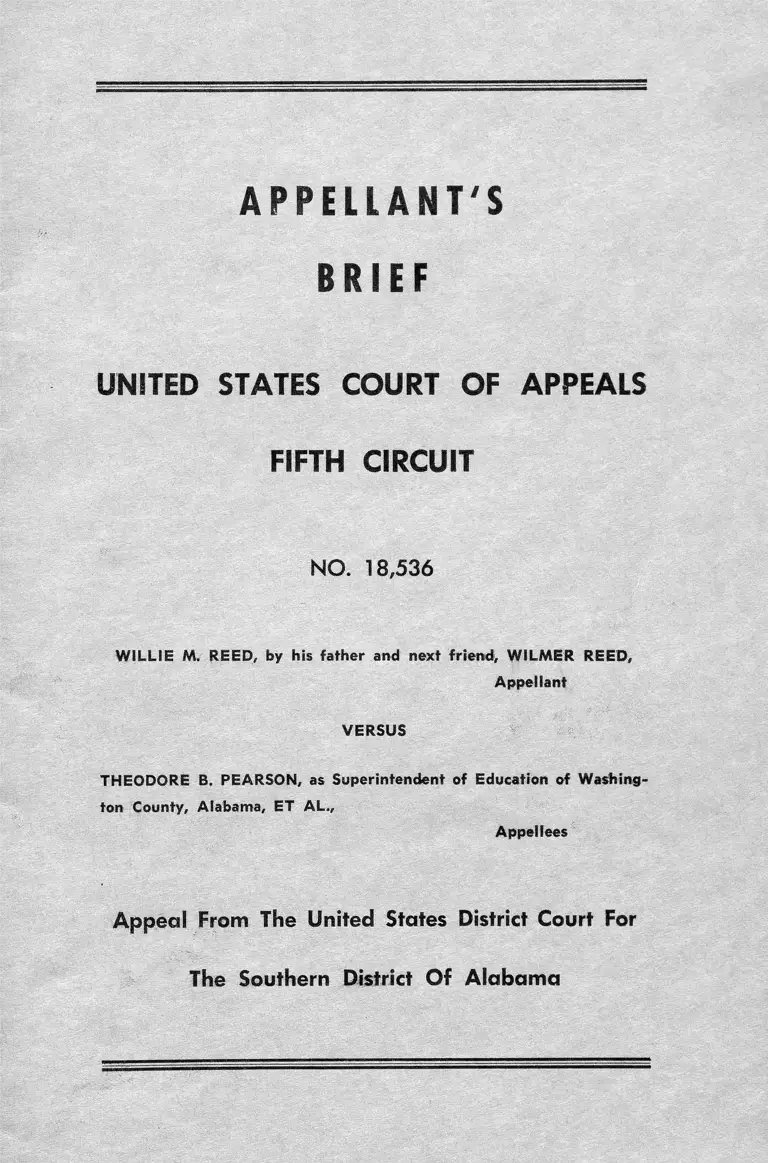

Reed v. Pearson Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

February 28, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reed v. Pearson Appellant's Brief, 1962. 9aafe3e2-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/654a3237-0c49-4351-a9a0-8bea7a36502e/reed-v-pearson-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

APPELLANT'S

BRIEF

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 18,536

W ILLIE M. REED, by his father and next friend, WILMER REED,

Appellant

VERSUS

THEODORE B. PEARSON, as Superintendent of Education of Washing

ton County, Alabama, ET AL.,

Appellees

Appeal From The United States District Court For

The Southern District Of Alabama

I N D E X

Page

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ....................................................................... 1

FACTS .............................................................................................................. 1

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS ..................................................................... 3

ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................... 4

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ....................................................................... 10

CASES CITED

Page of Brief

Brown V. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483,

74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 ........................................................................... 4

Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U. S. 294, 99 L. Ed. 1083, 75 S. Ct. 753 ............................................. 4

Cooper V. Aaron, 358, U. S. 1, 20, 3 L. Ed.

2d. 5, 19, 78 S. Ct. 1401 ................................................................................. 4

Shuttlesworth V. Birmingham Board of Education,

358 U. S. 101, 79 S. Ct. 221, 3 L. Ed. 2d 145 ........................................... 4

Carson V. Board of Education of McDowell County,

227, F. 2d 789 ................................................................................................. 5

Joyner V. McDowell County Board of Education,

244 N. C. 164, 92 S. E. 2d 795, 798 ............................................................ 6

Carson V. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, Cert, denied

353 U. S. 910, 1 L. Ed. 2d 664, 77 S. Ct. 665 ............................................. 6

Lane V. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 274, 59 S. Ct.

872, 83 L. Ed. 1281 ....................................................................................... 7

Henderson V. United States, 339 U. S. 816,

824, 70 S. Ct. 843, 94 L. Ed. 1302 ........................................................... 7

Griffith V. Board of Education of Yancey County,

186 F. Supp. 511 ............................................................................................ 8

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. V. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59, 63, 64 ...................................................................................... 8

Gibson V. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, 246 F. 2d 913 .................................................................................. 8

Bush V. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp.

