Eilers v. Eilers Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Eilers v. Eilers Brief for Appellant, 1966. 270850b7-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/65621a68-5445-4f28-85af-a62ff030ad17/eilers-v-eilers-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

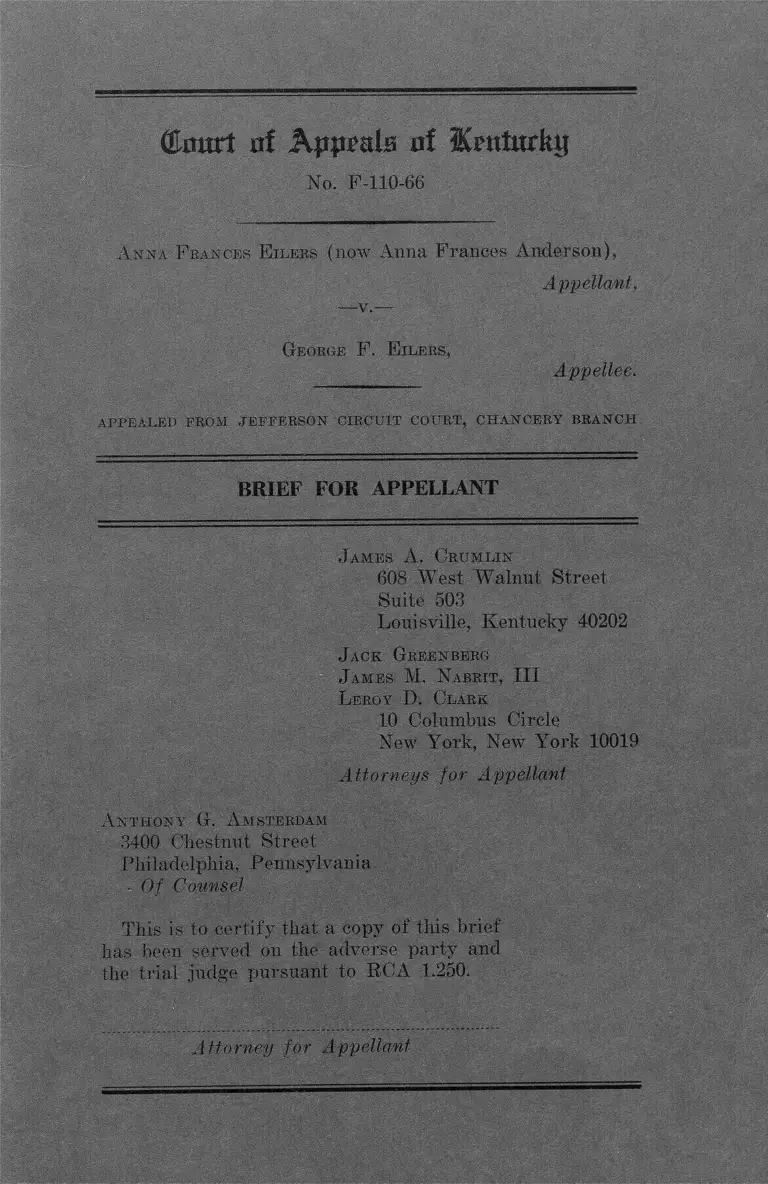

(Hmtrt f j Appeals ni Kmiutky

No. F-110-66

A nna F rances F ilers (now Anna Frances Anderson),

Appellant,

— 'v.—

George F. E ilers,

Appellee.

APPEALED FROM JEFFERSON CIRCUIT COURT, CHANCERY BRANCH

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

J ames A. Crumlin

608 West Walnut Street

Suite 503

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

A n t h o n y G . A m s t e r d a m

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Of Counsel

This is to certify that a copy of this brief

has been served on the adverse party and

the trial judge pursuant to RCA 1.250.

Attorney for Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS AND AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Questions Presented ....................................................... 1

Statement of the Case .................................................... 3

A rgument—

I. The Court Below Erred in Granting Custody of

Appellant’s Children to Their Father and in

Denying Custody to Their Mother.......................... 14

A. The Court below failed to properly apply the

principle that the mother has the paramount

right to custody of young children, where there

were no valid grounds for finding her unfit or

incapable of properly caring for the children .... 14

KRS 403.070 .................................. 14

Clark v. Clark, 298 Ky. 18, 181 S.W.2d 397 .. 14

Hatfield v. Derossett, Ky., 339 S.W.2d 631 .... 14

Callahan v. Callahan, 296 Ky. 444,177 S.W.2d

565 ............................... 14

Estes v. Estes, Ky., 299 S.W.2d 785 ............ 14.

Byers v. Byers, Ky., 370 S.W.2d 193 .......... 14

Hinton v. Hinton, Ky., 377 S.W.2d 888 ...... 14

Wilcox v. Wilcox, Ky., 287 S.W.2d 622 ...... 14

McElmore v. McElmore, Ky., 346 S.W.2d 722 14

Salyer v. Salyer, 303 Ky. 653, 198 S.W.2d

980 ............................................................. 14

Price v. Price, 214 Ky. 306, 206 S.W.2d 924 14

B. The Court below erred by applying improper

and discriminatory standards for determining

custody by the manner in which it compared the

11

mother’s and father’s homes and arbitrarily-

disregarded the mother’s willingness and ability

to provide a home of suitable size if awarded

custody ......... 15

Sowders v. Sowders, 286 Ky. 269,150 S.W.2d

903 ............................................. 16

KRS 403.070 ................... 16

Reitman v. Reitman, 168 Ky. 830, 183 S.W.

215 ................................................................. 16

Grow v. Grow, 270 Ky. 571, 110 S.W.2d 275 .. 16

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 TT.S. 60 ........ ......... 18

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ............. ........ 18

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ................ 18

C. The Court below erred in basing the custody

determination on racial considerations in viola

tion of the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States ...................... 18

KRS 403.070 ........ 20

Vincent v. Vincent, Ky., 316 S.W.2d 853 ____ 20

Heltsley v. Heltsley, Ky., 242 S.W.2d 973 .... 20

Shepherd v. Shepherd, Ky., 295 S.W.2d 557 - 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) .... 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .......20, 21

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964)

20, 21

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .............. 20

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) ............................................................ 20

"Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526

(1963)

PAGE

20

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 (1963) ....... 20

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U.S. 715 (1961) .................................... 20

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963) .. 20

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) 21

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) ..... 21

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) .... 21

In re Adoption of a Minor, 228 F.2d 446 (D.C.

Cir. 1955) ..................................................... 22

People ex rel. Portnoy v. Strasser, 303 N.Y.

539, 104 N.E.2d 895 (1952) ......................... 22

Fountaine v. Fountaine, 9 111. App.2d 482,

133 N.E.2d 532, 57 ALB 2d 675 (1956) ...... 22

D. Assuming arguendo that the Court below could

properly consider appellant’s interracial mar

riage, the Court erred in failing to grant her

relief in view of her change of residence to a

state permitting* interracial marriages .......... 22

KBS 402.020 ................... ................................. 22

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184............ 22

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 _____ 22

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 ...... 22

Workman v. Workman, 191 Ky. 124, 229 S.W.

379 .............. ......... ........................ ._____ ___ 23

Duncan v. Duncan, 293 Ky. 762, 270 S.W.2d

22 ............ .......................... ............................ 23

Beutel v. Beutel, 300 Ky. 756, 189 S.W.2d

933 ................................................ 23

Lambeth v. Lambeth, 305 Ivy. 189, 202 S.W,2d

436 ................ 23

I ll

PAGE

PAGE

E. The expressed desire of some of the children

to live with their father should not he con

trolling in view of the circumstances of the

case ....................................................................... 24

Rallihan v. Motschmann, 179 Ky. 180, 200

S.W. 358 ...................................... ................. 24

Combs v. Brewer, 310 Ky. 261, 220 S.W.2d

572 ............... 24

Stapleton v. Poynter, 111 Ky. 264, 62 S.W.

