

with less education to majority-black schools more fre

quently than to majority-white schools (App. 114).

e. The court found that the school board planned

the construction of new facilities, additions, to exist

ing facilities, and the placement of transportable, class

rooms in a manner that contributed to racial segre

gation (App. 103, 119-123). The school board selected

both the location and the capacity of new schools in a

manner calculated to ensure that each new school

105-106, 150, 151, 153-163, 113-197, 198-216, 217-220, 222-223,

225-231) that, “ until 1968, permitted a small number of both

black and white students to escape Negro schools” (App, 106).

None of these experiments diminished the racial separation that

had been created, in part, by other school board actions (App. 106,

137-149, 165-172, 193-195, 197, 198-200, 209-216, 221-227). Nor

did a “ free choice” summer school experiment in 1973 (App.

510-511).

9

would be racially imbalanced at its opening. Several

of these schools were abnormally small, apparently in

order to serve only a single, racially-identifiable

neighborhood (App. 120). When a small school in a

black neighborhood became overcrowded, the school

board added several transportable classrooms; a

nearby school with overwhelmingly white enrollment

was not used to capacity (App. 103, 121-122). The

same pattern was followed in building permanent

additions to schools in black neighborhoods (App.

121).

2. THE PASADENA PLAN AND ITS IMPLEM ENTATION

a. The Pasadena Plan “ represents the work and

thinking of the Pasadena City Board of Educa

tion, the superintendent, and the [school district]

staff under his direction” (App. 9). Its student as

signment provisions were designed to comply with

the district court’s mandate that no school have an

enrollment of which any one minority group consti

tutes the majority (App. 9).11

The Plan divides the elementary schools of the

district into four “ ethnically balanced areas,” each

served by a number of “primary” (grades kinder

garten (“K ” ) to 8) and “upper grade” (grades 4-6)

schools (App. 9-10). The Plan reorganized Pasa

dena’s traditional elementary (K -6) schools into

separate K -3 and 4—6 facilities in order to enable the 11

11 The Plan also includes detailed procedures for the hiring and

promotion of teachers and administrators (App. 47-57).

10

school system to “ provide specialization which is im

portant to guarantee improvement in basic skills.” 12

The reorganization also facilitates retention of “ neigh

borhood” schools by allowing students to “ walk to

a nearby school for part of their elementary school

ing and be transported with students in their neigh

borhoods to another school” for the other part (App.

10). The district’s junior high schools serve grades

7 and 8 (App. 27); its senior high schools serve

grades 9-12 (App. 134).

The Plan allows students to transfer from their

assigned schools to other schools in situations of “ur

gent hardship” involving “ family circumstances and/

or medical, safety, psychological, or curriculum con

siderations” (App. 35). The school district provides

transportation of “ all pupils attending schools outside

their normal areas” (App. 45). The Plan contem

plated the need for continuing evaluation, modifica

tions and adjustments in attendance zones and stu

dent assignments in order to achieve and maintain

suecesful integration (App. 9, 10, 27, 37).

b. Pasadena’s white enrollment had been declining

for many years (App. 347-348, 379, 421, 600, 601).13

12 App. 10. Superintendent Cortines, responding to questions at

a public meeting o f the school board on January 15, 1974, stated

that the majority o f his administrative staff preferred the K-3,

4-6 grade structure (App. 584).

13 In 1984, for example, 21,695 white students were enrolled in

the district’s public schools; in 1986, 20,958; in 1968, 19,008; and

in 1969,17,859. In 1970, the year in which the Pasadena Plan was

implemented, the number was 15,647. White enrollment continued

to decline after 1970 but at a steadily decreasing rate. See App. 421.

11

The school board submitted evidence that this decline

accelerated during the twelve-month period prior to

implementation of the Pasadena Plan (App. 421, 601)

and asked the court to infer that the pending imple

mentation of the Plan was the sole cause of this.14

The United States presented evidence showing that

the decline in white enrollment was not necessarily at

tributable to the school system’s desegregation efforts

(App. 386-387, 393, 531-543).15 We presented a study

of ninety-one California school districts, including de

segregating systems, which revealed that “ those dis

tricts that decline[d] the most in white enrollment

were districts that were becoming more segregated

rather than desegregated” (App. 561).

Evidence introduced by the plaintiffs and the United

States disclosed that many factors may have con

tributed to Pasadena’s loss of white students (App.

377-379, 505). These factors included the declining

birth rate and an economic retrenchment that had di

minished the availability of employment in the Pasa

dena area. The evidence indicated that some of the loss

in the months prior to implementation of the Pasa

dena Plan could have been anticipated (App. 393,

540-542) because the trend of declining white enroll

ment in Pasadena had closely paralleled the Califor

nia statewide trend for several years (App. 393, 505),

14 See Tr. Feb. 28, 1974, at pp. 493-541.

“ Henry Marclieschi, then president of the school board, stated

at the December 18, 1973, meeting of the board that “ it would be

folly to blame all of this drop [in white enrollment between 1970

and 1973] to [si'c] the Pasadena Plan” (App. 298).

12

and that school district employees who developed the

Pasadena Plan were aware of the trend at that time,

in fact anticipated its continuation under the Plan,

and took account of it in preparing the Plan (App.

508-510).16 In addition, evidence demonstrated that

following implementation of the Pasadena Plan the

district’s racial composition began to stabilize (App.

325, 380).17

The district court resolved the conflict in the evi

dence by concluding that there was no proof that

any “ white flight” was attributable to the Plan (App.

