Brown v. General Services Administration Annotated Brief for Petitioner

Working File

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. General Services Administration Annotated Brief for Petitioner, 1975. 455b80a5-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/670a8ccc-feda-4ceb-b313-0d2555792cd8/brown-v-general-services-administration-annotated-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

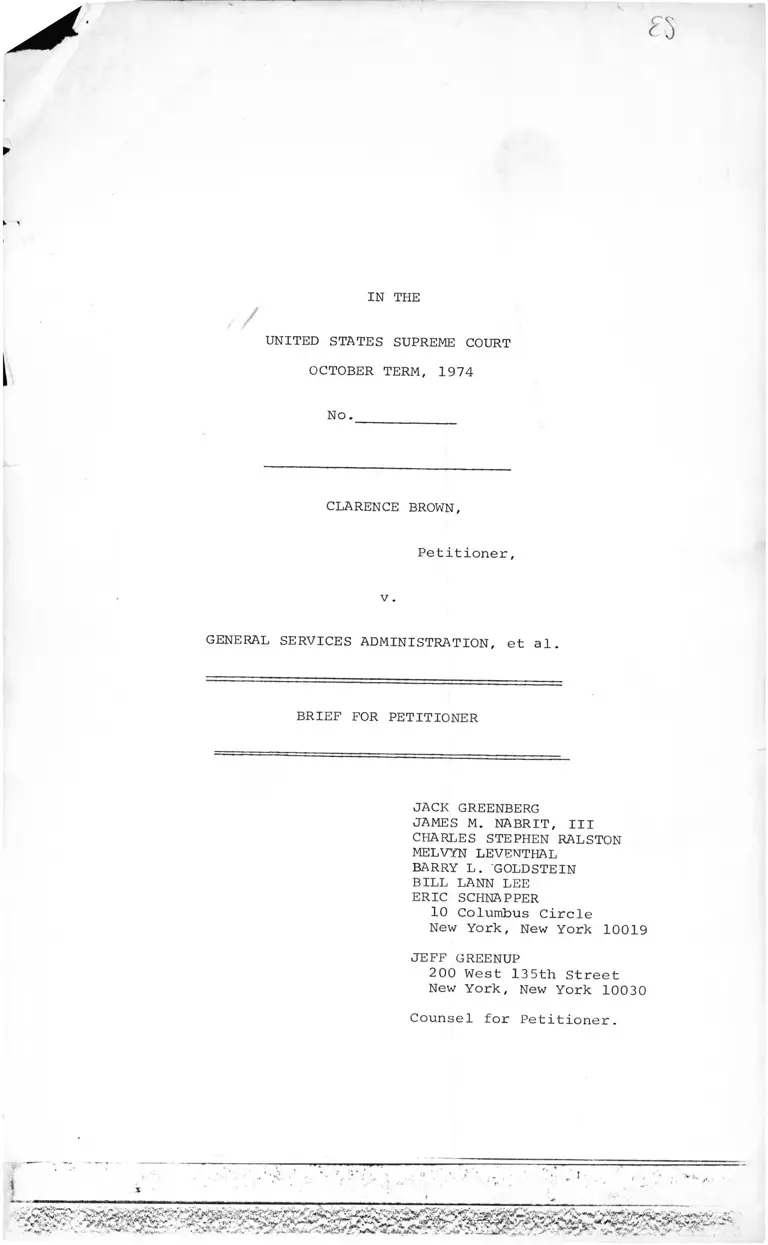

IN THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No.

CLARENCE BROWN,

Petitioner,

v.

GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION, et al.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON MELVYN LEVENTHAL

BARRY L. 'GOLDSTEIN BILL LANN LEE

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JEFF GREENUP

200 West 135th Street

New York, New York 10030

Counsel for Petitioner.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions Below

Jurisdiction

Questions Presented

Statutory Provisions Involved

X

/ f

Statement of the Case

/Vv\ /W\ I ̂ ^ 1 v

ARGUMENT

I .

II.

■'ll

vV̂,a

Jurisdiction Over This Action Is

Conferred By Statutes Adopted Prior

To Section 717 of Title VII Of The

19S4 Civil Rights Act ............. .

A. 1. The 1866 Civil Rights ..... .

2 . The Mandamus Act .......... .

3 . The Tucker Act ............ .

4. The Administrative Procedure

Act ......................

5. 28 U.S.C. § 1331 .......... .

B. Application Of Section 717 To

Discrimiriatipur'Occurring Before

March 24,^97.2 ................ .

C. Section 717 Did Not Repeal Pre-

Existing Remedies For Discrimi

nation in Federal Employment ....

This Action Should Not Be Dismissed

For Failure To Exhaust Administra

tive Remedies ..................... .

A. Exhaustion of Administrative

Remedies Is Not a Prerequisite

To An Action Under The 1866

Civil Rights Act, etc.........

B. Even If Exhaustion Is Generally

Required In Such Actions, It

Should Not Be Required In This

Case .........................

CONCLUSION

r

IN THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

No. ____

CLARENCE BROWN

Petitioner,

v .

GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION, et al.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, which is not yet

( \c (M.lir- W Kreported, is set out in the Appenqix hereto at pp. 2a-18a.

The opinion of the District Court, which is not reported, is

. * 1 Pfc' n nset out in the Appendix hereto at.p.la.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

Questions Presented

1. Did section 717 of-Title VII of the 1964 Civil

Richts Act repeal, pro tanto, the 1866 Civil Rights Act, the

Tucker Act, the Maridamus Act, and the Administrative Procedure

T 1 'W'O f) c ' h sinAct? '~~y\ ! ̂ y Qs? ( i ~~J I '7 (

U

{ />y 7

2. Are the^exhaustion requirements for a civil action

to remedy employment discrimination, maintained under the 1866

\ yT

Civil Rights Act, the Tucker Act, the Mandamus Act, and the\ /

Administrative Procedure Act, different and more stringent

than those establiished b;

h T x

i S a w 7 h U o

jr A r I -7r ] ‘

by Congress for an action under section 717?

Jsd 4 1

1/ h

Statutory Provisions Involved

Section 717(a) of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16(a), provides:

All personnel actions affecting employees or applicants for employment (except with regard to

aliens employed outside the limits of the United

States) in military departments as defined in

section 102 of title 5, United States Code, in

executive agencies (other than the General Account

ing Office) as defined in section 105 of title 5,

United States Code (including employees and applicants for employment who are paid from nonappropriated funds)

in the United States Postal Service and the Postal

Rate Commission, in those units of the Government of

the District of Columbia having positions in the com

petitive service, and in those units of the legisla

tive and judicial branches of the Federal Government

having positions in the competitive service, and in

the Library of Congress shall be made free from any

discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex

or national origin.

Section 717(c) of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C, §2000e-16 (c) , provides:

- 2 -

Within thirty days of receipt of notice of

final action taken by a department, agency, or unit referred to in subsection 717(a), or by the

Civil Service Commission upon an appeal from a

decision or order of such department, agency, or

unit on a complaint of discrimination based on

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin,

brought pursuant to subsection (a) of this section,

Executive Order 11478 or any succeeding Executive

orders, or after one hundred and eighty days from

the filing of the initial charge with the depart

ment, agency, or unit or with the Civil Service

Commission on appeal from a decision or order of

such department, agency, or unit until such time

as final action may be taken by a department,

agency, or unit, an employee or applicant for employment, if aggrieved by the final disposition

of his complaint, or by the failure to take final

action on his complaint,may file a civil action

as provided in section 706, in which civil action

the head of the department, agency, or unit, as

appropriate, shall be the defendant.

Section 1981, 42 U.S.C., provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same right in every

State and Territory to make and enforce contracts,

to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full

and equal benefit of all laws proceedings for the

security of persons and property as is enjoyed by

white citizens and shall be subject to like punish

ment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions

of every kind, and to no other.

Section 1361, 28 U.S.C., provides:

The district courts shall have original juris

diction of any action in the nature of mandamus to

compel an officer or employee of the United States

of any agency thereof to perform a duty owed to the

plaintiff.

Section 1346, 28 U.S.C. provides in pertinent part:

(a) The district courts shall have original juris

diction, concurrent with the Court of Claims, of:

x x

Any other civil action or claim against

the United States, not exceeding $10,000

in amount, founded upon the Constitution

- 3 -

(2)

or any Act of Congress, or any regulation

of an executive department, or upon any

express or implied contract with the United

States, or for liquidated or unliquidated

damages in cases not sounding in tort.

