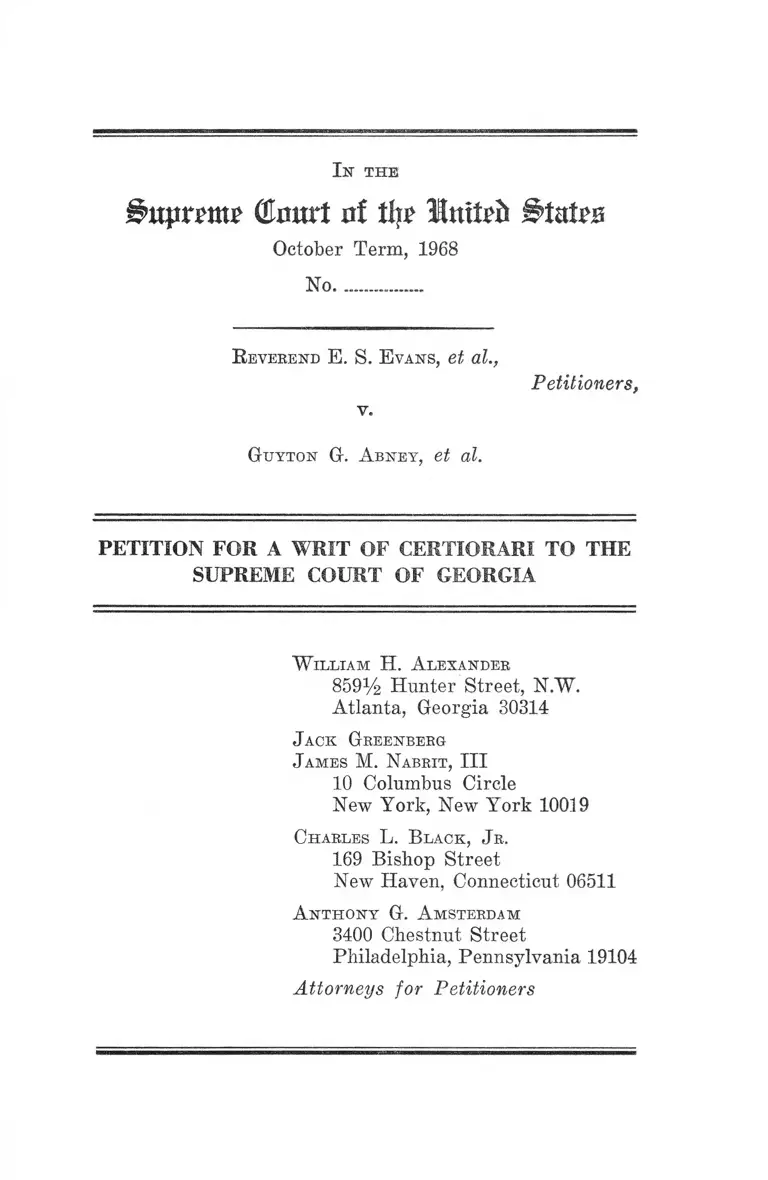

Evans v. Abney Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Abney Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia, 1968. bba71542-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/66794ec3-49fe-4627-bf6d-94ff09f4af30/evans-v-abney-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-georgia. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

(Burnt n f tip I n i t p i* §>Ut?s

October Term, 1968

No......... .

1 st t h e

R everend E. S. E vans, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Guyton G. A bney, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

W illiam H. A lexander

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Charles L. B lack, Jr.

169 Bishop Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06511

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions B elow ...................... 2

Jurisdiction ........... 2

Questions Presented ....................... 2

Statutes Involved.................... 3

Statement of the Case ........................... 5

The Will ........... 9

The City of Macon Acquires Baconsfield—1920 .... 12

City Administration and Financial Aid to the

Park and Federal Government Aid ................... 14

Baconsfield Clubhouse—Built by Federal Govern

ment ............................................................................ 18

Public Boads in the P a rk .......................................... 21

City-Built Swimming Pool and Bathhouses at

Baconsfield ................................................................ 21

City Operated Zoo ......................................... 24

Public School Playground ......................................... 24

City Leased Building.................................................. 25

City-Aided Recreation Facilities ............................. 25

Sale of Portion of Trust Property to State ....... 26

Tax Exemption............................................................ 26

PAGE

11

PAGE

Income Property................ ~............................-......... 26

Assets of the Estate .................................................. 27

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided 28

R easons fob Granting the W rit

I. The Importance of the Question in the Frame

work of This Case ............................................. —- 32

A. The Decision of the Georgia Court Frustrates

This Court’s Mandate in Evans v. Newton,

382 U.S. 296 (1966) ............................................ 32

B. The Decision of the Georgia Court Is Incon

sonant With Prior Decisions of This Court .... 33

C. Allowing the Georgia Court’s Decision to

Stand Will Seem to Open a Fertile Field for

Implementing Racial Discrimination, and Will

Therefore Encourage Schemes Aiming at

Such Discrimination ......... ........ ..................... 34

II. The Decree of the Court Below Is Hostile to the

Petitioners’ Right to Immunity From Racial

Discrimination .....-..................................................... 35

A. The Decree of the Georgia Court Imposes the

Drastic Penalty of Reverter on Compliance

With the Fourteenth Amendment, and in so

Doing Infringes Upon a Federal Interest De

clared and Created by the Constitution, at the

Same Time and by the Same Act Inflicting

Detriment on the Petitioners and Encourag

ing Racial Discrimination ............................... - 35

Ill

B. The Judgment That This Trust Has “Failed,”

Though Its Intended Beneficiaries May Still

Enjoy Its Benefits Just as Before, Can Best

Logically Only on the Proposition That, as

a Matter of Law, the Presence of Negroes

Spoils a Park for Whites, an Impermissible

Ground Under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Rejection of the Cy Pres Alternative

Must Rest on Similar Grounds ....................... 41

C. At Least Under the Highly Special Circum

stances of This Case, the Provision for Ra

cial Discrimination in Baconsfield Ought, as

a Matter of Federal Law, Under the Four

teenth Amendment, to Be Treated as Abso

lutely Void. If This Is Correct, Then Federal

Law Commands That This Trust Be Contin

ued and That the City Continue as Trustee,

for It Is Clear That Without the Racially

Discriminatory Language Georgia Law Com

pels That Result. Similarly, Federal Law

Commands That a Public Park “ Dedicated”

to the White Public Be “Dedicated” to the

PAGE

Negro Public as Well ....................................... 49

Conclusion .............................................................................. 58

A ppendix

Letter Opinion of Superior C ou rt.................................. la

Superior Court Order and Decree .................................. 7a

Opinion of Georgia Supreme Court ............................... 16a

Order of Georgia Supreme Court ................................... 25a

T a b l e o f C a s e s

page

Adams v. Bass, 18 Ga, 130 ............................................ 46, 47

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.8. 249 (1953) .............33,35,40

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....51, 55

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961) ................................................................................ 41

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Brown, 392 F.2d

120 (3rd Cir. 1968), cert. den. 391 U.S. 921 (1968).... 53

Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U.S. (6 Wall.) 35 (1867)....33, 35, 37

Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 69 (1938) ................... 39

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 (1966) ...........2,5,7,32,37,

40, 54

Evans v. Newton, 220 Ga. 280, 138 S.E.2d 573 (1964).... 2

Evans v. Newton, 221 Ga. 870. 148 S.E.2d 329 (1966).... 2, 7

Ford v. Thomas, 111 Ga. 493 .......................................... 46

Griffin v. County School Board [of Prince Edward

County], 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .................................... 33,51

Macon v. Franklin, 12 Ga. 239 .......................................... 53

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946) ...... .................. 52

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819) .......33, 35, 37

Pennsylvania v. Brown, 392 F.2d 120 (3rd Cir. 1968),

cert. den. 391 U.S. 921 (1968) ...................................... 33

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ..................... 51,55

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) .............. 33,36

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964) ..... ............... 36

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .........................33, 35

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) .... ...41,49

V

Sweet Briar Institute v. Button, 280 F. Supp. 312

(W.D. Va. 1967), rev’d per curiam, 387 U.S. 423,

decision on the merits, 280 F. Supp. 312 (1967) ....... 53

A uthorities

Statutes

PAGE

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) .............................................................. 2

Georgia Code §69-504 (1933) (Acts 1905)....3-4, 49-50, 52, 53,

54, 55, 57

Georgia Code, §69-505 (1933) (Acts, 1905) .................... 4

Georgia Code, §108-106(4) ................................................ 44

Georgia Code, §108-202 .........................................4,45,46,49

Georgia Code, §108-212...................................................... 8

Georgia Code, §113-815 ...................................... 4-5, 45,46, 49

Ik t h e

(H m trt o f % I m i p f t

October Term, 1968

No.................

