Wallace v. United States America Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

May 26, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wallace v. United States America Appellant's Brief, 1967. 86b91d60-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/668a55e2-b92e-43da-9b6d-b815dc9de6b3/wallace-v-united-states-america-appellants-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

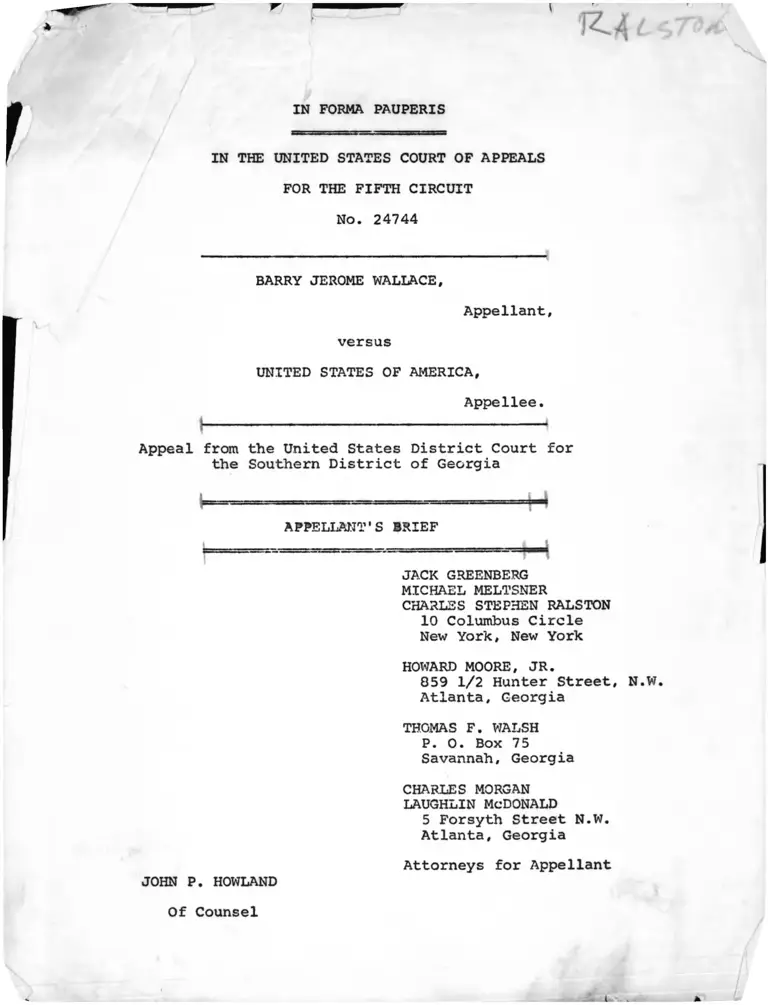

IN FORMA PAUPERIS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 24744

BARRY JEROME WALLACE,

Appellant,

versus

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

\

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Georgia

— — ------------------------ ■ - t—

APPELLANT'S BRIEF

e= , L a : ■ ...- i m a a : - ' ■ iii« .

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

859 1/2 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

THOMAS F. WALSH

P. 0. Box 75

Savannah, Georgia

CHARLES MORGAN LAUGHLIN MCDONALD

5 Forsyth Street N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellant

JOHN P. HOWLAND

Of Counsel

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 24744

BARRY JEROME WALLACE,

Appellant,

versus

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Georgia

APPELLANT'S BRIEF

* »

INDEX

Page

Statement................................................ 1

Specification of Error .................................... H

Argument 12

I. The Judgment Belov/ Must Be Reversed Because The

Convictions Are Not Supported By Sufficient

Evidence........................................... 12

II. The Court Below Erred By Totally Failing To

Charge The Jury As To Criminal Intent................ 22

III. The District Court Erred In Refusing To Continue

The Trial For One Week So That Appellant Might

Be Represented By Retained Counsel Of His Own

Choosing........................................... 29

IV. The Trial Judge, In Imposing The MaximumSentence On Both Charges, Failed To Conform

To The Federal Rules Of Criminal Procedure

And Abused His Discretion............................ 35

Conclusion................................................. 42

I

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Argo v. Wiman, 209 F. Supp. 299 (M.D. Ala.) aff'd 308

F.2d 674 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 371 U.S. 933 (1962). . . . 31

Bartchy v. United States, 319 U.S. 484 (1943). . . 12,15,16,18,19

Boerngen v. United States, 326 F.2d 326 (5th Cir. 1964). . . . 39

Byrd v. United States, 352 F.2d 570 (2nd Cir. 1965).......... 26

Candler v. United States, 146 F.2d 424 (5th Cir. 1944) . . . . 12

Chandler v. Fretag, 348 U.S. 3 (1954)........................ 31

Coleman v. United States, 357 F.2d 563 (D.C. Cir. L965). . . . 39

Cuozzo v. United States, 325 F.2d 274 (5th Cir. 1963)........ 37

Dearinger v. United States, 344 F.2d 309 (9th Cir. 1965) . . . 34

Estep v. United States, 327 U.S. 114 (1946).................. 22

Graves v. United States, 352 F.2d 878 (9th Cir. 1958). . 12,18,25

Green v. United States, 365 U.S. 301 (1961).................. 37

Heard v. Gomez, 321 F.2d 88 (5th Cir. 1963) affirming

per curiam 218 F. Supp 228 (S.D. Tex. 1962).......... 30,34

House v. Mayo, 324 U.S. 42 (1945)............................ 31

Leach v. United States, 334 F.2d 945 (D.C. Cir. 1964)........ 39

Leino v. United States, 338 F.2d 154 (10th Cir. 1964). . . . 32,33

MacKenna v. Ellis, 280 F.2d 592 (5th Cir. 1960).............. 31

Meeks v. United States, 259 F.2d 328 (5th Cir. 1958)......... 20

Politano v. Politano, 262 N.Y.S. 802 (1933).................. 40

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 4 5 .............................. 31

Reynolds v. Cochran, 365 U.S. 525 n. 12 (1961).............. 33

Rogers v. United States, 304 F.2d 520 (5th cir. i°62)........ 39

Ross v. United States. 38C 1960 (6th Cir, 1950) ........ 27

ii -

Page

Steinberg v. United States, 162 F.2d 120 (5th Cir. 1947). . . 28

Sykes v. United States, 373 F.2d 607 (5th Cir. 1966) . . . . 12

United States v. Giessel, 129 F. Supp. 223 (D.N.J. 1955) . . 19

United States v. Karavias, 170 F.2d 968 (7th Cir. 1948) . . 37

United States v. Johnston, 318 F.2d 288 (6th Cir. 1963) . . 33

United States v. Rundle, 230 F. Supp. 323 (E.D. Pa. 1964),

aff'd 341 F.2d 303 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied 381 U.S.

944 (1965).............................................. 34

United States v. Tenenbaum, 327 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1964) . . 38

United States v. Williams, 254 F.2d 253 (3rd Cir. 1958). . . 38

United States v. Wiley, 267 F.2d 453 (7th Cir. 1959) . . . . 39

Venus v. United States, 368 U.S. 345 (1961)............ 12,15,18

Ward v. United States, 344 U.S. 924 (1953) . . . . . 12,18,24,25

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (191C)................ 40

White v. Ragen, 324 U.S. 760 (1945)........................ 32

Williams v. United States, 332 F.2d 36 (7th Cir. 1964) . . . 33

Other Authorities

Title 50, Appendix, U.S.C. §462............... 1,13,22,23,25,26

Federal Rule Criminal Frocedure, R. 32 .................. 36,37

Selective Service System, Legal Aspects of Selective

Service, §55 (1963).................................... 41

The Selective Service, 76 Yale L.J. 160 (1966)............ 41

The Selective Service System, 114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1014 (1966) 41

STATEMENT

Appellant, Barry Jerome Wallace, a Negro, appeals from his

conviction, for two counts of violating 50 App. U.S.C. §462, and

sentence of 10 years imprisonment and $20,000 fine imposed by the

United States District Court for the Southern District of Georgia

on February 15, 1967.

