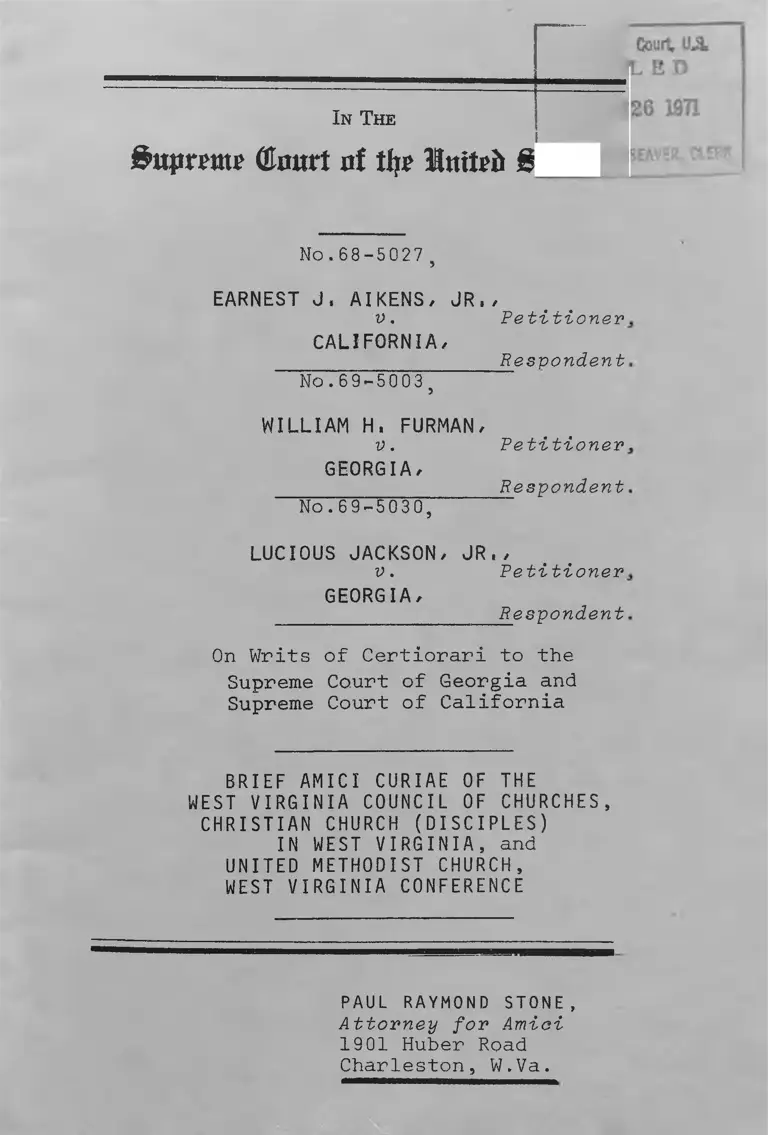

Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, and Jackson v. Georgia Brief Amici Curiae of the West Virginia Council of Churches, et. al

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, and Jackson v. Georgia Brief Amici Curiae of the West Virginia Council of Churches, et. al, 1971. f7d25914-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/66f60d06-2a9f-4837-96d1-3b6a6668afef/aikens-v-california-furman-v-georgia-and-jackson-v-georgia-brief-amici-curiae-of-the-west-virginia-council-of-churches-et-al. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In T h e

& t t p r m e (Erntrt nf tfye United U t o e a

No,68-5027 ,

EARNEST J. AIKENS, JR.,

v. Petitioner

CALIFORNIA,

Respondent

No.69-5003,

WILLIAM H. FURMAN,

v .

GEORGIA,

No.69-5030;

Petitioner

Respondent

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

v .

