Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

July 6, 1998

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Jurisdictional Statement, 1998. 75e426e6-da0e-f011-9989-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/669cd23f-50fa-4fc0-a303-24bb5c83837c/jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

.JUL-22-38 WED 11:46 ~~ NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO. 2026821312 P. 02/23

4 $ TN ——

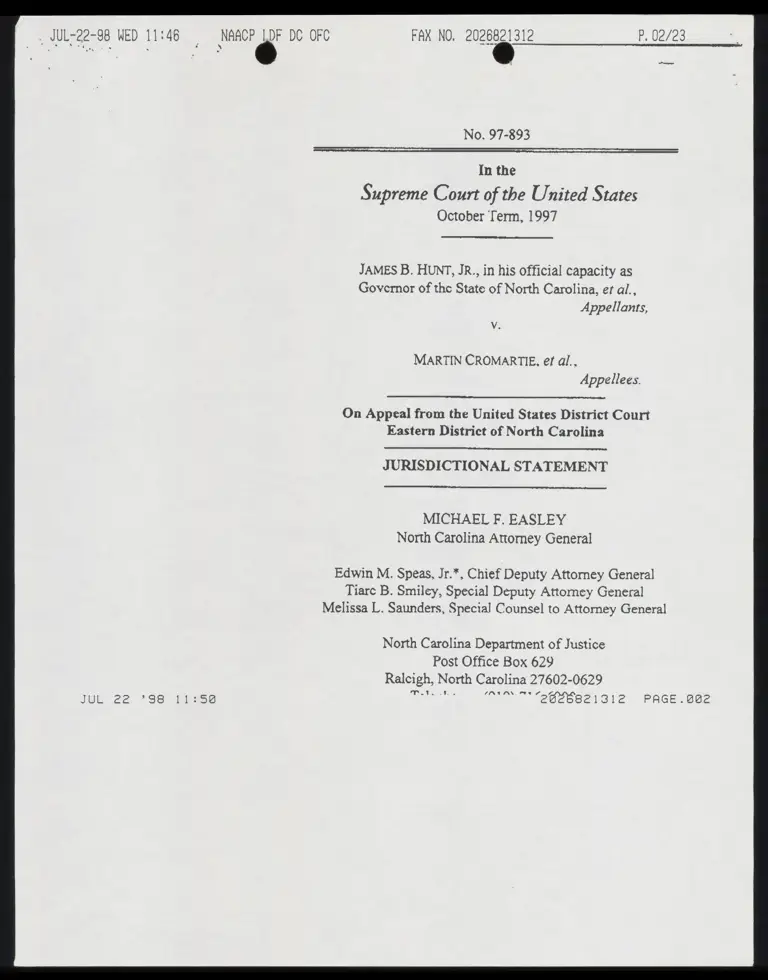

No. 97-893

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1997

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of North Carolina, ef al.,

Appellants,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ef al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

North Carolina Attomey General

Edwin M. Speas, Jr.*, Chief Deputy Attorney General

Tiarc B. Smiley, Special Deputy Attorney General

Melissa L. Saunders, Special Counsel to Attorney General

North Carolina Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602-0629

JUL 22 ’'98 11:58 ST eer i012 PAGE .BR2

JUL-22-98 WED 11:47 NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO, 2026821312

No. 97-893

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1997

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of North Carolina, ef al.

Appellants,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ef al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

North Carolina Attorney General

Edwin M. Speas, Jr.*, Chief Deputy Attorney General

Tiarc B. Smiley, Special Deputy Attormey General

Melissa L. Saunders, Special Counsel to Attorney General

North Carolina Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602-0629

Telephone: (919) 716-6900

July 6, 1998 *Counsel of Record

JULYZ22%"88 11.158 2f26821312 PRAGE.2AB!

JUL-22-98 WED 11:47 NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO. 2026821312 P. 02/22

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

In a racial gerrymandering case, is an inference drawn from

the challenged district’s shape and racial demographics,

standing alone, sufficient to support summary judgment for

the plaintiffs on the contested issue of the predominance of

racial motives in the district’s design, when it is directly

contradicted by the affidavits of the legislators who drew the

district?

Docs a final judgment from a court of competent jurisdiction,

which finds a state’s proposed congressional redistricting

plan does not violate the constitutional rights of the named

plaintiffs and authorizes the state to proceed with elections

under it, preclude a later constitutional challenge to the same

plan in a separate action brought by those plaintiffs and their

privics?

Is a state congressional district subject to strict scrutiny under

the Equal Protection Clause simply because it is slightly

irregular in shape and contains a higher concentration of

minority voters than its neighbors, when it is not a majority-

minority district, it complics with all of the race neutral

districting criteria the state purported to be following in

designing the plan, and there is no direct evidence that race

was the predominant factor in its design?

JUL 22 "98 pS] 2826821312 PAGE .QBAZ

ii

22/80 4

@

®

c

i

l

83202

‘ON

Xud

This page intentionally left blank.

040

3d

447

4I9HN

8b:11

QM

86-22-1Nr

ii

LIST OF PARTIES

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as Governor of the

State of North Carolina, DENNIS WICKER in his official capacity

as Lieutenant Govemor of the State of North Carolina, HAROLD

BRUBAKER in his official capacity as Speaker of the Ncrth Carol'nz

House of Representatives, ELAINE MARSHALL in her official

capacity as Secretary of the State of North Carolina, and LARRY

LEAKE, S. KATHERINE BURNETTE, FAIGER BLACKWELL,

DOROTHY PRESSER and JUNE YOUNGBLOOD in their capacity

as the North Carolina State Board of Elections, are appellants in this

case and were defendants below;

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS CHANDLER MUSE. R. O.

EVERETT, J. H. FROELICH, JAMES RONALD LINVILLE,

SUSAN HARDAWAY, ROBERT WEAVER ard JOEL XK.

BOURNE are appellees in this case and were plaintiffs below.

P

R

G

E

.Q

BB

3

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

:

5

1

’

8

8

J

U

L

22

iv

22/b0 'd

Z » Ele 83202

‘ON

Xvi

This page intentionally left blank.

040

30

407

43YuN

8b:11

IM

86-22-1nr

<

P

R

G

E

.B

QB

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS k

NY

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ov. ...... ooo via i oh ay i

BIS OP PARTIES i. Fi ns ee bs y

TABLEOFAUTHORWIES ............ 0h dw vi

OPINIONS BELOW EAE AR Ry aR POE LE

JURISDICTION Be ees de a Re fre AE)

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED ria ee te ae ee ie Non dh aE id

STATEMENTOFTHECASE ......0... s&s. 2

A. THE 1997 REDISTRICTINGPROCESS. ................ 2

BoTHEISOIPLAN. 0. nit 1 Pe

C. LEGAL CHALLENGES TO THE 1997 PLAN. . .... ...... ©

I. The Remedial Proceedings in Shaw. ........... §

2. The Parallel Cromartie Litigation .... .... .... . 8

D. THE THREE-JUDGE DISTRICT COURT’S OPINION .. ..... © 3

BE. THEINSOSINTERMMPLAN, . ii iiii oom Bi

®

J

U

L

22

2

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

a

<r

—

-—

ey

[1]

=

=

[©]

[

od

i

J,

—>

—

J:

NJ -

br We

L{) =

A

i

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

vi

ARGUMENT Lov. lita a,

I. SUMMARY JUDGMENTISSUE.................

I. PRECLUSION ISSUE. ........

111. PREDOMINANCE [SSUE. ..

CONCLUSION .......c 0 a

. 20

. 30

Vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Ahng v. Alisteel, Inc.,96 F.3d 1033 (7th Cir. 1996) .... ..... 17

Anderson v. Lipo joihy Inc., 477 U.S. 242

(1986) . 13,14,15,16

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1990) ode rane . passim

Celotex Corp. v. Catren, 477 U.S. 317 (1986) ............. I

Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A. v. Celotex Corp.,

S6F3d34IQACI. 998) ovo. ie 17

Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 US. 351 (1876) ............ i$

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1987) ............ 14,16

Federated Dep't Stores, Inc. v. Moitie,

452 U.S. 394 (1981) ...... 18,19

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) .. «23

Gonzalez v. Banco Cent. Corp., 27 F.3d 751

TORR na ae Tl eis 17

Hlinois v. Krull, 480 U.S. 340 (1987) ........ 12

Jaffree v. Wallace, 837 F.2d 146] (11th Cir. FORBY LA

Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529 (1995) 13

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725(1983) ........ ........ 22

Lawyer v. Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186 (1997) . 21,24,25,27,28

P

A

G

E

.B

88

5

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

2

5

2

'

8

8

J

U

L

22

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

a

<I

—

ry

a.