R everend E. S. E vans, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Guyton G. A bney, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia entered in

the above-entitled case on December 5, 1968.1

1 Petitioners herein are Rev. E. S. Evans, Louis H. Wynn, Rev.

J. L. Key, Rev. Booker W. Chambers, William Randall and Rev.

Van J. Malone. The respondents, i.e., appellees in the court below,

are Guyton G. Abney, J. D. Crump, T. I. Denmark, Dr. W. G. Lee,

Successor Trustees under the Will of A. 0. Bacon; the City of

Macon, Georgia; the Citizens and Southern National Bank and

Willis B. Sparks, Jr., as Executors of the Will of A. 0. B. Sparks;

Willis B. Sparks, Jr. and M. Garten Sparks, Virginia Lamar

Sparks and M. Barton Sparks, Heirs at Law of A. 0. Bacon;

Charles Newton, Mrs. T. J. Stewart, Frank M. Willingham, Mrs.

Francis K. Hall, George P. Rankin, Jr., Mrs. Frederick W. Wil

liams, Mrs. Kenneth Dunwoody, A. M. Anderson, Mrs. W. E.

Pendleton, Jr., Mrs. R. A. McCord, Jr. and Mrs. Dan O’Callaghan,

Members of the Board of Managers under the Will of A. 0. Bacon;

Hugh M. Comer, Lawton Miller and B. L. Register, Successor

Trustees in lieu of the City of Macon.

2

Opinions Below

The letter opinion of the Judge of the Superior Court of

Bibb County dated December 1, 1967, and filed May 14,1968

(Appendix p. la, infra, R. 1007-1012) is unreported. The

opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia filed December 5,

1968, is reported at 165 S.E.2d 160 (Appendix p. 16a, infra-,

R. 1112-1126). Earlier proceedings in this same case are

reported sub nom. Evans v. Newton, 220 Ga. 280, 138 S.E.2d

573 (1964), reversed 382 U.S. 296 (1966), on remand, 221

Ga. 870, 148 S.E.2d 329 (1966).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of

Georgia was entered on December 5, 1968 (R. 1127; Ap

pendix p. 26a, infra). The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1257(3), the petitioners having

claimed the violation of their rights under the Constitution

of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether, in the absence of any reversionary clause in

the will leaving property in trust as a park, the imposition

by the Georgia court of a reversion to the heirs on a show

ing that Negroes have used, and must be allowed to use the

park, constitutes an infringement by state power on a

federal interest declared and created by the Constitution,

both by its immediate penalization of compliance with the

Fourteenth Amendment, and by its operation to discourage

desegregation. 2

2. Whether the holdings by the state court that this

trust has “ failed” and that cy pres cannot apply, rest on a

3

ground impermissible under the Fourteenth Amendment—

the ground that the presence of Negroes frustrates the en

joyment of the park by whites, even though the latter, the

intended beneficiaries, may use the park as freely as ever.

3. Whether the racially exclusory language in Senator

Bacon’s will must as a matter of federal law be treated as

null and void, both because the provisions were meant to

form and did actually form a part of the public law material

by which the City conducted its parks, and because federal

law, in commanding equality between the races, commanded

and by operation of law brought it about that this park,

since it was “dedicated in perpetuity” to whites, must also

be taken to be “dedicated in perpetuity” to Negroes.

Statutes Involved

1. This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves the following Georgia statutes:

a. Georgia Code Section 69-504:

Ga. Code §69-504 (1933) (Acts, 1905, p. 117):

Gifts for public parks or pleasure grounds.—Any

person may, by appropriate conveyance, devise, give,

or grant to any municipal corporation of this State, in

fee simple or in trust, or to other persons as trustees,

lands by said conveyance dedicated in perpetuity to

the public use as a park, pleasure ground, or for other

public purpose, and in said conveyance, by appropriate

limitations and conditions, provide that the use of

said park, pleasure ground, or other property so

conveyed to said municipality shall be limited to the

white race only, or to white women and children only,

4

or to the colored race only, or to colored women and

children only, or to any other race, or to the women

and children of any other race only, that may be

designated by said devisor or grantor; and any person

may also, by such conveyance, devise, give, or grant

in perpetuity to such corporations or persons other

property, real or personal, for the development, im

provement, and maintenance of said property.

h. Georgia Code Section 69-505:

Ga. Code §69-505 (1933) (Acts, 1905, pp. 117, 118):

Municipality authorized to accept.—Any municipal

corporation, or other persons natural or artificial, as

trustees, to whom such devise, gift, or grant is made,

may accept the same in behalf of and for the benefit

of the class of persons named in the conveyance, and

for their exclusive use and enjoyment; with the right

to the municipality or trustees to improve, embellish,

and ornament the land so granted as a public park,

or for other public use as herein specified, and every

municipal corporation to which such conveyance shall

he made shall have power, by appropriate police

provision, to protect the class of persons for whose

benefit the devise or grant is made, in the exclusive

used (sic) and enjoyment thereof.

c. Georgia Code Section 108-202:

Cy pres.—When a valid charitable bequest is in

capable for some reason of execution in the exact man

ner provided by the testator, donor, or founder, a

court of equity will carry it into effect in such a way

as will as nearly as possible effectuate his intention.

d. Georgia Code Section 113-815:

Charitable devise or bequest. Cy pres doctrine, ap

plication of.—A devise or bequest to a charitable use

5

will be sustained and carried out in this State; and in

all cases where there is a general intention manifested

by the testator to effect a certain purpose, and the

particular mode in which he directs it to be done shall

fail from any cause, a court of chancery may, by ap

proximation, effectuate the purpose in a manner most

similar to that indicated by the testator.

Statement of the Case

Petitioners are Negro citizens in Macon, Georgia who

have sought in this extended litigation to desegregate

Baconsfield Park, a previously all-white municipal park

left to the City of Macon by the will of the late United

States Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon. The case was

reviewed by this Court once before in Evans v. Neivton,

382 U.S. 296 (1966). The present petition seeks a review

of a ruling by the Georgia courts that as a consequence of

this Court’s holding that the Fourteenth Amendment for

bids the exclusion of Negro citizens from the park, Bacon’s

trust fails and the park and other trust property is forfeited

by the City and reverts to the heirs of Senator Bacon.

The early course of the lawsuit, which was begun in the

Superior Court of Bibb County, Georgia on May 4, 1963,

is briefly summarized in the following excerpt from the

opinion by Mr. Justice Douglas for the Court, Evans v.

Newton, 382 U.S. 296, 297-298:

In 1911 United States Senator Augustus 0. Bacon

executed a will that devised to the Mayor and Council

of the City of Macon, Georgia, a tract of land which,

after the death of the Senator’s wife and daughters, was

to be used as “a park and pleasure ground” for white

people only, the Senator stating in the will that while

he had only the kindest feeling for the Negroes he was

6

of the opinion that “ in their social relations the two

races (white and negro) should be forever separate.”

The will provided that the park should be under the con

trol of a Board of Managers of seven persons, all of

whom were to be white. The city kept the park segre

gated for some years but in time let Negroes use it,

taking the position that the park was a public facility

which it could not constitutionally manage and maintain

on a segregated basis.

Thereupon, individual members of the Board of Man

agers of the Park brought this suit in a state court

against the City of Macon and the trustees of certain

residuary beneficiaries of Senator Bacon’s estate, ask

ing that the city be removed as trustee and that the

court appoint new trustees, to whom title to the park

would be transferred. The city answered, alleging it

could not legally enforce racial segregation in the park.

