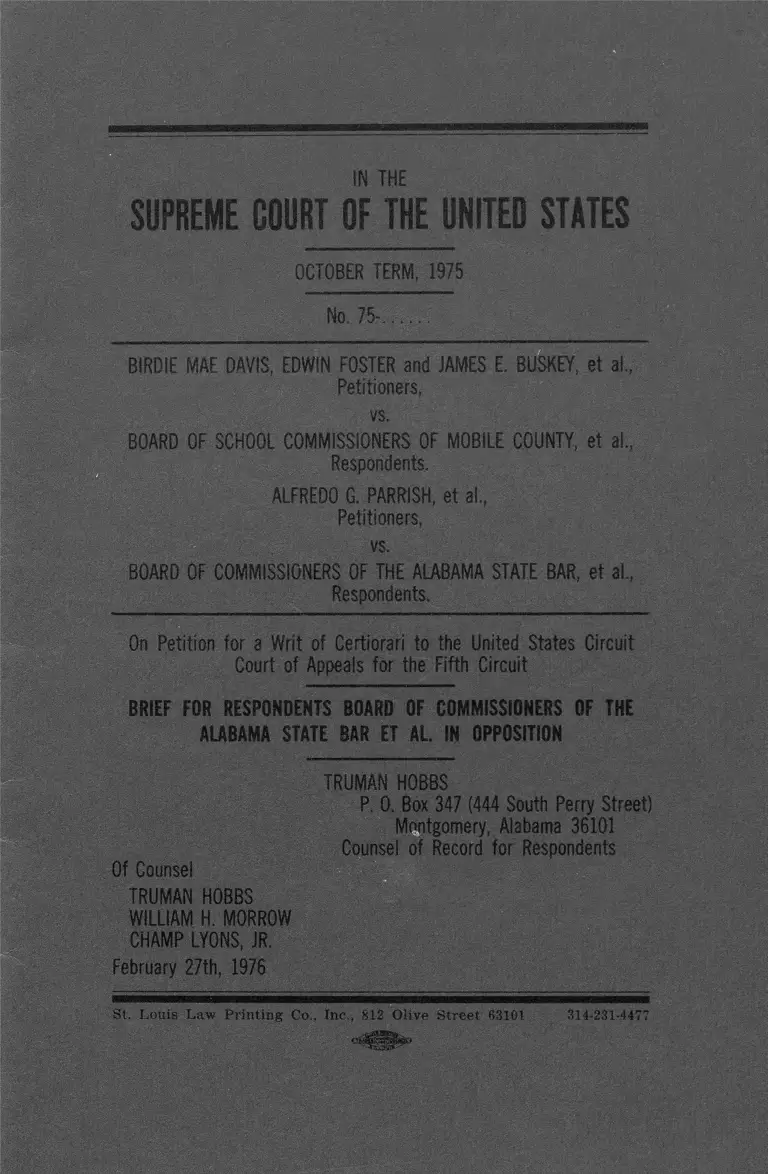

Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Brief for Respondents Board of Commissioners of the Alabama State Bar et al. in Opposition

Public Court Documents

February 27, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Brief for Respondents Board of Commissioners of the Alabama State Bar et al. in Opposition, 1976. 93a70316-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/65dbc456-269b-4368-a363-1872656d05ef/davis-v-mobile-county-board-of-school-commissioners-brief-for-respondents-board-of-commissioners-of-the-alabama-state-bar-et-al-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TER M , 1975

No, 75-

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS, EDWIN FOSTER and JAM ES E. BUSKEY, et at.,

Petitioners,

VS. ' :

BOARD OF SCHOOL COM M ISSIONERS OF M OBILE CO U N TY, et at.,

Respondents.

ALFREDO G. PARRISH, et ai„

Petitioners,

vs.

BOARD OF COM M ISSIONERS OF TH E ALABAM A S TA TE BAR, et a!.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a W rit of Certiorari to the United States C ircuit

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS BOARD OF COM M ISSIONERS OF THE

ALABAMA S TA TE BAR ET AL. IN OPPOSITION

TR U M A N HOBBS

P. 0. Box 347 (444 South Perry Street)

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

Counsel of Record for Respondents

Of Counsel

TR U M AN HOBBS

W ILLIAM H. MORROW

CHAM P LYONS, JR.