[1]

=

a

oo

|

od

i

—

—

py

P.

06

/2

2

FA

X

NO

.

20

26

82

13

12

vii

McDonald v. Board of Election Commer 's i C. Chicas >

394 U.S. 802 (1969) . irae ICT ho

Miller v. Johnson, 5151.8. 900 (1993) . x passim

Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S. 383 983) o.oo ini 5D

Nordhorn v. Ladish Co., 9 F.3d 1402 (9tk Cir. 1993 ....... 37

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) ...... 14,28

Quilter v. Voinovich, 931 F. Supp. 1032

(N.D. Ohio 10s affd, 118 S. Ct. 1358

(1998) . Si TE . 24,2526,27,28

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 ELL Sete SR 22

Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U S. 57 (1980)... iA

Royal Ins. Co. of Am. v. Quinn-L Capital Corp.,

960 F 2d 1288(Sth Cir. 1992) +... .. 0. 17

Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 1996): +0 veo ur 02 N5,24,26

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630(1393) ......... 3,152024.25.28

Starceski v. nn Elec. Corp, 54 F.3d 1089

(3d Cir. 1995) . HLS REN reat LOB ©

United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (3998): x... . FL ee. 7

Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146 (J993) «.... cn. 00.28

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1078) a nn 2S

1X

P

A

G

E

.

B

8

6

STATUTES AND OTHER AUTHORITIES

28 U.S.C. §1253

28 U.S.C. § 2284(a)

1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, ch. 2, § 1.1

©

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

18 JAMES WM. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE'S FEDERAL

PRACTICE § 131 4013][e}{]}{B] (3d ed. 1997). ........ 49

18 C. WRIGHT, ET AL., FEDERAL PRACTICE AND

PROCEDURES 4457(198Y) .. vu 0 Ao 19

1

5

2

Fl

'

8

8

J

U

L

22

¢é¢/L0 'd

¢l€1¢8920¢

‘ON

Xvi

This page intentionally left blank.

040

30

407

dOWuN

8b:11

JIM

86-¢¢-Nr

No. 97-893

In the

AY upreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1997

JAMES B. HUNT, JR, in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of North Carolina, af al.,

Appellants,

y.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ef al.

Appellees.

Ou Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Governor James B. Hunt, ir., and the other state defendants below

appeal from the firal judgment of the three-judge United States

District Court for the Eastem District of North Carolina, dated April

6, 1998, which held that the congressional redistricting plan enacted

by the North Carolina General Assembly on March 31, 1997, was

unconstitutional and permanently enjoined appellants from

conducting any elections under that plan.

OPINIONS BELOW

The April 14, 1998, opinion of the three-judge district court,

which has not yet been reported, appears in the Appendix to this

jurisdictional statement at la.

P

R

G

E

.

B

Q

7

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

A

4

11

S8

8

JU

L

22

P,

08

/2

2

FA

X

NO

.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

48

[} * = 5

dn

58)

=

a

)

od

N

—

—

—

2

JURISDICTION

The district court's judgment was entered on April 6, 1998. On

April 8, 1998, appellants filed an amended notice of appeal to this

Coun. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U S.C. §

1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This appeal involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and Rule $6 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, Summary Judgment. See App. 1692 & 171a-]73a.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. THE 1997 REDISTRICTING PROCESS.

n.Shaw v. Hint, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (Shaw IT), this Court held

that District 12 in North Carolina's 1992 congressional redistricting

plan (“the 1992 plan”) violated the Equal Protection Clause beczuse

rece predominated in its design and it could not survive strict scrutiny.

On remand, the district court afforded the state legislature an

opportunity to redraw the State’s congressional plan to correct the

constitutional defects found by this Court, and the legislature

established Senate and House redistricting committees to carry out

this task.

In consultation with the tegislative leadership, the commitiees

determined that, to pass both the Demociatic-controlled Senate and

the Republican-controlled House, the new plan would have to

maintain the existing partisan balance in the State’s congressional

delegalion (a six-six split between Democrats and Republicans).

Toward that end, the committees sought a plan that would preserve

the partisan cores of the existing districts and avoid pitting

incumbents against each other, to the extent consistent with the goal

of curing the constitutional defects in the old plan. To craft

-

J

“Democratic” and “Republican” districts, the committees used the

results from a series of elections between 1938 and 1996.

Indesigning the plan, the committees of course sought to cemply

with the requirements of the Voting Rights Act, as well as the

constitutional requirement of population equality. Acutely conscious

of their responsibilities under Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S 630 (1993)

(“Shaw I"), and its progeny, however, they sought a plan in which

racial considerations did not predominate over traditional race-neutral

districting criteria. Toward this end, they decided to emphasize the

following traditional race-neutral districting principles in designing

the plan: (1) avoid dividing precincts; (2) avoid dividing counties

when reasonably possible; (3) eliminate “cross-overs,” “double crass-

overs,” and other artificial means of maintaining contiguity: (4) greup

together citizens with similar needs and interests; and (5) ensure ease

of communication between voters and their representatives. The

committees did not select geographic compactness as a factor that

should receive independent emphasis in constructing the plan.

The committees’ strategy proved successful. On March 31, 1997.

the North Carolina legislature enacted a new congressional

redistricting plan, 1997 Session Laws, Chapter 1] (“the 1997 plan”).

the redistricting Jaw at issue in this case. The plan is a bipartisan one.

endorsed by the leadership of both parties in both houses

B. THe 1997 PLAN.

The 1997 plan creates six “Democratic” districts and six

“Republican” districts. The new districts are designed to preserve the

partisan cores of their 1992 predecessors, yet their lines are

significantly different: they reassign more than 25% of the State’s

' In North Carolina, as in most of the soLtheastemn states, it is viually impossible

to design a congressional rap that does not split zny of the Stats’s 100 countics,

given the conslitutional mandate of population equality and other legitimate

districting concems

P

A

G

E

.

8

0

8

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

:

5

2

*

88

JU

L.

22

od

[QN]

Bi

(®p]

A

Oo.

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

43

3 gt

££

88)

—=

a

Re

od

ii

=

IE

r—

4

population and nearly 25% of its geographic area. The most dramatic

changes are in District 12, which contains less than 70% of its

original population and only 41.6% of its original geographic area.

The 1997 plan respects the traditional race-neutral districting

criteria identified by the legislature: it divides only two of the State’s

2,217 election precincts (and then only to accommodate peculiar local

characteristics); it divides only 22 of the State’s 100 counties (none

among more than two districts); all of its districts are contiguous, and

itdces not rely on artificial devices like cross-overs and double cross

overs lo achieve that contiguity.” Though the legislature did not

emphasize geographic compactness for its own sake in designing the

1997 plan, its districts are si gnificantly more geographically compact,

judged by standard mathematical measures of geographic

compactness, than their predecessors in the 1992 plan.

The 1997 plan is racially fair, but race for its owa sake was not

the predominant factor in its design or the design of any district

within it. Indeed, 12 of the 17 African-American members of the

House voted against the plan because they believed it did not

adequately take into account the interests of the State’s African-

American residents.