The other defendants admitted the allegation and re

quested that the city be removed as trustee.

Several Negro citizens of Macon intervened, alleging

that the racial limitation was contrary to the laws and

public policy of the United States, and asking that the

court refuse to appoint private trustees. Thereafter

the city resigned as trustee and amended its answer

accordingly. Moreover, other heirs of Senator Bacon

intervened and they and the defendants other than the

city asked for reversion of the trust property to the

Bacon estate in the event that the prayer of the peti

tion were denied.

The Georgia court accepted the resignation of the

city as trustee and appointed three individuals as new

trustees, finding it unnecessary to pass on the other

claims of the heirs. On appeal by the Negro inter-

venors, the Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed, hold

ing that Senator Bacon had the right to give and be

7

queath his property to a limited class, that charitable

trusts are subject to supervision of a court of equity,

and that the power to appoint new trustees so that the

purpose of the trust would not fail was clear. 220 Ga.

280, 138 S. E. 2d 573.

This Court, in reversing the judgment of the Georgia

Supreme Court, ruled that the park was “ a public institu

tion subject to the command of the Fourteenth Amendment,

regardless of who now has title under state law” (382 U.S.

at 302).

Immediately after this Court’s decision, the Supreme

Court of Georgia delivered a second opinion setting forth

the view that the purpose for which the Baconsfield Trust

was created had become impossible to accomplish and had

terminated. Evans v. Newton, 221 Ga. 870, 148 S.E.2d 329

(1966). However, the judgment did not direct that the

Superior Court on remand enter any particular order, but

merely ruled that the court should pass on contentions of

the parties not previously decided, and said that the “judg

ment of the Supreme Court of the United States is made

the judgment of this Court” (148 S.E.2d at 331).

On remand in the Superior Court of Bibb County, a Mo

tion for Summary Judgment (R. 136-141) (which was sub

sequently amended and supplemented by three additional

pleadings (R. 622; 930; 939) was filed by Guyton G. Abney,

et al. as Successor Trustees under the Last Will and Testa

ment of Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon. The motion

asked that the court rule that Senator Bacon’s trust had

become unenforceable, and that the Baconsfield property

had reverted to movants as successor trustees under Item

6th of Bacon’s will, and to certain named heirs of Senator

Bacon (R. 141). The motion was opposed by petitioners,

Rev. E. S. Evans, et al., the Negro citizens of Macon who

8

had earlier intervened seeking the racially nondiscrimina-

tory operation of Baconsfield Park, by the filing of a re

sponse (R. 157-160) and four supplemental responses to

the summary judgment motion (R. 371-374, 695-706, 917-

918, 971). Petitioners filed numerous exhibits, as well as

depositions, affidavits, answers to interrogatories and

stipulations setting forth additional facts. Petitioners ob

jected on federal constitutional grounds based on the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment, as well as on state law grounds, to the relief

sought by the successor trustees and heirs. The heirs also

filed several affidavits and exhibits supplementing the fac

tual record. None of the other parties to the case, including

the City of Macon, the Trustees of Baconsfield named by

the court’s order of March 10, 1964, or the members of the

Board of Managers of Baconsfield (who initiated this law

suit) either opposed the granting of the relief requested in

the Motion for Summary Judgment, or offered any evidence.

The court heard oral arguments on June 29, 1967, and

granted the parties time to file further documentary evi

dence, which was filed.

At the hearing the petitioners, Evans, et al., suggested

that the Attorney General of Georgia should be made a

party to the case. By order dated July 21, 1967, the Attor

ney General was made a party pursuant to Georgia Code

Section 108-212 (Acts 1952, pp. 121, 122; 1962, p. 527). The

Attorney General of Georgia filed a “Response” opposing

the relief requested by the heirs and supporting the posi

tion of the intervenors E. S. Evans, et al. that the doctrine

of cy pres should be applied to save the trust (R. 975-988).

The Superior Court, granted the relief requested in the

successor trustees’ and heirs’ Motion for Summary Judg

ment, ruling that the trust established by Senator Bacon

failed immediately upon this Court’s ruling in January

9

1966, that the City of Macon was dismissed from the case,

and that the trust assets reverted to the successor trustees

and heirs (E. 999-1006). In addition, the court ruled that

the doctrine of cy pres was not applicable, that there was

no dedication to the public, that the heirs were not estopped

and that no federal constitutional rights of intervenors

were violated by the reversion of the trust assets (id.). The

Superior Court order and decree was entered May 14, 1968

(id.).

Petitioners duly appealed to the Supreme Court of

Georgia, which filed an opinion December 5, 1968, affirming

the decree of the Bibb Superior Court, and rejected peti

tioners’ federal constitutional claims (R. 1112-1126). The

court below stayed its remittitur and further proceedings

pending the disposition of a timely petition for certiorari

in this Court (R. 1130).

While the record filed with this ease includes the entire

record of proceedings before this Court on the prior peti

tion, it also includes a good deal of additional factual data

and evidence presented to the Superior Court on remand.

The evidence develops the history of Baconsfield Park, and

shows in great detail the substantial governmental invest

ment, including the expenditure of both city and federal

government funds, in establishing, improving and maintain

ing Baconsfield Park.

The Will

Senator A. 0. Bacon provided in Item 9th of his Will

(R. 16-34), signed in 1911 and probated in 1914, for the

disposition of his farm called Baconsfield. He left the prop

erty in trust for the use of his wife and daughters during

their lives (R. 22-23) and provided that after their deaths:

. . . it is my will that all right, title and interest in

and to said property hereinbefore described and

10

bounded, both legal and equitable, including all re

mainders and reversions and every estate in the same

of whatsoever kind, shall thereupon vest in and belong

to the Mayor and Council of the City of Macon, and to

their successors forever, in trust for the sole, perpetual

and unending, use, benefit and enjoyment of the white

women, white girls, white boys and white children of

the City of Macon to be by them forever used and en

joyed as a park and pleasure ground, subject to the

restrictions, government, management, rules and con

trol of the Board of Managers hereinafter provided

for: the said property under no circumstances, or by

any authority whatsoever, to be sold or alienated or

disposed of, or at any time for any reason devoted to

any other purpose or use excepting so far as herein

specifically authorized. (R. 23)

The will provided for a seven member all-white Board of

Managers to be chosen by the Mayor and Council of Macon

(R. 23) and for the Board to have power to regulate the

park, including discretion to admit men (R. 24). Senator

Bacon directed that a portion of the property be used to

gain income for the upkeep of the park (R. 24). He directed

that “ in no event and under no circumstances” should either

the park property or the income-producing area be sold or

otherwise alienated, and specified that except for the desig

nated income-producing area the property “ shall forever,

and in perpetuity be held for the sole uses, benefits and

enjoyments as herein directed and specified” (R. 24). The

will stated Senator Bacon’s belief that Negroes and whites

should have separate recreation grounds (R. 25). It also

stated his wish that the property be “preserved forever for

the uses and purposes” indicated in the will, and that it be

perpetually known as “Baconsfield” (R. 25). It provided

that the trustees had no power to sell or dispose of the prop

11

erty “under any circumstances and upon any account what

soever, and all such power to make such sale or alienation

is hereby expressly denied to them, and to all others”

(R. 26).

Item 10th of Senator Bacon’s will bequeathed bonds,

valued at $10,000, to the City of Macon with directions that

the income be used for the preservation, maintenance and

improvement of Baconsfield (R. 26). The will said that if

the City was without legal power under the city charter to

hold the funds in trust, the City should select a successor

trustee (E. 27). Bacon gave a similar direction for the

City to select a successor trustee “ if for any reason it

should be held that the Mayor and Council of the City of

Macon have not the legal power under their charter to hold

in trust for the purposes specified the property designated

for said park and pleasure ground . . .” (R. 27-28).