Statement—of-^the—Case----

Petitioner is a black employee of the General Services

Administration. Petitioner, who is presently a GS-7, has not

been promoted for 8 years.

On July 15, 1971, petitioner filed with the General

Services Administration Equal Employment Office an administra

tive complaint alleging that he had been denied a promotion on

the basis of race. The agency investigation revealed that

petitioner had been repeatedly passed over for promotions in

favor of white employees. The uncontested statistics revealed

that a disproportionately low number of black employees were

promoted above the GS-7 level within the General Services Adminis

tration. On March 23, 1973, twenty months after petitioner

filed his administrative complaint, the General Services Adminis

tration issued its final agency decision concluding that it had

not discriminated on the basis of race.

Petitioner was notified of the agency decision on March

26, 1973. The letter of notification advised petitioner that

he could commence a civil action in the United States District

Court, or file an appeal to the Board of Appeals and Review of

the Civil Service Commission. The letter also indicated that

any action under section 717 of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42

U.S.C. §2000e-16, must be commenced within 30 days of receipt

- 4 -

J

of the letter. At that time, and until May of 1974, it was the

uniform position of the Department of Justice that section 717

did not apply to claims such as those of petitioner, which arose

prior to the effective date of the statute, and that there were

Vaccordxngly no rights to be lost by failing to sue within 30 days.

On the basis of this letter petitioner decided to file suit.

Because petitioner had great difficulty locating an attorney

who would represent him, he did not succeed in filing his com

plaint until May 7, 1973, 12 days after the deadline for filing

Van action under section 717. Since the deadline for filing an

action under section 717 had by then passed, petitioner asserted

federal jurisdiction under several other statutes, including

the Mandamus Act, 28 U.S.C. §1361, the Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C.

§1346, the 1866 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1981, and the

Administrative Procedure Act.

On September 27, 1973, the District Court for the Southern

District of New York dismissed the action for lack of jurisdic

tion. On November 21, 1974, the Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit affirmed that dismissal. The Second Circuit

concluded (1) that section 717 had, by implication, repealed

pro tanto the Tucker Act, the Mandamus Act, the 1866 Civil Rights

Act, the Administrative Procedure Act, and the other statutes

which petitioner asserted created federal jurisdiction (2) that

section 717 applied to discrimination occurring prior to its

effective date, March 24, 1972, and that the implied repeal was

__/ On August 10, 1973, the government moved to dismiss this

action in the District Court on the ground, inter alia, that

petitioner had not commenced his action within the 30 days

required under Section 717. On July 27 and September 24, 1973

the same United States Attorney filed memoranda in the same

District Court, in Henderson v. Defense Contract Administration

Services, 370 F.Supp.180 (S.D.N.Y.1973), arguing that section

717 did not apply to employees such as petitioner who were the

victims of discrimination prior to March 24, 1972.

_/ jĵ lthin a week of receiving the letter of March 23, petitioner

presented himself and the letter to the clerk of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New York,

where the pro se clerk advised him to retain a private attorney.

Compare, Huston v. General Motors Corp., 477 F.2d 1003 (8th

5

accordingly retrospective and (3)/^couTd not sue because he had

not completely exhausted the available administrative remedies.

__/ (contd.)

Cir. 1973). Prior to obtaining the services of counsel,

petitioner unsuccessfully sought assistance from three

other attorneys, the New Jersey Civil Liberties Union,

and the national office and a civil rights organization.

6

1

ARGUMENT

X '

I. Jurisdiction Over This Action Is Conferred

By Statutes Adopted Prior To Section 717 of

Title VII of The 1964 Civil Rights Act

In 1971-72, when Congress was considering adopting section

717 or other legislation to assure federal employees a right to

judicial determination of their claims of discrimination, both

the Civil Service Commission and /l5he Department of Justice advised

Congress that federal employees already had that righfe^Irving

Kator, the Executive Director of the Commission, testified:

"There is also little question in our mind

that a Federal employee who believe he has

been discriminated against may take his

case to the Federal courts . . . . " _ /

The Commission submitted a written statement insisting:

"We believe Federal Employees now have the

opportunity for court review of allegations

of discrimination, and believe they should

have such a right."_/

The Commission insisted that the then leading cases denying

/Federal employees such a right to sue, Gnotta v. United States ,

415 F.2d 1271 (8th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397 U.S. 934(1970),

and Congress of Racial Equality v. Commissioner, 270 F.Supp.

537 (D.Md. 1967^were incorrectly decided. T

_/ Hearings Before Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on

Labor & Public Welfare, 92 Cong., 1st Sess. 301 (1971) p.296.

_/ Id. p. 310

_/ In the CORE case, suit was brought to redress alleged

discriminatory denials of promotions. The case was dismissed

on several groundq^among which was that Executive Order No.11246

(the predecessor of the present Executive Order relating to

discrimination) gave no actionable right in a district court.

As it appears that the attention of the court in thei&ORE case

was not directed to the statute (5 U.S.C. § 7151 (Supp. v. 1965-

1969) and that case involved no constitutional issue, we do not

regard it as dispositive of the matter under consideration. To

the same effect see Gnotta v. United States,415 F 2d 1271 (8th Cir.

1969), in which one court found no jurisdiction to review an alleged

failure of promotion due to discrimination but did not discuss the

statutory or constitutional issues that might be involved in such

an action. We are of the opinion that an individual who has exhausted the discrimination complaint procedure provided in Part

713 of the Civil Service regulations (5 CFR part 713) may obtain

judicial review of the alleged discriminatory action . . . "

Hearings Before the Sub-committee on Labor of the House Committee

on Education and Labor, 92 Cong., 1st Sess. 386 (1971).

7

~2

Assistant Attorney General Ruckelshaus assured the Senate

that the courts could remedy any unconstitutional or unlawful

federal action.

"[T]o come extent injunctive remedies are already

available. The constitutionality of any program

can be challenged. The authority within the program

of an official to act can be challenged."

"[T]here is no doubt that a court today may look

into unauthorized or unconstitutional agency action

. . . " /

Although the Civil Service Commission insisted that section 717

_ /"would add nothing" to the rights federal employees already

enjoyed under earlier statutes. Congress adopted section 717

in view of its concern that the courts might not construe the

existing statutes to provide such a remedy.

Petitioner in the instant case asserts that jurisdiction

over his claims of federal employment jurisdiction is confined

by statutes adopted prior to section 717: the 1866 Civil Rights

/ /Act , the Mandamus Act, the Tucker Ac^

_ /Procedure Act and 28 U.S.C. §1331.

the defendants' allege.! refusal to prom'

Administrative

ner maintains that

im on account of race

violates the Fifth Amendment, the 1866 Civil Rights Act, 5 U.S.C.

_/ _/ ____/§ 7151, Executive Order 11482 and 5 C.F.R. §713

/

_/

_/

_/

_/

_/

_/

/

V _ y t ^

42 U.S.C. §1981.

28 U.S.C. §1361

28 U.S.C. §1346

5 U.S.C. §702-06.

[5 lines] h

[10 lines] -jyyv^r-rjW-

~{1 Tines] X ̂ S ££ <■*

i -'-n o\

,,

o CL<b

/

0

U 2 c3

8

A . 1. The 1866 Civil Rights Act

Section 1981, 42 U.S.C., which derives from Section 1

of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the same

right in every state and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full

and equal benefit of all laws and pro

ceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind,

and to no other. (Emphasis added)

The right to make and enforce contracts clearly includes employ

ment contracts, and entails a ban on racial discrimination in

hiring and promotion. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 43 U.S.

L.W. 4623, 4625 (1975). Section 1981 has been uniformly held

_/ _/to bar discrimination in employment by state and local governments

_/ _/by private employers, and by labor unions. Petitioner maintains

that section 1981 bars discrimination in employment by the federal

government as well.

The broad language of Section 1981 manifestly includes

within its scope all discrimination in employment by any employer.

.c \ )

_/ See e.g. Johnson v. Cain, 5 EPD 1(8509 (D. Del. 1973); Suel v.

Addington, 5 EPD 1(8042 (D. Alaska 1972); Strain v. Philpott, 4 EPD

KK7885, 7562, 7521 (M.D. Ala. 1971); Morrow v. Crisler, 3 EPBh8119

(S.D. Miss. 1971); London v. Florida Department of Health, 3 EPD

1[8018 (N.D. Fla. 1970) .

