Klopper v. State of North Carolina Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Klopper v. State of North Carolina Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1965. 6b339623-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/66c8fd1c-6250-42cd-81cb-08e0ad989cd3/klopper-v-state-of-north-carolina-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

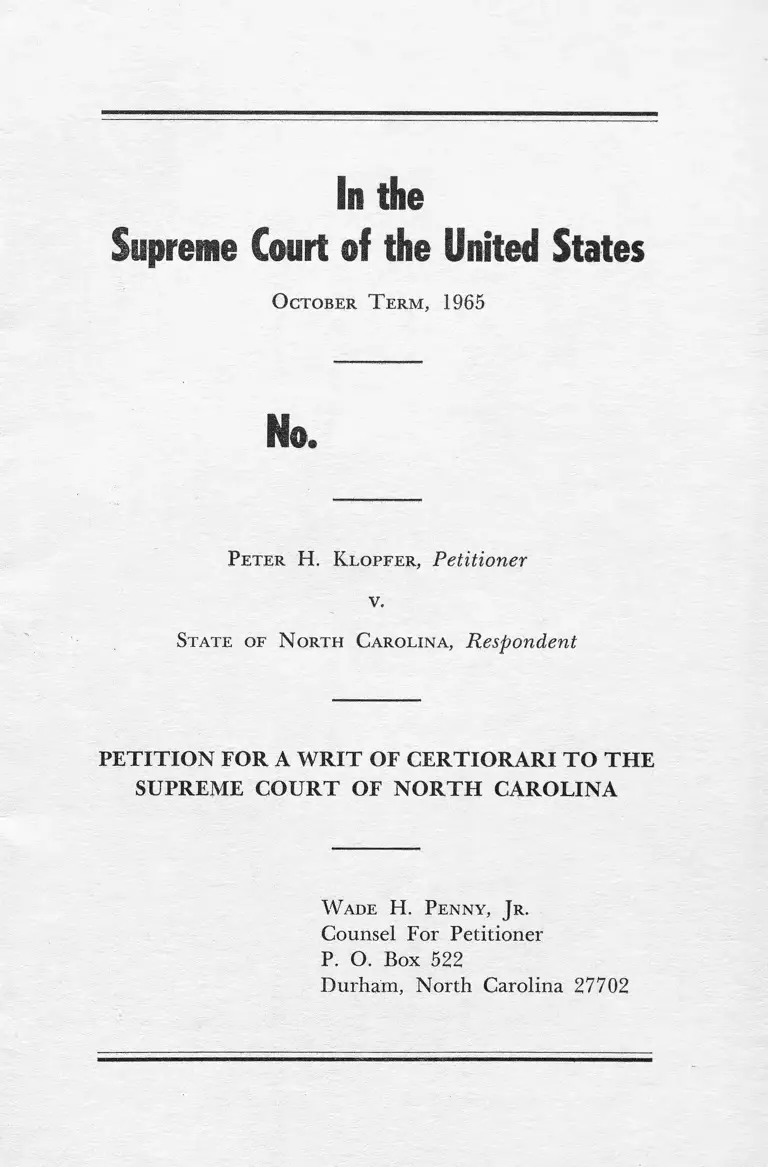

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober T er m , 1965

Pe t e r H. K lo p fe r , Petitioner

v.

Sta te of N orth C arolina , Respondent

P E T IT IO N FO R A W R IT OF C ER TIO R A R I TO T H E

SUPREM E C O U R T OF N O R TH CAROLINA

W ade H. Pen n y , J r .