730 ........ 24

Bunch v. Hulsey, 302 Ky. 763, 196 S.W.2d

373 ................................................................. 24

Haymes v. Haymes, Ky., 269 S.W.2d 237 .... 24

Byers v. Byers, Ky., 370 S.W.2d 193 ........... 26

P. The proof showed that defendant George Eilers

is unfit to be granted custody of the children .... 26

KRS 436.200 ................ 28

G. The custody award in effect places the children

in the care of defendant’s sister, a woman who

is hostile to their mother and a relative stranger

to the children .................................................... 31

West v. West, 294 Ky. 301, 171 S.W.2d 453 .... 32

Stapleton v. Poynter, 111 Ky. 264, 23 R. 76,

62 S.W. 730 .......................................... 31

H. The Court’s finding that two professional work

ers supported the conclusion that it was in the

best interests of the children to grant custody

to the defendant is clearly erroneous and with

out evidentiary support ..................................... 32

V

II. The Court Below Violated Appellant’s Bights Un

der CE 43.10 and the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States by Refusing to Allow Her to Make

a Record of Excluded Exhibits, Identify the Ex

cluded Exhibits, or Make an Avowal With Re

spect to the Exhibits, and in Directing the Court

Reporter Not to Record Appellant’s Counsel’s

Remarks About the Exhibits ......... ........................ 35

CR 43.10 ................ ........................................... 38

Pennsylvania Lumbermen’s Mut. Fire Ins.

Co. v. Nicholas, 253 F.2d 504 (5th Cir.

1958) .......................... .................................. 39

East Ky. Rural Elec. Coop. v. Smith, Ky.,

310 S.W.2.1 535 ......................................... 39

Brinkerhoff-Faris Trust & Savings Co. v.

Hall, 281 U.S. 673 (1930) ........................... 39

Hovey v. Illinois, 167 U.S. 409 (1897) ......... 39

Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442 (1900) ........... 39

Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 596 (1961) .... 39

In re Green, 369 U.S. 689 (1962) ................ 39

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964) .... 39

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 (1938) 39

Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541 (1966) .. 39

Schwartz v. Schwartz, Ky., 382 S.W.2d 851 39

III. The Court Below Erred in Excluding Certain Evi

dence and Exhibits Which Were Pertinent to the

Defendant’s Fitness for Custody ........................... 40

A. The Court erred in excluding Mr. Eilers’ crim

inal record prior to September 29, 1964, as

contained in Anderson Avowal Exhibit No. 2 .. 40

PAGE

VI

KKS 403.070 ........ 40

Vincent v. Vincent, Ky., 316 S.W.2d 853 ....... 40

Schwartz v. Schwartz, Ky., 382 S.W.2d 851 .. 41

B. The Court erred in excluding evidence of de

fendant’s relationship with the children and

with plaintiff during* the marriage.......... ......... 42

Vincent v. Vincent, Ky., 316 S.W.2d 853 .... 42

KRS 403.070 ........................................... 42

Conclusion .......................................................................... 43

PAGE

©mart of Kppmh of Eiutturkij

No. F-110-66

A nna F eances E ilees (now Anna Frances Anderson),

Appellant,

George F. E ilees,

Appellee.

APPEALED EEOM JEPPEESON CIRCUIT COUET, CHANCERY BRANCH

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Questions Presented

1. Whether the court below erred in granting custody

of five young children to their father and denying custody

to their mother in that:

a. The Court improperly disregarded the principle that

the mother has a paramount right to custody, since there

were no valid grounds for finding her unfit or incapable

of properly caring for the children;

b. The Court applied erroneous and discriminatory

standards for custody in comparing the mother’s home

and neighborhood with the father’s home, and arbitrarily

disregarded the mother’s willingness and ability to pro

vide a home of suitable size if awarded custody;

c. The Court refused to set aside its determination that

the mother was unfit because she contracted an interracial

marriage and continues to premise its action on this hold

2

ing in violation of the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment;

d. Assuming arguendo that the Court could constitu

tionally consider the mother’s interracial marriage in de

termining the children’s interests, the Court failed to grant

appropriate relief upon the mother’s showing of changed

conditions, including her having moved to a community

with laws permitting interracial marriages, and other cir

cumstances ;

e. The Court inappropriately gave weight to the desire

of some of the children to live with their father in view of

their youth, the nature of their expressed reasons, and the

other circumstances of the case;

f. The proof showed that the father had not changed

his habits and character and that he was not fit to have

custody of the children, considering his admitted illegal

employment as a poker dealer, and one who is in the

business of accepting wagers, his irregular employment

and refusal to disclose some places of employment on the

ground of self-incrimination, and the lack of credible evi

dence that there has been a reform of his character and

habits;

g. The custody award to the father contemplates that

principal responsibility for caring for the children will be

in the hands of defendant’s sister who has had little prior

contact with the children and who is so unfriendly to their

mother that she refuses to speak to her, and is not fit by

temperament to care for the children;

h. The Court’s finding that testimony by two social

workers employed by the public agency having custody of

the children supported the ruling that the children’s best

interest were served by granting the father custody was

3

clearly erroneous, where the social workers expressly dis

claimed having made any evaluation or recommendation,

and the public agency’s usual placement investigation,

evaluation and recommendation process was not under

taken because of the Chancellor’s jurisdiction over the

children.

2. Whether the Court below violated plaintiff’s rights

under CR 43.10 and her rights to a fair hearing and to

he represented by counsel under the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States by refusing to permit plaintiff to make a

record of, or to identify, excluded exhibits, refusing to al

low plaintiff to make an avowal, and directing the court

reporter not to transcribe plaintiff’s counsel’s remarks iden

tifying the exhibits.

3. Whether the Court below erred in excluding certain

evidence and exhibits (a) concerning the defendant’s crim

inal record and (b) concerning his relationship with plain

tiff and the children prior to the parties’ divorce, where

such evidence was pertinent to an informed judgment about

the defendant’s present fitness for custody.

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from a judgment entered July 13, 1966,

by the Jefferson County Circuit Court, Chancery Branch,

Third Division (Supplemental Record, pp. 29-30),1 in which

the Hon. Lyndon Schmid, Chancellor, awarded custody of

1 The record of pleadings and orders subsequent to the former appeal

in this case and marked “ Supplemental Transcript of Record” is cited

hereinafter as “ Supp. R.” The 1966 testimony is in two volumes. The

transcript of the hearing on April 13, 1966, is cited herein as “ Tr. A ”

and the hearing on May 4, 1966, is cited as “ Tr. B.” The record on the

former appeal (this court’s file No. W-151-65) is cited as “R” .

4

five minor children (Michael, Charles Thomas, David,

Georgeanne and Francine Eilers) to their father, George

F. Eilers, defendant and appellee herein, and denied cus

tody to their mother, Mrs. Anna F. Anderson (formerly

Mrs. Anna Eilers), plaintiff' and appellant herein. Mrs.

Anderson asserts that the custody award is improper be

cause it violates the statutory command of KRS 403.070,

and because it violates her rights under the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

The matter came before the court below on supplemental

complaints filed by Mrs. Anderson and Mr. Eilers, both of

whom sought custody of the five children.2 The court

below heard evidence on April 13 and May 4, 1966, and

rendered an opinion July 5, 1966 (Supp. R. 23-28). As

stated in the opinion below, the court took judicial notice

of prior proceedings in the case including “all the evidence

in the case regarding the divorce and regarding the judg

ment of September 29, 1964” (Supp. R. 24). The prior

proceedings are contained in the record of a former ap

peal in this court, Anna Frances Eilers (Anderson) v.

George F. Eilers, File No. W-151-65, and appellant has

requested that the Clerk of this Court place the record of

the former appeal with this record pursuant to RCA 1.140.

The prior proceedings are summarized briefly below and

followed by a statement of the facts adduced at the most

recent hearings.

2 Mrs. Anderson’s Supplemental Complaint filed March 11, 1965, re

quested that she be granted custody of three o f the five children (Charles

Thomas, David and Francine) (Supp. R. 4). Mr. Eilers’ Supplemental

Complaint, filed February 17, 1966, sought custody of all of the children

(Supp. R. 12). Mrs. Anderson’s Answer and Second Supplemental Com

plaint filed April 13, 1966, prayed for an order denying Mr. Filers’

request for custody and asked for custody o f all o f her children (Supp.

R. 16-18). In her testimony, Mrs. Anderson also stated that she desired

custody of all five children (Tr. A. 35).