In a 1913 codicil, Senator Bacon noted that one of his

daughters, Mrs. Augusta Curry, had predeceased him, and

provided that her children should stand in her place in the

disposition of the property, except that with respect to

Baconsfield their interest would cease upon the death of

his wife and his other daughter (E. 32-33). Item 3rd of

the codicil provided, inter alia:

To prevent possibility of misconstruction I hereby pre

scribe and declare that all interest of the said children

of my said daughter Augusta in the property specified

in Item 9 of my said Will and in the rents, issues and

profits thereof, shall cease, end and determine upon

the death of my wife Virginia Lamar Bacon and of my

daughter Mary Louise Bacon Sparks (E. 33).

In Item 4th of the codicil, it was provided that Custis

Nottingham, one of the trustees and executors under the

will, and his family, could occupy a house on Baconsfield

12

rent-free until the full expiration of the trust for which he

was appointed (R. 33).

The City of Macon Acquires Baconsfield— 1920

The City of Macon obtained possession of Baconsfield in

February 1920, many years before the death of Senator

Bacon’s surviving daughter, by virtue of an agreement

between the City and the trustees under the will, which was

entered into with the written assent of all of Senator

Bacon’s heirs. The agreement is set forth in the Macon

City Council Minutes of February 3, 1920 (Intervenors’

Exhibit 0 ; R. 710-712). Under the agreement between the

City and the trustees, which recites that it was executed with

the signed assent of all legatees and beneficiaries of the

Bacon estate, the trustees conveyed Baconsfield to the City

by deed, and also conveyed to the City to be covered into

the City treasury the bonds and accumulated interest be

queathed by Item 10th of the will (Id.). The deed of Bacons

field to the City appears in the record as Intervenors’ Ex

hibit F ; it was executed February 4, 1920, and recorded

February 10, 1920 (R. 650-652). In the agreement the City

agreed to pay the trustees the sum of $1,665 annually dur

ing the life of Senator Bacon’s daughter, Mrs. Sparks

(R. 710-711). The City also agreed that it would appropri

ate 5% of the sum of the value of the bonds and accumulated

interest each year, or $650 annually, for the improvement

of Baconsfield Park (Id.). The City agreed not to charge

any taxes or other assessments of any kind against the

property (Id.). At the same time the City agreed with

Custis Nottingham that he would terminate his occupancy

of a house in Baconsfield in consideration of a cash payment

of $5,100 from the City of Macon (Exhibit O R. 710).

Nottingham’s Quit Claim Deed to the City is Intervenors’

Exhibit G (R. 653-654).

13

The City of Macon paid $5,100 to Custis Nottingham in

consideration of his deed of his interest in Baconsfield

(E. 711). The City of Macon paid the trustees under the

will an annuity each year during the life of Mrs. Mary

Louise Bacon Sparks. The Baconsfield annuity payments of

$1,665 per year were regularly included in the Macon City

budgets. (See, for example, budgets for the years 1939 and

1940, Intervenors’ Exhibits T and U; E. 721, 722). Mrs.

Sparks lived until May 31, 1944 (Intervenors’ Exhibit W ;

E. 919). Accordingly, there were 25 payments of $1,665

from February 1920 through February 1944, and the City

of Macon thus paid a total of $41,625 to the trustees under

Bacon’s will in order to acquire Baconsfield.

The Macon City Council Minutes of February 17, 1920

(Intervenors’ Exhibit P ; E. 713-714), reflect the fact that

the City had taken over Baconsfield Park; that the council

elected the first Board of Managers; that the Mayor of

Macon, G. Glenn Toole, was elected to the Board of Mana

gers; and that this election of the Mayor was requested

by the trustees under Bacon’s will, Messrs. Jordan and

Nottingham, who wrote a letter to the Mayor stating:

In turning over to the City of Macon the park devised

to it by Senator Bacon, permit us to express the hope

that this Park will mean all to the white citizens of

Macon that Senator Bacon wished it to mean.

The place is one of great natural beauty, but it could

easily be marred by haphazard work. We are sure

that before anything material is done to this property

that you, the City Council, and the Commission ap

pointed by it will have a well defined and permanent

plan of improvement in view.

We believe that it is of the utmost importance that

you be a member of this Commission, and wish here

to voice the hope that you will not decline such service

14

from any false modesty. It will greatly expedite the

people’s enjoyment of this property if the Commission

is headed by the head of our City Government. Dif

ferences in opinion and change of plans will be thus

avoided, and the money essential to the improvement

of this property will he expended by the one charged

with raising it. (E. 713-714; emphasis added).

Mr. Toole, who was Mayor of Macon from 1918-1921 and

from 1929-1933 (Heirs and Trustees Exhibit E ; R. 931),

remained a member of the Board of Managers until 1945.

(Intervenors’ Exhibit B, Baconsfield Minutes of May 30,

1945, and November 1, 1945; R. 557, 560, 563-564).

City Administration and Financial Aid to the Park

and Federal Government Aid

Mr. T. Cleveland James was Superintendent of Parks of

the City of Macon from 1915 to the time of his Deposition

in April 1967 (R. 285-286). He developed most of Macon’s

parks, including Baconsfield and exercised general super

vision over Baconsfield for many years. He testified that

Baconsfield was a “wilderness” with “undergrowth every

where” and no facilities at the time the Mayor directed him

to take charge of the park (R. 278; 307). Supt. James ini

tially developed Baconsfield Park using workmen who were

paid by the federal Works Progress Administration, an

agency of the United States. The W.P.A. men were working

at Baconsfield under his supervision for a period he esti

mated as a year or more (R. 283, 307). The federally paid

workmen cleared the underbrush, cleared foot paths, built

footbridges, dug ponds, built benches, planted trees and

flowers and generally performed landscaping work in

Baconsfield Park (R. 278-284, 287). The WhP.A. workers

did similar work in other city parks under the supervision

of the City Park Superintendent (R. 298). Mr. James’

15

testimony is supplemented and corroborated by W.P.A. rec

ords from the archives of the United States (Intervenors’

Exhibit E ; R. 595-649) which reflect that Works Progress

Administration Work Project No. 244 involved landscaping

city parks in Macon, Georgia under the supervision of the

City Park Superintendent. The W.P.A. records indicate

that W.P.A. Project No. 244 was approved August 7, 1935;

that the federal government paid $120,032.35 for 469.079

man hours of work; and that the sponsor (City of Macon)

paid $17,923.43 for work on the project (R. 599), The

W.P.A. records do not indicate how much of the labor was

at Baconsfield and how much was at other city parks. But,

Mr. James’ testimony indicates that W.P.A. work at Bacons

field was very extensive (R. 307):

Q. Will you describe for us very briefly what you meant

when you said Baconsfield Park was a wilderness

when you first went out there?

A. Well, there wasn’t nothing there but just undergrowth

everywhere, one road through there and that’s all, one

paved road.

Q. And no facilities out there; is that correct?

A. No.

Q. And how long did it take you to turn it into a usable

park?

A. Oh, about 6 or 8 months, probably a year.

Q. I see, and you used employees fairly regularly during

all of that year?

A. Yes.

Q. Every day?

A. Well, wTe had the PW A labor, trying to get me to give

them something to do, you know, and I worked them

over there.

Q. You say you used the PW A employees for maybe a

year?

A. I expect I did, yes, that is what I did my work with.

16

The minutes of the Baconsfield Board of Managers meet

ing held March 30, 1936 (Intervenors’ Exhibit B ; R. 507-

509), indicate that considerable development, landscaping

and planting had been done in the park during the preced

ing 12 months. No earlier minutes of the Board are avail

able (R. 507). However, the Board minutes indicate an

extensive pattern of governmental involvement in the

maintenance of the park from 1936 until the City resigned

as trustee of the park in 1964. (The minutes from 1936-

1945 are Exhibit B, R. 506-565. The minutes from 1945-1967

are Exhibit A, R. 376-505). The City’s involvement in the

operation of the park was manifested in a great number of

ways. For example, for a twelve year period from 1936 to

1948, all but one of twenty-one meetings of the Board of

Managers of Baconsfield took place in the Mayor’s office or

elsewhere in Macon’s City Hall. During the same period

the Mayor of Macon attended 16 of the 21 meetings. (See,

generally, Intervenors’ Exhibits A and B supra). The min

utes reflect that over an extended period of years the Board

of Managers frequently requested and obtained assistance

from the City of Macon in developing and improving the

park. On occasion the minutes of the Board of Managers

refer to Baconsfield variously as a “municipal park” (Inter

venors’ Exhibit A, Minutes of 5/6/53; R. 403) and to

“ Baconsfield and the other public parks of the City of

Macon” (Intervenors’ Exhibit A, resolution following min

utes of 11/1/45; R. 564).