337, 34, Affirmed in 242 F. 2d 156 ........................................................... 8

Gibson V. Board of Public Instructions of Dade County,

Florida, 272 F. 2d 763 .................................................................................. 8

McCoy V. Greensboro City Board of Education,

283 F. 2d 667 ................................................................................................ 9

CODE SECTIONS

Tit. 52, Section 298, Code of Alabama .................................................. 11

Tit. 52, Sec. 61 (1), et seq., Code of Alabama

(also known as the Pupil Placement Law of Alabama) ....................... 11

WILLIE M. REED, by his father and next friend, WILMER REED,

Appellant

VERSUS

THEODORE B. PEARSON, as Superintendent of Education of Wash

ington County, Alabama, ET AL.,

Appellees

NO. 18,536

A P P E L L A N T ' S B R I E F

STATEMENT OF CASE

The appellant, plaintiff below, filed his suit in the United States

District Court, Southern District of Alabama, to require certain of ap

pellees, who are the Superintendent of Education and County Board of

Education of Washington County, Alabama to admit him as a student in

a public school of Washington County, Alabama from which he is

alleged to be excluded because of race or color in violation of Civil

Rights Act, Section 1983, Title 42, United States Code, and the Constitu

tion of the United States. (Pages 1 through 20 of the transcript.)

The appellees filed a motion to dismiss. (Pages 23 and 24 of the

transcript.)

After oral argument on the motion to dismiss the Honorable Daniel

H. Thomas entered an order granting the appellees motion to dismiss,

but failed to state on which grounds of appellees motion the order was

granted, or his reasons therefor. (Pages 24 and 25 of the transcript.)

Upon the appellants failure to amend his complaint to meet the

ruling of the Court, the Court then entered an order finally dismissing

the appellants complaint. (Page 25 of the transcript.)

It is from these two orders of the Court that this appeal is prose

cuted.

FACTS

The appellant was born on September 24, 1954 and was of the age

of 6 years on September 24, 1960 and prior to October 1, 1960. Title 52,

Section 298, the Code of Alabama provides: “ A child who is six years

of age on or before October 1st shall be entitled to admission to the

public elementary school at the opening of such school for that year or

as soon as practicable thereafter.” The appellant lives 1.2 miles from

Reeds Chapel School, a public elementary school in Washington County,

1

Alabama, which is attended by the appellants neighbors, relatives, and

the children in the community and area in which appellant lives. There

is no other public school in that community.

Prior to the opening of school in the fall of 1960 appellant’s father

received a letter from the trustees of Reeds Chapel School advising him

that his child (appellant) would be denied admission to said school be

cause “ it is our desire to postpone integration as long as possible in

Alabama and because of the resolution which had been passed by the

Washington County Board of Education placing children in the same

school attended by their parents and stating that placement of new

students would be made by the Board of Education.

On August 23, 1960, the appellant’s father wrote the School Board,

“ I formally apply to you for the placement of my child in a school for

the 1960-61 school year and request that you inform me of this place

ment as soon as possible in order that I might have it in time to enroll

my son, Willie Reed, in school on September 1, 1960.” (Page 12 of the

transcript.)

The above letter was read by the School Board at a meeting on

August 25, 1960 but the Board took no action on it other than setting a

hearing on the matter for the last Friday in September, 1960. (Page 14

of the transcript.) The Board also advised the appellant’s father of the

resolution they had passed and which had been given as one of the

reasons that the trustees were denying the appellant admission to the

school in his community. Appellant alleges that said resolution is arbi-

tuary and unconstitutional in that it has as its purpose the denial of

his admittance to a public school in Washington County, Alabama, be

cause of his race or color.

As directed by the Washington County Board of Education the

appellant and his attorney met with the Board on the last Friday of

September, 1960, and presented to the said Board of Education all facts

which were relevant to the admittance of appellant as a pupil in Reeds

Chapel School. The Board did not advise appellant or his attorney of

any decision made in the matter but wrote the appellant’s father on

November 30, 1960 and requested that he meet with the trustees of

Reeds Chapel School on December 3 for the purpose of discussing the

situation stating that “ it was the opinion of the Board that if you and

the trustees would meet and discuss the matter, that a reasonable solu

tion could be obtained.” (Page 17 and 18 of the transcript.) Appellant’s

father met with the trustees of Reeds Chapel School as requested and

their meeting resulted in an agreement and understanding that appellant

would be admitted as a pupil in Reeds Chapel School beginning after the

Christmas Holidays and. on January 3, 1961. This agreement and under

standing was apparently acquiesced in by the Washington County Board

of Education because one member of the Board subsequently told ap

pellant’s father to enroll his child ih the school on that day.

Appellant was enrolled as a student in Reeds Chapel School on Jan

uary 3, 1961 and attended the school through January 6, 1961. On Jan

uary 6, 1961, the appellees Minnie Reed, Maggie Jane Orso, Viola Snow

2

and Virginia Weaver appeared at the school and created a disturbance

and threatened further disturbances and violances if appellant was not

expelled from the school. The principal of the school, Mrs. Margaret

Dickinson, dismissed the school early on January 6, 1961 and sent the

children home because of threats and disturbances and the school was

closed for the period January 9-13, 1961.