District 12 is one of the six “Democratic” districts estab ished by

the 1997 plan. Seventy-five percent of the district’s registered voters

are Democrats, and at Jeast 62% of them voted for the Democratic

candidate inthe 1988 Court of Appeals election, the 1988 Lieutenant

Governor election, and the 1990 United States Senate election.

District 12 is not a majority-minority district by any measure: only

46.67% of its total population, 43.36% of its vot ing age population,

' In contrest, the 1992 plan this Count invalidated 1 Shaw 1 civided 8) precincts;

divided 44 of the State’s 100 counties {scver of them among three different

districis); and zchieved com iguity only through artificial devices

5

and 46% of its registered voter population is African-American.’

While it does rely on the strong demonstrated support of African-

American voters for Democratic candidates to cement its status as one

of the six Democratic districts, partisan election data, not race, was

the predominant basis for assigning those voters to the district.

District 12 respects the traditional race-neutral redistricting

criteria identified by the legislature. Jt divides only one precinct (a

precinct that is divided in all Jocal districting plans as well}: it

includes parts of only six counties; and it achieves contiguity without

relying on actificial devices like cross-overs and double cross-overs. *

It creates a community of voters defined by shared interests other than

race, joining together citizens with similar needs and interests in the

urban and industrialized areas around the interstate highways that

connect Charlotte and the Piedmont Urban Triad. Of the 12 districts

in the 1997 plan, it has the third shortest travel time (1.67 hours) and

the third shortest distance (95 miles) between its farthest points,

making it highly accessible for a congressional representative. District

12 is significantly more geographically compact than its 1992

predecessor.

District 1 is another of the six “Democratic” districts established

by the 1997 plan. Unlike District 12, District 1 is a majority-minority

district by one measure: 50.27% of its total population is A frican-

American. Like District 12, District | respects the traditional race-

neutral redistricting criteria identified by the legislature. It contains no

divided precincts; it divides only 10 counties; and it achieves

contiguity without relying on artificial devices like cross-overs and

' 11 contrast, 56.63% of the total population, 53.34% of the voting age

pepulation. and 53.54% of the registered voter population of District 12 in the 1992

plan was African-American

' In contrast, District 12 in the 1992 plan divided 48 precmds; included parts of

ten counties; and achieved contiguity only through artificial devices.

P

R

G

E

.

84

98

3

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

18

53

1}

r

88

J

U

L

22

P.

10

/2

2

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

QF

C

50

JU

L-

22

-9

8

WE

D

11

6

double cross-overs.® It creates a community of voters defined by

shared interests other than race, joining together citizens with similar

needs and interests in the mostly rural and economical y depressed

counties in the State's northern and central Coastal Plain.

Because 40 of Narth Carolina’s 100 counties are subject to the

preclearance requirements of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the

legislature submitted the 1997 plan to the United States Department

of Justice for preclearance. The Department precleared the plan an

Jupe 9, 1997.

C. LEGAL CHALLENGES TO THE 1997 PLAN.

I. The Remedial Proceedings in Shaw.

Equal protection challenges to the 1997 plan were first raised in

the remedial phase of the Shaw litigation, when the State submitted

the plan to the three-judge court to determine whether it cured the

constitutional defects in the earlier plan. Two of (he plaintiffs who

challenge the 1997 plan in the instant case -- Martin Cromartie and

Thomas Chandler Muse -- participated as parties plaintiff in that

remedial proceeding, represented by the same attomey who represents

them in this case, Robinson Everett $

In that proceeding, Cromartie, Muse, and their co-plaintiffs (“the

Shaw plaintiffs”) were given an opportunity to litigate any

constitutional challenges they might have to the 1997 plan, a plan

which the State had enacted under the Shaw court’s injunction, as a

* In contrast, District | in the 1992 plan split 25 precincts and 20 countizs, and

achieved contiguity only through artificial devices.

The original phaintifls in Shaw were five residents of District 12 as it existed

under the 1992 plan. On remand from this Court's decision in Shaw H, Cromartie

and Muse sought and obtained the district cotrt's leave to join them as plainifTs, in

order to assert a claim that District | in the 1992 plan was an unconstitutional rzcizl

gemrymandzr -- a claim which this Court had just held thst the original Shaw

plaintiffs Iscked standing to assent.

-

™

O

T

A

T

Y

e

m

7

proposed remedy for the plan this Court had Just Ceclared

unconstitutional.” They elected not to avail themselves of thal

opportunity. They did inform the Shay court that they believed the

1997 plan to be “unconstitutional” because Districts ) and 12 -- the

same districts they now challenge in this zction -- had been “racially

gerrymandered.” App. 183a- 186a. At the same time, however, they

asked the court not to decide their constitutional challenges to the

proposed remedial plan. The reasonthey gave was someschat curious:

that the court lacked authorily to entertain these claims, because none

of them had standing fo challenge tlie proposed plan under United

States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (1995).* For this reason, they asked the

court “not [to] approve or otherwise rule on the validity of” the new

plan, and to “dismiss this action without prejudice to the right of any

person having standing to maintain a separate action attack ing [its]

censtitutionality.”” App. 186a. The state defendants actively opposed

phaintiffs’ effort to reserve their constitutional challenges to the 1997

plan for 2 new lawsuit.

The three-judge court rejected the Shaw plaintiffs’ argument that

it lacked jurisdiction lo entertain their constitutional challenges to the

State’s proposed remedial plan. App. 166a-168a. The court then went

? App. 181a-182a (directing the Shaw plantif)s to advis: the court “wheter they

ended] to clair that the [1997] plan should not be approved by the court becaise

it does not cure the constitutional dzfests in the former plaa™ and, if so, ‘to identify

the basis for that claim”).

* App. 186a (“Because of the lack of starding of the Plaintiffs. there appears fo

be no matter at issue before this Coun with respect 10 the ney redistricting plan)

The Shaw: plaintiffs kased this aiguiment on the assertion that none of them resided

in the redrawn District 12. Apa. 185a-186a. The argument was somewhat

disigenvous, for at least two of their number -- Cromartie and Muse -- resided in

the redrawn District | and thus Fad standing te assert a racial gemymaidering

chatlenge to the 1997 plan, cven urder their own bizarre reading of the Hays

cecision.

P

A

G

E

.

Q

1

0

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

:

5

3

*’

88

J

U

L

22

P3

12

2

20

26

82

13

12

FA

X

NO

.

i

DC

OF

C

JU

L-

22

-9

8

WE

D

11

:5

0

8

on to rule that the plan was “in conformity with constitutional

requirements” and that it was an adequate remedy for the

constitutional defects in the prior plan “as to the plaintiffs and

plaintiff-intervenors in this case.” App. 160a, 167a. On that basis, the

court entered an order approving the plan and authorizing the state

defendants to procesd with congressional elections under it. App.

157a-158a. The Shaw plaintiffs took no appeal from that order.

2. The Parallel Cromartie Litigation.

Having forgone an opportunity to litigate their constitutional

challenges to Districts 1 and 12 in the 1997 plan before the three-

judge court in Shaw, Cromartie and Muse immediately sought to have

those same claims adjudicated by a different three-judge court. They

did so by amending a complaint in a separate lawsuit they had

previously filed against the same defendants, a lawsuit in which they

were also being represenied by Robinson Everett. In that amended

complaint, Cromartie, Muse, and four persons who had not been

named as plaintiffs in Shaw (“the Cromariie plaintiffs”) asserted

racial gerrymandering challenges fo Districts 1 and 12 in the 1997

plan, the very plan the th ree-judge court in Shaw had just approved

over their objection.