454). The court of appeals did not disturb these find

ings. See Pet. App. A8 (opinion of Ely, J . ) ; id.

at A26 (Wallace, J., dissenting).

In subsequent proceedings petitioners have pre

sented evidence “ that if the school district is per

mitted to maintain the status quo in the assignment

of students under the Pasadena Plan, the ethnic

changes that are occurring at the present time

throughout the school district will stabilize and the

ethnic imbalance now being experienced in grades 4

through 8 will disappear” (June 28, 1974, Affidavit

10 The school board acknowledged in the Pasadena Plan itself

the district’s history of white enrollment decline and black enroll

ment increase (App. 8) ; the Plan provided that “ minor modifica

tions and adjustments” ih student assignments might be necessary

in the future (App. 9).

17 See also App. 476 (former school board president Henry

Marcheschi testifying that “ what we are experiencing now is no

longer a phenomenon o f white flight but one o f white boycott” ).

13

of Peter F. Hagen, at p. 4).18 This prediction now

has been supported by testimony given during pro

ceedings subsequent to the decision of the court of

appeals. During a hearing on September 15, 1975,

concerning the conversion of a “ regular” K -3 school

to a “ fundamental” K -3 school, school board presi

dent Dr. Henry S. Myers, Jr., testified (Sept. 15,

1975, Tr. 16) :

We had a large increase in enrollment last

year, about 600 more students than we had the

year before. This year I have done a lot of

preliminary checking, and all of our principals

report significant increases of enrollment—pre

enrollment, pre-to-school opening. It is entirely

possible that we have reversed the flight, the

white flight, if you will, from Pasadena and

have a significant amount new enrollment.

18 In affidavits dated December 19, 1973, and submitted in sup

port o f petitioners’ January 15, 1974, motion for relief, Mr. Mar

cheschi and Superintendent Ramon C. Cortines stated that de

creasing white enrollments and increasing minority enrollments

would make it a “ practical impossibility” to comply with the Pasa

dena Plan in the future (App. 236, 237). In an affidavit filed by

petitioners in support o f their June 28, 1974, motion for a stay of

the district court’s judgment, however, Peter F. Hagen, the dis

trict’s administrative director for planning, research and develop

ment, directly contradicted the Marcheschi and Cortines affidavits.

Based on his post-trial analysis o f demographic and enrollment

data compiled by district employees, Mr. Hagen predicted that

trends evident as of June 28, 1974, would make full compliance

with the Pasadena Plan progressively easier. Superintendent Cor

tines subscribed to that prediction in his own supporting affidavit

of the same date, and both he and Mr. Marcheschi testified, at trial,

that full compliance with the Pasadena Plan can be achieved

(App. 468-M69, 473). The June 28, 1974, Hagen and Cortines

affidavits have been lodged with the Clerk of this Court.

201-03S— 76- -2

14

See also id. at 146 (Peter Hagen, the school dis

trict’s administrative director of planning, research

and development, testifying that as of February 1975

Pasadena’s enrollment in grades K -3 was only 39.1

percent black, and in grades 4-6 was 43.8 percent).

c. Petitioners offered evidence in an effort to estab

lish that the Pasadena Plan had been educationally

counterproductive. They attempted to show that the

performance of the district’s students on certain

standardized tests had declined and that the perform

ance of its black students had not improved vis-a-vis

that of their white counterparts in either the school

district or the Nation as a whole (App. 520-523; Pet.

Exhs. AC, AK, AL, AM, AN, AO ).19

The United States presented evidence tending to

show that the plan has been an educational success

in several ways. The learning environment of the dis

trict’s schools, as measured by student self-esteem,

attitude toward school, anxiety, and other criteria,

has been stable (App. 389-391, 543-549; U.S.

Exh. 24) .20 Serious disciplinary problems have been

few (App. 383-385). And, under the Plan, the dis

trict has been able successfully to implement a variety

of innovative educational programs and “ alterna

tives,” including special programs at its regular

19 “ Pet. Exh.” refers to exhibits introduced by petitioners at the

February-March 1974 hearing of this case. “U.S. Exh.” refers to

exhibits introduced by the United States at that hearing.

20 Indeed, the study conducted by our expert witness disclosed

a significant decrease in the anxiety level o f black children be

tween 1972 and 1973 (App. 546-547).

15

schools and the creation of special schools (App.

841-346, 356-375, 382, 512-513, 525, 527-528).21

We also presented expert testimony on academic

achievement. Our expert analyzed petitioners’ achieve

ment charts and concluded that the rate of black and

white students’ academic growth disclosed by those

charts properly should be viewed as a net gain for

black students, an indication of academic success not

evident prior to desegregation (App. 557-560, 564-

565). In addition, the expert pointed out that the dis

trict’s white students have suffered no academic set

back, as compared with national norms, during the

desegregation process (App. 564-566).

The district court was unpersuaded by petitioners’

effort to demonstrate that the Pasadena Plan has been

an educational failure (App. 458), and none of the

judges of the court of appeals found any error in the

district court’s resolution of the issue.

The district court’s resolution of this dispute has

been supported by the testimony of Dr. Myers in a

subsequent hearing. Dr. Myers testified (Sept. 15,

1975, Tr. 17-18, 33) :

We believe that the successes of the funda

mental school, the spectacular upturn in test

scores, particularly for black students and

others as well, but the narrowing of the gap,

the disparity between the Anglos and the blacks

which, in our opinion, is the answer to the seg

regation problem; the results have been so spec-

21 Superintendent Cortines testified that such innovations can

continue, and the kinds of “ alternatives” envisioned by the Alter

native Plan (see App. 210, 213-214) can be implemented, under

the Pasadena Plan (App. 511-512, 527-529).

