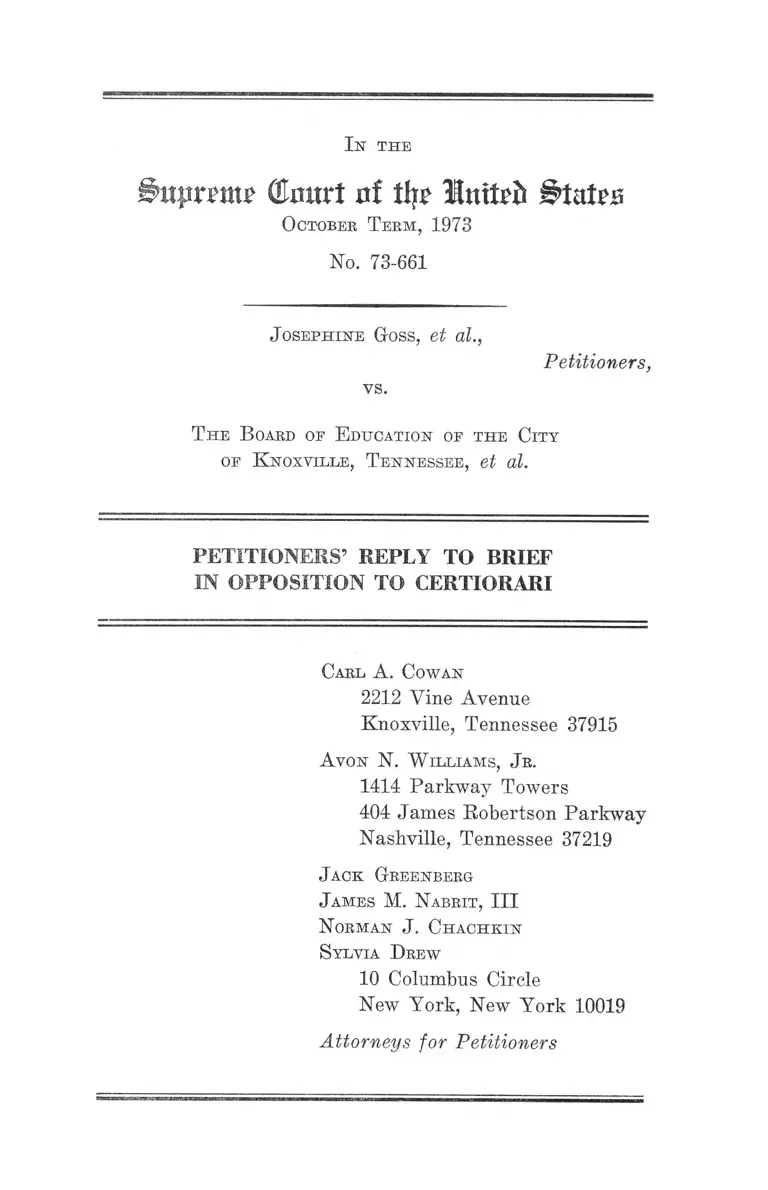

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petitioners' Reply to Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petitioners' Reply to Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1973. cb7b8bea-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6528891b-2128-42cb-a788-cfc18c40d892/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-petitioners-reply-to-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

! .\ THE

(Enrnrt nt % 1mt?ft

October Term, 1973

No. 73-661

J osephine Goss, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T he B oard oe E ducation of the City

of K noxville, T ennessee, et al.

PETITIONERS’ REPLY TO BRIEF

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Norman J . Chachkin

Sylvia Drew

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n th e

§>u+imni' GImtrt rtf tlj? States

October Term, 1973

No. 73-661

J osephine Goss, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T he B oard op E ducation of the City

op K noxville, T ennessee, et al.

PETITIONERS’ REPLY TO BRIEF

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

The Brief of Respondents [in opposition to certiorari]

fails to address the legal issues presented in the Petition,

but rather seeks to portray this case as one involving only

a factual question which was properly resolved below.