On January 15, 1998, the Cromartie case was assigned to a three-

Judge panel, consisting of one Judge who had served on the three-

judge pauel in Shaw -- Judge Voorhees, who had dissented from the

panel’s decisions ir Shaw I and Shaw 71 -- and two new judges. On

January 30, 1998, the Cromartie plaintiffs moved for a preliminary

injunction halting all further elections under the 1997 plan. Several

days lates, they also moved for summery judgment. The state

defendants responded with a cross-motion for summary judgment.

On March 31, 1998, before it had permitted either party (o

conduct any discovery, the three-judge court heard brief oral

arguments on the pending motions for preliminary injunction and

summary judgment. Three days later, the court, with Circuit Jud ge

9

Sam J. Ervin, 111, dissenting, entered an order graating the Cromartie

plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment, declaring District 12 in the

1997 plan unconstitutional, and permanently enjoining the state

defendants from conducting any elections under the 1997 plan.* The

court’s order did not explain the basis for ifs decision, stating only

that “[m Jerzoranda with reference to [the] order will be issued as soon

as possible.” App. 45a-46a.

The state defendants immediate! y noticed an appeal to this Court.

Since the elections process under the 1997 plan was already in {ull

swing, they asked the district court to stay its Apri! 3rd order pending

disposition of that appeal. The district court declined to do so. The

state defendants then applied to Chizf Justice Rehnquist for a stay of

the same order. The Chief Justice referred that application to the full

Coart, which denied it on April 13, 1998, with Justices Stevens,

Gmsbuirg, and Breyer dissenting. When this Court acted on that stay

application, the district court had yet to issue an opinion explaining

the order and permanent injunction in question.

D. THE THREE-JUDGE DISTRICT COURT'S OPINION.

On April 14, 1998, the three-judge court issued an opinion

explaining the basis for its order of April 3, 1998. Al the outset, the

court ruled that “the September 12, 1997, decision of the Shaw three-

judge panel was not preclusive of the instant cause of action, as the

panel was no! presented with a continuing challenge to the

redistricting plan.” App. 3a-4a. The court then held that (he

Cromartie plaintiffs were entitled to summary judgment on their

challenge to District 12, because the “uncontroverted material facts”

The order made no reference © District |. though the Cromartie phaintifis also

had moved for Summary judgment on their claim that it was an unconstitulional

racial garrymander. Not uatil ths memorandum opinion was filed ca Apel 14, 1998,

did the court explain that it was dznying summery judgmert as to Distiic |. App.

2232-23a_ 53a.

P

R

G

E

.

Q

1

1

2

8

2

8

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

4

:

5

4

’

8

s

J

U

L

22

20

26

82

13

12

FA

X

NO,

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

50

4

-—tt

0)

88)

=

a

ii

\

Q

=

a,

2

d-

ON

NN

(QN}

0

10

established tha the legislature had “utilized race as the predominant

factor in drawing the District” App. 21a-22a. Unlike the lower courts

whose “predominance” findings this Court upheld in Miller, Bush,

and Shaw 11, the court did not base this finding on any direct evidence

of legislative motivation: instead, it relied wholly on an inference it

drew from the district’s shape and racial demographics. The court

reasoned that District |2 was “unusually shaped,” that it was “still the

most geographically scattered” of the State’s congressional districts,

that its dispersion and perimeter compactness measures were lower

than the mean for the 12 districts in the plan, that it “include[s) nearly

all of the precincts with African-American population proportions of

over forty percent which lie between Charlotte and Greensboro,” and

that when it splits cities and cou nties, it does so “along racial lines.”

The court concluded that these “facts,” which it characterized as

“uncontroverted,” established -- as a matter of law -- that the

legislature had “disregarded traditional districting criteria” and

“utilized race as the predominant factor” in designing District 12.

App. 192-223.

Finally, the court held that the Cromariie plaintiffs were not

entitled to summary judgment on their challenge to District 1, the

only majority-minority district in the 1997 plan. The court did not

explain the basis for this holding, except to say that the Cromartie

plaintiffs had “failed to establish that there are no contested material

issues of fact that would entitle [them] to judgment as a matter of law

as to District 1.” App. 22a. In denying the state defendants’ cross-

motion for summary judgment on the same claim, however, the court

stated that the “contested material issue of fact” concerned “the use

of race asthe predominant factor in the districting of Disirict 1.” App.

23a.

Judge Ervin dissented. App. 25a. In his view, the majority’s

conclusion that the evidence in the summary judgment record was

sufficient to establish -- as a matter of law -- that race had been the

predominant factor in the design of District 12, was strikingly

11

inconsistent with its conclusion thal the same evidence was nol

sufficient to establish that race had been the predominant factor in the

design of District 1, given that the two districts were drawn by the

same legislators, at the same time, as part of the same state-wide

redistricting process. The Inconsistency was even more striking, he

noted, “when cne considers that the legislature placed more African-

Americans in District | . . . than in District 12.” App. 38a.

E. THE 1998 INTERIM PLAN.

On April 21, 1998, the court entered an order allowing the

General Assembly 30 days to redraw the State's congressional

redistricting plan to correct the defects it had found in the 1997 plan.

App. 55a. On May 21, 1998, the General Assembly by bipartisan

vote enacted another congressional redistricting plan, 1998 Session

Laws, Chapter 2 (“the 1998 plan”), and submitted it to the court for

approval. The 1998 plan is effective for the 1998 and 2000 elections

unless this Court reverses the district court decision holding the 1997

plan unconstitutional.” The Department of Justice precleared the

1998 plan on June 8, 1998.

On June 22, 1998, the district court entered an order tentatively

approving the 1998 plan and authorizing the State to pioceed with the

1998 elections under it. App. 175a-i80a. The court explained that

the plan's revisions to District 12 “successfully addressed” the

concems the court had identified in its April 14, 1998 opinion, and

that it appeared, “from the record now before [the court),” that race

had not been the predominant factor in the design of that revised

district. The court noted that it was not ruling on the constitutionality

of revised District |, and i directed the parties to prepare for trial on

" See 1998 N.C. Sess Laws, ch. 2, § LJ (“The plan adopted by this act is fective

for the clections for the years 1998 and 20C0 unless the United States Supreme

Court reverses the decision holding vnconstiltional G.S. 163-201(a) as it existed

prior ‘0 the cmactuiead of this act”).

P

R

G

E

.

B

1

2

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

5

4

11

8

8

JU

L

22

J

BY

NN

on

a.

20

26

82

13

12

FA

X

NO

.

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

:

LO 2

—

[am

[1]

=

a0

2

|

od

ey

=

=

HE 4

12

that issue. It also “reserve[d] jurisdiction” to reconsider its ruling on

the conslitutionality of redrawn District 12 “should new evidence

emerge.” App. 1772a-179a.

ARGUMENT

I. SUMMARY JUDGMENT ISSUE.

The district court's application of the Rule 56 summary judgmen|

standard in this context presents substantial questions that warrant

either plenary consideration or summary reversal.

The threshold inquiry for deciding whether a district is subject to

strict scrutiny under Shan, turning as it does on the actual motivaticns

of the state legislators who designed and enacted the plan, is

peculiarly inappropriate for resolution on summary judgment. This

Court has repeatedly affirmed its “reluctance to attribute

unconstitutional motives to the states.” Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S.

388,394 (1983). When a federal court is called upon to judge the

constitutionality of an act of a state legislature, it must “presume” that

the legislature “actfed] in a constitutional manner,” Minois v. Krudl,

480 U.S. 340, 351 (1987); see McDonald v. Board of Election

Comm rs of Chicago, 394 U.S. 802, 809 ( 1969), and remember that

it “is not exercising a primary judgment but is sitting in judgment

upon those who also have taken the oath to observe the Constitution.”

Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57, 64 (1981) (intemal quotation

omitted). In Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1999), this Court made

clear that these cautionary principles are fully applicable in Shaw

cases. See 515 U.S. at9)5 (“Although race-based decisionmaking is

inherently suspect, until a claimant makes 2 showing sufficient to

support that allegation, the good faith of a state legislature must be

presumed.” (citations omitted). Indeed, they have even greater force

in Shaw cases, given the sensitive and highly political nature of the

redistricting process and the “serious intrusion” on state soverei gnty

that federal court review of state districting legislation represents. 515

13

U.S. at 916 (admonishing lower courts to exercise “extraordinary

caution” in adjudicating Shaw claims) (emphasis added).

[gnoring this Court’s directives, and oblivious to the fact that the

invalidation of a sovereign state’s duly-enacted electoral districting

plan is nol a casual matter, the court below resolved the contested

issue of racial motivation -- and with it, the issue of the planr’s validity

-- on summary judgment. On the basis of a brief hearing, at which it

heard no live evidence but merely argument from counsel it

concluded that plaintiffs had established -- as a matter of law -- that

race had been the predominant factor in the construction of District

12. App. 21a-22a. In so doing, it committed clear and manifest error.

The district court’sdecision is flatly inconsistent with this Court’s

decision in Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986).

There, this Court made clear that a motion for summary judgment

must be resolved by reference to the evidentiary burdens that would

apply at trial. Jd. at 250-54. Where, as here, the party who seeks

summary judgment will have the burden of persuasion at trial, he can

obtain summary judgment only by showing that the evidence in the

summary judgment record is such that no reasonable factfinder

hearing that evidence at trial could possibly fail to find for him. Jd at

252-55. In other words, he must demonstrate that the evidence,

viewed in the light most favorable to his opponent, is “so one-sided"

that he would be entitled to judgment as a matter of law at trial. 7d, at

249-52.

tn this case, plaintiffs hed the burden of persuasion at trial on the

predominance issue. Miller, 515 U.S. at 916. The district court utterly

ignared this critical fact in concluding that they were entitled to

summary judgment on their claim challenging the constitutionality of

District 12. Indeed, the court appeared fo be analyzing their motion

for summary judgment under the standard that applies to parties who

will nor have the burden of persuasion at trial. App. 2)a (citing

Celotex Corp. v. Calrett,477 U.S. 317, 324 (1986)).

P

R

A

G

E

.

B

1

3

2

0

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

:

5

4

’

8

8

J

U

L

22

P.

14

/2

2

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

.

DC

OF

C

51 2 =

—)

88)

=

a0

(©)

|

oJ

=

oD

Fi

14

Had the district court applied the standard this Court's precedents

direct it to apply, it could rot have justified the conclusion that

plaintiffs were entitled to summary judgment on their claim

challenging the constitutionality of District 12. To obtain summary

Judgment on that claim under Liberty Lobby, plainliffs were required

to show that no reasonable finder of fact, viewing the evidence in tke

summary judgment record in the light most favorable to the state

defendants, could possibly find that race had nor been the

predominant factor in its design. 477 U.S. at 252-55. The only

evidence in the record tending to show that race had been the

predominant motivation in the construction of District 12 was an

inference the plaintiffs asked the court to draw from their evidence of

the district's shape and racial demographics.’ There was absolutely

no directevidence" of such an improper motivation before the district

court: no concessions to that effect from the state defendants, and no

evidence of statements to that effect in the legislation itself, the

committee hearings, the committee reports, the floor debates, the

State’s § 5 submissions, or the post-enactment statements of those

who participated in the drafting or enactment of the plan. Compare

'" Plaintiffs presented various maps and demographic data as well as the aflidevils

of several experts who relied on the same evidence of shape and recial demographics

to opine that race was the predominant factor used by the State to draw the

boundaries of the ccngressiona! districts. Such postenaciment testimony of eutside

experts “is of litle use” in determining the legislalure’s purpose in enacting a

particular statute, wher: none of those experts “participated in or contributed to he

enactment of the law or its implementation.” Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578,

395-96 (1987).

While the distinction between “direct” and “circumstantial” evidence is “olten

subtle and difficult,” Price Waterhouse v. Hepkins, 490 U.S. 228, 291 (1989)

(Kennedy, J., dissenting), most courts define “direct evidence” of motivation as

“conduct or siztements by persens involved in the decisionmaking process (hat may

be viewed as directly reflecting the alleged [motivation].” Starcesti v Wesiinghouse

Elec. Cocp., S4 F.3d 1089. 1096 (3d Cir. 1993)

15

Miller, 515 U.S. at 918; Bush v. Vera, S17 U.S 952, 959-62, 969-7 |

(1996) (plur. op.); Shaw II, 517 US. at 906. This evidence was

legally insufficient, even if uncontradicted, to permit a reasopable

finder of fact to conclude that plaintiffs had discharged their burden

of persuasion on the predotninance issue. A court must “look further

than a map” to conclude that race was a state legislature’s

predominant consideration in drawing district lines as amatier of law.

Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529, 1565 (1995) (Hatchet, :.,

dissenting)."”

By contrast, the summary judgment record contained substantial

direct evidence that mce had ros been the predominant factor in the

design of District 12. This evidence consisted of affidavits from the

legislators who headed the legislative committees that drew the 1997

plan and shepherded it through the General Assembly. See App. 69a-

84a. These legislators testified under oath that they and their

colleagues were well aware, when they designed and passed the 1997

plan, of the constitutional limitations imposed by this Court's

decisions in Shaw /and its progeny, and that they took pains to ensure

that the plan did not run afoul of those limitations. They also testified

under cath that the boundaries of District 12 in the plan had been

motivated predominantly by partisan political concerns and other

legitimate race-neutral districting considerations, rather than by racial

considerations. At the summary judgment stage, the district court was

obligated to accept this testimony as truthful. See Liberty Lobby, 477

U.S. at 255 (“The evidence of the nonmovant is to be believed, and

all justifiable inferences are to be drawn in his favor.”). The district

courtdid precisely the opposite: it assumed that these state legislators

had lied under oath about the factors that motivated them in drawing

® While the combination of a map and racial demographics may, uncer certain

extraordinary circumstances, be wilicien! 0 state 2 claim "hat rice was the

predominant factor in a district's design, see Shaw J, there is a vast dificrence

between stating a claim and proving it

P

R

G

E

.

B

1

4

2

0

2

5

8

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

]

:

5

5

’

8

8

J

U

L

22

P,

15

/2

2

21

2

20

26

82

1

FA

X

NO

.

W

e

DC

OF

C

(QN

LO)

-——

6

=

[1]

=

a0

(@p]

|

od

is

—

>

Gg

16

the lines of District 12. That assumption was one this Court's

precedents simply did nct permit it to make at this stage of the

litigation. See id.; Miller, S15 U.S. at 915.16.

The district court's application of the Rule 56 standard was so

irregular that summary reversal is warranted, even if this Court

concludes that the case does not present issues warranting plenary

consideration. “Striking down a Jaw approved by the democratically

elected representatives of the people is no minor matter,” and this

Court’s precedents do not pemit it do be done “on the gallop.”

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578, 626, 61) (1987) (Scalia, J.,

dissenting).

Ii. PRECLUSION ISSUE.

This case also raises important issues concerning the effect of a

final judgment from a court of competent jurisdiction holding a state's

proposed redistricting plan constitutional on the ability of the parties

to that judgment and their privies to challenge the same plan again in

a later lawsuit before a different court.

Two of the plaintiffs herein -- Cromartie and Muse — participated

as parties plaintiff in the remedial proceedings in Shaw. In those

proceedings, the court offered them a full and fair opportunity to

litigate any constitutional challenges they might have to the 1997

pan, which the State had proposed as a remedy for the constitutional

defects found in the earlier plan. They elected not to avail themselves

of that opportunity, and the Shaw cour: entered a final judgment

finding the plan constitutional and authorizing the State to proceed

with elections under it. Under elementary principles of claim

preclusion, that final judgment extinguished any and all claims

Cromartie and Muse had with respect to the validity of the 1997 plan,

including the claim they now assert in this action, which challenges

the plan's District | as a racial gemymander. That Cromartie and

Muse elected not to assert thal particular claim in Shaw will net save

it from preclusion here; indeed, the very purpose of the doctrine of

17

claim preclusion is to prevent plaintiffs from engaging in this sort of

strategic claim-splitting.

