Ezold v. Wolf Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

Public Court Documents

June 17, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ezold v. Wolf Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, 1993. 2d230854-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/65562a0d-9909-45f0-bc15-77502f3ec861/ezold-v-wolf-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-third-circuit. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

J U D I T H P . V L A D E C K

S E Y M O U R M. W A L D M A N

S Y L V A N H . E L I A S

S H E L D O N E N G E L H A R D t

I R W I N B L U E S T E I N

D A N I E L E N G E L S T E I N

P a t r i c i a M c C o n n e l l

A N N E C . V L A D E C K

K A R E N H O N E Y C U T T

L A U R A S . S C H N E L L

L I N D A E . R O D D

D E B R A L. R A S K I N

J U L I A N R . B I R N B A U M

S T U A R T E . B A U C H N E R

L A R R Y C A R Y

J A M E S W A S S E R M A N

D E N N Y C H I N

VLADECK, WALDMAN, ELIAS 8 ENGELHARD, P.C.

C O U N S E L L O R S A T L A W

1 5 0 1 B r o a d w a y

N e w Y o r k , N . Y . 1 0 0 3 6

T E L 2 I 2 / 3 5 4 - 8 3 3 0

F A X 2 I 2 / 2 2 1-3 I 7 2

J E N N I F E R L. B R A U N

O W E N M. R U M E L T

I V A N D . S M I T H

H A N A N B . K O L K Q *

M I C H A E L B . R A N I S

D E N I S E M . C L A R K

J O Y C E T I C H Y

S T U A R T L. L I G H T E N

E L L E N A . H A R N I C K

J O H N A . B E R A N B A U M

f A D M t T T E D NY A N D P L

’ A D M I T T E D O H A N D Ml O N L Y

June 21, 1993

C O U N S E L

P A U L R . W A L D M A N

Charles Stephen Ralston, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

Re: Ezold v. Wolf, Block. Schorr and Solis-Cohen

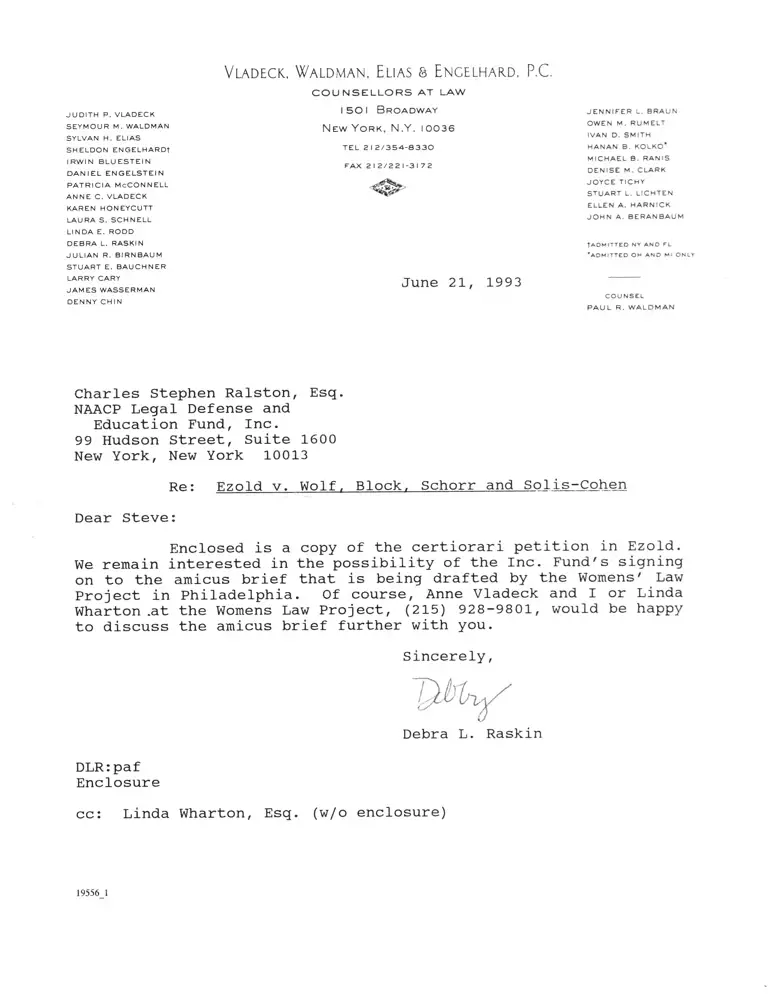

Dear Steve:

Enclosed is a copy of the certiorari petition in Ezold.

We remain interested in the possibility of the Inc. Fund's signing

on to the amicus brief that is being drafted by the Womens' Law

Project in Philadelphia. Of course, Anne Vladeck and I or Linda

Wharton .at the Womens Law Project, (215) 928-9801, would be happy

to discuss the amicus brief further with you.

Sincerely,

Debra L. Raskin

DLR:paf

Enclosure

cc: Linda Wharton, Esq. (w/o enclosure)

19556 1

No.

IN THE

Supreme (Uxmrt of ilje Jlmtt'b S tates

OCTOBER TERM, 1993

NANCY O ’MARA EZOLD,

Petitioner,

WOLF, BLOCK, SCHORR and SOLIS-COHEN,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

JUDITH P. VLADECK

Counsel o f Record

ANNE C. VLADECK

DEBRA L . RASKIN

M ICHAEL B. RANIS

VLADECK, WALDMAN,

ELIAS & ENGELHARD, P.C .

1501 Broadway, Suite 800

New York, New York 10036

(212)354-8330

Attorneys for

Nancy O’ Mara Ezold

1

1. Whether, in determining whether an em ployer’s ju s ti

fication for denial of partnership is a pretext for unlawful dis

crimination in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 (“Title VII”), trial courts are required to give special

deference to subjective performance evaluations by law firms

and other employers of professionals?

2. Whether the requirement of deference to subjective per

formance evaluations of professional employees allows an

appeals court to usurp the factfinding function of the trial

court in Title VII cases?

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.................................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................................. v

OPINIONS BELOW ...................... 1

JURISDICTION...................................................................... 2

STATUTE INVOLVED ........................................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .............. 2

A. The District Court’s F indings............................. 2

B. The Court of Appeals’ Decision ........................ 6

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITIO N ............... 8

I. INTRODUCTION.......................................................... 8

II. THE COURT OF APPEALS’ DECISION CON

FLICTS WITH PRECEDENTS OF THIS COURT

AND WITH DECISIONS OF OTHER COURTS OF

APPEALS.................................................. 10

A. This Court’s Title VII Decisions Do Not Use a

Different Analysis for the Evaluation of

Subjective C rite ria ..................................... 10

B. The Court of Appeals’ Rule Conflicts With

Other Courts of Appeals’ Requirement that The

Factfinder Review Subjective Decisionmaking

With Special Caution........ ............................. 14

Ill

C. The Decision Radically Expands The Scope Of

Appellate Court Review In Discrimination

Cases Involving Subjective Employment

D ecisions............................................................... 16

III. THE DECISION BELOW PRESENTS ISSUES OF

CRITICAL IMPORTANCE BECAUSE IT SEVERE

LY LIMITS TITLE VII PROTECTION IN HIGHER

LEVEL POSITIONS FOR WOMEN AND OTHER

PAGE

UNDERREPRESENTED G R O U PS........................... 19

CONCLUSION........................................................................ 21

APPENDIX

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit, as amended ............................................ la

Judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Third C ircuit................................ 96a

Opinions of the United States District Court, Eastern

District of Pennsylvania................................ 98a

Denial of the Petition for Rehearing In B a n c .................161a

Judgment Entered in by the United States District Court,

Eastern District of Pennsylvania................................ 163a

Excerpts from Joint Appendix Filed in the United States

Court of Appeals for the Third C ircuit.................... 164a*

Bracketed numbers (“[ ]”) on these pages refer to the page numbers in

the Joint Appendix filed in the United States Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit.