Counsel For Petitioner

P. O. Box 522

Durham, North Carolina 27702

IN D EX

Page

Citation to Opinion Below .............................................................. 2

Jurisdiction......................................................................................... 2

Question Presented ........................................................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions Involved ................................................ 2

Statement of Case ............................................................................. 3

— How Federal Question Is Presented .................................. 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................................................... 5

Conclusion ......................................................................................... 11

Appendix A — Opinion and Judgment Below ............................ 12

Citations

Cases:

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478, 84 S.Ct. 1758.................... 7

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, 83 S.Ct. 792................... 7

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306, 85 S.Ct. 384......... 3-4

State v. Furmage, 250 N.C. 616, 109 S.E. 2d 563 (1959)........... 6

State v. Williams, 151 N.C. 660, 65 S.E. 908 (1909)................ 6

United States v. Ewell, .....U.S...... , 86 S.Ct. 773...................7, 8-9

United States v. Simmons, 338 F. 2d 804 (2nd Cir. 1964)..... 8

Wilkinson v. Wilkinson, 159 N.C. 265, 74 S.E. 740 (1912).... 6

Statutes:

N.C. Gen. Stat. 15-1 ................................................................... 6

N.C. Gen. Stat. 14-134..................................................................3,6

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

O cto ber T e r m , 1965

Pet er H. K l o p fe r , Petitioner

v.

Sta te of N orth C arolina , Respondent

Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari T o The

Supreme Court Of North Carolina

Peter H. Klopfer, your petitioner, prays that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment of the Supreme

Court of the State of North Carolina entered in the case of

State of North Carolina v. Peter Klopfer on January 14,

1966.

1

2

C IT A T IO N T O OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina,

printed in Appendix A hereto, infra, p.p. 12-14, is reported

in 266 N. C. 349, 145 S. E. 2d 909 (1966).

JU R ISD IC TIO N

The judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

was entered on January 14, 1966, as printed in Appendix

A, infra, p. 15. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U. S. Code, Section 1257 (3).

Q U ESTIO N PRESEN TED

In a State criminal prosecution, does the State deny to

the accused the Constitutional right to a fair and speedy

trial by procedurally suspending the prosecution indefinite

ly over the objection of the accused and without showing

any justification for suspending the prosecution indefi

nitely?

C O N ST ITU T IO N A L PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Constitutional provisions involved are:

(1.) Sixth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution

“ In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall

enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an

impartial jury of the State and district wherein

the crime shall have been committed, which dis

trict shall have been previously ascertained by

law, and to be informed of the nature and cause

of the accusation; to be confronted with the wit

nesses against him; to have compulsory process

for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have

the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.”

3

(2.) Fourteenth A m endm ent to the United States

Constitution

“Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the ju r isd ic t io n

thereof, are citizens of the United States and of

the State wherein they reside. No State shall make

or enforce any law which shall abridge the privi

leges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any State deprive any person of

life, liberty, or property, without due process of

law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.”

STA TE M E N T OF CASE

On Monday, February 24, 1964, the Grand Jury for

the County of Orange, State of North Carolina returned

a Bill of Indictment charging the petitioner, Peter H.

Klopfer, with the criminal offense of trespass in violation

of N. C. Gen. Stat. 14-134. (R. 5-6.)

Klopfer entered a plea of “ Not Guilty” and was placed

on trial in the Superior Court of Orange County in March,

1964. The jury could not agree upon a verdict and a mis

trial was declared with Klopfer being directed to reappear

in court for trial on the following Monday. However,

Klopfer’s case was not retried at that session of court.

(R. 3-4, 6.)

Several weeks prior to the April 1965 Criminal Session

of the Superior Court of Orange County, the Solicitor in

dicated to Klopfer’s attorney his intention to have a nolle

prosequi with leave entered in Klopfer’s case. At the April

1965 Criminal Session, Klopfer through his attorney in

open court opposed the entry of a nolle prosequi with leave.

The defendant’s contention at that time was that the tres

pass charge was abated on the authority of Hamm v. City

4

of Rock Hill 379 U. S. 306, 85 S. Ct. 384, 13 L. Ed. 2d 300

(1964). The Court indicated it approved the entry of a

nolle prosequi with leave in Klopfer’s case. The Solicitor

then stated he did not desire to take a nolle prosequi with

leave in Klopfer’s case and would retain the case in its trial

docket status. Klopfer’s case was continued for the term

at that time. (R. 6-7.)

