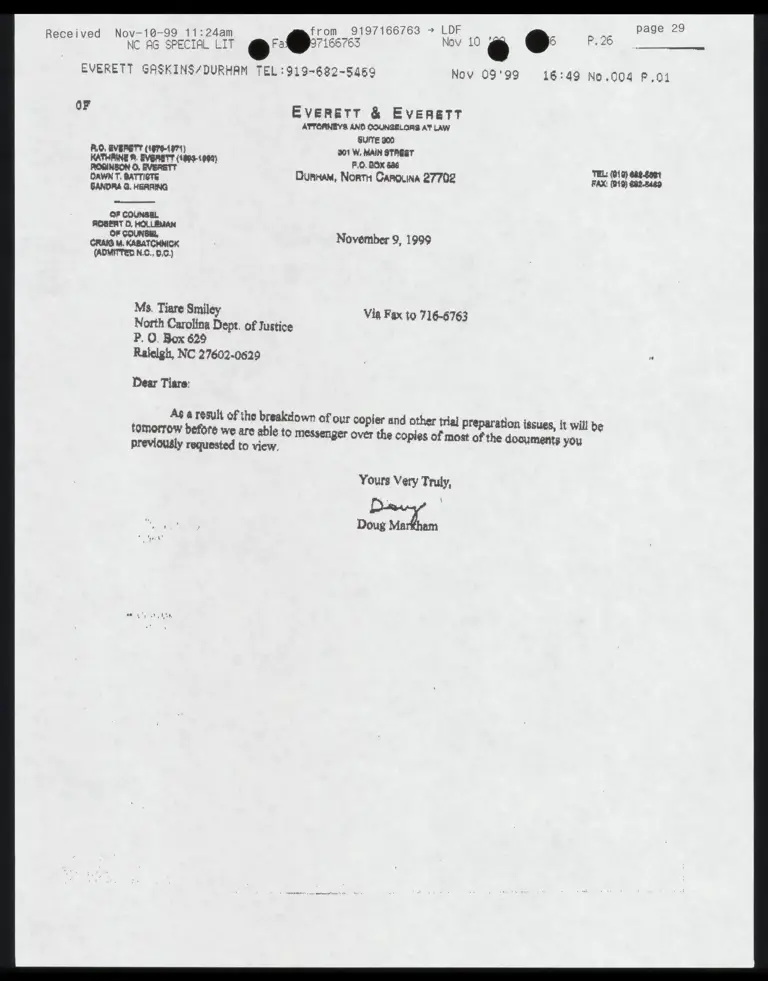

Fax from Everett RE: Letter from Markham to Smiley concerning document request

Correspondence

November 10, 1999

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Fax from Everett RE: Letter from Markham to Smiley concerning document request, 1999. bc0e7626-e90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/65230356-509e-4e34-9760-7b11f6290d86/fax-from-everett-re-letter-from-markham-to-smiley-concerning-document-request. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

page 29

6676 LDF -10-99 11:24am from 9197166763 hid al : DF

Rss ived pA AG SPECIAL LIT @®: 37166763 Mov 10 - B P.26

EVERETT GARSKINS/DURHAM TEL :919-682-5469 Noy 09'99 16:49 No.Q04 F.01

oF EVERETT & EVERETT

ATTEANEYS AND COUNSELORS AT LAW

SUITE 300

A. BVERETY (1878-1471) 201 W, MAIN STREET paring pi in (1993-1994) B.O. BOX 538 TEL @f

DAWN T. BATTICTS Dusan, North Carona 27702 FAX: rd ym PANDAS G. HERRING

OF COUNSEL

ROBERT D. HOLLEBMAN

OF COUNSES,

CRAKE M. KABATCHNICK November 9, 1999

(ADMITTED N.C., 0.0.)

Ms. Tiare Smiley Vig Fax to 716-6763 North Carolina Dept. of Justice

P.O Box 62¢

Ralelgh, NC 27602-0629

Dear Tiare:

As a result of the breakdown of our copier and other trial preparation issues, It will be tomorrow before we are able to messenger over the copies of most of the documents you previously requested to view.

