Wright v. Georgia Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Georgia Brief for Petitioners, 1962. b28ae68a-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/667fcc42-709d-4da7-9f62-ab922493271e/wright-v-georgia-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

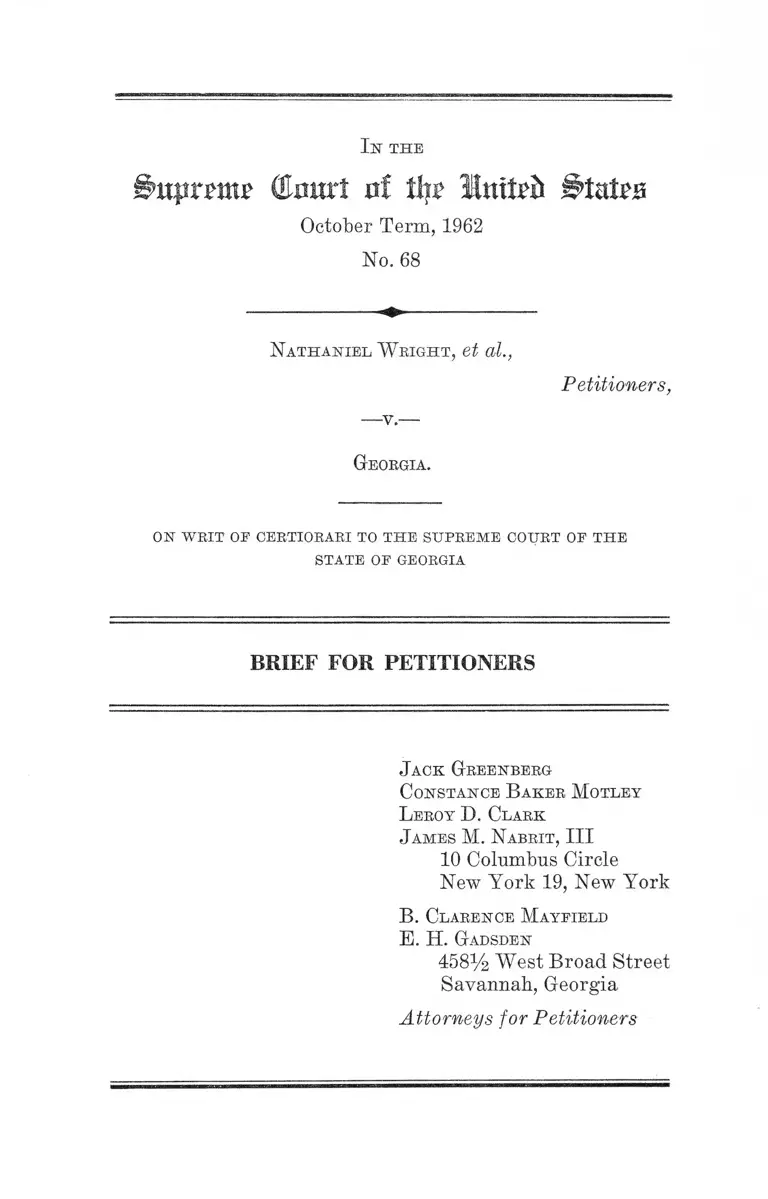

I s T H E

Bxxpxmu GImtrt of tin Into!* BIuXxb

October Term, 1962

No. 68

N ath an iel W eig h t , et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

Georgia.

ON W R IT OE CEETIOEAEI TO T H E SU P R E M E COURT OF T H E

STATE OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack G reenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

L eroy D. Clark

J ames M . N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

B . Clarence M ayfield

E. H. Gadsden

458% West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

INDEX

PAGE

Opinion Below ._................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ............... l

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ___ 2

Questions Presented .... 2

Statement ....... 3

A rgum ent :

I. The Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in

That They Were Convicted Under a Statute

Too Vague and Indefinite to Provide an Ascer

tainable Standard of Guilt, and Which Pro

vided No Fair Warning That Petitioners’

Conduct Was Proscribed. The Only Rational

Alternative Conclusion Would Be That Peti

tioners Were Convicted Without Any Evi

dence of Their Guilt ................ ..... .......... ........ 10

II. The Judgment Below Does Not Rest Upon

Adequate Non-Federal Grounds for Decision 23

Conclusion ................. ............. ................ ............... ............. ......... 29

T able of Cases and O th er A uthorities

Cases:

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219 ................................ 28

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199 .......... 28

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 .......... 16

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) .............................. .......... ...... ...... ................. . 22

XI

PAGE

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 .................................. 20

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278 ............................... 28

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ................................... 21

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .............. .... 14, 22, 23

Chaplinski v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 ............... 14

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 ..14, 26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 .......................................... 16, 21

Elmore v. State, 15 Ga. App. 461, 83 S. E. 799 (1914) .... 12

Faulkner v. State, 166 Ga. 645, 144 S. E. 193 (1928) ..12,14

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157...............12,15,18, 21, 22

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 90 ....................................... 20

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60 ........................... 27

Hague v. C. I. O., 337 U. S. 496 ...................................... 16

Henderson v. Lott, 163 Ga. 326, 136 S. E. 403 ........... 25

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ................................... 13

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 124 F. Supp. 290 (N. D.

Ga. 1954); aff’d 223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955), vacated

350 U. S. 879 .................................................................. 22

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ................... 20

Kent v. Southern R. Co., 52 Ga.. App. 731, 184 S. E.

638 (1935) ........... ................. ............................................. 11

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ........... ........ ....... 22

Lawrence v. State Tax Comm., 286 U. S. 276 ............... 28

Martin v. State, 103 Ga. App. 69, 118 S. E. 2d 233 ....11, 27

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U. S. 877 .................................. ....................................... 20

I l l

New Orleans City Park Improvement Asso. v. Detiege,

PAGE

358 U. S. 54 ....................................................................... 20

Roberts v. Baker, 57 Ga. App. 733, 196 S. E. 104........... 27

Samuels v. State, 103 Ga, App. 66, 118 S. E. 2d 231

(1961) ................................ ...................... .....11,12,13,14,27

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313....... ..... ......................... . 28

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ....................... 16

Taylor v. Georgia, 315 U. S. 2 5 ......................................... 28

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 ............................. ..... 20, 21

Terre Haute I. R. Co. v. Indiana, 194 U. S. 579 ............. 28

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199...............21, 22

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 ......... ....................... 15,16

Union P. R. Co. v. Public Service Commission, 248

U. S. 6 7 .............................................................................. 28

United States v. Brewer, 139 U. S. 278 ....... ................ . 26

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 ..... ......................... 23

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ............................ ..12, 26

Statutes :

United States Code, Title 28, §1257(3) ........................... 1

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, .

