Boynton v. Alabama Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 8, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boynton v. Alabama Brief for Appellants, 1965. 499ea096-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/651abc5a-df64-424d-bde4-0f7cbeb29f3d/boynton-v-alabama-brief-for-appellants. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

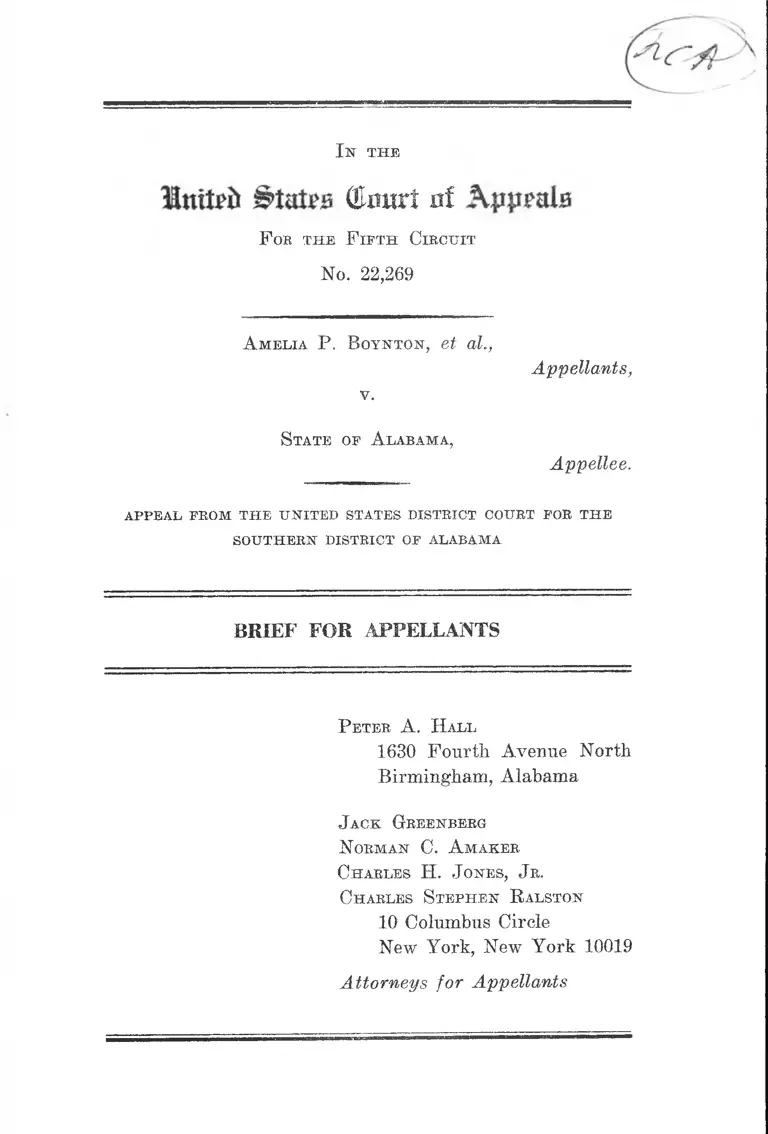

I n t h e

(Eflurt of

F ob t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 22,269

A m elia P. B oynton, et al.,

v .

Appellants,

S tate of A labama,

Appellee.

A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA T E S D IST R IC T CO U RT FO R T H E

S O U T H E R N D IS T R IC T O F ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

J ack Greenberg

N orman C. A maker

C harles H . J ones, J r.

C harles S t e ph e n R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ................... .............................. 1

(1) Appellants Boynton and Gildersleeve .......... 2

(2) Appellant McRay ........................ 3

(3) Appellant Vivian ........... ................... ............. 4

Specification of Error .................................................. 5

A rgum ent—

Appellants’ Removal Petition Adequately States

a Case for Removal Under 28 U. S. C. §1443 ...... 6

I. The Removal Petition Is Sufficient Under 28

U. S. C. §1443(2) .............................................. 6

A. “Color of Authority” and “Quasi-Official”

Conduct ........................ 8

B. Law Providing for Equal Rights ............... 13

C. The Acts for Which Appellants Are Pros

ecuted ............................................................. 14

II. The Removal Petition Is Sufficient Under 28

U. S. C. §1443(1) ............................................ 16

Conclusion ............................. 22

T able of Cases

PAGE

Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark.

196S) -..............-..................... -................. -.............6,14,15

Board of Education of City of New York v. City-Wide

Committee for Integration, 342 F. 2d 284 (2nd Cir.

1965) ....... .................................. ,.............................. .. io

Boynton v. Clark, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 215 (S. D. Ala.

1/23/65) ----- ---------------- -------- -------------- 3, 4,10,12

Braun v. Sauerwein, 77 U. S. (10 Wall.) 218 (1869) .....7,12

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1883) ............. ........ 19

Carmichael v. City of Greenwood, 5th Cir., No. 22289

(slip. op. 9/30/65) ........................................... 6

Colorado v. Knous, 348 U. S. 941 (1955) ........... ......... 15

Colorado v. Maxwell, 125 F. Supp. 18 (D. Colo. 1954),

leave to file petition for prerogative writs denied

sub nom. ......... ............................................. 15

Colorado v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) ..................... 15

Annie Lee Cooper and Stanley Leroy Wise v. State of

Alabama, 5th Cir., No. 22424 .... .... ............. ..... .... ...... 2

Cox v. Louisiana, 348 F. 2d 750_______________ 6,16,20

Cunningham v. Neagle, 135 U. S. 1, 10 S. Ct. 658, 34

L. Ed. 55 (1890) ____ ____ ________ __ _______ 12

Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (5th Cir. 1965) ___ 18

Ex parte Dierks, 55 F. 2d 371 (D. Colo. 1932), man

damus granted on other grounds sub nom________ 15

Forman v. City of Montgomery, 245 F. Supp. 17 (M. D.