The trial calendar for the August 1965 Criminal Ses

sion of Orange County Superior Court did not list Klopfer’s

case for trial. T o ascertain the trial status of Klopfer’s case,

a motion was filed expressing his desire to have the trespass

charge pending against him permanently concluded as soon

as reasonably possible. The motion requested the Court

to inquire into the trial status of the charge pending against

Klopfer and to ascertain when his case would be brought

to trial. (R. 7-10.)

The motion filed in Klopfer’s case also set forth the

grounds for Klopfer’s contention that further prosecution

of the trespass charge was barred by the retroactive appli

cation of the 1964 Federal Civil Rights Act on the author

ity of Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, supra. (R. 8-9.)

In response to the foregoing motion, the status of Klop

fer’s case was considered in open court on Monday, August

9, 1965, at the August 1965 Criminal Session of Orange

County Superior Court. The Solicitor then moved the

Court that the State be allowed to take a nolle prosequi

with leave in Klopfer’s case. The motion was allowed by

the Court. (R. 10.)

How Federal Question Is Presented

The petitioner first invoked the Constitutional right

to a fair and speedy trial by his motion that his case be

concluded permanently as soon as reasonably possible.

(R. 7-10.) The Court’s response to the motion was to per

5

mit the entry of a nolle prosequi with leave, to which the

petitioner timely excepted. (R. 10.)

The issue involving the Constitutional right to a fair

and speedy trial was brought forward on appeal by the

petitioner and decided by the Supreme Court of North

Carolina on the basis of the exception and an assignment

of error specifically embodying the issue. (R. 10-11.)

The Supreme Court of North Carolina decided the

Constitutional issue adversely to the petitioner as follows:

“The appellant challenged the right of the solicitor,

even with the approval of the judge, to enter a nolle prose

qui with leave in the criminal prosecution pending against

him in the Superior Court. . . . The reason assigned is that

the procedure denies him his constitutional right of a

speedy trial.”

Appendix A, infra, p. 13

“Without question a defendant has the right to a

speedy trial, if there is to be a trial. However, we do not

understand the defendant has the right to compel the State

to prosecute him if the State’s prosecutor, in his discretion

and with the court’s approval, elects to take a nolle prose

qui.”

Appendix A, infra, p. 14

REASONS FOR G R A N T IN G T H E W RIT

1. The decision of the North Carolina Supreme Court

in State v. Klopfer (Appendix A, infra, p.p. 12-14) permits

the State, by utilization of the procedural device of a nolle

prosequi with leave, to circumvent the accused’s Sixth

Amendment guarantee of a speedy trial as made applicable

to the State by the Fourteenth Amendment.

In North Carolina the entry of a nolle prosequi with

leave in a pending criminal prosecution is customarily left

6

to the initiative and discretion of the Solicitor, subject to

the control of the court. State v. Furmage, 250 N.C. 616,

109 S.E. 2d 563 (1959). The effect of a nolle prosequi

with leave is to discharge the defendant from his bond and

from attending court. The defendant is free to go any

where he chooses without posting a bond to appear in court

at any future time. A nolle prosequi with leave is not an

acquittal. At any time after the entry of a nolle prosequi

with leave, the defendant may be indicted again for the

same offense or the Solicitor, without the necessity of seek

ing the court’s approval, may have the Clerk issue a capias

for the defendant and try him on the original indictment.

In effect, a nolle prosequi with leave reflects the decision

of the Solicitor that he will not “at that time” prosecute the

suit further. Wilkinson v. Wilkinson, 159 N.C. 265, 74

S.E. 740 (1912).

North Carolina Gen. Stat. 15-1 provides for a two-year

statute of limitations within which to institute criminal

prosecution for a general misdemeanor. The offense of

trespass with which Klopfer was charged under N. C. Gen.