February 27th, 1976

St. Louis Law Prin ting Co., Inc., 812 Olive S tree t 63101 314-231-4477

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions Below ..................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ........................................ 2

Statutes and Rules Involved.................................................... 2

Statement of the C a s e ............................................................ 3

Argument ................................................................................ 6

Reasons for Denying the W r it .......................................... 6

I. To review interlocutory order while case is still

pending in court of appeals is inappropriate........... 6

II. The court of appeals and trial judge properly re

solved the issue of recusal ........................................ 8

III. The alleged conflict between holdings of this court

and the decision below is non-existent...................... 12

Conclusion ............................................................................... 14

Certificate of Service ........................................ 15

Table of Cases

American Const. Co. v. Jacksonville T & T R. Co., 148

U.S. 372 ....................................................... 6

Berger v. U. S„ 255 U.S. 2 (1921)..................................9, 12, 13

Board of Commr’s v. State ex rel. Baxley, 10 ABR 239,

Dec. 4, 1975 ....................................................................... 4

Cobbledick v. U. S., 309 U.S. 323 ...................................... 7

ii

Hamilton Brown Shoe Co. v. Wolf Bros., 240 U.S. 251 . . 7

Pfizer v. Lord (CA 8), 456 F.2d 532 ............................... .. 13

Simpson v. Ala. State Bar Asso., 9 ABR 1120, — Ala.

— ,311 So.2d 307 ........................................................... 4

U. S. v. Thompson (3 CA), 483 F.2d 527 ........................ 13

Statutes and Rules Cited

Rule 20— Rules of the Supreme C o u rt................................. 2, 7

Title 46, Section 21, Alabama C o d e ................................. 11

28 U.S.C. Section 144 ....................................................... 3,13

28 U.S.C. Section 455 ..........................................................3, 12

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM , 1975

No. 75-

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS, EDWIN FOSTER and JAMES E. BUSKEY, et al„

Petitioners,

vs.

BOARD OF SCHOOL COM M ISSIONERS OF M OBILE CO U N TY, et al„

Respondents,

ALFREDO G. PARRISH, et at.,

Petitioners,

vs.

BOARD OF COM M ISSIONERS OF TH E ALABAM A STA TE BAR, et a!.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a W rit of Certiorari to the United States Circuit

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS BOARD OF COM M ISSIONERS OF THE

ALABAMA S TA TE BAR ET AL. IN OPPOSITION

Respondents will reply only to that portion of the petition

for certiorari which has reference to Parrish v. Board of Com

missioners.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The petition for certiorari has attached as an appendix to

the petition the opinions of the courts below. See page 36a,

et seq., of the Appendix to the petition for certiorari for the

opinion of the Court of Appeals en banc from which peti

tioners seek to have review in Parrish v. Board of Commis

sioners.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

In addition to the question presented by petitioners, there

is a threshold question:

1. Is the petition for certiorari in Parrish v. Board of Com

missioners inappropriate and in violation of Rule 20 of the

Revised Rules of this Court in that it involves an effort to

obtain review of an interlocutory order while this case is still

pending in the Court of Appeals, the case having been re

manded by the Court of Appeals en banc to the original panel

in that Court which first heard the appeal from the district

court?

2. Did the Court of Appeals properly hold that the fed

eral district judge in Parrish v. Board of Commissioners was

not required on the facts alleged in the affidavit to recuse

himself?

STATUTES AND RULES INVOLVED

Rule 20 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the United

States, which is as follows:

“A writ of certiorari to review a case pending in a

court of appeals, before judgment is given in such court,

3 —

will be granted only upon a showing that the case is of

such imperative public importance as to justify the de

viation from normal appellate processes and to require

immediate settlement in this court.”

28 U.S.C. Sec. 144, and 28 U.S.C. Sec. 455 prior to its

amendment in 1974 and said section as amended.