_/ Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971); Arrington

v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 306 F.Supp. 1355

(D. Mass. 1969); Glover v. Daniel. 434 F.2d 617 (5th Cir., 1970);

Smiley v. City of 'Montgomery^ 350F.Supp. 451 (M.D. Ala. 1972);

West v. Board of Education of Prince George's County, 165 F.Supp.

382 (D. Md. 1958); Mills v. Board of Education of Ann Arundel, 30

F.Supp. (D. Md. 1938).

_/ Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970),cert, denied 401 U.S. 948 (1971); Rice v. Chrysler Corp. 327 F.Supp.

80 (E.D. Mich. 1971); Hackett v. McGuire Brothers Inc., 445 F.2d

442 (3d Cir. 1971); Young v. International Tel. & Tel. Co., 438

F.2d 737 (3d Cir. 1971); Brown v, Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

\ \ q) 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cerfyr- denied, 93 S. Ct. 319 (1972);Boudreau v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting, 437 F.2d 1011 (5th Cir.

1971);Caldwell v^ National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044 (5th Cir.1971),

cert, denied 404 U.S. 998 (1970); Brqdy v, Bristol Myers, 452 F.2d

621 (8th Cir. 1972);Bennette v. Gravel^e, 323 F.Supp. 203 (D. Md.1971

Copeland v. Mead Corp. , 51 F/iR. D. 2 66 ITn .D. Ga. 1970); Lazard v.

^ Boeing Co., 322 F.Supp.343 ( ~ D. La.1971); Long v. Ford Motor Co.,352 F.Supp. 135 (E.D. Mich. J_972); Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp

350 F.Supp. 529 (S.D. Tex. 1 72); Jenkins v~. General Motors Corp. ,475 F.2d 764 (5th Cir. 1973).

/ Waters v. Wisconsin SI eel Works, 427 F.'M 476 (7th Cir.1970)

public or private. The class of persons protected is described

in the all encompassing language to be "[a]11 persons within the

jurisdiction of the United States." Any attempt to restrict the

literal scope of section 1981 would fly in the face of this express

language. Had Congress wished to limit the statute so as to

preclude federal discrimination, it knew how to do so. Section

1983, 42 U.S.C., expressly limits its coverage to persons acting

under color of state law, as did a number of other post Civil War

- _ /civil rights provisions. See e.g. 16 Stat. 140, §§ 1^2^ 3. No

such limitation was placed in section 1981, and no such limitation

should be added to it by the courts.

The conclusion that section 1981 prohibits federal

discrimination is dictated by this Court's decisions in Hurd v.

Hodge, 334 U.S. 74 (1948) and District of Columbia v. Carter,

409 U.S. 418 (1973). Section 1981 was originally enacted as part

of Section 1 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, 14 Stat. 27, which pro

vided :

[A]11 persons born in the United States

and not subject to any foreign power, excluding

Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be

citizens of the United States; and such citizens,

of every race and color, without regard to any

previous condition of slavery or involuntary

servitude, except as a punishment for crime

whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,

shall have the same right in every State and

Territory in the United States to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence,

to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full

and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings

~7 (contd)

cert, denied 400 U.S 911 (1970); James v. Ogilvie, 310 F.Supp.661(N.D. 111. 1970); Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 350 F.Supp.

529 (S.D. Tex. 1972); Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 349

F.Supp. 3 (S.D. Tex. 1972) Jenkins v. General Motors Corp., 475 F.2d

764 (5th Cir. 1973)

_/ The criminal provi

Act, 16 Stat. 140, apply _____

the criminal provisions of the 1866 Act apply to conduct under color of any law. 14 Stat. 27

ion 2 of the 1870 Civil Rights

conduct under color of state law;

l0

). I

for the security of person and property,

as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, and

penalties, and to none other, any law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the

contrary notwithstanding.

Section 1 protected, not only the rights now covered in §1981,

including the right to contract, but also the right to buy and

own real property. Manifestly if any one of the rights covered

by Section 1 was protected against federal discrimination, all of

them must have been, for the enumeration of rights encompassed

draws no distinction among them. Since 1866, section 1 of the

Civil Rights Act w^aivided into two sections; the provisions

_ /

regarding real property were placed in 42 U.S.C. §1982, and the

other provisions in §1981. This restructuring, however, involved

no change in the substance of the rights first established in 1866.

This Court has correctly noted that the scope of §1981

and §1982 is necessarily the same. In Tillman v. Wheaton Haven

Recreation Asso., 35 L.Ed. 2d 403 (1973), the Court held,.

The operative language of both § 1981 and §1982

is traceable to the Act of April 9,1866, c.31,

1, 14 Stat. 27. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24,30-31

(1948). In light of the historical interrelation

ship between §1981 and §1982, we see no reason

to construe these sections differently . . .

35 L.Ed. 2d at 410-411. Since the Court had concluded that §1982

covered discrimination by private clubs, it held that §1981 did S &

as well.

s In Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24(1948), the Court held that

Xection 1982 precluded the federal courts in the District of

Columbia from assisting housing discrimination by enforcing re-

structive covenants. See 334 U.S. at 30-34. Manifestly if

section 1982 barred federal discrimination, then, as in Tillman,

section 1981 covers federal discrimination as well. The holding

_/ "All citizens of the United States'shall have the same right,

in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens thereof

to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property."

11

in Sped was reaffirmed last year in District of Columbia v. Carter,

409 U.S. 418 (1973).

Section 1982, which first entered

our jurisprudence as §1 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866 . . . was enacted as a means to

enforce the Thirteenth Amendment's proclamation that " [n]either slavery nor involuntarily

servitude . . . shall exist within the United

States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

See Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409,

437-438 (1968). "As its text reveals, the

Thirteenth Amendment is not a mere prohibition of State laws established or upholding slavery, but

an absolute declaration that slavery or involuntarily

servitude shall not exist in any part of the United

States." Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3,20 (1883) . . .

Moreover, like tha Amendment upon which it is

based, §1982 is not a "mere prohibition of State laws

establishing or upholding" racial discrimination in

the sale or rental of property but, rather, an "absolute"

bar to all such discrimination, private as well as

public, federal as well as state. C.F. Jones v. Alfred H . Mayer & Co., supra, at 413. With this in mind,

it would be anomalous indeed if Congress chose to

carve out the District of Columbia as the sole

expection to an act of otherwise universal application.

And this is all the more true where, as here, the

legislative purposes underlying §1982 support its

applicability in the District. The dangers of

private discrimination, for example, that provided

a focal point of Congress' concern in enacting the

legislation, were and are, as present in the District

of Columbia as in the States, and the same considerations

that led Congress to extend the prohibitions of §1982

to the Federal Government apply with equal force to

the District, which is a mree instrumentality of

that Government. [Emphasis added)

_/409 U.S. at 422. The reasoning of Carter is fully applicable

to §1981. Section 1981, like section 1982, is an absolute bar

to all discrimination ■not' limited to state action. Section 1981,

like section 1982, was originally based on the broad prohibition

It-. /of the Thirteenth Amendment, not the narrower, commands of the

Fourteenth Amendment which deal with'the States. And, like

section 1982, employment discrimination in violation of section

1981 was

hands of

of state

and is as present in the District of Columbia and at the

federal officials as it is in the ̂ S^ates and at the hands

officials.

_/ in Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 97, n.2 (1945)

the 'court held that §2 of the 1866 Act, rendering criminal certain

discrimination against lany inhabitant of any State, Territory or District," applies to Federal officials.

The legislative background of the 1866 Civil Rights

gives no reason to believe that Congress would have intended

to deny to newly freed slaves protection from discrimination

by federal officials. The abolitionists in control of

Congress in 1866 had for a generation been anxious to abolish

slavery and all its trappings in the District of Columbia.

/See ten Brook, Equctl Under Law,pp. 41-57 (1951). it is

unlikely that Congress, having forbidden slavery throughout

the nation, intended by Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act

to abolish the "badges of slavery" only in the states and

to leave them intact in the nation's capitol. See Jones v.

Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 439 (1968). Congress

also had ample reason for concern that the Federal officials

of the Freedmen's Bureau, established in 1865, were seriously

_/mistreating and exploiting the newly black former slaves.

The memory of the mistreatment of blacks by federal officials

under the Fugitive Slave Act was still fresh in the minds

_/of abolitionists in 1866. Freedmen1s Bureau agents were

reported to be more sympathetic to the desires of white Southern

-j rl. (Seplanters than the needs of Freedmen. (See e.g. K. Stamp,

The Era of Reconstruction 133-34 (1965) .J By April of 1866

Congress was aware of President Johnson's opposition to its

reconstruction program, and believed that he was actively

_/ Henry B. Stanton, in an address to the Massachusetts legis

lative urging abolition in the District of Columbia, had argued

"Having robbed the slave of himself, and thus made him a thing.

