Black Mayor in South Example of Success, Limitations of Voting Rights Act (Associated Press)

Press

December 30, 1986

2 pages

Cite this item

-

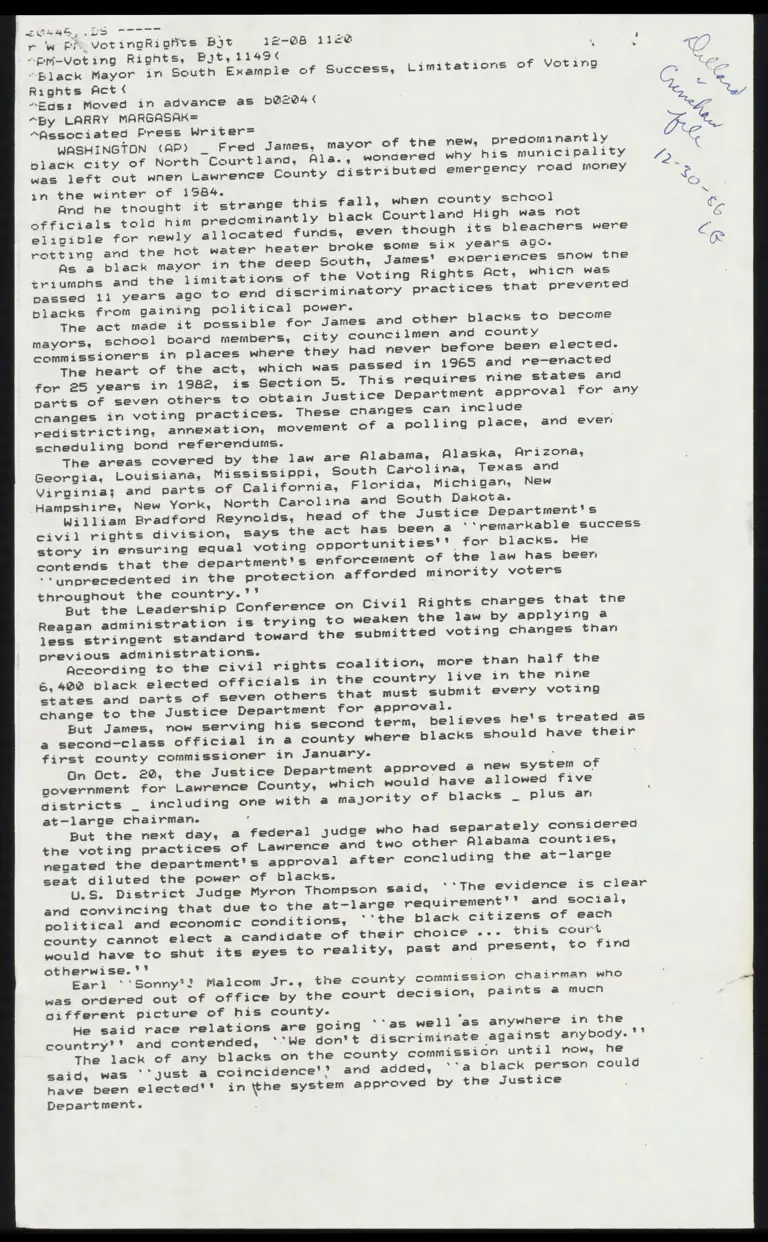

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Black Mayor in South Example of Success, Limitations of Voting Rights Act (Associated Press), 1986. 6a994edf-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/651e40c4-49f8-4e5a-b1b0-d7a9ce8427c4/black-mayor-in-south-example-of-success-limitations-of-voting-rights-act-associated-press. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

SRaah J "TTT

r 'w Fil VotingRights Bit 12-28 11ce

: . A

~pM-Vot ing Rights, Bat, 1145¢(

. ‘ 77

~Elack Mayor in Scuth Example of Success, Limitations of Voting : Lez

Rights Rct(

C

ei

~Eds: Moved in advance as baz4 (

~By LARRY MARBASAK=

“e -

~fesociated Fress Writers

a.

WASHINGTON (AP) _ Fred James, mayor of the new, predominantly ©

black city of North Caurtland, Rla., wonaered why his municipality >

was left cut wnen Lawrence County distributed emerpency road money ~

in the winter of 1584.

Yo

And he thought it strange this fall, when county school

Li

officials told him predominantly black Courtland High was not hk)

eligible for newly allocated funds, even though its bleachers were

rotting and the hot water heater broke some six years ago. =

As a black mayor in the deep South, James' experierices show the

triumphs and the limitations of the Voting Rights Act, whicn was

passed 11 years ago to end discriminatory practices that prevented

blacks from gaining pelitical power.

The act made it possible for James and other blacks to become

mayors, school board members, city councilmen and county

commissioners in places where they had never before been elected.