The statutes are set out in petitioners’ brief.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In Parrish v. Board of Commissioners, petitioners are seek

ing review of an order of the trial judge declining to recuse

himself. The case was decided by the trial judge by an order

granting summary judgment. The case was appealed to the

Fifth Circuit. A three judge panel in that court decided the

judge should have recused himself and remanded. Subse

quently, the opinion was withdrawn on the Court’s own mo

tion, and the Court of Appeals en banc held that the action

of the trial judge on the motion to recuse was proper, and

remanded the case for further disposition to the original panel.

In the district court, when the trial court was advised that

petitioners might wish to file a motion asking the judge to

recuse himself, the trial judge invited counsel for petitioners

to examine him with reference to such a motion. This exam

ination of the judge developed the sole facts on which the

affidavit seeking recusal was based. These facts are:

(1) The trial judge was acquainted with several of the de

fendant bar examiners. Some had been adversary counsel in

prior litigation; some of them he knew slightly; and some,

not at all. He knew the attorneys representing the defendants.

(2) The trial judge was a friend of a former Secretary of

the Bar Commission who petitioners’ counsel stated would be

called as an adverse witness. In response to questions from

4 —

petitioners’ counsel concerning whether Mr. Scott’s being a

witness would present any problems for the trial judge, the

trial judge stated that he thought Mr. Scott was an honorable

man. “But I don’t think his memory is infallible. I think he

would try to tell you the truth in his answers. But if he ap

peared to evade I think I could detect it.”

(3) The judge was asked if there was conflicting testimony

between a witness he did not know and “a defendant who you

do know, slightly or otherwise, might there be any problem in

your attaching more weight to the testimony of the person

that you know rather than the person who you do not know.”

He said he did not believe he would have any bias or prejudice

about the matter. He said of the people he did know he would

“have no reason to think any of them would intentionally mis

represent anything.” (Tr. 61)

(4) The trial judge was President of the Montgomery County

Bar Association before becoming a federal judge. When serving

as its president, he learned that the by-laws of that bar as

sociation barred Blacks from membership. He appointed a

committee to study and recommend changes in the by-laws. Al

though he made no specific recommendations, the bar associa

tion on the recommendation of the committee did change the

association’s by-laws to remove any racial exclusion. The judge

never extended an invitation to a Black lawyer to join the

association, although he knew Black lawyers who were prac

ticing in Montgomery County.1

1 The Montgomery County Bar Association is a voluntary associa

tion which has no official status and is not an arm of the Alabama Bar

Association. The Alabama Bar Association has been an integrated

Bar Association with its membership open to all practicing attorneys

within the State of Alabama at least since 1923. Its membership has

included Black lawyers for several decades. Only the Alabama Bar

Association acting as the arm of the Supreme Court of Alabama, has

any role in the admission, discipline or removal of attorneys in Ala

bama. Simpson v. Ala. State Bar Asso., 9 ABR 1120, — Ala. —,

311 So.2d 307; Board of Commr’s v. State ex rel. Baxley, 10 ABR

239, Dec. 4, 1975.

— 5

After months of exhaustive discovery pursued by petitioners,

and when petitioners were unable to present any evidence to

challenge the sworn affidavits from all of the defendant ex

aminers and the Secretary of the Bar Association that all ex

aminations were graded with complete anonymity as to the race

and identity of the applicants,2 the trial judge granted the re

spondents’ motion for summary judgment.

2 The only evidence which had any claimed challenge to the affi

davits of the bar examiners and Secretary of the Association came

from the affidavits of two plaintiffs who said it “might be possible” for

a bar examiner to determine the race or identity of an examinee.

— 6 —

ARGUMENT

Reasons for Denying the Writ

In the proceedings in the trial court, respondents took no

position relative to the motion of petitioners for recusal of the

judge. Respondents did not participate in any way in the inter

rogation of the judge. Respondents took the position in the trial

court that the matter of recusal was one largely of judicial ad

ministration and that respondents had no interest in this case

being considered by any particular judge. It was for this reason

that respondents did not ask for reconsideration of the opinion

of the original panel hearing the appeal that the trial judge

should have recused himself, which opinion was vacated by the

Court of Appeals en banc. The Court of Appeals reversed the

three judge panel on its own motion.

Although respondents have no interest in this case being con

sidered by any particular judge, respondents do have an interest

in bringing to an end this litigation which has already consumed

more than three years from the date of the filing of the com

plaint. Accordingly, respondents will respond to the petition

for certiorari.