16

taeular in narrowing this gap in keeping- the

black students’ scores from dropping off that

we just think that it is vital that we get the

black community more involved in fundamental

basic-type education.

* * * * *

We reversed our test scores dramatically

after a horrible decline for the last five or six

years, a dramatic upturn in all areas, not only

the fundamental schools, but because of the

competition that the fundamental school is giv

ing the regular schools, their scores turned up

as well.

d. The Plan has succeeded as an instrument of de

segregation (see App. 403-409, 416-417, 441-447). The

school board has not, however, entirely succeeded in

complying with the literal terms of the district court’s

order that there be “ no majority of any minority” in

any school. During the 1971-1972 school year the black

enrollment at Loma Alta school exceeded 50 percent of

that school’s total enrollment (App. 445, 585-586). By

October 1972 four schools (Edison, Franklin, Loma

Alta, and Sierra Mesa) had black enrollments in ex

cess of 50 percent of their respective total enrollments

(App. 403, 404, 406, 407, 585-586). A fifth school

(Eliot Junior High) joined this group a year later

(App. 417, 585-586). There has, therefore, been a

slight deviation from the student assignment provi

sions of the Plan and the 1970 order, as interpreted by

the district court.22

22 The plaintiffs and the United States had not understood the

decree to require continued adherence to the “no majority o f any

minority” provision (App. 268-269; see also Pet. App. A16, n. 4).

17

3. THE PROPOSED “ INTEGRATED ZONE/EDUCATIONAL ALTERNATIVES

p l a n ”

In a recall election of October 13, 1970, Mr. Henry

Marcheschi and two other candidates for school board

membership unsuccessfully attempted to unseat the

three board members who had voted against appeal

of the district court’s 1970 judgment (App. 453).

Mr. Marcheschi ultimately was elected to the board

in the spring of 1971 (App. 471-472). He testified

that “very early in [his] tenure as a board member”

he began to develop alternatives to the Pasadena Plan

(App. 474, 498). The first of the Marcheschi alterna

tive proposals—“ The Hew Pasadena Plan: A Recom

mended Hew Approach to Achieve Voluntary Integra

tion and Equality of Educational Opportunity in the

Pasadena Unified School District” (App. 422-434, 474,

570-580)—was presented to the school board in the

fall of 1971 (App. 376, 475). The second proposal—

“neighborhood School/Integrated Zone Plan for

Grades K -6 : A Proposed Plan to Restore neighbor

hood Schools [etc.]” (App. 474-475, 587-599)—was

presented on January 9, 1973 (App. 340, 475).

Both of these proposals were designed to create

freedom of choice in student enrollment; they were an

outgrowth of their author’s commitment to the neigh

borhood school concept (see, e.g., App. 497) and of his

belief that, although voluntary integration is desirable,

racial separation in public education is preferable to

desegregation compelled by court order (see App.

480-484).

18

Petitioners Myers, Newton and Vetterli were elected

to the school board on March 3, 1973 (App. 468) on a

pledge to “ restor[e] neighborhood schools [and] elimi-

nat[e] excessive educational experiments on our chil

dren” (App. 283). Mr. Marcheschi became president

of the board in July 1973 (App. 472).

On July 10, 1973, the school board, on the votes

of petitioners Myers, Newton and Vetterli, voted to

appoint three persons to administrative positions in

the school system without following the staff recruit

ment and selection procedures of the Pasadena Plan.

This action has become the basis for a contempt

citation by the district court (384 P. Supp. 846).

Later in the same month, joined by Mr. Marcheschi,

this majority appointed two persons to principal-

ships without adhering to the Pasadena Plan’s pro

cedures. For this, too, these petitioners have been

held in contempt. See 384 F. Supp. at 847-851; App.

514-518.23

The student enrollment plan that petitioners pro

posed as a substitute for portions of the Pasadena

P lan24 was primarily the work of Mr. Marcheschi

(App. 473M74). He presented the Alternative Plan

to the board on December 18, 1973 (App. 297) as a

further development of his earlier proposals (App.

479-480). The Alternative Plan, like Mr. Marcheschi’s

earlier proposals, allows students to choose which

23 The district court’s judgment o f contempt is sub judice on

appeal, having been argued on November 5,1975. Petitioners have

conceded that they did not follow the plan’s procedures, but have

argued that they were not obliged to follow them.

24 The proposed substitute, referred to as the “Alternative

Plan,” is reproduced at App. 239-245.

19

school they will attend, and it was designed to facili

tate the selection by students or their parents of neigh

borhood schools.25 26

The Alternative Plan is limited to student enroll

ments in elementary (K -6 ) schools (App. 241-242).20

It would eliminate specific school attendance bound

aries in favor of “ four racially and ethnically

balanced zones * * * whose boundaries [would] coin

cide with the four existing areas on which the pres

ent Pasadena Plan is designed” (App. 241). Stu

dents would be permitted to attend any school within

the zone of their residence; necessary transportation

would be provided (App. 241). The present division

of elementary schools into “primary” and “ upper

grade” schools would be replaced by the traditional

K -6 organization, in order to “provide a sufficient

number of school sites within each zone from which

parents can choose the type of education most ap

propriate for each of their children” (App. 239).