On November 9, 1966, a grand jury of the Southern District of

Georgia returned an indictment charging that Wallace (1) did fail

and neglect to keep his local Selective Service Board informed

as to his address; and (2) did fail and neglect to comply with an

order to report for induction;

THE GRAND JURY CHARGES;

On or about August 29, 1966, BARRY JEROME

WALLACE, whose further and other names are to the

Grand Jury unknown, and who being then and there

a registrant under the Universal Military and

Training Service Act of 1948 with the Selective

Service System Board No. 20, of Chatham County,

Georgia, did, in Chatham County, within the Southern District of Georgia, unlawfully, wilfully

and knowingly fail and neglect to perform a duty

reauired of him under and in the execution of the

Universal Military and Training Service Act and

the rules, regulations and directions duly made

pursuant thereto, in that the defendant, 3arry

Jerome Wallace, did fail and neglect to keep his

local board informed as to his current address

in violation of Title 50, Appendix, U.S.C. Sec

tion 462.

COUNT 2

THE GRAND JURY CHARGES;

On or about July 7, 1966, in the County of

Chatham within the Southern District of Georgia,

BARRY JEROME WALLACE, the defendant, unlawfully.

1

wilfully and knowingly did fail and neglect to

perform a duty required of him under and in the

execution of the Universal Military Training and

Service Act and the rules, regulations, and

directions duly made pursuant thereto, in that

the defendant, Barry Jerome Wallace, did fail and

neglect to comply with an order of his local board

to report for induction into the armed forces of the United States in violation of Title 50, Appendix,

U.S.C. Section 462 (R. 6).

On December 7, 1965 Wallace took an army physical examination

(R. 38, 90). He was found "acceptable" to the army on March 22,

1966 (R. 38). In response to an induction notice he reported to

Fort Jackson, South Carolina as directed for induction into the

Armed Forces on May 9, 1966 (R. 39, 81), but, because of a wound

on his arm, the army refused to accept him for service (R. 43, 81,

106, 107). The Sergeant in command gave him a bus ticket and

said "You are going home for a month" (R. 81, 108, 109).

Wallace returned home to Savannah, Georgia where he lived

at 512 West 33 Street with his mother (R. 69). On May 14, he left

Savannah to continue his work with the Southern Christian Leadership

Council (SCLC), telling his mother to forward his mail to^SCLC

headquarters at 563 Johnson Avenue in Atlanta (R. 50, 82).

Wallace worked for SCLC as a civil rights field worker who attempted

"to get people to vote" (R. 72, 76). The record amply reveals that

this work necessarily involved continuous "traveling around to

different places" in the South (R. 76, 85, 96, 97). For his work

1/ At the beginning of his trial, the United States Attorney

erroneously referred to Wallace's employer as "the SNCC

organization" (R. 25).

2

Wallace received $50.00 every two weeks as a subsistence wage

(R. 65).

A month passed and Wallace neither received any communication

from the army or his local Selective Service Board (R. 44, 83, 84).

He testified in his own behalf that he expected the people at

Fort Jackson to send him "a check or bus ticket or papers to get

back over there" and that he had asked his mother to immediately

forward any mail to his Atlanta forwarding address "and I would

come back home and go over there" (R. 98, 109).

On June 21, 1966, the local Board sent an induction notice

for July 7, 1966 to Wallace's home address at 512 West 33 Street

(R. 37, 41) where it was readdressed and sent unopened to the

Atlanta forwarding address by Wallace's sister (R. 71). Nellie

Mae Wilder, Barry's mother, did not see the notice. At about this

time - "the latter part of June" - Mrs. Wilder moved to 1803

Reynolds Street (R. 70, 71). Barry Wallace, in the field with

the SCLC, did not know at the time of the move (R. 71).

"On or about" July 10, 1966 (R. 83, 84, 112), probably

2/July 8 - but after July 7 - petitioner received mail forwarded

from Atlanta while working around Albany, Georgia (R. 51, 83, 84,

99, 103). Included in the mail was the July 7 induction notice.

Having no money at the time, Wallace telephoned the local board

collect, but the call was refused (R. 84, 85, 97, 113). He

believed that the call was made on Friday because on Saturday

2/ The pertinent days and dates were July 8 (Friday), July 9

(Saturday) and July 10 (Sunday).

3

Wqllace called his local board again but it was closed for the

weekend (R. 85, 97, 114). The next day, Sunday, (July 10th) he

left Albany for Webster County, about 20 miles away (R. 97).

Wallace called his local Board on Monday, July 18, and

3/reached Mrs. Nueslein, a clerk (R. 37, 38, 51, 85, 99, 113). He

explained why he had not called sooner, saying that he had been

driven to Webster County, a rural area, where no phone was avail

able, and the family that he stayed with did not have a car (R. 115).

Wallace also stated that he knew that he would have to wait for the

next draft call - which came monthly - so that he did not believe

it was necessary to speak with his Board immediately (R. 114, 115).

After Wallace advised Mrs. Nueslein that he planned to work in and

around Albany for three or four weeks (R. 100), she suggested that

petitioner "get a transfer to Albany, Georgia, so I wouldn't have

to come back to Savannah for induction, that I could get inducted

in Albany, Georgia, and on my next trip into Albany I went down to

the local board" (R. 85, 100, 101). Although the government did

not call Mrs. Nueslein to testify another Board clerk, Mrs. Evans,

corroborated that Wallace requested a transfer so that he could

report to Albany (R. 37, 39). Subsequent to the phone conversation

on the 18th Wallace checked with the Albany Board clerk but was

told "that she could not do anything at all until she received my

records from Savannah, from the local service board" (R. 86). In

the belief that the Savannah Board was sending his records, Wallace

3/ Mrs. Nueslein is also referred to as "Miss Newsome" in the record.

4

J I

left the address and telephone number where he was staying in

Albany, the Harris family, 635 Whitney Street, with the Albany

Board (R. 51, 116). He had given the same address to Mrs. Nueslein

during their conversation on July 18 (R. 57). After receiving

assurances that the Albany Board would contact him when his papers

arrived from Savannah (R. 51, 116), Wallace resumed his work for

SCLC (R. 116).

As a result of the misunderstanding between Wallace and the

two boards as to how the transfer of records was to be accomplished,

the Savannah local Board sent a notice to Wallace on July 20, 1966

advising him that action would be taken "if he did not comply with"

the enclosed order by July 27, 1966. The government did not intro

duce the order or testimony concerning its contents (R. 39, 41).

It was sent to 512 West 33 Street, since Wallace's mother had

failed to tell the Board of her change in address (R. 70, 71).

This notice was received by her in "latter July" and opened (R. 72).

After reading the contents she requested another son to try to

contact Barry through the SCLC office in Atlanta (R. 72).

Barry Wallace was reported delinquent on August 11, 1966

(R. 40). Two weeks later Barry's brother located him in Atlanta

to tell him that the F.B.I. was looking for him (R. 86). Wallace

returned to Savannah the next day, Friday, August 26th, at

approximately 6:00 P.M. (R. 39, 41, 51, 86, 87, 96). Knowing the

local Board was closed during the weekend (R. 88) Wallace waited

until Monday to go to the Board (R. 87, 93). After being told by

the Board clerk that his case "was out of our hands" (R. 37, 41

87, 93) he expressed a desire to see the F.B.I. (R. 93). The clerk

5

phoned the F.B.I., but when the agent did not arrive in a half an

hour Wallace left the Board office in order to see his immediate

family whom he had not seen since his return to Savannah (R. 88,

93, 117).

The next day at 8:30 A.M. (R. 47), appellant voluntarily

went to the local F.B.I. office and waited to be interviewed by

Agent Salpikas (R. 53, 55). Salpikas had begun his investigation

of petitioner the day before, August 29, 1966. He had first

visited the address listed by the local Board as his current

address, 512 West 33 Street, and had not found Wallace (R. 45).