GEORGIA,

JR, ,

Petitioner

___ Respondent

On Writs of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Georgia and

Supreme Court of California

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE

WEST VIRGINIA COUNCIL OF CHURCHES,

CHRISTIAN CHURCH (DISCIPLES)

IN WEST VIRGINIA, and

UNITED METHODIST CHURCH,

WEST VIRGINIA CONFERENCE

PAUL RAYMOND STONE,

Attorney for Amici

1901 Huber Road

Charleston, W.Va.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of Amici Interest ......... 2

Argument

I. Capital Punishment is Cruel

and Unusual punishment in the

Sense, among other things,that

its Imposition infringes the

P r i s o n e r s 1 Religious Freedom

in a manner which constitutes

Mental Cruelty ............. ....... 3

II. Other Bases of Mental Cruelty

resulting from the Death

Penalty .....................

Conclusion .......... ...................... 19

i

TABLE OF AUTHOR STIES

Page

Cases :

Founding Church of Scientology v. U.S.,U09

F.2d llii6 (DC Cir.1969) .................... . 5

Glenn r. Wilkinson, 309 F.Supp.iill(DC Mo.l9?0).. 3

Holt v. Sarver, 309 F. Supp 362(ED Ark.1970).... 19

In re Jenison, 375 US li* (1963)................. 18

Jackson v. Bishop, kOh F.2d571 (8thCir,1968)..15,1?

Jackson v. Bishop (Dist.Ct.opin.),268 F.Supp

80U (E.D. Ark.1967)...... .................. 16

NAACP v. Button, 371 US kl$ (1963).... . k

People v. Woody, 39h P.2d 813 (196U).......... 18

Robinson v. California, 370 US 660 (1962)..... 3

Sinclair v. Henderson, No.3002f>(Nov.l7,

1970-5th cir.)..... . 1?

aiarp v. Sigler, U08 F.2d 966(8th Cir.1969)... 3

axerbert v. Varner, 37k US 398 (1963)...... k,9,18

Solesbee v. Balkom, 339 US 9 (1950)........ 15

State v. Gee Jon, 211 P.2d 676 (1923).... 17

Trap v. Dulles, 356 US 86 (1958)......... 7,8,11

U.S. v. Ballard, 322 US 78 (19UU)........ 5,6

Weems v. U.S., 217 US 3U9 (1910) ........... 8

West Virginia State Board of Education v.

Barnette, 319 US 62U (I9h3)............. li

i i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Page

Constitutions;

Constitution of the United States,

First Amendment ..................... ...... 3

Other Authorities;

Bluestone and McGahee, "Reaction to Extreme

Stress; Impending Death by Execution",

American Journal of Psychiatry, Nov. 1962.. 15

Crime in the United States (FBI-Uniform

Crime Reports),1959 through 1969 .......... 12

Harvard Law Review 83:1773 (June 1970)....... 13

Jour.Crim.Law,Cr.& Police Science 60^|^9 ^

Lamott, "Chronicles of San Quentin-Ihe

Biography of a Prison" (McKay Publirising

Company)- 1 9 6 1 ........ ................7,16,17

Marcus and Weissbrodt, "The Death Penalty

Cases", 56 Calif. Law Rev.1268 et aeq.

(Aug.-Nov.1968) ... ....... 17

New Testament (RSF), Luke 23*it3 ........... 10

Roper Opinion Poll, Feb.9, 1958 ...... U;

'Hie Death Penalty in America (Bedau, 1968) ... 13

Wisconsin Law Rev., Vol.1966,p.217 (1966) ... 18At pp.280,281

i i i

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1970

No .68-5027,

EARNEST J. AIKENS, JR.

v .

CALIFORNIA,

___________

Petitioner,

Respondent.

WILLIAM H. FURMAN,

v . Petitioner}

GEORGIA,

Respondent.

No.69-5030.

LUCIOUS JACKSON,

v .

GEORGIA,

JR. ,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Georgia and

Supreme Court of California

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE

WEST VIRGINIA COUNCIL OF CHURCHES,

CHRISTIAN CHURCH (DISCIPLES)

IN WEST VIRGINIA, and

UNITED METHODIST CHURCH,

WEST VIRGINIA CONFERENCE

2

Statement of the Interest of Amici

The West Virginia Council of Churches

is an organization whose affiliate members

represent all the major Protestant denom

inations in the St at e,participating with the

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Wheeling;

its Division of Life and Work is its arm

in the Council's concern with major moral

and social issues of our time. The West

Virginia Council of Churches is on record

with a strong stand against the imposition

of capital punishment.