The Alternative Plan proposes the “ establishment

of unique educational alternatives at each K -6 school

site in addition to the ongoing traditional program

being taught there” (App. 239). Parents could choose

to place their children in either the regular or the

“ unique alternative” program at their chosen school

(see App. 485). Although it briefly describes some

possible “ unique alternatives” (see App. 240, 243-

244), the Alternative Plan is skeletal. It does not ex

25 Both the Alternative Plan ( App. 239, 241, 242; cf. App. 299,

355) and Mr. Marcheschi’s testimony (App. 479,481,482-484,488-

490,497,500,502) make this clear.

26 The Pasadena Plan would be retained for grades 7-12.

20

plain, for example, what “ alternatives” would be

offered, at what schools they would be offered, or

whether each of the “ unique” programs ultimately

offered by the district would be represented in each

zone. Mr. Marcheschi testified that these decisions had

not yet been made (App. 484-485).

Petitioners hope that the “ unique alternatives” will

encourage voluntary integration by acting as “mag

nets,” that is, by attracting students of varied back

grounds from all parts of each zone (App. 239).

Petitioners offered no evidence that this would in fact

occur, however, and conceded that if parents and

students select “ neighborhood” schools, it will not

occur. The Alternative Plan acknowledges that “ the

ethnic balance at some sites may be altered from what

it is at present” (App. 2 4 1 );27 nothing in the Plan

precludes schools from regaining their former racial

identifiability. When schools become racially identifi

able as a result of the operation of the Alternative

Plan, it provides for part-time “ pairing” of “ sister

schools” of divergent racial compositions. For one-

half day each week, students could visit the “ sister

school” to take advantage of any special programs at

that school (App. 241).

The Alternative Plan does not establish what

procedures wrould be followed to determine students’

initial school selections or what would be done in

the event more students chose a particular school

than that school could accommodate. Mr. Marcheschi

27 See also App. 299,481-488.

21

testified that “ the first priority for seats in [each]

school would go to children who are in the neighbor

hood served by that school and the priority would also

extend equally to children whose race is in the minor

ity in that particular school” (App. 479). He indi

cated, however, that “ [t]here is no way * * * to

anticipate” enrollments by race under the Alternative

Plan, because parents’ choices of schools cannot be

foreseen (App. 486-487, 492). He also acknowledged

that school officials do not know how many white

students would be attracted back to the school district

under the proposed Alternative Plan (App. 501),

and he informed the district court (App. 502) :

Your honor, I believe that returning to a sys

tem which enables Caucasian families, that pro

vides them the right to attend their neighbor

hood school if they so desire is a very critical

and important element in reversing the actions

■which I have referred to as the white boycott of

our school system.

* * * I believe that once we have these families

. moving back into our neighborhood, into our

district, that it seems to me we at least have them

here and can begin to be persuaded and can be

gin to apply the kind of incentives that it will

be necessary to apply to get them to move out

of their neighborhood school.

Superintendent Certifies testified that he preferred

the Pasadena Plan to the Alternative Plan (App. 519,

525). and that the one-half day pairing arrangement

envisioned in the Alternative Plan “ does not provide

22

the kind of interchange among the different ethnic

groups that I believe is worthwhile” (App. 526).

The district court found that at least some schools

would regain their former racial identifiability if the

Alternative Plan were implemented (App. 455-457;

cf. App. 329, 395, 396, 485-486, 499-500, 583)28 and

that an effective implementation of the Alternative

Plan would require as much (or more) student trans

portation as has proved necessary under the Pasadena

Plan (App. 458; ef. App. 492-493, 513). Neither of

these findings was disturbed by the court of appeals.

Judge Ely expressly agreed that the Alternative Plan

would produce racially identifiable schools (Pet. App.

A8, A14) ; Judge Wallace, apparently agreeing (id.

at A26-A27), disputed only the standard used by the

district court to evaluate the legal consequences of that

effect.

C. THE DISTRICT COURT’S OPINION

The district court denied petitioners’ January 15,

1974 motion in its entirety (App. 452-459).

The district court offered several reasons for de

clining to dissolve its injunction and terminate its

supervision over the Pasadena schools. It found that

there had not been full compliance with the Pasadena

Plan because several schools were operating in viola

tion of the “ no majority of any minority” rule (App.

454). It concluded that the school officials had resisted

28 In the Pasadena Unified School District neighborhood schools

would be, to a substantial degree, racially identifiable schools

(App. 329,471,506-507, 583, Bear Folios).

23

the Plan and had declined to cooperate with it, so that

it would be unreasonable to infer that, if left to their

own devices, they would assiduously foster desegre

gation (App. 458). It observed that, if petitioners

were allowed to return to a ‘ ‘neighborhood school”

policy or a “ freedom of choice” plan, much of the

Pasadena Plan would be undone and the schools would

regain their former racial identifiability (App. 455-

456, 459). And it found that the Pasadena Plan had

not become an instrument of wrong: it was not demon

strably the cause of “ white flight” (App. 454), and it

was not demonstrably the cause of any educational

deficiencies (App. 458). I f the latter were the ease,

the court reasoned, the educational deficiencies could

be corrected by making suitable alterations in the

Pasadena Plan, without the need to dissolve it (App.

457).

The district court also declined to replace the Pasa

dena Plan with the Alternative Plan, holding that the

Alternative Plan would be unsuccessful as an instru

ment of desegregation (App. 455-456). Referring to

petitioners’ argument that the Pasadena Plan had

been the cause of “ white flight” and that the Alterna

tive Plan could both solve this problem and desegre

gate the schools, the court answered (App. 457, foot

note omitted) :

Hope may spring eternal, but realism exposes

the folly of the belief that one who left a school

district because his children were forced to at

tend schools with Negro children would now

voluntarily choose that alternative.