IV

Excerpts from Proposed Findings of Fact Submitted by

PAGE

Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen........................164a*

Trial Testimony......................................................................176a*

Interrogatory Responses by Wolf, Block, Schorr and

Solis-Cohen.................................................................... 179a*

Excerpts from P laintiff’s Exhibit 2 0 0 .................................181a

Excerpts from Brief of Appellant and Cross-Appellee

Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen filed in the

United States Court of Appeals for the Third

C ircu it ..............................................................203a

Order Extending Time For Filing of Petition For a Writ

of C ertio ra ri................................. .................. ......... . 207a

* Bracketed numbers (“[ ]”) on these pages refer to the page numbers

in the Joint Appendix filed in the United States Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit.

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases page

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985)....... 13, 17, 18

Bechold v. IGW Systems, Inc., 817 F.2d 1282 (7th Cir.

1987)................................................................................. 18

Bruhwiler v. University o f Tennessee, 859 F.2d 419 (6th

Cir. 1988)......................................................................... 13

Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1979)............ 15

Easley v. Empire, Inc., 757 F.2d 923 (8th Cir. 1985)....... 13

Ezold v. Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen, 983 F.2d

509 (3d Cir. 1992)......................................................passim

Ezold v. Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen, 56 Fair

Employ. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 580 (E.D. Pa. 1991) . . . . 1

Ezold v. Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen, 758

F. Supp. 303 (E.D. Pa. 1991)................. .....................1, 5

Ezold v. Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen, 751

F. Supp. 1175 (E.D. Pa. 1990)..................................passim

Frieze v. Boatmen’s Bank o f Belton, 950 F.2d 538 (8th

Cir. 1991)......................................................................... 12

Furnco Construction Corp.v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978)................................................................................ 12

Grano v. Department o f Development o f Columbus,

699 F.2d 836 (6th Cir. 1 9 8 3 )......................................... 15

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984)... 10, 19, 20

Icicle Sea Foods, Inc. v. Worthington, 475 U.S. 709

(1986)........................................................................ 7

PAGE

Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456

U.S. 844 (1982)......................................................... .

Lilly v. Harris Teeter Supermarket, 842 F.2d 1496 (4th

Cir. 1988)............................. ...........................................

Lindsey v. Prive Corp., 61 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA)

770 (5th Cir. 1993 )........................................................

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ........................................................................3, 1,

Mohammed v. Callaway, 698 F.2d 395 (10th Cir. 1983)__

O’Connor v. Peru State College, 781 F.2d 632 (8th Cir.

1986)..................................................................................

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989). 3, 8,

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228

(1989)............................................................... 10, 14, 19,

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1 9 8 2 )............

Ramseur v. Chase Manhattan Bank, 865 F.2d 460 (2d

Cir. 1989).........................................................................

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972)..................................................................................

Royal v. Missouri Highway and Transportation

Commission, 655 F.2d 159 (8th Cir. 1981)...............

Sweeney v. Board o f Trustees o f Keene State College,

569 F.2d 169 (1st Cir.), vacated on other grounds,

439 U.S. 24 (1978), a ff’d, 604 F.2d 106 (1st Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 1045 (1980)...............

Texas Department o f Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1981)...............................................................

17

15

9

12

15

11

12

20

7

16

14

15

19

11

PAGE

Tuck v. Henkel Corp., 973 F.2d 371 (4th Cir. 1992), cert,

denied, 113 S. Ct. 1276 (1993)...................... .............

Turner v. Schering-Plough Corp., 901 F.2d 335 (3d Cir.

1990).................................................................................

United States Postal Service Board o f Governors v.

Aikens, 460 U.S. 711 (1983)...................... 11, 12, 13,

United States v. City o f Black Jack, 508 F.2d 1179 (8th

Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 422 U.S. 1042 (1 9 7 5 ).......

University o f Pennsylvania v. EEOC, 493 U.S. 182

(1990)...............................................................................

Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust, 487 U.S. 977

(1988)................................................................................

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc. 395

U.S. 100 (1969)...............................................................

Statutes

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52 ........................................................ 16, 17,

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ...............................................................

28 U.S.C. § 1331 ........................................................ ...........

Age Discrimination in Employment Act § 12, 29 U.S.C.

§ 631(c)(1).......................................................................

Glass Ceiling Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, tit. II,

105 Stat. 1081, note following 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e

(West Supp. 1993)..........................................................

16

12

17

16

20

10

17

18

2

3

20

19

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e-2000e-17.................... ......... ................... passim

IN THE

Jiupremc Court of i\\z Jitutps

Oc t o b e r Te r m , 1993

No.

N a n c y O ’M a r a E z o l d ,

Petitioner,

W o l f , B l o c k , Sc h o r r and S o l is -C o h e n ,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

Nancy O’Mara Ezold (“Ezold” or “petitioner”) respectfully

petitions for a writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit in this

case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals as amended (Appendix

l a ^ a ) , 1 is reported at 983 F.2d 509 (3d Cir. 1992). The opin

ion of the District Court (Kelly, D.J.) on liability (App. 98a-

132a), is reported at 751 F. Supp. 1175 (E.D. Pa. 1990) and two

opinions of the District Court concerning damages (App. 133a-

51a and App. 152a-60a) are reported at 758 F. Supp. 303 (E.D.

Pa. 1991) and 56 Fair Employ. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 580 (E.D. Pa.

1991).

Pages in the Appendix are cited as “App.____a.’’l

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

December 30, 1992 (App. 96a-97a), and a petition for rehear

ing with suggestion of rehearing in banc was denied on Febru

ary 3, 1993. (App. 161a-62a). On April 2, 1993, Associate

Justice Souter extended the time for filing this petition to June

18, 1993. (App. 207a). The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTE INVOLVED

Section 703(2)(a) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) pro

vides:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer —

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individ

ual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or

privileges of employment, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or

applicants for employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment

opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an

employee, because of such individual’s race, color, reli

gion, sex, or national origin.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The District Court’s Findings

Petitioner Nancy O ’Mara Ezold was denied partnership at

respondent law firm Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen

(“Wolf, Block”) in 1988. Ezold commenced this action alleg

ing that Wolf, Block, in violation of Title VII, had discrimi

3

nated against her on the basis of her sex.2 Jurisdiction was

premised upon 28 U.S.C. § 1331 and 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f).

During a thirteen day trial of Ezold’s claim, the District

Court heard seventeen witnesses and reviewed thousands of

pages of exhibits. The District Court applied well-established

equal employment law analysis, Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 491 U.S. 164, 187-88 (1989); McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 804 (1973), and compared the

evaluations of Ezold with the evaluations of the male associates

who had been admitted to partnership in the year of her can

didacy and in the preceding and following years.

Members of the firm ’s governing committees testified that

there had never been “one single, solitary factor that turns a

[partnership] decision,” (App. 177a) and that partnership was

determined on the basis of all twenty factors listed on the eval

uation forms each partner completed annually for each asso

ciate. (App. 106a-107a, 176a). Ezold did not challenge the

standards articulated by Wolf, Block. Focusing on the area of

legal analysis which Wolf, Block emphasized as a reason for

rejecting Ezold (App. 125a), the District Court found nothing

in the extensive record that justified the firm ’s differential

treatment of Ezold. The District Court found the application of

that criterion to Ezold to have been biased because the firm

promoted men having “evaluations substantially the same or

inferior to the plaintiff’s, and indeed promoted male associates

who the defendant claimed had precisely the lack of analytical

or writing ability upon which Wolf, Block purportedly based its

decision concerning the plaintiff.” (App. 130a).

In the contemporaneous memorandum summarizing the part

ners’ evaluations of her in legal analysis in the year of the part

nership determination (App. 108a-109a), Ezold was graded

“good” in legal analysis, precisely the same grade that seven of

the men promoted that year and in the preceding and following

Wolf, Block was then a firm with 107 partners, only five of

whom were women. (App. 80a).

4

years received for legal analysis when they were considered for

partnership. (App. 114a, 117a, 121a, 122a, 181a-83a, 184a-86a,

187a-89a, 190a-92a, 193a-95a, 196a-97a, 198a-202a).3 The

District Court found: “In the period up to and including 1988,

Ms. Ezold received strongly positive evaluations from almost

all of the partners for whom she had done any substantial

work.” (App. 110a). After evaluating the testimony of partners

called as witnesses, the District Court concluded: “The mis

takes of the plaintiff were not of greater magnitude or type than

those of male associates who made partner.” (App. 114a).