By letter of January 11, 1961, the Washington County Board of

Education advised appellant’s father that his child “ is not for the time

being placed in the school.” The Washington County Board of Education

sent the appellant’s father a copy of their letter to the principal and

teachers of Reeds Chapel School of January 11, 1961 instructing them

to re-open the school on Monday, January 16, 1961, and instructing and

notifying them “ to enroll, teach and give report cards to only those

pupils who were enrolled and in attendance prior to the Christmas Holi

days which began on December 16, 1961,” and which had the effect of

expelling appellant from school.

Appellant’s complaint set out that the community of Reeds Chapel

is populated by a people of mixed blood, that appellant’s grandfathers

were a part of this mixed blood group and were related to the great

majority of the patrons of Reeds Chapel School, that appellant’s grand

mothers were not of this mixed blood group, and that appellant was

being denied admission to this school because of his race and color

acquired through his grandmothers.

The complaint further sets out that the appellant has diligently

attempted to exhaust the administrative remedy for his placement in

school as provided by Title 52, Section 61 (1), et seq, of the Code of

Alabama, that the Board of Education of Washington County, Alabama

has unreasonably, unnecessarily and arbitrarily delayed the making of

a decision for the placement of petitioner in a public school, resulting

in the deprivation of appellant’s right to a public education for and on

account of his race and color.

Appellant concludes his complaint with the following prayer:

“ Wherefore, the premises considered your petitioner prays and

moves this Honorable Court upon the presentation of this complaint to

cause such proceedings to be had in the premises and to enter such

orders and decrees as will cause your petitioner to be enrolled in Reeds

Chapel School, a public school inWashington County, Alabama, without

discrimination against him by race or color and as will afford to your

petitioner protection in his civil and constitutional rights in the

premises;

Pettioner prays for all such other, further and general relief as to

which he may be entitled, the premises considered, as petitioner will

ever pray, etc.”

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS

1. The trial court erred in its order of July 7, 1961, granting the

defendants motion to dismiss the appellant’s complaint.

3

2, The trial court erred in its order of August 21, 1961 dismissing

the appellant’s complaint.

ARGUMENT

The District Court Judge neglected to tell us which, if any, of the

defendants grounds of motion to dismiss he granted their motion on.

We can, therefore, only speculate as to his reasons and present the

reasons why he should not have dismissed the complaint as best we can.

For many years prior to 1954, the Supreme Court of the United

States had stood by its doctrine that “ separate but equal” school facili

ties for negroes, raided bloods and whites satisfied the constitutional

requirements of equal protection of the law and equal privileges to all

Citizens of the United States.

May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court overruled this long established

doctrine in Brown V. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686,

98 L. Ed. 873, and held that separation by race and color of school stu

dents, though teachers, curricula, and facilities might be equal, was

inherently discriminatory and contrary to the requirements of the Con

stitution of the United States.

In Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294, 99 L, Ed.

1083, 75 S. Ct. 753 the Supreme Court, in what has been called the im

plementing decision, held that the district courts can best resolve the

questions arising in the transition from equal but separate schools to the

new order and that in doing so they should be guided by equitable

principles. This decision was reaffirmed in Cooper V. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1,

20, 3 L. Ed. 2d 5, 19, 78 S. Ct. 1401 wherein it was held that the princi

ple was not to be sacrificed or yielded to violence and disorder.

In order to delay, oppose or nullify the principles declared by the

Supreme Court the various Southern legislatures passed numerous acts

with more haste than reason. A common name given to one such act is

the Pupil Placement Law and among the states enacting it was our State

of Alabama. It provides among other things that “ each local board o f

education shall have full and final authority and responsibility for the

assignment, transfer, and continuance of all pupils among and within

the public schools within its jurisdiction— .”

The constitutionality of the Pupil Placement Act of 1955, as the

Alabama statute is known, was upheld in Shuttlesworth V. Birmingham

Board of Education, 358 U. S. 101, 79 S. Ct. 221, 3 L. Ed. 2d 145, “upon

the limited grounds on which the District Court rested its decision,”

which was that the law was not unconstitutional on its face.

We must, therefore, deal with this case in the light of the Alabama

Pupil Placement Law and Shuttlesworth V. Birmingham Board of Edu

cation supra. The most similar cases the author of this brief has been

able to find are the Carson cases which will be discussed at length fol

lowing:

Lionel C. Carson, an infant, by his next friend, Martin A. Carson, et

4

als, filed an action in the United States District Court for the Western

District of North Carolina, at Asheville, against the Board of Education

of McDowell County, a body corporate “ to require provisions for them

of educational facilities equal to those provided for white children and

to obtain injunctive relief against discrimination and judgment declar

ing children’s rights.” The United States District Court for the Western

District of North Carolina, at Asheville, dismissed the action on ground

the United States Supreme Court decision had made inappropriate the

relief prayed for in the complaint, and the children appealed to the

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.