Section 1 ............................................................................ 2

Georgia Code Annotated, Section 6-1308 ........ 25

Georgia Code Annotated, Section 24-4515 ....................... 26

Georgia Code Annotated, Section 26-5301 ....2, 3, 7, 8,10,11,

12,16,17, 23, 24

Georgia Penal Code of 1816 (Ga. L. 1816) ................ 11

Georgia Penal Code of 1833, §359 .................. H

IV

Other Authorities:

Black’s Law Dictionary (4th ed. 1951) ............................. 27

Cobb’s Digest of the Statute Laws of Georgia (1851) .... 11

Lamar’s Compilation of the Laws of Georgia (1821) .... 11

Myrdal, An American Dilemma, 618 (1944) ................... 22

Note, 109 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 6 7 ........................................... 19

Webster’s New International Dictionary (2d ed.) ....... 27

PAGE

I n t h e

dmxt ni %

October Term, 1962

No. 68

N ath an iel W righ t , et al.,

Petitioners,

Georgia.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E SU PRE M E COURT OF T H E

STATE OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia is reported

at 217 Ga. 453, 122 S. E. 2d 737 (1961) (R. 52).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was

entered on November 9, 1961 (R. 58). Rehearing was de

nied November 21, 1961 (R. 60). The petition for certiorari

was filed February 17, 1962, and was granted on June 25,

1962. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and

claiming here, denial of rights, privileges, and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Georgia Code Annotated,

Section 26-5301:

Unlawful Assemblies—-Any two or more persons who

shall assemble for the purpose of disturbing the public

peace or committing any unlawful act, and shall not

disperse on being commanded to do so by a judge,

justice, sheriff, constable, coroner, or other peace of

ficer, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

Questions Presented

I.

Whether the conviction of petitioners for unlawful as

sembly denied them due process of law under the Four

teenth Amendment, where they were convicted on no evi

dence of guilt, or merely because they were Negroes who

peacefully played basketball in a municipal park custom

arily used only by white persons, under a statute which

was drawn in sweeping and general terms and which gave

no warning that such conduct was prohibited.

II.

WTiether the decision below asserts any adequate non-

federal ground for limiting consideration of an aspect of

an important constitutional right where the court below

unjustifiably determined that such right had been aban

doned.

3

Statement

Petitioners, six young Negro men ranging from 23 to 32

years of age (R. 39) in Savannah, Georgia, have been

charged and convicted of the crime of unlawful assembly,

a misdemeanor, in violation of §26-5301, Georgia Code

Annotated. It was charged, in an accusation signed by

the Solicitor General of the Eastern Judicial Circuit of

Georgia, that petitioners on January 23, 1961:

. . . did assemble at Daffin Park for the purpose of

disturbing the public peace and refused to disburse

(sic) on being commanded to do so by Sheriff, Con

stable and Peace Officer, to w it: W. H. Thompson and

G. W. Hillis . . . (R. 8).

Petitioners were brought before the city court of Savan

nah, Georgia on May 18, 1961; they filed demurrers raising

constitutional defenses which were overruled (R. 11-13);

entered pleas of not guilty (R. 10); and were tried and

found guilty by a jury (R. 10). The court sentenced five

petitioners to fines of one hundred dollars or five months

in jail (R. 10-11); the sixth petitioner, Nathaniel Wright,

was sentenced to a fine of one hundred twenty-five dollars

or six months in jail (R. 11).

The evidence for the State consisted of testimony by

the two arresting officers, G. H. Thompson and G. W. Hillis,

by another officer, Sgt. Dickerson, who arrived at the scene

of the alleged crime after the arrest, and by Carl Hager,

Superintendent of the Savannah Recreational Department,

who was not present during the incident but testified con

cerning certain city park department policies. The defen

dants presented no evidence.

4

At about 2:00 p.m. on January 23, 1961, police officers

Thompson and Hillis were on duty in an automobile in

Daffin Park, a fifty acre recreational park in Savannah,

Georgia (R. 39; 49). Officer Thompson stated:

This matter first came to my attention when this white

lady had this conversation with us, the lady who told

us that colored people were playing in the Basket Ball

Court down there at Daffin Park, and that is the reason

I went there, because some colored people were playing

in the park. I did not ask this white lady how old

these people were. As soon as I found out these were

colored people I immediately went there (R. 40-41).

When the officers arrived at the basketball court, accord

ing to Officer Hillis,

. . . the defendants were playing basketball. They

were not necessarily creating any disorder, they wTere

just ‘shooting at the goal’, that’s all they were doing,

they wasn’t disturbing anything (R. 50; see also R. 41).

Petitioners were well dressed in street clothes; “ some

of them had on dress shirts, some of them had on coats—

not a dress coat, but a jacket” (R. 39). The two officers

approached the defendants, and both asked the defendants

to leave the basketball court. Officer Thompson testified:

When I came up to these defendants I asked them

to leave; I spoke to all of them as a group when 1

drove up there, and I asked them to leave twice, but

they did not leave at that time. I gave them an oppor

tunity to leave. One of the, I don’t know which one

it was, came up and asked me who gave me orders to

come out there and by what authority I came out

there, and I told him that I didn’t need any orders to

come out there . .. (R. 40).

5

Officer Hillis said:

Officer Thompson told them that they would have to

leave, he told them that at first, and they did have an

opportunity to leave after he told them that. He asked

them to leave, and then I asked them to leave after

I saw they wasn’t going to stop playing, and [fol. 61]

when I asked them to leave one of them made a sar

castic remark, saying: “What did he say, I didn’t hear

him” , he was trying to he sarcastic. When I told them

to leave there was one of them who was writing with

a pencil and looking at our badge numbers. They all

had an opportunity to leave before I arrested them,

plenty of time to have left, but I told them to leave,

they wouldn’t leave and I put them under arrest

(R. 49-50).