The deposition of Park Superintendent James and the

Board of Managers’ minutes indicate positively and con

clusively that Baconsfield Park was maintained and oper

ated as an integral part of the City park system from the

time the park was first developed until the City resigned

as trustee in 1964. Park department employees under Mr.

James’ supervision maintained Baconsfield just as they did

all of the other city parks (R. 276, 289-290, 306). Mr. James

17

estimated that the City spent about $5,000 for flowers and

plants in Baconsfield during the years he worked there,

and additional amounts were spent by the Board of Mana

gers for gardening supplies (R. 295-296). In 1938, the

United States government gave to the park 144 bamboo

plants, representing six different varieties of bamboo (In-

tervenors’ Exhibit B, Minutes of 6/28/38; R. 525). Mr.

James regularly assigned men from the city Park Depart

ment to work in Baconsfield as the need arose (R. 276).

City workers did all the general maintenance work in the

park until 1964 (R. 278). For a period of years, Mr. James,

the City Superintendent of Parks, lived in Baconsfield

Park, occupying a home rent free. (Minutes of 10/16/47;

Exhibit A ; R. 391). The substantial value of the city’s con

tribution of labor for upkeep of the park is demonstrated

by the increase in the board’s maintenance expenditures

after the City resigned as trustee of the park in 1964

(R. 332-333). The amounts spent by the Board of Managers

for maintenance in the years 1960-1966 were as follows:

1960 — $1,307.20

1961 — $1,645.72

1962 — $1,995.57

1963 — $1,465.20

1964 — $6,545.78

1965 — $7,073.80

1966 — $6,675.89

(Board of Managers’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 9; R.

174.) The Chairman of the Board of Managers agreed that

the cost increase in 1964 and thereafter was attributable to

the fact that the City withdrew its services, and it became

necessary for the board to pay for services which had pre

viously been furnished by the City Parks Department

(R. 332-333). The Mayor of Macon testified that he ordered

all city employees to stop working at Baconsfield after the

City resigned as trustee in 1964.

18

Bacons field Clubhouse— Built by Federal Government

There is a two story brick building known as the Bacons-

field Clubhouse located in the park. The clubhouse was built

in 1939 by the Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.),

an agency of the United States (Interveners’ Exhibits J

(E. 708-709), K (R. 724-841), L (R. 842-846), M (R. 847-

910), N (R. 911-913 and R (R. 718-719)). The clubhouse

construction project Avas sponsored by the City of Macon

acting in conjunction with a private group known as the

Women’s Clubhouse Commission. In its application for

federal funds for this project, the City of Macon, by its

Mayor and Treasurer, executed numerous documents con

stituting agreements, assurances, certificates, representa

tions and contracts which are contained within the W.P.A.

records (Intervenors’ Exhibits K (R. 724-841) and M (R.

847-910)). The City in several documents represented to

the United States that the City was the sole owner of the

Baconsfield Park property (R. 774, 788-789), that the City’s

ownership was “perpetual,” that there were no reversion

ary or revocation clauses in the ownership documents (R.

789), that the property was not private property (id.), and

certified that the proposed clubhouse project was “ for the

use or benefit of the public” (R. 796, 808). Federal funds

totaling $16,512.80 were expended to construct the club

house (see Intervenors’ Exhibits L (R. 842-846) and N (R.

911-913)). The city officials signed documents indicating

that the sponsor’s (City’s) share of construction costs would

be financed out of the “ regular tax fund with the assistance

of the Women’s Club of Macon” (Intervenors’ Exhibit K ;

R. 774). The Women’s Club had agreed to contribute $3,000

(Intervenors’ Exhibit R ; R. 718). The sponsor’s (City’s)

share of the construction costs finally amounted to $8,376.91

(R. 846, 913). The total costs of the clubhouse, including

the federal contributions ($16,512.80; R. 845, 912) was

$24,889.71 (Intervenors’ Exhibits L and N).

19

In a sworn certificate executed under oatli by the Mayor

and Treasurer of the City of Macon on October 14, 1938,

quoted in full below, the City promised that there would be

no discrimination against any group or individual in the

use of the clubhouse or the property upon which it was lo

cated, and that the City did not intend to lease, sell, donate

or otherwise convey title or release jurisdiction of the prop

erty during the useful life of the improvements built with

federal funds. The certificate contained in Intervenors’

Exhibit K, reads as follows (E. 822):

With reference to Works Progress Administration

Project Application State Serial No. 6586, this is to

certify that the proposed building referred to in plans,

specifications and other data submitted to support the

project applications, as “Baeonsfield Club House” will,

upon completion, be used as a community club house

for the general use and benefit of the public at large,

without discrimination against any individual, group

of individuals, association, organization, club or other

party or parties who may desire the use of the build

ing and the property upon which the building is lo

cated.

It is further certified that the City of Macon, as project

sponsor and owner of the property upon which the

building is to be constructed, does not intend to lease,

sell, donate or otherwise convey title or release juris

diction of the property together with improvements

made thereon, during the useful life of the improve

ments placed thereon through the aid of W. P. A.

funds.

It is further certified that the City of Macon, as project

sponsor, will be responsible to see that the property

together with the improvements made thereon will be

maintained for the general use and benefit of the pub-

20

lie, and will not be used for the profit or benefit of

any one individual or specific group or organization;

and the management of the property, together with

improvements made thereon, will at all times be sub

ject to the approval of the designated city official or

officials of the City of Macon, who will be responsible

to see that the foregoing certification is adhered to.

/ s / Charles L. Bowden

Mayor, City of Macon,

Georgia

/ s / Frank Branan

Treasurer, City of Macon,

Georgia

Another similar certificate or agreement containing as

surances that the property “will not be leased, sold, donated

or otherwise disposed of to any private individual or cor

poration, or to a quasi-public organization during the oper

ation of the project” and would be “maintained by the

Women’s Club and operated for the benefit of the general

public,” was executed September 7, 1938, by the Mayor

and Treasurer of the City of Macon and by the President

and Treasurer of the Women’s Club House Commission

(Intervenors’ Exhibit M at R. 889).

The Women’s Club continues to occupy the clubhouse in

Baconsfield Park, using the building free of charge and

without paying rent either to the City or to the Board of

Managers. The Women’s Club charges fees for various or

ganizations which use the building for meetings, but none

of these funds go to the City or to the Board of Managers

(R. 212-219, 312-315, 328-331). Mayor Merritt of Macon

testified that he has attended meetings at the Clubhouse of

such organizations as the Georgia Legal Secretaries Asso

ciation, the Georgia Milk Dealers Association, and several

21

other local associations of various types (R. 216, 218).

The minutes of the Board of Managers of Baconsfield in

dicate that the Board permitted the Highland Hill Baptist

Church to use the Baconsfield Clubhouse as the temporary

meeting place for the church during the construction of

the church. The Board voted this permission for the

church to use the Clubhouse at its meeting of June 25,

1953, notwithstanding its attorney’s advice that this use

was not permitted by Senator Bacon’s will (Exhibit A,

Minutes of 6/25/53; R. 404-407). A. letter from the Chair

man of the Board of Deacons of Highland Hill Baptist

Church thanking the Board for the use of the Clubhouse

as a meeting place for the church was read at the Bacons

field Board meeting of May 17, 1955 (Exhibit A, Minutes

of 5/17/55 ;B . 424).

Public Roads in the Park

Certain roads running through Baconsfield Park were

paved and developed by the City (R. 224-227; 279-280; see

also, Intervenors’ Exhibit A, Minutes of 5/17/55 (R. 425-

426). On several occasions the Board of Managers resolved

to seek federal funds for the paving of roadways in the

park, but the record does not indicate whether any federal

highway funds were actually obtained (see Intervenors’

Exhibit B, Minutes of 3/30/36 (R. 508-509); 6/28/38 (R.