Stat. 14-134 is a general misdemeanor. The return of a

bill of indictment charging a misdemeanor arrests the

running of the statute of limitations. Of particular rele

vance to the Klopfer case is the rule in North Carolina that

entry of a nolle prosequi with leave does not start the stat

ute of limitations to running again. State v. Williams, 151

N. C. 660, 65 S.E. 908 (1909).

As the decision in State v. Klopfer (Appendix A, infra,

p.p. 12-14) implies, there is no statute or constitutional pro

vision in North Carolina which requires the Solicitor to

ever bring Klopfer’s case to trial. Equally apparent in the

Klopfer decision is the fact that Klopfer has no means

under North Carolina law to compel the State to give him

his day in court.

7

The most recent pronouncement of this Court relative

to the Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial is in United

States v. Ewell, .....U. S........., 86 S. Ct. 773, 15 L. Ed. 2d

627 (1966), in which the scope and purpose of this Con

stitutional right is stated as follows:

“ This guarantee is an important safeguard to prevent

undue and oppressive incarceration prior to trial, to

minimize anxiety and concern accompanying public

accusation and to limit the possibilities that long delay

will impair the ability of an accused to defend himself.

. . . this Court has consistently been of the view that

‘The right of a speedy trial is necessarily relative. It is

consistent with delays and depends upon circumstances.

It secures rights to a defendant. It does not preclude

the rights of public justice.’ Beavers v. Haubert, 198

U. S. 77, 87, 25 S.Ct. 573, 576, 49 L.Ed. 950. ‘Whether

delay in completing a prosecution amounts to an un

constitutional deprivation of rights depends upon all

the circumstances. . . . The delay must not be pur

poseful or oppressive’, Pollard v. United States, 352

U.S. 354, 361, 77 S.Ct. 481, 486, 1 L. Ed.2d 393. ‘ [T]he

essential ingredient is orderly expedition and not mere

speed.’ Smith v. United States, 360 U.S. 1, 10, 79 S.Ct.

991, 997, 3 L. Ed.2d 1041.” United States v. Ewell, .....

U.S...... , 86 S.Ct. 773, 776, 15 L. Ed.2d 627, 630-31

(1966).

Although the Ewell case, supra, is a federal criminal

prosecution, the affirmative safeguards of the Sixth Amend

ment for an accused have been made applicable to State

criminal prosecutions by inclusion in the Fourteenth

Amendment. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335, 83

S. Ct. 792 (1963) ; Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478, 84 S.

Ct. 1758 (1964). The following four factors appear to be

8

those most relevant to a consideration of whether denial

of speedy trial to an accused has been extended beyond

that period of time reasonably required by the State for the

orderly administration of justice: the length of delay, the

reason for the delay, the prejudice to the defendant and

waiver by the defendant. United States v. Simmons, 338

F. 2d 804 (2nd Cir. 1964).

Applying these four factors for determining the in

fringement of the Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial

to the facts in the Klopfer case, it becomes apparent that

the State of North Carolina can not claim even one of

the four factors. As of August, 1965, when Klopfer’s mo

tion requesting trial or dismissal of his case was denied, al

most eighteen months had elapsed since his indictment.

(R. 5-10) . The decision of the Supreme Court of North

Carolina in State v. Klopfer (Appendix A, infra, p.p. 12-14)

permits the delay of Klopfer’s trial to continue without

limitation. At no point in the proceedings, or record

thereof (R. 1-12), has the State of North Carolina ever

offered any reason whatsoever for the delay in trying Klop

fer’s case. At no point in the record of the proceeding (R.

1-12) or in the opinion in State v. Klopfer (Appendix A,

infra, p.p. 12-14) is there the slightest suggestion that the

defendant has in any manner waived his right to a speedy

trial. On the contrary, the record discloses clearly that

Klopfer affirmatively sought the benefit of his right to a

speedy trial in the trial court. (R. 7-10.)

The prejudice to the defendant is quite substantial. He

has been put to the burden, anxiety and expense of one

trial which ended in a hung jury, and has not been afforded

another opportunity to exonerate himself. (R. 6-10.) In

addition, Klopfer has had stripped from him the protection

which the Sixth Amendment right to speedy trial affords

against the “anxiety and concern accompanying public

9

accusation” and the “possibilities that long delay will im

pair the ability of an accused to defend himself.” United

States v. Ewell, quoted, supra.