The Christian Action and Community-

Service Department (of which counsel for

the amici is a member) of the Christian

Church (Disciples) in West Virginia, is

the Church's action arm in its stand on

moral issues in the secular world; the

Disciples of Christ is the first major

Protestant denomination having its origins

in the United States. The World Convention

of the Disciples of Christ has resolved

strongly against capital punishment, as

being morally defenseless.

The United Methodist Church has had a

long history of involvement in helping

solve America's problems; its Board of

Social Concerns of the West Virginia Annual

Conference represents it in the stand taken

herein--which reflects the opposition,both

state and national--of Methodists against

the death penalty.

Consent of all parties has been secured

for the submission of this amici curiae

brief (letters thereof are filed with the

Clerk of the Court).

3

ARGUMENT

i.

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IS CRUEL AND UNUSUAL

PUNISHMENT IN THE SENSE *AMONG OTHER THINGS,

THAT ITS IMPOSITION INFRINGES THE PRISONERS1

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM UNDER THE FIRST AMENDMENT

IN A MANNER WHICH CONSTITUTES MENTAL CRUELTY

The First Amendment to the United States

Const!tution, in addition to providing for

freedom of speech 5 is the source of our

precious heritage of religious freedom (in

cluding the right to be free from unnecessary

prohibitions on the exercise of our religion);

Congress shall make no law respecting

an establishment of religion, nor

prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

(emphasis supplied)

It is so wel1-settled, as not to require

citation, that the foregoing is also a re

straint on state action (as is the cruel and

unusual punishment proviso, by operation of

the Fourteenth Amendment').

It is conceded that there are limits on

the right to exercise one * s religious be-

11e f , but these limitations have heretofore

1 Robinson v. California, 370 U.S, 860 (1962)

2 Sharp v, Sigler, U08 F. 2d 966(8th C i r .1969) ;

Journal of Criminal Law, Criminologys and

Police Science 60:299 (Sept.1969). C f .Glenn

v . Wilkinson,3 09 F .S u p p .All,H17,418 (DC,Mo.

1970),but even in this case, it is noted,

4

been judicially applied--and , we submit,

should continue to be appli ed--only to

situations where the practice or the exer

cise of the claimed religious right in some

way interferes with a "compelling state

interest"^ (e .g . , the safety or welfare of

others, including considerations of prison

discipline, etc.).

We respectfully submit that there cannot

be a sufficiently-overriding state interest

in perpetuating the death penalty when due

regard is also taken of the right of a pris

oner to the free exercise of his religion

involved in his efforts--whi1e incarcerated

--to seek his own spiritual salvation(or

conversion experience), which is taught as

fundamental by all of the major Protestant

denominations, as well as in the Roman

Catholic and other faiths. The "snuffing

out" of the prisoner's life will deprive him

of all further earthly opportunity to strive

toward such salvation, even though knowledge

of its attai nment--pri or to death --may not

be the subject of absolute certainty (even

St.Paul expressed a fear of being found

"wanting", in the final analysis, based on

his own scriptural assertions).

access to Catholic clergy and rites,which

were theretofore not provided, were ordered

by the court for the prisoner(who was on

death r o w ) .

̂ Sherbert v. Verner3 374 U.S. 398,406(1963);

NAACP V. Button, 371 U.S. 415,438(1963); West

Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624,644 (1943 ) .