526); and 10/12/38 (R. 527)). On one occasion the City

paid the Board of Managers the sum of $1,000 as “partial

reimbursement from City of Macon foi paving in Bacons

field.” (Intervenors’ Exhibit A, financial statement fol

lowing Minutes of 10/16/47; R. 393).

City-Built Swimming Pool and Bathhouses at Baconsfield

As early as 1936, the Board of Managers of Baconsfield

began discussing the desirability of constructing a swim

ming pool in the park, and the discussion of government

22

aid for a pool continued for years (Intervenors’ Exhibit

B, Minutes of 6/29/36 (R. 512), 7/30/36 (R. 514), 12/7/36

(R. 517), 12/14/44 (R. 549), 5/30/45 (R. 551-557)). Fi

nally, on June 3, 1947, the Chairman of the Board of Man

agers met with the Mayor and several aldermen of Macon

and “ strongly urged” that the City appropriate $100,000

to build a pool in Baconsfield. (See Intervenors’ Exhibit

A, Minutes of 6/3/47; R. 382-383.) The City agreed to

this suggestion and on July 22, 1947, resolved to deliver

the sum of One Hundred Thousand Dollars to the Board

of Managers of Baconsfield to he used by the Board for

the construction of a swimming pool. (Intervenors’ Ex

hibit I ; R. 686; see also, Intervenors’ Exhibit V ; R. 723.)

Subsequently, the City appropriated an additional Forty

Thousand Dollars on December 23, 1947 to the Recreation

Department to construct bathhouses at Baconsfield pool

(Intervenors’ Exhibit I ; R. 686). The Baconsfield minutes

indicate that the Board of Managers accepted the $100,000

grant and designated the Chairman and Secretary of the

Board of Managers and the Chairmen of the City Council’s

Finance and Recreation committees to act as agents to con

struct the pool and disburse the funds from a special swim

ming pool account. (Intervenors’ Exhibit A, Minutes of

8/4/47; R. 386-388.) A large community swimming pool

and adjacent buildings were constructed in 1948 on a por

tion of the Baconsfield land designated in Bacon’s will as

income-producing property. After the pool was constructed

the Board of Managers and the City entered into a contract

by which the pool was leased by the Board to the City for

a two year term, to be automatically renewed for successive

two year terms unless either party terminated the lease

or the City breached its covenants (Heirs’ Exhibit D; R.

678-683). The City agreed to operate the pool:

. . . as a part of the pleasure and recreational facil

ities of Baconsfield, for the enjoyment and benefit of

23

the beneficiaries of the trust for Baconsfield, as set

up and established in the said last will and testament

of the said A. 0. Bacon, deceased, and also for other

persons who are or may be admitted to Baconsfield

(R. 680).

The City agreed to bear any losses in connection with the

pool operation, and to share any profits with the Board.

No payments to the Board were made under this provision

(Heirs’ Exhibit H and attached letter; R. 941-945). The

City made additional capital expenditures at the pool and

related facilities over the years for improvements, includ

ing the following amounts (Heirs’ Exhibit H ; R. 944):

1948 $ 4,999.57

1960 6,079.21

1962 6,360.55

$17,439.33

The sum of $1,084.93, which remained in the old swim

ming pool account was transferred to the regular account

of the Board of Managers in 1959. (Intervenors’ Exhibit

A, Minutes of 5/8/59; R. 451, and financial statement fol

lowing Minutes of 10/29/59; R. 456.)

The pool was finally closed and the lease cancelled in

1964 in order to avoid racial desegregation as required

by the Fourteenth Amendment. In April 1963, following

attempts by Negro groups to integrate the park, the Board

resolved to cancel its contract with the City relating to the

pool and to attempt to negotiate a contract with a private

party for operation of the pool (Minutes of 4/9/63;

R. 483-484). At the same time, the Board directed its at

torneys to commence this lawsuit to remove the City as

trustee (Id.). The swimming pool contract was finally can

celled in May 1964. The Board’s attorney wrote a letter

24

to Mayor Merritt dated May 22, 1964 (Intervenors’ Exhibit

X ; R. 921-923) stating that it was cancelling the pool lease

because of the City’s inability to enforce racial segrega

tion at the pool. The Mayor replied by letter dated May 28,

1964 (Intervenors’ Exhibit Y ; R. 924), acquiescing in the

termination and relinquishing control of the pool to the

Board of Managers. The swimming pool has remained

closed since that time, and has not been maintained or

kept in repair since 1964. Xearby highway construction

which interfered with the pool area during a period of time

has now been completed, but the pool remains closed.

City Operated Zoo

The City established a zoo in Baconsfield Park, with

caged animals, including monkeys, a bear, ducks, rabbits,

a raccoon, a few deer, and a few peafowl and pheasants.

(Answer of Board to Interrogatory No. 2; R. 172-173.)

Mayor Merritt stated that the zoo included 40 or 50

monkeys (R. 203). The zoo was closed and all the animals

and cages removed after the City resigned as trustee in

1964. While the zoo was in operation the City employed a

full-time employee at Baconsfield to take care of the animals

(R. 205-206, 211, 290). The Public Works Department of

Macon dismantled the zoo (R. 208).

Public School Playground

A playground in the Baconsfield Park is regularly used

as the school playground for a nearby public school oper

ated by the Bibb County Public School System. The school

is Alexander School Number 3, a previously all white ele

mentary school, which it was anticipated would be attended

by a small number of Negro pupils living in the neighbor

hood under the school district’s desegregation plan. (In

tervenors’ Exhibit W, Stipulation No. 2; R. 919.) The

school personnel supervise the children in using the play

ground in Baconsfield (R. 235-236, 241-242). The Bibb

25

County Board of Education was responsible for having the

playground installed, including basketball courts (R. 244,

262). Prior to 1964, the City Recreation Department had

an employee assigned to the playground at Baconslield to

supervise the children. The City spent an average of

$1,180.70 per year to employ someone at the playground

prior to February 1964 (R. 237-241).

City Leased Building

From 1954 until the present time, the City has leased a

building referred to as the Open Air School from the

Board of Managers and paid the Board a rental of $300

per annum. (Exhibit A, Minutes of 6/24/54; R. 413;

R. 246-251.) This is a one story brick building located in

the portion of the Baconsfield property set aside for raising

revenue (R. 246). The City in turn makes the building

available, free of charge, to the Macon Young Women’s

Civic Club for the activities of the “ Happy Hour Club,” an

organization of elderly people (R. 248-249). The building

was previously occupied by the Board of Education rent

free (Intervenors’ Exhibit B, Minutes of 7/10/41; R. 541).

City-Aided Recreation Facilities

A Little League baseball field located in the park was

constructed in part with the aid of the City which dumped

100 to 200 truck loads of dirt in a low area of Baconsfield

where the field is now located (R. 219-222). The financial

records of the Board indicated that it made a “part pay

ment” to the City for filling in the play area in the amount

of $3,500. (Exhibit A, financial statement following Mi

nutes of 12/18/56; R. 437.) The minutes do not indicate

any subsequent payments.

Several tennis courts are maintained in the park. The

City of Macon assisted in installing lights at the tennis

courts to permit play at night. (R. 228-229; Minutes of

7/24/62; R. 475.) In 1964. the Board of Managers granted

26

to the Macon Tennis Club, a private club, permission for

the club to regulate play at the Baconsfield Tennis Courts

according to the rules of the club, and permission to main

tain the tennis courts. (Intervenors’ Exhibit A, Minutes

of 4/10/64; R. 492.)

Sale of Portion of Trust Property to State

During World War II, when informed that the War De

partment wanted a strip of land to open a roadway, the

Board and the City sold a strip of land from the area of

Baconsfield devised by Senator Bacon as income-producing

property to the State Highway Board of Georgia. (See

the deed and attached resolutions, Intervenors’ Exhibit H ;

R. 655-660.) The Board of Managers received a check in

the amount of $1,500 from the City of Macon in this trans

action. (Intervenors’ Exhibit B, Minutes of 3/3/42; R. 542-

543, and financial statement following Minutes of 12/15/44;

R. 550.)

Tax Exemption

The Board of Managers has never paid any taxes, fed

eral, state, or local, on the Baconsfield property or on any

of the income they have received. The property has always

been treated as exempt from taxes under Georgia laws.