When Ezold was denied partnership in 1988, she was told

that if she abandoned her areas of specialization, white collar

criminal defense and commercial litigation and agreed to head

the firm’s domestic relations practice, she would be promoted

the following year. The District Court found that “the addi

tional year was not for purposes of giving any additional train

ing or experience.” (App. 125a). Accordingly, the trial court

concluded that Wolf, Block “was satisfied that in 1988 [Ezold]

had all the requisites to be a member of the Firm at that time.”

{Id.)

The District Court did not rely solely on the evaluations

which reflected Ezold’s comparability to the successful male

associates. Rather, the record contained other direct evidence

of Wolf, Block’s discriminatory attitudes toward women. For

example, as the District Court found, Seymour Kurland (“Kur

land”), the chair of Wolf, Block’s litigation department, told

Ezold when she was hired as a litigation associate in 1983, that

“it would not be easy for her at Wolf, Block because she did

not fit the Wolf, Block mold since she was a woman,” among

other things. (App. 101a). Moreover, although he sometimes

delegated the duty, Kurland was “responsible for assignment of

work to associates in the Litigation Department” (App. 101a);

Wolf, B lock’s evaluation form defines the grade of “good” as

characterizing an area in which the associate “ [d isp lays particular merit

on a consistent basis; effective work product and performance; able; tal

ented .” (App. 122a).

5

when Ezold complained to a senior litigation partner of dis

crimination in assignments, she was told: “ [D]on’t say that

around here. They don’t want to hear it.” (App. 123a).

The District Court credited substantial evidence of the bias

of the evaluators, and those findings were interwoven with the

trial court’s determination that the subjective standards were

discriminatorily applied to plaintiff. The District Court’s

description of Wolf, Block’s evaluation process showed it to be

a ready receptacle for sex-bias: the process was wholly sub

jective and standardless,4 resulted in decisions based on third

or fourth hand information, and relied on evaluations infected

with sex stereotyping. (App. 122a, 124a-25a).

The District Court determined that Wolf, Block had treated

Ezold in a discriminatory manner prior to the promotion deci

sion, including the presumption against her “because she was

a woman,” and the informal assignment process yielding infe

rior work opportunities for her. (App. 102a-106a). The District

Court found that Wolf, Block was both critical of Ezold for

raising, and unreceptive to resolving, issues regarding the

firm’s treatment of its women employees. (App. 103a, 123a-

24a, 131a). Indeed, the District Court concluded that “the

adverse partnership decision . . . represented a culmination of

numerous elements of discriminatory treatment she had

received throughout her years at the Firm.” (App. 149a).

Against this background the District Court found pretextual

Wolf, Block’s partners’ explanation for the rejection as a part

ner of a woman so many of them had evaluated favorably, par

The D istrict Court found that partners were asked to evaluate

associates “on the basis of what you expect of an Associate at this Asso

c ia te’s level of experience,” (App. 107a) (emphasis in original) and

“regardless of the extent of the partner’s familiarity with the associate’s

work.” (App. 106a). W hile the Wolf, Block partners had on-going

debates regarding the firm ’s “standards” for partnership (App. 114a-15a,

117a, 119a-20a), all twenty of the factors listed on the firm ’s evaluation

forms were subjective, including such criteria as “growth potential,”

“attitude,” and “dedication.” (App. 106a-107a).

6

ticularly those who had worked most closely with her. The trial

court entered judgment for Ezold.

B. The Court of Appeals’ Decision

The Court of Appeals reversed. The appellate court found

that the principal flaw in the finding of discrimination was the

District Court’s failure to give special deference to the sub

jective judgments made by Wolf, Block in its evaluation of

Ezold. In an analysis that the Court of Appeals described as

“inform[ed]” by “cautions” against “ ‘unwarranted invasion or

intrusion’ into matters involving professional judgments about

an employee’s qualifications for promotion within a profes

sion” (App. 42a), the Court of Appeals created a new standard

that largely insulates employers of professionals who use sub

jective evaluations from traditional factfinding applicable to

other employers under the equal opportunity laws.

Were the factors Wolf considered in deciding which asso

ciates should be admitted to the partnership objective, as

opposed to subjective, the conflicts in various partners’

views about Ezold’s legal analytic ability that this record

shows might amount to no more than a conflict in the evi

dence that the district court as factfinder had fu ll power

to resolve.

(App. 47a) (emphasis supplied). So saying, the Court of

Appeals discarded, without reference, a long line of authority

recognizing the ease with which employers can manipulate

subjective standards to mask discrimination and the concomi

tant need to scrutinize the application of such standards more

closely. The Court of Appeals then created a new standard, one

far more difficult, if not impossible, for victims of discrimi

nation to meet: special deference to the decisionmakers in pro

fessional employment.

Having announced the new standard, the appellate court

launched into a 93-page de novo review of the record, reject

ing even those of the District Court’s findings which were

7

based on the firm’s admissions, and, without benefit of having

heard the witnesses, accepting testimony contrary to the trial

court’s explicit findings.5 Although the evaluation of such evi

dence is a task this Court reserves for the factfinder, Pullman-

Standard. v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 291 (1982), the Court of

Appeals relied on discredited evaluations of Ezold by partners

whose actions or comments were found by the District Court to

evince sex-bias. (Partner Kurland (App. 18a, 101a, 103a); part

ner Schwartz (App. 14a-15a, 16a-17a, 19a-20a, 123a-24a,

131a); partner Arbittier (App. 14a, 15a, 21a, 102a-103a)).6

The Court of Appeals also established a new rule requiring

that evaluations of partnership candidates be examined in a

vacuum. The appellate court held that, to be given any weight,

the non-comparative evidence had to be sufficient standing

alone to prove pretext without regard to the evaluations.

(App. 72a-74a). The Court of Appeals thus segregated from its

consideration of Ezold’s and the male associates’ evaluations,

evidence of discrimination by various partners and of Wolf,

Block’s negative reaction to Ezold’s complaints concerning

bias. See McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S. at 804 (“Other evi

dence that may be relevant to any showing of pretext includes

facts as to . . . [the employer’s] reaction . . . to [the

employee’s] legitimate civil rights activities.”)

The Court of Appeals held relevant only that evidence which

concerned “the qualification the employer [allegedly] found

lacking in determining whether non-members of the protected

For example, the Court of Appeals discounted partner M agar-

ity ’s high ratings of Ezold’s analytic ability and credited Wolf, B lock’s

description of him as an “easy grader” (App. 58a n.26), even though the

D istrict Court expressly relied upon M agarity’s admissions concerning

Ezold’s skills. (App. 103a-104a, 106a). The Court of Appeals did not find

M agarity too “easy” a marker of male candidates. (App. 58a).

6 Cf. Icicle Sea Foods, Inc. v. Worthington, 475 U.S. 709, 714

(1986) (The court of appeals “should not simply have made factual find

ings on its own,” but should have remanded to the district court for find

ings under the legal standard the appellate court articulated.)

8

class were treated more favorably” (App. 43a-44a), even

though Wolf, Block had admitted that no one factor ever was

dispositive, and the District Court had, indeed, focused its

attention on the qualification the firm had described as its pri

mary criterion, legal analysis. The Court of Appeals thus rel

egated to irrelevancy unrebutted evidence of the successful

male candidates’ failings, like disappearing for days without

warning or alienating major clients, shortcomings in areas that

Wolf, Block conceded were also important to partnership

admission and which the District Court had weighed in finding

pretext. Cf. Patterson, 491 U.S. at 187 (“to demonstrate that

respondent’s proffered reasons for its decision were not its true

reasons . . . petitioner is not limited to presenting evidence of

a certain type”).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

I. INTRODUCTION

Review of this case is vitally important to the enforcement of

the nation’s anti-discrimination laws. As the Court of Appeals

stated, its decision, the first appellate review of a trial court

finding of discrimination in law firm partnership admission,

presents “important issues that cut across the spectrum of dis

crimination law.” (App. 4a). Among those issues are the ques

tions of whether the trial court must pay special deference to

employers’ application of subjective standards in evaluating

professional employees. Also raised by the decision is the

question of whether the trial court must surgically separate par

ticular types of evidence in such cases, even though proof of

pretext is typically considered in the totality of the workplace

environment. The Court of Appeals responded to those ques

tions by requiring virtually unreviewable deference to the deci

sionmakers in such cases, and by creating new evidentiary

rules for professional employment decisions challenged as dis

criminatory.

