Covington v. Edwards Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Covington v. Edwards Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1959. 5d35b584-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/659df5fb-3e57-4aca-b262-9974dbaa72ec/covington-v-edwards-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

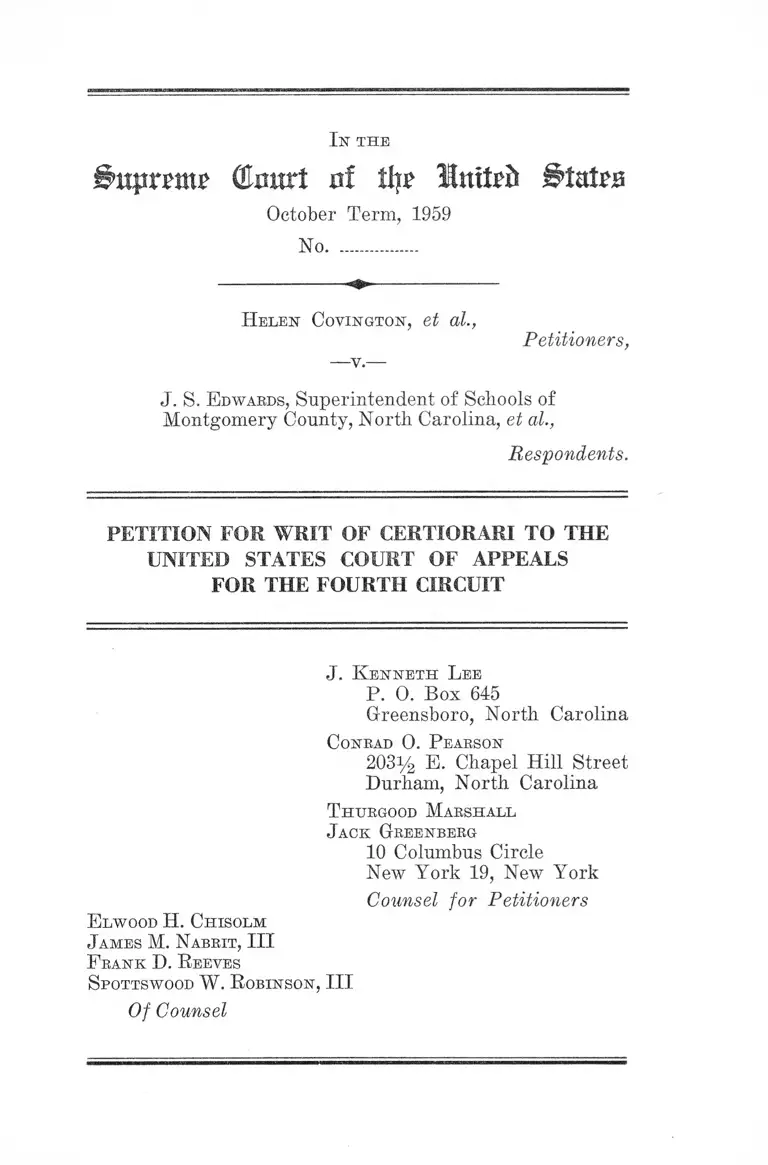

I n THE

Supreme dnurt of tl|J0 InttTft States

October Term, 1959

No..................

H elen C ovington, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

J. S. E dwards, Superintendent of Schools of

Montgomery County, North Carolina, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J. K en n eth L ee

P. 0. Box 645

Greensboro, North Carolina

C onrad 0 . P earson

203^> E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

T hubgood M arshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Petitioners

E lwood H. Chisolm

J ames M. N abrit, III

F ran k D. R eeves

S pottswood W. R obinson , III

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ...... - ............. -................. 1

Jurisdiction ........ .....................................-....................... 2

Question Presented .......-............................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 2

Statement .............................. - ... —................ .............. — 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ ....... ............. -............ 6

Conclusion ................. ........ -..... -----...................-............. 20

Appendix .... .... ..........................-.................................... 21

North Carolina Assignment and Enrollment of

Pupils Act - ................................................. - ...... 21

Opinion of the District Court...........-............ -...... 24

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ........................— 29

Decree of the Court of Appeals........ ............ -...... 35

T able of Cases :

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294 ......................... ..... ..........................3-8,11,13,16,17,19

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ...................-............ U

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County,

227 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir. 1955) ...................-........... - - 12

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ....... 12

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ................................ 6, 7, 8, 9,19

PAGE

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, 246 P. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957); 170 F. Supp.

454 (D. C. Fla. 1959) .................................................. 12,13

Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert, 330 U. S. 501....................... 16

Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U. S. 495 ................................ 16

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730

(5th Cir. 1958) ........................ ................................... 14

Holt v. Baleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d

95, 98 (4th Cir. 1959) .................................................. 12,18

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 2 4 ......................................... 19

Jeffers v. Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951 (D. C. N. C.

1958) ............................................................................. 18

Joyner v. Board of Education, 244 N. C. 164, 92 S. E.

2d 795 (1956) ................................................................ 9

Kelly v. Board of Education of the City of Nash

ville, 159 F. Supp. 272 (D. C. Tenn. 1958) ............... 15

McNabb v. United States, 318 U. S. 332 ...................... 16

Other A u th o ritie s :

11

Wolf son and Kurland, Robertson and Kirkham

Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United

States, §353 (1951) ...................................................... 16

I n the

(Emtrt nf Hit llmtth States

October Term, 1959

No..................

H elen C ovington, et al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

J. S. E dwards, Superintendent of Schools of

Montgomery County, North Carolina, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit, entered in the above-entitled case on

March 19,1959.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the District Court (R.1 49a), printed in

the Appendix hereto, infra, p. 24, is reported in 165 F.

Supp. 957. The opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals (R. 73), printed in the Appendix hereto, infra,

p. 29, is reported in 264 F. 2d 780.

1 R. refers to the record herein which consists of the appendices

to the briefs filed and the proceedings in the court below.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit was entered on March 19, 1959 (R.