Yours Very Truly,

i

Doug Mar¥ham

Received

Nov-10-99 11:24am from 9197166763 » LDF ; ; Tn

@ Mov 10 % : ; F.27 NC AG SPECIAL LIT ®

REDISTRICTING MATERIALS FOR

NCSL REDISTRICTING SEMINAR

NOVEMBER 7, 1999

AVOIDING A CHALLENGE UNDER THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE

AS INTERPRETED BY SHAW V_RENO, MILLER V. JOHNSON, AND BUSH V YERA

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

PO BOX 130923

HOUSTON, TX 77219-0923

713-655-8700

713-869-3255

713-655-8701 fax

dni PAS CATE

Eo

LDF

Received Nov-10-99 11:24am rom 9197166763 - r | P.2% x 3

1 NC AG SPECIAL LIT C3 ax 71667563 Mow 10 »

TOP TEN WAYS TO (TRY TO) AVOID A SHAW CHALLENGE

1. AVOID UNNECESSARY USE OF RACE. To the degree a neighborhood is defined in part

by rage, the inclusion of the entire neighborhood may be appropriate, To the degree an urban

area spills over a county line, the inclusion of the entire area, even if it has a racial character may

be an appropriate choice. To the degree neighborhoods are grouped in a clump and share a racial

character, keeping them together may be permissible. Otherwise, unless Section ? requires a district be created, and your approach is narrowly tailored, avoid the use of race.

2, USE WHOLE PRECINCTS AND COUNTIES. Respect precinet, city, and county

boundaries, especially where they reflect a geographic community of interest. The ideal world would be to draw up first the building blocks for your plan, the precincts, by having a

demographer look at housing patterns, common interests and the like, and then build a district from those units. Many precincts today are themselves racially gerrymandered, as a result of successful Section 2 claims from the era of forced “maximization ”

3. GROUP NEIGHBORHQODS COMPACTLY. Respecting traditional geographic areas of the

community, and using rommon traneport limles, &:0up precinets into clusters which are compact,

4. AVOID UNPOPUT ATED LAND BRIDGES. The use of npopulated and lightly populated land bridges to connect separated pockets of racially identifiable voters is a sign of the predominance of race. If you do not have a geographically compact minority group in your

jurisdiction, don’t fudge by linking widely separate pockets of minority. voters int a single district claiming & “fui liviial compactness” on the bags that all minorities in a rogien a's Lie sane.

3. CONSIDER USING IDENTIFIABLE BOUNDARIES. Major roads, rivers, or Interstate highways may serve as logical, non-racial boundaries for a district, and assist voters to know in which district they have been placed.

6. DO THE ANALYSIS OF VOTING BEHAVIOR. Race-based districts are often excused as being required to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Don’t make outdated, mistaken assumptions about black and white voting behavior. If as many as 20% of white voters support minority-preferred candidates, you probably do not have jegally significant polarized voting, Miuoiily voters may have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice in districts where they comprise 25-35% of the voters.

7 EQUALLY POPULATE ALL DISTRICTS. Given the realities of the size of your building blocks, make the populations as ¢qual as possible. Less than a 10% deviation in populations is not a safe harbor, even for state house ang senate plans, especially where thie Jovialions are racial in character.

8. BE INCLUSIVE. Keep the lines of communication open. It doesn’t help to claim that anyone who opposes segregated districts must be a Klansman.

hy IN

page 31

DF -190-99 11:24am rom 9197166763 - L AA rae iL , ha

Received Not F6 SPECIAL LIT PO Ze Nov 10 Ps. - P.29

9. BE PREPARED TO GO TO THE D.C. CIRCUIT TO GET PRECLEARANCE. The

Department of Justice has a poor track record for correctly interpreting the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Their political analysis is hopelessly outdated, and they

continue to push for bizarre districts and maximization despite the Supreme Court’s rulings.