24

‘ ‘ Freedom of choice” plans had failed before in

Pasadena and elsewhere in California, the court

found, and it concluded that petitioners had not

demonstrated that such a plan would not fail again.

Finally, the court found that if the Alternative Plan

were to be an effective plan of desegregation it would

require as much busing of students as was being used

to implement the Pasadena Plan (App. 458).

D. THE COURT OF APPEALS’ OPINIONS

A divided court of appeals affirmed and remanded

for further proceedings; each member of the panel

wrote a separate opinion (Pet. App. A1-A33). None

of the opinions questions the district court’s findings

of fact.

Judge Ely began by emphasizing “ the narrow am

bit of * * * review” (Pet. App. A2). The propriety

of the original judgment and injunction, and of the

Pasadena Plan itself, were not before the court,

Judge Ely concluded (ibid.) :

The only question before us now is whether

the District Court erred in its determination

* -* * that events and circumstances occur

ring * * * since the Pasadena Plan was or

dered implemented do not justify relief from

the January 23, 1970, Decree * * * or the sub

stitution of a substantial alteration of the

original Pasadena Plan.

Judge Ely wrote that two tests governed the exer

cise of the district court’s discretion to retain juris

diction and continue its injunction (Pet. App. A6-

25

AT) : whether the dangers that caused the issuance of

the injunction had been attenuated to a shadow, and

whether intervening events had converted the in

junction into an instrument of wrong. He found that

the district court had not abused its discretion in

the evaluation of either factor. The dangers of segre

gation had not been sufficiently attenuated, Judge

Ely thought, in light of the violations of the “ no

majority o f any minority” rule and in light o f the

perceived intransigence of the school board, culmi

nated by the submission of a substitute plan that the

board should have known was inadequate to eliminate

the effects of its earlier acts of segregation. A or had

the injunction become counterproductive; petitioners’

assertions that it had caused “ white flight” and edu

cational degradation had been discredited by the dis

trict court in findings that were not clearly erroneous

{id. at A8-A10). Judge Ely concluded that because it

was not yet “ clear” that disestablishment of the dual

school system had been achieved, the district, court

was required to retain jurisdiction (id. at A11-A12).

As to the proposal to substitute the Alternative

Plan for portions of the Pasadena Plan, Judge Ely

reasoned that, once it had been established that the

district court was empowered to retain jurisdiction

over the Pasadena schools, it followed that the court

had substantial equitable discretion to select an ef

fective remedy (Pet. App. A13). The district court

properly exercised that discretion in preferring the

Pasadena Plan, which had been devised by the school

board in 1970, over the school board’s 1974 submis

26

sion, because the latter held out less promise of suc

cessfully producing desegregation. Judge Ely con

cluded that, whatever virtues the Alternative Plan

may possess, there was ample support for the dis

trict court’s conclusion that it would not discharge

petitioners’ duty to achieve the greatest possible

amount of desegregation {id. at A14), and that the

district court therefore properly rejected it.

Chief Judge Chambers wrote (Pet. App. A20)

that “ a school district surely should not be kept

under injunctions of a court forever.” He found,

however, that because the school board had not fully

discharged its duty of compliance with the district

court’s unappealed 1970 injunctive degree, the judg

ment must be affirmed. Judge Chambers concluded

(Pet. App. A21) :

I interpret Judge Ely’s opinion as requiring

a termination of the mandatory injunction

within a very short time after the school [>>•]

again gets in compliance and I think the mes

sage is clear to the district court.

* * * I have some doubt that one will find

any de jure segregation after the decree has

been complied with again—if all that is done

is to let residence patterns shift by themselves.

Judge Wallace dissented. In his view, the district

court erroneously had equated de jure and de facto

segregation (Pet. App. A23, A26) and consequently

had neglected to consider the question “whether the

segregation foreseeable upon dissolution of the in

junction is attributable to intentionally segregative

actions of the school district” {id. at A27, footnote

27

omitted). Believing that a desegregation decree must

be dissolved, and the jurisdiction of the district court

terminated, once a school board demonstrates that the

effects of its earlier segregative acts have been eradi

cated (id. at A27-A28), Judge Wallace would have

remanded “ for a determination whether de jure

segregation still exists in the Pasadena schools” (id.

at A30). Under this proposed remand, a “ heavy

burden of proof” (ibid.) would have been imposed

upon petitioners, who would have been required to

prove both the extent of segregation caused by the

school board’s acts and that all of the effects of these

acts had been overcome. I f petitioners can carry

those burdens, Judge Wallace wrote, the district court

should terminate its active supervision.

All three judges of the court of appeals expressly

disapproved both any perpetual application of the

“no majority of any minority” provision of the 1970

judgment and any requirement of annual redistrict

ing in response to demographic changes. See Pet.

App. A l l (opinion of Ely, J.) ; id. at A20 (Cham

bers, J., concurring) ; id. at A25 (Wallace, J., dis

senting) .

S U M M A R Y OF A R G U M E N T

I

A. Most of petitioners’ arguments are not perti

nent to the consideration or decision of this case.

Petitioners’ repeated assertions that this case in

volves the pursuit of racial balance for its own sake

are inaccurate, for the district court’s 1970 opinion

28

catalogued extensive and systematic segregaterv con

duct by school officials that contributed substantially

to the creation of racially identifiable schools in

Pasadena. Those pervasive acts of segregation, quite

similar to those considered by this Court in Keyes

v. School District No. X, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S.