At the interview the next day Wallace gave his address as 1304

Reynolds Avenue (R. 47), which was incorrect although Salpikas

admitted that Wallace said that he "wasn't sure" of the address

(R. 54, 55, 91). Mrs. Wilder testified that when the F.B.I. found

her at work, "they said that v/hen Barry came to them he told them

that he wasn't sure of the right number, but he told them where I

worked and I gave them the right address" (R. 73). Further

evidence of Wallace's confusion as to his new address is shown by

the fact that on September 23, 1966 a telegram from the SCLC in

Atlanta containing $56 in bail money arrived originally addressed

to Wallace at 1103 Reynolds Street, the wrong address (R. 65, 66,

73, 74, 75, 95). The telegram was the result of a letter from

Wallace to Hosea Williams of the SCLC in Atlanta, telling of his

arrest and requesting money for a bail bond (R. 95). Wallace's

confusion apparently stemmed from the fact that he had never been

told his new address by his family for a girl from Savannah had

6 -

only told him that his family had moved to 34 and Reynolds (R. 80,

92). VJhen Wallace returned home on August 26, 1966 he found his

home only because he stood on the corner of 34 and Reynolds "and

then my little sister came out the door and grabbed me and I went

in the house. . ." (R. 95).

After his interrogation by Agent Salpikas, Wallace voluntarily

gave the agent a signed statement describing his work during the

past few months and his efforts to clarify his status with the

Board (R. 28, 29, 30). The statement concluded, "I had made no

attempt to evade the draft and will be willing to serve in the

Armed Forces if inducted" (R. 51, 52). Under oath at trial peti

tioner repeated his willingness to be inducted {R. 89), and denied

any intent to either fail to keep the local Board informed of his

current address or fail and neglect to report for induction (R. 91).

He was asked:

"Q. Now, the only reason that you didn't

report is that you didn't have the notice at

that time?

A. That's right. I didn't get the notice

until after I was supposed to report.

Q. Now, are you ready to get into the

draft now?

A. Yes, sir."

Appellant was brought before a United States Commissioner on

September 7, 1966 at which time he was found "financially unable to

obtain counsel" and Attorney Thomas F. Walsh was appointed to

represent him (R. 5). The grand jury returned a true bill on

November 9, 1966 (R. 6).

7

case

On February 14, 1967, the United States Attorney called this

"not for trial but for announcement" because there has been some

question about counsel (R. 13) and because "I just wanted to be

sure when we called this case for trial, Judge, he won't come up

here and say 'my lawyer is in Atlanta'" (R.15). Mr. Walsh then

stated to the court that Wallace had "been in touch" with the

American Civil Liberties Union but "I was appointed to represent

him" (R. 14). The court then interrogated Wallace as follows

(R. 15):

THE COURT: Listen here, Boy, you have not got

any other lawyer besides Mr. Valash (sic) is

that correct?

THE DEFENDANT: He is representing me now.

THE COURT: Well, he is the only lawyer that

is representing you?

THE DEFENDANT: Yes, sir.

On the following day, February 15, appellant decided that he

desired to be represented by the Civil Liberties Union. He had

first spoken with attorneys of the American Civil Liberties Union

in Atlanta, Georgia in December, 1956, but was advised at that time

that the ACLU was not in a position to determine whether they could

represent him. The Union had, however, written a detailed letter

to the United States Attorney on Wallace's behalf in December,

which had apparently prompted the "announcement" of the case the

day before trial (R. 25) .

8

When appellant first learned of the trial (about a week before

the date set by the district court), he again contacted the Atlanta

office of the Civil Liberties Union, and "they said they couldn't

take my case at this time, that they had another case in another

town in Georgia on yesterday and that if I could get it postponed

for about a week they would come down and take it" (R. 24-26).

On February 15, 1967, prior to trial, appellant requested that

the district court continue the trial for about a week so that he

could be represented by an attorney from the American Civil Liberties

Union. He indicated that he had "changed my mind" about representa

tion by Mr. Walsh. The United States Attorney's office did not

oppose the request for a continuance but stated that the Civil

Liberties Union had knowledge of the case since December 2, 1966.

The district court declined to postpone the trial "for the simple

reason that you may come here next week and say you have changed

your mind again and want the Civil Union or some organization."

The court also stated: "I gave you a lawyer, and you don't like

the lawyer I gave you. Now you could be putting this case off

indefinitely." Wallace stated "I didn't have a lawyer then" and

"I am not going to change my mind again," but the court ruled "I am

going to try you." (R. 24-26).

Also on February 15 appellant plead not guilty to both counts

of the indictment and was tried before a jury of the Southern

District and convicted of both counts.

On February 22, 1967, the District court admitted appellant to

bail in the sum of $20,000. Unable to make bail appellant was com

mitted first (on February 15th) to the Chatham County Jail, Savannah,

9

Georgia, and on March 27, 1967 to the Federal Correction Institution

at Tallahassee, Florida. A motion for reduction of bail was filed

before the district court on May 8, 1967. It has not been acted

upon at the time this brief is written.

On February 21, appellant filed a timely motion for new trial

which the district court denied on April 25, 1967. On May 5, 1967,

appellant filed a notice of appeal to this Court and the district

court granted 3eave to proceed in forma pauperis.

10

Specification of Error

1. The court below erred in failing to rule that appellant's

conviction is not supported by sufficient evidence.

2. The court below erred in failing to charge the jury

(1) that a finding of criminal intent is necessary to convict and

(2) as to the meaning of criminal intent.

3. The court below erred in refusing to continue appellant's

trial for a period of one week so that he might be represented by

retained counsel.

4. The court below erred in not giving appellant a meaningful

opportunity to present mitigating information before sentencing,

and in imposing an excessive sentence.

11

ARGUMENT

I

The Judgment Below Must Be Reversed

Because The Convictions Are Not

Supported By Sufficient Evidence

The proper standard for review of the sufficiency of evidence

in a criminal prosecution has most recently been set out by this

Court in Sykes v. United States, 373 F.2d 607, 609 (5th Cir.

1966) :

Our duty in questioning the sufficiency of

circumstantial evidence is to take the view of

the evidence most favorable to the government,

and to question whether the reasonable inferences

to be drawn from such evidence are inconsistent

with every reasonable hypothesis of innocence.

That standard has been applied to a prosecution under the

Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 (now the Universal

Military Training and Service Act) upon review in this Court.

"The evidence is as consistent with innocence as with guilt, and

fails signally to show willful intent, and we are not willing to

convict the defendant on the evidence as disclosed by the record

here." Candler v. United States, 146 F.2d 424 (5th Cir. 1944).

Tested in the light most favorable to the government, the

evidence upon which it relies to support appellant's conviction

is clearly not "inconsistent with every reasonable hypothesis of

innocence" as to each of the charges upon which appellant was

indicted. See Bartchy v. United States, 319 U.S. 484 (1943);

Ward v. United States,- 344 U.S. 924 (1953); Venus v. United

States, 368 U.S. 345 (1961)(incorrectly reported in Lawyer's

Edition Second); Graves v. United States, 352 F.2d 878 (9th Cir.

1958).

12

Alleged Violation of the "Current Address" Rule

The first count of the indictment against appellant charged

that he did "wilfully and knowingly, fail and neglect to. . .

keep his local [Selective Service System] board informed as to

his current address" in violation of 50 App. U.S.C. §462, "On

or about August 29th, 1966."

The uncontested evidence shows that in May, 1966 the files

of Selective Service System Board No. 20 of Chatham County,

Georgia showed appellant's current address to be 512 West 33rd

Street, Savannah, Georgia. It was not disputed that at the time,

appellant resided at that address with his mother. In the latter

part of May, appellant left Savannah to continue his field work

for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. It is unques

tioned that the nature of appellant's employment required him

to travel long distances at frequent intervals, throughout the

South, and the government does not contend that appellant could

have predicted his address during the next two months when he

left Savannah.

Before leaving, appellant gave his mother the Atlanta

address of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference head

quarters and instructed her to forward any papers sent to him at

her home to Atlanta, because the organization's headquarters

would always be cognizant of his location and would forward his

mail to him. Appellant's mother moved to 1803 Reynolds Street,

Savannah, toward the end of June, but appellant was unaware of

her change of address. Despite the move, the record shows that

13

the "512 West 33rd Street" address was sufficient and that

communications fi*om the local Board mailed to that address did

reach appellant. On June 21/ 1966, the local Board mailed

appellant an order to report for induction on July 7. Although

appellant's mother had apparently moved previous to the date of

mailing, she testified that in late June her daughter called her

at her place of employment to tell her that a notice from the

local Board had arrived in the mail, and that her daughter

readdressed the envelope to the Atlanta SCLC headquarters and

placed it in the mail for forwarding. The notice was subsequently

sent on to him from Atlanta, and appellant received the induction

notice at Albany, Georgia on or about July 8th, 9th or 10th, 1966.