The decision in Carson V. Board of Education of McDowell County,

227 F. 2d 789, recites that, “ The complaint alleged that the plaintiffs

were not allowed to attend schools maintained by defendants for white

children in the town of Old Fort in McDowell County but were required

to go to a school in Marion fifteen miles away and that this discrimi

nation was made soieiy on account of race and color." The complaint

was filed prior to the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Brown

V. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873. The

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit, held that the decision

of the Supreme Court just mentioned had made inappropriate the relief

asked as to separate but equal facilities but held otherwise as to the

relief asked for “ a declaratory judgment establishing the rights of

plaintiffs in the premises.” As to this aspect of the complaint the Court

said:

“Discrimination on account of race or color was alleged

with respect to the right to attend schools in Old Fort and the

removal of this discrimination as well as the declaration of the

rights of plaintiffs was asked. The decision of the Supreme

Court did not destroy or restrict these rights, except with re-

soect to the right to separate schools, and plaintiffs were en

titled to have their prayers for declaratory judgment as well as

for general injunctive relief considered in the light of the

Supreme Court decision. The decision appealed from must be

vacated, therefore, and the case remanded to the District Court

in order that this may be done.

The Court in addition took note of the fact that the State of North Caro

lina had passed an Act of March 30, 1955, entitled, “an Act to Provide

for the Enrollment of Pupils in Public Schools,” Chapter 366 of the

Public Laws of North Carolina of the Session of 1955, providing an ad

ministrative remedy for persons who feel aggrieved with respect to their

enrollment in the public schools of the state, and directed the District

Court that consideration should be given to this statute in subsequent

proceedings before it; particularly so with respect to the well settled

rule of law, “ that the Courts of the United States will not grant injunc

tive relief until administrative remedies have been exhaustd.” The Court

concluded:

“The order appealed from will accordingly be vacated and

the case remanded to the District Court with direction to con

sider it in the light of the decisioh Of the Supreme Court in the

school segregation cases and of the North Carolina statute

above mentioned and with power to stay proceedings therein

pending the exhaustion of administrative remedies under the

statute and to order a repleader if this may seem desirable”

5

After this decision, the Supreme Court of North Carolina in an

action to which two of the same plaintiffs were parties, rendered a de

cision on May 23, 1956, construing the North Carolina Act of March 30,

1955, Joyner V. McDowell County Board of Education, 244 N. C. 164,

92 S. E. 2d 795, 798, in which they held that application and appeal

under the administrative procedure in North Carolina “must be prose

cuted in behalf of the child or guardian by the interested parent,

guardian or person standing in loco parentis to such child or children

respectively and not collectively,” and that an attempt to require “ the

immediate integration of all negro, pupils” in the particular school was

a procedure “ neither contemplated nor authorized by statute.”

The cause remanded to the United States District Court proceeded

as follows: '

The plaintiffs , “ did not attempt, to comply with the provisions of

the statute as so interpreted by the Supreme Court of North Carolina,

but on July 11, 1956, counsel who was representing them before this

Court wrote a letter to the secretary of the Board- of Education, inquir

ing what steps were being taken for the admission of negro children to

the Old Fort School. The secretary replied that “ inasmuch as no negro

pupil had made application, nor has any parent or person standing in

loco parentis made application for any negro child to attend school in

the; town of Old Fort for the school year 1956-57, the Board had had no

cause to take any action in this connection.”

After receiving that reply the plaintiffs on the 12th day of July,

1956 moved in the action pending in the United States District Court

“ to file a supplemental complaint in which, without alleging compliance

with the requirements of the North Carolina statute as interpreted by

the Supreme Court, they asked a declaratory judgment and injunctive

relief with respect to their right to attend the Old Fort school. The

District Judge denied the motion on the ground that plaintiffs had not

exhausted their administrative remedies and stayed proceedings in the

cause until same should be exhausted, but stated that as soon as it was

made to appear that they had been exhausted, he would grant such relief

as might be appropriate in the premises.”

Upon the denial of the motion, application for writ of mandamus

was filed in the United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit, to re

quire the District Judge to vacate the order staying proceedings, to

allow the supplemntal pleading to be filed and to proceed with the cause

“as though the Pupil Enrollment Act had never been enacted.”

In denying the writ of mandamus the United States Court of Ap

peals, Fourth Circuit, in Carson V. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, again held

that it nowhere appeared that the plaintiffs had “ exhausted their ad

ministrative remedies under the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act,”

and were “ not entitled to the relief which they seek in the court below

until these administrative remedies have been exhausted.” The Court

said that, “while the presentation of the children at the Old Fort school

appears to have been sufficient as the first step in the administrative

procedure provided by statute, the prosecution of a joint or class pro

6

ceeding before the school board was not sufficient under the North

Carolina statute as the Supreme Court of North Carolina pointed out in

its opinion,—

The Court held that the Pupil Enrollment Act of North Carolina was

not unconstitutional.