5

The state, in its provision for prison

chaplains and allowance of devotionals ,etc .,

has recognized some sort of obligation in re

spect to the spiritual needs of its death row

inmates by providing a limited amount of help

to a prisoner in his efforts toward an exer

cise of his religious beliefs; however, viewed

in a critical light and with discerning judg

ment, this activity on the part of the state

is quite superficial and perfunctory when com

pared with the actual spiritual needs of most

of its death row inmates. There is no substi

tute for the element of time (i.e., the right

of the prisoner to be free from the premature

ending of his life at the hands of the state,

which also ends all his temporal efforts of

continued striving toward spiritual progress

in ultimately finding God); the killing in the

execution chamber of unredeemed men represents

one of the major evils inherent in capital

punishment, and makes a mockery and travesty

of our protestations--under the aegis of our

major Fai ths--of the redemptive capacity of

man (indeed, it is utterly inconsistent with

one of our basic Christian tenets that any man

is potentially salvageable . ...with the possible

exception of those who have committed the so-

called "unpardonable sin" of blasphemy against

the Holy Ghost which is not a capital offense

under the laws of any of our states!)

It is noted that the wisdom or logic under

lying a particular religion--the free exercise

of which is sought--!' s not a proper matter for

the courts to impugn , absent any i nfri ngement

on health or safety as a result thereof4 .

4 U.S. v. Ballard, 322. U.S. 78 (1944) ; see

Founding Church of Scientology v. U . £>OJ4u9

F.2d 1146 (D.CoCir.1969).

6

A belief may be "incredible, if not prepos

terous ̂ ....in respect to a claimed religious

freedom.

It matters not whether the acquisition

of salvation, or conversion, while still on

earth and alive is sound doctrine~~theolog-

cally speaki ng--or whether the truth is that

we may all be given a "second chance" by a

beneficent God in the hereafter; it would be

considerably more spiritually palatable (and

conducive to tranquility, rather than the in

herently cruel state of mental anguish now

suffered by death row inmates) were this

beneficence to take the form of a favorable

ruling by the U . S .Supreme Court. A favorable

ruling would certainly be in consonance with

the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments (as a

result of relief of the mental and spiritual

cruelty due to the adverse psychological

pressures involved in the formidable , permanent

deprivation-through the execution of death--

of the First Amendment right to a continued

opportunity to exercise religious efforts

toward salvation). We submit that the word

"free" in the First Amendment--whi1e not

implying a right to be free from incarceration

--clearly imports a right to seek one's salva

tion free from any impending urgency and

inhibition of one's religious thought processes

as a result of the specter of the electric

chair or gas chamber. Not only is the oppres

sive (i ndeed ,pani cky) environment generated by

these implements of execution--and their

portent for ending the prisoner's life--

unconducive to the prisoner's effective effort

toward spiritual salvation, but the awesome,

5 U 0S . v .Ballard,supra, at page 87.

7

imminent act of the executioner, as well,

creates an almost insurmountable barrier to

the necessary positive state of mind (i .e . ,

thoughts of love, charity, benevolence ,and

graciousness, etc., rather than of hatred

and malice, as naturally directed against

society and particularly toward the state

and its executioner by the prisoner when 6

contemplating his imminent untimely doom).

It should be especially noted that mental

cruelty is wi thi n the ambit of the cruel and

unusual punishment concept. In Trop v . Dulles,

356 U.S. 8 6, the Uni ted States Supreme Court

held in 1 958 that psychological distress is

covered by such concept, in holding a sentence

of expatriation to be violative of such con

stitutional pri ncipie .

6 Chronicles of San Quentin--The Biography

of a Prison, Kenneth L a mo tt, 1961 (McKay

Publishing Co.), p.231, contains a description

of the effect which his impending execution

was having on a Negro man named Robert 0.

Pierce: " * * * he got a mirror fragment and

cut his throat as he kneeled to receive the^

Protestant chaplain*s last benediction

As he was dragged into the death chamber, he

said 'I’m innocent, God, you know I'm innocent.

Please,Lord, I am.' After a moment, 'All right,

God, if you want to let me go, I won't curse

y o u . ' The blood from the gash in his neck was

spreading over his white shirt as he was for

cibly strapped into the chair. As the door was

locked, the witnesses heard him scream, 'God,

you son of a bitch, don't let me go like this.

8

The cruel and unusual punishment proviso

of the Eighth Amendment is a fluid, dynamic

concept that is responsive to changing times

and conditions, and is not a static, fixed

concept that means no more than that origi

nally ascribed to it. The U.S. Supreme Court

has acknowledged this important fact on more

than one occasion; in commenting upon the

elasticity of the cruel and unusual punish

ment concept, the Court stated that it "must

draw its meaning from the evolving standards

of decency that mark the progress of a

maturi ng society."?