Subsequently, appellant attempted to advise his local Board

by telephone of his whereabouts, and to have his records trans

ferred to the Albany, Georgia Board for processing and induction.

Due to the confusion as to how the transfer was to be accomplished,

Wallace's records were never sent to Albany. When he first

learned from his brother that the FBI or the federal marshal had

been looking for him, he returned immediately to Savannah,

arriving Friday evening, August 26, 1966. The following Monday

morning, appellant reported to his local Board and was told that

the matter was out of their hands, that he had already been

classified a delinquent, and that there was nothing his local

Board could do. On that morning, August 29, 1966, appellant was

apparently not asked his current address nor did he volunteer

a false address to the local Board. The Assistant Clerk, Mrs.

14

Evans, of the local Board, testifying at appellant's trial from

Board records, stated that the file contained an oral notation

that appellant came into the local Board office on August 29,

1966 and that as of that date the address posted in his file was

512 West 33rd Street. Appellant testified on cross-examination

that he spoke with Miss Nueslein, not with the Assistant Clerk.

These facts are at the very least as consistent with innocence

of the charge as with guilt. The sum of the evidence is that the

local Board had at all times, both prior to August 29, 1966 and

subsequent thereto, an address in its files at which, or through

which, Wallace could receive his mail, either because it would

be forwarded through the SCLC Atlanta office or because he would

be at home with his mother. The Selective Service Regulations

require no more. §1641.3 provides:

It shall be the duty of each registrant to

keep his local board advised at all times

of the address where mail will reach him.

(Emphasis Supplied)

Furthermore, the propriety of appellant's compliance with the

terms of the Act and Regulations was passed upon by the Supreme

Court in Bartchy v. United States, 319 U.S. 484, 488, where this

Regulation was construed:

We think the Government correctly interprets

the Act, §11 [now 50 U.S.C. §462], and the

regulation, §641.3 [now §1641.3], not to

require a registrant who is expecting a

notice of induction to remain at one place

or to notify the local board of every move

or every address, even if the address be

temporary.

See Venus v. United States, 368 U.S. 345 (1961), reversing 287 F.2d

304 (9th Cir. 1960)(incorrectly reported in Lawyer's Edition Second

15

In answering the government's claim that "at his peril the

registrant must at short intervals inquire at his last address

given to the board" for mail. Justice Reed said:

The regulation, it seems to us, is satisfied

when the registrant, in good faith, provides

a chain of forwarding addresses by which mail,

sent to the address which is furnished the

board, may be by the registrant reasonably

expected to come into his hands in time for

compliance. (319 U.S. at 489)

The "chain" in Bartchy was the office of the National Maritime

Union in Houston, the address given his board, with instructions

to forward mail to the union office in New York, where it would

then be given him either aboard ship or at the New York office.

The "chain" in this case was never any longer. The first

forwarding arrangement ran from Wallace's mother, the address

given the Board (who continued to receive mail at the new

address) to the SCLC headquarters in Atlanta, and thence to

Wallace. And appellant Wallace, unlike seaman 3ar^chy, was never

away from places to receive mail for long periods of time.

Nor may appellant's failure to volunteer to the local

Board his mother's new Savannah address on August 29 be

interpreted as a wilful failure to keep his Board advised of

his current address at which mail would reach him. First, the

record clearly shows that appellant was not certain of the new

address, and when he gave it incorrectly to FBI agent Salpikas

it was with the qualification that he was not certain of the

address. Although he had been in the house for a few days, he

used the wrong street number in writing to SCLC to request bail

16

money after he was arrested. He testified that he knew the

location of the house only as "34 and Reynolds"; that upon his

arrival in the city on August 26 he stood on that corner until

his sister happened to see him and bring him into the house.

Under such circumstances, had appellant volunteered to try to

give his Board the new address, he might well have given them a

false one.

Second, such a step was unnecessary because appellant was

already aware that he would receive mail sent to him from the

local Board, either at his mother's house in Savannah or through

the Atlanta SCLC office. He had no reason to believe that his

Board did not have a current address at which mail would reach

him.

The evidence shows affirmative action by the appellant

to keep in touch with his local Board by an address at which

mail could reach him and by telephone and in person whenever

he learned of any difficulties. The penalty for the failure of

Wallace's forwarding system, made in good faith and well-suited

to his particular needs while traveling on his job, is the present

indictment against him. But the evidence shows neither an actual

failure by appellant to keep his Board informed of his address

where mail could reach him, nor, in any event, any evidence of

wilfulness as required by both the indictment and the statute.

Indeed "on or about August 29, 1966" the date charged in the

indictment Wallace was in the process of actively and voluntarily

seeking to clarify his status by visiting his Board and the F.B.I.

17

To infer wilfulness from the mere use of a mail forwarding

arrangement similar to that approved by the United States Supreme

Court in Bartchy, supra, is of course impermissible. There was

no sufficient evidence to support the judgment of conviction on

the first charge under the indictment. Ward v. United States, 344

U.S. 924 (1953); Venus v. United States. 368 U.S. 345 (1961).

Alleged Failure to Report for Induction

The second count of the indictment charged that "on or about

July 7, 1966," appellant "did fail and neglect to comply with an

order of his local board to report for induction into the Armed

Forces of the United States in violation of Title 50, Appendix,

U.S.C. Section 462."

It is not controverted that the order for induction was

mailed June 21, 1966; that it was forwarded to appellant through

the Atlanta, Georgia office of the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference, and that appellant received the notice after the time

at which he was to report had passed. It is also uncontradicted,

and corroborated by Board records, that after receiving the

notice a day late Wallace made what he thought was a valid

arrangement to have his papers transferred to Albany, Georgia,

in order that he could report for induction, and that he

requested the Albany local Board notify him through an address

and telephone number which he left with them.

This charge cannot be sustained on such evidence. A

strikingly similar situation was presented in Graves v. United

States, 252 F.2d 878 (9th Cir. 1958) . There, the defendant did

not learn of notices to report for induction on October 6 and

18

October 13 until October 27, because he had been working away

from home. The Court of Appeals held the evidence insufficient

to sustain a conviction (252 F.2d at 881):

We think that the Government's proof in

this case falls short of showing that

appellant knowingly failed and neglected

to report for induction into the armed

forces, as notified and ordered to do,

that is to say, on October 13, 1955. The

sanctions cf the Act are directed only

against one "who in any manner shall know

ingly fail or neglect or refuse to perform

any duty required of him under or in the

execution of this title *

"[T]he statute requires something more than

mere failure, for the accused must 'knowingly

fail or neglect to perform' a statutory duty."

United States v. Hoffman, 2 Cir., 137 F.2d 416,

419. The court held that this language meant

that the "usual criminal intent" must be

proven.

Cf. United States v. Giessel, 129 F. Supp. 223 (D.N.J. 1955).

The charge that appellant wilfully and knowingly neglected

to report for induction into the Armed Forces must fall with

the charge that he knowingly failed to keep his Board informed

of his address. The government apparently rested its case upon

the completely unsupported basis that Wallace deliberately

arranged to have his induction notice routed too slowly to be

received in time. If Wallace's good faith forwarding arrange

ment, so similar to that in Bartchy, supra, is not illegal, then

the government's second charge falls of its own weight. No

evidence by the government shows any desire by appellant to evade

induction. Wallace, on the other hand, showed that he had

reported for induction at Fort Jackson only two months earlier,

19

and was rejected because of an arm wound. In addition, the

appellant has steadily maintained, both by affirmative acts and

by statements to the F.B.I. and on trial, that he is ready and

willing to be inducted into the Armed Forces.