81; p. 35, infra). On June 16, 1959 the Chief Justice ex

tended time for filing this petition to and including July

17, 1959. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

28 U. S. C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether the Fourteenth Amendment requires that re

spondent school officials devote every effort toward initiat

ing desegregation and bringing about the elimination of

racial discrimination in the public school system of Mont

gomery County, North Carolina, or whether, as the Courts

below held, the board may reject petitioners7 petition for

desegregation, continue its plan of segregated schools,

and relegate individual Negro children seeking their con

stitutional right to non-segregated education to a pupil

placement procedure whereby they must apply to particular

white schools in the school system which continues to be

conducted on a segregated basis.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the following constitutional provi

sions and statutes:

1. United States Constitution, Amendment 14, §1.

2. General Statutes of North Carolina, §§115-176 to

115-179. (North Carolina Assignment and Enrollment of

3

Pupils Act). The statute is printed in the Appendix, infra,

p. 21.2

Statement

The complaint in this action was filed on July 29, 1955

in the United States District Court for the Middle Dis

trict of North Carolina hy petitioners, a group of Negro

school children in Montgomery County, North Carolina,

and their respective parents and guardians as next friends

and individually, against respondents, the Superintendent

of Schools and the members of the Montgomery County

Board of Education.

The jurisdiction of the District Court was invoked pur

suant to 28 U. S. C. §1331, 28 IT. S. C. §1343, and 8 U. S. C.

§§41, 43 (which now appear as 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1983).

The action was brought as a class action pursuant to Rule

23(a)(3) Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

On September 7, 1954 Negro residents of Montgomery

County, North Carolina submitted a petition to respon

dents setting forth this Court’s holding in Brown v. Board

of Education, stating that in spite of that decision segrega

tion continued to be enforced in the county schools and

praying that they be desegregated (R. 23a, 24a). When

this petition was denied complaint was filed in the United

States District Court.

2 When this litigation commenced the North Carolina pupil

assignment statute had not yet been amended to its present form.

As originally written the statute provided that applications for

change of assignment should be directed to the appropriate public

school official. It now provides that application is to be made to

the board of education. None of the parties nor the courts below

have viewed this change as material to this suit (§115-178).

4

The principal allegations of the complaint3 are that re

spondents maintain racial segregation in the public schools

administered by them; that petitioners had filed a peti

tion with respondents requesting that segregation be abol

ished; and that respondents refused to abolish racial

segregation, all in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution, and 42 U. S. C. §1981.

The complaint prayed for an injunction ordering the re

spondents “ to promptly present a plan of desegregation to

[the] Court which will expeditiously desegregate the

schools in Montgomery County,” and for a general injunc

tion prohibiting racial segregation.

The answer in general pleaded that petitioners had failed

to exhaust an administrative remedy adopted by resolu

tion and subsequently, in substance, by statute, allowing

individual Negro children to seek change of assignment

from board imposed segregation; that respondents had no

power under then existing state statutes to act pursuant

to the petition seeking desegregation; and that respondents

had adopted a resolution denying the request for desegrega

tion. This resolution was set forth in haec verba in the

answer; it provided that the schools should continue to

operate during the then forthcoming 1954-55 school term as

they had in the past, awaiting the final decree of this Court

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, which was

then awaiting further argument on formulation of the

decree. The resolution stated:

The Board deems it for the best interest of public

education to await the final decree of the Court and

in the meantime operate the public schools of North

Carolina as now constituted (R. 15a).

3 Various preliminary proceedings in the District Court, unim

portant for purposes of this petition, including amendments to the

pleadings and several motions, are described in the opinion of the

District Court (E. 50a-51a).

The answer further asserts that after the 1955 decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, another resolu

tion, also set forth in the answer, was adopted by respon

dents. This resolution provided:

Now, therefore, be it resolved that the Public Schools

of Montgomery County operate during the 1955-56

term with practices of enrollment and assignment of

children similar to those in use during the 1954-55

school year, and that this resolution be the authority

for the County Superintendent and the various dis

trict school principals and officials to so act (E. 18a,

19a).

There was a proviso that parents dissatisfied with the as

signment of their children might apply to the principal

of the school to which assignment was desired, and if un

successful, to the county board of education, requesting a

change of assignment (R. 19a). The Court of Appeals

found that the system of planned segregation continues to

the present time, 264 F. 2d 780, 783; R. 78.

On March 26, 1958 respondents’ motion to dismiss the

complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief

could be granted, and petitioners’ motion for leave to file

a supplemental complaint4 and to add parties defendant,

were heard. The District Court granted the motion to dis

miss, and denied the motion to file a supplemental com

plaint and to add parties defendant, holding that since

petitioners had not alleged that they had exhausted the

remedies prescribed by the North Carolina Assignment

and Enrollment of Pupils Act they were not entitled to

injunctive relief in the federal courts, and that both the

original and the proposed supplemental complaints failed

4 The supplemental complaint would have made state education

officials parties defendant. That aspect of the case is not brought

here by this petition.

6

to state a claim upon which relief might be granted. The

District Court entered judgment dismissing the cause on

October 6, 1958 and the judgment was appealed to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

The Court of Appeals entered a decree affirming the judg

ment of the District Court on March 19, 1959.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The decision of the Court of Appeals conflicts with

the decisions of this Court in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion and Cooper v. Aaron.

The disposition the Court of Appeals made of this case

conflicts with the holdings of this Court that the Fourteenth

Amendment requires the state to discontinue its practice

of assigning pupils in its public schools on the basis of

their race. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483,

349 U. S. 294; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. As delineated

in Cooper, the constitutional injunction requires “ ‘a prompt

and reasonable start toward full compliance’ ” and action

“ necessary to bring about the end of racial segregation in

the public schools ‘with all deliberate speed’ ” (358 U. S.

at 7). Indeed, “ in many locations, obedience to the duty

of desegregation would require the immediate general ad

mission of Negro children, otherwise qualified as students

for their appropriate classes, at particular schools,” and

even where “ relevant factors” might establish justification

“ for not requiring the present nonsegregated admission of

all qualified Negro children” it is essential that the school

authorities show that they “had developed arrangements

pointed toward and had taken appropriate steps to put

their program into effective operation . . .” “ [0]n ly a

prompt start, diligently and earnestly pursued, to eliminate

7

racial segregation from the public schools could constitute

good faith compliance” {Id. at 7).

In sum, as this Court emphasized in Cooper:

State authorities were thus duty bound to devote

every effort toward initiating desegregation and bring

ing about the elimination of racial discrimination in

the public school system {Id. at 7).

and that,

State support of segregated schools through any

arrangement, management, funds, or property can

not be squared with the Amendment’s command that

no State shall deny to any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the laws {Id. at 19).