5

Plaintiff and defendant were married in 1950 and di

vorced on June 14, 1963 (Supp. R. 23; Tr. 4/13/66 p. 7).

Plaintiff was granted a divorce on the ground of cruel and

inhuman treatment (KRS 403.020 3(b)). As stated in the

opinion below, there was no adjudication of custody at

the time of the divorce, but plaintiff had actual custody

and “it is presumed that this arrangement was satisfac

tory to the parties at the time” (Supp. R. 23). In January

1964, plaintiff, who is white (as are defendant and the five

children), was married to Marshall Anderson, a Negro,

in Chicago, Illinois (Supp. R. 17-18). On February 13,

1964, George Eilers filed a Supplemental Complaint to

secure custody of the children. The Circuit Court heard

evidence and rendered an opinion and judgment on Sep

tember 29, 1964 (R. 13-17).3 The opinion found the father

unfit to have custody and said that there was “uncontra

dicted evidence” that the divorce was caused by George

Eilers’ “ failure . . . to properly care for his family,” and

his “excessive drinking, cruelty, gambling and association

with women other than his wife” (R. 14). It noted that

Eilers “objects to his children being, reared in the home

of a colored man” but said that the court declined to rule

on the validity of Mrs. Anderson’s marriage to her present

husband (R. 14). However, the court ruled that it would

not be in the best interest of the children to remain with

Mrs. Anderson, stating:

The Court is compelled to take notice of the racial

unrest prevalent at this time, and of the struggle on

the part of the colored race for equality with the white

race. Of course, we realize that this “equality” is a

relative word and we use the phrase merely to call

attention to the fact that in rearing these children in

a racially mixed atmosphere will per se indoctrinate

3 The citation “R.” refers to the record on the former appeal in this

Court, File No. W-151-65.

6

them with a psychology of inferiority. We think that

subjecting these children to such a hazard would be

in negation of their “best interests” (R. 15-16).

The court held that Mrs. Anderson was not fit to have

custody of the children because she contracted “a marriage

which she knows, or should have known, would re-act to

the detriment of these children” (R. 16). The court ordered

the children placed in two Catholic orphans homes in

Louisville (R. 16).

Subsequently, the two Catholic orphanages did not accept

the children and the Chancellor ordered that custody be

transferred to the Jefferson County Juvenile Court for

placement (R. 22). But when the Juvenile Court, on Feb

ruary 18, 1965, placed the two oldest children with their

father and the three youngest children with their mother,

the Chancellor entered an order on February 25, 1965, that

they be removed from the custody of the parents (R. 25).

Mrs. Anderson appealed to this Court. Mr. Eilers moved

to dismiss the appeal on ,the grounds that the appeal was

untimely. On January 14, 1966, this Court dismissed the

appeal without opinion (Supp. R. 8-9).

During the pendency of the former appeal on March 18,

1965, the five children were committed by the Juvenile

Court to the Louisville and Jefferson County Children’s

Home (Tr. A. 74-75). The Children’s Home placed them

in a variety of foster homes in Kentucky and Indiana and

in institutions operated by the home. The agency was

unable to place the five children together and they were

frequently moved from one foster home to another (Tr. A.

74-75, 77-78). For example, Francine Eilers, the youngest

child, was placed in one institution, three different foster

homes, and with two relatives during a period of seven

months (Tr. A. 74).

7

At the time of the hearing below, April 13, 1966, Fran-

cine Filers was 6 years old, David was 10, Charles Thomas

was 11, Michael was 12, and Georgeanne was 13 years of

age (Tr. A. 18). Lonnie C. Carpenter, Executive Director

of the Children’s Home testified that at that time Michael

and Charles Thomas were placed in a long-term residential

institution called Ridgewood, and Francine, Georgeanne

and Michael were placed in three foster homes (Tr. A. 73-

76). Mr. Carpenter testified that Michael and Charles

Thomas were “quite normal boys,” who had initially made

a good adjustment to Ridgewood but had more recently

had a “decline in their adjustment” (Tr. A. 76). He stated

that they were not typical of the boys at Ridgewood, most

of whom were in the institution because they had person

ality, behavior, health or adjustment problems (Tr. A. 78).

In June 1965, Ridgewood was racially integrated and

Negro and white children and staff members were assigned

to all cottages, including the one where Michael and Charles

lived (Tr. A. 78). Indeed, the social worker assigned to

them happened to be a Negro (Tr. A. 79).

Mr. Carpenter explained that normally his agency as

sumes full control over children placed with it by the

Juvenile Court and makes the decision whether to place

the children with a parent or to make other placements

(Tr. A. 86). However, he said that in this case, where

the Circuit Court was involved, his agency was not able

to make placements with the parents and had not arrived

at any agency decision as to where it would be best for

the children to be placed (Tr. A. 87). He stated that none

of the agency’s usual studies and information gathering

processes about the children and their parents necessary

to a judgment about their placement had been undertaken

(Tr. A. 86-89). His staff members were specifically in

structed not to form opinions in this case and to be neutral

between Mr. Eilers and Mrs. Anderson (Tr. A. 89-90).

8

Two social workers assigned to these children, Mrs.

Millet and Mrs. Golden were called as witnesses by George

Eilers. They both testified as to the favorable physical

environment of George Eilers’ house, but both declined to

express an opinion as to what placement would be best

for the children, explaining that they had not performed

the necessary studies and investigation to make such a

judgment (Tr. A. 182-185; Tr. B. 12-13, 15-21, 22-28, 29).

Indeed, Mrs. Golden had seen several of the children only

once (Tr. B. 25-26), and Mrs. Millet said that she did not

even know the appellant Mrs. Anderson and that she was

not making a recommendation (Tr. A. 185). Mrs. Golden

testified: “ . . . if I would have to make judgment between

the parents, I could not do it because I have not had enough

contact with them and I do not know enough about them

to make that decision” (Tr. B. 26).

In May 1965, Mrs. Anderson and her husband moved to

Indianapolis, Indiana (Tr. A. 28), where they live in a

two and one-half room efficiency apartment. Mrs. Ander

son earns $80 per week as a waitress at the Mandarin Inn

(Tr. A. 32). Mr. Anderson earns $85 a week working for

the Radio Corporation of America in the manufacture of

phonographs (Tr. A. 32-33, 57). Mr. Anderson works as

a musician on weekends to supplement his income (Tr. A.

33, 41-42, 46).

Before Mrs. Anderson lost custody of the children she

lived in a three-bedroom house in Louisville (Tr. A. 38).

She testified that if given custody of the children she would

get a larger home to receive them, saying:

In fact, I have a gentleman that’s looking for a house

for us right now. I looked at a big home last week

and the only reason that we haven’t gotten a big place

is because I saw no reason to rent a great big three

9

or four bedroom home until I got custody of these

children, although it would only be a matter of picking

up a telephone and calling a real estate man and even

renting a home (Tr, A. 29).

Mrs. Anderson gave similar testimony on cross-examination

expressing her willingness to get a larger home if she got

custody (Tr. A. 59).

Mrs. Anderson said that her employer and her husband’s

were aware of their interracial marriage, and that there

would be no harassment concerning their present jobs (Tr.

A. 59-60). Indiana’s prior laws prohibiting interracial mar

riages were repealed in 1965 (Supp. R. 22; Burns Anno.

Ind. Stats., §44-102 (1965 Supp.), §§10-4222, 10-4223 (1965

Supp.)). Mrs. Millet, one of the social workers assigned

to the case testified that the agency at one point wanted

to evaluate Mrs. Anderson’s situation in Indianapolis be

cause “the emotional climate for interracial marriages was

supposed to be better up there” and possibly present a

placement plan to the Court, but that she “never did get

permission to go on” with this approach (Tr. A. 189-190;

Anderson Exhibits 3 and 4).

Three of the children testified at the hearing. George-

anne Eilers, who was 13 years old at the time (Tr. A. 144),

stated that she had not visited her mother because she did

not want to do so (Tr. A. 147); that she did not like Mr.