Ala. 1965) ______ __________ ________ 21

Galloway, et al. v. City of Columbus, 5th Cir., No. 22935

(slip. op. 11/24/65) ................. ........... ...... 6

Ill

PAGE

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 (1896) .......... ....... 19

Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (Pa.) 412 (Strong, J.,

at nisi prius, 1863) ............... ....................... ............7,15

Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (No. 6568)

(E. I). Pa. 1863) .................. ...... ................ ................7,15

Hughley, et al. v. City of Opelika, No. 2319-E (M. D.

Ala. 11/18/65) ............................................................. 21

Johnson v. City of Montgomery, 245 F. Supp. 25 (M. D.

Ala. 1965) .................................................................. 21

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 ................................. 19

Logemann v. Stock, 81 F. Supp. 337 (D. Neb. 1949) .... 15

John L. McMeans, et al. v. Mayor’s Court of Fort

Deposit, Alabama, et al., No. 11,759-N (M. D. Ala.

9/30/65) ...................................................................... 21

McNair, et al. v. City of Drew, 5th Cir. No. 22288

(slip. op. 9/28/65) ...................................................... 6

Maryland v. Soper, 270 U. S. 9 .................................. . 15

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881) ..................... 19

Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 679 (5th Cir.

1965) ............................ ...........................6, 8, 9,10,15,16,

17,18,19, 20, 21

People of New York v. Galamison, 342 F. 2d 255 (2nd

Cir. 1965) ........................................................8,10,12,13,

14,15,17

Potts v. Elliott, 61 F. Supp. 378 (E. D. Ky. 1945) ....... 15

I V

PAGE

Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965) ....13,15,16,

18,19, 20

Robinson v. State of Florida, 345 F. 2d 133 (5th Cir.

1965) ......... ................................................................. 6,15

Rogers v. City of Tuscaloosa, 5th Cir., No. 21,700

(slip. op. 11/8/65) .............................................. .....20,21

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1880) ...... .............. 15

United States v. Clark, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 236 ....14,17,18

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961)

14,17,18

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 .................................. 19

Weathers v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 986 (5th

Cir. 1965) ................................................................... 6,16

In Re Wright, et al., No. 11,739-N (M. D. Ala. 8/3/65) .. 21

S tatutes I nvolved

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27 ..............8,12

Civil Rights Act of 1960 ......... ..................................... 7

Civil Rights Act of 1964 .............................................. 18

Habeas Corpus Suspension Act ..................................12,15

28 U. S. C. §1443 ....... ............................................. 5,6,14

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) ...... .......... ............ 5,6,8,9,10,13,

16,18,19,21

28 U. S. C. §1443(2) ................. ................... ..5, 6, 7, 8, 9,10,

12,13,14

42 U. S. C. §1971 .... ......................................5, 7,10,12,13,

14,16,17,18

V

PA G E

42 u. S. C. §1981............................................................. 5, 8

42 U. S. C. §1982 ............................................................. 5

42 U. S. C. §1983 ........ .......................................... ......... 5

Code of Alabama, Title 14, §41 ................................... 3,4

Code of Alabama, Title 14, §412 ................................... 3

1954 City Code (Selma, Ala.), §745 ......................... 3

I n t h e

Intfrfc States GImirt of Appeals

F ob t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 22,269

A melia P. B oynton, et at.,

v.

Appellants,

S tate of A labama,

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of United States Dis

trict Judge Daniel H. Thomas, remanding, without hear

ing, four criminal prosecutions to the Alabama courts from

which appellants had removed them, arising out of at

tempts by Negro citizens of Selma, Alabama, during the

months of January and February, 1965, to register to vote

and to peacefully demonstrate in support of their right to

register without racial discrimination.

On January 22, 1965, a joint petition was filed in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Alabama seeking to remove approximately 220 criminal

prosecutions, including those against appellants Amelia P.

Boynton and James Gildersleeve, from the County and

Juvenile Courts of Dallas County, Alabama (R. 4-17). This

petition was amended on two occasions pertinent hereto:

2

January 28, 1965, and February 17, 1965, adding, respec

tively, appellants Willie McRay and C. T. Vivian (R.

18, 26).

Appellee, State of Alabama, filed motions on February

3 and 19, 1965, to remand the original removal petition,

and its amendments-(R. 19, 26). No motion was made by

plaintiff City of Selma to remand appellant McRay’s claim

prior to entry of the remand order. Judge Thomas retained

jurisdiction and dismissed all removed cases except those

of appellants here, Annie Lee Cooper and Stanley Leroy

Wise (R. 35-38).J

Upon remanding each of these cases, District Judge

Thomas noted that “ [t]he petition on its face shows that

[the] offense is not a removable action” (id.). Because the

remand motions tested only the jurisdictional sufficiency

of the facts, the allegations of the removal petition, and

its amendments, must be taken as true. Those allegations

with respect to each prosecution are set forth below.