In 1954, Montgomery County ignored the first pronounce

ment in Brown and adhered to its pre-existing pattern of

racially separated public schools by resolving to continue

operation of the county’s then segregated schools as “ now

constituted” (R. 15a). It remained aloof to its constitu

tional responsibilities when, a year later, it resolved to

continue for 1955-56 “ practices of enrollment and assign

ment of children similar to those in use during the 1954-55

school year . . (R. 18a-19a). The Court of Appeals recog

nized the intransigent attitude of the school authorities

toward petitioners’ request for desegregation:

We are advertent to the circumstances upon which the

plaintiffs rest their case, namely, that the County Board

has taken no steps to put an end to the planned segre

gation of the pupils in the public schools of the county

but, on the contrary, in 1955 and subsequent years,

resolved that the practices of enrollment and assign

ment of pupils for the ensuing year should be similar

to those in use in the current year. 264 F. 2d at 783

(R. 78).

8

With this acknowledgment, the Court should at this

point have directed that petitioners be awarded injunctive

relief against the clear constitutional violation. Instead,

the Court held that respondents may continue the pattern

of segregated schools, resulting from the practice of assign

ment by race, if children are provided an administrative

procedure by the use of which they may individually seek

to escape the discrimination. The possibility of an escape,

it felt, is afforded by the board’s resolutions and the state

pupil assignment law, which for all relevant purposes are

the same; the District Court’s dismissal of the complaint

was affirmed on the ground that this “ remedy” should have

been exhausted. In short, it approved respondents’ prac

tice of initially assigning school children on a racial basis,

and requiring their attendance in segregated schools, simply

because each child might individually undertake an ad

ministrative course which might lead to his reassignment

to another school in an otherwise segregated system.

Such an arrangement falls far short of satisfying the

constitutional mandate that the state abstain from racial

classifications in its public school system. The continued

funneling of Negro children into Negro schools and the re

quirement that they continue attending such schools, even

though subject to the possibility of securing individual re

assignment to another school, does not constitute an ar

rangement for desegregating the schools or even a step in

that direction. Eather, it is a general requirement of racial

classification of all children until and unless particular

children may succeed in administratively excepting them

selves from its operation.

This Court’s decisions in Brown and Cooper establish

the right of all children to freedom from state imposed edu

cational segregation based on color. They make plain the

state’s duty to afford, not merely an ostensible freedom,

9

but freedom in fact, and do not contemplate an arrange

ment perpetuating segregation subject to an individual

administrative procedure by which that freedom can be

achieved only in isolated instances. Moreover, the command

of the Fourteenth Amendment against racial discrimina

tion is addressed to the state and is disobeyed by a require

ment that burdens the individual with the necessity of

demonstrating an exception in his favor from the general

policy of racial classification and discrimination which it

continues. Obviously, the state cannot be permitted to

shift to the individual the responsibilities which the Con

stitution imposes upon it. The duty is upon the state,

rather than the individual, to bring the unconstitutional

system which it has constructed to an end, and this duty,

like the right with which it is correlated, “ can neither be

nullified openly and directly by state legislators or state

executive or judicial officers, nor nullified indirectly by

them through evasive schemes for segregation whether

attempted “ingeniously or ingenuously.’ ” Cooper v. Aaron,

supra, 358 U. S. at 17. See also Lane v. Wilson, 307 IJ. S.

268.

Moreover, in petitioners’ view, the Pupil Assignment

Statute is irrelevant to the present issue and the doctrine of

exhaustion of administrative remedies has no application

to this case. The statute does not afford the administrative

means capable of furnishing the relief to which petitioners

are entitled; it neither requires segregation nor affords a

means of eliminating segregation. It permits continua

tion of a racially classified system— including the initial

assignment of first graders to segregated schools— subject

solely to the exception that individual Negro students5 may

5 No class proceedings are permitted under the Pupil Assignment

Statute. See the instant case at 264 F. 2d 783: Joyner v. Board of

Education, 244 N. C. 164, 92 S. E. 2d 795 (1956).

10

thereafter seek assignment to “ white” schools. Relevant

portions of the Act state:

If, at the hearing, the board shall find that the child

is entitled to be reassigned to such school, or if the

board shall find that the reassignment of the child to

such school will be for the best interests of the child,

and will not interfere with the proper administration

of the school, or with the proper instruction of the

pupils there enrolled, and will not endanger the health

or safety of the children there enrolled, the board shall

direct that the child be reassigned to and admitted to

such school. (Emphasis supplied.)

At most, this remedy could only enable a particular

child to secure entry to a particular school. Petitioners’

constitutional right is not so limited. They desire, and

view the Constitution as securing, the opportunity to attend

school in a nonsegregated system. Any administrative

remedy adequate from this viewpoint must be one which

affords an opportunity to abolish racial distinctions within

the school system and put an end to what the Court of

Appeals called “ the planned segregation of the pupils of

the public schools of the county.” 6 The placement statute

obviously does not supply such an opportunity.

Despite the shortcomings of the statute, however, the

school board, within the general powers conferred upon

it, could grant the type of relief which petitioners requested.

Petitioners pursued that administrative remedy by a peti

tion asking the board to prepare and pursue a plan of gen

eral desegregation. The petition charged that the board’s

segregation practices violated the Constitution and prayed

that “ all schools under your jurisdiction be immediately

desegregated in accordance with the Supreme Court’s deci

264 F. 2d at 783.

11

sion” (R. 24a). This the board refused to do, insisting

upon a power to continue segregation subject to individual

exceptions which may be sought via the pupil placement

plan. Similarly, the complaint in this case did not ask for

entry of a particular child to a particular school. It prayed

that the Court order “ defendants to promptly present a

plan of desegregation to this Court which will expeditiously

desegregate the schools in Montgomery County . . .” (R.

9a).

More fundamentally, neither the assignment statute nor

the exhaustion doctrine has relevance in this case save as

attempted justifications for respondents’ past and present

segregation practices. For it is because petitioners de

clined to undertake the statutory assignment procedures

that they have been denied relief by the school authorities

and the courts below. Meanwhile, respondents continue to

assign children to racially segregated schools, and assert

no present intention to abandon the practice, and seek

refuge in the assignment legislation when requested to

desist therefrom. But it is very clear that the constitutional

violations evident from respondents’ conduct cannot be ex

cused by resort to the statute. The Constitution, as inter

preted by this Court, incorporates “ the fundamental prin

ciple that racial discrimination in public education is

unconstitutional”—a doctrine supreme to the point that:

“All provisions of federal, state, or local law requiring or

permitting such discrimination must yield to this prin

ciple.” Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 298.