Anderson (Tr. A. 148); and that “ there’s really not any

particular reason (Tr. A. 148); that she would rather not

see her mother because “I think if she cared about us she

wouldn’t have ever done what she did, or she would have

never left us” (Tr. A. 148-149); that she would prefer to

live with her father (Tr. A. 152); and testified over objec

tion that she did not want to live in a neighborhood where

there are Negro children (Tr. A. 153-154).

10

Michael Eilers, age 12, was permitted to testify, over

plaintiff’s objection, that he preferred to live with his

father (Tr. A. 169). Charles Thomas Eilers, age 11, also

testified that he wanted to live with his father (Tr. A.

173).

Mrs. Anderson testified that her relationship and Mr.

Anderson’s with the four younger children had been good

and was pleasant on their weekend visits, and that the

children cry when they have to leave, don’t want to leave,

and ask when they can live with her and her husband

(Tr. A. 28). Mrs. Anderson stated that Georgeanne did

not want to visit her; that she thought it better not to

force her if she doesn’t want to come; and that she loves

and wants her regardless of the child’s attitude toward her

(Tr. A. 34).

The court below found that defendant George Eilers

“works as a bartender and as a professional gambler”

(Supp. R. 26). Mr. Eilers was arrested January 21, 1965,

and charged with bookmaking; he pleaded guilty to dis

orderly conduct and paid a fine (Tr. A. 112; see also, Tr.

A. 67, Anderson Exhibit No. 1). The court below excluded

from evidence the record of Mr. Eilers’ other convictions

on the ground that they related to incidents arising prior

to the judgment of September 29,1964 (Tr. A. 67-70, Ander

son Avowal Exhibit No. 2; Tr. A. 98-101). On April 6,

1966, one week before the hearing below commenced, George

Eilers bought a federal wagering tax stamp and registered

under the applicable laws, as he had done in prior years

(Tr. A. 110-111).4 He testified that he answered “yes” on

the registration form to the question “Are you or will you

4 26 U.S.C.A. § 4401 imposes taxes on “ each person engaged in the busi

ness of accepting wagers.” Occupational tax and registration require

ments are imposed by 26 U.S.C.A. §§ 4411, 4412.

11

be engaged in the business of accepting wagers on your

own account?” (Tr. A. 122).

Mr. Eilers stated that he worked as a poker dealer (Tr.

A. 105-106; Tr. B. 49-50), but on two occasions refused to

answer where he worked as a poker dealer and invoked

his privilege against self-incrimination (Tr. A. 107; Tr.

B. 51). Mr. Eilers also denied that he took bets (Tr. A.

110), and said that he was a race horse “tout,” that he

spent a lot of money for books on race horses and: “I study

them books sometimes 8, 10, 12 hours a night, and I’m a

very good handicapper. I could probably right here this

afternoon, if you let me look at a form, I could pick any

one of you gentlemen a winner” (Tr. A. 114).

Mr. Eilers said that people pay him for picking race

horses, and that he got the gambling stamp “in case I

would ever take a bet” (Tr. B. 60-61). Mr. Eilers said

that he did not “know for sure” whether his children

knew about his betting on horses (Tr. B. 82).

Mr. Eilers’ record of other employment was irregular.

He said that in 1965 he worked at bars from February

until August, and that “After that I worked here and there,

and no one place no leng*th of time” (Tr. A. 105). At the

hearing on April 13, 1966, he stated that he had worked in

a bar called the Decanter, the previous day, but that he

just worked “that day” (Tr. A. 103-104). When the hear

ing resumed on May 4, he stated that he had worked as a

bartender for approximately a month (Tr. B. 30), or three

weeks (Tr. B. 48) and earned $100 a week (Tr. B. 73). He

said he was previously “self-employed” dealing cards and

playing poker (Tr. B. 49).

In early 1966, Mr. Eilers rented a four bedroom house

which was comfortably furnished (Tr. A. 180; Tr. B. 73),

at a monthly rental of $120. His sister, Mrs. Olivia Mace,

has lived in the house with him since February 1966 (Tr.

12

B. 85). Mrs. Mace is 52 years of age, is permanently sep

arated from her husband and planning a divorce (Tr. B.

90). She previously resided in Elmira, New York, and had

little or no contact with the Eilers children, until she

returned to Kentucky in 1965 (Tr. B. 94; Tr. B. 83). She

expressed a willingness to keep house and care for the

children (Tr. B. 88). During the Eilers’ marriage, Mrs.

Mace had a phone conversation with the now Mrs. Ander

son in which she (Mrs. Mace) “was very upset” and “it

was an emotional outburst” (Tr. B. 93); that she had

never talked with Mrs. Anderson “since the telephone

conversation” (Tr. B. 102); and that she would not say

they had a good relationship: “I don’t talk to her, I don’t

visit her, I have nothing to do with her, so that isn’t good,

is it?” (Tr. B. 102).

Mr. Eilers continues his association with Mrs. Patricia

Strut (Tr. B. 65), which began during his marriage (Tr.

A. 14, Anderson Avowal).6 He still sees her “quite fre

quently” (Tr. B. 65). Mr. Eilers who had been found by

the Circuit Court to be an “excessive” drinker testified

that he has “an occasional drink” (Tr. A. 117).

The opinion of the court below discussed Mrs. Anderson’s

small apartment, the fact that it is in a predominantly

Negro neighborhood, that the occupants share a bathroom

with other tenants, and that the boys share a bed when

they visit Mrs. Anderson (Supp. R. 25-26). The court

contrasted this with the larger home Mrs. Anderson had

in Louisville and decided that “were custody given to Mrs.

Anderson the circumstances and environment of these

children would deteriorate rather than improve” (Supp.

R. 26). The court described Mr. Eilers’ house; noted that

he works as a bartender and professional gambler; ruled

6 The Circuit Court has acknowledged that Mr. Eilers’ divorce was

caused in part because o f his “ association with women other than his wife”

(E. 14).

13

that the fact that he is a professional gambler did not

render him unfit to have custody; noted the desire of three

of the children to live with Eilers; and noted the avail

ability of Mrs. Mace to care for the children. The court

concluded that “the best interests of these children lie

with their father” and awarded defendant George Eilers

custody of the five children (Supp. E. 26-28). The court

stated that it took judicial notice of all prior evidence in

the case, including that prior to the judgment of Septem

ber 29, 1964, but it would not permit any evidence of

events before the September 1964 judgment, and would

consider only whether changed circumstances since that

date would justify a change of custody (Supp. R. 24-25).

As noted above, Mr. Eilers was granted full custody.

Mrs. Anderson was granted visitation privileges on al

ternate weekends from 10:00 a.m. Saturday morning until

7:00 p.m. Sunday (Supp. E. 29-30, 9-10). Mrs. Anderson

on August 1, 1966, filed notice of appeal (Supp. E. 30)

from the judgment entered on July 13, 1966 (Supp. E.

29-30).

A collateral proceeding involving custody of these same

children was recently before this Court sub nom. Michael

Eilers, et al. v. Lonnie C. Carpenter, Executive Director,

Louisville and Jefferson County Children’s Home, Case

No. S-41-66. In that action Mrs. Anderson sought a writ

of habeas corpus to obtain release of the children from

the Juvenile Home, and appealed a denial of the writ to

this Court. This Court dismissed the appeal in an opinion

rendered October 7, 1966, stating that because during the

pendency of that appeal the Circuit Court had removed

the children from the custody of the Juvenile Home and

awarded custody to George Eilers, the issues presented

were “academic.”

14

ARGUMENT

L

The Court Below Erred in Granting Custody of Ap

pellant’s Children to Their Father and in Denying

Custody to Their Mother.

A. The Court below failed to properly apply the principle

that the mother has the paramount right to custody of

young children, where there were no valid grounds for

finding her unfit or incapable of properly caring for the

children.

It is settled law, and, we take it, the common ground

upon which all arguments in this case rest, that the princi

pal consideration to be applied in determining child custody

disputes is “the interest and welfare of the children.” KBS

403.070. But another principle of equally general appli

cability has not been followed by the Court below. That

is the rule that the mother is entitled to the care, custody

and control of children of tender years, unless the evidence

is to the effect that she is incapable or unfit. Clark v. Clark,

298 Ky. 18, 181 S.W.2d 397; Hatfield v. Derossett, Ky., 339

S.W.2d 631; Callahan v. Callahan, 296 Ky. 444, 177 S,W.2d

565; Estes v. Estes, Ky., 299 S.W.2d 785; Byers v. Byers,

Ky., 370 S.W.2d 193; Hinton v. Hinton, Ky., 377 S.W.2d

888; Wilcox v. Wilcox, Ky., 287 S.W.2d 622; McElmore v.