(1 ) Appellants Boynton and Gilder sleeve

On January 19, 1965, approximately 62 persons lined up,

either inside or at the rear of the Dallas County court

house to register to vote (R. 5, 7). They did this in the

exercise of rights under the First, Fourteenth, and Fif

teenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and

implementing legislation. Appellants Boynton and Grilder-

sleeve were then acting as voter qualification vouchers

and their duties required them to enter and exit frequently

from the court building. Both were intercepted by Dallas

County Sheriff James G. Clark’s deputies: appellant

1 An appeal from the remand of Cooper and Wise, arising out of

related incidents, is now pending before this court under style, Annie

Lee Cooper and Stanley Leroy Wise v. State of Alabama, 5th Cir., No.

22424.

3

Boynton upon departing from the coirrt building for re

fusing to join a group of potential registrants assembled

behind the building; appellant Gildersleeve while attempt

ing to enter the building after a refusal by a sheriff’s

deputy to permit his entry to assist in the registration

(R. 5, 6).

Appellants Boynton and Gildersleeve were placed under

arrest and charged with criminal provocation (Code of

Ala., Tit. 14, §41). Both were incarcerated and subse

quently released from custody upon personal recognizances

(R. 6, 7).

Shortly after appellants’ arrests, persons assembled be

hind the court building, some at the direction of sheriff’s

deputies, were arrested and charged with “[Remaining

present at the place of an unlawful assembly after having

been warned to disperse by a public officer,” in violation

of Code of Ala., Tit. 14, §412 (R. 5, 7). As noted, their

prosecutions were all subsequently dismissed.

(2 ) Appellant McRay

On January 25, 1965, appellant McRay approached a

voter registration line outside the Dallas County court

house and attempted to talk with one or several persons

standing in line (R. 18). He was arrested by policemen

of the City of Selma and charged with refusing to obey

a city officer (§745, 1954 City Code) (id.). Appellant

McRay sought to lend encouragement to those seeking to

register, clearly an exercise of rights under the First,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States and implementing legislation and

pursuant to the order of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama in Boynton v. Clark,

10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 215, entered January 23, 1965. That

4

order provided, inter alia, that “[T]hose seeking to register

and those seeking to act as vouchers will form an orderly-

line, not more than two abreast, from the entrance of the

office of the Board of Registrars down the corridor of

the courthouse in a line most direct to and through the

entrance of the Lauderdale Street door . . .” (Emphasis

added) (ibid. 216). The order also provided that “(p)eople

who are interested in encouraging people legally qualified

to register have a perfect right to lend such encourage

ment; and as long as this is sought through peaceful as

semblage, such assemblage is not to be illegally interfered

with.” Appellant McRay was released from custody on a

bond of $200.00 (R. 18).

(3 ) Appellant Vivian

During the afternoon of February 16, 1965, at about

2 :00, appellant Vivian arrived at the Dallas County court

house to speak to potential voter registrants, who were

lined up in front of the building (R. 26, 27). He advised

them that their line could be reformed inside the court

house, since they could not be required to stand in the

rain (R. 27). Their entry was barred by sheriff’s deputies,

and after a heated exchange of words with Sheriff Clark,

appellant and the others were forcibly driven from the

courthouse stairway, and Vivian was struck in the mouth

by one of the officers. Immediately preceding the forced

removal, Clark read an order, issued by Alabama Circuit

Judge Hare, ordering the assembly to disperse (R. 27, 28).

Appellant, alone, was placed under arrest, charged with

contempt of Judge Hare’s court and criminal provocation

(Code of Ala., Tit. 14, §41).

Appellants arrests and prosecutions were and are be

ing carried on with the purpose and effect of harassing

them and punishing them for their attempt to register to

5

vote, and for exercising their right of free speech to pro

test discrimination in the voter registration process (R.

12-13). The conduct for which they are prosecuted is pro

tected by the First, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States and implementing

federal legislation, so that the state statute and city

ordinance under which they are charged are unconstitu

tional in their application (R. 11, 12, 13-17). Appellants

are also being prosecuted for acts done under color of au

thority derived from the federal constitution and laws pro

viding for equal rights, i.e., United States Constitution,

Amendments I and XIV, and 42 U. S. C. §§1971, 1981, 1982

and 1983 (R. 14-15).

The remand order of Judge Thomas, having been en

tered April 16, 1965 (R. 35-38), timely notice of appeal

was filed on April 26, 1965 (R. 38-39). The district court

refused to grant appellants’ motion for stay of the remand

order (R. 39-41). This court, to preserve the questions

presented on appeal, granted appellants’ motion for stay

pending appeal (R. 43-46, 50-51).

Specification o f Error

The court below erred in remanding appellants’ petition

for removal, without hearing, on the ground that the peti

tion, facially, did not state a removable claim under 28

U. S. C. §1443.

6

ARGUMENT

Appellants’ Removal Petition Adequately States a

Case for Removal Under 28 U. S. C. §1443.

The District Court’s order, here appealed from, was en

tered before decision by the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit -in Peacock v. City of Green

wood,, 347 F. 2d 679 and Cox v. Louisiana, 348 F. 2d 750,

which severely restricted remand without hearing where

facts are alleged as in the present cases.2 Peacock and

Cox more precisely delimit the scope of removal jurisdic

tion under Title 28 U. S. C. §1443 and abundantly support

appellants’ removal claims.

I. The Removal Petition Is Sufficient Under

28 U. S. C. § 1 4 4 3 (2 ).

Subsection 2 of 28 U. S. C. §1443 allows removal by a

defendant of any prosecution “ [f]or any act under color of

authority derived from any law providing for equal rights.”