9

The new standards articulated by the Court of Appeals per

mitted it to comb the extensive record to locate pieces of proof

purportedly supporting the law firm ’s determination, and to

reverse a judgment based upon the District Court’s one hundred

and fifty-one detailed factual findings reached after thirteen

trial days, consideration of the testimony and demeanor of sev

enteen witnesses, and a review of thousands of pages of

exhibits.

The tests devised by the Court of Appeals effectively guar

antee that the employer will prevail in any discrimination case

involving professional employees. Although the appellate court

states that direct proof of bias is not required (App. 32a), the

wide latitude given to employers to apply subjective standards,

with only deferential review by the courts (and with even that

review fitted into new evidentiary constraints), makes it almost

impossible to envision a discrimination case in which a plain

tiff employed in an upper level job could win without “smok

ing gun” proof.

It has long been recognized that it would be impossible to

enforce the equal opportunity laws if employers could avoid

liability by citing sufficiently amorphous criteria and pointing

to differences of opinion concerning the plaintiff’s performance

under those standards. Accordingly, courts have held that

because subjective criteria can be easily used to mask dis

crimination, application of such criteria is subject to more care

ful scrutiny by the fact finder. See, e.g., Lindsey v. Prive Corp.,

61 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 770, 772 (5th Cir. 1993) (“We

have recognized the potential of subjective criteria to provide

cover for unlawful discrimination.”) The Court of Appeals’

decision here turns discrimination law on its head; instead of

examining with greater scrutiny the application of subjective

criteria, the decision requires the factfinder to accord greater

deference to the employer who says it relies only on such

criteria.

10

The Court of Appeals thus has set aside long standing equal

employment law, creating a standard that collides with this

Court’s holdings in Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69

(1984) and Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989),

that those laws guarantee the right to non-biased consideration

for upper echelon jobs. The profound consequences of the

Court of Appeals’ new standard for discrimination litigation

involving upper level job opportunities warrant this Court’s

review.

II. THE COURT OF APPEALS’ DECISION CON

FLICTS WITH PRECEDENTS OF THIS COURT

AND WITH DECISIONS OF OTHER COURTS OF

APPEALS.

A. This Court’s Title VII Decisions Do Not Use a Differ

ent Analysis for the Evaluation of Subjective Criteria.

This Court has recognized the difficulty inherent in “dis-

tinguish[ing] ‘subjective’ from ‘objective’ criteria,” and how

differential standards based on that purported dichotomy can

“allowf ] employers so easily to insulate themselves from lia

bility. . . .” Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust, 487 U.S. 977,

989-90 (1988). As a consequence, the Court has “consistently

used conventional disparate treatment theory . . . to review

hiring and promotion decisions that were based on the exercise

of personal judgment or the application of inherently subjective

criteria.” Id. at 988.

Yet, the Court of Appeals created a standard of substantial

deference to an employer’s subjective decisionmaking which

contravenes this Court’s conclusion that the equal opportunity

laws accord no special treatment to employment decisions

based on non-objective reasons. Because the criteria at issue

were “subjective” as opposed to “objective” (App. 47a), the

Court of Appeals concluded that the District Court’s authority

to resolve the issues of fact presented by the evaluations of the

plaintiff was restricted by the newly announced rule of special

deference.

11

Under the reasoning of the Court of Appeals, unless all eval

uations ranked the female candidate higher than the successful

males, the District Court could conclude only that the employer

“may have been wrong in its perception” of the female candi

date’s skills (App. 57a), but would be stripped of the ability to

infer discrimination specifically accorded to the factfinder by

this Court. “ [Tjhat a court may think that the employer mis

judged the qualifications of the applicants does not in itself

expose him to Title VII liability, although this may be proba

tive o f whether the employer’s reasons are pretexts fo r dis

crimination.” Texas Department o f Community Affairs v.

Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 259 (1981) (emphasis supplied).7

Despite evidence that Wolf, Block deliberately rejected

Ezold, who had the same summary “grade” in legal analysis as

the successful men and better grades on other listed criteria and

that the firm offered her a delayed promotion to partner in the

domestic relations area without further training, the Court of

Appeals suggested that Wolf, Block’s decision about Ezold

may have been, at worst, a “mistake.” (App. 57a). On this

basis, the Court of Appeals reversed the finding of discrimi

nation, and required deference to the dissenting evaluations of

partners whose testimony the District Court had rejected as

tainted by bias.

The new requirement of deference is not the only way in

which the Court of Appeals restricted proof of discrimination

in cases involving lawyers and other professional employees.

The Court of Appeals placed inflexible and unprecedented lim

itations on the ability of lawyer plaintiffs and other profes

sionals to establish pretext. As this Court has directed, the

method of proving discrimination “was ‘never intended to be

rigid, mechanized, or ritualistic.’ ” United States Postal Service 1

1 See O’Connor v. Peru State College, 781 F.2d 632, 637 (8th Cir.

1986) (“An em ployer’s misjudgment of an employee’s qualifications and

misconceptions as to the facts surrounding her job performance may be

probative of whether the reasons articulated for an employment decision

are merely pretexts for discrim ination.”)

12

Board o f Governors v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711, 715 (1983) (quot

ing Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978)). The Court of Appeals nevertheless required that all

evidence of bias on the part of the evaluators of such profes

sionals be considered separately from the evidence of the com

parisons between the ratings of the plaintiffs in such cases and

those of the successful male or non-minority candidates.

(App. 72a-74a).

Effectively creating a new rule for district courts examining

allegations of pretext, the Court of Appeals strictly limited con

sideration of evidence showing the environment in which the

challenged decision was made. The trial court had found direct

evidence of biased comments and practices; the Court of

Appeals rejected such proof. (App. 74a-80a, 82a-93a). Instead,

the appellate court, in contravention of this Court’s repeated

emphasis that the factfinder must have wide latitude in deter

mining pretext, see Patterson, 491 U.S. at 187-88; McDonnell

Douglas, 411 U.S. at 804-805; Furnco Construction Corp., 438

U.S. at 577; Aikens, 460 U.S. at 714 n.3., held that the evidence

of the discriminatory context in which the challenged decision

was made must, standing alone, be sufficient to establish dis

crimination. (App. 72a-74a, 93a).

In addition, the Court of Appeals held that: “A plaintiff does

not establish pretext. . . by pointing to criticisms of members

of the non-protected class, or commendation of the plaintiff, in

categories the defendant says it did not rely upon in denying

promotion to a member of the protected class.” (App. 51a).8

8 The Court of Appeals cites no case in which such a rule has

been adopted. The authority on which the Court of Appeals relies (App.

44a, 52a) holds that general positive reviews do not establish pretext

where an employer has relied upon a “specific, substantial and undis

puted” perform ance deficiency. Turner v. Schering-Plough Corp., 901

F.2d 335, 344 (3d Cir. 1990); see, e.g., Frieze v. Boatmen’s Bank o f Bel

ton, 950 F.2d 538, 540 (8th Cir. 1991) (admittedly “unprofessional” act

of insubordination). Here, of course, the purported deficiency was not

only disputed, but E zold’s summary grade in that area was the same as

those of the males promoted.