That characterization is inaccurate and misleading.

This Court’s review is essential to eliminate the exist

ing and potential conflicts among the Courts of Appeals

created by the Sixth Circuit’s decision in this case, and

to give meaning to the Fourteenth Amendment require

ment that a unitary school system be established in Knox

ville. More than fifteen years after the commencement of

litigation to desegregate the Knoxville schools, and more

than a decade after this Court’s rejection of the city’s

racially based transfer plan, Goss v. Board of Educ., 373

U.S. 683 (1963), 59% of all black children in this pre

dominantly white system attend heavily black schools.

2

Finally, it is imperative that this Court review this

matter to give badly needed guidance and direction to the

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. The en banc

rehearings in this case and in Mapp v. Board of Educ. of

Chattanooga, 477 F.2d 851 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 42

U.S.L.W. 3290 (November 12, 1973), have failed to re

solve any of the numerous conflicts among panels of the

Circuit on the question of school desegregation. District

courts within the Circuit have been left without counsel

for guidelines, as is readily reflected in the status of school

desegregation in the various Tennessee city school sys

tems.

I

As we pointed out in the Petition (pp. 8-10), the dis

trict court determined to deny the further relief sought

by plaintiffs based upon its erroneous legal conclusions

that (1) 99%-black schools are sufficiently integrated [340

F. Supp., at 717; 13a]; (2) plaintiffs’ demand for further

relief amounted to an attempt to achieve “racial balance”

[340 F. Supp., at 727-28; 23a-24a]; and (3) Knoxville’s

adoption of reasonable “neighborhood school” zones (in

place of the dual overlapping attendance boundaries it

maintained prior to 1964-65) satisfied the school board’s

constitutional obligation to convert from a dual to a uni

tary school system, whatever the resulting student enroll

ment patterns [340 F. Supp., at 718, 729; 14a, 25a].

The Court of Appeals adopted or approved these legal

declarations in its affirmance. Though not so explicit as

the district court in indicating the acceptability of mini

mally integrated facilities (see Petition, p. 9 n.16 and

accompanying text), the Sixth Circuit found the contin

ued maintenance of a “small number” of racially identifi

able schools in Knoxville to be valid (3a)—in spite of the

3

fact that seven black schools remain and there never were

more than nine black schools in the system at any time.

The Court of Appeals agreed (unlike the Fourth Cir

cuit’s perceptive holding in the Danville case, see Petition

at p. 9) that plaintiffs sought “to obtain a certain per

centage of black students in each school in the system” (4a).

And the court approved Knoxville’s compliance with the

Fourteenth Amendment with the statement that the system

“ha[d] taken [some] affirmative action to improve the

racial mix of the schools” (3a).

Each of these issues is of critical significance in school

desegregation cases; each has been resolved by other

Courts of Appeals in a manner inconsistent with the hold

ings of the Court of Appeals and district court herein, and

each merits review by this Court. Cf. Rule 19(1)(b) of

this Court. Yet the respondents totally decline to support

the erroneous legal rulings of the courts below. Instead,

they suggest that only factual questions can be presented

to this Court, because the Court of Appeals summarily dis

missed claims of inconsistency with its other rulings with

the statement that “the proof . . . failed to establish [the

basis for the results reached in the other cases].”

The Court of Appeals did say:

. . . the appellee presented evidence . . . from which

the [district] court was justified in finding that no plan

involving the transportation of pupils . . . would be

feasible. . . . (3a-4a)

But as we pointed out in the Petition (p. 13), the district

court never made such a determination. Although it dis

cussed some of the geographic and demographic features

of Knoxville in summarizing the evidence, it made no

factual findings on the subject since the court held the

4

system was already “unitary” and that further desegrega

tion attempts were efforts to achieve “racial balance.” Thus

it is legal doctrine and not fact finding which is placed in

issue before this Court.