This provision, until recently, has seldom been litigated

and has never been construed in its application to circum

stances like those in the present case.3

2 Indeed, this court has recently summarily reversed several cases where

district courts failed to afford appellants a hearing on their §1443(1)

claims. Carmichael v. City of Greenwood, 5th Cir., No. 22289 (slip. op.

9/30/65; Galloway, et al. v. City of Columbus, 5th Cir., No. 22935 (slip,

op. 11/24/65) ; McNair, et al. v. City of Brew, 5th Cir., No. 22288 (slip,

op. 9/28/65); Weathers v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 986 (5th Cir.

1965) ; Robinson v. State of Florida, 345 F, 2d 133 (5th Cir. 1965).

3 The construction of §1443(2) urged by appellants McRay and Vivian

here is similar to that urged by Annie Lee Cooper and Stanley Leroy

Wise in an appeal now pending before this court. See, fn. 1, supra.

In Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark. 1963), removal

was sought of prosecutions for assault with intent to kill and for carry

ing a knife, charges arising out of a fight between the defendant and a

white student after rocks were thrown at the station wagon in which

defendant was escorting home from school two Negro students (one,

7

Appellants McRay and Vivian here contend: (A) that a

private person may invoke the “color of authority” pro

tection of §1443(2) if his conduct is encouraged or induced

by an equal civil rights law, because he thereby acts in a

quasi-official capacity; (B) 42 IJ. S. C. §1971 and an en

forcing judicial order are “law(s) providing for equal

rights” which protect, inter alia, acts such as those alleged

herein, which are an exercise of the freedom to encourage

voter registration; (C) that appellants McRay and Vivian

are being prosecuted for such authorized acts.

defendant’s niece) who had that day been enrolled under federal court

order in a previously segregated school. Defendant invoked §1443 (2) on

the theory that in escorting the children and in protecting himself and

them from persons who sought to frustrate enrollment, he was acting

under color of authority derived from the Civil Eights Act of 1960, under

which the enrollment order was made. The District Court assumed

arguendo that in some circumstances removal under §1443(2) was avail

able to a private individual charged with an offense arising out of his

act of escorting pupils to a school being desegregated under federal court

order, but held that this defendant, in his knife fight with the white

student, was not implementing the court’s integration order, since that

order made no provision for transporting or escorting the children to

school (in light of the previously peaceful history of the school con

troversy, by virtue of which, prior to the day of enrollment, there was

no reason to anticipate violence) ; hence there was no “proximate connec

tion,” 218 F. Supp. at 634, between the court’s order and defendant’s

fight.

In Hodson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (E. D. Pa. 1863), approved

in Braun v. Sauerwein, 10 Wall. 218, 224 (1869), Justice Clifford held

that a sufficient showing of “color of authority” was made to justify

removal under the 1863 predecessor of 28 U. S. C. §1443(2) where it

appeared that the defendants in a civil trespass action, a United States

marshal and his deputies, seized the plaintiff’s property under a warrant

issued by the federal district attorney, purportedly under authority of a

Presidential order, notwithstanding that the order might have been in

valid. For the facts of the case, see Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (Pa.)

412 (Strong, J. at nisi prius, 1863). This case established the proposition

that “color of authority” may be found where a federal officer acts under

an order which is illegal.

8

A. “Color of A uthority” and “Quasi-Official” Conduct.

Peacock, supra, restricted the category of persons who

could claim to be acting under “color of authority” by de

ciding that §1443(2)’s coverage “is limited to federal of

ficers and those assisting them or otherwise acting in an

official or quasi-official capacity.” 347 F. 2d at p. 686.

The referent to “those . . . otherwise” is not circum

scribed by the preceding “federal officers . . . and those

assisting them,” and would ostensibly embrace private per

sons not aiding or assisting federal officers,4 except for

the Peacock analysis of subsection (2). Peacock’s restric

tive reading of §1443(2), apparently excluding wholly un

official persons, results, in part, from an interpretation of

the present subsection “in the context of the Act (of

1866)6 as a whole” and the conclusion that the subsection

more readily encompasses federal officers or persons as

sisting them, because “that Congress (of 1866) was pri

marily concerned with protecting federal officers engaged

in enforcement activities.” 347 F. 2d at p. 686. Peacock

offered in support of this view the following summary of

the Act:

“Section 1, now 42 U. S. C. A. §1981, declared Negroes

to be citizens, conferred upon them various juridical

rights of citizenship, such as the ability to make and

enforce contracts, and guaranteed them the ‘full and

equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the secur

ity of person and property, as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

and penalties, and to no other . . . ’ Section 2 made it

4 The question whether wholly unofficial conduct is covered by §1443(2)

is the precise question pretermitted by the Second Circuit in People of

the State of New York v. Galamison, supra, see pp. 263, 264.

6 Act of April 9, 1866, eh. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27.

9

a crime to deprive persons of rights secured by the act.

Next followed the removal provision, now 28 U. S. C. A.

§1443. Sections 4-10 of the Act were devoted to com

pelling and facilitating the arrest and prosecution of

violators of §2. These sections, inter alia, authorized

federal commissioners to appoint ‘suitable persons’

to serve warrants, and allowed the persons so ap

pointed to ‘summon or call to their aid the bystanders

or posse comitatus of the proper county. . . . ” ’ (id.).

Thus, federal officers and persons claiming quasi-official

status through appointments by them can plainly do so,

but it must be presumed that the quasi-official concept was

not to be read to exclude all private actors, for to do so

would render the added words “those . . . otherwise act

ing” wholly redundant.