Officer Thompson testified further on direct that “ The

purpose of asking them to leave was to keep down trouble,

which looked like to me might start—there were five or six

cars driving around the park at the time, white people”

(R. 40).

On cross examination Officer Thompson said:

I arrested these people for playing basketball in

Daffim Park. One reason was because they were

negroes. I observed the conduct of these people, when

they were on the basketball court and they were doing

nothing besides playing basketball, they were just nor

mally playing basketball, and none of the children from

the schools were there at that particular time1 (R. 41).

(Emphasis added.) 1

1 The officer had testified that children from nearby schools play

in the park “ every afternoon when they get out of school . . . aboiit

2:30 in the afternoon, and this was around 2:00 o’clock” (R, 40).

6

On cross examination Policeman Thompson stated that

there was a driveway about 15 yards from the basketball

court, and that five or six cars were riding around the

driveway, but that “ I wouldn’t say that that was unusual

traffic for that time of day” (R. 41).

Baffin Park, where these incidents took place, is a part

of the system of playgrounds maintained by the Recrea

tional Department of the City of Savannah under the di

rection of Superintendent Carl Hager, who testified that

the city parks were located in various colored and white

neighborhoods with fourteen parks in white areas and

seven parks in Negro areas (R. 42-44), and that “ It has

been the custom to use the parks separately for the different

races” (R. 45). With regard to the Daffin Park area,

Mr. Hager said, “ around that area is mostly white” (R. 43).2

Neither of the arresting officers testified that petitioners

violated any park rules. Officer Thompson said that he had

never arrested people in Daffin Park for playing basketball

there, and that, “ I don’t have any knowledge myself if any

certain age group is limited to any particular basketball

court, I don’t know the rules of the City Recreational

Department” (R. 41).

Superintendent Hager, whose office is located in Daffin

Park, was informed of the arrests after they had been made

and the police and defendants had left (R. 43). He was * I

2 Mr. _ Hager did state that occasionally colored children had

played in the Daffin Park area and that no action had been taken

(R. 43). Officer Thompson said:

I have observed colored children playing in Daffin Park, but

not playing basketball, but I have observed them playing and

fishing, we had gotten previous calls that they were fishing in

there and such, but not playing basketball (R. 42).

He said that he had not arrested those children but that he

arrested these people, the petitioners, “because we were afraid of

what was going to happen” (R. 42).

7

not a witness to the incident. He did testify about certain

park rules and policies, stating that, “ . . . we have no

objection to older people using the facilities if there are

no younger people present or if they are not scheduled

to be used by the younger people” (E. 44), and that,

“ Grownups could use [the basketball courts] if there was

no other need for them” (E. 45). Officer Thompson had

testified that at the time of the arrest “none of the children

from the schools were there at that particular time” and

that “ it would have been at least 30 minutes before any

children would have been in this particular area” (E. 41).

Although the arresting officers made several comments

about the fact that petitioners were wearing street clothes,

asserting that they were dressed up and had on “ nice

clothes” (E. 39; 42; 48), Mr. Hager said that the Eecrea-

tional Department “ would probably not expect” the usual

basketball attire—short trunks, etc.—if persons “were play

ing in an unregulated and unsupervised program, and it

would be consistent with our program to allow persons to

wear ordinary clothing on the courts if they chose to do so,

I don’t think that we would object to that” (E. 45). And,

indeed, Officer Thompson acknowledged that:

The people who play basketball don’t usually have

uniforms on, sometimes they do and sometimes they

don’t.3 It is possible to play basketball in street clothes

(E. 42).

At the close of the evidence defense counsel made an oral

motion for acquittal, arguing that there was no evidence

that defendants went to the park for the purpose of dis

turbing the peace in violation of §26-5301; the court over

3 A portion of this sentence was omitted by the printer in pre

paring the record for this Court. See original record on file in this

Court, pages 53-54.

8

ruled the motion (R. 14-16). The charge to the jury was

general; it did not include any discussion of the elements

of the defense except for a reading of the statute to the

jury and a statement that city police officers were “peace

officers” within the meaning of §26-5301 (R. 61-64). After

the verdict and sentences (R. 10-11) petitioners filed iden

tical motions for new trial, which were overruled by the

court on July 24, 1961 (R. 17-38). The cases were con

solidated for appeal (R. 51).

The Supreme Court of Georgia reviewed the convictions

and affirmed, rejecting petitioners’ arguments (R. 58). The

opinion of the Court dealt with petitioners’ constitutional

claims in the following manner :

1) The Court refused to consider any of the grounds

urged in the motion for new trial, asserting that the ex

ception to the order overruling the motion for new trial

was abandoned by petitioners’ brief in the Supreme Court

of Georgia (R. 54). The Court asserted that the brief con

tained “no argument, citation of authority, or statement

that such grounds were still relied upon,” but “merely re

ferred to the third ground by asking: ‘Did the Court com

mit error in overruling plaintiff’s in error motion for new

trial?’ ” (R. 54).

The motions for new trial (R. 17-38) had objected that

the verdict was “ contrary to the evidence and without

evidence to support it” (HI), “ decidedly and strongly

against the weight of the evidence” (j[2), and was “ con

trary to law and the principles of justice and equity”

(j[3). The motion had claimed a denial to the defendants

of due process of law under the “ First and Fourteenth

Amendments” to the Constitution of the United States in

that “ the statute . . . is so vague that the defendants were

not put on notice as to what criminal act they had allegedly

9

committed” (U4); a denial of due process under the Four

teenth Amendment in that “ said statute is unconscionably

vague . . . nowhere in said statute does there appear

a definition of disturbing the peace or committing any un

lawful act” (ff5) ; and a denial of due process under the

Fourteenth Amendment in that the law gave the “peace

officers untrammelled and arbitrary authority to predeter

mine the commission of the intent to commit an offense

under said statute” , and in that the determination of for

bidden acts was “ left solely to the discretion of the said

Peace Officer” (H6).

The Supreme Court of Georgia ruled on the five conten

tions in the demurrers. It held that paragraphs 3 and 4

of the demurrer (R. 12), which objected that petitioners

were arrested to enforce racial discrimination and a custom

of racial segregation in municipally owned places of public

recreation in violation of the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, on the

ground that these were improper speaking demurrers

(R. 55). The Court rejected the claims of paragraphs 1, 2,

and 5 of the demurrer (R. 11-13), that the statute was

unconstitutionally vague, denying petitioners’ rights under

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

holding that the language of the statute was “ in terms so

lucid and unambiguous that a person of common intelli

gence would discern its meaning and apprehend with what

violation he was charged” (R. 57), and that the law had

“ a clear-cut standard to apprise one of what constitutes a

criminal act and thus to guide the conduct of such officer”

(R. 57).