Neither the North Carolina assignment statute nor any

other law can justify the constitutional violations that re

spondents continue to commit, and, so long as these viola

tions continue, neither this Court nor the petitioners need

have concern with a state law having to do only with the

individual assignment of children to particular schools.

12

II.

The decision of the Court below conflicts with the

decisions of another Court o f Appeals, and the conflict

should be resolved by this Court.

The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has con

sistently held that state administrative remedies must he

exhausted prior to judicial application for relief from

segregated schooling. Carson v. Board of Education of

McDowell County, 227 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir. 1955); Carson

v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 353

U. S. 910. On the day that it decided the instant case it

also decided Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265

F. 2d 95, 98 (4th Cir. 1959), in which the Raleigh City

Board of Education also was found to be continuing racial

segregation. The Court held:

The regulations adopted by the Board in 1957, pur

suant to §115-176 of the statute, tended to perpetuate

the system, for they provided that each child attending

a school by assignment of the Board is assigned to

the same school for the ensuing school year.

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, however, has

recognized the constitutional infirmity in a position like

that taken by the Montgomery County Board and endorsed

by the Fourth Circuit. The Fifth Circuit in Gibson v. Board

of Public Instruction of Dade County, 246 F. 2d 913 (5th

Cir. 1957) dealt with an essentially identical legal situation.

The Dade County School Board had adopted a resolution

substantially the same as that adopted by the Montgomery

County Board. The Dade County Board had resolved:

“ It is deemed by the Board that the best interest of

the pupils and the orderly and efficient administration

of the school system can best be preserved if the regis

tration and attendance of pupils entering school com

13

mencing the current school term remains unchanged.

Therefore, the Superintendent, principals and all other

personnel concerned are herewith advised that until

further notice the free public school system of Dade

County will continue to be operated, maintained and

conducted on a nonintegrated basis” (at 914).

The plaintiffs in the Gibson case had requested, in lan

guage almost identical to the request of the plaintiffs in

the instant case, that “ the Board of Public Instruction . . .

abolish racial segregation in the public schools of the

County as soon as -is practicable in conformity with the

decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in

Brown v. Board of Education” (at 913). In defense the

Dade County Board had argued that plaintiffs had not

exhausted their administrative remedies provided by the

Florida Pupil Assignment Act. Judge Rives ruled that

recourse to the Pupil Assignment Act could not be re

quired until the policy of segregation is first abolished:

“ The appellees urge also that the judgment should

be affirmed because the plaintiffs have not exhausted

their administrative remedies under the Florida Pupil

Assignment Law of 1956, Chapter 31380, Lawrs of

Florida, Second Extraordinary Session 1956, F. S. A.

§230.-231. Neither that nor any other law can justify

a violation of the Constitution of the United States by

the requirement of racial segregation in the public

schools. So long as that requirement continues through

out the public school system of Dade County, it would

be premature to consider the effect of the Florida

laws as to the assignment of pupils to particular

schools.7

7 On remand to the district court, that court held that the state

pupil assignment law is a plan of desegregation. Gibson v. Board

of Public Instruction of Dade County, 170 F. Supp. 454 (D. Fla.

1959). This ruling is now on appeal.

14

“ The district court erred in dismissing the com

plaint. Its judgment is reversed and the cause re

manded” (at 913-914).

Similarly, in Holland v. Board, of Public Instruction, 258

F. 2d 730, Judge Rives held for the Court of Appeals that

the procedures afforded by the Florida Pupil Assignment

Act need not be employed until the policy of segregation

first was abolished in Palm Beach County. In that case,

it may be noted, the county continues to enforce a residen

tial segregation ordinance like that outlawed by Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60. But the question of residential

segregation was hardly crucial to the case as, obviously,

it is possible to have school desegregation with residential

segregation and vice versa. The fact of compulsory resi

dential desegregation merely served to underscore the dis

criminatory approach to law enforcement employed by the

county government.

In the Holland case the plaintiff had applied to a school

farther from his home than the Negro school to which he

was assigned. The District Court had indicated, among

other reasons, that because the plaintiff was assigned to

the nearest school his constitutional rights had not been

infringed. But, as Judge Rives wrote, “ that the plaintiff

was ineligible to attend the school to which he applied

would not, however, excuse a failure to provide nonsegre-

gated schools.” If the Pupil Assignment Statute had gov

erned it would seem that the distance of the “ white” school

from plaintiff’s home would have concluded the matter and

permitted the continued segregation of plaintiff.

While a conflict between a Court of Appeals and a Dis

trict Court is not as compelling a reason for granting

certiorari as a conflict between two Courts of Appeal,

it is worthy of note that, in addition to the difference be

tween the Fourth and Fifth Circuits, the United States

15

District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee is in

accord with the Fifth Circuit. In Kelly v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of Nashville, Judge William E. Miller ad

dressed himself directly to the rulings of the Fourth Cir

cuit. He pointed out that the relief which the Nashville

plaintiffs sought was not merely to attend a particular

school, but to attend schools in a system devoid of racial

classifications. The pupil assignment law did not furnish

a remedy ‘to achieve this end:

“ However, notwithstanding the apparent scope and

generality of the rulings of the Fourth Circuit in the

two cases just cited, the Court is unable to reach the

conclusion on the facts of the instant case that the

action should be dismissed and the plaintiffs remitted

to a so-called administrative remedy, with the implied

invitation to return to the Federal Court if that remedy

is exhausted without obtaining satisfactory results.

This is true because the Court is of the opinion that

the administrative remedy under the Act in question

would not be an adequate remedy. In this connection,

it must be recalled that the relief sought by the com

plaint is not merely to obtain assignment to particular

schools but in addition to have a system of compulsory

segregation declared unconstitutional and an injunc

tion granted restraining the Board of Education and

other school authorities from continuing the practice

and custom of maintaining and operating the schools

of the city upon a racially discriminatory basis.” 159

F. Supp. at 275.

The conflict is clear. While petitioners submit that the

Fifth Circuit is correct and the Fourth Circuit is wrong,

this Court, in any event, should resolve the difference in

the interest of uniformity where so important a constitu

tional right is involved.

16

III.

The decision below presents important questions of

federal jurisdiction, practice and procedure which

should be resolved by this Court.

This Court exercises supervision over the lower federal

judiciary to assure the proper and efficient functioning of

the District Courts. See, e.g., McNabb v. United States,

318 U. S. 332, 341 (administration of criminal justice);

Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert, 330 U. S. 501 (forum non con

veniens doctrine); Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U. S. 495 (con

struction of federal rules of civil procedure). This case

invokes such power. See W olf son and Kurland, Robertson

and Kirkham Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the

United States, §353 (1951).

In Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, this Court

provided certain general guides to the lower federal courts

for the disposition of school segregation litigation. In

delineating the type of matters to be considered by the

lower federal courts in framing decrees dealing with “ a

variety of local problems,” this Court emphasized the use

of “ practical flexibility” toward the end of eliminating “ a

variety of obstacles in making the transition to school sys

tems operated in accordance with the constitutional princi

ples set forth in [the] May 17, 1954 decision.” None of

these criteria even suggested that segregation may continue

to be maintained. But the Court of Appeals, while ex

plicitly recognizing that the respondent school board has

taken “ no steps to put an end to the planned segregation of

the pupils in the public schools of the country,” 264 F. 2d

at 783, held that petitioners and the class they represent,

were not entitled to require that respondents discontinue

the system of planned segregation. The remedy was held

to be an injunctive order requiring the admission of in

17

dividual Negro litigants to designated schools, after they

have exhausted the state’s prescribed administrative

“ remedy.” This view of the District Courts’ duty will ne

cessitate a detailed review of individual school assignments

by the federal judiciary for a very large number of pupils

who contend that they are excluded from particular schools

because of race. Insofar as the efficient functioning of the

federal judiciary is concerned, the burden of individual

review of school assignments promises to become insup

portable.8

At the second reargument of Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra, perhaps the most frequently voiced concern of

the parties and amici alike was that implementation of the

decision should not involve the federal judiciary in the

day-to-day administration of local school systems. Or, as it

was so often stated, the courts should not become school

boards.9

Indeed, although petitioners do not suggest that the

amicus curiae brief of the State of North Carolina in the

School Segregation cases is binding upon it in this litiga

tion, it is suggestive to note that in that brief the State

suggested as possible modes of compliance:

8 It is true that the Court of Appeals’ decision contemplates that

class action may be brought (R. 78). But the members of the class

are those who have employed the so-called Pupil Placement remedy.

Since the pupil placement remedy involves individualized consid

eration of each child’s right to attend a particular school a factual

review of each child’s right to attend a particular school is called

for. At best, then, the right to bring a class suit in this sense means

that many suits may be consolidated. Under petitioners’ view, how

ever, the courts should be concerned solely with the issue of whether

a racial standard is employed.

9 See, e.g., the Brief of Attorney General of Florida as amicus

curiae in Brown v. Board of Education, October Term, 1954 at

page 82; brief of Attorney General of the State of Texas as amicus

curiae at page 26; brief of the Attorney General of the State of

Arkansas as amicus curiae at page 18.

18

(1) Assignments of white and Negro children to schools

on the basis of residence alone;

(2) Segregation of children in schools on the basis of sex,

the basis of intelligence tests, the basis of achieve

ment tests, or any other basis except race, provided

only that the basis has a reasonable relation to the

proper conduct of the schools or to the maintenance

of the public safety, morals, health or welfare . . . ;

(3) Discontinuance of the present state-wide school sys

tem and leaving to each county or community the de

cision as to whether it will have public schools

operated on the one or the other of these bases. . . .

It is submitted that the choice to be made between

these or other methods leading to a constitutional

result is for the State of North Carolina.10

It was not suggested that segregation could be maintained

subject to individual transfers out of segregated schools.

Already federal courts in North Carolina have had before

them under the rule applied in this case11 a substantial

number of cases involving pupils on whose individual quali

fications to attend particular school buildings, or the regu

larity of the administrative proceedings in which they must

first seek vindication of their constitutional rights, the

courts must pass if the rationale of the instant decision is

correct.

10 At page 13.

11 See, e.g., Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d

95 (4th Cir. 1959) ; McKissick v. Durham City Board of Education

(D. C. M. C. N. C., Civil Action No. C-100-D-58) ; Morrow v.

Mecklenburg County Board of Education (D. C. W. D. N. C.,

Civil Action No. 1415); McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Educa

tion (D. C. M. D. N. C., Civil Action No. C-28-G-59) ; Cannon v.

Greensboro City Board of Education (D. C. M. D. N. C., Civil

Action No. C-25-G-59); Jeffers v. Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951 (D. C.

N. C. 1958).

19

Petitioners, however, view the federal judiciary’s role as

being solely to eliminate the use of racial standards in the

system and not to become involved in multitudinous in

dividual assignments. While an individual’s qualifications

might, of course, be relevant in attempting to ascertain

whether a board is employing subterfuge, a typical segre

gation suit should concern itself only with whether race is

used as a standard of school assignment. Where, as here,

race is used, it should merely be eliminated by application

of a constitutionally acceptable plan of desegregation.

Moreover, the proper functioning of the district court

was violated in yet another way. As Mr. Justice Frank

furter stated, concurring in Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24,

36, “ equity is rooted in conscience.” Equitable doctrines,

therefore, may not be invoked by those who, as that opinion

pointed out, violate the constitution of the United States

by racial discrimination—a violation not “narrow” or “ tech

nical,” but involving “ considerations that touch rights so

basic to our society that, after the Civil War, their protec

tion against invasion by the States was safeguarded by the

Constitution.” Here respondents segregate. WThen peti

tioners applied to equity for relief, respondents prayed that

the chancellor remit petitioners back to respondents in the

exercise of an equitable doctrine of self restraint. But, peti

tioners submit, a court of equity should not have its patience

invoked by those who have baldly continued to apply a con

stitutionally forbidden standard. Employment of such a

rule calls for the corrective supervision of this Court,

Unless the erroneous decision of the court below is recti

fied so that the District Court wall proceed in cases of this

sort under the general directions of Brown v. Board of

Education and Cooper v. Aaron discussed supra, not only

will the rights here involved continue to be denied, but the

Federal Courts will indeed become overburdened, and as

20

some have feared, in fact take on the role of local boards of

education in the name of equity at the behest of those who

have come into court without clean hands.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J . K e n n e t h L ee