Congress is consistent in denying to him all the protections of

the law as a man. His labor is coerced from him by laws of Congress: No bargain is made, no wage is given . . . There is

not the shadow of legal protection for the family state among

the slaves of the District . . . No slave can be a party before a

judicial tribunal, . . . in any species of action against any person, no matter how atrocious may have been the injury received.

He is not known to the law as a person: much less, a person with

civil rights . . . Congress should immediately restore to every

slave, the ownership of his own body, mind and soul, transfer

them from things without rights, to men with rights . . . the

slave himself should be legally protected in life and limb, in his

earnings, his family and social relations, and his conscience." ten Broek, Equal Under Law, p.46 (1951).

f^955?'BentleY' History of the Feedmen's Bureau,77, 84,125-132

See

ooth

J.

21

Equal Under Law,

508 (1858) 57-65(1951); Ableman

- 13

undermining enforcement of new legislation and dismissing

. - Vfederal officers who supported Congress’ policies. See M. King,

Lyman Trumbull 293-95 (1965).' That concern about the conduct

of federal officials is manifest in other provisions of the 1866

Civil Rights Act, which compels federal marshalls , on pain of

_/criminal punishment, to enforce the Act, expressly requires that

the district attorneys and other officials be paid for enforcing

_/the Act at the usual rates, and authorized the circuit courts,

rather the President, to appoint commissioners with the power to

arrest and imprison persons violating the Act.

Any possibility that Congress intended to exempt federal

officials from coverage by the 1866 Civil Rights Act is negated

by the express language of the Act extending its coverage to the

territories. Territorial governments, like that of the District

of Columbia, are but instrumentalities of the federal government,

and in the territories it is the United States itself which is the

sovereign. See District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418,422

(1973); United States v. City of Kodiak, 132 F.Supp. 574, 579

(D. Ct. Alaska, 1955). Many officials in the territories, including

judges and marshalls, were appointed directly by Washington, and all

/ .

territorial officers were technically federal officials.

In the mid-nineteenth century, when the role of the federal govern

ment was far more limited than it is today, federal employees were

under normal circumstances concentrated in the District of Columbia

and the territories, and it was in general only there that

employees were likely to be in a position to deny blacks the right

_/ 14 Stat. 28 §5.

_/ 14 Stat. 29, §7

_/ See E. Pomeroy, The Territories and the United States (1947);

M. Ferrand, Legislation of Congress for the Government of the

Organized Territories of the United States (1896).

14

/

V

to make contracts, to enjoy equally the benefit from the

protection of the law and legal proceedings, or to be subject to

only the same pains and punishments as whites. The status and

treatment of Blacks in the territories had long concerned the

abolitions in the 1066 -r- Congress; that issue had been a

major factor leading to the Civil War.\L Dred Scott v. Sanford,

19 How. ( U.S.) 399 (185- ) . The inclusion under the 1866 I Xi

of persons in the territories represented a deliberate decision

by Congress to protect freedmen in a region where the only

officials who could interfere with their rights were federal

remedy /

officials, and thus to ban federal discrimination.

The 1866 Civil Rightsl, in addition to forbidding employ-

r d jment discrimination m section,, expressly provided a judicial

r 7

That khe district courts of the United

State's, within their respective dis

tricts, shall have . . . cognizance

. . . concurrently within the circuit

courts of the United States, of all

cases, civil and criminal, affecting

persons who are denied . . . any of

the rights secured to them by the

first section of this act . . .

14 Stat. 27. This provision is now incorporated in 28 U.S.C.

§1343, which provides in part,

The district courts shall have original

jurisdiction of any civil action

authorized by law to be commenced by

any person:

* * *

(4) To recover damages or to secure equitable

or other relief under any Act of Congress

providing for the protection of civil rights,

including the right to vote.

The literal language of Section 3 and 28 U.S.C. §1343(4)

clearly encompasses jurisdiction to afford relief againstjviolationsfJvAo. \J K711s\ r \ \J Ck \ cv.

of §1981, fey federal officials.

_/ If Congress had wanted to limit jurisdiction to discrimination

involving state action, it knew how to do so. Sections 2 and 3 of

the 1870 Civil Rights Act and Section 1 of the 1871 Civil Rights

Act expressly restrict their coverage to action taken under color

of ̂ rfate law, as d'oes 28 U S.C. §1343 (3). No such limitation is

to be found in the 1866 Act or ..flection 1343 (4), and itsaosence must be taken as abCongressional intent to do just what those provisions said — confer jurisdiction over all violation of §1981,

regardless of whether the violation may be by state officials, federa

It is particularly unlikely that the Congress which enacted

the 1866 Civil Rights Act could have intended that, to the extent

that federal officials violated its provisions, aggrieved citizens

would have no legal remedy. The abolitionists who finally won

control of the Congress and many states in the 1860's a^dl$70's

had long maintained that the rights described in Reconstruction Amend

ments, and legislation were not new, but already existed by virtue

_/of the privileges and immunities clause and the Bill of Rights.

The purpose of such Amendments and legislation was, above all, to

make those rights enforceable. The 1866 Civil Rights Act, enacted

before the Fourteenth Amendment, was entitled "An Act to protect

all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and

Furnish the Means of their Vindication." 14 Stat. 27 (Emphasis

added) Congressman Wilson, speaking in favor of the 1866 Civil

Rights Bill, explained:

Mr. Speaker, I think I may safely affirm

that this bill, so far as it declares the

equality of all citizens in the enjoyment

of Civil rights and immunities, merely

affirms existing law. We are following the

Constitution. We are reducing to statute

form the spirit of the Constitution. We

are establishing no new right, declaring no

new principle. It is not the object of this

bill to establish new rights, but to protect and enforce those which already belong to

every citizen. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong. 1st

Sess. 1117.

To hold the 1866 Civil Rights Act unenforceable against the federal

government would be to frustrate the manifest intent of Congress.

And, since federal discrimination was already forbidden by the

Fifth Amendment, to render the Act unenforceable against federal

defendants would be to render the Act, in this regard, nugatory.

_/ See generally ten Brock, Equal Under Law (1951); Graham,

"The Early Anti-Slavery Backgrounds of the Fourteenth Amendment,

1950 Wis. L. Rev. 479; Graham, "The Conspiracy Theory1 of the

Fourteenth Amendment," 47 Ufele L.J. 371 (1938).

- 16

The fact that section 1981 creates an enforceable remedy

against federal officials and thus entails in certain instances

v b tiff' it j •: i i n Cj pa waiver of sovereign immunity.. The Congress which enacted section

1981 had no fondness for sovereign immunity, and cannot have

contemplated that any ex-slaves aggrieved by .Federal misconduct would

have to seek a remedy through a private bill. This court had already

made clear that it will not "as a self constituted guardian of the

Treasury import immunity back into a statute designed to limit it.

Indian Trading v. United States, 350 U.S. 61, 69 (1955), or

"whittle down . . . by refinements" e*? statute affecting sovereign

immunity. United States v. Yellow Cab Co.» 340 U.S. 543, 550 (1950)

/ No sovereign immunity would be involved in an action for

injunctive relief or to enforce the regulation requiring back pay.

See p. , infra. Section 1981, ir^onjunction with §1343 (4).

covers ordinary damages and any other appropriate relief.

/ That Congress* only three years earlier, led by many of

the prominent abolitionists, jH^had enacted the first compre

hensive waiver of federal immunity in an attempt to end the

long standing practice of seeking redress from Congress through

private bills. President Lincoln, in his first State of the

Union message, had urged such abolition:

Sc

th

It is important that some more convenient means

should be provided, if possible, for the adjust

ment of claims against the Government especially

in view of their increased number by reason of the

war. It is as_jjui-eh''1fHe_ duty of GoveTTimeixi^to render

prompt T ĵatrfce against itself in favor~tof--cafi>aens

as^j^is to administer the same between

ictLviduals. The investigation and ad-indication.

"of claims in their nature ^

department.

a thtii j i a d i

lesinger and Israel, The State^tff the Union Messages

President, v. 2, 1060 (1966)/. The legislatio^^fdng

immunity was abolished largely Jto__en£-^h^pi^ctice of

redre^SPg—€P"i 'bills . which left many

citizens without a remedy, fostered lobbyists pressing

dubious claims, and corrupted the Congress.