10

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in That

They Were Convicted Under a Statute Too Vague and

Indefinite to Provide an Ascertainable Standard of Guilt,

and Which Provided No Fair Warning That Petitioners’

Conduct Was Proscribed. The Only Rational Alterna

tive Conclusion Would Be That Petitioners Were Con

victed Without Any Evidence of Their Guilt.

The statute under which petitioners were convicted in

this case, Section 26-5301, Code of Georgia, was held by

the Supreme Court of Georgia to be “ so lucid and un

ambiguous that a person of common intelligence would

discern its meaning and apprehend with what violation he

was charged” (R. 57). The court below discussed peti

tioners’ argument that the law was vague only by referring

to the common law origins of the phrase “ disturbing the

public peace,” by asserting that this phrase was a synonym

of “ breach of the peace,” and that this idea “ has long been

inherently encompassed in our law and is prevalent in the

various jurisdictions” (R. 56). The court also said that

the crime of unlawful assembly has common law origins

(R. 56), but offered no definition of the crime as embodied

in this statute; nor did the court say the statute was the

equivalent of common law unlawful assembly. The opinion

contained no discussion of the evidence in this case.4 The

court did say that it had no occasion to consider the alleged

vagueness of the statutory phrase “ or committing any un

lawful act” , because the accusation charged petitioners only

4 The trial court charge to the jury did not discuss the evidence

or the meaning of the statute, except to state that city policemen

were “peace officers” within the meaning of the law.

11

under the phrase concerning “ disturbing the public peace”

(R. 55).

The Georgia Supreme Court did not refer to any prior

opinions construing Section 26-5301. Prior to this decision,

the statute had been mentioned only two times in pub

lished opinions.5 Kent v. Southern R. C o 52 Ga. App. 731,

184 S. E. 638 (1935),6 and Samuels v. State, 103 Ga. App.

66, 118 S. E. 2d 231 (1961).7 Of these two cases, only the

Samuels case, supra, involved a prosecution under Section

26-5301.

In Samuels v. State, supra, three Negroes were held to

violate Section 26-5301 in a prosecution arising from a

completely peaceful “ sit-in” at a drugstore lunch counter

where the police, but not the owner, ordered them to leave.

The appellate court supplied an element to convict by judi

cially noticing that hostility to lunch counter desegregation

might lead white persons to attack defendants, and that

the defendants should have known this. The facts in the

Samuels case, set out more fully in the note below, bear

5 A similar provision appeared in the Ga. Penal Code of 1816

(Ga. L. 1816, p. 178), Lamar’s Compilation of the Laws of Georgia

(1821), p. 592; and see Ga. Penal Code of 1833, §359, Cobb’s Digest

of the Statute Laws of Georgia (1851), p. 810. No reported cases

have been discovered which discuss either of these predecessors of

§26-5301.

6 Kent v. Southern R. Go., supra, was a damage suit brought by

a picketing mill worker against a railroad for injury sustained from

a tear-gas gun discharged by a police chief at the request of a rail

road conductor to disperse a group of 50 strikers, including plain

tiff, who were blocking a train from entering a mill by standing

on the tracks. In holding the complaint demurrable, the court said

that plaintiff and those with him blocking the train violated §26-

5301 and other penal laws.

7 A companion case, Martin v. State, 103 Ga. App. 69, 118 S. E.

2d 233, affirmed convictions said to be on facts similar to Samuels,

supra, on authority of that case, without discussion of the facts or

§26-5301.

12

a striking similarity to Gamer v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157;

the same is true of the judicial notice theory argued hut

rejected in Garner, supra.11

Petitioners submit that §26-5301 is by no means clear

and unambiguous, either in its terms or in light of the con

struction placed upon it by the state courts. The antiquity

of the law does nothing to add clarity to it, particularly

since it has so rarely been mentioned in the case law.8 9

If the Samuels case construction of the law is accepted,

the statute certainly affords no ascertainable standard of

8 In Samuels v. State, supra, it was undisputed that defendants

were quiet, peaceable, and orderly and that they merely courteously

requested service at a lunch counter customarily reserved for

whites; that they were refused service because they were colored;

that they were not asked to leave by any store employee; that a

police officer was called and defendants were arrested for not obey

ing his order to leave (118 S. E. 2d at 232-233). There was no evi

dence of any threats or actual violence or disorder, but a number of

white persons gathered as onlookers, and several witnesses opined

“that the presence of the defendants would tend to create a dis

turbance” (Ibid.). The Georgia Court of Appeals construed §26-

5301 to cover such orderly conduct that was not in and of itself a

disturbance of the peace. To support this the court quoted at

length from Corpus Juris for a definition of “breach of the peace”

and cited two Georgia decisions holding that cursing and abusive

language tending to incite to immediate violence is a breach of the

peace. See, e.g., Faulkner v. State, 166 Ga. 645, 144 S. E. 193

(1928), and Elmore v. State, 15 Ga. App. 461, 83 S. E. 799 (1914).

To sustain the conviction, the court held that the trial court “un

doubtedly” judicially noticed the fact that lunch counter segrega

tion was a custom throughout the southeast part of the United

States; that “ the vast majority of the white people in these areas”

have such strong feelings in favor of continuance of these customs

that “attempts to break down the custom have more frequently than

not been met with violent and forceable resistance on the part of

the white people” (168 S. E. 2d at 233). The court then conchided

that defendants were bound to know that their acts “might” result

in violent opposition by local white people, and on this basis held

the arrests and convictions justified. (Ibid.)

9 Laws similar to the statute in Winters v. New York, 333 U. S.

507, 511, were said to have “ lain dormant for decades.”