P. 0. Box 645

Greensboro, North Carolina

C onrad 0 . P earson

20314 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

T hurgood M arshall

J ack G reenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Petitioners

E lwood H. Ch iso lm

J ames M. N abrit, III

F ran k D. R eeves

S pottswood W. R obinson , III

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

North Carolina Assignment and Enrollment

of Pupils Act Article 21

§ 115-176. County and city boards authorised to provide

for enrollment of pupils.—Each county and city board of

education is hereby authorized and directed to provide for

the assignment to a public school of each child residing

within the administrative unit who is qualified under the

laws of this State for admission to a public school. Except

as otherwise provided in this Article, the authority of each

board of education in the matter of assignment of children

to the public school shall be full and complete, and its

decision as to the assignment of any child to any school

shall be final. A child residing in one administrative unit

may be assigned either with or without the payment of

tuition to a public school located in another administrative

unit upon such terms and conditions as may be agreed

in writing between the boards of education of the admin

istrative units involved and entered upon the official rec

ords of such boards. No child shall be enrolled in or

permitted to attend any public school other than the

public school to which the child has been assigned by

the appropriate board of education. In exercising the au

thority conferred by this Section, each county and city

board of education shall make assignments of pupils to

public schools so as to provide for the orderly and efficient

administration of the public schools, and provide for the

effective instruction, health, safety, and general welfare

of the pupils. Each board of education may adopt such

reasonable rules and regulations as in the opinion of the

board are necessary in the administration of this Article.

§ 115-177. Authority to be exercised for efficient admin

istration of school, etc.; rules and regulations.—In exer-

22

cising the authority conferred by § 115-176, each county

or city board of education may, in making assignments

of pupils, give individual written notice of assignment,

on each pupil’s report card or by written notice by any

other feasible means to the parent or guardian of each

child or the person standing in loco parentis to the child,

or may give notice of assignment of groups or categories

of pupils by publication at least two times in some news

paper having general circulation in the administrative unit.

§ 115-178. Rearing before board upon denial of appli

cation for enrollment.— The parent or guardian of any

child, or the person standing in loco parentis to any child,

who is dissatisfied with the assignment made by a board

of education may, within ten (10) days after notification

of the assignment, or the last publication therefor, apply

in writing to the board of education for the assignment

of the child to a different public school. Application for

reassignment shall be made on forms prescribed by the

board of education pursuant to rules and regulations

adopted by the board of education. If the application for

reassignment is disapproved, the board of education shall

give notice to the applicant by registered mail, and the

applicant may within five (5) days after receipt of such

notice apply to the board for a hearing, and shall be en

titled to a prompt and fair hearing on the question of

reassignment of such child to a different school. A ma

jority of the board shall be a quorum for the purpose

of holding such hearing and passing upon application for

reassignment, and the decision of a majority of the mem

bers present at the hearing shall be the decision of the

board. If, at the hearing, the board shall find that the

child is entitled to be reassigned to such school, or if

the board shall find that the reassignment of the child

to such school will be for the best interests of the child,

and will not interfere with the proper administration

23

of the school, or with the proper instruction of the pupils

there enrolled, and will not endanger the health or safety

of the children there enrolled, the board shall direct that

the child be reassigned to and admitted to such school.

The board shall render prompt decision upon the hearing,

and notice of the decision shall be given to the applicant

by registered mail.

§ 115-179. Appeal from decision of board—Any person

aggrieved by the final order of the county or city board

of education may at any time within ten (10) days from

the date of such order appeal therefrom to the superior

court of the county in which such administrative school unit

or some part thereof is located. Upon such appeal the

matter shall be heard de novo in the superior court be

fore a jury in the same manner as civil actions are tried

and disposed of therein. The record on appeal to the

superior court shall consist of a true copy of the ap

plication and decision of the board, duly certified by the

secretary of such board. If the decision of the court be

that the order of the county or city board of education

shall be set aside, then the court shall enter its order

so providing and adjudging that such child is entitled

to attend the school as claimed by the appellant, or such

other school as the court may find such child is entitled

to attend, and in such case such child shall be admitted

to such school by the county or city board of education

concerned. From the Judgment of the superior court an

appeal may be taken by any interested party or by the

board to the Supreme Court in the same manner as other

appeals are taken from judgments of such court in civil

actions.

24

Opinion

I n th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe th e M iddle D istrict op N orth C arolina

R ock in g h am D ivision

Civil No. 323-R

# # # # $

S tan le y , District Judge:

The complaint in this action was filed on July 29, 1955,

as a class action by thirteen adult plaintiffs personally and

as next friend of forty-five minor plaintiffs, on behalf of

themselves and all other citizens and residents of Mont

gomery County, North Carolina, similarly situated. Named

as defendants are the Superintendent of Schools of Mont

gomery County, North Carolina, and the individual mem

bers of the Montgomery County Board of Education.

In their complaint, plaintiffs asked (1) that a three-judge

court be convened, (2) that interlocutory and permanent

judgments be entered “ declaring that Article IX, Section

2, of the North Carolina Constitution, and any customs,

practices and usages pursuant to which plaintiffs are

segregated in their schooling because of race, violate the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution” ,

and (3) that interlocutory and permanent injunctions

issue “ ordering defendants to promptly present a plan of

desegregation to this court which will expeditiously de

segregate the schools in Montgomery County and forever

restraining and enjoining defendants and each of them

from thereafter requiring these plaintiffs and all other

Negroes of public school age to attend or not to attend

public schools in Montgomery County because of race.”

25

Plaintiffs were allowed to amend their complaint on

August 12, 1955, but without changing the nature of their

cause of action. Thereafter, an order was signed denying

plaintiffs’ motion for a three-judge court.

After receiving an extension of time within which to

answer, the defendants filed their answer on September 12,

1955, alleging failure to exhaust administrative remedies

and lack of good faith on the part of the plaintiffs in bring

ing the action. Upon motion of plaintiffs, a portion of the

answer charging plaintiffs with lack of good faith was

stricken.

Thereafter, plaintiffs filed a motion to amend their com

plaint to allege that defendants are officers of the State of

North Carolina, enforcing and executing state statutes and

policies. After a hearing on this motion, an order was

entered by the court on December 16, 1955, allowing the

amendment.

On February 23, 1956, plaintiffs petitioned the court to

reconsider its order denying their motion for a three-judge

court. This motion was again denied in an opinion rendered

by Judge Johnson J. Hayes on April 6, 1956. Covington

v. Montgomery County School Board, 139 F. Supp. 161

(M. D. N. C., 1956).

On September 13, 1956, plaintiffs filed a motion for leave

to file amended and supplemental complaint and to add

parties defendant. In the supplemental complaint, plain

tiffs seek to test the constitutionality of certain state school

laws, commonly known and referred to as the “ Pearsall

Plan,” and seek to make the members of the State Board

of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion of the State of North Carolina parties defendant.