The Supreme Court,in Weems v. U.S,, 217

U.S. 349,378, a case involving the cruel and

unusual punishment concept, stated as far

back as the year 1910 that constitutional

protection expands "as public opinion becomes

enlightened by a humane justice." The Court

in the cases at Bar is simply being asked to

scrutinize capital punishment in all of its

aspects of cruelty--in the light of modern

knowledge and understanding concerning the

circumstances and application of the death

penalty--and, under our presently evolved

standards of decency, to vitiate this inher

ently cruel, and increasingly unusual,

punishment in favor of the at least equal1y

effecti ve deterrent, life imprisonment.

Indeed, the concepts previously discussed,

as well as those hereinafter noted (not to

foreclose others which the Court sua sponte

may realistically envisage) will more than

serve to counterbalance any claimed "compell

ing interest" on the part of the state.

7 Tvop v. Dulles, supra, at pages 100,101.

9

The "compelling interest" on the part of

the state which needs to be shown in just

ification of the deprivation of a basic

constitutional right was the subject of the

Supreme Court's decision in Sherbert v.

Verner, supra, and a long line of cases

--both before and after Sherbert--vihi ch not

only involved basic religious freedom,but

other constitutional rights,as well.

Mental cruelty having been shown to be

within the scope of the basic constitutional

right to be free from the infliction of

"cruel and unusual punishment" in the Eighth

Amendment (operative on the states through

the Fourteenth Amendment), the question is

posed: What could be more cruel than.depriv

ing prisoners--most of whom are oriented in

the prevailing tradition of spiritual salva

tion attainable only before death--of the

opportunity to realize the most important

goal of all? It matters not, from a legal

standpoint, whether such goal is attainable

in an individual case--were the prisoner to

live out the balance of his natural life,

unfettered by the hand of the executioner--

or, for that matter, whether such goal is

still attainable after death (as some believe

to be a possibility), the crucial fact is

that it constitutes mental cruelty of the

worst sort to deprive a prisoner (by the

premature ending of his life by the state)

of the tranquility inherent in the knowledge

that his available t i m e--i n which he can

continue to seek his Deity, within the frame

work of his own religious heritage--is not

going to be cut short!

10

Although the Scriptures note that "the

wages of sin is death" (meaning death of

the soul, of course, as all must die a

physical death), it is possible for some

to be expiated in the "twinkling of an

eye" (as was the thief on the Cross, St.

Dismas, who was told by Jesus, "Truly,I say

to you, today you will be with me in Para

dise"^). It is respectfully submitted that

it is not asking too much of the Court to

assume that countless death row inmates

will not be so fortunate in so short a time

(as was the case of the prisoner on the

third cross .')

It may be argued, in the case of atheis

tic or agnostic death row inmates, that

equal protection concepts would preclude

the Court's acceptance of this religious

cruelty facet of Eighth (and Fourteenth)

Amendment concepts, on the ground of

preferential treatment; however, the cruel

and unusual punishment proviso must be

weighed in terms of its actual effect on a

substantial number of death row inmates (if

found to constitute cruel and unusual punish

ment in such case, equal protection under

the Fourteenth Amendment would dictate

according irreligious condemned men the

right to life also....certai nly the latter

need the benefit of a continued right to

life as much as anyone if our own basic

religious heritage in this country--which so

strongly emphasizes sal vageabi 1 i t,y--i s to

be given any meaning at all!)

New Testament (Revised Standard Version),

Luke 23:43

n

H .

OTHER BASES OF MENTAL CRUELTY

RESULTING FROM THE DEATH PENALTY

There are many other reasons whereby,

under the circumstances obtaining in these

cases, the imposition of the death penalty

is causative of mental anguish--and ,hence,

mental cruelty. As noted hereinbefore,

mental cruelty is substantially within the

ambit of the cruel and unusual punishment

prohibition. See Trap v. Dulles3 supra, at

pages 101 , 1 0 2.