Apart from the history of subsection 2, the Peacock

construction reflects a concern that if §2 were not rationally

restricted it “would bring within its sweep virtually all the

eases covered by paragraph (1), thereby rendering that

paragraph of no purpose or effect . . . ” (347 F. 2d at

684).6

6 Though the concern of the Peacock court is understandable, it is

equally important that subsection 2 not be so construed as to render it

“of no purpose or effect” in those cases involving non-official actors to

which it legitimately applies. I t is not difficult to imagine situations in

volving non-official conduct in which the removal jurisdiction should be

sustained under §1443(2) when it apparently could not be sustained

under §1443(1) as that section has now been interpreted by this court.

For example, the court order on which appellants McRay and Vivian

ground their §1443(2) claim also protected those vouching for persons

seeking to register to vote. Assume that a native born white man of

Dallas County, without any connection with a civil rights organization,

undertook to act as voucher for a jsrospective Negro registrant and was

arrested by law enforcement officials of the county and charged with

breach of the peace, disorderly conduct, assault, etc. growing out of an

altercation with another white person (who objected to a Dallas County

native vouching for a Negro). And, assuming circumstances in which

10

“If paragraph (2) covers all who act under laws provid

ing for equal rights, as appellants contend, this require

ment could be avoided simply by invoking removal under

the second paragraph . . . We find no warrant for giving

paragraph (2) the strained and expansive construction

here urged” (ibid. 686).

What this court considered might require a “strained

and expansive construction” is obviated by the factual dis

tinctions between the case at bar and Peacock. In Peacock,

14 petitioners alleged that they were being prosecuted for

acts under color of authority of the Equal Protection

Clause and 42 U. S. C. §1971. Their contention was that

subsection 2 authorizes removal by any person who was

prosecuted for an act committed while exercising an equal

civil right under the Constitution or laws of the United

States. Cf. People of New York v. Galamison, 342 F. 2d

255 (2nd Cir. 1965); Board of Education of City of New

York v. City-Wide Committee for Integration, 342 F. 2d

284 (2nd Cir. 1965). Appellants’ narrower claim is that

their encouragement to Negroes seeking to register to vote

was not merely protected, but encouraged and induced by

a federal court order entered to enforce the provisions

of §1971. This claim is abundantly supported by the clear

language of the district court’s order, in Boynton v. Clark,

10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 215 (S. D. Ala. 1/23/65 modified

1/30/65), which read in part:

. . . People legally entitled to register should be

permitted to do so in an orderly fashion calculated to

the law enforcement officials were not present at the scene of the alterca

tion, and thus could not be said to have themselves been harassing the

defendant, removal jurisdiction could probably not be sustained under

§1443(1) as presently construed. But, quite clearly, it ought to be sus

tained under §1443(2) because at the time of the incident, the defendant

was “colorably” acting pursuant to the court order.

11

produce that result. And this court intends to see that

opportunity is afforded.

People who are interested in encouraging people

legally qualified to register have a perfect right to lend

such encouragement; and as long as this is sought

through peaceful assemblage, such assemblage is not

to be illegally interfered with.

* * * # #

What has heretofore been said applies to applicants,

both white and Negro. Those seeking to register and

those seeking to act as vouchers will form an orderly

line, not more than two abreast, from the entrance of

the office of the Board of Registrars down the corridor

of the court house in a line most direct to and through

the entrance of the Lauderdale Street door.

* * * * #

Those interested in encouraging others to register

to vote have the right peaceably to assemble outside

the court house, but shall not do so in such a way as

to interfere with lawful business expected to be trans

acted in the court house. Such persons also have a

right to peaceably assemble without molestation, and

will be permitted to do so; but violence, either by those

so assembled or officers entitled to surveillance over

such assemblages, or on the part of outsiders, will not

be tolerated at such assemblage.

* # * * #

This order in nowise is intended to interfere with

the legal enforcement of the laws of the State of

Alabama, Dallas County, or the City of Selma. But

under the guise of enforcement there shall he no in

timidation, harassment or the like, of the citizens of

Dallas County legitimately attempting to register to

vote, nor of those legally attempting to aid others in

12

registering to vote or encouraging them to register to

vote (10 Race Eel. L. Rep. at pp. 216, 217). (Emphasis

added.)

Appellants submit that their conduct, encouraged by a

federal court order, was under “color of authority” of that

order and 42 U. S. C. §1971, within the meaning of

Galamison, swpra, and that the ineluctable result of judi

cial conferment of “color of authority” is to make their

conduct “quasi-official,” hence removable within the Peacock

construction of §1443(2).

Galamison, in analyzing the “color of authority” lan

guage of §1443(2) decided that it would reach such private

persons whose conduct, similar to officers or their assis

tants, is directed by a specific statute or order:7

We gain a valuable insight into the meaning of

‘color of authority’ if we reflect on the cases at which

§1443(2) was primarily aimed and to which it indu

bitably applies—acts of officers or quasi-officers. The

officer granted removal under §3 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866 and its. predecessor, §5 of the Habeas

Corpus Act of 1863, would not have been relying on

a general constitutional guarantee but on a specific

statute or order telling him to act. Cf. Hodgson v.

Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. No. 6,568 (C. C. Pa. 1863), ap

proved in Braun v. Sauerwein, 77 U. S. (10 Wall.) 218,

224, 19 L. Ed. 895 (1869).9 A private person claiming

9 Cunningham v. Neagie, 135 U. S. 1, 10 S. Ct. 658, 34 L. Ed. 55

(1890), cited in the dissent, did not arise under a statute using- the

phrase “color of authority.” However, the specific direction of the

Attorney General to Neagie, 135 U. S. at 10 S. Ct. at 663, is a good

example of what would clearly constitute “color of authority.”

7 The Galamison court in part IV of its opinion discussed “color of

authority” after assuming, arguendo, that §1443(2) was not available ex

clusively to “officers or persons acting at their instance or on their be

half.” 342 F. 2d at p. 264.

13

the benefit of §1443(2) can stand no better; he must

point to some law that directs or encourages him to

act in a certain manner, not merely to a generalized

constitutional provision that will give him a defense or

to an equally general statute that may impose civil

or criminal liability on persons interfering with him.

(342 F. 2d at 264.)

Clearly, the concepts “quasi-official” and “color of au

thority,” as analyzed in Galamison, are interrelated and on

the present facts coincide. That is, where a private unof

ficial person “point[s] to some law that directs or en

courages him to act in a certain manner,” he acts under

“color of authority” of that law, but his acts are also

“quasi-official.” The impetus to appellants was the order

of a federal judge, and its directives were tantamount to

official appointment. To reject this view would create the

anomaly that the private person’s conduct, induced by a

federal judicial officer, must be considered less quasi-

official than conduct of the private person authorized by

an officer such as a federal marshal. Indeed, the conclusion

reached in Galamison that some unofficial actors can act

under color of authority would also be defeated.

B. Law Providing for Equal Rights.

It is clear that “any law providing for equal rights” in

28 U. S. C. §1443(2) means the same thing as the language

of §1443(1) : “any law providing for the equal civil rights

of citizens of the United States, or of all persons within

the jurisdiction thereof.” 42 U. S. C. §1971 is clearly such

a law, Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965),

for, even under the most restrictive possible construction

of the removal statute as referring only to laws “couched

in terms of equality, such as the historic and the recent

14

equal rights statutes,” People of New York v. Galamison,

supra, at p. 271, 42 U. S. C. §1971 plainly qualifies.

The right appellants assert under 42 U. S. C. §1971, and

the implementing court order,8 is freedom from prosecu

tion for encouraging voter registration of Negroes free of

racial discrimination recognized in U. 8. v. Wood, 295 F. 2d

772 (5th Cir. 1961); and U. 8. v. Clark, 10 Race Eel. L.

Rep. 236.

C. The Acts for W hich Appellants Are Prosecuted.

Under the construction of 28 U. S. C. §1443(2) advanced

in the preceding paragraphs, appellants McRay and Vivian,

prosecuted for acts in the exercise of §1971 rights, en

couraged by federal court order, may remove their prosecu

tions to federal court. That appellants’ petition brings

them within the statute so construed is evident. The peti

tion alleges facts, which appellees do not controvert, that

they are being prosecuted (1) for conducting and partici

pating in a voter registration campaign in Selma, Alabama

to secure registration of qualified Negroes, and (2) for en

couraging massive participation, despite the harassment

and intimidation of local law enforcement officials. After

U. 8. v. Woods, supra, and U. 8. v. Clark, supra, it can not

be doubted that such conduct is within the scope of consti

tutionally protected freedom of speech. Moreover, further

encouragement by a federal district court to engage in such

conduct, amply supports their claim to removal under the

authority clause of §1443.

8 That “law” within the meaning of §1443 is not restricted to consti

tutional provisions or statutes, is made clear at footnote 3, pp. 277-278

of Judge Marshall’s dissenting opinion in Galamison, supra, in which he

suggests that an Executive Order (thus, ipso facto a judicial order),

would plainly qualify (eases cited). Arkansas v. Howard, supra, ap

parently assumed, without discussion of this point, that an implementing

judicial order would qualify as such a law.

15

Of course, to establish the jurisdiction of a federal dis

trict court on removal, a defendant need not make out his

federal defense on the merits, and need not conclusively

show that his conduct was protected by the law on which

he relies. That defense is the very matter to be tried in the

federal court after removal is effected.9 To support fed

eral jurisdiction, it is sufficient that the acts charged

against the defendant be acts “under color of authority

derived from” a federal civil rights law. (Emphasis added.)

Absent a hearing, the issue central to §1443(2) removal,

whether appellants’ acts have a “proximate connection” to

the court order, see Arkansas v. Howard, supra, at p. 634;

cf. Maryland v. Soper, 270 U. S. 9, 33 (federal officer re

moval), cannot be determined. At the very least, appel

lants should be afforded an opportunity to demonstrate the

nexus between the state arrests and prosecutions and pos

sible conflicts with the district court’s order, hence, remov

ability. Rachel v. Georgia, supra; Peacock v. City of

Greenwood, supra; Robinson v. the State of Florida, 345

9 On the preliminary question of jurisdiction, it should be sufficient to

show colorable protection. This is the rule in federal-officer removal

cases, e.g., Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257, 261-62 (1880) ; Potts V.

Elliott, 61 F. Supp. 378, 379 (E. D. Ky. 1945) (civil case); Logemann

v. Stock, 81 F. Supp. 337, 339 (D. Neb. 1949) (civil case); E x parte

Dierks, 55 F. 2d 371 (D. Colo. 1932), mandamus granted on other grounds

sub nom. Colorado v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) ; Colorado v. Maxwell,

125 F. Supp. 18, 23 (D. Colo. 1954), leave to file petition for prerogative

writs denied sub nom. Colorado v. Knows, 348 U. S. 941 (1955), and it

was so held under the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863 removal

provisions, on which the Civil Rights Act of 1866 removal section was

based. See Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (No. 6568) (E. D. Pa.