38th Cong., 1st Sess. 1674-75.

See Cong. Globe,

J See also Rayonier v. United States, 352 U.S. 315, 320

(1957).

On the contrary, precisely because that immunity "gives the

government a privileged position, it has been appropriately

confined," Keifer & Keifer v. Reconstruction Finance Corp.,

306 U.S. 381, 388 (1938), and any authority to sue "is to be

liberally construed." United States v. Shaw, 309 U.S. 495,

502 (1939). When Congress establishes by statute a legal

right, including a right against the federal government, it

must be deemed enforceable by the courts unless there is an

unequivocal congressional intent to the contrary. Insofar

as the 1866 Civil Rights Act is concerned, it is clear that

Congress adopted it primarily for the purpose of creating

judicially enforceable rights.

Indiana al

to the prgtfe

States, t|

by implic

U.S. at 388,

len Cpngress^estab]

fdinq^efright ,-aTgainj

4- ^ U

les by^staptffe a/Tegalf rigfrt,

inc^rfdina^aC right hgaingff the^fdaera^lr^ove^phmervt4 it Xs gen-

tlli{̂ f5resumeQh to ha^e intefided that the riĝ ft woiyld be

enf-orceablo. In Minnesota v. United States, 305 U.S. 382

(1939), Minnesota had sued the United States to condemn cer

tain Indian land. The only applicable federal statute

authorized state suits to condemn Indian land, but did not

say against whom such suits could be brought. The United

States argued that it could not be sued since it had not

waived sovereign immunity. Noting that a suit against the

puld not have been adequate to confer title

.nee it was held in trust by the United

Irt held "that authorization to condemn confers

fn permission to sue the United States." 305

n. 5. See also United States v. Hellard, 322

U.S. 363 (1944). Similarly, in United States v, Jones, 109

U.S. 513 (1883), the Court was called upon to construe a

statute which directed the Secretary of War and his agents,

prior to taking any lancL^^jo first pay such compensation as

may have been ascertainadHn the mode provided by the laws of

the state." 109 U.S. ar5l5. The United States urged that,

although Congress had directed such payment, it was immune from

any suit to force payment. The Supreme Court held otherwise,

and ruled that the statute constituted a valid waiver of sover

eign immunity authorizing suits against the United States in

state court. 109 U.S. at 519-521. The grant of jurisdiction

in Section 3 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act^ is more express than

in Minnesota v. United States and United States v. Jones, and

such a waiver of immunity is equally essential to render mean

ingful the creation of the substantive rightJT involved.

18

2 . The Mandamus Act

Section 1361, 28 U.S.C., provides:

The district courts shall have original

jurisdiction of any action in the nature

of mandamus to compel an officer or employee

of the United States or any agency thereof

to perform a duty owed to the plaintiff.

This provision, enacted in 1962, was intended to confer upon

the district courts the mandamus power until then limited

to the District Court for the District of Columbia. Jarrett

v. Resor, 426 F.2d 213 (9th Cir. 1970); Rural Electrification

Administration v. Northern States Power Co., 373 F.2d 686

(8th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 945. A writ of mandamus

is available to compel a federal officer to perfoi inister-

ial act, Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803),

regardless of whether the official's obligation arises under

the Constitution, a federal statute, a regulation or an Execu

tive Order. Leonhard v. Mitchell, 473 F.2d 709, 713 (2d Cir.

1973) .

The defendant officialsclearly have such a ministerial

duty to make promotions within the General Services Administra

tion without discrimination on the basis of race. -E4.̂ st. jche

Fifth Amendment guarantee of due process of law,, absolutely

prohibits the federal government from discriminating against

blacks in employment, education, or any other regard. Bolling

__/ [T]he Constitution of the United States, in its present

form, forbids, so far as civil and political rights are con

cerned, discrimination by the General Government, or by the

States, against any citizen because of his race.” 347 U.S. at

499, quoting Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 595, 591 (1866).

The Senate Report on the 1972 amendments to Title VII concluded

v. Sharpe. 347 U.S. 497 (1954). "Second

L9

the defendants in personnel matters is strictly circumscribed

by section 7151 of Title 5 of the United States Code, which

d^cjLres it to be the official policy of the United States

"to insure equal employment opportunities for employees without

discrimination because of race, color,religion, sex or national

origin," and directs that the President "shall" carry out this

— 7 Qpolicy. Thucd,—.ir-acial discrimination by defendants is for-

*5̂0 fC'i.

bidden by the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981,

pp. . 9?eunth, discrimination is barred by federal regu-

/

lations and Executive Order.

Continued

on the basis of Bolling that "[t]he prohibition against dis

crimination by the Federal government, based upon the Due

Process clause of the Fifth Amendment, was judicially recog-

ed long before the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of

" S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. (1971),

ôiLivn. Illstioiyy/ ppi 133. The Fifth Amendment has

expressly held to bar federal discrimination in employment

Davis v. Washington, 4 EPD ̂7926 (D. D.C. 1972); Faruk v.

Rogers, 5 EPD 8015 (D. D.C. 1972).

__/ Section 7151 is no mere assertion of social goal^p it

is a direct and unequivocal command to the executive branch

not to discriminate against plaintiff because of his race.

See Henderson v. Defense Contract Administration, ___ EPD ___

(S.D. N.Y. 1973).

__/ Section 713, 5 Code of Federal Regulations xhaiftr oo air

fares a series of Executive Orders dating back to 1948. See

E.O. 9980, July 26, 1948; E.O. 10590, January 18, 1955; E.0.

10925, March 6, 1961; E.O. 11246, September 21, 1965; E.O.

11478, August 8, 1969; E.O. 11590. Both section 713 and

Executive Order 11478 establish that it is the policy of the

government of the Uniied States "to provide equal opportunity

in federal employment for all persons, to prohibit discrimina

tion in employment because of race," E.O. 11478, § 1; 5 C.F.R.

§ 713.202, and require that each executive department and

agency "shall" establish a program to assure "equal opportunity

in employment and personnel operations without regard to race."

E.O. 11478, § 2; C.F.R. § 713.201(a).

k

part,

E.O. 11478, as amended by E.O. 11590, provides in pertinent

"Section 1. It is the policy of the government

2 0

The lower courts have repeatedly held that mandamus is

available to compel federal defendants to hire and promote

without regard to race. In Beale v. Blount, 461 F.2d 1133

(5th Cir. 1972), the plaintiff claimed he had been dismissed

because he was black. The Fifth Circuit concluded: * 5

_/ Continued

of the United States to provide equal opportunity

in federal employment for all persons, to prohibit

discrimination in employment because of race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin, and to

promote the full realization of equal employment

opportunity through a continuing affirmative

program in each executive department and agency ...

"Section 2. The head of each executive department

and agency shall establish and maintain an affirma

tive program of equal employment opportunity for

all civilian employees and applicants for employ

ment within his jurisdiction in accordance with

the policy set forth in Section 1. It is the

responsibility of each department and agency head,

to the maximum extent possible, to provide suffi

cient resources to administer such a program in a

positive and effective manner ..."

5 C.F.R. § 713.201 provides,

"Purpose and applicability. - (a) Purpose. This

subpart sets forth the regulations under which an

agency shall establish a continuing affirmative

program for equal opportunity in employment and

personnel operations without regard to race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin and under which

the Commission will review an agency's program and

entertain an appeal from a person dissatisfied with an

agency's decision or other final action on his com

plaint of discrimination on grounds of race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin."

5 C.F.R. § 713.202 provides,

"General Policy. - It is the policy of the Govern

ment of the United States and of the government of

the District of Columbia to provide equal opportunity

in employment for all persons, to prohibit discrim

ination in employment because of race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin, and to promote the full

realization of equal employment opportunity through

a continuing affirmative program in each agency."

- 2 1 -

Traditionally, the procedural avenue to

reinstatement for an ex-employee of the

federal government claiming to be the victim

of improper discharge has been a petition

for mandatory injunction or writ of mandamus

directed to the head of the agency concerned

commanding the re-employment of petitioner.

... In 1962, Congress broadened the avail

ability of the mandamus remedy by investing

the district courts generally with jurisdic

tion to issue the writ which eliminated the

previous requirement that reinstatement

suits be maintained only in the United States

District Court for the District of Columbia

... Title 28 U.S.C., Section 1361. 461 F.2d

at 1137.