13

The trial court, however, had before it Wolf, Block’s con

tentions that no one factor was ever dispositive in a partnership

determination and that there were twenty relevant criteria. Nev

ertheless, the appellate court held irrelevant as a matter of law

extensive findings that Ezold scored significantly higher on the

other criteria the firm claimed were important, and that the firm

had promoted males with grievous inadequacies in those areas

that it had acknowledged to be essential while Ezold had none

of those deficiencies.9

Even if Wolf, Block had not acknowledged that other qual

ifications were relevant to its decisionmaking, the Court of

Appeals’ new rule limiting the factors to be considered by dis

trict courts in cases involving professional employees, is con

trary to this Court’s repeated warnings against rigidity in

evaluating proof of discrimination. See Aikens, 460 U.S. at 715;

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564, 576-77 (1985).10

Other Courts of Appeals have affirmed trial court rulings find

ing pretext based, at least in part, on comparative qualifications

in areas other than those allegedly relied upon by the defendant

employers. Bruhwiler v. University o f Tennessee, 859 F.2d 419,

420 (6th Cir. 1988); Easley v. Empire, Inc., 757 F.2d 923, 930-

31 (8th Cir. 1985). The Court of Appeals’ contrary rule dictates

that where, for example, tardiness is alleged as the basis for not

promoting a woman professional, the district court, as a mat

9 Such evidence included Wolf, B lock’s prom otion of men the

partners said were “ ‘[n]ot real sm art,’ ” who disappeared unannounced

for days at a time or who put the firm at risk of losing a m illion dollars

in billings. (App. 116a-17a).

10 This Court in Anderson found that the district court did not err

when it inferred pretext from job candidates’ qualifications in areas in

addition to those allegedly relied upon by the employer. 470 U.S. at 576-

77. The p lain tiff in Anderson undisputedly lacked the degree that the

defendant asserted as the reason for hiring a male applicant. This Court,

however, held that the Fourth Circuit improperly had reversed the trial

court’s “determ ination] that pe titioner’s more varied educational and

employment background . . . left her better qualified to implement such

a rounded [recreational] program than” the successful male candidate. Id.

at 576.

14

ter of law, could not consider as proof of pretext evidence that

male employees who habitually picked fights with co-workers

or who had committed malpractice were promoted. This

Court’s holdings do not require blind deference to any

employer’s decisionmakers, nor do they permit such constric

tion of the trial court’s ability to find pretext in professional

employment.

Finally, the Court of Appeals applied a standard that comes

perilously close to the “clear and convincing evidence” stan

dard this Court rejected for Title VII cases in Price Waterhouse

v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 253 (1989).11 The appellate court

stated that: “In a comparison of subjective factors such as legal

ability, it must be obvious or manifest that the subjective stan

dard was unequally applied before a court can find pretext.”

(App. 60a) (emphasis supplied). Even assuming that “obvious

or manifest” proof was necessary and that this requirement was

not contrary to Hopkins, the evidence of bias here was obvious

and manifest—different treatment despite identical summary

grades, Kurland’s explicit comments, and other stark evidence

of discrimination. If Ezold’s proof is insufficient, no female or

minority professional employee could ever pierce the protec

tive wall the Court of Appeals has erected around law firms

and other employers of professionals.

B. The Court of Appeals’ Rule Conflicts With Other Courts

of Appeals’ Requirement that The Factfinder Review

Subjective Decisionmaking With Special Caution.

In contrast to the deferential standard and the limitations on

the ability to show pretext established by the Court of Appeals,

a line of authority dating back more than twenty years, see,

e.g., Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F. 2d 348, 359 (5th

Cir. 1972), and adopted by many Courts of Appeals, analyzes * VII

“Conventional rules of civil litigation generally apply in Title

VII cases . . . and one of these rules is that parties . . . need only prove

their case by a preponderance of the evidence.” 490 U.S. at 253.

15

subjective decisionmaking in a fashion consistent with Title

VII. Thus in Royal v. Missouri Highway and Transportation

Commission, 655 F.2d 159, 164 (1981) (emphasis supplied), the

Eighth Circuit held: “When the evaluation is in any degree sub

jective and when the evaluators themselves are not members of

the protected minority, the legitimacy and nondiscriminatory

basis of the articulated reason for the decision should be sub

ject to particularly close scrutiny by the trial judge."11

The cases adopting this reasoning are legion. Lilly v. Harris

Teeter Supermarket, 842 F.2d 1496, 1506 (4th Cir. 1988) (“The

evidence further revealed well-settled indicia of an employ

ment environment where race discrimination could flourish);

the employer] considered only subjective criteria. . . .);

Grano v. Department o f Development o f Columbus, 699 F.2d

836, 837 (6th Cir. 1983) (“Courts have frequently noted that

subjective evaluation processes intended to recognize merit

provide ready mechanisms for discrimination. [Citations omit

ted], Moreover, the legitimacy of the articulated reason for the

employment decision is subject to particularly close scrutiny

where the evaluation is subjective and the evaluators

themselves are not members of the protected minority.”);

Mohammed v. Callaway, 698 F.2d 395, 399 (10th Cir. 1983)

(“Evidence relevant to such a showing [of pretext] includes

• ■ • the use of subjective criteria. . . .”); Davis v. Califano,

613 F.2d 957, 965 (D.C. Cir. 1979) (“No objective criteria were

established to guide the promotion decisions of supervisors,

branch chiefs and ad hoc promotion panels, who were pre

dominantly male. . . . Appellee’s promotion procedures are 12

12 Only five of more than one hundred partners completing annual

associate evaluations were female. (App. 80a). Only one woman sat on

the ten member Associates Committee and no woman was a member of

the five man Executive Committee that had the final say on Ezold’s part

nership admission. (App. 178a-79a). Contrary to another erroneous “fact”

found by the Court of Appeals (App. 49a), the partnership as a whole did

not vote on Ezold’s candidacy; her candidacy was rejected by the Exec

utive Committee and therefore was never submitted for a vote of the full

partnership. (App. 110a).

16

highly suspect and must be closely scrutinized because of their

capacity for masking unlawful bias.”)

This case strikingly illustrates the dangers recognized by

other circuits: that employers can flexibly define subjective

standards to effect discriminatory results and that “clever men

may easily conceal their motivations.” United States v. City o f

Blackjack, 508 F.2d 1179, 1185 (8th Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

422 U.S. 1042 (1975) (quoted in Ramseur v. Chase Manhattan

Bank, 865 F.2d 460, 465 (2d Cir. 1989)). One of the many def

initions Wolf, Block’s partner/witnesses gave to “legal analy

sis” sufficient for entry level partnership was the ability to

handle on one’s own “any case that the firm gets, no matter

how complex. . . .” (App. 177a) (emphasis supplied). Because

the firm conceded that no junior partner was ever assigned

such responsibility, the District Court found that applying this

standard to Ezold for admission as a junior partner, was evi

dence of pretext. (App. 122a-23a). By articulating qualifica

tions not required by the firm, Wolf, Block acted in a manner

supporting an inference of discrimination. Tuck v. Henkel

Corp., 973 F.2d 371, 376 (4th Cir. 1992), cert, denied, 113

S.Ct. 1276 (1993).

C. The Decision Radically Expands The Scope Of Appel

late Court Review In Discrimination Cases Involving

Subjective Employment Decisions.

The Court of Appeals changed not only the rules that

factfinders are to apply in evaluating subjective employment

determinations challenged as discriminatory; the decision also

established a new standard for appellate consideration of a trial

court’s findings in such cases. While citing Fed. R. Civ. P. 52

(App. 37a-38a), the decision created an impermissible dis

tinction between findings concerning “objective” performance

measures and those concerning “subjective” measures. In dis

crimination cases, where the central issues are intent and cred

ibility, deference to the trial court’s findings of fact must be

17

dispositive.13 An employer’s use of subjective criteria does

not justify deference to the employer’s decisionmakers or per

mit a reviewing court to consider the record de novo.

The Court of Appeals here permitted itself to sift through the

record de novo as if Rule 52 did not apply, because the per

formance standards in issue were subjective. It credited certain

evaluations and rejected the credibility of others, a function

reserved for the trial court. As this Court has held: “The

reviewing court oversteps the bounds of its duty under Rule

52(a) if it undertakes to duplicate the role of the lower court

. . . . ‘[Its] function is not to decide factual issues de novo.’ ”

Anderson, 470 U.S. at 573 (quoting Zenith Radio Corp. v.

Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395 U.S. 100, 123 (1969)); see

Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S.

844, 856 (1982).

Such appellate factfinding is particularly ill-suited to the

evaluation of claims of discrimination, which are quintessen-

tially fact specific. Sidestepping the deference that must be

accorded to credibility determinations, the Court of Appeals

stated: “the district court never made a finding that the critical

evaluations were themselves incredible or a pretext for dis

crimination.” (App. 53a). The District Court’s findings and

conclusions, however, were that the firm ’s partners were not

credible. (App. 101a, 114a-15a, 122a-25a, 130a-31a).

The District Court rejected Wolf, Block’s proposed findings

concerning its partners’ testimony as to whether Ezold actually

13 This Court in Aikens recognized the centrality of factual deter

minations to employment discrim ination cases:

All courts have recognized that the question facing triers of fact

in discrimination cases is both sensitive and difficult. . . . There

will seldom be “eyewitness” testimony as to the em ployer’s m en

tal processes. But none of this means that trial courts or reviewing

courts should treat discrim ination differently from other ultimate

questions of fact.

460 U.S. at 716.

18

had committed the “analytic” errors with which she was

charged. (App. 164a-75a). Weighing the conflicting evidence,

and rejecting the law firm ’s version, is a credibility determi

nation. In instances where there were two versions of what hap

pened, the District Court adopted findings proposed by Ezold,

each of which was supported by record citations to documents,

testimony, or admissions (App. 101a, 114a, 115a-24a), and

rejected the counter-proposals made by Wolf, Block on the

same issue. As this Court has held:

Where there are two permissible views of the evidence the

factfinder’s choice between them cannot be clearly erro

neous. . . . [W]hen a trial judge’s finding is based on his

decision to credit the testimony of one of two or more wit

nesses, each of whom has told a coherent and facially

plausible story that is not contradicted by extrinsic evi

dence, that finding, if not internally inconsistent, can vir

tually never be clear error.

Anderson, 470 U.S. at 574-75.

The District Court’s findings were based on credibility; the

trial court was not obliged to label them as such. Bechold v.

IGW Systems, Inc., 817 F.2d 1282, 1285 n.2 (7th Cir. 1987)

(“Where it is clear that the district court made a credibility

determination in arriving at its findings of fact, we have treated

such findings as tantamount to credibility determinations. We

will not require a specific incantation when the basis of a find

ing is otherwise clear.”)14 Review by this Court therefore is

necessary to prevent the wholesale repeal of Rule 52 for cases

involving subjective employment decisions affecting lawyers

and other professional employees.

In fact, Wolf, Block complained to the Court of Appeals (App.

205a n.29) that the trial court adopted Ezold’s proposed findings on crit

ical issues as to which Wolf, Block also had submitted proposed findings,

and thereby admitted that the D istrict Court had rejected the credibility

of the firm ’s witnesses.

19

III. THE DECISION BELOW PRESENTS ISSUES OF

CRITICAL IMPORTANCE BECAUSE IT SEVERELY

LIMITS TITLE VII PROTECTION IN HIGHER

LEVEL POSITIONS FOR WOMEN AND OTHER

UNDERREPRESENTED GROUPS.

The new rules that the Court of Appeals announced threaten

to read out of the law the Court’s holdings in Hishon v. King &

Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984) and Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins,

490 U.S. 228 (1989), that Title VII’s guarantee of equal oppor

tunity is fully applicable to employment decisions involving

admission to professional partnership. If a finder of fact can

not infer discrimination where, as here, the employer’s admis

sions and other evidence of bias require the conclusion that

subjective tests were differentially applied, the equal employ

ment laws will be a dead letter for any jobs where performance

is not measured solely by quantitative standards. See Sweeney

v. Board o f Trustees o f Keene State College, 569 F.2d 169, 176

(1st Cir.), vacated on other grounds, 439 U.S. 24 (1978), a ff’d,

604 F. 2d 106 (1st Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 1045

(1980).

Indeed, the Panel’s decision is wholly contrary to Congress’s

public policy pronouncement in the Glass Ceiling Act of 1991,

Pub. L. No. 102-166, tit. II, 105 Stat. 1081, note following 42

U.S.C.A. § 2000e (West Supp. 1993), which was designed to

encourage the removal of artificial barriers to the advancement

of women and minorities in the professions. In enacting that

statute, Congress found that “despite a dramatically growing

presence in the workplace, women and minorities remain

underrepresented in management and decisionmaking positions

in business.” Glass Ceiling Act § 202(a)(1). Because admission

to virtually all such positions is determined by subjective cri

teria, resolution of the question presented here will be central

to employment issues Congress has recognized as critical.

When Congress wished to exempt higher level positions

from the equal opportunity statutes, it did so specifically. See

20

former Section 702 of Title VII, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat.

255 (1964) (exemption for individuals engaged in educational

activities which was repealed in 1972 by Pub. L. No. 92-261,

86 Stat. 103 (1972)) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-l); the Age Discrimination in Employment Act § 12,

29 U.S.C. § 631(c)(1) (mandatory retirement at age 65 not pro

hibited for an individual in a “bona fide executive or a high

policymaking position”).

By depriving the District Court of its factfinding powers, the

Court of Appeals, in effect, has enacted an exemption to the

equal employment laws for lawyers and other professionals.

Under the new standards of deference, it would be a rare

employer indeed who could not disguise biased motives by

claiming deficiencies in characteristics measured by subjective

standards. Such judicial activism is contrary to statute and to

this Court’s holdings in Hishon and Hopkins,15 and cannot

stand.

15 See University o f Pennsylvania v. EEOC, 493 U.S. 182, 190

(1990) (1972 amendments making Title VII applicable to universities

“expose[d] tenure determinations to the same enforcem ent procedures

applicable to other employment decisions.”)

21

CONCLUSION

Consideration of the case by this Court is warranted by the

importance of the issues raised concerning the application of

the equal opportunity statutes to lawyers and other professional

employees and by the conflict between other courts of appeals’

decisions and the decision below. For the foregoing reasons,

this Court should grant the petition and issue a writ of certio

rari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Dated: New York, New York

June 17, 1993

Respectfully submitted,

V l a d e c k , W a l d m a n , E l ia s &

E n g l e h a r d , RC.

/s/ J u d it h R V l a d e c k ____________

Judith P. Vladeck

Counsel o f Record

Anne C. Vladeck

Debra L. Raskin

Michael B. Ranis

1501 Broadway, Suite 800

New York, New York 10036

(212)354-8330

Attorneys for

Nancy O’ Mara Ezold

APPENDIX

la

Filed December 30, 1992

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

Nos. 91-1741 & 91-1780

NANCY O’MARA EZOLD,

Appellant a t No. 91-1780

v.

WOLF, BLOCK, SCHORR AND SOLIS-COHEN,

Appellant a t No. 91-1741

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

(D.C. Civil Docket No. 90-00002)

Argued: May 21, 1992

PRESENT: HUTCHINSON, COWEN and SEITZ,

Circuit Judges

(Opinion Filed: December 30, 1992)

Jud ith P. Vladeck, Esquire (Argued)

Vladeck, Waldman, Elias & Engelhard, P.C.