The final judgment entered in Shaw also bars the claim plaintiffs

Evereti, Froelich, Linville, and Hardaway assert in this action, which

challenges the 1997 plan’s District 12 as a racial gerrymander.

Though these individuals were not formally named as parties in Say,

they are bound by the final judgment entered in that case because

their interests were so closely aligned with those of the Shaw

plaintiffs asto make the Shaw plaintiffs their “virtval representatives”

in that earlier action."

Ignoring fundamental principles of claim preclusion, the district

court held that the final judgment entered in Shaw did not bar the

claims appellants assert here. App. 3a-4a. The court based this

conclusion on its understanding that the Shaw court “was not

presented with a continuing challenge to the redistricting plan.” App.

4a. To the extent the court meant that the Shaw court did not resolve

'* A party may be bound by a prior judgment. even though he was net formally

named as a panty in that prior astion, when his interests wesc closely aligned with

those of a parly to the prior aclion and there are olher indicia that the party was

serving as the non-party's “virtual represertative” in the prior action. See Ahmg v.

Allsteel, Inc., 96 F.3d 1033, 1037 (7th Cir. 1996), Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A. v.

Celatex Corp., S6 F.1d 34), 345.46 (2d Cir. 1995); Gorzalez v. Bance Cent Corp.,

27 F.3d 751,761 (1st Cir. 1994%, Nordhorn v. Ladish Co., 9 F.3d 1402, 1405 (91h

Cir. 1993). Royal Ins. Co. of Ar. v. Quinn-L Capital Corp, 960 F.2d 1286, 1297

(54k: Cir. 1992), Jaffree v. Wallace, 837 F.2d 1461. 1467-58 (11th Cir. 1988). The

relationship between the Shaw plaintifls and the four plaintiffs who challange

District 12 in this acton has many of the classic indicia of “virtual representation’:

close relationships between the parties and the monparties, shared counsel.

simultaneous tigation seeking th: syme tase telizf under the same basic icgal

theory. and spparent laciical maneuvering to avoid preclusion See Jaffree, 837 F.2d

a 1467.

P

R

G

E

.

Q

1

5

S

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

5

S

'

8

8

J

U

L

+2

2

(QV)

oJ

bis

wo

x. Bl

FA

X

NO,

a

}

n

e

DC

OF

C

52

:

l aul

ais

Lr]

=

a

(®3/

|

J

—al

es

ro

18

the issue of the 1997 plan’s constitationality, it was mistaken." To the

extent the court meant only that the Shaw plaintiffs chose to assert no

challenge to the 1997 plan in those earlier proceedings, it missed the

central point of the doctrine of claim preclusion, which bars claims

that were or could have been biought in the prior proceedings. The

district court’s holding on the preclusion issue presents substantial

questions warranting either plenary consideration or summary

reversal.

The district court’s decision conflicts directly with this Court's

cases defining the preclusive effect of a prior federal judgment. As

those decisions make plain, when a federal court enters a final

judgment, that judgment stands as an “absolute bar” to a subsequent

action concerning the same “claim or demand” between the same

parties and those in privity with them, “not only as to every matter

which was offered and received to sustain or defeat the claim or

demand, but [also] as to any other admissible matter which might

have been offered for that purpose.” Cromwell v». County of Sac, 94

U.S. 351, 352 (1876).

The district court’s decision also conflicts with Federated Dep't

Stores, Inc. v. Moitie, 452 U.S. 394 (1981). In that case, this Court

The Shaw count did not expressly reserve the clsims in qiestion for resolution

in a laler proceeding Though the Shaw phaintifis esked it Io “digniss the action

without prejudice to the right of any person having standing to bring a new action

attacking the constitutionality of the [1997] plan,” App. |86a, the court declined fo

de se. While the coun s:ated tha! its apptoval of the plan was necessarily “limited

by the dimensions of this civil action as that is ¢efined by the panties and the claims

properly before us.” and that it therefore did not “run beyond the plan's remedial

adequacy with tespect to those parties,” it specifically held tae plan constitutional

"as to the plaintifis . . _ io this case.” App. 1672, 1602. The only claim tte court

dismissed “without prejudice” was “the claim added by amendment to she complaint

in this action on July 12, 1996,” in which the Shaw plaintiffs “challenged on ‘racial

gerrymandering” grounds the creation of former congressional District 1.” App.

1582. (emphasis edded.) As the court recognized, this claim was mooted hy its

approval of the 1997 plan. App. 1652, 168a.

19

made clear thal a federal ccurt may not refuse to apply the doctrine of

claim preclusion simply because it believes the prior judgment to be

wrong. Id. at 398. As this Court explained, the doctrine of claim

preclusion serves “vital public interests beyond any individual judge's

ad hoc determination of the equities in a particular case,” including

the interest in bringing disputes to an end, in conserving scarce

Judicial resources, in protecting defendants from the expense and

vexat:on of multiple duplicative lawsuits, and in encouraging reliance

on the court system by minimizing the possibility of inconsistent

judgments. Id. at 401. The district court’s decision here -- a

transparent attempt to correct a perceived error in an earlie: judgment

that the Josing party failed to appeal — flies in the face of this bedrock

principle of our civil justice system.

The policies behind the doctrine of claim preclusion are at their

most compelling when the claims in question seek to interfere with a

state’s electoral processes. The strong public interest in the orderly

administration of the nation’s electoral machinery requires efficient

and decisive resolution of any disputes regarding these matters." In

this case, the district court’s disregard of basic principles of claim

preclusion has resulted in the entry of two dramatically inconsistent

* In 2ddition, the district court's decision conflicts, at least in princisle, vith th:

decisions of at least six federal circuit courts applying the “virtual represen ation”

theory of privity. See cases cited supra note 14. This conflict is illusirat:ve of the

widespread corfusion in the lower federal courts as w the proper scope of the

“virtual representation” doctrine. See 18 JAnES Wa. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE'S

FEDIRAL PRACTICE § 131.40{3][c][1|[B] (3d ed. 1997) (collecting cases); 8

C. WRIGHT, ET AL., FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCECURE § 4457 (1981) (same).

Preciszly for this reason, Congress has provided for a right ef direct appeal to

this Court from any order of 8 three-judge count grantirg er denying a request fo:

injunctive relief in any civil action challenging the constiwtionality of the

apportionment of congrzssional districts or the zpportiomment of any staievwide

legislative body. Sze 28 U.S.C. § 1253; 28 U.S.C. § 2234(a).

P

R

G

E

.

Q

1

6

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

:

5

6

11

»

88

JU

L.

22

(QN]

[QV]

DN

[S~—

=

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

53

e &

ae

68)

=

a

>

QV

—

=

—_—

20

judgments -- one ordering the State to go forward with its

congressional elections under the 1997 plan and the other enjoining

it from doing so -- which have left the State's electoral Erocess in

disarray. It has significantly prolonged final resolution of the legal

controversy over the constitutionality of North Carolina’s

congressional districts, wasting judicial resources, diverting the state

legislature from the business of governing, and causing the State’s

taxpayers to incur significant additional expense. it is difficult to

imagine a greater affiont to the policies behind the doctrine of claim

preclusion, to core principles of state soverei gnty and federalism, and

to the very integrity of the federal system of justice itself.

The district court’s resolution of the preclusion issue is so flally

inconsistent with this Court's precedents that summary reversal is

warranted, even if this Court concludes that the case does not present

issues warranting plenary consideration.