13

guilt. There is no real standard for determining the ex

istence of a “purpose to disturb the public peace.” This

determination is left entirely in the discretion of the police,

the courts, and the jury. When the law is construed to

apply to peaceful and orderly conduct which may incite

others to violence, without any required showing of threats

or other overt manifestations of impending disorder or

violence, the question left for the court or jury is : Whether

under existing conditions, including the attitudes of a com

munity majority with respect to particular peaceful and

lawful conduct, as appraised by the court or jury from

general knowledge not limited to the evidence, the defen

dant should have believed that his conduct might result

in violent opposition? This is plainly not a mere require

ment that a defendant make a forecast based on a rule of

reason. Rather, it is a requirement that he forecast a

jury’s determination which in itself must be based on

“ pure speculation” as to the future conduct of others.

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 263. I f the public atti

tudes that this determination involves were a fixed and

static thing, the decision would be perilous enough— even

for a scientific opinion analyst or pollster. But public atti

tudes are not static. The subject of race relations, for one

example, readily brings to mind cases of peaceful accept

ance of desegregation in places where there has been ex

pected violent opposition. Indeed, lunch counters in Savan

nah have been desegregated notwithstanding the views

expressed in the Samuels case, supra (New York Times,

July 9,1961, p. 65, col. 1). Cf. footnote 8, supra.

To make the peaceful exercise of a constitutional right

subject to a preliminary guess of this nature, under penalty

of fine or imprisonment, is so to deter the exercise of the

right as to practically destroy it. See Herndon v. Lowry,

301 U. S. 242, 261-264. Just as the “ current rate of per diem

14

wages in the locality” was held inherently incapable of fixa

tion in Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269 IT. S. 385,

393-395, so in this case the required judicial appraisal of

the attitudes of an amorphous vast community majority,

as viewed from the defendants’ point of view, provides no

ascertainable standard for the court or jury.

If the statute is considered without the benefit of the

construction given it in the Samuels case, supra, it could

not be known whether the law covered peaceful and orderly

acts or merely outwardly disorderly conduct; whether an

actual or an imminent or merely a foreseeable disturbance

was required; whether violence was essential and, if so,

whether it must be actual or merely threatened; whether

the defendants’ “ purpose” must be manifested by some

overt act or whether it may be supplied by a jury deter

mination, discretionary or otherwise.

It is evident that this law is not “narrowly drawn to

define and punish specific conduct,” Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296, 311. Here, as in Cantwell (310 U. S. at 308),

the vice of the law consists in its “ sweeping in a great

variety of conduct under a general and indefinite charac

terization and leaving to the executive and judicial branches

too wide a discretion in its application.”

The opinion below cites Faulkner v. State, 166 G-a. 645,

665, 144 S. E. 193 (1928), a case holding that abusive and

profane language was a breach of the peace. This Court

has upheld a prohibition aimed at such direct incitements

to violence in a law “ narrowly drawn to define and punish

specific conduct.” Chaplinski v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. S.

568, 573. Insulting or fighting words were said to receive

no protection as free speech because they are “no essential

part of any exposition of ideas and are of such slight social

value . . . ” (315 IT. S. at 572). But no comparable char

15

acterization can be given to petitioners’ conduct, whether

it be regarded as merely playing a basketball game, or as a

profound non-verbal expression of the impropriety of racial

segregation in public parks.

As stated by Mr. Justice Harlan, concurring in Garner

v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 202:

But when a State seeks to subject to criminal sanctions

conduct which, except for a demonstrated paramount

state interest, would be within the range of freedom

of expression as assured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment, it cannot do so by means of a general and all-

inclusive breach of the peace prohibition, it must bring

the activity sought to be proscribed within the ambit

of a statute or clause “narrowly drawn to define and

punish specific conduct as constituting a clear and

present danger to a substantial interest of the State.”

Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra (310 U. S. at 311);

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 105.

As this court held in Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S. 88,

97, “ a penal statute . . . which does not aim specifically at

evils within the allowable area of state control but, on

the contrary, sweeps within its ambit other activities that

in ordinary circumstances constitute an exercise of free

dom of speech or of the press” brings to bear a threat

similar to that involved in discretionary licensing of free

expression. That opinion said:

The existence of such a statute, which readily lends

itself to harsh and discretionary enforcement by local

prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed

to merit their displeasure, results in a continuous and

pervasive restraint on all freedom of discussion that

might reasonably be regarded as within its purview.

310 U. S. at 97-98.

16

Similarly here, the existence of an indefinite unlawful

assembly law operates to deter and restrain any attempt

by Negro citizens to exercise constitutional rights to non-

segregated use of public facilities. The Fourteenth Amend

ment was primarily designed to protect the civil rights

of Negroes. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 307.

Such rights cannot properly be regarded as any less pre

ferred than the First Amendment type protections incor

porated into the Fourteenth Amendment by the due process

clause. The right to nonsegregated use of facilities the

government provides is so fundamental as to be protected

both as “ liberty” under the due process clause and by the

equal protection clause of the Amendment. Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 19; cf. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497.

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, also supports the proposi

tion that §26-5301 is unconstitutionally general and in

definite. In Hague, supra, the right of free assembly was

limited by a requirement that a permit be obtained from

an official who could refuse a permit only “ for the purpose

of preventing riots, disturbances, or disorderly assemblage”

(307 U. S. at 502, n. 1). The court held the law invalid

on its face because, “ it can thus, as the record discloses,

be made the instrument of arbitrary suppression of free

expression. . . . But uncontrolled official suppression of

the privilege cannot be made a substitute for the duty to

maintain order in connection with the exercise of the right”

(307 U. S. at 517). And, of course, one accused under a

general and sweeping law has no obligation to demonstrate

that the state could not have written a different and more

precise law constitutionally proscribing his conduct. Thorn

hill v, Alabama, supra, at 198. Furthermore:

[I] t is the statute and not the accusation or the evi

dence under it, which prescribes the limits of per

missible conduct and warns against transgression.

17

Stromberg v. California, 238 IT. S. 359, 368; Schneider

v. State, 308 U. S. 147,155, 162,163. Compare Lanzetta

v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451. (Ibid.)

Turning to the facts of the present case, it is equally

apparent that §26-5301 gave no fair warning of the offense

punished, and that it would confer unrestrained discretion

of the exercise of constitutional freedoms.