Capital punishment has a particularly

invidious nature, because it is unfair and

unjust in its imposition and application.

It generates highly aggravated feelings of

mental anguish (hence, mental cruelty) on

the part of condemned men who, for the most

part, are from 1 ess-favored ethnic and socio

economic groups in our country (the condemned

men in these cases at Bar are each Negro;

they are all poor, as witnessed by this^

Court's permission for them to proceed in

forma pauperis).

For the condemned prisoner who knows that

he is the subject of invidious discrimination

as a member of a disfavored ethnic or socio

economic group whose members (as the prisoners

herein) receive a disproportionately large

share of death sentences, compared to the

general population, capital punishment is thus

also promotive of a special kind of mental

suffering (far over and above that generated

by fear of execution alone in those decidedly

few condemned persons of relatively higher

soci al strata ) !

12

Also promotive of mental anguish is the

prisoner's realization that his death is

really useless, and accomplishes nothing,

as a deterrent to serious crime9 . A careful

survey of the FBI Uniform Crime Reports 3 for

the years 1959 through 1969 (1970 figures

were not available at the time this brief

was prepared, such figures being released

in mid-August of the year following the re

ported year) most decidedly shows that

capital punishment is no deterrent to capital

crime. These significant statistics show that

the State of Georgia (in which the prisoners

Furman and Jackson were given the death sent

ence) has had a markedly higher murder and

non-negligent homicide rate than that of an

abolition State, Wisconsin, the latter State

haying similar population (as well as popul

ation density) character!'stics--the latter

factor being the presently-recognized factor

in causality having the most important sig

nificance to the incidence of serious crime.

Perhaps of even greater significance is a

comparison of the rates of serious crime of

the two largest cities in these respective

States (Atlanta visavis Milwaukee) which are

quite revealing in showing a virtually over

whelming difference in the murder and non-

negl igent homicide rates (Atlanta ,wi th a

population similar to that of Milwaukee,

having a markedly higher rate!) The same

phenomenon is again noted when comparing

South Dakota (having capital punishment)

with its near perfect counterpart, North

Dakota (which does not have capital punish

ment)! The Court should take judicial notice

9 Crime in the United States (FBI Uniform

Crime Reports), 1959-1969

13

of all the factors relevant to capital pun

ishment, including the best available stat

istics (which show clearly that the death

penalty does not deter capital crime), as

former Justice Arthur Goldberg urged'®. The

Court, in viewing such statistics, may be

tempted to conclude that capital punishment

is an inducement to the commission of capital

crime in many instances. Actually, when one

carefully compares the best available data,

as between abolition and non-abolition states

having similar characteristics (population

density ,etc .) , one finds many more instances

of lower serious crime rates in abolition

states--in cases where there is any appreciable

di fference at all.

Former Justice Goldberg, as noted, indicated

a duty of the Court to consider all available

data in respect to the indication that capital

punishment is disproportionately and, hence, an

excessi vely severe puni shment in relation to

its ostensible social effect (i.e., its assumed

deterrence , etc .)

Bedau, in his notable work, The Death Penalty

in America (1968), which includes Professor

Thorsten Sellin's findings, as well as those of

other experts in this field, notes that capital

punishment has been so found; the basis of the

best available evidence (and we should decidedly

use what we have, even though it does not attain

the degree of precision necessary to a chemical

equation) clearly shows that capital punishment

is no deterrent to capital crime11.

^® Harvard Law Review, 83:1773 (June 1970).