Thereafter, the Attorney General of the State of North

Carolina made a special appearance on behalf of members

of the Board of Education and the State Superintendent

of Public Instruction in opposition to plaintiffs’ motion,

26

and the defendants filed a motion to dismiss the complaint

for failure to state a claim on which relief could be granted,

and for failure to prosecute.

A hearing on pending motions was held on March 26,

1958, at which time the Court ordered the parties to file

briefs setting forth their legal contentions on all issues

raised by the pleadings and the pending motions. The At

torney General of the State of North Carolina was directed

to file a brief with the court with respect to his position on

all the issues raised in the pleadings.

The principal questions now before the court for deter

mination are (1) whether the complaint, or proposed

amended and supplemental complaint, states a claim against

the defendants on which relief can be granted, and (2)

whether the members of the State Board of Education and

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction are neces

sary and proper parties to the action.

The decision that has been reached on the first question

makes a determination of the second question unneces

sary for disposition of this case. However, in regard to the

second question, this court has today rendered an opinion

in another case, John L. Jeffers, et al. v. Thomas H. Whit

ley, Superintendent of the Public Schools of Caswell County,

et al., ------ F. Supp. ------ (D. C. M. D. N. C., 1958), in

which it was held that the members of the State Board of

Education and the State Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion are neither necessary nor proper parties in actions

of this type.

In regard to the first issue, it should be stated at the

outset that the plaintiffs have not alleged in either their

original complaint, or in their proposed amended and sup

plemental complaint, that there has been any exhaustion

of their administrative remedies as provided for in Sec.

115-176 through 115-178 General Statutes of North Caro

lina, known as the Enrollment and Assignment of Pupils

27

Act. Indeed, in their brief, plaintiffs admit that they did

not proceed nnder this act, and contend that exhaustion of

administrative remedies provided for by the act are

unnecessary.

Counsel for the plaintiffs make this contention in face

of the decisions rendered by the Court of Appeals for

this circuit in Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell

County, Cir. 4, 227 F. 2d 789 (1955), and Carson v. War licit,

Cir. 4, 238 F. 2d 724, certiorari denied 353 IT. S. 910,

77 S. Ct. 665, 1 L. Ed. 2d 664.

They advance the argument that the presumption relied

on in Carson v. Warlick, supra, that school officials “ will

obey the law, observe the standards prescribed by the

legislature, and avoid the discrimination on account of race

which the Constitution forbids” is not valid because of the

length of time that has passed since the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873

(1954), without the defendant’s acting to desegregate the

public schools of Montgomery County. The fallacy of this

argument is readily seen when one reflects on what the

Supreme Court actually held in the Brown case. As has

been repeatedly stated, the Brown case does not require

integration, but only holds that states can no longer deny

to anyone the right to attend a school of their choice on

account of race or color. Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp.

776 (E. D. S. C., 1955); Thompson v. County School Board

of Arlington County, 144 F. Supp. 239 (E. D. Va., 1956);

School Board of City of Newport News, Va. v. Atkins,

246 F. 2d 325 (1957).

Counsel for plaintiffs further contend that even if the

Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils Act is constitutional,

it need not be complied with in this case because the

provisions of the act are being unconstitutionally applied.

This argument is completely untenable in view of the fact

28

that there is no allegation that any of the plaintiffs ever

sought to comply with the provisions of the act. Not until

each of the plaintiffs has applied to the Board of Edu

cation of Montgomery County as individuals, and not as

a class, for reassignment, and have failed to be given the

relief sought, should the courts be asked to interfere in

school administration. Carson v. War lick, Supra.

The requirement for plaintiffs in suits of this type to

exhaust administrative remedies before seeking injunctive

relief in the federal court is discussed at some length in

the case of Joseph Hiram Holt, Jr. v. Raleigh City Board

of Education, ------ F. Supp. ------ (M. D. N. C., 1958),

decided on August 29, 1958. Reference is made to that

case for further discussion of my views on this subject.

In view of the plain holding of the Court of Appeals

for this circuit in the Carson cases, and in view of the

fact that the plaintiffs do not allege that they have ex

hausted, or have even attempted to exhaust, their admin

istrative remedies under the North Carolina Assignment

and Enrollment of Pupils Act, I conclude that the plaintiffs

have failed to state a claim against the defendants, in

either their original complaint or their proposed amended

and supplemental complaint, on which relief can be granted,

and that this action should be dismissed.

A judgment will be entered in conformity with this

opinion.

This the 12th day of September, 1958.

/ s / E d w in M. S tanley

United States District Judge

29

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or t h e F ourth C ircuit

No. 7802.

# # # # *

Before S obeloff, Chief Judge, and S oper and H ayn s-

w o rth , Circuit Judges.

# # #

P er C u r ia m :

The parents of a number of Negro children in Mont

gomery County, North Carolina, brought this suit to se

cure an injunction against the Superintendent of Schools

and the County Board of Education, directing the defen

dants to present a plan of desegregation of the races in

the schools and forbidding them to assign Negroes to

particular schools because of their race. The complaint

was filed on July 29, 1955, as a class action by thirteen

adults personally and as the next friends of the forty-five

minor plaintiffs, all of whom are Negroes. The defendants

filed an answer on September 22, 1955, alleging that the

plaintiffs had failed to exhaust the administrative remedies

provided by the State, in that they did not comply with

the statutes of the State which regulate the assignment

and enrollment of pupils in the public schools. On this

account, the defendants moved the court to dismiss the

suit, and the District Judge after hearing granted the

motion.

30

We are of the opinion that the present ease is ruled by

the prior decisions of this court in Carson v. Board of

Education, 227 F.2d 789, and Carson v. Warlick, 238 F.2d

724. In the first of these cases the following statement

was made in the per curiam opinion (page 790):

“ * * * The Act of March 30, 1955,* entitled ‘An

Act to Provide for the Enrollment of Pupils in Public

Schools’, being chapter 366 of the Public Laws of

North Carolina of the Session of 1955, provides for

enrollment by the county and city boards of education

of school children applying for admission to schools,

and authorizes the boards to adopt rules and regu

lations with regard thereto. It further provides for

application to and prompt hearing by the board in

the case of any child whose admission to any public

school within the county or city administrative unit

has been denied, with right of appeal therefrom to the

Superior Court of the county and thence to the Su

preme Court of the state. An administrative remedy

is thus provided by state law for persons who feel

that they have not been assigned to the schools that

they are entitled to attend; and it is well settled that

the courts of the United States will not grant injunc

tive relief until administrative remedies have been

exhausted. * * * ”

This case was brought to this court a second time, in

Carson v. Warlick, supra, after the Supreme Court of

North Carolina in Joiner v. McDowell County Board of

Education, 244 N.C. 164, had interpreted the Pupil Place

ment Act of the State, and had held that the factors in

volved in the selection of appropriate schools for a child

* This act in its present form is found in the General Statutes.

of North Carolina, Chapter 115, Article 21, Secs. 115-176 to 115-179.