Suite 800

1501 Broadway

New York, NY 10036

Attorney for Nancy O’Mara Ezold

Arlin M. Adams, Esquire (Argued)

Schnader, Harrison, Segal & Lewis

2a

Suite 3600

1600 Market Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103

and

Mark S. Dichter, Esquire

Morgan, Lewis & Bockius

2000 One Logan Square

Philadelphia, PA 19103

Attorneys for Wolf, Block, Schorr and

Solis-Cohen

Linda J . Wharton, Esquire

Carol E. Tracy, Esquire

Jud ith L. Riddle, Esquire

Women’s Law Project

Suite 401

125 South Ninth Street

Philadelphia, PA 19107

and

Pamela L. Perry, Esquire

Rutgers School of Law

Fifth and Penn Streets

Camden, NJ 08102

Attorneys for Amici Curiae Women’s Law

Project; National Bar Association, Women

Lawyers Division, Philadelphia Chapter;

National Association of Black Women

Attorneys; Hispanic Bar Association of

Pennsylvania; New Jersey Women Lawyers

Association; San Francisco Women Lawyers'

Alliance; Pennsylvania National

Organization for Women; Women’s Alliance

for Job Equity; American Association of

University Women, Pennsylvania Division;

American Association of University Women;

3a

AAUW Legal Advocacy Fund; Business and

Professional Women/USA; Center for

Women Policy Studies; National Association

of Commissions for Women; National

Association of Female Executives; National

Organization for Women; National Women's

Law Center; NOW Legal Defense and

Education Fund; Women Employed;

Women’s Legal Defense Fund: Employment

Law Center; California Women's Law Center;

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc.; Northeast

Women's Law Center; and Women and

Employment, Inc.

OPINION OF THE COURT

HUTCHINSON, Circuit Judge.

Wolf, Block, Schorr and Solis-Cohen (Wolf)

appeals from a judgm ent of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of

Pennsylvania granting relief in favor of Nancy

O’Mara Ezold (Ezold) on her claim that Wolf

intentionally discriminated against her on the

basis of her sex in violation of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII), 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 2000e

to 2000e-17 (West 1981 & Supp. 1992), when it

decided not to admit her to the Arm's partnership

effective February 1, 1989. At trial Wolf contended

that it denied Ezold admission to the partnership

because her skills in the category of legal analysis

did not meet the firm's standards. The district

court disagreed and found that this articulated

reason was a pretext contrived to m ask sex

discrimination. Wolf argues on appeal that the

4a

district court improperly analyzed the evidence

before it and tha t the evidence, properly analyzed,

does not support the district court’s ultimate

finding of pretext.

This case raises important issues tha t cut across

the spectrum of discrimination law. It is also the

first in which allegations of discrimination arising

from a law firm partnership admission decision

require appellate review after tria l.1 Accordingly,

we have given it our closest attention and, after

an exhaustive examination of the record and

analysis of the applicable law, have concluded that

the district court made two related errors whose

combined effect require us to reverse the Judgment

in favor of Ezold. The district court first

impermissibly substituted its own subjective

judgm ent for that of Wolf in determining that Ezold

met the firm’s partnership standards. Then, with

its view improperly influenced by its own judgm ent

of what Wolf should have done, it failed to see

tha t the evidence could not support a finding that

Wolfs decision to deny Ezold admission to the

partnership was based upon a sexually

discriminatory motive rather than the firm's

assessm ent of her legal qualifications. Accordingly,

we hold not only tha t the district court analyzed

the evidence improperly and that its resulting

finding of pretext is clearly erroneous, bu t also

tha t the evidence, properly analyzed, is insufficient

to support tha t finding and therefore its ultimate 1

1. Price W aterhouse v. H opkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), Involved

a n acco u n tin g firm 's denial of p a rtn e rsh ip to a fem ale

a c co u n tan t. T h a t case did proceed to tria l b u t th e appella te

decisions provide gu idance only on th e p a rtie s ' b u rd en s of

proof In a m ixed m otives case. T his case w as no t tried on th a t

theory.

5a

conclusion of discrimination cannot stand. We will

therefore reverse and remand for entry of judgment

in favor of Wolf. This disposition makes it

unnecessary to address the issues raised in Wolfs

appeal concerning the remedy the district court

awarded to Ezold or those in Ezold’s cross-appeal

concerning her claim of constructive discharge.

I.

Ezold sued Wolf under Title VII alleging that

Wolf Intentionally discriminated against her

because of her sex when it decided not to admit

her to the firm’s partnership. She further alleged

that she was constructively discharged by reason

of the adverse partnership decision. The court

bifurcated the issues of liability and damages.

After a lengthy bench trial the district court

rendered its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law on November 29, 1990. See Ezold v. Wolf,

Block, Schorr and Solis- Cohen, 751 F. Supp. 1175

(E.D. Pa. 1990) (Ezold I). It entered judgm ent in

favor of Ezold on her claim for intentional

discrimination and against her on her claim for

constructive discharge.

The district court held tha t the

nondiscriminatory reason articulated by Wolf for

its rejection of Ezold’s candidacy—that her legal

analytical ability failed to meet the firm’s

partnership s tandard—was a pretext. It stated:

Ms. Ezold has established that the defendant’s

purported reasons for its conduct are pretextual.

The defendant promoted to partnership men

having evaluations substantially the same or

inferior to the plaintiffs, and indeed promoted

male associates who the defendant claimed had

6a

precisely the lack of analytical or writing ability

upon which Wolf, Block purportedly based its

decision concerning the plaintiff. . . . Such

differential treatm ent establishes that the

defendant’s reasons were a pretext for

discrimination.

Id. a t 1191-92 (Conclusion of Law (COL) 11). The

district court also held that four instances of

conduct by Wolf supported its finding of pretext:

(1) Ezold was evaluated negatively for being too

involved with women's issues in the firm; (2) a male

associate’s sexual harassm ent of female employees

a t the firm was seen as “insignificant’’ and not

mentioned to the Associates Committee prior to the

partnership decision; (3) Ezold was evaluated

negatively for being very demanding, while male

associates were evaluated negatively for lacking

assertiveness; and (4) Ezold “was the target of

several comments demonstrating [Wolf s]

differential treatm ent of her because she is a

woman.” Id. at 1192 (COL 12).

In holding tha t Ezold had failed to establish that

she was constructively discharged, the district

court stated:

A reasonable person in Ms. Ezold’s position

would not have deemed her working conditions

to be so intolerable as to feel compelled to resign.

Id. (COL 16). This holding became relevant to the

issue of damages. By way of relief, Ezold sought

backpay as well as instatem ent in the firm as a

partner, and if such instatem ent was impractical,

front pay. Wolf argued to the district court that its

holding that Ezold was not constructively

discharged limited her relief to back pay covering

7a

the period from her unlawful denial of admission

to the partnership, effective February 1, 1989, until

the date of her voluntary resignation from the firm

on June 7, 1989. On March 15, 1991, the district

court decided that its holding against Ezold on her

constructive discharge claim did not preclude her

from obtaining relief for the period following her

voluntary resignation. See Ezold v. Wolf, Block,

Schorr and Solis Cohen, 758 F. Supp. 303 (E.D. Pa.

1991) (Ezold II).

The parties then briefed the issue of whether

Ezold properly mitigated her damages as required

by section 706(g)(1) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 2000e-5(g)(l). On Ju ly 23, 1991, the district

court issued its final memorandum and order. It

ruled that Ezold had properly mitigated her

damages and that her rejection of Wolfs offer to

admit her as a partner as of February 1, 1990 if

she accepted responsibility for its domestic

relations practice did not toll Wolfs liability for

back pay. The court then awarded Ezold back pay

in the am ount of $131,784.00 for the period from

her resignation on Ju n e 7, 1989 to Januaiy 31,

1991. The parties agreed that if the court's

November 27, 1990 and March 15, 1991 orders

were affirmed on appeal, Ezold would be instated

as a partner.2 The court incorporated this

agreement into its orders. The district court also

awarded Ezold attorney's fees and costs. Wolf

timely appealed from the district court’s orders.

Ezold filed a protective cross-appeal from the

2. The d is tric t co u rt 's o rd er also s ta ted th a t if its p rio r o rders

were affirm ed on appeal, it w ould the rea fte r determ ine back

pay for th e period from F ebruary 1, 1991 to the date of Ezold's

in sta tem en t a s a p artn e r.

8a

district court’s denial of her constructive discharge

claim.

II.

Ezold was hired by Wolf as an associate on a

partnership track in Ju ly 1983. She had graduated

in the top third of her class from the Villanova

University School of Law in 1980 and then worked

a t two small law firms in Philadelphia. Before

entering law school, Ezold had accumulated

thirteen years of administrative and legislative

experience, first as an assistan t to Senator

Edmund Muskie, then as contract adm inistrator

for the Model Cities Program in Philadelphia, and

finally as Administrator of the Office of a Special

Prosecutor of the Pennsylvania Department of

Justice.