(See Financial Statements in Intervenors’ Exhibits A and

B, passim.)

Income Property

The income-producing area of the trust property now

includes a shopping center with several business, includ

ing a filling station, pharmacy, ice cream store, etc. The

rental income of the Board o f Managers during calendar

year 1966 was $7,058.37. (Computed from Intervenors’

Exhibit C; R. 569-592.) The rental income received during

the period April 1, 1963, to March 31, 1964, was $5,225.04

(R. 346). During the years the Board also has received

payment for various types of utility easements on the

27

property. In 1958, the Board received $3,500 from the City

Board of Water Commissioners for a sewer easement. (In

terveners’ Exhibit A, financial statement following Minutes

of 5/8/58; R. 446.) The State Highway Department ac

quired 26.932 acres of land in Baconsfield by condemnation

proceedings in 1964 to construct a portion of Interstate

Highway 16. (Heirs’ Exhibit I ; R. 923.) The Board of

Managers was awarded the sum of $131,000 in the con

demnation, and the Court ordered that sum paid to the

Chairman of the Board of Managers to be invested in short

term government bonds and to be held subject to the fur

ther order of the court pending the outcome of proceedings

in the instant case (ibid.).

Assets of the Estate

The assets as of April 17, 1967, held by the First Na

tional Bank & Trust Company in Macon, as agent for the

Board of Managers of Baconsfield, were stated by the

Bank as follows (Intervenors’ Exhibit D; R. 594):

“ A ssets :

Cash:

Principal Cash Overdraft

Income Cash Balance

Property:

Real Estate

U. S. Treasury Bonds

Savings Account First

National Bank

Total Assets

Less :

Real Estate

Highway Right of Way Fund

398,766.92

$ 266.44

9,443.67

$ 9,177.23

255,000.00

136,434.98

7,795.05

399,230.03

$408,407.26

255,000.00

143,766.92

Rent Accumulation $ 9,640.34”

28

The original trust fund of $10,000 in bonds left by Sen

ator Bacon, was long ago “ depleted” according to the

City (City’s Answer to Interrogatory No. 13; R. 153).

An accounting filed by the successor trustees with the

court below on June 3, 1968, showed the total trust assets

to be $404,810.77, including a book value for the real estate

of $255,000 (R. 1055).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided

The petitioners’ federal constitutional objections to the

order of the court below ruling that the Baconsfield Park

property had reverted to the heirs were stated in their

Response to the motion for summary judgment (R. 157-

160) and in their several supplemental responses (R. 371-

374, 695-706, 917-918, 971). The federal constitutional ob

jections were repeatedly and elaborately articulated. The

following excerpts from the Supplemental Response and

the Second Supplemental Response represent the general

thrust of petitioners’ argument as stated to the Superior

Court:

The entry of a judgment to the effect that the trust

properties should revert to the heirs of Senator Bacon

would violate the intervenors’ rights under the Due

Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution,

in that:

(a) A Judicial decree of reversion would not im

plement the intent of Senator Bacon’s will, which ex

pressed the legally incompatible intentions that (1)

Negroes be excluded from Baconsfield Park, and (2)

that Baconsfield Park be kept as a municipal park for

ever. A judicial choice between these incompatible

29

terms must be made in conformity with the said

Fourteenth Amendment. The affirmative purpose of

the trust, to have a park for white people, will not fail

if the park is opened for all, and for the court to rule

that the mere admission of Negroes to the park is such

a detriment to white persons’ use of the park as to

frustrate the trust and cause it to fail, would be a viola

tion of the said Fourteenth Amendment. (R. 371-372)

# * *

An application of the reverter doctrine or other doc

trine finding a failure of the trust on the facts of this

case would amount to a judicial sanction which imposed

a penalty because the agencies managing Baconsfield

Park fulfilled their Fourteenth Amendment obligation

to operate the park on a racially non-discriminatory

basis. The use of such a judicial sanction in these

circumstances would violate the intervenors’ rights

under the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States. (R. 702)

— 6 —

The due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States require that the racially exclusionary

words of Senator A. 0. Bacon’s will relating* to Bacons

field Park be treated by the courts as pro non scripto

as though they were never written. This is required,

firstly, because the racially exclusionary terms were

written in the will to conform to racially exclusionary

suggestions and requirements of Georgia Code Section

69-504 (Georgia Acts 1905, p. 117). The racial portions

of Section 69-504 are void under the Fourteenth

Amendment, and indeed were void ab initio even under

the “ separate but equal” doctrine, by authorizing the

30

total exclusion of Negroes from public parks, and thus

must be regarded as pro non scripto. Secondly, it is

required because by the City’s acceptance of the park,

pursuant to Georgia Code Section 69-505 (Georgia

Acts 1905, pp. 117-118), and its operation of the park

in accordance with Bacon’s will, the will was made a

part of the City’s own laws governing the operation

and use of the park, and is to be treated in the same

manner as if the racially exclusionary words appeared

in a city ordinance. (R. 702-703)

— 9 —

By virtue of all the facts and circumstances pre

sented on the record of this case the City of Macon

has so invested the Baconsfield Park with a public

character, and the City has become involved to such

an inextricable extent, that it would be a violation of

the intervenors’ rights under the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment for the state courts to apply any state law doc

trines (whether relating to trust law, the law of dedica

tion, real property law, or other principles), so as to

defeat the rights of the intervenors to racially non-

discriminatory use and access to the park as a public

park. (R. 704-705)

Before the Superior Court the constitutional claims were

argued orally and were presented in full written briefs.

The ruling of the trial court on petitioners’ constitutional

arguments was brief and general. The court stated in its

order of May 14, 1967 (R. 1002):

It is my opinion that Shelley vs. Kraemer, 334 U.S.

1, 68 S.Ct. 836, 92 L.ed. 1161 (1948), does not sup

port the position of the intervenors. It is further my

opinion that no federal question is presented in regard

to the reversion of Baconsfield, but rather this prop

31

erty has reverted by operation of law in accordance

with well settled principles of Georgia property law.

The federal questions were preserved on appeal by ap

propriate enumerations of error and again fully briefed

before the Supreme Court of Georgia. The Supreme Court

of Georgia also rejected petitioners’ constitutional argu

ments on the merits. The court stated at the conclusion

of its opinion (R. 1125-26) :

6. The intervenors urge that they have been denied

designated constitutional rights by the judgment of

the Superior Court of Bibb County holding that the

trust has failed and the property has reverted to Sen

ator Bacon’s estate by operation of law. We recognize

the rule announced in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1

(68 SC 836, 92 LE1161, 3ALR2d 441), that it is a viola

tion of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution for a

state court to enforce a private agreement to exclude

persons of a designated race or color from the use or

occupancy of real estate for residential purposes. That

case has no application to the facts of the present

case.

Senator Bacon by his will selected a group of people,

the white women and children of the City of Macon,

to be the objects of his bounty in providing them

with a recreational area. The intervenors were never

objects of his bounty, and they never acquired any

rights in the recreational area. They have not been

deprived of their right to inherit, because they were

given no inheritance.

The action of the trial court in declaring that the

trust has failed, and that, under the laws of Georgia,

the property has reverted to Senator Bacon’s heirs, is

not action by a state court enforcing racially discrimi

32

natory provisions. The original action by the Board

of Managers of Baconsfield seeking to have the trust

executed in accordance with the purpose of the testator

has been defeated. It then was incumbent on the trial

court to determine what disposition should be made of

the property. The court correctly held that the prop

erty reverted to the heirs at law of Senator Bacon.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Importance of the Question in the Framework

of This Case.

A. The Decision of the Georgia Court Frustrates This

Court’s Mandate in Evans v. Newton, 382 V.S. 296

(1 96 6 )

It is evident that the decision to which this petition ad

dresses itself makes a practical nullity of this Court’s deci

sion in Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 (1966). Whether it

rightly does so is, of course, a matter for full argument.