II

Respondents minimize the fact that even after this case

received district court reconsideration in light of Swann,

59% of all black students in this more-than-80%-white

school system were assigned to identifiably black schools

(Petition, at p. 7). This is unexpected in view of their

admissions that zone lines have not been substantially

altered since they first became effective at all grade levels

in 1964 (Brief, pp. 11-12) and that at the time they received

judicial sanction, this Court had not yet announced the

result-oriented standards of Swann and Davis v. Board of

School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) (Brief, p. 8). As we

said in the Petition (at p. 12), it is hardly surprising, given

the racial residential segregation existing when this suit

was brought and continuing to this day (340 P. Supp., at

716; 12a), that “neighborhood school” zones have resulted

in school segregation. See Swann, 402 U.S. at 28.

The 1971-72 enrollment figures, enumeration of which

respondents label a “static presentation,” (Brief, p. 4)

were not represented as current (see Petition at p. 7). They

were listed, however, to emphasize the gravity of the dis

trict court’s error in characterizing the school system as

“unitary.” The Court of Appeals compounded the error

by lifting out of context Swann’s reference to a “small

number” of racially identifiable schools, and applying it

to Knoxville, which has never had a “large number” of

black schools. The meaning of the phrase varies with the

history and circumstances of each school district: even one

5

such school would have been unacceptable in New Kent

County, Virginia.

It is undoubtedly true that in 1971, Knoxville at long

last took “[some] affirmative action to improve the racial

mix” in its schools. It finally paired schools whose com

bination had been recommended years ago by the Univer

sity of Tennessee Title IV Center. See also, U.S. Comm’n

on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation in the Public Schools 65

(1967). But the continued assignment of three-fifths of

Knoxville’s black students to heavily black schools is elo

quent evidence of Knoxville’s failure to take “all necessary

steps” to eliminate racially identifiable schools, in satisfac

tion of its constitutional obligation.1

Ill

Certainly there is a place for proper fact-finding in this

litigation. Petitioners have on the several appeals of this

case presented to the Sixth Circuit flagrantly erroneous

findings of the trial judge. We have never succeeded in

having these reviewed, either because the Court of Appeals

has simply remanded the case for reconsideration (as in

1964 and 1971) or because the questions are ignored (as in

1973). For example, the district court stated that transfer

forms for Austin-East High School (see Appendix A)

introduced into evidence could not support the testimony

of plaintiffs’ educational expert witness that the school

system’s transfer practices had perpetuated segregation

(340 F. Supp., at 725-26; 21a-22a). Not only had the dis

trict court itself previously suggested as much (340 F.

Supp., at 719; 15a) but Petitioners reproduced all of the

transfer forms in the Appendix in the Court of Appeals,

pointing out the abundant indications that white students

1 Appendix A hereto provides a very brief summary of Knox

ville’s school desegregation history.

6

were permitted to transfer out of the paired high schools

for racial reasons.2 * * * * * 8

In similar fashion, the district court criticized plaintiffs’

educational expert for not using- the board’s pupil locator

data in drafting his plan (340 F. Supp., at 721; 17a) even

though the court itself found the data was inaccurate (340

2 We summarized the transfer forms in our Court of Appeals

brief as follows:

The forms are all from white students (see master listing at

A. 1567-70). There are transfer requests from 51 students—

some having repeatedly sought transfers—in the Austin-East

zone. Not all of the students listed as having transferred at

A. 1567-70 are represented in the transfer requests; their

forms may have been lost.

Of the 51 students, 20 of their latest requests were approved

and 29 were denied; the other two students had submitted

forms unnecessarily after changing their addresses and mov

ing into another zone. Only six of the twenty-nine white

students whose requests to transfer out of Austin-East were

denied remained at the school: LaVerne Cox, Mary Green,

Miriam Kenimer, Larry Patty, Alan Rogers, Eursal Payne.

8 whites whose transfer forms are marked “disapproved” are

shown on the master listing as having obtained transfers and

subsequently been graduated from Fulton, Holston or Rule.

Among these, incredibly enough, is one Brenda Keeling (A.