Keep tuned for Bossier Parish,

10. DON'T SWEAT MINUSCULE DEVIATIONS. There is rarely sense in splitting a precinct

in order to structure congressional districts which are precisely equal in population. Given the

mobile nature of Americans, a quarter of a percent deviation in congressional districts (1000 or so

persons) should be acceptable to the courts and to common sense, in order to keep neighborhoods

and precincts intact.

SELECTED ISSUES IN REDISTRICTING FROM THE VIEW OF THE SHAW PLAINTIFF

PREFACE

The Voting Rights Act, designed at a time of one-party Democrat rule in the Deep South

is now increasingly applied in a two-party context, in areas of the New South and border South,

and in multiracial contexts. At the time of the Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. 8. 30, 106 S.Ct.

2752 (1986) decision, and until recently, Section 2 plaintiffs, many jurisdictions and the

Department of Justice assurned that black voters could only win in districts 65% black in total

population. In fact, there are now some jurisdictions where black voter turnout and registration

rates exceed that of white voters, and minority-preferred candidates usually win in districts in

which minority voters are only a plurality.

Houston, Texas, for example, has a robust history of electing candidates of choice of

Hispanic and black voters for more than 20 years. Candidates of each racial group have defeated candidates of each other racial group for the at-large positions. Since 1989 in contests for the at-

large positions Hispanics have defeated blacks (Saenz v. Clark, 1991; Sanchez v. Burks, 1997),

blacks have defeated Hispanics (Jackson Lee v. Castillo, 1989), blacks have defeated whites

(Clark v. Westmoreland, 1989; Robinson v, Kelley, 1991, Peavey v. Tyra, 1995), whites have

defeated blacks (Bell v. Dixon, 1997; Bell v, Johnson, 1997; Roach v, Wright, 1997), Hispanics have defeated whites (Sanchez v. Ballard, 1095), and whites have defeated Hispanics (Kelley v. C. Gorczynski, 1993)(In Texas the term “Anglo” in voting rights cases has come to mean non-Hispanic whites. Thus the many Houstonians of Czech, Polish, German, lalian, Greek, and Middle Eastern origin are by default “Anglo.”)

Candidates preferred by African-American voters have regularly won election as Mayor of the City of Houston over the past two decades. In 86 of 36 elections held in Harris County since 1988 in districts where blacks comprised 39.6% or more of the citizens of the district, a black candidate won, Every district in Harris County since 1988 which has been 43.2% or greater Hispanic by citizen voting age population has elected a Hispanic officeholder, and each has been the preferred candidate of Hispanic voters.

3-

: 2 . from 9197166763 >» LDF oe " o Received No 16 SPECIAL LIT eo ® EY . {x

l

Lo

The Chen v. City of Houston case, presently on appeal at the Fifth Circuit, and challenging city council districts, presents several issues of potential importance to post-2000 redistricting, including whether an unchallenged plan, despite unconstitutional characteristics, can serve as a benchmark for measuring retrogression. It may address whether gross differences in citizen population of districts present a Separate equal protection violation or whether purposeful undersizing of minarity districts is an independent equal protection violation.

WHAT IS RETROGRESSION ANYWAY, AND WHAT I$ THE BENCHMARK WHERE A DISTORTED SET OF DISTRICTS WAS NEVER CHALLENGED?

“Section 5 cannot be used to freeze in place the very aspects of a plan found unconstitutional.” Abrams v, Johnson, 521 U. 8. 74, 117 8. Ct. 1925, at 1939, 138 L, Ed, 24 285 (1997). The Chen District Court thus erred to find that there is “no legal basis” . . , “10 permit the review of plans that have become final” 9 F.Supp.2d at 760. The practical effect of such a determination has important implications for correcting race-based districting plans adopted across the nation in the 1990s. Every plan not previously challenged might be frozen into place, and governments will be forced to continue to contort districts to maintain the racial percentages present in the current districts. Current levels of minerity population in districts might be required even if the decade has seen as in Houston, an increasing willingness of voters of all races to support candidates of all races,

A different retrogression analysis is appropriate where the demographics of a city have changed as a result of an annexation. So long as the new districts “afford representation reasonably equivalent to [the minority voters'] political strength in the enlarged community,”