II. PREDOMINANCE ISSUE.

In Shaw 1, this Coun first recognized that a faciall y race-neutral

electoral districting plan could, in certain exceptional circumstances,

be a “racial classification” that was subject to strict scrutiny under the

equal protection clause. 509 U.S. at 642-44, 646-47, 649. Two years

later, in Miller, this Court set forth the showing required to trigger

strict scrutiny of such a districting plan: “that race for its own sake,

and not other districting principles, was the legislature’s dominant

and controlling rationale in drawing its district lines.” $15 U.S. at

913 (emphasis added). To satisfy this standard, a plaintiff must prove

that the legislature “subordinated traditional race-neutral districting

pricciples . . . 10 racial considerations,” so that race was “the

predominant factor” in the design of the districts. d. at 91 6; see id. at

928-29 (O’Connor, J., concurri ng) (strict scrutiny applies only when

“the State has relied on race in substantial disregard of customary and

traditional [race-neutral] districting practices”)

21

In Miller, this Court recognized that “{flederal count review of

districting legislation represents a serious intrusion on the most vital

of local functions,” that redistricting legislatures are almost always

aware of racial demographics, and that the “distinction between being

aware of racial considerations and being motivated by them” is often

difficult to draw. 515 U.S. at 915-16. For these reasons, this Court

directed the lower courts to “exercise extraordinary caution” in

applying the “predominance” test. Jd. at 916; see id at 928-29

(O’Connor, J., concurring) (stressing that the Miller standard is a

“demanding” one, which subjects only “extreme instances of [racial]

gerrymandering” to strict scrutiny)

In its various opinions in Bush, this Court made clear that proof

that the legislature considered race as a factor in drawing district lines

is not sufficient, without more, to trigger strict scrutiny. See 517 U.S.

at 958 (plur. op.); id. at 993 (O’ Connor, J., concurring); and id. at

999-1003 (Thomas, J., joined by Scalia, J., concurring in Judgment).

Nor is proof that the legislature neglected traditional districting

criteria sufficient to rigger strict scrutiny. See id. at 962 (plur. op.);

id. at 993 (O'Connor, J., concurring); id. at 1000-001 (Thomas, J.

Joined by Scalia, J., concurring in judgment). Instead, strict scrutiny

applies only when the plaintiff establishes both that the State

substantially neglected traditional districting criteria in drawing

district lines, and that it did so predominantly because of racial

considerations. See id. at 962-63 (plur. op.) and at 993-94 (O’Con nor,

J., concurring) (emphasis added). Accord Shaw II, 517 US. at 906-

07; Lawyer v. Justice, [17 S. Ct. 2186, 2194-95 (1997).

In this case, the North Carolina legislature, exercising the State’s

sovereigr right to design its own congressional districts, selected a

number of traditional -- and race-neutral -- districting criteria to be

used in constructing the 1997 plan: contiguity. respect for political

subdivisions, respect for actual communities of interest, preserving

the partisan balance in the State's congressional delegation,

preserving the cares of prior districts, and avoiding contests between

P

R

A

G

E

.

B

1

7

2

8

2

5

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

:

5

6

8

8

J

U

L

22

oJ

(QN]

™

ao

= 9

20

26

82

13

12

FA

X

NO.

"

®

DC

OF

C

bs

rst

ot

fan

1}

=

@

>»

J

2

r=3 Ea

=o

22

incumbents. All of these criteria were ores that this Court had

previously approvedas legitimate districting criteria. "* The legislature

did not, however, select geographic compactness as a criterion to

receive independent emphasis in drawing the plan. The 1997 plan as

drawn does not neglect any of the traditional race-neutral districting

criteria the legislature set out to follow; to the contrary, it substantially

complies with all of them.

The district court nonetheless concluded that the legislature

“disregarded traditional districting criteria” in designing District 12,

because it failed tocomply with two race-neutral districting principles

that it never purported to be following -- specifically, the criteria of

“geographical integrity” and “compactness.” App. 212-22a. The court

believed the legislature’s apparent disregard of these two districting

principles in drawing District 12, together with evidence that the

district “include{s] nearly all of the precincts with African-American

population proportions of over forty percent which lie between

Charlotte and Greensboro,” and that it “bypzsse[s]” certain precincts

with large numbers of registered Democrats, established that race,

rather than partisan political preference, had been the predominant

factor in the design of District 12. App. 19a-2)a. This extreme

misapplication of the threshold test for application of sirict scrutiny

ina case of such importance to the people of North Carolina warrants

plenary review for at least four reasons.

First, the district court’s reliance on District 12’s relative lack of

geographic compactness and geographical integrity was based on a

fundamental misunderstanding of the nature and purpose of the

" See Milles, 515 U.S. at 916 (contiguity, respect for political subdivisions, and

respect for communities defined by shated interests other than race); Gaffney v.

Cumnaings, 412 U.S. 735, 751-54 (1973) (preserving partisan balance’; Karcher v.

Daggetr. 462 U.S. 725, 740 (1983) (preserving the cores of prior disiricls and

avoiding contests between incumbents); Reymolds v Sims, 377 U.S. 53, 580 (1964)

(ensuring “access of citizens to their representalives™).

e

m

D

A

2]

“disregard for traditional districting criteria” aspect of the Miller

test." As this Court has explained repeatedly, a state's deviation from

traditional race-neutral districting criteria is imgortant in this context

only because it may, when coupled with evidence of racial

demographics, serve as “circumstantial evidence” that “race for its

own sake, and not other districting principles, was the legislature’s

dominant and controlling rationale in drawing district lines.” Miller,

515 U.S. at 913; see id. at 914 (“disclose[s] a racial design’), Bust,

517 U.S. at 964 (plur. op.) (“correlstions between racic

demographicsand [irregular] district lines,” if not explained “in terms

of non-racial motivations,” tend to show “that race predominated ip

the drawing of district lines”). The notion is that when a state casts

aside the race-neutral criteria it would normally apply ia districting to

draw a majority-minority district, it is very likely to have done sp for

predominantly racial reasons. For this inquiry to serve its purpose, it

must fecus not on the degree to which the challenged district deviates

from same setofrace-neutral districting principles that a hypothetical

state -- or a federal court -- might find appropriate in desi gninga plan,

but rather on the precise set of race-neutral districting principles that

the particular state would otherwise apply in designing its districts,

™ Indeed, this misunderstanding of the “traditional race-neutral districting criceria™

lo which Miller refers drove the district cou to the otherwise inexplicable

conclusion that plaintiifs had established -- as a mztter of law -- thal race wzs (1e

predominant factor in the desigr: of District 12, bat thal they had rot established --

as a matter of law -- that #t was the predominant factor in the design of District |

App. 17a-22a The evidence thal racial consideratiors Fad played a significant role

wn the line-drawing process sas much stronger with respect to District 1 than to

District 12, for il was urdisputed that District ] is a majoriy-minosity district

enacted to avoid a violation of § 2 of the Votirg Rights Act. The cnly conceivable

explaration for the district coun’s conclusion (hat District 12 was 2 racial

gerrymander as a matier of law, out District I wes not, was its perception that

District | was not as “imegular” as Disirict 12 and had bztier “comparative

compactness indicators” App. i3a-14a.

P

R

G

E

.

Q

1

8

2

8

2

6

8

8

2

1

3

1

2

[i

L

1S

7

’

8

8

J

U

L

22

(QN]

J

NN

(@>]

as

20

26

82

13

12

FA

X

NO.

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

54

: ”

A

[1)

=

0

:

od

3

=

=

i

24

were it not pursuing a covert racial objective. See Quilter v.

Voinovich, 98) F. Supp. 1032, 1045 5.10 (N.D. Ohio 1997). aff d

118 S. C1. 1358 (1998) (characterizing the inquiry as “designed to

identify situations in which states have negjected the criteria they

would otherwise consider in pursuit of race-based objectives”).