1597-98) ; in the winter of 1967 Miss Keeling’s request to

transfer from East to Rule

Because of the colored. They are a colored boy that is

causing trouble in a way which I don’t improve of;

causing talk [A. 1598]

was denied. In the spring of 1968 another request to trans

fer, this time from East to Fulton because of the “racial situ

ation” (A. 1597) was disapproved. Yet the school system

reports (A. 1567) that Miss Keeling was a Holston graduate!

Another example is Miss Becky Suffridge (A. 1634), who

sought a transfer because she was “socially deprived.” Al

though it was denied, she is listed (A. 1567) as a Fulton

graduate.

Some of the approvals are equally interesting. Two were

granted because of racial complaints (Larry and Vicki Pick

ens, A. 1617-20). Five other transfer requests were granted

despite previous disapprovals of the same or similar trans

fer pleas. For example, Eddie Parton first sought transfer

7

F. Supp., at 713; 9a) and the school board’s expert also

declined to use it for this reason (A. 413-14). These and

other serious factual errors made by the district court were

brought to the attention of the Court of Appeals but were

never addressed by that Court.

To the extent that factual matters are made relevant in

this case by the correction of the legal mistakes committed

below, the Court of Appeals should have set aside numerous

district court findings as being “clearly erroneous.”

IV

The failure of the Court of Appeals to deal with the

legal and factual issues presented by the district court’s

ruling in this ease corresponds to that Court’s refusal to

fashion a consistent body of school desegregation law in

accord with this Court’s decisions and applicable through

out the Circuit.

We pointed out in the Petition (p. 12) that the decision

below conflicts with other Sixth Circuit rulings approving

or ordering extensive desegregation of school systems using

pupil transportation. In this respect, it is similar to previ-

in early 1968 on the ground that it was inconvenient for

him to attend Bast (A. 1612) ; his request was denied. In

late spring, 1968, he again sought to change schools because

of “emotional difficulty in adjusting to a specific situation”

(A.' 1611) (a phrase which appears with annoying regularity

on many transfer forms). That was denied, and in August,

1968 he filed another request to transfer to Fulton because

he “wants to learn a trade” (A. 1610). This request was also

denied, but a school official wrote on the form, the words

“What Trade?” Finally, on September 4, 1968 Parton got

the message, requested transfer so as to take “machine shop,”

which was not offered at Austin, and was granted his trans

fer (A. 1609). James Dockery was denied a vocational trans

fer in the summer of 1967, appealed to the school board and

lost (A. 1588) ; yet the following winter he was granted a

vocational transfer (A. 1587).

8

ous panel opinions which affirmed district court orders

allowing the continuation of segregated schools on the basis

of “district court discretion.” E.g., Robinson v. Shelby

County Bd. of Educ., 467 F.2d 1187 (6th Cir. 1972). For

years, such unresolved conflicts among panels of the Cir

cuit concerning the necessity for substantial integration,

what constituted “racial balance,” etc., left district courts

and litigants alike without any guidance except the latest

utterance of a panel.3

We had hoped that these conflicts, which produced mark

edly different levels of desegregation in the public schools

of Tennessee’s major cities (see Petition, p. 12 n.19), would

be resolved by the full Court in the first en banc considera

tions of school desegregation cases it had ever scheduled,

in the Mapp and Goss cases. However, in each instance,

the Court of Appeals merely affirmed the district court

without analyzing the legal issues presented, dismissing

any conflict with the “brief answer” that the proof was

different in each case (4a). Mapp v. Board of Educ., 477

F.2d 851 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3290 (1973);

Goss v. Board of Educ., 482 F.2d 1044 (6th Cir. 1973). The

uncertainty about the legal requirements continues through

out the Circuit.* 4 We respectfully suggest that the Sixth

Circuit’s refusal to establish Circuit-wide standards to end

the confusion created by its own decisions in this important

8 Thus, for example, the Chattanooga School Board claimed

that after an initial ruling in its case based upon Kelley v. Met

ropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970) and

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 442 F.2d 255 (6th Cir.