Changes of assignment are regulated by Sec. 115-178.

31

necessitated the consideration of the application of any

child or children individually and not en masse. It was

shown to this court that the plaintiffs, in the action in the

court below, had not attempted to comply with the pro

visions of the statute as so interpreted but had merely

inquired of the Secretary of the Board of Education what

steps were being taken for the admission of colored chil

dren to the schools of the town of Old Fort, and that

the school authorities in reply merely pointed out that

no Negro pupil had made application to attend the school

and that the board therefore had no cause to take any

action in that connection. We therefore reaffirmed our

previous decision and held that the plaintiffs were not

entitled to relief because they had not exhausted their

administrative remedies. In the course of the opinion

Judge Parker said (238 F.2d at 728-729):

“ Somebody must enroll the pupils in the schools.

They cannot enroll themselves; and we can think of no

one better qualified to undertake the task than the

officials of the schools and the school boards having

the schools in charge. It is to be presumed that these

will obey the law, observe the standards prescribed

by the legislature, and avoid the discrimination on

account of race which the Constitution forbids. Not

until they have been applied to and have failed to

give relief should the courts be asked to interfere in

school administration. As said by the Supreme Court

in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 299,

1 * * * g c]200} authoi'ities have the primary respon

sibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these

problems; courts will have to consider whether the

action of school authorities constitutes good faith

implementation of the governing constitutional prin

ciples’.

32

“ It is argued that the statute does not provide an

adequate administrative remedy because it is said that

it provides for appeals to the Superior and Supreme

Courts of the State and that these will consume so

much time that the proceedings for admission to a

school term will become moot before they can be com

pleted. It is clear, however, that the appeals to the

courts which the statute provides are judicial, not

administrative remedies and that, after administrative

remedies before the school boards have been ex

hausted, judicial remedies for denial of constitutional

rights may be pursued at once in the federal courts

without pursuing state court remedies. Lane v. Wilson,

307 U.S. 268, 274. Furthermore, if administrative

remedies before a school board have been exhausted,

relief may be sought in the federal courts on the basis

laid therefor by application to the board, notwith

standing time that may have elapsed while such appli

cation was pending. Applicants here are not entitled

to relief because of failure to exhaust what are un

questionably administrative remedies before the board.

“ There is no question as to the right of these school

children to be admitted to the schools of North Caro

lina without discrimination on the ground of race.

They are admitted, however, as individuals, not as a

class or group; and it is as individuals that their rights

under the Constitution are asserted. Henderson v.

United States, 339 U.S. 816. It is the state school au

thorities who must pass in the first instance on their

right to be admitted to any particular school and the

Supreme Court of North Carolina has ruled that in

the performance of this duty the school board must

pass upon individual applications made individually

to the board. The federal courts should not condone

dilatory tactics or evasion on the part of state officials

in according to citizens of the United States their

rights under the Constitution, whether with respect

to school attendance or any other matter; but it is

for the state to prescribe the administrative procedure

to be followed so long as this does not violate con

stitutional requirements, and we see no such violation

in the procedure here required. * * * ”

We are advertent to the circumstances upon which the

plaintiffs rest their case, namely, that the County Board

has taken no steps to put an end to the planned segregation

of the pupils in the public schools of the county but, on the

contrary, in 1955 and subsequent years, resolved that the

practices of enrollment and assignment of pupils for the

ensuing year should be similar to those in use in the

current year. If there were no remedy for such inaction,

the federal court might well make use of its injunctive

power to enjoin the violation of the constitutional rights

of the plaintiffs but, as we have seen, the State statutes

give to the parents of any child dissatisfied with the school

to which he is assigned the right to make application for

a transfer and the right to be heard on the question by

the Board. If after the hearing and final decision he is

not satisfied, and can show that he has been discriminated

against because of his race, he may then apply to the

federal court for relief. In the pending case, however,

that course was not taken, although it was clearly out

lined in our two prior decisions, and the decision of the

District Court in dismissing the case was therefore correct.

This conclusion does not mean that there must be a sepa

rate suit for each child on whose behalf it is claimed

that an application for reassignment has been improperly

denied. There can be no objection to the joining of a

number of applicants in the same suit as has been done

in other cases. The County Board of Education, however,

33

34

is entitled under the North Carolina statute to consider

each application on its individual merits and if this is

done without unnecessary delay and with scrupulous ob

servance of individual constitutional rights, there will be

no just cause for complaint.

The appellants also raise the point that the District

Judge was wrong in rejecting the motion of the plaintiffs

to amend the bill of complaint by joining the State Board

of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction

of the State as parties defendant. It is pointed out that

the State Board has general control of the supervision

and administration of the fiscal affairs of the public schools

and other important powers conferred by the General

Statutes, secs. 115-4, 115-11 and 115-283. The provisions

of sec. 115-178 of the Pupil Placement Act, however, places

the authority in the County boards of education to make

the assignments and enrollment of pupils and contains no

direction for the participation of the State Board of

Education in these matters. We therefore think that

nothing would be gained by joining these officials as addi

tional defendants and that the judge was correct in denying

the motion to amend the complaint.

Affirmed.

35

Decree

Filed and Entered March 19, 1959.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 7802.

H elen C ovington , p erson a lly and as m other and next

fr ie n d o f C ornett C ovington , et al.,

—vs.—

Appellants,

J . S. E dwards, Superintendent of Schools of Montgomery

County, North Carolina, E. R. W allace , D. C. E w in g ,

H arold A. S cott, J ames R. B urt and J ames I ngram ,

members of the Montgomery County Board of Edu

cation,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina.

T his cause came on to be heard on the record from the

United States District Court for the Middle District of

North Carolina, and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof, It is now here ordered, ad

judged and decreed by this Court that the judgment of the

said District Court appealed from, in this cause, be, and

the same is hereby, affirmed with costs.

March 19, 1959.

S im on E. S obeloff

Chief Judge, Fourth Circuit.