189, required the district court to conclude that a

dual school system had been established by law, and

consequently to take whatever action was required

to eliminate racial discrimination “ root and branch”

( Green v. County Sdhool Board, 391 U.S. 430, 438).

The “no majority of any minority” provision in the

1970 decree was, in 1970, “ a useful starting point in

shaping a remedy to correct past constitutional vio

lations” (Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 25).

To the extent the “no majority of any minority”

provision of the decree may have become a continuing

requirement of racial balance, it has properly been dis

approved by the court of appeals. Likewise, the court

of appeals correctly disapproved any requirement that

students be reassigned to different schools annually in

order to compensate for demographic changes. Peti

tioners disregard these aspects of the court of appeals’

decision; their insistent attack upon statements of the

district court disapproved by the court of appeals is

wholly gratuitous.

Petitioners also intimate that this is a “busing” ease

and request the Court to determine whether, and to

what extent, federal courts can require school authori

29

ties to use transportation to implement a system of

student assignments. Concern about the use of trans

portation is legitimate. But the current law of equi

table remedies (see, e.g.. Swann, supra,) authorizes

the use of transportation in a case such as this.

In the district court petitioners did not challenge

particular transportation requirements, but at

tempted instead to prove that the entire student

assignment plan (rather than its transportation com

ponent in particular) was educationally disadvan

tageous and had led to “white flight.” They failed

in their proof, and the court of appeals held that

the district court’s findings were not clearly erroneous.

We submit that the only three points requiring con

sideration by the Court are whether the district court

was required at the present stage of the case to termi

nate entirely its supervision over the Pasadena

schools; whether, if some supervision is still appro

priate, it can include a “regulatory” desegregation

plan; and whether, if regulatory supervision is ap

propriate, the district court should have substituted

the Alternative Plan for the Pasadena Plan.

B. As to the first point, this Court has repeatedly

recognized that full implementation of the constitu

tional guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment can

not be achieved unless the district courts retain juris

diction until it is clear that disestablishment of the

dual school system and all of its effects has been ac

complished. Even if petitioners were correct in their

201-058- — 6

30

argument that the Pasadena schools became “ unitary”

the moment the Pasadena Plan was implemented, this

would not support petitioners’ claim for termination

of the district court’s “passive” supervision. Continu

ing supervision, with or without judicial enforcement

of a desegregation plan, is necessary to deter future

acts of segregation by making the contempt power

available and allowing the district court promptly to

rectify such acts if they occur. I f an injunction is ap

propriate even when individuals have voluntarily and

completely desisted from illegal acts (see United

States v. W. T. Grant- Co., 345 IT.S. 629, 633), it fol

lows that continuing judicial supervision of some sort

is appropriate here, where the injunction was neces

sary to compel the school officials to abandon their

unconstitutional practices. Judicial supervision should

last until a unitary school system has been achieved

and maintained for a significant length of time with

out additional judicial compulsion.

C. Petitioners direct a major challenge to the dis

trict court’s continuation of active or regulatory

supervision, including the enforcement of a manda

tory desegregation plan. They contend that even if

such regulatory supervision was necessary in 1970 it

should now be discontinued.

Injunctions in desegregation cases, like other in

junctions, are subject to the usual standards govern

ing the equitable powers of federal courts. Milliken

v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 737-738; Swann, supra, 402

31

U.S. at 16. A motion for modification or dissolution

of a desegregation plan therefore is an appeal to the

equitable discretion of the district court. The dis

trict court may modify the injunction because of an

intervening and unexpected change of circumstances,

because it has achieved its purpose, or because it has

become an “ instrument of wrong” ( United States v.

Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106, 115). None of these condi

tions is present in this case.

The original decree plainly has not yet achieved its

purpose. Some decisions of school officials that create

or maintain racially identifiable schools have long-last

ing effects. For example, school siting and capacity de

cisions often will have racial effects that persevere for

much or all of the building’s lifetime. For this and

other reasons, the findings of the district court pro

vide substantial support for the conclusion of the

courts below that the past segregation in the Pasadena

schools would have substantial, lingering effects. Since

petitioners had not come forward with an adequate

alternative remedy for those effects, continued regula

tory supervision by the district court was required.

See Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 28.

Nor have changed circumstances made the Pasadena

Plan an “ instrument of wrong.” Petitioners argued in

the district court that the Pasadena Plan had precipi

tated “white flight” and had caused deterioration in

the quality of education offered by the Pasadena

schools. But the district court found these arguments

32

to be unsupported by the facts, and the court of ap

peals concluded that its findings are not clearly er

roneous. Petitioners therefore have not established the

foundation for their contention that the regulatory

supervision of the district court must come to an end.

More than 100 school systems have demonstrated

that the effects of segregation have been eliminated

to the fullest extent possible and have been released

from the regulatory supervision of the district courts.

Such relief is a goal shared by school systems, the

federal courts (see Swann, supra), the Congress (see

20 IT.S.C. (Supp. IV ) 1718), and the federal Execu

tive Branch. Petitioners will have ample opportunity

to obtain release from regulatory supervision once the

vestiges of segregation have been eliminated from the

Pasadena schools.

I). If, as we have argued, it was proper for the

district court to continue its regulatory supervision

of the Pasadena schools, it follows that it was

proper for the court to reject the Alternative Plan.