I

To Review Interlocutory Order While Case Is Still Pending

in Court of Appeals Is Inappropriate.

The petition in Parrish v. Board of Commissioners seeks

review by this Court of an interlocutory order of the Court of

Appeals and it seeks such review while the case is still pending

in the Court of Appeals.

This Court has repeatedly declined to review interlocutory

orders. In American Const. Co. v. Jacksonville T & T R. Co.,

148 U.S. 372, 384, this Court stated:

— 7

“Clearly, therefore, this Court should not issue a writ

of certiorari to review a decree of the Circuit Court of

Appeals on appeal from an interlocutory order, unless it

is necessary to prevent extraordinary inconvenience and

embarrassment in the conduct of the cause.”

See also Cobbledick v. U. S., 309 U.S. 323, 324; Hamilton

Brown Shoe Co. v. Wolf Bros., 240 U.S. 251, 258. Moreover,

this Court’s own rules prohibit review of cases pending in a

court of appeals before judgment is given in such court, ex

cept “upon a showing that the case is of such imperative public

importance as to justify the deviation from normal appellate

processes and to require immediate settlement in this Court.”

Rule 20, Supreme Court Practice. No such showing of impera

tive public importance is even claimed in the instant petition.

In the instant case, petitioners are not only seeking review of

an interlocutory order, but they seek it while the case is still

pending before a panel of the Court of Appeals. This case was

remanded to such panel by the Court of Appeals en banc on

December 4, 1975. One of the purposes of the rule against

issuing a writ of certiorari of this Court to review interlocutory

orders is to prevent piecemeal disposition of a single contro

versy, thereby avoiding “the obstruction to just claims that would

come from permitting the harassment and cost of a succession

of separate appeals from the various rulings to which a litiga

tion may give rise, from its initiation to entry of judgment. To

be effective, judicial administration need not be leaden-footed.

Its momentum would be arrested by permitting separate reviews

of the component elements in a unified cause.” Cobbledick v.

U.S., 309 U.S. 323, 325.

The momentum in the instant case does not need any further

retarding, since it has now been more than two years since the

trial judge entered his order granting summary judgment. The

effect of further review on the recusal issue would add more

8 —

months of delay on an issue which is in no way decisive. The

issue still pending before the Court of Appeals is whether any

genuine issue of fact exists which would require reversal of the

summary judgment. If the Court of Appeals finds there is no

such issue, the action of the trial judge on recusal is irrelevant.

II

The Court of Appeals and Trial Judge Properly Resolved the

Issue of Recusal.

Petitioners contend that the trial judge should have recused

himself because he was personally acquainted with a number

of the defendants and their counsel, and he was not acquainted

with the plaintiffs. The trial judge set out the basis of his ac

quaintance with respondents and their counsel. The relation

ship was largely based on the trial judge’s years of trying law

suits as adversaries with some of the respondents and their coun

sel and an acquaintance with them as lawyers. Petitioners cite

not one case which remotely suggests that such an acquaintance

is ground for recusal. Probably most district judges have an

acquaintance with most of the trial lawyers practicing before

them. A rule requiring recusal because of such acquaintance

would be novel and burdensome to judicial administration.

Petitioners’ petition at page 14 states that the trial judge

“candidly conceded his belief that the key defense witness, the

Secretary of the Commission, a close personal friend of the

judge, would not lie.” Only in this brief by petitioners is Mr.

Scott called “a key defense witness.” Even in the affidavit seek

ing the judge’s recusal, Mr. Scott is only referred to as one whom

the plaintiffs propose to call as an adverse witness. Mr. Scott

is not the Secretary of the Commission as stated by petitioners.

He has had no position with the Commission since his retirement

as Secretary in May, 1969.

9

There is no basis for the statement that Mr. Scott is “a close,

personal friend” of the trial judge. The trial judge stated that

Mr. Scott was a friend, that he had in years past tried one or

two cases in which Mr. Scott was involved as co-counsel. The

testimony with reference to Mr. Scott was as follows:

Q. Judge, Mr. Scott will be one of the witnesses, either

by deposition, or otherwise, in this case, and I did want to

call that to your attention. There will be some docu

mentary evidence which I am sure the defendants will dis

cover, relating to a written communication by Mr. Scott—

or we say by Mr. Scott—concerning black lawyers and

their association. Do you think that your association with

Mr. Scott would influence the weight to which you might

attach to that type of evidence?