First, there was no claim that petitioners’ conduct was,

in itself, disorderly or offensive. The police officer testified

to the contrary that “ they were not necessarily creating

any disorder, they were just ‘shooting at the goal,’ that is

all they were doing. They wasn’t disturbing anything”

(E. 50). There was no admission by the defendants of a

purpose to disturb the public peace, and there was nothing

in their conduct which might justify a determination that

they had such a purpose. This is true because there was

neither an actual disturbance of the peace, nor any evi

dence that their conduct made such a disturbance imminent

or even foreseeable because of its tendency to provoke a

disorderly response from others. The only thing in the

record touching upon the possibility that defendants’ con

duct might have led to a breach of the peace was testimony

by officer Thompson that:

The purpose of asking them to leave was to keep

down trouble, which looked like to me might start—

there wrere five or six cars driving around the park at

the time, white people (sic) (R. 40).

There was an unexplained statement that “ . . . I arrested

these people because we were afraid of what was going to

happen” (E. 42). But the record contains no support for

the policeman’s fears. There was no evidence that anyone

in the passing automobiles even observed petitioners, and

18

certainly no evidence that these passersby did or said any

thing to indicate that they were disturbed in any way or

were provoked or angered by petitioners’ conduct. There

was no evidence that any of the automobiles stopped or

approached petitioners, or that traffic was impeded. There

is a positive statement by the officer that this automobile

traffic was not unusual for that time of day (R. 41).

The only other person whom the record shows to have

observed petitioners’ conduct was the unidentified white

lady who reported to the officers merely that colored people

were playing basketball in the park. There was no testi

mony by the officers that she manifested any disturbance,

anger, or anxiety and certainly no indication that she was

provoked to the point of creating disorder. No other per

sons were present.10 11 School children in the nearby schools

were not expected in the area for “ at least thirty minutes”

by the officers (R. 41).11

There is no evidence that petitioners violated any park

rules,12 but, in any event, it appears that the arresting

10 The plain words of the statute require something in addition to

disobedience of the officer’s orders. If this were all that was re

quired, the statute would nevertheless be offensively indefinite.

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 204, footnote 11 (Mr. Justice

Harlan concurring).

11 The officers did not connect their order to leave with the an

ticipated presence of school children, nor was their order that

petitioners leave timed to coincide with the arrival of the children.

There was no park rule or policy prohibiting adults from using the

park facilities when they were not being used by the children

(E. 46) ; nor were any hours posted for use of the basketball courts

(E. 44).

12 The State has argued in its “Brief in Opposition to Certiorari”

in this Court that petitioners were arrested because they were

“grown men” on a “children’s playground” and were dressed in

street clothes. (See Brief in Opposition, p. 10, second paragraph.)

But the superintendent of the recreation department testified that

the basketball courts could be used by adults (R. 44) (and, there-

19

officer did not know the park rules and thus could not have

predicated his command that petitioners leave or the arrest

upon any park rule violation.* 13

The arresting officer expressly acknowledged that race

was a factor in the arrests. Officer Thompson stated that:

I arrested these people for playing basketball in Baffin

Park. One reason was because they were negroes (R.

41). (Emphasis added.)

This testimony, of course, must be understood as it re

lates to the evidence that Baffin Park was one which was

customarily used by white persons, with the occasional ex

ception of Negro children fishing and playing—but not

on the basketball court (It. 42), as a part of a more gen

eral local custom “ to use the parks separately for the dif

fore, petitioners were not on a playground exclusively for chil

dren), and also that it was not improper to wear street clothes in

unsupervised play on the basketball courts. The witness stated that

“ if there was a conflict betwen younger people and the older people

using the park facilities, the preference would be for the younger

people to use them, but we have no objections to older people using

the facilities if there are no younger people present or if they are

not scheduled to be used by the younger people” (R. 44). The

witness said that he would not know whether any program was

scheduled for the time petitioners were there without referring to

his records (R. 47).

13 See Note, 109 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 67, 81:

“ It is scarcely consonant with ordered liberty that the ame

nability of an individual to punishment should be judged solely

upon the sum total of badness or detriment to the legitimate

interests of the state which can be found, or inferred, from a

backward looking appraisal of his trial record.”

And see Id. at footnote 74:

“A state could probably justify punishing most conduct

which it desired to punish on the basis of the after-the-fact

record, by isolating from the precisely detailed circumstances

of the particular defendant’s acts a sufficient quantum of

substantive evil of legitimate legislative concern to dress up

a tolerable constitutional crime.”

20

ferent races” (R. 45). The officer’s actions tend to confirm

his statement that race was a reason for the arrests since

he acknowledged that he proceeded directly to the basket

ball court to investigate upon merely being told that “ col

ored people were playing in the Basketball Court” , and

—insofar as the record reveals—nothing more (R. 41).

The officer did not ask the unidentified white lady who

gave him this information how old the people playing bas

ketball were. As he put it, “ as soon as I found out these

were colored people I immediately went there” (R. 41).

The race of the petitioners cannot validly be made a

basis for the determination of their guilt. The mere pres

ence of Negroes in a facility which they customarily do

not use, cannot be regarded as criminal conduct or as evinc

ing a purpose to violate the law. Taylor v. Louisiana, 370

U. S. 154. It is settled that this municipally operated

park was an area which petitioners had a right to use,

regardless of any segregation rule or custom, Holmes v.

City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; Mayor and City Council of

Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877; New Orleans City Park

Improvement Asso. v. Detiecje, 358 U. S. 54; just as this

was clear in Taylor v. Louisiana, supra, with respect to

interstate transportation facilities. Cf. Cayle v. Browder,

352 U. S. 903; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, 459, 460.

There was no evidence tending to show that petitioners’

action in conflict with the racial custom of park segregation,

would, in the locality involved, be likely to arouse passions

or inflame those opposed to desegregation of publicly owned

facilities. There is no such evidence relating either to the

particular circumstances of this case or to any general

community condition. Here there is not even evidence of

“ restless onlookers” which was held insufficient to sup

port such a claim in Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 IT. 8. 154, 155.

21

Tlie fact that Negro children had used this very park with

out the necessity for any official intervention (though their

presence was noted by the police and park officials), fur

ther undermines any such speculation based on judicial

notice of local attitudes14—even if such opposition could

be substituted for evidence at the trial, as it clearly can

not be under the holding in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S.

157, 173, 175-176.