But it may be said in limine that this Court ought to scru

tinize with plenary care a decision of a state court which

utterly frustrates one of its own decisions in the same

case.

But the repugnancy goes deeper than mere practical

frustration. The proceedings of the Georgia court, it is

submitted, have been directly disobedient to the clear im

plication of this Court’s mandate.

When this Court uttered its prior decision in this case,

the Georgia courts had taken one and only one action, with

two aspects. They had accepted the City’s resignation as

trustee, and had appointed new trustees—all for the an

33

nounced purpose of effecting racial discrimination. This

Court “reversed” the Georgia decision. All there was to

“ reverse” was this substitution of trustees, and the “re

versal” must therefore have amounted to a direction to re

instate the City as trustee. This has not been done.

To have obeyed this mandate would have brought it about

that a public trustee, under a duty of defending the trust,

would have continued a party to this action. The city of

Macon, as trustee, would have been formally forced either

to defend this trust against the heirs’ claims or to ac

count politically as trustee to all its citizens, white and

colored, for its letting go by default the park they all will

lose if it reverts. This position of the City might or might

not have been decisive in shaping the fate of Baconsfield

in the Georgia courts. But the hasty dismissal of the City

as a party, in implicit disobedience to the mandate of this

Court “ reversing” a decree that dismissed the City as

trustee, is at the least a peculiar circumstance in the case

that ought to lead to full scrutiny.

B . The Decision of the Georgia Court Is Inconsonant

With Prior Decisions of This Court

The Georgia court’s decision cannot be squared with the

doctrines of McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819);

Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U.S. (6 Wall.) 35 (1867); Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); Barrows v. Jackson, 346

U.S. 249 (1953); Reitman v. Mulltey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967);

and Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964),

amongst others, nor with the decision of the Third Circuit

Court of Appeals in Pennsylvania v. Brown, 392 F.2d 120

(3rd Cir. 1968), cert. den. 391 U.S. 921 (1968), as will

more fully be made to appear in II hereof.

34

C. Allowing the Georgia Court’s Decision to Stand W ill

Seem to Open a Fertile Field for Implementing

Racial Discrimination, and Will Therefore En

courage Schemes Aiming at Such Discrimination

The present case is a very strong one for scrutinizing

the state court’s action. First, the penalization by reverter

is not in obedience to any private person’s formed intent,

but is rather by operation of present-day Georgia law (as

is admitted by the Georgia court, see infra, p. 38). Sec

ondly, the penalty operates not on a deliberately chosen

breach of the terms of a deed or will, but on a breach

compelled by the Fourteenth Amendment; the citizens of

Macon are being deprived of their park because their city

government is performing its federal duty. Thirdly, pub

lic rather than merely private interests are at stake.

If this Court lets stand without examination a case de

creeing reversion on these extreme facts, the Georgia

court’s untouched ruling will be widely cited a fortiori to

establish that the weapon of reverter is a legitimate one

for enforcing racial discrimination in a vast range of cir

cumstances. Racial discrimination will be reinvigorated

and given new hope. This Court will in any case ultimately

have to deal with the situation thereby created. The pres

ent case, for the reasons given, is an unusually favorable

one for making a start.

35

II.

The Decree o f the Court Below Is Hostile to the

Petitioners’ Right to Immunity From Racial Discrim

ination.

A. The D ecree o f the Georgia Court Im poses the Drastic

Penalty o f R everter on Com pliance W ith the Four

teenth Am endm ent, and in so D oing Infringes Upon

a Federal Interest Declared and Created by the Con

stitution, at the Same Tim e and by the Same Act In

flicting Detrim ent on the Petitioners and Encourag

ing Racial Discrimination

The immediate contemporary facts presented by this

record are simple and damning. A park was being operated

by the city of Macon as trustee, and by a Board of Mana

gers appointed by the City Council. The Fourteenth

Amendment says that Negroes may not be excluded from a

park so operated. Macon accordingly allowed Negroes to

use the park. Upon this showing*, the Georgia court decrees,

the extreme penalty of forfeiture of the property.

On the face of it, this constitutes a direct and drastic

interference by the state of Georgia with a course of events

charged with that high and positive federal interest which

attaches to the commands of the Constitution. State power

in no form and on no state-law doctrinal basis may take

action hostile to a federal interest so expressed, and penal

ize that which the Constitution commands. McCulloch v.

Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819); Crandall v. Nevada, 73

U.S. (6 Wall.) 35 (1867); cf. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S.

1 (1948); and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953).

It is clear, in addition, that this action of the Georgia

court will operate as a discouragement to expeditious and

voluntary compliance with the Fourteenth Amendment, and

will encourage racial discrimination, contra the decision

36

in Heitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967). If this Georgia

decision stands, it will he taken as a strong precedent

{supra, I, C) supporting the proposition that state courts

may generally decree reversion of property for breach

of a racial condition. The use of this device, and compli

ance by those placed in terrorem, will undoubtedly be sig

nificant.

Where, as here, the reverter occurs as to public prop

erty, Negroes will be discouraged from asserting their

rights since they will know (and be told) that such asser

tion would be a futility since reversion would attend their

success; this might be of little significance in Macon, but it

might well be highly significant in small communities with

few Negro inhabitants. Cities, reciprocally, would be en

couraged to evade as long as possible their duty to inte

grate. A potential discouragement of racial equality need

not be absolutely certain or highly substantial in order to

offend the Constitution. See Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S.

153 (1964), where the fact that a restaurateur, if he should

desegregate, would be directed to put in separate toilets,

was held sufficient discouragement to make unconstitutional

his, in fact, discriminatory rule.

It is true that the detriment here imposed for failure to

keep Baconsfield white is not one directly avoidable by

keeping Baconsfield white, since that is forbidden by the

Fourteenth Amendment. It might be argued, then, that

the sanction of reverter does not in this case foster racial

discrimination, since the racial discrimination involved

cannot permissibly occur in any case. The consequence of

this argument would seem to be an absurdity—that a state

may impose any forfeiture it likes on the performance of

a compelled federal duty, even though it cannot impose any

forfeiture on the same act when that act is not a federal

duty. If the argument had force, a state could fine a man,

37

in a moderate sum, for paying Ms federal income tax, since

lie has to pay that tax anyway, and hence cannot be in

fluenced not to pay it by the fear of a small fine. Sound

federalism is not built of such scholastic spiderwebs. The

imposition by a state of a forfeiture, on a showing that a

federally imposed duty has been or will be performed by a

municipality, is as noxious an interference with national

supremacy as can well be imagined. U. S. Constitution,

Art. V I; see McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819);

Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U.S. 35 (1867).

A state which would thus impose a drastic forfeiture of

property as a penalty for obedience to the Constitution,

and, moreover, do so in a way that effectively discourages

the assertion of federal rights and encourages their denial

must surely come forward with some justification. The

only justification even specious must be looked for in Sena

tor Bacon’s will. On examination, there are here two pos

sibilities, one of which is totally and clearly demurrable,

and the other of which, being entirely unsustained by the

record, is admitted by the Georgia court not to exist in

fact.

First, Senator Bacon clearly and seriously desired that

Negroes be excluded from this publicly operated park. But

neither he nor any other person has any lawful power to

command such a result. That result can be attained only

by the repeal of the Fourteenth Amendment. Senator

Bacon’s desire in this regard is no more effective in law

than would have been an expressed direction that a colored

citizen of Macon chosen by lot stand in the stocks in the

park every Sunday. There can never have been any doubt

about this, since at least 1956, and no party connected with

this case ever seems to have doubted it, but any possible

doubt was laid at rest by the decision of this Court in

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 (1966).

38

A quite different expressed or implied desire of Senator

Bacon might be brought forward as justification for what

has been done; it might be said that Senator Bacon in

tended, desired, or willed the reversion of this property

to his heirs if Negroes had to be allowed to use the park.

If such intent were discernible, or inferable, an interesting-

question would be presented. The categorical fact is, how

ever, that Senator Bacon’s intent, desire, or will in this