Counsel for the petitioner has been unable to discover

any other case in the nation, State, or Federal, in which a

court takes the position, as the North Carolina Supreme

Court did in the Klopfer case, that criminal prosecution

may be instituted against an accused, and yet the accused

may be denied forever his day in court by the arbitrary ac

tion of the State and over the objection of the accused. The

decision in the Klopfer case is clearly erroneous by reason

of its blatant repudiation of the speedy trial protection

afforded to an accused by the Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments.

2. The petitioner’s case is of sufficient importance to

justify review of the judgment on its merits for the follow

ing reasons:

(a.) The indifference toward the plight of an accused

in a criminal prosecution as manifested by the Supreme

Court of North Carolina in the Klopfer decision (Ap

pendix A, infra, p.p. 12-14) is evidence of the persistent

and prejudicial indulgences in favor of the State and

at the expense of the accused which pervade the ad

ministration of criminal justice in state courts, particu

larly in the South. In the Klopfer case, the State’s prag

matic concern with the economics of a retrial for

Klopfer (Appendix A, infra, p. 14) was readily

given priority over Klopfer’s right to have the oppor

tunity of exoneration. If the proper balance between

the State and the accused in state criminal prosecutions

is to be maintained, it is imperative that arbitrary

denial of an accused’s Constitutional rights, as has oc

curred in the Klopfer case, be corrected by this Court,

(b.) The State of North Carolina by the entry of a

nolle prosequi with leave has subjected the petitioner

10

to a subtle and indirect, but nevertheless burdensome,

form of punishment for an offense as to which the State

is barred in all probability from obtaining a conviction.

(R. 7-10.) The reputation and standing of the peti

tioner, a professor of zoology at Duke University (R.

10), is being exposed without recourse on his part to

the suspicions and adverse repercussions which are

naturally attendant in any community toward anyone

charged with a criminal offense. Likewise, the pe

titioner is afforded no relief from the personal anxiety

which naturally continues in response to his being sub

ject to retrial whenever it may suit the State to resume

prosecution.

(c.) The utilization of the nolle prosequi with leave

by the State in cases such as Klopfer’s, where the ac

cused has challenged the prevailing opinion of the

community (R. 7-10), enables the State to stifle, pen

alize and discourage the exercise of the First Amend

ment rights of free speech and free assembly by using

minor criminal prosecutions to ensnare the participant

into the labyrinth of state criminal prosecution where

the participant may be harassed and intimidated into

silence or inaction. The State’s arbitrary manipulation

of criminal procedure to impair and discourage the

free exercise of First Amendment rights poses a clear

and ominous threat to the democratic process requiring

redress by this Court.

11

CONCLUSION

T o make effective the guarantee of an accused’s right

to a speedy trial under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments in a state criminal prosecution, the petition for writ

of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Wade H. Penny, Jr.

Counsel for Petitioner

Post Office Box 522

Durham, North Carolina, 27702

12

APPENDIX A

OPINION AND JU D G M EN T OF T H E

SUPREM E CO U RT OF N O R TH CAROLINA

IN T H E CASE OF ST A T E v. PET ER KLO PFER

1. Opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

in the case of ST A T E v. PET ER KLOPFER.

IN T H E SUPREM E C O U R T OF N O R TH CAROLINA

FA LL TERM , 1965

State

v. L No. 829 — FROM ORANGE

Pet er K lo p fe r j

Appeal by defendant from Johnson, J., August, 1965

Criminal Session, Orange Superior Court.

This criminal prosecution was founded upon a bill of

indictment signed by Thomas J. Cooper, Solicitor, and

submitted by him to the Grand Jury and returned a true

bill by that body at its February, 1964 Session, Orange

Superior Court. The indictment charged that on January

3, 1964, the defendant “did unlawfully, wilfully and in

tentionally enter upon the premises of Austin Watts . . .

located on Route 3, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, . . . Watts

being then and there in peaceable possession, and the said

Peter Klopfer, after being ordered to leave the said premises

willfully and unlawfully refused to do so, knowing he . . .

had no license therefor . . . etc.” .