371 (1975). Otherwise, annexations could only occur if the annexed territory is adjacent to a district of the same racial character, and does not require reduction in the racial percentages of

WIDE VARIATIONS IN ADULT CITIZENS AMONG DISTRICTS

The packing of non-citizens into a few districts dilutes the votes of citizens in all other districts. The Constitution does not always compel a jurisdiction to use citizen population figures in constructing districts. In many jurisdictions the variations between citizen-based and total population-based plans would be minimal, See, Daly v. Hunt, 93 F.3d 1212, at 1216 (4th Cir. 1996)(plan urged by plaintiffs had 13.43% deviation in voting age population, while adopted plan had 16.17% deviation). Yet in those rare cases where total population does not assure equal voter strength among the districts, citizen VAP should be the basis for redistricting, Garza v.

will

page 33

> LDF a Spaan from 9197166763 BR od Received oy. i es ia eo @® = Mov 10 FA P. 31 |

County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, 918 F.2d 763, 778-788 (5* Cir. 1990)(Kozinski, J. concurring and dissenting in part) cert. den. 498 U.S. 1028 (1991). Alternately, in a setting where the differences in adult citizens Between districts is extreme, a City violates the Fourteenth Amendment to purposely gather non-citizens into a few districts and thus exaggerate the voter inequality of the districts.

The differences in equality in the Houston plan are not the sort of less extreme differences in Daly or approved by the Supreme Court in Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U. 8. 735 (1973). The raw disparity in citizen adult population among the nine districts exceeds 30%. Even taking the ability of residents in overpopulated districts to participate in elections for at-large members, a

page 34

greater than 20% disparity in voting power remains. See, Board of Estimates v, Morris, 489 U.S. 688 (1989).

The rationale for population equality of districts has traditionally been understood to provide fundamental equality of the political power of individual voters, wherever situated.

Simply stated, an individual's right to vote . . . is unconstitutionally impaired when its weight is in a substantial fashion diluted when compared with

citizens living in other parts of the State. . . .

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533, at 568 (1964). Accord, Hadley v. Junior College Dist, 397 U.S. 30, 56 (1970); Lockport v. Citizens Jor Community Action, 430 U. §, 259, 265 (1977)(all citizens have an equal interest in representative democracy”) Conrra, Garza v. C ounty of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, 756 F. Supp. 1298 (C. D. Cal), aff'd, 918 F.2d 763 (5th Cir. 1990), cers. den. 498 U. S. 1028 (1991); Daly v. Hunt, 93 F.3d 1212 (4th Cir. 1996)(rejecting view that Constitution views electoral equality as more important than representational equality).

RACE-BASED UNDERPOPULATION OF DISTRICTS

One scam for the past several decades is that suburban representation has had to struggle to catch up in every redistricting cycle. At the end of each decade, suburban districts are often 30 to 40% oversized. In order to achieve more racially pure minority districts, legislators often have undersized the minority districts. In order to compensate for an alleged undercount of minority persons, minority districts were also made smaller, (What politician would net like to represent a district, many of whose members could not be found on Census Day, and surely will not show up to vote him out of office on Election Day? Cf, “Institutional and military populatiofis are very attractive to politicians because they are counted in the total population of 2 district, but generally do not vote in that district.” Smith v. Beasley, 946 F. Supp. 1174 (D.C. S.C. 1996) ) I would expect suburban advocates in the post-2000 redistricting wars to show historically that their areas have been under represented continuously, and to urge consideration of projected growth as an element of district sizing.

Race-based underpopulation of districts independently violates the 14th Amendment. Even if citizenship distortions can be safely ignored, and a total population deviation less than

i

> LDF

Received Nov-10-99 11:24am rom 9197166763 be

~~ Foy

NC AG SPECIAL LIT @ T1667H3 Maw 10 FA ®

10% usually would entitle a government to a presumption of a valid districting plan, there is an

exception for unjustified, race-based decisions where districts for black and Hispanic members are

made smaller than those for white/Anglo members. Daly, 93 F.3d, at 1220. This policy of

awarding “shean RAAT’ tA Mitr amt smal oon fA . -