A. I think Mr. Scott is an honorable man. But I don’t

think his memory is infallible. I think he would try to

tell you the truth in his answers. But if he appeared to

evade I think I could detect it.

Q. Do you know what Mr. Scott’s position is now?

A. Oh, I think Mr. Scott has retired.

Q. Well, did you all visit in each other’s homes?

A. We don’t regularly. I don’t recall ever having been

in Mr. Scott’s home. I know he hasn’t been in my home.

I am quite sure I have not visited Mr. Scott.

It is puzzling to know where in the statutes relied on by

petitioners or in any case anywhere a trial judge is deemed dis

qualified because he is an acquaintance or a friend of a witness

expected to be called to testify. Such acquaintance does not

give “fair support to the charge of a bent of mind that may

prevent or impede impartiality of judgment.” Berger v. U. S.,

255 U.S. 2 (1921).

— 1 0 -

Petitioners suggested that the judge was biased in favor of

the credibility of Mr. Scott and certain of the defendants be

cause in response to a question he stated that he didn’t believe

such persons would intentionally misrepresent or perjure them

selves. The opinion of the court below correctly characterized

the trial judge’s response to questions as to the credibility of

such persons as “no more than an acknowledgement of friend

ship or acquaintanceship, and a refusal to condemn those per

sons as unworthy of belief in advance of whatever their testi

mony might prove to be.” Every witness is entitled to a

presumption that he speaks the truth. The fact that the trial

judge acknowledged that he would accord this presumption to

the witness Mr. Scott and to the defendants of his acquaintance

is not ground for his recusal.

Petitioners also argue that the trial judge should have recused

himself because he had been President of the Montgomery

County Bar Association at a time when that Bar Association

had a prohibition in its by-laws against the admission of Blacks

to membership. The trial judge stated that after learning of

the prohibition, he appointed a committee to study the Bar

Association’s by-laws and to make recommendations as to pro

posed changes. The committee appointed by the trial judge

made a recommendation that the prohibition be removed and it

was removed.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals points out that there

is hardly any judge in the Fifth Circuit who was not a member

of a segregated bar association at one time. The action of this

trial judge in becoming president of a bar association which

still had a prohibition against such minority membership and

taking steps as president which resulted in the elimination of

such discrimination hardly raises a reasonable inference of per

sonal bias or prejudice by such trial judge as to these petitioners.

The Court of Appeals correctly held that the factual bases

alleged for recusal did not raise an inference of personal bias

or prejudice.

— 11

Petitioners also claim that since the trial judge was a member

of the Alabama Bar Association which is supported by license

fees of its members, the trial judge has a financial interest in

the litigation in that he would indirectly be liable for any court

costs, counsel fees or damages which might be awarded. All

lawyers who practice law in Alabama are compelled to be

members of the Alabama Bar Association, which is an organiza

tion established by the Alabama Legislature. Title 46, Sec. 21,

et seq., of the Alabama Code. If such a tenuous “financial in

terest” is ground for recusal, then a judge who is a taxpayer of

a city or state should be forced to disqualify himself in cases

where his city or state has a financial interest. Would a federal

judge have a disqualifying “financial interest” in a suit against

the United States which pays his salary? Obviously not. No

reasonable basis exists for a belief that such membership by the

trial judge in the Alabama Bar Association would cause him

to have a financial interest in this litigation.

Finally, petitioners assert that the trial judge is being repre

sented by one of the attorneys for the defendants in an unre

lated matter, and that this circumstance requires the trial judge’s

recusal. Petitioners neglect to inform this Court that such

representation did not occur until approximately two years

after the trial judge ruled on the summary judgment motion

and the instant case was appealed from his court. The Court

of Appeals was reviewing, among other things, whether the

trial judge erred in failing to recuse himself. It is novel to sug

gest that a circumstance occurring nearly two years after the

appeal was taken from that trial judge’s court is ground for

reversal of his action in ruling on summary judgment.