This Court has undoubted discretion to review the sufficiency

of the evidence, in order to prevent a miscarriage of justice,

although appellant's appointed counsel did not renew his motion

for acquittal at the close of all the evidence, Meeks v. United

States, 259 F.2d 328 (5th Cir. 1958). It is respectfully sub

mitted that the following considerations support exercise of

that discretion in this case:

(1) Appellant has been sentenced to the maximum penalty

of fine and imprisonment, without the district court having the

benefit of a pre-sentence report, for conduct which barely rises

to the dignity of a criminal charge?

(2) A few months prior to his alleged criminal acts he

voluntarily reported for induction in the Armed Services and

has consistently maintained his willingness to serve;

(3) The record does not contain direct evidence of wilful

ness or criminal intent but does contain direct evidence of

mistake, misunderstanding, and good faith;

(4) Appellant has been forced to remain incarcerated since

February 15, 1967 by reason of his poverty and the high bail

set by the district court. Should this Court reverse on some

ground other than insufficiency of the evidence, his incarceration

could be continued pending re-prosecution even though the evidence

will not ultimately support a criminal conviction;

20

(5) Appellant’s occupation as a civil rights worker may

have influenced the jury in ways no less real for their being

intangible.

21

II

The Court Below Erred By Totally

Failing To Charge The Jury As To

Criminal Intent.

Because of the heavy sentence of fine and imprisonment

punishing appellant for conduct which it is respectfully submitted

does not ever rise to the dignity of a criminal charge, this brief

raises a number of errors meriting reversal of the judgment. The

court, however, need not reach these questions if it agrees that

the verdict is not supported by the evidence as urged in Argument I,

supra. In this argument appellant urges that the district court

erred by failing to instruct the jury (despite timely objection)

that criminal intent was an essential element of the offense and in

any manner to define criminal intent.

50 App. U.S.C. §462 (a) "makes criminal wilfull failure to

perform any duty required of a registrant" Estep v. United States,

327 U.S. 114, 119 (1946) for the statute speaks of "knowingly"

failing or neglecting or refusing to perform certain duties. The

two count indictment asserted that Barry Wallace did "wilfully,

knowingly, fail and neglect to perform a duty required of him . . .

in that . . . [he] did fail and neglect to keep his local board

informed as to his current address. . . [and wilfully and knowingly

did fail and neglect to . . . comply with an order of his local

draft Board to report for induction into the Armed Forces of the

United States. , (R. 6).

At the close of the evidence the court charged the jury (see

22

R. 119-26). First, the court read the indictment; second, the court

charged as to the meaning of reasonable doubt; third, the court

defined circumstantial evidence; fourth, the court instructed jurors

to weigh demeanor of witnesses heavily; fifth, the court charged

that the defendant was entitled to a fair trial; sixth, the court

read portions of §452, without comment; finally, the court explained

why criminal proceedings in the Southern District of Georgia are

conducted in Savannah.

At the conclusion of this charge, appellant’s counsel unsuc

cessfully objected to the court's failure to include four written

charges.

These proposed charges all related to the criminal intent

required to make out a violation of §462 (R. 18-21):

MR. WALSH: Judge, for the record, I want to object

and except to the failure to charge from my request of

charge, I believe they are numbered 2, 3, 4 and 5. These

charges. No. 2, has to do with the word "knowingly", what

that carries and No. 3, as to do with his knowledge of the

existence of the obligation to furnish the address and a

wrongful intent to evade that obligation, and No. 4 is

that when he is charged with knowingly failing or neglecting

to report for induction he cannot be convicted under the

indictment - of a failure of neglect to perform a different

duty at a different time which is for anything that may

have been done prior or subsequent. Number 5 was the same

thing as to the address on refusing to perform any duty required of him under the Military Training and Service Act.

He cannot be convicted under an indictment of a failure and

neglect or refusal to perform a different duty at a dif

ferent time.

THE COURT: Well, I think this: I read them over. I

think I charged the essence of what you say in different

words, I think that it was a legal charge. I charged it

just as fair as I knew how and I charged what he contends

in other language but it was the same reason and with that

I will overrule your motion.

23

MR. WALSH: All right, sir. I wanted to make an

exception. . . (R. 127).

By failing to instruct the jurors that to convict they must

find culpability, i.e., specific criminal intent, and to define

that intent the district court erred fundamentally, for failure to

so instruct permitted the jury to convict appellant on the basis of

merely innocent failure or neglect to do the acts specified in the

indictment, Ward v. United States, 344 U.S. 924 (1953). In this

case the United States must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that

culpable violations of law took place and the jury must be so

instructed:

The sanctions of the Act are directed only

against one "who in any manner shall knowingly

fail or neglect or refuse to perform any duty

required of him under or in the execution of this

title *

"[T]he statute requires something more than

mere failure, for the accused must ’knowingly fail or

neglect to perform’ a statutory duty." United States v. Hoffman, 2 Cir., 137 F.2d 416, 419. The court

held that this language meant that the "usual criminal

intent" must be proven.

In United States v. Chicago Express, 7 Cir., 235

F.2d 785, 736, the court was dealing with similar

language stating: "r7hoever knowingly violates any

such regulation shall be fined not more than $1,000

or imprisoned not more than one year or both." The

court said (at page 786): "By using the word 'knowingly'

in [18 U.S.C.A.] §335, we think Congress, while describing

a state of mind essential for responsibility, removed

violations of the relevant regulations from the classi

fication familiarly known as offenses malum prohibitum,

public welfare, and civil offenses." In thus indicating

that such language carried a requirement of culpable

intent as a necessary element of the offense, the court

quoted from the language of the Court in Boyce Motor

Lines v. United States, 342 U.S. 337, 342, 72 S.Ct. 329,

332, 96 L.Ed. 367. In the latter case the Court referred

to a similar statute as requiring proof that the accused

"willfully neglected to exercise its duty."

24

Graves v. United States, 252 F.2d 878, 881 (9th Cir. 1958).

In Ward v. United States, 195 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1953),

reversed, 344 U.S. 924 (1953) this Court dealt with a conviction

under §462 after a challenge to the trial court's charge as to

motive and intent had been raised. The court affirmed on the ground

that the trial court "stated that the lav; sought to punish a person

only if he knowingly failed or neglected his duty; that an actual

knowledge of the existence of an obligation and a wrongful intent to

evade it is of the essence." But the United States Supreme Court

reversed on the ground that the record did not support that a

knowing violation took place. Here, the district court never sug

gested that the jury must find "actual knowledge of the existence

of an obligation and a wrongful intent to evade it." The court

4/never directed itself to the question.

4/ In Ward this Court approved the following charge:

•<* * * court accordingly instructs the jury

that the Act does not denounce as criminal, every failure

to perform a duty imposed by the statute or regulations,

but only seeks to punish a person 'who shall knowingly

fail or neglect' his duty. There must be a specific wrongful intent. An actual knowledge of the existence

of an obligation and a wrongful intent to evade it is of

the essence. Before this defendant can be found guilty

this jury must be convinced beyond a reasonable doubt

not only that he has failed to keep his board advised

of the address where mail would reach him but also that

he knowingly failed to do so. Unless the element of knowledge on the part of the defendant is found by you

as a fact to have existed, or if you have a reasonable

doubt of its existence, it will be your duty to acquit

the defendant. The intent and motives of the defendant

are the most important factors in this case." (195 F.2d

at 444, note 2)

25

The only reference in the charge to the standard of criminal

intent required by §462 was repetition of the words "wilfully, and

knowingly" when the court read the indictment and the statute to

the jury. This hardly satisfies the court's heavy responsibility

to instruct the jury as to the proper legal standard of intent to

be applied to the specific dates involved. There is no way a juror

could determine from the language of the statute or the indictment

that "knowingly" referred to specific wrongful intent to evade a

known obligation which had to be proven by the government beyond a

reasonable doubt. A layman might easily conclude that a knowing

violation was consistent with good faith, mistake, and unintentional

conduct.