1971), “ [t]he District Court appeared to shift emphasis on the

basis of Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville

[1971] . . . ” Brief for Defendant-Appellee and Cross-Appellant,

6th Cir. No. 71-2006, -2007, p. 15.

4 Indeed, the City of Chattanooga sought to support its request

for review by this Court by pointing to the later en banc decision

in Goss. Petition in No. 73-188, p. 12.

9

area of public law warrants the exercise of this court’s

supervisory revieŵ power. See Rule 19(1) (b) of this Court.

Symbolic of the conflict is the Court’s en banc ruling in

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir.), cert, granted,

42 U.S.L.W. 3306 (1973). It is remarkable that the same

Court which contemplated the exchange of pupils, pre

sumably by bus, between Detroit and its' suburbs, to effec

tuate desegregation, also affirmed the continuation of

segregation in the much smaller Knoxville system. But

this Court’s decision in the Bradley case on the remedial

issue there presented—whether the Court has the power

to go beyond the district boundary line—will not settle the

issues presented by this case, nor furnish the necessary

guidance to other Sixth Circuit litigants in school desegre

gation actions. Wholly irrespective of the Court’s deter

mination in Bradley, this cause should be reviewed in

order to enforce the commands of Swann and the Four

teenth Amendment in Knoxville and throughout the Sixth

Circuit.

10

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, as well as those set out in the

Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Petitioners respectfully

pray that the Writ he granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

N orman J. Chachkin

Sylvia Drew

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX A

History of School Desegregation in Knoxville

1957 First federal court desegregation action filed

1959 Case dismissed without prejudice on procedural

grounds

1960 Present litigation instituted. Board submits grade-

a-year plan with minority-to-majority transfer; ap

proved by district court

1962 Initial assignments of students in several elementary

grades based on single zone lines; dual zones are

maintained for other grades. Court of Appeals ap

proves minority-to-majority transfer

1963 Supreme Court disapproves transfer feature

1964 Plan covers elementary grades. Explicit minority-

to-majority transfer discontinued but plan permits

“grade requirement” (remain in school previously

attended until graduation) and “brother-sister” (go

to schools attended by other family members) trans

fers. Plaintiffs’ appeal dismissed on representation

of board attorney that “all discriminatory practices”

would be eliminated by 1965

1965 Zones established for all grades. Broad transfer

provisions continue in effect

1967 District court holds transfer provisions facially valid

and finds no gerrymandering of zone lines. 68% of

all black students assigned to 9 schools more than

95% black

1968 Board “pairs” formerly black Austin High and for

merly white East High but permits transfers to

2a

I1 niton for vocational courses, etc. Few white stu

dents attend combined Austin-East High School

1969 Court of Appeals affirms district court, holding that

attendance patterns without showing of gerryman

dering do not establish constitutional violation in

formerly dual school system, as in historically uni

tary system, citing Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ.,

369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 TT.S.

847 (1967)

1970 In response to plaintiffs’ Alexander [v. Holmes

County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969)] motion,

district court holds system “unitary,” but criticizes

board for failing to keep transfer records sufficient

to explain non-attendance of white students at Aus

tin-East complex (320 F. Supp., at 557) and to elim

inate overcrowding and underutilization of adjacent

predominantly white Rule High and predominantly

black Beardsley Jr. High (320 F. Supp., at 556)

1971 Court of Appeals remands for reconsideration in

light of Swann, recognizing that new standards re

quire reassessment of past holdings and that Swann

“forbids the use of our decisions in Deal . . . to jus

tify a plan of desegregation in a state which em

ployed de jure segregation until the Brown decision”

(444 F.2d, at 639)

1972 After new round of hearings, district court again

holds system was unitary despite maintenance of

seven all-black schools since neighborhood school

zones are reasonably drawn. Court allows board to

implement school closings and pairings it proposed

after Swann remand from Court of Appeals

1973 Court of Appeals affirms district court ruling. 59%

of black students assigned to heavily black schools

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. «*S§|§&> 219