[n this case, the district court evaluated District 12s compliance

with traditional race-reutral districting criteria by reference to two

such criteria that the people of North Carolina have mor required their

legislature to observe in districting: “geographic compactness” and

“geographical integrity.” In so doing, tke district court apparently

relied on this Court's frequent references to compactness as a

traditional race-neutral districting criteria. See, e.g., Shaw I, 509 U.S.

al 647; Miller, 515 U.S. at 916; Bush, $17 U.S. at 959-66 (plur. op.).

But this Court has never indicated that the race-neutral districting

criteria it has mentioned in its opinions are anything but illustrations.

See, e.g., Miller, 515 U.S. at 916 (describing “traditional race-neutral

districting principles” as “including buf not limited to compactness,

contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions or communities

defined by actual shared interests”) (emphasis added). Nor has this

Court ever indicated that a state's deviation from abstract numerical

measures of compactness has any probative value whatsoever when

the state in question does nos have a stated goal of drawing compact

districts ?°

* Indeed, this Court's recent decision in Lawyer suggests precisely the opposite.

In Lawyer, the plaintiffs presented evidence that the challenged state legisiative

district encompassed more than one county, crossed a body of water, was irregular

in shape, and lacked geographic compactness. 117 S. Ct. at 2195. The disirict court

found this evidence insufiicient to esablish that raditional districiing principles bad

bezn subordinated © race in the districl’s design, because these were all “common

characteristics of Florida legislative districts, being produds of tke State's

geography and the fact that 40 Senate districts are superimposed on 67 counties.”

ld. (emphasis added). This Court upheld that finéing, on the ground that the

“unrefuted ev.deice shows] that on each of these points Disuict 21 is no different

cvide

of pc

op.)

draw

there

(Sten

from »

id. (er

12] Ti

Shaw

perha;

Sabor

not wi

25

The district court’s decision effectively requires all states with

racially-mixed populations to com ply with “objective” standards of

geographic compaciness in drawing their congressional and

legislative districts. Such a requirement is flatly inconsistent witk this

Coun’s repeated statements that geographic compactness is not a

constitutionally-inandated districting principle. See Bush, 5: 7US. at

962 (plur. op.); Shaw, S09 U.S. at 647. It also conflicts direct ly with

this Court’s long-standing recognition that the Constitution accords

the states wide-ranging discretion to design their congressional and

legislative districts as they see fit, so long as they remain within

constitutional bounds. See Quilter, S07 U.S. 156; Wise v. Lipscomb,

437 U.S. 535. 539 (1978). Surely this means that the states are

enlitied todecide which particularrace-neutral districting criteria they

will emphasize in drawing their districts, without worrying that strict

scrutiny will apply if a federal judge disagrees with their choices.’

Second, the district court’s decision conflicts directly with this

Court’s decision in Bush. There, a majority of this Court made clear

that a district is not subject to strict scrutiny simply because there is

some correlation between its lines and racial demographics if the

cvidence establishes that those lines were in fact drawn on the basis

of political voting preference, rather than race. 517 U.S. at 968 (plur.

op.) (“If district lines merely correlate with race because they are

drawn on the basis of political affiliation, which correlates with nce,

there is no racial classification to justify”); see id. at 1027-32

(Stevens, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting); id. at

frore wha: Florida's waditiond diswicting principles could be expected to produce.

Id. (erophasis added).

n This is not to suggest, of course, that a stzte could avoid the drict scrutiny of

Shave an Millzr simply by choosing to establish “mininal or vague criteria (or

perhaps none at all)” so that “i could never be found io have neglected or

ssbordinated those criteria to race.” Quilier. 98) F. Supp. at (081 n.10. Bu: that is

nol what happencd hzre

P

A

G

E

.

B

1

S

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

:

5

7

*

8

8

J

U

L

22

[QV]

(QV

ISN

ER

[QV]

5 J

20

26

82

13

12

FA

X

NO

.

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

<r

LO . =

=)

[1]

=

£0

(©)

|

od

i

—

—

pe

26

060-61 (Souter, J.. joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting).

Contrary to the district court's suggestion, this is not a situation like

that in Bush, where the state has used race as a proxy for political

characteristics in its political gerrymandering. Instead, the undisputed

evidence in the summary judgment record showed that the State used

political characteristics themselves, not racial data, to draw the lines.

The legislature’s use of such political data to accomplish otherwise

legitimate political gerrymandering will not subject the resulting

district to strict scrutiny, “regardless of its awareness of its racial

implications and regardless of the fact that it does so in the context of

a majority-minority district.” 7d. at 968 (pluc. op.), see id. at 1027-32

(Stevens, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, J)., dissenting); id. at

1060-61 (Souter, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting).

Third, the district court’s decision raises substantial, unresolved

questions conceming the circumstances under which a plaintiff can

satisfy the threshold test for strict scrutiny based solely on an

inference drawn from a district’s shape and racial demographics.

Miller held that a plaintiff can prove the legislature’s predominantly

racial motive with either “circumstantial evidence of a district’s shape

and demographics or more direct evidence going to legislative

purpose.” 515 U.S. at 916. In all of its prior cases finding the

threshold test for strict scrutiny met, however, this Court has relied

heavily on substantial direct evidence of legislative motivation. See

id. at 918 (relying on the State's § S submissions, the testimony of the

individual state officials who drew the plan, and the State’s formal

concession that it had deliberately set out to create majorsity-mirority

districts in order to comply with the Department of Justice's “black

maximization” policy); Bush, 317 U.S. at 959-61, 969-71 (plur. op.)

(same); id. at 1002 & n.2 (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment)

(same), Shaw I7, 517 U.S. at 906 (same). As a result, this Court has

never confronted the question of how much circumstantial evidence

is enough to satisfy the Miller predominance standard, in the absence

{

|

27

of any direct evidence of racial motivation. See Miller, 5135 U.S. at

917 (specifically reserving this issue).

The plaintiffs in this case, unlike those in Miller, Bush, and Shaw

/1, base their claim that race was the predominant factor in the design

of Districts 12 solely on circumstantial evidence of shape and racial

demographics. Yet their circumstantial evidence is decidedly less

powerful than that presented by their counterparts in Miller, Bush,

and Shaw 17. First, and most fundamentally, the district they challenge

is not a majority-minority disirict, as were the districts at issue in

those cases. This Court’s recent decision in Lawyer, which rejected

z claim that a challenged Florida state senate district was a racial

gemrymander, inakes clear that this is an important distinction. 117 S.

Ct. at 2191, 2195 (emphasizing that the challenged district was not

majority-black and noting that “similar racial composition of different

political districts” is not “necessary to avoid an inference of racial

gemymandering in any one of them.”). In addition, the shape of the

district challenged here, though somewhat irregular, does not reveal

“substantial” disregard for tradilional race-neutral districting

principles? Finally, the undisputed evidence here established that the

racial data the legislature used in designing these districts was no

more detailed than the other demcgraphic data it used. Compare

Bush, 517 U.S. at 962-67, 969-71, 975-76 (plur. op.) (finding

"2 In sharp contrast 10 former District 12, which this Court invalidated in Shaw I,

current Distiict 12 is contiguous, respects the integrity of political subdivisions to

the exienl reasonably possible, and creates a community of interest defiacd by

criteria other than race. While i hes relatively low dispersion and perireter

compaciness measures, this is insufficient to support a finding that the legislature

“substantially” disregarded tadilional districting ctiteria in designing it, even if

geographic oympactness can be considered one of the State's “wraditional districting

criteria” See Quilter, 981 F. Supp. 2 1048 (expressing “doubt” that a siate’s aeglect

of ore of its many traditional districting criteria “would te sufficient to show the

kind of flzgrant disregard thal would indicate that traditional districting principles

were svberdinaied to racial objectives™).

P

R

G

E

.

22

08

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

1

1

:

5

8

*