Next the Court discussed what it meant by exhaustion of the ad

ministrative remedy:

“ It is argued that the statute does not provide an adequate adminis

trative remedy because it is said that it provides for appeals to the

Superior and Supreme Courts of the State and that these will consume

so much time that the proceeding for admission to a school term will

become moot before they can be completed. It is clear, however, that

the appeals to the courts which the statute provides are judicial, not

administrative remedies and that, after administrative remedies before

the school boards have been exhausted, judicial remedies for denial of

constitutional rights may be pursued at once in the federal courts with

out pursuing state court remedies. Lane V. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 274,

59 S. Ct. 872, 83 L. Ed. 1281. Furthermore, if administrative remedies

before a school board have been exhausted, relief may be sought in the

federal courts on the basis laid therefor by application to the board,

notwithstanding time that may have elapsed while such application was

pending.”

The Court continued: “ There is no question as to the right of these

school children to be admitted to the schools of North Carolina without

discrimination on the grounds of race. They are admitted, however, as

individuals, not as a class or group; and it is as individuals that their

rights under the constitution are asserted. Henderson V. United States,

339 U. S. 816, 824, 70 S. Ct. 843, 94 L. Ed. 1302.

Near its conclusion the Court deplored dilatory tatics by state offici

als to deprive citizens of their constitutional rights but did not attempt

to predict its holding in such a case. They said:

“The federal courts should not condone dilatory tactics or

evasion on the part of state officials in according to citizens of

the United States their rights under the Constitution, whether

with respect to school attendance or any other matter; but it is

for the state to prescribe the administrative procedure to be

followed so long as it does not violate constitutional require

ments, and we see no such violation in the procedure here re

quired.”

The Supreme Court of the United States apparently approved the

holding in the case denying certiorari, No. 748, 353 U. S. 910, 1 L. Ed

2d 664, 77 S. Ct. 665, March 25, 1957.

In summary these series of cases give us the proposition that where

a complaint is filed alleging that a student is denied admission to school

because of race or color, his complaint is not to be dismissed because

he had failed to exhaust his administrative remedy but is to be held in

abeyance until he does. If the District Judge dismissed the complaint

because he . was of the opinion appellant had failed to exhaust his ad

7

ministrative remedy, he erred. He should have held the complaint in

abeyance as ordered by the Circuit Court on the first appeal in the

Carson case.

A further answer to the question of whether appellant exhausted

his administrative remedy is that it would have been futile. He tried

for five months, lost five months of schooling. Finally when he was ad

mitted it was not done by any formal order or decision of the School

Board, rather by letting the School Trustees make an agreement with

the appellant’s father that he be admitted. Then when some of the com

munity made a disturbance at the school, appellant was expelled. The

language of the court in Griffith V. Board of Education of Yancey

County, 186 F. Supp. 511 (1960) is as pertinent here as in that case:

“ In addition, the record in this case is replete with evidence

that, had plaintiffs not exhausted their administrative remedies,

that to have done so would have been a futile and vain thing,—

the evidence indicated may dilatory tactics and evasions on the

part of the defendant which obviously denied plaintiffs citizens

of the United States, their rights under the Constitution.”

And this Honorable Court quoted Chief Judge Parker of the Fourth

Circuit in School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. V. Allen, 4 Cir.

1956, 240 F. 2d 59, 63, 64, and held in Gibson V. Board of Public Instruc

tion of Dade County, Florida, 246 F. 2d. 913:

“—and equity does not require the doing of a vain thing

as a condition of relief.”

While the Gibson cases are different from the Carson cases, they

are not contrary, they do not overrule them, they merely supplement

them. In the Carson cases the plaintiffs petitioned for admission to a

particular school, the Old Fort School, while in the Gibson cases the

plaintiffs had allegedly unsuccessfully petitioned the Board of Public

Instructions of Dade County, Florida, for abolition of racial segregation

in public schools of the county pursuant to the so called implementing

decisions. The Gibson case was subsequently filed in the United States

Court for declaritory and injunctive relief. The District Court dismissed

the complaint on motion of the defendant but holding that the complaint

did not set forth a justicable controversy and did not allege the plaintiffs

had been denied the right to attend any particular school. This Honor

able Court in Gibson V. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, supra, held that the issue of justiciable controversy under such

a complaint had been settled in Bush V. Orleans Parish School Board,

138 F. Supp. 337, 34, affirmed in 5 Cir. 1957, 242 F 2d 156, and that so

long as a stated policy of operating the schools on a nonintegrated basis

“ remained” it would be premature to consider the effect of the Florida

law as to the assignment of pupils to particular schools.

After reversal and remandment of the above case the District Court

heard the case and entered a decree declaring the segragation provisions

of the Florida Constitution and statutes unconstitutional, that the Florida

Pupil Placement Law was in effect a system of desegregation, and de

nying plaintiffs further relief, In effect, leaving the plaintiffs to their

administrative relief. Plaintiffs again appealed and in Gibson V. Board

8

of Public Instruction of Dade County, Florida, 272 F. 2d. 763, this Hon

orable Court held, as on the first appeal, that it was premature to con

sider the effect of the Pupil Placement Law so long as there were only

segregated schools in the county and that “ the district court should

proceed in accordance with this opinion and with the two opinions of

the Supreme Court in Brown V. Board of Education, supra, and should

retain jurisdiction during the period of transition.