Even beyond this lack of evidence to provide a basis for

a permissible inference that petitioners’ conduct engen

dered such extreme racial hostility as to ineite unlawful,

violent opposition, it is clear that this is not enough to

justify using the state’s police power to preserve segrega

tion customs. Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154, 156, foot

note 2; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 80, 81; Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. “For the police are supposed to be

on the side of the Constitution, not on the side of discrimi

nation.” Garner, supra, at 177 (Justice Douglas concur

ring) .

The only rational alternative explanation for the con

viction, to the claim that the statute did not fairly warn

against petitioners’ conduct, is that there was indeed no

evidence at all to support these convictions, thus requiring

reversal under the doctrine of Thompson v. City of Louis

ville, 362 U. S. 199. The mere presence of Negroes on a

customarily all-white city owned basketball court “ is not,

because it could not be” unlawful assembly. Thompson v.

14 There is, of course, no necessary consistency, even in a given

locality in the South, between the vehemence of the attitudes of

the white majority toward nonsegregated lunch counter service— as

in Garner, supra— and the same group’s attitude towards an all-

Negro group, as here (or for that matter, even an integrated

group) playing basketball in a city-owned facility customarily

used by whites.

22

Louisville, 362 U. 8.199, 206, citing Lanzetta v. New Jersey,

306 U. S. 451. Certainly this statute does not give clear

warning that the presence of a Negro on a customarily white

basketball court is punishable. It is certainly not difficult

to draft a segregation law specifically making it unlawful

for a Negro to use a “ white” park. Cf. Holmes v. City of

Atlanta, 124 F. Supp. 290, 291-292 (N. D. Ga. 1954); aff’d

223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955); vacated 350 U. S. 879. But the

well-known invalidity of such open segregation laws has

frequently led to the use of Aesopian language to accom

plish the same purpose,15 or the use of catch-all laws to

the same end. Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157.16

Petitioners’ activity, if not a “ demonstration” in the

sense that a sit-in has become a well recognized form of

protest (and there is nothing in the record to indicate

whether petitioners went to Baffin Park as demonstrators

to test segregation or merely to play basketball), was never

theless sufficiently non-conformist to be regarded as evi

dencing petitioners’ conviction that racial exclusion from

a publicly owned park is improper. Such conduct within

the area of protected liberty under the Fourteenth Amend

ment, may not constitutionally be reached by a vague and

indefinite law which does not evince any legislative judg

ment that it represents so clear and present a danger that

it should be criminally proscribed. Cantwell v. Connecticut,

supra; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 196-207 (Mr.

Justice Harlan concurring).

15 Compare the ordinance in Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co.,

280 F. 2d 531, 532 (5th Cir. I960), which replaced an overt

segregation requirement with a mandate of obedience to bus drivers’

orders.

16 The Swedish writer, Gunner Myrdal, noticed this in his book

published 18 years ago saying that “ . .. policemen in the South

consider the racial etiquette as an extension of the law, and the

courts recognize ‘disturbance of the peace’ as having almost un

limited scope,” Myrdal, An American Dilemma, 618 (1944).

23

Finally, the State’s suggested construction of §26-5301

renders it even more indefinite. The “Brief in Opposition

to Certiorari,” p. 12, suggests that the law does not require

criminal intent at all, saying:17

Thus it is not necessary to show whether the petitioners

actually intended to create a breach of the peace to

convict them.

What does “ purpose” refer to if it does not refer to

“ actual intent” ? If this construction of the law is correct,

and no real criminal intent is required under §26-5301 to

convict a person for an act admittedly not blameworthy

per se, Georgia has denied due process. This would be an

“ indiscriminate classification of innocent with knowing ac

tivity [which] must fall as an assertion of arbitrary power”

and which “ offends due process.” Wieman v. U pdeqraff,

344 U. S. 183, 191.

II.

The Judgment Below Does Not Rest Upon Adequate

Non-Federal Grounds for Decision.

Initially it should be emphasized that the court below

indisputably did consider and reject petitioners’ due process

claim under the Fourteenth Amendment. The State has

never argued to the contrary either in its brief in opposition

17 In connection with this the “Brief in Opposition,” p. 12, per

haps harmlessly misquotes Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296,

309. Not so harmlessly it ignores the impact of the following

sentence pointing out that practically all such decisions holding

acts likely to provoke disorder to be a breach of the peace

“even though no such eventuality [disorder] be intended” ,

involved “profane, indecent or abusive remarks directed to the

person of the hearer.”

24

to certiorari or in the court below.18 The court below con

cluded its discussion of the due process vagueness issue

(E. 55-58) by asserting: “However, by applying the well-

recognized principles and applicable tests above-stated, we

find no deprivation of the defendants’ constitutional rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States

Constitution” (R. 57-58).

The only potential area of dispute concerns whether this

Court may consider the facts of petitioners’ case in decid

ing the constitutional claim. This potential conflict does

not arise because the court below ever said that it was pro

hibited from looking at the facts of the case. It did not so

state; there is only an implication that this is so because

the opinion was written as an abstract discussion of the

extent to which §26-5301 was indefinite without reference

to the facts of this case, or any other case; because the

court below ruled that it would not appraise the facts re

lating to another and essentially different constitutional

claim raised in the demurrer—the claim that the arrest was

the product of discriminatory law enforcement designed to

compel racial segregation in public parks; and because the

court ruled that it would not consider petitioners’ claim of

error in the overruling of the motion for new trial.

The conflict over this limited issue is indeed only “ poten

tial” for the State has never argued either in the court

below nor in this Court that no consideration may be given

to the facts of the record in deciding the vagueness issue.

To the contrary, indeed, the State has consistently argued

that petitioners’ acts were criminal under the law and that

it gave them fair warning.19

18 Petitioners have deposited with the Clerk of this Court certified

copies of all briefs filed in the Supreme Court of Georgia.

19 See “Brief in Opposition to Certiorari,” passim; see also, the

State’s “Brief of Defendant-in-Error” in the court below.

25

However, in the event that this matter is viewed by this

Court as having any significance, petitioners present the

following to demonstrate that in the circumstances of this

case no significant limitation can be placed upon this Court’s

review because of any state procedural rule.

As has been said before, petitioners’ due process vague

ness claims were raised in both the demurrer (R. 11) and

the motions for new trial (R. 17, et seep). The vagueness

objections were thus made both before and after the evi

dence against petitioners was adduced.