Appellant's counsel have been unable to find any case approving

a charge which totally failed to set out that a finding of specific

criminal intent was required or to define that intent. On the 1965)

other hand, in Byrd v. United States. 352 F.2d 5)0, 572-74 (2nd Cir’y

the charge included a definition of "knowingly" but nevertheless

the second circuit found "plain error" because the the trial judge

in his charge "failed to explain the relevance of criminal intent

to the other factors in the case": "By failing specifically to

instruct the jury that criminal intent was an essential element of

the offense, the court left what it did say about intent and the

act being knowingly committed, unrelated to the other elements of

the crime and omitted any instruction that criminal intent was an

element which the Government, to convict, was required to prove

beyond a reasonable doubt. While it did not define criminal intent

26

as such, it did give one of the generally used definitions of

•’knowingly' which in the circumstances of the case would have suf

ficed, because a finding that one acts knowingly presupposes that

he was apprised of all of the facts which constitute the offense.

'Ordinarily one is not guilty of a crime

unless he is aware of the existence of

all those facts which make his conduct

criminal. That awareness is all that is

meant by the mens rea, the 'criminal

intent', necessary to guilt, * * *.'

'United States v. Crimmins, 123 F.2d 271,

272 (2nd Cir. 1941). . .'

"We conclude that the court's failure to explain the relevance

of criminal intent to the other factors in this case and to describe

it as one of the essential elements of the offense, requiring, as

such, proof beyond a reasonable doubt, was tantamount to no instruc

tion at all on the subject. There was, therefore, plain error which

requires reversal even though no exception was taken below to the

charge as given. Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 107, 65

S.Ct. 1031, 89 L.Ed. 1495 (1945); United States v. Gillilan, 288

F.2d 796 (2nd Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Apex Distributing Co.,

Inc. v. United States, 368 U.S. 821, 82 S.Ct. 38, 7 L.Ed. 2d (1961);

United States v. Noble, 155 F.2d 315 (3rd Cir. 1946)." Byrd, supra.

The district judge also failed to comply with the requirement

of Rule 30 of the Rules of Criminal Procedure. That rule makes it

mandatory that the trial judge inform counsel before argument and

the giving of instructions of his denial of requests for instruction-

The purpose of the rule is to enable counsel to argue his case as

effectively as possible. Ross v. United States, 180 F.2d 160, 165

27

(6th Cir. 1950), But see, Steinberg v. United States. 162 F.2d

120 (5th Cir. 1947)(holding that it was not error to comply with

the rule since +-he requests were properly refused) .

28

Ill

The District Court Erred In Refusing

To Continue The Trial For One Week

So That Appellant Might Be Represented

By Retained Counsel Of His Own Choosing

On September 7, 1966, appellant, an indigent, was arraigned

before the United States Commissioner in Savannah, Georgia. He was

not then represented by counsel and the commissioner appointed Mr.

Thomas Walsh to represent him "until relieved by order of the

District Court" (R. 5). In December, 1966, Wallace spoke with

lawyers of the American Civil Liberties Union in Atlanta, Georgia

but was advised at that time that the ACLU was not in a position

to determine whether they could represent him. The Union did,

however, write a lengthy letter to the United States Attorney on

Wallace's behalf (R. 24-26).

Shortly before his trial appellant again contacted the Atlanta

office of the Civil Liberties Union, and "they said they couldn't

take my case at this time, that they had another case in another

town in Georgia on yesterday and that if I could get it postponed

for about a week they would come dov;n and take it" (R. 24-26) .

On February 15, 1967, prior to trial, appellant requested

that the district court continue the trial for about a week so that

he could be represented by an attorney from the American Civil

Liberties Union. He indicated that he had "changed my mind" about

representation by Mr. Walsh. The United States Attorney's office

did not oppose the request for a continuance but stated that the

29

Civil Liberties Union had knowledge of the case since December 2,

1966. The district court declined to postpone the trial "for the

simple reason that you may come here next week and want the Civil

Union or some organization." The court stated that it had appointed

Mr. Walsh to represent appellant, and that "I gave you a lawyer,

and you don't like the lawyer I gave you. Now you could be putting

this case off indefinitely." Wallace stated "I didn't have a

lawyer then" and "I am not going to change my mind again," but

the court ruled "I am going to try you" (R. 24-27).

The denial of a continuance under these circumstances cannot

be squared with this Court's holding in Heard v. Gomez, 321 F.2d

88 (5th Cir. 1963), affirming per curiam 218 F. Supp. 228 (S.D.

Tex. 1962). There, petitioner's retained counsel submitted a

motion and affidavit stating that he was unable to appear because

he was engaged in trial of a case in New York, and seeking a

continuance until such reasonable time as he could appear. The

motion was denied, a local attorney appointed to represent peti

tioner, and the case was tried and petitioner convicted. The

district court issued the writ of habeas corpus because of the

opinion "that Gomez was denied the right of assistance of counsel

of his own choice and that such was a denial of due process of

law." (218 F. Supp. at 229.) In its per curiam opinion affirming

the judgment, this Court stated (321 F.2d at 89):

. . . we think it clear that the district

judge was right, for the reason that he

gave. . . . Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S.

45, 53 S. Ct. 55, 77 L.Ed. 158.

30

See als.o, MacKenna v. Ellis, 280 F.2d 592 (5th Cir. I960); Argo v.

Wiman. 209 F. Supp. 299 (M.D. Ala.), aff'd 308 F.2d 674 (5th Cir.),

5/cert, denied 371 U.S. 933 (1962).

In Powell v. Alabama. 287 U.S. 45, 69, the Supreme Court said:

If in any case, civil or criminal, a

state or federal court were arbitrarily

to refuse to hear a party by counsel,

employed by and appearing for him, it

reasonably may not be doubted that such

a refusal would be a denial of a hearing,

and, therefore, of due process in the

constitutional sense.

In Chandler v. Fretag, 348 U.S. 3, 10 (1954), the Court found

that a "corollary to this principle is that a defendant must be

given a reasonable opportunity to employ and consult with counsel"

in a case involving a defendant who had requested a continuance so

that he could engage the services of an attorney. The Court also

cited its holding in House v. Mayo, 324 U.S. 42, 45 (1945) that it is

enough that petitioner had his own attorney and was not afforded a

reasonable opportunity to consult with him.

The Supreme Court has made it clear that "it is a denial of

the accused's constitutional right to a fair trial to force him to

5/ In Argo, this Court approved the ruling of the district court

that "the denial of Argo's motion for a short continuance or

delay so that his retained counsel, Arthur Parker, could be

located and be present, and the appointment of counsel who was

not familiar with Argo's case, and the putting of Argo to trial

with appointed counsel in the absence of his retained counsel

was arbitrary action on the part of the trial judge to an extent

that Argo . . . was denied his due process rights in a constitu

tional sense." 209 F. Supp. at 302. The trial in that case had

commenced in the morning with appointed counsel alone, and Argo's

own counsel arrived that afternoon and did in fact participate

in the remainder of the trial. Nonetheless, the writ of habeas

corpus issued.

31

trial with such expedition as to deprive him of the effective aid

and assistance of counsel." White v. Ragen. 324 U.S. 760, 764 (1945).

There may be circumstances where the orderly management of the

judicial processes require that a judge put an accused to trial to

assure that dilatory conduct on the part of the defendant will not

thwart the administration of justice. See, e.g., Leino v. United

States. 338 F.2d 154 (10th Cir. 1964)(refusal to grant a fourth

continuance, sought to permit employment of new counsel, after the

defendant had discharged both an appointed attorney and then a

lawyer he had himself chosen). While "The right to counsel may not

be used to play 'a cat and mouse game with the court,'" 338 F.2d at

156, there is no showing on this record that the request for a first

continuance of one week was for obstructive purposes. It is true

that appellant agreed to be represented by Mr. Walsh at the

"announcement" of the case the day before trial, but this change of

mind does not show obstruction in the absence of objective factors

demonstrating it.

The record merely shows that Wallace had sought the services

of attorneys from the American Civil Liberties Union; that these

attorneys had first indicated they were uncertain whether they

could represent him and had, shortly before trial, expressed a

willingness to represent Wallace if a postponement for about a week

could be obtained. Wallace presented this request to the district

court before trial although not at the "announcement" of the case

on the day before trial. The United States Attorney offered no

32

opposition to the motion, and neither the government nor the Court

in denying the motion referred to any particular need to hold the

trial on February 15, 1967. The record fails to reveal that any

delay had been previously requested by Wallace. The sole reason

given by the district judge for his refusal to postpone the trial

was the possibility that Wallace might seek another postponement.