If there is a difference in the Gibson cases and this case, it is only

in the extent of the relief asked. They sought desegregation. Appellant

seeks ony his own admission to a school without discrimination against

him on account of his race and color, a school attended by his own

relatives.

It would, indeed, be a strange system of law if the Federal Courts

were open to a group of colored persons petitioning to integregate an

entire school system in which they were being discriminated against on

account of race and color, but were closed to one little mixed blood

child who had been denied admission to the neighborhood school at

tended by his relatives, likewise on account of his race and color.

The weak and innocent ought to be protected by our laws as well

as groups with strength. Certainly the child appellant has a cause of

action in the Federal Courts.

Another case involving the same rules of law as applied in this one

is that of McCoy V. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283 F 2d. 667.

In it an action was brought by four negro children against the Greens

boro City Board of Education to secure the right of the children to

attend a public school of the city on equality with white children. The

defendants filed an answer and the cause was submitted on their

answer and upon certain affidavits and exhibits which disclosed the

action of the school Board complained of. The facts were that after the

appellants had twice been denied admission on administrative applica

tion to a white school and after this suit was filed the Board combined

by resolution the white and colored schools but subsequently granted

applications for reassignment of all of the white students and white

teachers sb that the schools ended up as segregated as before. The Dis

trict Judge’s dismissal of the complaint was based on the ground that

the appellants had not after the above action of the School Board peti

tioned again by administrative action for a re-assignment. The Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals in reversing this case said that while this suit

would have become moot if during its pendency the Board had granted

the appellants request, that this had not taken place, rather the attempts

of the appellants was completely frustrated; and that such conduct could

not be approved. The case was reversed with direction for the District

Court tq retain jurisdiction of the case so that the Board could re-assign

the minor plaintiffs to an appropriate school in accordance with their

constitutional rights, and so that plaintiffs, if those rights are improper

ly directed may apply to the Court for further relief in the pending

action.

The instant case is very similar to the McCoy case and differs from

9

it only in insignificant ways. There is only one plaintiff in this

case, where there were several in that case, but that should make no

difference. Similarly the plaintiff was first denied admission to the

school to which he sought to attend, and then permitted to attend, but

subsequently having his efforts frustrated, and ending up in the same

position he had been before. The McCoy case held that in this situation

he did not have to re-apply under the administrative remedy.

It is respectfully submitted that this cause should be reversed and

the United States District Court directed to proceed forthwith to take

such steps and hold such proceedings as necessary to grant the plaintiff

relief from further discrimination against him on account of his race

and color. If in this, appellant be mistaken, then most certainly under

the authority hereinabove cited the cause should be reversed with direc

tion to the United States District Court to retain jurisdiction thereof

pending further effort by the plaintiff to exhaust his administrative

remedy.

Respectfully submitted,

As Attorney for Willie M. Reed,

by his father and next friend, W il-

mer Reed.

Grady W. Hurst, Jr.

Attorney

P. O. Box 331

Chatom, Alabama

of Counsel for Appellant.

CERTIFICA TE OF SERVICE

I, Grady W. Hurst, Jr., of Counsel for Appellant, Willie M. Reed,

by his father and next friend, Wilmer Reed, in the cause as styled on

the front of this brief, hereby certify that I have caused a copy of the

foregoing brief to be served upon Hon. Dennis Porter, Scott and Por

ter, Attorneys, Chatom, Alabama, and upon Hon. Albert J. Tully, Attor

ney at Law, Milner Building, Mobile, A labama, of Counsel for the

Appellees, by depositing a copy of same in the United States Mail,

postage prepaid, addressed to each of them respectively at their ad

dresses shown above, on this the ............... day of February, 1962.

Grady W. Hurst, Jr.

Attorney for Appellant.

10

A P P E N D I X

Tit. 52, Section 298, Code of Alabama

298. Minimum age at which child may enter.—A child who is six

years of age on or before October first shall be entitled to admission to

the public elementary schools at the opening of such schools for that

school year or as soon as practicable thereafter; a child who is under

six years of age on October first shall not be entitled to admission to

such schools during that school year, except that a child who becomes

six years of age on or before February first may, on approval of the

board of education in authority, be admitted at the beginning of the

second semester of that school year to schools in school system having

semiannual promotions of pupils.

Tit. 52, Sections 61 (1) thru 61 (12)

61 (1). Legislative findings and recognitions.—The legislature finds

and declares that the rapidly increasing demands upon the public

economy for the continuance of education as a public function and the

efficient maintenance and public support of the public school system

require, among other things, consideration of a more flexible and selec

tive procedure for the establishment o f units, facilities and curricula

and as to the qualification and assignment of pupils.

The legislature also recognizes the necessity for a procedure for the

analysis of the qualifications, motivations, aptitudes and characteristics

of the individual pupils for the purpose of the placement, both as a

function of efficiency in the educational process and to assure the

maintenance of order and good will indispensable to the willingness of

its citizens and taxpayers to continue an educational system as a public

function, and also as a vital function of the sovereignty and police power

of the state.