The Alternative Plan is little more than a disguised

abandonment of active judicial supervision, for it

has no provision for overcoming the effects of dis

criminatory school siting and capacity decisions and

other vestiges of the de jure segregation carried on

by school authorities. The Alternative Plan is es

sentially a “ freedom of choice” plan. “ Freedom of

choice” plans have been unsuccessful in ending seg

regation in Pasadena and elsewhere in California,

33

and the district court properly concluded that noth

ing in the Alternative Plan held out any realistic

probability of greater success.

II

The private plaintiffs have graduated from the

Pasadena schools. Whether or not this moots the

case as to the private plaintiffs, the presence of

the United States as a plaintiff is sufficient to pre

serve a live case or controversy. The United States

intervened pursuant to 42 U.S.C. 2000h-2, which

provides that “ the United States shall be entitled

to the same relief as if it had instituted the action.”

In this case the United States sought desegregation of

the entire school system, relief more extensive than

had been sought by the private plaintiffs. The school

authorities argued that the United States should be

confined to the relief that had been sought by the

private plaintiffs; the court of appeals rejected that

argument, holding that our complaint in intervention

properly brought into the case “ the entire Pasadena

Public School system” (415 P. 2d at 1243). The At

torney General has certified that this case is of gen

eral public importance—in other words, that the

United States has an interest in addition to that of

the private plaintiffs. Such a general public interest

survives their graduation.

34

A R G U M E N T

I

THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION BY

DECLINING TO DISSOLVE ITS INJUNCTION, TERMINATE

THE PASADENA PLAN, OR IMPLEMENT THE PROPOSED

ALTERNATIVE PLAN

A. MOST OF PETITIONERS’ ARGUMENTS ARE NOT PROPERLY PRESENTED

IN THE PRESENT POSTURE OF THIS CASE

This is a narrow case. Neither the correctness of the

district court’s 1970 judgment that the Pasadena

school system had been segregated by the deliberate

acts of its officials, nor the initial validity of the

court’s 1970 directive that no school in the system

enroll “ a majority of any minority students” (App.

3-4), was before the court of appeals. Yet petitioners

seek to raise those issues here (Pet. Br. 3, 11-18), con

tending that the decisions of the district court are

inconsistent with Swcmn v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 TJ.S. 1. Petitioners direct

most of their argument against certain dicta in the

opinions of the district court29 and a remark that the

district court made during a hearing.30 But the dicta

29 See App. 456, n. 10, in which the district court equates cle facto

and de jure segregation. Cf. App. 99, n. 4 (“ [r]acial segregation

and racial imbalance are two names for the same phenomenon,

racial separation” ).

30 See App. 270, where the district court stated during an oral

argument that the Pasadena Plan “meant to me that at least

during my lifetime there would be no majority of any minority

in any school in Pasadena.”

35

of the district court are not on review here; the court

of appeals has relieved petitioners of the portions of

the district court’s order to which they might legiti

mately object, and has disapproved the district court’s

statements upon which petitioners dwell. As a result,

most of the arguments of petitioners are misdirected.

1. Petitioners proceed on the assumption that this

case is one in which the district court has sought to

bring about “ racial balance” for its own sake. They

contend, for example, that “ [t]he failure of the

Pasadena School Board to correct * * * racial im

balance was the primary basis on which the system

was found to be a dual system” (Pet. Br. 3; see also

Pet. Br. 11-13). This is a gross misinterpretation of

the proceedings in this ease. Absence of racial balance

was not the basis for the original finding of cle jure

segregation.

In 1970 the district court was presented with exten

sive proof, and made detailed findings, that over a

period of fifteen years the Pasadena school board had

engaged in a series of deliberate, unconstitutionally

discriminatory actions that created significant racial

separation of students and faculty, particularly in

elementary schools. See App. 97-126, 128, and our

summary of these findings at pages 6-9, supra.

The actions described by the court—among them,

racial gerrymandering and the manipulation of

student assignments designed to lock black students

into heavily black schools and to avoid assigning

whites to such schools, the transportation of white

36

students past under-enrolled majority-black schools to

more distant “ white” schools, the granting of racially-

motivated transfer requests that intensified racial seg

regation, the practice of assigning most black teachers

and black substitute teachers to black schools and per

mitting white substitutes to shun those schools, and

the racially-motivated manipulation of school con

struction and transportable classroom placement—-

were deliberate acts that served to identify certain

schools as intended, by the school board, for blacks,

and others as intended for whites. Green v. County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 435; Swann, supra, 402

U.S. at 18. Those pervasive, deliberate acts of segre

gation, causing the district’s schools to become vehicles

of racial discrimination, closely paralleled the segre-

gatory acts which this Court held in Keyes v. School

District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S. 189, to

require a district court to conclude that a dual school

system had been established by law. Accordingly, the

board’s pattern of discriminatory conduct here be

stowed upon the district court

the affirmative duty to take whatever steps

might be necessary to convert [Pasadena] to a

unitary system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated root and branch.

Green, supra, 391 U.S. at 437-438.

The 1970 decree thus responded to well-entrenched,

systemic violations of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The “no majority of any minority” provision of the

1970 decree was, in 1970, “ a useful starting point in

37

shaping a remedy to correct past constitutional vio

lations.” Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 25.