See also, Penn v. Schlesinger, ___ F.2d ___, ___ (5th Cir. 1973),

reversed on other grounds, ____ F.2d ____ (5th Cir. 1974);

Thorn v. Richardson, 4 EPD f 7630, p. 5490 (W.D. Wash. 1971).

Mandamus is also available to enforce a ministerial duty

_ /

to pay a particular sum of money to the plaintiff, though

not to compel payment in an ordinary disputed tort or contract

action. In the instant action plaintiff seeks, inter alia,

an award of back pay. Were this a mere claim for consequential

damages mandamus would be inappropriate. But the applicable

__/ In United States ex rel. Parish v. Macveagh, 214 U.S. 124

(1909), the Secretary of the Treasury had refused to pay the

plaintiff $181,358.95, which payment was required by a special

Act of Congress. This Court held that mandamus was available

to compel the Secretary to issue a draft in that amount. 214

U.S. at 138. In Miguel v, McCarl, 291 U.S. 442 (1934), this

Court held that mandamus was available to compel the payment

of a pension unlawfully withheld by the Comptroller General

and the Army Chief of Finance. In Roberts v. United States ex

rel. Valentine, 176 U.S. 221 (1900), this Court upheld a writ

of mandamus directing the Treasurer of the United States to pay

interest on certain bonds issued by the District of Columbia.

See also Garfield v. United States ex rel. Goldsby, 211 U.S. 249

(1908); Work v. United States ex rel. Lynn, 266 U.S. 161

(1924); City of New York v. Ruckelshaus, 358 F. Supp. 669

(D. D.C. 1973).

22

regulations place upon defendants an unusual express obligation

to compute and award back pay in cases of racial discrimination,

rendering the award of such back pay a ministerial act.

Whether in fact plaintiff was denied promotion because of his

race is a disputed fact to be resolved by the district court.

If the district court determines that discrimination was

involved, the defendants will have an absolute obligation to

provide back pay, and, if they should fail to do so, that court

can compel performance of that ministerial act by a writ of

_ /

mandamus.

Section 713.271(b), 5 C.F.R., provides:

Remedial action involving an employee when

an agency or the Commission, finds that an

employee of the agency was discrimira ted against'

and as a result of that discrimination was denied

an employment benefit, or an administrative deci

sion adverse to him was made, the agency shall

take remedial actions which shall include one or

more of the following, but need not be limited to

these actions:

Retroactive promotion, with back pay computed

in the same manner prescribed by § 550804 of this

chapter, when the record clearly shows that but for

the discrimination the employee would have been pro

moted or would have been employed at a higher grade,

except that the backpay liability may not accrue

from a date earlier than 2 years prior to the date

the discrimination complaint was filed, but in any

event, not to exceed the date he would have been

promoted. If a finding of discrimination was not

based on a complaint, the backpay liability may not

accrue from a date earlier than 2 years prior to

the date the finding of discrimination was recorded,

but, in any event, not to exceed the date he would

have been promoted. (Emphasis added)

__/ The decisions of the Fifth Circuit in this regard'

divided. The panel in Beale held that backpay was awardable

along with reinstatement in an appropriate case. 461 F.2d

1133, 1138. The^anel in Penn concluded that backpay was

unavailable because it would "impinge upon the Treasury."

____ F.2d ___, ____. Neither decision considered the unusual

provisions of 5 C.F.R. § 713.271(b).

23

Sovereign immunity affords no obstacles to the award of

relief by writ of mandamus. Mandamus is in general available

only when the defendants are acting in clear violation of

federal law; in such a case, however, the unlawful acts are no

longer those of the sovereign, and may be corrected by the

courts. The defense of sovereign immunity in a mandamus action

was raised and rejected long ago in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S.

(1 Cranch), 137, 166, 170-171 (1803). Any action in which a

federal official has refused to perform a ministerial act is,

by definition, one in which the official has lost theirantle

_ /

of the sovereign and is a mere private wrongdoer. In addi

tion to sanctioning mandamus actions against federal officials,

Section 1361 also authorizes mandamus against "any agency" of

the United States, including in this case the defendant General

_ / '

Service Administration. This express language modifies the

usual rule that, because of sovereign immunity and the nature

_/ See Clackamas County, Oregon v. Mackay, 219 F.2d 479,

488-496 (D.C. Cir. 1954), vacated as moot, 349 U.S. 909 (1955);

McQueary v. Laird, 449 F.2d 608, 611 (10th Cir. 1971); Byse and

Fiucca, "Section 1361 of the Mandamus and Venue Act of 1962"

81 Harv. L. Rev. 308, 340-42 (1967).

_/ That section 1361 authorized mandamus against an agency

was well understood. Senator Mansfield, explaining the bill on

behalf of the Judiciary Committee, stated that under it the

court can only compel "the official or agency to act where there

is a duty which the committee construes as an obligation, to

act ... As stated in the House report, the bill does not

define the term 'agency,' but the committee agrees that it

should be taken to mean any department, independent establish

ment, commission, administration, authority, board, or bureau

of the United States, or any corporation in which the United

States has a proprietary interest." 108 Cong. Rec. 18784.

(Emphasis added)

24

of mandamus itself, a government agency cannot be subject to

mandamus. The change, however, is one largely of form permit

ting an agency to be sued in its own name; the relief available

is the same as would be afforded if the individual in charge

of the agency were sued instead. Certainly section 1361 con

stitutes a waiver of immunity in any action "in the nature of

mandamus"; if it did not that provision would be in a dead

letter.

25

3. The Tucker Act

Section 1346, Title 28 United States Code, provides in

pertinent part:

(a) The district courts shall have original juris

diction, concurrent with the Court of Claims, of:* * *

(2) Any other civil action or claim against

the United States, not exceeding $10,000 __/ in

amount, founded either upon the Constitution or

any Act of Congress, or any regulation of an

executive department, or upon any express or

implied contract with the United States, or for

liquidated or unliquidated damages in cases not

sounding in tort.

This statute, known as the Tucker Act, is understood to be an

express waiver of severeign immunity as to claims falling within

_ /its scope.

Petitioner's claims clearly fall within the literal language

of Section 1346. Racial discrimination in federal employment

is prohibited by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. See

Bolling v, Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954). An action is "founded

upon" the Constitution whenever the damages are alleged to result

from a violation of the Constitution; the plaintiff need not

prove the Constitution expressly authorizes a lawsuit for that

particular type of violation, since the (constitution) contains

no express authorization of litigation for violation of any of

__/ The Original Complaint contained no allegation as to the size

of plaintiff's claim. The proposed Amended Complaint alleges thatthe amount "in controversy" exceeds $10,000., p. __a, but the

United States denied that such an amount was at stake. Defendants'

Memorandum In Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion to Amend, p. 4. If

this court were to determine that jurisdiction to award backpay and

damages existed only under section 1346, plaintiffs would be entitled

to waive recovery in excess of $10,000 and thus confer jurisdiction

V i, on the .District jCourt, and would do so. See Perry v. United States,

308 F. Supp 245 (D. Colo. 1970), aff'd 442 F.2d (10th Cir. 1971);

Sutcliffe Storage & Warehouse Co. v. United States, 162 F.2d 849 (1st cir. 1947); United States v. Johnson, 153 F.2d 846 (9th Cir.

1946); Hill v. United States, 40 F.2d 441 (1st Cir. 1889); Jones v. United States, 127 F. Supp. 31 (E.D.N.C. 1954).

__/ United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 340 U.S. 543 (1951); Spillway

Marina, Inc, v. U.S.. 445 F.2d 876 (10th Cir. 1971); Lloyds' London

v. Blair, 262 F.2d 211 (10th Cir. 1958); Union Trust Co. v. United

States, 113 F. Supp 80 (D.D.C. 1953), aff'd in part 221 F.2d 62, cert, denied 350 U.S. 911.

26

its provisions. Similarly, the discrimination of which

plaintiff complains is a violation of two federal statutes,

5 U.S.C. § 7151 and 42 U.S.C. § 1981. An action is "founded

upon" a federal statute if the government action complained

of is a violation of that statute, regardless of whether the

statute itself creates or contemplates a cause of action.