In Bedau's work, page 284, Dr. Sellin states

"Anyone who carefully examines the * data is

14

The inmates of death row--at least through

the "jailhouse 1awyers"--are well aware of

the fact that capital punishment does not

deter capital crime which, It is respectfully

submitted, is more than a considerable source

of additional mental anguish for death row

i inma tes ,

It is not at all comforting, either, to

note that Roper!s opi ni on polls--i n showing a

myriad of up and down changes in public sent

iment about capital punishment-showed that

a majority of Americans was opposed to the

death penalty on February 9, 1958 . In the

latter connection, it is also noteworthy that

a large majority of this world's civilized

governments--other than Communist countries

and dictatorships-- have abolished capital

puni shment f

It is also substantially promotive of men

tal angui sh--hence , mental cruelty--for the

condemned prisoner who knows that his death

will extinguish all legal rights, including

all future rights flowing from evolved con

cepts of due process J *, when the condemned

man compares his own situation with that of

a fellow-prisoner who is under a life sent

ence for the same type of crime (the latter

person maintains a continued right to release

if facts showing innocence are uncovered, or

at least a right to a new trial in the event

of future changes in legal concepts applic

able to his case (for example. In respect to

the changing law as to invalidity of con”

bound to arrive at the conclusion that the

death penalty,as we use it,exercises no in

fluence on the extent ***of capital crimes.

Due process rights follow the prisoner12

15

victions because of changing legal concepts

as to whether a confession--strenuously

objected to at trial, but admitted anyway--

was really involuntary).

It is also a source of considerable men

tal anguish to the condemned man,in compar

ison to the situation where life imprison

ment is the sentence, because of the fact

that an inordinate amount of mental suffer

ing will visit his loved ones--family and

relati ves--wi th the resulting social stigma

(irrespective of the peer group from which

such may emanate) which ordinarily will

require more than one generation to "live

down"!

All of the foregoing are but few of the

many facets of extreme mental cruelty in

volved in the imposition and carrying out

of the death penalty.

Moreover--and of extremely important

significance--is the fact that the death

row environment is causative of severe

psychosis, and other types of mental ill

ness'? Many adverse psychotic symptoms were

noted in article based on a study in this

respect by Dr. Harvey Bluestone and Carl

L. McGahee,"Reaction to Extreme Stress:

Impending Death by Execution"3 published

in the American Journal of Psychiatry,

November ,1 962. Additionally of significance

in showing the callousness of those respon

sible for executing the death sentence--and

note the valid, common law precept that no

insane man is to be executed--is the case

through the prison walls •,Jackson v .Bishop,

i+04 F . 2d 571,576 (8th Cir.1968 ).

13 Sotesbee v.Balkom,339 U.S. 9,14 (1950),

16

of a condemned man in the California prison

at San Quentin, which is described in the

work of Lamott in his Chronicles of San

Quentin--The Biography of a Prison (David

McKay C o . ,I n c . , 1961), at page 229:

"Not long ago one condemned man

had to undergo two series of electric

shock treatments before he was judged

to be sufficiently in touch with

reality to be killed" (by lethal gas)

What of this man's mental condition prior

to this formidable electric shock treatment?

If he was in fact insane, which the above

indicates to be the case, the state has no

business of trying to "jack him up" hurried

ly so that he can immediately undergo a

horrible death by hydrogen cyanide. It

should also be especially noted that the

lower Federal court in Jackson v. Bishop3

268 F.Supp. 804 (E.D. Ark.1967) held that

the use of an electric shocking device in

prison to punish inmates is violative of

the cruel and unusual punishment provision

of the Eighth Amendment (in connection with

such prohibition, any electric shocking

device which causes convulsions and un~

consciousness--which occur during electric

shock treatment of insane persons--should

be likewise enjoined, particularly if its

end result is an immediate execution in the

gas chamber!)

dissenting opinion, Frankfurter,!.

It was reported in the press that the

last victim of California's gas chamber

had attempted suicide prior to his exec

ution; suicidal ideation,in psychiatric

parlance, is practically a determinative

indicium of severe mental illness.

17

Capital punishment also generates an over

whelming amount of mental angui sh--hence, mental

cruelty--in the prisoner's anticipation of form

idable physical pain involved (the physical pain

itself,of course, being intrinsically cruel).Two

authors of the leading law review article "The

Death Penalty Cases" in 56 Calif. Law Rev.1268

(1968) noted what appears to be an inordinate

amount of prolonged consciousness (hence,pain)

in the executions of two of America's most fa

mous felons (at pages 1339 and 1341 thereof).