McElmore, Ky., 346 S.W.2d 722. The rule has been said

to apply with special force to young children, Salyer v.

Salyer, 303 Ky. 653, 198 S.W.2d 980, and to girls. Byers

v. Byers, Ky., 370 S.W.2d 193; Wilcox v. Wilcox, Ky., 287

S.W.2d 622. The rule rests on the unquestionable premise

that maternal care is vitally important for children. Price

v. Price, 214 Ky. 306, 206 S.W.2d 924. Indeed, the mother

is prima facie entitled to custody.

15

We submit that there are no circumstances in this case

which indicate that Mrs. Anderson is unfit or incapable

of providing maternal care for the children. She cared

for them all from birth until the time they were separated

from her by court order, and is plainly still capable of

giving them loving maternal care. There is nothing in

the record reflecting against her unfavorably with respect

to morals, competence, intelligence, or honesty. Indeed, the

record reflects only a strong devotion to her children, as

evidenced by her long trips from Indiana to Kentucky for

regular visits with them, and a concern for their proper

religious training (Tr. A. 26-31). As we contend in more

detail in the arguments below, there is no lawful justifica

tion for depriving her of custody because of the apartment

she moved to after her children were taken from her, or

the race of her second husband. These children are of

the age where they need maternal care, and depriving them

of maternal care is plainly not in their best interests, and,

indeed, inflicts irremediable harm upon them in their forma

tive years.

B. The Court below erred by applying improper and discrim

inatory standards for determining custody by the manner

in which it compared the mother’s and father’s homes

and arbitrarily disregarded the mother’s willingness and

ability to provide a home of suitable size if awarded

custody.

The opinion below relies heavily upon the fact that Mrs.

Anderson lives in a small efficiency apartment that is un

suitable for a family with five children. The opinion com

pares this apartment unfavorably with Mrs. Anderson’s

previous home and with Mr. Eilers’ four bedroom house.

But Mrs. Anderson never for a moment suggested that if

she obtained custody of the children she proposed to con

tinue to live in the small efficiency apartment. On the con

16

trary, she made it plain that if granted custody she and

her husband could and would obtain a home of suitable

size and accommodations for the family (Tr. A. 29, 59).

Mr. and Mrs. Anderson maintained suitable quarters for

the children when they did have custody. After they lost

custody they moved to another city and obtained a small

apartment. They stand ready to provide a home of ap

propriate size if they regain custody. Nothing could be

simpler. It is unconscionable to take custody from Mrs.

Anderson on one ground and subsequently to attempt to

justify the denial on the ground that she moved to smaller

quarters in face of a prolonged change in the size of her

family group which was occasioned by the Court itself.

The ruling below on this ground was arbitrary and unfair.

Nor is there any justification for awarding custody to

George Eilers merely because he rented a large house on

a month-to-month basis immediately prior to his request

that the court grant him custody.

This Court has frequently rejected economic tests for

determining custody. In Sowders v. Sowders, 286 Ky. 269,

150 S.W.2d 903, 926, the Court, commenting on the statu

tory test of KRS 403.070, said “the poverty of the mother

constitutes no legal reason for declaring not to give her

custody and control of minor children.” Reitman v. Reit-

man, 168 Ky 830, 183 S.W. 215; Grow v. Grow, 270 Ky. 571,

110 S.W.2d 275. Plainly, in view of the father’s primary

obligation to provide financially for his children, the rela

tive economic positions of the father and mother should

not determine which parent is given custody. We submit

that for a court to sanction the denial of custody to a

mother on the ground that she was poorer than the father,

where the court controlled the father’s contribution to the

child’s support, would constitute an impermissible economic

17

discrimination denying equal protection of the laws in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. But that issue

need not be decided here, for there is no showing that Mr.

Filers is in a better economic position than Mr. and Mrs.

Anderson to provide for the children,

Mr. Eilers had no steady job from August 1965 until

the time of the first hearing on April 13, 1966. He relied

upon his gambling earnings to support himself. As he

stated it, he was a self-employed poker dealer and player

and a race horse “tout.” His income plainly depends upon

his vicissitudes of the cards and horses. He denied ac

cepting wagers, although he admitted registering with the

Federal Government as one in the business of accepting

wagers. He had no property, stocks or securities, bank

account, safety deposit box or large sums of cash (Tr. B.

71). He later obtained a job earning $100 a week as a

bartender, which he had maintained for at least three

weeks when the trial ended. He had a record of staying-

in similar jobs for only brief periods of time. His entire

job history is placed in focus by the following questions

and answers:

457 Then I’m asking you: where did you work be

fore you worked yesterday?

A. Well, it might be that the people that I worked

for, I mean, I worked for some private parties, I

mean, I don’t know if they would like for me to say

that I worked there, or—

The Court: Answer the question, Mr. Eilers.

Mr. Hubbs: Answer the question as best you can.

A. I don’t remember the last time I worked. (Tr.

A. 104)

In contrast, Mrs. Anderson and her husband are reg

ularly employed, Mrs. Anderson earning $80 per week,

18

and Mr. Anderson earning $85 per week and also sup

plementing his income as a musician on weekends. Based

on past performance, their prospects of steady employ

ment and financial responsibility are better than Mr. Ellers’

prospects by any standard. This is true, even without

considering the hazards inherent in Mr. Eilers’ illegal en

terprises, including the possibility of fines or imprisonment.

With respect to his record of prior convictions, see Argu

ment II, infra.

The Court below also thought it relevant to note in its

opinion that Mr. and Mrs. Anderson live in an interracial

neighborhood and that three interracial couples live in their

apartment building. The relevance of this is not apparent

in the context of the obvious necessity and plan for the

Andersons to move if they obtained custody. But plainly,

the courts may not, consistent with the Fourteenth Amend

ment, condition the enjoyment of legal rights on racial

considerations. It is a patent denial of equal protection of

the laws for a court to promote segregation by condi

tioning a mother’s right to custody on her residing in a

segregated neighborhood. The States may not require

segregation by direct or indirect means. Buchanan v.

War ley, 245 U.S. 60; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1;

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249. And, of course, there

was no evidence to support a conclusion that Mrs. Ander

son’s expressed desire to live in an integrated neighbor

hood in Indianapolis (Tr. A. 66-67) would have any de

leterious effect on the children.

C. The Court below erred in basing the custody determination

on racial considerations in violation of the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

The original decision denying Mrs. Anderson custody

of her children was explicitly premised upon racial factors,

19

in particular her marriage to a Negro. The Opinion and

Judgment of September 29, 1964, was frank and open in

its reliance upon Mrs. Anderson’s interracial marriage as

the sole ground for denying her custody. The Court stated,

with respect to her marriage:

We wish to re-iterate at this time that while we

are fully cognizant of the perplexities of the present

situation we will consider these perplexities only as

they relate to the well-being of these children and their

status in the present social community without regard

to any theoretical conceptions regarding the proper

relationships between the races entertained by some

folk (E. 14).

The Court concluded that “rearing these children in a

racially mixed atmosphere will per se indoctrinate them

with a psychology of inferiority. We think that subjecting

these children to such a hazard would be in negation of

their ‘best interest’ ” (E. 15-16).

The most recent opinion of the court below continues the

explicit references to race only by mentioning that the

Andersons live in “a predominantly Negro neighborhood”

and that “there are three inter-racial couples living in the

building” (Supp. E. 25). But, the opinion below contains

no disclaimer of continued reliance upon the theory that

plaintiff was unfit for the racial reasons stated in the

September 29, 1964, opinion. Moreover, the Court neces

sarily rejected plaintiff’s federal constitutional attack on

the prior judgment and her request that the Court enter

an order vacating and setting it aside (Supp. E. 17, 18),

by denying the relief requested and by limiting the scope

of inquiry to changes in the circumstances since that judg

ment. The premise of the September 29, 1964, judgment,

i.e., that Mrs. Anderson was unfit—a racial and unconsti

20

tutional premise, we submit—was the starting point for

the Chancellor’s consideration of the supplemental com

plaint. The chancellor apparently took the view that since

the only ground upon which Mrs. Anderson was deprived

of custody of her children was her interracial marriage—

only the dissolution of that marriage could be the change

of circumstances which would warrant returning custody

to Mrs. Anderson.