Ezold was hired at Wolf by Seymour Kurland,

then chairm an of the litigation department. The

district court found tha t Kurland told Ezold during

an interview tha t it would not be easy for her at

Wolf because “she was a woman, had not attended

an Ivy League law school, and had not been on

law review.” Ezold I, 751 F. Supp. a t 1177 (Finding

of Fact (FOF) 18). Subsequent to this meeting, but

prior to accepting Wolfs offer of employment, Ezold

had lunch with Roberta Liebenberg and Barry

Schwartz, both members of the litigation

department. She did not ask them anything about

the firm's treatm ent of women.

Ezold was assigned to the firm's litigation

department. From 1983-87, Kurland was

responsible for the assignm ent of work to

associates in the department. He often delegated

this responsibility to partner Steven Arbittier. As

Ezold acknowledged, many partners bypassed the

9a

formal assignm ent procedure and directly assigned

m atters to associates. The district court found that

Arbittier assigned Ezold to actions that were

“small" by Wolf standards. Id. a t 1178 (FOF 24).

Ezold's performance was reviewed regularly

throughout her tenure pursuan t to Wolfs

evaluation process, which operates as follows: The

Associates Committee, consisting of ten partners

representing each of the firm’s departments, first

reviews the performance of all the firm’s associates

and makes recommendations to the firm's

five-member Executive Committee as to which

associates should be admitted to the partnership.

The Executive Committee then reviews the

partnership recommendations of the Associates

Committee and makes its own recommendations

to the full partnership. The firm's voting partners

consider only those persons whom the Executive

Committee recommends for admission to the

partnership.

Senior associates within two years of partnership

consideration are evaluated annually; non-senior

associates are evaluated semi-annually. The firm's

partners are asked to subm it written evaluations

on standardized forms.3 The partner is asked the

degree of contact he has had with the associate

during the evaluation period. Partners were

instructed tha t the evaluations were to be

completed regardless of the extent of the

evaluating partner's contact or familiarity with the

associate’s work. Ten criteria of legal performance

3. T here w as little change beyond fo rm at In th e evaluation

form s u sed th ro u g h o u t Ezold’s ten u re . We will describe the

evaluation form s in effect in 1987 an d 1988, th e years Ezold

w as a sen io r a sso c ia te being evaluated for adm ission to the

p a rtn e rsh ip .

10a

are listed on the forms in the following order: legal

analysis, legal writing and drafting, research skills,

formal speech, informal speech, judgment,

creativity, negotiating and advocacy, prom ptness

and efficiency. Ten personal characteristics are

also listed: reliability, taking and managing

responsibility, flexibility, growth potential, attitude,

client relationship, client servicing and

development, ability under pressure, ability to

work independently, and dedication. As stated by

Ian Strogatz,4 Chairman of the Associates

Committee: “The normal standards for partnership

include as factors for consideration all of the ones

. . . th a t are contained [on] our evaluation forms."

Jo in t Appendix (App.) a t 1170.

Despite format changes, legal analysis was

always listed as the first criterion to be evaluated.

This criterion was defined on the evaluation forms

used in 1987 and 1988 as the “ability to analyze

legal issues; grasp problems; collect, organize and

understand complex factual issues." Id. a t 3728.

Partners provide grades as well as written

comments on these criteria. The evaluation forms

describe the grades as follows:

-DISTINGUISHED: Outstanding, exceptional;

consistently demonstrates extraordinary

adeptness and quality; star.

-GOOD: Displays particular merit on a consistent

basis; effective work product and performance;

able; talented.

4. At all re levan t tim es, S trogatz served a s ch a irm an of the

A ssociates C om m ittee.

11a

-ACCEPTABLE: Satisfactory: adequate; displays

neither particular merit nor any serious defects

or omissions; dependable.

-MARGINAL: Inconsistent work product and

performance; sometim es below the level of what

you expect from Associates who are acceptable

at this level.

-UNACCEPTABLE: Fails to meet minimum

standard of quality expected by you of an

associate a t this level; frequently below level of

what you expect.

Id. a t 3464 (emphasis in original).

The form asks the evaluating partner to describe

any particular strengths or weaknesses of an

associate. Partners are also asked to indicate their

views on the admission of each senior associate to

the partnership. The evaluation lists five possible

responses: “with enthusiasm ,” “with favor,” "with

mixed emotions,” “with negative feelings" or “no

opinion." Partners are also asked to respond “yes”

or “no” to the following question: “I would feel

comfortable turning over to this Associate to

handle on h is /h e r own a significant m atter for one

of my clients.” Id. a t 3467. Given the num ber of

reviewing partners, the evaluations often contain

a wide range of divergent views.

These evaluations are then compiled and

summarized by the Arm's administrative staff and

organized in books for review by the Associates

Committee. Ezold I, 751 F. Supp. at 1181 (FOF

52). Each member of the Associates Committee is

asked to make an initial assessm ent of the

evaluations pertaining to one of the associates or

candidates for partnership. That committee

12a

member prepares a form entitled “Committee

Member’s Associate Evaluation Summary"

summarizing his or her personal view of each

associate's evaluations. This form is colloquially

referred to as the “bottom line" memo. As found

by the district court, the bottom line memo “is

intended to be [the Associates Committee

member’s] own personal view of what he has

gleaned from the evaluations submitted a t the time

by the partners who submitted evaluation forms,

plus anything in addition that [the Associates

Committee member] has gleaned from any

interviews that he has conducted w ith respect to

those evaluations ." Id. a t 1181 (EOF 53) (emphasis

in original). The bottom line memo also contains

a “grid” reflecting the Associates Committee

member’s summary of the evaluated associate's

grades in legal and personal skills.

The bottom line memo also assesses a senior

associate's prospects for regular partnership

(Category VI) under the following ratings: “more

likely than not," “unclear," “less likely than not"

or “unlikely.” In 1987 and 1988, similar rankings

were used to determine the associate’s potential

for special partnership (Category VII). The Category

VII partnership then in existence conferred a

non-equity “partnership" sta tus upon associates

who fell below the normal standard for admission

as equity partners bu t whose work nevertheless

was making a valuable contribution to the firm.

See id. a t 1177 (FOF 15).

Each member of the Associates Committee

receives copies of the bottom line memo for all

associates before meeting formally to discuss

evaluations. The bottom line memo serves as a

starting point for the Associates Committee's

13a

discussion of each candidate. The Committee

members, using both the bottom line memo and

the administrative sum m aries of the grades and

comments, engage in a process of weighing and

comparing each associate's legal skills and

personal characteristics. The Committee also

conducts interviews of those partners who failed

to subm it written evaluations of an associate

during an evaluation period, submitted an

evaluation tha t requires clarification or asked for

an opportunity to supplem ent the written

evaluation in an interview.5 Strogatz testified that

the Committee has no formal voting procedure. Id.

at 1181 (FOF 57). It ultimately reaches its own

consensus as to each senior associate s

partnership potential and as to each associate’s

performance. It also formulates a performance

review th a t will be given to each associate and

senior associate by a member of the Committee.

The firm’s partners evaluated Ezold twice a year

as an associate and once a year as a senior

associate from October 1983 until the Associates

Committee determined that it would not

recommend her for partnership in September

1988. The district court found that "[i]n the period

up to and including 1988, Ms. Ezold received

strongly positive evaluations from almost all of the

partners for whom she had done any substantial

work.” Id. a t 1182 (FOF 60).6 In making this

finding the district court relied on the evaluations

5. The evaluation form a sk s th e reviewing p a rtn e r w heth er he

or she w ould like to “su p p lem en t a n d /o r explain [the] w ritten

evaluation in a n oral interview w ith a m em ber of the

A ssociates C om m ittee." See, e.g., App. a t 3889, 6467.

6, The d is tric t co u rt quo ted Ezold's evaluations in FOF 61-71.

14a