61 (2). Continuing studies required; general reallocation of pupils

considered destructive.— To the ends aforesaid, the state board of edu

cation shall make continuing studies as a basis for general reconsider

ation of the efficiency of the educational system in promoting the prog

ress of pupils in accordance with their capacity and to adapt the curricu

lum to such capacity and otherwise conform the system of public edu

cation to social order and good will. Pending further studies and

recommendations by the school authorities the legislature considers that

any general or arbitrary reallocation of pupils heretofore entered in the

public school system according to any rigid rule of proximity of resi

dence or in accordance solely with request on behalf of the pupil would

be disruptive to orderly administration, tend to invite or induce dis

organization and impose an excessive burden on the available resources

and teaching and administrative personnel of the schools.

61 (3). Reallocation of pupils prohibited pending further studies

and legislation.—Pending further studies and legislation to give effect

to the policy declared by this chapter, the respective city and county

boards of education, hereinafter referred to as “ local boards of educa

tion,” are not required to make any general reallocation of pupils here

tofore entered in the public school system and shall have no authority

to make or administer any general or blanket order to that end from

any source whatever, or to give effect to any order which shall purport

to or in effect require transfer or initial or subsequent placement of any

individual or group in any unit or facility without a finding by the local

board or authority designated by it that such transfer or placement is

as to each individual pupil consistent with the test of the public and

educational policy governing the admission and placement of pupils in

the public school system prescribed by this chapter.

11

61 (4). Authority and responsibility of local boards for assignment,

transfer and continuance of pupils; factors to be considered.— Subject

to appeal in the limited respect herein provided, each local board of

education shall have full and final authority and responsibility for the

assignment, transfer and continuance of all pupils among and within

the public schools within its jurisdiction, and may prescribe rules and

regulations pertaining to those functions. Subject to review by the board

as provided herein, the board may exercise this responsibility directly

or may delegate its authority to the superintendent of education or other

person or persons employed by the board. In the assignment, transfer

or continuance of pupils among and within the schools, or within the

classroom and other facilities thereof, the following factors and the

effect or results thereof shall be considered, with respcet to the individ

ual pupil, as well as other relevant matters: Available room and teach

ing capacity in the various schools; the availability of transportation

facilities; the effect of the admission of new pupils upon established

or proposed academic programs; the suitability of established curricula

for particular pupils; the adequacy of the pupil’s academic preparation

for admission to.a particular school and curriculum;: the scholastic apti

tude and relative intelligence or mental energy or ability of the pupil;

the psychological, qualification of the pupil for the type of teaching and

associations involved; the effect of admission of the pupil upon the

academic progress of other students in a particular school or facility

thereof; the effect of admission upon prevailing academic standards at

a particular school; the psychological effect upon the pupil of attendance

at a particular school; the possibility or threat of friction or disorder

among pupils or others; the possibility of. breaches Of the peace or ill

will or economic retaliation within the community; the home environ

ment of the pupil; the maintenance or severance of established social

and psychological relationships with other pupils and with teachers; the

choice and interests of the pupils; the morals, conduct, health and pen-

sonal standards of the pupil; the request or consent of parents or

guardians and the reasons assigned therefor.

Local boards of education may require the assignment of pupils to

any or all schools within their jurisdiction on the basis of sex, but

assignments of pupils of the same sex among schools reserved for that

sex shall be made in the light of the other factors herein set forth.

61 (5). Agreement for admission of students residing in adjoining

districts; transfer of funds.—Local boards of education may, by mutual

agreement, provide for the admission to any school of pupils residing

in adjoining districts whether in the same or different counties, and

for transfer of school funds or other payments by one board to another

for or on account of such attendance.

61 (6). Assignment and transfer of teachers.— Subject to the pro

visions of law governing the tenure of teachers, local boards of educa

tion shall have authority to assign and re-assign or transfer all teachers

in schools within their jurisdiction.

61 (7). Objection to assignment of pupils; request for transfer;

action by board; hearings; investigations.—A parent or guardian of a

pupil may file in writing with the local board objections to the assign

ment of the pupil to a particular school, or may request by petition in

writing assignment or transfer to a designated school or to another

school to be designated by the board. Unless a hearing is requested, the

board shall act upon the same within 30 days, stating its conclusion. If

a hearing is requested the same shall be held beginning within 30 days

from receipt by the board of the objection or petition at a time and

place within the school district designated by the board.

The board may itself conduct such hearing or may designate not

less than three of its members to conduct the same and may provide

12

that the decision of the members designated or a majority thereof shall

be final on behalf of the board. The board of education is authorized

to designate one or more of its members or one or more competent

examiners to conduct any such hearings, and to take testimony, and to

make a report of the hearings to the entire board for its determination.

No final order shall be entered in such case until each member of the

board of education has personally considered the entire record.