As this Court has held, KRS 403.070 permits the courts

to revise their orders as to child custody at any time. The

doctrine of res judicata is inapplicable. Vincent v. Vincent,

Ky., 316 S.W.2d 853. Questions involving child custody are

always open to modification where prior determinations

are unjust and erroneous. Heltsley v. Heltsley, Ky., 242

S.W.2d 973. See Shepherd v. Shepherd, Ky., 295 S.W.2d

557. And plainly, an error of constitutional dimension

must be still open to review, lest the procedure unjustly

discriminate against the assertion of federal rights.

Plaintiff’s substantive claim that the racial ground for

denying custody is unconstitutional is simple and well

grounded in precedent. This ruling below is in the teeth

of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and

a multitude of rulings since Broivn which have emphasized

over and over again in many contexts that agencies of the

states violate the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment when they compel racial

segregation and discrimination.6

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), and McLaughlin

v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964), control this case. Shelley

6 See, for example, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) (schools);

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) (pupil transfer plan) ;

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) (public parks); John

son v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 (1963) (courtrooms) ; Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961) (restaurants in public build

ings); Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963) (restaurants).

21

makes it plain that state equity courts may not intervene

and use their powers to require racial discrimination, and

that the Fourteenth Amendment is as much a protection

against discriminatory judicial action as it is against leg

islative or executive action. “But for the active interven

tion of the state courts, supported by the full panoply of

state power,” (Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. at 19), these

children would have been free to remain with Mr. and

Mrs. Anderson. But here the state has “made available

. . . the full coercive power of government” in support

of George Filers’ racial objection to his former wife’s

marriage to a Negro (ibid.).

Mrs. Anderson was denied custody because she married

a Negro and for that reason alone. If she had married a

white person the rule would have been otherwise. Because

this rule “applies only to a white person and a Negro who

commit the specified acts and because no couple other than

one made up of a white and a Negro is subject” to it, the

rule is “a denial of the equal protection of the laws guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment.” McLaughlin v. Flor

ida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964). This interference with the

sanctity of the home and the marriage relationship (Gris-

wold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)), penalizing a

marriage by depriving a mother of her five children, is an

even more serious punishment than the minor criminal

penalties imposed in McLaughlin, supra. The right to

marry, establish a home and bring up children is a pro

tected liberty under the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399

(1923); Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541 (1942).

In a case similar to this one in important respects, the

District of Columbia Circuit reversed a trial judge’s de

termination that a white child could not be adopted by

its natural (white) mother and her Negro husband. In re

22

Adoption of a Minor, 228 F.2d 446 (D.C. Cir. 1955). See

also, People ex rel. Portnoy v. Strasser, 303 N.Y. 539, 104

N.E.2d 895 (1952), where New York’s highest court re

versed a judgment denying custody of a white child to its

mother whose second husband was a Negro.

Similarly, an Illinois court in Fountaine v. Fountaine,

9 111. App.2d 482, 133 N.E.2d 532, 57 ALE 2d 675 (1956),

held that the race of a mother’s second husband could not

overweigh other questions and be decisive of custody.

D. Assuming arguendo that the Court below could properly

consider appellant’s interracial marriage, the Court erred

in failing to grant her relief in view of her change of

residence to a state permitting interracial marriages.

Appellant has contended throughout this proceeding that

her interracial marriage is not a constitutional ground for

denying her custody, and that giving direct or indirect

effect to Kentucky law and policy prohibiting such mar

riages (KRS 402.020) violates the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Mc

Laughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184; Griswold v. Connecticut,

381 U.S. 479; Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390. However,

even assuming for the purposes of argument that this con

tention is incorrect, the fact is that appellant’s marriage

is plainly recognized by the laws of Indiana, the state

where she is now living. There is no justification for ap

plying Kentucky’s law on interracial marriages to resi

dents of Indiana.

Indiana, in 1965, repealed its laws prohibiting marriages

between whites and Negroes; this was brought to the at

tention of the Chancellor (Supp. R. 22). There is no sound

basis for an attempt to give extraterritorial application to

Kentucky’s law or policy with respect to interracial mar

riages. Furthermore, there is no ground for the Kentucky

23

courts to make any assumption that social conditions in

Indiana would cause the interracial marriage to harm the

children. The only evidence on the question—by Mrs. An

derson (Tr. A. 59-60) and Mrs. Millett (Tr. A 189-190)—

is to the contrary. The very fact that the Indiana legis

lature in 1965 repealed its ancient laws prohibiting mar

riages between white and Negroes reflects a political and

social climate not incongenial to such unions.

If it is at all appropriate to consider the appellant’s inter

racial marriage in the context of the social environment, it

is necessary to consider that question in the context of this

changed environment in Indianapolis. Of course, this rec

ord reflects the changing environment in Kentucky as well.

Although the Eilers’ children were removed from their

mother’s home to avoid an interracial environment, two of

the children were placed in a public agency which was

racially desegregated—without any reported ill effects on

these children—during the period they were in its cus

tody (Tr. A. 78-79). We urge that changing conditions in

the society make it inappropriate for courts to attempt to

regulate custody determinations with reference to racial

associations. But whether or not that is correct, it is surely

inappropriate to attempt regulation of racial associations

across state lines. And, of course, it has long been recog

nized by this Court that it is proper to pei’mit parents to

move children to other states in efforts to improve their

family lives. Workman v. Workman, 191 Ky. 124, 229 S.W.

379; Duncan v. Duncan, 293 Ky. 762, 270 S.W.2d 22; Beutel

v. Beutel, 300 Ky. 756, 189 S.W.2d 933; Lambeth v. Lam

beth, 305 Ky. 189, 202 S.W.2d 436. No other rule would be

conceivable in view of the mobility of the American popu

lation.

24

E. The expressed desire of some of the children to live with

their father should not be controlling in view of the cir

cumstances of the case.

Three of the children expressed a desire to live with the

father George Eilers; they were Georgeanne, who was 13

years old (almost 14), Michael, age 12, and Charles Thomas

age 11. The other two children, David (age 10) and Fran-

cine (age 6), did not testify.

Plainly, David and Francine were too immature for their

desires to be credited or relied upon by the Court, and there

was no attempt to elicit their feelings. We submit that it

should be equally plain that they should not be bound by

the desires of their older brothers and sister. As we shall

argue below, the older children’s desires should be disre

garded in this case. The reasons which will be given, apply

with even greater force against the proposition that the

older children should be allowed to determine the custody

of David and Francine.

This Court has frequently disregarded the desires of

children in deciding custody matters where objective

factors such as the unfitness of a parent, or the preferred

right of a mother to custody, make it plain that the rights

of the parents are not in equipoise, or doubtful. Rallihan

v. Motschmann, 179 Ky. 180, 200 S.W. 358; Combs v.

Brewer, 310 Ky. 261, 220 S.W.2d 572; Stapleton v. Poynter,

111 Ky. 264, 62 S.W. 730; Bunch v. Hulsey, 302 Ky. 763,

196 S.W.2d 373; Haymes v. Haymes, Ky., 269 S.W.2d 237.

Eleven year old Charles Thomas Eilers expressed a

preference for living with his father “Just because I think

I would get a better education with him.” Obviously, the

child had no sufficient basis to make an informed conclu

sion. Nothing in George Eilers’ history of illegal enter

prises, arrests, unstable employment, and financial irres

ponsibility, justifies any conclusion that he will provide

25

liis children with a better education than their mother.

(Note the excluded evidence about his lack of interest in

their education during the Eilers’ marriage, which is dis

cussed in Argument III, infra). It seems probable that

Charles Thomas expressed his preference under the in

fluence of his older brother—who wrote letters to the

father’s lawyer and signed them for his younger brother

(Tr. B. 122-123)—or of his father with whom he had more

frequent contact during the period just before his testi

mony. Nothing in the youth’s testimony, or elsewhere in

the record, suggested he had any hostility to his mother;

all the evidence is to the contrary.