The Supreme Court of Georgia ruled that it would not

consider the motion for new trial because it read petitioners’

brief as abandoning the objection to the overruling of the

motion for new trial. The opinion below acknowledged (R.

54) that defendants’ brief did contain as one of three “ Is

sues of Law” the following: “Did the court commit error

in overruling plaintiff’s-in-error motion for new trial?” 20

But the court went on to find an abandonment of this claim

asserting that “ there was no argument, citation or author

ity, or statement that such grounds were still relied upon” ,

and that the point must be treated as abandoned under the

applicable rule laid down in Henderson v. Lott, 163 Ga. 326,

136 S. E. 403.21

The court below thus found an implied waiver of a fed

eral constitutional right. There was no assertion that peti

tioners made any expressed abandonment of the claim

20 “Brief of Plaintiff--in-Error” , in court below, p. 6.

21 The opinion below makes no reference to Section 6-1308, Ga.

Code Ann., providing:

“ 6-1308. Questions to ie considered.—All questions raised

in the motion for new trial shall be considered by the appellate

court except where questions so raised are expressly or im

pliedly abandoned by counsel either in the brief or upon oral

argument. A general insistence upon all the grounds of the

motion shall be held to be sufficient. (Acts 1921, pp. 232, 233.)”

26

either in the brief or in oral argument. However, a fair

reading of petitioners’ brief filed in the court below does

not support even the theory of implied abandonment. Peti

tioners’ brief in the court below contained a portion labelled

“ Argument and Citation of Cases” which was not sub

divided,22 and which did argue that the law was vague mak

ing particular references to the facts in this record,23 and

did refer to appropriate decisions of this Court.24

The Georgia Court of Appeals has held that the mere

citation of one applicable decision of that court was snffi-

22 Nothing in the rules of the Supreme Court of Georgia requires

any subdivision of argument among the assigned errors. Rule 14

of the Georgia Supreme Court (printed in Section 24-4515, Ga.

Code Ann.) states:

“ Contents of brief of plaintiff in error.”— The brief of the

plaintiff in error shall consist of two parts:

(1) Part one shall contain a suceinct but accurate statement

of such pleadings, facts, assignments of error, and such other

parts of the bill of exceptions or the record as are essential to

a consideration of the errors complained of.

(2) Part one shall also contain succinct and accurate state

ments of the issues of law as made by the errors assigned,

and reference to the parts of the record or bill of exceptions

necessary for consideration thereof.

(3) Part two shall contain the argument and citation of

authorities.

23 See “Brief of Plaintiffs in Error,” pp. 7-10. One example of

such argument appears at p. 8:

“Plaintiffs-in-Error could not possibly have predetermined

from the wording of the statute that it would have punished

as a misdemeanor an assembly for the purpose of playing

basketball. It follows as a matter of course that if the act

committed was not punishable, then the peace officer would not

have the authority to command their dispersal. To be arrested

and convicted pursuant to said statute denies to the Plaintiffs-

in-Error due process of law as secured to them by the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

24 Decisions of this Court on vagueness issues cited in the “Brief

of Plaintiffs in Error” were United States v. Brewer, 139 U. S.

278; Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 393-

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507.

27

cient argument of an assignment of error to prevent its

being treated as abandoned, even absent a clear statement

that the point was relied upon. Roberts v. Baker, 57 Ga.

App. 733, 735, 196 S. E. 104. But here there is even more,

for the argument begins with a statement that the “princi

pal question” was raised by the overruling of the demurrer

(Brief of Plaintiffs in Error, p. 7), thus, plainly implying

that this was not the only question, but merely the chief,

foremost, or highest in importance.25

It is submitted that the basis for this holding of abandon

ment or waiver of an aspect of a fundamental constitutional

defense which is otherwise conceded to have been pre

served, is so tenuous and unsupported as to compel the

view that the court below did not exercise due regard for

the general doctrine that every reasonable presumption is

to be indulged against the waiver of a constitutional right.

Cf. Glasser v. United States, 315 IT. S. 60, 70.

Even beyond all this, if it be assumed arguendo that the

procedural rules applied below must limit this Court’s con

sideration of the petitioners’ due process vagueness claim

to any extent, it by no means necessarily follows that this

Court is compelled to consider the law in a completely

sterile and abstract fashion, blinding itself to the uses to

which this law in all its generalities can be put, and has

been put in the only other reported application of it.

See e.g., Samuels v. State, 103 Ga. App. 66, 118 S. E. 2d

231 (1961); Martin v. State, 103 Ga. App. 69, 118 S. E. 2d

233 (1961). And since even though the Court below may

not have discussed the evidence, it did have the full record

before it, this Court should not ignore the fact that the

very “ judgment of conviction” represents in a real sense

25 See definition of “principal” , adjective, in Webster’s New

International Dictionary, p. 1966 (2d ed.), and Black’s Law Dic

tionary, p. 1355 (4th ed. 1951).

2 8

“ a controlling construction of the statute” , Bailey v. Ala

bama, 219 U. S. 219, 235; Taylor v. Georgia, 315 U. S. 25,

30.

The appellees argue in the “ Brief in Opposition to Cer

tiorari” that this Court may pass upon federal issues where

the state court has refused to entertain them only if the

State has applied a procedural rule inconsistently. But this

Court has found such refusals unreasonable for reasons

other than inconsistent application. Staub v. Baxley, 355

U. S. 313; Terre Haute I. R. Go. v. Indiana, 194 IT. S. 579,

589; Union P. R. Co. v. Public Service Commission, 248

IT. S. 67. Indeed, this Court has rejected attempts to limit

the scope of its review on the theory that denials of due

process must be ignored when, although they appear clearly

from the proceedings, objections made were not renewed

after the denial of due process became manifest. See Black

burn v. Alabama, 361 IT. S. 199, 209-210; Brown v. Missis

sippi, 297 U. S. 278, 286-287.

Any state avoidance of federal constitutional issues

raised by a defendant in a criminal proceeding must meet

minimum standards of intrinsic fairness. It is submitted

that the action of the court below in limiting consideration

of the due process vagueness issue fails to meet such stand

ards, and is as much a denial of due process as an er

roneous decision on the merits. Lawrence v. State Tax

Comm., 286 U. S. 276, 282.

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

L eroy D . Clark

J ames M. N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

B. Clarence M ayfield

E. H. G adsden

458% West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

\

'