Clearly the Court had the power and discretion to handle such a

situation when and if it occurred. Cf.. Leino v. United States,

supra. The speculation that one may abuse the process of the Court

at some future time is insufficient as a matter of law to justify

a present denial of an acknowledged constitutional right to a

retained attorney.

Appellant's constitutional right to effective assistance of

retained counsel is in no way diminished by the fact that his

court-appointed attorney may not have been incompetent or inept.

"It is significant that in Chandler [v. Fretag, supra] v/e did

not require any showing that the defendant there would have derived

any particular benefit from the assistance of counsel." Reynolds

v. Cochran. 365 U.S. 525, 531 n. 12 (1961). Accord, United States

v. Johnston. 318 F.2d 288, 291 (6th Cir. 1963); see also Williams

v. United States. 332 F.2d 36, 40 (7th Cir. 1964)(dissenting

opinion).

Nor did appellant v/aive his right to counsel. Although some

courts have found an implicit waiver where a defendant discharges

his attorney at the trial, such cases have uniformly involved

33

defendants who subsequently proceeded pro se, rather than seeking

representation by previously-engaged private counsel. E.g., United

States v. Rundle, 230 F. Supp. 323 (E.D. Pa. 1964), aff'd 341 F.2d

303 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied 381 U.S. 944 (1965).

It should be noted that the courts in treating attempts to

discharge counsel and to proceed pro se have always distinguished

that situation from one where a continuance is required to secure

the presence of a new attorney. See Dearinger v. United States.

344 F.2d 309, 312, n. 5 (9th Cir. 1965). As the court said in

Dearinger in dealing with the issue of whether witnesses could be

called against the advice of counsel: "the interest of an accused

in the selection of witnesses to be called in his behalf is obviously

great. The interest of the court in denying Dearinger that privilege

appears to have been slight." Id.. at 312. Clearly, this analysis

applies with even greater force where the right to be represented

by retained counsel is involved. So this Court ruled in Heard v.

Gomez, supra, and so it should rule here in reversing the judgment

below.

34

IV

The Trial Judge, In Imposing The

Maximum Sentence On Both Charges,

Failed To Conform To The Federal

Rules Of Criminal Procedures And

Abused His Discretion

The trial of this case took one day. The trial judge refused

a continuance of only one week so that appellant could be repre

sented by an additional counsel of his own choosing. As was

pointed out above, the instructions the court gave to the jury

were sparse and inadequate. The jury was out for only twenty

minutes (R. 128), and returned with a verdict of guilty on both

counts. The district court proceeded immediately to sentence

the appellant to the maximum possible sentence under the law,

that is, five years in prison on each count and a $10,000 fine

on each count. After the clerk read the verdict, the following

colloquy took place:

THE COURT: Come around. The jury heardthe evidence in this case and I don't see how

they could have done otherwise. You had good

representation. He is a good lawyer and he

gave you splendid representation. He gave

you good service, but it took more than a

good lawyer to win this case because the

evidence was there. I am not going to re

hash it or say anything further. Nov;, I

am going to sentence you to five years on

each count and $10,000.00 on each count.

Now, you have ten — how many days?

THE CLERK: Ten days.

THE COURT: You have ten days to appeal.

Have you got anything to sr-.y in furtherance of this case?

THE DSrSJSANT: No.

35

THE COURT: How is that?

THE DEFENDANT: No, sir.

THE COURT: All right, I sentence you to the

full penalty.

MR* WALSH: I am going to file an appeal,

Judge.

THE COURT: All right. Now, I thank you

gentlemen for your service and you are excused

until Monday morning. We have got a heavy

docket next week, so you all bring your bread

and butter with you.

THE MARSHAL: Judge is that to run conse

cutive or how?

THE COURT: I am sentencing him to five

years imprisonment and $10,000.00 on count

one and five years imprisonment and $10,000.00 on count two, making a total of ten years

imprisonment and $20,000.00. All right.

(R. 128-29)

Thus the court, in effect, first sentenced appellant to the

■fuii, penalty and then asked appellant whether he had anything to

say. Appellant urges that this procedure violated the Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure. Rule 32(a)(1) states:

Before imposing sentence the court shall

afford counsel an opportunity to speak on

behalf of the defendant and shall address

the defendant personally and ask him if he

wishes to make a statement on his own behalf and to present any information in mitigation

of punishment. (Emphasis added.)

The purpose of this rule is clear; it is to provide the

defendant with an opportunity to present mitigating information

so that the court may make a careful and considered determination

of the sentence. It does not contemplate an empty formality tha+-

only gives the appearance of such a careful consideration without

the substance of it. It is clear that here the judge had already

36

decided the sentence he was going to impose. He announced that

he was going to sentence appellant to the full penalty, five

years on each count and $10,000.00 on each count. After making

that announcement, his then asking the appellant whether he had

anything to say was meaningless. Since the judge had already

obviously made up his mind, appellant could not have been aware

that the purpose of the request was to allow him to make a

presentation that could affect the determination.

Indeed, the judge's question did not even make clear the

purpose of his request; that is, he did not say in the language

of the rule, or any approximation to it, that the appellant could

present information "in mitigation of punishment." He merely

asked whether he had anything to say "in furtherance of this

case." Not surprisingly, Wallace answered no, since it appeared

that the case was over and anything he might say would be super

fluous. The failure of the district court to afford appellant

a meaningful opportunity to present mitigating information thus

violated the rule and requires resentencing. See, Green v .

United States, 365 U.S. 301 (1961); Cuozzo v. United States,

325 F.2d 274 (5th Cir. 1963).

The failure of the judge to conform with the requirement of

Rule 32 was heightened by the lack of any pre-sentence investiga

tion. It is true that it has generally been held that a pre

sentence report is a matter left up to the district court's

discretion and hence is not required, although it is desirable.

See, United States v. Karavias, 170 F.2d 968 (7th Cir. 1948);

37

United States v. Williams, 254 F.2d 253 (3rd Cir. 1958). However,

when the failure of the judge to require a pre-sentence investi

gation and report is seen in the context of the sentencing

procedure as a whole, it demonstrates clearly an abuse of

discretion. The import of the Federal Rules with regard to

sentencing is that the imposition of a sentence is to be a

considered judgment on the part of the district court. Sentencing

is after all the judicial act which is of greatest consequence

to an accused. This means that the district court should weigh

carefully various factors, such as the nature of the crime, the

prior record of the defendant, the possibility of rehabilitation,

the degree of criminal intent, etc. The purpose of a pre

sentence investigation, as well as of the defendant's statement,

is to provide the judge with the information needed for such a

considered judgment.-̂ Here it is obvious that the district

court took none of the above factors into consideration. The

trial took only one day; there was no investigation or inquiry

by the judge into appellant's circumstances. Compare, United

States v. Tenenbaum, 327 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1964). The court

simply imposed a sentence which, under the circumstances of the

case, was incredibly harsh.

6/ The judgment that the sentence imposed was not carefully con

sidered is reinforced by the fact that the marshal had to ask the

judge to specify whether the sentences were to run consecutively

(see colloquy in text, supra).

38

i

Appellant further contends that the totality of the circum

stances surrounding this case make it an appropriate one for

this Court to review and to modify the sentence imposed at trial.

Appellant recognizes that it is a rare case in which an appellate

court will review and modify a sentence when it is within the

bounds of the statute. See, Rogers v. United States, 304 F.2d

520 (5th Cir. 1962); but see, Coleman v. United States, 357 F.2d 563

(D.C. Cir. 1965). However, this case presents an exception to

the rule. In cases where a sentence has been reviewed, some of

the factors taken into account by appellate courts have been the

circumstances of the crime and the general practice of sentencing

when courts are confronted with the same or similar crimes. See,

United States v. Wiley, 278 F.2d 500 (7th Cir. 1960). Also,

sentences have been set aside where a court has applied improper

standards in determining a sentence, or has failed to utilize

procedures available to him in making his determination. United

States v. Wiley, 267 F.2d 453 (7th Cir. 1959); Leach v. United

States, 334 F.2d 945 (D.C. Cir. 1964). And this Court has

indicated, in dicta, that a sentence might be modified where

"the punishment is so greatly disproportionate to the offense

committed as to be completely arbitrary and shocking to the sense

of justice and thus to constitute cruel and unusual punishment."