Michael Eilers, age 12, said that he preferred to live

with his father “because my Dad understands me most”

(Tr. A. 169). Here again, the reason is insufficient to

outweigh the objective factors pertaining to George Eilers’

unfitness, which are discussed in detail below. Again, the

circumstances make the expression of preference inherently

unreliable. The testimony of Mr. Lonnie Carpenter, head

of the Children’s Home, demonstrated that Michael and

Charles Thomas were unhappy in the Ridgewood institu

tion and that their adjustment was declining. The trial

judge had already made it clear in his September 1964

ruling that he would not grant custody to Mrs. Anderson

while she was married to a Negro. The boys clearly ex

pressed their desire to be released from the Children’s

Home (Tr. B. 122). It cannot have been lost on these

young boys that their only realistic hope of release by the

Circuit Court from the public institution was to profess a

desire to live with their father. This is plainly not the

kind of free and reasoned choice which this Court should

regard as binding. The relative immaturity of the child

and the strong possibility of undue influence require that

the child’s desire be disregarded. Michael expressed no

26

hostility to his mother and the evidence was that he was

affectionate towards her.

Georgeanne Eilers did express hostility to her mother

and stepfather, and resentment about her mother’s remar

riage (Tr. A. 147-149). But nothing about her testimony

indicates that her preference was the result of a mature

judgment. She blamed her mother for the fact that the

children were separated from one another, notwithstanding

the fact that her father instituted the legal proceedings

which resulted in the children being separated (Tr. A.

148-149). When asked why she disliked her stepfather

she said, “ . . . there’s really not any particular reason.

I just don’t like him” (Tr. A. 148). Notwithstanding these

feelings, there is no sufficient basis for believing that

Georgeanne and her mother cannot be reconciled if given

an opportunity. We submit that Mr. Eilers’ unfitness (Ar

gument I. F, infra) and the recognized need of an adoles

cent girl for maternal supervision (Byers v. Byers, Ky.,

370 S.W.2d 193) justify the disregard of her expressed

preference. There is every indication that Georgeanne’s

alienation from her mother has been aggravated, if not

caused, by the court-ordered separation from her mother.

F. The proof showed that defendant George Eilers is unfit

to be granted custody of the children.

In the opinion and judgment entered in this case on

September 29, 1964, the Chancellor found defendant George

Eilers unfit to have custody of the children, stating:

The uncontradicted evidence in the case is to the

effect that the original divorce was caused by failure

of the Defendant to properly care for his family. This

failure was occasioned by excessive drinking, cruelty,

gambling, and association with women other than his

wife (R. 14).

27

The opinion of July 5, 1966, said with respect to defen

dant’s fitness:

According to Defendant’s testimony, he has now at

tained a state of sobriety and he is regularly employed.

He works as a bartender and as a professional gambler.

While the Courts in Kentucky frown upon gambling

and the Statutes inveigh against it, we cannot in this

day and age reach a conclusion that because a parent

is a professional gambler or an amateur gambler that

they are unfit to have the custody of their own children

(Supp. R. 26).

It is submitted that the defendant entirely failed to show

that he is a fit and proper person to be granted custody

of young children. His own testimony, and other uncon

tradicted evidence, which is detailed in the Statement of

the Case, supra, pp. 10 to 11, shows that he has long

supported himself by illegal gambling enterprises. He

describes himself as a self-employed poker dealer and

player (Tr. B. 49) and a race-horse “tout” , who studies

racing forms “8, 10, 12 hours a night” and boasted from

the witness stand that he could pick a winner for anyone

in the courtroom (Tr. A. 114). He invoked the privilege

against self-incrimination to conceal the location of the

private poker club he operated (Tr. A. 106-107). He had

no regular employment aside from gambling from August

1965 to April 1966 (Tr. A. 105, Tr. B. 72). A week before

coming to court to seek custody of the five children, he

again registered as a gambler and purchased a federal

gambling tax stamp, as he had done in previous years

(Tr. A. 110, 111). He admitted giving a false address for

his gambling activities in his federal registration (Tr. B.

54-57). He refused to name his gambling associates (Tr.

B. 50-51). His testimony was evasive and equivocal to the

28

point that notwithstanding his admission that he registered

with the government as one in the business of accepting

bets, he denied doing so. Indeed, he claimed at a prior

hearing in 1964 that he had stopped being a bookmaker

(Transcript of Hearing, June 8, 1964, pp. 8, 29-30) ;7 but

registered as a gambler in 1965 and 1966 and pleaded

guilty to a gambling charge in 1965 (Tr. A. 111-112).

There was no clear evidence of reform with respect to

his drinking habits; only his assertion that he now drinks

“occasionally” (Tr. A. 117). He still keeps liquor in his

home and works occasionally in bars (Tr. A. 117, Tr. B.

77-78).

Gambling offenses of various kinds are proscribed by

Kentucky law, and are classified in the Revised Statutes

as “ Offenses Against Morality” (KRS 436.200 et seq.).

The potential deleterious effects of defendant’s unlawful

7 Transcript of June 8, 1964; George Eilers, direct examination:

40 And you have a reputation of being a booky?

A. Previous, till the time I got sick in 1961.

41 You haven’t been since then?

A. No, sir. (Transcript p. 8.)

At the same hearing on cross examination (Tr. pp. 29-30):

161 What do you do for a living sir?

A. Well I have been a bartender, I have been, back in the old days,

I had a gambling stamp, I was a gambler, and I have been a rail

roader, and I have been a whiskey salesman, I have been in a lot of

different occupations. Eight now I can’t say that I am doing anything

for a living because I am not working.

162 You say you were a booky?

A. I said I had a gambling stamp. Do you call that a booky?

163 I understood your lawyer to ask you if you were not a booky?

I f you had a reputation for being a booky ?

A. I had a gambling stamp, and I took bets on race horses.

164 You don’t call that a booky?

A. That’s what I have heard it called.

165 You don’t do that now, is that what you are telling this Court.

A. That’s right.

29

activities on the children are readily evident. One who

makes his living unlawfully is not likely to inculcate the

children with a respect for the laws of society. Nor is he,

nor are his children, likely to receive the respect of their

neighbors so essential to the children’s self-esteem and

healthy growth. I f it be so, as the Court below wrote in

its first opinion, that “It is a known fact that children

can be most brutal in their frankness” (R. 15), it is easy

to imagine the humiliations to which these young persons

will be exposed as dependents of a “tout” and common

gambler.

Equally important, the financial position of an inveterate

gambler is inherently unstable. Even while he remains at

large, his capacity to provide for his dependents rides

with the horses and the cards. He is always subject to

be arrested and confined for federal or state offenses. In

the event of his incarceration, neither parental care nor

income will be available to these children.

Moreover, the potentially dangerous character of de

fendant’s undisclosed criminal associates cannot be ig

nored. Defendant’s claim of the privilege entirely pre

cluded inquiry by the Court below into this vital question.

Doubtless, the claim of privilege was defendant’s right,

and rightly honored by the Court.8 But its effect was to

leave the Court uninformed concerning the character of

the adults with whom these children may come into con

tact in defendant’s home. Surely, common knowledge of

the ordinary close relations between gambling and a gamut

of other criminal activities, from blackmail and corrupt

pay-offs to strong-arm violence, suggests the risks to which

8 Tr. B. 50-51. However, the Court’s later ruling that the names o£

defendant’s gambling associates was not material (Tr. B. 60) was plainly

erroneous.

30

the Court’s ignorance in this aspect leaves the children

prey.

One need not, therefore, be overly pious about gambling

to perceive the disastrous effects Mr. Eilers’ occupation

may have on the children; nor to perceive that Eilers will

not only be compelled to rely on the fruits of his illegal

occupation, but to expand his gambling business to care for

the children; nor to perceive that one who boasts of spend

ing eight to twelve hours a night poring over racing forms

and books is unlikely to provide a wholesome example for

young children.

Eilers also continues his association with Mrs. Patricia

Strut, with whom he associated during his marriage. In

short, there is no evidence to establish that Eilers has

changed and suddenly become a fit person to rear five

young boys and girls. All this is in contrast to the plain

tiff, Mrs. Anderson, an affectionate and devoted mother

with habits and character traits plainly fitting her to care

for her children.