If this case is ever remanded to the trial judge for further

proceedings, it is reasonable to assume that the trial judge would

consider any motion to recuse based on facts existent at that

time. It is totally unreasonable to suggest that a trial judge be

reversed because he failed to recuse himself when the grounds

— 12

of such recusal were not even existent at the time the case was

appealed from such judge’s court.

Respondents have not argued whether Sec. 455 as amended

is applicable to the motion to recuse in this case. Respondents

agree with the majority opinion of Judge Bell that whether the

standard for considering the recusal motion is under Section 155

or the amended Section 455, the affidavit for recusal is insuf

ficient. We also agree, however, with Judge Roney’s concurring

opinion that Section 455 as amended did not apply to this

trial which was completed and summary judgment granted on

August 21, 1973. Congress provided that the new Section 455

“shall not apply to the trial of any proceeding” commenced

prior to December 5, 1974. As Judge Roney stated: “We are

judging the correctness of that trial and should do so by the

standard applying to it as clearly set forth in the statute.”

Ill

The Alleged Conflict Between Holdings of This Court and

the Decision Below Is Non-Existent.

Petitioners assert that a significant conflict exists between the

Courts of Appeal in that some of them have followed the stand

ard for recusal laid down in Berger v. U. S., 255 U.S. 22,

whereas other circuits and the opinion below are inconsistent

with Berger. This alleged conflict would undoubtedly come as

a surprise to the author of the majority opinion in this case

which repeatedly relies on and quotes from Berger. For ex

ample, the opinion below quotes as follows from Berger:

“The facts and reasons set out in the affidavit ‘must give

fair support to the charge of a bent of mind that may pre

vent or impede impartiality of judgment.’ Berger v. U.S.,

supra, 255 U.S. at 33.”

— 13 —

The majority opinion below also quotes, discusses and fol

lows, U. S. v. Thompson (3 CA), 483 F.2d 527, which is listed

in petitioners’ brief as a case which follows Berger.

For the alleged conflict, petitioners' brief cites Pfizer v. Lord

(CA 8), 456 F.2d 532. But the Pfizer opinion cites Berger and

follows its teaching. The Pfizer opinion states: “. . . although

the challenged judge may not pass upon the truth of the facts

alleged in the affidavit, he may decide whether the facts alleged

give fair support to the charge of bias or prejudice.”

Petitioners’ brief at page 18 refers to the concurring opinion

of Judge Gee as attacking Berger as “an outdated rule.” Peti

tioners do not tell this Court that Judge Gee’s quarrel with the

majority opinion was because it “reaffirms Berger’s antique

rule.” It is difficult to understand how petitioners can claim

that the opinion below is in conflict with Berger when it quotes

and cites Berger as its authority and when Judge Gee’s quarrel

with the majority opinion is its reaffirmance of Berger.

The cases which have construed Section 144 turn primarily

on the different fact situations alleged in the affidavits. But

in none of the cases cited by petitioners or examined by re

spondents has the factual basis for removal set out in the

affidavits been as weak as in the instant case, even though in

most of the cases cited by petitioners the courts held the af

fidavits insufficient.

— 14 —

CONCLUSION

This Court should not grant this petition for certiorari which

would involve piecemeal review of an interlocutory order while

this case is still pending before the Court of Appeals. The

decision below was correct, and the affidavit alleging personal

bias on the part of the trial judge was clearly insufficient to

give fair support to the charge of personal bias.

Respectfully submitted

WILLIAM H. MORROW

P. O. Box 671

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

CHAMP LYONS, JR.

57 Adams Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

TRUMAN HOBBS

P. O. Box 347

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

Attorneys for Respondents in Parrish

— 15

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the foregoing

upon the following attorneys for petitioners:

J U Blacksher

Crawford, Blacksher & Kennedy

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

U. W. dem on

Adams, Baker & dem on

2121 North Eighth Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Michael I. Sovern

435 W. 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Eric Schnapper

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

by mailing such copies, AIRMAIL postage prepaid, on this

the 27th day of February, 1976.

Truman Hobbs

Of Counsel for Respondents

( Parrish)