At the March, 1964 Special Criminal Session, the de

fendant, represented by counsel of his own selection, enter

ed a plea of not guilty. The issue raised by the indictment

13

and the plea was submitted to the jury which, after de

liberation, was unable to agree as to the defendant’s guilt.

The court declared a mistrial and ordered the case set for

another hearing. T h e re a fte r , the record discloses the

following:

“ No. 3556 — State v. Peter Klopfer

“The State moves the Court that it be allowed to take

a nol pros with leave. The motion is allowed. De

fendant takes exception to the entry of the nol pros

with leave and gives notice of appeal in open court.”

T . W. Bruton, Attorney General,

Andrew A. Vanore, Jr., Staff Attorney, for the State

Wade H. Penny, Jr., for defendant appellant.

HIGGINS, J.

The appellant challenged the right of the solicitor, even

with the approval of the judge, to enter a nolle prosequi

with leave in the criminal prosecution pending against him

in the Superior Court. Stated another way, he insists his

objection takes away from the solicitor and the court the

power and authority to enter the order. The reason as

signed is that the procedure denies him his constitutional

right of a speedy trial.

When a nolle prosequi is entered there can be no trial

without a further move by the prosecution. The further

move must have the sanction of the court. When a nolle

prosequi is entered, the case may be restored to the trial

docket when ordered by the judge upon the solicitor’s ap

plication. When a nolle prosequi with leave is entered, the

consent of the court is implied in the order and the solici

tor (without further order) may have the case restored

for trial. “A nolle prosequi, in criminal proceedings, is

nothing but a declaration on the part of the solicitor that

14

he will not, at that time, prosecute the suit further. Its

effect is to put the defendant without day, that is, he is

discharged and permitted to go whithersoever he will, with

out entering into a recognizance to appear at any other

time.” Wilkinson v. Wilkinson, 159 N. C. 265, 74 S. E. 968;

State v. Thurston, 35 N. C. 256. Without question a de

fendant has the right to a speedy trial, if there is to be a

trial. However, we do not understand the defendant has

the right to compel the State to prosecute him if the State’s

prosecutor, in his discretion and with the court’s approval,

elects to take a nolle prosequi. In this case one jury seems

to have been unable to agree. The solicitor may have con

cluded that another go at it would not be worth the time

and expense of another effort.

In this case the solicitor and the court, in entering the

nolle prosequi with leave followed the customary procedure

in such cases. Their discretion is not reviewable under the

facts disclosed by this record. The order is

Affirmed.

The foregoing opinion is located in and may be cited

as: ST A T E v. KLO PFER 266 N. C. 349, 145 S. E. 2d 909

(1966).

15

2.Judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

in the case of ST A T E v. P ET ER KLOPFER.

JU D G M EN T

SUPREM E C O U R T OF N O R TH CAROLINA

STA TE FA LL TERM , 1965

vs. 1- No 829

PETER KLO PFER J ORANGE CO UNTY

This cause came on to be argued upon the transcript

of the record from the Superior Court Orange County:

Upon consideration whereof, this Court is of opinion

that there is no error in the record and proceedings of

said Superior Court.

It is therefore considered and adjudged by the Court

here that the opinion of the Court, as delivered by the

Honorable Carlisle W. Higgins, Justice, be certified to

the said S up e r i o r Court , to the intent that the

JU D G M EN T IS AFFIRM ED. And it is considered and

adjudged further, that the defendant do pay the costs of

the appeal in this Court incurred, to wit, the sum of Thirty-

three and No/100 dollars ($33.00) and execution issue

therefor. Certified to Superior Court this 24th day of

January, 1966.

SEAL

Adrian J. N ewton

Clerk of the Supreme Court

By: Kathryn W. Bartholomew,

Deputy Clerk