1863) (civil case). The facts of the case appear in Hodgson v. Millward,

3 Grant (Pa.) 412 (Strong, J., at nisi prius, 1863) and Justice Grier’s

decision is approved in Braun v. Sauerwein, 77 U. S. (10 Wall.) 218, 224

(1869). Galamison takes this view, in dictum, under present §1443(2),

342 F. 2d at 261, 262. Cf. Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D.

Ark. 1963), where defendant was unable to make a colorable showing.

16

F. 2d 133 (5th Cir. 1965); Weathers v. City of Greenwood,

347 F. 2d 986 (5th Cir. 1965).

II. The Removal Petition Is Sufficient Under

28 U. S. C. § 1 4 4 3 (1 ) .

Appellants alleged, and the district court must have

taken as true (Rachel v. Georgia, supra; Cox v. Louisiana,

supra), that their arrests (R. 12) :10

. . . have been and are being carried on with the sole

purpose and effect of intimidating and harassing them

and of punishing them for, and deterring them from,

exercising constitutionally protected rights of free

speech and of assembly. . . .

This Court, in Rachel, supra, said that “ [u]nless there

is patently no substance in this allegation [that appellants

suffered a denial of equal civil rights by virtue of the un

constitutional application of the statute under which they

were being prosecuted], a good claim for removal under

§1443(1) has been stated.” 342 F. 2d at p. 340.

Appellants’ claim is substantial: that they are denied and

cannot enforce in the state courts a right under federal laws

providing for equal rights (viz., 42 U. S. C. §1971); the

equal protection clause, particularly, the right to be free

of official interference, through arrest, and prosecution,

for peacefully attempting to register and for encouraging

other Negroes to register to vote free of racial discrimina

tion.

10 In Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 679 (5th Cir. 1965), this

Court followed Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965) in up

holding the applicability of the rules of federal notice type pleading to

removal petitions. Thus, the “bare bone” allegation that appellants are

denied or cannot enforce in the courts of Alabama [R. 14] their rights

under the equal protection clause is sufficient. Peacock, supra, at p. 682.

17

The equal protection clause is clearly a “law providing

for equal rights.” Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d

679 (5th Cir. 1965); People of New York v. Galamison, 342

F. 2d 255 (2nd Cir. 1965), cert. den. 380 IT. S. 977 (1965).

42 IT. S. C. §1971 is equally clearly such a law (see discus

sion at pp. 13, 14, supra).

The right appellants assert under 42 IT. S. C. §1971 is

identical to that recognized in United States v. Wood,

supra, and United States v. Clark, supra, to freedom from

prosecution for peacefully attempting to encourage voter

registration of Negroes.

In Wood, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit held that John Hardy, a Negro voter regis

tration worker in Mississippi, had the right to be free from

state prosecution for peacefully attempting to encourage

Negro citizens to attempt to register to vote. Hardy was

arrested, without cause, for breach of the peace. The

Court asked, “The question then arises how the arrest and

prosecution of Hardy can irreparably injure these other

citizens [potential Negro voter in the county], if we must

assume that, Hardy will receive a fair trial and that his

acquittal is a possible result.” The Court answered, “that

the prosecution of Hardy, regardless of outcome [favor

able to Hardy] will effectively intimidate Negroes [gen

erally] in the exercise of their right to vote in violation of

42 U. S. C. §1971.” The Court pointed out that the “legisla

tive history of section 1971 would indicate that Congress

contemplated just such activity as is here alleged—where

the state criminal processes are used as instruments for the

deprivation of constitutional rights.” 295 F. 2d at 781. In

Clark, a three-judge Federal District Court enjoined law

enforcement officials from interfering in any way—through

arrest, prosecution or otherwise—with the right to advocate

18

the exercise of the right to vote. Wood and Clark are sol

idly supported by a compai’ison of 42 U. S. C. §1971(b) with

§203(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. A.

§2000a-2(c) and 42 IT. S. C. §1971(c) with §204(a), 42 U. S.

C. A. §2000a-3(a); as interpreted in Dilworth v. R,iner, 343

F. 2d 226 (5th Cir. 1965), the 1964 Act’s provisions accord

a right against prosecution for peacefully claiming the

right to equal public accommodations. Similarly, the 1957

Act’s provisions, as amended and codified as 42 IT. S. C.

§1971, accord a right against prosecution for peacefully en

couraging and assisting Negroes in attempting to register

to vote free of racial discrimination.

Appellants’ right to removal under 42 IT. S. C. §1971 and

§1443(1) is solidly supported by Rachel v. Georgia, supra.

In Rachel, sit-in demonstrators were prosecuted under a

Georgia anti-trespass statute which was nondiscriminatory

on its face; they removed their prosecutions to federal

court, alleging that the statute was being applied to them

in violation of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit up

held this claim, holding that §1443(1) allowed removal

based on the application of a state statute contrary to an

Act of Congress. The logic of this holding controls this

case, for the assault and battery and public drunkenness

statutes are being misapplied to conduct protected by 42

U. S. C. §1971.

Appellants also rely on the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, for their prosecutions are de

signed to thwart appellants’ efforts to assist Negroes to

register to vote. In Peacock v. City of Greenwood, supra,

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

applied Rachel to denials of equal protection, saying (347

F. 2d at p. 683):

19

Thus, Rachael allowed removal based on the alleged

application of a state statute contrary to an Act of

Congress, while the instant case involves the alleged

application of a state statute contrary to the equal

protection clause. The rationale of Rachel is inescap

ably applicable here, since both cases involve the denial

of equal rights through statutory application, rather

than through some infirmity appearing on the face of

the state statute.