In addition to hearing such evidence relevant to the individual pupil

as may be presented on behalf of the petitioner, the board shall be

authorized to conduct investigations as to any objection or request, in

cluding examination of the pupil or pupils involved, and may employ

such agents and others, professional and otherwise, as it may deem

necessary for the purpose of such investigation and examinations.

For the purpose of conducting hearings or investigations hereunder,

the board shall have the power to administer oaths and affirmations and

the power to issue subpoenas in the name of the State of Alabama to

compel the attendance of witnesses and the production of documentary

evidence. All such subpoenas shall be served by the sheriff or deputy

of the county to which the same is directed; and such sheriff or deputy

shall be entitled to the same fees for serving such subpoenas as are

allowed for the service of subpoenas from a circuit court. In the event

any person fails or refuses to obey a subpoena issued hereunder, any

circuit court of this state within the jurisdiction of which the hearing is

held or within the jurisdicton of which said person is found or resides,

upon application by the board or its representatives, shall have the

power to compel such person to appear before the board and to give

testimony or produce evidence as ordered; and any failure to obey such

an order of the court may be punished by the court issuing the same as

a contempt thereof. Witnesses at hearings conducted under this chapter

shall be entitled to the same fees as provided by law for witnesses in

the circuit courts, which fee shall be paid as a part of the costs of the

proceeding.

61 (8). Child not to be compelled to attend school in which races

commingled; objection and notice by parent; when child entitled to aid

for education.—Any other provisions of law notwithstanding, no child

shall be compelled to attend any school in which the races are com

mingled when a written objction of the parent or guardian has been filed

with the board of education. If in connection therewith a requested as

signment or transfer is refused by the board, the parent or guardian

may notify the board in writing that he is unwilling for the pupil to

remain in the school to which assigned, and the assignment and further

attendance of the pupil shall thereupon terminate; and such child shall

be entitled to such aid for education as may be authorized by law.

61 (9). When action of board final; appeals.—The findings of fact

and action of the board shall be final except that in the event that the

pupil of the parent or guardian, if any, of any minor or, if none, of the

custodian of any such minor shall, as next friend, file exception before

such board to the final action of the board as constituting a denial of

any right of such minor guaranteed under the Constitution of the United

States, or any right under the laws of Alabama, and the board shall not,

within fifteen days reconsider its final action, an appeal may be taken

from the final action of the board, on such ground alone, to the circuit

court in equity of the judicial circuit in which the school board is locat

ed, by filing with the register within thirty (30) days from the date of

the board’s final decision a petition stating the facts relevant to such

pupil as bearing on the alleged denial of his rights under the federal

Constitution, or state law, accompanied by bond with sureties approved

by the register, conditioned to pay all costs of appeal if the same shall

not be sustained. A copy of such petition and bond shall be filed with

13

the president of the board. The filing of such a petition for appeal shall

not suspend or supersede an order of the board of education; nor shall

the court have any power of jurisdiction to suspend or supersede an

order of the board issued under this chapter before the entry of a final

decree in the proceeding, except that the court may suspend such an

order upon application by the petitioner made at the time of the filing

of the petition for appeal, after a preliminary hearing, and upon a prima

facie showing by the petitioner that the board has acted unlawfully to

the manifest detriment of the child who is the subject of the proceeding.

On such appeal the circuit court may, as in other equity cases, sum

mon a jury for the determination of any issue or issues of fact presented.

Appeal to the supreme court of Alabama may be taken from the decision

of the circuit court in the same manner as appeals may be taken in other

suits in equity, either by the appellant or by such board of education.

61 (10). Attorney general to assist board; costs to be paid from

local school funds.— The board before whom any objection or proceed

ing with respect to the placement of pupils is pending may, upon au

thorization in writing of a majority of the board, request the attorney

general of Alabama to appear in such proceedings as amicus curiae to

assist the board in the performance of its judicial functions and to

represent the public interest. Expenses of court reporters, subpoenas,

witness fees and other costs of such proceedings approved by the board

shall be the obligation of the city or county involved, and shall be paid

from the public school funds of such city or county.

61 (11). Local boards constituted judicial tribunals.—Since the

determination of the matters required to be considered by boards of

education pursuant to the provisions of section 61 (4) hereof involved

determinations and inquiries of a judicial character of the most funda

mental importance in the administration of justice and the maintenance

of peace and order within the State of Alabama, all local boards of edu

cation are hereby constituted judicial tribunals, and the members there

of judicial officers within the meaning and intent of article VI of the

Constitution of Alabama. Said local boards of education are hereby in

vested with powers of a judicial nature to the extent required for the

proper performance of the responsibilities entrusted to them by this

chapter, and the exercise of said powers shall be subject to the provisions

of said article of the Constitution and clothed with the immunities of

all other judicial tribunals and officials of the state.

61 (12). Immunity of board and agents from civil or criminal lia

bility based on official findings and statements.—No board of education

or member thereof, nor its agents or examiners, shall be answerable to

any charge of libel, slander, or other action, whether civil or criminal,

by reason of any finding or statement contained in the written findings

of facts or decisions or by reason of any written or oral statements

made in the course of proceedings or deliberations provided for under

this chapter.

14