The lower courts have unanimously rejected the argument that

an action under the Tucker Act can only be "founded upon" a

a

actions

__/ m Smith v. United States, 458 F.2d 1231 (9th Cir. 1972)the plaintiffs sued under § 1346(a)(2), alleging a violation

of the Fifth Amendment's prohibition against taking private

property without just compensation; the Ninth circuit unanimously

upheld a judgment in favor of plaintiffs. An3 ~%n United States

Iv .Hil?.sle.f> 237 U.S. 1 (1915), an action was upheld under this section as "founded upon" Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, which forbids taxes on exports from any state. Similarly, in

Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents. 403 U.S. 388

I (1971) , thfr Supreme-Court upheld .th^t>a suit against federal

employees arising out of a violation of the Fourth Amendment was

an action which prises under the Constitution." See, 28.U.S.C.

§ 1331(a). None of the constitutional provisions in Smith,

Hvoslef or Bivens contained any authorization of a civil action.

/ Section 1346(a)(2) has long been construed to authorize

ho—cCmpeT) refund of fines or penalties, on the ground propriety of the fine or penalty was governed by a federal statute. See Carriso v. United States. 106 F.2d 707

(9th Cir. 1939); Compagnie General Translantigue v. United

States, 21 F.2d 465 (S.D. N.Y. 1927), aff'd 26 F.2d 195.

Spanish Royal Mail Line Agency, Inc, v. United States, 45 F.2d

404 (S.D. N.Y. 1930); Sinclair Nav. Co. v. United States. 32

?:2d ?? (5th Cir. 1929); Sultzbach Clothing Co. v. United States,10 F.2d 363 (W.D. N.Y. 1925); Law v. United States, 18 F. Supp

42 ( D. Mass. 1937); Lanashire Shipping Co. v. United States,

4 F. Supp 544 (S.D. N.Y. 1933). Litigation unde~§"l346TTai

been expressly sanctioned as "founded upon" a wide variety of

other statutes which set the standard for government conduct,

but contained no mention of any remedy. See, e.g., Beers v.

Federal Security Administrator. 172 F.2d 34 (2nd Cir. 1949)

(Social Security Act); Ross Packing Co. v. United States, 42

F. Supp 932 (E.D. Wash. 1942) (National Labor Relations Act);

Alcoa S.S.Co. v. United States, 80 F. Supp 158 (S.D. N.Y. 1948) (Transportation Act).

27

federal statute which itself creates a remedy or right of

_ /action. In United States v. Emery, Bird, Thayer R.R. Co.,

237 U.S. 28 (1915), this Court held that an action to recover

a tax was "founded upon" the Corporation Tax Law under which

the tax was collected, although that tax provision contained

_ /no remedial provision. 237 U.S. at 31-32.

__/ In Aycock-Lindsey Corporation v. United States, 171 F.2d

518 (5th Cir. 1948), the United States urged that an action under

§ 1346 could not be "founded upon" the Soil Conservation and

Domestic Allotment Act because that statute "created no enforceable

claim or right of action against the Government." 171 F.2d at 520.

The Fifth circuit expressly rejected that argument:

The Tucker Act does not provide that a statute

of Congress upon which a statute is founded

shall also provide that suit may be maintained

against the United States for claims arising

under such statute. The authority for a suit

is found in the general terms of the Tucker Act

and need not be reiterated in every enactment of

Congress upon which a claim against the United

States could be "founded." 171 F.2d at 518.

Similarly, in Compagnie General Transatlantigue v. United States,

21 F.2d 465 (S.D. N.Y. 1927) the court held that an action for

the refund of a penalty could be founded upon the provisions of

the Immigration Laws under which the penalty had purportedly been

collected. 39 Stat. 880 and 43 Stat. 155. Judge Augustus Hand explained:

To limit recovery in cases "founded" upon a

law of Congress to cases where the law provides

in terms for a recovery would make that pro

vision of the Tucker Act almost entirely

unavailable, because it would allow recovery

only in cases where laws other than the Tucker

Act already created a right of recovery. "Founded"

must therefore mean reasonably involving the

application of a law of Congress. 21 F.2d at 466.

See, also Ross Packing Co. v. United States, 42 F. Supp 932. 937 (E.D. Wash".""1942) .

__/ ~$his Arises under tbiejfederal regulation

forbidding discrimination rnTiederai employment. 5 C.F.R. § 713,

and Executive Order 11478. In Gnotta v. United States. 415 F.2d

1271 (8th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397 U.S. 984 the court con

cluded that no action under the Tucker Act could be had to enforce

the order and regulation on the ground that neither mentioned money

claims, and "none of the executive orders or regulations . . .

purports to confer any right on an employee of the United States to

institute a civil action for damages against the United States."

415 F.2d at 1278. This reasoning is plainly erroneous. First,

since the decis>gtS--4̂ »-̂ jris>j:ta the regulations have been amended to

authorize theymvard of pack pay. Second, no mere regulation of

Executive Ord^r couiW, bv^xtself, create a federal cause of action;

only Congress na^^ffiaj^5ower. Third, the reasoning in Gnotta —

that an action can only be "founded upon" a regulation which itself

creates a cause of action — is precisely the construction of the Tucker Act consistently rejected by all other federal courts.

2 8

J

-bg ,

The lisfe&ea-l tarrgrt&efe- of § 1346 is manifestly

broad enough to cover claims for damages and back pay arising

out of racial discrimination in employment. The statute

covers "any claim" arising under the Constitution, statutes

or regulations, and, while there are express exceptions,

they are not applicable to this case. As this Court held

in construing a similar provision, "The statute's terms

are clear . . . they provide for district court jurisdic

tion over any claim . . . . Without resort to an automatic

maxim of construction, such exceptions make it clear to

us that Congress knew what it was about when it used the

term 'any claim'". Brooks v. United States, 337 U.S. 49,

51 (1949).

This construction of § 1346 is supported by the

interpretation given by the Court of Claims to the similarly

tAhU(WV / . .vav-eride'd-7provisxons of 28 U.S.C. § 1491. The latter statute

provides, inter alia,

The Court of Claims shall have jurisdiction

to render judgment upon any claim against the

United States founded either by the Constitu

tion, or any Act of Congress, or any regulation of an executive department . . .

In Cnambprs v. United St-aXLes . 451 F. 2d 1045 (Ct. Cl. 1971),

the court held that a claim of racial discrimination in

federal employment stated a cause of action under § 1491,

since such discrimination violated Executive Orders 11246

and 11478. The Court of Claims expressly considered, and

held erroneous, the reasoning in Gnotta v. United States,

415 F .2d 1271, (8th Cir. 1969), cert. denied, 387 U.S. 934.

See also Allison v. United States, 451 F.2d 1035 (Ct. Cl.

1971); Pettit v. United States, No. 253-72 (Ct. Cl. 1973)

__/ Section (d) provides:

have jurisdiction under this

or claim for a pension. "

"The district courts shall not

section of any civil action

2 9

- \,V* - yg,

> A ' A 'b it yt'"•>*, ■Jf: *" j/—- /-• v, «A». " J* •

: * •■»••**■ s./**V*i ffl*V

J

(Opinion dated December 19, 1973), The decisions of the

Court of Claims construing its own jurisdiction, which is

by definition concurrent with and identical to that of

the district courts, must be afforded substantial weight.

See Beale v. Blount, 461 F.2d 1133, 1135 n.2 (5th Cir.

1972). District court jurisdiction under the Tucker Act

to award back pay for discrimination in employment was

expressly upheld in Palmer v. Rogers, 5 EPD 51 8822, p. 5493

n. 1 (D.D.C. 1973) .

That back pay is available under the Tucker Act

is made abundantly clear by its legislative history. Prior

to 1964, § 1346 expressly excluded from its coverage " [a]ny

civil action or claim to recover fees, salary or compensa

tion for official services of officers or employees of

the United States." See, 28 U.S.C.A. § 1346(d)(2) (1952).

This exception to the broad language of § 1346(a)(2) was

understood to preclude the award of back pay. Jackson v.

United States, 129 F.Supp. 537 (D. Utah 1955). In 1954

this restrictive provision of Section 1346 was repealed.

Pub. L. 88-519, 78 Stat. 699. The House Report, the

__/ H. Rep. 1604, 88th Cong., 2d Sass., p. 2P "The com

mittee notes that by virtue of the act of October 5, 1952

(76 Stat. 744, 28 U.S. § 1361), it is now possible for

Government Employees who claim to have been improperly

discharged to sue in their home districts for reinstate

ment. However, the present prohibition of subsection

(d)(2) of section 1346, 28 United States Code makes it

necessary for any claim for back pay to be brought in

the Court of Claims. The committee believes that when

the amount claimed as back-, pay is not more than $10,000,

and is therefore within the monetary limit of the district

courts 1 general jurisdiction of contract claims against

the United States the issue of reinstatement and the issue

of compensation should be susceptible of being disposed

of in a single rn I imi " 'Y , 1 n» ̂ ng

3 0

/Senate Report, and the congressional debates all

(/( t \ e\ • A,

agreed that the^f irst^purpose of the change was to allow

actions for back pay in the district courts.