Peacock involved the arrest of 14 civil rights workers in

Greenwood, Mississippi, whose prosecutions for obstruc

tion of public streets were removed to federal district court

under §1443(1). The district court remanded on the ground

that corrupt and illegal acts of state officials did not create

a denial of federally protected rights cognizable by §1443

(1). The Court of Appeals reversed holding that appel

lants’ allegation that the “[Mississippi] statute is being in

voked diseriminatorily to harass and impede [petitioners]

in their efforts to assist Negroes in registering to vote,”

was “sufficient to meet [the] test [of removal under §1443

(1)]” (347 F. 2d at p. 682). Peacock, in distinguishing Vir

ginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313, and Kentucky v. Powers, 201

U. S. 1, reasoned that while those cases11 limited removal

where the federal claim lay at “the very heart of the state

judicial process,” they could not be read as limiting §1443

(1) where the claim for removal is based on allegations

“that a state statute has been applied prior to trial so as to

deprive an accused of his equal civil rights in that the arrest

and charge under the statute were effected for reasons of

racial discrimination” (347 F. 2d at p. 684).

11 Including also, Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881); Bush V.

Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1883); and Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S.

565 (1896).

20

In Cox v. Louisiana, supra, the principle of these cases

was generalized as follows :

There is a common denominator in Rachel, Peacock

and Cox: The defendants, as a result of their actions

in advocating civil rights, are being prosecuted under

statutes, valid on their face, for conduct protected by

federal constitutional guarantees or by federal stat

utes or both constitutional and statutory guarantees.10

In essence, these guarantees rest on national citizen

ship, as opposed to state citizenship, not expressly rec

ognized until the three Civil War amendments.

In Rachel, Peacock, and Cox, and in similar eases,

there is no federal invasion of states’ rights. Instead,

there is rightful federal interposition under the Su

premacy Clause of the Constitution to protect the indi

vidual citizen against state invasion of federal rights.

10 See Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federally

Guaranteed Civil Rights: Federal Removal and Habeas Corpus Ju

risdiction to Abort State Court Trial, 113 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 793

(1965). (348 F. 2d at pp. 754, 755.)

Clearly, appellants’ allegations bring them within the

principles of Rachel, Peacock, and Cox, for they allege that

state statutes are being applied purposefully to thwart con

duct protected by federal constitutional or statutory guar

antees. Peacock, supra, and Rogers v. City of Tuscaloosa,

5th Cir., No. 21,700 (slip. op. 11/8/65), upon such allega

tions, mandate a hearing.12

Upon remand, appellants should be required to show no

more than that their prosecutions “are in reality prosecu

tions . . . for acts done in exercise of their federally pro

tected constitutional rights.” Rogers v. City of Tuscaloosa,

12 See also, cases cited at fn. 2, supra.

21

supra (slip. op. at p. 3). This would accord with several

recent decisions dismissing removed cases, after hearing on

jurisdiction, by the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Alabama. In Re Wright, et al., No.

11,739-N (M. D. Ala. 8/3/65); John L. McMeans, et al. v.

Mayor’s Court of Fort Deposit, Alabama, et al., No.

11,759-N (M. D. Ala. 9/30/65); Hughley, et al. v. City of

Opelika, No. 2319-E (M. D. Ala. 11/18/65). See also,

Forman v. City of Montgomery, 245 F. Supp. 17 (M. D.

Ala. 1965); Johnson v. City of Montgomery, 245 F. Supp.

25 (M. D. Ala. 1965). In Johnson, supra (remanded where

conduct found to be disorderly), District Judge Johnson

reasoned that no “peaceable, orderly and lawful demon

strations . . . (exemplified by In Re Wright) for purposes

of dramatizing grievances or protesting discrimination can

ever justify arrests and prosecutions . . .” (245 F. Supp.

at 25). Thus, where municipal ordinances are applied in

such a manner as to make constitutionally protected con

duct punishable, the arrests and prosecutions are invalid.

In Re Wright, supra; MeMeans, supra; Hughley; supra.

Upon such factual presentation, such prosecutions are not

only removable under §1443(1), hut under Peacock and

Rogers, dismissable.

22

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing* reasons, the order of the district court

remanding appellants’ cases should be reversed, or, at

the least, reversed and remanded for a hearing upon both

§1443 claims.

Respectfully submitted,

P eter A . H aul

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

J ack Greenberg

N orman C. A maker

Charles H . J ones, J r.

Charles S t e p h e n R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

23

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on December 8, 1965, I served a

copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants on the attorneys

for appellee listed below, by mailing copies thereof to them

by United States mail, postage prepaid:

P itts & P itts

Attorneys at Law

Selma, Alabama

Gordon- M adison

Assistant Attorney General

State of Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

B lanchard M cL eod

Circuit Solicitor, Fourth Judicial Circuit

Camden, Alabama

H enry F. R eese , J r.

County Solicitor

Dallas County Courthouse

Selma, Alabama

C harles H. J ones, J r.

Attorney for Appellants

MEiLEN PRESS INC. — N. V. C.-fiBa*.