The heart of the act, which was passed in 1965 and re-enacted

for 25 years in 1982, is Section 5. This requires nine states and

parts of seven others to obtain Justice Department approval for any

changes in voting practices. These charges can include

redistricting, annexation, movement of a polling place, and even

scheduling bond referendums.

The areas covered by the law are Rlabama, Alaska, Arizona,

Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas and

Virginia; and parts of California, Florida, Michigan, New

Hampshire, New York, North Carclina and South Dakota.

William Bradford Reynolds, head of the Justice Department's

civil rights division, Says the act has been a * ‘remarkable success

story in ensuring equal voting opportunities’? for blacks. He

contends that the department's enforcement of the law has been

+ ‘unprecedented in the protection afforded minority voters

throughout the country. '?

But the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights charges that the

Reagan administration is trying to weaken the law by applying a

less strinpent standard toward the submitted voting changes than

previous administrations.

According to the civil rights coalition, more than half the

6, 422 black elected officials in the country live in the nine

states and parts of seven others that must submit every voting

change to the Justice Department for approval.

But James, now serving his second term, believes he's treated as

a second-class official in a county where blacks should have their

first county commissioner 1in January. :

On Oct. 20, the Justice Department approved a new system of

government for Lawrence County, which would have allowed five

districts _ including one with a majority of blacks _ plus an

at—laroe chairman. r

But the next day, a federal judge who had separately considered

the voting practices of Lawrence and two other Alabama counties,

negated the department's approval after concluding the at-large

seat diluted the power of blacks.

U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson said, '‘'The evidence is clear

and convincing that due to the at-large requirement'’ and social,

political and economic conditions, ° ‘the black citizens of each

county cannot elect a candidate of their choice ... this court

would have to shut its eyes to reality, past and present, to find

otherwise.’

Earl ®'‘Sonny'! Malcom Jr., the county commission chairman who

was ordered out of office by the court decision, paints a much

oi fferent picture of his county.

He said race relations are going as well as anywhere in the

country’?! and contended, ‘We don't discriminate against anybody. '’

The lack of any blacks on the county commission until now, he

said, was '‘Just a coincidence!!! and added, '‘a black person could

have been elected'' in {the system approved by the Justice

Department.

3 Y“ rere rave-been-very few instarices where blacks ran for

cffice,'! said Malcom. The county 1s appealing the court rulirg.

Until recently, blacks fared no better ain local polatics within

the county. For instance, there was no city of North Courtland

until June &, 1981, only the city of Courtland with some Z2V¥ whites

and a separate black area, known as ' ‘The Hill,’' with more than

90@ blacks. For years, '‘The Hill'' tried to be annexed into

Courtland.

‘Since we had been used for their pain, to get grants, we

wanted to be the controlling body, so the streets could be repaired

and homes rehabilitated,'® James recalled. '’'Courtland said it

gaian’t have enough money.

‘But some of the whites said it was because they gidn't want a

black person in City Hall as mayor. Blacks decided to po with their

own city, and it was incorporated June 2, 1881.1!

Now in his second term, James contends that county officials

‘ ‘make special cases out of the blacks. Any time I wanted the

county to do something to the roads, I had to pay the county up

front, before the service or ripht after. The county enpineer said

white cities didn't have to do that.’

Recalling the emerpency road money incident in 1384, James said

he called Commissioner Malcom to learn why his city failed to

receive its share.

‘Malcom didn't inform me we had to send a letter telling them

which roads reeded to be done,'’' James said. '‘He never said

anything until after the monies were issued.’’

Malcom tells it differently.

‘The (county highway) engineer notified all the cities they

needed to get a map of the streets and turn it in so we could start

work, '' Malcom said. '‘All the cities turned it in except Mayor

James of North Courtland.??

Malcom, who said a second black mayor in the county received the

money without a fuss, contended that ° “we went back later'' and did

the work for James. |

But the mayor said the county showed up with ‘a small dump

truck!? and laid about 200 feet of blacktop on less than half a

block of a city street. :

Then, James said, there was the case of the school money. As the

mayor told it, the county school superintendent informed him the

money was allocated for the white school 12 miles away.

‘ ‘Because of the dilapidated condition of our schools, we wanted

money for bleachers and upkeep of the schools. There was no hot

water in Courtland High School. The hot water heater had been

broken for six or seven years,'' James related.

But at a board of education meeting, James said, North Courtlanc

residents were told that the money was not limited to any

particular school, but based on need.

A board member, according to James, said '‘he was not poing to

sit and tell this lie. The local paper picked it up. It threw us

for @a loop.'! . :

After the incident, James said, lumber quickly came for new

bleachers and arranoements were made for a new water heater.

AP-WX-12-08-86 @95S6EST (

»

.