Boernqen v. United States, 326 F.2d 326, 329 (5th Cir. 1964).

7 /Appellant contends that the sentence here clearly was arbitrary.

7 / Considerations such as the sentence imposed for comparable

offense have been weighed in those cases in which a punishment has

been held to be cruel and unusual, and hence to violate the

39

« - *

To begin with, appellant has at all times expressed a

willingness to be inducted into the Armed Forces. He reported

for induction on May 11, 1966 but was not inducted solely because

the army rejected him because of a wound. He stated to the draft

board, to the FBI, and to the judge and jury below that he was

at all times and is now willing to serve in the Armed Forces.

Nevertheless, he was convicted on both counts and sentenced to

the maximum possible penalty, 10 years in prison and $20,000.00

fine. His case might be contrasted with that of a person who had

conformed to all of the rules and regulations of the Selective

Service System but when the moment came for actual induction

refuses to be inducted and is prosecuted. Such a person, even

though persistent in his refusal to submit to induction to serve

in the Armed Forces, could be subjected only to a single five

years imprisonment and to a $10,000.00 fine. Appellant's case

may also be contrasted with what is apparently the general policy

adopted towards persons who have failed to comply with regulations

but have expressed a willingness to be inducted into the Armed

Services. According to a recent law review note, the general

practice adopted towards persons in appellant's circumstances is

not to prosecute him at all. Rather, on such a person's

J_J (Cont.) Eighth Amendment. See, Weems v. United States,

217 U.S. 349, 380-381 (1910); Politano v. ~Politano, 262 N.Y.S.

802 (1933) . Thus, although the punishment imposed here is within

the bounds of the statute, when the circumstances of the crime

and the general treatment of violators of draft regulations are

considered, it may well be considered so excessive as to constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

40

expression of a willingness to go at once into the Armed Forces,

he is allowed to do so. See, Note, THE SELECTIVE SERVICE SYSTEM,

114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1014, 1034-35 (1966).-^

One wonders therefore why appellant was even prosecuted and

why the district court gave him such a drastic sentence. One

reason alone seems to explain this action; i..e., the desire merely

to vent retribution on appellant, which in no way serves to

further the ends of the proper administration of a system of

criminal justice.

_8/ Quoting a publication of the Selective Service System, Leqal Aspects of Selective Service, §55 at 42 (1953):

Since the purpose of the law is to provide

men for the military establishment rather than

for the penitentiaries...when a registrant is

willing to be inducted, he should not be pro

secuted for minor offenses committed during his processing.

Moreover, persons convicted of violations of the Selective Service

laws but who are willing to be inducted may be paroled into the

Armed Forces, thus escaping a prison sentence. See, Note, THE SELECTIVE SERVICE, 76 Yale L.J. 160, 173 n. 91 (1966). This

possibility was apparently never considered by the district court

in determining the sentence and as far as the “ecord shows was never brought to his attention.

41

Conclusion

1

WHEREFORE, appellant prays that for the foregoing reasons

the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

859 1/2 Hunter Street

Atlanta, Georgia

THOMAS F. WALSH

P. O. Box 75 Savannah, Georgia

CHARLES MORGAN

LAUGHLIN MCDONALD

5 Forsyth Street N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

JOHN P. HOWLAND Attorneys for Appellant

Of Counsel

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that the foregoing Brief for Appellant was

served on Bruce B. Greene, Assistant United States Attorney,

Savannah, Georgia and Ramsey Clark, Attorney General, Department

of Justice, Washington, D. C.. by depositing same in the United

States mail, air mail, postage prepaid, addressed to them at their

offices, this 26th day of May, 1967.

42

Attorney for Appellant

wilfully and knowingly did fail and neglect to

perform a duty required of him under and in the

execution of the Universal Military Training and

Service Act and the rules, regulations, and

directions duly made pursuant thereto, in that

the defendant, Barry Jerome Wallace, did fail and

neglect to comply with an order of his local board

to report for induction into the armed forces of the United States in violation of Title 50, Appendix,

U.S.C. Section 462 (R. 6).

On December 7, 1965 Wallace took an army physical examination

(R. 38, 90). He was found "acceptable" to the army on March 22,

1966 (R. 38). In response to an induction notice he reported to

Fort Jackson, South Carolina as directed for induction into the

Armed Forces on May 9, 1966 (R. 39, 81), but, because of a wound

on his arm, the army refused to accept him for service (R. 43, 81,

106, 107). The Sergeant in command gave him a bus ticket and

said "You are going home for a month" (R. 81, 108, 109).

Wallace returned home to Savannah, Georgia where he lived

at 512 West 33 Street with his mother (R. 69). On May 14, he left

Savannah to continue his work with the Southern Christian Leadership

Council (SCLC), telling his mother to forward his mail to^SCLC

headquarters at 563 Johnson Avenue in Atlanta (R. 50, 82).

Wallace worked for SCLC as a civil rights field worker who attempted

"to get people to vote" (R. 72, 76). The record amply reveals that

this work necessarily involved continuous "traveling around to

different places" in the South (R. 76, 85, 96, 97). For his work

1/ At the beginning of his trial, the United States Attorney

erroneously referred to Wallace's employer as "the SNCC

organization" (R. 25).

2

defendants who subsequently proceeded pro se, rather than seeking

representation by previously-engaged private counsel. E.g.. Uhited

States v. Rundle, 230 F. Supp. 323 (E.D. Pa. 1964), aff*d 341 F.2d

303 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied 381 U.S. 944 (1965).

It should be noted that the courts in treating attempts to

discharge counsel and to proceed pro se have always distinguished

that situation from one where a continuance is required to secure

the presence of a new attorney. See Dearinger v. United States,

344 F.2d 309, 312, n. 5 (9th Cir. 1965). As the court said in

Dearinger in dealing with the issue of whether witnesses could be

called against the advice of counsel: "the interest of an accused

in the selection of witnesses to be called in his behalf is obviously

great. The interest of the court in denying Dearinger that privilege

appears to have been slight." Id., at 312. Clearly, this analysis

applies with even greater force where the right to be represented

by retained counsel is involved. So this Court ruled in Heard v.

Gomez. supra, and so it should rule here in reversing the judgment

below.

34

IV

The Trial Judge, In Imposing The

Maximum Sentence On Both Charges,

Failed To Conform To The Federal

Rules Of Criminal Procedures And

Abused His Discretion

The trial of this case took one day. The trial judge refused

a continuance of only one week so that appellant could be repre

sented by an additional counsel of his own choosing. As was

pointed out above, the instructions the court gave to the jury

were sparse and inadequate. The jury was out for only twenty

minutes (R. 128), and returned with a verdict of guilty on both

counts. The district court proceeded immediately to sentence

the appellant to the maximum possible sentence under the law,

that is, five years in prison on each count and a $10,000 fine

on each count. After the clerk read the verdict, the following

colloquy took place:

THE COURT: Come around. The jury heardthe evidence in this case and I don't see how

they could have done otherwise. You had good

representation. He is a good lawyer and he

gave you splendid representation. He gave

you good service, but it took more than a

good lawyer to win this case because the

evidence was there. I am not going to re

hash it or say anything further. Nov/, I

am going to sentence you to five years on

each count and $10,000.00 on each count.

Now, you have ten — how many days?

THE CLERK: Ten days.

THE COURT: You have ten days to appeal.

Have you got anything to say in furtherance of this case?

THE DffifSJDANT. no .

35

̂ /f ^

expression of a willingness to go at once into the Armed Forces/

he is allowed to do so. See, Note, THE SELECTIVE SERVICE SYSTEM,

114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1014, 1034-35 (1966)

One wonders therefore why appellant was even prosecuted and

why the district court gave him such a drastic sentence. One

reason alone seems to explain this action; i..ê ., the desire merely

to vent retribution on appellant, which in no way serves to

further the ends of the proper administration of a system of

criminal justice.

8/ Quoting a publication of the Selective Service System, Legal

Aspects of Selective Service, §55 at 42 (1963):