Section 1346 therefore confers jurisdiction

on the district court to award plaintiff back pay and

damages up to $10,000 upon a showing that he was denied

a promotion or otherwise discriminated against because

of his race.

S.Rep.

and Admin.

1390, 88th

News (1964),

Cong., 1st

p. 3255,

Sess., 2 U.S. Code Cong.

"Under the existing statutes, any officer or

employee of the United States is required to

file only in the Court of Claims here in

Washington a civil suit to recover fees, salary,

or compensation for services rendered as an

officer or employee of the United States. By

virtue of the act of October 5, 1962 (76 Stat.

744, 28 U.S.C. 1361), it is now possible for

Government employees who allege they have been

improperly discharged to sue in their home dis

tricts for reinstatement, but under the prohibi

tion of subsection (d) of 28 U.S.C., Section

1346, the employee's claim for back pay, which very frequently accompanies his claim for rein

statement, must be brought in the Court of Claims.

Under the circumstances it is clear, that in order to do complete justice as efficiently

and inexpensively as possible, the district

courts should be given jurisdiction of the

compensation claimed as well as the improper

discharge, in order that they may be disposed

of in a single action."

/ 110 Cong. Rec. 19766 (Remarks of Sen. Keating):

"This bill will have its most salutary effect in

employee discharge cases. Today, under a 1962

statute, a Government employee who claims to have

been improperly removed from his position may sue

to get his job back in his local federal court.

But the subsection of the Judicial Code whichthe

present bill would repeal today prevents the

employee , if he succeeds in establishing his

right to reinstatement from getting a judgment

in the same action for the backpay to which he

is also entitled. To get the back pay, he must

either bring another suit in the Court of Claims

or, in some instances,seek the additional relied

administratively. Now, if this bill is finally

approved, it will be possible for him to secure

both reinstatement and complete monetary relief

in single proceeding."

__/ Injunctive relief is not available under the Tucker Act.

See Clay v. United States, 210 F.2d 686 (D.C.Cir. 1954);

Rambo v. United States, 145 F.2d 670 (5th Cir. 1944), cert.

denied 324 U.S. 848; Blanc v. United States, 244 F.2d 708

(2d Cir. 1957).

- 31 -

4. The Administrative Procedure Act

Section 10(a) of the Administrative Procedure

Act, 5 U.S.C. § 702, provides in broad language that

"[A] person suffering legal wrong because of agency action,

or adversely affected or aggrieved by agency action within

the meaning of a relevant statute, is entitled to judicial

review thereof." The remedy which a reviewing court can

afford is broadly cast; the aggrieved plaintiff may main

tain "any applicable form of legal action, including actions

for declaratory judgments or writs of prohibitory or mandatory

injunction . . ."5 U.S.C. § 703. The reviewing court is

commanded to

(1) compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed; and

(2) hold unlawful and set aside agency action,

findings, and conclusions found to be -

(a) arbitrary, capricious, an abuse

of discretion, or otherwise not

in accordance with .alw;

(b) contrary to constitutional right,

power, privilege, or immunity . . .

5 U.S.C. § 706.

The instant action is within the literal language

of the Administrative Procedure Act. p/a intiff is undeniably

aggrieved by the refusal of the defendant General Services

Administration to promote him. A refusal to promote plaintiff

because of his race would be in violation of his rights under

the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. See § 706(2) (b) .

Any decision based on racial discrimination is by definition

"arbitrary and capricious." § 706 (2) (b) . And snoh,discrimina

tion violates two federal statutes, 42 U.S.C. § 1931 and 5 U.S.C.

§ 7151, a series of Executive Orders culminating in Executive

Order 11482, and the applicable federal regulations, 5 C.F.R.

§ 713, and is undeniably "not in accordance with law." §706(1)

_ /and (2)(a). The coverage of the Administrative Procedure Act

__/ "Law

Preserve

clearly includes regulations,

Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S.

See e.g. Citizens to

402

e r s v

_ /is to be liberally interpreted. There is nothing to

indicate any intent to preclude judicial review in the

language, or legislative history, of the Fifth Amendment,

42 U.S.C. § 1981, 5 U.S.C. § 7151, Executive Order 11482,

or 5 C.F.R. § 713. While there are certain express exceptions

to the provisions for judicial review, see 5 U.S.C. 701(b),

none of them are applicable here.

It is well established that the Administrative

Procedure Act confers jurisdiction on the district courts

to review agency action. The question was resolved by this

Court in Rusk v. Cort, 396 U.S. 367 (1962), where the plain

tiff sued under the Administrative Procedure Act and the

Declaratory Judgment Act to overturn a decision of the

Secretary of State. The Court, reasoning that "on their

face the provisions of these statutes appear clearly to

permit an action such as was brought here to review the

final administrative determination of the Secretary of State,

'concluded that "the District Court was correct in holding

that it had jurisdiction to entertain this action for

H

__/ As this Court detailed in Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner,387 U.S. 136, 140-141 (1967):

The legislative material elucidating

that seminal act manifests a congressional

intention that it cover a broad spectrum of

administrative actions, and this Court has

echoed that theme by noting that the Ad

ministrative Procedure Act's ♦generous

review provisions" must be given a ♦hos

pitable? interpretation. Shaughnessy v.

Pedreiro, 349 U.S. 48, 51, 9^ h.ad 000; 073 j 951

■C i 0 In. tiCHr; see United States v. Interstate

Commerce Comm'n, 337 U.S. 426, 433-435,

Ljud. 1451, T4CCJ, 0 9 'Mi©’! Brownell

v. Tom We Shung, supra; Heikkila v. Barber, supra. Again in Rusk v. Cort, supra 369 U.S. at n7Q-nno -n T i m ■ i on., .

the Court held that only upon a showing of

♦iclear"* and convincing evidence" of a con

trary legislative intent should the courts restrict access to judicial review. See

also Jaffe, Judicial Control of Administra

tive Action 336-359 (1965). See also

Chicago v. United States, 396 U.S. 162 165 (1969; Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Re

development Agency, 395 F.2d 920, 932-933

(2d Cir. 1968) . /<

- 3 3 -

0

_ /declaratory and injunctive relief." 369 U.S. at 370, 372.

That the Administrative Procedure Act confers jurisdiction

on the district court has been repeatedly affirmed by the

lower courts. The "legal right" which plaintiff seeks to

enforce need not be contained in a statute which establishes

an independent basis of jurisdiction; it is sufficient that

the statute was enacted to protect plaintiff's interests.

Norwalk Core v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F.2d 920,

933 (2d Cir. 1968)

The Administrative Procedure Act, by virtue of

conferring jurisdiction to review the actions of federal

agencies, ipso facto waived any immunity those agencies might

have frornhsuit. Manifestly if the Act contained no such waiver,

it would be a dead letter. Four circuits have expressly held

that the Administrative Procedure Act constitutes a waiver of

The same conclusion has been reached

_ /courts. The District of Columbia Circuit

sovereign immunity,

by several district

&__/ Justice Brennan, concurring, -haid. that the Administrative

Procedure Act was a general grant of jurisdiction. 369 at

380, n. 1. Justice Harlan dissented on the ground that juris

diction had been withdrawn by the Immigrational Nationality

Act of 1952, but agreed that otherwise it would have been

conferred by the Administrative Procedure Act. See 369 U.S. at 383-399.

__/ See Citizens Committee for Hudson Valley v. Volpe,

425 F.2d 97, 102-103 (2d Cir. 1970) cert, denied 400 U.S.

949 (1970); Cappadora v. Celebrezze, 356 F.2d 1, 5-6 (2d Cir.

1966); Schicker v. United States, 346 F.Supp. 417, 419 (D.

Conn. 1972) modified on other grounds sub no Schicker v.

Romney, 474 F.2d 309 (2d Cir. 1973); Road Review League v.

Boyd, 270 F.Supp. 650, 651 (S.D.N.Y. 1967); Harris v. Kaine,

352 F.Supp. 769, 772 (S.D.N.Y. 1972). See also Davis v.

Romney, 355 F.Supp. 29, 40-42 (E.D. Pa. 1973); Northeast

Residents Association v. Department of Housing and Urban