2. Petitioners nevertheless contend that, by 1974,

the “no majority of any minority” requirement had

become nothing more than a requirement of racial

balance for its own sake (Pet. 33r. 11-13). Petitioners

contend that this requirement is a rigid racial quota

(Pet. Br. 11), and that its status as such is demon

strated by the district court’s statement during a

hearing in 1974 that “ at least during my lifetime

there [will] be no majority of any minority in any

school in Pasadena” (App. 270). However, each of

the judges of the court of appeals (quite properly,

in our view) disapproved both the district court’s

statement and the “no majority of any minority” rule,

to the extent that either indicated a continuing, rigid

insistence upon some particular degree of racial bal

ance. See Pet. A l l (Ely, J.) ; id. at A20 (Chambers,

C.J., concurring) ; id. at A25 (Wallace, J., dissenting).

Petitioners’ insistent attack upon these statements of

the district court is therefore wholly gratuitous.

3. Petitioners also contend that the district court

lacks the power to compel them to undertake the

annual reassignment of students in order to achieve

a particular degree of racial balance (Pet. Br. 13-14,

16-18). To the extent such a requirement may be im

puted to the district court, it was an outgrowth of

the “ no majority of any minority” provision in the

1970 judgment. It, too, has been disapproved by the

court of appeals. See pet, App. A l l (Ely, J.) ; id.

38

at A20-A21 (Chambers, C.J., concurring); id. at

A25 (Wallace, J., dissenting). The court of appeals

correctly held that there is no need for annual stu

dent reassignment to achieve the maximum feasible

degree of racial balance. Accord, Mapp v. Board

of Education, 525 F. 2d 169 (C.A. 6 ); Calhoun v.

Cook, 522 F. 2d 717 (C.A. 5), rehearing denied, 525

F. 2d 1203 (C.A. 5) ; Morgan v. Kerrigan, C.A. 1, No.

75-1184, decided January 14, 1976, slip op. 32-33.

A redrawing of school attendance zones after the

desegregation decree is first approved may sometimes

be necessary in order to eliminate the continuing

effects of past segregation, and, to that extent, the

district court in this case retains the authority to

revise its injunction. See 20 U.S.C. (Supp. IV )

1707.31 But this case no longer presents the problem

of redrawing of attendance zones for any other pur

pose. As Chief Judge Chambers wrote (Pet. App.

A21), it is not an act of segregation for racial im

balance to occur under a court decree “ if all that is

done is to let residence patterns shift by themselves.”

See also Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 31-32.

4. Petitioners intimate that this is a “ busing” case

requiring the Court to decide whether, and to what

extent, federal courts can require school authorities

to use transportation to implement a system of stu

dent assignments (Pet. Br. 4-5, 11). Cf. Swann,

supra, 402 U.S. at 30-31.

31'20 U.S.C. (Supp. IV ) 1707 provides that reassignment is not

necessary if residential patterns change after a district court has

determined that all vestiges o f segregation have been eliminated.

39

The concern about transporting school children to

accomplish desegregation is a legitimate one that may

call for the further attention of the Court in an appro

priate case. But petitioners made no record in the

district court that would now permit a reexamination

of busing as a remedy on the basis of experience with

that remedy here,32 and in light of accumulated experi

ence in other communities across the nation.33 The cur

rent law of equitable remedies in school desegregation

cases supports transportation in a case such as this.

Swann v. Board of Education, supra; Davis v. School

Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33. It is, of course, always

open to litigants to seek judicial reassessment of prec

edent, but the materials for reassessment must be

provided. To do so is not to question Brown Vs dis

positive constitutional objection to de jure segrega

tion. Swann shows that transportation is an equitable

remedy whose “ task is to correct, by a balancing of the

individual and collective interests, the condition that

offends the Constitution.” 402 U.S. at 16.

32 To the extent that petitioners attempted to show in the district

court that the Pasadena Plan had caused “ white flight” or deteri

oration in educational quality, they failed in their proof. See pages

11-16, supra ; pages 54-55, infra.

33 See, e.g., Symposium, The Courts, Social Science, and School

Desegregation , 39 L. and Contemp. Prob. 1-432 (1975); Goodman,

De Facto School Segregation: A Constitutional and Empirical

Analysis, 60 Cal. L. Eev. 275 (1972); Pettigrew, Racial Discrimi

nation in the United States (1975); St. John, School Desegregation

Outcomes fo r Children (1975); Comment, School Desegregation

A fter Swann : A Theory o f Government Responsibility, 39 U. Chi.

L. Eev. 421 (1972); Mills, The Great School Bus Controversy

(1973).

40

town I I also remarked the “ practical flexibility”

that characterizes equitable decrees. 349 U.S. at 300.

If, as appears to be the case, petitioners now seek to

challenge court-ordered transportation as a futile or

damaging response to de jure segregation, they did

not focus their case below to that end.34 Their proof

below was not guided by an articulation of the pur

pose of student transportation under a decree—

whether it is designed to produce the approximate

degree of integration, that would have existed absent a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, to repair

psychological injury inflicted by the state, to cure

educational deficiencies traceable to de jure segrega

tion, or perhaps to achieve some other or additional

purpose (see n. 42, infra). Accordingly, petitioners

failed to prove that transportation lacks utility in

achieving the articulated remedial goal. In its present

84 Instead, in the board’s closing argument during, the hearings

on its present motion in the district court, counsel for the board

stated (App. 568) :

“ * * * I as a lawyer in this court have not regarded the busing

problem or the busing question as an issue in this case. W e are

going to have busing, your Honor. The board intends to continue

busing. Any child may bus, as I have said, under the alternative

plan within his zone.”

The district court found that “ the evidence shows that as much

or more busing would be necessary to accomplish the ends o f an