It is also noteworthy that these authors imply

strong agreement with one of your a m i c i ’s basic

underlying premises in the first part of this

brief that capital punishment infringes reli

gious freedom rights of a prisoner who i_s_ or

who might become religious (page 1363).

In the case of Jackson v . Bisho-p,it is also

extremely significant that the court,speaking

through then-Circuit Judge Blackmun, found cor

poral punishment to violate constitutional

proscriptions against cruel and unusual punish

ment. A fortiorari the considerably more harsh,

tremendously more painful, execution of death

should be abolished, using similar considerations

It is noted that corporal punishment was not

held to be violative of the cruel punishment

concept several generations ago when such proviso

was formulated (a judicial abrogation of capital

punishment now accordingly appears more than ad

equately warranted!)

Capital punishment, by electrocution or by

gas ‘ 7 is fraught with the possibility of further

cruelty by unbridled administrative prerogative

in its application. Although electrocution often

results in a cruel burning (literally) of the

prisoner, lethal gas may also constitute a hor

rible method of prolonged suffering/5The death

row environment is also being scrutinized by the

5th Circuit {Sinclair v. Henderson, Nov 17,1970; No .30025)

P. 2d 676 ( 1 923 )

Chronicles of San Quentin,supra,page 228.

18

This Court has heretofore acknowledged

an obligation to thoroughly consider and

evaluate--free from the judicial strictures

of yesteryear--al1 the relevant factors and

circumstances (including many of those not

theretofore thought to be judicially cogni

zable) in a determination of whether or not

a "compelling state interest" exists for a

particular puni shment. The Uni ted States

Supreme Court in In re Jenison,375 U.S. 14

(1 963) --a case i nvolvi ng a woman's

refusal to perform service on a jury (due

to the proscription in the Sermon on the

Mount, "Judge not, that you be not judged")

-- remanded the matter to the state court

for further consideration in the light of

Sherbert v. Verner, supra.

The California appel1 ate court has also

acknowledged that a "compel 1i ng state int-

eresf'must be shown before a particular

puni shment can be held consti tutional b .

The opinions articulated by another

commentator,that there must be a compel 1i ng

state i nterest shown when the validi ty of

a 1 aw or regulation is in question, are

also worthy of note .

Capital puni shment is utterly devoid of

any rehabilitative value. Its carrying out

--within the prison setting--also stif1es

efforts of the authorities to rehabi1i tate

prisoners incarcerated for other than capital

offenses, because of i ts implied admission

of failure to rehabilitate and its manifest

di sregard for the sanctity of human life.

^ People v. Woody3394 P.2d 813 (1964)

17 wigoon&in Law Review Vol. 1966 3 p.280

et seq.

19

Dr,Sheldon Glueck, the noted Harvard

penologist, condemns capital punishment

for its adverse consequences on otherwise

valid rehabilitative efforts as to those

prisoners not under a death sentence, by

stating that the death penalty "bedevils

the administration of criminal justice and

is the stumbling block in the path of

general reform in the treatment of crime

and criminals". In Bolt v. Sarver} 309

F.Supp.362 (E , D. Ark.1 970), a Federal court

held that the entire penitentiary system of

Arkansas was violative of cruel and unusual

punishment concepts, noting that an effect

ive plan of rehabiTitation--which was

1acki ng--i s necessary to constitutional

validity.

CONCLUSION

The Court is respectfully requested to

use its inherent power of judicial notice,

in gathering to itself al1 of the relevant

facts which bear on the physical and mental

cruelty of the death penalty. It is submit

ted that the nature of capital punishment, ■

and the formidable circumstances and burdens

attendant thereupon, render it unconsti

tutional in violation of the proscription

against cruelty (including mental cruelty

resulting from the imminent deprivation of

religious freedoms). For the foregoing

reasons, the amici urge that the judgments

below be reversed, thus letting God work

his natural, benevolent purposes in this

world f

Respectfu11y submitted,

Paul Raymond Stone,

Attorney for Amici

D a te d:A u g .25,1971 1901 Huber Road

Charleston, W.Va.