Diligent research by counsel has located no case in which

a professional gambler or other criminal has been awarded

custody of children merely because his illegal profits enable

him to provide them with a physically desirable home. We

urge that such a theory violates the express public policy

of the Commonwealth against gambling, and is no proper

ground for determining the best interests of young children.

Especially must this be so where there is an alternative

parent, the mother, who is normally preferred and against

whom no charges have been made that she has been ar

rested or convicted for any crime and who has demon

strated her fitness over many years.

31

G. The custody award in effect places the children in the

care of defendant’s sister, a woman who is hostile to their

mother and a relative stranger to the children.

In view of Mr. Eilers’ occupation and habits, it is ap

parent that the principal burden of caring for the children

will fall to his sister, Mrs. Mace. She is a comparative

stranger to the children having associated with them only

slightly since 1965 on occasional visits. In prior years she

had absolutely no contact with them (Tr. B. 91). She has

her own domestic relations problem, being separated from

her husband and planning a divorce (Tr. B. 90). She ad

mits her hostility to the children’s mother stemming from

an “emotional outburst” (Tr. B. 93), and states that as the

result of an argument with Mrs. Anderson years ago she

has not spoken with her again (Tr. B. 102).

By her own account, Mrs. Mace came to live with her

brother and maintain his household for her own financial

benefit, because she was separated from her husband and

could not find work (Tr. B. 89-91). Prior to this time she

had no contact with the children. Indeed, she had indicated

a marked disinterest in them, according to Mrs. Anderson

who testified that on one occasion during her marriage to

Eilers Mrs. Mace “called me from Elmira, New York, and

told me to take me and my family and get the hell out of

there and leave him alone” (Tr. B. 110).

Where a person having custody has such a marked

animosity toward the child’s mother, there is a likelihood

that she may poison the children’s minds against, and

alienate their affections from, their mother. This is a suffi

cient enough reason to deny placing the children in her

care. The courts have long recognized that parents have

a preferred right to their children in a contest with

strangers. Stapleton v. Poynter, 111 Ky. 264, 23 R. 76;

32

West v. West, 294 Ky. 301, 171 S.W.2d 453. It is patently

inimical to the welfare of children to remit them to the

care of a woman who is strongly hostile to their mother.

H. The Court’ s finding that two professional social workers

supported the conclusion that it was in the best inter

ests of the children to grant custody to the defendant is

clearly erroneous and without evidentiary support.

Two social workers, Mrs. Edna Millet and Mrs. Mary

Golden, were called as witnesses by the defendant George

Eilers. Both were employees of the Louisville and Jeffer

son County Children’s Home. Mrs. Millet worked with

the children in foster homes and Mrs. Golden with those

placed in institutions. Both of them testified about the

physical environment of Eilers’ home. Both of them de

clined to make a recommendation about which parent

should be given custody. Both of them gave the same rea

son, namely, that they had not performed the necessary

investigation and not had enough contact with the parents

to make a judgment. This was entirely consistent with

the testimony of their superior, Mr. Carpenter, who made

it plain, as the social workers did also, that the usual in

vestigation was not conducted and the normal processes

were not followed because of the Circuit Judge’s juris

diction over the case. All of them indicated their willing

ness to conduct an impartial investigation and make recom

mendations if requested to do so by the Court. We believe

that the criticism in the opinion below that the social

workers’ testimony “left much to be desired in the realm

of frankness and candor” (Supp. R. 27), was totally un

justified criticism, implying dishonesty where there was

none. But that is not essential to our point which is simply

that the social workers expressly disclaimed making a

judgment about, or knowledge of the facts relevant to a

decision about, the best placement for the children.

33

The testimony was cleai’ and unequivocal. Mrs. Millet

said:

I can’t make a recommendation, other than I defi

nitely approve of the physical aspects of Mr. Eilers’

home. That is the only aspect I took into considera

tion. We do not have jurisdiction to make a placement

in the father’s home, therefore, we went no further

than that (Tr. A. 182).

Mrs. Millet also said:

I ’m not making any recommendation. I don’t even

know Mrs. Anderson—we haven’t visited at all. As I

told you we requested the Indianapolis State Welfare

Department to give us an evaluation of her home. We

made that— (Tr. A. 185).

# # * * *

1023 I understand that. And I ’m trying to develop

the fact, I think is accurate, that because you’re not at

liberty to place them you have not done the things you

would do, to find out where they should be placed.

Is that right1?

A. That’s right. We haven’t gone any further than

superficially visiting them.

Her only investigation of Eilers’ home was conducted

to see if it would be a suitable place for the children to

visit on weekends (Tr. A. 184-185). She made no investiga

tion of the habits, background, occupations or other factors

with respect to Mr. Eilers or his sister, Mrs. Mace (Tr.

A. 187).

Mrs. Golden said that her one visit to the Eilers’ home

was to view the premises and that her contact with Mrs.

Mace was only casual (Tr. B. 9, 12-13); that her superiors

34

instructed her to be neutral in the case and not to reach

a conclusion on what placement would be best for the

children (Tr. B. 15-16); that she had not done some of the

things that would ordinarily have been done if she were

going to make a recommendation (Tr. B. 18); that she

had not had many interviews with the parents (Tr. B. 19);

that she had not made any investigation of Mr. Eilers’

or Mrs. Mace’s habits or temperament (Tr. B. 20-21); that

she knew nothing of Mrs. Mace’s background (Tr. B. 23);

that normally the agency would conduct a background in

vestigation of a relative before placing a child with her

(Tr. B. 23-24); and that she knew nothing about Mr. Eilers’

finances, associates, the people who came into his home,

and similar matters (Tr. B. 27).

We submit that the Chancellor’s reliance upon the social

workers’ testimony to support the finding that placement

with the father was in the children’s best interest was im

proper where the social workers had not made their usual

investigation, and where the Court had the power to obtain

the benefit of their expertise and judgment and to direct

a complete investigation but chose not to do so.

The reluctance of the social workers and their superiors

to make recommedations in this case in the absence of an

express request from the Court is readily understandable

in view of background events such as the Chancellor’s

summary overruling of a Juvenile Court order dividing-

custody between the parents (R. 25), and an unfortunate

episode in which the parents were not permitted visitation

rights during the 1965 Christmas period (Tr. A. 23-26,

50-54, 80-81, 97-98, 191-192; Tr. B. 28-29, 36-38).

35

II.

The Court Below Violated Appellant’s Rights Under

CR 43 .10 and the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States by Refusing to Allow Her to Make a Record

of Excluded Exhibits, Identify the Excluded Exhibits,

or Make an Avowal With Respect to the Exhibits, and

in Directing the Court Reporter Not to Record Appel

lant’s Counsel’s Remarks About the Exhibits.

During the presentation of appellant’s case at trial,

Lonnie C. Carpenter, Executive Director of the Louisville

and Jefferson County Children’s Home, was called as a

witness. He was the chief administrator of the tax-sup-

ported public child welfare agency (Tr. A. 71-72) to which

the children had been committed. On direct examination

the colloquy, which is set forth in full below, occurred

(Tr. A. 81-85):

373 Did there come a time, Mr. Carpenter, when

you—approximately March 14, 1966 when you under

took to write a letter to Judge Schmid and Judge

Schmid answered you—if I may, Your Honor, 1 would

like to have the witness identify the correspondence

with the Court.

The Court: The correspondence will not go in,

it was personal correspondence and it has no rela

tion to this case.

Mr. Nabrit: If it please the Court, the correspon

dence is already in the file jacket.

The Court: That’s all right, it’s in the file jacket,

hut it’s not part of the record.

Mr. Nabrit: I’m asking the witness to identify an

exhibit, a letter he wrote to the Court—

36

The Court: It was merely put in the file jacket

for my own personal convenience. It’s personal cor

respondence and it is not part of the record.

Mr. Nabrit: May it please the Court, may I be

heard in argument on this?

The Court: Yes sir.

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, it would seem to me

that correspondence between two public officials, a

member of the executive branch and a member of

the judicial branch, which relates to the status of